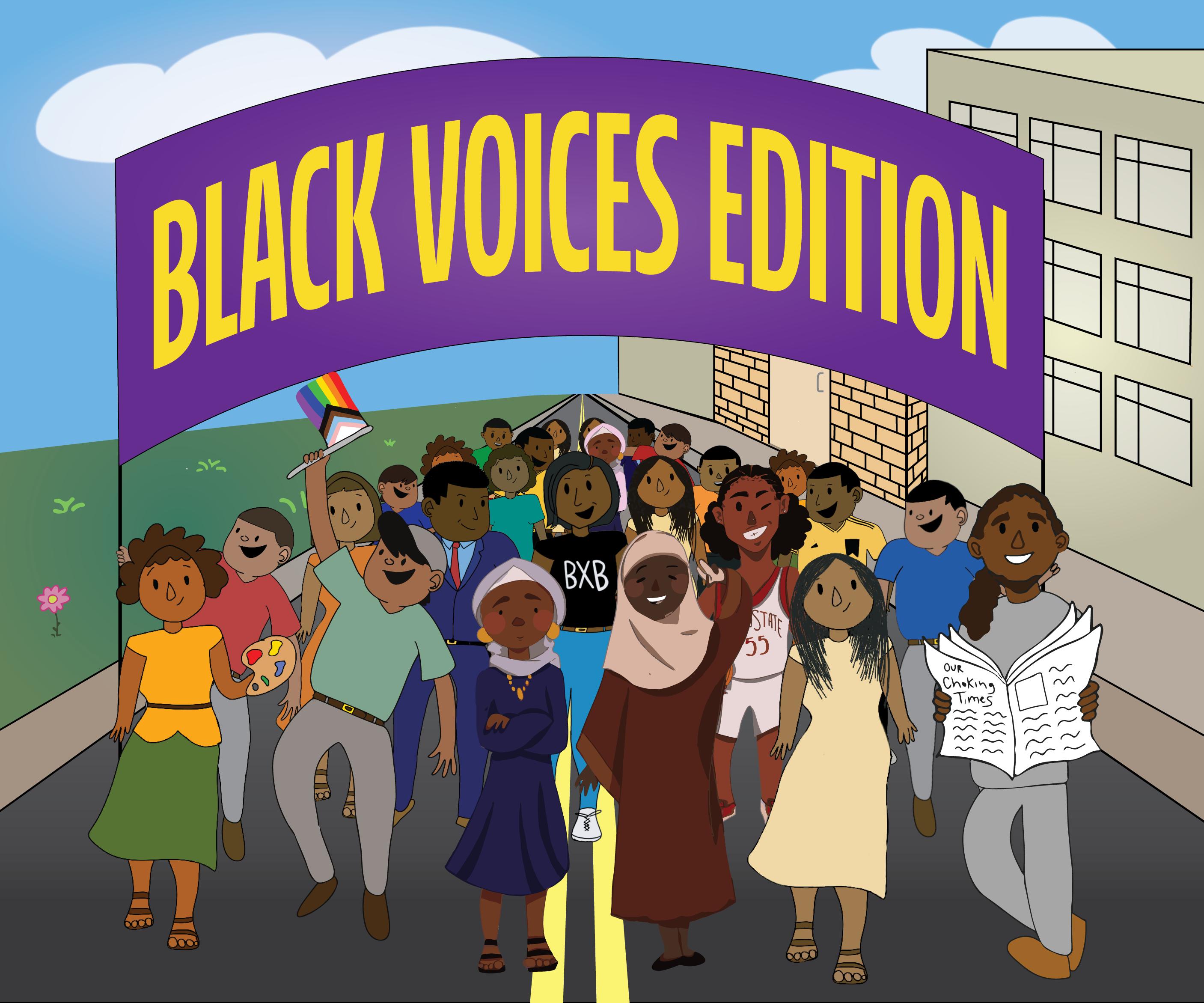

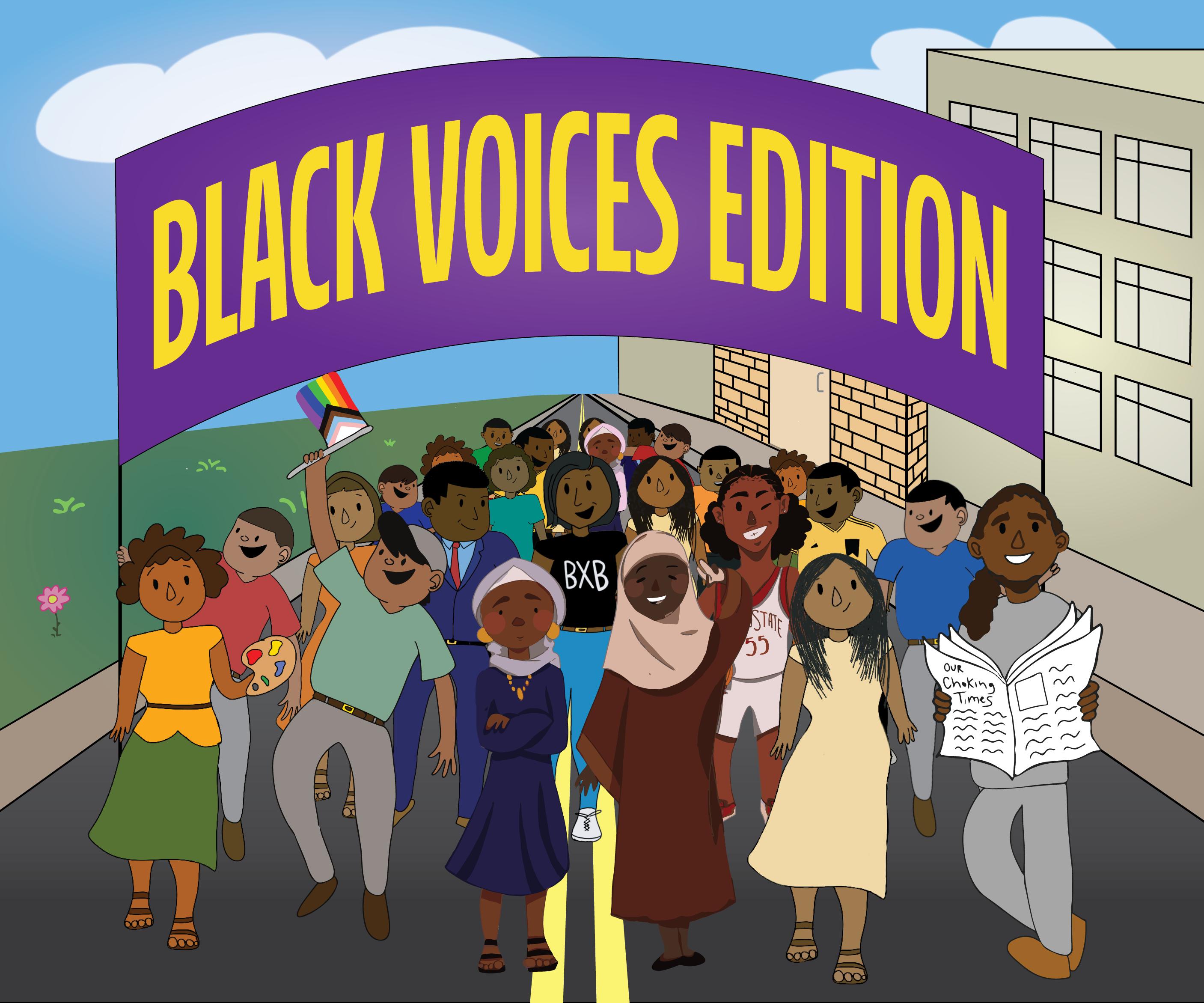

By Samantha Harden Lantern Arts & Life Editor and Reilly Ackermann Lantern Asst. Campus Editor

As diversity, equity and inclusion programs face further attack by the federal and state governments,ward removing its own DEI initiatives across campus.

Feb. 27, university President Ted Carter Jr. announced Ohio State would Inclusion and Center for Belonging and Social Change the following day, positions, per prior Lantern reporting. openly shared their outrage by protesting in the days following the decision, mourning what has been lost and calling upon the university to protect its DEI programming from further cutbacks.

Now, student organizations across campus are wondering what will happen to their clubs’ own DEI initiatives following these changes.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People at Ohio State

On May 2, 2024, Ohio State’s chapter of the NAACP, along with 33 other student organizations, collaborated to write “A Student Address to University Admin and President Ted Carter Regarding Protection of DEI at The Ohio State University.” The letter — shared to Instagram — discussed why the unito students.

Isaac Wilson, a fourth-year in aerospace engineering, president of Ohio State’s NAACP chapter and a key leader in drafting the address, said the document’s goal was to bring attention to concerns surrounding Ohio Senate Bill 83, while also informing Carter — who

the university’s DEI initiatives.

Senate Bill 83, essentially the ideological predecessor of Senate Bill 1, aimed to eliminate DEI course and training requirements for Ohio’s higher education institutions, per prior Lantern reporting. SB 83 was heavily criticized by students and faculty at Ohio State, passing in the state Senate but failing to gain approval from the House of Representatives.

“[Carter] was very new to the university, so I think it was very informative to him — hoping that he and having a strong coalition of students, having over 30 organizations come together to sign something so impactful,” Wilson said. “It cametives, so I think that was something that [Carter] just needed to hear.”

Wilson said when he learned

FAITH SCHNEIDER | LANTERN PHOTOGRAPHER

Samuela Osae, a third-year in molecular genetics and co-president of the Black Mental Health Coalition, said DEI is often a determining factor in shaping a student’s college experience, remarking “DEI saves lives.”

mission on this campus.”

programming Feb. 27, he felt “frustrated but not surprised.”

