Paul Hyman

Ilan Brusso & Ben Flaumenhaft

The Oil Man

Cameron Leo

Elena Jiang

Lucas Galarza 12HOW SNAKES BECOME MONSTERS

Adia Colvin 14VINDICATING

Paul Hyman

Ilan Brusso & Ben Flaumenhaft

The Oil Man

Cameron Leo

Elena Jiang

Lucas Galarza 12HOW SNAKES BECOME MONSTERS

Adia Colvin 14VINDICATING

MANAGING EDITORS

Jolie Barnard

Plum Luard

Luca Suarez

WEEK IN REVIEW

Ilan Brusso

Ben Flaumenhaft

ARTS

Beto Beveridge

Nan Dickerson

EPHEMERA

Anji Friedbauer

Selim Kutlu

Sabine JimenezWilliams

FEATURES

Riley Gramley

Angela Lian

Talia Reiss

LITERARY

Sarkis Antonyan

Georgia Turman

METRO

Cameron Leo

Lily Seltz

METABOLICS

Brice Dickerson

Nat Mitchell

Daniel Zheng

SCIENCE + TECH

Emilie Guan

Everest Maya-Tudor

Emily Vesper

SCHEMA

Lucas Galarza

Ash Ma

WORLD

Aboud Ashhab

Ivy Rockmore

DEAR INDY

Kalie Minor

DESIGN EDITORS

April S. Lim

Andrew Liu

Anaïs Reiss

DESIGNERS

Mary-Elizabeth Boatey

Jolin Chen

Sejal Gupta

Kay Kim

Minah Kim

Seoyeon Kweon

Saachi Mehta

Tanya Qu

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Rachel Shin

COVER COORDINATORS

Kian Braulik

Brandon Magloire

STAFF WRITERS

Layla Ahmed

Tanvi Anand

Hisham Awartani

Arman Deendar

Nura Dhar

Keelin Gaughan

Lily Ellman

David Felipe

Audrey He

Martina Herman

Elena Jiang

Daniel Kyte-Zable

Emily Mansfield

Nadia Mazonson

Coby Mulliken

Daphne Mylonas

Naomi Nesmith

Caleb Rader

William Roberts

Caleb Stutman-Shaw

Natalie Svob

Tarini Tipnis

Ange Yeung

Peter Zettl

COPY CHIEF

Samantha Ho

COPY EDITORS / FACT-CHECKERS

Justin Bolsen

ILLUSTRATION EDITORS

Julia Cheng

Izzy Roth-Dishy

ILLUSTRATORS

Mia Cheng

Anna Fischler

Mekala Kumar

Mingjia Li

Ellie Lin

Cindy Liu

Ren Long

Benjamin Natan

Jessica Ruan

Jackson Ruddick

Zoe Rudolph-Larrea

Meri Sanders

Sofia Schreiber

Elliot Stravato

Luna Tobar

Catie Witherwax

Lily Yanagimoto

Alena Zhang

Nicole Zhu

WEB EDITOR

Eleanor Park

WEB DESIGNERS

Kenneth Anderson Jinho Lee

Mai-Anh Nguyen

Annika Singh

Brooke Wangenheim

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM

Imran Hussain

Sabine Jimenez-Williams

Kalie Minor

Nat Mitchell

Eurie Seo

Emma Zwall

FINANCIAL COORDINATOR

Simon Yang

SENIOR EDITORS

Arman Deendar

Angela Lian

Lily Seltz

Natalie Svob

Selim Kutlu 19DEAR

Kalie Minor

20BULLETIN

Qiaoying Chen & Gabrielle Yuan

BULLETIN BOARD

Qiaoying Chen

Gabrielle Yuan

Jackie Dean

Jason Hwang

Avery Liu

Becca Martin-Welp

Lila Rosen

Bardia Vincent

MVP Andrew

The College Hill Independent is a Providence-based publication written, illustrated, designed, and edited by students from Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design. Our paper is distributed throughout the East Side, Downtown, and online. The Indy also functions as an open, leftist, consciousness-raising workshop for writers and artists, and from this collaborative space we publish 20 pages of politically-engaged and thoughtful content once a week. We want to create work that is generative for and accountable to the Providence community—a commitment that needs consistent and persistent attention.

While the Indy is predominantly financed by Brown, we independently fundraise to support a stipend program to compensate staff who need financial support, which the University refuses to provide. Beyond making both the spaces we occupy and the creation process more accessible, we must also work to make our writing legible and relevant to our readers.

The Indy strives to disrupt dominant narratives of power. We reject content that perpetuates homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, misogyny, ableism and/or classism. We aim to produce work that is abolitionist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-imperialist, and we want to generate spaces for radical thought, care, and futures. Though these lists are not exhaustive, we challenge each other to be intentional and self-critical within and beyond the workshop setting, and to find beauty and sustenance in creating and working together.

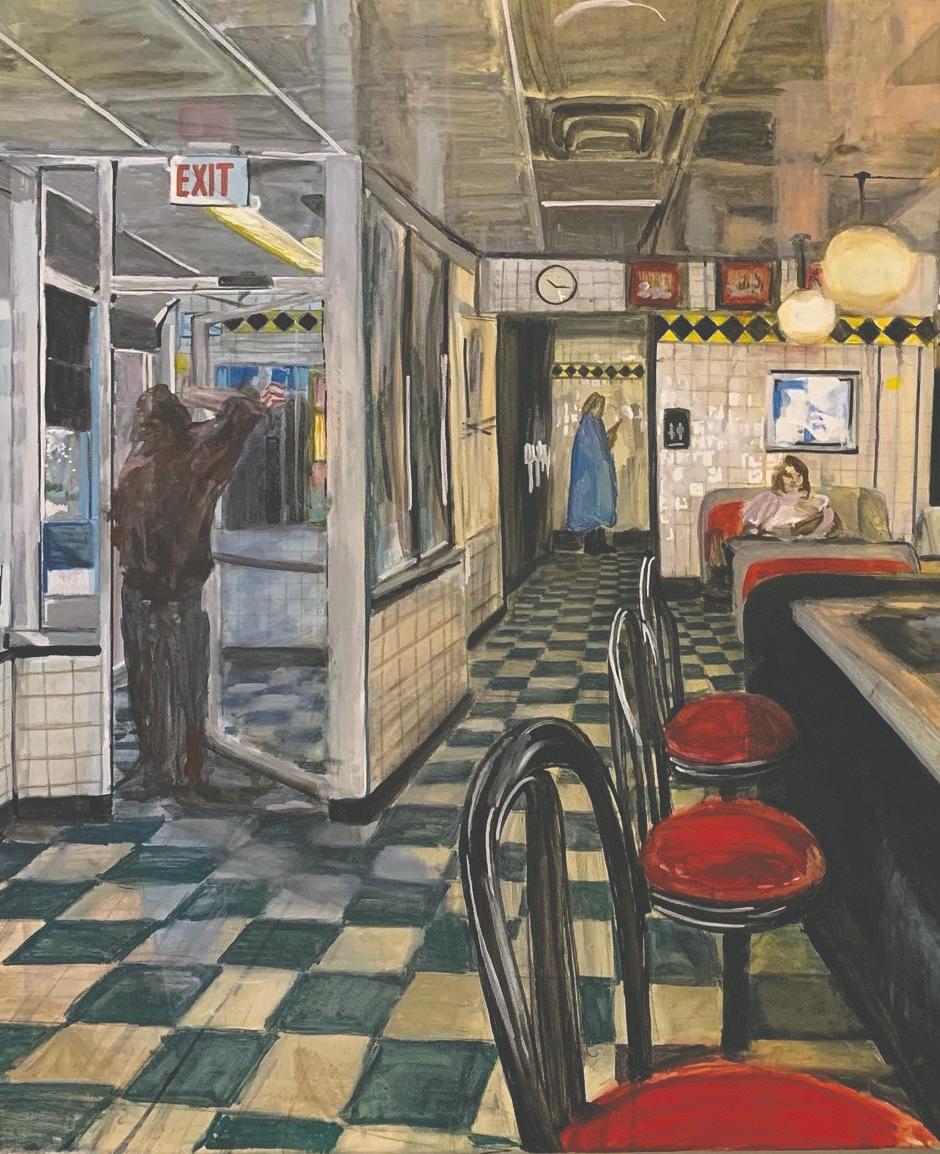

( TEXT ILAN BRUSSO & BEN FLAUMENHAFT DESIGN MARY-ELIZABETH BOATEY ILLUSTRATION JACKSON RUDDICK )

c We were swinging our feet and shaking our butts as we waddled down Wickenden, like two awesome penguins with big hearts and open minds. The sky was gray when we reached our cafe, so boisterously bright, so gallantly gay. Out front hung the pride flag with brown, pink, blue chevron, not only can you be gay here, you can be gay times a million!!! This was Small Format, but love, here, rang big! Bigger than all of the water in the world, even if it turned into an ice cube. Bigger than all of the mountains in the world gathered into one big clump. Bigger, even, than admitting to your sister that you were wrong about God.

But we’re not talking about that diva. No, we’re talking about a blessed day that started as a mistake. You see, at first, we wanted to go to Small Point, but due to wily tricksters and unprecedented energies, we ended up at a different cafe: Small Format. Wow! These two shops left us pondering the pointlessness of the format and the formality of the point. Literally everything is formatted and at some point, there’s always a point. Oh no! Have we snorted too much KNOWLEDGE?? Sorry for being �� and ��

Let’s talk about our big afternoon at Small Format.

