SUPERLATIVE SENIORs

FM CHAIRS

Maliya V. Ellis ’23-’24

Sophia S. Liang ’23

EDITORS-AT-LARGE

Josie F. Abugov ’22-’23

Saima S. Iqbal ’23

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Mila G. Barry ’25

Sarah W. Faber ’24

Io Y. Gilman ’25

Michal Goldstein ’25

Tess C. Kelley ’23

Amber H. Levis ’25

Akila V. Muthukumar ’23

Kaitlyn Tsai ’25

Benjy Wall-Feng ’25

Harrison R. T. Ward ’23

Maya M. F. Wilson ’24

Meimei Xu ’24

Dina R. Zeldin ’25

FM DESIGN EXECS

Michael Hu ’25

Sophia Salamanca ’25

Sophia C. Scott ’25

FM PHOTO EXEC

Joey Huang ’24

PRESIDENT

Raquel Coronell Uribe ’22-’23

MANAGING EDITOR

Jasper G. Goodman ’23

BUSINESS MANAGER

Amy X. Zhou ’23

COVER DESIGN

Sophia Salamanca ’25

Over the past year, we’ve received lots of fan mail from you all. FM has been called “stupendous,” “paradigm-shifting,” “an absolute delight to read,” etcetera, etcetera. So the bar for this end-of-year issue was high — but our writers have surpassed it once again. Indeed, if we can toot our own horn a bit, this glossy is a superlative one.

And so too are the seniors we profiled in this issue. After trying out many iterations of senior features in the past — Most Interesting, Randomly Generated, and even (regrettably) Hottest — FM is returning to a classic this year: senior superlatives. We asked the Class of 2023 to nominate 15 of their peers for our superlative categories, including Best Dressed, Class Clown, and Most Likely to be President. While each of these seniors has a unique speciality (well, except Most Well-Rounded), all of them were passionate, pretty darn humble, and a pleasure to get to know.

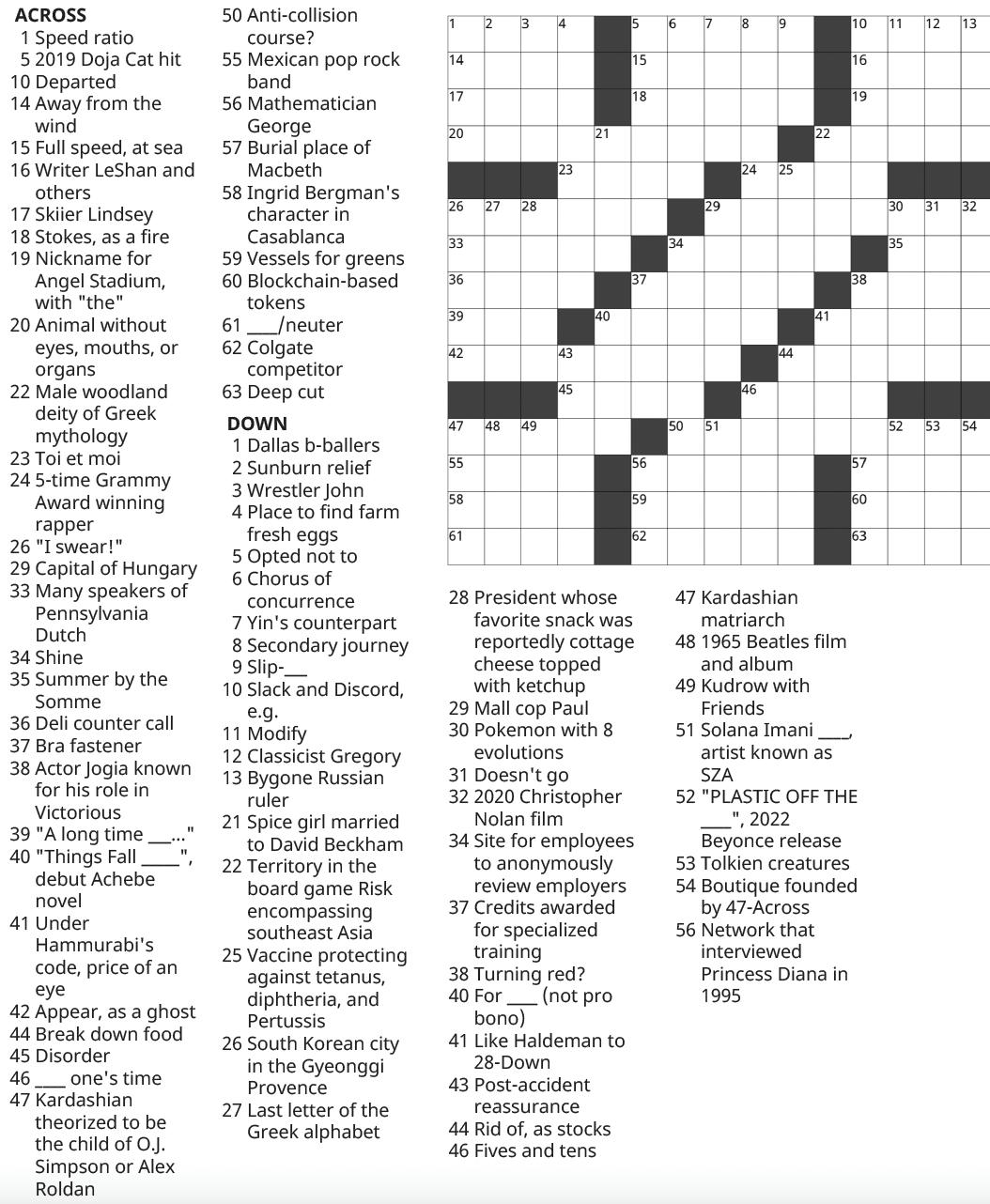

Even as we highlight these very accomplished seniors, we still remember what it was like to be a confused freshman, overwhelmed by all the Harvard jargon. How do I look for a “gem”? Is a “comp” based on completion or competition? Why can’t we just call them majors like a normal school? Luckily, HD, MMN, and KT spent the semester compiling an (un)official dictionary of Harvard lingo, tracing the origins and evolution of 15 words and phrases with particular significance. The stories behind these words shed light on the history and culture of our campus, especially the role we students have had in shaping it — from the freshmen arguing whether it’s “the ’Berg” or just “’Berg” to the seniors mourning the loss of shopping week.

This is the longest glossy we’ve ever published, the latest we’ve ever stayed up to publish one, and possibly the shiniest to date (you can be the judge of that one). It is also our last. We’ll miss the Monday nights spent debating pitches and lounging on beanbags, the Tuesday evening maestros derailed by Photoshop rabbit holes, the weekend afternoons filled with frenzied editing and Post-its and laughter. Leading this magazine has been the best experience we could’ve asked for.

As sad as we are to depart, we could not be more excited to bequeath FM to the toughest, wisest, kindest people we know: AHL and IYG. Going forward, please address your adoring letters to them instead — this next chapter of FM is going to be the best-est.

Yours in retirement, SSL & MVE

Coming to college — especially to a place like Harvard — can be a difficult transition. The lectures are faster and the essays are longer. Many of us must learn how to live with roommates for the first time. Adjusting to HUDS is a feat of its own.

But there’s also that quintessential freshman feeling of not having a clue what everyone around you is talking about. Who’s getting punched, and are they okay? Who spelled “LGBTQ” wrong on this office door? What’s a “comp,” and why am I being yelled at to do it outside of Annenberg?

Strange acronyms litter our vocabulary. When speaking with family or friends back home, we spend an extra 10 minutes translating “Harvard speak” into regular terms while telling a simple story. So we set off to compile an (un)official Harvard dictionary for the uninitiated.

We were also determined to answer an age-old question: Why do Harvard students talk like that?

To do so, we distributed a survey to the entire College, asking current students about their linguistic habits — with questions like “What do you think ‘comp’ is short for?” and “How many hours of work should a ‘gem’ require?” — and received 400 responses, unadjusted for possible selection bias. We also combed through old Crimson articles, personal correspondence, and archival records.

It became increasingly clear that the answer would not be simple. As with any other language, each Harvard term or phrase has a complex backstory that reveals something about campus culture.

Fiona McPherson, a senior editor for the New Word team at the Oxford English Dictionary, believes that words are an ever-evolving tool which merely reflect the ever-evolving people

who use them. “Language will change, and the words which will come into use — also the words which will die out of usage in some way — has often got a lot to say about the state of the world,” she says. “What’s happening in the world, and also what our views are, and what is preoccupying us.”

Language shapes our reality and shapes us. So whether you still insist on the word “major,” are a die-hard “concentration” user, or tend to match the vibe of your audience, these 15 Harvard words tell an important story about who we are, who we choose to become, and where we’re going.

In the standard first-day-of-class introduction that includes your name, class year, and field of study, it’s become commonplace for students to add their personal pronouns. But our survey respondents reported phrasing that introduction in different ways, from “My pronouns are ___” to “I use ___” to “I go by ___.” This linguistic variation would not in itself be a problem, if our peers at other schools did not find some variants particularly strange — outrageous, even.

