FIFTEEN MINUTES

FM CHAIRS

Olivia G. Oldham ’22

Matteo N. Wong ’22

EDITORS-AT-LARGE

Jane Z. Li ’22

Scott P. Mahon ’22

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Josie F. Abugov ’22

Paul G. Sullivan ’22

Malaika K. Tapper ’22

Rebecca E.J. Cadenhead ’23

Maliya V. Ellis ’23

Saima S. Iqbal ’23

Roey L. Leonardi ’23

Sophia S. Liang ’23

Kevin Lin ’23

Garret W. O’Brien ’23

Harrison R.T. Ward ’23

WRITERS

Rebecca E.J. Cadenhead ’23, Katie L. Sevier ’25, Kaitlyn Tsai ’25, Isabel T. Mehta ’25, Michal Goldstein ’25, Sarah W. Faber ’24, Sammy Duggasani ’25, Tess C. Kelley ’24, Henry J. Lear ’23

FM DESIGN EXECS

Cat D. Hyeon ’22

Max H. Schermer ’24

FM PHOTO EXECS

Sophie S. Kim ’23

Jonathan G. Yuan ’22

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Angela Dela Cruz ’24

DESIGNERS

Cat D. Hyeon ’22, Max H. Schermer ’24, Samanta A. Mendoza-Lagunas ’23

PRESIDENT

Amanda Y. Su ’22

MANAGING EDITOR

James S. Bikales ’22

BUSINESS MANAGER

Melissa H. Du ’22

EDITORS’ NOTE

This school year marked the start of a potentially dramatic shift in the state of policing in Boston public schools. City and state legal reforms to the authority of both the Boston Police Department and school police officers mean a decades-old surveillance state — as well as a recent communications network between school police officers, BPD officers, and federal immigration officials — may begin to unravel. But teachers, parents, and advocates alike are unsure what, exactly, new limits set on the police mean for students, or whether a few laws can really upend such a system that has targeted Black and brown youth since its inception.

This week’s cover story, by REJC, begins with the origins of policing in Boston public schools and traces its evolution to the present-day, mysterious “gang assessment database” containing information on dozens, if not hundreds, of adolescents and young adults — many of them racial minorities and immigrants. With the future of the Boston public school surveillance state unclear, it is more important than ever to understand, as precisely as possible, its past.

As schools transition back to the physical realm, some are being converted to the virtual. KLS and KT explore the Virtual Harvard Project, an effort to construct a fully virtual, highly-detailed 3D model of the University. Meanwhile, other school spaces remain stagnant. After over twenty-five years of fighting for a more suitable prayer space, ITM and MG find that Harvard’s dedicated Muslim prayer space is still in the Canaday basement. And, in the spirit of changing the University, SWF and SD explored the legacy of Mildred Fay Jefferson, the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School and a vocal anti-abortion activist.

Change, though, can be difficult to stomach. TCK reflects on her relationship with her sisters, one where she often enacted control and took on the role of a parent. After leaving home, watching the film “My Neighbor Totoro” helped her loosen her grip. HNL also writes beautifully of control, detailing his struggles with hypochondria, queerness, and an unforeseen medical diagnosis.

Strangely, though this is only our second print issue in over a year, it is also the penultimate of our tenure. It appears that change is inevitable; in the case of our cover story, it is also necessary. We hope you, our dear reader, take the time to sit down with this issue, allow time to be still for a moment, and contemplate the moment our writers, editors, and designers have attempted to capture. With love,

OGO & MNW

THe Virtual Harvard Project

Outside of the Harvard Museum of Natural History, a small group of people gather under a tent, talking quietly over their laptops. Pedestrians stroll by the freshly mowed lawns framing the walkway to the building, and students and faculty alike ascend and descend its concrete steps on their way to and from classrooms and labs. The scene is quiet, pastoral, normal.

But a walk through the museum’s unassuming red door to the right of the main entrance and up two flights of stairs reveals a wildly different — virtual — world. At the end of a hallway filled with offices and seismology posters sits a room illuminated by blue LED lights, its rightmost wall lined with mannequins wearing VR headsets. Rows of chairs sit in the middle of the room before a panoramic screen, currently displaying a view of Earth from outer space; behind them, a research assistant mans a table with three monitors, controlling the displays on the larger screen.

This is the Ultra High Resolution Science Observatory, the primary facility of the Visualization Research and Teaching Laboratory, headed by computer engineer and 3D artist Rus Gant. Gant has worked as director of Harvard’s Visualization Lab since 2012, before which he worked on initiatives at MIT and Carnegie Mellon, applying over 40 years of visualization skills to computer science, science education, archaeology, and museology. Currently, Harvard’s observatory houses one of Gant’s many projects: constructing a fully virtual model of the University.

Gant first conceived the idea to construct a virtual Harvard in the summer of 2019, inspired by past undertakings like the Giza Project — a Harvard-based digital archaeology initiative to build 3D reconstructions of the Giza Pyramids and surrounding artifacts — that focused on making education more engaging. When the pandemic struck months later, he decided that it was the time to turn his idea of making a 3D model of Harvard into a (virtual) reality. Over the course of the last 14 months, Gant and a member from his team, Sean O’Reilly, have created models of 115 out of 230 of Harvard’s main buildings, from Widener Library to the Harvard Museum of Natural History to Longfellow Hall.

“Quite honestly, it turned out to be really hard,” Gant says with a chuckle. “We knew it was going to take some time, but we just didn’t realize how much time.”

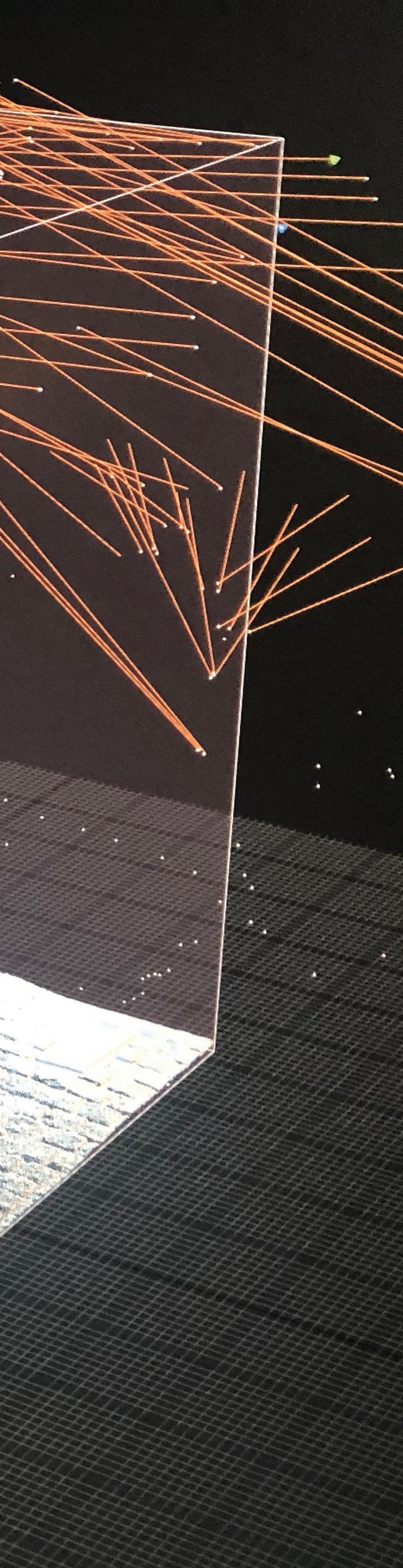

To generate each model, Gant and his team take panoramic photographs from various vantage points within each building. Taken from tripods controlled by an iPad using technology from Matterport — a company that enables users to create virtual 3D models of buildings — the photographs are then compiled into a dollhouse, a 3D model of the entire scanned building showing the general

Sevier and Kaitlyn Tsai“‘The future just arrived. And it’s free!’”

