£5.95

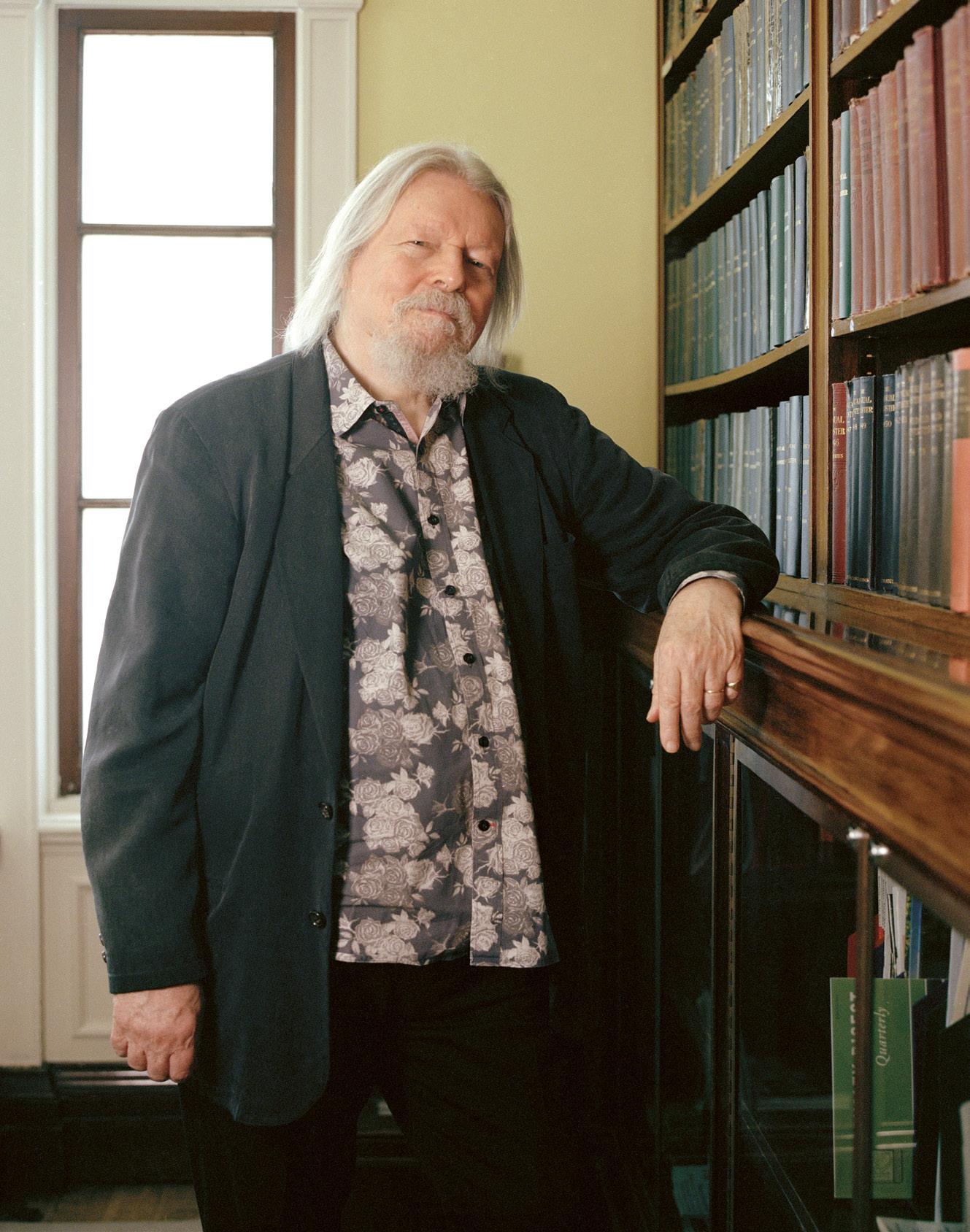

CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON

October 2023

Nº 56

Will Harris Selina Mills

D. Welcome from the Director 5 D. News 6 Annual General Meeting The Chair of Trustees steps down Improvements to the Library A new Director of Development The 2023 Library Christmas card The collection needs you D. From the Archive 11 D. Collection Story 12 D. Corner of the Library 15

F. The loneliest books in the Library 16 Lesser-borrowed titles in the spotlight F. Play on words 22 Translation and adaptation drive writer and director Christopher Hampton F. A different trail 32 Selena Mills is reframing ideas about blindness in a new memoir F. Sound and sense 38 The poet Will Harris on his love of language and working in care LAST WORDS L. Events 46 Orlando at 95 and seasonal parties L. Annual report 47 Reviewing the Library’s finances L. Meet a member 50 Writer Elle Machray revisits the 1770s CONTENTS 38 15

DISPATCHES

FEATURES

‘An exhilarating gallop across the landscape of recent English-language fiction’ Sebastian

‘A brilliant, immersive tour of contemporary fiction’ Penelope Lively Find

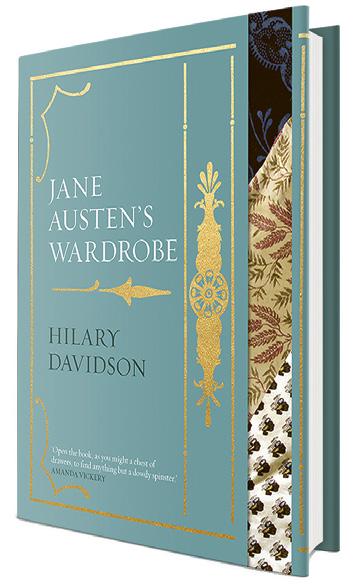

‘An intriguing and wholly original approach to Jane Austen...

A most delightful book and a must for every Austen

AVAILABLE NOW

Find out more at yalebooks.co.uk

Yale

Faulks

out more at yalebooks.co.uk 2023_Aug_Kemp_Retroland_London_Library_Ad.indd 1 06/09/2023 17:15

reader.’

London Library_Half page horiztonal JAW.indd 1 09/08/2023 09:49

Claire Tomalin

FOR THE LONDON LIBRARY

Josephine Noti

Head of Marketing and Communications

Elaine Stabler

Marketing Executive, Media and Communications

Felicity Nelson

Membership Director

The London Library

14 St James’s Square

London SW1Y 4LG

(020) 7766 4700

magazine@londonlibrary.co.uk

EDITORIAL: CULTURESHOCK

Contributors

Rachel Potts, Alex McFadyen, Elaine Stabler

Photography

Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz (cover), Ameena Rojee

Head of Creative

Tess Savina

Art Director

Alfonso Iacurci

Designer

Ieva Misiukonytė

Production Editor

Claire Sibbick

Subeditor

Helene Chartouni

Publisher

Phil Allison

Production Manager

Nicola Vanstone

Advertising Sales

Cultureshock

(020) 7735 9263

The London Library Magazine is published by Cultureshock on behalf of The London Library

© 2023. All rights reserved. Charity No. 312175.