“Today i learned people at Harvard take pronouns,” a Yale student tweeted in March. “never before in my life have I heard the phrase ‘i take the she series’. instant psychic damage.”

In the Twitter discourse that followed, students from other schools mocked our habit of saying we “take” pronouns (“personally I borrow my pronouns,” one user wrote) as well as our use of pronoun “series”

(“HUHHHHH!!?!?!? this is crazy??? series??” wrote another).

These syntactic quirks certainly cause confusion, but Harvard does not appear to be alone. While our survey respondents were far less likely to have heard the “I take the ___ series” phrasing before coming to college (compared to more popular variants like “My pronouns are ___”), almost a fifth of students reported they had heard it before.

Part of the variation may arise from the phenomenon’s recent institutionalization. Harvard only started allowing students to indicate their pronouns on their student records in 2015. No single standardized way of introducing pronouns exists yet, and certain formulations may have unintended connotations — making “series” the norm, for example, may exclude people who use multiple pronouns, like she/they.

We do have proof, however, that we aren’t as crazy as Yale students might have us believe. A Tufts University Office of Equal Opportunity website mentions pronoun series, and in a 2015 Oberlin College newspaper op-ed, one student defended her use of “I take she/her” by distinguishing it from “I prefer she/her”: “It’s not a matter of what I would rather.”

We’ve all been there: a passing conversation with someone in that gray area between acquaintance and friend. After the usual pleasantries, an awkward silence looms. Confronted with this impending horror, you blurt “let’s get lunch sometime!” or “we should totally grab a meal soon.” The other person agrees, equally relieved, and the conversation ends. Phew.

In a 2010 FM article, one student called the trite invitation “a classic

evasion tactic.” Without seeming harsh or unfriendly, “you walk away commitment-free.”

The cheeky duplicity of the phrase now serves as a joke for editorials, blog posts, and even a flowchart in The Crimson’s blog titled “Will You Ever Actually ‘Grab a Meal Sometime’?”

In 2020, one disgruntled freshman lamented how “let’s get lunch” had become “a nicety at best, and a symbol of everything wrong with social life on campus at worst.” In her view, many hyper-ambitious students develop a “fear of free time” that makes it difficult to have spontaneous social interactions. They want to keep up the appearance of friendliness without having to give up a precious slot on their Google Calendar.

As a result, both parties walk away from the lunch invitation unsure of its sincerity. On our survey, when asked to rate how likely they were to actually get lunch with someone after using the phrase, students were almost equally as likely to answer “we will never have lunch together” as “we will definitely have lunch together.” A plurality (34

percent) chose the middle option, completely ambivalent.

So the next time someone tells you “let’s get lunch,” a more statistically accurate response than the typical enthusiastic agreement would be “maybe, maybe not.”

The House system, a beloved staple in residential life at the College, was created in the early 1930s by former University President Abbott Lawrence Lowell, Class of 1877. Before the construction of the nine River houses, three Radcliffe Quadrangle houses, and the Dudley Co-Op, housing at Harvard was limited to Yard dormitories in shoddy condition.

A 1995 housing pamphlet describes how in the 1800s, “Student rooms were often spartan affairs, and two students sometimes shared

a single bed.” Harvard economist Seymour E. Harris, Class of 1920, reported that “in 1856, Henry Adams complained of winds howling about him in his college room. No heat attainable could prevent the water in his pitcher from freezing inches deep in cold weather.”

As a result, in 1876, private developers began cashing in on wealthy students by constructing opulent apartment buildings that were referred to as “Gold Coast” dormitories around Mount Auburn St. This inevitably led to a sort of “freshman flight” as wealthy students were able to move off-campus, while their poorer classmates remained in the Yard.

Lowell put a stop to this by requiring all freshmen to live on campus, which ultimately led Gold Coast dorm owners to sell their property to the University. Lowell also envisioned a collegiate experience that centered both living and learning for all three upper class years, modeled off the dormitory systems at Oxford and Cambridge University. Writing in 1958, he explained, “The Houses are designed to help substitute for the schoolboy attitude of mind — which has dominated so much the American college — a type of life more mature and, when understood, more enjoyable.”

He made this dream a reality with the construction of Dunster and Lowell Houses in 1930, then Eliot in 1931. The original Gold Coast dorms became Apley Court, Adams House, and surrounding apartments.

But the fact still remains that we don’t move into dorms or halls or even residential colleges in sophomore year, but a house. We must explain to our family and friends that we are not actually signing a lease on a rental house with our roommates — merely living in non-freshman dormitories.

Calling upperclassmen dorms “houses” most likely hails from the word’s original usage to refer to Harvard College as a whole. According to historian Samuel Elliot Morison in his 1936 book“Three Centuries of Harvard,” paying tuition made one a “member of the House, as Harvard College was familiarly called.”

Just think: Back in the 19th century, the Harvard intro could’ve included identifying your year at “the House,” not the College.

For Harvard freshmen in their spring semesters, there is no single word that provokes greater fear than “Quad.” Getting “quadded” — that is, placed in Cabot, Currier, or Pfoho on Housing Day — dooms you to a life of mile-long winter walks to class, hours spent decoding the shuttle schedules, and, worst of all, pitying smirks from your riverfront peers. (Though rest assured that many students also enjoy the Quad’s close-knit community and more spacious dorms). For better or for worse, the distance between the Quad Houses and their River siblings is stark, and it’s no accident.

Before it was the Quad, it was a different school entirely: Radcliffe College. Students in the small women’s college, founded in 1879, lived in dormitories around a grassy quadrangle. Radcliffe gradually merged with Harvard over the course of decades. Starting in 1943, Radcliffe students could take classes at Harvard. In 1972, amid the growing popularity of co-ed schools like Yale and Stanford, Radcliffe students began living at Harvard (and vice versa).

Even after the Quad dorms were incorporated into Harvard’s House system, the Radcliffe name lingered for a few more years. Rather than getting quadded, students (including

some freshmen) lived at “The ’Cliffe.” These “’Cliffe dwellers” lamented the distance from their peers and their quieter social life. According to a 1975 Crimson article, Cabot (then called South House) was more likely to serve “milk and cookies,” while the Yard threw “massive beer parties.”

But as the differences between Harvard and the Radcliffe Quad became less pronounced, Harvard students began to pronounce the “Radcliffe” less than “the Quad.”

Although some appreciated the serene walks to class and the luxurious Hilles Library (which became the Student Organization Center at Hilles in 2006), when freshmen ranked their housing preferences, Quad houses overwhelmingly filled the bottom slots. The first classes of quadded men, especially the athletes who had to travel across the river for practice, complained so vehemently that Harvard began offering shuttle buses to the Yard and the River houses in 1973. Over the course of the ’70s, fears about being assigned to live in the Quad molded language itself.

“Anything is better than being quadded,” one freshman told a Crimson reporter in the spring of 1980. It was the first time “quad”

was used as a verb in The Crimson. At the time, the slang term must have been relatively new. Alumni we interviewed from the ’70s, including as late as the Class of ’78, had never heard “quad” used as a verb.

The change wasn’t merely symbolic. In 1974, as Radcliffe combined its athletics program with Harvard’s, all the women’s sports teams except crew chose to take on the Harvard name and leave behind Radcliffe. At the same time, Radcliffe’s student organizations and administrative offices were merging with Harvard’s.

Jane R. Borthwick ’76 initially saw it as a victory when the Radcliffe admissions office merged with Harvard’s. But later, she found it sad. As Harvard was finally opening its doors to women, its name was overshadowing the rich history and traditions they’d created for themselves. Radcliffe College was disappearing. As Borthwick wrote in an email, “with no students, how could it continue to be called a college?”

Questions about the relationship between the Quad and the rest of the College remain to this day. Last year, when Harvard began using “Harvard Radcliffe Institute” as shorthand for

the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, alumni protested that inserting the Harvard name would diminish the Radcliffe legacy. For many alumni, preserving the history of Radcliffe requires maintaining some distance — while students trekking back home to the Quad wish it were just a little bit closer.

Up until the early 1900s, Harvard students only needed to take any 16 classes in order to graduate. Former English professor Barrett Wendell, Class of 1877, who wanted to bring greater order to the free electives system, formed a History and Literature program in 1906 that provided a structured plan of required courses and tutorials. Three years later, President Lowell, who believed the elective system encouraged students to view academics as “an inconvenient ritual,” decided that students need “a department of major concentration.” And thus the term “concentration” was born. Students had to take at least six courses in a single department, only two of which were allowed to be introductory courses.

Brown adopted concentrations around the same time Harvard did, for the 1910-11 school year. Shortly after, two schools followed: Princeton in 1923 and Columbia in 1928. The concept of field specialization, however, wasn’t new; the University of Virginia had begun offering students a set of programs to choose from, seven in total, in 1825.

After the Civil War, specialization at American institutions rapidly developed. In its 1877-78 course

catalog, Johns Hopkins University coined the terms “major” and “minor,” which became the terms most other universities adopted.

