The Kudzu Review Issue 70

Dear Reader,

Thank you for choosing to look through Issue 70 of The Kudzu Review. The undergraduate artists featured in this magazine, as well as the work of each editor and editorial assistant, have come together in a shared passion for art, literature, and publishing to create this issue.

Since our founding in 1988, The Kudzu Review has published literature and art produced exclusively by undergraduate students. This Spring 2023 semester, we received a record-breaking number of submissions.

To the editors, Thomas Hart, Oliver Brooks, Michelle Benitez, Jasmine Loriz, Tessa Mahurin, Olivia Honan, Lili Verrastro, and all fifty editorial assistants: thank you for your commitment to Kudzu and for the care put into these pages. To our faculty advisor, Bridget Adams: thank you for your sincere support and admiration of undergraduate work. Lastly, thank you to the donors on the last page for making a print issue (and t-shirts) feasible.

In this issue, beginning with the cover “Man O’ War” by Allison Boroff, you’ll find the fresh and imaginative work of creative undergraduates from around the world. It’s uniquely gratifying to collaborate with my peers on publishing undergraduate writers and artists whose work I recognize as part of a collective emerging-artist experience. It isn’t easy finding time to create as an undergraduate student—and certainly not to create art of the caliber we have in this issue—so kudos to our contributors, and thank you for trusting us with your work. I hope the physical becoming of your inspired writing and art is even more potent on the page.

Issue 70 of The Kudzu Review should serve as a reminder of the vibrant and passionate creative community at Florida State and a celebration of undergraduate talent everywhere.

Thank you for picking up a copy.

Maddie Paskow Editor-in-ChiefShavasana Gabrielle Wong

Harana No. 1 Reian Beltran

Effervescence Alana Rose

All I Know About Love... Jessica Anastasia

National Utah: A Series of Haikus Katie kelsey

Man O’ War Allison Boroff

To the Bumblebee... Rachel lechwar

Rain Alana Rose

Musha-Burui Joullian Van Pool

From Wrists to Jugular Jenna Prunty

Sweet Child Of Mine

Zynni Hartman

A Love Letter... Rachel Lechwar

21st at The Tenn Sarah Kate Evans

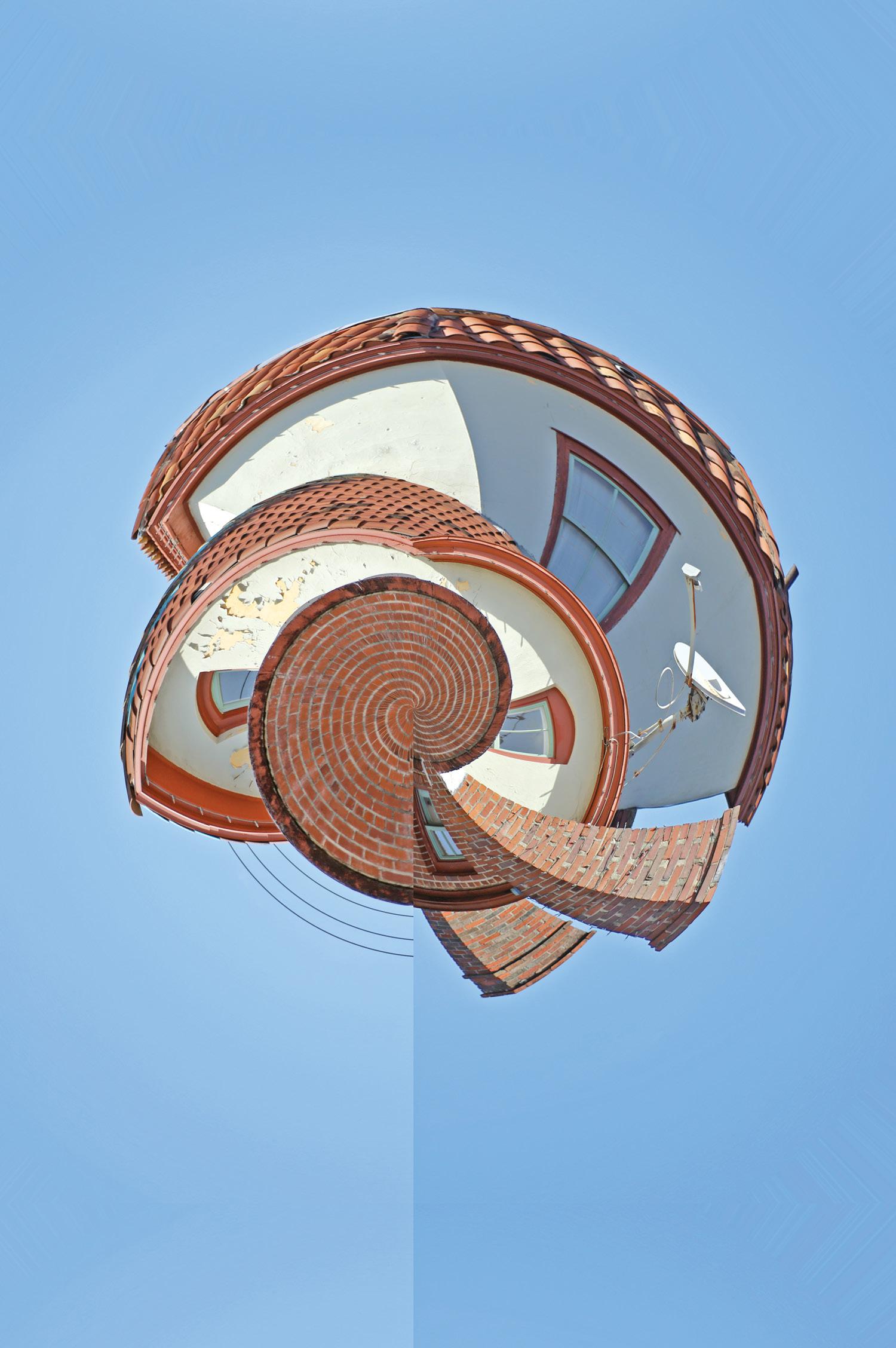

Planet Roof Kathryn Hennessey

Windowsill Chloe Harbin

From a Divorced Dad... Victoria D’Amico

Collage Allison Boroff

Refrain Of The Sacrilege Recluse Samuel McFerron

I Played My Nintendo DS... Jacob I. Taylor

Swim Slinger and The Stone

There Will Come Clear Skies Daniel Fairman

The Poets Always Say Gabrielle Wong

Self Care Cassidy Millhouse

A Taste of the Night Sky Xithlalic Vasquez

Bachata Bajo Las Estrellas Ashley Mendoza

Sixteen Vivian Lipson

By:Gabrielle Wong

By:Gabrielle Wong

I am doing good. I stretch out good like a slinky, one push and I’m tumbling down the stairs over under. Downward dog. Tell me how to gold-medal yoga and I’ll do it—I’m all-American, baby! In the morn ings

I wake up fifteen minutes earlier to thaw my coffee.

