2014-15

Mitra FAMILY GRANT Recipient

Understanding Gender Differences in Depression: The Evolution of Rumination and Co-Rumination in the Midst of the Social Media Revolution

Stanley Xie, Class of 2015

UNDERSTANDING GENDER DIFFERENCES IN DEPRESSION: THE EVOLUTION IN OUR UNDERSTANDING OF RUMINATION AND CORUMINATION IN THE MIDST OF THE SOCIAL MEDIA REVOLUTION

Stanley Xie

Mitra Scholar Paper

Ms. Kelly Horan and Ms. Susan Smith April 13, 2015

Abstract

This paper reviews the important developments in the field of rumination, a common emotional coping strategy employed by depressed individuals, and new avenues of research that have been and should be studied in light of the burgeoning presence of social media in our everyday lives. Rumination is characterized by a single-minded concentration on the causes of depression that immobilizes individuals and prevents them from actively seeking solutions to these problems. Within the field of depression, rumination has helped clarify the causes of the robust gender and age differences commonly observed in the disorder. More recently, researchers have begun developing the concept of co-rumination—a social form of rumination— in the hopes of creating a framework for understanding rumination in the context of the growing avenues of communication available to society. Finally, this paper discusses important future avenues of research in the rumination and co-rumination fields, proposing that the two constructs, facilitated by social networking, can significantly alter the nature of friendships held by depressed individuals.

Introduction

Depression affects over 350 million people every year and is the most prevalent cause of disability around the world (World Health Organization, 2012). Lying at the intersection of neuroscience and psychology, the disorder presents an interesting and complex problem for researchers to solve; despite decades of research, the disorder remains a complex condition of the human psyche with differing manifestations of symptoms and no panacea (DSM 5, 2013). Though the causes of depression remain unclear, this paper seeks to elucidate a particularly promising avenue of research into a cognitive cause of depression—rumination.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013) characterizes a major depressive episode as a two-week period during which an individual experiences five or more of the following symptoms: a depressed mood persisting throughout the majority of the day (in children and adolescents, this depressed mood may manifest itself as an irritable mood), a pronounced reduction in enjoyment of activities during the day, abnormal changes in weight (5% of body weight in a month) or appetite, insomnia or hypersomnia (excessive tiredness), reduction or agitation of motor functions, lack of energy or fatigue, diminished self-esteem or unwarranted feelings of guilt, inability to think or concentrate, or repeated thoughts about death or suicide (DSM-5, 2013). Such an extended list of symptoms is a testament to the complexity and nuance with which researchers must approach the study of depression. Indeed, Patricia Ainsworth (2000) discusses over ten different theories that attempt to explain the underlying factors governing depression, categorizing them into two large subgroups—neurobiological theories and psychosocial theories.

There are four prominent neurobiological factors believed to cause depression (Ainsworth, 2000). First, Ainsworth discusses how an individual’s genes have been shown to

predict depression, a topic stemming from the field of behavioral genetics, the study of ways in which an individual’s genes can impact their behavior. In twin studies, such a genetic susceptibility has been clinically confirmed, as children with one parent having major depressive disorder are 25 to 30 percent more likely to have a mood disorder and those with both parents having major depressive disorder are 50 to 75 percent more likely to have a mood disorder. Second, researchers have also taken an interest in the influence of neurotransmitters on an individual’s experience of depression. In fact, a low level of serotonin is often one of the best predictors for depression in an individual (Owens & Nemeroff, 1994; Nemeroff, 2009). For example, Owens and Nemeroff (1994) observed significantly reduced levels of 5-HT (serotonin) transporters and receptors in postmortem brain tissue of individuals who had committed suicide or who were battling depression. Recently, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly turned to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), which allow extracellular serotonin to remain in the blood for longer periods of time, to combat depression. However, the effectiveness of SSRIs have constantly been under scrutiny, as studies have found them to be largely ineffective at helping patients who display only moderate symptoms and, quite surprisingly, that they may even increase rates of suicide for adolescents battling depression (Fournier et al., 2010; Garland, 2004). Third, the neurohormonal theory closely mirrors the neurotransmitter theory believing that abnormal levels of hormones (as opposed to neurotransmitters) such as sex hormones or growth hormones may bring about deleterious effects upon depressed individuals. This theory may explain the sudden increase in depressed children during adolescence as it is precisely the aforementioned hormones that are in flux during such a period of time. Others believe that the changing levels of myelination in the brain’s frontal lobe increase an adolescent’s risk for depression (Steingard et al., 2002). Finally, researchers believe that the

biological rhythm of an individual can influence their progression through depression. In particular, an abnormal Circadian Rhythm is well documented in clinical studies of depressed individuals (Zee et al., 2013).

