13 minute read

Science+Tech

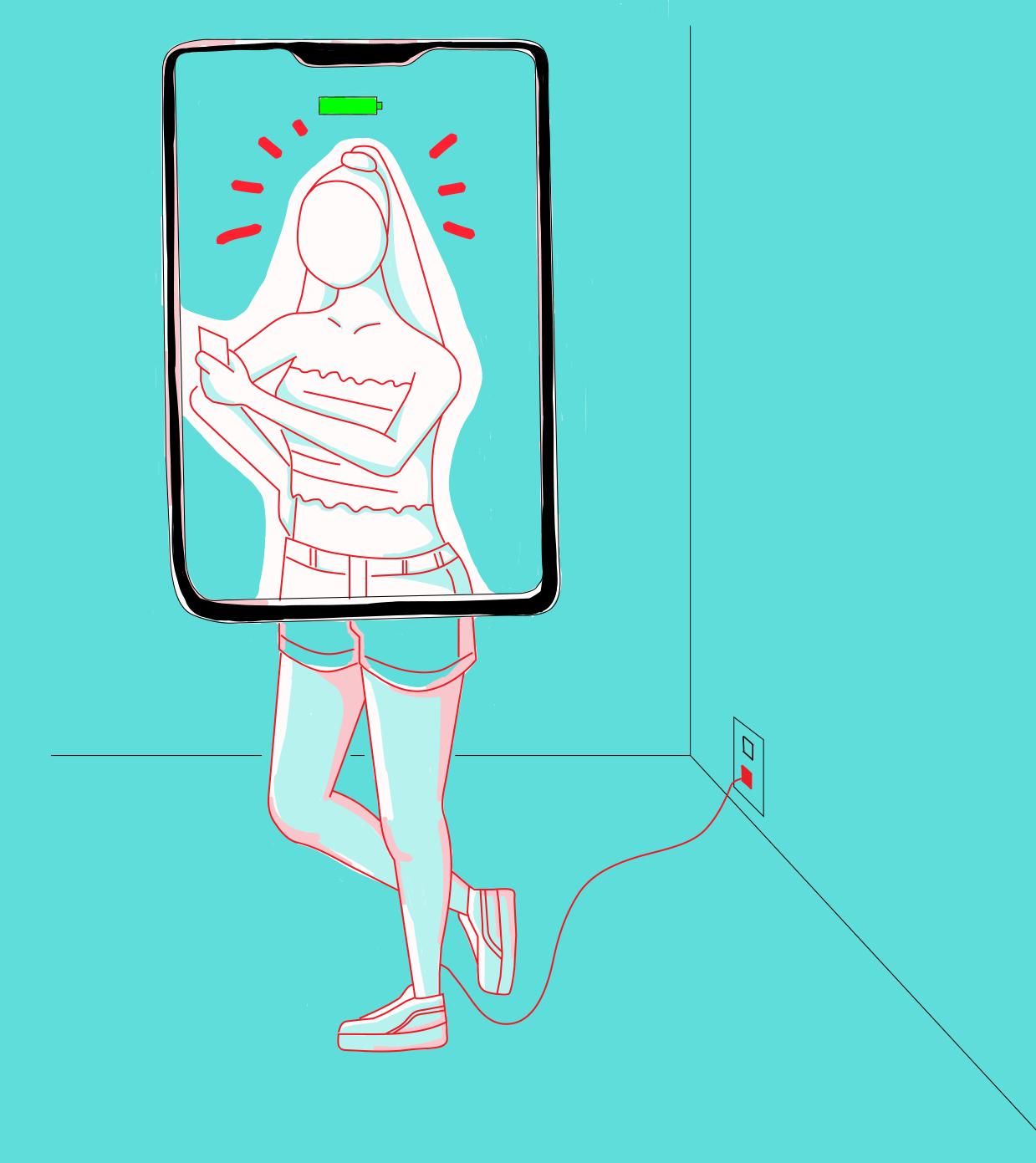

BUYING, SELLING, BEING

BY Anabelle Johnston ILLUSTRATION Floria Tsui DESIGN Ella Rosenblatt

Advertisement

Scrolling through TikTok is not unlike dissolving into a loop of repeating soundbites and punchlines as the definition between each video blurs, and time folds into itself. I spend hours watching teens pantomime the same songs, dogs patter across the screen to the same childlike voice-overs, and artists reveal their creations with the same “before-and-after” template. Occasionally, a celebrity will appear out of place, unsure of the proper facial expressions or hand gestures to accompany their carefully-edited performance that misses the purpose of the platform entirely. While Facebook albums and Instagram posts broadcast a curated version of everyday life, TikTok celebrates self-made creators. The app is aware of its own slapstick gluttony, providing a suite of simple editing tools that allow for universal participation. Everyone on the app unapologetically clamors for attention, providing relief from the online minefield of feigned authenticity.