Harvard, however, stuck with “concentration,” Lowell’s original term. The University also invented a term for its “minor” analogue: secondary.

Secondaries came around at Harvard in 2006 — much later than minors did at other schools — as it became evident that students “were going through all sorts of contortions” in an effort to specialize in multiple fields, former Harvard College Dean Benedict H. Gross ’71 wrote in an email.

Still, some faculty were wary of the proposal. In 2006, Government professor and former department chair Nancy L. Rosenblum called the vote a “shot in the dark.” “I can’t tell whether this is an entrepreneurial effort by the faculty or opening a Pandora’s box,” she said in an interview with The Crimson at the time.

But after a three-and-a-half-year curricular review, members of the Committee on Educational Policy decided that they needed to introduce minors, but they needed a different name. “How could Harvard have minors when we didn’t have majors?” Gross wrote.

Eventually, English professor Marjorie Garber came up with the term “secondary fields,” according to Gross. Garber herself says she does not remember suggesting the term, though she does remember the motivation behind it.

“There was no implication that ‘second’ meant less important; to the contrary, we wanted to allow students to highlight this additional focus of their academic work, should they elect to do so,” Garber wrote in an email.

Today, Harvard offers 50

concentrations and 49 secondaries. But which fields have been able to earn concentration status has historically been fraught. Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality, for example, first arose as the Committee on Women’s Studies in 1978 and spent its first five years as “a loose confederation of cross-listed classes, with no power to confer degrees,” according to a 2011 FM article.

When former comparative literature professor Susan R. Suleiman became head of the Committee on Women’s Studies in 1983, she sought to change this. From ensuring they had a listing in the phonebook to writing individual letters to every member of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Suleiman and her colleagues fought to establish Women’s Studies as a full concentration — and finally succeeded in 1987. In 2003, recognizing the importance of expanding beyond simply Women’s Studies, the Committee took on its modern name.

Today, despite its increasing popularity, WGS still struggles to gain departmental recognition. Currently, WGS falls under Standing Committees of the FAS, meaning that it is a nondepartmental degree program. Unlike departments, these committees are staffed by professors and head tutors who run tutorials, set concentration requirements, and occasionally oversee exams and theses. Often, these faculty members are jointly appointed to other programs; it was only in 2017, for example, that WGS hired its first fulltime faculty member. Becoming a department would confer on WGS stronger administrative backing and greater recognition among students and administrators.

Similarly, students have pushed for decades to establish an Ethnic Studies department at Harvard. Despite

a recent FAS cluster hire of ethnic studies scholars, the school still does not have a concentration or academic department dedicated to the field. The Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights — an attempt to address calls in the 2000s for an Ethnic Studies program — only offers secondaries.

Beyond simply being analogues for their more popular counterparts of “major” and “minor,” then, “concentration” and “secondary” also speak to questions about which fields the University values.

Michael Bronski, a writer and activist who has been involved in queer politics since 1969, says he had never heard anyone use “BGLTQ” before he came to Harvard as a lecturer. The acronym for Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Trans, Queer, and Questioning students is what Harvard uses in all its official capacities, such as the Office of BGLTQ Student Life.

Yet our survey respondents much prefer the more common acronym “LGTBQ.” Nobody indicated that they use BGLTQ unless referring to Harvard-specific entities. Even the Office of BGLTQ Student Life is often called the “QuOffice” — a portmanteau of “Queer Office.” Prior to this year, The Crimson’s own style guide called for “BGLTQ” in its articles.

On the whole, students expressed confusion or annoyance about Harvard’s use of the non-standard acronym. One respondent wrote, “it’s so dumb and I hate it.” Another wrote that BGLTQ is “really just a silly, fake word.”

Why, then, does Harvard insist on BGLTQ? Is it just another pretentious quirk of the university? Surprisingly, the answer has just as much to do with students as it does with Harvard’s

administrators.

Robyn Ochs, a speaker and activist who worked in Harvard’s administration for 26 years, says that when she first came to the college, “LGBTQ+ folks weren’t on the radar” of the administration — students, faculty, and staff had to force Harvard to start paying attention throughout the ’90s and early 2000s. The choice of BGLTQ, however, was by no means predetermined. By 2009, if not earlier, Quincy House had its own “LGBT” tutors.

One of the principal student organizations involved in queer activism during this time was the Bisexual, Gay, Lesbian, Transgender and Supporters’ Alliance, or BGLTSA. The name of the group was “an attempt to decenter gay men,” Ochs says, by putting the identities in alphabetical order. She recalls that it was not a common acronym at the time but rather “Harvard students making a statement.”

When at long last the Dean of the College formed a committee to begin institutionalizing support for queer undergraduates, “the administration followed the students,” as Ochs puts it. Inspired by the BGLTSA, the administration convened the BGLTQ working group in late 2010, which led to the 2012 founding of the Office of BGLTQ Student Life and its subsidiaries.

However unusual Harvard’s mixed-up letters may be, they are also a reminder of how the acronym itself, as well as the coalition it represents, is not set in stone. Bronski points to recent debates about appending I (for intersex) and A (for asexual) to the abbreviation. He also emphasizes the long history of “LGBT,” which came together one letter at a time over decades of debating and organizing.

At Harvard, everything “BGLTQ” largely came from the BGLTSA. Oddly

enough, as much as undergraduates today might see “BGLTQ” as “fake” and “silly,” the acronym is testament to the power of student-led activism.

What does the Q stand for in “Q Guide”?

“Huh … that’s a good question,” says one student we interviewed. “Questionnaire?” Other responses ranged from “quality” to “I have no idea.”

It’s a bit of a trick question. The Q Guide, in its current form, is an online database of course evaluations and comments from the last 15 years or so, collected and displayed by the Harvard College Institutional Research Office. But Harvard course evaluations date all the way back to 1925, when The Crimson began to publish its own compilation of course reviews known as the Confidential Guide of College Courses, or “The Confi.” In 1975, in an effort to formalize the evaluations, the Committee on Undergraduate Education began printing its own CUE guide. When Harvard added graduate course evaluations to the publication in 2006, the CUE no longer controlled the system, leading the administration to rename it the Q.

To students and faculty today, the Q Guide stands for much more than “question,” “quality,” or CUE.

Scores on the Q Guide — which assess student satisfaction, average workload, and professors’ performance — are a key factor in class selection for many undergraduates. A bad Q score can prompt professors to rework their entire curriculum, and a good one can bolster the career prospects of graduate teaching fellows.

But the true magic of the Q is the comments. On any given course’s evaluations, the anonymous comment section is fragmented and cacophonous — a “collaborative literary masterpiece,” as one student wrote in a 2020 Crimson op-ed. Masterpieces need not be consistent. In the fall 2019 Q report on CS50, students left comments ranging from “YOU NEED TO TAKE THIS COURSE” to “THIS IS A TERRIBLE COURSE, I HATE DAVID MALAN WITH MY ENTIRE SOUL.”

Equal parts utilitarian and chaotic, professor’s performance review and students’ performative reviews, the Q Guide defies easy answers. Who knew one letter could contain so much?

Much of the time we’re sifting through the Q Guide, we’re really just mining for gem classes. Low-stress diamonds in Harvard’s high-pressure rough, “gems” are the precious easy offerings that dot the course catalog. How easy? No clear definition exists, but 95 percent of surveyed students agreed that a gem should require less than four hours of work per week outside of class. Most went further, with 56 percent putting the standard at two hours per week or lower. Whatever the exact threshold, students at Harvard have always

tried to find light courses, though the terminology has changed. As far back as 1886, overworked undergraduates flocked to “snap courses” or “snaps” to balance out their schedules. In the second half of the 20th century, “gut” became the word of choice, indicative of relaxed assignments and easy grading that students could “eat up.”

Some guts became legends in their own right. A natural science Gen Ed in the ’60s earned the title “Rocks for Jocks,” recalled then-Dean of Freshmen Thomas A. Dingman ’67 in a 2013 Crimson article. More recently, one student in our survey noted that Stat 104 used to be dubbed “Frat 104.”

“Gem,” it turns out, is Harvardspecific and surprisingly recent. While “snap” and “gut” have become popular enough across higher education to earn their own dictionary entries, “gem” remains unheard-of outside the Harvard bubble. Perhaps that’s because the slang meaning of the word only emerged a dozen or so years ago, around 2010. The archetypal gem is Gregory Nagy’s Gen Ed on the Ancient Greek hero. The first recorded use of “gem” in the Q Guide came in this course’s 2011 reviews. In fact, “Heroes for Zeros,” as students used to call it, has been taught for so long (almost 50 years) that it was also once the archetypal gut. When asked in an interview last

month why he thinks his course has remained so popular, Nagy told FM, “I just find it has a universal appeal that withstands all the changes of cultures and upheavals of society.”

To students, though, there seems to be only one kind of change that a gem must withstand: any increase in its difficulty. This increase is usually the professor’s strategic attempt to dispel their soft reputation. In the late ’90s, the professor of “Rocks for Jocks” claimed he had changed the material so much that “anyone who thinks … it is an easy course would be in for a shock.”

