FM CHAIRS

Hewson Duffy ’25

Kaitlyn Tsai ’25

DESIGN CHAIRS

Sami E. Turner ’25

Laurinne Jamie P. Eugenio ’26

MULTIMEDIA CHAIRS

Julian J. Giordano ’25

Addision Y. Liu ’25

FM EDITORS-AT-LARGE

Yasmeen A. Khan ’25

Jade Lozada ’25

FM ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Io Y. Gilman ’25, Ciana J. King ’25, Sage S. Lattman ’25, John Lin ’25, Graham R. Weber ’25, Sam E. Weil ’25

Jem K. Williams ’25, Dina R. Zeldin ’25,

Sazi T. Bongwe ’26, Maeve E. Brennan ‘26

Rose C. Giroux ‘26, Ellie S. Klibaner-Schiff ’26, Adelaide E. Parker ’26

FM DESIGN EDITORS

Julia N. Do ’25

Olivia W. Zheng ’27

Xinyi C. Zhang ’27

FM MULTIMEDIA EDITORS

Briana Howard Pagán ’26

Lotem L. Loeb ’27

COVER DESIGN

Olivia W. Zheng ’27

PRESIDENT J. Sellers Hill ’25

MANAGING EDITOR

Miles J. Herszenhorn ’25

ASSOCIATE MANAGING EDITORS

Claire Yuan ’25

Elias J. Schisgall ’25

Dear Reader,

The election may be over, but Harvard is still reeling. In 2023, just over 5% of freshman at the College identified with the Republican party, according to The Crimson’s survey. Now, in the wake of the GOP’s victory, that small minority seems to be allied with the majority of American voters. As Harvard confronts this disconnect, there’s no better time to take a look at the students within the University who may stand to have the most sway in the coming administration.

In this issue’s cover story, RAD and SS take a deep dive into the world of conservatives at Harvard. Though operating often quietly and behind the scenes, couched in Western philosophical theories that appear to be removed from politics, these people and their organizations in fact espouse the very ideas that underlie the modern New Right movement. Through dogged reporting and thorough research, RAD and SS reveal the implications of this and the way these intellectual conservatives can and will shape politics.

XSC opens up the rest of the magazine with a profile of a very different sort of powerful (former) students. Michael T. Horvath ’88 and Mark S. Gainey ’90 are the founders of Strava, and they talk to her about how the popular fitness-social app came to be.

Next, MMH and AAK talk to AnhPhu D. Nguyen ’25-’26 and Caine A. Ardayfio ’25-’26 about the AI sunglasses they created that can recognize people’s faces and provide the wearer with information about complete strangers. Are the glasses—as Nguyen and Ardayfio contend—a public awareness campaign, or are they just creepy?

Out in Harvard Square, RZN and KEH check in with the Square’s street performers and how they’re navigating the location’s changing character. Later on, ASA and NSK chronicle the real-life rom-com that led Rachel Kanter to create Lovestruck Books, an upcoming local bookstore specializing in romance novels.

Even outside the bookstore, love and joy seem to be in the air. AAK and ASM experience the “gleeful absurdity” of Harvard’s undergraduate whistling society, the completely unserious club that has also performed at Yardfest. The prolific KJK (or perhaps I should call her Patrick Boyleston) pens an irreverent ode to Panopto’s 2x speed function.

Finally, CJK closes out the issue with a somber and exquisite endpaper on incarceration, the killing of Marcellus Williams, and choosing love.

And that’s our second glossy. Sit down with it for a minute, or an hour. Keep it around the next one, or two, or four years. We’ve got a long way to go.

Sincerely Yours, HD & KT

NEW RIGHT — Ask them, and they might insist that theirs is not so much a political project as is a philosophical one. But this same insistence on deep questions has also informed a rising conservative political movement which eschews traditional Republican politics in favor of more philosophical, and often more radical, views. SEE PAGE 14

WHISTLING SOCIETY — Every Wednesday, students gather to hone their whistling skills.There’s no sheet music, nor specified harmonizations; rather, attendees simply whistle. SEE PAGE 22

HOLDING SPACE — “But no one tells you how to cope with a modern-day lynching.” SEE PAGE 30

STRAVA FOUNDERS — The popular fitness app emerged through a friendship between former lightweight rowers Mark Gainey ‘90 and Michael Horvath ‘88. SEE PAGE 4

FACIAL RECOGNITION GLASSES — Media outlets have framed Caine Ardayfio ’25-26 and AnhPhu Nguyen ’25-26 as architects of a doxxing device. But the pair argue their glasses are a “public awareness campaign.” SEE PAGE 8

STREET PERFORMERS — Harvard Square has become home to a vibrant group of entertainers, from guitarists to spray-paint artists. For them, the Square is not just a platform but also a source of memories. SEE PAGE 12

BY XINNI (SUNSHINE) CHEN CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Every afternoon in the mid-1980s, a group of Harvard lightweight rowers would hurry towards Leavitt and Peirce, the tobacco shop in the Square, to catch a glimpse of that day’s training schedule. In an age without the internet, reading the paper plan posted on the wooden boards of Leavitt and Peirce created a sense of ritual for two young rowers, Mark S. Gainey ’90 and Michael T. Horvath ’88.

Several years later, these two would revisit the communal feeling in Stanford’s Economics Department, where Horvath was an assistant professor of economics.

Surrounded by the four walls of Horvath’s Stanford office — one of the only places with a stable internet connection in 1994 — the two dreamed up the idea of a “virtual locker room.”

The precursor to Strava was born.

Strava, a popular app that turns tracking physical activities into a social network, has garnered over 120 million users from over 190 countries. The app took off among Gen Zs and millennials during the pandemic sports boom as run clubs surged, and it continued to spread this summer.

From a young age, Gainey has been interested in entrepreneurship, watching his dad create ski carriers. In Gainey’s junior year at Harvard, he decided to buy hot dogs and Coca-Cola from local groceries stores and sell them at sports games.

Originally recruited to the College as a runner, Gainey injured himself in his freshman year and, encouraged by his coach, decided to try lightweight rowing to keep himself in shape. On the rowing

team, he met his future business partner, Horvath, who was a junior then and captain of the team.

“There was just a really great group of people that were in his class, and they took me under their wing,” Gainey said. “They were nothing but hugely supportive.”

In my recent conversations with Gainey and Horvath, one day apart, I asked

“In 1994-95 we were dreaming up, ‘What could we do with the internet?’”

— Michael T. Horvath ’88

the same question: What was the most memorable moment of their friendship? They both recalled a trip to Princeton.

“It was pouring rain in his very old Jeep, and going down to watch that race together,” Gainey reminisces. “That was kind of the beginning of what has now been a 30-plus-year friendship.”

Hovarth, designated driver, tells a similar story about the Jeep trip. “It had plenty of problems with it, like holes in the floorboards, and the roof leaked,” he says. “It’s crazy, crazy cold, and so there’s very little heat in this car. We drove down in the rain, watched the race, drove back in the rain, and so the trip itself was kind of miserable.”

Nevertheless, it was memorable. “That sealed our friendship forever.”

After Gainey graduated, the pair drifted onto different paths but kept in touch. They attended each other’s weddings, called,

OLIVIA W. ZHANG — CRIMSON DESIGNER

and occasionally visited each other.

Gainey worked with TA Associates, a growth equity firm, for four years before quitting and heading to Palo Alto to try to start his own business.

Horvath, on the other hand, pursued a Ph.D. in economics at Northwestern before heading to Stanford.

“When I was coming out of grad school, I got a Ph.D. in economics, and I was trying to decide which job to take. I had an offer from an East Coast school and an offer from Stanford, and I opted to go to the West Coast, largely because Mark was in Palo Alto, and at least I knew somebody there,” Horvath says.

At Stanford, Gainey frequented Horvath’s office where they bounced ideas off each other. Hungry to create his own company, Gainey pitched various ideas to different people, and Horvath was the one he clicked with.

“I think the honest answer was, he was willing to be my co-founder,” Gainey says. “Most of the people were just like, ‘These ideas are really bad, Mark.’”

“In 1994-95 we were dreaming up, ‘What could we do with the internet?’ It’s this new thing in our lives,” Horvath says. “And we said, you know, it’s kind of funny, but we really miss walking to Leavitt and Peirce and seeing what the workout would be, who would be working out with us. What if we could create that sort of feeling using the Internet?”