- Rus Gantis a drone photogrammetry scan of the John Harvard Statue by Brian Vizaretta. Courtesy of Rus Gant.

layout and the specific spaces one can access. Small circles that mark each camera point act as links to additional information about the building.

The second stage of the project involves transforming the models into digital classrooms. To do this, Gant and his team use Unreal Engine, a gaming program traditionally used for large multiplayer games, which allows users to fully immerse themselves in and navigate a virtual environment.

At this point, Gant and his team can use the SmartStage, a small platform placed before a full-body green screen. Those standing on the stage, like lecturers or tour guides, can be inserted into the virtual environment as the green screen displays a scanned model. The SmartStage, created by the media company White Light, was loaned to the Virtual Harvard project by the Verizon Innovation Lab.

However, Gant says getting permission to scan Harvard’s buildings has taken almost as much effort as the scanning itself. The project was initially met with resistance from administrators and lawyers as well as almost every department in the school, primarily because of privacy concerns.

“We had to get permission from everybody, every step of the way,” Gant says. “Each laboratory wants to control their own department. The security guys were like, ‘Well, this is a roadmap for terrorists.’ Museum guys [said], ‘Well, now they know where to steal things.’ But once we showed them the result, and we said, ‘You own this, nobody else can show it unless you say it’s okay,’ they were comfortable.”

After a month of discussions,

Gant’s team finally received the green light for the project in August 2020, sponsored by the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning. From there, resistance transformed into gratitude as staff members found novel ways to utilize the virtual models outside the realm of education.

Senior planner Cara Noferi, who manages the FAS models, noticed that the models could be put to good use with RoomBook, the platform that faculty and students use to reserve rooms for meetings, as well as with Centerstone, the database of floor plans for the University.

By incorporating virtual models into RoomBook, students and professors can preview classrooms, seeing how much space they have and what type of equipment comes with each room. The images also come in handy for the maintenance and facilities workers who use Centerstone to locate specific building areas for tasks like fixing pipe breaks.

“For these two groups, this is phenomenal,” Gant says. “They never had pictures before. So now we’re just going to hand it to them, like, ‘Oh, here, the future just arrived. And it’s free!’”

Moving forward, Gant and his team want to finish scanning the remaining 115 buildings of Harvard’s main campus and use Unreal Engine to transform them into immersive virtual environments. From there, students would be able to join their virtual classes on Virtual Harvard using their computers, smartphones, and AR/ VR glasses. For Gant, these efforts represent a way to not only revolutionize education, but chart an entirely new path in AR/VR technology.

“We’re trying to bring Harvard into this environment several years before everybody else,” Gant says. “This will be a future of both human- and machine-mediated teaching and learning, and we see Virtual Harvard as our first portal to this world.”

The Invisibility of Muslim and Hindu Prayer Spaces on Campus

Navigating the basements of Canaday Hall can feel a bit like shuffling through a labyrinth of pipes and offices and boiler rooms, but that’s not all that is kept beneath the surface of this freshman dorm. Tucked away among other typical basement amenities like the common room, laundry, and trash disposal lie

the only two spaces dedicated solely to students of Muslim and Hindu faiths at Harvard College.

The Muslim prayer space, located at the basement entrance of Canaday Hall E, and the Hindu prayer space, located in Hall B, which accommodate individual and small-group prayer, are largely invisible to the eyes of the hundreds who pass through Har-

vard Yard every day. With Memorial Church towering only several yards away, and Rosovsky Hall — the Harvard Hillel building for Jewish students — just down Plympton Street, some members of the Muslim and Hindu communities feel even more starkly that their limited underground arrangement does not fufill the entirety of their spiritual needs.

To Khalil Abdur-Rashid, Harvard’s first full-time Muslim chaplain, the Muslim prayer space is “a band-aid on a bleeding wound.”

ate space for Muslim students to practice their faith is not new, but has been ongoing for more than 25 years. A 1995 Crimson article reported that Muslim students resettled seven different times in 1994 until landing on the Canaday basement and, even then, looked for a larger space. The issues raised in the article then — access, acceptance, respect — are closely related to the issues raised today by Muslim and Hindu students and administrators.

the population here on campus.”

According to the Harvard Crimson’s demographic survey on the class of 2025, Muslim and Hindu students constitute 3.9 percent and 3.1 percent of the student population respectively. Together, these groups nearly equal the 7.4 percent of students of Jewish faith.

The Hindu prayer space opened in 2006 as the first of its kind at Harvard. The Muslim prayer space, meanwhile, has existed for more than 20 years. It is not the sole location that Muslim students can visit to gather or pray — students find community in a prayer and meditation room on the seventh floor of Smith Campus Center and congregate for larger Friday prayer in Lowell Lecture Hall — but it’s the only place specifically dedicated to only people of Muslim faith.

The fight for a more appropri-

“The space is not conducive, appropriate, or enough,” Abdur-Rashid says. “It is in need of tremendous renovation and change and reform.” There is not enough space in Canaday to gather and pray without waiting in line, and the space needs significant upgrades; Abdur-Rashid says the carpet needs to be replaced and the room needs more storage. “Honestly, going down there in the basement, it always felt so desolate, bare, and depressing,” Alaha A. Nasari ’24, a Muslim student, says.

For Hindu students, Dhwani R. Bharvad ’22, the Worship Chair of Harvard Dharma, admitted that the group was “a little worried” about their first religious gathering post-Covid and even considered running two different shifts for people to come into the prayer space due to its capacity limits.

Both Muslim and Hindu students acknowledge their gratitude for their respective spaces, but also express feelings of disappointment and isolation. “As much as I have love for [the Muslim prayer space],” Ali A. Makani ’24 says, “it’s still clear to every single Muslim when they walk in there that we are relegated to the space of invisibility, that Harvard refuses to publicly acknowledge and support

The basement location directly affects how Muslim and Hindu students feel about the extent to which their communities are welcome on campus, giving visibility added importance. “You typically associate a basement with where you throw stuff in there that you don’t really care about,” Alvira Tyagi ’25, a Hindu student, explains. To some, the spaces feel especially inappropriate given their intended purposes: spiritual retreat. “Imagine if they put CAMHS in a basement,” Adbur-Rashid says. Makani puts it simply: “I just don’t like seeing brown people put in basements.”

Abdur-Rashid argues that the lack of visibility exacerbates the situation by making it hard to address. “The more you can’t see communities gathering, the more the problems don’t get realized,” he said. “The discussion about space is always undermined by the fact there is no visibility regarding the need.”

University spokesperson Nate Herpich declined to comment on the perceived inadequacies of the College’s Muslim and Hindu prayer spaces.

According to Abdur-Rashid, conversations about updating the Muslim prayer spaces began over a year ago but came to a halt during the pandemic. The chaplain now plans to bring up these concerns about space at the next meeting of the Board of Religious, Spiritual, and Ethical Life. Bharvad also expressed Harvard Dharma’s desire to remodel its space.

“It’s not about communities in isolation,” Abdur-Rashid says. “It’s about multiple communities in collaboration.”

“I just don’t like seeing brown people put in basements.”

- Ali A. Makani ’24

The state of Surveillance in i Boston schools

The Boston Regional Intelligence Center is housed within the Boston Police Department’s headquarters, a boxy, four-story structure made of glass and concrete wedged between two city parks. It was established in 2005, the height of the War on Terror, to keep Boston safe from foreign enemies. The BRIC is a “fusion center,” a site of information sharing between local and federal law enforcement, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement. In essence, the BRIC is a magnifying glass — through it, what’s observed by a city cop can also be observed by numerous federal officers.

