12 minute read

Why Won’t Brown Talk About Divestment?

The Brown Corporation stonewalls students advocating for justice in Palestine

In the spring of 2019, Brown University held an extraordinary student election. With an unprecedented voter turnout of over three thousand undergraduates, the student body passed a referendum that called on the Brown Corporation to withdraw all of its investments in securities, endowments, mutual funds, and other monetary instruments in the holdings of multinational companies that were complicit in human rights abuses against Palestinians. The sucessful divest vote not only endorsed the toil of student organizers, it also sparked a ripple effect nationwide, as student activists across college campuses—most notably, at Columbia—ramped up pro-Palestinian activism, passing similar divestment referendums. These efforts signpost the beginning of a new civil awakening among young Americans who refuse to be complicit in the United States’s endorsement of structural human rights abuses in Palestine.

Advertisement

Yet, today, almost two years since the popular referendum, Brown has still not divested from holdings at corporations such as Caterpillar Inc., which sells bulldozers to the Israeli Defense Forces to demolish Palestinian homes and disappropriate Palestinians of their land. As if the moral imperatives of divesting were not enough, Caterpillar Inc. also falls on the list of organizations blacklisted by the United Nations for economically enabling the Israeli government to occupy Palestine in violation of international law, adding a legal motivation for divestment as well.

At a recent virtual town hall hosted by the Undergraduate Council of Students on February 4 that sought to bring members of the Brown Corporation into dialogue with Brown students, members of Brown University Students for Justice in Palestine (BSJP) confronted Corporation members on their calculated reticence on the question of divestment. While we hoped to finally get clarity on the lack of communication, we left the meeting with nothing except a deep frustration with the Corporation’s decision to deflect, sidestep, avoid responsibility, and continue quietly smothering the will of the students with their silence.

The employment of divestment as a pressure tactic to hold perpetrators of structural human rights violations accountable to the law has a long and powerful history. In Sanctioning Apartheid, Robert E. Edgar shows that divestment works on a number of axes in addition to direct financial pressure. In fact, he argues, the movement to divest from South African apartheid, a strategy borne on college campuses, forced significant capital flight from the apartheid regime while ramping up public awareness and international scrutiny of trans-national corporations profiteering from violence.

Here, at Brown, we follow the rich legacy of student activists who have successfully campaigned to extricate Brown from its financial support of South African apartheid in 1987, the tobacco industry in 2003, and genocide in Darfur in 2006. We also persist in the fight to combat the Brown Corporation’s reluctance to stand up to injustice. For instance, as surprising as it may seem today, Brown did not fully divest from apartheid in South Africa until after student activists held massive rallies outside of Brown Advisory and Executive Committee meetings, fasted in protest in Manning Chapel, and faced probation after disrupting a meeting of the Corporation. In 1987, even after students, faculty, and administrators had reached a consensus, it was the Brown Corporation that stood in the way of full divestment from South African apartheid. The Corporation’s historical tendency to put off ending its complicity in morally bankrupt practices until direct action from students forces the issue (or until public relations or fiscal incentives shift) foreshadowed its present day treatment of the effort to divest from violence against Palestinians.

The Brown Corporation is the university’s ultimate governing body, responsible for selecting the president, budgeting, appointing faculty and senior administrators, and making all large-scale policy decisions. Therefore, the decision to divest from human rights abuses in Palestine rests in its hands. After the Divest student referendum passed in March 2019, President Paxson responded by positioning Brown’s Advisory Committee on Corporate Responsibility in Investment Policies (ACCRIP), later renamed the Advisory Committee on University Resources Management (ACURM), as the only legitimate channel for reaching the Brown Corporation. Once again, Brown Divest organizers rallied community support to overcome a string of new obstacles. On December 2, 2019, half a year after the student body vote, ACCRIP published a decision addressed to President Paxson backing the referendum and urging the university to divest from any company that profits from the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land. ACCRIP’s vote indicated that every part of the university—students, faculty, and staff—had supported this movement. Only the Brown Corporation stands in the way of divestment.

