2016-17

JOHN NEAR GRANT Recipient

Art in the Era of AIDS: A Look at the Emergence of “AIDs art” in 1980s and 90s New York City as a Result of AIDs Activism

Sarisha Kurup, Class of 2017

Art in the Era of AIDS:

A Look at the Emergence of “AIDs art” in 1980s and 90s New York City as a Result of AIDs Activism

Sarisha Kurup

2017 John Near Scholar

Mentors: Ms. Donna Gilbert, Ms. Sue Smith April 12, 2017

The first cases of AIDs emerged in 1981, and in the city of New York there began quick whisperings of a “gay plague.” 1 Still, the music was loud, the dresses neon, and the President blind. As the cases spread, pulsing beneath the roar of the 80s like an inevitable beast, as the politicians dismissed the disease as one that simply affected prostitutes, drug users, and gays, artists rose up in protest.2 In art, a marginalized group found its voice, and demanded to be acknowledged, demanded to be saved.

The Reagan Administration was perhaps one of the worst enablers of the AIDs epidemic.3 Though the gay community had made significant advances since World War II, the AIDs epidemic proved to be what often seemed like an insurmountable roadblock and the lack of support from the administration was, for many, fatal.4 Without the necessary funding for proper care many people in the community realized that they needed to be heard. The gay community was already a creative one, but when the epidemic hit in 1981, the artists had a newfound urgency. Suddenly, they were aware of their works’ ability to outlast them. Many intended to use art to magnify their voices. Dan Cameron, interim director at the Orange County Museum of Art in Newport Beach, California, and curator of Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz at the New Museum in 1999 explains that “art was fundamentally altered by the experience of AIDS; the scope of the mortality really did trigger a sense of emergency in the art world.”5

Thus came the emergence of “AIDs art,” art that was focused on magnifying the voices

1 Douglas Crimp, introduction to AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1987), digital file.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid

4 Ibid.

5 Barbara Pollack, "DOCUMENT, PROTEST, MEMORIAL: AIDS IN THE ART WORLD," ARTNEWS, May 5, 2014.

of AIDs patients and capturing the nuances of their experience. AIDs art was built on the idea that its artists had a powerful and specific message to spread, and had an extra burden to connect with the masses in order to pass on that life-saving message: fight for these people, save these people. These specific challenges fostered a unique aesthetic in AIDs art, one that was more accessible, more bold and forceful in its statements. Furthermore, it facilitated a new way of receiving and experiencing the work as well, as audiences felt that call to action.6 They were not simply passive viewers. Instead, they, like the artist, held unique power to affect the meanings of the artworks by changing the course of AIDs history.

The artwork created during the AIDs epidemic often addressed three main subject areas: politics, public health education, and personal tragedy. Rarely did a piece only cover one of the three. To cover the political artists often touched upon the personal impetus. To further public health education, the artist had to create a personal urgency. And when exploring the personal experience of AIDs, it was almost impossible not to include a hope for change, both politically and in public health.

Often times, the art took the voice of a nascent resistance, and thus was angrier and more volatile. The artists were also dying of the disease, and the emotional vibrancy of their work came from that realization. Although their art, so intent on sending a message, was certainly propagandistic, it was that personal element that made it stand apart and perhaps what made the work so effective.7 In order to convey those specific messages artists often tailored their works to serve as a communication vehicle, and thus developed distinct stylistic choices that matched the

6 Toby Clark, Art and Propaganda in the Twentieth Century: The Political Image in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997).

7 Clark, Art and Propaganda

urgency of their goals. These choices are what distinguish AIDs art from other modern artworks.8

However, the AIDs art did fit into the history of “visual activism,” a genre of art that became especially prominent in the 20th century, when global conflicts bred widespread awareness of issues, and visual art was used to extol ideologies of competing factions, by governments and their opponents alike, paving the way for the artists of the AIDs movement to use images to shape public perspectives.9 For example, Nazi posters gleamed red, displaying a kind-looking Hitler holding children and emblazoned with text like “Children, What Do You Know of the Führer?”10

Children, What Do You Know of the Führer, photograph, accessed April 11, 2017

The use of saturated coloring, of distinct and intentional images, of bold lettering, fits into the legacy of visual propanda and media advertising. Opposition movements fed visual activism as well, from the anti-war Dadaists to feminist artists like Judy Chicago, Guerilla Girls,

8 Steven Heller, Graphic Intervention: 25 Years of International AIDS Awareness Posters: 1985-2010 (Boston, MA: The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 2011).

9 Ibid , 22.

10 Ibid , 23.

and Pussy Riot.11 While some AIDs art embraced the performance art aspect of Guerilla Girls (most notably Gran Fury), and the tools of propaganda poster art, others looked to the more introspective tactics of Vietnam war artists and Dadaists, who both embraced popular culture and subverted it.

AIDs artists, influenced by this history of visual activism as well as the growing advertising sector, began to use media techniques to spread their messages further than their voices could travel. The 1980’s brought the rise of media, graphic design, and stylized art, and artists took full advantage.12 Lorine McAlpine, artist in the art collective Gran Fury, explained that:

We simply used the tools that were available to us, and of course the languages of advertising and appropriation were two of the first places we looked, even as we sought to insert unexpected messages in those vocabularies…The press, government, and the medical establishment were not delivering information or countering stigma; we wanted our activist voice to fill that void.13

Gran Fury, which was McAlpine’s group, and General Idea, a Toronto to New York City transplant art collective, made great strides in blending media advertising and art. Their works are unique in that most of the pieces credited to them were created by multiple people and thus have been scrutinized from many points of view during the creative process.14 Thus they often

11 Ibid , 91.

12 T.V. Reed, "SEVEN: ACTing UP against AIDS: The (Very) Graphic Arts in a Moment of Crisis," in Art of Protest : Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle (Minneapolis, MI: Univ Of Minnesota Press, 2005).

13 Heller, "How AIDS.”

14 Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), digital file.

seem to display AIDs arts’ unique ability to double as both advertisement and art alike, and prove fertile ground for further examination for what defines the art of the AIDs era. German curator Frank Wagner, one of the first to put together art exhibitions centering on AIDs, explains that “there was an AIDS aesthetic developed by artists’ groups like General Idea or Gran Fury, whose media strategies criticized the indifference of society.”15

Gran Fury formed when, in November of 1987, Bill Olander of the New Museum offered the museum window on Broadway to ACT UP, the “AIDs Coalition To Unleash Power,” a New York City AIDs activist group.16 From ACT UP members a smaller group formed, determined to use the opportunity to send a message. The group created the installation, "Let the Record Show" and then continued to meet, eventually growing to eleven members (Richard Elovich, Avram Finkelstein, Amy Heard, Tom Kalin, John Lindell, Loring McAlpin, Marlene McCarty, Donald Moffett, Michael Nesline, Mark Simpson and Robert Vazquez) and titling themselves “Gran Fury.”17 The group was always connected to ACT UP, and thus was most often hyperpoliticized. McAlpine noted that “for many of the early organizers of ACT UP, not having full attention of the health and political establishment was something new - an awareness that the gains of gay liberation were limited.”18 This fact proved a driving force for the artists of Gran Fury, realizing that they had a specific duty to awaken the establishment, and they often did so in jarring and provocative ways using both visual language and bold text.

General Idea, the other prominent AIDs art collective, found many similarities with their

15 Pollack, "DOCUMENT, PROTEST”.

16 Heller, "How AIDS.”

17 Gran Fury, "Good Luck...Miss You- ~ -Gran Fury," Act Up NY, last modified 1995, accessed November 17, 2016.

18 Ibid.

peers in Gran Fury, but because they were not specifically tied to an activist group, often created art that was more introspective. Certainly the urgency still existed, but it did not manifest itself with the same frenzy that Gran Fury created. General Idea was a collective of three Canadian artists: Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and AA Bronson.19 They were active until 1994, when both Partz and Zontal died of AIDs. Where Gran Fury found their niche in political postering, General Idea invested most of their strengths in installations, creating during their tenure over 75 temporary public art projects.20

To examine the art of Gran Fury and General Idea, one must pay close attention to each artistic choice. In a collective, with multiple minds working on the same piece, no choice is an accident. Specifically, AIDs art contains decisive usage of color, typography, appropriation, graphic design, symbolism, and photography in an effort to convey both political and personal messages. These elements are necessary to passing on the essential message of the art. Though the pieces take elements of the art historical tradition that they come from, most notably pop-art, the disease from which they are birthed set them apart from other visual activism and other art of the 1980s. As Gran Fury stated, the traditional artistic techniques left the artists of the AIDs epidemic “unable to communicate the complexities of AIDS issues.” 21

Women Don’t Get AIDs, They Just Die From It, 1991

Though the AIDs epidemic in large part affected gay men, it was certainly not exclusive and, as with many activist movements, there was a struggle to be inclusive. In fact, it was not until 1993 that the Center for Disease Control acknowledged women as victims of AIDs, a fact

19 Gary Indiana, "From Love to AIDS: The Death & Life of General Idea," The Village Voice (New York, NY), December 5, 1995.