The BRIC is also something of a black box. Its unit has established a system of thousands of cameras throughout the Boston area, which officers can use alongside video analytics software to track specific cars and people. These cameras operate 24/7,

but their exact purpose remains unspecified; they are simply there to identify threats. The BRIC also operates several databases containing the private information of thousands of Boston residents, some of whom were not accused of criminal offenses; they were simply identified as threats.

In November 2015, a 17-year-old student at East Boston High School, who has been publicly referred to as “Orlando,” was found to be a threat. The year before, Orlando had immigrated to the United States from El Salvador, alone and without documentation, in search of his father. According to a later report, he and another student had “attempted to start a fight” in the school cafeteria, “but were unsuccessful.” He was subsequently identified via security camera footage by a school police officer, who had also heard rumors that he might be in a gang. The officer wrote up a school incident report about the episode, noting in

the last line that “this incident will also be sent to the BRIC.”

Orlando didn’t realize that the BRIC had his information until nine months later, shortly after he turned 18, when he was arrested by ICE officials. They found him at his father’s home and took him to an immigration detention center, a facility that looks like a prison but whose inhabitants, because they are not citizens, have even fewer rights. Immigrants can be kept in detention indefinitely and without bond; Orlando waited there for over a year. When he finally got to immigration court, lawyers for the Department of Homeland Security made their case: Orlando should be deported because he was a member of MS13, a federally-identified gang.

Their evidence against Orlando came from a file in a BRIC database that collects information about suspected gang members. Orlando’s file included the school incident report and pictures of him wearing a Chicago Bulls hat, which officials had obtained from his Facebook (the Bulls, aside from being a popular sports team, share a symbol — bull horns — with MS-13). It did not include any alleged criminal offenses.

Though Orlando and his lawyer maintain that he was never a gang member, he eventually agreed to his own deportation — as reported by WBUR, after being detained for so long, he was too depressed to continue fighting the case against him.

Away from the spotlight, there were other Orlandos. Between 2016 and 2018, immigration attorneys around Boston noticed a surge in cases where DHS relied on the BRIC gang database to deport their clients. Many had been identified as gang members when

they were younger than 18, often through incidents that occurred at school.

Information in the gang database acquired from Boston Public Schools includes — as in Orlando’s situation — school incident reports, which document misbehavior in school or well-defined criminal activity. It also contains intelligence reports filed by Boston School Police, which document any “activity that is documented for intelligence gathering purposes or for the sole purpose of reporting observations.” This activity can include where a student is seen, who students are seen with, or what students are wearing, on or off campus.

mation is “relevant” to that criminal activity. Lawyers and advocates have argued that many of the files entered into the BRIC do not meet this standard.

In 2019, WBUR reported that BPD officers and ICE officials had been communicating extensively via email about specific undocumented immigrants in Boston, often with the intention of finding civil immigration violations for which the resident could then be deported.

Reports about adolescents in the BRIC gang database also include those filed by BPD officers, who usually write reports about people they stop, and sometimes about those whom they merely observe. Some Boston residents, typically young men of color, report that they have been consistently stopped by BPD officers from their early teens on.

The federal rule dictating how fusion centers like the BRIC function stipulates that they can collect information about someone “only if there is reasonable suspicion that the individual is involved in criminal conduct” and the infor-

Recent public records requests filed by immigrant and civil rights organizations reveal that school police officers in Boston engaged in a similar pattern of behavior. Before recent changes, school reports were supposed to be sent up a bureaucratic chain of command before reaching law enforcement. But, as suggested by Orlando’s case, communications between school police officers and officials from the BRIC were often much more direct. Lawyers say hundreds of documents yielded from their organizations’ public records requests show that officers directly emailed officials from the BRIC and from ICE on specific students of interest. A Boston Public Schools spokesperson did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but school officials have in the past repeatedly stated they do not share information with federal authorities.

Over the past two years, the landscape of policing in Massachusetts has changed. Boston School Police, who are now only referred to as employees in the Office of Safety Services, lost their police powers under Massachusetts’s 2020 Police Reform Act. They are no longer uniformed, no longer have squad cars, and can no longer arrest students or file

School officers directly emailed officials from the BRIC and from ICE on specific students of interest.

intelligence reports. The reports they can file are limited to alleged criminal offenses, medical emergencies, and missing students. Meanwhile, Boston’s Trust Act, updated in December 2019, limits the information law enforcement can share with ICE. An amendment to BPD’s rules governing its gang database now raises the bar for the quality of information needed to establish gang membership.

Advocates have welcomed these changes. Still, some are waiting for Boston to make concrete plans for better-funded social services and avenues toward restorative justice. They have yet to see whether the reforms passed will be enough to disrupt the decades-old, entrenched systems of policing and surveillance they are meant to address — a system that takes for granted that certain children should be seen as threats.

In 1974, the Boston School Committee, the governing body of Boston Public Schools, began

preparing for an invasion. Months earlier, federal District Judge W. Arthur Garrity had blown up the Boston school system. He ordered the schools to desegregate; as he wrote at the time, the city “must eliminate all vestiges of the dual system ‘root and branch.’”

For decades, Boston had had a significant Black population. In the first half of the 20th century, millions of Black refugees from the South, fleeing racial violence, flocked to the North. There was a train line connecting Florida, the Carolinas, and Virginia to Northeastern cities. Over five decades, 50,000 stayed on the line until Boston. The city was likely far from what they’d imagined. They were forced into segregated communities and denied the same access to public resources and schools as white residents. Brown v. Board came and went in Boston; Black residents who protested de-facto school segregation and poor educational conditions were violently cracked down on by the Boston Police Department.

In September of 1968, BPD

began a two-week occupation of the Gibson School, an elementary school in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Roxbury, after a group of parents from the school complained to the School Committee that the Boston School District was providing their children with an inferior education. In response, the School Committee sent in the police.

That year, BPD officers were deployed all around Roxbury to suppress Black students and parents protesting the quality of their schools. On Sept. 26, after hundreds of Black students held a rally to demand equality, BPD broke up the crowd by beating protestors with nightsticks. These officers removed their badges so that they couldn’t be identified. A Black Boston high schooler at the time told the Boston Globe, “If you want a bloodbath in Boston, keep the white police in Roxbury.”

For years, the School Committee had operated under the premise that Black children, foreign to Boston, should be contained. In 1974, following Garrity’s ruling, the prospect of their entrance into white schools called for a special strategy.

“We need adequate police protection,” remarked a school committee member at a meeting on January 1, 1975, while discussing demands the committee would make of the governor. “Give that to him in a short paragraph and say the burden is too heavy on Boston and the trend will be that Boston will be predominantly black. ‘Now, what are you going to do to help us?’”

A 1975 letter from a white South Carolinian to Boston’s then-mayor Kevin H. White expresses the fears of many white parents at the time: “You will find

that as the Negro integrates, so will the rate of crime. You will find your schools almost completely segregated within itself … I don’t envy you and the people of your city in the years ahead.”

Citing potential violence from Black students, White and the school committee deployed half of BPD’s entire police force inside schools in the first year of desegregation; in the second year of desegregation, the figure rose to 70 percent.

In reality, the majority of violence in the first years of school desegregation came from white parents and white police. In October, the National Guard was called in to enforce the desegregation order over white protestors. Inside schools, police disproportionately targeted Black students; in-school suspensions and arrests of Black students, which spiked in the first years of integration, became so severe that a lawsuit was filed against the School Committee to end rampant discrimination against Black students.

This mass deployment of officers was unsustainable; in the late 1970s, a “safety and security” force was deployed inside Boston Public Schools to ease the strain on BPD. By 1982, this force had become Boston School Police. Until summer of 2021, school police officers were Special Police Officers designated under Rule 400a of the BPD, meaning that they were deputized but lacked the training of a full police officer — they needed only 160 hours of training, in comparison to the approximately 800 hours required by a full-time police academy.