The historic referendum and the subsequent ACCRIP recommendation to divest was the culmination of years of work by student activists and the clear will of the student body. However, the ACCRIP recommendation, much like the student vote, is non-binding, and the final decision on divestment falls to the Brown Corporation. Has the Corporation followed these recommendations and divested from companies violating the human rights of Palestinians? Their answer, unfortunately, is silence. “The lack of action is just overwhelming,” said an BSJP organizer during the February 4 University Council of Students-Brown Corporation meeting. The Corporation’s disinclination to discuss divestment at the town hall was demonstrated by the long and awkward pauses between responses to our questions, deflections of accountability to alternative university structures, and occasionally the measured admonition by Corporation members that student activism at Brown had gone too far. Far from being prepared to issue a decision on the ACCRIP divestment recommendation made to them over a year ago, the Corporation failed to provide a clear answer on whether divestment had been so much as discussed in their private meetings.

At a segment of the meeting ironically titled “Transparency and Communication,” Corporation members gave muddled responses when asked when they had last discussed divestment from injustices in Palestine. Member John Atwater said that “the Corporation is aware of the topic” but didn’t clarify whether this awareness entailed any discussion of divestment during Corporation meetings. Member Pamela Reeves recommended that BSJP search the public records of meeting minutes from the Corporation. We took her advice, but neither ‘Palestine’ nor ‘divestment’ have been mentioned in the summaries of any Corporation meeting since the recommendation was made in 2019. Member Kate Burton, on the other hand, appeared confused about the fundamental premise of our questions altogether, claiming that the last time she had discussed divestment in the Corporation, it was about divestment from coal, not human rights abuses in Palestine. Member Tom Tisch said that divestment was a current “issue before the Corporation” but avoided stating when the last briefing on the topic had occurred. They sidestepped student questions and concerns, choosing instead to highlight other divestment campaigns they’ve derailed, like coal divestiture. “While the university did not make a decision to divest from coal,” bragged Tisch, “it was dazzling to see how the administration took that as a challenge to do things consistent with Brown’s mission.”

Corporation members also consistently and deliberately attempted to evade responsibility,

shifting their undeniable role in the matter onto the shoulders of various other offices at Brown. In response to a student’s question about the appropriate avenue for pursuing divestment, Corporation member Jeffery Hines stated that “most of these issues need to go through Campus Life,” as the Corporation is not “the management arm of the university.” Member Laura Geller incorrectly claimed that the issue of divestment was “sent back to ACCRIP to continue to consider.” ACCRIP no longer exists and was replaced with ACRUM; furthermore, no publicly available records of ACRUM activities reference any reconsideration of divestment, and no BSJP members received any communication about the recommendation needing further consideration. Another member, Donna Weiss, suggested that we speak with the Investment Office. At best, these suggestions were misguided attempts to appease students, incidentally revealing members’ ignorance on an issue they claim to have considered. At worst, these Corporation members are guilty of intentional, thinly veiled evasions of blame.

Tisch’s reluctant admission of the Corporation’s obligation to address ACCRIP’s recommendation buttresses this. “[Divestment] is an issue before the Corporation,” he conceded in response to Weiss’s remark that divestment was a topic for the Investment Office. And yet, when asked about the Corporation’s status on discussing divestment, Tisch refused to elaborate. “I really do not want to get into a discussion that exists inside the Corporation room. That is a matter for the Corporation,” he said.

Tisch is not wrong that divestment is now a matter for the Corporation. ACCRIP’s 2019 recommendation to divest attempts to circumvent some of the inevitable red-tapism used to

strangle ethical investment pleas. Identifying the inadequacy of the university’s actions centering Palestine, ACCRIP directly urged the Corporation to exclude companies identified as facilitating human rights violations in Palestine from Brown’s direct investments. It also asked the Corporation to require Brown’s separate account investment managers to exclude such companies from their direct investments. ACCRIP’s adroit choice of words makes clear that the responsibility to divest falls squarely on the Corporation, not Campus Life, not the Investment Office, and not a vague “administration.” Only the Corporation can do what remains to be done—divest.