I am swallowed by the same wormhole of capitalist self-creation when browsing the virtual marketplace of Depop, downloaded in pursuit of a pair of broken-in Oxfords to save myself from blisters and overspending. Like most Gen-Z-centered software, the quintessential Depop shopping experience occurs on a mobile interface instead of the desktop, as the app is designed to mimic the social media revered by this generation. The Instagram-inspired “explore” page features established shops that mimic magazine photoshoots alongside girls taking mirror selfies of “ugly” ski sweaters that have swung back into “fashion.” I’m greeted by a plethora of Dickies garments, novelty earrings, and multicolored clogs, all tagged as the CUTEST ever and #vintage. As I fill my virtual shopping bag with secondhand acquisitions, I become aware of how similar each article of clothing is despite the personal nature of the pick. The collection of granny sweaters, midi-skirts, and pastel mock-necks sitting in my cart could have been sold by one Urban Outfitters-type store. Each seller has their own “brand” for sale, and yet they are eerily similar, as the daily eclectic mix of clothing “featured” by Depop complements itself in a chaotic fashion. Peer-to-peer purchasing on Depop allows users to shop the closet of the cool kids at school, equating the act of buying with emulating and being.

TikTok and Depop provide avenues for anyone to be a creator and content curator; the only requisite is a cell phone and sense of self. Unlike long-gone Vine or millennial-appealing Poshmark—the respective predecessors for both platforms—TikTok and Depop are designed specifically to fit the needs and online habits of Gen-Z, merging AI-driven in-app navigation with shameless self-promotion. Although these platforms were not designed by this generation, they are perfectly suited to meet youth culture in ways that other online marketplaces and social media apps cannot. Gen-Z Zoomers are typically characterized as entrepreneurial and tech-savvy, traits evident in the 15-year-old TikTok stars with brand deals and teenage Depop sellers that have designed custom shipping labels. At 18, I am on the cusp of the target demographic, as I am notably older than TikTok celebrities and middle school entrepreneurs. And yet, I still participate by watching and buying in awe. Viral TikTok dances and “vintage Depop style” have pervaded the media I consume, from Instagram meme accounts to New York street style, until—at least for me—immersion into these platforms has become inevitable. In some ways, Gen-Z creators and store-runners understand better than I do that personhood is entangled with purchasing power, and to participate online today is to be a consumer.

+++ Both apps have been extremely popular among teenagers for years and recently have grown to be recognized as platforms to be reckoned with by investors, college students, and baffled millennial culture writers. 90 percent of Depop’s 15 million active users are under the age of 26, and approximately 37 percent of the 1 billion TikTok users worldwide are under the age of 19. Both apps are concentrated around the same age demographic, attracting a variety of users due to their accessibility, a value important to untrained youth looking to create content. Both TikTok and Depop grew out of foreign platforms—China and Italy, respectively—and both have developed around the ‘globalized teenager’ while blending technology with modern youth culture. Sociologists Dr. Kaylene Williams and Dr. Robert Page postulate that Zoomers who grew up in the aftermath of 9/11 and during the rise of school violence often value security and self-sufficiency, rejecting large establishments in favor of the individual.

In their formative years, popular franchises such as Hannah Montana and High School Musical introduced this independence to tweens on the cusp of adolescence, featuring characters that dress and act in their own self-interest. Hannah Montana’s father may have played an important role in her life, but Hannah had an independent career and final say over her actions as an artist and young woman, inspiring a generation of viewers to want the same for themselves. According to a 2011 study published by the Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business, in breaking from norms of other generations, Gen-Z exists as a diverse but cohesive web. Coupled with the constant formation of new social media platforms, this environment led to the creation of a generation more interconnected than ever before, as Zoomers constantly seek the acceptance of their peers. Whether that acceptance takes the form of likes or stylistic affirmations, this development primed Gen-Z for both Depop and TikTok, as the interfaces are designed to fit Zoomer needs.