“A university of this size, the one thing they’re going to try and protect is their money,” Wilson said. “All I’ll say is a leader that supports [their] community will be supported by [their] community, and it’s unfortunate because I thought that [Carter] would have fought harder.”

Wilson said the news of Ohio State’s programming cuts is especially disheartening because the NAACP’s primary goal is to raise awareness about DEI-related issues.

“We focus our programming [on] ensuring that students on this campus know how to vote, know who is on the ballot, understand the disparities that happen within the health sector, unnot choose you because of the push said. “Being able to educate the community about DEI has been our main

Wilson said since Ohio State’s NAACP chapter is part of a larger national organization, it won’t need to change its name, programming or mission statement. However, he said the organization has discussed the potential of federal funding cuts.

“We’re just trying to outsource with a lot of alumni, as well as the NAACP Columbus chapter, and trying to gain funds that way so that we can operate as we please and continue the programming that the students need,” Wilson said.

Scarlette Magazine — a student-ledmester.

As Scarlette has grown over the years, Jasmine Freeman — a thirdyear in psychology and the magazine’s DEI chair — said having a formal DEI executive position was a must for the

organization in order to cement the importance of diversity. Since taking on her role this semester, Freeman said she makes sure the magazine features ethical photography and inclusivity in hair, makeup and skin and body types.

Freeman said Ohio State’s recent DEI changes are disappointing for both the club and her personally, as she is a recipient of the Morrill Scholarship. Although the Morrill Scholarship will continue, its eligibility criteria “may the law,” according to a Feb. 27 Ohio State News article.

Beyond the Morrill Scholarship

she is concerned the elimination of ODI will limit future students’ access to on-campus resources.

“Hearing all of the changes go back and, like, hearing that some students moving forward aren’t going to be able to have the same opportunities that I would have is really frustrating to me because it feels like we’re taking so many steps back and not progressing,”

Freeman said. “And I just hate to hear lot of people.”

In terms of the magazine, Freeman said DEI is a value it will continue to uphold, as it is embedded in Scarlette’s club constitution. However, she said many members are worried there could be issues with receiving university funding in the future.