Cultureshock

27b Tradescant Road

London SW8 1XD

(020) 7735 9263

cultureshockmedia.co.uk

@cultureshockit

The views expressed in the pages of The London Library Magazine are not necessarily those of The London Library. The magazine does not accept responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. While every effort has been made to identify copyright holders, some omissions may occur.

ISSN 2398-4201

WELCOME

Delightful discoveries

Welcome to the autumn 2023 edition of The London Library magazine. For this issue, I was delighted to interview award-winning playwright and long-time Library member, Christopher Hampton. I hope you will enjoy hearing about his varied and illustrious writing career and his use of the Library since the 1970s. We also hear from author and member Selina Mills, who talks to us about her new memoir Life Unseen and her love for the Library, calling it a “refuge” and a “haven from competitive London”. In our final feature, Will Harris talks about his experiences of writing poetry while working in palliative care, as well as his fondness for the Science & Miscellaneous collection.

In The l oneliest b ooks in the Library, Kassia St Clair shines a light on some of the books that have escaped the attention of our readers for decades. And , on page 12, members John O’Farrell, Victoria Hislop and Royston Vince tell us about some unusual, unexpected and esoteric discoveries they have made while browsing the stacks.

As ever, the autumn issue carries our Treasurer’s review of the 2022–23 financial year (page 47 ), in which Philip Broadley shares some good news about the Library’s improving financial situation. To hear a detailed report of the year, please join us at our Annual General Meeting on 14 November this year. It will be Sir Howard Davies’ last AGM as Chair, as he comes to the end of his second four-year term. We will thank him for his commitment to the Library over the p ast eight years and welcome our new Chair, Simon Godwin. I hope to see you there. •

Philip Marshall, Director

ANNOUNCING THE NEXT ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

The Library’s 182nd Annual General Meeting (AGM) will be held in the Library and online at 6pm on Tuesday 14 November 2023.

At the AGM, Trustees are set to propose an increase to ordinary membership paid by annual direct debit, of of £20 (3.7 %) to £565 per annum, saving members £50 on the cost of membership by other methods. Fees by other payment methods will increase by £30 (5.1%), bringing it to £615. Paying by annual direct debit is mutually beneficial for members and the Library. Increases will be applicable from January 2024. A proportionate increase is proposed for all other forms of membership.

Sir Howard Davies will step down as Chair of Trustees. Simon Godwin , whose appointment as Trustee will be put to the AGM, has been appointed as Chair of the Board by the Trustees and will take up this role when Sir Howard steps down. •

FAREWELL TO SIR HOWARD DAVIES

Sir Howard Davies will step down as Chair of Trustees at the AGM this November, having completed his second four-year term in the post.

As Chair, Sir Howard led the search for our current Director, Philip Marshall, and oversaw the successful development and delivery of the Library’s strategic plan. Under Sir Howard’s supervision, the Library has moved from a precarious financial position to a sound and sustainable one; grown its membership by nearly 1,000 and successfully navigated the Covid-19 pandemic.

Sir Howard also chaired the Library’s Development Committee and has been an enthusiastic and generous supporter of our fundraising efforts in London and New York. His work has included leading the Library’s search for our former President, Sir Tim Rice, and current President, Helena Bonham Carter CBE, the first woman to be appointed to the role.

With a prominent career in finance and industry, Sir Howard has long been a leading voice for literature and the arts. From 2002–10 he was a Trustee at Tate (where he served as interim Chair 2008–09), and a member of the governing body of the Royal Academy of Music from 2004–13. In 2011 he joined the board of the Royal National Theatre. A frequent book reviewer and author, Sir Howard was Chairman of the Man Booker Prize jury in 2007. He joined the Library as a member in 1981.

Philip Marshall paid tribute to his two terms as Chair, saying: “Sir Howard has led the Board with great skill and commitment, nurturing a culture that is highly collaborative, efficient and fun all at once I am especially grateful to him for the fantastic support he has given to me and the Library team over the p ast eight years.” •

6 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Above left: The London Library Reading Room.

Photo: Ameena Rojee

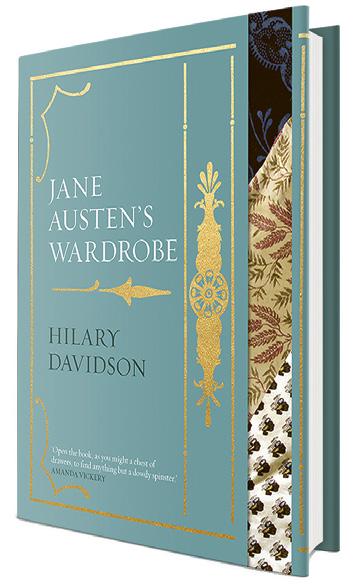

IMPROVEMENTS TO THE LIBRARY

In summer 2023, we embarked on a project to improve facilities, services and furbishing in the Issue Hall and Reading Room. A new green carpet was laid in the Issue Hall, Reading Room and on the main staircase. The colour was chosen by the Library’s interior designers to be in keeping with the building’s look and feel. The result is a calm and inspiring space that complements the room’s abundance of natural light and book-lined walls. A number of electrical improvements also mean that the extension leads have been removed and members now have access to a greater number of reliable power points.

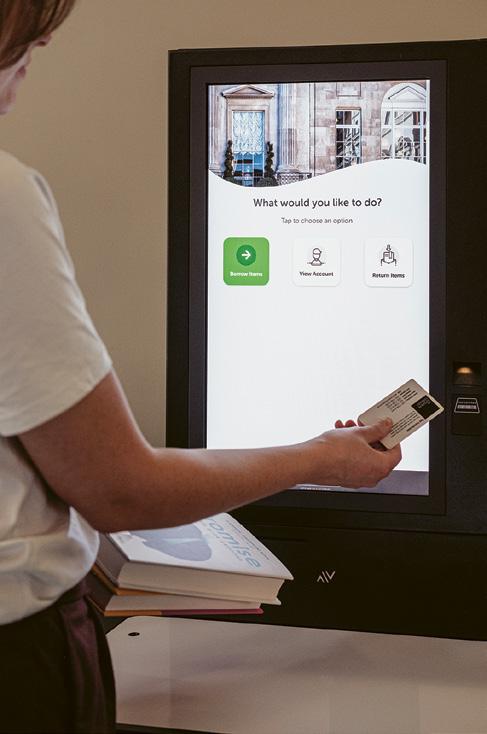

In the Issue Hall, the old enquiries desk was removed, and two self-service kiosks were installed. The kiosks give

members the option to borrow and return books quickly and easily, thus freeing up staff to assist members with more detailed collection and research enquiries.

