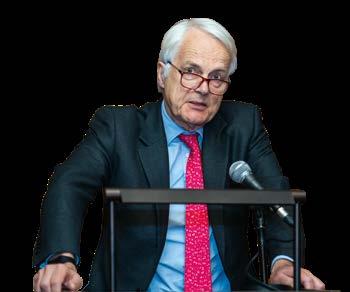

Sir Robert Francis KC

Sir Robert Francis KC

Sir Robert Francis KC

Sir Robert Francis KC

YEARBOOK

“TheCHRISTOPH ESCHENBACH

Inner Temple Yearbook 2023–2024

Treasurer:

Sir Robert Francis KC

Reader:

The Hon Mr Justice Michael Soole

Reader Elect: Richard Salter KC

Sub-Treasurer:

Greg Dorey CVO

Treasury Office: Inner Temple, London EC4Y 7HL 020 7797 8250 yearbook@innertemple.org.uk innertemple.org.uk

Master of the Yearbook: Minka Braun

Editor: Lily Walker-Parr

Assistant Editor: Henrietta Amodio

Yearbook Managers: Nadia Ruiz

Desk Editors: Carolyn Dodds, Sandra Alvarez

Archivist: Celia Pilkington

Education & Training Editorial Team: Julia Armfield

Photographs:

Garlinda Birkbeck

Miranda Parry Photography

The Inner Temple photograph archive

Yearbook Design: Jon Ashby | Noun Ltd, 10 Kingshill Court, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire HP13 5FN wearenoun.com

Brandworld Design: SomeOne, 67 Leonard Street, London EC2A 4QS someoneinlondon.com

Advertising:

HTDL Ltd htdl.co.uk

Printed by:

John Good Limited, Progress House, Butlers Leap, Rugby CV21 3RQ, johngood.com

FROM THE EDITOR

Welcome to the Inner Temple Yearbook 2023–2024.

I feel grateful and daunted in equal measure to take up the mantle from Emma Hynes as Editor of the Yearbook. After accepting the kind offer, I was told that it is customary to occupy the role for three years (although Emma managed four), so do forgive me any amateur slip-ups while I settle in.

This edition marks the end of a particularly busy year for the Inn, as all systems are go once again following the pandemic and completion of Project Pegasus. Members have returned to the Inn en masse to enjoy lunches and dinners in Hall, events and training in the new education facilities, and refreshments at the Pegasus Bar. Inner Temple has also welcomed a new LGBTQ+ Society, questioned the status quo in its popular ‘Social Context of the Law’ lecture series, and continues to attract new talent to the Bar through its extensive outreach work.

In reviewing this edition, I am reminded that our Inn is not only a tranquil and picturesque oasis in the heart of a bustling city, but also a professional home which remains a constant source of support and community for all its members. It is easy to forget the large network of skilled staff and volunteers who work hard to keep the Inn running, and it is to them that I wish to dedicate this issue.

My thanks also to all who have contributed to the 2023–24 Yearbook, particularly to Master Minka Braun, Henrietta Amodio, Nadia Ruiz and the wider editorial team.

I am excited to be able to contribute in a small way to this archive of the Inn’s activities and truly hope that you enjoy the read. Until next year,

Lily Walker-Parr 5RB

FROM THE TREASURER

CALL TO THE BAR

I write this shortly after the Trinity Term Call Night, as always an inspiring occasion. 102 students were called to the Bar in the presence of over 300 enthusiastic supporters, at least a few of whom were probably too young to remember the event, all proudly witnessing a momentous event for them all. Their deafening ovation showed the wonderful support in emotions and resources that so many of our students enjoy. It was such a pleasure to meet parents, partners and friends afterwards and to share their joy and pride in their loved one’s achievement. And once again there were many members from countries outside the UK – 20 to be precise – among those called.

VISIT TO INDIA

We are a relatively small profession, but the Call ceremony reminded us of the esteem in which the Bar of England and Wales is held across the world and, associated with that, the rule of law as recognised and applied here. That was confirmed on our trip to India in February when we visited Delhi and Goa to meet senior legal professional and judicial leaders, and to attend the Commonwealth Law Conference. Visiting the Supreme Court of India and the Delhi High Court allowed us to appreciate the impact of the common law in the world’s largest democracy as well as the challenges and opportunities provided by its application in the context of a written constitution, and a society of such a wide range of political, religious and cultural perspectives. Likewise at the Commonwealth Law Conference we were able to renew old acquaintances and make new ones from across the member states. It was fascinating to hear the different perspectives on shared challenges, and the very different, sometimes alarming context in which some of our colleagues must work and need our support. I confess it was also enormous fun to meet so many talented, energetic and hospitable people! What were the messages I brought home? First, there is much we can learn from these visits. For example, the commitment in India to a technological revolution in the way litigation is conducted, under the inspirational leadership of the Chief Justice of India, Dhananjaya Y Chandrachud, from e-filing to live streaming of proceedings https://ecourts.gov.in/ecourts_ home. Second, there is significant interest in fostering

reciprocal arrangements for practising in each other’s jurisdictions. Thirdly, and not least, the Pegasus Scholarship scheme, among other initiatives, and contact with our members practising in their home jurisdictions encourage mutual support for the rule of law. Given the challenges to judicial independence, access to representation and professional freedom, mutual understanding and collaboration has never been more important.

TIMING OF CALL

Back home there is an increasing focus around what is now called the Timing of Call. Call to the Bar is but one stage in the arduous journey to entitlement to appear in the courts of England and Wales. In 2021/22 there were 2,178 students (of whom 980 were overseas students) on the Bar Course, a 45 per cent increase from 2017/18. The overall success rate on the Bar Course between 2011 and 2019 averaged 78 per cent. Because of the shortage of pupillages, and the desire of many candidates to practise in their home countries a large number of those who are called the Bar never go on to obtain a practising certificate. This means that currently there are 17,538 practising barristers registered with the Bar Standards Board and some 57,700 barristers who have no practising certificate but have been called to the Bar and are therefore subject to regulation by the BSB. Arguably this causes confusion for the public about what services a barrister can provide.

This has led to renewed discussion on the criteria for being called to the Bar. One argument is that only those who have completed pupillage should be entitled to be called, postponing the entitlement to describe oneself as a barrister to that point. Others argue that this, certainly on its own, will not solve the problems of allowing numbers to undergo the stress and expense of the Bar course massively in excess of the numbers who will end up in practice. The debate has been going on for at least 40 years but may well come to a head quite soon as the regulators have expressed interest in it. Therefore, all members in this country or elsewhere who care about the future of the profession should interest themselves in the discussions which will be taking place. The Inn, through the Executive Committee, with the help of a working group that has been set up will be considering the matter in depth during the rest of this year.

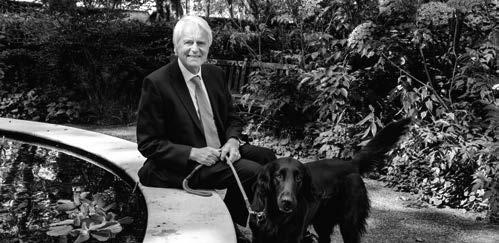

Sir Robert Francis KC © Garlinda Birkbeck

Sir Robert Francis KC © Garlinda Birkbeck

THE LIFE OF THE INN

I have been fortunate to be Treasurer for the first full year of our being able to enjoy the facilities of the two new upper floors of the Treasury Building. All visitors have been unanimous in their praise for what they see. It is so rewarding to see how excellently the design has blended the new with the old, making the most of our history and our ambition and our drive to promote and support a profession which is responsive to the needs of our times. This has all undoubtedly enhanced the experience for people attending the many events that have taken place this year.

Highlights for me have included the Social Context of the Law seminars ably assembled by Master Geoffrey Nice, which have addressed the topics of refugees’ human rights, whether the country’s constitution can survive recent challenges, and whether the adversarial system is fit for purpose. It says much for the Inn’s standing that these events can attract participants of national and international standing, such as Professor Gillian Triggs, Assistant General Secretary of the United Nations, The Rt Hon Lord Bonomy LLD, former justice of the Supreme Court Scotland, and of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, and Professor Sir John Curtice FRSA FRSE FBA, well known predictor of our election results, to name but a few. The Inn’s societies have been busy, too, with a particular favourite of mine being the talk organised by the LGBTQ+ Society and given by Master Kirby (Mr Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, formerly of the High Court of Australia) strikingly titled Sodomy Law: the UK’s Persisting Legacy and the Great Quandary. All these events showed how successful our new and comfortable lecture theatre is as a venue, and how we now reach a wide, even international audience through live streaming some events. An honourable mention is also due to the tremendous efforts of the Drama and Debating Societies and the impressive performances of so many students.