On the other hand, psychosocial theories regarding depression often tackle the more intangible aspects of an individual’s daily life. These can be categorized into four different categories. First, environmental theorists posit the straightforward belief that external events (e.g. a traumatic life event) influence an individual and his/her depression. In particular, researchers have found that experiences of stressful life events during adolescence correspond with higher levels of both adolescent and adult depression, likely due to the phenomena of stress sensitization, whereby previous experiences of stress renders the limbic, or emotional system of the brain, more sensitive to future stressful stimuli (Shapero et al., 2014). Second, behavioral theories attempt to explain depression in the context of how individuals respond and deal with the environment around them. For example, behaviorists believe that social awkwardness or a lack of social support exacerbate the symptoms of depression. Following a similar avenue of research, cognitive theories highlight the importance of how individuals think about themselves and the world around them—those who are pessimistic are more prone to be depressed (Beck, 2002). Finally, studies of the interpersonal interactions between individuals have also been effective in understanding the causes of depression.

Arising from a mélange of the aforementioned causal factors, one of the most intriguing facets of depression is its drastically higher prevalence among females than males (NolenHoeksema, 1990). In fact, studies have shown that females are nearly twice as likely as males to be diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) (Reinherz et al., 1993; Essau et al., 2010). Professors Susan Nolen-Hoeksema (1999) and Benjamin Hankin (2006) have independently

found that this pronounced gender difference develops during adolescence, an important period of growth and development, along with self-discovery and self-introspection. Determining the factors that bring about the gender differences in depression has proven exceedingly difficult, as they are often influenced by the complex interweaving of societal expectations, cross-gender interactions, hormonal activity, and unexpected life events associated with the transition from youth to adulthood, further complicating the narrative of depression (Essau et al., 2010). One body of literature seeking to understand depression and its gender differences centers around the concept of rumination—when an individual focuses excessively upon the reasons and outcomes of his/her distress without actively attempting to address the root causes of the situation—an amalgamation of cognitive and behavioral coping mechanisms (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999).

Examples of rumination include idle thoughts about negative daily events, worries about how a depressed mood may impact job performance, and constant speculation about factors contributing to a depressed mood (Jackson, 2001).

Rumination poses a particularly relevant and interesting construct and mechanism for understanding depression for four main reasons. First, researchers have demonstrated that rumination correlates strongly and positively with an individual’s susceptibility to depression and the duration of their depressive symptoms (Jackson, 2001). Second, rumination appears to facilitate the gender differences in depression, as studies that controlled for gender differences in rumination find the resulting statistical gender differences in depression nonsignificant (Jackson, 2001). Third, the ruminative responses of a depressed individual closely mirror those of structured problem solving, with only slight deviations in behavior. Psychiatrists often encourage patients to actively seek, understand, and communicate their feelings and reasons for distress, yet such advice can often paradoxically resemble the basic symptoms of rumination—the constant

rehashing of issues seen as an exacerbating influence on one’s depression. Fourth, the act of rumination has grown and changed dramatically over the past decade, as social media reshaped the nature of how individuals communicate their thoughts and feelings with others. Indeed, the social media revolution has intensified the research upon another form of rumination — corumination — the rehashing and discussing of reasons for one’s distress in the presence of other individuals, a process rendered exponentially easier with the advent of social media websites like Facebook and Gmail (Rose, 2002).

This paper will review the literature surrounding rumination and co-rumination and its impact on the gender differences in depression from the early 1990s to the present; furthermore, in light of the social media revolution that has increasingly influenced the nature of adolescent communication, this paper will discuss avenues of future research in the field, focusing on the unique impact that social media will have on rumination and co-rumination in adolescents and how it will influence gender differences in depression.

