li n ge r i ng me d u s a t he

linger (verb)

: to stay behind, tarry, loiter on one’s way; to stay on or hang about in a place beyond the proper or usual time

Sometimes medusas aren’t laughing: sometimes we’re lingering. Moments lodge themselves deep in the crevices of our brains, nostalgia snuggled between the muscle memories of riding a bike and making friendship bracelets. We search this comfort out like a bloodhound, nose to the horizon snuffling out a whiff of home. Loitering is a form of appreciating, enraptured by the scene, knuckles white, don’t take me away just yet. We linger in the warmth of relationships, the weightlessness of youth, the energy of nature. Lingering forms feelings of home that we aren’t quite ready to tear ourselves away from yet.

If something in this world causes you to linger, pick up a pen and submit to our zine next year. In the meantime, submit your polished literary fiction, poetry, and art to The Laughing Medusa—our 2023 spring publication—by emailing bclaughingmedusa@gmail.com.

cover art: Her by Maddi Condon (she/her)

The heat from her stomps scorch the house, Rousing Mediator Father from his respite. He’ll put her out with water first, Before needing to smother me with a blanket. Good, don’t interrupt my recuperating time, I’m gracefully licking wounds, soldiering forth, Making lunch, strong and persevering. I put on the bravest face I can muster. He doesn’t check for cuts and bruises though I offer them up. But instead searches my eyes for any lingering veracity, He asks if I like my mother.

Not love, like.

Like her being, her presence

Like her as human, her as woman

Lillian Smith (she/her)I remember pushing my thumbs into the dull points of my canines and wishing I was dangerous. I daydreamed of violence like a pilot dreams of letting the nose of his plane kiss the ground, or a tourist at the top of the Empire State Building dreams of jumping.

My rage was nothing like an animal, alive and bleeding, and more like a cockroach crushed underfoot yet somehow still kicking. I could spend the day in silence, sitting in one class then another, hiding my fear with indifference, my anxiety with apathy. I wanted to understand everything and be understood by no one. I wanted to experience the fall without the bruises and scraped knees and breathlessness. I remember thinking the world owed me something and not the other way around, that I would go out and take it with my two empty hands.

Rachel Ruggera (she/her)

I thought the burning world would be louder, but then again the flames are far away. Here in my dad’s old garden it is just ash and quiet. Only the schick of the hand shovel sinking into soil, the soft fwumpumpump of clumps rolling off. I should have pulled the weeds first. I thought it would be easy to just dig them up with the dirt, get rid of everything all at once, but dandelion roots are surprisingly thick. Next to my growing hole is where we buried George-the-hamster. Or maybe it was Moose – one was eaten by the cat but I can’t remember which. Next to that is cousin Joey’s big toe. The doctor didn’t care when Joey begged to bring it home, but we ran out of ideas for what to do with the little chunk of flesh. So the hamster is marked by a rosemary bush, too stubborn to let me kill it, and the toe by a big rock, the same one that sliced it off. Dad had wanted to smash the rock into oblivion because of safety reasons and because you can never have too much gravel, but Joey had cried and cried until Dad promised the rock he would leave it untouched.

Christy’s eyes are on my bent-over bottom, I can feel them. Even through the smoke and the kitchen-window glass. She said, “Are you crazy? Don’t be crazy. You’re in no shape right now. Besides, no one is supposed to go outside. It’s bad for you.” So I listened and put on one of Dad’s old masks first. It’s the kind that looks a little like those pictures from one of the World Wars, maybe both, the same mask Dad used when he was working with wood or shaving metal or doing something else in the garage that made him a man.

When I insisted on doing it at home, in the garage, in my studio, Christy made her fussy baby look she never quite outgrew, not even after she took her bedside-manners class. She said that being this far along, I should be monitored at the clinic, with more staff than just her and her lowly RN title. I told her it was not lowly, that I trusted her to feed me the pills every thirty minutes. Maybe a painkiller too now and again. Mutterings of “bad idea” and “malpractice” continued, but it became a comforting drone like white noise or a long prayer. Christy checked my pulse, piled blankets on my body because the smoke blocked out all warmth, held my hand and stroked my hair the same way I did for her at night when we were kids because she has always been bad at sleeping. Afterwards, she whisked everything away and cleaned the leftover mess while I was in the shower. So I didn’t have to see anything more than necessary, she said. But the concrete floor of the garage is already covered in paint, some of it accidental and some of it on purpose, so what’s a little

extra red, I think.