20 Ibid.

21 Heller, "How AIDS.”

that had previously prevented women afflicted by the disease from receiving treatment, health care, and disability benefits. 22 Perhaps even this 1993 concession would not have taken place if not for the women in ACT UP, who staged multiple protests, including sit ins at the Center for Disease Control, to shine a spotlight on the lack of regard for women with AIDs.

Gran Fury, a part of ACT UP, was immediately aware of this oversight and strove to combat the narrowed definition of AIDs, largely through their signature medium: posters. Posters were a perfect vehicle for the art collective because their message was meant not simply for the artistic community, but for politicians and for the general public. Posters allowed for a mass distribution of a message intended for a large and diverse audience.

In order to create a poster that could not only capture an audience in the moment, but linger in their memory long enough to catalyze a response, the artists of Gran Fury utilized techniques not dissimilar to those used by media and advertising. Thus, many of their choices are both artistic and tactical.

To bring attention to the women’s cause within AIDs, the collective created their 1991 poster, Women Don’t Get AIDs, They Just Die From It. Installed in hundreds of bus stops across New York City, the poster’s vivid purple hue and bold text immediately draws in the passersby.23 The choice of the color purple is significant because the color has a history tied to that of homosexuality. Most prominently in 1950s, mass firings of homosexuals from the United States Government, in the style of Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare, were referred to as The Lavender Scare, derived from the term “lavender lads” a coin for gay men.24 Here, Gran Fury

22 Alexis Shotwell, "“Women Don't Get AIDS, They Just Die From It”: Memory, Classification, and the Campaign to Change the Definition of AIDS," Hypatia 29, no. 2 (Spring 2014): accessed December 15, 2016.

23 Rick Poyner, No More Rules: Graphic Design and Postmodernism (London, UK: Laurence King Publishing, 2003), accessed December 15, 2016.

24 David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal

reclaims the color, also significant because it can be derived from the colors red and blue, traditional symbols for woman and man and an indication that the epidemic is not exclusive to either, but a peril for both.25

Gran Fury, Women Don't Get AIDs, They Just Die From It, 1991, poster, Brooklyn Museum, New York City, NY, accessed April 9, 2017

Government (Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 2006), digital file

25 Rick Poyner, No More Rules: Graphic Design and Postmodernism (London, UK: Laurence King Publishing, 2003), accessed December 15, 2016.

The choice of text is less political, more tactical. The artists chose a large, bold, book-like font, one that throws the images behind it into the background and makes the words the most prominent piece of the poster. 26 This is not a message meant to be teased out by academics or art collectors. No, this is a message that is being proclaimed with an inescapable urgency. There is no time for misinterpretations because women are dying as people sit in bus stops confronted by these posters. The artists would rather be straightforward, tell you what they think, what they know to be true. 27 By making the text large, and a stark white, they not only steal your attention, but they accost you with their message.

The image behind the text however, doused in purple, should not be ignored. Feeding into the 1980’s hunger for retro imagery of the 1950’s, Gran Fury placed a line of beauty queens, each with sashes proclaiming where in America they are from, behind their words.28 The image is haunting, memorable because these women are healthy, and yet the words on top of them lend a sense of foreboding for what they have the potential to become. Gran Fury’s decision to use photographs of women, instead of creating the image themselves, is significant because it makes the piece more eerie, to be confronted by the frozen smiles of real people.29 These women are the idyllic vision of femininity that America chooses to see, but they are not the reality, thus they fade away into the purple.

Let the Record Show, 1987

26 Brett C. Stockdill, Activism Against AIDS: At the Intersection of Sexuality, Race, Gender, and Class (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003), accessed December 15, 2016.

27 Rick Poyner, No More Rules: Graphic Design and Postmodernism (London, UK: Laurence King Publishing, 2003), accessed December 15, 2016.

28 Poyner, No More

29 Ibid.

One of the most prominent and long-lasting pieces from Gran Fury was their first exhibit, the Silence=Death window installation, is now regarded as one of the seminal works of the group.

30 It is perhaps the neatest display of intertwined artistic and advertising techniques, where sleek symbolism conveys a clear political message. The installation was created in 1987, when New Museum curator and a member of ACT UP himself, William Hollander, invited the group to create an installation for the museum’s window. The installation was given the name “Let the Record Show…,” one that points to the significant political undertone.

Gran Fury, Let the Record Show . . ., 1987, installation, New Museum, New York City, NY, accessed April 9, 2017.

30 Jesse Green, "When Political Art Mattered," The New York Times (New York, NY), December 7, 2003, http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/07/magazine/when-political-art-mattered.html.

The image itself, however, is not original. A year earlier, the Silence=Death Collective, a group of six men who congregated just before the creation of ACT UP, created the Silence=Death poster, and plastered it all over New York City as Gran Fury later did.31 The group was made up of six gay men, Avram Finklestein, Brian Howard, Oliver Johnston, Charles Kreloff, Chris Lione, and Jorge Soccaras, united by their indignance at the lack of a government response to the epidemic.32 Avram Finkelstein later became a member of Gran Fury.33

Often times, AIDs art had two messages for two audiences: those with the disease, and those without who had the power to change the status quo. It was a message of solidarity coupled with a message of imperative action. Let the Record Show… is no different. Its title was a warning to those, particularly in the government, who chose to ignore AIDs, a warning that they will be on the wrong side of history. This, coupled with the specific photos of people the artists wanted to hold responsible plastered in the background (including conservative writer William F. Buckley who wrote in a New York Times editorial that those with AIDs ought to be “tattooed in the upper forearm, to protect common-needle users, and on the buttocks, to protect the victimization of other homosexuals.”34 ) sends clear and defiant accusations about the scope of the tragedy that was being ignored. The very message “silence=death” holds every passerby who catches sight of the text complicit in their silence

Furthermore, the installation implies a sense of unity and empowerment amongst those with the disease. Instead of trying to garner pity with images of decaying bodies or personalized

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 William F. Buckley, Jr., "Crucial Steps in Combating the Aids Epidemic; Identify All the Carriers," New York Times, last modified March 18, 1986.

photographs of victims, the lack of visual representation implies complicity in these deaths. This was a simple, yet powerful statement. Avram Finkelstein explained that to the artists, “the primary objective of Silence=Death was two-fold: to prompt the LGBTQ community to organize politically around AIDS, and to imply to anyone outside the community that we already were.”35

The construction of image and text, though not strictly created by Gran Fury, are reminiscent of the same melding of art-media strategies that the collective made their signature. The pink triangle is a political statement, as it was the symbol of homosexuality in the Nazi regime, a reminder of other governments that not only ignored, but targeted, populations that they did not want to acknowledge. It is a reminder that if the American government is not careful, it too could walk that same path. Finkelstein recalled that “while we initially rejected the pink triangle because of its links to the Nazi concentration camps, we eventually returned to it for the same reason, inverting the triangle as a gesture of a disavowal of victimhood.”36 Further, Finkelstein has remarked on the inclusive nature of using the symbol, explaining that “We realized any single photographic image would be exclusionary in terms of race, gender and class and opted instead to activate the LGBTQ audience through queer iconography.”37

The choice of a centered, bright pink symbol, surrounded by the blackness of the window is also one that easily catches the eye, and is easy to remember long after you’ve walked by it. In choosing to use a symbol, the artists were able to convey a more tantalizing message than with imagery because symbols allow the viewers to see what they want to see, a popular advertising technique to draw in different kinds of people, and in this case, make them all disavow silence38

35 Avram Finkelstein, "The Silence=Death Poster," LGBT@NYPL, last modified November 22, 2013.

36 Ibid.

37 Finkelstein, "The Silence=Death," LGBT@NYPL.

38 Heller, Graphic Intervention.

In the blackness of the disease, what is lit up is a call to action, a chance at redemption, packed into a visually distributable art piece.

Similarly, the use of text in the piece, like other Gran Fury posters, is tactical and bold, in order to deliver an unmistakable message.39 Avram Finkelstein explained that “the font was graphically on trend. The black background carved its own space in the urban clutter of commercial advertising.” Surmounting the urban clutter to latch onto people was the most important part. For those who were drawn closer, lit up underneath the triangle in smaller text were the words “Turn anger, fear, grief into action," an appeal to the most devoted of viewers to not simply trudge past.