In some cases, gems are victims of their own success. This year, a Gen Ed called “Sleep” became the subject of intense complaint. An October Crimson op-ed titled “Make Sleep a Gem Again” decried the addition of in-class quizzes and even a final exam to a class once known as “the gemmiest of gems.” In the writer’s view, the class has turned into “a hard, old rock.”

But accusations of sabotage are par for the course, even before the advent of “gem.” A 1990 article in The Crimson warned students that since Nagy “beefed up” the requirements for “Greek Hero,” “the one-time gut may never be the same.” Six years later, however, the class had not left its spot as the principal gut, according to The Crimson’s analysis of the 1996 Confi.

In the 2011 Q Guide, one disgruntled student grumbled that Greek Hero “had the reputation of being the ‘gem of gems’... not anymore.” However, that same year, two other classmates praised the course’s light workload in their reviews.

For all the false alarms, “Greek Hero” hasn’t stopped saving students’ schedules. When asked to list examples of gems in our survey, over 20 percent of responses included

Nagy’s class.

Part of the mythology of any gem, it seems, is that it has recently gotten harder (or will soon). Ask around about a notoriously gemmy Gen Ed, and you might find rumors swirling that professors will require more reading, replace a creative final project with an exam, or (gasp) start taking attendance. But don’t take every Q review as prophecy. A gem (or gut or snap) was always easier last year.

The origins of this dreaded and beloved term, short for “problem set,” are hard to pin down. Simple searches frequently tie it to MIT, which is unsurprising given that it is “the most common unit of homework assigned here,” according to an MIT student on the university’s admissions page.

At MIT, “pset” was first used in print in a 2002 edition of the student newspaper, the Tech, by academic frats offering help on — or breaks from — psets, and the popularity of the term increased with the tech boom. By 2008, the term seemed to have also trickled up to faculty, as indicated by an article from the MIT Faculty Newsletter regarding academic dishonesty on psets. The Crimson itself first used pset in a 2009 article publicizing events for students to attend.

The term isn’t just used at these two schools, however. According to The Crimson’s survey, 40 percent of students had heard “pset” prior to coming to Harvard, and several other universities — the University of California Berkeley, Stanford, Columbia, and Princeton, among others — use the term.

Less common, however, is the verb version of pset, i.e. psetting, which survey results indicated only 19 percent of respondents had heard

before coming to Harvard. First used in The Crimson in a 2013 op-ed, in which the author recalled a “wild night of psetting and reading in the Currier dining hall,” psetting stands for more than just the abbreviation of a longer term. It also represents the culture of collaboration and commiseration over STEM classes as students debate how many pset classes to take, gather for house pset nights in dining halls, and find pset buddies to work with.

While “Lamonster” today evokes the image of a messy-haired, baggyeyed student pulling an all-nighter in Lamont Library, the term originally referred to a part of the building itself: Lamont Cafe. Members of the Lamont Cafe Committee began brainstorming names for the eatery just before it opened in 2006: Labrontasaurus, Stacks N Snacks, Midnight Oil, The Larry Summers Memorial Cafe, and, of course, Lamonster. In the end, however, they went with the wittiest name of all: Lamont Library Cafe. With the establishment of the cafe came the Lamonsters as we know them now. Students had already begun frequenting the library at odd hours after it switched to a 24/5 schedule in the fall of 2005. “Now that Lamont has a café, we will never have to leave,” wrote a 2006 Crimson op-ed titled “We’ve Created a (La)Monster.” Indeed, during the 18-day reading and exam period of fall 2011, Lamont reported 36,989 unique visits. “Lamonster” quickly became a beloved term for the “bleary-eyed and smelly beast” that is a student pulling an all-nighter, as one 2011 Crimson article put it. This year, the library played up the term by hosting its first Lamonster Mash, a Halloween celebration involving crafts and

trick-or-treating. But for students, Lamonster will always refer to those cursed souls studying, eating, sleeping — and doing pretty much any other activity one can think of — in the library.

Despite the cutesy name, the Lamonster trend has an ugly side. “Leave it to Harvard students to make a student center out of a study space,” the 2006 op-ed wrote. “Lamont is not even efficient anymore, because its inhabitants are going insane.” Overworked and sleep-deprived, Lamonsters slowly lose contact with the outside world as they slog through assignment after assignment. As the author advises: “for your own sake, leave the place sometime.”

One does not simply join a student organization at Harvard. Each fall, the infamous “comp” process instills stress among the student body as overly-ambitious freshmen and upperclassmen alike vie for spots in the selective student organizations of their choice.

But membership requirements vary from club to club, ranging from written assignments to presentations to dinner socials. So what exactly does “comp” mean? Is it short for something? Is there a reason we use it instead of a more normal verb like “join”?

When asked to select all of the possible meanings for comp that they thought applied in our College-wide survey, students most frequently chose “competition,” with “completion” and “competency” not far behind. Two brave souls wrote in “compensation.”

It somewhat pains us to admit that the word finds its roots in the historically exclusive walls of our very own Harvard Crimson. An article from 1932 proudly declared the beginning of The Crimson’s annual “competition” to become a staff writer.

By 1944, The Crimson’s “competition” had been shortened to a “comp,” and it had become the widely adopted shorthand for other organizations with competitive processes to join. In an informal guide written for Black freshmen by the Afro-American Students Association in 1973, an entire section is devoted to “inside tips” for comping various clubs, such as The Crimson, the Independent, and WHRB.

Today, many clubs (including The Crimson) have abandoned competitive comps in favor of completion- or competency-based requirements. But regardless of what it stands for, “comp” represents a part of Harvard’s culture that is surely here to stay: figuring out how to do regular

college student things in the most extra way possible.

Arguably the most elusive word in the Harvard language, “punch” is the not-so-affectionate term used to describe the final club selection process that occurs each fall. Much like the actual process, the origin of the word punch is shrouded in mystery.

The term “final club” is less difficult to trace. Back in the 1800s, the social clubs at Harvard were largely divided by class year. Freshmen were first able to join the Institute of 1770 (the first social club at Harvard) or the Hasty Pudding Club, then a “waiting club” like the Fox or Owl during their upperclassmen years, until they were able to join their “final club” during senior year. Eventually, all 14 clubs on campus became known as “final clubs.”

The official first usage of “punch”

on the other hand, would likely be found in some internal documents — carefully tucked away in some final club’s archives that we would never get access to.

In the College-wide survey we conducted, we asked for help — even if you’d only heard an obscure myth from a friend of a friend. The responses were, of course, speculative. One respondent guessed it had something to do with a punch card for recording hours. Another thought it was about getting an actual ticket punched. A few people mentioned Lorde “punching The Love Club” in her 2013 song, and reasoned it was slang from the U.K. Some wondered if it had to do with new members getting physically punched as part of initiation.

After piecing together old Crimson articles, we discovered the real origins, less violent but just as zany. It was customary for a good party in the 1800s to serve punch, usually made with a lot of rum. A strange, mystical Crimson piece published in 1873 led us to believe that this eventually became slang for parties as a whole. In it, the author references a man telling “some tale of wild pranks after a punch, when the royal upper-classmen had been served from a huge bowl by trembling Freshmen.”

The pattern continues. In an article from 1874, another anonymous author references his roommate “[giving] a punch” in their dorm room the night before an exam and serving a drink

Shopping week — the first week of the semester during which students could “shop,” or sit in on, as many classes as they wished — was longheralded as “one of the small but important gems that make Harvard a unique University,” as one Crimson op-ed put it. But the tradition met its end this past spring after faculty voted to implement a previous-term registration system starting in spring 2024. While students today still lament this decision, shopping week is quickly becoming a quirk of the past. After the pandemic necessitated a shift to virtual “Course Preview Periods” for the last five semesters, the only students on campus who have ever experienced a real shopping week are the Class of 2023.

Shopping week was met with controversy from the start. The policy — and objections to it — first began when former University President Charles W. Eliot, Class of 1853, implemented a free elective system around the turn of the century that allowed students to choose which classes they wanted to take. In the early 1900s, the university tested a pre-registration system but terminated it by 1954 after recognizing its failures to streamline the course registration process.

In the fall of 2002, however, former Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences William C. Kirby began pushing for an early course selection system that would have required students to complete tentative schedules in the semester prior but would still allow them to shop. The motion set off another flurry of debate, with students and faculty alike arguing from either side.

Arguments from the two sides remained roughly the same for two

decades. Those against shopping week argued that the system made it difficult for instructors and teaching fellows to coordinate staffing and scheduling. “When professors don’t know how many teaching fellows they need, graduate students who count on those jobs can’t effectively structure their schedules, their course plans, or their finances,” wrote a 2022 Crimson opinion piece. “As undergraduate students, we must remember that this community includes not only our peers in the classroom, but also the graduate students and professors who teach us.”