Finally, it has been great fun to meet our members on Circuit at the various dinners arranged in collaboration with the Masters of the Circuits. I value these occasions as great opportunities to learn about circuit life and what the Inn can do the support them.

The social life of the Inn has returned to full speed. All our dinners, receptions and other events have been oversubscribed and shown off the great skills of our wonderful catering team for whom no demand is too difficult. The Garden has been a constant source of pleasure to me and many others with the partial ‘rewilding’ producing new and attractive surroundings for birds and insects – as well as humans and the occasional dog! The Garden Party was enjoyed by all, even if the Handel theme turned out to involve more water from a downpour than we had bargained for!

EDUCATION AND TRAINING

The Inn has continued to perform outstandingly in the duty imposed on us by James I of educating and training our members, old and new. As was the core purpose of the Pegasus Project we have been hosting ICCA sessions and students as and when required and we and they can be justly proud of their hugely impressive results. The success rate for ICCA students is spectacular: of those sitting the exam in April this year, 91 per cent of ICCA candidates sitting the criminal law exam for the first time passed (average for all providers 69 per cent) with 84 per cent against an average of 62.4 per cent for the civil paper.

I must make a special mention of the contribution the Library continues to make to the work of all our members. It remains a marvellously tranquil and welcoming place in which to study and I have been pleased to note that the numbers using it have markedly increased since before the redevelopment of the Treasury Building. The advice and online services make its learning readily accessible to everyone.

Our volunteer advocacy trainers have provided sterling service at advocacy weekends in and outside the Inn, all the while continuing to insist on the highest standards for themselves. Yet again our volunteer scholarship interviewers have performed wonders in interviewing all scholarship candidates. This year we interviewed 337 candidates for Bar Scholarships and awarded 120 scholarships. In addition to the actual interviews all volunteers were asked to undertake EDI training. This tremendous effort demonstrates the immense commitment we share to increase social mobility, inclusion and diversity at the Bar.

THE FUTURE

So, what does the future hold? On a parochial level I look forward to supporting the Inn’s work with students, pupils, newly qualified barristers and established practitioners. The increased range of activities mean we will need as many volunteers as possible. If you have not thought of contributing to the Inn in this way before, now is the time to do so – you are needed! I also look forward to promoting our links with the Caribbean and the US on our visit to Trinidad, Barbados and Washington in October, to fill some of the gap left by the forced cancellation of Master Deborah Taylor’s tour last year following the death of Her Majesty the Late Queen Elizabeth II.

As an Inn we are aware there are many challenges ahead. Following the pandemic, it is no secret that many barristers’ working patterns have changed and with that comes a need to look at whether the professional accommodation we provide meets their needs The requirements of chambers who spend more time working from home will be different. The greater appreciation of the access needs of some of our colleagues will cause us to look again at what can be done to meet them. We have begun a dialogue with the City of London planning authorities to explore possibilities for enhancing access to listed buildings on our estate.

I have already mentioned the issue of the timing of Call. I anticipate this may lead to a wider discussion about access to the profession and what we can do to enhance it. If we do not find ways of achieving that for ourselves we may find solutions are imposed on us.

Finally we live in times in which the value of the rule of law in a democratic society, and of lawyers’ place in that, is increasingly questioned both in this country and overseas. We should all regard it as a professional duty to explain to all who will listen, and even more so those who do not, why what we as a profession do is so important in the interests of society as a whole.

THANKS

None of what I have described nor the many activities that I have not would be possible without the dedicated and loyal work of our staff under the leadership of Greg, Henrietta, Richard, David, Gail, Rob, Pete, Sean, Vicky and Bob, with special thanks to Jennie and Wanda without whom nothing on the Treasurer’s (and I suspect Sub-Treasurer’s) diary would ever be attended to!

It remains a great privilege to be your Treasurer and I am looking forward to seeing as many as possible of you during the rest of the year. My only regret is that it is going so quickly!

Sir Robert Francis KC Master Treasurer

NBJ are proud to have delivered the complex specialist joinery package for Project Pegasus, providing high quality woodwork to the Inner Temple library, learning and training facilities for generations to come.

The Inn’s two equally stunning rooms, the Boswell and Chaucer, are available every day and are located on the third floor of 3 Dr Johnson’s Buildings which was built in 1858 by the architect Sydney Smirke.

Whether you are in town for business or pleasure, our accommodation, along with the Pegasus Bar which is open Monday-Friday, o ers respite from a long day of meetings or sightseeing.

Choose from the four-poster luxury of the Chaucer or the more modern Boswell with views overlooking Temple Church.

020 7797 8230 | venuehire@innertemple.org.uk | innertemplevenuehire.co.uk

per room per night

MEMBERSHIP OF THE INNER TEMPLE

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple is proud of its history as a professional and collegiate community and its core purpose of providing education for students, pupils and established barristers.

MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS:

Subsidised training in a state of the art lecture theatre and modern training rooms

Use of the Inn’s Library and reciprocal arrangement with the other Inn’s Libraries

Access to the Inn’s subsidised collegiate and networking events

Access to lectures eg Reader’s Lectures and Social Context of the Law

Access to the Inn’s professional societies eg History Society, LGBTQ+ Society, Inns of Court Alliance for Women, Employed Bar Forum

Eligibility for Pegasus Scholarships (up to five years in practice)

Eligibility for the Paris Bar Exchange (up to seven years in practice)

Subscription to the digital quarterly newsletter – Innerview

Subscription to the Yearbook

Member discount on hire of the Inn’s rooms for private events

Sponsored discount on hire of the Inn’s rooms for legally related events

Subsidised lunch in Hall from Monday – Friday during term time

Student discount of 20 per cent off lunch in Hall (excluding drinks)

Student discount of 20 per cent off food in the Pegasus Bar (excluding drinks)

Use of the Inn’s Garden (subject to terms & conditions)

Use of the Inn’s Car Park (subject to terms & conditions)

Eligibility to marry in the Temple Church

Access to the Inns of Court Societies: Bar Lawn Tennis, Bar Golfing Society, Bar Choral Society

Access to discounts at the Smithfield

Nursery and Tiny Tree Day Nursery

Access to members’ overnight accommodation booking portal

For further details: innertemple.org.uk/members

Lecture Theatre © James Brittain

Hall © James Brittain Library © James Brittain

Lecture Theatre © James Brittain

Hall © James Brittain Library © James Brittain

WE’RE GOING WHERE THE SUN SHINES BRIGHTLY…

SO WHY DO TREASURERS AND THE SUB-TREASURER TRAVEL ABROAD EVERY YEAR ON BEHALF OF THE INN?

By the Sub-Treasurer Deborah

Deborah

In my time Treasurers have visited Singapore and Washington in 2018; Mauritius, Malaysia, Singapore and Washington in 2019; Washington in 2022; and Delhi and Goa (the latter for a Commonwealth Lawyers Conference) in 2023, with a visit to Barbados; Trinidad and Tobago; and Washington still to come at the time of writing The international programme was disrupted by the pandemic and last year a joint Amity Visit with Gray’s Inn to the US and an Inner Temple visit to four Caribbean countries were cancelled because of the sad death of Her Majesty The Late Queen two days before we were due to set out. In the past there have been visits to even more exotic locations.

These visits are not based on the random wishes of successive Treasurers The equivalent of a ‘business case’ is prepared when deciding where a Treasurer might visit This is carefully considered by the International Committee, at least since 2017 when it was established, who might endorse it but might equally suggest an alternative itinerary, which they believe might be of more practical benefit to the Inn. Affordability is an issue too, of course, and the Finance Sub-Committee also play a role when determining the international budget for the following year

Supreme Court of India 2023

How do we select where Treasurers should visit? The whereabouts of Inner Temple members, alumni for want of a better word, is one criterion. Nationality is not the same as current location and sadly not all our members stay in touch or update us on changes of address. But broadly, by location, our top ten countries are Malaysia, Singapore, Ireland, India, the USA, Mauritius, Pakistan, Australia, the Bahamas and Bangladesh. In some jurisdictions we have Overseas, Honorary and Academic Masters of the Bench in very senior positions. In Malaysia, Singapore and Mauritius we have very active alumni associations in place and there is a longstanding history of useful two-way visits with the American Inns of Court (our visits to Washington are usually in the context of attending their annual Celebration of Excellence at the US Supreme Court, which is a valuable networking opportunity).