He Kills Me, 1987

Much of the determination and indignance that fueled the artwork of Gran Fury came from the United States government’s utter refusal to acknowledge the widespread epidemic. In fact, President Ronald Reagan did not utter the word “AIDs” until 198740, by which time 60,000 Americans had been diagnosed with the disease, half of whom had died.41 Even when he did acknowledge the disease, Reagan made no effort to sympathize with the victims, claiming that “AIDS information can not be what some call 'value neutral.' After all, when it comes to preventing AIDS, don't medicine and morality teach the same lessons?" 42 Without government priority, AIDs research remained underfunded, and the disease continued to be viewed as “God’s

39 Ibid.

40 Allen White, "Reagan's AIDS Legacy / Silence equals death," SF Gate(San Francisco, CA), June 8, 2004, accessed December 15, 2016.

41 Ibid

42 Ibid.

43

punishment against gays.” In many cases, attempts to educate the public about AIDs were shut down and prohibited, with claims that they “encouraged or promoted homosexual activity.”

The President’s refusal to treat the epidemic as a national emergency fueled the anger of many in the gay community, and artists like Gran Fury took it upon themselves to hold him directly accountable.

In 1987, Donald Moffett of Gran Fury created a print with Ronald Reagan’s face on it, with text in bright orange that read “He Kills Me.” Like many of Gran Fury’s pieces, the message is direct. The print was carried as a poster at Act Up marches, and thus is constructed in a way that is specifically meant to make it stand out, tellingly bold, a perfect example of how artists like Gran Fury had to create not just to express their own anger and pain but also to spread a message that was easy to access. Thus, they made specific artistic choices because of this extra responsibility.44

43 Ibid.

44 Darien Taylor, "In Your Face: AIDS Posters Confront Stigma," The Body: The complete AIDs/HIV Resource, Summer 2014, [Page #], accessed December 15, 2016.

Gran Fury, He Kills Me, 1987, offet lithograph, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, accessed April 9, 2017.

In the case of He Kills Me, Moffett juxtaposes an orange-and-black target with a blackand-white photo of the President. The implications of the black and orange target are unmistakable, calling out the President’s false morality and silence as a direct attack on the gay community. The effect of the target is augmented by the smirk on Reagan’s face, linking the two so that the target seems premeditated or intentional.45 The photograph of Reagan is specifically chosen because he does not look sympathetic, nothing like the suave actor who captured the American public. Instead, he smirks in such a way that he looks evil, uncaring.

Furthermore, there’s an intentional eeriness to the bright orange, a certain irony that the bright orange exudes in the face of the poster’s dark subject matter. The black brings out the orange, making the color even more eye-catching and impossible to ignore. This, coupled with

45 Ibid.

text that is simple and bold, accusatory, gives the poster powerful visual command. Like many of Gran Fury’s other works, this piece chooses not to portray victims of AIDs, but instead unite their voices in a display of resistance. He Kills Me does this prominently by using the word “me,” specifically taking the voice of someone with the disease. The message is personal, meant to strike at the very core of viewers, making them complicit in the killings of real people. It’s not “He Kills Them,” or “He Kills AIDs Victims.” It’s more personal. “He Kills Me.”

This piece also reveals some of the more developed graphic design tendencies of Gran Fury. The target is not a full piece, eventually getting cut off by its frame, giving the print a design-like quality. It’s overt, obviously a target, but it also looks sleek, hinting at the emerging graphic design sensibilities of the 1980s. The orange circles are thick and bold and almost seem to induce dizziness.

Imagevirus, 1987

One of the most prominent pieces of art that came out of this time period was General Idea’s appropriation of Robert Indiana’s iconic 1964 pop-art image LOVE, which was created for the Museum of Modern Art’s Christmas card that year. 46

Robert Indiana, LOVE, 1967, screenprint, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, accessed April 11, 2017

46 Joshua Decter, "Infect the Public Domain with an Imagevirus: General Idea's AIDS Project.," Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 15 (2007).

It subsequently infiltrated culture and became ubiquitous, recreated as large, public sculptures and printed on postcards, keychains, napkins, and other goods.47 In 1987, General Idea was invited to contribute a piece to an amfAR fundraiser and so they recreated Indiana’s work in acrylic on canvas, altering the letters so that it read “AIDS” instead of “LOVE,” but sticking with the same color scheme and structure.48Though the piece started off as a singular work, the group created reincarnations of it on posters and sculptures, saturating cities like New York, San Francisco, Toronto, and Amsterdam with their image. This collective effort to spread the piece was titled Imagevirus

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

Appropriating other famous artwork was a tool that was used often to deal with the AIDs epidemic in the art world because it established the disease as something connected to the rest of the fabric of history, making people more likely to see it as something that should be addressed, like other historical tragedies, rather than to be blindly feared and ignored.49 Robert Indiana’s piece was the perfect vehicle for General Idea because it was so popular and recognizable. Part of the power and intention of Imagevirus was this ubiquity. It allowed the artists to combat one of the central problems with the AIDs epidemic: awareness. 50 Because the disease did not affect mainstream America, those who were not a part of the relatively small community affected by it were largely unaware of the reality of the epidemic.51 Much of what the average person knew about the epidemic was a result of hysteria and misinformation, and so the epidemic was met by a large part of the population with a huge amount of stigma, mystery, and fear.52 A September 1985 feature in Time Magazine entitled “The New Untouchables” covered this phenomenon, with the authors noting that “Anxiety over AIDS in some parts of the U.S. is verging on hysteria.” The piece provided multiple examples for this statement, but perhaps most illustrative is its account of New York City schools. The authors explained:

There are 946,000 children attending New York City schools, and only one of them an unidentified second-grader enrolled at an undisclosed school is known to suffer from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, the dread disease known as AIDS. But the parents of children at P.S. 63 in Queens, one of the city’s 622 elementary schools, were

49 Ibid.

50 Sarah E.K. Smith, General Idea Life and Work (Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2016), accessed November 17, 2016.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

not taking any chances last week. As the school opened its doors for the fall term, 944 of its 1,100 students stayed home.53

Reaching people who were so seized by this hysteria would have been no easy feat, which was why General Idea decided to start with something familiar to these audiences. By choosing an image that had already penetrated popular culture, General Idea had the perfect platform to spread their message about AIDs to the largely unaffected general public and invite them to confront what was happening to their neighbors and countrymen.

The spreading of the image throughout cities was also meant to imitate the spreading of a virus, specifically HIV. In this case, to see the piece is to be infected by it, making the viewer as powerless to the artists and their message as many victims of AIDs were to the disease. A.A. Bronson explained that the “intention with this logo was that it would…play the part of a virus itself...that it would spread within the culture and create a…visibility for the word ‘AIDS,’ so it couldn’t be swept under the carpet, which was…what was happening.” Furthermore, because the piece originates from the text “Love,” the artists created an unmistakable link between the two words, “Aids” and “Love.” General Idea maintained the same color scheme and font as Indiana, changing only the words, thus equating the two messages and emphasizing the victims as people deserving of empathy and love. At the time, there was a sizeable segment of the population that did not ignore AIDs, but instead saw it as a punishment from God for homosexuals.

Conservative activist Jerry Falwell espoused the idea that “AIDS is not just God’s punishment for homosexuals, it is God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals.”54 General Idea strove to combat this theory by equating the disease with kindness rather than contempt.

53 Evan Thomas, "The New Untouchables," Time Magazine, last modified September 23, 1985,

54 Brett C. Stockdill, Activism Against AIDS: At the Intersection of Sexuality, Race, Gender, and Class (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003), accessed December 15, 2016,

Stylistically, AIDS and Imagevirus play perfectly into the sleek, media aesthetic of the multitude of AIDs art. The colors are bold because Indiana meant for them to catch the eye. This serves General Idea well because the bright colors, coupled with the easily digestible stacked letters, seize the viewer with just a glance, and delivers the message: AIDs cannot be ignored. However, many in the AIDs community, and specifically in the artistic community, did not see the piece as political enough. Many artists of Gran Fury, who represented more of the younger generation than General Idea, intensely scrutinized Imagevirus. “In Gran Fury we were all about taking action and claiming an active opposition to AIDS. So when we saw the AIDS poster by General Idea, we thought it was so evil,” explains Marlene McCarty, a member of Gran Fury. 55 “To take AIDS and convolute it with the word “love” and not point in any other direction did not seem effective. In a way, we probably even felt that it was fueling the hysteria.