Shopping week proponents responded that to alleviate pressure on teaching fellows, administrators should instead lower the number of sections graduate students must have in order to receive living expense support. Moreover, shopping week “offered Harvard undergraduates the rare opportunity to step, or at least peek, outside their comfort zones, to try out new academic endeavors without immediately having to assume any and all grade-related consequences,” a 2022 Crimson staff editorial argued.

In October 2002, Kirby confirmed his intention to implement preregistration beginning 2003, inciting waves of backlash from students and faculty that ultimately led him to back down from his plan. But the intensity of the debate weakened the foundations of shopping week, and the tradition saw a different fate by the end of the most recent dispute.

Last month, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences shared the official timeline for the transition to pre-registration: From Nov. 1 to Nov. 15, 2023, students will register for their spring 2024 classes, marking the official end of shopping week and the decades-long battle surrounding it — provided history doesn’t repeat itself.

“compounded of the most dissimilar and deadly ingredients.” Apparently, it also became a trend around the nineteenth century for the freshmen to “give a punch” to the sophomore class. According to “Three Centuries of Harvard,” “President Quincy warned the rowdy class about to graduate to abstain from punch and dancing, or they would lose their degrees.”

In short, whatever they were serving in the punch at Harvard back in the 1800s got people so drunk that they decided to call any certified rager a punch.

Naturally, final clubs were no exception. They began calling the prospective members they invited to these punch events, “punches.” Eventually, using “punch” to reference any crazy party on campus died out, and the term became specific to final clubs.

Still, nothing is stopping anyone else from brewing up a blackoutbound concoction, throwing a rager, and bringing back this time-honored Harvard tradition.

“Where do you go to school?” is a dreaded question for many Harvard students. Should you say “a school outside of Boston” and hope they don’t probe further? Or should you drop the H-bomb?

The phrase “dropping the H-bomb” was first used in The Crimson in a 1990 essay recounting a “particularly typical, particularly terrible conversation that revolved around the college question.” Its popularity skyrocketed around 10 years ago, says English professor James T. Engell ’73. “You could barely open a student publication or The Crimson or some memoir without seeing a reference to somebody dropping the H-bomb,”

he recalls.

Indeed, numerous articles from The Crimson during this time discussed the H-bomb from various angles: using the Harvard name to attract dates, arguing against the awkward (and usually ineffective) “a school outside of Boston” tactic, and analyzing how politicians leverage their Harvard degrees in campaigns.

But for a period of time, the term also referred to something else: the college’s student-created porn magazine “H Bomb,” whose establishment made national headlines in 2004 and ignited equal parts excitement and backlash. The spark, however, quickly fizzled, and the magazine’s brief stint ended in 2007 due to low membership and insufficient funding.

Still, the phrase in its original sense has stuck around to this day. In our survey, 77 percent of students said they immediately drop the H-bomb when asked where they go to school, while 16 percent answer indirectly. A handful of respondents prefer to lie altogether, giving the name of a different school when asked. Memorable reactions to dropping the H-bomb range from awe (“Hinge date in Scotland took a picture of my ID to show his friends,” wrote one respondent) to sarcasm (“never heard of that place before”) to “visibly turning away and avoidance.”

The H-bomb, then, is an unpredictable weapon, one that ought to be deployed with care. As Harvard College Dean Rakesh Khurana himself advised: “Don’t gratuitously drop the H-bomb.”

proportions is underway. The battleground? How to refer to the freshman dining hall, Annenberg Hall. Although previous classes often shortened the name to “’Berg,” some in this year’s batch of freshmen are trying to make a perfectly good name longer. These radicals now call it “the ’Berg.”

The difference between the two colloquialisms — a single article — may seem trivial. Not so, according to the freshmen we cornered on their way to lunch.

When asked about the phrase “the ’Berg,” Grace M. R. Liu ’26 doesn’t miss a beat: “It’s weird.”

Cooper B. McCann ’26 goes further. People who use “the ’Berg,” he says, “should be kicked out of this school.”

Still, others defend the up-andcoming slang. Although Hans O. Elasri ’26 agrees the subject is contentious, he remains firm: “I’m a

Among the Class of 2026, a linguistic struggle of monumental

big ‘the ’Berg’ advocate.”

Perhaps the battle is not as new or as widespread as students think. Multiple articles in The Crimson, from 2001 through the present day, use “the ’Berg.” If anything, the debate over using the “the” makes visible the minute processes by which language changes. As different slang phrases compete, one student might make fun of a variant used by their friend, while another is convinced of that variant’s superiority.

Maybe in 10 years, every freshman will talk about eating at the ’Berg (and then Dean McCann will kick them all out).

Or perhaps they will opt out of the debate entirely. When we ask Sierra Valdez ’26 which dining hall abbreviation she prefers, she shrugs: “I say Annenberg.”

When Adam P. McMullin ’23 arrived on campus in fall 2021, he noticed something strange. While reading emails over the summer about the new Science and Engineering Complex in Allston, he had always mentally pronounced the abbreviation SEC as if it were a word — “seck.” At school, however, nobody said it like he did.

“People were like, ‘Why are you calling it that?’” he says.

Since the shiny, billion-dollar, cheese-grater-esque building opened last fall, most students have been calling it the “ess-ee-sea.” But this year, McMullin’s alternate pronunciation has begun a quiet ascendance — enough that multiple survey respondents recommended we investigate it. This linguistic shift is unique in its history: not only is it verifiably new, but we also seem to have found its exact starting point.

Last fall, despite the puzzled reactions he received, McMullin

wasn’t perturbed.

“I just continued to call it the ‘seck,’” he says. Slowly, his friends started using it, though not necessarily by choice. “They say it by accident, mostly,” he admits. Then “they go, ‘oh, I can’t believe I just called it that.’”

This spring, however, McMullin started actively proselytizing. As a Mechanical Engineering concentrator, he had ample opportunity to do so.

“Anytime I was in the makerspace [in the SEC], I was trying to spread the word to call it the ‘seck,’” he says. Reactions were mixed, but the pronunciation eventually began to catch on. By now, McMullin says, “there’s definitely a nonzero percentage of people that say it.”

But McMullin is not satisfied. In time, he hopes his pronunciation will dethrone “ess-ee-sea.” To him, “seck” is easier — one syllable versus three. He also points out how students at Harvard read acronyms like words all the time: SOCH, SEAS, etc.

“All of our acronyms on campus get condensed into whatever’s easiest to say,” he says. “I don’t see why we don’t do that for the SEC.”

He certainly convinced us.

Going to Harvard changes you. We might come onto this illustrious campus clueless about what we’ve gotten ourselves into, but by the time we each find our way out of the bubble and into the world, Harvard students have become experts at our own game. The constantly evolving Harvard language we question, try to reject, then eventually adopt into our own lexicon is no exception.

But Phoebe Nicholson, an executive editor for the Lexicography team at the OED, believes that although language is constantly changing, it is crucial to know its origins.

“Language works alongside life; it’s not something that we engineer,” she says. “Having that understanding of the historicity [of language] is kind of like understanding history full stop. If you see what’s happening in the past, then you can understand now better.”

If there’s anything we’ve learned, it’s that whether it was assigning new meanings to old terminology, forming new terminology for old meanings, or the birth of something new entirely that needed a word to match, Harvard students have always demanded unique language to capture our unique experiences.

An Oxford University alum, Nicholson is reminded of her own alma mater after hearing of Harvard’s habit of creating words for what could be universal language for the college experience. “Even if it is a direct synonym and if it doesn’t have any other connotations, I think there’s something in saying ‘concentration’ as opposed to ‘major’ which is identifying yourself as part of that in-group and as like, ‘this is a Harvard thing,’” she says.

So maybe we’re a little pretentious. But maybe it’s also just in human nature to want to feel special. At the end of the day, we all exist in an endless multitude of in-groups and communities that create mini languages to describe shared experiences — whether it’s the TikTok your blocking group incessantly quotes for a week, the nickname for the hookup spot in your hometown, or a decade-old inside joke with your family.

Harvard does change us, in a million big and small ways, but we also change Harvard. Everywhere we go and in every space we inhabit, we leave a mark on the words that shape our reality. We’ve explored 15 to start — the rest is up to Harvard generations of the future.

David A. Kennedy-Yoon ’23 never entirely forgets that we’re recording. That he finds this type of attention unsettling surprises me a little: He received this year’s nomination for Class Clown, thanks not only to his well-liked Twitter account but also to his ever-growing routine of live bits. (His most recent: performing at the annual Halloween organ recital in Memorial Church while dressed as Dracula.) Kennedy-Yoon explains that while he certainly goofs around a lot, he’s naturally a “very anxious person” who takes time to open up to others. Four of the people who nominated him came up to tell him afterwards, in an “‘Ah, gotcha!’ kind of way,” he says.

The kinds of jokes he likes to make call attention less to himself or others than to absurd situations. (His blockmate, Jennifer Luong ’23, says that one of his tactics is repeating the same silly word or phrase over and over again until it loses all meaning and reduces his group of friends to laughter; his most successful move is asking for their feedback in the form of “Fire emoji? Or crickets emoji?”)