They settled on the idea of a “virtual locker room” but were too ahead of the curve — most people did not have access to the internet in 1995, and investors turned down their concept.

So, they pivoted.

They founded KANA, a customer email service company, after talking with sports analytics groups and realizing that businesses rarely answer their emails.

From 1996 to 2000, KANA grew to 12,000 employees and generated hundreds

“To me, if there’s a legacy, it’s that we seem to have created something that people really enjoy. It stayead fun even 15 years later; it’s still a fun place as far as something that’s social.’”

— Mark S. Gainey ’90

of millions in revenue. In less than four years, the company rode the highs of the dot-com bubble and went public in 1999 before eventually being acquired by AccelKKR in 2010 for $40.82 million.

“In a very short period of time, we had it from literally a piece of paper and an idea to employing over 1,000 people and having offices across the globe,” Gainey says. “Ringing the bell at the NASDAQ and doing all the things that some people wait an entire career to do — we did in the four years.”

RECORD. SWEAT. SHARE. KUDOS.

Though both Horvath and Gainey’s time at KANA ended in the early 2000s, they soon jumped back into the startup world.

After briefly considering founding a water delivery service, they returned to the idea of a virtual locker room in 2006. This time, the arrival of phones with GPS and internet helped push the platform mainstream.

“When we started Strava, we definitely had a mindset of, ‘Hey, let’s build this to last. Let’s see if we can create a trusted brand.’ I’d like to think we’re still on that journey, but that was a big lesson from the KANA days,” Gainey says.

In 2023, the app reached 120 million users. According to Gainey, its impact has been as deep as it has been wide.

Once, Gainey received a message from someone who lost 300 pounds because on Strava, “they found community, and it just kept them active.”

Another person, a cyclist, noticed that his heart rate was higher than that of his friends on Strava. “It forced him to go to a physician, and they found out that he needed a bypass surgery,” Gainey says. “He was basically asymptomatic, but he was at

risk of dying from a heart attack.”

“To me, if there’s legacy, it’s that we seem to have created something that people really enjoy,” Gainey says. “It stayed fun even 15 years later; it’s still a fun place as far as something that’s social. It doesn’t have a lot of the baggage that I think a lot of the social apps have had historically.”

In place of a bio, Horvath’s LinkedIn page simply states “Starting Things Since Last Century.” In a sense, he’s been creating companies since the 1990s. In the time since, life has taken its twists and turns.

A few years ago, Horvath stepped away from his role on Strava when his wife became terminally ill. He rejoined in 2019 and ultimately decided to step down in February 2023. When I met with him last week, he had just sold his Cambridge

apartment, and in a month, his daughter is expecting a child.

When I asked him what he would be up to for the next few months, he told me that in addition to spending more time with family, he was already working on something new.

“I’m not ready to talk about it, but all I will say — it should look a little different. I’m interested in exploring the kinds of opportunities that typically get overlooked by venture capital,” Horvath says.

“I want to start something where it’s specifically aimed at a smaller niche market, that you can really build a great product for and that then translates into a good business,” he adds.

A few hours before our interview, Horvath had just recorded a run on Strava around Cambridge. He posted photos of Memorial Bridge and a photo of stickynotes on a Canaday dorm spelling “Fall!”

Back in Cambridge, the place where it all began, Horvath simply captioned the run, “Chasing down a dream.”

BY MAIBRITT HENKEL

AND ANNA A. KREMER

In a recent video uploaded to X, Caine A. Ardayfio ’2526 approaches a woman at Harvard’s T station. Greeting her by name, he extends a hand: “I think I met you through the Cambridge Community Foundation, right?” “Oh, yeah,” she says with a smile, rising from her seat.

In reality, the two are complete strangers. The details he knows about her personal life aren’t thanks to a shared history of volunteering, but instead have been scraped from the Internet by a pair of facial recognition glasses that Ardayfio and AnhPhu D. Nguyen ’25-26 released last month.

The spectacles — dubbed “I-XRAY” by the duo — boast the tagline: “The AI Glasses That Reveal Anyone’s Personal Details — Home Address, Name, Phone Number, and More — Just from Looking at Them.” Since posting the clip, Ardayfio and Nguyen have amassed over 20 million views. They have also caught the attention of major media outlets, thrusting them into the center of a heated public debate over the uses of facial recognition technology.

Several media outlets have framed the Harvard juniors as architects of a terrifying doxxing device. The New York Post described the pair’s software as the stuff of “every stalker’s dream.”

or monetize their product. Instead, they claim I-XRAY is an “awareness campaign” that aims to publicize the dangers of facial recognition technology and improve digital privacy practices. But how do you spread awareness to the right people without feeding knowledge to the wrong ones?

Ardayfio and Nguyen first met as freshmen at a makerspace, a collaborative workshop for students tinkering on side projects. At the time, Ardayfio was fixing his electric skateboard, while Nguyen had come along to work on a hoverboard.

“We were like, ‘Oh you like to build things? I also like to build things! We should build a flamethrower together,’” Ardayfio says. (Sure enough, a video they later posted to X shows Ardayfio wielding an Avengers-style flamethrower in an empty parking

At Forbes, the duo are “hackers.” Meanwhile, the Register, a British technology news website, points to the public nature of their device as a potential “open source intelligence privacy nightmare.”

But Ardayfio and Nguyen say that they do not intend to release their code

Reality Club, they had a pair of smart glasses equipped with cameras, open ear speakers, and a microphone. The particular model they used was a RayBan and Meta collaboration that can be purchased for a few hundred dollars.

With pre-made hardware in hand, Ardayfio and Nguyen could focus on linking the glasses to their facial recognition algorithm. “The meat is in the software,” Nguyen says.

“Almost nobody knew you could just go from name to home address of any arbitrary person on the Internet.”

— Anhphu D. Nguyen ’25

lot. Its caption reads: “leg hair is fully singed,” followed by a fire emoji.)

Among their other projects, Nguyen and Ardayfio have built a robotic tentacle and an electric skateboard controlled by its user’s fingers.

This year, Ardayfio and Nguyen began working on I-XRAY. As cofounders of the Harvard Virtual

I-XRAY leverages the recording function in the smart glasses to feed video footage directly to users’ phones via an Instagram livestream. An algorithm written by Ardayfio and Nguyen then detects faces in the footage and prompts face search engines to scour the internet for matching images. If these images turn up an associated name, their software then scrapes publicly-available databases for personal data, pulling out anything from phone numbers to home addresses.

The coding took Ardayfio and Nguyen just four days. The real challenge, they say, was negotiating the ethical quandaries of releasing the video.

“We talked to quadruple the people we normally do and thought much more carefully,” Nguyen says. It took them a month to decide whether they wanted to post the video.

And no wonder: The technology behind I-XRAY already has a troubling track record. The glasses rely on PimEyes, an artificial intelligence service based in Tbilisi, Georgia, that matches online images to faces.

The tool has reportedly been used to stalk women and young girls and has spurred on digital vigilantism. PimEyes itself has blocked access to its technology in 27 countries, including

Iran, China, and Russia, citing worries that governments could use it to target political dissidents.

On a college campus, I-XRAY could also revolutionize social interactions. Ever overheard two strangers gossiping in a coffee shop? Ardayfio and Nguyen’s code has the potential to identify them in a matter of seconds. The same goes for anyone showing their face at a protest or rally.

Yet the pair considers their project a net benefit for society. “Our calculation was essentially that the number of possible bad actors who would use technology like this is several orders of magnitude less than the number of people who now know that these tools exist,” Ardayfio says, adding that the latter is now in the tens of millions.

access their personal information on the internet, challenging people’s assumptions of how they should act and whom they should trust in public.

Ardayfio and Nguyen argue that their “awareness campaign” has taught people how easily others can

“We think it’s best if people are straight-up aware that these things do exist,” Nguyen says. “When we talked to people before posting this, almost nobody knew what PimEyes was. Almost nobody knew you could just go from name to home address of any arbitrary person on the Internet.”

“That’s been nice: to have people know all of this exists so that you can choose to protect yourself if you do want to,” he adds.

It was important to Ardayfio and Nguyen to create adequate “guardrails” for I-XRAY. They wrote a Google Doc listing steps on how to opt out of services like PimEyes and linked it to their video. The pair hopes to highlight the potential for misuse of

this technology and inspire viewers to take preemptive measures against it.