Elsewhere in the Issue Hall, lockers were upgraded to a keyless syste m that operates using members’ cards. Two digital signs have been installed in the Issue Hall and reading room lobby, enabling us to communicate important messages with members more efficiently. •

→ The Library is committed to improving and maintaining services and facilities for members. If you would like to get in touch about any of recent improvement work, please contact feedback@londonlibrary.co.uk

7 NEWS

Above: Recent improvements include keyless lockers and self-issue kiosks. Photos: Ameena Rojee

A NEW DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT

The London Library has appointed Willa Beckett as the new Director of Development. Beckett has worked in development and project management roles in arts organisations for more than 20 years, including Art Fund, the National Gallery and, most recently, Sir John Soane’s Museum. She also spent more than two years representing the Royal Drawing School in New York, developing partnerships with art schools and funders. Beckett says: “I feel extremely fortunate to be joining The London Library as the programme and resources for its growing membership continue to develop. After spending a rewarding six years at Sir John Soane’s Museum, I look forward to being a part of the Library’s dedicated team and, through the enhancement of charitable income, supporting the work of such a respected and much-loved institution.” •

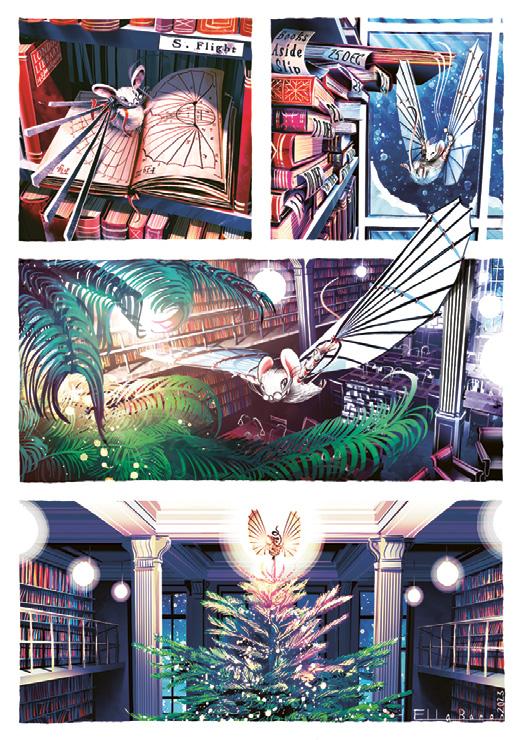

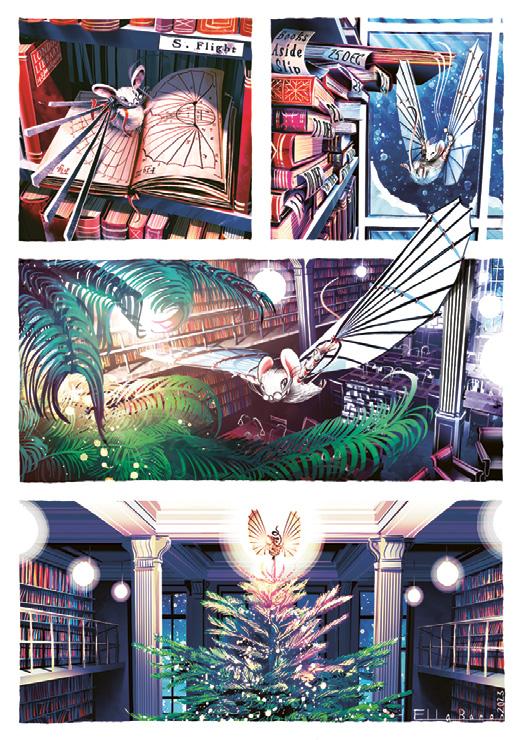

SEASONS GREETINGS

The 2023 London Library Christmas card is designed by the political cartoonist, comics artist and former London Library Emerging Writer, Ella Baron. Her cartoons are regularly published by The Guardian, The Times and The Sunday Times. She is working on her debut graphic novel, Interface, to be published by Virago, for which she is the recipient of an Arts Council England and a Society of Authors grant. Baron is also currently one of two inaugural artists in residence at Sir John Soane’s Museum. From 2017–20, Baron was staff cartoonist of The Times Literary Supplement and she illustrated Genius and Ink by Virginia Woolf and Hero by Lee Child (both Harper Collins, 2019). Solo exhibitions of Baron’s work have been held at Christie’s and the Institut Français . A selection of her field sketches drawn in South Sudan, commissioned by the charity Médecins Sans Frontières, was on display at The Cartoon Museum in London until 8 October.

A London Library Christmas card is a great way to say “s easons g reetings” to your nearest and dearest. All proceeds go towards supporting the Library. •

→ Available to order at londonlibrary.co.uk

8 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Above: The 2023 London Library Christmas card

THE COLLECTION NEEDS YOU

When T he London Library opened its doors in 1841, the collection comprised just 3,000 books. Developed over 180 years through careful thought from generations of Library staff, trustees and members, today it stands at roughly one million volumes and continues to grow by approximately 6,000 volumes a year.

Our collection is truly special. The sheer range of volumes across history, literature and more facilitates cross-disciplinary study and makes serendipitous discovery a constant delight. This year, we are raising money through our annual Library Fund to help “refresh and restore” our unique collection. Our aim is to preserve our treasured volumes and ensure their use for future Library members.

In response to member feedback, we plan to develop the art, history, and literature collections to include a contemporary diversity of voices.

Through our book-tagging project earlier this year, we were able to identify a number of lost and missing books, and several 18th-century volumes in need of

specialist repair. Donations to The Library Fund will help us to replace many of these books so they are once again available for members to borrow. Donations will also help to fund essential conservation work, such as the rebinding of books in urgent need of restoration.

By donating to this year’s Library Fund, you can help ensure our valued collection remains accessible and relevant, and directly contribute to the Library’s longterm sustainability as one the world’s leading lending libraries. Thank you for supporting your London Library.

“I have written all 12 of my history books in The London Library. The breadth and scope of the collection has proved invaluable to me as a historian. To browse the shelves and make unexpected discoveries is one of the strengths and delights of the library,” says Giles Milton, historian, London Library member and Trustee. •

→ Find out more and donate today at londonlibrary.co.uk/library-fund

9 NEWS

Above: Books in The London Library Stacks.