Evoking a delightful union between divine femininity and Buzzfeed office majesty, the interior of Small Format reached out and gave us a big wet hug. We laid down our

sparkly pink diaries upon a table so wacky and great we stared at it for three whole minutes.

What we saw: a flat sheet of clear acrylic set atop a purple wave of milky acrylic, like a smushed acrylic surfer on a wave that has been dyed purple due to industry runoff from an acrylic factory. Acrylic! Acrylic! Acrylic! If we ever find a wife willing to bear our fruit, you better believe her name will be Acrylic. What a great word. Tucked behind the cash register, a disco ball hung quietly. She was a bashful bombshell, like if your pretty sister was also shy. The art on the walls featured many a nude woman, which was at first confusing to us because all the walls we’ve seen have been plastered solely with clip art and algebra puns. We do, however, know a thing or two about being surrounded by nudity (thanks APMA 470!) so we approached the paintings, hot and eager. The women trapped inside them whispered to us, “Ben, Ilan, we’re so happy you’re here!” We responded in unison (as always), “Hi! Nice to meet you! Do you like our special shoes with cool lines on them?” Their bare flesh shimmering, they looked us up and down, “We would, but those are inexpensive shoes and we’re classist.” KABLAM! Our sweet confidence, nurtured by doting mothers and pro-social messaging from Nickelodeon, fell straight to the floor with a resounding thud. Was Small Format cursed? Would our experience here never recover?

Just as the depth of despair seemed to grow ever deeper, a kind woman, probably named Amabelle but perhaps something like Tina, called out to us, not from a painting, but from behind the counter. “Hey sweet boys, are you two ready to order?” We shuffled on up, both ordering Lavender Truffle lattes and Little Baddie sandwiches.

Amabelle/Tina froze. A tear fell from her eye as she vocalized, “ah ah AH AHHHH!!!!” We looked at her confused as she continued, “SWEET BOYS! SWEET BOYS! You successfully ordered The Secret Gay Order, the best order on the whole menu, and wow I am just so proud!!”

We looked at each other in shock. Could this be true? Could this be true? Again, we wondered, could this be true? Had we done something… right? Our beloved barista continued cheerfully; “It’s a Small Format tradition that every time a customer chooses The Secret Gay Order, we show them a special little room in the back of the cafe. Please, you cute little penguins, come follow me.”

Amabelle/Tina (though looking back, her name might have also been Sharon) took us by the hand and led us down a hallway, into an impossibly ornate ballroom, the walls adorned with every color, each in their own way. An explosion of beautiful rainbows! She proceeded to the far wall, pulling a sheet from a curiously shaped figure, who, though shrouded, emanated pulses of power and delight. All at once, an explosion of dust in the shape of a heart burst into the air! As the dust settled, there he was: Alan Cumming, perched atop a pink Steinway. A groundswell of giggling gripped us like a big, big hand. Behind him, 20 world-class spin instructors engaged in the most quacked out dancing we’d ever seen. Alan ascended from his piano bench and swallowed us both in an embrace. “Oh boys,” he said, “I hope you know how good you two are.” We blushed a hue so red it made stop signs seem blue. “I see your queerness in the palm of my hand and it’s shaped like a music note. Come, boys, have a look.” We gazed upon his upturned palm, visions flashing from his hand to our eyes, then our brain, and finally to our hearts. What were these visions? We can’t say. Perhaps they were bright and warm like milk. Or lurid like a wicked sunset. No, that’s not right. We really can’t say. Instead, maybe just imagine a perfect rainbow plaid. That’ll do.

The day was shrinking to a pea as we sauntered back down Wickenden. Our world had shifted just a little. We did something right. We picked The Secret Gay Order. No one, not even the naked ladies in the painting, could take that from us. Turning back, we winked at the cafe and, almost inexplicably, the whole cafe seemed to wink back.

ILAN BRUSSO B’27 and BEN FLAUMENHAFT B’27 are identity politicians.

I

grew up in the United Arab Emirates, haunted by the textures, tastes, and hidden machinations of crude oil.

c Over the summer, I returned to the country for the first time in two years, in an attempt to trace the role of oil in a global epidemic of erotic-psychotic paranoia. It was a kind of journey to the center that brought me to an unlikely place: home videos. Home videos made by laborers in the UAE, a class of predominantly South Asian workers segregated and financially crippled by the UAE’s aggressive system of migrant exploitation. In the eighteen years that I spent in the UAE, I had never seen information about laborer life published by laborers themselves. I decided to anonymize this piece for my personal safety—it is no coincidence that information is scant. This is the result of a highly effective state-led digital surveillance project. But these videos, minimally circulated and far from political calls-to-action, have passed under the radar. I’d like to share them with you.

I. The Labor Class

To understand the importance of these videos, we have to clarify the relationship between migrant labor, oil, and Gulf policy. By 1970, the heavy-hitter oil countries of the Gulf had joined OPEC (The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) and were on track to rapidly modernize their countries’ infrastructures. The sudden access to capital was only curbed by a limited access to manpower. For this reason, the labor class was created. Mass migration from predominantly South Asian countries quickly split the Gulf’s population into two non-porous categories: a poor male labor class and a combined class of Emiratis/international expats. The labor class is massive; as of the UAE’s 2024 census, the male population makes up 68.58% of the country, while the female population makes up only 31.42%—a discrepancy symptomatic of the massive labor migrations from South Asia into the Gulf.

Employers have command of all means of transport, housing, food, employment, and immigration (through a vicious employment strategy that allows private companies to hijack laborer visas), so laborers are subject to total institutional control. The government specifies heavy concessions within ethical laws for these employers, encouraging them to contribute to the Gulf’s clandestine slave class.

The labor required of this class is highly dangerous. The urban body (malls, residential villas, refineries) is appended directly upon hundreds of Malayali, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Filipino worker deaths. Deaths on worksites caused by falling concrete, electrocutions, and drowning in

sewage (as documented by the 2022 Vital Signs Partnership report, “The Deaths of Migrants in The Gulf”) are common but underreported. In the UAE, an insidious state-sponsored story pervades the social commentary on this labor; aside from the sheer gratitude the labor class should have for the opportunity to work, there is an unspoken agreement that labor conditions are themselves extensions of the laborers. For example, while visiting a family friend, I got into a heated argument. This friend is a well-earning manager at a major oil company, an Indian woman, and an over 20-year resident of Dubai. She was convinced that I was exaggerating the situation: “They are earning more money here than back in the farms in India!” These narratives are always precluded by some horror of agrarian life. “No crime, no corruption, not like in UP [Uttar Pradesh], Kerala, or Karnataka. Here, the common man gets a well-earning job,” she told me. I asked her about deaths. She shrugged her shoulders too easily, “It’s part of the job.” She made her point clear, though it’s hardly ever framed in such explicit terms. En masse, it is believed that laborers belong with their labor, and that even in death, the two remain companions. They become a singular entity with a singular role—easy to disregard, and eventually, erase. The UAE’s laborers are magicked into non-people by the state. They become objectified—true emblems of industry with single, non-contradictory uses. A cleaner cleans. A builder builds. A welder welds. The lives of the laborers, hyper-stratified into the various uses of government enterprising, are invisible. Only their output is recognizable. And so, a builder only builds, only watches builders build, and only knows other builders that build. The treatment of the labor class boils down to this: a laborer is not a man. What is the ontological status of these men within state ideology? If a man is not recognized as a man, but as a laborer, what happens when there is no labor? The truth is brutal. A 2020 article from The Guardian reported that many companies refuse to pay the men’s rightful wages. And even when wages are paid, most money earned by laborers in the Gulf is sent to family members as remittance. When there is no labor, most workers become bankrupt and struggle to return to their home country. However, the state projects its own reality. For them, the labor class is not a legitimately impoverished class, but a virtual class. Think of a role-playing video game. The player walks into a tavern and interacts with the barman. The player is prompted to leave the tavern and explore the house next door. When the player leaves the tavern, the barman does not continue with his own life, as a ‘real’ person would, but instead becomes idle; his code exists, but it is dormant within the program until the player walks back into the tavern. Now imagine this logic applied to living people, and taken a conceptual step further. In the UAE, the virtualized labor class is not just ‘dormant’ when the main player (the public eye) moves away, but is promptly erased from the lived reality. In the

(

)

most extreme sense, the labor class is metaphysically ripped out of the public facing ‘reality’ (which of course, is closer to ideology than the capital-R ‘Real’). As the proverb goes, “out of sight, out of mind.” The state doesn’t just make these workers non-people in their labor; it demands that they do not exist at all. How is it possible to control a population with this level of dexterity? Where is the outcry against this control, and why is it not widespread? The simple answer is that an advanced surveillance system, a silent secret service, and the non-citizen status of 88.5% of the UAE’s residents work together to disenfranchise the population and prevent dissident organization. Control, facilitated through these measures, is a distinct ideology in the Gulf. In the Theater-State, the lines of truth are constantly redrawn by misdirecting and modifying the Real. The labor class is erased, and becomes irrelevant in state-sponsored questions of ethics.

“The state doesn’t just make these workers non-people in their labor; it demands that they do

not exist at all.”