In some jurisdictions we have Overseas, Honorary and Academic Masters of the Bench in very senior positions.

Master

Taylor, Emilia Clegg, Sub-Treasurer at AIC 2022

Master

Taylor, Emilia Clegg, Sub-Treasurer at AIC 2022

But alongside keeping in touch with our alumni, these visits are also about making new contacts; telling them about the role of the Inns of Court; and discussing with them issues such as the rule of law, ethical legal practice or judicial independence. This is never a question of preaching, but always about exchanging best practice. In some areas we may feel we are thought leaders, but in others we have much to learn from what is happening in other jurisdictions – such as impressive technological advancements in the Indian courts. In some locations our Treasurers give speeches or presentations to students or other audiences. For example, in 2019, Master Anthony Hughes gave several speeches on making the rule of law a daily reality and our current Treasurer spoke about assisted dying and building a healthy nation earlier this year. Sometimes the visits tie in with incoming visits to Inner Temple from overseas jurisdictions.

This is never a question of preaching, but always about exchanging best practice. In some areas we may feel we are thought leaders, but in others we have much to learn from what is happening in other jurisdictions.

These visits are opportunities too to market Inner Temple as a venue in London for events that overseas jurisdictions might be contemplating; to promote UK legal products, lawyers and the use of London as a location for legal transactions; as well as to supplement the work of the Bar Council and – as appropriate – the Law Society in making the case for opening up the global legal services market. We are not primarily recruiting students, but where a talented international student is considering a career at the Bar of England and Wales it may be possible to offer relevant advice. And we can provide information (which is regularly sought from us) about how qualified foreign lawyers can practise at the Bar of England and Wales, either by transferring or by applying for temporary Call to act in specific cases in England and Wales. Treasurers can often also identify suitable candidates to become Overseas, Honorary or Academic Benchers on such visits or detect suitable opportunities to consider advocacy or other forms of training. We can advertise initiatives such as The Inner Temple Triennial Book Prize, which is steadily gaining international prominence. And when it comes to a big global initiative, such as the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta in 2015, it is no use starting preparations at the last minute – the contacts to make things happen must be in place well in advance.

We are now regularly reporting on Treasurers’ overseas visits, so we have a permanent record of itineraries, what has been achieved, who has been met, and so on. This gives the International and Executive Committees an opportunity to evaluate the visits and determine what works well and what does not. The visits can be quite hard work – the schedules are often packed and the logistics demanding: the overall exercise is often very tiring. They can also be fascinating glimpses into how legal business is done elsewhere, as well as an opportunity to connect with the Inn’s members overseas. But Treasurers do not take these visits on for their entertainment value!

Greg Dorey CVO Sub-Treasurer

Master Treasurer at the Delhi High Court 2023

Master Elizabeth Gloster on a panel at AIC 2018

Master Treasurer at the Hingorani Foundation Event 2023

Master Treasurer at the Delhi High Court 2023

Master Elizabeth Gloster on a panel at AIC 2018

Master Treasurer at the Hingorani Foundation Event 2023

THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF THE LAW: IS IT BETTER TO REVIEW OR MONITOR TERROR LAWS? THE UK

AND AUSTRALIAN POSITIONS COMPARED

From a Social Context of the Law discussion held on 20 November 2022 between Jonathan Hall KC and Dr James Renwick AM CSC SC, moderated by Master Rory Phillips

Rory Phillips KC: Welcome to the latest in our Social Context of the Law series. Today, our topic is terrorism, or to be more precise, the legislation that states have introduced to deal with terrorism in its various manifestations. And sharpening our focus further, we’re going to concentrate on two democratic states with much in common, including shared history and values, but with distinct cultures and constitutional arrangements, namely the United Kingdom and Australia. Both states have, of course, had to confront the problem of terrorism, domestically and internationally, and both have turned to the independent Bar to undertake the scrutiny of existing or proposed legislation in this field. However, their approaches have been different, such differences extending, as we’ll hear, considerably beyond the language used to describe the two roles: Reviewer in the UK, Monitor in Australia.

This evening we’re very fortunate to have with us both a distinguished former occupant of the Australian position of Independent National Security Legislation Monitor, Professor James Renwick, and also the current Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation in this country, Jonathan Hall KC.

Let me give them both the very briefest of introductions. James Renwick is on record as wanting first to be a poet. However, he took his father’s advice and turned to law. After working in government, he was called to the Bar in 1996 and developed a wide-ranging practice in constitutional, administrative, and commercial law. He became senior counsel in 2011, he has a doctorate in constitutional law from Sydney University, and since 2012 has been adjunct professor at the Australian National University in Canberra. He became Australia’s third Independent National Security Legislation Monitor in 2017, and served until 2020, issuing a number of reports on a wide range of topics during his tenure. I should add that he is a long-time naval reservist, and in 2019, was awarded the Conspicuous Service Cross.

Jonathan Hall was called to the Bar in 1994, took silk in 2014 and is a member of 6KBW College Hill. And like many able criminal practitioners, he has expanded his practice into the fields of public, and specifically national security, law. He was first appointed as the UK’s Independent Reviewer in 2019 and was reappointed earlier this year. He has published reports, articles, and responses on a wide variety of issues in addition to his annual reports – his most recent response being to the public consultation on the vexed topic of non-jury trials in Northern Ireland.

Jonathan Hall KC: I’m bound to say I approached this topic with neuralgic sensitivity, because as James Renwick will no doubt quickly and very justly point out, perhaps by reference to the unlawful prorogation of parliament under Boris Johnson, or the quick turnover of recent governments, that relying on convention and practice is rarely enough. And what he would be referring to is the difference between our roles, and certainly a difference that is important to lawyers. When he was the Reviewer, James not only had staff and premises, but he had a whole statute, the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor Act 2010, which defines his job and gave him powers to carry it out. The position here is very different.

A single section of the Terrorism Act 2006 requires the government to appoint a person who must deliver an annual report for eventual submission to parliament, and that’s it. So, the effectiveness of the Reviewer in the UK depends upon past practice and convention, and the relationship that each Reviewer has with the government, the police, parliament, the public, the media, and so on. The truth is that if I asked for secret information relevant to my job, and the government or the police refused to let me see it, I could not invoke a statutory power to compel them to do that. That is something that James could have done – I don’t know whether he ever had to do it, but he certainly had that arrow in his quiver.

The effectiveness of the Reviewer in the UK depends upon past practice and convention, and the relationship that each Reviewer has with the government, the police, parliament, the public, the media, and so on.

By contrast, I could only invoke the role itself, as it has become defined by Reviewers of the stature of Lord Carlile, who took the role on after 2000, Lord Anderson, and Max Hill, now the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). And I could say to the government: “Has it come to this? And how do you think parliament, or the media would respond if they found out that you were keeping things back from the terrorism Reviewer?” I haven’t had any problems, but that would be what I would have to fall back on.

I’ve mentioned the media twice now, and deliberately so. Having less formality, the UK Reviewer has been free to develop his/her role. When the first terrorism attack took place after my appointment in 2019, I remember requests for radio interviews coming in from the Radio 4 Today programme, and David Anderson texting me to say, “Over to you.” And it has become an outward-facing role. Very different from Australia. When I was appointed, I picked up the 3,000 or so Twitter followers that Max Hill had attracted since he took over from David, and like them I tweet about terrorism. That’s how Rory, I suspect, knows about what I said last week about non-jury trials. Very different from Australia.