The Roots of Rumination

Beginning in the late 1970s, researchers began turning their interests towards the thought processes that could be associated with depression (Smith & Greenberg, 1981). During this time, parallels between depression and the concept of self-focused attention began to form, as studies of self-attention alluded to its influence on the duration and extent of depression (Rehm, 1977; Kanfer and Hagerman, 1981; Smith and Greenberg, 1981). In 1981, Smith and Greenberg established a statistically positive relationship between depression and self-focused attention. Further studies demonstrated that depressed individuals experienced self-focused attention for much longer periods of time after a failure as compared to a nondepressed individual (Greenberg & Pyszczynski, 1986). Not surprisingly, increasing levels of self-focused attention were also

correlated with greater pessimistic thoughts as well as greater levels of negative memory bias in depressed individuals (Pyszczynski, Holt, & Greenberg, 1987; Pyszczynski et al., 1989).

The first connections between self-focus and rumination were made in 1990, when Wood, Saltzberg, Neale, Stone, and Rachmiel found that those who display high levels of selffocus have correspondingly increased levels of rumination about their distress, leading them to be more passive when dealing with their problems. Although rumination and self-focus share similar symptoms and often both appear in the behavior of depressed individuals, there are several key differences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Even though significant amounts of evidence point to a correlation between self-focus and the occurrence of depression, there is little evidence that self-focus directly influences specific aspects of depression such as its duration (Ingram, 1990; Musson & Alloy, 1988). Perhaps more importantly, rumination is seen as a conscious response of an individual attempting to cope with depression, while self-focus is a more general predilection to self-analyze after any significant event, negative or positive (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). The propensity to self-focus often coincides with an increased risk of depression, suggesting that it stems from an individual’s innate character traits, rather than a conscious plan of action. While rumination is understood to be a conscious behavioral coping response to depression and thus more likely to be influential in determining the course of a depressive episode (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), self-focus is considered an inherent characteristic, rendering it less impactful on depression.

Rumination

Susan Nolen-Hoeksema began the discussion of rumination in 1991, examining the phenomenon in the context of her proposed responses-styles theory, which argues that the manner in which individuals respond to their depression directly impacts the intensity and extent

of their symptoms. Those who actively seek to understand and resolve the source of their distress and anxiety may experience a depressive episode of only a few days, while those who react passively to their symptoms may unnecessarily prolong the duration of their depression (NolenHoeksema, 1991).

Nolen-Hoeksema discussed two important aspects of the rumination subfield. First, she discussed the previous studies that had established links between ruminative behavior and depression. In Morrow and Nolen-Hoeksema (1990), subjects experiencing depressed mood participated in a series of four types of activities that were deemed a combination of ruminative or distracting and passive or active. In doing so, they found that a distractive approach to dealing with depression would mitigate depressive symptoms more effectively compared to ruminative coping. Similarly, an active approach to dealing with depression would mitigate depressive symptoms more effectively than a passive approach because such activity distracts the individual from constantly focusing upon his/her symptoms.

Both results were strongly supported by other researchers, suggesting that passive and ruminative behavior exacerbates the depressive symptoms in an individual. The second study, Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson (1991), differed from the first study because, instead of assigning responses to depressed mood to subjects, it examined the natural fluctuations in mood of individuals for 30 consecutive days, along with their responses, in the hopes of understanding whether there are certain approaches to dealing with a depressed mood that can consistently influence, positively or negatively, the duration of their mood. Ultimately, the study found that individuals were extremely consistent in their style of coping with depression, whether it was ruminative or distractive, and that ruminative response styles resulted in significantly longer episodes of depression in a subject.

Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) touched upon the ability of rumination to prolong depressive episodes, proposing three possible mechanisms of action. First, because an individual’s past memories and the sentiments associated with those memories are inextricably linked with his/her perception and experience of the environment in the present, rumination can lead to a vicious cycle of depression where negative moods contribute to negative self-evaluations and lowered self esteem, which then generates even more negative feelings, and so on. Second, rumination can interfere with or potentially even replace instrumental behavior, which provides positive emotional support and a barrier against negative emotions to individuals. Instead of playing tennis with a friend or going out to watch a movie, which provide positive emotional reinforcement, individuals are plagued by thoughts of helplessness and lack of motivation. Finally, perhaps the most direct negative impact of rumination is that it prevents an individual from addressing the problems that are directly causing their depression. Instead of pinpointing issues and finding solutions to a predicament, rumination renders individuals demotivated or afraid of approaching their problems.