But privacy experts raise concerns about whether anyone can fully remove themselves from appearing in the results of AI search engines like PimEyes. Ardayfio and Nguyen insist you can, though they concede that other privatized engines that do not provide the opportunity to opt-out could pop up in their place.

Do they have regrets over posting the video? Ardayfio shakes his head no. “I’m very comfortable that what we did was good and right, and that it has net improved the state of security for people,” he says.

Nguyen adds that their vision is that I-XRAY will spur the government to enact policy change with regard to public databases.

Besides public awareness, Ardayfio and Nguyen envision positive

applications for their glasses — most of which have garnered relatively little media attention. Nguyen suggests that wearable facial recognition technology could help emergency responders match medical records to unidentified patients. Or, as Ardayfio says, a modified version of

and Nguyen have been invited to present their work in several Harvard courses, including Kennedy School classes on democracy and privacy. They estimate that 90 percent of the remarks they delivered were centered on the ethics of the I-XRAY glasses, rather than the technology behind

building companies, not necessarily going viral,” Nguyen says, though he admits that future ventures “may involve some component of going viral.”

For now, the juniors are still receiving media attention. They have another interview scheduled back-to-

“Our calculation was essentially that the number of possible bad actors who would use technology like this is several orders of magnitude less than the number of people who now know that these tools exist.”

— Caine A. Ardayfio ’26-25

I-XRAY could support those suffering from Alzheimers who have trouble recognizing family members.

Since their video’s success, Ardayfio

them.

Looking forward, the pair says their primary goal is to have an innovative career. “We’re mostly interested in

back with ours, Ardayfio reminds us as we approach our scheduled end. The pair leaves promptly to make it on time.

Ardayfio and Nguyen argue that their “awareness campaign” has taught people how easily others can access their personal information on the internet, challenging people’s assumptions of how they should act and whom they should trust in public.

CLAIRE T. GRUMBACHER — CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

BY KAYSIA E. HARRINGTON

AND RAPHAEL Z. NIU

STAFF WRITERS

People pass through Harvard Square every day, from students rushing to their lectures to tourists streaming in and out of the COOP. The Square’s street performers, though, aren’t going anywhere.

Over the years, the area has become home to a vibrant group of entertainers, from singing guitarists to spray-paint artists. For many of them, the Square is not just a platform for their performance but also a source of many years of memories.

Despite the long history of performance in the Square, street performers are no longer as ubiquitous as they used to be. Some performers claim that the area used to be more lively, drawing larger crowds of engaged viewers. Still, there are several artists keeping the performance scene in the neighborhood alive.

“I have been doing my spray-paint performance here for 23 years,” says Antonio Maycott. On every other Saturday afternoon, he sits nestled against the glass elevator in front of the Harvard T stop. Having painted for so long, he has seen freshmen grow into fathers — “they already have kids and they come to visit me,” he says with a wistful smile.

But, he says Harvard Square isn’t quite the haven for street art that it used to be.

“Years ago, it used to be more alive — more performers, more fun,” Maycott says. Today, Maycott feels that people are busier. “They don’t have the time to stop and talk,” he says. According to him, this is why many performers have left for greener pastures. A rock band used to play in Harvard Square’s “Pit” every Saturday — the sunken patio outside of the T station — but this is no

| PAGE DESIGNED BY

longer the case.

Still, several performers have chosen to stay in the Square. Maycott is one of many artists who make Brattle St. their stage.

Kyla G. Spears and her mother, Liveta F. Kanon, are a mother-daughter duo who have serenaded pedestrians on the streets for years, and they take their art seriously. “You care so much about what you are doing, and you want people to enjoy it,” Spears explains.

The pair originally started their tradition of street performing in Memphis, Tenn., but they have since become regulars at Harvard Square after moving to Cambridge during the pandemic. Spears and Kanon love sharing music from their hometown and feel that Cambridge residents have embraced their style. “Boston is super supportive if you have a talent,” Spears says, and her mother nods in agreement.

Spears and Kanon are not the only performers using music as a way to share their culture. Myriam Ortiz, inspired by her Puerto Rican roots, often performs Caribbean and Latin American folk music that is rich in political messages and holds historical significance. When we approach her, she is midway through a rendition of “Playa Girón,” a song by Cuban musician Silvio Rodríguez about the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Ortiz breaks away from her regular role as Chief of Community Engagement at Boston Public Schools to perform with her guitar in Harvard Square every weekend. For her, music is not just a hobby but a form of self-expression.

Ortiz wishes that people paid more attention to the arts. “Art can be incorporated as a tool for just about anything that we do,” she says, citing mental health and language development as examples.

Maycott similarly sees his art as a form of

XINYI C. ZHANG — CRIMSON DESIGNER

relaxation, and he enjoys refining his craft and producing new designs over the years. He gestures to a stand full of his framed paintings: dreamy, celestial compositions in which howling wolves and leaping orcas are backlit by a glowing moon. He has retained his distinct style over the years — when The Crimson interviewed him in 2013, he was already creating otherworldly landscapes.

William C. Hoo-Lee, a newcomer to the scene, started performing with his guitar in Harvard Square because he appreciates that street performance “creates culture that is free,” he says.

Though the performance scene has changed in the Square, Hoo-Lee has still managed to find a sense of belonging. He breaks into a smile when telling us stories about his memories with Violin Viv, another Harvard Square regular.

This sense of camaraderie encourages artists to return every week. When asked what ultimately makes performing worthwhile, all of the street performers had the same answer: spreading joy.

“I love the feeling of knowing that you’re interesting a kid for the first time in something, or making them enjoy something, just that cute feeling,” Ortiz says.

“It’s good to see a mother giving their daughter a dollar to show appreciation to someone else,” Hoo-Lee says, explaining that both performers and spectators share happiness with one another.

Some performers find it rewarding to have a positive impact on the lives of students. Spears shares that she enjoys talking to students moved by her performances, sending them well wishes on their bright futures.

Through their music, painting, and more, street performers bring Harvard Square to life.

“Ask them, and they might insist that theirs is not so much a political project as is a philosophical one. But this same insistence on deep questions has also informed a rising conservative political movement — the so-called “New Right” — which eschews traditional Republican party politics in favor of more philosophical, and often more radical, views.

A. DZIABA AND SAKETH SUNDAR

JULIA N. DO

Harvey C. Mansfield ’61, former Government professor and an advocate for classical political philosophy, says he has never taught a class on conservatism. “Conservative is a kind of political position, more than it is an intellectual one,” he says.

In the early 2010s, the Salient, Harvard’s conservative student publication, quietly fizzled out. Then, in November 2021, students across campus found copies of the paper dropped in front of their doors.

Boasting four American flags on its cover and the title “Revising America,” the issue began with an introduction to the revived publication: since the “collapse of the old Harvard Salient,” the editors wrote that Harvard’s campus had a “marked dearth, not only of conservative thought, but of political thought in general.”

That same year, the Institute of Politics saw the creation of its Conservative Coalition, a space for conservative discourse within Harvard’s predominantly progressive political space.

In the years since, as more and more copies of the Salient pile in front of students’ doors, conservative thought on campus has also flourished — even as the University has come under heightened scrutiny for its lack of academic freedom.

Membership in the Harvard Republican Club has risen significantly, attracting hundreds of new students over the past year. This year, the IOP launched a conservative mentorship program, pairing students with powerful conservative leaders, providing a direct link between campus and national political influence.

But beneath this fervor are campus conservatives who have been operating more quietly, trading discussions of electoral politics for philosophical discourse and reading classical texts. They are found in groups like the Salient, the John Adams Society, and the Abigail Adams Institute, concerned with revitalizing debate and the humanities at Harvard. But while some of these organizations are ostensibly non-partisan, the truth they are pursuing is often steeped in — and used to justify — traditional, conservative values.

They are “idealistic conservatives,” wrote Issac T. Jirak ’25 in a Salient article this April — the academic conservatives who lend their policy-focused “rural” or

“empirical” counterparts “the language and ideas they need to defend their political stance.”

Jirak claims that Harvard’s intellectual conservatives must “cure the decay of conservative values” in rural conservatives across the country who have gradually succumbed to “liberal ideology.”