It is the Theater-State, which can pull set-dressing on and off stage with hidden hands, decorating its world with façade objects, bookshelves filled with blank book spines and lightswitches without lights, that can truly control its people. It is important to specify the kind of theater that forms a paradigmatic connection to the Theater-State. The particular kind of theater that desires to tell the truth while also suspending disbelief in the state-sanctioned narrative can be interpreted through Stanislavskian Naturalism. This method begins in an actor’s ‘true’ (i.e. lived) memory, and ends in the staged ‘true’ (i.e. identical to real events, but re-enacted on stage) performance of the playscript. Contrary to the normative claim that theater is in some way an unreality, the Stanislavski System emphatically presents a theater that advances consistent truth-telling in almost every step of the dramaturgical process. Almost. To actually perform a Stanislavskian truth and get from a truth-memory to a truth-performance, the former needs to pass through the rhetorical grammar of the theater. This is an aesthetic misdirection of the Real. And through this transition, truth is distorted. It remains a truth, but when framed around the particular aesthetics of the stage, it becomes a selective and incomplete kind of truth, a truth-performance. The Theater-State functions in precisely this way. It takes the truth of a state-memory, aesthetically modifies it into a performance-truth, and, in the process, erases the labor class.

To understand the aesthetic misdirection of the Theater-State, let us turn to an early Stanislavski exercise: the resurrection of an emotional memory. An actor is asked to retrieve a memory from his own

past provoking an affect similar to the character’s. The intent of the exercise is not to perform from pure invention (that is, under the imaginary circumstances of the playscript) but to draw from an actualized memory. But he does not relive this moment exactly. Of course, if an actor truly did this, he might derail the performance with stories of his childhood friends and aging father. No, the memory must go through a final exit transformation to become theater—it must be aesthetically modified. The actor must parse his memory through the grammar of the stage, the playscript, the pocket-watch in his jacket, the writing desk. Only then does theater begin.

The Theater-State understands that to transform a national narrative, you must do something like Stanislavski’s exercise. The state has a playscript. It reads: “the labor class is appropriately erased, and is irrelevant to the national story.” But in order to actualize this, the state recalls a true memory: the smallness of pre-oil life. A little heavy on the nostalgia but close to lived experience, the memory goes like this: before the petrodollar, there were simple fishermen who understood hard work. There were pearl divers who struggled against the sea, and Bedouins and tribes, who, less than a century ago, were living under British rule.

While I was talking to Emirati attendants of a public literature event this summer, the topic of the exploited South Asian labor class was broached. The Emirati attendants struggled to respond to direct questions, and focused instead on personal narratives; their state memory was a starry-eyed vision of wonder, modesty, and honor.

But while the Emiratis spoke of ancestral humility, it was impossible to avoid that the air reeked of hard cash. They were incredibly affluent people reconciling their extreme affluence with the state-informed identity of a noble but impoverished people, the hard workers who “pulled themselves up by their bootstraps.” That they have learned to resolve these oppositional narratives is a testament to the innovation of the TheaterState. It aesthetically misdirects—takes the Emirati social memory and pushes it through the aesthetics of ships and planes like quick costume changes, petro-set dressing dropped onstage in an instant.

When the Emiratis were asked, leadingly, who they thought was responsible for the perpetuation of labor exploitation, a well-meaning participant replied, “We [Emiratis] can’t all be responsible, we [gesturing to the South Asians and Emiratis] lived together peacefully in the ‘80s. My grandfather grew up on Indian songs!” Other participants told stories of modern life, saccharine but true stories of the country: the crime rates are low, the response to COVID-19 was efficient, public transport is clean… The list is inexhaustive. Criticism of the state had all but disappeared. And with it, the discussion about labor life was erased, and replaced seamlessly with the exalted narrative of kind, grandfatherly authoritarianism. When Oiligarchs are forward-looking people with hearts rooted in ghaf trees, there is little need to disprove the obscene cruelty against the labor class. It has already disappeared offstage, rolled away by the peaceful hand of the state.

II. Tenderness in the Time of Oiligarchs

So far, I have written out a structural narrative of what I call the Theater-State, which explains the systemic exploitation of laborers. I have explained the Emirati non-response to calls for accountability. All this is a preface to the real reason I am writing this: home videos.

I’ve been looking into the mass exodus of Emirati residents from homes in Ru’wais. Ru’wais is a city in the Emirate Abu Dhabi that houses the Ru’wais refinery—the fourth largest oil refinery in the world.

Like other refinery cities such as Dammam (Saudi Arabia) and Port Harcourt (Nigeria), it is a total institution of oil. The sole economic driver of the city, the refinery, is controlled by the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), with dominion over all housing, educational institutions, and hospitals. ADNOC has a monopoly over Ru’wais. While researching the city, I noticed that the Emirati exodus was contrasted by a fast-growing labor force. And it was here, looking through old YouTube videos of Ru’wais, that I found a collection of publicly accessible home videos made between 2005–2012 by its laborers. In a city so emblematic of absolute state control, the voices of laborers celebrating the wholeness of their humanity is powerful. One video depicts an Onam festival: Indian men laugh together, distribute food, and greet each other with open arms. In another video, an older man sings a beautiful Sufi song while other men sit and listen attentively. Contrary to the state narrative of non-identity and to the sensationalized images reproduced in the West, these videos show honest moments of rest, play, and care. Witnessing the enduring love of a community in exile, particularly under the eye of a state that negates their humanity and mechanizes their body, is profound. What are these videos? Documentary? Revolutionary? Public or private? I would, at the very least, avoid naming them with art-making classifiers. These videos are not ‘art’ or ‘art-objects.’ Attaching these tags to the videos, videos which are economically and socially alienated from the lexicon of high culture (and the modernist tradition of appropriating low culture into high art), misrepresents these men. My intention in writing this piece is to, as much as possible, allow these men the space to be self-determining individuals. I don’t want to evaluate them, even with the fairly esteemable titles of ‘artists’ or ‘filmmakers,’ for fear of replicating the same kind of discourses that bar these men from determining their own identities. I watched these videos many times after I had first found them. Each time, I was struck anew by the radical fact that these videos do make a dent in the totalizing narratives that can (and have been) forced on them. Totalizing narratives that are undermined with tenderness, honesty, and warmth. But undermining state narratives is not comparable to retaliation, revolution, or militant response. These videos cannot be mistaken as a fight against authoritarianism. The sad truth is that nothing materially changes when these videos are made. Although the videos hold conceptual power, the lives of these men—and the associated horrors of their labor—continue. Despite all the dignity that is revived by the openness of these videos, the violence doesn’t stop. But the importance of these videos can be summed up this way; as violence continues, the men are not erased. They play. They rest. They die too, and their deaths are the unforgivable results of inhumane policy. To me, these videos say something along the lines of: we are not men made to die.

c It was, by most accounts, a quiet Election Day. By the time the booths closed on Tuesday, September 10, just 10% of Rhode Islanders had cast their ballot in the state’s primaries, down from previous cycles. Voters, some experts said, had little reason to be riled this year; over half the races went uncontested—the highest share Rhode Island has seen in a decade. With the exception of Kelsey Coletta, a progressive candidate who edged out State Rep. Edward T. Cardillo Jr. (D-42) by a margin of 28 votes, incumbents held their ground.

Some pundits have attributed the lack of competitive races to a slowdown in the “progressive insurgency” seen in the years following 2016. Georgia Hollister Isman, the New England Regional Director of the Working Families Party (WFP), a progressive political party that backs “people-powered candidates,” offered a more optimistic view: “This year we were doing a fair amount of defense. Organized conservative and establishment Democrats came after a couple of Working Families champions. Defending those incumbents is actually a really important victory, even if it doesn’t increase the numbers.” Of the five WFP candidates up for re-election this cycle, all faced challenges from establishment Democrats, and only one lost their primary. “Progressive solutions to issues are actually popular,” Hollister Isman said.

Perhaps the best testament to the resilient popularity of progressivism in Rhode Island lies in District 58 (Pawtucket), where State Representative Cherie Cruz, one of WFP’s endorsed candidates, won her primary by more than a 20-point margin. Defeating an opponent with a mayoral endorsement, Rep. Cruz proved her constituents’ trust in her policy record, which has centered largely on housing justice and criminal legal reform. Last summer, she passed a bill that banned rental application fees, and another that requires landlords to be transparent about hidden rental costs. Three other bills she introduced—but were ultimately held up or struck down—would have expanded rental tenants’ access to legal representation, prevented tenants from being evicted on groundless or unreasonable claims, and required that landlords pay interest on their tenants’ security deposits. She has also pushed for automatic expungement of certain drug convictions and improved ballot access for eligible incarcerated people.

These solutions are not only just and popular, but are rooted in Cherie’s own experience growing up in Pawtucket, grappling with some of the same injustices that she fights against today. Growing up, Rep. Cruz’s family was often on the verge of eviction. She and her relatives have also been entangled with the criminal justice system: her father was shot in the back by a police officer as a young adult, her mother gave birth to her older brother while incarcerated, and Cruz herself was falsely accused of possessing and selling drugs, leading to a felony conviction that was later expunged. She was also arrested in court for refusing to testify against an abusive boyfriend, saying that he needed help, not prison time.

In the face of these obstacles and more, she never stopped pursuing formal education. After the birth of her first child at age 16, Cruz briefly enrolled in high

school, participated in the Brown summer program, earned her GED, and graduated from Brown twice, first as an honors RUE student and later as a graduate student in the Urban Education Policy program. (She already knew the university well; her teenage years saw her working in Brown Dining Services at the VDub). She was organizing with the Reclaim RI and the Formerly Incarcerated Union of RI, which she co-founded, when she was approached by the Working Families Party about running for office.

In our hour-long conversation, Rep. Cruz spoke with us about the tensions between activism and the electoral system, shared exclusive stories of the corruption that still defines Rhode Island’s politics, and offered hope for the triumph of people over power.