I didn’t want to do it on my bed because there are already enough monsters underneath, so I borrowed an inflatable mattress from the neighbors. The Woods were too polite to ask why, but we still paid mind to their distress that did not exist and covered the mattress with a plastic sheet. I was cold the whole almost-six-hours, especially my toes, but my skin slicked with sweat wherever plastic touched it. I thought I might just shoot off. But it wasn’t slippery; it stuck to my body like a sticky shell, crinkling so noisily with every little wiggle that I could pretend I didn’t hear Christy ask, “Are you okay? How are you feeling? Do you need anything?” It was strange for her to be the caregiver. People often ask if we are sisters and I think of her as my little cousin but really she is my aunt. This happens in families of thirteen children. My grandmother, my father and Christy’s mother, was pregnant for nearly twenty years straight. Now I understand why she was so mean by the time she died.

The smoke stings my eyes a bit. That’s why I’m teary. And even this fancy war mask can’t keep the smell of it out. Why is wildfire smoke so awful when campfire is so lovely? Like sniffing sparks into my nostrils that light me up from within, a human glow stick. But this wildfire stuff creeping under doors, seeping through even double-paned windows –it’s sickly, head-achingly sweet. The smell comes first and lingers last. It arrives before the daylight dyes orange and shadows sharpen and the sun turns red; it stays long after the smoke and ash. Although I’ve only learned this in the last few years because the world wasn’t really burning before.

Next to me is a bunched-up growbag; on my other side is a little shrub in a black plastic pot. I wanted a bell pepper plant because Christy said it would be about the size of a bell pepper assuming I really was eighteen weeks, and I had to be because there hadn’t been anyone since Paul. But at the gardening place yesterday, the petunias, the few that were blooming, stopped me not too far from the entrance.

Petunia was my father’s middle name. I had always thought it Peter because he had always said it was Peter. It was only on his death certificate I learned otherwise, discovered that my grandmother had had a peculiar sense of humor before she got too cranky to have any at all.

A lady in a green employee shirt came over, said she had seen me there for the last five minutes and that petunias were a wonderful annual. I asked what annual meant, although my head was stuck on, I’ve been standing here for ten. Oh, she said, do we have a gardening novice?

The garden was my dad’s. I’ve just mowed the grass since he died. Oh. I’m sorry for your loss.

It’s fine.

Perhaps a perennial would be a better fit. They bloom every year. Sure, I said. I didn’t mention bell peppers.

I’m fond of this butterfly bush myself. It’s good for our zone, and it attracts butterflies and hummingbirds.

I didn’t bother to ask what she meant by a zone. I just said, That sounds nice. Because it did. It does.

Digging my hole, there are shooting pains in my abdomen. Christy might have been right – I should have waited. I should have just put the growbag into the freezer next to the ice cream like that is a perfectly normal thing to do. Christy wouldn’t have said anything. She always let me boss her around, although she held out a surprisingly long time when I said “no clinic.” There would have been screamers because there always are. They would have spittled into my face about burning in Hell. And Christy knew as well as me that I would have spittle-screamed back, “Look at the sky! We are all of us burning in Hell already!” Maybe Christy was tired of my shit, even my hypothetical shit, and that’s why she caved. Or maybe she felt bad about pushing a test between my legs last week. Just to be sure, she had said. But I knew the weight gain was only depression, the missed periods were stress, the gut cramps IBS, the nausea poor diet and saccharin-y smoke. I knew that was all it was.

During the worst of, right at the end, I squeezed Christy’s hand and stared at one very blue painting propped against the wall. The painting isn’t done but I will never work on it again, so I suppose that makes it finished. I started it after Mexico with Paul. I wanted to swim down through the shades of aqua again, down to where it was quiet but a different kind of quiet than here in the smoke. Peaceful and cool but not dead. Down there I waved my hands at the sky, said goodbye to the waves where Paul’s legs were kicking. I walked on the ocean floor, kicked up sand in soft plumes, float-hopped from rock to rock. Alone and with little bubbles floating from my lips.