Ask them, and they might insist that theirs is not so much a political project as is a philosophical one: rescuing the pursuit of deep truths and the Western canon from a University which has lost interest. Many said they shirked political labels or may not vote for former president Donald Trump, and they represent a range of policy positions.

But this same insistence on deep questions has also informed a rising conservative political movement — the so-called “New Right” — which eschews traditional Republican party politics in favor of more philosophical, and often more radical, views. Christopher F. Rufo — a leading conservative activist and Harvard antagonist — quotes Machiavelli; billionaire donor Peter Thiel was heavily influenced by obscure philosophers like Leo Strauss and René Girard and questions the very foundations of post-Enlightenment “progress”; and vice presidential nominee JD Vance, a mentee of Thiel’s, underwent his own philosophical transformation toward a Catholicismhued postliberalism.

And at Harvard, it’s hard to see these two developments as necessarily separate: Thiel spoke at a conference this February organized by the Salient and other conservative organizations on campus. Harvey C. Mansfield ’53, one of Strauss’s most prominent followers, taught generations of Harvard conservatives until his retirement in 2023. And though the students themselves may deny any involvement with overt activism, they are frequently channeled into roles at some of the country’s most influential conservative organizations.

“Most of my students are outside academia,” Mansfield says with a hint of pride in his voice. “As I used to like to say, they run Washington instead of running

Harvard.”

‘PHILOSOPHY IS IN DANGER AT HARVARD’

Sitting in a circle in sofas and armchairs in a book-filled office, 12 students and local professionals spend their Friday afternoon debating the meaning of ambition. There’s no dress code, but there may as well have been — not a single person is in jeans. One late-comer greets the room energetically before joining the circle, his “I love Jesus” socks peeking out above his loafers.

They are gathered at the Abigail Adams Institute, founded in 2014 to revive “traditional humanities education at Harvard.” Located one door down from the Harvard Catholic Center, the institute describes its mission as non-partisan, offering programming on classical texts and so-called “great ideas.”

The attendees at this week’s “Abby’s Coffeehouse” are clearly well-read in philosophy, casually referencing Plato and Girard in their debate of what is good. At first glance, the gathering appears like a typical Harvard book club. But the purpose of their weekly meetings — and the institute itself — extends beyond that.

The Abigail Adams Institute is founded on the belief that Harvard’s humanities education is lacking. Its director, Danilo Petranovich ’00, wrote last year that AAI seeks to protect the “special seclusion and separation from everyday affairs that once marked college years.”

The call for “seclusion” comes as many conservatives argue that universities like Harvard have become too intertwined with today’s progressive politics. The classroom, they say, should foster debate around foundational questions of virtue, human nature, and political life — topics that modern progressives are perhaps too afraid to tackle.

Conservative students “see the wisdom in the ancients, and the progressives are not so much interested in wisdom as in power and equality,” Mansfield argues.

As a result, students like Fred W. Larsen ’24, a former AAI fellow and student of Mansfield’s, say “philosophy is in danger at Harvard.”

Mansfield was deeply influenced by Leo Strauss, a 20th-century German American philosopher, who focused on reviving ancient philosophy as a counter to the relativism of modern political thought. While Strauss was not explicitly conservative, he argued that modern students should look for hidden wisdom in the writings of canonical thinkers like Aristotle and Plato.

It’s not an approach that’s available to just anybody. Only the “esoteric” reader, so to speak, can parse through the layers of irony and contradiction to locate the true teachings that Strauss says are at the hearts of foundational texts. Sparknotes and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy just don’t cut it.

“The real contradictions in a thinker like Plato lie deep beneath the surface,” one writer argues in a February 2022 Salient article. “The average student never gets that deep, because he spends all his time at the surface creating a strawman to knock down in class.”

But Harvard’s conservatives say they are up to the task.

“Trump has opened the gate through which we might enter history. So let the venturing conservative heed the advice of Strauss and define himself on the questions upon which the liberal cannot tolerate an answer,” a student using the pseudonym Ira Eldredge wrote in the Salient’s April 2024 issue.

“Strauss reminds us of the permanency of political problems and the eternal value of philosophies that has never changed throughout time,” Larsen echoes.

True philosophers, Strauss held, tackled such permanent problems for what they were, without regard for the political mores of the era — even at the risk of ostracization or exclusion. Nowadays, that might translate to eschewing progressive social norms or “woke” orthodoxy.

Many writers in the Salient adopt this approach themselves, pulling from the texts of ancient philosophers to defend their rejection of progressive politics, under pseudonyms taken from the likes of Hippocrates and Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius.

The “little bit of historical reminiscence,” as Mansfield puts it, is perhaps part of the

| PAGE DESIGNED BY

appeal.

David A. Vega ’24, who took Mansfield’s course on the history of modern political philosophy, stressed the sense of belonging to an intellectual lineage.

“Mansfield is attempting to kind of trace a strong historical lineage in the history of philosophical thought,” he says.

It is an intellectual tradition, one that stretches from the ancients to modern philosophers, allowing students to feel like they are participating in something larger than themselves: a narrative of Western thought that positions them as guardians of a certain kind of intellectual rigor.

But it also allows students to engage with ideas that sit, somewhat provocatively, outside the bounds of “normal” American political discourse: critiques of progress, of equal democracy, of liberalism.

In the Salient’s September issue, “Ira Eldredge” used Aristotle’s warning that democracy believes “those who are equal in any respect are equal in all respects” to argue that Harvard’s affirmative action, grade inflation, and DEI officers have destroyed the value of merit at the university.

Nowadays, that might translate to eschewing progressive social norms or “woke” orthodoxy.

And in May, a student donning the name “Publius,” the pseudonym used in the Federalist Papers, pointed to the “noble myths” of the Roman empire’s founding to criticize the idea of America as “a nation of immigrants.” They advocated instead for a national identity centered around the Founding Fathers’ vision of a “grand moral order, one inspired by the Christian faith”or “Johnny Appleseed’s plantings and George Washington’s tobacco fields.”

But while certain elements smell of conservative radicalism, the overall project, many said, remains essentially —

JULIA N. DO — CRIMSON DESIGNER

comfortably — nonpartisan.

“If there is a philosophy of Strauss, I would contend it’s really just philosophy itself, unending search for wisdom, truth,” Larsen says.

‘PURSUING THE TRUTH IN A MORE INTELLECTUAL WAY’

The pursuit of wisdom through big questions or debates implies the existence of a single truth — one that, as many of AAI’s events illustrate, often embodies socially conservative values that are parrotted in right-wing political spheres. As Abby L. Carr ’25, co-chair of the Harvard Conservative Coalition, explains, conservatism partly hinges “an appeal to a moral foundation,” namely the belief that “there is an absolute right and wrong.”

On Oct. 1, the AAI hosted its annual lecture, promoted by posters across Sever Hall that asked passers-by “Is marriage necessary?” and “Does our economy prevent family flourishing?” Taught by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, a University of Pennsylvania economist, the talk revolved around the need to increase America’s fertility rate. This, Fernández-Villaverde said, is “our top national priority.”

“The drop in marriage rates accounts for all the recent drop in fertility,” FernándezVillaverde argued. And, in addition to reaping financial benefits, he explained that married people are happier and healthier.

Near the end of the lecture, he pointed the captive listeners — mainly older white men — towards further reading, including a book titled, “Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization.” The book claims that Asian Americans, conservatives, faithful people, and “strivers” have defied antifamily messages of liberal elites.

In AAI and other organizations, many of the same people who study ancient philosophy also find truth in traditional views on family and gender roles. Mansfield, a longtime critic of feminism, has argued extensively that gender differences should dictate traditional roles within family and society. And this summer, the John Adams Society changed its slogan from “Harvard’s premier undergraduate debate

organization for political and moral philosophy” to the “premier organization for the reinvention of man.”

These discussions provide intellectual fuel to a movement that’s become known as “neopatriarchy”: a push for a return to certain patriarchal values without directly advocating that women leave the workforce or fully return to domestic roles.

Vance, considered a leader of this movement, has become infamous for his rhetoric about “childless cat ladies” in positions of cultural and political influence, implying that those who choose nontraditional paths, such as remaining unmarried, contribute to societal decay.

And while Mansfield made it clear that he will not be voting for Trump and has strong disdain for him, he has nevertheless praised Trump for his rhetoric around gender roles and using “manliness” to win elections.