This sensibility stems from his involvement with Satire V — where he serves as co-president — as well as from what he sees as the purpose of comedy: connecting with others.

Kennedy-Yoon joined Satire V as a writer and graphics editor his freshman fall. The content the publication put out always “made him giggle,” he says, and he hoped to find a new source of community in its staff. He found the atmosphere infectious — “it fed off itself, similar to a nuclear fission reaction” — as well as a welcome reprieve from a stressful environment. “The motto of Satire V is to afflict the comfortable and to comfort the afflicted, which I think is really sweet, and that’s how I felt freshman year when I was kind of going through it,” he says.

The publication aims to poke fun at the more ridiculous aspects of Harvard. At this year’s Activities Fair, for instance, it ran a booth dedicated to the IOP — that is, the “Institute of Pee.” Members wore white lab coats and held beakers full of yellow Gatorade while encouraging freshmen to join. The point was to satirize the rather formal and pre-professional mindset of the Institute of Politics, which Kennedy-Yoon describes as “grabbing freshmen and

putting them on track to work on Wall Street or what-not.” (Staffers from the real IOP stopped by to scold the group but ended up taking pictures with it instead.)

Outside of comedy, Kennedy-Yoon finds a creative outlet in music. He concentrates in the subject, in fact, in addition to leading the Harvard Organ Society. He started playing the piano in elementary school, and, finding himself drawn to the “more mathematical works of Bach,” tried his hand at the organ in middle school. From his very first lesson, he remembers feeling “entranced” by the power of the instrument, whose notes he not only heard but felt resonating in the room. “When you’re playing, it’s almost like you’re operating heavy machinery,” he says. “It’s how I imagine it would be to fly a helicopter.”

Kennedy-Yoon has dedicated his thesis to examining how the materiality of the organ gives it such agency and power. He plans to focus on the ways the instrument has been anthropomorphized, as well as on its relationship to religion. He describes writing as a “joy” — he could talk for hours about the organ, given his “obsession” with the instrument.

These forms of expression relieve him of some of the pressure of schoolwork; in addition to completing his thesis, the other looming to-do on his list is to complete the MCAT.

Kennedy-Yoon realized he wanted to enter medicine at age seven, when he first received treatment for type I diabetes. “I would go in as a kid and feel miserable and lousy all the time, and then talk to this person in the big coat, and then feel good, like all my problems got solved,” he explains.

His experience shadowing doctors has only strengthened his sense of the value of the care such professionals can provide. “Some of the most powerful things I’ve seen have been the ways doctors really make patients feel like they are in control again — feeling like you’ve lost your locus of control to the outside world is just such a desolate feeling,” he adds. “But I mean, I don’t know, I was just thinking — so … fire emoji or crickets emoji?”

Kennedy-Yoon plans on taking a gap year before he applies to medical school. During this time, he intends to continue the lab research he’s conducted at the Dana-

Farber Cancer Institute since his junior year. He didn’t expect to enjoy the work as much as he does, but now sees the unexpected challenges in experiments as “puzzles to be solved.” His group aims to improve the robustness of a novel immunotherapy — CAR-T cell treatment — for patients with multiple myeloma.

He repeatedly expresses gratitude for the buffet of options the College provides, and he notes that while his particular combination may seem disconnected, each interest brings him a particular kind of joy. He constructs his own throughline for this piece: “Linking [the point on

research] to comedy, we will always have tribulations and pressures and tensions in our lives and it’s how we choose to resolve them that really determines whether the music in our lives is a harmonious concoction or a dissonant one — You want a big line? You want a big line? There it is.”

He takes the slightly awkward, artificial situation we’re in — I had just expressed to him my discomfort in claiming to know him after a brief interview — and makes light of it. He takes back the line and then decides to stand by it; we both laugh and feel a bit more at ease.

Nour L. Khachemoune ’23 says her friends fondly call her NBC — the Nour Broadcasting Company — because she seems to “know everything that’s going on.” This curiosity is also the driving force behind her ambitious, interdisciplinary thesis. Khachemoune is using chemical analyses to study rabbit and turkey bones from a Mayan site in Honduras to understand how humans changed the diet of animals in the 1890s.

“Nobody really knows what these bones are, or what we can determine from them,” she explains to me as we walk through the Archeology department, nested on the fifth floor of the Peabody Museum. “Harvard has a long history of collecting things and leaving them in storage and not doing much with them.”

Khachemoune begins her work by studying bone collagen to determine if the fragments actually belong to the species on the museum’s labels. She finds the tactile work great fun — and making novel discoveries about the species of a particular fossil (which is rare for an undergraduate) is just an added bonus.

“We’ve found that the actual species ID is completely different from what the Peabody thought it was,” she says, adding that the museum has been receptive to changing labels when this has happened multiple times.

Then, she analyzes carbon and nitrogen levels in the bones to determine their exact age before using various chemical techniques to tease out the animals’ diet. Based on these diets, researchers can make inferences about how humans interacted with the animals. For example, if a protein-rich diet is found for an animal that is known to primarily eat corn, it is possible that humans were responsible for introducing proteins to the animals through domestication.

Khachemoune loved chemistry all throughout high school and came into college sure that her path forward would involve studying small molecules and reactions in labs. However, taking Gened 1105: “Can We Know Our Past?” made her rethink this decision. Khachemoune says learning from renowned anthropologists Rowan K. Flad and Matthew J. Liebmann, who taught the course, shaped her thinking about interacting with artifacts and analyzing the past.

“At first I was like, ‘this is such a pain, who cares about this,’” Khachemoune recalls. But soon, she recognized lab techniques she already knew being applied to study scientific history. “I started to get more interested in the people and the story of how we got here.”

One of the class’s guest lecturers — Christina Warinner — gave a riveting lecture on scientific archeology. Inspired by this session, Khachemoune went on to take Warinner’s introductory class on archeological science that spring. Later, Warinner became Khachemoune’s thesis advisor, and one of the class’s teaching fellows is now her direct lab supervisor.

But just as Khachemoune had identified these fledgling passions and mentors, the pandemic kicked everyone off campus. She decided to spend the year as a medical assistant, helping mostly older patients.

“I learned so much about the people and how human being a doctor is, and I heard so many people’s different stories from all ages,” she says. Her passion for medical anthropology grew, and she realized that developing treatments through chemistry alone would not be satisfying.

In addition to teaching Khachemoune how chemistry, biology, and earth science techniques can inform archaeology research, Warinner gave Khachemoune the confidence to propose a bold joint concentration combining chemistry and archeology.

“[Warinner] was hired to be a scientific archaeologist here at Harvard, because that’s the direction the field is going,” Khachemoune says. “She’s just such an inspiration for combining fields and in being a strong woman in science.”

Scientific archeology is a burgeoning field that allows researchers to tackle big questions about how societies form and fall. For example, understanding animal diet and domestication can be a portal to understanding the health of a society. Khachemoune says we don’t know a lot about Mayan civilizations, from their language to how they traded with other cultures. Her own thesis could help researchers understand how food sources connect to their civilizations’ development and demise.

In her lab, Khachemoune shows me little bags of animal bone, some with bite marks or small jagged cuts across

their edges. She says the research feels “really real” when she holds the fragments.

“Through this tactile process, I’m seeing these animals and these people’s stories in the past,” she says, walking around a slightly cluttered array of lab equipment and storage bins. “It’s sort of like eavesdropping, investigating, observing.”

Khachemoune’s motivation to work on a thesis for years, even when progress is slow, comes from loving the science, loving the lab work, and working with her hands. She encourages future thesis writers to establish their own workflow — even if it means defying a deadline set by an

adviser or doing some parts of the project out of order.

She also leans on the broader archeology community — she says hierarchies between graduate and undergraduate students dissipate in the genuinely collegial department. Best of all, she says, her mentors ensure that work from students like her who “aren’t even going to be archaeologists” is taken as seriously as that of students who want to go into the field. Even though she hopes to go to medical school, Khachemoune says she wants to use scientific archeology to try to “connect the smaller details of chemistry to the overall human journey.”

In the basement of the Northwest Building, the bright red plastic desk chairs are the only splash of color amid dull gray concrete floors, plain white tables, and bare walls. But Chris P. Wirth ’23 and Amy E. Benedetto ’23 see more than an austere room — they see the place where they bonded over lunches, raced chairs when they got tired of studying, and began their threeyears-and-counting relationship.

Wirth and Benedetto met during a section of Math 23 the first week of freshman year, but they lost touch after Wirth was assigned to a different section. They only reconnected after running into each other at a party in Pfoho’s Igloo and exchanged contact information.

After they started talking, Benedetto decided to make a “bold move” and invite Wirth to her performance with the Harvard Ballet Company. “Most guys in college probably wouldn’t want to come see a ballet show,” Benedetto says. “So I was fully expecting him to be like, ‘Oh, no, I’m busy.’”

Instead, Wirth showed up early, sending a picture of his ticket when he found a seat and giving her flowers after the show. Soon after the performance, they started dating.