In 2020, the government started to promote a series of counterterrorism Bills on terrorist offenders in prison and on release. And I was being asked for my views behind the scenes, but I thought: “If I have got views on legislation going through parliament, why not publish some of those views?” So, I’ve started the practice of publishing notes on counterterrorism legislation on my website, advertised via Twitter, and these are very frequently picked up and cited in parliamentary debates. Again, very different, I think, from Australia. Indeed, there’s no piece of counterterrorism legislation on the statute books, or counterterrorism Bill that’s currently presented to parliament, where an MP, or a Peer, or a parliamentary committee, or a journalist, or an NGO, or a member of the public, cannot in principle contact me and get, hopefully, an informed and certainly independent view. Of course, I’m not saying the UK system is perfect, and it wouldn’t be for everyone. Fundamentally, in the UK, it comes down to a simple duty to do an annual review of the terrorism Acts. This brings a sort of completeness in having to compile a 200-page document every year on how terrorism laws operate.

By contrast, I’ve noticed that the first Australian Monitor, Brett Walker SC, did lay down a comprehensive analysis of some of the more contentious Australian counterterrorism powers in his first annual report, and believe me, there were a lot. In 2019, researchers calculated that between 2002 and 2007 in Australia, a new counterterrorism law was passed every six or seven weeks. But since then, the annual reports of the Australian Monitor have shrunk to about 20 to 30 pages, not including annexes, setting out more or less what the Monitor has done in that year. In fact, over the last few years, it seems to me that the real function of the Australian Monitor is to produce reviews that are focused on particular topics. And I think that observation is consistent with the analysis by the academic Jessie Blackburn, who has written extensively about our respective roles.

So, the glory of James’s very distinguished three-year term was his review of the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018. This was an Act that underpins their ability to do the spookier end of telecommunications spy work. It was an Act that, even when it was passed by the Australian Parliament, was known to be unsatisfactory because of a lack of parliamentary scrutiny, and it was passed to James to review after its enactment by this powerful intelligence committee. It’s a brilliant report, and I could also point out James’ fantastic review of sentencing of child terrorist offenders, or of citizenship loss, but there was, on his watch, no review of the whole landscape of terrorism legislation. So, I’ll end my remarks with a general comment and a mischievous comment.

The general comment is that the UK Reviewer, my role, is able to speak publicly and independently about terrorism generally, to inform the debate generally, and to inform debate specifically when bills are before parliament, whereas the Australian Monitor has more formal powers, but a narrower output. The mischievous comment, and this is where I’ll end, is that the Australian Monitor role may even have an adverse effect on Australian counterterrorism legislation, because the Australian Parliament knows that, after it is enacted, un-thought-through legislation, it could in principle, ask the Australian Monitor to pick up the pieces.

Dr James Renwick SC: Let me answer the question posed in the debate immediately. It is better to monitor than it is to review. It’s good to review, but it’s important to do both, not least because of the support each role gives to the other. So, may I immediately acknowledge with thanks the remarkable quartet of Reviewers, three of whom are here tonight, that you’ve had since 2001. Before coming to four key differences between the roles, all where I think we might have the edge, can I give you a couple of bits of context you may not be aware of, and one of them is that in Australia, it’s almost a pastime to see a problem and pass a law.

It is better to monitor than it is to

review. It’s good to review, but it’s important to do both, not least because of the support each role gives to the other.

Since 9/11, we have passed over 130 counterterrorism and national security laws. I read with wry amusement what Lord Justice Haddon-Cave said last year that English law has become increasingly complex, unclear, and inaccessible. And then I looked at the figures: 50 to 70 statutes a year, admittedly some quite long, enacted in Britain. In Australia, we last passed about 70 laws in 1955. In recent years, we generally present over 200, sometimes up to 250 bills, and enact more than 150. So that’s one important difference, and it’s relevant to the question of whether you comment on bills.

Another substantive difference is that when you have a terrorist act which results in death, you punish it or you prosecute it as murder, whereas we prosecute it as terrorism. On the threat of terrorism, I agree there’s a risk of overstating it, but I think one thing we have in common is neither the Reviewer nor Monitor have ever been guilty of that. Whether you take radical Islamist terrorism, or the strange collection of people who make up extreme right-wing terrorist groups, they are not an existential threat to either nation. Whereas espionage and foreign interference are increasing threats to our nations. Of course, I’m not downplaying the horror of terrorism.

Coming then to the strengths of the Monitor role over that of the Reviewer. And I call in aid here the view of the French philosopher who once said, “Yes, yes, I know it works in practice, but the question is, does it work in principle?” It seems to me there are four advantages the Monitors have over the Reviewers.

The first, and critically, is: Monitors have public hearings and Reviewers don’t. And so, very simply, the format was you would announce an inquiry, you would invite submissions, and then you would quiz the agencies in a confidential session. The other thing, for those of you here who are interested in persuasion, and public policy, is the language of criticism. When I did a public hearing, I would set out my tentative views and say something like: “I’m inclined to think that the law does or doesn’t pass muster by reference to the statutory tests of proportionality, necessity, and proper protection of human rights.” And by using that not-soconfrontational language, I felt that was more effective.

The second advantage is not commenting on bills. You can see by the number of bills that if I and my predecessors had spent our time commenting on bills, we would have got nothing else done. And that’s just a function of how many are passed. The second point of practicality is the time between when a bill was introduced, and when it became law, has ever decreased over time. The Bali bombing in 2002: 88 Australians killed out of 200. It took six to nine months to

pass through the legislative process. After the Christchurch attacks in more recent years – an Australian terrorist attacking people in mosques – we passed a law within a week, outlawing live streaming of terrorist attacks. And so, as a practical matter, even if the Monitor wanted to get involved in commenting on bills, you’d simply be run over.

Two other points: the power to obtain relevant material. I do think this is important, and it’s not just a matter of convention. Now, it is true I only once had a problem with an agency head who I thought was getting a little bit overenthusiastic and suggesting he wouldn’t give me what I was entitled to. So, I said to him, “If what you’re saying is you want the comfort of a subpoena, I’m happy to give you one. Is that what you would like?” And he said, “Oh, we always comply with the law!” And I said, “Of course!”

So, it is actually useful to have those powers, and a good test is what the Republic of Ireland are looking at the minute. They’re proposing to set up an Examiner. I put in a submission saying I thought it was really important they had statutory powers. I think the current version of the Bill suggests the intelligence agencies in the Republic of Ireland could refuse to give the Examiner material. I think that’s a fundamental flaw, if that were to go forward. And it just seems to me that – and this is the point about convention – conventions sometimes do break down when you most need them.

And the fourth and final point is this: under the Monitor Act, the government had an obligation to publish, or to table in parliament, the public report. I could also do a secret report, which I did on a couple of occasions. But the public report had to be tabled within 14 days. A report was done. It was in the public debate. It got things moving. Here, as I understand the practice, the government tends to withhold the tabling of the report until it has also come up with its response. And it just seems to me there is a risk that that involves pulling the teeth out of the report. So, it seems to me, that as David (Lord Anderson of Ipswich KC) said, respected independent regulators continue to play a vital and distinguished role, that in an age where trust depends on verification rather than reputation, trust by proxy isn’t enough. Hence the importance of clear law, fair procedures, rights compliance, and transparency. Exactly, I would say, and at least until that is done, it is better to monitor than review.

Respected independent regulators continue to play a vital and distinguished role, that in an age where trust depends on verification rather than reputation, trust by proxy isn’t enough. Hence the importance of clear law, fair procedures, rights compliance, and transparency.

Jonathan Hall KC 6KBW

Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation

Dr James Renwick AM CSC SC

Former Independent National Security Legislation Monitor of Australia, Honorary Professor of Law at the Australian National University

Rory Phillips KC 3VB Master of the Bench

For the full video recording: innertemple.org.uk/terrorlaws

Picture your event here!

SEARCYS VENUE COLLECTION

A business event or a celebration, a get-together or a birthday party, a meeting or a private dinner. Since 1847.

SPEAK TO SEARCYS EVENTS TEAM 020 7101 0220 | EXCLUSIVE.EVENTS@SEARCYS.CO.UK

SEARCYS GIFTS

Perfect for any occasion – from dining and afternoon tea experiences, to Searcys Champagne and English Sparkling Wine and signature tea sets.

THE INNER TEMPLE LGBTQ+ SOCIETY

The Inner Temple LGBTQ+ Society has been established with the principal objective of encouraging visibility and facilitating an inclusive social environment for the Inn’s LGBTQ+ members and allies. The Society itself is a self-sustaining, membership-led initiative and will seek to arrange a limited number of events and networking activities each year.