Second, Nolen-Hoeksema discussed the gender difference in depression, and studies that have shown rumination to be a causal factor of this difference. In particular, Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson (1991) found that women were significantly more likely to employ rumination as a coping mechanism for depression as compared to men; furthermore, women, on average, also battled longer and more intense depressive episodes, perhaps in part due to their propensity for excessive rumination. Interestingly, the study also notes that men who chronically employ a distractive coping mechanism may engage in more dangerous activities (e.g. excessive alcohol consumption) and be at higher risk of becoming emotionally unstable individuals (e.g. abusers) (Cooper, Russell, & George, 1988). Thus, even though men may experience less

clinically diagnosed depression, it is likely that they face other, often equally draining and distressing issues like alcoholism.

In 1994, Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, and Larson began examining an important question first raised by Nolen-Hoeksema (1991) in the field of rumination—how response styles can affect the duration of depression—noting that longitudinal studies of depression convey a statistically significant, positive relationship between the use of ruminative response and longer periods of depression (Nolen- Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993; Wood, Saltzberg, Neale, Stone, & Rachmiel, 1990).

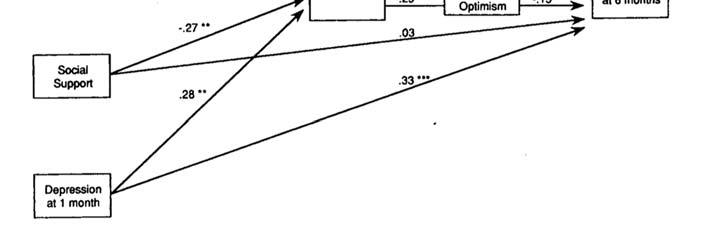

Figure 1 provides a succinct summary of many of the findings up to this point in the rumination literature. As Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson (1991) found, “Gender” was significantly correlated with “Rumination” (i.e. gender had noticeable impact on a subject’s tendency to ruminate) (Figure 1). Furthermore, “Additional Stressors” and “Social Support” formed opposite correlations with “Rumination,” a reasonable conclusion seeing that additional stressors would only exacerbate the inaction experienced by ruminating individuals while social support would allow for better problem solving for depressed individuals (Figure 1). Finally, “Depression at 1 month,” “Rumination,” and “Depression at 6 months” are all highly and significantly correlated, demonstrating that ruminating individuals likely experienced longer periods of depression that if they had not ruminated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A diagram documenting the positive and negative relationships between variables that impact depression (NolenHoeksema, Parker, and Larson, 1994). * p<.05; ** p<.01; *** p<.001.

Interestingly, the article also posed the question, “why do some people ruminate?,” which strikes at the heart of the gender differences in rumination and depression. With this question in mind, the subfield of rumination began to examine more closely the reasons why women ruminate more than men. Answering this question facilitated a better understanding of the gender differences in rumination. Nolen-Hoeksema, Grayson and Larson (1999) put forth two different reasons as to why women ruminate more than men. First, they argued that due to a woman’s lack of social influence, she is more likely to experience adverse emotional events and, unfortunately, also have less control over the means with which she could resolve her problems. Second, because women are constantly searching, through their often limited course of actions (as a result of societal stereotypes/norms), for a way to grasp and firmly control the root cause of their depressed mood, but feel unable or ineffective at doing so, they often remain firmly entrenched in rumination.

Ultimately, their findings are summarized in Figure 2, where factors influencing

rumination and depression were compared at two different times (T1, T2) to examine the interweaving influences of these factors upon each other over time. Not surprisingly, “Gender” appears to mediate a statistical increase in both “Rumination” and “Strain” (levels of stress/anxiety experienced by an individual) and a decrease in levels of “Mastery” (perceived control over one’s problems). Perhaps most importantly, all of these factors negatively reinforce each other. For example, “Rumination, T1” significantly increased likelihood for depression at T1, continued rumination at T2, and increased Strain at T2, while decreasing feelings of Mastery at T2. That these factors so powerfully modulated each other seemed to explain why the “Gender” factor may have a disproportionate influence on depression.

Figure 2. A diagram illustrating the relationship between gender, depression, rumination, mastery (perceived control over one’s problems), and strain (level of stress/anxiety experienced by an individual) (NolenHoeksema, Larson and Grayson, 1999).