Photo: Ameena Rojee

by Mr Barrie & Mrs Deedee Wigmore The Huo Family Foundation Kathryn Uhde Albert Dawson Educational Trust Colour Revolution Supporters Circle BOOK NOW ashmolean.org Free for Members 21 SEPT – 18 FEB COLOUR REVOLUTION VICTORIAN ART, FASHION & DESIGN

Supported

FROM THE ARCHIVE

The Hungarian-born aristocrat with an outsize influence on pop culture

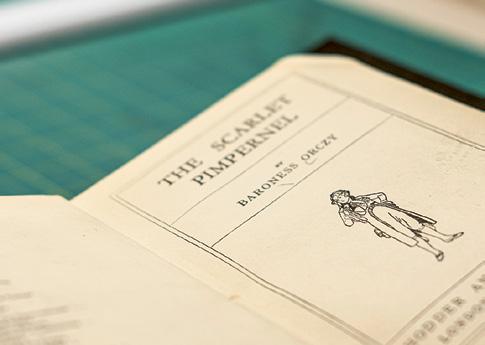

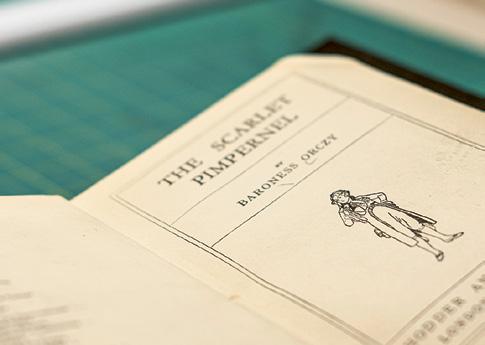

Superhero franchises are behemoths of the entertainment industry today, but there is a chapter in their collective origin story that may surprise you. British-Hungarian aristocrat and writer Baroness “Emmuska” Orczy – recently discovered to have been a Library member – helped to lay the foundations for the central character archetype.

Born in 1865 in Tarnaörs, Hungary, Orczy attended the West London School of Art in Kensington and briefly exhibited work in London’s Royal Academy of Arts before turning to writing. Her first hit came in 1905 with The Scarlet Pimpernel, a series of novels based on a play she wrote with her husband. The first book was translated into 16 languages, sparked 10 sequels, two short story collections and a handful of spin-offs.

The Pimpernel series relates the cavalier adventures of the “elusive” Sir Percy Blakeney, who saves nobles from the guillotine during the French Revolution. On the surface, he appears a wealthy fop, but this identity hides an expert swordsman, escape artist and master of disguise. Among those he inspired is Stan Lee, the Marvel Comics figurehead and co-creator of Spider-Man and The Incredible Hulk , among others. Lee said in 2018: “The Scarlet Pimpernel was the first superhero I had read about. The first character who could be called a superhero.”

Some of the devices in the Pimpernel stories were not Orczy’s inventions. The double-life narrative appears in Greek mythology (Zeus liked to shapeshift when on

earth), while Robert Louis Stevenson scored success in 1886 with Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde But others were innovative, such as the protagonist’s calling card – a note signed with a red pimpernel flower. Later echoes include Batman’s bat signal and (his nemesis) the Joker’s playing card Adaptations of The Scarlet Pimpernel include a 1934 film starring Leslie Howard and a 1999 BBC series with Richard E Grant.

Orczy’s Library membership form, which shows that she joined in 1916, was unearthed by archivist Nathalie Belkin this year. On it, Orczy lists “novelist and dramatic author” as her occupation. Prior to and during her membership she also wrote dozens of romantic novels, plays and several detective stories including Lady Molly of Scotland Yard and Unravelled Knots. The Library holds multiple copies of The Scarlet Pimpernel and several first editions of her other works. •

11

Above left: An edition of The Scarlet Pimpernel. Photo: Ameena Rojee. Above right: Baroness Orczy. Photo: Archive PL/Alamy Stock Photo

COLLECTION STORY

Library members recount their favourite tales of the unexpected from their times browsing the stacks