Membership of the Society is open to all members of the Inn, including students, and staff, of any sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression or any other characteristic.

The Society is overseen by Master Jeremy Richardson (His Honour Judge Jeremy Richardson KC), Recorder of Sheffield and member of the Equality, Diversity and Inclusivity Sub-Committee.

The Society’s Officers for 2023 are:

PRESIDENT:

Dr S Chelvan

33 Bedford Row, Call 1999

LIBRARIAN:

Master Craig Hassall Park Square Barristers, Call 1999

TREASURER:

Cameron Stocks

Gatehouse Chambers, Call 2015

SECRETARY:

Ife Kubler-Agyemang Doughty Street Chambers, Call 2018

STUDENT AND PUPIL LIAISON OFFICER: Mohamed Hussein Iman Student member

LGBTQ+ dinner September 2022Membership of the Society is open to all members of the Inn, including students, and staff, of any sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression or any other characteristic.

For more information and to register as a member of the LGBTQ+ Society: innertemple.typeform.com/lgbtqsociety

The Joint Inner and Middle Temple LGBTGQ+ reception on 22 June 2023

Master Jeremy Richardson speaking at the LGBTQ+ dinner in September 2022

The Joint Inner and Middle Temple LGBTGQ+ reception on 22 June 2023

Master Jeremy Richardson speaking at the LGBTQ+ dinner in September 2022

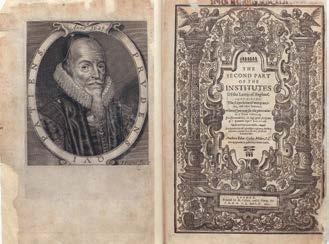

AAN ELIZABETHAN MYSTERY: THE LEVER CANON LAW MANUSCRIPT AT INNER TEMPLE

By Master Norman DoeYou might be familiar with modern mystery novels set in Tudor England – such as CJ Sansom’s series featuring Matthew Shardlake of Lincoln’s Inn; SJ Parris’ blockbusters with Giordano Bruno and Queen Elizabeth’s spy-ring; and then Edward Marston’s Nicholas Bracewell, theatre manager in Elizabethan London.

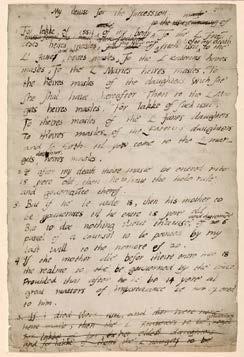

We have our own Elizabethan mystery at Inner Temple Library: a manuscript on the canon and ecclesiastical law of the Church of England, which regulated so much of people’s lives from baptism to burial, from marriage to wills. The title in the manuscript is: The assertions of Ralph Lever touching the canon law. Lever was born c. 1530 and died in 1585. These 55 years are crucial in the evolution of English ecclesiastical law. It was the hot topic. Under Henry VIII, parliament enacted statutes: to terminate the papal jurisdiction in England; to withdraw England from the European continental Church of Rome; to establish the Church of England as an independent national church; and to assert the royal supremacy in matters ecclesiastical. It was the Brexit of its day.

However – and Brexit legislation mirrored this – to fill the legal vacuum left by the demise of Rome, the Submission of the Clergy Act 1533 allowed the pre-existing Roman canon law to continue to apply to the new English Church (if not repugnant to the laws of the realm) and until reviewed by a royal commission.

No commission was appointed. Parliament provided for a review in 1535, 1543, and 1549; and by 1553, a commission had compiled a new code – the Reformatio Legum Ecclesiasticarum; but the project lapsed with the return of England to Rome under Mary I. The draft code was resurrected when the Church was re-established under Elizabeth I and published in 1571, but parliament rejected it. The 1533 Act, revived on Elizabeth’s accession, also provided for the clergy Convocations of Canterbury and York to make law, with royal assent, in the form of canons. But it wasn’t until 1603/4 that Convocations made a new code of canons approved by James I – hardy things – they were not revised till the 1960s.

Also, in 1563, Convocation endorsed the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, and as the years unfolded parliament enacted many anti-Roman Catholic laws. The new Elizabethan church settlement was summed up famously by Richard Hooker (Master of the Temple in the 1580s) in his Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity

These landmarks provide the legal setting for our Inner Temple manuscript. Ralph Lever was born in Lancashire, the fifth of seven sons. After Eton, like three of his brothers, he entered St John’s College, Cambridge: BA 1548 and, after becoming a fellow 1549, MA in 1551. A Protestant reformer, he was exiled under Mary. On return, he resumed his fellowship and later married.

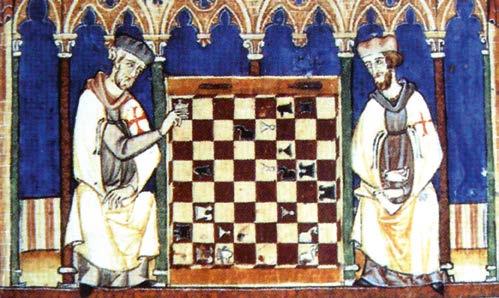

Lever had wide interests. In 1563, he wrote a book about a board game “for the honest recreation of students and other sober persons in passing the tediousness of time to the release of their labours and exercise of their wits”. He wrote another in 1573 – The Art of Reason, Rightly Termed Witcraft: “a perfect way to argue and dispute” on Aristotelian lines; it is one of the earliest books on logic in English.

He wrote another in 1573 –

The Art of Reason, Rightly Termed Witcraft: “a perfect way to argue and dispute” on Aristotelian lines; it is one of the earliest books on logic in English.

A colleague at St John’s (its master) was James Pilkington, also a Lancastrian, a reformer in exile, and Bishop of Durham from 1561. He appointed Lever as his chaplain, Rector of Washington, Archdeacon of Northumberland, and Prebend at Durham Cathedral. In 1572, Lever challenged the latter’s episcopal visitation articles, was summoned to court, but resigned as archdeacon to avoid censure.

A commissary on Pilkington’s death, in 1577 Lever is at loggerheads with the dean and chapter over leases. He resigns his offices to be Master of Sherburn Hospital. Founded by the Bishop of Durham 1181 for leper monks, and rebuilt as alms-houses, Lever secured an Act of Parliament 1585 to: incorporate the hospital; allow the bishop to make rules for it and appoint its master; and oblige the master to nominate the brethren who took an oath to obey the bishop’s rules.

In 1583, Lever also sought reform of the cathedral statutes at Durham that, according to him, were “defective in sundry points touching religion and government”. But the dean and chapter were hostile, and Lever died in 1585 before his new scheme was considered. He was buried in the cathedral.

Alongside trying to reform Durham cathedral statutes, and securing the Act of Parliament for Sherburn Hospital, it would not be surprising if Lever turned his attention to the national ecclesiastical law. Hence the tract, full title: The assertions of Ralph Lever touching the canon law, the English papists and the ecclesiastical officers of this realm, with his most humble petition to her majesty for redress. The Inner Temple text is among its Petyt manuscripts bequeathed to the Inn in 1707 by William Petyt, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, Treasurer here 1701–02, and buried at the Temple Church. But the collection gives no date for the tract, though the dates of neighbouring manuscripts in the volume – also on church affairs – range from 1573 to 1580. The text is not signed by Lever, so we assume it is a copy, copyist unknown.

Questions arise about the date and authorship of the tract. Conway Davies’ catalogue of Inner Temple manuscripts (published 1972) lists the tract but is silent as to date. Davies (a Welsh historian from Llanelli) made notes on the Petyt manuscripts, now among his papers at the National Library of Wales. The notes to the Lever tract are the same as those published in his 1972 catalogue – except that he has ‘nd’, presumably for ‘no date’, which does not appear in his published catalogue. The Bodleian Library did a full search of all their online and published catalogues, but this has not traced any reference to a manuscript matching Lever’s; Cambridge University Library did the same – again, no trace.

Beyond these catalogues, scholars have dealt a little with the tract as part of their wider studies, but they differ on its date, authorship, and classification.

First, John Strype (d. 1737), in his Annals of the Reformation in England (1725), dates it to 1562, and presents it among “Papers prepared” for the Convocation of 1563. He describes Lever as “a learned canonist” who wrote the tract to regulate the canonists, canon law, the abuse of excommunication, and “the unjust dealings” of some judges. But Strype did not find Lever at that Convocation, “or that it came before the synod”, though he presents it as being “agreeable to the matters… relating…to a reformation of things amiss in the church, and very probably offered in this juncture”. Strype then gives the title and text without further comment. Lambeth Palace Library has no record that the tract is among their collections relating to the Convocation of 1563.