However, in an ensuing study, Nolen-Hoeksema and Jackson (2001), found the relationship to be more complex, finding that the gender difference in rumination did not occur

because women were more anxious, depressed, or socially limited. Instead, they found that a combination of three factors contributed to a women’s greater tendency to ruminate. First, women are more likely to believe that negative emotions such as fear or anger are difficult to control, rendering them unwilling or afraid of responding and dealing with these emotions. Furthermore, women believe that they are more responsible for the emotional state of their relationships, meaning that they focus upon every nook and cranny of their relationship, constantly on edge. This then renders women more cognizant of their own emotional state, which soon becomes a barometer of all their relationships. The constant worrying about individual relationships translates into a constant examination of their own emotions. Finally, echoing the reasoning of Nolen-Hoeksema, Grayson and Larson (1999), the study proposes that women experience lower levels of mastery in their daily dealings, contributing to their vulnerability to ruminate.

Co-rumination

Just as researchers finally began to understand why individuals ruminate and why there is such a pronounced gender difference in rumination and depression, a new subfield of rumination emerged — co-rumination. At its heart, co-rumination shares many basic characteristics with rumination — a persistent, detrimental focus on the roots of one’s depression – only differing in that rumination is a solitary process while co-rumination is a social process. In 2002, Amanda Rose first discussed the novel construct of co-rumination, acknowledging the uniqueness of the phenomena, as it combined two seemingly different fields together, friendship and coping. Indeed, communication with others about the reasons for one’s distress often creates closer, healthier relationships; however, such an outlet for discussion of negative daily events can also lead to prolonged depressive symptoms as well (Tompkins, 2011). An understanding of co-

rumination would mean a unique understanding of the complex interweaving of the coping and friendship fields (Tompkins, 2011).

Interestingly, co-rumination was the one of the first constructs to draw attention to the possibility that social relationships and friendship could act as both a protective and a risk factor for the development of emotional problems (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). In her first study of corumination, Rose (2002) used a 27-question survey (now a standard in the field) consisting of yes or no questions like “We talk about problems that my friend and I are having almost every time we see each other” and “When we talk about a problem that one of us has, we’ll talk about every part of the problem over and over,” to identify the presence of co-rumination in a relationship. From her survey, Rose (2002) found that co-rumination was associated with high-quality friendships but also higher rates of depression.

Such a trend closely mirrors common observations of the gender difference between women and men in their relationships. Indeed, the construct was created, in part, to help understand why women form closer friendships than men, which should, in theory, better protect them from emotional struggles, yet these friendships fail to shield women from distress, anxiety, and depression (Bukowski, Hoza, and Boivin, 1994; Bukowski, Newcomb, & Hartup, 1996; Rose et al., 2008; Tompkins et al., 2011).

Rose et al. (2008) expounded upon the findings made in Rose (2002) by conducting a longitudinal study of co-ruminating adolescents to better understand the cause and effect of the onset of co-rumination. Rose et al. (2008) made an interesting observation in their study, noting that previous studies of co-rumination had presumed that co-rumination was a causal factor leading to closer-knit friendships and increased rates of depression — an assumption that may not always be true. They explained that co-rumination may arise precisely in a social

environment where friends are responsive to conversations about stressful life events. For example, youth who have higher quality friendships have significantly higher rates of corumination, an interesting trend that may partially explain gender differences in the rate of corumination (Rose et al., 2008). Thus, it seems that there may be a circular feedback loop rather than a linear relationship between close friendships, depression, and co-rumination.

Unfortunately, little is known about the nature of coruminative conversations, as the first and only observational study of coruminative friendships was done in 2014, with previous studies all being done on a self-report basis (Rose et al., 2014). Interestingly, they found that friends who coruminate with each other, despite their supportive attitudes, engage in more problem talk, possibly explaining the discrepancy between close friendships and increased depressive symptoms. These results support Stone et al., 2011, who found that co-rumination statistically increased the chance for an individual to be depressed and likely serves as one of the driving factors bringing about the gender differences beginning in adolescence. Interestingly, Rose et al. (2007) and Star and Davila (2009), also found that co-rumination occurs in both genders, but female co-rumination contributes more often to depressive behavior, a trend that appears independent of their higher rates of rumination. Because females form closer friendships, they are more likely to open up about and rehash their problems with their friends, contributing to their depressive symptoms.