“If it becomes a problem in receiving funding or support from the university, then we have discussed potentially changing the name of what our chair would be to either like a ‘photography ethics chair,’ or something of that nature,” Freeman said. ”But it is not fundamentally changing what our goals are or what our values are as a club.”

When asked if student organizations would lose their university funding if their name, mission or executive positions were DEI-centered, university spokesperson Ben Johnson said because student organizations are, by changes needed at this time.”

Ultimately, Freeman said she thinks student organizations are doing the best they can to adapt to changes without compromising their club’s values.

“Hopefully, it’s not like this forever, and we can keep DEI chairs, and DEI implementations and everything, but for the moment, we’re just going to adapt and overcome,” Freeman said.

Ayana Runyan, a third-year in anthropological sciences and vice president of the Minority Collegiate Outreach and Support Team — or MCOST — said she worries not only for the future of current Ohio State students, but also for students who are planning to attend the university in the future.

“I feel like it can be a little detrimental to our youth education and rights for equality and equity,” Runyan said. “I feel like we’re kind of moving backwards in history for everything that the people who came before us have fought for — our rights that we have today.”

For MCOST, which aims to support underrepresented students in middle

and high school by providing them with mentors who represent them, Runyan said the rollback of DEI pro -

the organization to serve its community.

“It kind of hinders our ability to properly have a voice — on campus and -

dle schools — and then also acting on the things we believe in regarding the DEI,” Runyan said.

Many of the students MCOST works with are recipients of the university’s Young Scholars Program, which students from nine districts across the its website.

The scholarship — previously housed under ODI — provides over aid. Runyan said the organization is concerned that if the scholarship was to be removed in the future, the students they work with will lose their access to higher education.

“A lot of the high school students have YSP scholarships, and with the removal of DEI and ODI, it’s kind of like, ‘Where do we stand with this key [issue], and being underrepresented [would] have less access to college because they have to pay for school versus the scholarship.”

The Young Scholars Program will continue, though its eligibility criteriaance with the law,” according to a Feb. 27 Ohio State News article.

Runyan said ultimately, the organization fears that marginalized students will not have the opportunity tosity community.

“Overall, I’m just really concerned about not being able to show underrepresented students that there are people who look like them and that are them, so that they’re more comfortable being in spaces like a [predominately white institution],” Runyan said.

African American Voices Gospel Choir

Shawnta Hunter, a fourth-year in music performance and alto section

leader of the African American Voices Gospel Choir, said though the organization’s mission statement doesn’t explicitly include DEI initiatives, its key goal is to create a space where Black students in the arts can showcase their voices. However, Hunter did note the choir is inclusive and allows anyone to join, regardless of race.

“With me being in music and being in the arts for as long as I have, there is a lack of diversity, and equity and inclusion,” Hunter said. “Especially in orchestras, I don’t see enough people

don’t see enough women in orchestras. Having these people have this access is just so important to me.”

on-campus space where students can authentically be themselves — a place to connect, build community and immerse oneself in the rich culture of gospel music. She said she hopes the group’s atmosphere will remain unchanged, despite the initial removals of DEI programming.

“Gospel music has a deep culture to it, and we’re not erasing that — that’s not negotiable,” Hunter said. “They can’t get rid of us. I refuse to let that happen.”

-

continuation of the university’s DEI programming is both upsetting and alarming, she believes those committed to preserving its goals and mission will demonstrate that DEI cannot be easily dismissed.

“This is not something that we can just get rid of,” Hunter said. “It is not going to happen that easily. You can say, ‘Stop using these words, and stop doing this and that,’ but it’s not as easy as people are making it out to seem.”

Hunter said in a recent executive board meeting, members discussed the possible changes they would need to implement in light of Carter’s Feb. 27 announcement.

“Really, we’re just not trying to go anywhere,” Hunter said. “Even if they get rid of the words DEI, we’re going to rearrange our constitution, and we can change our names if that’s what they want, but we’re not going anywhere.”

Black Mental Health Coalition

Samuela Osae, a third-year in molecular genetics and co-president of the Black Mental Health Coalition, said the organization’s mission is to provide students with opportunities to engage in discussions and activities aimed at breaking the stigma surrounding mental health in the Black community, a goal deeply rooted in DEI values.

“What we do really tackles that point of helping students, especially ones who struggle with mental health — particularly in the Black community — get acclimated to the school setting because that is where changes in mental health tend to happen the most,” Osae said. “In my experience, it was not something that was embraced in my community, in my home life, before college, and [the Black Mental Health Coalition] was really helpful to me.”

Osae said the organization has discussed making potential alterations to its mission statement and advisor support network, as well as the possibility of a name change in the near future.

“I’m assuming we’re going to have to change it to a general mental health club, and I feel like that defeats our initial purpose of ending the stigma withsaid. “That stigma isn’t experienced the same way in other communities. It just feels like that identity aspect is being stripped away.”

Without ODI and CBSC supporting the university’s shared mission to maintain a commitment to diversity, Osae said it feels less meaningful. Osae also pointed out that on the steps of the Ohio Union’s main staircase, “diversity” is printed as one of Ohio State’s core values.

“I just feel like the integrity of the values are not being upheld if DEI programming is not upheld because I feel like that is a core value for why a lot of

Osae said. “It just felt like if I came here, I knew there was going to be a place for me, and it doesn’t feel that way anymore.”

Ultimately, Osae said DEI can be the determining factor in shaping a student’s college experience.

“DEI saves lives,” Osae said. “We had that on a poster, but it really is true.”

By Kyrie Thomas BXB Vice President and LTV Campus Producer

On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act, which aimed to prevent discrimination on the basis of race, gender and other identifying factors in regard to obtaining housing.

Though the bill was widely regarded as a net positive for Black people across the United States, John S. Evans — a Black student at Ohio State during the time — saw it as an empty promise.

“It’s just something else on a piece of paper,” Evans said in a 1968 Lantern article, which was obtained via the University Archives. “If we followed the Constitution, we wouldn’t need civil rights bills anyway.”

At the time, Evans was an informal spokesperson for the Black Studentganization founded in 1967, in which all Black students were considered members, according to a 1969 Lantern article obtained via the University Archives.