Indy: There is, both at Brown and more generally in progressive activism right now, a push towards working outside of electoral politics. People have not seen the results they want from that system; they don’t feel represented in that system. Because you have worked both as an elected official and as an activist, how do you imagine the relationship between those two spheres at a time when they often come into conflict?

Representative Cherie Cruz: Well, electoral politics is a game. And it’s self-serving. So I don’t subscribe to it. I’m there [at the statehouse] not to move up on the political ladder, but to bring the voices of the people who don’t have the access to that platform. One, to help them get access by bringing them to the State House, but also to use my position to make sure they’re heard, to make sure that [my colleagues] can’t ignore it.

Lobbyists know to walk the other way when I come because I don’t want to hear it from them. But if you’re somebody who’s been impacted in the community, I’m going to reach out to you. That’s the person who I’m going to invite to speak, to come to a committee, to get their feedback on a bill.

The landlord lobby—they were huge up there. They came, they even got involved in my race. The Grebien machine in Pawtucket, with [Mayor Grebien] and [Senator Sandro Cano], backed someone [Elizabeth Moreira] who moved in, several months before the race, to run against me. And a good chunk of her donations came from those landlords who came up and testified against those tenants’ rights bills. [Cruz shared with the Indy a letter addressed to Moreira that was sent automatically from Cruz’s office to voters that had just moved to the district. The Secretary of State’s filings additionally show Moreira’s address in Providence as of June of this year.]

Indy: When you say “move in several months before,” do you mean literally that she moved to the district?

Rep. Cruz: Yes, used the address. And nobody would move with a brand new Mercedes truck and who has good money into one of the poorest districts or streets in my community where I grew up. There’s no way, unless it was

( TEXT CAMERON LEO DESIGN JOLIN CHEN

ILLUSTRATION SOFIA SCHREIBER )

to run. And I was warned it’s coming. They threatened me, like, eight months before, We’re gonna find somebody, we’re gonna move them in.

Indy: In what respect did they threaten you?

Rep. Cruz: Well, the first threat I got from the mayor is ’cause we fought to save Morley Field from becoming a parking lot. A distribution center with over 300 diesel trucks. And he said, You said I was on the take in that article, you should have never come after me.

I said, I never said that you were “on the take.” You were getting campaign donations from this out-of-state developer, and now voilá. They’re buying the property and you gave them a tax stabilization agreement that’s transferable. These are facts. If you think that’s what it is, you’re on the take, then you said it, not me. So he got upset and was like, We’re all vulnerable. And I heard again that he’s looking for someone to move in to run. [Mayor Grebian declined to comment on this article.]

I’m an independent voice. And that is very

“If you’re going to be an independent voice, you’re going to need the power of the people behind you.”

much frowned upon in electoral politics. So to bring it back around: organizing is important because, if you’re going to be an independent voice, you’re going to need the power of the people behind you.

Indy: You’ve helped pass a large slate of progressive policies. You’ve also touched on how important forming relationships with other legislators has been to that success. Can you speak more about how that relationship-building has worked on the floor?

Rep. Cruz: It’s really just focusing on the issues. What I found is [people are] like… Oh, you’re progressive… I try not to use labels, because it kind of puts people’s defenses up. And so I came in like, What’s that? I’m here for working class people, people struggling to survive, people trying to find housing, who can’t pay for their prescription, who can’t pay their utility bills… people who have old [criminal] records, who want second chances so they can live and work in Rhode Island and they don’t have to leave. So when I just talk about those things, the issues, I find that people are willing to have those conversations, whether they’re conservative, Republican—it doesn’t matter. I don’t walk around with a big ‘P’ on my chest. I just want people—can we talk about people? And usually that’s when [legislators] open up.

Indy: You focused your primary campaign on reaching out to folks who may not have voted in a long time. Voting rights is also at the center of a lot of your legislative work. What do you say to someone who is fed up with the electoral system, who doesn’t want to vote, who doesn’t believe that it matters? What about people who have faced other external obstacles to voting?

Rep. Cruz: I always hear it in politics—I don’t vote because they all lie. They all cheat. It’s this club that nobody can penetrate. And my response to that

is, you’re right, I feel the same way. I think they all lie too, and honestly, I wasn’t thinking about running either. But isn’t that why we should run? Because if we know they’re lying, then we need more everyday working class people like us, who don’t give a crap about titles, or moving up some ladder, but about helping our community.

People always ask me, What do I need to run? I’m like: Be from your community, care about your community, be ready to work for your community. That’s it. You think you need degrees or anything? No, those are the three things that matter most.

In my district, someone won by one vote [in 2012]. I love to tell that story. People’s eyes light up when they realize, Wait, you’re saying I can choose—my one vote or my household can actually pick who represents us.

But some people have other perceived barriers to voting. In my first race, we had people register to vote that thought they couldn’t vote because they had a past felony conviction on their record. I’m like, no! As someone who knocked doors back in 2005 and got my right [to vote with a felony conviction] back in 2006, to hear that almost 20 years later, people still think they don’t have that right?

In my district too, if you’re unhoused, and you don’t have a residence, you can use City Hall. City Hall is my district. So we can register people and then they can vote. That’s a big one too, and people didn’t realize they could do that. They can be a part of the process if they are unhoused.

Indy: Returning to the person who moved in and campaigned against you in the primary, and thinking about that story more generally in Rhode Island—there’s been a recent slate of these wellfunded primary attacks from the center, against (and I know you want to avoid these labels, but for lack of a better word) progressive candidates. What is your take on why this is happening? And what has your experience been running against that kind of power?

Rep. Cruz: Why do I think it’s happening? Well, people want to maintain the status quo. That means it’s working for them, right? And when I say “them,” I mean the people who are making the money, the people who have the control. But it’s not working for the diverse working class community in my district.

When I first ran in my first election, I was told, especially with this Pawtucket machine, to be careful. There are things like the “Mean Girls club”; they’re going to come after me and do character assassinations.

There were threats that they were going to out me on my past criminal record. And I came out with it. And you know what? My thing was, go ahead, because in my district, we’re the second highest in the state with people impacted by the criminal legal system. So what you’re going to do is basically tell the people in my community who vote who have these past records that they’re nothing too.

The second time, they used attack ads because I voted against a bill that superintendents brought that wanted to give felonies to children in schools if they made a threat or perceived threat. They had an attack mailer that said I had turned my back on teachers.

I have a background in education; I care about education. I studied, here at Brown, the schoolto-prison pipeline and policies to end it. And this was clearly a school-to-prison pipeline bill.

When I first saw that bill, I called family members who are teachers. My brother’s a teacher, my daughter works in a school. My nephew is a counselor at Mount Pleasant. They were like, Who the hell would write that bill? That’s insane. Why would you do that to kids?

And when I heard the bill in committee and when it made it to the floor, I asked: Wait a minute, does this include, say, a 10-year-old who said, You know what, teacher? I’m going to see you outside. Wait ’til I get you. And the sponsor said, yes, that’d be a perceived threat. And I said, well, for that reason, I’m voting no to this. And then they threatened me that they would use that vote against me in the primary. Legislators were telling me that Pat Crowley, secretary-treasurer of the AFL-CIO who was pushing the bill, was pissed at me and was coming for me in my race. [Neither Pat Crowley nor Representative Thomas Noret, the sponsor of H 7303, could be reached for comment before publication.]

But we won our last election, against a candidate that was backed by the mayor. In my first race, there were four of us running, all new candidates, and I won by 43 votes. But this time I won by close to 200. That says I might be doing a good job.

We need more people to run that are strong in

their convictions and aren’t easily swayed by “this is how we do things,” because when we say that, it’s really code for the status quo. They’ll try to tell you that this is the “game.” This is how you have to do it. And I’m like, well, no it’s not, I’m not going to play that game, people’s lives aren’t a game. I got a new game. We’re going to play this game, all about people. But you gotta be really thick-skinned, and that’s why you’re going to need a lot of your community behind you as well. You can’t do it alone. Indy: How much of these challenges for progressive candidates do you think are specific to Rhode Island and the political machine that it has been historically, especially in Providence and Pawtucket? Rep. Cruz: I think the biggest challenge is our politicians, they are entrenched. They’ve been there for decades and decades. We’re a small state. And a lot of times it’s a cesspool, meaning they’re related. They’re friends. They’ve done dirt together. So they have these allegiances together. Somebody’s related to somebody, or got their start from somebody—so they owe them for life. I ran not connected to any politician. The mayor [of Pawtucket], he’ll have a slate he endorses. Well, then they’re beholden to him. For life. And it shows in the way they vote. You said you were gonna do X, Y, Z, but you did none of that, and you don’t actually care as long as that mayor endorses you, which is really sad. Our politics are so entrenched. People have been there for decades. And that’s a challenge, right? To unseat an incumbent. And then also the money they accumulate through each incumbency. And the other challenge is, we don’t challenge people. Like, there’s so many [representatives] up there, especially in Pawtucket, that are never challenged. They just walk into their seats. And when they walk into the seat, they accumulate money, they accumulate that power and status, they move up that ladder, and it makes it harder for somebody new coming in to take on that machine.

[State] Senator [Sandro] Cano just stepped down, right? Stepped down, coincidentally, in this three day period where they can appoint someone Senator and circumvent the democratic process. Which is insane. They picked someone who was the campaign lead of the mayor... So this is someone fairly new living in Pawtucket. She actually sat, I think, one term in Westerly Town Council. You can’t get any more different from Pawtucket than Westerly, right? Her main claim to fame is that she was the mayor’s campaign manager? You see people one day

working on a campaign, the next day you see them in high level state jobs or political positions. And they come out of nowhere. I see it in the Treasurer’s office and the Mayor’s office, and this is no different. I’m like, wow, they didn’t get the vote of the people, nobody elected them, and here they are because they worked on the electoral machine’s campaign.