Still, Boston School Police possessed many of the same powers as BPD. They could arrest students and file reports. They were

uniformed and had squad cars. In at least the first few years of their deployment, they had radios directly connecting them to BPD. Effectively, Boston School Police existed to extend the BPD’s reach inside schools, combating threats from within.

Anti-Gang Patrol was created in July 1979 to combat a surge in gang violence; a 1982 Boston University Law School report on police treatment of juveniles notes that in 1979, 30 percent of all 911 calls in Boston “involved gang disturbances or activities.”

Here is how Boston law enforcement defines a gang currently:

“A gang is an ongoing organization, association, or group of three (3) or more persons, whether formal or informal, which meets both of the following criteria:

1. Has a common name or common identifying signs or colors or symbols or frequent a specific area or location and may claim it as their territory and

A 1979 phone call to the Boston Police begins:

“Caller: On (name) street there is a gang of teenagers playing tag football under these new lights. Can you get them out of here please?

Police operator: Yes, ma’am. Caller: Thank you.

Police operator: You’re welcome.”

Another starts as follows:

“Caller: There’s five or six kids out here. I wouldn’t say kids. They’re grown-ups. They’re playing out there and they’re making a lot of yelling so we can’t listen to the T.V.”

And a third:

“Caller: Hello, I’m calling from (address). Get these kids off the steps. It’s going wild here.

Police operator: What are they doing?

Caller: These kids are getting wild again, getting lousier.”

In response to each of these calls, BPD dispatched its newly-formed Anti-Gang Patrol. The

2. Has associates who, individually or collectively, engage in or have engaged in criminal activity which may include incidents of targeted violence perpetrated against rival gang associates.”

This definition has always been broad. From the Anti-Gang Patrol’s inception in the late ’70s, fears about gang violence in Boston largely revolved around “disruptive youth gangs,” or groups of kids who didn’t belong to large, formalized gangs. In documents from the ’70s on, “youth gangs” and “gangs” are used interchangeably. As Matt Kautz, a PhD candidate at Columbia University who studies the origins of school police in Boston, put it, “there’s this substitution between what might constitute an organized gang, and what is just a group of young people together.”

That same BU report, describing the actions taken by the Anti-Gang Patrol, notes that, during its first ten days of operation, “the gang unit responded to 1,015 complaints, dispersed 1,258

“If you want a bloodbath in Boston, keep the white police in Roxbury.”

- Student, 1968

groups of youths, arrested 166 disorderly youths, and took 131 youths into protective custody for detoxification.” The report does not mention any arrests of adults. The Anti-Gang Patrol was disbanded a few months later, but the BPD’s strategy of targeting “youth gangs” remained.

Most of these youths were Black. Christopher Winship, a sociology professor at Harvard who worked with Boston Police in the ’80s and ’90s to develop community policing strategies, notes that “virtually all gangs in Boston are Black.”

Kade Crockford, director of the Technology for Liberty Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts, phrases it differently: “The Boston Police Department could classify many different organizations as gangs,” but only seems to do so “when they are made up of predominantly Black and Latino people.” BPD did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding alleged racial profiling of youths in their policing practices.

In 1989, a lawsuit was brought against BPD for a “policy to ‘search on sight’ certain young, black persons in Roxbury.” Documentation of the lawsuit describes that BPD also had “a secret list of ‘known gang members’” of 750 people. People on the list were “searched on sight,” which the lawsuit describes as “a proclamation of martial law in Roxbury for a narrow class of people, young blacks, suspected of membership in a gang or perceived by the police to be in the company of someone thought to be a member.”

A judge in the lawsuit found BPD’s actions to be unconstitutional. But the secret list of “known gang members,” and BPD’s harassment of Black communities in

Boston, remained.

By the ’90s, following press attention around BPD’s stop-andfrisk tactics, Boston’s Black community reached a breaking point with BPD. Winship wrote in a 1999 report that, “the Boston Police Department was in desperate need of an overhaul to deal with all the negative publicity.”

As part of its attempt to remedy its relationship with local communities, BPD pledged that it would develop a more targeted strategy. In 1996, BPD developed Operation Ceasefire, “an innovative collaboration that focuses targeted interventions on individuals most likely to become offenders and victims in firearm violence.”

Operation Ceasefire aimed to identify those most likely to commit crimes and divert them before they caused harm. In other words, instead of regarding entire neighborhoods with suspicion, the police would select specific residents for the brunt of their enforcement.

Much of the work of Operation Ceasefire was carried out by the Youth Violence Strike Force, established in 1993 as a unit of police officers focused on “the collaborative use of order maintenance tactics to quickly ‘cool’ any area of the city in which gang firearm violence flares.” Essentially, their purpose was to identify kids who might be gang members.

Thomas Nolan, a former Boston police gang detective and now a professor of sociology at Emmanuel College, joined the Youth Violence Strike Force at its inception. The strike force, like BPD in Roxbury, kept an internal list of names of suspected gang members, which they used to monitor those identified as “problems.” According to Nolan, however, there were no criteria for what consti-

tuted a gang member: “It could be, ‘I believe this kid is in a gang because I saw him with some other guy.’”

This information was kept within BPD until the aftermath of 9/11, when the Boston Regional Intelligence Center was founded. From there, Nolan explains, the list formerly kept by BPD developed into a gang database and became sprawling.

This move was supposed to help law enforcement be more efficient. Winship believes the database expedites these processes by telling officers, “‘here’s where you should focus your attention.’”

But there are now thousands of names in a gang database accessible by federal law enforcement, and some of the people in it dispute the allegation that they were ever in or associated with a gang at all.

On a colorless day in February 2018, a Black Boston resident named Keith took an Uber to a barber shop appointment. Exiting the car, he noticed two BPD officers in a black car watching him; as he walked up the street, he started filming from his phone. The video, which he later uploaded to YouTube, begins on a carlined street framed by steel-gray sky. As the police car comes into view, one of the officers rolls down the window. He looks at Keith through narrowed eyes.

“You’re not Kevin by any chance, are you?” He asks.

“Nah,” says Keith.

“You sure?”

“Of course.”

“What is your name?”

“Why do you want to know my name?”

“You look like someone we’re

looking to speak to.”

Keith pans to his face, looking exasperated: “Again, here we go.” The officer continues:

“Where do you live?” “You don’t need to know that.” The officer then asks him a series of similar questions — about his address, occupation, and identity. “It’s noon time on a Thursday, what are you doing?” “What are you doing?” “I’m working.”

Eventually, the video ends as Keith walks away and the officer returns to the car.

Keith didn’t seem surprised that the police would stop him; this seems less reflective of a guilty conscience than statistical reality. In 2019, department data shows that despite comprising a quarter of the city’s population, Black Bostonians made up 69 percent of police stops.

In response to public outcry over Keith’s video, BPD spokesperson Michael McCarthy told the Associated Press that the stop happened while officers monitoring the area saw a man they believed to have a weapon. McCarthy assigned both parties blame, adding, “we can take away that the officer needs to behave better and those that are interacting with the police need to behave better” — even as it remains unclear why the police stopped Keith or what, exactly, was wrong with his “behavior.” There are other aspects of this incident that, while telling, are likely routine. There is much made about Keith’s name; the officer also asks him for his address. What exactly the officer intended to do with this is unknown, though recording personal information is a typical part of police stops — they

are used for Field Interrogation/ Observation/Encounter reports, which are records of observations BPD makes of the people they interact with.