In protest of the bill due to its pergathered to express their opposition and demand Ohio State take more immediate action to aid Black student housing access in the Columbus area. According to the 1968 Lantern article, Evans said the white Ohio State community “overreacted” to the demonstration.

“The overreaction showed that whites are still fearful of Blacks,” Evans said in the article. “Peace groups can have their demonstrations on the Oval without incidents, but look what happens when a black group tries to assemble.”

That same year, only 14 days later on April 26, BSU organized one of the most notable protests to ever take place on the university’s campus — an attempted encampment inside the Ad-

RIGHT: Students protesting against Ohio Senate Bill 1 near the Oval Tuesday.

ministration Building, now known as Bricker Hall.

Around 75 members of BSU met with administrators — who worked in the Administration Building — to share their grievances toward the “alleged university acceptance” of cultural- and housing-based discrimination, according to another Lantern article from the same year. Meanwhile, hundreds of others occupied the building in protest.

“About 200 members of the campus Americans for Democratic Action and the OSU Committee to End the War in same time the BSU occupied the sec-

The overall demonstration by BSU has been credited as a direct factor in the creation of Ohio State’s Black Studies Department — now known as the Department of African American and

These departments have remained color, as well as the gradual change in university policy to accept and accommodate their concerns — that is, until Feb. 27.

In a University Senate meeting, university President Ted Carter Jr. announced the removal of ODI and the Center for Belonging and Social Change.

These changes come in light of several executive orders from President Donald Trump’s administration, a notice from the U.S. Department of Education and the progression of Ohio Senate Bill 1.

In the days following the announcement, students across campus have organized and attended sit-ins and pro -

tests — all in opposition of SB 1 and the university’s DEI-related decisions. Isaac Wilson, a fourth-year in aerospace engineering and president of Ohio State’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said though the early actions of BSU gave way to greater representation on campus, the members’ struggles have begun to hit a little too close to home.

ing to advocate for the same rights and decisions that we literally overcame back in the ‘60s,” Wilson said. “Like I said [Tuesday] at the protests, it feels like we’re in that ‘70s range, where we technically have rights, but are still

The same call to action that’s been echoed from BSU also rang from Af-

By Daranii Asoba Lantern Reporter

The Ohio State African American and African Studies Community Extension Center has been a long-standing pillar of support for Columbus’ Black community since its founding in 1972.

The center aims to “provide academic and community education opportunities for its Near [East Side] neighbors and the greater Central Ohio community,” according to its website. Just last year, the center — located at 905 Mt. Vernon Ave. — reopened to include a new library, meeting hall, classrooms and updated technology in order to better serve its community.

The renovations were made possible by a $1 million state appropriation from Ohio State Sen. Hearcel Craig (D-Columbus), according to the College of Arts and Sciences’ website.

Department of African American and African Studies and former director of the center from 2006-14, said the renovations will allow for improved outreach within the Columbus community.

“The CEC has undergone renovations, now equipped with more modern equipment, which allows for

These renovations have brought the center into a new era of creating future change, said Monica Stigler, the center’s current director.

“The center has been a safe space for many years now, where folks can come in and learn about Ohio State resources and programs right in their neighborhood,” Stigler said. “My responsibility is to continue that legacy for the next generation.”

The center’s history

Similar to many initiatives of its time, the Community Extension Center was born in 1972 out of a nationwide grassroots movement, Stigler said.

Founded in 1972, the Ohio State African American and African Studies Community Extension Center — located at 905 Mt. Vernon Ave. — provides educational opportunities for the Near East Side neighborhood and Central Ohio. Last year, the center reopened with a new library, meeting hall, classrooms and updated technology to better serve its community.

“Students, organizers and faculty at predominantly white institutions emphasized the need for a Black Studies Department that looks at the intersections of race, citizenship, class and

Black people in this country,” Stigler said.

These protests — which took place prior to the establishment of the CEC in the late 1960s — led to the creation of a Black studies academic division in 1969, now called the Department of African American and African Studies.

of the then-Black Studies Department, created the CEC to engage with the historically Black Columbus community robustly and authentically, bridging the gap between the community and Ohio State, Stigler said.

focused on educational programming and activities that enhanced quality of life for Black people. One of many

director was a math and science pro -

the project, Ghost Neighborhoods, that looked at mapping old buildings, landmarks and sites where communities used to be, but now are gone because

pull factors of change over time,” Stigler said.

Many of the diminished communities were predominantly Black, and the CEC works with elders from those communities to archive and publicize those aspects of Black history, Stigler said.

“We want to make sure that we are capturing some of those memories that stand the test of time, even though buildings have gone,” Stigler said. “The fabric of this community has always who’s come to live, work or play here.”

gram for grades four through 12.

“We cultivated a love of math and science in kids so they would be -

er literacy classes for senior citizens they are a “group of people who were less likely to be technologically sophisticated,” he said.

The center now

Today, the center has shifted its focus toward community-oriented scholarship, Stigler said.

“We are a hub for faculty throughout the university, who have public-facing research ideas or want to engage with local communities, particularly Black communities,” Stigler said.

The CEC is currently partnered with the Ohio State Center for Urban and Regional Analysis, which focuses on city and regional planning, Stigler said.

“We worked closely with them on

One of the center’s future projects aimed for completion by fall 2025 is a new podcast titled “Black to Basics,” which looks at Ohio State’s Ten Dimensions of Wellness through the lived experiences of the Black community, Stigler said.

The topics will include current issues such as housing and the economy, featuring expert professors and students with relevant experiences in order for the podcast to contain multiple perspectives, Stigler said.

“I’d like for us to be able to take some of the research and data that is produced every day at OSU and translate that more intentionally so that community members can interrogate it and interact with it in more meaningful ways to become their agents of change in their lives,” Stigler said.

Stigler hopes that, moving forward, the center can work toward empowering the Columbus community to advocate for lasting policy changes, which begins with the research it is currently doing — such as its previous research project, Ghost Neighborhoods.