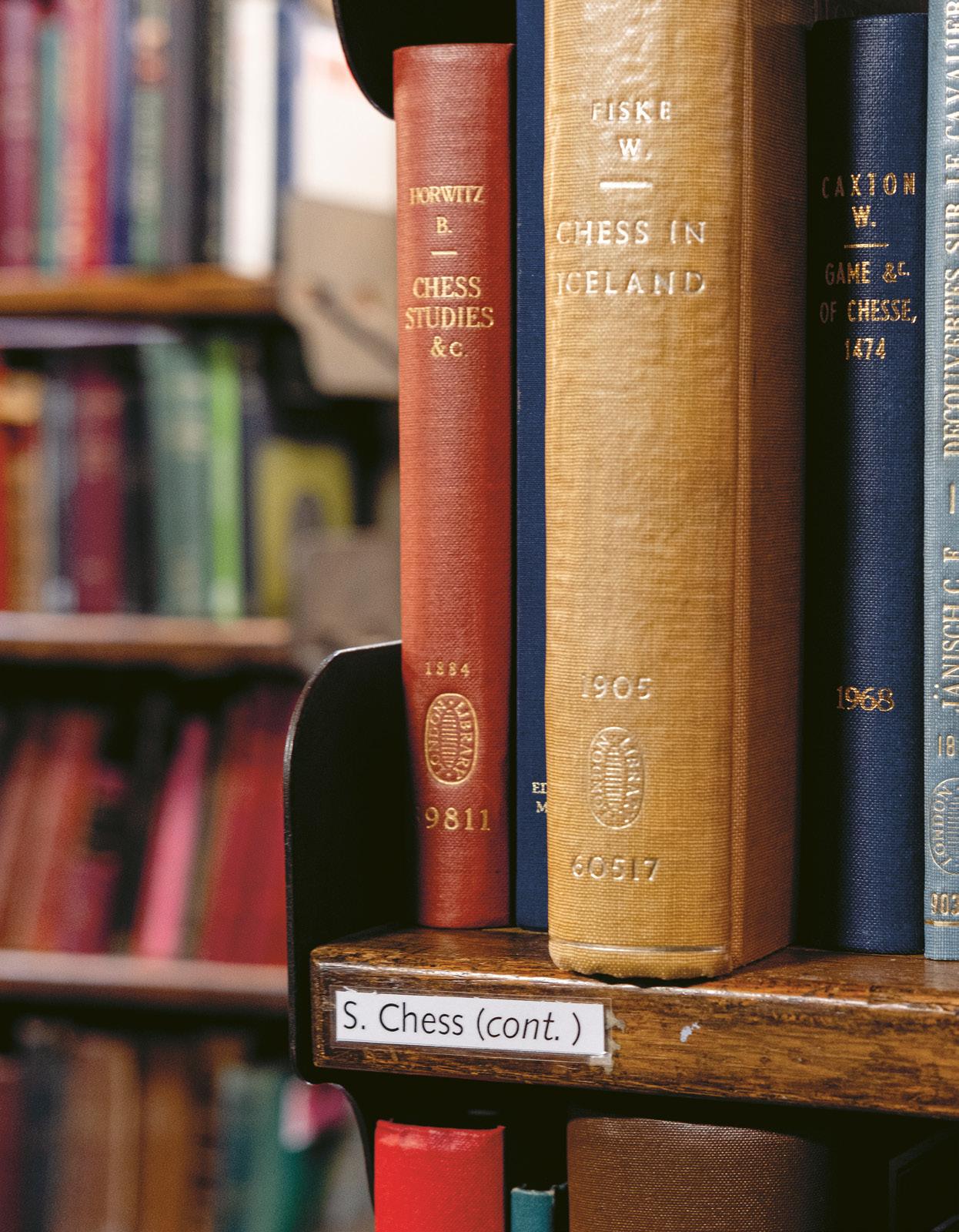

The gloriously idiosyncratic classification system at the Library, in which books are organised by subject (rather than genre), was first devised in the late 1800s – intended to be perfect for browsing. Designed by Sir Charles Hagberg Wright, Secretary and Librarian of The London Library from 1893 until his death in 1940, it has served generations of authors, researchers and readers, helping them to make serendipitous discoveries.

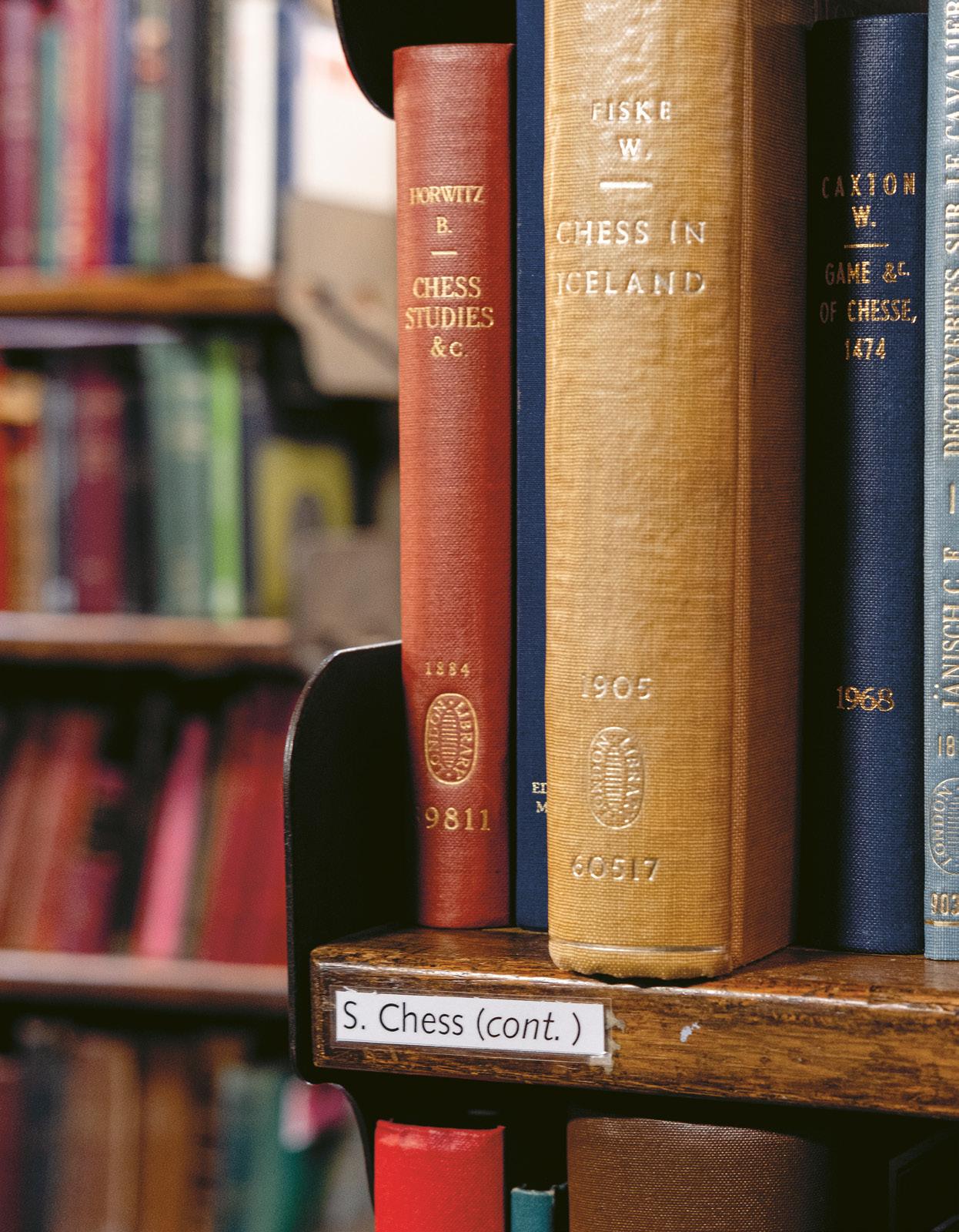

In 1972, in the midst of the Cold War, the world watched as the World Chess Championship between Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky played out in Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. Writer and London Library member Arthur Koestler was commissioned by The Sunday Times to cover the event. Koestler was no chess expert. Nor was he particularly well-versed on Iceland. He turned to the Library’s Back Stacks for inspiration. “I hesitated for a moment whether to go to ‘C’ for Chess first, or ‘I’ for Iceland,” he explains. “I chose the former because it was nearer. There were about 20 to 30 books on chess on the shelves – the first that caught my eye was a bulky volume with the title: Chess in Iceland.”

More recently, novelist and member Victoria Hislop found herself scanning the shelfmark A. Embroidery in the Art Room while writing her 2011 book The Thread, the history of a fictional Greek family in the textile industry. “I had been pondering how one of my characters in 1920s Thessaloniki put bread on the table when I came across a book titled The Byzantine Tradition in Church Embroidery. I was so inspired by the amazing craftsmanship in Greek Orthodox Church embroidery that this became my character’s craft and passion. Years later, during lockdown, I had written so much about her skill that I took it up myself and became an embroidery addict.”

Where one writer gains a new hobby, another relies on the Library’s open shelves to find a large number of stories in a short space of time. The author, comedy

scriptwriter and Library member John O’Farrell hunts for content here for his light-hearted podcast We Are History, which he co-hosts with the comedian Angela Barnes. “There is no better way of finding subjects than a stroll through Back Stacks, stumbling upon shelfmarks I never even knew existed,” says O’Farrell. “I have discovered books on the Scottish Witch Panic, the prehistoric domestication of dogs, the Great Stink of 1858 and the Opium War, the first war on drugs – when Britain was on the side of drugs.”