Past AAI events have echoed these ideas from Mansfield and Vance about gender and family structure. Last year, AAI partnered with the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, an organization of “conservatives who are upholding America’s founding vision and the Western tradition,” to host a debate titled “Does Feminism Necessarily Undermine Family Life?” According to a poll of attendees, the winner was Erika Bachiochi, director of AAI’s Wollstonecraft Project, who argued that 19th century feminism was compatible with robust family life.

Other previous lectures include “ProLife Feminism Then and Now” and, featuring Mansfield, a panel titled “Are Men in Crisis?”

“The mix of the students that we get at Abigail Adams Institute does lean conservative,” Petranovich acknowledged. But, they “encourage all sorts of perspectives.”

Maura Cahill, director of communications and marketing at AAI, explains that the institute encourages “intellectual freedom and pursuing things that students might not get a chance to explore or they feel like maybe are underexplored in their classes at Harvard.” But the topics that AAI chooses to address and the events it provides are undergirded with a clear set of values, one that may

be left out of classrooms because of its conservatism.

One floor above the Abigail Adams Institute on Arrow St., the Human Flourishing Program tackles similar questions. The program seeks to combine empirical research and the humanities

The draw to the Western canon and Catholic morals often goes hand-inhand.

to understand what leads to human wellbeing, focusing on the “pathways” to flourishing of family, work, education, and religious community.

“There are moral complexities and real disagreements on controversial moral issues, on questions, say, of abortion in this country,”saysTylerJ.VanderWeele,director of the Human Flourishing Program. But, he argues, that people focus too much on disagreements and not enough on “where we agree,” noting virtues like courage, justice, generosity, and wisdom that are seen as moral across cultures.

He believes Harvard must provide an environment to “have these difficult conversations around what are often painful issues and questions on both sides.” HFP, he emphasizes, is composed of people on both sides of the political spectrum.

The conservative perspectives he sees as necessary to the pursuit of truth, however, range from studying the effect of decreasing religious service attendance on rising suicide rates to adding a “pro-life scholar of women’s health” to Harvard’s faculty. And, these views in practice led VanderWeele to sign an amicus curiae brief against legalizing gay marriage in 2015.

In response to criticism, he argues that conservatives would also say progressive views are harmful, such as their stance on abortion. “From the perspective of not all, but many conservatives, this is basically just allowing for what many view as the wrongful ending of innocent life —

effectively murder,” he says.

While both non-partisan, the Human Flourishing Program and AAI are grantees of the Foundation for Excellence in Higher Education, which “strengthens elite universities and forms the next generation of leaders” with an emphasis on human flourishing, truth-seeking, and free inquiry. Many of FEHE’s other grantees promote Catholic life, Christian intellectual tradition, and Western thought.

The draw to the Western canon and Catholic morals often goes hand-in-hand. After being raised Protestant, VanderWeele is now a practicing Catholic, something that has no doubt informed his controversial stances on abortion and gay rights. Several of the AAI fellows we talked to had converted to Catholicism during their time at Harvard and begun attending St. Paul’s Parish, the Catholic church neighboring AAI.

Conversions to Catholicism — among them, notably, Vance — have been noted as a trend in the conservative movement. Just as many in the New Right have sought wisdom from ancient philosophers, young men, reacting to a progressive world, find solace in the longstanding institution of the Catholic Church. In Western philosophers or Catholic teachings, the “truth” these conservatives find is a moral code that provides a solution to the failures of modern liberalism – at the university or nationwide – through the return to tradition.

Cahill explains that Catholicism “takes intellectual learning very seriously.”

“I think that’s very attractive to a lot of Harvard students who are pursuing the truth in a more intellectual way,” she says.

‘THE WORLD OUTSIDE LOOKS DIFFERENT’

Another aspiring great thinker who found Catholicism is William Long ’19, a former AAI fellow who converted during his time at Harvard and led Harvard Right to Life, a pro-life student organization.

After graduating, Long formed the Cicero Society in Washington D.C., a parliamentary debate society influenced by his time in the John Adams Society and AAI. Like both Harvard organizations,

the Cicero Society — which has become something of a meeting place for young New Right thinkers and operatives in D.C. — insists on being a home for those who want to continue the “Western intellectual tradition.”

And like John Adams, membership is application-only and decidedly exclusive.

Among the people we spoke to, all stressed nominally apolitical values of truth, intellectual exploration, and discussion. Several, like Mansfield, argued that what they do is not necessarily conservative, never mind Republican. Some declined to answer questions about their personal political ideology or who they are voting for, or, if they did answer, offered vague descriptions of pragmatism or differentiated between different types of conservatism.

Most avoided speaking on this subject altogether. Of the over 127 people we reached out to, just more than a dozen were willing to talk. All members of the Salient declined to speak, saying they would prefer to “use our own channels to promote our perspective.”

This distancing seems to fit into a broader trend of not wanting to publicly identifywithideologiesthatareincreasingly unpopular on a liberal campus. Since its revival in 2021, the Salient switched to using pseudonyms for most of its writers. This summer, John Adams Society redesigned its website to remove any identifying information about its members or leaders, and the Harvard Republican Club only lists one name publicly, that of its president, Michael Oved ’25.

Oved and other conservatives attribute this to a fear of “social isolation.”

“Some of them worry that in expressing their Republican views in a public forum, they’ll lose friends over it. And that may be true,” Oved says. “The misconception is that you can’t be a Republican and have friends at Harvard.”

This rhetoric echoes that of Vance as he describes his time at Yale Law School. “If you were a conservative student with conservative ideas, you were terrified to utter them — terrified of being socially ostracized,” Vance said in a 2021 speech.

Rick Perlstein, a historian and journalist of American conservatism,

| PAGE DESIGNED BY

notes that secrecy has long been a feature of conservative movements. “There’s always kind of this veil between what you can say publicly and what you have to keep hidden,” he says. “It suggests that they are expressing ideas that, if they attached their own names, would sound so outrageous that it would place their professional prospects at risk.”

A 2023 faculty survey by The Crimson found that only 2.5 percent of surveyed faculty identified as conservative, while a separate Crimson survey of the class of 2027 found 8.4 percent of surveyed students identified as conservatives. Small, insular debate and philosophy groups may be the only avenues to explore conservative ideas in a predominantly liberal environment.

Yet for this apparent aversion to backlash, these campus organizations

“A lot of Republican students kind of know that the world outside looks different than in Harvard.”

— Bridget K. Toomey ’22

and students are embedded in a much broader network for conservative students, supported by those outside Harvard with a vested interest in supporting the new generation of leaders.

“A lot of Republican students kind of know that the world outside looks different than in Harvard,” says Bridget K. Toomey ’22, former co-chair of the IOP Conservative Coalition. Many of these students, who often feel they must operate with caution on campus, enter a completely different environment in the professional world. “If you want to work in D.C., about 50 percent of Capitol Hill offices are Republican, very different than the environment in the IOP.”

When the Salient was revived in 2021, it was supported by a grant from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which aims to fill “the void left by modern higher

JULIA N. DO — CRIMSON DESIGNER

education” and is on the advisory board of Project 2025. On its most recent tax filing, the publication reported over $90,000 of income. In 2023, the AAI had a revenue of about $5.4 million, supported by grants and donations from alumni.

The AAI itself sponsors the David Network, a conservative conference across “elite institutions” that was founded by the brother of Jacob A. Cremers ’24, who orchestrated the Salient’s revival. The David Network’s conference last year boasted Mike Pence as its keynote speaker and provided networking opportunities with the National Review, the office of Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas), and federal judges.

Conservative students can also find mentors in faculty members or visiting fellows at the IOP. Toomey says that “because Harvard has the reputation of being such a liberal environment,” these faculty and fellows have been eager to support students. The newly launched conservative mentorship program at the IOP boasts two former governors and four former members of Congress.

As a result of these networks and support, many of those who distanced themselves from politics at Harvard have monumental roles in shaping them, shortly after graduation. Doing this, they follow a similar path to Vance, who moved from intellectual circles at Yale into the political spotlight, where his ideas are at center stage in current political discourse.

Mansfield’s former students include high-profile figures like U.S. Senator Tom B. Cotton ’99, a former Crimson Editorial editor, and political commentator Bill Kristol ’73, who now hold prominent roles in shaping conservative thought. Other Harvard alumni have become rising stars in the Republican party, namely Rep. Elise M. Stefanik ’06 — chair of the House Republican Conference — and 2024 Republican presidential candidate Vivek G. Ramaswamy ’07, who was described “as the candidate of the New Right.”