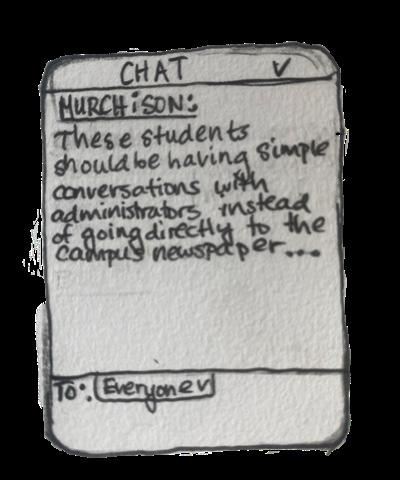

As the meeting came to a close, Corporation member Joelle Murchison decided to bestow some advice on BSJP attendees. She chided students for going directly to “the campus newspaper or to a media outlet,” recommending instead “simple conversation” and “dialogue” with an administrator about divestment. Brown students should heed these wise words. If only BSJP members had thought to meet with President Paxson, or organize a campus wide referendum. If only we had spent months preparing and presenting to Brown’s committee on ethical investment practices. If only such a committee had recommended that the Corporation divest from social harm in Palestine. If only we had followed proper procedure and practiced decorum. Perhaps then we wouldn’t need to confront Corporation members at an open meeting with requests for updates on a popular, university-wide vote that took place two years ago. Instead, here we are, disregarding Ms. Murchison’s advice, appealing to the student body through a radical campus newspaper.

The Corporation has failed students. Their placid “we are listening” means little to us. Even Bernadette Aulestia, a Corporation member herself, was willing to admit that the student body is owed a “more in-depth response… Let us know if that’s something you want to know our response on,” she said at the meeting.

It may seem absurd that the Corporation would refuse to comment on its discussions and yet promise students “a more in-depth response” in the same breath; however, this paradox is intentional. Universities like Brown have a clever and wellestablished playbook for quietly asphyxiating student activism. To quote Brown Class of ‘88 James Foreman Jr., an organizer for the Divest movement from South African apartheid: “Universities have gotten much smarter. They don’t just completely lock people out anymore. They invite people in, they form committees, they have ad-hoc working groups, they have study commissions, they ask the students ‘well what do you think’ and ‘let’s write a report about this’, because universities know that students graduate, and the group that was passionate about an issue, after they spend a year and half writing a report, half of them are out the door, and the other half don’t remember what the whole fuss was all about.” The seemingly contradictory messages from the Corporation stem from the fact that the Divest movement has exhausted all of the typical avenues used to defuse student activism. There are no more administrators to refer us to, no more committees to form in the hopes that we’ll lose ourselves in writing reports and forming task forces and floundering in red tape.

To deny the ACCRIP recommendation outright would reveal that the Corporation can and will disregard decisions made by bodies of the university itself. It is critical for the Corporation to maintain the illusion that the student body can create change by working within the university system, when in reality those methods only work to create changes that already align with the Corporation’s financial and optical interests. It is no accident that the only formal response from a member of the Corporation on divestment—President Paxson herself—came in the form of a letter in March 2019, denouncing divestment as “polarizing” and overly controversial. It is important to note that this occurred shortly after the student referendum and before the publication of the ACCRIP recommendation. A public rejection of the ACCRIP recommendation would betray the unilateral, uncontested nature of the Corporation’s power and expose the extent to which the Corporation’s interests diverge from the will of students, faculty, and administrators. The Corporation can afford to publicly contradict the will of the students so long as they can appease activists with the promise of further discussions and meetings with administrators; a denial of the ACCRIP recommendation would prove that agitation for change within established university structures is a farce. Above all, the Corporation cannot risk students and faculty realizing their actual power; they would much prefer for students to vent their frustrations in administrative meetings than in newspapers, or to protest in university-appointed committees instead of on the Main Green. And so, the Corporation must stay silent on the ACCRIP recommendation; saying no would tell students that if they want to make change, they will have to take direct action.

University administrations aim to co-opt, manipulate, and ultimately dispel any radical organizing potential among their students. Brown, as evidenced by the Brown Corporation meeting we attended, is especially guilty of this hypocrisy. The university likes to masquerade as a liberal institution open to student activism, yet its highest body simultaneously ignores and further marginalizes student voices. But we refuse to be silenced. We are here. Our voices demand to be heard, our imaginations refuse to be limited, and our struggle for justice in Palestine will continue.