MARCH 2022

MARCH 2022

FM CHAIRS

Maliya V. Ellis ‘24

Sophia S. Liang ‘23

EDITORS-AT-LARGE

Josie F. Abugov ’23

Kevin Lin ’23

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Rebecca E.J. Cadenhead ’24

Sarah W. Faber ’24

Saima S. Iqbal ’23

Tess C. Kelley ’23

Akila V. Muthukumar ’23

Maya M. F. Wilson ’24

WRITERS

Tamar Sarig ‘ 23 Amber H. Levis ‘ 25

Benjy B. Wall-Feng ‘ 25

Mila G. Barry ‘ 25 Francesca J. Barr ‘22

Saba Mehrzad ‘ 25 Sam E. Weil ‘25

Michal Goldstein ‘25 Kaitlyn Tsai ‘25

Peter L. Laskin ‘23

FM DESIGN EXECS

Max H. Schermer ’24

Michael Hu ‘25

Sophia Salamanca ‘25

FM PHOTO EXEC

Joey Huang ‘24

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Caroline Allen ‘24

Francesca J. Barr ‘22

Christopher Hidalgo ‘25

Josie W. Chen ‘24

DESIGNERS

Keren Tran ‘23

PRESIDENT

Raquel Coronell Uribe ‘23

MANAGING EDITOR

Jasper G. Goodman ‘23

BUSINESS MANAGER

Amy X. Zhou ‘23

COVER DESIGN:

Yao Yin ‘23

Dear reader,

FM is back, and we’re glossier than ever. And just in time, too – spring break is right around the corner, and we know you’re looking for a beach read. Tuck us in your suitcase, break us out on the plane, pass us around to all your relatives.

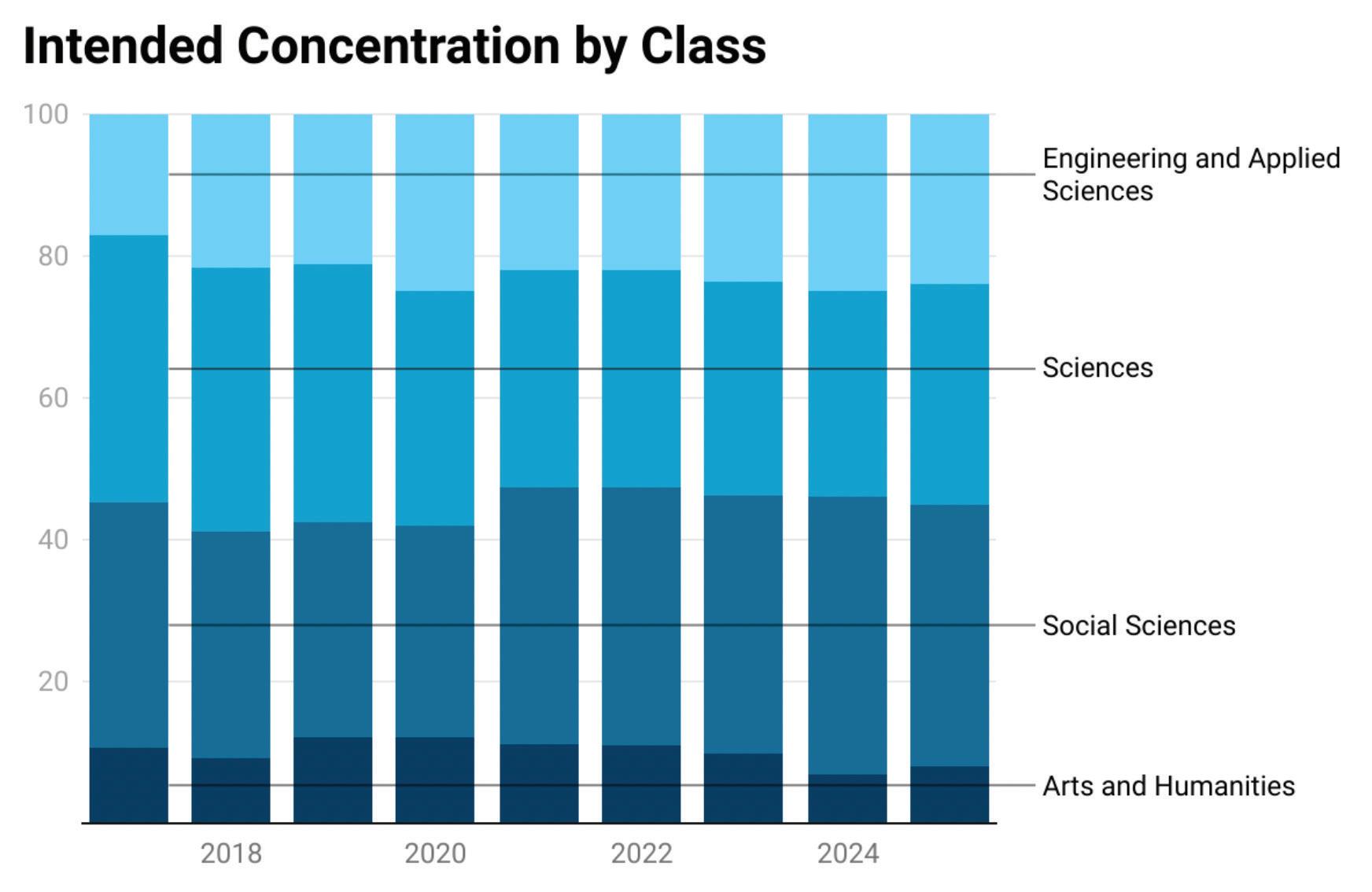

MG and KT ground our issue with a thoughtful scrutiny about humanities concentrations and the “battle of the university” at Harvard. There’s been a marked decline in humanities concentrators since around 2008, though the number has stabilized in recent years. The humanities are often seen as frivolous or unemployable, and yet, many claim that the world’s most pressing issues require precisely the type of interdisciplinary cooperation that such a devaluation of the humanities prevents. In the face of such cultural biases, what might a path to true interdisciplinary conversations look like?

The rest of our issue has something for everyone. SEW profiles Harvard senior Emma E. Choi, who went from an intern on “Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!” to NPR’s youngest podcast host ever with her comedy-news show “Everyone & Their Mom.” SM talks to our favorite dining hall swiper about his recent transfer to Dunster – much to our relief, you can take John out of Annenberg, but you can’t take the Berg out of John. FJB belts out her angst to live renditions of nostalgic punk hits at Emo Night Karaoke in Central. BBWF uncovers the ugly (in many senses of the word) history of the Smith Campus Center and the efforts to conserve the sun-damaged Rothko murals that once hung from its walls. MGB breathes new life into the brief, wondrous, eclectic musical group that was the Cambridge Harmonica Orchestra. For a little levity, AHL takes us on an MTV-style tour of some overachievers’ (masochists?) home away from home: Lamont Library. Finally, TS rounds out our issue with a stunning endpaper about her complicated relationship with food and cooking — sometimes a source of joy, but often a source of anxiety and disappointment.

Thank you to all of our execs, and especially to our EALs, KL and JFA, for scrupulous editing and endless patience, and to JGG for proofing into the wee hours. Of course, thank you to our amazing multimedia and design team, headed by MHS, SS, MH, PCZ, and JH — you bring our writing to life, and we’re thrilled to be producing this magazine with you.

And thanks to you, dear reader, for reading! If you’ve made it this far, pat yourself on the back. But don’t leave yet — you’ve only just begun. Seriously, this is page 1. Welcome to Volume XXXIII.

Sincerely, MVE

& SSLEmma E. Choi ’22 has had a whirlwind trajectory from an intern on the NPR podcast “Wait Wait ... Don’t Tell Me” to the host of their new, youth-oriented offshoot “Everyone & Their Mom.” She credits this success partly to her diligence and social media savvy, but most of all to the PowerPoints she meticulously constructed during the internship.

“I was doing a ton of unhinged guest PowerPoints which were like 25 percent about the guest, 75 percent about any other thing,” Choi laughs. In an attempt to liven up the podcast teams’ long Wednesday meetings, during her presentations Choi would make fun of her bosses, rank “all the guests we’ve had on by how much I wanted to kiss them on the mouth,” offer updates on her boyfriend, and share harrowing experiences such as her recent prolonged eye contact with a rat. “Apparently, no one’s done that before,” she adds between sips of chai. Choi’s team found her enthusiasm infectious — so when they began planning to expand to younger generations, they looked to their resident energetic young person for advice.