Current conservative students seem destined for similarly influential positions.

William N. Brown ’24, the Salient’s former Editor-in-Chief and a former John Adams Society chairman who gave a “Student Scholar Presentation” at AAI, is a fellow at Cooper and Kirk, a law firm which

sued a school board to restrict protections for trans students and defended a ballot initiative to ban same-sex marriage in California.

Benjamin R. Paris ’21, a current student at Harvard Law School, went from serving as chairman of the John Adams Society to working at the Heritage Foundation on a “pro-family and pro-work welfare system” and fighting “arbitrary” regulations. The Heritage Foundation is the organization behind Project 2025, a proposed presidential transition project if Trump wins in November that has been relentlessly attacked by Democrats.

And Tyler A. Dobbs ’16, founding chairman of the John Adams Society, served as a summer associate at Cooper and Kirk and a clerk for Judge James C. Ho of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, who’s been listed as a potential

Supreme Court nominee under Trump and who Vox once called the “edgelord of the federal judiciary.”

With the support of conservative mentors and a network of like-minded organizations, seemingly innocuous studies of philosophy and the classics translate into jobs in politics and law, where the conservative ideas whispered at Harvard are shouted wholeheartedly in policy briefs, on the presidential debate stage, and in the modern right-wing movement.

In 1960, Mansfield, then an assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, would spend Wednesdays driving to Palo Alto to attend a

reading group at Leo Strauss’s house. According to Mansfield, Strauss was the most intelligent man he ever met.

However, this wasn’t Mansfield’s first introduction to Strauss. His mentors during high school and graduate school impressed the thinker onto him, and the year that Mansfield graduated from Harvard College, Strauss released his book “Natural Right and History,” something Mansfield — raised a Democrat but “disgusted with liberal relativism” at the time — read voraciously.

Two years after attending Strauss’s reading group, Mansfield joined Harvard’s faculty. And while he taught a long list of influential students throughout his 60 year tenure, in the late 90s, Petranovich attended his courses. After graduating from Harvard and finishing graduate school, Petranovich then obtained his first job as a literary assistant to William F. Buckley Jr., the

BY ANNA A. KREMER AND AMANN S. MAHAJAN

At 9:31 p.m. on Tuesday, Oct. 15, a silent summons wound its way to 69 Harvard undergraduates.

“See you at / 9 o’clock post meridian / windsday the sixteenth,” the email read.

The meeting details followed a cryptic poem describing a “canine slice of the cosmos / rattling roundabout roof of our mouths,” and the email was signed off “in deep aeolic infinitude.”

This brand of gleeful absurdity typifies the Whistler’s Society, one of Harvard’s registered student organizations. Every Wednesday at 9 p.m., veterans and novices alike gather in Lowell House’s nine-man suite — home to the society’s founders — to hone their whistling skills.

Members drop into cushioned armchairs and sofas under the glow of a northern-lights projector before whistling along to recordings of “anything from Pitbull to Puccini,” according to founding member Tyler A. Heaton ’25. There’s no sheet music, nor specified harmonizations; rather, attendees simply whistle each piece to the best of their ability.

“It’s completely unmediated,” founding member Aidin R. Kamali ’25 says. “It is us and the music.”

Heaton, Kamali, Austin H. Guest ’25, Henry A. Ayanna ’26-27 ,and Milo R. G. Schwalbe ’25-26 created the society their freshman year. Their first meeting, held in Heaton, Kamali, and Ayanna’s room in Weld Hall after a brutal Boston blizzard, felt like “cosmic forces aligning,” according to

Heaton.

“For too long, whistling has been a maligned art form, underappreciated in comparison to other forms of music-making,” he says. “And so we figured it was high time to put our foot in the door.”

Since then, the group has grown to accommodate more whistlers. At the Oct. 16 meeting, around 20 people showed up, trickling in to Turkish singer-songwriter Selda Bağcan’s album “Türkülerimiz Vol. 5” as Heaton and Kamali finished vacuuming the room. Some of them had been members since the club’s inception, while others arrived for the very first time (occasionally at the behest of an enthusiastic blockmate). According to Guest, this level of turnout is fairly new.

“For too long, whistling has been a maligned art form.” — Tyler A. Heaton ’25

“This seems like the first year we’re really having these large-scale meetings,” he says. “The past years, it’s been maybe seven or eight people that come every time.”

About 10 minutes in, Heaton called the meeting to order with a whistle, leading the group in a series of warmup scales and rhythmic exercises set to the beat of a metronome.

“This is the point at which we move on to repertoire,” Heaton says, putting on the group’s signature tune — Dmitri

Shostakovich’s Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2. Next up was Édith Piaf’s “La Vie En Rose.” Technique tips were few and far between, but Heaton and Kamali advised members to cup their ears to better hear their own whistles, move their tongues to broaden their range, and avoid laughing by looking at the ground.

The club welcomes members of all skill levels. While some members are musical — Kamali plays the Irish tin whistle, and Heaton writes, records and produces music — experience with sight-singing or ear-training isn’t a prerequisite. The club also includes a “non-whistler’s branch,” headed by William R. Kissinger ’25, which aims to provide support for people who haven’t whistled before.

“I have no way of showing people how to whistle. I’ve been trying to whistle for years, and I’ve never figured it out,” Kissinger says.

Members work at their craft until they’re able to whistle along with the rest. Mohan A. Hathi ’26, who joined the club a few weeks ago, has made progress even within the span of a few sessions.

“I came in being able to whistle maybe one pitch,” he says. “Now I can do maybe three pitches.”

Eliza V. Kimball ’25, who began in the non-whistler’s branch, cited a similar experience.

“I practiced a fair amount walking down the street, and within two weeks, I was whistling pretty much with ease,” she says.

As they practice, whistlers often discover particular strengths — Kamali is a strong low whistler, while Schwalbe can hit the high notes. The society’s repertoire thus includes a melange of tastes and styles: A few

| 23

pieces, like Boney M’s “Rasputin,” are longstanding staples, while others are spur-of-the-moment suggestions. This week, members rose to their feet for ABBA’s “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme!”, dancing as they whistled. They then kicked their way through “Rasputin” and Michael Jackson’s “Thriller.”

According to Heaton, the group’s “big break” came in their sophomore year, when they performed as an “interact act” in Harvard’s annual Battle for Yardfest. There, they whistled “Mask Off” by Future, and Adam V. Aleksic ’23 — a linguistics content creator known as @etymologynerd on Instagram and former member of the society — performed a solo aria.

“He absolutely destroyed it,” Heaton says.

“I have no way of showing people how to whistle. I’ve been trying to whistle for years, and I’ve never figured it out.”

— William R. Kissinger ’25

The Whistler’s Society has since performed annually at Harvard’s Battle for Yardfest in Sanders Theater. Last year, they also whistled at Yardfest, the Kirkland House talent show, Lowell’s coffee house, a Harvard Expressions Dance Company performance, and an event for the Slavic Society.

Performances can sometimes be informal or even impromptu: During one whistling session, members had arrived at the Lowell dining hall with a speaker to whistle to the “Aquarium” movement of Camille Saint-Saens’s Carnival of the Animals, and mathematics professor Noam D. Elkies spontaneously accompanied them on the piano. The group also embarks on annual caroling expeditions through

Harvard dining halls.

Schwalbe noted that their performances, both improvised and planned, have generally been well received. While audience members may laugh at first, “eventually it turns into applause,” he says.

As the founders approach their final year of college, they’ve had to cultivate underclassman membership. Kamali noted that this year’s group has more sophomores, as well as some freshmen. While the seniors aren’t looking for a board of leaders — Heaton describes the group as a “fully decentralized society,” and notes that “there will be no Founders’ Council” after the current class graduates — they hope the organization will continue to thrive. (Kissinger noted that the non-whistler’s segment of the society maintains a strict hierarchy: “When life gives you lemons, you make a hierarchical club,” he says.)

“We have faith that it will be in good hands, and they’ll treat it the way that should be treated,” Kamali says. “And if it expands a bit, or if it keeps the same intimate vibe to it, we love that too.”