FIOEs are supposed to be filed every time a stop occurs, regardless of whether the person stopped is accused of criminal activity. In fact, they’re often not even suspected of criminal activity. According to a 2014 ACLU report on racial disparities in BPD stops, “In three-quarters of all [FIOE] Reports from 2007-2010, the officer’s stated reason for initiating the encounter was simply ‘investigate person.’ But ‘investigate person’ cannot provide a constitutionally permissible reason for stopping or frisking someone.”

FIOEs can even be filed in cases where there is no contact between an officer and the person being

surveilled at all. As Crockford, of the ACLU, noted in a 2018 Medium post, officers can make FIOEs based on observations from police cars or across the street that record what someone is doing, “who they’re with, or what they’re wearing.” (In an emailed statement last week, Sgt. Detective John Boyle, a BPD spokesperson, wrote that information entered into the BRIC is determined to meet the “reasonable suspicion” of criminal activity standard in the federal rule governing fusion centers.)

Something else is striking about Keith’s video: the officers knew the name and general appearance of who they were looking for (though not well enough to avoid confusing him with someone else). “Law enforcement are very aware of their communities that they surveil. They know people by name, they know them by face,” says Valeria Do Vale, lead coordinator of the Student Immigrant Movement, an organization that educates and fights for the rights of immigrant students. Who gets targeted for surveillance isn’t random: they have already been identified by police as warranting observation.

How exactly an officer knows enough to look for a specific person without ever having met them remains unclear. Still, there are known ways in which personal information obtained through an FIOE might become accessible to other officers — one of these ways is via the BRIC gang database.

FIOEs and other field reports have always been the bedrock of the gang database. FIOEs that indicate gang membership or association are entered and assigned points. The points system is outlined in Rule 335 of the

Boston Police Department Rules and Regulations. Each “Contact with Known Gang Associate” is 2 points. Having a “Known Group Tattoo or Marking” is 8 points.

“Information Developed During Investigation and/or Surveillance” is 5 points. The list goes on.

When an FIOE report about someone is sent to the BRIC to be added to the gang database, a file is created about them. From there, the individual can accrue points as more FIOEs or other forms of evidence are filed: At 6 points, they’re a gang associate, and at 10 points, they’re a gang member. If you live in a predominantly Black or Hispanic neighborhood, earning an entry in the database is not difficult. Public records requests from the ACLU have revealed that as of 2019, of the thousands of people entered into the gang database, 90.2 percent are Black and/ or Hispanic, and just 2.3 percent are non-Hispanic whites.

To live in proximity to Black and brown residents, then, is to be in contact with people already identified as gang members and associates. As Mary Holper, the Director of the Immigration Clinic at Boston College Law School, notes, “If you go to school in East Boston or Chelsea, which have a high Latinx population, and you don’t know who gang members are, who are suspected of being gang members, you are highly likely to be seen with them. Per being seen by somebody, it doesn’t take long to get to 10. All it takes is five times. So there you go. You’re a gang member.”

Doyle, the BPD spokesperson, wrote that the BRIC gang database is “a critical tool in the City’s strategy not only for responding to violent criminal activity, but also for

supporting at-risk young people, preventing community violence and victimization, and offering participants safe and healthy pathways to a better life.” He wrote that data in the gang database helps provide youth services, inform prosecutorial decisions, and respond to crime through the “efficient deployment of police resources.”

Through the deployment of police resources, Holper says that her clients are frequently “stopped and frisked, questioned about whether they’re a gang member.” In the 2014 ACLU report, Ivan Richiez, an Afro-Dominican Bostonian, recalls getting stopped by BPD for the first time in 2007, when he was 14 years old. BPD approached Ivan and some friends as they sat on a bench near where they lived, frisked them, and asked them what they were doing, where they lived, and if they were in a gang.

Not all of the evidence in these files comes from FIOE reports alone. A given file could have a variety of information about a given suspect. This can include possession of gang publications, or a self-admission of gang membership. It can also include evidence collected from social media. As Orlando’s case indicates, files frequently include photos of their subjects, which are then viewed by officers who access them.

Someone in the gang database usually has no way of knowing that they’ve been entered into it; police are not required to inform them. While individuals now technically have the ability to request whether they’ve been entered into the gang database, several lawyers have said instructions for how to do so remain unclear; the BRIC privacy and civil liberties policy does not

outline a specific mechanism to make such requests.

But if someone is in the gang database, the police know a lot about them, although it’s not clear who has access to it. Elizabeth Badger, a senior attorney at the Political Asylum/Immigration Representation project, has expressed concerns that this information is being disseminated throughout the police department. Fatema Ahmad, executive director of the Muslim Justice League, has noticed that the Black and Hispanic young men that she works with are often stopped by BPD officers who, despite never having met them before, already know who they are — she suspects that this could be because they’ve been put into the gang database.

For these young men, being persistently stopped by the police “makes them feel like they must be doing something wrong,” says Emily Leung, supervising immigration attorney at the Justice Center of Southeast Massachusetts. “It makes them become disengaged with school, and they become disengaged with their community.”

In a 2020 Boston City Council Meeting, the BRIC’s director, David N. Carabin, told counselors that the establishment of the BRIC had corresponded with a decrease in crime in Boston (crime rates did fall in Boston, but they also fell almost everywhere else in the country over the same period).

Later, in a 2021 city council meeting, Counselor Julia Mejia asked Carabin if he could quantify the BRIC’s impact on preventing or solving crimes. “A lot of our work goes toward proactive police measures […] We have a lot of success stories, but a lot of proactive police measures are difficult to evaluate,” Carabin responded.

In an article about the meeting published in the Bay State Banner, Crockford said, “I’ve never seen a shred of evidence that the BRIC is making Boston safer. Government agencies are always required to show their work. In this case, people just kind of shrug and say, ‘The police say they need it, so we’re going to provide it.’”

In 2016, 18-year-olds around Boston began disappearing. Leung got a call early that year from an immigration attorney friend. The friend couldn’t find her client. He had completely vanished. Eventually, she figured out what had happened: Unknown to his friends or family, he had been taken to immigration detention by ICE.

For a decade-and-a-half, Boston had been a receiving ground for refugees from Central America. Conflict and civil war led thousands of undocumented immigrants to travel from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to Boston in the 1990s. From 2014 to 2015 there was another surge of migrants, mostly trying to escape gang violence. 30 percent of migrants from Central America to the United States are children; half of them are unaccompanied by an adult.

Two years later, immigration attorneys from around Boston noticed that more of their younger clients were being detained. Badger, from the PAIR project, suspects the uptick was in response to two murders in East Boston by MS-13. These clients were of a specific type: they were all Central American migrants, had all recently reached adulthood, were enrolled in public schools in East Boston or Chelsea, and were listed

in the BRIC’s gang database.

Badger, Nolan, and others have said that the gang database seems to contain a lot of information that comes directly from Boston School Police. The streets, then, are one site of contact between suspected threats and law enforcement; schools are another.

Boston School Police have filed two kinds of reports that have made it into the BRIC: school incident reports and intelligence reports. While school incident reports document notable incidents at schools, intelligence reports have a much more nebulous purpose. Like FIOEs, they don’t necessarily document alleged criminal actions, but rather the more mundane: what a student was wearing, who the student was with, things that a student may have said.

Leung says some intelligence reports seem unwarranted. “They’re like, ‘So and so student was seen with so and so student in the cafeteria.’ Okay, well, they’re both students in school.”

Not all school police intelligence reports have even been filed inside of schools. In 2017, Boston School Police officers filed an intelligence report after receiving a tip that several students had congregated at an off-campus dog park. It’s unclear how they received this tip, or from whom — the report mentions an unnamed “resident.” School police officers then traveled to the dog park, where, according to the report, they observed children who they suspected were associated with MS-13. This report was forwarded to an officer who in 2020 was listed as a “Gang Intelligence Lieutenant” for Boston Public Schools, and it later wound up in the BRIC’s gang database.