Even after reading the credits for the first discarded pilot and co-hosting a handful more unused pilots, Choi had no expectation that she’d become host. In fact, she recounts that her supervising producer took her aside and told her candidly, “Emma, I don’t think we can hire you. You’re a college student. We’ve never done that before. We just want to see what it’s like.” But to her surprise, she landed the gig.

“It took a while to sink in. It still hasn’t really sunk in,” she says. “I bill 20 hours, but I think about it all the time, so I’m kind of always on the clock.” Each week for the past few months, Choi has written jokes about a story of her choice, interviewed a guest, attended daily meetings scheduled around her classes, and shot retakes. The final product is weekly 15-minute-long

episodes airing each Wednesday that, as Choi describes, bounce “between sketch comedy and variety and stand up and interview format.” The first episode aired on February 23.

Before becoming host, Choi spent her early years at Harvard developing her comedic style and found a home in the improv group Immediate Gratification Players. She describes comedy at Harvard as if describing a family member — fondly, but critically.

Harvard’s comedy scene is “one of the most amazing creative communities on campus right now,” but also a “double-edged sword,” she says.

“It’s kind of cutthroat. People are always driving really hard, because they’re so focused on doing the damn thing,” she says. “But at the same time, it means that people are really bought in and are really dedicated to making things.”

Beyond her comedy pursuits, Choi is equally dedicated to fiction writing. “It’s interesting, because

I do really stupid comedy, but I write like, very serious fiction,” she says. She wrote her first play in third grade and continued throughout her academic career, the subject matter ranging from a “school shooting nightmare play” to “one about two Jewish boys trying to be rappers.” She

She describes her working style as obsessive. “There was a month where I was writing for 14 hours a day, and just like, barfing it out. Yeah, it wasn’t good, but it happened,” Choi says. Her writing helped her process a difficult breakup as well as the intensity of early pandemic life.

Regardless of the type of writing, Choi finds inspiration in playing around with words. In the first episode of her show, she cracks a “bananasmashing” joke about the Marvin Gaye impersonator hired by a British zoo to serenade endangered Barbary macaque monkeys. “I like experimenting with language, using stuff you would never expect, just like jumbling shit up, which I think makes good comedy. Because wordbased humor is never going to hurt anybody, you know?”

also founded a comedy magazine in her sophomore year of high school.

During the pandemic, she wrote a 400 page book spanning three generations of Korean women, “exploring how we carry folklore and trauma in our bloodlines.”

In the second episode, Choi discusses her grandmother’s inability to make kimchi, interviewing acclaimed chef Roy Choi to give her grandma some tips. She’s grateful that she can bring her family and her culture into the show — an aspect of her identity that she’s delved

into as she’s taken more classes on Korean history and art at Harvard. “College is the first time where I became proud of being Korean, which is a lot of what the podcast is now,” she says. “It’s not necessarily trying to be Korean. It’s just not backing away when that comes, you know, not trying to hide that in any way.”

Choi’s bold approach to comedy seeps into every aspect of the podcast. Her upbeat tidbits in each segment make her seem like the kind of friend you’d text immediately after embarrassing yourself in front of strangers, or when you’re deep into a long night of psetting and need a laugh. As for what she wants to make sure listeners take away from the podcast, she’s not quite sure. “I’ve spent a lot of hours hearing people talk about my brand, or my image, which is very strange,” she says.

“I’m not going to be like, I hope people really understand me from the podcast because of course they won’t, but I just want people to have a good time. And laugh and be like, Oh, that was weird.” She adds: “I just want people to walk to class, have 15 minutes of pure fun and be like, I can’t wait for next week.”

Many students consider 9 a.m. classes too early. But John S. Martin, longtime Harvard University Dining Services worker, wakes up at 4 a.m, drives from Tewksbury, Mass., to Annenberg — Harvard’s freshman dining hall — and starts work at 6 a.m.

Despite his early mornings, freshmen say Martin — better known as “John from Annenberg” — always has a smile for groggy students as he swipes their IDs. He remembers their names, befriends them, asks them how they are doing, jokes with them, talks sports, and makes a bustling dining hall more comfortable. He’s become something of a fixture in ’Berg.

Joseph A. Fahn ’25 says that on days he feels too tired to get breakfast, Martin is “a friendly face.”

“John [creates] a really welcoming environment, especially to freshmen going into their first dining hall,” Fahn says.

After 12 years at Annenberg, however, Martin has now moved to Dunster House to work in General Service.

First-year students were saddened to hear about Martin’s departure. “[He’s] a piece of Annenberg that’s not there anymore,” Gavin M. Lindsey ’25 says.

For Martin, this is a bittersweet moment. Though he says he “would love to stay at Annenberg,” his hours at the Dunster dining hall are more conducive to work-life balance. At Annenberg, Martin worked

on Sundays and Mondays from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m. and Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays from 11:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. At Dunster, he now works Monday through Friday from 6 a.m. to 3 p.m.

“Now, as my kids are getting older, it’s tough because I feel like I’m missing out on their activities, being home with my wife, and having dinner every night,” Martin says. “So I just applied for the job, and now it’s great because [I have] more family time.”

Martin lives with his wife Erin, 11-year-old daughter Kayleigh, and nine-year-old son Jack. Jack swims and bowls in a sports program. His children also play basketball together in a Buddy Basketball program, where Kayleigh is a volunteer and helps Jack and other children play. Martin

“I try to think, ‘How would you want your kids to be treated?’”

says he’s now more “available” as a husband and a parent and doesn’t have to cram all his family time in his day off because of this schedule change.

“It would really eat me away when I had to be working at Annenberg till 8:30 at night,” he says. “I come home and everybody’s sleeping. It wasn’t a good feeling after doing it for so long.”

Now that Martin has moved to Dunster, he has more time on the weekends to spend with

his children. He is an assistant basketball coach for his daughter Kayleigh’s basketball team, and he can now attend every game. “I’m really excited about that,” Martin says.

Martin considers his children whenever he interacts with students. “I try to think, ‘How would you want your kids to be treated?’” he says. “But I also enjoy it. I don’t just do it because this is my job. I’m doing it because I truly enjoy getting to meet you and your fellow classmates.”

Although freshmen will miss Martin, his good spirits and genuine interest in creating personal connections with students will be remembered for years to come.

Vincent D. Kafer ’25 hopes to see Martin more often next year. “Seeing him go to Dunster makes me hope that I get put in Dunster on housing day,” he says.

All it takes is enough courage (liquid or otherwise), and you too can be the lead singer of a raging rock band. At least, that was the case on Friday at Cambridge’s own Middle East Club in Central Square. Just down the stairs off Brookline Street, beyond the crowd of Uber arrivals and doe-eyed smokers, a determined group of ticketed patrons waited in line to add their names to the lineup. With a 75-song setlist of the 2000s’ best punk hits, this was not your mother’s karaoke night.

This is Emo Night Karaoke, the traveling concert that supplies live instrumentals for a “total nightlife experience” in cities throughout the East Coast. The core concept is one shared by karaoke bars everywhere: for each song, a new vocalist is pulled from the crowd and given three minutes of fame

on stage. But somewhere between the professional musicians and the 450-person audience, Boston’s ENK felt far more like a collaborative tribute concert than another session of sitting through every millennial’s rendition of “Mr. Brightside” by The Killers.

For the uninitiated, emo rock is something of a living artifact of the 1980s. The genre is often traced back to music’s Revolution Summer in Washington, D.C. In this heat of 1985, the band Rites Of Spring deviated from the aggressive themes that were central to the hardcore punk scene. They left behind the political messaging of punk lyrics to get into the personal, creating music as rich in feeling as it was in sound. It was all about love and loss, heartbreak and angst.

As other groups followed suit, the name “emo”

FRANCESCAAt Emo Karaoke Night, any patron can go on stage to sing a song from a playlist of emo-rock classics by artists like My Chemical Romance, Paramore, and blink-18. Photo by Francesca J. Barr.

emerged to describe the phenomenon. It’s thought to come from the longhand “emocore,” a marriage of emotional and hardcore, to differentiate the subgenre from mainstream rock. But this idea of emocore wasn’t loved by all. In Rites of Spring producer Ian Mackaye’s own words, emocore was “the stupidest fucking thing I’ve heard in my entire life.” From there began a long history of mystery and scorn around the emo name.

But ENK doesn’t seem to have any stake in the debate of what is or isn’t emo. In fact, their setlist is far more interested in tracks that people want to sing than the limits of any genre.