The Oct. 16 meeting came to a close with Peter, Paul and Mary’s “500 Miles,” a number they added this year. As they whistled, the members formed a circle and swayed with their arms around each other.

“It’s a tradition from Irish traditional music that we really wanted to adopt: having a departing tune for when the night comes to a close and everybody leaves,” Kamali says.

With that, the meeting was over, but a handful of people stayed behind, not quite ready to depart.

“One of the key lines [from ‘500 Miles’] that I think really touches all of us is, ‘They say you will know that I have gone, you will hear the whistle blow 500 miles,’ and I think that really just sums it up,” Kamali says. “All of us are here for max of four years (or five). Everybody comes and goes — all the whistlers come and go — but there is this one whistling spirit that has united us all, even if for that one moment at one time.” 24 | PAGE DESIGNED BY

XINYI C. ZHANG — CRIMSON DESIGNER

BY ALIA S. AL-WIR AND NEERAJA S. KUMAR CRIMSON STAFF WRITERS

At 10 years old on a family vacation, Rachel C. Kanter found herself rummaging through the house’s book collection. The world stopped as Kanter found the new love of her life: a Danielle Steel novel. What began as a romcomstyle meet-cute turned into a full on passion.

“It was a pretty steady — I was going to say descent, but really ascent into the romance genre,” she says.

Now, Kanter is taking her relationship with romance to the next level — opening Lovestruck Books, a bookstore in Harvard Square specializing in romance novels.

Lovestruck’s conception started with the loss of Darwin’s, a Cambridge coffee chain. Kanter loved Darwin’s back when she was a student at the Graduate School of Education. After moving back to Cambridge in 2023, she missed the cafe and recalls thinking to herself, “Somebody should really reopen Darwin’s. Maybe I should reopen

Darwin’s,” she says. “Maybe I should reopen it as a cafe, bookshop.”

Kanter hopes that Lovestruck Books will go beyond your typical bookstore and act as a greater gathering space in Harvard Square complete with a cafe, writing workshops, and social events. She has always sought out community with her reading experiences.

“Any city I’ve been in, I’ve always started a book club,” Kanter says. In these book clubs, she has always taken it upon herself to encourage her fellow members to read romance books, as a way to “bring some levity and to encourage people to read what they love.”

She also knows that finding books children enjoy can be a challenge. During her time as a teacher, she found romance novels to be a fun way to connect with her students and to push them to read in their spare time.

When it came to developing Lovestruck, Kanter was able to broaden her romance reading community. She saw the genre grow during the pandemic. “People were turning to books and to romance specifically for kind of an escape,” she says. “In romance, you have a guaranteed happy ending. I think people like that predictability and

that sort of security of knowing things are going to work out.”

This helps explain the nation-wide rise in indie bookstores specializing in selling romance novels. Kanter says bookstores like The Ripped Bodice were her inspiration. The shop has locations in Los Angeles and New York, reassuring her that romance bookstores are not a fleeting trend.

The process was “incredibly serendipitous.” The perfect storefront happened to be looking for tenants. The prospective cafe partner Kanter had found was “excited to come back to Cambridge.” And the romance genre continued to skyrocket in popularity. Just like in a romance novel, everything was falling into place.

But romance novels are not without their controversies. With regards to rising book bans around the country, Kanter says she does not believe in policing what her students read, despite some parents raising the alarm about students reading romance novels.

“I don’t see the harm in providing free access to material that is exciting and interesting to people,” she says. “I think it is so much more beneficial to give people access to the content they need

than harmful. And I think the real harm comes when we start to restrict, when we start to police what people are interested in.”

Kanter knows what it’s like to be a kid interested in romance novels.

“I mean you have 13 year olds reading Colleen Hoover books and, you know, is that appropriate?” she asks. “I don’t know, probably not. But also, who’s to say what’s appropriate? I, as a young child

myself, read stuff that was probably not appropriate, and that was really energizing, exciting.”

Even so, Kanter understands that the target audience for romance novels is between the ages of 16 and 45. She still hopes to give kids an entrée into romance, with a section for children at Lovestruck Books to keep them occupied while their guardians shop.

Speaking to Kanter, the joy she feels

about this new chapter is palpable. Romance has always been an “escape” for her, and now she is grateful to live out her happily ever after with her beloved books.

“It’s sort of hilarious that my life’s work is to spread smut,” she says. “But honestly, I’m going with it. It’s great. It’s really about spreading joy and building a sense of community, and a space to celebrate community.”

GRAPHICS BY JULIA N. DO — CRIMSON DESIGNER

BY KATE J. KAUFMAN CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Ilive in a double in the Inn on Mass Ave. My name is Patrick Boylston. I’m 19 years old. I believe in taking care of myself, in an imbalanced course schedule, and a rigorous coffee chat routine.

From the moment I wake up, I follow my carefully color-coded Google Calendar. Of course, due to my many commitments, I can’t help that the only times I have to finish my problem sets are during lectures, or that I only call my parents while I’m brushing my teeth at night.

As my commitments necessarily ramp up, it requires more fitness to balance everything. The trek to Northwest for my math class (14 minutes and 20 seconds) feels like a massive waste of time. Not to mention, the professor is teaching content that won’t be on next week’s midterm, so attending this lecture would do little good.

Although missing class has become a standard part of my routine, I wouldn’t call myself “behind.” My strategic avoidance is merely a tool for maximizing efficiency. Now I am become Optimization, the epitome of productivity, thanks only to my emotionally intimate relationship with a state-of-the-art “Samantha”:

The Panopto 2x speed function.

Why would I ever spend an hour and fifteen minutes sitting in a room in Northwest, when I could digest the same

content in 37.5 minutes from the comfort of my own dorm? Plus, I can bypass a dreadful 45 seconds of small talk with my classmates if I don’t go to the lecture hall. And whenever some silly attendee raises their hand — no doubt to ask a question that won’t appear on the exam — I can avoid the whole business by just hitting the right arrow once, twice, fifteen times.

As a matter of fact, I’ve become an expert at using the skip forward feature. No longer do I have to bear the weight of my own thoughts as I wait for a lecturer to organize their notes. And I don’t mind missing out on the comedic timing of my professor’s jokes. I haven’t scheduled any time for laughing. Humor is unproductive and should be abolished. Why would a professor waste my time being entertaining or engaging to listen to? At Harvard of all places!

With Panopto, I can filter out everything but the pure, sweet song of rapid mathematics spewing through space and time. I will never again need to interact with other humans at a biologically-limited pace.

Whenever I spot the backs of my classmates’ heads on my screen, I feel a justified surge of self-righteousness. How silly they are, how unoptimized, taking their tidy iPad notes and solving equations along with the professor. They don’t know Panopto the way I do — with her as my guide, I can merely scroll forward to see the solution and skip the pointless business of calculating!

Plus, unlike the archaic hominids I

OLIVIA W. ZHENG — CRIMSON DESIGNER

have for classmates, I’m not confined to learning from 9:00 to 10:15 am on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. Panopto is there

“With Panopto, I can filter out everything but the pure, sweet song of rapid mathematics.”

— Kate J. Kaufman ’27

whenever and wherever I need her. This is where my effectiveness really takes off. I can play two lectures at once. I can consume educational fodder while ingesting my typical 100 grams of raw protein powder or while completing my daily thousand stomach crunches. I can use split screen to learn linear algebra while working on articles for The Crimson — with no harm to writing quality whatsoever. Hell, Panopto can teach me matrix multiplication while I sleep.

My friends (the other students posting on Ed instead of going to office hours) are constantly asking me how I became the textbook definition of an academic weapon. I shrug. It’s an investment, measured in thousands of dining hall togo boxes, hundreds of dollars spent on electric scooters, and years of experience consuming high-speed video content. I’ve got the intellectual reflexes of a high-

performance athlete. This is necessary to my four-year plan, which is delineated in a minute-by-minute spreadsheet.

“I’ve got the intellectual reflexes of a high-performance athlete.”

— Kate J. Kaufman ’27

To become the ultimate Panopto lover,

I must maximize stimulant intake. It takes twice as much coffee to watch a lecture twice as fast. If I drink five cups with my breakfast, time becomes a dimension I can manipulate at will to keep up with a sixth class and five additional extracurriculars. Swallow an entire bottle of caffeine pills from CVS, and the only time I’ll need to dedicate to academics is a half hour before each exam to speed-read Panopto’s audio transcripts. The world falls away, and it’s just me and Panopto, reaching full human potential as one.