Second, is the great modern historian of the canons of the Church of England, Gerald Bray. On the basis of the Petyt manuscript at The Inner Temple, in 1998 Bray dated the tract to 1563, though Bray refers in a footnote to the tract as it appears in Strype (who dates it 1562). Bray does not mention Conway Davies.

Bray places the tract firmly in the reformers’ camp. He says, it was not written by a “canonical fundamentalist” for whom canon law had the same status as doctrine. The reformers protested against such a view and Bray writes: “No-one put it more clearly than the anonymous canonist whose assertions have come down to us as the work of Ralph Lever”. Yet, Bray then says the tract is “attributed to Ralph Lever, though it seems virtually certain he did not write it”.

Crucially, Bray gives no reason for this claim, though he describes Lever as “a convinced protestant…unhappy with the pro-Genevan tendencies of a number of the returned Marian exiles”. Like Strype, Bray links the tract to the 1563 Convocation which had “a clear desire for a reform of the ecclesiastical laws along what would later be called ‘puritan’ lines”. However, later Bray also states: “Nor is it known when it was composed, though it must have been in or shortly after 1563”. Bray then gives a brief overview of themes in the tract.

Third, another date, another classification. In 2008, David Marcombe dated the tract to 12 January 1585, citing The York Book at Durham University Library. Indeed, Marcombe had argued in his 1973 doctorate, on the history of the Dean and Chapter of Durham Cathedral, that Strype had “incorrectly” dated it to 1562. For Marcombe the year 1585 makes sense because the 1580s coincide with Lever’s proposals for legal reform at Sherburn Hospital and Durham Cathedral.

The York Book is now in Durham Cathedral Archive. In it is a manuscript of Lever’s petition with the same heading as that at The Inner Temple. The heading is followed by the date 12 January 1584, not 1585. But this date is inserted by a different and later hand to that in the manuscript itself. However, unlike The Inner Temple’s “Ralph Lever” appears at the end of the Durham manuscript in the same hand as that of the manuscript itself, not in the hand of the date, as if it were signed by Lever. But the manuscript is a copy, so it is not his signature.

AFrom Durham to London: The National Archives. The State Papers show that Lever petitioned the Privy Council once in 1577 (the Durham dispute over leases), twice in 1582, once in 1583, and a fourth of uncertain date (all to resolve a dispute with the Bishop of Durham), and in 1585, on the bill for Sherburn Hospital. There is no sign of our petition. Charlotte Smith at the National Archives sums up: “no definitive answer but, based on the patterns of correspondence, 1562/3 looks too early; but circa 1585 would make sense”.

Back to Marcombe. He thinks Lever was the author; and had “sometimes radical Protestant beliefs”; engaged in “chronic contentiousness”; and “approved of continental Protestantism”. But he believed the English Church sacramentally and doctrinally authentic; and thought the Calvinist church polity in Geneva and other reformed churches was “not so fit for our state as our own”. Also, Lever was “a staunch opponent of Catholicism” and “of the continued use of canon law”, considering those who “upheld the canon law [as] Papists and traitors”.

However, Lever and his work are rather less puritanreformist than these scholars portray. Our manuscript has 21 paragraphs, each contains numerous assertions. Once more, it deals with canon law; English Roman Catholics; and church officers. There are small differences in wording between our manuscript and that at Durham; and the Durham manuscript has two more paragraphs, ie, 23 in all.

Most of his assertions are orthodox, they simply articulate the ecclesiastical law of Elizabethan England in statutes, canons, and so on; but he does not expressly cite any of them. Also, while Strype and Bray style Lever a “canonist”, he was not trained in canon law: the faculties of canon law at Oxford and Cambridge were dissolved under Henry VIII. Nor was he a civil lawyer; he neither trained in civil law at university nor practised law in the church courts. Though as Archdeacon of Northumberland he presided as judge in his archdeacon’s court.

First, the canon law. By this, Lever means the Roman canon law. On the one hand, he criticises it: “The canon law… made by the church of Rome is in exceeding many points contrary to the written Word of God and repugnant to the positive laws of this realm”. It “does chiefly… establish the bishop of Rome his usurped… authority over all Christendom”. And it “breeds… superstition and a certain security that there is no further increase of faith required, but to believe as the church of Rome believes – it is rightly termed ‘the pope’s laws’”. But Lever gives no specific examples of how these offend scripture or English law.

On the other hand, Lever accepts that some papal canon law is rooted in the Bible and natural law, and it applies in England as part of the law of the realm. A more nuanced stance than Marcombe’s. Lever writes: “the rules, ordinances and decrees…in the books of the canon law and yet have warrant by the Holy Scriptures and by the laws of nature, and thereupon are in force here at this day, being established by act of parliament to this end, that justice may be ministered to all her majesty’s subjects, ought not to be named, reputed or taken by [those] subjects for foreign or popish laws, but for good and wholesome English laws”.

In this assertion, Lever’s ‘act of parliament’ is the Submission of the Clergy Act 1533, revived by Elizabeth in 1559. The passage is hugely significant, it is one of the first recorded Elizabethan statements that papal law continued to apply in England on the basis of that statute – a view common among later ecclesiastical lawyers, alongside the idea that papal law applied here before and after the 1533 Act on the basis of its reception in England, as held in Caudrey’s Case (1591).

Lever is not as radical as other reformers, like William Stoughton (d 1612), a civil lawyer favouring a presbyterian system of church polity: “the papal and foreign canon law is already taken away and ought not to be used in England”. Lever is more like Richard Cosin, Dean of Arches in the 1580s, who defended the English Church against presbyterianism and, like Hooker, cited many works by continental Roman jurists as well as medieval papal law.

Second, Lever on Roman Catholics. He writes, anyone who “believes the church of Rome…to be the true church of God,” and that it “does not err…in making of canons, laws and decrees, and in commanding the same to be…kept of all Christian nations, is a papist” and “not to be taken…as a subject in the church and commonwealth of England”. Likewise, anyone who professes “to be a loyal subject to Queen Elizabeth, and yet believes…the Church of England…is not…to be taken for, the true church of God” is no “member” of that Church.

Lever then defines the Church of England as “reformed by the written Word of God and established by public authority”; in it the sacraments are “rightly administered”, the gospel “truly preached” and liturgy “duly set forth according” to scripture. This all echoes the 39 Articles and Hooker – not the Calvinists.

Lever then defines the Church of England as “reformed by the written Word of God and established by public authority”; in it the sacraments are “rightly administered”, the gospel “truly preached” and liturgy “duly set forth according” to scripture.

Third, ecclesiastical officers. At the outset, he asserts the rule of law: church officers’ decisions must be authorised by law; but Lever (like Hooker) has a pluralistic view of law. In decision-making “the officer ought to assure himself to have warrant by the written Word of God, by the law of nature, by the law of nations, and by the positive laws of this realm”. Failure to do so derogates “from the law” and from the “legal authority” of the Crown, and in turn offends God.

As a result, all “officers and magistrates ought daily to meditate upon Holy Scripture and by it be directed in all their public affairs” and when “they…make laws”. Why? “For then does God stand in the congregation of princes and is judge among them when he directs them by his Holy Spirit and…holy word”.

Lever also opposes discretionary power under the law, “The commonwealth…is best governed that has most of her causes determined by law and fewest matters left to the judgment of her officers and governors”. Lever presages Dicey here.

Fourth, positive laws made by humans – they must pertain to matters on which scripture is indifferent; they must not conflict with scripture; the subject must obey them; positive laws may be changed only by lawful authority; and, as to legal reform, he says, a frequent and “needless change of law is most perilous”

The Durham manuscript here has an extra paragraph: “The equity of human laws is not impeached by the corruption of the judge”, echoing the 39 Articles: receiving the sacraments is not affected by the unworthiness of the minister.

Lever ends his discussion of positive law with an assertion about the purpose of all laws; it is highly theocratic: “The end of all laws, both divine and human, and the chiefest care that all princes, magistrates and lawgivers ought to have is this, to see the people of God to be taught, to give Caesar that is due to Caesar, and to God that is due to God”. These ideas too represent basic Anglicanism.