That’s Rhode Island. That’s why it’s difficult—it can be—for someone progressive to come in. Because the way it’s been happening is you had to link on to these old machines, or at least people thought they had to, in order to get into office. When the reality is, look—I just did it, and there’s others who have done it [a different way].

Indy: In that vein, can you speak about your endorsement from the Working Families Party?

Rep. Cruz: Yay! Oh my God! I meant to say it sooner in one of my little rants, because I couldn’t have run without them. I couldn’t have run unless I had an organized machine of my own to take on this entrenched machine. And I think any progressive candidate could not run without having that.

When we talked about Tammany Hall [in a lecture at Brown], and the Daley administration in Chicago and all these old political machines, that is Pawtucket. It’s Pawtucket. It still is Pawtucket. It’s entrenched there. So I knew I needed the Working Families Party, needed that organization, people experienced in elections and running candidates, and it felt good with them. And then also doubling with Reclaim Rhode Island with added bodies on the ground, because we didn’t have the money. We have the people. And that’s what was needed to counter the money.

When I met them, there were other groups reaching out to me at the time. I was like, how did my name come up as running for office? But I guess they saw me at the State House and advocating, and they were like, You should run. And I remember meeting with WFP a bunch of times more than a year before the next election and I was like, no, you’re crazy. I hate politicians, they lie. And they’re like, That’s why you have to. And I’m like, wait, do I have to change who I am? ’Cause I’m pretty outspoken, I like to fight. I’m from Pawtucket … I got a past felony … I was on welfare, I lived in public housing. They were like, We don’t want you to change at all. Just be you.

CAMERON LEO B’25 hopes you’ll vote in your local election this fall.

c Ma comes home with a plastic bag the size of a melon. Heartbeats, she says, will have to do. We don’t have all day. I climb up onto the counter to help with the job, and each beat is warm and soft, too soft to hold for any longer than it takes to bring it to the ceiling.

Around the overhead light Ma installed last winter with nothing but a ladder and a plastic tube dislodged from the bathroom sink, there is a large ring of mold. Like a bad rash, the fungus blooms in hot, purple circles. It has been leaking for two days.

We layer the heartbeats neatly over it, each one overlapping the next. Of course, Ma does it better than I do. She wraps her arms around me from behind to help, and in the motion, I catch a glimpse of her brother, teaching me how to move puppets behind a veil to some other world. He smelled like a teenage boy, had the air of one too, so I was probably just a baby, barely conscious and already disagreeable. We were at the tacky pop-up show in front of Zhōngshān Líng, the shadow of the mausoleum slanting over us. I am about 40% sure it was a dream.

By the time we are done, the ceiling is no longer leaking and looks only half as ugly. Somehow even the house understands—Jiějie is coming home from college tomorrow, the first time in two years, and we cannot let her down. Ma sighs. She rubs her hand in tight circles on her cheek, a gesture she picked up five summers ago, the year the kitchen flooded and Jiějie decided to chop her hair to her shoulders.

Ma returns the empty bag onto the hook alongside the others. They all have the same filmy green hue, picked up during runs to the local fruit market and since repurposed for the transport of Ma’s tools. After Jiějiě called that she was coming back, Ma’s trips outside grew increasingly frantic, each day’s finds pouring out of bags that dug thin white strips into her forearms, every part of the room suddenly in desperate need of repair.

I take my seat at the very end of the table, at the edge with the short leg that lags behind the rest. The corner pokes directly at the soft emptiness between the two wings of my ribcage. Over dinner, Ma and Ba argue about the missing chunk of the leg as the steam from the rice cooker wafts across their faces. You sawed it off to fix the loose door, Ba says, don’t you remember? Even though she does not move, I can feel Ma’s frustration washing over the house, lapping against every stone and limb and piece of hair. Are you batshit crazy? It stops, right behind my ear, and I let it crouch there for a moment, until it fades into something less than a whisper.

Ma says the house is always broken because it used to be a hair salon. Long ago, long before she had met Ba and it was just her and her seven siblings in the house, they made the side room—our living room and kitchen—into a local business. When Ma brought Ba back home, the mountain boy from Húnán that not even a country girl would look at, they begged and begged her brothers for a place to raise their daughter. Eventually, they were given the salon. No kitchen, just four walls and a lot of hair thinned to dust.

Before Ma started collecting things, it was a project of transplant: pillow sheets for curtains, a slab shaved off of the wall for the cutting board, the edge of a table leg. Then, gradually: a copper goose with a long neck for an oil shoot, monk’s shadows for lampshades,

tadpoles for paperweights, heartbeats for plaster. In a strange way, the kitchen is always spinning, nothing ever truly itself until it becomes something else.

After dinner, Ma runs a hot bath for my feet in one of the helmet-sized dryers that once gave all the ladies on our street dark, knotty perms. From my spot on the couch, the same one where Jiějie got her last spanking and Ma and Ba made first love, I can see the rest of the house through a hole in the wall, peering into the rooms that now belong to the uncles and their families. I don’t know how it ended up there, only that I used to be small enough to climb in and out of it. Ei, Ma would say, if you do that one more time, a part of you will get stuck in there.

( TEXT ELENA JIANG

DESIGN KAY KIM ILLUSTRATION BENJAMIN NATAN )

Probably brushing up on Wǔhàn. Then Jiǔjiāng.

DREAM BOY

Maybe deep in a tunnel somewhere.

MA Yes, or high up on a bridge.

Beat.

When no one was looking, Jiějie would drag me to the hole to ask the uncles for food, back when Ma had not yet finished the kitchen and was not on speaking terms with the family over ending their business endeavor. We would end up with fringe portions of air-dried sausage, sometimes as long as my arm but never quite as wide. Because you are a boy, she would say, to which I would say, No, because there are two of us now. Jiějie and Dìdi.

Beside the bath, Ma is looking at me with the eyes she gets in the evenings slumped on the couch, the same look she gave Jiějie when she announced she was going to university in Sìchuān to study English literature—as far away from this place as I can—and then again when we were at the train station and none of us were doing much of anything except staring at the ground, the crowd parting around our family like dough being cut by a knife.

I wiggle my toes in the water. Ma places a hand on my knee to keep me still, and I feel a sudden heartbeat sneak all the way up to my thigh.

Later, when I go to sleep, it is ba-bumping right behind my temple, and when I turn to my side and tuck my hands behind my ears I hear it echoing through the room, slipping off the walls, everywhere.

Ba-bum, ba-bum. Ba-bum, ba-bum. +++

Beat.

Lights up on a dimly lit housing duplex. It is shaped like the character 田, modeled after the historical Sīhéyuan, and we are focused on the room in the upper right corner. A BOY (10, Asian, scrawny) sleeps on his side. MA (40-something, Asian, kind) sits on the couch, her head propped up by her hand, her feet resting in a plastic bowl full of water. It has gone cold, so she is rubbing one foot on top of the other intermittently.

DREAM BOY (10, identical to the Boy except with a slightly effervescent quality) appears beside Ma. He paces, restless about something, and then takes a seat beside her. The room shrinks around them, which is to say that Ma and Dream Boy are growing.

MA

Dìdi, do you think she will like what we’ve done to the house?

DREAM BOY

Not just like, Ma. Love.

He throws her a glance, as if to say, What a stupid question.

DREAM BOY (con’t) She will love it very much.

MA

She used to complain about the kitchen all the time. Back when you were too young to remember. It was too dark, too dingy.

Dream Boy looks up to a sound, and DREAM GIRL (10, Asian, with a bob) enters through the hole in the wall. Ma cannot see Dream Girl, and it is as if the room has been split across two planes of existence that appear seamlessly overlaid on one another, in the same way the childhood photos of a mother and daughter tend to look so impossibly similar. Dream Girl kneels by the wall, crying softly.

DREAM BOY

Why are you crying?

DREAM GIRL

Because I will miss my brothers when they go off to college.

Dream Boy peers into the hole in the wall, in search of these brothers, but everything is blurry and indecipherable.

DREAM BOY

But they will come back. Won’t they? Like my Jiějie. She’s coming home tomorrow.

DREAM GIRL

I think so. My Ma and Ba say these rooms will be theirs when they grow up. One for each of them.

Beat.

DREAM BOY

Ai ya. (Dream Boy playfully nudges Dream Girl with his foot.) Cheer up.

Dream Girl gets up and wanders to the kitchen, looking at the light. The heartbeats emit a warm, gummy glow. They look like stars.

DREAM GIRL What are those?

DREAM BOY

Heartbeats my Ma brought home to fix the leak.

DREAM GIRL Can I feel them?

DREAM BOY Mm.

He takes one off the wall and slips it into her hand, milky orange and perfectly circular.

DREAM GIRL Wah. It’s still beating.

DREAM BOY Cool, right?

DREAM GIRL Mm.

Beat.

DREAM GIRL

(remembering something) I need to go now. My Ma doesn’t like it when I climb through the wall.

DREAM BOY

Because a part of you might get stuck?

DREAM GIRL Exactly.

Dream Girl slips out of the room. At this predawn hour, it is all of a sudden obvious how strange and small the place is, how stubbornly they have outgrown it.

Dream Boy scans the room, yawning. He halts at the sight of the heartbeats. There is one the one Dream Girl returned mere seconds ago shining brighter than the rest.