But a pink plus is like a buoy no one asked for. I could no longer make myself heavy enough to sink through the acrylic depths, no matter how hard I waved. Up in the furious waves, my body tumbled violently with everything I could do and couldn’t do, everything I wanted and didn’t want, anyone I should tell, everyone I didn’t have to, how I should decide, what was best for me, why this had to be so, so hard. Crashing against my head too were the three words I never announced to Paul. We had been so shaky for so long; Mexico was a last effort. No – it was a preplanned trip that neither of us wanted to lose money on, so we said it was a last effort when actually it was a last hurrah. So I decided to decide

on my own. And I decided this decision because I have nothing except for my dad’s old house, and no one except for Christy, and… No. Like Christy said, I don’t need to explain myself.

It was only an hour ago that the bell pepper slipped out of me (although “slip” seems like the wrong word, considering the pain and the effort). That was that – now it’s at the bottom of my hole. I hesitate to cover it with soil, am tempted to open the growbag and look inside at the little alien that’s half-me. But thankfully the sides of the hole and the pile of displaced earth are unstable. Everything quakes, crumbles, falls. The bundle is disappeared. It is gone. I pull the butterfly bush from its pot and shake it over the hole like I have seen neighbors do. The roots hold firm to the soil. I massage them with my bare hand to coax them into releasing.

Around the freed, unruly roots I push with my hands what’s left of the dirt pile. Pour and pat, pour and pat, like the green-shirted gardening lady said. When the bush can stand upright on its own, I lean back on my knees. I don’t bother to clap my hands before taking off my mask. Let there be dirty marks on my face, let Christy panic if she can see through the ash, but I need my face uncovered. We said words for George-ormaybe-it-was-Moose, we gave a eulogy for Joey’s toe, but nothing comes to me now. My head is silent. This is okay. No screams or waves left; no pretty words. I am okay to just sit in the quiet, burning world with quiet, burnt thoughts. I am okay because it is just me and my butterfly bush, face-to-face.

Sydney Fosnick Davis (she/her)Fairytale

Lauren Foster (she/her)

A Haiku for October

I hate Halloween

They rush to ask, “Who are you?”

How terrifying

Lillian Smith (she/her)

Lillian Smith (she/her)

Don’t Look Down Lauren Foster (she/her)

I normally hate the smell of cigarettes, but something is keeping me from leaving you and I’m not quite sure what. You lit it so delicately, draping your arm over my shoulder as you take a quick hit of the tobacco, blowing the smoke out of your mouth in a perfect ring. I drape my arm around your knee, focusing intently on the cigarette, the way your corduroy skirt rises up your leg when you sit down.

My dad used to smoke cigarettes on the porch of our old house. He’d sit on the wooden steps, like you and I, except he never had company. My mom would roll her eyes and my dog would howl – I don’t know who he stopped for.

You convinced me to throw a party last year when we were moving out. Our plastic cups made a tapping noise as the rims just barely touched and I took my first sip of a vodka-soda. It tasted terrible.

The kids in middle school used to spread rumors about us being lesbians. You always thought it was the funniest thing in the world. My mother said that she didn’t care, as long as I wasn’t one of the kids who smoked in the bathroom during lunch.

When I was seven I used to play in our backyard while our good friend Kenny would watch over me, a beer in one hand and a cigarette in another. I never liked Kenny much. He would watch me too intently, as if I were about to disappear.

Last week you asked if you could look at my math problems because you had a date with Nick and couldn’t get the homework done. I let you.