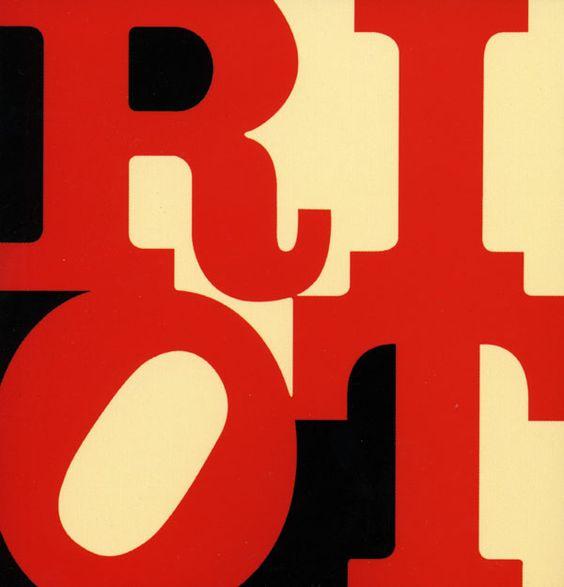

In an attempt to engage General Idea, Gran Fury created a more provocative and charged piece, replacing “AIDS” with “RIOT.” Unlike the previous incarnations, this did not begin as a painting, but instead a silk-screened crack-and-peel sticker. 56 The text was intended to recall the spirit of Stonewall, the riot that set off the gay rights movement two decades prior, and was unmistakably a moment of action. 57 The piece’s more active message catalyzed a conversation within the artistic community about the role of images in movements, with Gran Fury posing that “Art is not Enough,” that it must serve not only as a reflection of culture and opinion but a vehicle for it. 58 That it must be created with the intention of producing large, broad-based action.

55 Rachel Wolff, "Love, Robert Indiana," Departures, December 11, 2013, accessed December 15, 2016.

56 Susan Elizabeth Ryan, Robert Indiana: Figures of Speech (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 241, accessed December 15, 2016.

57 Ibid , 241.

58 Ibid , 241.

Of course, any assertion that art must take on more meaning than the artist may want is an opinion that is well disputed within the artistic community but the concept certainly fit the ethos of the group, which created art not for museums but for the urban fabric.

April 9, 2017

This is, perhaps, the greatest divide between the two groups. While both were made up of members afflicted with the illness and both created art intended to influence opinion, General

Idea never fully separated itself from the traditional vision of art as intended for museums. 59 They still tended to create largely meditative works that were uniquely tied to the identity of the three men that created the art, and most of their works, unlike Imagevirus, were exhibited solely within the walls of galleries and museums. Gran Fury, in contrast, saw itself not simply as an artists’ collective but as an advertising machine for Act Up, and as such they believed their art had an obligation to be opinionated, political, and catalyzing. 60

Magi© Bullet, 1992

Though much of the power of AIDs art came from its bold messaging and easilydistributable posters, it was not the only medium artists used to convey their varied messages. In General Idea’s 1992 installation Magi© Bullet, the focal point was not a print or any kind of text, but instead an exhibition space filled with silver balloons in the shape of pills.61 The piece was inspired by Andy Warhol’s 1966 exhibit Silver Clouds, which similarly used balloons in an enclosed space, but with the intention of creating a kind of ethereal joy and allowing viewers to interact with the art, challenging traditional views of what art could be. 62

Andy Warhol, Silver Clouds, 1966, installation, Denver Museum of Art, Denver, CO, accessed April 11, 2017

59 Ted Kerr, "Before there were memes, there was LOVE, AIDS, RIOT," Visual AIDs, accessed December 15, 2016, 60 Ibid.

61 Kim Conaty, "Print/Out: General Idea," Inside/Out, last modified April 18, 2012, accessed December 15, 2016.

62 Warhol, "Billy Kluver and Andy Warhol: Silver Clouds," The Warhol, accessed December 15, 2016,

General Idea again saw the power in appropriation, by taking a well-lauded piece and turning its intended message into something quite the opposite. Instead of joy, General Idea’s exhibit betrays a sense of dread, as the balloons, traditionally thought of as joy-inducing objects, are conflated with pills, traditionally associated with illness.

General Idea, Magi© Bullet, 1992, installation, traveling exhibition, accessed April 9, 2017

The balloons were left free to be touched by viewers, and eventually they would lose their helium and sink to the ground. Visitors were invited to take the fallen pills with them, thus continuing the tradition in AIDs art for the pieces to make their way outside of gallery walls and into the streets. Like the AIDS and RIOT pieces, and all the Gran Fury posters, the art was about the lives of real people, meant to be touched and felt personally, just as a human being should. By establishing a constant and immediate connection with viewers, allowing them to take them home and scatter them at their will, the art served as a reminder of the action that needed to take place.

However, in the image of pathetic, deflated pills sinking down to the floor is also a reminder that the pills can only do so much to help someone with AIDs, and yet they were the only solution at the time. Many artists hoping to capture the ephemeral nature and experience of AIDs used materials that would change over time. Most notably, artist Felix Gonzales Torres’s piece Untitled (Perfect Lovers) placed two clocks next to each other and allowed them to run out, noting that one would inevitably run out before the other. Like General Idea, Gonzales Torres used the natural tendencies of his medium to display the ephemerality of AIDs victims and the cures that have been posed for them.63Thus is the irony of the title Magi© Bullet. Pills were first described as “magic bullets” by turn-of-the-century German physician Paul Ehrlich as a way to combat pathogenic microorganisms, but General Idea makes it clear here that there is nothing magical about these pills. They deflate and decompose, as will the people they are meant to save. Furthermore, the term “bullet” has a double meaning here, because though it might refer to the pill, its conflation with violent and immediate death is unmistakable.

Of the piece, General Idea artist A.A. Bronson explained that “We were all surrounded by pills, and the pill became a kind of sculptural form that we turned into our art.”64 In fact, General Idea came back to the pill as a form of art again with their installation “One Year of AZT,” that including coffin-sized pills.

The Government Has Blood on Its Hands, 1988

Perhaps one of the best examples of AIDs art being used to catalyze political change is Gran Fury’s oft reincarnated 1988 poster The Government Has Blood on Its Hands. The original poster was created for an ACT UP demonstration on July 28, 1988, against the New York City

63 Conaty, "Print/Out: General," Inside/Out.

64 Ibid.

Department of Health and NYC health commissioner Stephen Joseph65 The poster, which originally read “The Government Has Blood on Its Hands One AIDs Death Every Half Hour” was then retailored to specifically call out Joseph. Joseph had publicly announced that only 50,000 New Yorkers had AIDs, although the number was closer to 200,000. 66 The announcement seemed the first step for a cut in AIDs funding, athough the city already had very few care services for AIDs patients as it was. Thus, ACT UP and Gran Fury declared war, changing the text on the poster to read “You’ve Got Blood on Your Hands Stephen Joseph…The Cuts In Aids Numbers is a Lethal Lie.”

65 Nicolas Lampert, A People’s Art History of the United States 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements (New York City, NY: The New Press, 2015).

66 Ibid , 247.

Gran Fury, The Government Has Blood on Its Hands, 1988, poster, New York Public Library Digital Collections, New York City, NY, accessed April 9, 2017.

The poster was again used when protesting then-mayor of New York City Ed Koch, who was widely viewed in the community as doing very little to combat the crisis. According to New York Magazine, “ Koch stood silent through years of headlines, obituaries, and deaths. He refused meetings with community members, Larry Kramer chief among them. Administratively, he created inter-departmental committees and appointed liaisons, but he gave them neither power nor resources to do anything real.”67 He pledged only $25,000 for AIDs care and research

67 David France, "Ed Koch and the AIDS Crisis: His Greatest Failure," New York Magazine, February 1, 2013,

68

combined by 1983, a number that paled in comparison to the $1,000,000 that San Francisco mayor Dianne Feinstein pledged, although that too was regarded as not high enough.

The poster was an unmistakable call to people in power to address the epidemic or be held accountable for the deaths caused by lack of care. By calling out politicians by name, they were able to direct the community’s activist efforts towards the people who could make a change, giving them a unified purpose. Like other Gran Fury posters, the text is bold and simple, visually integrated with the images and able to be read easily in the crowded streets of New York. In fact, posters were pasted all over the city, and members of Act Up took red buckets of paint around and pasted their handprints all over the city, another example of the uniquely tangible nature of AIDs art, meant to be felt, foster immediate connections. However, this piece is unique in that it goes beyond the poster, becoming even more personal, as the handprint can be recreated by anyone, not just the original artist, and thus can empower anyone to spread the urgent message.

