7 minute read

Arts

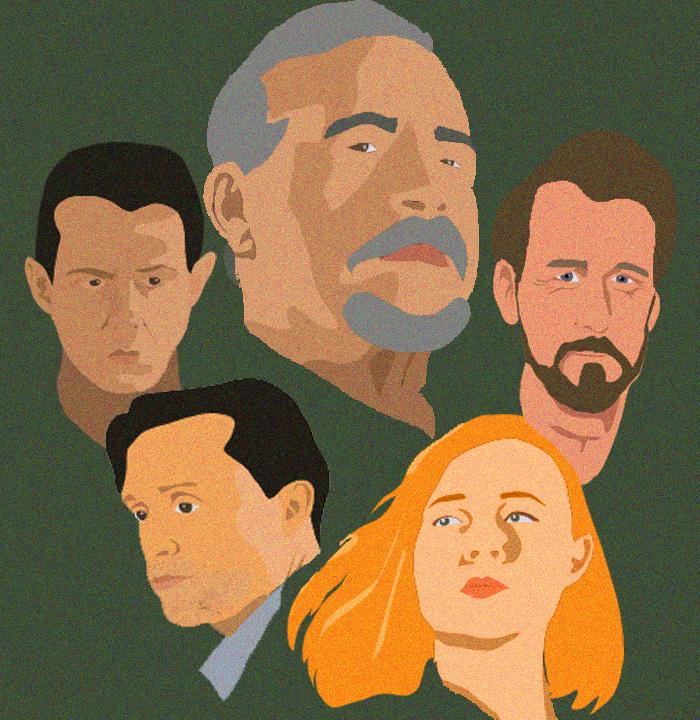

BY Cate Turner ILLUSTRATION Eliza Macneal DESIGN Daniel Navratil

Success Stories

Advertisement

Last October, then-presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg told the Hollywood Reporter that he was “struggling” to get into a buzzy HBO show called Succession. “I need a character to root for and I haven't decided if any of them are good people,” he said. Succession is, in brief, a show about a conservative media conglomerate run by Logan Roy, an elderly sadist. The central question of the show is which of his bloodthirsty children—three sons, one daughter, and, more peripherally, an in-law and a nephew—he will nominate to run the company. Most plot points revolve around billion-dollar deceptions; mass corruption and corporation-wide abuse also feature heavily. The stories the show tells are, without exception, those of people obsessed with money and power to the exclusion of absolutely everything else.

It would be easy to dismiss Buttigieg’s impulse to find an entertainment magnate to root for as a sign of his McKinsey pedigree, but the tension he identifies is central to Succession. It’s difficult to know how to approach a show that confounds genre as thoroughly as Succession. It has been categorized as a satire, but also as a drama, a soap, a corporate thriller, a tragedy, an adaptation of King Lear, and a parallel to Dynasty (HBO). Succession deals in family betrayal and personal failure, but emotional high-water marks are almost invariably undercut by satirical humor. The Roy family is humorously perverted by their spending power, but it is this same spending power that seems to bring about their moral failings, which are often cast as genuinely tragic. The image of the megarich that Succession presents is, in other words, very, very unfavorable—but its critique is always tempered by a fascination with why, exactly, these characters do what they do.

The second episode of the first season, in which the Roy siblings wait in the hospital after their father’s stroke, shows them reacting with genuine worry, guilt, and grief, and establishes the show’s twist-ridden— almost to the point of soapiness—narrative structure. The siblings struggle to balance their conflicted emotions for their difficult father with their desire for company power, and the episode dramatizes their grief and, even more importantly, their power struggles in typical dramatic form. The episode drums up interpersonal intrigue as a function of business intrigue, and vice versa. The siblings plot with and against each other; a major part of the show’s pleasure comes from watching these machinations play out.