It’s not clear why either of these kinds of reports were sent to the gang database. Nolan, the sociologist and former officer in the Youth Violence Strike Force, questions why any school police reports would be relevant to the gang database. “They have no training in how to identify gang members,” he says. “So there’s no kind of expertise that resides within the Boston School Police Department as it pertains to gang membership.”

Regardless, attorneys who have seen the information entered in

clothing choice was documented by school police. “A lot of teenagers dress the same, because that’s part of being a teenager,” she says. “You want to fit in. Boston Latinx youth have style, and they posture, and they wear Nike Cortez sneakers and it does not mean that they’re members of gangs.” School police reports appear in the BRIC gang database alongside FIOEs filed by BPD. Leung, the immigration attorney, points out that FIOEs and school intelligence reports document similarly banal activities. The information

hat. And then in the hearing, the [DHS] attorney said, ‘You’ll see, your honor, that he’s wearing a Bulls hat. And everyone knows that Michael Jordan played for the Bulls and he was number 13.’ But he wasn’t. He was number 23. Like, what are you talking about?”

What might not meet the bar for criminal prosecution can still be used in immigration proceedings. Violating immigration law is not a criminal offense — therefore, in immigration court, the rules governing what can and

the gang database say that schools had a direct role in implicating their clients. Badger says that of her clients in the gang database, all were initially entered when they were younger than 18 — many from reports made by school police.

Badger says that there were officers from East Boston High School “who wanted to label young [Central Americans] as gang-affiliated.” Of her clients, school police had noted fights, leaving school early, or even “someone else looking at someone the wrong way.”

Badger and other attorneys interviewed believe that Boston School Police turned perhaps questionable, though not criminal, behavior of teenagers into signs of gang membership. Sarah R. Sherman-Stokes, who represented Orlando, says that even

they record, she wrote in an email, would be insufficient for criminal court — but is still “routinely utilized to support the re-arrest and detention of immigrants.”

Boston Public Schools did not respond to multiple requests for comment about the utility of school police reports in identifying gang membership or about alleged racially motivated policing by safety service employees.

Sherman-Stokes says that Orlando had been detained purely because of evidence against him in the gang database — evidence, she suggests, that was circumstantial at best. “He had never been arrested or charged or convicted of any crime,” she says. In order to make the case that he was a member of MS-13, “They pulled things off of his Facebook page, like where he was wearing a [Chicago] Bulls

cannot be entered into evidence, and the rights of the accused, are much thinner. Undocumented immigrants’ rights to an attorney, to cross-examine witnesses, or even to be physically present at their own trial are routinely not enforced.

Immigration attorneys say that law enforcement sometimes assumes their clients are gang members, even when there isn’t any evidence against them. Sherman-Stokes recalls a 2015 incident in which she went to the asylum office with a young client from El Salvador, who was wearing what she describes as “an innocuous blue windbreaker that his mother had bought for him.” They were met by a DHS officer, who started “interrogating” him about the jacket: “Why was it that he was

“They have no training in how to identify gang members.”

- Thomas Nolan

wearing blue? He noticed that there was white piping along the jacket, didn’t this child know that blue and white are the colors of MS-13? It was really startling.”

The full extent of information sharing between Boston schools and the BRIC remains unknown.

As of 2019, 1.7 percent of entries (80 people) in the BRIC’s gang database were of children under 18. Still, this low percentage may be deceiving: Anecdotally, Badger and Leung say legal reforms and leadership changes, along with Orlando’s highly publicized case, led to a decrease in school police reports being sent to the BRIC beginning in 2018. And many who had been previously entered during high school have likely just aged: 19.4 percent of the database is between 18 and 24. Moreover, public records requests from Lawyers for Civil Rights have revealed that at least 135 school incident reports were entered into the BRIC between 2014 and 2017 alone.

In a 2020 interview with WBUR about the incident reports uncovered by Lawyers for Civil

Rights, Boston Superintendent Brenda Cassellius emphasized how the shared reports were from before 2018 and said that Boston Public Schools currently “do not share information with the federal authorities at all.”

Prior to 2020, school incident reports should have been sent to the Boston Public School Department of Safety Services, where a judgment would be made about whether it warranted sharing with BPD. From there, BPD could, at its discretion, send that information to the BRIC.

But records show that individual Boston School Police officers took matters into their own hands. As indicated by the note in Orlando’s file — “this incident will be sent to the BRIC” — at least one officer directly forwarded student information to officials at the BRIC.

That officer didn’t act alone. Badger, in conjunction with lawyers representing four groups — the Center for Law and Education Inc., Kids in Need of Defense, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights and Economic Justice, and Multicultural Education, Training, and Advocacy, Inc. — filed public records requests in 2018 that recently revealed that Boston School Police officers often directly communicated with officials from the BRIC and from ICE. Via email, school police sent federal officials information about students. Federal officials would also ask school police to monitor specific students of interest.

Lena G. Papagiannis, a Boston teacher and member of Unafraid Educators, a committee of the Boston Teachers Union that advocates for immigrant students, read excerpts from some of these emails at a city council meeting.

An email chain, initially from a BRIC official to a school police officer, reads: “Do you have a [redacted] that attends [your school]?” The officer responds, “Okay bro I am checking now and I will let you know.” The official sends the officer a picture, and the officer sends back a profile of a student. The BRIC official forwarded this all to an officer at ICE with a note: “This your guy?”

Another, from an ICE official to a school police officer and a BRIC official, begins: “Do you guys know this [student]?” The Boston School Police officer responds with, “Yes sir, he’s a student at [redacted]. We don’t have anything on him yet, still watching him. This kid has the same address as [redacted].”

A final email, from a BRIC official to multiple ICE agents with the subject “School Police Incident” report, contains a school incident report. It reads: “Note the school police report lists both [students] as self-admitting gang membership. This is gang verification gold.”

There are hundreds of pages of emails from this request. There are also emails that suggest that school police officers were communicating with federal officials via cell phone; the extent of these conversations, which were not public record, are unknown.

This testimony received no news coverage, and the lawyers involved have not yet issued any press releases about it. To protect student privacy, they did not share these documents with me.

The Boston Public Schools did not respond to multiple requests for comment about these emails. Doyle did not comment on these specific emails but wrote that under the Boston Trust Act the BRIC is prohibited from sharing information about individuals to assist ICE with enforcing civil immigration law (but not for investigations into criminal activity). An ICE spokesperson declined to respond to specific criticisms but wrote that ICE officers in Boston “have previously and do currently fully observe and comply with all local law enforcement protocols.”

Badger also says she believes school administrators did not know of these extensive communications between school police officers, BPD, and federal bodies like ICE.

Nora B. Paul-Schultz of Unafraid Educators saw the documents and was disturbed by the “casualness of the correspondence” between school police and law enforcement. “Who matters so little that their name can be shared with law enforcement without even a second thought about what the consequences of that might be?”

This treatment of children is indicative of an attitude unique

to the United States. Many other nations have a minimum age of criminal responsibility, before which they cannot be prosecuted for a crime. For most of the developed world, this is set at 18. In the U.S. there is no federally mandated minimum age — some states have no minimum age at all. In Massachusetts, it’s 12, the oldest of any state.

“We believe that students have a right to privacy and have a right to adolescence,” Paul-Schultz adds. When their misbehaviors are documented in a report, “the student has already been condemned.”

By the logic of law enforcement, these reports are necessary for public safety. But this may also mean that for certain students, schools have lost their essential function; in a blog post on the ACLU’s website, Holper noted that, “One way to protect [my clients] from being profiled, mislabeled by school police as gang members, and deported would be to advise them to stop attending school.”

As Papagiannis asks: “Safety for who, and safety from who?”