As with many Gran Fury posters, the colors (here red, white, and black) are all very different from each other and stand in stark contrast beside one another, drawing the viewer's eye in a way that startles. In a serene calm of white in the background comes a jarring, red handprint, interrupting a blissfully ignorant society with an undeniable message. The handprint, a scarlet red, references blood, serving as a reminder of the true destruction that the disease causes. It is messy, haphazard, and conveys the image of a hand grasping at something and then slipping, a fitting representation of AIDs patients grasping at their last bit of life. People were not bleeding out on the streets as they might in a war, but the destruction wreaked is very similar and no less accessed March 21, 2017.

68 Ibid., 247.

important.69 It was an important statement to make, especially to those who were not connected to someone with AIDs and may not have had to face the way the disease decays a body. By forcing ordinary people in the streets to confront the blood was important, a reminder not only of the pain felt by their fellow citizens but also a warning that they, too, will have blood on their hands if they participate in the silence propagated by their governments.70

Art is Not Enough. Seize Power Through Direct Action, 1988

Though the artists of Gran Fury were empowered by their ability to spread their messages through art, they wanted to make it clear that it was not enough to hold a poster or press a bloody handprint to a wall. 71 To affect real change, the art had to lead to some form of action. This was one of the most prominent reasons that the artists chose to create such tangible art, and it was one of the reasons that, as artist Marlene McCarty stated, the group “spent years and years saying, ‘We’ll never exhibit in an art gallery. We aren’t doing that.’” For them it was not just about the art, it was about saving lives.

Thus, in 1988, the group created a poster, originally printed in The Village Voice, that read “Art is Not Enough. Seize Power Through Direct Action.” Later incarnations were more direct, reading “With 42,000 Dead /Art is Not Enough/Take Collective Direct Action to End the AIDs Crisis.” The Village Voice was a local newspaper that was read and created by New York’s creative communities, many of whom were afflicted by the disease. Thus, the piece would have mostly been circulated among sympathizers rather than critics or those seemingly ambivalent. In contrast, the New York Times was heavily criticized for not covering AIDs to the

69 Douglas Crimp, "Gran Fury talks to Douglas Crimp," Artforum International Magazine , April 2003, accessed November 17, 2016,

70 Ibid.

71Ibid.

extent that it should, and refusing to even print the word “gay”.72 The publication that originally printed the piece is important when analyzing the voice with which the text is conveyed. Much of AIDs art that includes text is told from a specific perspective, either from the gay community to those in power (“The Government Has Blood on its Hands”) or from members of the community to other members of the community (“RIOT”). This print in The Village Voice is defiant, speaking specifically to members of the community and calling them to action. The piece makes no effort to convert potential sympathizers or appeal to people in power. It is protomilitant, gearing the community up for their fight.

73

Gran Fury, Art is Not Enough. Seize Power Through Direct Action, 1988, print, The Village Voice, New York City, NY.

Still, however, the artists make specific choices to lead viewers to a way of thinking. The words stand out dramatically in the block of black that surrounds them, small but weighty in the

72 John D. H. Downing, Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements (New York, NY: SAGE, 2000), 139, accessed December 15, 2016.

73 Ibid., 139.

blank vastness of the background. The placement of the two non-text focal points, the person and the sign, in the piece is strategically uncomplicated and directed upwards, so that the Washington monument is thrown into focus, towering and awe-inspiring, a reminder of the American legacy and American values. Gran Fury is constantly reminding the reader that this travesty is taking place in; a country that had once promised to welcome marginalized groups from every corner of the world.

In fact, the face of the Washington monument serves as a reminder of the American Revolution, the civil rights movement, the suffrage movement, causes for which history has already decided who had the moral high ground. By placing a new protester there, Gran Fury frames the epidemic and gay rights as similar to those historic ones, asserting that the gay community also occupies this moral high ground.

74

Gran Fury at the New York Stock Exchange, 1989

In September of 1989, Gran Fury further pushed the boundaries of art, creating a kind of performance piece in the belly of the New York Stock change. The group created fake dollar bills, with text printed across the backs. Some said , ‘Fuck Your Profiteering. People are dying while you play business,’ others read “White Heterosexual men can’t get aids … Don’t bank on it,” and “Why are we here? Because your malignant neglect kills.” Finally, a small script was printed on all of them that read “Fight back. Fight AIDs,” and a Gran Fury signature. They snuck into the stock exchange and rained these bills onto the trading floor, stopping trading for the first time in history. 75

74 Ibid

75 Colucci, "Is Art Enough?,"

Gran Fury, Wall Street Money (backs), 1989, printed paper.

The art-protest was meant to be a statement against the problem of pharmaceutical pricegouging, one that was near to the heart of the gay community. 76 The dollar bills can be regarded as art by themselves, but it’s more inclusive to look at the entire demonstration coupled with the designed bills as a kind of performance art. The art-demonstration displays the unique relationship that Gran Fury held with Act Up. They were an activist group as well as an artistic collective, and allowed their art to be a puzzle piece in a much grander scheme. Thus the art is rarely ever self-indulgent, an attempt to display the talent of the artist. Instead, it is highly intentional.

The dollar bill performance is unique in the Gran Fury canon because it does not fit into the glossy, professionally-produced aesthetic that characterized the political posters they created. The bills were, in fact, created on a Xerox machine, printed in black and white on dollar-green

76 ActUp, "ACT UP Accomplishments and Partial Chronology," ActUp NY, last modified March 5, 2009, accessed December 15, 2016.

paper. 77 The ease of creation displays the raw anger of the everyday man affected by the disease.78 Like the bloody handprint of The Government Has Blood on Its Hands, it’s something that can be easily recreated, that empowers the people to participate, to protest. Further, like Imagevirus, the repetition of the bills holds significance because it mimics the spread of the virus and illustrates how much faster the disease multiplies than most people believed. The words on the back of the bills are clear, simple, uninterrupted by any sort of image, allowing the text to take center stage, making the language loud and accusatory. The message is unmistakable. Furthermore, it is significant that Gran Fury signs their name in elegant script on the front face of the dollar bill, blending in so well with the design of the dollar bill that one might not even recognize it. This tactical choice establishes the collective’s campaign and the larger community of gays afflicted by AIDs as part of America’s foundations.79 The use of the ubiquitous dollar bill is especially important because much of the problem with the epidemic was that it was not receiving enough funding for medical research. Act Up decided that forcing the moneymen to see the problem was an important step. 80 To force the public to see the sad irony in the fact that it took money, instead of lives lost, for people to wake up and pay attention to the epidemic. It is a seething critique of American values and the rampant, shameless profiteering taking place.81

77 Colucci, "Is Art Enough?,"

78 Crimp, "Gran Fury”.

79 Ibid.

80 Jennifer Kabat, "Never Enough AIDS activism now and then – 25 years of ACT UP and Gran Fury," Frieze, September 1, 2012, accessed December 15, 2016.

81 Ibid.

One Year of AZT, 1991

In 1987 AZT became the first drug in the United States that was approved to treat those with HIV, thus delaying the onset of AIDs. 82 It was quite an important achievement and provided some real progress after six years, during which some AIDs patients had grown so desperate that they would often attempt bootlegged pills and remedies that often caused more harm than cure. However, the pills had their downside. Besides the fact that they did not work for everyone with AIDs, they also contained high levels of toxicity.