Royston Vince, coordinator of the Library’s Italian Reading Group and whose second novel, Demo, will be published this year, finds inspiration in the epilogues of chance discoveries. “Whenever I come to work here, I feel the palimpsest of literary voices and their characters and the multitude of fields and subjects.” In the epilogue of a book he discovered in the English Literature shelves, titled All Trivia, the author writes “across the great gulf of Time I send, with a wave of my hand, a greeting to that quaint people we call Posterity”.

Vince says: “Stumbling upon this book, I was reminded anew of a brilliant line by Gore Vidal: ‘How marvellous books are, crossing worlds and centuries, defeating ignorance and, finally, cruel time itself.’”

The value of these accidental discoveries is perhaps best summarised by the words of historian Simon Schama when interviewed in the Financial Times in 2016. Referring to the Library as a “house of words”, he said: “Isn’t the book that changes your life, or at any rate your mind, the one sitting on the library shelf next to the one you thought you wanted?” •

12 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Right: One book came in very handy in 1972. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Thank You

We are grateful to the following donors who made a generous contribution to The London Library during 2022/23, and to those who wish to remain anonymous.

Major Donors

Alain Aubry

Barnabas Brunner

Bloomsbury Publishing

John Colenutt

Eric de Bellaigue

The Clore Duffield Foundation

Drue & H J Heinz II Charitable Trust

The Garrick Charitable Trust

John & Kiendl Gordon

The International Friends of The London Library

Gretchen & James Johnson

The L E Collis Charitable Trust

Simon Lorne

P F Charitable Trust

Public funding by the National Lottery

through Arts Council England

Julia & Hans Rausing

Deborah Goodrich Royce

The Sanderson Foundation

Sarah & Hank Slack

Mark Storey

UK Founders’ Circle Patrons

£10,000 Dickens Patrons

John Colenutt · Howard Davies · Simon Godwin ·

Sebastien Paraskevas · Basil Postan · Sir Timothy Rice ·

Ms Kim Samuel, Founder, Samuel Centre for Social Connectedness · Mark Storey · Philip Winston (with matching gift from Capital Group)

£5,000 Thackeray Patrons

David & Molly Lowell Borthwick · Philip Broadley ·

Michael Cohen & Erin Bell · Eric Coutts ·

Harriet & Fabian Hielte · Andrew Hine · Simon King ·

The Bisset Trust · Peter T G Phillips

£1,500 Martineau Patrons

Eleanor Anstruther · Alain Aubry · James Bartos ·

Jenny Bourne Taylor · Nicola Braban · Sue Bradbury OBE ·

Consuelo & Anthony Brooke · Anthony Cardew ·

Nicola Coldstream · Sir John Gieve · Jakob Haesler ·

Philip Hooker · Dr Sarah Ingham · David Ireland ·

Margaret Jones · A M Keat · Humphrey Lloyd · David

Lubin · Kamalakshi Mehta · Simon Morris · Patrick

Parrinder · David Reade · Peter Rosenthal · Sir John & Lady Gwenda Scarlett · Peter Stewart · Marjorie Stimmel ·

Paul Swain · Mrs Maundy Todd · John C Walton ·

Stephen Withnell

The T S Eliot Foundation

Unwin Charitable Trust

US Founders’ Circle Patrons

Via the International Friends of The London Library

$10,000 Dickens Patrons

John & Kiendl Gordon · Simon Lorne ·

Mrs Robert Ian MacDonald · Sarah & Hank Slack

$5,000 Thackeray Patrons

Peter & Millicent Bain · Gretchen & James Johnson ·

Thomas W Keesee III · Linn & Ved Mehta RSL ·

David & Jennifer Risher · Deborah Goodrich Royce ·

Douglas Smith & Stephanie Ellis-Smith

$2,500 Martineau Patrons

Elizabeth Belfer · Wilson Braun & Mary Connolly Braun ·

J Christopher Flowers · Mrs Montague H Hackett, Jr ·

Elizabeth Bennett Herridge · Carey Adina Karmel ·

Michael T & Helen B Kiesel · Patricia & Tom Lovejoy ·

Caroline S Nation · Sarah & David Stack ·

Gillian & Robert Steel · Susan Jaffe Tane ·

Cissy & Curt Viebranz · John Wilson

CORNER OF THE LIBRARY

Design details chart the book labels’ prestigious past

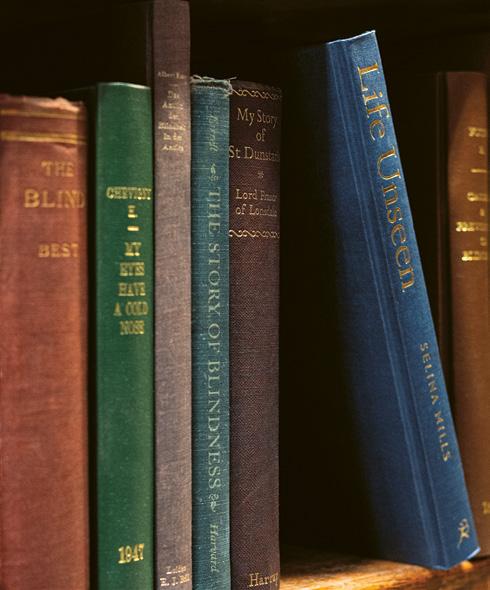

The history of stationery at The London Library is, perhaps understandably, little recorded. But some evidence exists of the evolution of the label that has been affixed to every book in the collection since the Library opened.

Few of the very first survive; one of the oldest dates from roughly 1845. The Library had just moved to its new, permanent premises, symbolised on the label by an architectural arch border. Roman numerals record the original address at 12 (not 14) St James’s Square. A much-rarer green label from the same period, when new books were in high demand, denotes a strict fortnightly borrowing period.

The Library’s primary red Victorian label was in use until 1934 when a new, oval-shaped design was created by a member of staff (name unknown), using a calligraphic font. It was employed until 1951, when the “Stone label”, its lettering drawing on antiquity, took over.

Reynolds Stone was an engraver and master letter cutter whose accomplishments include updating the clock logo for The Times in 1949, carving memorials to Winston Churchill and TS Eliot for Westminster Abbey and designing, in 1955, the coat of arms that still appears on the British passport. He created The London Library book label as we recognise it today. It was first printed in the Library’s red and green Victorian palette, though colours later varied – a peacock blue example was introduced in 1954 to acknowledge a gift of 1,400 books by Queen Mary.