In the mornings, Patience wakes up and shovels snow for fifty minutes. She tells me yoga is listening to what your body wants. Freezer-burned fingers, teeth seek adderall on tap. I tie tea bag

strings around coffee filters. Good enough, I am doing good enough. The heron says one fish at a time.

I weave feathers on fishing lines one by one. Algae farm bristles, I’ll chase you with fingers green & slick; is that crooked and alien enough for you? Hot dog lunch break,

pass the relish. Chili sauce soggy bread. I know what’s up. I’m all-American, baby. Tiger moms say that gets you the blue ribbon these days. Spinal fluid spa brain bath, 1 hour, essential oils.

I cut on the dotted line. Valerian voucher. The heron lays on a plastic jumble of wires & down. Shavasana.

By:Reian Beltran

By:Reian Beltran

By:Alana Rose

By:Alana Rose

Digital art using software procreate.

By:Jessica Anastasia

By:Jessica Anastasia

Iwas around thirteen years old when I put my hand over a burning flame. A candle, some version of a pumpkin scent I bought from Bath & Body Works. I had no need to buy my own candle at thirteen. I wasn’t even that into candles yet, and if I was, my mom had plenty I could choose from at home. Despite this, I was at the mall with my friends and a candle was something girls my age would buy— a candle and a handful of underwear from Pink’s 7 for 27 sale. At thirteen, I was pretty similar to girls my age. I liked shopping, I had crushes, I watched teen drama shows like Gossip Girl or Pretty Little Liars, and I was deeply insecure. From the top of my head to the tips of my toes, there was not an inch of my skin that I felt comfortable residing in, let alone something I liked. My hands were included. My hands, like the rest of my body, are very thin, bony even. They appear too big for my arms, like gloves that don’t fit or like a misfit doll put on the wrong assembly line at the factory. My fingernails are short, and despite the slenderness of my fingers, my nail beds are wide with a circular shape to top them off. My ring fingers, in contrast, are squared. They have always been my favorite finger because of this. The squareness compliments the slenderness in a

way that feels more beautiful, more feminine—something like the other girls. Recently, I told my nail tech I need to stop using Pinterest as a way to choose my nail shape, because my hands dont look like the photos. To this she replied, “Well those photos are pretty hands, model hands.” I laughed, knowing she meant no harm and also finding comedy in the widely held conviction that social media creates expectations for our bodies, even down to our goddamn fingers. When I put my hand over the $11 purple and orange flame at thirteen, it wasn’t because of my insecurities; it was because of my curiosity. How bad can it really hurt? What is the worst that could happen? I sat up in my bed, allowing my zebra striped comforter to fall from my chest to my lap, and rolled up the right sleeve of my whimsical giraffe pjs. I reached toward the flame with caution, allowing my open palm to hover about four inches over the round top of the large glass candle…heat. It felt nice, warmth in the center of my hand. It reminded me of the book The Kissing Hand, one of my childhood favorites. A story of a mother racoon who sends her cub to school with her kiss in palm. A reminder that he is never without her love and protection, no matter the

brings me to tears. I inched closer and closer to the flame. Warmer, then hot, hotter, and then burning as my palm met the glass rim. I paused for a moment with my eyes squinted shut before pulling away. I used my unburnt hand to catch and cradle the one I scorched, squeezing it like a tight hug before checking to see if there was serious damage. There wasn’t. How beautiful? That our bodies react out of instinct to keep us from pain, to keep us from burning. How beautiful the way it comforts itself, one hand embracing another before the analytical mind takes over to survey for defacement. Like a mother who embraces her fallen child with a sigh of relief at their wholeness before holding their face to ask, “Where are you hurt?”

My hands loved me before I learned to love myself at thirteen years old—figuring out the pains of the world one flame at a time.

Canyonlands

The tangle of cuts spans elegantly deeper into the abyss.

Bryce Canyon

Beyond the last step the stones dare not move, as their pillars pierce Heaven.

Zion

Narrowing in on bountiful cliffs up above— canyons on canyons.

Capitol Reef

Where life dare not grow, rocks and their sandy orchard bear glorious fruit.

Starry nights softly blanket the stone and sand with astral defiance.

By:Rachel Lechwar

By:Rachel Lechwar

I’m sorry for never rolling down my window to let you in, though I drove oh so carefully, ten miles below the speed limit in the left hand lane. The green traffic lights smeared along the front of my car like blurry afterthoughts, and I couldn’t have stopped, even if I wanted to. But I need you to know that I would have taken both hands off the wheel to cup them around your shivering body, blanket you into me like an old friend. I’ve been running from you for as long as I’ve known how to run, shielding myself from your crescendo, but here, your little legs can’t quite grip the surface of my car, gasoline breathing beast that it is.

You are a water droplet of a thing. A crooked petal body. A crinkled wing. If I could expand into the shell of my car, I’d make you a part of me, but I am tender skin that can sting and bleed. If I could have hardened my hands to shelter you, I would have let you rest in the nook of my cup-holder bed and you’d never have to know what it feels like to become the rain, sliding down my mirror and into the static yellow lines of our street.

Daisho, affixed him. It is with poise and temper That he keeps his feet. The top of his head is shaved, the rest is kept long which is routinely held up. Tonight, it is down. But, tomorrow, chonmage. It’s wrong for him to visit A woman of the red light, It is improper. But to escape the humdrum Of the floating world, In town of paper lanterns, He wears kimono And a straw sedge hat, faceless. She smiles, play woman. An exchange is made, hard, soft. Urgency. Embrace. Wilting.