At first, co-rumination appeared to affect depression through its mediation of the internalization of negative emotional influences like a stressful life event (Rose 2008; Hankin et al., 2007). In fact, Schwartz-Mette et al. (2012) report that co-rumination may actually spread the “act of co-rumination” like an infectious or contagious disease, whereby interactions with anxious friends may actually drive individuals to develop their own worries, much like how

youth often mimick the behavior of others, whether detrimentally or beneficially. However, the recent findings of Stone & Gibb et al. (2015) complicate co-rumination’s perceived mechanism of action, as co-rumination seems to influence depression by increasing an individual’s tendency to ruminate alone. They found that statistical links between co-rumination-rumination and rumination-depression were significant, but the link between co-rumination-depression was not. Co-rumination, at its heart, is simply a social manifestation of rumination.

Social Media and Future work

The advent of social media has completely changed the nature of communication, and, in turn, the ability for an individual to coruminate. In fact, over 70% of adolescents who use the Internet use some form of social media to communicate with their friends and one in three teens send at least 100 text messages a day (Lenhart, Purcell, et al., 2010). Little has been done in the field to study the nature of social networking, yet it is extremely important do so, as Davila et al. (2012) finds that it is the quality and type of friendships developed through each social network that influence depressive symptoms rather than the duration individuals spend on social networking sites. The social media revolution has resulted in more avenues for communication, but the constantly changing social media landscape, from MySpace to Facebook, instant messaging to Twitter, has made it extremely important for researchers to understand the nature of online communication itself in order to grasp the changing nature of online friendships—the means by which individuals coruminate.

There are three important theories regarding computer-mediated communication that suggest an impact on friendships and the occurrence of co-rumination across the Internet.

1. Culnan and Markus, 1987: The Cues-Filtered-Out theory suggests that an individual’s ability to establish interpersonal relationships through computer-mediated

communication is diminished because the nature of online communication contains fewer nonverbal and contextual clues (e.g. eye contact, facial expressions, etc.) for those in conversation.

2. Walther, 1992; Walther, 1995; Sprecher, 2014: The Social Information Processing theory states that those who use computer-mediated communication can adapt to the lack of contextual and nonverbal clues after an extended period of using such means of communication. Essentially, they can substitute online cues for the nonverbal clues in a relationship.

3. Walther, 1996: The Hyperpersonal theory posits that computer-mediated communication can feel even more personal than face-to-face communication because people are given the freedom in choosing how and when to reply, allowing them to present themselves in the best light. Furthermore, possible negative social cues are also filtered out through online communication, leading individuals to idealize each other in their relationships. Determining the validity of these theories will be of the utmost importance to the study of corumination, as the nature of co-rumination depends upon the type and proximity of the relationship between two individuals—the closer the friendship, the more often co-rumination occurs.

More recent studies on the relationship between social media and depression have finally begun to elucidate the nature of online communication. Van den Eijnden et al. (2008) began by characterizing the relationship between Instant Messaging, one of the first and most common means of social media communication (Gross, 2004; Valkenburg & Peter, 2007), and depression, finding a significant positive relationship. Furthermore, his findings supported Walther’s (1996) Hyperpersonal theory of computer-mediated communication, as he found that those who used

Instant Messaging were significantly more likely to develop positive images of their friends and continue to use the service. These results correspond well with the findings about co-rumination of Rose et al. (2008) as well, as the closer relationships developed via Instant Messaging likely allowed for more co-rumination to occur, leading to the more pronounced depressive symptoms. Ultimately, the reality of online social media communication lies on a spectrum between the proposed Social Information Processing Theory and the Hyperpersonal Theory. The fact is that although nonverbal cues in face-to-face communication may not be present during online conversations, there are so many different ways of communicating through social media than in person. For example, adolescents can take a few “snaps” for their friends, sharing small tidbits of their day with their friends, join a large group chat to continue socializing, and then video chat other friends. Thus, the lack of cues is made up for through the sheer number of different ways teens can present themselves online.

With this understanding of online social media communications, co-rumination now appears to be an important risk factor for teens susceptible to depression. Indeed, the growing rate of adolescent depression has coincided remarkably closely with the advent of social media communication and the hyperpersonal connections being made online nowadays seem to be facilitating more coruminative behavior and increasing rates of depression in adolescents (Kraut et al., 1998; Best et al., 2014).

The burgeoning field of co-rumination lies at the intersection between social media and the nature of online friendships, a critical actor in the constantly changing narrative of depression. However, despite the clear association between depression and social media, there is still much to be understood (Kraut et al., 1998; Best et al., 2014). Thus, the question arises: How

can researchers best understand the influence of online social media interactions on corumination?