A small number of labels that never made it into circulation were preserved on ‘dummy books’ as testers. They now only appear in the Library’s archives, deemed, for some unrecorded reason, as unsuitable. •

15

Assorted book labels including the oval 1930s example and a special blue edition of the “Stone label”, made for a donation of books by Queen Mary. Photo: Ameena Rojee

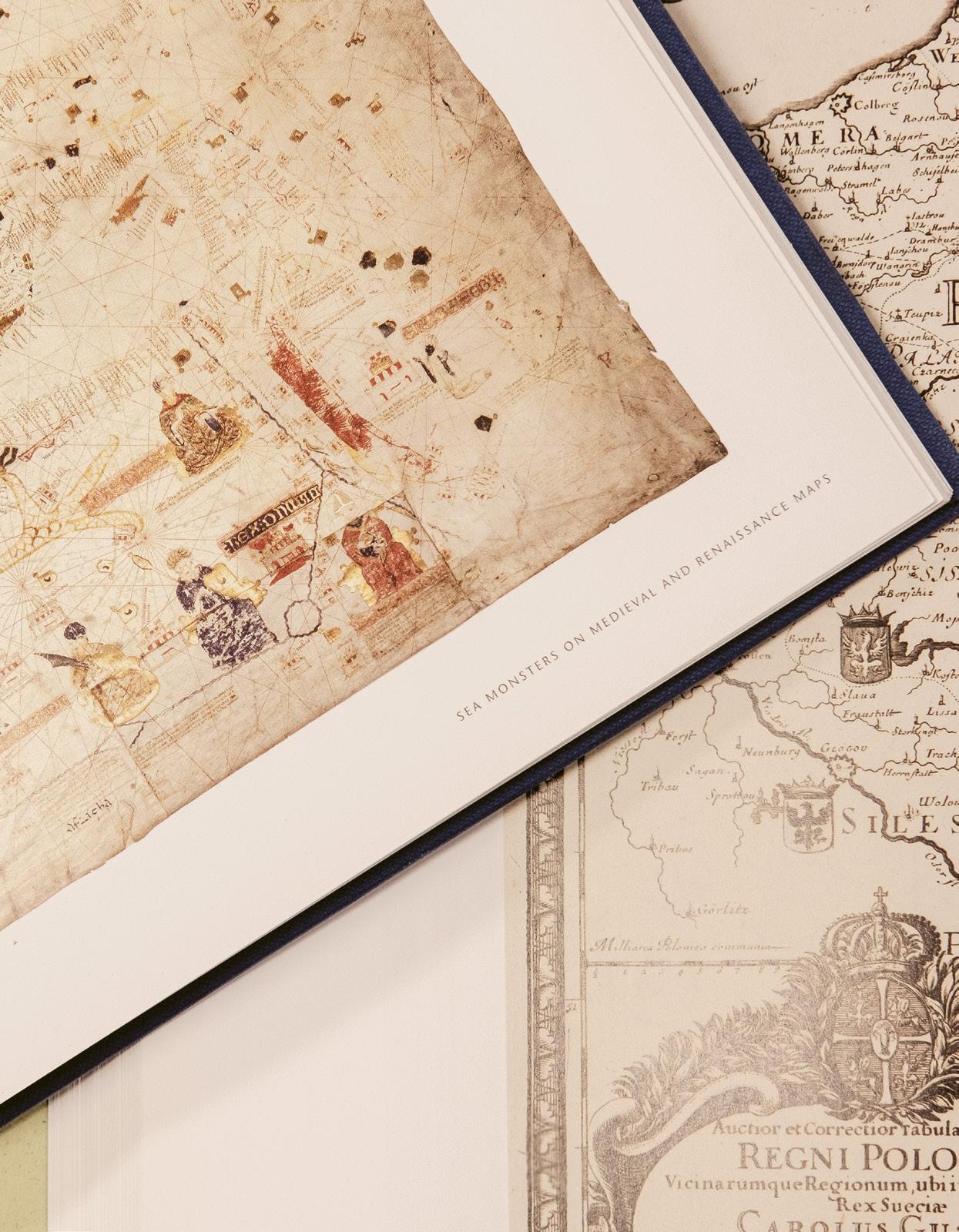

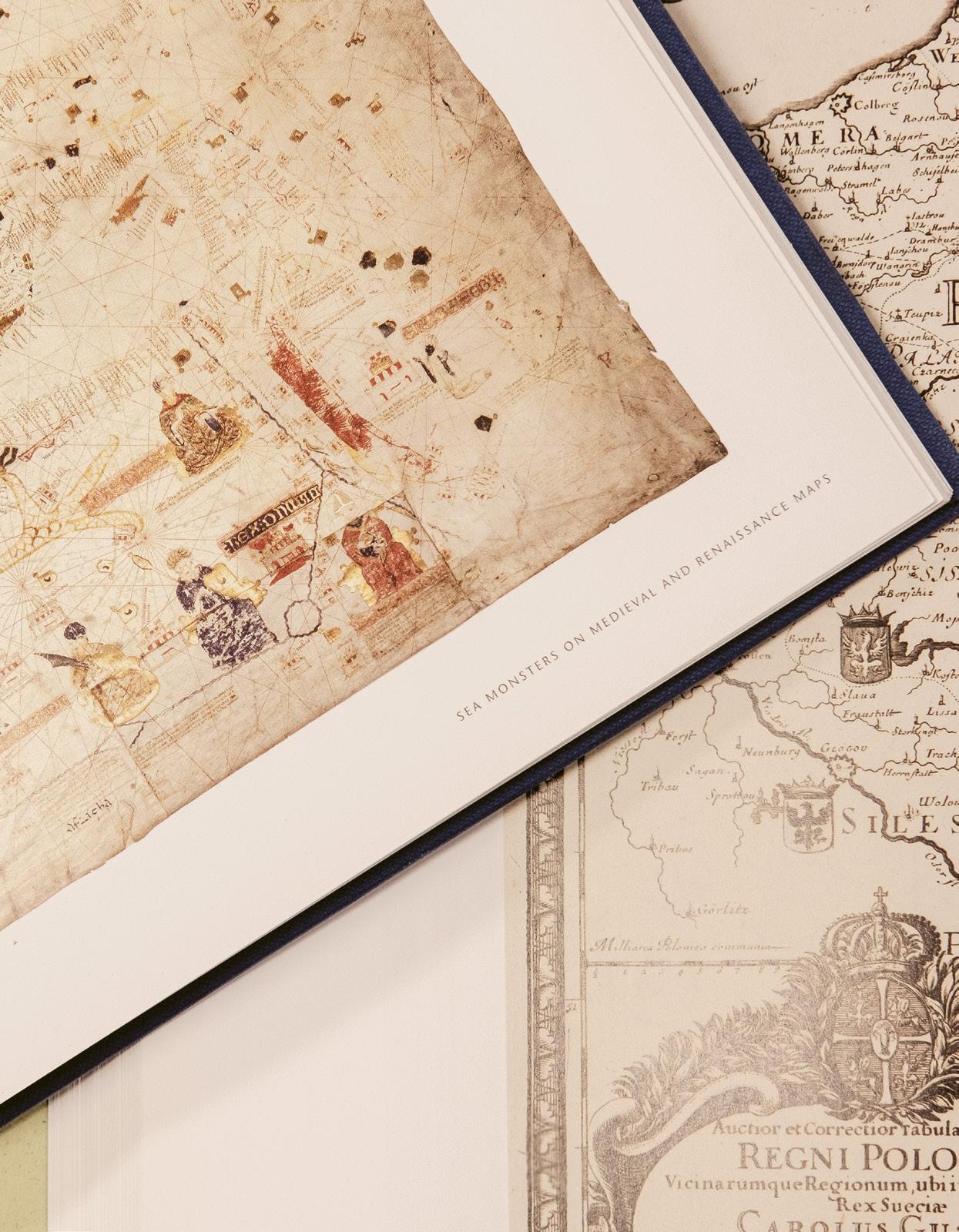

“Some maps had been separated from their parent volumes to go it alone.” The cultural historian Kassia St Clair explores the Library’s unborrowed. Photo: Ameena Rojee