By:Jenna Prunty

By:Jenna Prunty

My neck hangs crooked, crinkled on the left hand side scarred wrinkles festering as if it were an infection blistering, a brand of brother rope caressing me on my jawline coarse and strong, his only weakness in knife play fraying the ends of his fragility just as he did to me from wrists to jugular, I hold him among my palms stroking his side with my thumbs I want to feel him kiss my neck again a desperate grind against me the burn of his touch, he slides over me, a snake, seductive offering an escape from reality in a fiery intimacy, confident and dangerous and when he tightens over my scars, my breath hitches, I close my eyes and arc into his touch.

When she saw the fleshy toe sticking through the shrubbery, her first instinct was to double-check her pouch. She thought one of her own had escaped and had gone to hide in the tall grasses to give her a heart attack. Such were the antics of her mischievous litter. She had awoken from her daytime slumber to the sound of crunching leaves and soft whines. After seeing that everyone was safely tucked away, she lay on the edge of their burrow and shimmied out slowly to catch the potential threat off guard. She thought about waiting it out; maybe this creature would move on. The closer she crept, the more unnerved she felt. Something deep in her gut was sending warning signals, but still, the opossum approached the glen.

The toe began to wiggle. Unsure if this was a threat, she braced herself for an attack and rushed into the grasses, hissing and baring her pointed teeth. Upon seeing what she was about to attack, she stopped short in utter confusion. The creature before her let out a screech and a long wail that sent shards of ice through the opossum’s bloodstream.

It was a preposterous thing to see so deep in the woods. It was sitting

on its rear, legs splayed in front. Its arms, covered in rolls, were swinging as it thrust its balled fists into its eyes. Its chubby face was slick with tears and snot, mouth still opened in a frightened cry. It had some material on its legs but the rest of its body was smooth, hairless, albeit covered in mud and scratches. It was a baby. A human baby. The hair on the back of the opossum’s neck raised. If there was a baby around, that meant its human adults were somewhere close. She darted back towards the burrow to hide and waited for the humans to come back. It was unnatural to stay awake when the sun was out, but for some reason the opossum was determined to wait for their return. The baby reminded her of her own babies, how they were small and pink and vulnerable. Someone would be back for it, and she would make sure, if only to calm her own nerves. When the sun’s rays stretched into the trees, the opossum left the den again to survey the area. It would be night soon, and her babies would wake for something to eat. She stalked closer to where the baby had been before and saw no sign.

her own babies, how they were small and pink and vulnerable. Someone would be back for it, and she would make sure, if only to calm her own nerves. When the sun’s rays stretched into the trees, the opossum left the den again to survey the area. It would be night soon, and her babies would wake for something to eat. She stalked closer to where the baby had been before and saw no sign. Contented, she pushed her thoughts of the baby to the back of her mind and began searching for food.

A twig snapped, echoing in the evening twilight that bathed the forest in sinister shadows. The opossum scurried toward the sound, trying to keep quiet. Peering through the grass, her senses became attuned to the hawk that stood staring at a small lump on the ground. The hawk cawed and moved to strike the creature. The opossum saw the baby on the ground, deep in sleep, unaware of its imminent fatality.

There was no thought, no hesitation—the opossum lunged toward the hawk, screeching and tearing with her claws, putting herself in front of the child. The sounds of the quarrel caused the babe to wake, and it resumed its terrified howls. At the sound of this alarm, the hawk faltered, and the opossum swiped at its eye, slicing it deep enough that the hawk let out a shrill cry and flew away.

The opossum’s torso rumbled; the excitement had woken her babies. She turned back to the crying human and began to rub her head on its legs and tummy, slowly and softly, licking a few of its scratches. The baby’s piercing yells soothed into sniffles and coos.

In this time, the woods had transformed again. The

sun was gone and the moon shone brightly above, and the orchestra of the night had begun: the chirping of cicadas, buzzing of crickets, wind rattling through the hollows of dead trees, and the cacophony of growls and howls of nightcrawlers rising from their rests. As she sat beside the alien child and continued to play with it, she wondered what she was doing. A level of trust had been formed between this human baby and wild animal, for reasons she could not imagine. The opossum was forced to think of their next steps. She had waited all day for the humans to return, but hardly a soul had come near the area since she had been stirred awake. It seemed as though it was abandoned. She couldn’t leave a baby defenseless in the woods.

Her babies were hungry. They poked and prodded within her pouch, eager to explore. She would need to move on soon; it wasn’t plausible for her to take the human as her own. She looked at the baby again—it was petting her fur and smiling, its chubby cheeks spread wide. She knew the animals in the forest would see this baby as a game, taking for granted its innocence, its friendliness. They would tease it before consuming it, enjoying the juiciness of its infant fat. She knew this, so she rose into a crouch and, faster than the baby could catch on, closed her jaw around its neck, sunk in her teeth, and tore away. The baby didn’t cry. It let out a few hiccups, then fell silent on the crumpled leaves.

The opossum turned away and began its trek to find a new burrow and something for her babies to eat.

From a stranger, sitting a table away,

I hope you find a home, in a town somewhere between the Mississippi River and East Coast but north of the Panhandle, somewhere with honey-suckle shaded leaves and moss-bundled turtleneck trees that watch as she slips her hand into your coat pocket.

It should be tucked in the suburbs of a place that sounds sturdy, New Kent, Williamsburg, Windsor, somewhere that has Southern charm but also Pride flags draped beside stained glass church windows. A city where she can live like she belongs in Beverly Hills, in her burnt orange fur coat that still bleeds LA, but spend her days as a sous-chef at a local start-up and her nights curled in bed beside you.

I hope you continue to teach but earn enough to buy your mom that condo in Coral Springs, your mom who has spent five years asking

“Are you sure she’s the one?” like you asked her about your father, who can’t leave her anymore but still separates their groceries down the middle of the cart.

“Find someone who wants to hold you close.”

I hope that when you call her superficial and she mimics the twang in your voice, you don’t mean it too much but that you are honest when you need to be, and I hope all your sorries don’t pile up like laundry in the corner of your room.