The karaoke project began in 2018 when drummer John J. Damiano called up old bandmate and guitarist Chris D. Pennings. The two were brainstorming the next steps for Damiano’s poppunk tribute band, “Tickle Me Emo,” trying to figure out where he could find a new lead singer.

It was Pennings who first imagined the unconventional solution. He had just come off a family cruise, the highlight of which was performing a blink-182 song for the ship’s karaoke night. To emulate that rush, Pennings and Damiano thought that the audience itself could be the lead singer for

their band. Thus, ENK was born.

It took a few months for Pennings and Damiano to figure out how to pull it off — they needed a venue, a sign-up system, and a way to display lyrics to the singer. Despite each logistical challenge, by 2019 it became clear that the ENK project might just stick.

Once you enter the sea of Truly and Bud Light cans in the basement of The Middle East, the appeal of ENK becomes clear. Drawn from the 2000s hits of My Chemical Romance, Paramore, and blink-182, the ENK setlist perfectly reflects what its mesh-clad patrons want. As soon as each song was announced, screams of excitement interrupted the nondescript pop that played between acts.

The whole night reflected the nostalgic intensity of emo rock, from the neon glow off of the old black band tees to the impassioned cries of drunken millennials.

In the hangover after the Cambridge show, the ENK band packed up their gear to head down to Philadelphia for another sold-out crowd. Come Monday, the guys will return to their professional jobs for a week of work. They’ll rest and rinse out the angst of the past weekend’s show before repeating the cycle all over again on Friday.

Throughout high school, Jessica Lao ’23 was set on studying English. Her love of literature dates back to her childhood, when her mother would bring her books from the library: children’s versions of classics like “Pride and Prejudice.”

But when she began college, Lao started doubting whether she should follow this path.

“In the last 20 years or so, there’s been a push that we all need to go to college — it’s how you get social mobility, get a job,” she explains. “I think that with the mindset of ‘we have to go for practical reasons,’ it seems a little ludicrous for us all to go study something really obscure in the humanities and flip through archives. The reason why we all push each other to do finance, consulting clubs, CS and that sort of thing, and the reason we think it’s too ‘indulgent’ to study the humanities is probably because of this wider transformation.”

Indeed, Lao isn’t the only one who has felt these pressures to conform to more “practical” pursuits. In 2008, 236 Harvard students were concentrating in English. That number steadily declined over the next decade, and fell to 54 students in the 2019-20 academic cycle. Meanwhile, the number of Computer Science concentrators rose tremendously, from 86 students in 2008 to 180 in 2019, and it is currently the second most popular concentration at Harvard.

Lao’s story represents a symptom of a problem that has vexed universities in recent decades: the supposed downfall of the humanities, signaled by

the decline of undergraduate humanities majors.

In the early 2010s, a wave of coverage detailing this “crisis” swept through American universities. Multiple colleges reported concern for their humanities departments as students’ interests switched over to the sciences, worrying that the humanities would lose necessary funding and that students would miss out on the essential critical thinking skills that are useful for work in all fields. At Harvard, a 2013 article in The Crimson stated that the College had seen a stark decline in humanities concentrators; according to the piece, the number of incoming freshmen who intended to pursue humanities concentrations had fallen 9 percentage points in the previous decade.

Since then, debate around the future of the humanities has died down, as the number of humanities concentrators has stabilized. According to collated data from previous surveys conducted by The Crimson, the number of freshmen intending to concentrate in the humanities has leveled off at around 10 percent of each Harvard class over the last decade.

But this proportion is much lower than it used to be. In the 2019-2020 academic cycle, 13.5 percent of students graduated with a degree in the arts and humanities. By contrast, in the 2010-2011 academic cycle, 21.1 percent of the total class pursued arts and humanities concentrations. This year, the Crimson freshman survey found that only 7.1 percent of the class of 2025 reported an anticipated concentration in the humanities, while 33 percent of the class in-

tended to pursue the social sciences and 49.1 percent intended to pursue the sciences or engineering and applied sciences.

In a 2013 editorial, The Crimson correlated the decline of humanities concentrators to an increase in STEM concentrators, refusing to “rue a development that has advances in things like medicine, and environmental sustainability as its natural consequence.”

The vast disparity between the number of humanities concentrators and social science or STEM concentrators remains indicative of — and risks entrenching — a larger problem: a view of the humanities as notably separate from, and inferior to, these other fields.

“Why spend four years listening to lecturers warn you that you can never really know anything?” the Editorial Board wrote. “To those who are upset with

the trend, we say: Let them eat code.”

Cultural perceptions of field divisions have siloed people into thinking of sciences and humanities fields as a zero-sum game, leading them to believe they need to “save” the humanities or that the humanities are “dead.”

This perceived binary between the sciences and the humanities continues to have real consequences: it can leave students feeling locked out of the fields they love. Lao, whose decision to concentrate in Economics was motivated by financial factors, tried to keep up her long standing interests by trying to join an arts organization. But after being rejected twice, she says she began to doubt her abilities to pursue the arts.

“In my mind, I realized that my parents are right; I’m better at being a corporate cog,” she says with a halfhearted laugh, fidgeting with the sleeves of her sweater. “Maybe I personally wasn’t strong enough to keep going on this path.”

Lao’s internal doubts stemmed from external pressures.

“Before I went to college, there were family friends and relatives of mine who kept making fun of my parents because they thought I was going to study English,” she says. “My parents both did [economics], and they were understandably anxious about me studying something with what they assumed to be very low job prospects.”

Lao’s anxieties only deepened when she saw many of her peers join pre-professional groups, she says. Ultimately, these factors swayed her to concentrate in Economics instead, consigning English to a secondary field

Now a junior, Lao still grapples with conflicting feelings about her decision to pursue Economics. While she currently feels content with her field of study, she recalls reading her admissions file and feeling like she “scammed” the admissions officer, who

This year, the Crimson freshman survey found that only 7.1 percent of the class of 2025 reported an anticipated concentration in the humanities.Jessica Lao ‘23 entered college intending to study English, but she is now pursuing a more “practical” Economics concentration instead. Photo courtesy of Jessica Lao.

seemed excited about Lao’s interests in literature and convinced that she would pursue it at Harvard.

Lao is not the only student who has had concerns over the lack of potential job prospects within humanities careers.

The 2008 financial crisis seems to have been a catalyst for this fear of the humanities in terms of financial security; the data for the decline of students pursuing humanities degrees and the rise of those in STEM over the past decade lines up with the crisis’s economic aftermath.

Yet, it turns out that the perception of the humanities as less employable post-graduation is overstated. In fact, the choice between pursuing a humanities or STEM major bears little indication on a person’s job prospects. A 2018 study by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences found that the unemployment rate among holders of a terminal bachelor’s degree in the humanities was 3.6

percent, while that of those with a terminal bachelor’s degree in engineering was 3.1 percent and, for those in the physical sciences, 3.4 percent. The differences are not as stark as fearful students make them out to be.