With my physical performance enhanced, Panopto gives me towering abilities. She empowers me to perfectly control and divide my attention among

unlimited responsibilities. Courses, extracurriculars, personal hygiene… Nothing is neglected when it operates under Panopt(icon)’s loving observation. What’s that? Ten percent of my math grade will be based on participation? Not to worry. I’ll just have to redesign my calendar to include reloading Poll Everywhere each morning. Perhaps I can slot it in at the same time I’m in Elon Musk’s X comments, begging him to acquire Panopto for Neuralink integration.

Once Panopto can transcend my cold gaze and project straight to my brain, you will shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours, but I simply won’t be there. I’ll be watching lectures.

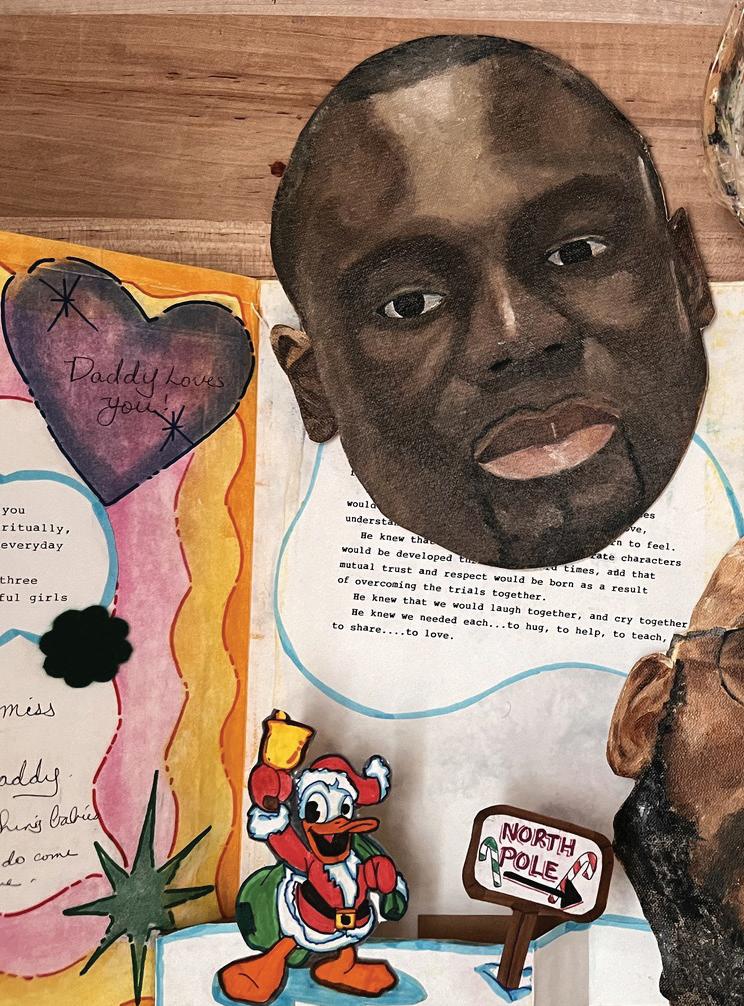

BY CIANA J. KING

CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

My sister used to always tell me she remembered seeing a gaggle of geese waddling outside the gates, or maybe they were ducks. If the memory of a seven-year-old serves us right, there was also a vending machine in the visitation room that sold these radioactive-looking bagged cheeseburgers and Powerade. For some reason, I’d always

associated prisons with chips. Either way, I don’t quite remember much.

Yet, for some reason, I can’t seem to stop thinking about them. About all that happens “in between.” All the “unseen” bits during the lost time or, time stolen, rather.

Some days it would take us over three hours on a train and a shuttle bus to get there. We’d spend a couple hours just waiting for all visitors to get patted down and screened, standing in a yard, in between these two huge doors that would slam shut — one closing off the “real world” behind us and the other opening up to a room

full of fathers, sons, brothers, husbands, and uncles, lined up in beige jumpsuits, awaiting our presence.

There’s something suffocating about holding spaces, their liminality. But, at least inside, Mami says, there were crayons and games for us.

I’ve never really thought about the abnormal parts of my childhood. Mami always did a good job of keeping us happy. I’d never felt a lack.

But there’s something different about college, when you’re confronted with all these different realities and alternative

familial dynamics. Suddenly, you’re realizing that not every little girl grew up thinking daddy worked far away or developed a fondness for a yellow canary named Tweety just because their father drew him once on a t-shirt.

Now, I’ve found myself writing a thesis about memories that don’t even quite feel

hubris, justified playing God?

At least with the Climate Clock in New York, I know it’s a countdown of when we’re all screwed. There’s this impending sense of collective doom, a generation of kids who’d been dealt shitty cards by the ones before it.

But no one tells you how to cope with a modern-day lynching.

and Black bodies enough to compensate for all those who don’t.

And so, even if I were to mourn this loss alone, I would do it as my duty. Because Marcellus is mine. Every Black man on my screen ends up belonging to me, becoming me — owner of my dreams and my nightmares.

“It’s odd having to humanize someone. I don’t know how to convince the rest of the world that he didn’t have to die.”

— Ciana J. King ’25

like my own.

I’ve tasked myself with understanding the intersections of hospital and prison architecture and their implications on the Black psyche. In other words, I’m trying to make sense of my family’s experiences.

Don’t be mistaken, though. This isn’t just another retelling of my own circumstances, per se, but rather about a grappling I’ve been left with — a fear I’ve developed as a result of lived experiences and exploitative news clips. The flattening of Black ontology solely into Black erasure.

For some reason, I can’t help but feel drawn to every other Black man in my father’s shoes. Not from a place of mourning or missing him, but out of curiosity and a complicated empathy.

As I ferociously typed out his name and clicked the first link available, a page on the Innocence Project, a countdown timer glowed ominously back at me. It read, “Time left until execution: 00 Days 00 Hours 00 Minutes 00 Seconds.”

Despite over nearly 1 million signatures to halt his execution, the state of Missouri allowed the murder of Khaliifah ibn Rayford Daniels, also known as Marcellus Williams.

How do I describe the realization that humans have rationalized their own

Nobody tells the little girl inside you that struggle, incarceration, and death are not fated for you and everyone you’ve let yourself love.

And, yes, of course, I know that. I’m not oblivious to the fact that I’m writing this from my Harvard dorm. But do I really?

“Beyond a reasonable doubt,” to me, is as tangible as the sun — you can catch its rays, feel its warmth on your skin, but, like Icarus, can never quite get close enough to touch it. And, for once, sitting at my computer in a dimly-lit studio, I understood that. I knew where I stood in the world.

In my little chrysalis, time stood still, while everyone else’s day just kept going.

Would you believe me if I told you why, some days, I don’t want children? Would you laugh if I told you why I panic when my boyfriend or my sister doesn’t answer my messages? Would it be wrong to tell you how tiring Black love is when Black loss is the prophecy the media has played out for me?

The part people forget is that he, too, had a little kid who might have grown up remembering the ducks, the burgers, and the crayons. Perhaps his son also got hand drawn sketches of his baby photos or shirts covered in cartoon drawings, so big they could fit like nightgowns.

It’s odd having to humanize someone. I don’t know how to convince the rest of the world that he didn’t have to die. Call it dramatic, but it’s exhausting growing up feeling the weight of loving Black beings

Whether I like it or not, we’re all still tethered together. And each person I learn to love, I can’t help but anticipate their loss. Time, for me, is borrowed. If not borrowed, stolen, owned by this other entity that isn’t me.

***

Yet, to that, I say, oh well.

To that I say, what’s mine will always belong to me. I mean, what fun would it be conceding? Settling for survival? Falling for an image of my reality that’s been painted by them and not us?

For me, to choose stolen smiles, borrowed memories, and potentially ill-fated love is to participate in the reclamation of Black ontology. To choose to love my Blackness and indiscriminately pursue Black love is to choose my liberation.

As Williams wrote,

“there is so much beauty and comfort in being in love and just being… – amidst sounds of buzzing chirps crickets

the pleasant but irregular blowing of the wind

fireflies dancing in step with the light of the moon

how strange it is to become aware of another’s heartbeat but forget one’s own –finally love.”