As of the 2021-2022 school year, the Boston School Police no longer exists. In 2020, in the wake of protests for racial justice, Massachusetts passed a police reform act eliminating “special police officers,” which includes Boston School Police. They are now exclusively referred to as Safety Service employees. Though the staff remains the same (the former “Gang Intelligence Lieutenant” is now listed as a “Day Shift Supervisor/ Lead Specialist”), they will no longer have police powers.

As previously stated, Safety

Service employees can no longer file intelligence reports; parents must be notified when a BPD report or school safety report is made, and only the Chief and Deputy Chief of Safety Services can choose to share reports with the liaison from the BPD school unit. The new regulations, however, do not prohibit the preparation of an Incident Report based on a Safety Services employee’s personal knowledge or observations.

Theoretically, the gang database itself has also changed. In response to public outcry, Rule 335, which governs the gang database’s usage, has been amended. FIOEs can no longer be used as the sole basis for an allegation of gang membership. Individuals who have no recorded recent activity will be “purged” from the database. BPD and the BRIC have promised to connect juveniles in the gang database with social services so that they can eventually “purge all juveniles from the gang database and stop the cycle of violence in the city of Boston” (though they will not stop entering juveniles into the gang database in the first place). A person can now also request to be removed from the database, however, Doyle wrote that while several such requests have been submitted to the BPD, “there has only been one occasion where corrections were required as a result of a redress request.”

Some advocates have expressed cautious optimism about these developments, though not everybody is as hopeful. “I can see things going back to the bad old days,” Nolan says. “It’s the same agencies, the same people. They dress them up differently, but it’s old wine in new bottles.”

retroSPECTION

Dr. Mildred Fay Jefferson, In Her Own Words

Sarah w. Faber and sammy duggasani

Sarah w. Faber and sammy duggasani

On January 21, 1947, Mildred Fay Jefferson was admitted to Harvard Medical School; four years later, she became the first Black woman to graduate from the institution — an achievement that took 169 years from the school’s inception. Today, Harvard’s libraries hold a collection in her name. But among 22 boxes of documents, ranging from Christmas cards to legal filings to her death certificate, only one lone folder contains any information about her time at HMS. These boxes live in the Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library rather than in the Countway Library of Medicine on HMS campus. Though Jefferson might be key to HMS’s history, medicine is only a footnote in her legacy. Her activism quickly overshadowed her medical contributions, and she found herself at the forefront of the prolife movement, fueling a political career that resulted in three runs for Senate.

After graduating from HMS, Jefferson became the first female general surgeon to work at Boston University’s Medical Center. Starting in the 1970s, she used her status as a doctor to argue that life begins at conception. In the March/April 1972 issue of BU’s Centerscope magazine, she wrote:

“From conception, the complex, dynamic, developing organism-child is separate and distinct from its mother. The life process, the sum total of energy-exchange reactions, is activated by the fertilization of the ovum from the female by the sperm from the male and is manifested by progressive cell division.”

In an interview with the Boston Globe in 1976, Jefferson explained that her vocation and Hippocratic oath bound her to the “preservation of life.” This interpretation of medical ethics thrust Jefferson into activist realms that would hallmark the rest of her career. Though previously she had not been open about her

Though Jefferson might be key to Harvard Medical School’s history, medicine is only a footnote in her legacy.(Left) Dr. Mildred Jefferson asked to leave conference hall at International Women’s Year conference, by Bettye Lane. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute. (Right) Dr. Mildred Jefferson receiving an award from the Knights of Columbus. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

stance on abortion, the American Medical Association’s resolution that supported freer abortion laws drove her to publicly support an opposing petition.

Jefferson officially began organizing as a member of the Value of Life Committee’s board of gov-

demand government funding of abortion for poor women, they are updating an old fascist model of social planning: keeping down social costs by getting rid of those who would run up the costs,” she contended. In her paper entitled “The Nature of the Race/

claiming they would “only create another generation of crippled slaves.” And on busing, she argued that “you just can’t force people to accept one another.”

ernors, which she left to develop the Massachusetts Citizens for Life organization. Her efforts in mobilizing members of the prolife movement culminated in the founding of the National Right to Life Committee, “the nation’s oldest and largest grassroots pro-life organization,” of which she served as President from 1975–1978. The New York Times reported that during the first year of her presidency, she “spent more time flying around the country making antiabortion speeches than she [had] performing surgery in Boston.” In a handwritten letter to President Ronald Reagan in 1986, Jefferson apologized for having missed their scheduled meeting due to her speech at a pro-life event in Atlanta.

As Jefferson became further entrenched in her pro-life work, her arguments against abortion became grounded in her social justice beliefs rather than in medicine. “When church groups

Class Factor in Abortion,” Jefferson added that “minority populations of African descent face a special threat” with abortion; she incorrectly believed abortion was a eugenics strategy that Margaret H. Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood, had used to target and cleanse the Black population through her “Negro Project.”

Jefferson’s pro-life advocacy proved powerful. In fact, she is credited with changing Reagan’s stance on abortion from prochoice to pro-life; he thanks her in a letter: “I wish I could have heard your views before our legislation was passed. You made it irrefutably clear that an abortion is the taking of human life. I’m grateful to you.”

Though she began as a single-issue advocate, Jefferson soon became vocal on a number of issues, including busing, welfare, capital punishment, and the Equal Rights Amendment. She condemned social welfare programs,

With a more developed agenda, Jefferson’s aims for public office began to take shape. Supporting the pro-life Democratic presidential candidate Ellen C. McCormack and serving on the Massachusetts Reagan presidential campaign, she garnered greater exposure in political circles. Yet all three of Jefferson’s attempts at the Massachusetts Republican nomination for United States Senate in 1982, 1990, and 1994 were unsuccessful. Apart from her active political campaigns, she continued to advocate for a constitutional amendment that would reverse the 1973 Supreme Court decision of Roe v. Wade. Her influence on anti-abortion activism has held influence beyond her death in 2010.

Jefferson’s life beyond activism has been deeply chronicled. A dissertation titled “The Politics of Abortion and the Rise of the New Right” documents the discrimination Jefferson experienced at HMS, providing insight into her distance from the institution. Jefferson’s presence in Schlesinger’s archives reflects the legacy that she chose to create instead. And in a 2003 profile in the “American Feminist” magazine, Jefferson affirms how her identities shaped the achievements she viewed as her life’s work: “I am at once a physician, a citizen and a woman, and I am not willing to stand aside and allow this concept of expendable human lives to turn this great land of ours into just another exclusive reservation where only the perfect, the privileged and the planned have the right to live.”

“I am not willing to stand aside and allow this concept of expendable human lives to turn this great land of ours into just another exclusive reservation.”

- Mildred Fay Jefferson

empty nesting : Our Neighbor Totoro

At 20 years old, my favorite film is still a kids’ movie. When I first watched “My Neighbor Totoro” at age 10, I was drawn in by how beautiful its world is. Sisters Mei and Satsuki exist in a realm of fairytale colors

and fantastical creatures, and I wanted to live in it, too. In the movie, the girls, ages 10 and 4, move to the Japanese countryside with their father while their mother remains hospitalized in the city with an illness. Among larger-than-life trees and quirky

tess c. kelleyneighbors, they befriend what I can only describe as a large magical rabbit called Totoro and his friends.

The movie reaches its climax when Mei, frustrated that her mother’s doctors won’t let her come home, runs away in an attempt to visit her mom at the hospital. For a few gut-wrenching moments, Satsuki and her neighbors fear a shoe washed up in a local pond belongs to Mei. Eventually Mei is found with the help of Totoro, and the film reveals at the end that the girls’ mother, while still in the hospital, is recovering.