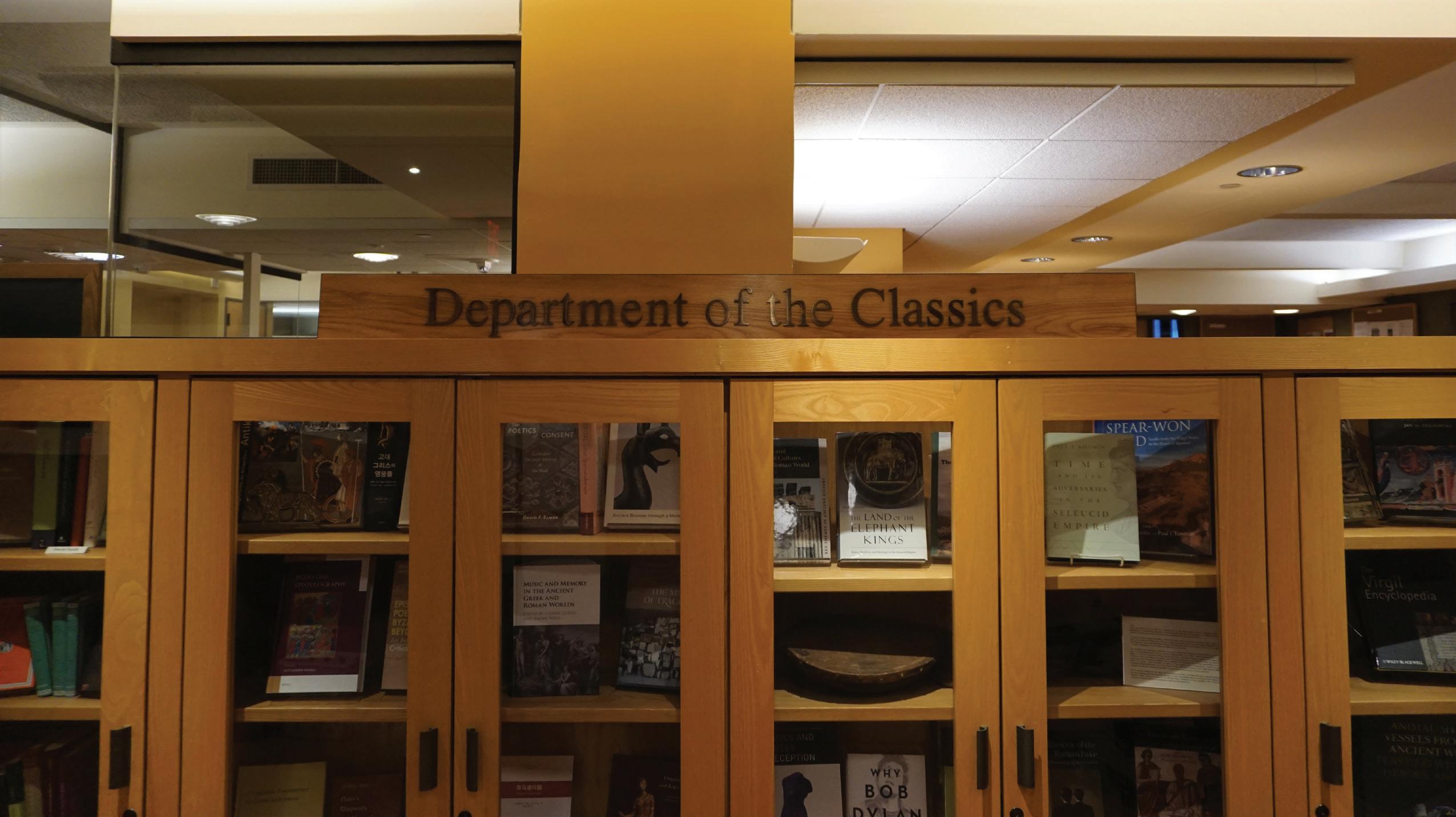

Still, when Justin G. Han ’24 entered college, he “very quickly got worried” that he wouldn’t be able to “find a career with only Classics.” Instead, his Classics and Applied Math joint concentration is a chance to pursue a humanities field that he loves alongside a field he believes could provide more post-graduate job security.

The belief that the humanities have less industrial value tends to put the humanities on the defensive. But often, this defense backs the humanities into a corner; in the current cultural trend that prioritizes and only values fields for their practicality, humanities scholars must justify their pursuits in terms of their material utility. Such rationalization for the humanities plays out in ar-

guments that aren’t necessarily helpful or complete, such as the idea that the humanities are solely valuable within the realm of ethics. Tara K. Menon, an assistant professor in the English department, refutes this argument.

“Sometimes this debate plays out in terms of ‘Oh, the humanities make you a better person,’” Menon says, rebutting the idea that “you read a book and that makes you more sensitive or sympathetic to other people.”

Instead, she argues that the humanities are important because “they are tools for thinking with.”

According to Menon, global citizens should be “ready to engage with ideas and think better with them.” She continues, “I think that is not only a skill — I don’t love the language of skills that is deployed and has been a consequence of STEM winning the battle of the university — but that this is an essential quality for being a human in the world.”

This “battle of the university” is something that Julie Heng ’24 has paid particular attention to. From an early age, Heng, a Crimson Editorial editor, was frustrated by the idea of the humanities- or STEM-oriented brain as innate.

“I can remember, for a really long time, questioning the specialization of fields, starting from probably middle and high school when people say that, ‘Oh, well, I’d rather do hours of math instead of an essay’ or vice versa,” she says.

As Heng describes, students often view their concentration choice as a de facto personality test — as something that reflects an inborn capability.

Even the differences between physical spaces on Harvard’s campus are representative of this perceived division. While humanities concentrators find repose in the Barker Center, with its red-brick walls and cozy classrooms, often decorated by art prints and book-

shelves, STEM students have taken ownership of the recently-built $1 billion Science and Engineering Complex in Allston. The SEC commands attention, its sustainable design and angular exterior illustrating its aura of innovation and modernity. Cabot Science Library, located within the Science Center, captures the same aesthetic themes: sleek, bright, new. Meanwhile, Lamont Library houses the Woodberry Poetry Room and Farnsworth Room, low-light spaces filled with books and homey lounge chairs.

According to Joyce E. Chaplin, Professor of Early American History, the division of the fields primarily dates back to the 19th century — as knowledge in various fields deepened, one had to specialize in a particular discipline in order to claim expertise in it.

“To claim in the 16th century you understood mechanical philosophy, which we now regard as an ancestor of physics, is a different proposition from being able to do research in physics now and to claim a part of it in your area of

specialization,” Chaplin explains. “We have a kind of investment in claiming that specialization is the way we understand the world, and that there is validity to this.” This specialization, she adds, can cut disciplines off from each other, making interdisciplinary collaboration difficult.

Exacerbating the issues with specialization, however, is a broader problem with the way society values different fields. When people feel pressured to choose between disciplines, they may opt for a field in the sciences due to the aforementioned anxiety about job prospects.

For Jane X. Chen ’12, the realization of this devaluation caused her to shift her career trajectory. Though Chen concentrated in History, she decided to enter the world of finance after graduation. Quickly feeling unfulfilled by her career — a field she says wasn’t “a true reflection of [her] values and what [she] wanted to contribute to society” — she spent time after hours volunteering as a writing tutor for immigrant students

The “Battle of the University”Tara K. Menon, assistant professor of English, uses computational methods to study 19th-century novels. Photo courtesy of Lauren Crothers.

in Queens. For the seniors she helped with college essays, Chen realized that the problems with their writing couldn’t be immediately fixed; it was “way too late in the game,” and the issues should have been “dealt with 10 years prior,” she says.

In response, she quit her job in finance and founded the Eyre Writing Center to teach writing skills to elementary schoolers through her own curriculum. To her, the EWC is about “democratizing access to writing,” trying to combat what she sees as a lack of accessible resources in comparison to STEM fields.

“I think there are just a ton of STEM resources out there to get really passionate,” she says, emphasizing that it’s possible to teach STEM subjects in the format of video learning or online quizzes. By contrast, Chen believes that these resources do not adapt as well to something as “personal and high-touch as writing.”

Making the humanities more accessible is imperative for exploring its intersections with other fields. In an op-ed for The Crimson, Heng, who studies Inte-

grative Biology with a secondary in Philosophy, describes a number of modern problems that require solutions which connect the sciences and humanities. At the end of her piece, she shifts focus to the way this issue can be addressed at Harvard in a space she calls a “Third Enlightenment Salon.” The name and concept reference 17th century salon gatherings — popularized in France throughout the Enlightenment era and giving way to the Scientific Revolution — where everyday citizens interested in philosophy and religion could freely discuss their ideas.

Heng writes: “According to Anthony Gottlieb’s ‘The Dream of Enlightenment,’ two Enlightenments — bursts of creativity — have fundamentally shaped Western philosophy: the First Enlightenment in the sixth century B.C. birthed the humanities; the Second in the 17th century grew the sciences.” She argues that society today needs a “Third Enlightenment to harmonize the two.”

Heng has brought that Third Enlightenment Salon to life, founding the Harvard Undergraduate Salon for the Sciences and

Humanities along with Chinmay M. Deshpande ’24 and Henry N. Haimo ’24. This past Valentine’s Day, the Salon met for the first time in Memorial Hall 303 above Annenberg.

The Salon hopes to correct the hyper-specialization of fields by providing a space for interdisciplinary discussion. According to Haimo, the Salon’s goal is to “find people who are actively reaching across the academic aisle.”

“What are the unique values that the sciences and humanities bring?” Heng asks. “And how can we put them in conversation together to solve big questions?”

With its plain, cream-colored facade, 42 Kirkland St. looks like an ordinary triple-decker at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. On a regular stroll past the building, it’s easy to miss the three small windows perched along its rooftop, indicators of a fourth floor: the metaLAB.

Founded in January 2011 by Jeffrey T. Schnapp, a professor in the Romance Languages and Literatures and Comparative Literature departments, the metaLAB is a “do tank”— an experimental platform of artists, technologists, and scholars delving into novel ways of approaching technology with creative and critical lenses, merging and redefining scientific and artistic fields.