When my dad left you were the first person I called. You came to my house at an ungodly speed – I couldn’t stop thinking about how far above the speed limit you went just to get to me. I cried for hours while my mom sat alone in her room. You ran your long purple nails through my hair and down my back, and for a moment the muscles pressing against my spine and my sternum relaxed. A week later Andrew asked to me to go outside to smoke a cigarette with him. It was your birthday party, and you watched us leave. I didn’t want to smoke, so he lit up by himself. The rings he blew were sloppy, and the entire time I thought about the black satin dress and sharp eyeliner you were wearing. I had told you that you should wear the velvet emerald dress since it brought out your eyes, but you said it wasn’t slutty enough. Andrew’s mouth tasted like dirt when we kissed and my teeth felt black. Brady Luck

Her Maddi Condon (she/her)

Fountain of Youth

Fallon Jones (she/her)

Heatwave Fallon Jones (she/her)

Heatwave Fallon Jones (she/her)

The day before, I had cut my hair

Just pieces, I wanted a little something to pull out of a ponytail

Maybe fifty strands in total

The bunch easily slid down the drain

An afterthought as I was running out. When the FaceTime switched to connecting I propped up the phone poised to say hello

And with it still in my mouth

You said you liked my haircut.

Madison McDowell (she/her) MarcusWhen I was young he would always look at my things and throw them away without asking, without a shred of guilt. All the paper maché ghosts of my childhood wiped completely clean by my ever-organizing father. There’s no one quite as tidy as my father. A well-oiled machine that always obsesses over the beauty of being clean and compulsively throws everything away as is he is haunted by mischievous ghosts who compel him to do nothing but shred.

His favorite thing to do is shred paper. At night I would hear my father

in his office murdering the ghosts of taxes and paperwork, always shredding the entire night away and I wonder who taught him to be clean.

I think what my father is must be beyond clean. And how is there so much to shred anyway, if he’s forever giving his whole life away scrubbing the sins of his father who never let him have things, always moving, in every new house he was just a guest.

In a newly built house there are never ghosts, yet my father was always trying to cleanse our home that has stayed forever and always meticulous and perfect, no shred of clutter or dust because my father never truly stopped putting away.

I wonder what he does when we all go away and he is alone with no one but his ghosts. I wonder if he thinks of his father with a mournful sigh. But no – he cleans my room, the foyer, finds things to shred hearing that whirling mechanical noise as always.

When I come home my father comments on how much I weigh, aghast at my thin frame as if he wasn’t the one who always taught me that to be clean was to find ways to shed.