“People need to be able to understand the landscape of a particular issue much more deeply, and then betions about it in their community,” Stigler said.

By Jackson Hall Social Media Editor

In 1970, Black students at Ohio State founded Our Choking Times, a publication designed to critique the university’s lack of diversity and provide a platform for marginalized voices.

More than 50 years later, a new exhibit at Thompson Library explores the student-run newspaper’s impact, showcasing its contributions to activism, cultural expression and community-building.

Housed in the Ohio State University Archives, Our Choking Times covered racial inequities on campus, from the university’s lack of Black faculty to broader social injustices, according to the Library’s archive website.

Tracey Overbey, an associate professor in library sociology and co-curator of the exhibit, said beyond activism, the newspaper also provided a space for poetry, cultural criticism and students’ perspectives. The exhibit brings key moments from the publica-

visitors a deeper look at the challenges and triumphs of Black student life at Ohio State.

Overbey said uncovering Our Choking Times in the archives felt like a rare discovery.

dent newspaper at Ohio State,” Overbey said. “It was really wonderful. It

On display until June 22 on the exhibit presents a selection of archived issues, photographs and historical

into the era that shaped Our Choking Times, Overbey said. Featuring dim lighting and music from notable Black artists of the time — including Michael Jackson and Earth, Wind & Fire — the exhibit’s space immerses guests in the newspaper’s cultural and political sig-

“The exhibit sends a message of accomplishment,” Overbey said. “The paper was [created] during a time when students wanted to see a Black studies department, more Black faculty, and they wanted to see more Black books and [a] Black librarian. From the late ‘60s to the ‘80s is when a lot of accomplishments happened. Students would write to administrators and use the proper channels to get their voices heard. They came together and found a way to bring people together. Now, today, we do have a [Department of African American and African Studies], and we do have Black books.”

can American and African Studies, was a keynote speaker at the exhibit’s opening reception Feb. 11, though

said Our Choking Times holds a great highlighted how Ohio State’s history of student activism often goes unrecognized compared to other universities from the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“You see University of Chicago, University of Michigan, Kent State University and University of Wisconsin,” Jeffries said. “There’s no book, no journal, no article, no documentary [referring to Ohio State’s history].”

-

ing behind the newspaper’s title, explaining that the name “Our Choking Times” stemmed from “the joke of feeling the strangulation of oppression around your neck.”

“The point is to rid oneself in that yoke of depression so you can breathe,

part of a larger power movement for Black people, pushing for more than just civil rights. He also noted the publication served as a way to introduce Black students’ culture to the broader campus community.

“Our Choking Times called for human rights and began a movement for

Uma Farrow-Harris — a fourth-year in radiologic science and therapy, as

well as a University Libraries employee who helps work the exhibit — said in the wake of recent changes to diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives at Ohio State, exhibits like “Our Choking in highlighting the importance of activism and remembering past struggles for justice.

Farrow-Harris also said visitors often engage with the space in ways that feel deeply connected to the university’s present-day conversations about DEI and student activism.

“It’s important that history doesn’t repeat itself,” Farrow-Harris said. “Exhibits like these are important because they show that people can act independently. A lot of the challenges we’re facing now are not unprecedented. Fortunately, we have playbooks on what works and what doesn’t.”

In addition to broader themes of activism, Farrow-Harris highlighted a feature of the exhibit called “Where We Go From Here,” which she said invites visitors to engage more personally with the history on display.

especially given the beautiful piece of artwork next to it that invites visitors

it something that you’re proud of,” Farrow-Harris said.

Overbey emphasized the positive message she hopes the exhibit conveys.

“We wanted this exhibit to be inspiring, and that’s exactly what it is,” Overbey said. “As James Brown said, ‘I’m Black and I’m Proud.’ The students are proud of who they are, their heritage and their connection to Africa and Indigenous Americans. You see that

exhibit showcases growth and puts Black students in a positive light, highlighting their great journalism work. I hope the community comes out to see it — it’s something truly positive.”

For more details about the exhibit, visit the Ohio State Libraries webpage.

ro-Am, another Black-led student organization, which was founded in 1969 following the encampment at the Administrative Building by BSU, according to a 1970 Lantern article obtained from the University Archives.

Afro-Am remained active on campus throughout the ‘70s, focusing its attention and resources on increasing the recruitment and educational rights for Black students and protesting the university’s investments in companies that had business relations with apartheid-era South Africa, according to a 1977 Lantern article obtained from the University Archives.

In May 1974, Afro-Am held an assembly focused on fostering Black unity and creating an open dialogue surrounding the issues students within the community faced, according to the same 1977 Lantern article.

“About 200 Black students, faculty members and administrators attended the rally to hear discussion of the proposed elimination of the Black Education Program in the College of Education,” according to a Lantern article from the same year.

Though history is seemingly repeating itself with the issues that Black and other minority students aretween then and now — and what needs to be resolved — is a current lack of community, largely due to the divisiveness rampant in modern society.

“It is essential that we have that community because at the end of the day, they’re not going to respect us if there’s no numbers behind it,” Wilson said. “If we don’t make ourselves the majority by making the majority of the noise [and] the majority of numbers, they can literally brush us to the side.”

and treasurer for the Black Student Association, said though Black students are calling for the support of all members of the university, he can un-

ciently educated or aware of the issues at hand.

“It is very interesting, and hard and confusing for individuals who have never been the minority or interacted with minorities to understand what it

feels like to be in those minorities — especially those who have never inter-

ized groups,” Jones said.

However, even for those who may not feel like they are directly impacted by the issues Black and other minority students are facing, Jones said there are still ways for them to show support.

“Just the best thing you can do, it’s like the saying: The best thing you can do is show up,” Jones said. “I think

seen throughout my collegiate career.”

key factor that dates back decades. In 1977, William Nelson, former chairman of the Department of Black Studies, demonstrated his backing for students at an on-campus protest, which helped to turn the tide of students’ efforts.