In his clear-framed glasses, neatly-trimmed goatee, and plain mauve sweatshirt, Schnapp lights up describing one of the metaLAB’s ongoing projects, the Future Stage: an initiative to revolutionize the performing arts.

Schnapp says he and his team drew inspiration for this project after watching performing artists turn to technology in order to continue their craft during the pandemic, such as through live streaming or TikTok videos. “How do we take those opportunities and really make them integral to forms of spectacle today, in ways that don’t just treat live streaming as a backup?” he asks.

The Future Stage’s visions and principles can be summarized in its manifesto, which has garnered attention worldwide and been translated into eight languages. Written by almost 40 leading figures in the performing arts world, including dancers, technologists, and policymakers, the manifesto includes phrases like “performance as a human right,” “an expanded notion of liveness,” and “democratize and delocalize.”

Although some may conceptualize this type of work as digitizing the arts, Schnapp says he doesn’t view it that way. Rather, he argues, technology and science and the arts feed into each other — and

always have fed into each other — to generate projects and ideas that help advance society overall.

“I don’t like the label ‘digital humanities’ because it suggests somehow that the ‘digital’ is doing the innovative work,” he says.

“I think it comes on both sides of that formula, that we need to renew and reinvigorate our models of teaching, knowledge production — every aspect.”

Taking the Future Stage as an example, Schnapp explains that part of the project also involves finding ways to engage younger audiences in traditional art forms, like live opera. “It’s not about having screens all over the place,” he says.

The reluctance to erase boundaries between different disciplines, he argues, ultimately prevents academic institutions from addressing key issues, chief among them making knowledge accessible. And although artistic and humanistic fields cannot shoulder this burden alone, Schnapp acknowledges that they are uniquely suited to addressing these problems.

For example, he says, the metaLAB has pursued several projects telling stories of climate change using environmental data, conveying the information in visualizations that are more accessible to the public than academic articles.

“There’s a role for many different disciplinary traditions and practices to be at the cutting edge of how we create meaningful experiences and how we make arguments and how we build knowledge today,” Schnapp argues. Citing the 20th century novelist C.P. Snow, he adds, “The kind of ‘two cultures problem’ is really an artificial division between what are, in reality, all practices that are very closely interconnected.”

The “cutting edge” doesn’t have to be restricted to projects like the metaLAB’s, however. Even in the realm of more traditional academia, scholars can find ways to weave together different fields for broader goals.

Menon, who uses computational methods to study the Victorian-era novel, does just that. Menon researches direct speech

within 900 19th-century novels, combining data and literary analyses to observe large-scale trends in the use of speech.

Yet Menon says that she thinks of her methods as reliable tools to “answer the kinds of questions that have always interested [her] in humanistic inquiry,” rather than a form of “digitizing” the humanities.

Both Schnapp’s work with the metaLAB and Menon’s use of computational models exemplify what the collaboration between different fields could yield. But their projects are currently outliers; in order for interdisciplinary projects to become more common, universities and students must first address the “two cultures problem,” primarily by first recognizing that the humanities are worth enough for them to incorporate into their academic repertoire.

The university has been striving to address this through initiatives such as the Intergenerational Humanities Project, a rotating threeyear research project that aims to involve students and faculty from all backgrounds in in-depth, interdisciplinary humanities research. Under the I-HUM umbrella is the recently-launched Undergraduate

Scholars Initiative, a two-course series for sophomores which emphasizes the foundational skills of the humanities.

The university is expected to approve so-called double concentrations later this month, according to an announcement from the Undergraduate Council. Double concentrations would allow students to study any two concentrations of their choice without the requirement of writing a thesis that combines both disciplines — a common complaint against the current joint concentration system.

But the cultural bias against the humanities makes it difficult to find a path forward. And though a college curriculum isn’t enough to change a culture, Menon argues that incorporating more humanities classes into students’ schedules is a start. She believes that people must value the humanities individually, aside from their possible contributions to other fields.

Menon argues that having a “mandatory class” for all students similar to Humanities 10 could encourage students to engage with the humanities. She says that the syllabus does not need to match up exactly to Humanities 10, but that the class should include “great

works of literature.”

In her opinion, there are two ways to measure the decline in the humanities: by concentration numbers or by enrollment figures. While she says that concentration numbers are declining at a much faster rate than enrollment numbers, her suggestion for a mandatory class emphasizes that those enrollment numbers still matter and can make a significant change in students’ understanding of why the humanities are valuable.

Set against a deep plum background, a virtual gallery displays hundreds of works from around the world: poems and letters, both typed and handwritten, paintings of sunsets, sketches of solitary figures, graphic designs, and everything in between. “I ponder over words in solitude,” reads one letter from a 16-year-old girl in India. “I make these turbulent stories that talk of nothing but storms, sometimes paradise too, but storms are more real than utopia.”

Alongside her younger sister Sarah C. Lao ’25 and Carissa J. Chen ’21, Lao launched the Dear Loneliness Project — a part of Schnapp’s metaLAB — shortly after the pandemic began, as a means of helping people navigate large-scale isolation and uncertainty. The project aims to be the longest letter to the world, a memorial to 2020 from people across the globe, each documenting their emotions and experiences during the pandemic.

But for Lao, the Dear Loneliness Project holds a more intimate significance: it allows her to rekindle, even if only briefly, her love for literature. Through read-

ing the letters — like ones from a 70-year-old man inspired to write back to letters he accumulated throughout his life — Lao remembered the distinctly human aspect of literature that she once cherished so much.

During the pandemic, she was reminded of the “empathy superpower” of literature, which helped her reframe her views of what it means to lead a meaningful life beyond having a stable job.

“I think that it really put things into perspective, like, what is our life?” she says. “For me, it’s all about developing empathy and being able to live more lives than the one you are confined to, which is important in a time of great turmoil,” she adds.

For Soleil C. Saint-Cyr ’25, the pandemic helped her realize that she didn’t have to — or rather, shouldn’t — choose between her interests in literature and computer science.

She says that during the pandemic, “people became isolated, became depressed, even though

there were Zoom calls every day. Because we realize the limitations of technology, a lot more people who have previously heavily invested in the idea that tech can solve all of our problems are kind of shifting away from that.”

For the founders of the Salon, the pandemic also brought to light the broader stakes of treating the humanities as irreconcilable with the sciences. Deshpande describes the “sharp dichotomy” between people who would focus solely on the scientific angle of the pandemic — information on how viruses spread — and people who looked at the pandemic in terms of its social and psychological consequences, determining that humans fundamentally needed in-person connection.

But he says neither side was effective in creating a viable solution to the pandemic for all. “It seems clear that any sort of sensible policy would have to take into account both the first side of things, which is traditionally the scientific enterprise, and the second side of tra-

ditionally humanistic enterprise,” he says.

Although it remains too early to determine whether the pandemic will truly lead to the sustained cultural shift required to break down the perceived binary between the humanities and the sciences, it appears that it has at least given some individuals the chance to re-evaluate their priorities when it comes to pursuing a certain field. Efforts like the Salon may be the impetus for generating such a change.

By the end of the hour at the Salon’s first meeting, someone has to remind the group of the time, pulling them from a discussion that leaves them with more questions than answers about the pursuit of knowledge — within and beyond the walls of Harvard. Still, the gathering provides a beacon of hope: the beginnings of a cultural shift away from field divisions that has the power to foster meaningful collaboration.

What’s up, MTV? I want to welcome you to my crib: the one and only Lamont Library.

We’ll just enter through these turnstiles right here. Sorry about the inconvenience, but security is an absolute must. Home invasion is no joke, seriously. A lot of sketchy characters in Cambridge — have you heard about that bicyclist who assaulted three grad students? Just goes to show you, no one is safe these days. That’s why Lamont is so great — now you never have to brave the perilous journey back to your dorm at 3 a.m.

So right down these stairs is the lounge — oh, sorry, could I ask you to take your shoes off? We may be college students, but we’re not total animals. You can just put them on that bottom shelf over there. Great. You can hang your scooter on the scooter rack right next to it.

So here you can kick back, watch some TV, chill with your friends — it’s fantastic. There are some daybeds here but if you want those good eight hours, I would recommend the quiet space on the top floor. You’ll get some of the best rest of your life up there, guaranteed. No mattress topper necessary.

Oh, hey! We just passed by some Lamont Lifers. Once they figured out you can call in sick and Zoom into class instead, they’ve literally never left. Love those guys.