FADE TO BLACK

I wake to the doorbell ringing and Ma’s footsteps rushing to the door. I scramble down the hall to watch from behind, self-conscious about the ways the two years have rooted between us. I keep my gaze on Ma so intently that she blurs, spills into the moment, cuts back into focus. She looks so much younger, as if she could pass for a girl, her bob tucked behind her ears in the same way she wore it decades ago. I swear I must have seen a photo somewhere. When the door opens, it is almost impossible to tell who is Ma and who is Jiějie, who is growing up

and who is growing old. It is all fog and sunlight, and when she comes over and wraps her arms around me, the heartbeats in my ears are so loud the whole room shakes.

Breakfast is pídàn shòuròu zhōu, Jiějie’s favorite. She stands in the kitchen, hovering behind Ma as she busies with portioning the congee into bowls. The sun passes through the window at the perfect angle, and from my spot at the table, the heartbeats pulse in halos above their heads.

Later, Jiějie will discover the tadpoles on the desk, the soft humor of each lampshade. Ma will run the hot bath for her three times over before she says, You have my Ma’s eyes, did you know? They looked so familiar when you walked in the other day. Jiějie will recount this to me as we lie awake in bed, our toes still warm and pruned, listening to Ma enjoy the first good sleep she’s had in a very long time.

The thing about our spinning room is that it is so easy to twist your ankle in a crack, and all of a sudden you are tumbling down the arm of a dream, glimpsing the turn of the corner a beat too early or a lifetime behind. I’m getting ahead. Right now, Ma is singing the song for good days, the one they played in the salon every time someone opened the door. I hum along. Swaying to the tune, Jiějie tilts her head upwards to admire the heartbeats, her hand reaching up to brush the brightest one.

ELENA JIANG B’27 is scared to write a full screenplay.

( TEXT LUCAS GALARZA DESIGN ASH MA )

c Learning how to write by hand is an exercise in consistency, repetition, and imitation. Children mimic the stroke order and form of the giant computer-generated glyphs glued up at the front of the classroom. Orphaned lines and curves slink slowly down the worksheet page until they bear sufficient resemblance to the components of an ideal letter. The printed word presides, preaching conformity—each student assessed on their ability to create in its image.

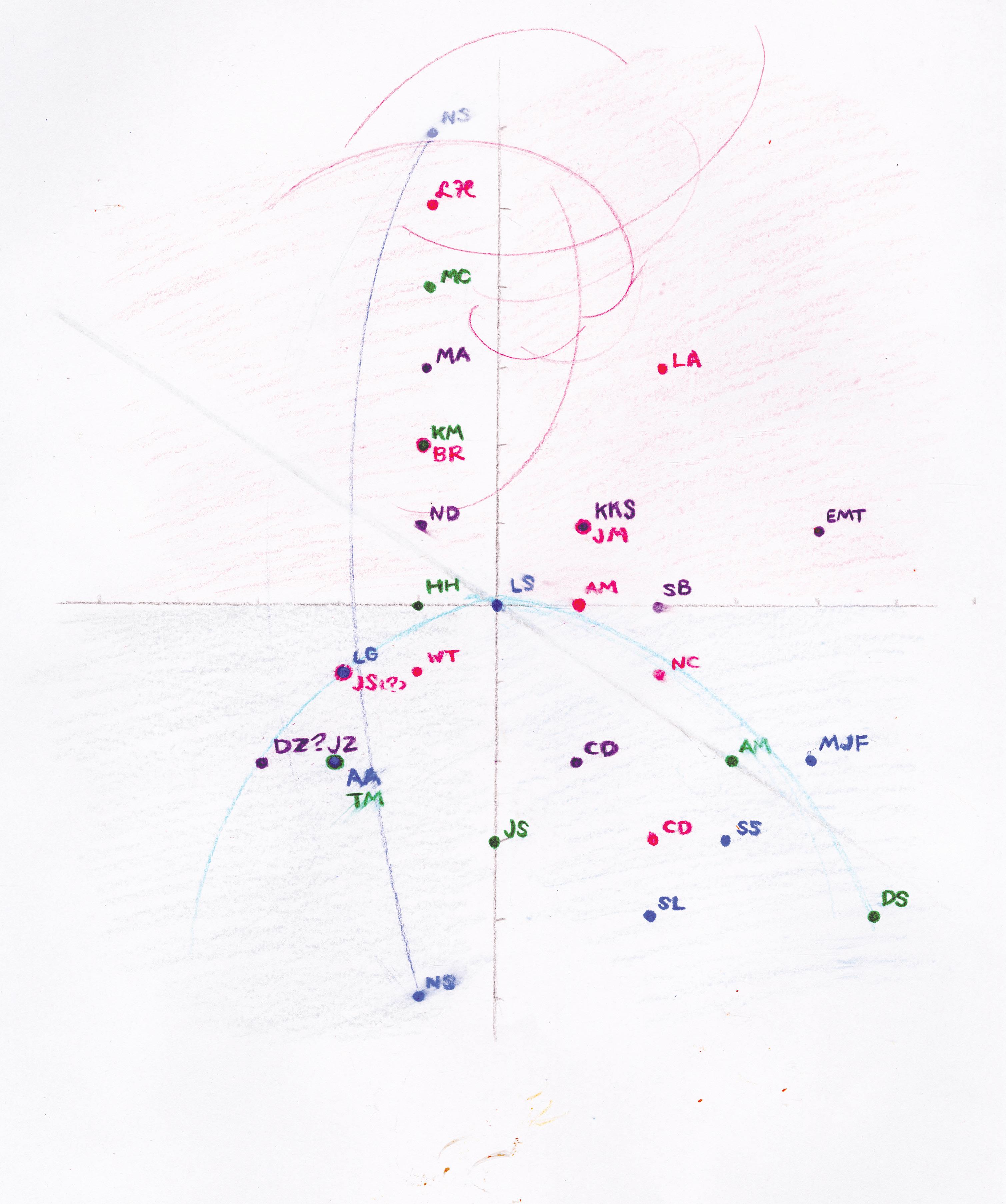

Graph based on 30 handwriting samples taken from random students around College Hill.

In fourth grade, I had a crush on a classmate who wrote her lowercase “d”s as a single looping stroke, a casual rejection of the tailed, bipartite “d” we had learned in class. I remember very little about her now, but I couldn’t forget that rebellious “d” even if I wanted to—I practiced it until her handwriting became a small part of my own. Our “d” was almost edgy, an alternative design that made everybody else’s version look uptight. It flowed effortlessly into the next letter. At some point, though, it stopped being ours and just became mine.

We are collectively fascinated with the idea that letters might contain a bit of the person who produces them. People collect autographs and forge signatures to claim ownership over a small part of someone else’s identity. Some graphologists claimed to be able to identify insanity and predict criminality with only a writing sample. Even today, we have a tendency to make wild assumptions about people based on their handwriting. During my research for this piece, passers-by would scan my open notebook page, pin their finger on one sample or another, and make a

● NS (-1,-5) or.. (-1, 5)

face. “This person is a literal child.” “God, I wish I was that put together.” “She seems fucking crazy.”

Many people reacted to good penmanship with contempt. The authors of these “nice, but boring” samples were perceived as conformist, ordinary, “trying too hard.” The experience of struggling through cursive in elementary school might be to blame for some of this resentment. But the vitriol directed toward rule-followers, as well as the praise showered on those with a more unique style, demonstrates the real importance people attribute to handwriting. Handwriting is not simply a reflection of the self but rather a place where the self is negotiated and created. Each word we write is a battleground, the site of constant struggle between the individual and the collective. If our handwriting differs too much from the standard, it is illegible, and worthless. How forcefully, then, can we assert our personhood, if even the most radical calligrapher is bound to reproduce a predetermined form?

A perfect example of the difficulty of giving a flowery rating. This sample is striking, certainly. Its squat, long letters are distinctive: this was the most commented-upon sample in my study. Its uniqueness makes it relatively hard to read, since letters like ‘n,’ ‘c,’ and ‘r’ are almost fully horizontal lines. But the overall effect is quite beautiful. It feels futuristic, streamlined; an elegant script for a more civilized age. I can’t help but wonder whether it’s actually faster to write.

● TM (-2,-2)

Here, words are very tightly constructed, their letters almost always touching. But each word is spaced so far from the next that the whole sentence takes up the same space as the others. The starting ‘T’ almost seems to collapse under its own weight, as does the ‘K’ (大?). Tailed letters have fat heads and piddly tails—they’re tadpoles—causing ‘b’ to look like a 6. ‘Z’ is crossed, ‘r’ is hastily composed with a down-up-right motion that makes it look like a v. Interesting that the dot of each ‘i’ is a slanted, lengthened [ ` ] or [ ´ ] while the cherry on top of the ‘j’ stays round.

● ND (-1,1)

Sparse, scratchy writing style aside—and it’s difficult for me to put this aside because of how fascinatingly underdeveloped many of these letters are (‘b’? ‘h’?? ‘e’??? The 5 completely different ‘n’s??????)—this person wrote the wrong sentence. I was quite clear in my direction, so perhaps they made an explicit choice to disobey. Overall, this sample seems to paint an unfavorable psychological picture. Any true graphologist would have a field day.

● AA (-2,-2)

Contour Drawing on Raw Data

Perhaps not as illegible as the score would seem to indicate, but it’s just…so ugly. ‘Quickly’ is near impossible to make out due to the extremely vertical linear and chicken-scratchy lettering throughout–letters with horizontal heft like ‘e,’ ‘v,’ ‘c’ are often reduced into little more than a line. Whole letters disappear into others; the “ic” in quickly and the “rd” in wizards are as one. Loops often unfinished—the right side of ‘g’ is left open to the air, same for ‘q,’ ‘d,’ ‘o.’ Highly inexact—capital ‘T’ looks like a Christian cross. ‘Z’ crossed.