“For too long, Nelson told the crowds in front of the Administration been silent, but with an organization now, we are placing our unity behind a 1977 Lantern article detailing the protest states.

Wilson and Jones each referenced the consistent guidance seen from

in the recent demonstrations across campus. They said their support parallels the same frustrations and demands for change Nelson advocated for 48 years prior.

“‘We’re not asking for favors,’ [Nelson] told the group. ‘We want our rights, and we’re going to have our rights or this institution as it presently exists will not exist,’” the same Lantern article states.

When discussing the recent alterations the university announced to its DEI programming, Wilson said students must take it into their own hands to create the change they want to see.

“Things don’t just happen to you because we all have choices; we all have decisions that we have to make as human beings,” Wilson said. “It is an active decision to stand up. It’s an active decision to push forward, but you and everybody else is going to be the ones who have to make that choice.” ACTIVISM continued from Page 4

By Xiyonne McCullough BXB President

Within the Black community, hair is more than just a style — it’s a form of self-expression and cultural connection. Yet, these trends are often overlooked in mainstream media due to a lack of cultural understanding.

From gravity-defying afros to the wide-ranging diversity and creativity of their community’s hairstyles on campus. But many still feel overlooked or judged from the world at large. Now, Ohio State students are weighing in on how Black hair shapes personal identity while representing a grander collective beneath the bundles.

Historically, during the Civil Rights Movement, afros became a symbol of Black pride and resistance against Eurocentric beauty standards. Today, however, Black hairstyles are often judged based on people’s perceptions of professionalism, leading to discrimination in schools and workplaces, according to the Brookings Institution.

With hair serving as a predominant form of expression for many students, Brielle Shorter, a third-year in psychology, said she frequently senses a feeling of underlying bias from her peers.

“I do notice people are extra complimentary when I have straight hair versus when I’m wearing my hair naturally curly,” Shorter said. “And I think there is a little bit of a bias there that I wish people unpacked a little more. Like, why do you have a preference for straight hair?”

Shorter said receiving looks and stares based on her hairstyles can sometimes impact the way in which she views herself, creating a sense of isolation.

“It feels like you’re being denied,” Shorter said. “It’s like someone com-

ugly, your whole style is ugly — change it immediately.’”

Considering Ohio State is a predominately white institution, Trent

Robinson-Brooks — a third-year in biological engineering — said he often expects his hair to create confusion for those outside of the Black community.

“If you’re at a PWI like this, you expect to draw attention to yourself,”

Robinson-Brooks said. “If you try to do something unique or less traditional

to turn a few heads, and people might make comments about your hair.”

hairstyles can carry a certain variety of interpretations, oftentimes resulting in Black students altering their hair

when I have my hair out versus when it’s braided in cornrows,” Robinson-Brooks said. “If I was going for an interview at a job, I would feel more inclined to just keep my hair out rather than having it in twists, for example.”

Like many Black students, Robinson-Brooks said he has gotten used to

the attention his hair garners, whether positive or negative. But throughout his time at the university, Robinson-Brooks has been able to shape his mindset in order to not isolate or devalue himself based on how others perceive him.

“Being at the school for two years now, it doesn’t really bother me like that, but I try to look at it as people trying to be nice because you can look at it in multiple ways, but I just try to be positive,” Robinson-Brooks said.

Despite facing judgment from others, Samuela Osae, a third-year in molecular genetics, said her hair has served as a bonding opportunity for both herself and the other Black students surrounding her.

easy bonding topic,” Osae said. “Immediately when I see someone’s hair, I’m like, ‘Girl, I’ve got to copy this,’ and things like that just help me connect. Then, when people compliment your

hair and start talking to you, you guys start to have a whole conversation.“

Shorter said she has experienced similar situations, which have helpedties and connection of hair expression.

“It’s really cool to have similar hairstyles as other Black women,” Shorter said. “It adds to the community connections.”

and varying opinions that surround the expression of Black hair, Osae said she hopes those outside the Black community will think twice about the culbehind each hairstyle before passing any judgment.

“Hairstyles [are] art at the end of the day,” Osae said. ”You don’t have to do anything crazy to let the person know you like it. Just admire and go about your day.”

By Kyrie Thomas LTV Campus Producer & BXB Vice President

Among the various identities any given individual possesses, there exists a combination of intertwining traits that shape who a person is and will become.

SHADES is a student organization dedicated to fostering a safe space and raising awareness for the intersectionality between people of color and LGBTQ+ student communities on campus.

Though the university has several spaces for the POC and LGBTQ+ communities individually, Akasha Lancaster, a third-year in psychology and co-president of SHADES, said having an organization that highlights the crossover between both identities has

necessarily wrong with that,” Lancaster said. “But again, it was just that one piece of disconnect where there are still some issues within that community as well.”

Creating an environment in which people can come together with others who share similar experiences and struggles is something Ileia Wou, a third-year in psychology and the other co-president for SHADES, said is a focal point for the organization.

“It’s important for people to have a safe space,” Wou said. “Even if they are allies and, you know, they accept it, they won’t necessarily have gone through what you went through, and it’s nice to have support, but it’s also needed to have those people that have gone through what you’ve gone through.”

orgs here at OSU, but as someone who able to be surrounded by people who understand you in more than just one way,” Lancaster said.

Despite the fact both groups have faced discrimination due to being marginalized communities, Lancaster said

community to be understanding toward the other.

“I can recognize and understand that the Black community has its issues within itself that need to be worked on,” Lancaster said. “So, I felt like there were some times where I would have encounters with people who were not accepting of my other identities as a person who does not necessarily identify as a woman or straight.”

Similarly, Lancaster said the intolerance from parts of the Black community can sometimes bleed into the LGBTQ+ spaces they inhabit.

“Especially with OSU being a [predominantly white institution], a lot of the LGBTQ spaces are predominantly white people — and there’s nothing

In light of recent executive orders from President Donald Trump’s administration aimed at cutting federal funding for diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives — as well as the univer-

Diversity and Inclusion and the Center for Belonging and Social Change — Wou said many members of the campus’ minority populations feel at a loss.