Midway through their freshman spring, though, the pandemic struck, so they did a year and a half of longdistance. During their virtual sophomore year, they both returned as course assistants for Math 23, running review sessions on Zoom together.

Now seniors, Wirth, an astrophysics concentrator, and Benedetto, a chemical and physical biology concentrator, recently celebrated their three-year anniversary.

Wirth and Benedetto attribute their lasting relationship to their similar interests and perspectives. “We’re always on the same page about everything,” Benedetto says. Whether it’s how much they’re willing to shell out on Taylor Swift tickets, or their opinion on the latest TV show they’re watching, they say they often find themselves coming to the same conclusion before talking to each other.

When they go on dates, they like to get Italian food or Pokeworks. And for Valentine’s Day, their tradition is to order in Thai food and “chill together.” They like to take a break from work to cuddle up and watch an episode of a TV show — “Friends,” “Brooklyn Nine-Nine,” and “New

Girl” are favorites.

One of their most memorable dates was for their twoyear anniversary last fall. Wirth took Benedetto to various places that were important in their relationship and gave her a small gift at each one — pens at Northwest to represent the proofs they wrote in Math 23, a rose where her ballet performance took place, and so on. “Every time I tell people this story, they freak out over it,” Benedetto says. “That was pretty cute,” Wirth says. “I’m proud of that one.”

Wirth and Benedetto also spend time together with their friend group, formed through their freshman year math and physics classes. Nowadays, the group likes to play Nintendo Switch Sports Volleyball, where Wirth and Benedetto say they make a great team.

They appreciate how their shared friend group gives them more time together. “It’s nice to be with your friends and also with the person that you care about the most,” Benedetto says.

Wirth and Benedetto acknowledge that to some degree they were lucky to find each other. But they also think that Harvard can be a good place to find a relationship. “Harvard brings a lot of people together that are all hard working, they’re driven, all really intelligent people that care about similar things and care about other people,” Benedetto says. “I think being in that Harvard environment definitely helped me find a cute little smart Harvard boy.”

“We’re very driven people,” Wirth says. “And so if that drive is to get cuffed, it’ll happen.”

However, Wirth and Benedetto say their busy Harvard schedules can keep them apart. They usually set fixed times to hang out — at least once during the week and once on weekends — and figure out when they have shared lunch times. “We see each other outside of those times for spontaneous hangouts when we don’t have work for some reason,” Benedetto says, “but we definitely have to set times to make sure we get to see each other.” Sometimes even fixed times fall through, though, when someone has a midterm or big assignment.

With graduation approaching, Wirth and Benedetto intend to stay close even as they work towards doctoral degrees in chemistry and astrophysics, respectively. They

hope to end up at the same graduate school, or at least on the same coast. “It will depend on what schools we get into but we’re definitely optimistic,” Wirth says.

Their friends frequently talk about them getting married, even planning their roles as bridesmaids and groomsmen. Wirth and Benedetto aren’t planning on getting married any time soon, though, so the talk can be “a little bit nerve-racking,” Benedetto says.

“What if we disappoint our friends?” she says, laughing.

But ultimately, they are grateful to have each other’s support. Wirth says he loves “having someone you always feel like you can come back to and always talk to about anything and is there to support you and knows exactly what you’re going through.”

And they were happy to be chosen for the superlative: “We think we’re pretty iconic.”

Alexandra J. Fogel ’23 is not your typical “career” tribute (for those who didn’t have a YA phase, the brutal and brawny teens trained from birth to win the Hunger Games).

Her preferred strategy? “Find a good place to hide.”

In this hypothetical fight to the death, she considers her greatest strength her ability to outlast rather than overpower. At Harvard, she’s learned how to rock climb — useful for hiding away in a tree — and to identify native plants. Most importantly, she cites her ability to anticipate and adapt to environmental changes, developed over years of being immersed in nature.

“A sense that I’ve picked up from having spent a lot of time in the outdoors is being able to get to know the ecosystem I’m in,” she says. “How the elements are going to change, and how that’s going to affect me, what I need to do.”

Fogel has had an affinity for the outdoors ever since her parents enrolled her in a two-month summer camp in New Hampshire called Camp Walt Whitman. It was there, at age 12, that she went on her first backpacking trip. Over nine years as a camper and a stint as a counselor, she “fell in love” with hiking and backpacking.

That love eventually expanded to all things outdoors: camping, climbing, rafting, and boating. While she feels “empowered” pushing her physical limits on a multi-day hike or a new climb, Fogel finds the mental challenge rewarding as well. “I think a lot of outdoor pursuits are more mental than physical,” she says. “And that’s something I personally enjoy.”

This mental aspect of the outdoors comes not just in the challenges it presents but also the opportunity to exist in the moment. “I don’t think I really understood what people meant by [mindfulness] until I connected it to being outside. When I’m climbing or hiking, I’m truly present in a way that I never am in any other circumstance, and I think it’s because you don’t really have a choice but to live in the moment.”

Nature is one of the main ways she’s found community

at Harvard. After joining Club Climbing her freshman year with the encouragement of her PAF, Fogel served as president of the group last year. Post-presidency, she says her role on the team has now transitioned to “the fun mom who brings snacks and gets them really excited about going to practice.”

Fogel has also served as a trip leader for three of the nature-focused groups on campus: the First-Year Outdoor Program, the Harvard Outing Club, and the Harvard Mountaineering Club. Last year, she led HMC and Club Climbing’s spring break trip to Red River Gorge in Kentucky. After some Covid-induced delays, she finally led her first outdoor FOP trip this past summer.

Leading trips is special for Fogel because she gets to introduce people to the “wonder” of being outdoors. She says her personality as a leader is the always positive camp counselor type: “So even when on the face of things it’s objectively shitty — uh, or not fun — you have to find a way to get people excited about what’s happening.”

While being in nature might seem like a chance to get away from the world, Fogel appreciates how the outdoors gives relationships a “really unique way to grow.”

“Even people who in the regular world you might not have gravitated to or become friends with, you appreciate them for who they are,” she says. “Everything is reduced to its essentials, and people’s true personalities really tend to shine.”

Another way she’s been able to bring the outdoors into her life is in the classroom. Fogel taught her Expos 40 class how to tie figure eight knots in a “speech to teach” activity. “I could do it blindfolded,” she shrugs, which made it the natural choice.

As a Social Studies concentrator, her focus field is in public health and the environment. She’s merging this with her secondary in Earth and Planetary Sciences to write a thesis comparing government responses to Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy.

“Something that I’m really interested in is how climate change is going to affect our health infrastructure, and

how climate migration is going to affect health systems,” she says. “How are our health systems going to adapt to accommodate influxes of people and changing disease profiles?”

Fogel takes advantage of every opportunity to explore nature, insisting it’s not too difficult to find places even in a city like Cambridge. “We have wonderful spots that are all either walkable, bikeable, or T-able,” she says. She frequents nature reserves like Fresh Pond (walkable) and Middlesex Fells (T-able).

Beyond even Middlesex Fells is a goal Fogel has been working toward for almost a decade: hiking all of New Hampshire’s 48 “4,000-footers.” While she only learned about the milestone from some HOC trip leaders, Fogel unknowingly started completing the list as a camper, climbing “pretty much every mountain” in the state’s White Mountains. So far, she has climbed all but six of the 48.

“I think I can finish by the time I graduate,” she says with confidence.

Will M. Sutton ’23 wants to be a history teacher. This is not hard to picture. I met him twice for dinner, and both times he came wearing flannels and tough boots, carrying an air of burly wholesomeness and a do-good spirit that reminded me of my own high school history teacher.

At Harvard, Sutton’s intended path to the classroom — rather than a stint at law school or a gig at a consulting firm — is unusual. There are those who push him to try his hand at something — anything — else. “I had a professor who I told I was interested in teaching, and they said, ‘There’s a lot of ways to carry on that passion. You can be a teacher in the boardroom, for example.’”

Friends “who know me tend to get it,” he says; they recognize a restless altruism. The History concentrator says teaching satisfies his three criteria for a future career: “that [it] would make me happy, be sustainable, and make the world a better place, in some small way.”