In 2011, the Italian culture and design magazine Pig created Depop to allow readers to purchase the clothing and accessories featured in each issue. This invention—and its descent from magazine format— complicated the distinction between the emulation of trends and the forced participation in the market to be an active member of a community. With the advent of Depop’s selling function, and subsequent arrival of Groupon executive Maria Raga in 2014, the app became a marketplace for teens to buy, sell, and most importantly, trade. There are structural similarities between Depop and Instagram: both networks allow users to follow other profiles—or personal storefronts— and hashtag their own posts to increase their following. The apps complement each other, too: teens will buy a top for a single Instagram post and sell it the next day to someone else, creating a globally-shared wardrobe that at once promotes individuality while hovering over an exact stylistic epicenter. The grid format utilized by both apps provides omniscient observance—the user sees everything in juxtaposition while exploring posts by various accounts, though similarities in taste help conceal that each storefront has a different owner. Clicking on one picture and intuitively scrolling reveals an endless selection of related posts, as the apps generate individual collections of more things you might like.

Depop speaks to the Gen-Z rejection of fast fashion and linear projection of style, as Y2K crop tops are layered with flared jeans reminiscent of the 1970s, repurposing old pieces to create a cacophonous image that diverges from runway trends. Other platforms have mimicked Depop’s model with less success. Instagram’s “checkout” feature and Pinterest’s shopping options streamline the I see it, I like it, I want it, I buy it process, but still rely on heavily-stylized images and branding. As tempting as it is to purchase the Pinterest board of my ideal life, it feels too complacent—and expensive—for me to ever press Buy. Instead of directing users to brands like For Love and Lemons to purchase a hat showcased in the picture just pinned, Depop places individuals, instead of corporations, on either end of the selling spectrum. The creators of Depop understand that identity is advanced marketing of the self and everything, by extension, is for sale. This idea of commodifiable selfhood is built into the fabric of the app and bought into by this generation as a whole. The thrifty and inexpensive nature of the app allows for fluidity of expression, as long as one pays for it.

+++ Similarly, TikTok puts “regular people” on both sides of the screen, rejecting the notion that advanced editing or equipment is necessary for quality production. Although many college students and adults look down upon the short clips as low-brow entertainment, TikTok provides the tools for creators to film whatever they desire while the app learns what viewers want to see. The app’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, bought Musical.ly in November 2017 and merged the platforms in August 2018 to create an app for short form videos set to music. The music itself is a phenomena, with heavy synthesizers, distorted voices, and bass drops that soundtrack transitions or serve as punchlines. One of the most popular songs, “Lottery” by K Camp, is used in the viral Renegade dance created by 14-year-old Jalaiah Harmon. The song has a repeating drum track, the word renegade is spoken by a breathy female voice, and a man says “go” multiple times before breathing heavily. The clip itself is unspectacular, but made popular by its simplicity. It crescendos with repeating beats at the end of the 11 seconds, creating a format perfectly suited for dancing. The Renegade dance can be—and has been— learned by anyone, which inspires everyone to try. As the app is designed for rapid mass-sharing, sounds and dances go viral, then disappear into obscurity with unprecedented frequency. Content is constantly in conversation with itself, facilitated by the app’s duet feature that allows for YoutTube-style reactions to other videos. Users utilize a split screen suited for comic additions or call-and-response dances, tagging the original creator either in the comments or by simply using the same song.

Unlike Instagram and Depop, TikTok first presents its users with the “ForYou” page, an endless algorithm-based amalgamation of videos, collected from past viewing habits. While “explore” pages are common, TikTok places its “ForYou” in the forefront, as the first thing viewers access when opening the app. Although each video on this page is distinct,

Gen-Z SelfAdvertisement on Tiktok and Depop

the longer one spends on the app, the more focused this page becomes. I was astounded to learn that my friends’ ForYou pages didn’t feature Adam Driverinspired videos, and that TikTok had regurgitated my weeklong obsession with Driver until it was unclear who controlled the content I absorbed. Like on Depop, a similar instance of hovering occurs, less centered around Doc Martens and instead based on the individual’s preferences as learned by ByteDance’s A.I. technology. While popular content on Instagram may range from celebrity content to meme pages and YouTube celebrates a slew of gamer-celebrities and Bon Appétit stars, TikTok and Depop are uniquely definable. To be popular on TikTok is to fit a specific mold, though that mold was created in Gen-Z’s image of itself and distilled through A.I.