“First, they decolored the CBSC, and then now, they’re eliminating and getting rid of it, and it kind of feels like they’re erasing and silencing a part of my identity,” Wou said. “When that people started crying. We were absolutely devastated.”

In an August 2024 email correspondence with Black and Bold Magazine, Aliya Beavers — a director for individual cohorts for various identity groups with an all-encompassing weekly group meeting titled “community connections.” Beavers said this decision was made due to “extremely low attendance” for separate cohort meetings, as well as to account for the wide range of identities students hold.

Wou said losing these individual cohorts made some Ohio State students

— including herself — interpret the change as a form of decoloration at the university.

SHADES has existed on Ohio State’s campus for over a decade, and when it comes to advocating for the rights of POC and LGBTQ+ campus communities, Wou said the organization will continue to push through any roadblocks.

“We’re going back in history, but it always plays out, and I believe good will come no matter what, even if it takes a long time,” Wou said. “We’ve just been oppressed so much that it’s terrible, but we can do it. We can just

keep pushing.”

Regardless of the changes taking place, Lancaster said the education, resources and safe spaces SHADES is able to provide the POC and LGBTQ+ communities will remain.

communities within such a big community — helps them feel more at home, more comfortable around people that they can connect with better,” Lancaster said. “It gives students who have intersecting identities the comfort of knowing that there are other people like them.”

By Xiyonne McCollough BXB President

In November 2024, Hadja Bah, a third-year in nursing, decided it was time to use her 10 free therapy sessions through Ohio State’s Counseling and Consultation Services.

Four sessions in, the absence of Black Muslim therapists left her feeling misunderstood, which quickly inspired her to create a space for change.

Black-founded Muslim Mental Health Coalition aims to support students of all backgrounds in their mental healthphasizing aspects of Islamic wellness to help mitigate stigma across campus.

Bah said the group’s advisor, Dr. Hoda Hassan, specializes in psychiatry at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Since the organization is so new, Bah said Hassan has been formally introduced to the club and hopes to become involved with regular events in the future.

As president of MMHC, Bah said one of her goals is to foster an inclusive space where membership is not restricted based on religion, and all are welcome to attend — regardless of their background.

“I want to be able to provide for Muslims, but also for non-Muslims because I feel like Islam has so many mental health resources,” Bah said. “I keep it to the Muslim community when it’s available for everyone.”

Bah said she had initial doubts about starting MMHC due to the orga-

President Yasmin Ejeh, a third-year in nursing, assured her it was necessary for the Black Muslim student community to have this resource while coping with worldly events.

“We just needed a place that creates inclusion and explores the mental health challenges, topics and stigmas that go on with it — especially for Black Muslims,” Ejeh said. “We were literally

talking about it in December, and now we’re a whole org. It’s amazing.”

This semester, the organization has

“Ramadan Gauntlet” Feb. 27, providing students with ways to get involved with Ramadan — the Muslim holy month, marked by daily fasting from dawn to sunset and ending with the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Fitr.

talking about what our org really is about, like your typical introduction,” Ejeh said. “Our second event, which was a week later, was about Ramadan, with stations and having fun before Ramadan started.”

Members of the organization, such as Abdikadir Mursal, a third-year in computer and information science,nority groups face when searching for campus.

”With being Black, African and coming from a Muslim house problem and makes it even worse when you feel

like there [aren’t] really any resources out there for you,” Mursal said.

Salmah Mohammed, a third-year in nursing and MMHC treasurer, said she faced a similar problem in seeking out mental health resources tailored to her personally.

“I feel like a lot of campus mental health services aren’t culturally or religiously competent,” Mohammed said. “Things like faith, our racial identity or the stigma around mental health in our community just don’t get addressed.“

By transforming their struggles into action, MMHC members hope to

wellness spaces on campus, but also within the broader Muslim community.

“We just want to foster that sense of community on campus where students feel like they have a family, and can come together and have open conver-

sations about anything,” Mohammed said. “And just know they’re not alone.”

Mohammed said she believes some individuals may feel afraid to talk about their feelings due to fears of acceptance and the overall stigma surrounding emotional health.

“A lot of people fear being judged, whether it’s from friends, family or even the broader Muslim or Black community,” Mohammed said. “They just feel like it’s shameful to be struggling mentally.”

Despite the organization’s recent emergence, Bah said MMHC is already planning to host more community-building and outreach events, all with the goal of fostering inclusion and security for students who need an on-campus safe space to turn to.

“Our goal is to leave a legacy behind where we’re being more proactive than reactive to situations,” Bah said. “Now, there’s a space for people to come and talk.”

More information about the organization can becial Instagram page.

GUILD continued from Page 12

and she had started to come out to that every week, and so then we really started to engage and to know one another.”

In 2022, Woods said he was in the early stages of developing the Streetlight Guild’s studio spaces, so he invitresident artists that year.

Lawson said the decision to become a resident artist was an easy one, as the guild’s mission aligned closely with her own values.

“Streetlight Guild is an institution, a cultural institution in that it magni-round the city, and that has always been important to me,” Lawson said. “Streetlight Guild has done a very good job in that it has found a way to prenitely a treasure.”

Streetlight Guild took place in 2023.ment of her “Contemporary Color Deluxe” traveling show — a retrospective featuring 23 pieces that encapsulated a decade of her career.

“I am very appreciative of Streetlight Guild for allowing me to show the leg,” Lawson said. “It was at the Ohio State Faculty Club, then it went to Sean Christopher Gallery down in the Short North and then it had felt like a homecoming to show it at the Streetlight Guild last.”

Woods said in addition to promoting the work of local Black artists, it’s crucial to preserve the history of Black art. He said this is what led him and Lawson to jointly create the “Black Columbus Visual Artists List.”

“Part of Streetlight Guild’s mission is to create Columbus culture, and part of that work is building resources that people can use,” Woods said. “Having information in hand about the scale and amount of art in certain contexts can be a powerful tool.”