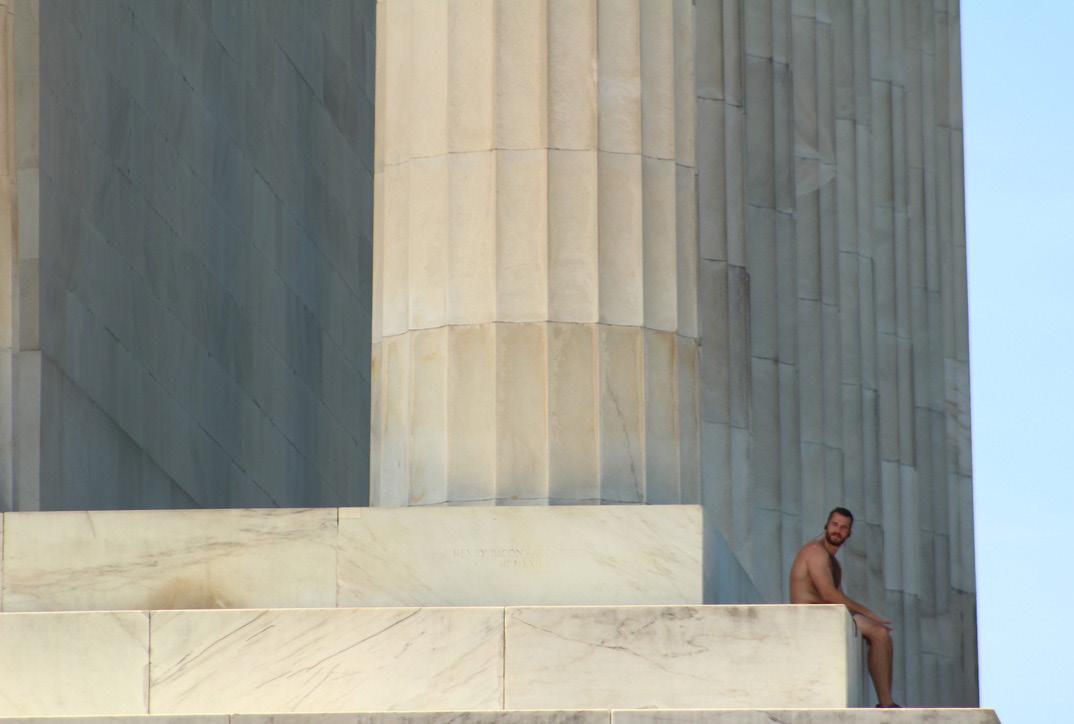

Naked Man

Fallon Jones (she/her)

Naked Man

Fallon Jones (she/her)

Woe to Mother!

Mother has made a wretch of me!

I feel the thousand daggers of hunger pierce my tender, tufted flesh. And it is Mother who drives them so!

Jail to Mother!

St. Miette I beseech thee! Deliver me from this loathsome existence to a promised land. For Mother has denied me!

Hark! Mother awakens!

She arises like first dawn over distant horizons!

Lo! Mother provides! Her benevolent love knows no bounds!

Eleanor Forestell (she/her)The last I saw the light of day, My eyes were struck with fear–The sky above, a brilliant hue Of fiery, orange smears.

I thought myself a man of steel, A bearer of the flag: The flame inside my heart was truth–My name reduced to tags.

And now, the world before my eyes, A grey and empty tomb–“Hello?” a voice calls out to me, But I do not respond.

The man without a face, just eyes; He calls himself the mud–

The roots of trees we walk upon: The veins that pump his blood.

“I want to leave.” I tell the mud, But he stares at the ground. He shakes his head and sheds a tear, But doesn’t make a sound.

The room still cavernous and dark, I wept. And gave up hope–Placed upon my shoulder I feel A cool and earthy paw.

By now the worms have set up shop, tunneling through our skin. The grubs and critters crawl about; A new life born within

In darkness I can feel his warmth, My livelihood now gone–We share our arms and legs and mind And things to which we’re drawn.

The truths that I once held, defunct, My name but rusted crud–It doesn’t have much use to me; I call myself the mud.

Lauren Foster (she/her)

Lauren Foster (she/her)

Fifty-five people in this classroom

But somehow my name out of your mouth

Feels so imminent.

Chin touches chest.

If I can just get low enough

I’ll squirm into the crevice between desk and time.

If my spine will just form a perfect convex

You’ll feel enough pity to spare me

From the icy stares of classmates

From the burn of a constricting throat.

As I yearn for space from you

My vertebrae gain distance from themselves. My face forms a parallel

With the panicked rushed black ink scrawl.

Now in addition to my grade, I fear

Developing scoliosis.

Lillian Smith (she/her)recovery never matters your sickness is a death sentence in the eyes around you you lick from the hand that feeds and ask for more plumping yourself up to free them of their pain but they will always remember you for your worst slumped over in a desk chair lips permanently shut and etched into a frown they move to wrap their arms around you in the partial feign of love to remember how much the circle is shrinking feeling your heart beat from its jail of a ribcage they hand you off at the doctor’s office parallel to the babysitters of the past but when they retrieved you back then it was all smiles and kisses now it’s exasperated sighs and wrinkled foreheads never understanding how the number on the scale continues to be a mystery for the both of you you try to swallow the still-growing sadness with every 20mg blue little pill hiding the prescription in your bedroom drawers then fade into the kitchen cabinets making sure their eyes are on your plate

Lauren Foster (she/her)

My Father would open boxes with the jagged edge of his keys the tinny rattle of them on his keychain (one to our front door the other to grandpa’s house) the dull copper scent it would leave behind on his fingers that he would smell when he lifted a glass of ice water to his lips or wiped the sweat from his temples that old penny smell would make his nose wrinkle and remind him of the loose change jangling around in his pockets taking up space and weighing him down his whole life

Rachel Ruggera (she/her)

Rachel Ruggera (she/her)

“You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and she’s laughing.”

Hélène Cixous