Both apps manipulate selfhood into profitable shapes without the vague terminology of influencer, as the influencer paradigm doesn’t really apply when the whole platform is—literally or figuratively—marketplace. Teens embody trends and then sell these commodifiable personas in time to move on to another, from one popular dance to another clunky sneaker style. This immediate turnover and demand for attention requires users to self-advertise and incessantly promote their own material and brand; in allowing anyone to become a star, everyone vies for the spotlight. On the one hand, these apps create a democratic space for cultural production, but they are also eerily totalizing. Depop commodifies style and TikTok does the same to dances and memes. Together the apps produce a cultural drift wherein everything converges on a single center or trend. The constant exchange of ideas through these platforms rests on their accessibility and the ease with which the apps learn what its audience likes. The prominence of TikTok cosplay may not rest on user desire to watch 15 seconds of an amateur actor dressed in 1920s garb performing overly-animated hand motions, but rather the algorithm’s insistence on showcasing videos tagged #POV (point of view). In this contained world, content creators benefit from the app’s design, until the distinction between A.I.-generated trends and user-generated trends becomes inconsequential. +++ For many, TikTok and Depop provide a space to subvert the norms of fast fashion and mass media. Instead, they offer equally consumerist alternatives focused on the individual and Gen-Z as a whole without regard for older media traditions. However, some stereotypes and structures have been recycled from generations past. The ubiquitous TikTok e-boy—often distinguishable by his graphic tee layered over a striped longsleeve shirt, black nailpolish, and middle part—is not unlike the 80s moody heartthrob in his embodiment of alternative attraction. Similarly, tag sales have long made a market out of repurposing another’s goods. Yet the method employed by both apps feels revolutionary because they connect teens across the world with others in a way that allows everyone to feel seen and heard. Rebranding into the compact platforms of TikTok and Depop offers a new audience and necessitates movement forward into the technological abyss of endless content.

Other social media sites like Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook are designed to give space for users to shout into the void, projecting their innermost thoughts or the most palatable versions of their lives. But social media sites popular with today’s youth are designed to do the opposite. After purchasing a pair of enamel earrings featuring two cats breaking into a vault, I left a review for the Depop storefront and the owner left one for me as a customer. Our success as individuals in the virtual space is contingent upon mutual respect for others’ roles and the understanding that we need each other. Many users of the app are both buyers and sellers, engaging in a trade that mimics evolving roles in the real world. We are not simply consumers or producers, but constantly self-advocating and self-advertising.

Likewise, the format of TikTok facilitates conversation and communication across videos on a split screen. Young TikTok stars often collaborate on videos (some even living together to perform this task with ease), choreographing together to create a cohesive brand for the app and themselves. Charlie D’Amelio, arguably the most famous of TikTok creators, is often referred to as “having the hype,” terminology that is specific to the app and perfectly encapsulates the instantaneous phenomenon that dominates the platform. Just as dance trends go viral overnight, D’Amelio rose to fame with startling speed. She frequently dances with other stars, and her videos are often dueted by users hoping to be noticed, sometimes even cheering her on or “hyping her up.” The comment section of her app is bustling with people defending and attacking her, most notably for her normalcy. Her videos are often singletakes of her dancing in a sparsely decorated room, and her popularity speaks to the value of the everyday. Anyone could be Charlie D’Amelio, and youth across the globe are both competing and collaborating to fill that role.

Both Depop and TikTok facilitate connections within an insular community of teen creators that outsiders may try to contribute to but never can. The technology is designed to reinforce what is already popular, dictated by what interests Gen-Z. The apps contain an ongoing conversation that is virtually inaccessible to those who have not already been listening, uncovering not only what Zoomers like, but, more importantly, what they are willing to pay for. Scrolling through TikTok, I often glance at Depop advertisements, as both apps speak to the same audience—those born too late to be YouTube famous but who still recognize the value of the vlog and the profitability of the mundane. I’m not sure how completely I fit into that camp, but I still can’t stop scrolling. ANABELLE JOHNSTON B'23 refuses to put her selfhood up for sale.