Woods said he and Lawson have been working on the list since last summer, dedicating countless hours to researching artists, reaching out to them and discussing additional names

based on their own connections. Initially, their goal was to include just 100 artists, but Woods said Lawson quickly realized there were many more to recognize, leading them to expand the list to 200 names.

“If you worked in Columbus in art in the last 50 years and you’re Black, then you’re probably on that list,” Woods said. “And if you’re not, well, we hope to continue to add to it.”

Woods said the guild will continue to update the list with new names every six months. Additionally, he said he and Lawson maintain a more extensive database that includes details such as artists’ birth and death dates, preferred mediums and whether they were born in Columbus or simply worked there — information he hopes to incorporate into the public list in the future.

With diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives facing growing uncertainty, Woods said the work of Streetlight Guild — especially projects like the “Black Columbus Visual Artists List” — is more vital than ever. He also emphasized the need to provide Columbus artists, especially those whose voices are often marginalized, with the space to present their work on their own terms, ensuring their diverse perspectives are recognized rather than suppressed.

he has felt grateful to have the opportunity to watch Streetlight Guild ex-

events that occupy the space continue to evolve.

“Art is not like selling insurance; it’s interesting and varied, and you have to keep trying new things,” Kizer said. “The best thing about it is that the original idea is still there, but what [Woods things. He’s been able to do a whole because he tries things, learns from them go and tries something else. In a way, the building is like a piece of art. It’s not the same as it was, but it’s in the same vein.”

“If you live in a society that is attacking concepts like diversity and equality, you should be doubling down on cultural things,” Woods said. “And culture isn’t just the arts; people con-

tirely art. Culture is many things — it is the way that we live; it is our language; it is our passion; it is our ideas; it is our values, and so art allows us to access those things directly and in a way that makes sense to us.”

Kizer said in the years since the guild opened, he has moved away from the Columbus area to be closer to his grandchildren, but still makes time each year to return to the venue.

“Every time I’m in there, I get tears in my eyes,” Kizer said. “It’s a bunch of great artists doing great work, with great audiences, and everybody appreciates it and it’s just wonderful.”

Streetlight Guild is open every Saturday from noon to 3 p.m., with additional hours varying based on scheduled events. For more information about Streetlight Guild, including access to the “Black Columbus Visual Artists List,” visit its website.

By Samantha Harden Lantern Arts & Life Editor

Thedate was March 3, 2017. It was also day three of art event organizer Scott Woods’ month-long series, titled “Holler: 31 Days of Columbus Black Art.”

The dimly lit back room of Kafe Kerouac pulsed with the sound of guitar solos reverberating from bookcase to bookcase.

As Columbus-based rock band The Turbos neared the end of its set, Woods took it all in — the music, the event series, the joy of getting an opportunity to showcase Black art in his city. It was just after 8 p.m. and the night was nearly over when a tall, sophisticated-looking man with salt-and-pepper- — but mostly salt- — colored hair approached him.

The man asked Woods what it would take to make something like Holler happen year-round.

With a sarcastic tone, Woods said, “Well, a venue would be nice.”

Visual Artists List” this February. The list, he explained, is a database featuring the names of 200 Black artists from Columbus over the past 50 years.

Clearly, Woods is no stranger to Columbus’ arts and culture scene.

Prior to opening Streetlight Guild, Woods said he had organized various arts-related events, including Writers’ Block Poetry Night at Kafe Kerouac

and programs. However, he said he eventually realized that having a dedicated space for this kind of cultural and artistic exposure would be essential in Columbus.

“It ultimately became clear that a space was needed that was dedicated to constantly putting those artists forward,” Woods said. “I had no idea when or how that might happen, and I was getting to a point in my life where I thought it may never actually happen.”

artists and organizing poetry readings, book

What Woods didn’t realize at the time was the man wasn’t only curious — he was wealthy. That man was Glen Kizer, who Woods recognized as a frequent attendee of his art events.

“Well, how about I buy the building and give you the keys?” Kiz-

Just over two years

Woods and Kizer — then-president of the Foundation for Environmental Education — founded the Streetarts organization dedicated to curating multidisciplinary events — span-

— with a focus on Columbus-based, original and historically excluded

the gallery has focused on preserving Columbus’ culture, which inspired him to create the “Black Columbus

Then came Kizer. And once “Holler” ended, the work began. Kizer said he and Woods spent weeks exploring different spaces throughout Columbus.

“I ended up driving by that spot on East Main,” Kizer said. “The area had -

ue should be in that area that, at one time, Blacks were required to live there and now they were being kicked out. I went through it and it needed a lot of work, but it just felt right.”

Kizer said the space was previously a salon, with sinks that had to be removed in every room, a bathroom near the entrance that needed to be relocated, a front porch that had to be delapsing roof and frozen, cracked pipes — but despite the challenges, the work would be worth it.

-

ing the founding principles that would shape Streetlight Guild — most notably, crafting its mission statement.

“The mission of Streetlight Guild isbus-based culture with an emphasis on marginalized voices,” Woods said.

“What that means in practice is that we do events, we host artists, we do poetry readings, we do book releases, we do workshops, we do pretty much anything that you can consider culturally. And we do all of that in this space.”

Woods said he always knew a commitment to creative freedom was essential to the guild’s core values, making it a foundational principle from the very beginning.

“I don’t really put any parameters our space,” Woods said. “I will let you do anything — I will let you paint the walls; I will let you bring in furniture; I will let you do whatever you need to realize the vision for your art. I want artists, and musicians, and poets and whoever, I want them to bring the free-est version of themselves into this space.”

2017 art-exchange event hosted by the Columbus Cultural Arts Center. At the event, a group of artists was selected to create pieces, while a group of po -

and other

ets was assigned to choose a piece and write an acrostic poem inspired by it. Woods, a poet at the event, chose Lawson’s piece.

“And then we didn’t talk to each other for years after that,” Woods said. “Unbeknownst to me, she had been that I had been doing and wasn’t really making herself known, so I didn’t notice her. Finally, she came to the open mics I had been doing at Kafe Kerouac,

GUILD continues on Page 11