● MA (-1,3)

Fascinatingly overwrought ‘f.’ It looks like a flipped version of a cursive ‘z’. The stem of the ‘i’ curves rightward. Consistent, pretty loop in the tail of the ‘j,’ ‘g,’ ‘f’ (which here has a tail somehow), ‘y’; but the ‘q’ is very sharp in comparison—almost like a fish hook. ‘k’ has a bulbous forehead like a beluga whale. Letters like ‘l,’ ‘b,’ ‘d,’ ‘p,’ even ‘T’ and ‘h’ are ramrodstraight as they extend above or below the average letter. No crossed ‘z.’

I sometimes wonder whether my crush’s easy “d” was her own invention, or if she had just cribbed it from someone else’s summer reading report. Did she assign it some meaning, as I had? Adopting it, she folded its essence into her own, stretching and doubling it again and again till dispersed, to be meted out along with all the rest as inky scratches soaking into the blank page. c

(

)

And the Lord God said unto the serpent, “Because thou hast done this, thou art cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life: And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel.

-Genesis 3: 14-15 (KJV)

c Genesis seems the natural place to begin our story about snakes. It is, after all, a depiction of the beginning—of both life on Earth, and of death. In the third chapter a snake walks across the lush garden floor of Eden and tempts a woman into committing the Original Sin. The pair of them are punished: Eve will endure terrible pains in childbirth and be forever subservient to her husband, and the snake will lose its legs and eat dirt all its days. To make matters worse, all future generations of humans and snakes will be enemies. From then on, Man was destined to step on the head of Snake, and Snake was destined to bite the heel of Man.

It’s been six thousand years and the snake still does not walk. Older families of snakes, such as the Boidae and the Pythonidae, have two side spurs toward the end of their bodies that tell us their ancestors did once have legs. But rather than a divine curse, research suggests that the loss of these limbs occurred when a lizard made the decision to live subterraneously around 140 million years ago. We don’t know why the snake chose to live underground. What we do know is that approximately 66 million years ago, when 95% of all life on Earth died, some snakes survived. These snakes scattered across the planet and adapted to their environments. They became colubrids, boas, pythons, elapids, and vipers. And when hominids came on the scene 60 million years later, snakes started biting our heels.

“He must not bite you. Snakes—they are malicious creatures. This one might bite you just for fun…”

-Antoine de

Saint-Exupery, The Little Prince

In Anaconda (1997), a man—blonde, disheveled, sweaty—stalks about the deck of a riverboat with a rifle in his hands. It is night on a river in the Amazon, and the boat, with its rusted metal railings and water-damaged paneling, has seen better days. So have its passengers. The remaining members of a documentary crew stare despondently at the water or glare at the man with the rifle. His name is Gary, and he’s just betrayed these people by helping the grizzly Paul Serrone commandeer the boat to hunt the 25-foot anaconda rumored to live in the waters beneath them. Gary has been promised all the riches and fame he’s hungering for if this snake is caught alive. Unfortunately for him and the rest of the crew, the snake is just as hungry. It plans to hunt them right back. If you want to make a horror film about snakes, you could certainly do worse than choose the green anaconda to be your villain. They are large, aquatic creatures with swamp-green bodies and dark spots

down their backs. The green anaconda is the heaviest known species of snake, reaching as many as 550 pounds. They are constriction feeders, meaning they wrap their bodies tightly around their prey and squeeze. Each breath their victim takes in allows them to squeeze tighter. It is not strangulation or asphyxiation that does the killing, though—the precise timing of their tightening forces the unfortunate soul in their grasp into cardiac arrest. And their bodies are so sensitive to sound that green anacondas can sense the very moment the heart stops beating. But while anacondas are excellent hunters and formidable creatures to face in the wild, they are also slow-moving ambush predators. They sit and wait and watch. In the tall grasses of South America, these snakes lie low by the river bank with scales as reflective as the water. Going unseen is what the green anaconda was made for. Hunting is dangerous and expending energy is costly. Sometimes, a large female will only eat once a year. Like all snakes, green anacondas are ectotherms—their body heat is maintained not by the food they eat, but by energy from the sun. We humans, as endothermic, pathological eaters, can’t possibly know what hunger feels like to snakes. In real life, a green anaconda would have little interest in this riverboat and the drama occurring on top of it. It would swim away unseen, and perhaps snag a capybara for lunch after. Maybe it’s a desire to see the cruelest parts of ourselves in snakes that has transformed the creatures into the monstrous figures of our collective imaginations. In Anaconda, a member of the crew admonishes Serrone after the snake attacks them: “You brought that snake. You brought the devil!” To which Serrone says, “There is a devil inside everyone.” We look at the green anaconda, preferring to swallow animals one to two times the diameter of its neck, and say, ‘well, it must unhinge its jaw.’ That’s what humans who wished to do the same would have to do—be so driven by their hunger that they disfigure themselves just to sate it. But this is a flawed way of thinking. The skull of a snake is far more kinetic than yours or mine. Its lack of a fused upper or lower jaw allows them to open their mouths wide enough to fit around its prey without chewing or tearing. A snake’s teeth curve backwards. What appears to be a sinister mutation is just a clever solution to the problem of eating without hands. As naturally as you might yawn, a snake walks its mouth down the body of its meal. The eating itself is quite peaceful—no struggling and no screaming. Just a tail disappearing into a snake’s throat, and now a snake is back to watching and waiting. We make snakes into monsters like no other animal. They are the villains of our movies, our myths, our urban legends. I remember my sixthgrade science teacher told the class one such legend. I liked Mr. Stahl. He had a shaved head, thick beard, and pierced ears, which my sixth-grade brain read as a “punk rock vibe.” Every class began with a weird science fact. I was living in Louisiana back then, way out on a military base in the middle of nowhere that was Plaqamine’s Parish. There were a couple of times, in the high grasses just beyond Mr. Stahl’s classroom window, that the playground was evacuated when someone saw something slithering through the grass. I always wanted to investigate—in those years, I was much more rough and tumble. The most I ever

saw was muddy pits in the ground that the other kids swore up and down were snake holes. So when Mr. Stahl announced that he had a friend of a friend who used to own an anaconda that roamed around their house as it pleased, I closed my notebook and leaned in. Maybe this would be my glimpse at last.

“One night,” he said, his face wrapped in white projector light, “They noticed the snake lining up next to the bed of their toddler. Weird right? Well, they asked their vet about it and she said, ‘Get the snake out of that house right now! It’s measuring your small child, trying to determine if it can eat them!’”

The class was awash with hushed,

‘what?’s, ‘woah!’s, ‘no way!’s, and ‘then what?’s.

Mr. Stahl nodded and continued. “So they had no choice. They put the snake down.”

“What?! They killed it?!” Someone asked.

From another, “That’s so messed up!”

Mr. Stahl just shrugged and flipped the light switch back on. “It was for the best, guys. Thankfully they did it before something terrible happened.”

It’s the kind of gruesome lesson commonplace in early adolescence: survival of the fittest. As early as second grade, I had already started seeing the subtle battle for dominance inside every interaction. That happens when you already have points against you (new-kidness, blackness, tomboyishness). It was all about who had the funniest jokes, the wittiest comebacks, the best stories. I held onto this one like a snake holds onto its meal, like my life depended on it, because it did in a way. Mr. Stahl’s friend of a friend became my friend of a friend. I knew about snakes, my story insisted.

Of course I didn’t know anything. Sixth graders rarely do. I continued to know nothing until high school, when my love for snakes began. I watched a video of a black mamba zipping through a savanna. It moved like an alien, like a gray ribbon drawn through dry grass. It raised its body from the ground and there were its black eyes; it opened its mouth and there was its black maw. It struck at a field mouse and its whole body went down with it, coiling tightly around the small mammal and beginning to swallow it whole. It was my first time seeing an actual snake, not just the shadows thrown against cave walls or projected onto smart boards. I realized, watching this apex predator devour a mouse, that, more than scary, these creatures were entirely weird.

How else would you describe looking at the rest of the animal kingdom, with their legs and

their arms and their wings and their fins, and deciding you want no part in that? Snakes live lives of necessity, and they live them well. Making do with little, being excellently weird, and, despite everything, surviving. I can connect with green anacondas because I too have relied on camouflage. I know all about perfectly timed emergence. All I do is move slowly through this world and slither away from fights I know I cannot win.

Anaconda’s anaconda races through the brush much faster than its weight should allow, chasing after an armed team of six. It zips through an abandoned mill and spirals up a ladder in the blink of an eye. Within the movie, it feeds five times. Gary himself becomes one of its meals. The last we see of him is the impression of his screaming face against the belly of the anaconda as it curves away from the camera underwater. This is the price of hunger, the movie seems to say. By the end, the snake has fallen, burning, from the tall chimney of that old mill, and received at least three ax blows to the head. This is the price of being a snake.

“Never look in the eyes of those you kill. They will haunt you forever. I know.”

-Paul Serrone, Anaconda

The story of Snake often crosses paths with the story of Man. Man wins every time. Even the most recent family of snakes, Viperidae, has yet to evolve beyond humanity. With diamond shaped heads and girthy bodies, vipers are venomous snakes with highly sophisticated fangs. These fangs are large, and can be so large because they sit flat against the roof of a viper’s closed mouth. They swing out when striking and can move independently of each other, free to pierce in a wide range of directions. If you are unlucky enough to get a wet bite rather than a dry one (venom is a precious resource; the last thing a snake wants to do is waste it on something too big to eat), a dangerous cocktail of proteins from their venom glands will enter your bloodstream. The next few hours of your life will be extremely uncomfortable.