By the way, bathrooms are right down the hall. They’re way more spacious than those dingy hall bathrooms you’re used to. We’ve also installed some hooks to hang toiletries and towels and such to really make people feel at home.

So, I know what you’re thinking: What about food? I’m getting hungry, too. In my humble opinion, the Lamont Café trumps any d-hall — no chaos, just vibes.

Trays are resting on that Thoreau collection, utensils are in those pencil cups. No, HUDS actually doesn’t know about this set-up; slowly but surely,

we’ve pilfered the Annenberg utensils to the point where we have a whole set. I mean sure, maybe we took a little too much that one time and they had to start giving the freshmen paper plates, but Harvard’s got enough dough that they just replaced them after, like, a week.

We have Honey Nut Scooters, Marshmallow Mateys, all the classics. If you’re looking for healthier snacks, there’s some raw zucchini and ranch from last night’s brain break. Oh, hot food? We’re going to have to go down to the bottom level. A while ago we told a freshman that if he dug a tunnel from Annenberg to Lamont with a soup spoon, we’d get him punched by the Porcellian.

Ha, no, I don’t think he actually did it with a spoon. I think he got his friends from MIT to help him out. I think they used a tunneling machine — you know, like the one from that episode of “Phineas and Ferb”? The Drill-inator? Actually, now that I think about it, I’m pretty sure Dr. Doofenshmirtz is an MIT alum. Anyways, now we have this nifty pipe that runs straight from ‘Berg to our beloved Lamont.

Then we did some….networking….and now we have a guy from HUDS who chucks Annenberg’s leftovers into the pipe and boom! It’s pretty simple. This way, our meal times are a lot more reasonable. I still can’t believe that breakfast closes for you guys at 10:30 am. That’s practically when we Lamonsters go to sleep.

Well, thanks for visiting! Please, don’t be a stranger, and come by anytime, I mean it. Our doors are open 24/7.

“You can kick back, watch some TV, chill with your friends — it’s fantastic.”

If I kept hauling home a bag of miscellaneous produce every week, if I kept laboring over Moroccan baked fish and spiced chickpea stew, then maybe I was growing. Maybe I was clawing back control.

You could trace my family’s heritage of eating disorders all the way back, like an unbroken vine. When my mother was a teenager, she kept a notebook meticulously recording every calorie she ate each day. Before her, my grandmother binged on bread and margarine

after work, then told everyone that she was throwing up because of migraines. At the bottom of the tree lies my little sister, who tells me about “fear foods” like hot chocolate and pizza, who used to eat 1,300 calories a day, who hasn’t had a regular period in years. Grandmothers, mothers, daughters, starving

all the way down. Except for me.

As a teenager, I felt suffocated by the feeling that I had escaped a family curse on the slimmest technicality. Unlike my mother and sister, I never counted calories. Sure, I had my moments of dysphoric self-hatred in the bathroom mirror, and I took a perverse sense of pride in those days when I forgot to eat lunch — in other words, I was a teenage girl. But most of the time, I didn’t think about food at all. And as I grew older, stumbling through the minefield of female adolescence, I realized I had to fight to protect that precious, hard-won reprieve. When my sister eyed my plate and asked my mother how many calories I was eating, I lashed out like a cornered animal. “Keep your disease off me,” I said, terrified, as though her disorder could infect me if I let it get too close. The deadly allure of getting smaller was always lurking — at the dinner table, on TV, in photos of the female singers I idolized.

My mom did her best to shield us from this pressure, to save my sister and me from the pitfalls of her own childhood. She unfailingly pointed out examples of unrealistic, Photoshopped, or bone-thin models in fashion magazines. She reassured us that fat was normal and healthy, told us that she was proud of her own “chubby” thighs.

And there was always plenty of food on the table. Believe it or not, despite — or maybe because of — her long history with scales and crash diets, cooking is my mother’s calling. When I was a kid, she started building her own food blog; over a decade later, it’s her flourishing full-time job. Even on days when she only ate

a bowl of yogurt for dinner, my mom served the rest of us Korean beef, or honey-roasted brussels sprouts, or overflowing pulled pork sandwiches. As long as I didn’t have to make it myself, I could keep food at the periphery of my thoughts, at a safe and comfortable distance.

You’d think having a parent who cooks for a living would make me an above-average chef myself, but you would be dead wrong. Cooking was always so clearly my mom’s domain; I never felt the need to do it myself.

Until, of course, the pandemic. In the summer of 2020, I got permission to live on campus (flying back home to California felt like an unnecessary risk), alone in a DeWolfe suite meant for four people. For twenty years, I had subsisted entirely off my parents’ cooking or the convenience of an unlimited dining plan. I dropped my boxes at the entrance to my new room, walked into the empty kitchen, and realized I had no idea how to preheat an oven.

My mom could not have been more thrilled. She texted me a list of basic pantry ingredients I should buy before I did anything else, sent me an industrial kitchen’s worth of cooking utensils and supplies, and mailed me a copy of America’s Test Kitchen’s “Cooking for Two.”

That summer, I embarked on a new project: learn to cook; learn to function on my own. At first, I had to call my mom roughly three times per meal, whenever I encountered a problem or question: “How long do I heat the oil? Can I substitute white vinegar? Does this look done to you?”. Every effort to make dinner took me at least two hours, without fail, so I made a habit of

eating half a box’s worth of pasta at 10 p.m., alone in my apartment. There had to be 50 other students in the building with me, but I hardly ever saw or heard a soul on the way up to my anonymous, hotel-esque room.

When summer melted into fall, I moved into a dark and vaguely depressing Somerville flat with two of my friends, where we would spend nine months play-acting at adulthood. As the months rolled by, I accelerated my efforts to fall in love with cooking. I splurged on a New York Times Cooking subscription and bought every ridiculous ingredient their recipes called for. I wandered the grocery store aisles aimlessly, waiting for inspiration.

I had a full-time job that I felt totally unqualified for. I hadn’t seen my family in eight months, and every time it seemed marginally safer to buy a plane ticket to California, another Covid wave snuffed out the plans. I was in a relationship with someone who made me feel microscopically small and cosmically unloved. But if I kept hauling home a bag of miscellaneous produce every week, if I kept laboring over Moroccan baked fish and spiced chickpea stew, then maybe I was growing. Maybe I was clawing back control.

In September, I couldn’t celebrate the Jewish new year with my parents. Desperate to believe in new beginnings anyway, I made my mom’s honey cake recipe. Although I tried to follow the instructions to a T, the batter consistency was all wrong; far from the moist, rich cake I remembered from childhood, mine turned out dense and dry. When it got colder, my roommates and I made weekly pilgrimages to Star Market, and I

learned to make shakshuka — one of the few Israeli foods my mother ever cooked, and definitely the only one I wouldn’t screw up. A few nights a week, I biked over to my boyfriend’s house and tried to paper over our growing distance by cooking kimchi fried rice together or — in a day-long fit of true desperation — baking him a coconut cream pie. When we sat down to eat what we’d made, he would pause to imitate my

chewing — mouth open, loud, obnoxious and crude, a little ritual that never failed to shrink my appetite.

Despite my best efforts, I dreaded cooking every day. I couldn’t seem to develop the right instincts; everything I made was just a little too salty, too dry, too heavy on the sauce. But I kept

pushing, in part because I needed to be competent at something. A failure to feed myself would be the nail in the coffin of my gap year self-improvement dreams, definitive proof that my life was careening off the rails. Here was the ultimate test of my independence, my freedom from disorder: If my mother and sister’s vision of control was an empty stomach, mine was an unrelenting commitment to making better food.

In December, my parents caved and bought me a plane ticket home. For a month, I indulged in the pure luxury of sitting down twice a day for a meal cooked by someone else. Cocooned by the warmth of family meals and temporarily freed from the burden of managing my own life, I

felt myself exhale for the first time since September.

When I flew back to Boston in January, the icy wind and darkness felt unusually cruel after a month in California, my loneliness sharper and more inescapable, my shortcomings overwhelming. All around me, it seemed like people were thriving despite the circumstances: bagging fancy summer jobs, learning new quarantine hobbies, reconnecting with family. Meanwhile, I was plagued by the constant sense that I was barely holding it together. Even cooking a homemade meal every night — the least I could do — began to feel impossible. Prepping ingredients took forever. I ran out of ideas for new recipes and let my groceries expire by the bagful. I ordered takeout three nights a week. No matter how hard I tried, no matter how creative I got, I couldn’t stop hating cooking.