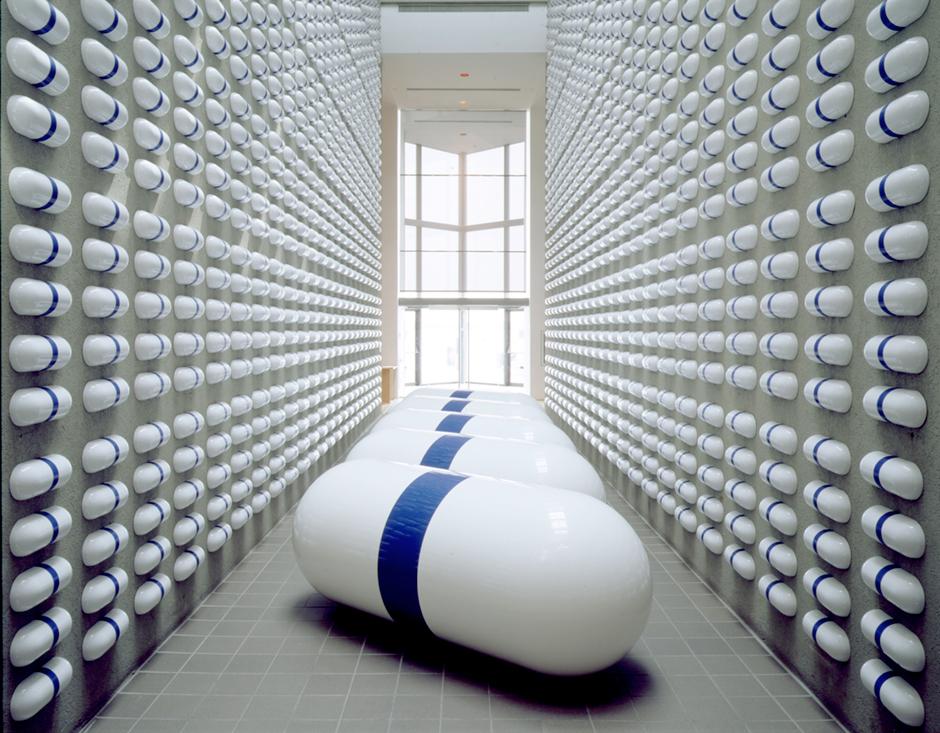

General Idea dealt with AZT in its 1991 installation One Year of AZT. Artist Felix Partz had started taking the drug a year earlier; one year’s regimen totaled 1,825 pills. 83 Thus, the group filled a room with plastic capsules, white pills divided by blue stripes, specifically 1,825 to correspond with Partz’s dosage. 84A.A. Bronson explained that “Our life was full of pills, our apartment was full of pills … so they became part of our work … Your watch is ringing little bells every two to four hours and you have to take two of this and four of that.… [The work] was to create that environment, a pill environment. To reproduce that feeling. To give it a physical sense of what it’s like to be surrounded by pills … a very clinical atmosphere.”85 Indeed, the walls of the room are covered in rows and rows of pills, from a distance looking like a morgue.

82 Michael Byrne, "A Brief History of AZT, HIV's First 'Ray of Hope,'" Motherboard, March 21, 2015, accessed December 15, 2016,

83 Sarah E.K. Smith, General Idea Life and Work (Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2016), accessed November 17, 2016,

84 Ibid., 44.

85 Ibid., 44.

General Idea, One Year of AZT, 1991, 1,825 units of vacuum-formed styrene with vinyl wallmounted capsules, National Gallery of Canada, Ottowa, accessed April 9, 2017

Like many of the other pieces of AIDs art examined, repetition plays a key role here. It not only creates an aura for the viewer, it is reminiscent of the spread of the disease, and the enormous amount of pills (for Partz, 1, 825 per year) it takes to fight AIDs. In fact, General Idea designed the exhibit to function as a calendar, with the pills organized in daily and monthly groups.

86 The exhibit is usually exhibited with General Idea’s other installation One Day of AZT

87 While One Year of AZT lines the walls of the room, One Year of AZT, which consists of

86 Ibid , 45.

87 Ibid , 45.

five large pills (the daily dosage of the drug) lined in the center of the room. The pills are a little larger than the size of human bodies, and thus look like coffins. The rooms are white and still, already eerie, and the coffin-like pills lend the exhibits an ominous undertone.

Fin de Siècle, 1990

General Idea, though more traditional in comparison to Gran Fury which never exhibited in galleries, was very experimental when it came to the kinds of gallery installations they created. In 1990 they exhibited Fin de Siècle, an installation of expanded polystyrene and stuffed baby seals. The artists used three hundred 120 x 240 centimeter sheets of Styrofoam to create a landscape of ice across a room, and scattered three baby seals in the midst. The piece, when viewed, is reminiscent of a museum diorama.

Caspar David Friedrich, The Wreck of Hope, 1824, oil on canvas, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany, accessed April 11, 2017

The piece is a reference to the Romantic landscape painting The Wreck of Hope created in 1824 by German artist Caspar David Friedrich.88 The painting depicted the icy, jagged landscape of ice in the Arctic Ocean, and General Idea’s mimicry of the painting points to a larger trend of AIDs artists using appropriation to make their points. Much of the gay rights movement was about challenged preconceived notions and ideas about what society was supposed to look like. The AIDs epidemic made that particularly difficult and called for an even more dramatic upheaval of the norm. By taking well-established pieces and turning them on their heads AIDs artists were able to subtly alter audience perspectives by asking them to see things in a new light.89 In Fin de Siècle General Idea achieves this by utilizing the inherent whiteness of the Freidrich scene. The whiteness not only used to mimic the painting and display an Arctic scene, but also a symbol of innocence and purity, an impression many did not have of the gay community at the time. 90 General Idea was reshaping perceptions.

88 Ibid , 42.

89 Ibid , 42.

90 Scott, "AIDS is the General”.

Here, the viewers play an integral part in the piece. They must decide: what is the fate of these seals? Is their scattering playful, are they on the precipice of disaster? The polystyrene ice, like the ice of the painting, is sharp, wicked almost, seeming to insinuate imminent danger. The uncertainty is certainly familiar for those with AIDs, and, in fact, the piece is intended to be a self-portrait of the three artists of General Idea. 91 Jorge Zontal explained that the piece was meant to represent the artists emotionally, “adrift in uncontrollable circumstances,” as were many AIDs patients. The innocent nature of the seals (it is no accident that they are seal pups) as well as their status as an endangered species emphasizes the fact that in modern society, some lives are more valuable than others. Some deaths people will pay attention to, but some deaths even the President of the United States will ignore. Zontal explained, “It’s easier to sell ‘save the seals,’ or ‘save the children with AIDS because they’re cuter, rather than three middle-aged homosexuals.” 92

Legacy

The AIDs art movement was unique because it was saddled with more than simply a desire to express emotions about loss or death. The artists were aware that their art would inevitably address not just human emotions, but also the current nature and economics of health care, the politics and social implications of marginalizing minority groups, and the coopting of scientific research for the purposes of creating divides along the lines of gender, race, and class. It is this responsibility that allowed for the brazen, loud art of Gran Fury, and for the quietly powerful art of General Idea.

As graphic design became a budding art form with the rise of personal computers in the

91 Ibid , 42.

92 Ibid , 42

1990s, Gran Fury and General Idea became predecessors to an art form that is built on the techniques of color, line and text that they both used heavily, as well as the idea of using many to create a singular message. 93 Furthermore, the groups’ use of already popular images as vehicles to deliver a message, such as Indiana’s Love or Warhol’s Silver Clouds, has become popular with the rise of the internet.94 Most prominently, in 2015 during the Obergefell v. Hodges case contesting marriage equality, many used photoshop to spread an image of the Human Rights Campaign’s logo in pink and red to symbolize a bid for equality.95 The AIDs activist group Visual AIDs even turned LOVE, RIOT, and AIDS all into red and pink, thus using their context for a new message.96

When AIDs was no longer a death sentence with the introduction of HAART (Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy) in the mid 1990s, the AIDS art movement naturally lost that specific and unique aspect that encouraged its creation and proliferation. 97 Gran Fury disbanded in 1995, a year before one of its members, Mark Simpson, died of the disease.98 A year earlier, two of the three General Idea members, Jorge Zontal and Feliz Partz, died of AIDs, effectively ending the collective, although AA Bronson continues to work as an artist, curator, and perhaps fittingly, a magazine publisher.99 Creating until they could create no longer, these men memorialized not only themselves and their experiences, but an entire segment of society that so

93 Clark, Art and Propaganda

94 Ibid.

95 Ibid.

96 Ibid.

97 Byrne, "A Brief”.

98 Colucci, "Is Art Enough?.”

99 Ibid.

many in the establishment were prepared to simply let go. Their contributions have expanded outside the realm of the AIDs art, and into modern art, activism, and graphic design.

Bibliography

ActUp. "ACT UP Accomplishments and Partial Chronology." ActUp NY. Last modified March 5, 2009. Accessed December 15, 2016. http://actupny.com/actions/index.php/thecommunity.

Created by ActUp, this timeline on the website provides a comprehensive chronology of all of ActUp's events and protests in all their years of activity. Particularly important here is the description of the New York Stock Exchange protest. Because it comes directly from the source, it is easy to garner the intent and the satisfaction that ActUp felt from their art-performance that day.

Buckley, William F., Jr. "Crucial Steps in Combating the Aids Epidemic; Identify All the Carriers." New York Times. Last modified March 18, 1986. http://www.nytimes.com/books/00/07/16/specials/buckley-aids.html.