Fifth, he criticises, “bishops, their chancellors and other ecclesiastical officers” for excommunicating people “contrary to the written Word of God” and “such rules in the canon law…at this day in force by the positive laws of this realm”. Rather, the censure may be imposed only with “sufficient cause”; if “fault” is established; and by a “proceeding in law”. Or else, it is “contrary to all divine and human laws”, and “the conscience” of those censured “is free afore God”.

Excommunication was often the subject of reform at this time. The Canterbury Convocation in 1563, passed articles about delays attendant on it; in 1580, it heard an argument “concerning [its] reforming”; and in 1584, it passed a canon for the “reforming” of “some abuses in excommunication”. Obviously, the years involved in these reforms do not particularly help us in dating the Lever tract.

Sixth, the Court of Delegates, since 1533, the final appeal court in spiritual matters. Lever’s criticisms are: there was no appeal against a Delegates’ decision; its judges “misuse the sacred chair of justice”; and they do so without the “the fear of God”, the trust the Queen “did repose in them”, and “to great annoyance” of many. Some contemporaries of Lever also criticised the court, because, for instance, its judges did not usually give reasons for their decisions. But Lever is not as radical as Calvinists like Stoughton who sought its abolition. Finally, Lever’s petition: “For redress of all inconveniences and mischiefs which hereupon have happened…since the last parliament…your most humble suppliant makes petition to your most excellent majesty that such order be taken by this parliament assembled as does best agree to your majesty’s laws already established” etc. The petition seeks better administration of the law rather than reform of law itself. The Durham version of the petition is longer than this.

Excommunication was often the subject of reform at this time. The Canterbury Convocation in 1563, passed articles about delays attendant on it.

Petitions to parliament from this period, in its archives, were destroyed in the fire of 1834. Nor is our petition in parliament’s journals. So, for the date of 1562 or 1563 (Strype, Bray), the ‘last’ parliament was in 1559, which passed statutes on Lever’s topics, including those reviving the 1533 Act on Roman canon law and the Delegates Court, the Act of Supremacy, and the Treason Act. Also, as Lever notes, since that parliament there had been problems with its laws. “This parliament”, then, could that of 1563 summoned, as its record says, to uphold religion “notwithstanding that at the last parliament a law was made for good order to be observed in the same but yet…not executed” and to make new “plain, few, and brief” laws (also in Lever). Again, the parliament of 1563 addressed Lever’s topics: royal supremacy; treason; and excommunication.

Alternatively, if the Lever tract is from 1584/5, as Marcombe claims, then the relevant parliaments would be those of 1580 (the last parliament) and 1584 (this parliament). The 1580 parliament passed statutes requiring obedience to the crown, on recusancy, and on sedition. These subjects, too, continued to be problematic. The 1584 parliament considered a bill to ‘overthrow’ the church courts and it enacted statutes on the safety of the monarch, Jesuits, and pardons.

In short, the parliamentary agenda and legislation for 1563 and 1584 both contain subjects addressed by Lever and so seem not to help us to date his tract.

To sum up our Elizabethan mystery, Lever was a Protestant reformer, but entangled himself in the establishment, using it to reform his cathedral and hospital. The tract in The Inner Temple manuscript is difficult to date: 1562/3 or 1584/5.

Assuming Lever wrote it, his work on ecclesiastical law is mostly that of a classical Elizabethan Anglican; there is more in it of Hooker than Travers. He criticises the administration of the law rather than the law itself. Above all, it is significant because it is one of the earliest statements of the continuing applicability of Roman canon law in England under parliamentary statute.

What Shardlake, Bruno, and Bracewell would have thought of Lever and the tract, I know not. What is certain is this: the Lever manuscript is just one of scores of such items in the ecclesiastical collections at The Inner Temple library; to-date these items have not been studied as we have studied the Lever text here; and identifying and exploring these items, at the Inn, will enhance greatly our understanding of the turbulent history of the interplay between law and religion.

Norman Doe LLD Academic Bencher Professor of Law, Cardiff University Chancellor of the Diocese of Bangor

This is a shortened version of a lecture he gave at the Temple Church, 28 February 2023. Thanks are due to Master Mark Hatcher; and to Rob Hodgson and Michael Frost of Inner Temple Library who displayed the manuscript there. Matthew McMurray and Andrew Gray at Durham University Library, and Professor Charlotte Smith at the National Archives. The lecture is an up-dated version of N. Doe, Rediscovering Anglican Priest-Jurists: V – Ralph Lever (c. 1530–1585), 25 Ecclesiastical Law Journal (2023) 66–80.

For the full video recording: https://youtube.com/live/3SBQDz4ll9U

READER’S LECTURE SERIES: EXPERTS: LOVE OR LOATH?

By Master Robert AkenheadFrom a Reader’s Lecture held on 3 October 2022

Sir Robert Akenhead: I’ve come across every type of expert, good, bad, indifferent. If occasionally during this talk there are more memories of the bad ones, that is only because the experiences were more amusing with hindsight. And there is only so much praise that you can make of a good expert.

In the UK, there is a rule of court called CPR Part 35. It highlights the overriding duty owed by any expert, which is to the court. It specifically states: “Expert evidence should be the independent product of the expert uninfluenced by the pressures of litigation. Experts should assist the court by providing objective, unbiased opinions on matters within their expertise. The expert should not assume the role of an advocate.” There are different practices in the different fields of law which the specialist Bars in this country have regard to. There are protocols and guides applicable in medical or clinical negligence, different provisions in family court proceedings, different from those in the technology and construction field, in which I specialise.

It’s clear that the courts, particularly over the last five to ten years, are taking an increasingly robust line, mostly pre-trial, in relation to the admissibility and other aspects of expert evidence. There’s been a fairly recent case in the Technology and Construction Court – Dana UK Axle v Freudenberg – which actually excluded expert evidence at the trial, when it emerged that there was extensive non-compliance with the relevant guide. Mrs Justice Joanna Smith said: “The establishment of a level playing field in cases involving experts requires careful oversight and control on the part of the lawyers instructing those experts, all the more so in cases involving experts from other jurisdictions, who may not be familiar with the rules that apply in this jurisdiction. For reasons which have not been explained, there has been no such oversight or control over the experts in this case.” That was on one side. “So, the provision of expert evidence,” she said, “is a matter of permission from the court, not an absolute right, and such permission presupposes compliance, in all material respects, with the rules. I agree with counsel’s submission that the use of experts only works when everyone plays by the same rules. If the rules are flouted, the level playing field abandoned, and the need for transparency ignored, as has occurred in this case, then the fair administration of justice is put directly at risk.”

Obviously, experts need relevant expertise in their chosen fields – that, you might have thought, was a given. The relevant expertise does not necessarily involve degrees or doctorates or even memberships of relevant institutions. In my early days at the Bar, I was acting for a large firm of London City solicitors who’d employed some contractors to put in a mechanical electrical air conditioning in their big City offices, and things had gone wrong, and they employed an expert who was phenomenally helpful to me as we prepared the case. He produced a draft report which looked very good, but it contained a list of qualifications at the end, some of which I just simply didn’t recognise. I then asked him what they were, and it emerged that every single one of about 15 qualifications were ones you buy. Everything he was saying was perfectly sensible. I said: “What actually is your expertise?” And he said: “Well, all I’ve got is 40 years in the mechanical and electrical contracting business.” “Well, we’ll put that in, that is your expertise.” Because the report was good, it went in, and the opposition collapsed, and the case settled.

It’s clear that the courts, particularly over the last five to ten years, are taking an increasingly robust line, mostly pre-trial, in relation to the admissibility and other aspects of expert evidence.

So apart from expertise, a key factor is independence and impartiality. There’s nothing worse than the expert who starts being an advocate for his or her client and is in effect a ‘gun for hire’. The expert world is big business now, with large international firms competing for the work. Back in the day, a lot of experts, including medical experts, often came to it towards the end of their career almost as a part-time, pre- or post-retirement job. Lots of experience, but there are problems with that in that you can, as an expert, get out of date. But these large conglomerate firms can give rise to other problems, not least of which is conflict. Of course, there’s a dichotomy, isn’t there? Is an expert required to be independent partly because they’re paid – employed by one side or the other. And the expert owes the contractual duty to the clients to exercise reasonable care and skill. So, it’s a difficult one. And there will be conflicts from time to time, but decent experts should be prepared early in the case to start indicating if they have very real doubts about their client’s case in the area which he or she has been asked to talk about.