First, researchers must better grasp the quality of online communication itself, fully understanding the means by which a physical barrier to communication alters the nature of friendships. This paper proposes that prior, circumstantial evidence supports theories that posit closer online relationships, but more directed studies have yet to tackle these questions (Walther 1996; Best et al., 2014). Then, the challenge becomes understanding each individual social network that teens are using; although it may be constructive in the short-term to understand how aspects of Facebook can impact adolescent friendships, rumination, and depression, a new social media outlet like Snapchat may present a uniquely different and unpredictable environment for researchers that must be studied on its own. Only by understanding social networking on a macro and micro level—how individuals interact with their friends online and on specific social media sites—can researchers begin to understand its interaction with co-rumination and depression.

References

Ainsworth, P. (2000). Understanding depression. Retrieved from ebrary database.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Major depressive episode. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., pp. 320-327). Washington, DC, US: American Psychiatric Assocation.

Beck, A. (2002). Clinical advances in cognitive psychotherapy: Theory and application (R. L. Leahy & E. T. Dowd, Eds.). New York, NY: Springer.

Best, P., Manktelow, R., & Taylor, B. (2014). Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review, 41, 27-36.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(3), 471-484.

Bukowski, W. M., Newcomb, A. F., & Hartup, W. W. (1996). The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, Russell, & George. (1988). Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 218-230.

Culnan, & Markus. (1987). Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Davila, J., Hershenberg, R., Feinstein, B. A., Gorman, K., Bhatia, V., & Starr, L. R. (2012). Frequency and quality of social networking among young adults: Associations with

depressive symptoms, rumination, and corumination. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(2), 72-86.

Depression. (2012, October). Retrieved July 30, 2014, from World Health Organization website:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

Essau et al. (2010). Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 127(0), 185-190.

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013).

Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism [PDF]. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161-170.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0033111

Fournier et al. (2010). Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: A patient-level metaanalysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(1), 47-53.

Garland. (2004). Facing the evidence: Antidepressant treatment in children and adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 170(4), 489-491.

Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1986). Persistent high self-focus after failure and low selffocus after success: The depressive self-focusing style. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 1039-1044.

Greenberg, J., & Smith, T. W. (1981). Depression and self-focused attention. Motivation and Emotion, 5(4), 323-331.

Gross, E. F. (2004). Adolescent Internet use: What we expect, what teens report. Applied Developmental Psychology, 25, 633-649.

Hankin, B. L. (2006). Adolescent depression: Description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy and Behavior, 8, 102-114.

Hankin, B. L., Mermelstein, R., & Roesch, L. (2007). Sex Differences in Adolescent Depression: Stress Exposure and Reactivity Models. Child Development, 78(1), 279-295.

Ingram. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical disorders: Review and conceptual model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 156-176.

Jose, P. E., & Brown, I. (2008). When does the gender difference in rumination begin? Gender and age differences in the use of rumination by adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 180-192.

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998).

Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017-1031.

Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., & Zickhuhr, K. (2010, February 3). Social media & mobile internet use among teens and young adults. Retrieved from Pew Research Center website: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/oldmedia/Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Social_Media_and_Young_Adults_Report_Final_with_to plines.pdf

Lyubomirsky, S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1993). Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2).

Morrow, & Nolen-Hoeksema. (1990). Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(3), 519-527.

Musson, & Alloy. (1988). Depression and self-directed attention. Cognitive Processes in Depression, 193-220.

Nemeroff. (2009). The role of serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression: As important as ever. Clinical Chemistry, 55(8), 1578-1579.

Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson. (1991). The effects of response styles on the duration of depressed mood: A field study. Unpublished manuscript, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92-104.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569-582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(5), 173-176.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Aldao, A. (2011). Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 704-708.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Jackson, B. (2001). Mediators of the gender difference in rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 37-47.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Larson, J., & Grayson, C. (1999). Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 1061-1072.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400-424.

Okdie, B. M., Guadagno, R. E., Bernieri, F. J., Geers, A. L., & Mclarney-Vesotski, A. R. (2011).

Getting to know you: Face-to-face versus online interactions. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 153-159.

Owens, & Nemeroff. (1994). Role of serotonin in the pathophysiology of depression: focus on the serotonin transporter. Clinical Chemistry, 20(2), 288-295.

Pierce, T. (2009). Social anxiety and technology: Face-to-face communication versus technological communication among teens. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 13671372.

Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (1985). Depression and preference for self-focusing stimuli after success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(4), 10661075.