Written at the time of the epidemic, this article provides a unique insight into public attitude towards the disease in real time. Specifically, the author is direct, often caustic, in his treatment of those inflicted, suggested they must all be somehow "marked" for the benefit of the public. This is the perfect example of the extent of fear that AIDs caused and the reactions that this created in a group of people who were fortunate enough to not have to go through the disease personally.

Byrne, Michael. "A Brief History of AZT, HIV's First 'Ray of Hope.'" Motherboard, March 21, 2015. Accessed December 15, 2016. http://motherboard.vice.com/read/happy-birthdayto-azt-the-first-effective-hiv-treatment.

This article proves informative in understanding exactly how the hysteria of the AIDs epidemic eventually came to a close with the discovery of AZT. The article explains the process by which the drug was discovered and how it was phased into use, ensuring that AIDs would no longer be a death sentence. It provides great context to understanding the period of AIDs and how the art changed after death was not so prevalent an issue in the artistic community.

Children, What Do You Know of the Führer. Photograph. Accessed April 11, 2017. http://www.master-of-education.org/10-disturbing-pieces-of-nazi-education-propaganda/.

Clark, Toby. Art and Propaganda in the Twentieth Century: The Political Image in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1997.

This book as an enlightening look at the history of political art, complete with a timeline that served to ground this paper's research and full-page illustrations so that it was easy to make out in the works what analyses Clark what written about them. The book traces the links between art and politics through time, giving a greater understanding of the history between the two, and how their relationship can manifest, as either an ally of the state, in protest of it, or to garner its attention. Informative both as a history and as an art critique, Clark's book provides a backbone needed to analyze the art of the AIDs era critically.

Colucci, Emily. "Is Art Enough? Gran Fury in Perspective." Hyperallergic, February 21, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2016. http://hyperallergic.com/46881/gran-fury-read-my-lips-

80-wse-nyu/.

This article provides an in depth analysis of the legacy of Gran Fury while also allowing original members to weigh in on the groups progress though out the years. Specifically, original Gran Fury member Marlene McCarty provides great perspective on the intention behind many of the pieces and what drove so many of the individual artists, and how their voices where able to resonate as a collective.

Conaty, Kim. "Print/Out: General Idea." Inside/Out. Last modified April 18, 2012. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/04/18/printoutgeneral-idea/.

Conaty, a Curatorial Assistant at the Department of Prints and Illustrated books at the Museum of Modern Art discusses the intent behind General Idea's Magic Bullet exhibition. She discusses the technical aspects of the installation and explains the metaphors behind the dynamic piece of art, allowing for a better understanding of the unique, personal flavor of General Idea's work.

Crimp, Douglas. "Gran Fury talks to Douglas Crimp." Artforum International Magazine, April 2003. Accessed November 17, 2016. http://www.actupny.org/indexfolder/GRAN%20FURY_on_ARTFORUM.pdf.

. Introduction to AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, 1-16. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1987. Digital file.

This book provides an in-depth look at the cultural impact of the AIDs epidemic, from art, to literature, to theater. It is a wonderful resource for situating oneself in the time period of the 80s, when such a large community was so greatly affected by the disease. Crimp himself is a professor of art history who spent much of his professional life following the impact of Gran Fury, and thus, a large portion of the book discusses the impact of AIDs on art, specifically that collective.

Decter, Joshua. "Infect the Public Domain with an Imagevirus: General Idea's AIDS Project." Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 15 (2007): 96-105. http://puffin.harker.org:2076/stable/pdf/20711645.pdf.

This article gives the reader insight into the artistic intent behind Imagevirus, understanding why unbiquity was so important to the creators. It also examines the cultural impact of the piece, and covers the Gran Fury response to Imagevirus. It also allows the artists of General Idea to respond to the criticism of their piece, allowing for a well-rounded examination of a cultural icon.

Downing, John D. H. Radical Media: Rebellious Communication and Social Movements. New York, NY: SAGE, 2000. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=tJRIWRPUr8gC&dq=gran+fury+new+york+stock+e xchange+dollar+bills&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

This book discusses the media's role in aiding social movements, and proved particularly informative in its coverage of The Village Voice, which often provided a platform to Gran Fury. Specifically, the book discusses the print created by Gran Fury "Art is not Enough." It discusses how The Village Voice allowed Gran Fury the space to send a

message that was not being covered in the mainstream media, specifically the New York Times. Furthermore, the book discusses Gran Fury's protest at the New York Stock Exchange in it's attempt to highlight moments where other parties attempted it make up for a lagging media.

Felshin, Nina. But Is It Art?: The Spirit of Art as Activism. Seattle: Bay Press, 1995. A combination of essays analyzing political art through the ages, But Is It Art?: The Spirit of Art as Activism was a very informative resource to help me to understand what exactly qualifies art as "political" or "activist." Specifically, Felshin included an essay on Gran Fury, which served to better elucidate the motivations behind the explicit choices the artists in that collective made in their works, as well as to illuminate the history behind the organization. The essays are penned by a variety of qualified art critics and historians, and are compiled by curator and writer Nina Felshin of Wesleyan University.

Finkelstein, Avram. "The Silence=Death Poster." LGBT@NYPL. Last modified November 22, 2013. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/11/22/silence-equals-death-poster.

Avram Finkelstein, a founding member of Gran Fury, writes for the New York Public Library about the Silence=Death poster, often considered the seminal work of Gran Fury. He discusses the origins of the poster, the group's thought process in creating it, and explains the situation that caused the collective to believe it was necessary in the first place. He details the stylistic elements of the poster, explaining previous working incarnations of it, and why specific choices were made.

France, David. "Ed Koch and the AIDS Crisis: His Greatest Failure." New York Magazine, February 1, 2013. Accessed March 21, 2017. http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/02/koch-and-the-aids-crisis-his-greatestfailure.html.

The article provides a comprehensive outline of New York City mayor Ed Koch's attempts to combat AIDs, or lack thereof. France argues that Koch did very little, considering his power, to help AIDs victims, the numbers of which were only growing while the mayor was in office. He meticulously chronicles the mayor's spending on AIDs, as compared to other public figures, and chronicles his public statements. He puts them in context as well, holding other influential entities accountable as well, such as the New York Times, noting that the newspaper refused to print the word "gay" and thus fueled the stigma that Koch refused to combat.

Friedrich, Caspar David. The Wreck of Hope. 1824. Oil on canvas. Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany. Accessed April 11, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sea_of_Ice#/media/File:Caspar_David_Friedrich__Das_Eismeer_-_Hamburger_Kunsthalle_-_02.jpg.

General Idea. AIDS. 1987. Acrylic on canvas or poster. Private collection, Chicago, IL. Accessed April 9, 2017. http://www.aci-iac.ca/general-idea/key-works/AIDS.

Fin de siècle. 1990. Acrylic, glass, straw, expanded polystyrene. Private collection, Turin, Italy. Accessed April 9, 2017. http://www.aci-iac.ca/general-idea/key-works/fin-

de-siecle.

Magi© Bullet. 1992. Installation. traveling exhibition. Accessed April 9, 2017. https://artmap.com/kunsthallezurich/exhibition/general-idea-2006.

. One Year of AZT. 1991. 1,825 units of vacuum-formed styrene with vinyl wall-mounted capsules. National Gallery of Canada, Ottowa. Accessed April 9, 2017. http://www.aciiac.ca/general-idea/key-works/one-year-of-azt.

Gober, Robert. "Gran Fury." Bomb - Artists in Conversation. Digital file. 1991 interview with Gran Fury, talks about use of media techniques

Gran Fury. Art is Not Enough. Seize Power Through Direct Action. 1988. Print. The Village Voice, New York City, NY.

. "Good Luck...Miss You- ~ -Gran Fury." Act Up NY. Last modified 1995. Accessed November 17, 2016. http://www.actupny.org/indexfolder/GranFury1.html.

The Government Has Blood on Its Hands. 1988. Poster. New York Public Library Digital Collections, New York City, NY. Accessed April 9, 2017. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-3ebe-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

. He Kills Me. 1987. Offet lithograph. Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY. Accessed April 9, 2017. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/4809?locale=en.

. Let the Record Show . . . 1987. Installation. New Museum, New York City, NY. Accessed April 9, 2017. http://archive.newmuseum.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/3294.

. RIOT. 1987. Poster. The New York Public Library Digital Collections, New York City, NY. Accessed April 9, 2017. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-532ba3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Wall Street Money (backs). 1989. Printed paper.

Women Don't Get AIDs, They Just Die From It. 1991. Poster. Brooklyn Museum, New York City, NY. Accessed April 9, 2017. http://brooklynmuseum.tumblr.com/post/134344539727/the-art-collective-gran-furyinstalled-this.