I hope you never have to have another panic attack in the backseat of a car, even if you have to blast Beyonce and smoke weed until your heart rate winds down. I wish you no more traffic jams, no more heartbreaks, no more conversations with your father where your name dissolves like sugar on his tongue, no more nights alone in your apartment where your finger roams the wrinkles in your sheets.

I hope that you draw near enough to see your love in every shade of light,

apricot, amber, honey-dipped gold, that when you hold her, your hands trace the ridges of her shoulder blades and her fingers fold over yours like cross-hatched lines.

I hope she holds you, so close that her skin meets yours to whisper “Yes, yes, I will stay.”

By:Sarah Kate Evans

12” x 16”, oil and glitter on panel

By:Sarah Kate Evans

12” x 16”, oil and glitter on panel

By:Kathryn Hennessy

By:Kathryn Hennessy

Digital photography, edited with Photoshop

Blood orange trees waver in euphony rhythm, But the nectar on my tastebuds is of black and white.

Reveling in what is seemingly obsolete,

She plucks one of the sweet fruits from a morose seedling And runs up to her father with pompous vernacular over her triumph.

The following days the same child appeared in this garden, Each day she plucks another fruit and lays it upon her windowsill. The rotting peels turn brown as she grows older. The collection expands into a stale cardboard box she keeps secretly underneath her bed, In a room now full of blood pressure monitors and a glucometer, And wallows away listening to the never-ending ringing, As she becomes a witness to a distant memory of herself. A damp smell of decaying citrus circulates from underneath my bed As I stare outside, leaning upon my windowsill, Only hoping that the roots of those trees are still lingering somewhere.

to chop a lot of garlic—suddenly every other task is too dangerous when you want to help him in the kitchen. Expect dollar store green apple shampoo and a conditioner that doesn’t match. Expect Red Sox games, Pawn Stars, and Food Network. Expect to watch The Parent Trap. And then watch it again. And again. Expect to see him tear up for the first time on your twentieth rewatch and be prepared to turn your head the other way. Expect forgetfulness

you’ll probably be missing part of your school uniform when you get to your mom’s house on Sunday night. Then, expect him to forget to pick you up from choir practice on Monday. Expect bike rides and trips to the grocery store; these are the only activities he can offer on weekends after spending what was left of his money on cheap booze and cigarettes. Expect jazz music and Steely Dan. Expect him to give in when you find that puppy on the side of the road. Expect bruises and bloody knees and back rubs. Expect cups of wine instead of coffee early in the morning. Your drives will be hell, but he’ll get you there in one piece. Expect his comfort even when you’re weeping that you hate him. Expect to go gift shopping at garage sales, or, if it’s a good year, expect $20 each for you and your siblings (expect him to say he picked it out himself and think it’s funny every time). Expect to grow out of his jokes, the room in his house, and the mindset that you’re okay with the way he talks to you. Expect him to move out—him, not you—and take the dog and the old white truck that you hate so much too. Expect him to go back north, where you know he’s happiest, and start growing a garden. Expect to only talk to him three times a year, on both of your birthdays and on Father’s Day. Expect the calls to be at least an hour long. Expect him to tell you all about the squash and the tomatoes, and how the dog is good but he’s going a little blind. Expect him to ask you to say hi to your mom for him. But most of all, expect for the both of you to be okay when the garden freezes over, and his hearing is so bad he can’t listen to music anymore—when his hands have gotten too shaky to chop garlic on his own, and the dog dies, and the calls stop.

By:Allison Boroff Oil Paint

By:Allison Boroff Oil Paint

i.

Can you shadowbox the warm revitalization in brown powder stirred to dark liquid in faltering ever to when panting hallucinations take cover and remind you of your own roadmap of of your old friends’ tongues or a regular bowel movement in recurrent cozy hell you lie forever craving the smack of your palm on rusted veins tighten your belt and dip your head in the sink of aching fever.

ii.

I disregard your issue when you come out of my even though I said “I don’t want that poison in my house.” because I can’t stay mad at you. I’m not angry when I drop you at the emergency room because you know I know I don’t sweat at your thirty days. I don’t speak as you rattle through withdrawal for the fifth time on my couch. I don’t blink when I see you wearing a warning you. I don’t know

iii.

Your eyes, damp, red, “Aren’t you supposed to “Aren’t you supposed to be here?” when I pull states and cities by the collar. “Aren’t you supposed to be here?” as I reshape your memories. “Aren’t you supposed to be here?” as brightened soiled shovels become the last shared substance to steal my dear friend.

Now there are none in the field where the men used to tend to our ripe crops. Boot soles left marks in the dirt there. I’ve been told they’re so old, Now there are none in the field where our man used to tend to his ripe crops. Butt of a rifle has damped down the old carpet inside, Doorside; the front door where he used to ease in and make himself: milk, bread. Now there’s no rifle there. Where he. He had once set it down. Later he’d lift it up. Put it up, mark still left. Gun cases hold guns. Four-wheeler tracks in the dirt there. I’ve been told that’s when C Knew there’d be none in the field where he once went to crops by himself now. Grandpa inside had this brute force and an iron man’s will. Truly the single thing able to kill him was loss of his true love.

Dear one, I wish I could. C.I., how could I not have met Grandma, the woman you felt so much towards that you left for her, C.I.? Wish I was able to—here, now—understand why you left.

He rises early, usually at dawn. Decades of discipline and old age carved a Spartan routine. After a hot coffee and a myriad of pills and vitamins, he walks under tree limb canopied streets and rising mist—the grass still fresh from the morning dew before the cruel midday sun.

It is summer in Florida, Sunday. I wake at noon, groggy and tired. My father is not home yet. I drink a lazy cup of tea and watch clouds amass in the distance. In the small nook of my room, time flies as I read Pico Iyer’s recollections of lonely places in the world. I check the time. It is almost three. A little worried, I text him asking where he is.

“I’m in the hospital. Not sure when I’ll be back.”

I call him right away. He tells me he drove himself to the hospital in the morning because he felt off.

“Why didn’t you ask me to drive you if you were feeling bad?”

“I didn’t want to bother you.”