In March, just as Cambridge began to thaw and those first misleadingly sunny days returned, the disaster I’d been trying to stave off for a year finally happened: my boyfriend broke up with me. When he broke the news, I was in the middle of cooking shakshuka for dinner. Every 10 minutes, the kitchen timer interrupted our parting conversation. “Tell me what I need to change about myself. I’ll do anything.” Stir in cumin and paprika. “I don’t think we can fix this.” Pour in the tomatoes; let it simmer. I’d made him banana bread the day before, one last attempt to show him my devotion by subjecting myself to baking. In the days that followed, when I couldn’t eat for the first time in my life, my roommates finished it.

For those next few agonizing weeks, I gave into the allure of

starvation, of getting smaller. In a haze of what I now understand as grief, sustaining my body became a dreaded chore, an unmanageable task, an afterthought. I drank Soylent just to force down the necessary nutrients, because cooking was totally out of the question. I shrank.

Yogurt,” “Pasta with Burst Cherry Tomatoes,” things that looked good enough to proudly feature on my Instagram story. And I ate like hell.

When my relationship collapsed, so did any remaining illusion that I could tightly control my life, or that I would fall apart if I couldn’t. Perfecting my sheetpan dinners wouldn’t save me from unpredictability, or failure, or disappointment. And when I finally stepped away from my single-minded, self-defeating cooking mission, I didn’t lose meaning or direction. If anything, I suddenly found moments of joy and pride in the kitchen that had once been buried beneath my anxiety and expectations.

lock, every time I said “it hurts me when you treat me like this” — I grew an inch.

These days, I still struggle to eat in public. Halfway through a sandwich in the Smith Center, I’m suddenly paralyzed with selfconsciousness, hearing the sound of my chewing like an echo in a dead-silent cave. On first dates, I prefer drinks to dinner. It’s hard to be witty and personable while you’re calculating the cleanest, least obtrusive way to eat a bowl of pasta.

But summer came anyway. I relearned how to care for myself and rediscovered my hunger, the sheer joy I could absorb from a slice of chocolate cake or a microwaved bowl of mac and cheese. I hardly cooked that summer, but when I did, I nailed it: “Sheet-Pan Chicken With Potatoes, Arugula, and Garlic

I’d always thought that by becoming a talented chef during my gap year, I could produce tangible evidence of my personal development. I wanted a trophy to bring back with me to campus, proof that I hadn’t wasted my leave of absence, a sign of my newfound maturity and strength. Here’s the thing about growing, though: you usually can’t feel it happening. I never noticed, but every time I led a meeting or started a new project at my grown-up job, every time I convinced our landlord to fix a broken refrigerator or install a

But I’m still discovering my own growth, all the ways I’m different and more resilient than before. It shows up in small, surprising ways. When I attend an exercise class or go for a bike ride on my own. When I play guitar for my friends, even though I’m embarrassed. When I trust myself to do a hard job well.

In the fall, I moved back into Currier House with my blockmates after a year and a half apart. We really won the lottery with housing this year: our suite has its own fully-equipped kitchen. I haven’t cooked in it once.

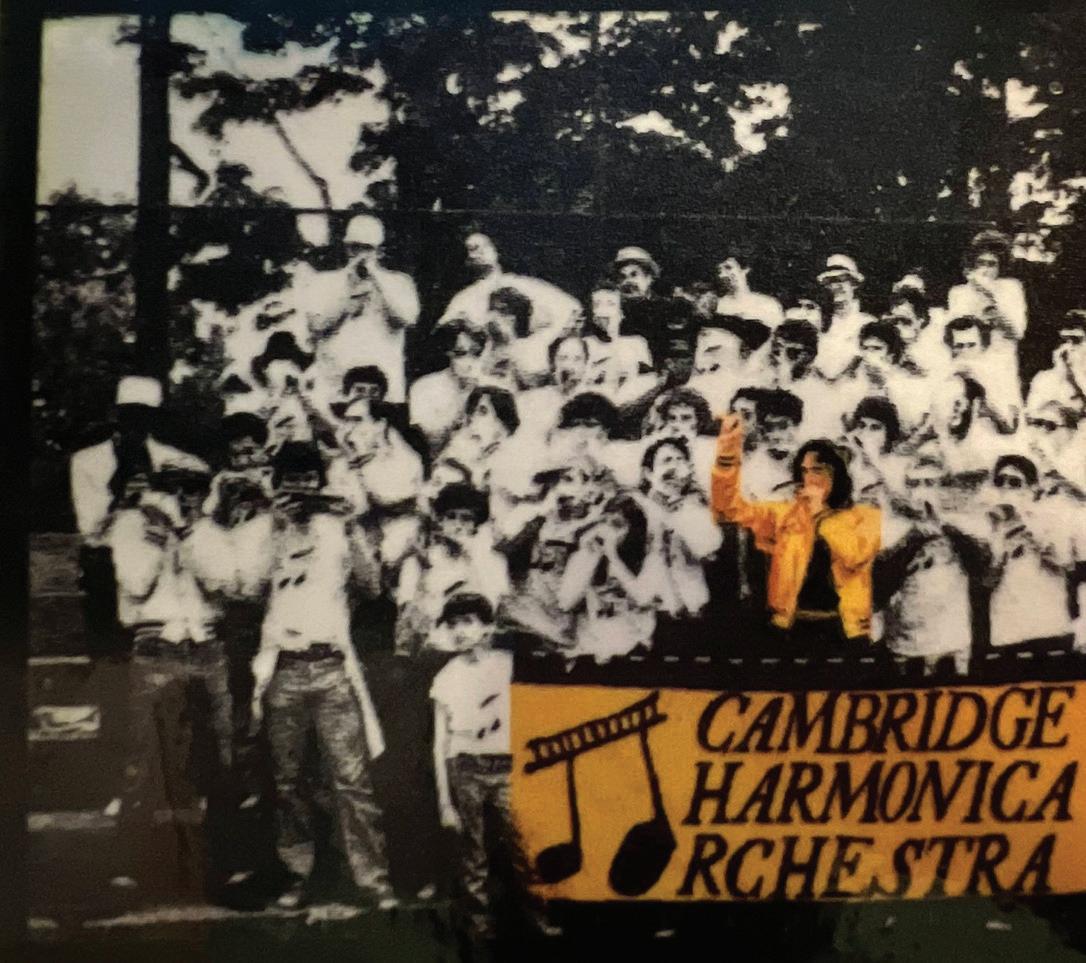

The year is 1981. It’s mid-June. Burgeoning summer beckons Cambridge residents from their hibernation against the spiteful New England winter. The Cambridge River Festival, an annual weeklong celebration of art and music, is in full swing, and today it culminates in a parade. Painted floats pack the streets, kids traipse down Memorial Drive, and people of all ages line the sidewalks to watch the festivities. This year, a new group brings up the rear of the parade: the Cambridge Harmonica Orchestra.

The orchestra, a historic gem of the Cambridge music scene, had its glorious debut more than 40 years ago. Well known for their vibrant yellow jackets and laid-back attitudes, this group of musicians hopped between bars and music fests, bringing the blues harp to Cambridge and beyond.

The group reached peak popularity in the mid ’80s, with a crowning performance at a club in Boston called The Tam. Fortyseven members packed the bar for a night described by the Boston Globe as “harmonica heaven.” NBC broadcasted the event.

Unfortunately, enthusiasm waned in the years to follow, and the CHO disbanded in 1986 due to the logistical challenge of booking gigs and keeping members involved.

So how did this short-lived band of roving players come about? And what is a harmonica orchestra in the first place?

The CHO was conceived in 1981 as a response to the city government’s call for new additions to the River Fest. Founder Otis Read wrote up a proposal, received a $200 grant, and had to recruit enough harpists, or harmonica players, to make it happen. “I had no idea that I would be able to pull it off,” Read says.

Drawing on his background as a working musician, he reached out to the other harmonica players he knew. The eccentric group of hippies and rock-and-rollers, pros and amateurs alike from around

Massachusetts and Washington, D.C., reached about 350 members at its height. The group included musicians like James Montgomery, whose band opened for Bruce Springsteen and the Allman Brothers.

“I don’t think there was anybody that would have said no,” Montgomery says. “We [were] going to get together with 30 wacko people and have some fun.”

The Orchestra had periodic gigs with a portion of its extensive membership attending each performance. Practice sessions, mostly casual, were held in a garage space in Brookline.

“We’d have a monthly gathering of people — all sorts of people smoking weed and playing,” Read says. “It was just chaos, and it was wonderful.”