Pyszczynski, T., Hamilton, J. C., Herring, F. H., & Greenberg, J. (1989). Depression, selffocused attention, and the negative memory bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(2), 351-357.

Pyszczynski, T., Holt, K., & Greenberg, J. (1987). Depression, self-focused attention, and expectancies for positive and negative future life events for self and others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 994-1001.

Rehm. (1977). A self-control model of depression. Behavior Therapy, 8, 220-240.

Reinherz et al. (1993). Psychosocial risks for major depression in late adolescence: A longitudinal community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(6), 1155-1163.

Rose, A. J. (2002). Co-rumination in the friendships of girls and boys. Child Development, 73(6), 1830-1843.

Rose, A. J., Carlson, W., & Waller, E. M. (2007). Prospective associations of co-rumination with friendship and emotional adjustment: Considering the socioemotional trade-offs of corumination. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 1019-1031.

Rose, A. J., Glick, G. C., Schwartz-Mette, R. A., Smith, R. L., & Luebbe, A. M. (2014). An observational study of co-rumination in adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology, 50(9), 2199-2099.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98-131.

Saffrey, C., & Ehrenberg, M. (2007). When thinking hurts: Attachment, rumination, and postrelationship adjustment. Personal Relationships, 14(3), 351-368.

Schwartz-Mette, R. A., & Rose, A. J. (2012). Co-rumination mediates montagion of internalizing symptoms within youths’ friendships. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1355-1365.

Shapero et al. (2014). Stressful life events and depression symptoms: The effect of childhood emotional abuse on stress reactivity. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(3), 209-223.

Sprecher, S. (2014). Initial interactions online-text, online-audio, online-video, or face-to-face: Effects of modality on liking, closeness, and other interpersonal outcomes [PDF]. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 190-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.029

Sprecher, S. (2014). Initial interactions online-text, online-audio, online-video, or face-to-face: Effects of modality on liking, closeness, and other interpersonal outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 190-197.

Starr, L. R., & Davila, J. (2009). Clarifying co-rumination: Associations with internalizing symptoms and romantic involvement among adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 32(1), 19-37.

Steingard et al. (2002). Smaller frontal lobe white matter volumes in depressed adolescents. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 52(5), 413-417.

Stone, L. B., & Gibb, B. E. (2015). Brief report: Preliminary evidence that co-rumination fosters adolescents' depression risk by increasing rumination. Journal of Adolescence, 38, 1-4.

Stone, L. B., Hankin, B. L., Gibb, B. E., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2011). Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(3), 752-757.

Stone, L. B., Uhrlass, D. J., & Gibb, B. E. (2010). Co-rumination and lifetime history of depressive disorders in dhildren. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(4), 597-602.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Greenfield, P. (2008). Communicating online: Adolescent relationships and the media. The Future of Children, 18(1), 1-27.

Tompkins, T. L., Hockett, A. R., Abraibesh, N., & Witt, J. L. (2011, January 1). A closer look at co-rumination: Gender, coping, peer functioning and internalizing/externalizing problems. Retrieved March 12, 2015, from Linfield College website: http://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=psycfac_p ubs

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2007). Online communication and adolescent well-being: Testing the stimulation versus the displacement hypothesis. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communications, 12(4), 1169-1182.

Van den Eijnden, R. J., Meerkerk, G. J., Vermulst, A. A., Spijkerman, R., & Engels, R. C. (2008). Online communication, compulsive Internet use, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 655-665.

Walter, J. B. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction a relational perspective. Sage Publications, 19(1), 52-90.

Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational aspects of computer-mediated communication: Experimental observations over time [PDF]. Organization Science, 6(2), 186-203. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2635121

Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational aspects of computer-mediated communication: Experimental observations over time. Organization Science, 6(2), 186-203.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer-mediated communication impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23(1), 3-43.

Walther, J. B. (2006). Selective self-presentation in computer-mediated communication: Hyperpersonal dimensions of technology, language, and cognition [PDF]. Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 2538-2557.

Westly, E. (2010). Different shades of blue. Scientific American Mind, 21(2), 30-37.

Wood, J. V., Saltzberg, J. A., Neale, J. M., Stone, A. A., & Rachmiel, T. B. (1990). Self-focused attention, coping responses, and distressed mood in everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1027-1036.

Zee et al. (2013). Circadian rhythm abnormalities. Continuum, 19(1), 132-147.