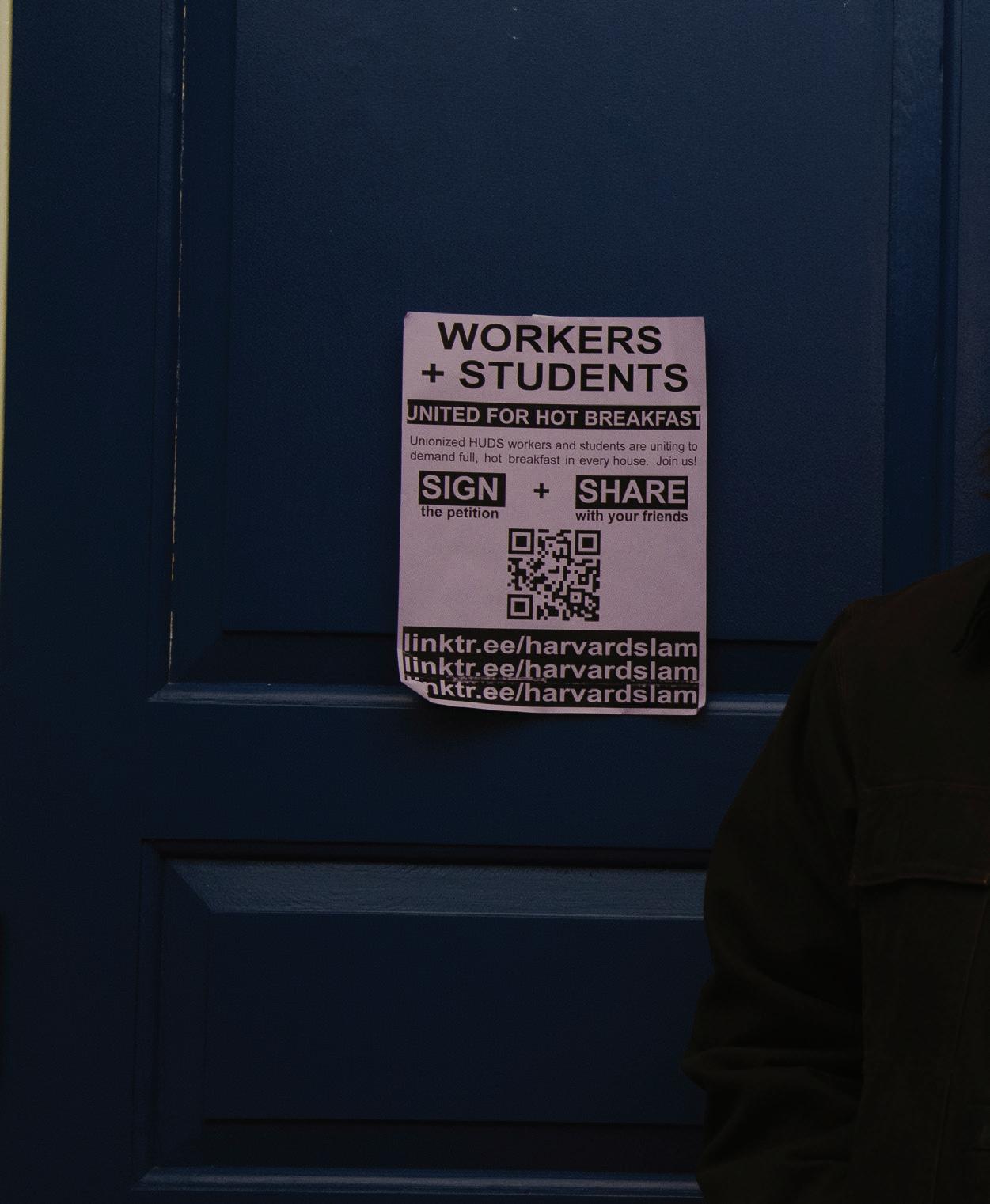

But education is only one of many avenues through which Sutton has tried to live by these ideals. His dedication to bettering the world around him and creating community for his peers led Sutton to campus activism, community jogging, and a seat on the Lowell House Committee.

He’s spearheaded undergraduate efforts to advocate on behalf of the Harvard employee unions and pushed reforms to dismantle rape culture on campus. “I’m always picking fights with the administration; it’s like my whole job,” he jokes. “And it’s well-documented in the pages of The Crimson.”

Sutton spent much of this fall taping up flyers and tabling to garner student support for hot breakfast to be reinstated at all campus dining halls — a collaborative effort between the University’s dining hall workers’ union, UNITE HERE Local 26, and the Student Labor Action Movement. The petition collected over 2,000 student signatures, and the Harvard Undergraduate Association expressed its support in its November email to students.

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, Sutton

and members of Our Harvard Can Do Better, a coalition of students organizing to end campus rape culture, met with administrators to discuss an amnesty policy for students living on campus who came forward with a complaint of sexual violence during lockdown restrictions.

Though the administration eventually added the amendment after SLAM rallied public pressure, Sutton says that in initial meetings, the administrators “were not really budging, and they were giving us the runaround.” In these instances, Sutton, who otherwise admits he’s a strange face in the rape culture conversation, says he’s noticed that “I can be taken more seriously by male administrators, so I’m

gratitude for every hole-in-the-wall.

He rattles off the names of several professors and grade school teachers when asked to name just one who made a difference; he can’t pinpoint a single inspiring course but rather appreciates his amalgamation of credits in Indigenous studies, poetry, and religion. He tells me he’d want to have dinner with Assata Shakur — a freedomfighter whose biography he read after the College awarded him a free copy — or one of the many Black feminist writers and activists who’ve inspired his worldview.

Sutton is also thankful for all who came before him at Harvard. He has stepped into leadership roles out of goodwill and a desire to “pay it back for everything that other presidents have done for me,” he says, knowing the responsibility “wasn’t going to be a cake walk.”

As the vice president of the Running Club, he rallies about a dozen students for daily afternoon runs, a task that gets harder as the weather chills and assignments pile up. Nonetheless, he’s glad to have “cobbled together a community” of joggers that have been there for him since his first month at the College.

Grateful for the previous Lowell House Committee Stein Chair, who organized events that helped him find his bearing by the River — he had considered transferring to Cabot House before — Sutton also ran for a HoCo seat and became the next chair. Lowellians can thank him for Thursdays at the Museum of Stein Art, Stein Wars laser tag, Liechtenstein, and Fancy Stein.

interested in leveraging that.”

Harvard has been a unique canvas for his activism. “You’ve got to be critical of the power that Harvard has as the most powerful university in the world,” Sutton says.

“From an activist, organizing perspective, I think it’s sort of a unique place to cut my teeth because it’s Harvard, you know? It’s an opportunity to really push the university to lead other universities to be a better community.”

Sutton appreciates everyone and everything, no matter how small. Though he’s spent the most money on chicken quesadillas at Jefe’s, he couldn’t settle on a favorite Harvard Square eatery, his indecision a product of a genuine

The driving force behind all these efforts, he says, was “having a real love for each other, because it felt like we were trying to make life better for no particular reason other than it was the right thing to do.”

If you’re still unsure why his peers designated him as their unsung hero, you can also thank him for good homemade memes. Sutton wouldn’t reveal his Sidechat score, but he says he’s unintentionally ascended the leaderboards there as well. Besides rallying the student body for hot breakfast for all, union workers’ rights, and afternoon runs, he’s united us in banter against vegan cheese and final clubs, too.

We could all learn something from Anil M. Bradley ’22-’23, the heavy metal superfan, Physics-turned-ComputerScience concentrator, and verifiable gym bro named Most Chill member of the senior class.

I meet Bradley at Shay’s Pub on a cold weekday afternoon. His outfit (a backward cap and a camo sweatshirt) and his order (a beer) match the preferences I imagined the Chillest Harvard Senior would have. So, too, does the start of our conversation.

“I got the email for Most Chill, and one of my friends just won Rhodes Scholar and Phi Beta Kappa on the same day,” he tells me. “I was like, ‘That’s cool bro, but I’m chill.’”

Bradley describes his relationship to chillness throughout the past four and a half years as “a straight line upwards.” Taking a year off after his sophomore year only accelerated this trajectory. He thinks his perception as a chill guy mostly boils down to his trying to be nice and approachable, and avoiding getting worked up or angry or stressed, which he says “feels like an exception on this campus.” He has his priorities in check. “I don’t really need to worry,” Bradley says. “I’m more concerned about enjoying myself, getting my sleep, going to the gym.”

When it comes to sleeping, exercising, and eating, Bradley has a fixed routine. He sleeps about 10 hours a night — after some reading before bed, he’s usually out by midnight and up the next morning at 10. He’s been in the powerlifting club since freshman year and lifts about four to five times a week, a habit he says he’s religious about. His dietary habits are also predictable. “I hate the dining hall,” Bradley says, although he’ll eat it if he “has to.” Pinocchio’s Pizza is his establishment of choice. “I’m at Pinocchio’s literally every day,” Bradley says. “I feel like it’s the most chill place to eat.”

The average, unchill Harvard student probably fears chillness because they think it will disrupt the prospects of their future success and intellectual focus. But Bradley’s laidback attitude hasn’t doomed him. “Like, I’m passing,” he tells me, when I ask about the extent of his chillness. “I have a 3.2. I’m not failing, but I’ve definitely gotten my Cs.”

During his year off, he worked as a construction manager near his home in Long Island. This past summer,

he was a project manager intern for a sports gambling company. Next year, he’ll live and work in Brooklyn at a startup alongside a few friends. He feels no desire to emulate the workaholic “investment banker lifestyle,” but he’s also not a big partier. His preferred weekend includes a lot of “hanging out.”

In addition to being “just a young guy living in Brooklyn,” another part of post-grad life Bradley is looking forward to is cooking. When he was in high school, he was a baker for a local bagel shop. During the school year, he’d work from 5 a.m. to 1 p.m. on the weekends; over the summer,