His hospital room is quiet and empty, his eyes transfixed on the round clock hung on the wall across from him. Eternal minutes turn to hours of anxious waiting to find out what is going on. Dizziness turns to frustration, but we cannot get too upset. In desperate rooms patients are dying, barely clinging to life. Whose rich story has been so unceremoniously extinguished?

He has been here half a day, laying in bed, waiting.

“I’m going to walk out of here. I feel fine now.”

“Absolutely not. We’re waiting.” When he comes back from the

By:Daniel Fairman

ultrasound something feels off. He needs another test. A heart catheter exam, about forty-five minutes. Often people think about taking care of someone who is sick and, rightfully so, all the attention is given to them. Who did I have to turn to? Who would listen in a house filled with grief? Generations of manhood taught us to suffer in silence. I wander the halls of the hospital in a trance listening to the detached beeping of monitors from behind closed doors and watching nurses fill out paperwork. An old woman stands by a window, her face etched with grave lines. Sneakers screech on the tile patterned floor. Tired janitors push their carts down the long, sad halls, white walls blaring loneliness.

A nurse had been looking for me. He tells me my father is on the seventh floor. I walk in. The doctor introduces himself and explains what must happen.

Three major arteries are blocked. Open heart surgery or we wait until the next emergency which will likely be fatal. The triple bypass is scheduled for six a.m. tomorrow.

For the first time in my life, my dad is afraid. His eyes struggle to keep his usual composed look, but the welling of tears, the shaking of his hands, betray him. I want to stay the night. He says no, I’ve done enough already. There’s nothing I can do anyways. Go and get some rest. I know he says this because his heart is fragile. Though he is quiet and stoic, behind this is a lifetime of broken hearts, of cold parents who never uttered the words all children deserve, of girlfriends who left him, of a wife who abandoned him, and of best friends dead and gone. At the end of sixty-seven years, the

battered soul of a sensitive man learned to hide like a lost child in the dark. All that is left is a father and son who love each other quietly but deeply. Tomorrow, his heart will truly be bare, open to the world as it never has been before. He is strong. He will be fine. But what if he isn’t? It is just the two of us now. We look out the window. The sky is gray and rain falls on the lake below, thousands of droplets. Hard ripples spatter across the dark blue surface. The heavy rain streaks the window, fast-moving on the clear glass. In the sacred silence of sorrow, the storm passes. Dappled sunlight streaks into the room. Clouds drift away and rays of golden light illuminate the lake. My father smiles. For a moment, he is lost— gone in some beautiful dream. He is not the weary old man anymore but a shining youth, radiant and pure. I squeeze his hand and, in a whisper, he says, “There will always come clear skies.

weeping weeping weeping / good things come in threes / pockmarked / bitter / stinging / the softness / each and every ghost / each and every God / each and every genesis / four walls and a mother / fatherhood / girlhood / and the stars have all died / from the same dust we are made from / i have questions / i have answers / i have lied / tell me “stop” when you hear a truth / tell me “go” when it is a truth that’s been stolen / headlights / all the flavors of hours after midnight / an ache / a void / the well in my chest / the palette of feelings together on the page / an empty canvas / a spinning wheel / the clay / the contour / all the flavors of love / all the flavors of love after / death / hurt / pinprick of pain / the vivid / vocal / validity / definitions / plump lip petals / give me a moment before the / break / when the well runs brown water you will drink / when the well runs clear you will cry / the unfiltering / the treatment / rainstorms / autumnal grieving / the quiet / a first snowfall / baby breath / murmuration / a sonnet / a song / a soliloquy on the side of the road / tell me “stop” when you hear a lie / all this to take the moments / the magic / all this to show / you mean it.

By:Gabrielle Wong

One day, I woke up able to taste colors. I remember it clearly, my lips were stained a vibrant red from the agua de jamaica that I had guzzled down before promptly dozing off on the colorful hammock that hung from a tree in the front yard. A bee had been buzzing around my lips but flew off once I opened my eyes; any courage it had been working up to land on me had left the poor being once I opened my eyes.

As the buzzing grew distant, I sat up, the rocking, sinking feeling of the hammock only adding to the initial disorientation as my small body got lost amongst the quicksand-esque of the remaining textiles of the hammock I didn’t fill. My cheek stung with the outline left behind by the turquoise and crimson cords interwoven into a unique pattern. The faintest scents of anise, quesillo, and chapulines still clung to the cords after the jammed journey they had all shared on their way from Mexico.

I rubbed my eye with a textured hand, feeling the indents left from the hammock against my eyelid. The splotches of sunlight that the big tree allowed past only added to the soft throbbing starting to

A yawn rippled past my lips, and the lulling sensation the hammock provided only encouraged me to sleep a bit more. I almost did before my mom called out to me once again from the shaded porch where she stood on the rickety wooden step right below the entrance of our trailer. She wore a pair of faded jeans and a nice salmon-colored blouse. Her hair was slicked back with

gel to make her ponytail look proper. She held up two shirts, and I squinted, barely able to tell that they were shirts as the sudden flash from the sun made the golf ball textured trailer door and off-white, thin aluminum coating of the trailer nearly blinding to look at. Thankfully, a cloud floated past the blinding sun, making it bearable to see again.

Before I could call out to her, asking her what she had called my name for, she held up two shirts — a forest green shirt and a gold shirt, the designs long faded — before asking which I wanted to wear to my kindergarten orientation.

“Green.”

The moment the word left my sweet-stained lips, a fresh taste washed over my tongue. The crisp cool, mild savor of cucumber singed my tastebuds; the sweetness of the hibiscus iced tea long gone.

I swung a leg over the hammock, nearly falling as I scrambled to my feet. My head drummed as I made my way to my mom, and my tongue tingled.

“Mami-”

I paused in confusion as another batch of tastes washed over my tongue. This time it was the freshly baked warmth of thin sesame bread that rolled over my tongue. What I had thought was just an odd occurrence from a color turned out to be much more.

I ran to my mom, hitting my shin against one of the steps as I grabbed her leg, confused as to why all these tastes danced across my tongue every time I spoke.

“Mami! Mami! I taste- I taste words!”

Sesame bread. Sesame bread. Basil. Green water-based jello.

She told me to stop being ridiculous, but after I kept insisting, she promised that she’d schedule an appointment with the pediatrician. I agreed and kept silent about the whole ordeal, impatiently waiting for my father to arrive to take us to school.