Green, Jesse. "When Political Art Mattered." The New York Times (New York, NY), December 7, 2003. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/07/magazine/when-political-art-mattered.html. Jesse Green describes the personal, visceral impact of the famous Silence=Death poster by Gran Fury in this article while also exploring the period it was created as a time when resistance through art truly made a different. Green discusses the origins of political art in the 80s, linking it to the AIDs epidemic and attributing the fact that the disease affected

such a cultured, activist-oriented, and artistic section of the community to the rise of powerful artistic resistance.

Heller, Steven. Graphic Intervention: 25 Years of International AIDS Awareness Posters: 19852010. Boston, MA: The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 2011. http://puffin.harker.org:2302/ic/bic1/AcademicJournalsDetailsPage/AcademicJournalsDe tailsWindow?disableHighlighting=&displayGroupName=Journals&currPage=&dviSelect edPage=&scanId=&query=&source=&prodId=&search_within_results=&p=BIC1&mod e=view&catId=&u=harker&limiter=&displayquery=&displayGroups=&contentModules=&action=e&sortBy=&documentId=GALE% 7CA251379234&windowstate=normal&activityType=&failOverType=&commentary=. This article examines the influences of graphic design in the art of the AIDs epidemic. It reflects on the use of symbolism, color, and shape to create a type of art that was half advertisement, posting that graphic design helped the artists, but was also in turn developed by those artists, advancing the medium as whole.

. "How AIDS Was Branded: Looking Back at ACT UP Design." The Atlantic, January 12, 2012. Accessed December 15, 2016. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/01/how-aids-was-brandedlooking-back-at-act-up-design/251267/.

Heller provides an analytical look a the stylistic principles employed in Gran Fury's artwork to better explain the reasoning behind the slick, media-like images that came to represent the AIDs epidemic, even outside the art world. A large part of the article consists of an interview with Loring McAlpin, a former member of Gran Fury who provides great insight into the motivations behind some of the most important pieces that the group created.

Higby, Gregory. The Inside Story of Medicines: A Symposium. Madison, Wisconson: Amer. Inst. History of Pharmacy, 1997. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=gzH4DlrVpmkC&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=MAgic +Bullet+general+idea&source=bl&ots=Nv4TGX3Q1&sig=shnx7PkN1kaePy6BTt8nNLgFuHk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiujeWz_f TQAhXHlJQKHd27DF4Q6AEITzAN#v=onepage&q=MAgic%20Bullet%20general%20 idea&f=false.

This book provided brief context on the history of the term "magic bullet." Understanding its origins allows for a nuanced understanding of General Idea's installation piece of the same name.

Hume, Christopher. "Burden of AIDS gives rise to art as social activism." The Toronto Star (Toronto), December 2, 1993, WO12. http://hh7kl7za7m.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.882004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF8&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fsummon.serialssolutions.com&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ff mt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.atitle=Burden+of+AIDS+gives+ri se+to+art+as+social+activism&rft.jtitle=Toronto+Star&rft.au=Christopher+Hume+TOR ONTO+STAR&rft.date=1993-12-

02&rft.pub=Torstar+Syndication+Services%2C+a+Division+of+Toronto+Star+Newspap ers+Limited&rft.issn=0319-0781&rft.externalDocID=519087301¶mdict=en-US. This article discusses the art of the AIDs epidemic in relation to social justice, posing the thesis that due to the political bubble that the art was created in, it had no choice but to adopt a message. The article references both Gran Fury and general Idea, drawing a line between them with regards to their feelings of obligation towards viscerally altering social perspectives.

Indiana, Gary. "From Love to AIDS: The Death & Life of General Idea." The Village Voice (New York, NY), December 5, 1995, 31. http://puffin.harker.org:2390/docview/232176088?pqorigsite=summon&http://search.proquest.com/ip.

In this article, Indiana gives readers a comprehensive look at the life and legacy of General Idea. He provides an extensive history of the three members and their intentions coming into the project, highlights the group's most important pieces, and discusses their influences and situations that lead to the creations of those works. The article provides great context in understanding the group more intimately.

Indiana, Robert. LOVE. 1967. Screenprint. Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Accessed April 11, 2017. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/68726?locale=en.

Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Chicago, IL: University Of Chicago Press, 2006. Digital file. In this book, David K. Johnson, PhD., associate history professor at the University of South Florida, examines the little-told story of the mass firings of homosexuals from the United States Government in the 1950s. He contends that behind the prominent Red Scare was a strict persecution and elimination of gays and lesbians employed at some of the highest levels of government. His works provides context for the examination of the AIDs art as "fighting-back" against a long history of persecution. Specifically, it provided insight into the use of the color purple in AIDs artwork and its importance as a color to the homosexual community.

Kabat, Jennifer. "Never Enough AIDS activism now and then – 25 years of ACT UP and Gran Fury." Frieze, September 1, 2012. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://frieze.com/article/never-enough?language=de.

Kabat describes in intricate detail the staging of the Act Up protest at the New York Stock Exchange, allowing the viewer to more accurately understand and picture the motives of the protesters while also simply giving an accurate account of what actually happened, given that the incident was so sensationalized in the press. Kabat makes it apparent that such a spectacle was required to gain the attention of moneymakers who could not otherwise be motivated to pay attention.

Kerr, Ted. "Before there were memes, there was LOVE, AIDS, RIOT." Visual AIDs. Accessed December 15, 2016. https://www.visualaids.org/blog/detail/before-there-were-memesthere-was-love-aids-riot.

Ted Kerr discusses in this article the dilemma that many artists faced when creating

working during the AIDs epidemic. He details how some, like Gran Fury, believed that art had an obligation to be political and to instigate change, while others, like General Idea, allowed their beliefs to permeate their pieces without the intent of action. This helps to draw a distinction between the two groups and allows for a more informed analysis of their intentions and how they manifest in the pieces of work.

Kester, Grant H. The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011. Digital file. This book proved invaluable in its explanation of a history of art-groups that create collectively rather than as individual people. From The Blue Rider to General Idea, Kester provides his readers with an in-depth exploration of the way that art-groups operate, and the way that their dynamics have changed over the years, especially given that what they are creating for changes with every new decade.

Lampert, Nicolas. A People’s Art History of the United States 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements. New York City, NY: The New Press, 2015. This book provides a comprehensive look at American art that was used in alternative ways, rather than simply created for honor in a museum. Specifically the book talks about Gran Fury's series of posters attacking various government authorities for refusing to admit the extend of the AIDs epidemic. The book analyzes the tools that the collective used to get their message across, including color, form, typography, and graphics.

The New York Times (New York City, NY). "Gran Fury, Guerrilla Girls, Barbara Kruger: Bus shelters and billboards New York City." March 1991, C30. http://puffin.harker.org:2390/docview/108812279?pq-origsite=summon.

Covering a history of feminism in art, this article in part explores the Gran Fury piece, "Women Don't Just Get AIDs. They Die From It." The article proved informative in situating the piece not only within the history of AIDs, but also within the history of women's rights. It allows readers to view the piece as a liberation for women for whom AIDs meant even less control of their own bodies, a reclaiming of their rights and an announcement that they will no longer remain silent.

Pollack, Barbara. "DOCUMENT, PROTEST, MEMORIAL: AIDS IN THE ART WORLD." ARTNEWS, May 5, 2014. http://www.artnews.com/2014/05/05/document-protestmemorial-aids-in-the-art-world/.

In this interesting retrospective, Barbara Pollack interviews current curators of AIDs exhibitions and some of the artists involved in the creation of the works in order to elicit what exactly made the movement so unique and special. She analyzes the legacy of the artwork an the significance of the time period in which the pieces were created, while also allowing other prominent voices of the era to speak for themselves, creating a powerful and informative introduction to AIDs art.

Poyner, Rick. No More Rules: Graphic Design and Postmodernism. London, UK: Laurence King Publishing, 2003. Accessed December 15, 2016.

https://books.google.com/books?id=lliBuozeoOgC&dq=women+don%27t+get+aids+the y+just+die+from+it+poster+gran+fury&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Poyner provides a stylistic analysis of many of Gran Fury's pieces, pointing out the techniques that makes so many of the works so compelling and successful in spreading their message. Particularly, he discusses their poster "Women Don't Just Get AIDs. They Die From It," highlighting the symbolism and color usage that creates such a powerful piece of propaganda art.

Press Release. "General Idea at Mai 36." Contemporary Art Daily, September 4, 2009. Accessed November 17, 2016. http://www.contemporaryartdaily.com/2009/09/general-idea-at-mai36/.