So, experts need to have the right qualifications. You would have thought that might be obvious. Medical, accounting, engineer, architect, other types of experts giving evidence about professional negligence, are often asked whether they have practical experience in whatever field they’re giving evidence about. Sometimes experts are overqualified. And some experts are Jacks-of-all-trades, so they’ve got lots of qualifications, and one or more of them might be relevant to the matter at issue, but they’ve never really done much on any aspect of their qualifications. When I was a judge, I considered it useful in my judgments to summarise my views about the experts in different disciplines. This was to explain to the parties who read the judgement why I preferred the evidence of one expert over another, rather than just a blanket conclusion that I preferred Dr X over Professor Y. A number of judges do that, and I think it’s a fair thing to do for the parties

Inevitably, lawyers, solicitors and barristers will be involved in the selection of experts. Nothing wrong with that as such, and potential experts will be asked questions identifying what their broad approach on the issues in a given case is. And it’s unsurprising because it’s a rare case in which a party introduces an expert whose evidence is against his or her own client. Once selected, the experts will often play a material part in the pleading of a material case, or defence, or the production of memorials in arbitration. But there is a dividing line between what the solicitors and barristers should be allowed to do, and shouldn’t simply tell the expert, “This is what you must put in your expert report.” Of course, it’s all privileged, it’s all behind closed doors, and it’s almost impossible, but very occasionally it comes out where an expert has been heard to say, “That’s what I was told to say.” It undermines the credibility of the party. There is a dividing line, which sometimes gets obscured.

Inevitably, lawyers, solicitors and barristers will be involved in the selection of experts. Nothing wrong with that as such, and potential experts will be asked questions identifying what their broad approach on the issues in a given case is. And it’s unsurprising because it’s a rare case in which a party introduces an expert whose evidence is against his or her own client.

We come now to technology, not just because I was in the Technology and Construction Court. As many of you will know, you get a lot of technology coming into the giving of expert evidence. It’s easy to have computer runs that tell you all the answers. “The computer says no”, and maybe the case goes your way. “Computer says yes”, it may not. Object lesson is where your expert, or you as expert, rely upon computer workings, make sure that you’re not open to that sort of attack. Because there, in court or an arbitration, you’re not going to be able to get your computer out, put the correct input in, run the computer and say: “Oh, there you go, it still shows something, not as bad as I thought, but...” You’re not going to be able to do that. It’s going to be too late in almost every case. Also, judges have got to be careful about running software themselves. When I was head of the Technology and Construction Court I was not as good as my ten-year-old granddaughter is now. And the problem is transparency, because if you do – I can use some of these systems that I come across – you never quite know the input that there has been which you haven’t checked. And there are often thousands of pieces of input.

I’m now going to draw matters to a conclusion. So, experts and practices that engage experts can be a minefield. Experts proving not to be properly qualified, experts acting as advocates. Once they’re on the witness stand, there’s not very much you can do if they’re going AWOL and away from the prepared speech. There’s not much you can do as counsel. And if you jump in and say, “I must ask you to stop”, that’s not really going to help if it’s your own witness. In fact, you won’t really be allowed to do it. So, you have experts under the thumbs of their legal and client teams, experts changing their mind, experts occasionally not doing a good, professional, and independent job. Truth is, of course, that probably the large majority of experts are decent people with the right qualifications, who behave independently and impartially. Judges have to decide who’s right and who’s wrong.

Sir Robert Akenhead Retired High Court Judge Master of the Bench

For the full video recording: innertemple.org.uk/loveorloathe

IN CELEBRATION OF THE CORONATION OF HIS MAJESTY KING CHARLES III

On 10 May, the Inn arranged a special service of Choral Evensong at the Temple Church to celebrate the Coronation of His Majesty King Charles III, followed by a joint reception hosted by the Treasurer, and the Treasurer of Middle Temple, The Rt Hon Lord Lloyd-Jones.

To commemorate the Coronation, the two Inns commissioned an illustrated Loyal Address in which they expressed their gratitude for Her Late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s devotion to the nation, and their loyalty and support to the new monarch as His Majesty embarks on his reign.

Master Treasurer’s address

The Temple Church Choir

Members in colourful traditional dress

Master Treasurer’s address

The Temple Church Choir

Members in colourful traditional dress

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLARS: THE FIRST CITY BANKERS?

By Master Gregory Jones

INTRODUCTION

A pilgrim visiting Jerusalem in 1172 puzzled: “It is not easy for anyone to gain an idea of the power and wealth of the Templars – for they, and the Hospitallers, have taken possession of almost all of the cities and villages within which Judea was once enriched… and have built castles everywhere and filled them with garrisons, besides the very many and, indeed, numberless estates which they are known to possess in other lands.” In that very same year, Henry II (1133–1189) entrusted to the Templars the so-called ‘care money’ deposited for the murder of Thomas Becket (1119–1170), enough to pay for the support of 200 knights in the Holy Land for a year. How was it that the Templars, committed to a life of frugality and abstinence, had become Europe’s wealthiest bankers?

THE REASONS WHY

Crusading was costly. At the Battle of Harim in 1164, only seven of the 67 Templars survived, and at La Forbie in 1244, only 33 out of 300 knights lived. Replacement costs were the equivalent to a ninth of the French monarchy’s annual income. Such costs impacted particularly hard upon the weaker kingdoms of Europe that had to look for loans. The Templars attracted a steady stream of recruits, many of whom handed over all their worldly possessions upon entry into the order. With pilgrims and would-be crusaders desperate for cash, the Templars began offering loans. In the case of a customer’s death, the Templars would also scoop up as executors of their estate. However, it was Pope Innocent II’s Bull of 1139, Omne datum optimum, that really kick-started the brothers’ rise from donated rags to vast riches. It not only exempted the Templars from paying a tenth of their produce in tithes, but also allowed them to collect tithes of their own. Their preceptories earned similar concessions from local lords across Europe, allowing them to levy tolls and customs on fairs and markets.

As monks, the Templars had the habit of obedience. Their oaths led to prudent lending. As celibates, they had no personal or dynastic ambitions to threaten jittery royal princes. Thus, with their financial acumen, Templars were often made royal almoners by European kings. Although they were monastic, owing obedience to their grand master and fealty to the Pope, nonetheless, it seems to have been accepted that they could work for monarchs whose interests diverged from each other and from those of the Pope. Under Phillip II (1165–1223), the Templars ran the French royal treasury, increasing revenues by 120 per cent. In various countries the Knights Templars formed much of national public service from time to time. Their financial network stretched beyond royalty. During the papal schism, Pope Alexander III (1159–1181) relied heavily on Templar loans and administrative services to stay afloat. When Pope Innocent III (1198–1216) rolled out proportional taxes in 1198, requiring the clergy to help fund the Crusades, he tasked the Templars with collecting funds and transporting them safely to the Holy Land. As knights they could take on miliary duties that could physically secure property and wealth. Prior to the military orders, monasteries had traditionally guarded valuables and had been able to lend money. The Templars owned strongholds in the west and in the Crusader States providing a fantastic international and local branch network. The Knights Templars were secure in all senses of the word.

PIONEERS OF BANKING AND FINANCIAL SERVICES

By the 1240s, the Order was providing diverse banking and financial services. In England and France, the Order gave safe storage for sensitive diplomatic documents – some of which could be used as collateral against loans. During the reign of Henry III (1207–1272), the royal treasury was deposited at the Temple, and for part of his reign Henry III even resided there whilst receiving sophisticated financial services. He repaid a substantial loan to the Count of Flanders in annual instalments, drawn from funds deposited at the Templar’s branch in Flanders, making another payment to the Byzantine Emperor by using his account at the Templar branch in Constantinople. Provision was also made for nonroyal merchants to use the ‘New Temple’ in London and Paris for depositing their valuables. The Temple in Paris even sent out statements to important clients several times a year detailing the movements within their accounts. According to Frank Sanello, “Even Muslim rulers enjoyed the services of their nominal enemy and borrowed heavily from these fiscal wizards.”