Of course, I had a few test words, curious as to what they would entail.

My favorite number — eleven— tasted like lemon-lime soda.

My mother’s name tasted like pink flower petals. My father’s name tasted like peanuts.

And my sister’s name, unfortunately, tasted like mamey sapote when it should have tasted like a bitter banana if anything.

I said my name — what I was called at home anyways — and was greeted by the sweet, bitter taste of tamarind. It was good enough. Totally better than the creamy, sweet goodness of mamey sapote.

I don’t remember much after that, only recalling hiding behind my father’s leg as he did all the talking to my teacher. My hands clutched his pants in my fists, shyly peeking out at the older woman as she asked what my name was, and my father answered.

It was different than the one that I was called at home.

She repeated a butchered version of it and once again my father repeated himself. Saying the name so many times that I could never forget. He didn’t stop until he deemed my teacher’s attempt good enough.

This was the first and only time anyone ever fought for my name.

On the way home, in the back of the white truck, as norteño’s rumbled throughout the car, I said my name.

I was greeted by an indescribable taste, no words could possibly encapture all the flavors that my name held under wraps. I wasn’t even sure if I had ever eaten anything that was a fragment as delicious as the tastes that my name induced.

For that day, I loved my name.

That love got squashed quicker than a spider (which tastes like sawdust.)

The first day of school already made me nervous enough -- I was even longing for my sister to stay by my side, which she didn’t. She just dropped me off at my class before walking off and leaving me to fend for myself.

I kept silent, still cautious about my words and their tastes. The anxiety of the new environment and unfamiliar faces only added to my silence. However, it didn’t take long before I had to speak. The teacher was calling everyone’s names, and name after name passed as I waited for mine. Soon, there were just three kids whose names hadn’t been called.

There was a pause, a silence that hung in the air like humidity on a summer’s day after a thunderstorm.

Then, she called out my last name. She apologized as she asked me to say my name, and I did, saying it as loudly as the tight sensation in my throat allowed. The indescribable taste of my name helped ease me as I tried not to think about how my name was the only one she had to do this to. I had just been expecting to say I was there and then move on.

I had been dreading those few seconds when everyone would turn and look at me, but now those few seconds were dragging into eternity as she repeated what was supposed to be my name.

She asked if she had said it right, and I said no, and she asked me to repeat myself.

I did, but the same thing happened, time and time again.

My sweet name rolled off my tongue but got messed up on hers.

As eternity stretched on, my face grew hotter, my hands got sweatier, and tears beaded in the corners of my eyes, as I wished for my dad to come back; for him to teach her until she got it right because I couldn’t do as good of a job. I felt more and more like dying as I could feel everyone staring at me as my teacher seemed to purposefully say my name wrong

and then had the gall to ask if she had gotten it right.

It was too much for me, and I resigned, agreeing that her last attempt had been correct, and repeated it back. It sounded wrong on my tongue, instead of the taste I loved, a bitter, hot, moist sensation engulfed my tongue.

I recoiled but was glad that it was over and that this isolated incident wouldn’t make me say that name again, so I would never have to taste it ever again.

However, my endeavors were only beginning. Introduction after introduction, person after person, and year after year, the same thing happened. At first, I tried. I would say my name, but a shy child can only take so many public embarrassments before they just agree, just to move on.

I’ve gone by many names, but never by my real one.

Even my family calls me by the nickname I was seemingly assigned since birth.

As time went on, and crying in the bathroom after attendance became more and more shameful, I grew to hate the name I had lovingly repeated over and over the day I learned it. I hated saying it. I hated saying the variants. I hated spelling it. I hated even seeing it among the other names since it looked like someone had smashed a keyboard against a

I remember the first time that I screamed at my parents, asking them why they would damn me with a horrible name. Asking them why they gave me such a complicated name when they gave my sister a simple name and a middle name. Asking why I got a spelling error for a name and no middle name. They tried to reason with me,

A shy child who broke into tears and whose voice became mute when brought the front of the class for any reason, and

that same sensation happened when it came time for attendance because of my name.

I cried, asking them why they couldn’t have named me something simple like Maria. The name tasted like chocolate. I would love to say that name over and over again, although the simplicity of it wouldn’t require it.

If they had wanted a name not as widely used then there was Cecilia - which tasted like watermelon. I love watermelon. Who didn’t?

And if they were so hellbent on making my name start with one of the least used letters of the alphabet, there was Ysabella which tasted like lavender lemonade. A touch of commonality with a flare of uniqueness.

And I grew to hate my father, the man who had damned me with the name.

Funny how the man who was once my savior all those years ago became the villain.

It was like that for my entire adolescence, a screaming, crying match every time my name was brought up. It wasn’t until I was older, becoming an adult in the eyes of the law, that I finally asked a question I had always been asked by others.

“Why did you name me my name?”

I remember that my father was sitting in his recliner, eating chocolate - which funnily enough, tastes like apples - and my mother was at the kitchen island, kneading bread.

I saw my mother glance at my father who took a few seconds to chew the chocolate before he spoke.

“Whenever I was a child, I heard the story of a goddess who created the stars in the night sky that I looked up to every night. I fell in love with the name and I wanted to name you after her. I wanted the spelling to be unique, just like a star in the night sky. After the goddess of the stars and moon, Citlālicue.”

Citlālicue tastes like agua de jamaica.

That day I broke down into tears, unable to stop crying as all my years of hating my name

suddenly slapped me in the face. All the variations I had greenlit when deep down in my heart I knew it was wrong made me feel as though I was drowning, suffocating on all those inaccuracies I encouraged because I couldn’t see the beauty in my name although I could taste it.

My name may not be a simple one like the ones I had longed for all my life, but it’s mine alone. Ever since that day, I’ve tried my best to go by my real name, not some cheap alternative that never tasted right. Some days I relent and give an alternative name, habits are hard to grow out of, especially ones that I’ve kept up for about fifteen years, but the bitter taste that dances along my tongue serve as a reminder.