I’ve rewatched the movie countless times over the past decade. If I had a comfort food, it would be this film. But that’s not to say I find it completely comforting. The older I grow, the less I feel like “My Neighbor Totoro” is a kids’ movie. Its mesmerizing surrealism can no longer hide the profound sadness of two girls missing their mother as they struggle to grow up.

Most of the movie coats this sadness in childlike dialogue and dreamlike imagery — except for one line. I decided to rewatch the movie one night over the summer with my own two sisters. As we sat on our couch, Satsuki and Mei argued, as they always do, about whether or not their mom should come home from the hospital even though her doctors worry she is too sick.

“Do you want her to die, Mei?” Satsuki suddenly asks her little sister.

The blunt delivery struck me. I noticed for the first time how it shifts Mei’s emotions from nervous hope to reckless despair, culminating in her failed journey to the hospital.

As I sat next to my own younger

sisters, the climax of the movie changed places. The main struggle of the film no longer seemed to be the search for Mei, but instead Satsuki’s struggle to be a mother figure for her younger sister.

When Satsuki chides her little sister for getting the floors of their house dirty, it’s not because she actually cares about the floors; it’s because she thinks that’s what a mother would say. When she scolds Mei for throwing a tantrum when they argue about their mother, she’s not trying to be insensitive; she’s trying to teach Mei how to be resilient, a lesson no mother is there to teach her.

My home life may not look the same as Satsuki and Mei’s, but being an older sister means I too often take on the role of a parent. When a friend spreads a rumor behind my sisters’ backs, I advise them to rise above and ignore it. When they need help with their college applications, we crank out multi-hour Zoom editing sessions. When they come home after everything at school goes wrong, I’m there, even if it’s just over text.

But Satsuki simply isn’t that good at being a parent. She’s too tough on her sister, forgetting she’s only four years old. She’s not empathetic enough, which only makes Mei more upset.

At times, I’m not any better. My attempts at teaching my own sisters to rise above drama veer into preaching passivity. I’m often overcritical, whether editing their essays for school or reprimanding them for arguing over a “borrowed” dress.

Watching this scene of my favorite comfort film, therefore, filled me with fear. With a single impulsive sentence from Satsuki, Mei’s tantrum spiraled

into something far worse. What would happen if I made the same

With my mind racing through what-ifs, it was difficult to take comfort in a movie whose ending I could recite by heart. What Satsuki and Mei don’t know is that they exist in a predetermined world of few consequences — my sisters and I do not. While I might be able to alleviate some of their problems, I will never be able to alleviate this uncertainty.

This unsatisfying conclusion stewed in the back of my mind for months. As I went about my daily college routine, I gradually came to a more comforting verdict. In worrying if I could trust myself with the responsibility of parenting my sisters, I forgot that I can trust them. While I hate to admit it, leaving home for school has meant that I am no longer as involved in their day-to-day lives; I haven’t been for years. In that time, they have continued to exist and to grow and to mature with me watching from afar, occasionally butting in with a word of advice. I’m not Satsuki, sleeping an arm’s length from her sister every night. I’m the sibling version of an empty nester.

When we FaceTimed two weeks ago, my sisters still had problems and still wanted solutions. But those solutions could come from them — they didn’t have to come from me. We may not get the cheery movie conclusion as Mei and Satsuki, but my sisters don’t need a creature like Totoro to protect them, and they don’t need me to protect them either. Although, as their older sister, I’ll always want to.

THICK BLOOD: Queer Hypochondria

AAt the community pool during a middle school summer, I started to get a headache. Or maybe it was brainfreeze, one popsicle too many that afternoon. The cause was dubious; the feeling was profound. I began to picture my brain swelling in my skull, flashbacks to a medical drama pulsing through my head. The surgeons would have to cut a hole in my skull to release the pressure, I just knew it. I used the phone at the check-in desk to call my mom, who reassured me that I was just fine. But I called again and again and again, until finally, she picked me up.

My hypochondria started that summer, around age 11. I thought that my throat was closing up every morning. That my heart would suddenly stop. That I might choke on my dinner and require an emergency tracheotomy.

High school yielded a new generation of anxieties. Gay sex was never mentioned in health class — and Googling terms like “HIV” and “AIDS” only generated more fuel for my anxious fire. I cut myself off from these search terms when I couldn’t staunch the flow of information. Alone and unsure, I told myself a purple vein was nascent Kaposi’s sarcoma, that a cough was the beginning of pneumocystis pneumonia. My fear of being gay in South Carolina was transplanted to the medical: I worked the idea into my mind that I was always a few steps away from fatal peril.

A month into my first semester of college, I went to Harvard University Health Services for my first STI panel, intent on the idea that I was a longtime, unknowing carrier of deadly disease. The wait for my results to appear online was so excruciating that after several days, I went to ask for them in person. Riding the shaky elevator to the office, I was petrified, my limbs paralyzed by my inconsolable nerves, betraying and repudiating my body.

That screening was the first of many. In the following year, I watched my purplish blood fill up tubes at HUHS and sexual health clinics in Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Cambridge. With each negative HIV test and repeated exposure to the doctor’s office, I grew a bit more confident. I found educational resources, scheduled my own appointments, and got on PrEP. I was determined to hold onto the autonomy I was building for myself, which had sat out of reach for years.

In March, I opted to see a primary care doctor for this ritual. I got my blood drawn at Brigham and Women’s — a tube more than usual — for a Complete Blood Count, a rundown of blood standards like platelets and red blood cells. HUHS and the clinics I’d visited in the past had never taken a CBC, but in the heart of Longwood’s enormously dense medical campus, it was routine.

My doctor called me on my way home. Over the rumble of the 47 bus and the staticky announcements

on the PA system, I learned of the 1.2 million platelets per microliter swimming in my bloodstream.

My too-thick, clot-prone blood. Swelling in my arteries. Creeping like molasses up my veins. My heart beat into my throat, and the static in my mind felt like fire.

The name itself was a tonguetwister: essential thrombocythemia, a hematologist later pronounced. It held a distinct, unwieldy significance — and the WebMD cache I discovered in my anxious internet somersault did

decisions, I was confronted by what had mobilized my hypochondria in the first place: powerlessness in the face of a chronic, asymptomatic condition. The agency I’d built for myself was in an instant made fragile, and it began to melt.

I picked up the phone and called my mom. She told me how, over a decade ago, she’d navigated a labyrinth of medical resources after she was diagnosed with breast cancer — if I wanted to get answers, I’d need to do the same.

the few who develop aggressive forms of cancer, new treatments are developed every year.

My first visit to the MGH Cancer Center was the most jarring. I was there for a bone marrow biopsy, my hip set to be drilled into by a wizened hematologist who, in the words of the nurse on the phone, preferred “using the old-fashioned equipment.” The biopsy could detect what genetic mutations, if any, caused my condition. As the IV pierced my vein, my clammy hands gripped the armrests, and

me no favors either. This condition increases the number of platelets in my blood, and it is classified as a myeloproliferative neoplasm, or what is technically a form of nonlife-threatening blood cancer. It is benign but chronic, and in some cases it can morph into myelofibrosis or leukemia.

A sinister unease crept up as I learned more about my diagnosis. Now living away from home and making independent medical

By necessity, I took even more of my medical decisions into my own hands. I called different hematologists in Boston and found that the MGH Cancer Center could take me within two weeks. The pieces of self-determination began to click back together. My condition would be treatable with the help of hematologist oncologists at MGH, or blood cancer doctors. Most patients can live long and normal lives, and for

I crinkled against the papered plastic chair.

But the nervousness that overcame me in the Cancer Center held a different weight, stripped of the power it once had. The nurse held my hand and stroked my back while she made light conversation. An extractive pain began to pull and pull from within my bone. My anxiety was no longer an avalanche, its former power undercut by a confidence