Though Read came up with the idea for the CHO, music director Pierre Beauregard was equally crucial to its function. He chose their repertoire, mostly blues and some New Orleansstyle Mardi Gras tunes, and he arranged the pieces specifically for the Orchestra. CHO harpists split up lead, rhythm, and counter-lead parts and were often accompanied by bass harmonica, drums, accordion, and washtub bass.

Read says Beauregard’s musical leadership brought character to the CHO. One of his favorite moments from the group’s performances was when Beauregard would announce a breakdown during a solo, spurring a full-on polyphony.

“We’d be playing a song, and there would be a chorus, and Pierre would say, ‘Everybody take a solo,’” Read says. “The whole band would just go crazy. The drums and the bass would be pounding along.”

BENJY

B. WALL-FENG

Buildings are demolished to make way for the construction of the Holyoke Center in 1964. Courtesy of Harvard Archives.

“Front of Holyoke Center Becomes a Hippie-drome,” blared a 1967 Crimson headline. Even in Cambridge, some 3,000 miles removed from the Summer of Love, the reporter’s point was clear: The rich kids in “Truc-loads of mod clothes and jewelry” and poor kids flaunting their “general dishevellment [sic]” were not fit for this part of Harvard. An HUPD officer expressed a desire to “eliminate” the loiterers. The Crimson writer envisioned an area filled with “clean-cut collegiates,” but the project’s architect had explicitly designed the Holyoke Center as a community space. The tension

between this goal and its execution has followed the building to this day, even though the Holyoke Center is now the Smith Campus Center and the “hippies” are long gone.

Holyoke’s architect was Josep Lluís Sert, then the dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design. He anticipated a hub that would connect Harvard Yard to the buildings near the Charles River by way of a ground-level arcade lined with community shops. When construction wrapped in 1966, the hulking concrete mass was unlike anything the area had seen before. The abstract artist Mark Rothko painted a series of murals for the penthouse dining room. Sert called the building a

“bridge”; future administrators would deem it “Harvard’s front door.”

But the initial reception was divided. While architects and architecture students appreciated Sert’s innovative Brutalist design, some Cambridge residents were taken aback by a structure that dwarfed its neighbors and took up an entire city block. One critic noted that the end of construction might comfort locals who had seen the eight-year project and “perhaps feared that it would simply continue to grow, like some robust and appetitive organism.”

For The Crimson in 1963, “Amdriw T. Wxsl” (likely a digitization error) poured scorn on its size and constitution. “Holyoke Center’s 28

massive concrete face is in jarring contrast with all of the structures around it,” Wxsl wrote, adding that while Harvard had previously built eyesores, “none before were visible from all over Cambridge.”

The ends of the arcade originally opened onto the street but were permanently closed soon after, to mitigate what one writer calls Sert’s “apparent disregard for the severity of New England winters.” This was the first blow to Sert’s dream. As more and more university services took up quarters in the complex, its connection to the city faded. A 1979 article published by the American Institute of Architects recalls that Holyoke transformed Cambridge from a “college town of mostly inexpensive shops and eateries into a high-priced, fashionable shopping magnet.” The Rothko murals became a source of embarrassment, having faded unexpectedly after less than two decades’ exposure to

as having been “ripped, spattered with food and marred by graffiti.”

Time would further clarify what was meant by “community.”

In her memoir, Lauralee Summers ’98 recalls arriving at Harvard and meeting a Korean man named Sam, who sometimes “slept standing up inside Holyoke Center, across from his usual bench. He couldn’t sit because a Harvard policeman would tell him to move on.” In 1993, a Harvard police lieutenant said of Holyoke: “The University is not in the business of supporting the community through homeless shelters.”

Holyoke stood like this for decades, weathering the usual degree of structural decay. In 2013, following a donation from Richard A. Smith and Susan F. Smith, Harvard renamed the building after its benefactors and began a five-year process of redesigning. This renovation replaced the bottom floors with a new, glass-lined, sun-filled space. Greenery now lines the walls. There are courtyards behind glass panels that hold trees native to the area; the trees had to be lowered in. Project directors hoped that the rechristened Smith Campus Center would offer a “dynamic, vibrant, central gathering space for the Harvard community, Cambridge residents, and for the many visitors who visit our campus every day.”

ago, HUPD officer Anthony T. Carvello received widespread criticism for apprehending a homeless Black man in Smith by shoving him to the ground and screaming at him; it later transpired that Carvello had acted similarly in two previous cases, allegedly using a racist slur in one.

Around the time that planning began on the redesign, the Harvard Art Museums employed a novel technique to redisplay the battered Rothko murals. Retouching the faded areas might cause irreparable damage. Instead they developed software to calculate, pixel by pixel, the color of paint that should have been in every part of the canvases and used a low-wattage projector to cast those colors directly onto the murals. The exhibit ran for eight months.

Many surviving photographs of the interior as it was in the 1960s were taken for architectural studies and are necessarily devoid of people. The film’s hazy quality accentuates their eeriness. Holyoke feels alternately like it has just been abandoned or like it is waiting for people to arrive, and it’s hard not to see it like you might the paintings that once hung there: either the skeleton of a dream or the beginning of one, rendered in some imagined glory by a trick of the light.

sunlight in the penthouse, and by April 1979 they were placed in storage. A 1988 New York Times article describes the installations

Proportionally little of the remodeled area is accessible to the public. The lobby has a front desk, coffee stand, and a small working area upstairs. The vast, multi-floor commons area plays lo-fi beats and requires a Harvard ID to access. Campus police routinely awaken non-Harvard affiliates who try to sleep in the center in violation of its rules. Two years

One critic noted that the end of construction might comfort locals who had seen the eightyear project and “perhaps feared that it would simply continue to grow, like some robust and appetitive organism.”

ACROSS

1 Gravelly tone

5 Opposite of spicy

9 It's eaten in shame

13 Words to a betrayer

14 Hero who rescues a princess from a fire-breathing monster

15 Apt name for a werewolf

16 "Was it ___ I saw?" (classic palindrome)

17 Make amends

18 Setting in a creation myth

19 *The Evil Queen, Snow White (1937)

22 Astronaut Jemison

23 Pilot Solo in a space opera

24 Prefix with -lobite or -ceratops

25 Instrument made from a container

26 Did what was necessary to awaken

Sleeping Beauty

31 *The Wolf, Little Red Riding Hood (1812)

35 The Greatest

36 Name on two Harvard libraries

37 Grass that can be turned into milk without a cow

38 ___ Rabbit (trickster in Southern folklore)

39 Word that sounds like its first letter

40 *The Witch, Hansel and Gretel (1812)

44 Stone faced being

46 Even just one

47 Fractions of a lb.

48 In support of

49 Born in France

52 Storybook conclusion... or what each of the answers to the starred clues is?

58 Vedic fire god from whose name we get "ignite"

59 ___ oneself (use some elbow grease)

60 Band "advised to chill" in a 2002 ruling

61 Gospel singer Winans

62 "This isn't my first ___"

63 King or queen, perhaps

64 Imperialist Russian leader

65 Early platform for 14-Across

66 Fivers DOWN

1 Setting for a story about knights and castles

2 Heart parts

3 All the world, per Shakespeare

4 Charlie who starred in a Flamin' Hot Super Bowl ad

5 Morning in Marseille

6 "Man" or "Lady" preceder

7 Field for phon. and gram.

8 Playground retort

9 Faith healer in Dungeons and Dragons

10 Bengals RB Johnson

11 It's equal to a G

12 Shrink, like 15-Across' namesake

14 Make do

20 Ergo

21 "___: Legacy" (2010 film with a Daft Punk soundtrack)

25 "I like the cut of your ___!"

26 Way to a vampire's heart

27 Spider's little sibling

28 WWI spy Mata

29 Abbr. on a town border marker

30 Severe

31 Digitally recorded journal

32 State with Ames at the center

33 Zig or zag

34 Icy

38 Journalist Nellie

40 Like someone listening to a story by the fire

41 Gem-producing mollusks

42 Be bold enough for

43 Citation that lacks information (abbreviation)

45 Like the Grimm fairy tales, vis-a-vis their Disney versions

48 Nobel Peace Prize winner with Rabin and Arafat

49 Head covering that exposes the eyes

50 Accustom to (var.)

51 "Zounds!"

52 Sentence starting with TIL, usually

53 It sometimes comes after dark

54 Cuzco resident

55 Neural network component

56 Article intro

57 Document protecting the undocumented

view the solutions here :