One day I will be able to go by my name in this country. After all, if they can say charcuterie, they can say my name too.

der, buttons, fruit nets, fabric, and yarn).

soft pastel, collage, artsticks, graphite pow -

By:Ashley Mendoza

By:Ashley Mendoza

Mixed media (including acrylic, oil pastel,

Iwas dressed as a slutty nun. Staring at myself in the mirror, I felt a swagger, an insolence that almost surprised me.

It was as if my own eyes dared me to scold myself. To keep my head down. But I didn’t— I met my gaze in a way I had rarely done before. And I looked good. I felt a want for things. Things I had never let myself want before. I wanted jewelry and makeup. I wanted to be touched. I wanted to touch. I wanted to press my face into someone’s neck and bring them home with me. I wasn’t afraid. I wanted to do things that my mother would disapprove of. I wanted to do things that would make people angry because I didn’t feel afraid.

I stepped out of the house possessed. What I was doing was one of the most scandalous, boldest things anyone could do. At first, it was very hard for me to step out of the house. But then it got easier. I got to the site of the party—a big yellow house with a wrap-around porch—about an hour in. Stragglers were standing outside and smoking, and as I walked past them, I felt them notice me. They were not as dressed up as me:a few costume pieces, some cat ears and masks. I knew I stuck out. Maybe these smokers were so laid back, so infinitely cool and casual that they didn’t even notice what they were wearing, didn’t obsess over it like me.

As I stepped inside, I could feel people’s eyes on me. I felt afraid at first, then something else. Halloween was about

monsters and villains, and if that’s what people saw, then that’s what I was. A villain. But tonight I felt the strength to be one.

I spied on Lucy. For weeks at lunch, she had looked at me from far away, across the lunchroom. And I saw something else where I expected to see the contempt I had grown to expect. A smile. One that was not simply friendly, but concealed something else. I could almost call it greed. She saw potential in me. Potential to sit with her and be a holder of the things that popular people have: responsibility, pride, and judgment. Could I judge? Could I keep the gates?

When she came over to my table and informed me about her party, I smiled shyly and said okay. But the thought made me restless, and excited. Things drifted through my mind and I knew I would lie to my mother about this party. The first lie that held any consequence.

“Wow!” She shouted over the noise, shaking her head and laughing. “Fuck, are you a nun? You’re crazy, I love it. Come, I’ll get you a drink.”

I smiled and kept my eyes on her. Lucy didn’t make me leave. She seemed to like my costume. She seemed to think I was bold. Maybe this is who I could be here. A wild girl. An outrageous girl. Someone who said things that no one else could. That was so far from what I thought of myself that it seemed like a lie. But I liked it. I could lie.

At my last school, I kept my head down and said very little to anyone. But now, here in a catholic school, I felt different. Maybe a

more restrictive atmosphere made me braver. I was no longer the weird girl with the Jesus-freak parents. I was just a girl from public school. I was anyone. I could be anyone.

Lucy handed me a pink-colored drink in a red solo cup, and I drank it silently because I knew I wouldn’t know what to say. The bitter taste shocked me as it slid down my throat but I kept my face neutral. I didn’t want to break the illusion. I just smiled, pretending I could drink. I did drink. I did now.

People stood around me. They were girls I knew from a distance. Beautiful girls who sat with Lucy and talked loudly about things I didn’t fully understand. Things I wanted to know about. Now they were talking about their costumes.

“I’m Marilyn Monroe! I don’t know how you didn’t get that—she only has, like, one look.”

“You definitely have the tits for Marilyn”

There was a howl of laughter and I cautiously joined in.

“Oh my God, Elinor, I fucking love your costume. Literally, so many people are talking about it. If my parents saw me in that, I swear to God.”

“Wait,” said a voice I didn’t recognize. “Elinor, what are you?”

It came out of my lips before I could think to stop myself.

“I’m Sister Thompson.” Their laughter was so loud I couldn’t go back on what I had just said. Sister Thompson was an elderly nun at our school who was quick to give out detentions and check skirt lengths. She was very disliked. To drive the comment home, I grabbed my boob and let out a high-pitched moan. That got a second roar of laughter. My face went red and in spite of myself, I laughed along. I poured myself another drink. Maybe if I was drunk enough, I could let myself be funny. Let more outrageous comments fly. I felt vulgar. I think vulgarity suited me.

I had gotten drunk a few times with my brother and older cousins, giggling in upstairs rooms at family events. I loved the way I felt warm, the way it made my head spin.

The way I didn’t feel like myself. The shame and embarrassment of everything I knew to be me fell away, and I could just talk. I decided that

people would like me more when I was drunk. When I didn’t feel so hung up.

After a few more drinks I joined in on the shouted conversation. I yelled with the rest of them, and I didn’t care that I didn’t know what secular TV shows or teen celebrities they were talking about. No one seemed to notice. And for the first time when talking to people my age, I didn’t wince when I spoke. I didn’t brace for the “shut ups” or the eye-rolls I had come to expect. And no one did roll their eyes. They seemed to enjoy what I was saying. They seemed to really like me.

I even did something I had been thoroughly scared of since grade school: I sat with boys. Though this was an all-girls school, people brought their boyfriends and “guy friends” with them, and these boys huddled around each other awkwardly on a couch in the back of the room.

I had avoided boys ever since seventh grade when a pack of boys in my class started following me, whispering that I had Elinoritis, a disease they said spread by touching my skin. Boys would pretend to want to kiss me then run away snickering. They would tell their friends that they heard me moaning in the girls’ bathroom, screaming the name of whichever boy was telling the

story that time. Anything I did that looked like desire, that looked like sexuality, was cruelly twisted into a weapon to be held at my throat. I feared boys the way one feared nuclear waste. To be around them is to have your body turned against you, for you to become sick in a way that you can’t always see but is always there, causing destruction. Their joke had lasted so long that a few people even pretended to moan when I stepped on stage for my middle school graduation.

But tonight I sat on that ripped-up couch and let my legs rub against theirs. I laughed at their jokes and ignored the harsh gaze of my grandma looking down at me from heaven. You’re selling yourself for these boys, they don’t see you as anything other than meat. Nothing more than a thing to conquer, a thing to stare and laugh at, a thing to watch and follow home, howling obscenities all the way. I looked away from her as one of them put his hand on my thigh. James was dressed as a killer from some horror movie. In the dark red light of the party, he almost looked beautiful. His face was cast in shadow, obscuring his features. It snuck up on me, how much he wanted me. I didn’t realize it until his hand moved up my thigh and I looked into his eyes and saw something unbearable. Something hungry. I tried

to match his energy, but anything I did was a poor imitation.