But the episode also includes as much verbal and physical comedy as its title, “Sh*t Show at the F**k Factory,” would suggest. This comedy is always based on one of the characters doing or saying something that reflects badly, or at least stupidly, on themselves. Desperately attempting damage control for his father’s condition, Kendall (the ladder-climbing, sometimes-recovering drug addict who functions as the show’s protagonist) tells a business rival, “Simon says mum’s the word, motherf*cker”; his hamfistedly macho reaction is made even funnier by the sky-high economic stakes it attempts to protect. Cousin Greg, a newcomer to the Roy family, knocks over an antique bell in Logan’s palatial apartment and tells the housekeeper, “sorry if I summoned you,” when she appears, a truly abject portrait of human awkwardness in the face of new-money grandeur. Roman and his sister Shiv end up in a shrieky slapfight in a hospital lecture room over the fate of the company, and it’s the pigtail-yanking method that governs such a politically and economic change of power that makes the scene hilarious. Succession is far from the first show to juggle send-up and drama. The late-aughts/early-tens heyday of the mockumentary sitcom was based, in large part, on the form’s balance of satire and straightforward emotional narrative. These shows—most notably Mike Schur’s The Office and Parks and Recreation—balanced ironic distance from their subjects with an earnest investment in their romances, careers, and friendships. These shows share with Succession a commitment to a certain degree of verisimilitude as far as dress and styling go. Characters in The Office, especially its early seasons, wear bad haircuts and poorly-ironed shirts— they look, basically, like regular people, an appearance necessary to keep the documentary conceit afloat. Similarly, the Roy family is not movie-star beautiful. As Indy alum and New Yorker television critic Doreen St. Felix tweeted last September, “isn’t the thing with succession [sic] supposed to be that none of the characters are hot.” The Roy siblings have, variously, weak chins and bug eyes, reedy voices and unattractively smug resting faces. They are beautiful in the way of the real-life megarich—cashmere sweaters, retinol’d skin, palpably blow-dried hair, and, above all, pathological entitlement—but there’s unusually little movie magic apparent in their presentation.

More than anything else, this semi-verisimilitude makes characters appear more vulnerable. On the one hand, vulnerability makes them particularly easy to laugh at. On the other, it makes them easy to identify with, easy to pity. In The Office, it is the awkward realism of Dwight Schrute’s appearance that makes him so easy to mock early on and invest in later. In Succession, the same is true of a character like Roman, whose weaselly twitchiness is both funny and, in the moments when he isn’t outright malicious, weirdly endearing.

What sets shows like The Office and Parks and Recreation apart from Succession, though, is the linearity of their progress from one genre to another. These shows start with contempt, then turn it inside out, finding affection for the people they’re sending up in the process. This is probably part of why they decline so rapidly, and into total schlock, as the seasons go by: the more contempt they disprove, the less they have to work with comedically, and the arc of these shows is always to disprove contempt. Contempt, after all, is mean, and the people that The Office and Parks and Recreation depict—scrabbling low-level managers, hapless civil servants, all tethered to Heartland cities we are made to view as deeply embarrassing—are not really deserving of meanness. After a few seasons of stupidity, Michael Scott and Leslie Knope both become basically sympathetic leads, characters that viewers are clearly instructed to root for. They have serious love interests, success arcs, heartwarming found-family moments. They start out pathetic in the sense of being embarrassing, then become pathetic in the sense of being sympathetically pitiable. What they do begins to matter, and because it matters, it stops being funny. (It’s worth noting that Leslie Knope, by the close of Parks and Recreation’s last season, seems on track to be president of the United States.) Succession works by a different logic. Here, contempt and emotional narrative are always nearly simultaneous. Characters are ridiculous even and especially in their misery, regardless of how legitimate the misery is.

The major plot twist of the first season—when Kendall leaves a waiter to die after a car accident—is almost immediately set against a backdrop of the absurdities of wealth. Kendall returns to his sister Shiv’s wedding, where “I Gotta Feeling” plays at top volume. He calls out “hey man!” to his unimpressed brother (ridiculous), then dances with his children (sweet). The next morning, his cousin Greg tells Kendall, “there’s kind of a weird vibe with the service folks, the Hobbity people” (ridiculous), due, of course, to the waiter’s death. In the next scene, Logan comforts Kendall (serious), calling him “my number one boy” (serious/ridiculous). The trappings of wealth, among them a totally callous disposition toward human suffering, are set against the horror of what Kendall has done. These trappings remain hilarious; the weight of the death on Kendall remains tragic.

The simultaneity of satire and drama in Succession prevents the viewer from ever fully falling into either ironic detachment from or straightforward attachment to the action of the show. Every time the viewer begins to view Roy as a full, sympathetic person, the show chastises them; every time the viewer assumes a position of superior distance, they’re reeled back in. We identify both with and against the characters at every turn.

Unlike the characters of Parks and Recreation and The Office, the characters of Succession are not pathetic in their insignifiance. They are the billionaires whose whims dictate the realities of everyone else—by some measure, then, they are the most significant people in the world. Their idiocy is never harmless, because its stakes are the propaganda machine, the global economy, and millions of livelihoods. Each of their decisions, no matter how serious or trivial, reverberates. Succession treats the very-powerful as people, worthy of our empathy but always also deserving of our contempt. CATE TURNER B’21 suspects niceness.