But the snake can always be picked up, shaken, and killed. As the saying goes, “They are more afraid of you than you are of them.” Biting is often a last resort, taken only when hiding and threat displays don’t pay off. When a rattlesnake shakes its tail, we like to think it’s saying, “Look at me! I’m big! I’m deadly!” In reality, it is far from an aggressive act. It is a plea for life.

So watching a viper rattle away at a man on a plane instead of hiding made me angry. That’s not the whole reason, of course. It wasn’t like I came to Snakes on a Plane (2006) expecting scientific accuracy. I was excited to see the absurd. At the very least, I was curious what the movie would make of snakes as characters. But very quickly Snakes on a Plane made it clear that it was not for someone like me. Before there was a single hiss, I was forced to watch women be leered at and fondled. An effeminate male flight attendant drew scornful looks for correctly identifying the color teal. And then there were the snakes. Diving for the faces, necks, and legs of the passengers. Choosing again and again to die rather than survive. In Anaconda, I was able to laugh at the questionable science and bad CGI. Here, I could only stew in my frustration as the movie threw these snakes at the screen like their lives meant nothing. It was horrifying. I kept wanting to look away. There are many animals that are weird. There are many animals that are good at surviving. But I think I latched onto snakes in particular because they are visually fascinating. So careful and so precise. It’s impossible to watch a snake slither and not see intelligence in its movement. It’s impossible to look into a rattlesnake’s eyes and not, somehow, in some way, hear it speak. Whenever I’m watching a nature documentary and a viper assumes the classic coiled position, I find myself leaning in, and trying my best to listen. Eve must have felt the same. We know rattlesnakes see more than we can. They are pit vipers, a subfamily characterized by heat-sensing pits on the front of their faces. We know rattlesnakes record history with their bodies. Their rattles are the products of every time they’ve ever shed their skin, keeping with them always a bit of their past as they become something new. Biologically and biblically, snakes are our destined enemies. I cannot say that if there was a pit viper before me, shaking its tail, I wouldn’t be afraid. This fear isn’t learned, it is instinctual. But what if nature had gone a different way? If God had taken pity on his creations, would we be able to share in the lessons of a snake’s rattle?

In one scene, a boy is bit by a cobra—not a viper, but the venom is arguably deadlier. A young woman attempts to suck the venom from the wound. This is pointless. By now, the neurotoxins are circulating throughout his body, shutting down his nervous system and his organs. Because a king cobra’s bite is strong enough to bring down elephants. It is a formula 140 million years in the making.

The strength of the cobra’s venom matters about as much to this movie as the woman’s attempts at first aid matter to the injury. Most likely, the scene is only there so she can be ogled by the other passengers as she works, and the snakes are only there to hiss and look scary before they are killed. We are trapped in the usual story. I have to wonder, after all this time, is there even a point in telling it? The movie ends with a shot of Samuel L. Jackson surfing, I guess the movie’s way of telling me there is none. I return to the image of the rattlesnake, with its head resting on its coiled body, and its tail in the air. And certainly you could not call it kindness, that thing you’d find in its slitted eyes, but you’d find something there. Some story with a point. Maybe even one that ended a different way. Who cares about the objectification of snakes? I do, apparently. Perhaps it’s muscle memory that has spanned many generations, going back to a time when Snake and Woman were co-conspirators. I think we could get back there. I think we have to. Six thousand years ago, a snake shared a secret with humanity and life began. There is still so much to learn about survival, and we are better off with more teachers than enemies.

ADIA COLVIN B’26 is slithering across the Quiet Green.

( TEXT [REDACTED]

DESIGN ANAÏS REISS

ILLUSTRATION LUCA SUAREZ )

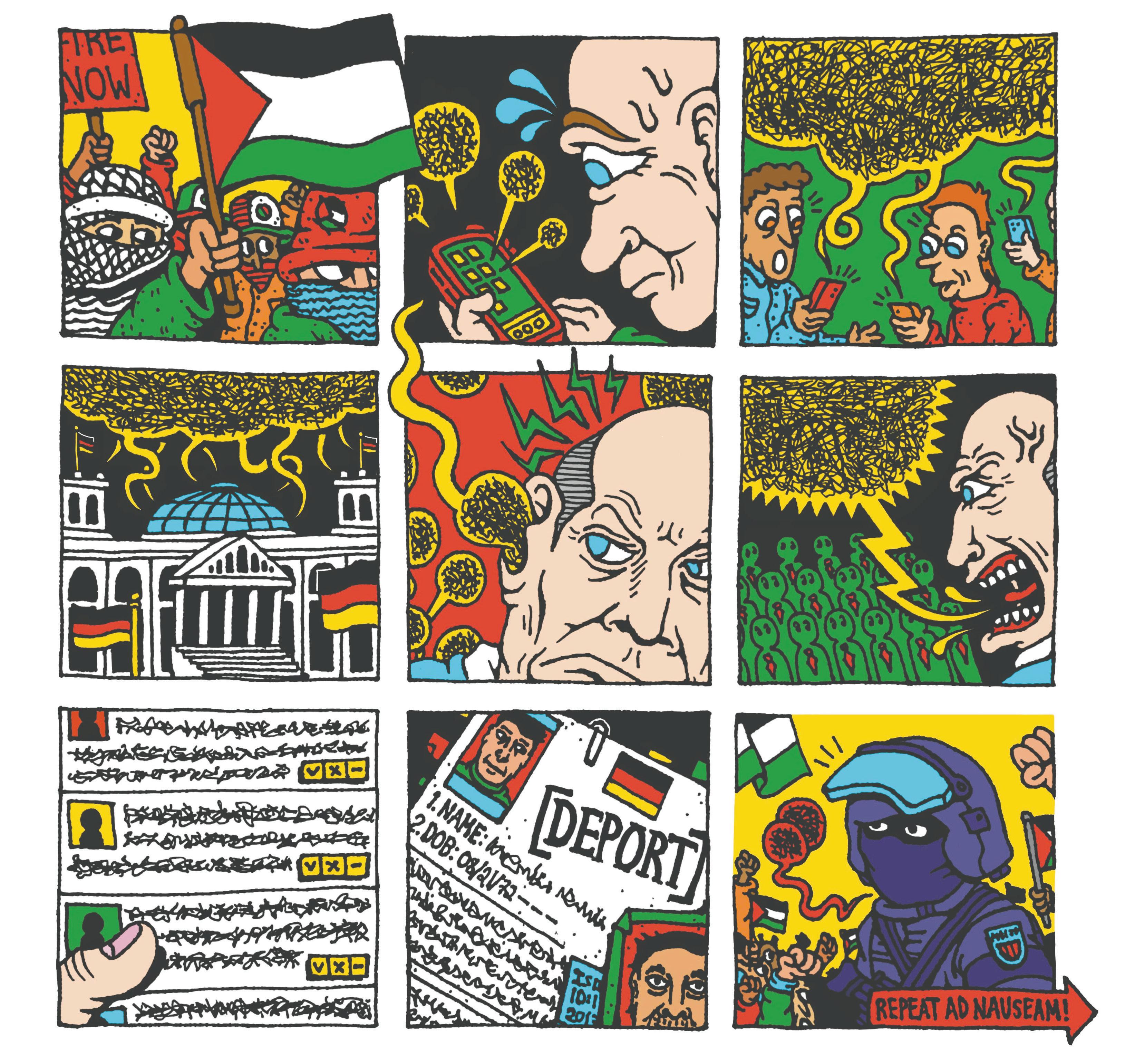

c “Shoot the pack or beat them back to Africa,” tweeted Dieter Görnert, a member of the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), in response to an article posted by Der Spiegel. In German politics, these racist sentiments are neither confined to him nor his party. As the German political left grapples with its identity and the center diverges, the AfD’s narratives expand their sphere of influence and reach to political nomads for support. Once they ensnare outsiders and less verbal implications begin to intersect, what primarily distinguishes their expressions from one another in the public eye? Articulation or content? Is the substance impacted by who articulates it? And what happens when it is perceived to be?

Since 2015, when a large number of Middle Eastern migrants arrived in Germany seeking refuge

from escalating violence in the Syrian Civil War, the AfD has intensified its dissemination of xenophobic narratives and successfully raised double-digit polling percentages in local and federal elections. While the AfD’s political carta initially consisted primarily of EU-skepticism and faintly nostalgic anecdotes of life before the fall of the Berlin wall and Germany’s reunification, its populist wing rapidly outgrew its more fundamentalist conservative counterparts. Only three years after its founding in 2013, the party grew irrevocably divided over its stance on PEGIDA— an annual right-extremist march (the initials standing for Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, or Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occident)—and held an election to determine a new party leader. This election was

won by the party’s extremist wing, which then went on to land on the Federal Ministry for Constitutional Protection’s ‘certain right-wing extremist parties’ list. Despite most major political parties rejecting and refusing to form coalitions with the AfD after its placement on the list, it has succeeded most defiantly in reshaping both public discourse concerning matters of race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender, and religion by turning openly discriminatory statements and rhetorical questions into seemingly genuine inquiries. For example, in 2022, Beatrix von Storch (AfD parliamentary fraction leader) openly misgendered and dead-named one of only two transgender members of parliament, only to then insist that the concept of conversing with transgender individuals was plainly too tortuous and that she