I had barely had my first kiss, a quick brush of lips at a church retreat that ended with us sitting at separate ends of the cabin, smiling while looking down at the floor.

I thought given my sixteen years, I ought to do more, know more about sex. If I had an opportunity, I ought not to pass it up. And James was handsome, sort of. He was acceptable. He had been invited to this party where everyone seemed more beautiful than most. And he wanted me. He really wanted me with no double meanings. No irony. He wanted me. But still, I had trouble meeting his eye.

His breath was hot on my neck. “Do you…” He slurred. “I think you’re really pretty. Do you wanna go to the bedroom?”

I considered his proposition. For so long this was all I wanted—to be sexy, to have sex—but I couldn’t make myself look at him. His face had too many pores, tiny hairs, and beads of sweat that I hadn’t noticed before.

“Yes,” I whispered back softly. Across the room, Lucy was staring me down with a little smile on her face. She winked at me. This impressed her. I immensely liked the idea that I impressed her. James got up and reached for my hand to follow him. His hand was warm and heavy in mine; I held on to it so lightly that my hand was really just resting there on top of his. Others at the party noticed us leaving together and chuckled. Each step felt like a step I could not go back on. I wanted to walk slower, drag my feet like a child. But I was not a child anymore, and I had worked so

hard to make myself see that. I wanted to go back, but I sensed so much in Lucy’s wink, in the feel of Jame’s hands on my thigh. This was how I could make people respect me. Keep me around.

We entered a dark room and didn’t turn on the light. I was glad. I didn’t want James to look at me. I saw his silhouette on the bed. He didn’t look like a boy; he looked like a man. I didn’t know his shape, and I didn’t know him. He seemed unpredictable, uncontrollable.

“I like your costume,” James said in a raspy voice.

I liked it, too, portraying the forbidden. I liked leaning into vulgarity and doing things that would make my mother shiver. I liked the power and freedom I had in doing things I had been taught not to do. I liked the duality of the slutty nun, the idea that someone can wield the power of sex over themselves and those around them, and still carry the symbols of God. They wouldn’t be smitten on the spot or burst into flames. Nothing is as it was taught.

James did not understand this. He just thought I looked hot in my red tights.

“Thank you,” I said to him, not knowing what else to offer. The room seemed too small, too hot. I realized how much I was sweating. “I’m gonna go to the bathroom.” I needed to freshen up. I needed to think. Alone.

I walked to a bathroom down the hall. When I switched on the lights, I saw myself in the mirror.

My eyeshadow was smudged from rubbing my eyes. I didn’t look irresistible like I had at the beginning of the night. That was an embarrassing delusion. My eyes looked too far apart, my nose too heavy. Nothing seemed to be in harmony the way other people’s faces tended to be. The way Lucy’s face was. I looked like a kid who sloppily applied makeup for the first time. I looked like myself again, the one that didn’t get invited to parties or make boys laugh, the one that nobody thought was beautiful.

I put my face in the sink and let the water run over my head. I wanted to wash away all the makeup, all the evidence that I had tried to be anyone other than who I really was. I lifted my head back up and turned toward the door to look for a towel. I gasped: In the doorway stood a girl looking to the side.

She was one of the lucky girls whose features didn’t seem like they were at war on her face. For a split second, I worried about what she thought of me, if she would judge me for my bathroom melodrama. Then we both took a step forward, and I realized that she was just my reflection.

There was another mirror on the door that reflected the mirror above the sink, catching me at a strange angle. I laughed. I looked beautiful in a way I hadn’t noticed before. The curve of my eyes, the way my cheeks rose when I smiled—

I looked like myself. I had always hated the way I looked from the side, how my chin looked weak and my nose stuck out. But as I looked at myself in this mirror, I appreciated my profile. I looked striking. I looked like my mother.

I made my decision quickly.

Instead of walking back to the room, I walked through the party crowd and out the back door. I was careful to avoid eye contact, to not let anyone see me. I needed to be gone. I didn’t want to see another person that night.

I walked down the streets quickly, flying home and glancing behind me every few minutes. It was almost 1 AM but if I bumped into anyone, I knew it would be way too embarrassing to handle. It was cold, but I left my coat at the party and I didn’t want to go back.

I made it home thirty minutes later without seeing anyone. I closed the door behind me softly, walking past my mother’s room and imagining her snoring behind the wall. I wanted to climb into bed with her but I made myself walk forward. I rushed up to my room, covered in glitter and shivering. I peeled off my costume and shoved it deep into my closet. I would wear it again. I climbed into bed and lay on my Mickey Mouse sheets in the remnants of my party makeup.

Editor In Chief: Madeline Paskow

Managing Editor: Thomas Hart

Faculty Advisor: Bridget Adams

Fiction

Editor:Michelle Benitez

Taylor Tieder

Sarah Lerner

Pearl Ray

Madison Hollander

Anna Zak

Daniel Fairman

Havilah Sciabbarrasi

Tre Hands

Rhubi Henderson

Sebastian Cebvallos

Editor: Jasmine Loriz

Jake Aboulhson

Michelle Chadwell

Peyton Addison

Rachel Lechwar

Daniel Ardilla

Andrea Lopez

Jillian Kaplan

Grace Allen

Hannah Raisner

Riley Atzert

Rory Donohue

Editor: Oliver Brooks

Editor: Olivia Honan

Jamie Soto

Olivia Hrinko

Laura Giron

Alexandra McGivney

Roy and Lois Paskow

Elisabeth Hope Harner

Matthew Roque-Paskow

Jacqueline Dubose

Stephen Brooks

Skip Horack

Mark Spirtis

Barry and Jody Gold

Edward Long

Diane Roberts

David Kirby

Read past issues on our website, www.kudzureviewfsu.com

Are you interested in submitting to our Fall issue?

Check back at www.kudzureviewfsu.com/submissions in August 2023 for deadlines and information on how to submit! @kudzu.fsu

Stay up to date on all things Kudzu via our social media!