“Some maps had been separated from their parent volumes to go it alone.” The cultural historian Kassia St Clair explores the Library’s unborrowed. Photo: Ameena Rojee

THE LONELIEST BOOKS

IN THE LIBRARY

Kassia St Clair goes in search of the Library’s most overlooked titles, from Siberian travelogues to the street sweepers of New York

17 §

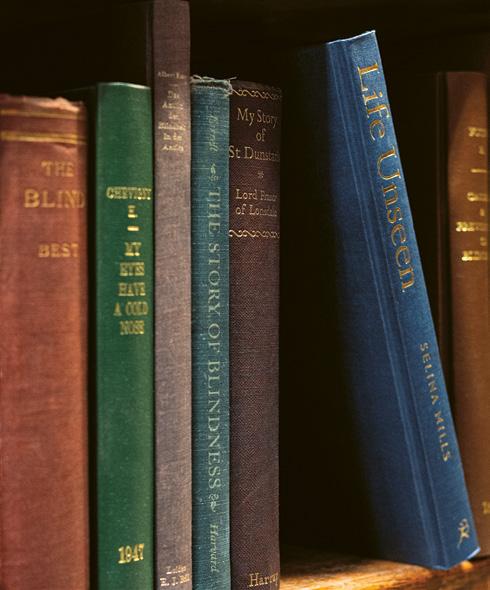

If books can be said to possess a collective character, you might imagine those at 14 St James’s Square to be a bit stuffy and self-important. The London Library was, after all, founded by Thomas Carlyle to provide a haven from the “snorers, snufflers, wheezers, spitters” and other riff-raff at the British Museum. The pedigree of its members lends heft, too. Virginia Woolf leafed through volumes here, as did Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, Angela Carter and Stanley Kubrick. But closer inspection of the Library’s collection reveals its books may be more adventurous than their stiff cloth- and leather-bound spines suggest. Curious Myths of the Middle Ages by S BaringGould, Transylvania by C Boner and W Spottiswoode’s A Tarantasse Journey Through Eastern Russia in the Autumn of 1856, for example, bore Bram Stoker’s folded corners and minute crosses in the margins while he researched Dracula During the Second World War, thousands were hurried over to the National Gallery’s crypts in wheelbarrows after a bomb hit the Library. Novelist Rose Macaulay, who joined the rescue, was allegedly held by her ankles over a gap in the masonry to reach some stray books. In all, more than 16,000 books were destroyed. Theology bore the brunt of the damage, as well as biographies of those with names starting with G to J and S to Z. Some survivors still contain shrapnel. Since then, the collection has grown to around a million items. Many are in regular demand – some have waiting lists – but others languish on the shelves. Unborrowed, their pages chastely pressed together in the dark stacks, the emotion they might feel – if they were capable – would be loneliness.

Library books get lonely for all sorts of reasons. In the case of an 1898 volume I recently consulted – StreetCleaning and the Disposal of A City’s Wastes: Methods and Results by George E Waring – the topic probably never had mass-market appeal. The issue slip – stamped inside with issue and return dates – had only been marked twice, once in June 1987 and again in September 1991. Waring’s book was, however, a gem: the true story of one man’s battle against the filth accumulating in New York, attracting pests and spreading pestilence. He includes photos of streets

THE LONDON LIBRARY

19 RUNNING HEAD

A recent audit discovered 70,000 books that have not been borrowed since barcoding was introduced around 50 years ago. Photo: Ameena Rojee

“There are many examples of intellectual fads and theories that flare brightly, before guttering and leaving a trail of well-thumbed but forlorn tomes in their wake”

piled chest-high with horse droppings, thoughts on the cleanliness of other cities, an illustration of a rubbish barge named Cinderella, and the words to a street-cleaning song:

No longer will you see a child fall helpless in the street Because some slippery peeling betrayed his trusting feet; We do what we are able to make our sidewalks neat; And we will keep right on.

Other lonely books are on topics or by authors that age out of fashion or usefulness. Guide books are generally considered perishable, as are some wonderfully idiosyncratic travellers’ tales. In 1871, Thomas Knox commissioned an author’s illustration of himself in full “Siberian costume” for Overland Through Asia. The following year Francis Wey published Rome, an imposing volume with gilt decorations, 345 delicate engravings and an introduction that begins, simply: “Gentlemen…”. Likewise, there are many examples of intellectual fads and theories that flare brightly, before guttering and leaving a trail of well-thumbed but forlorn tomes in their wake. This category includes works on phrenology by Johann Gaspar Spurzheim in French and English, and on the ideas of late 19th and early 20th-century

eugenicists, such as Karl Pearson and Francis Galton, along with several other writers shelved under S. Heredity. Then there are the books that have not been borrowed since barcoding was introduced around 50 years ago. A recent audit discovered 70,000 such items. Some had taken up residence on erroneous shelves or sections: a work of Russian literature might have emigrated to A. Painting. Thirteen maps had left their parent volumes to go it alone. These were rounded up and, miraculously, matched and reunited.

Books are admirably patient things. Barring encounters with predators like silverfish, furniture beetles and mould, or disasters involving water or – whisper it –fire, they have ample time to find new readers and perhaps be stamped and issued, before sallying forth into Mayfair and beyond. This leaves only the question of where to begin, of which lonely books to seek out first. Every member decides this for themselves. For her part, this reader plans to take a look at the novels of Rose Macaulay. •

Kassia St Clair is a writer and cultural historian. Her books include The Secret Lives of Colour and The Golden Thread

More lonely books

Titles that have been left on the shelf… for now

Switzerland by Ian Robertson, 1992

Find it in: Guide Books, Switzerland

The Basque Children in England: an account of their life at North Stoneham Camp by Yvonne Cloud, 1937

Find it in: H. Spanish Civil War

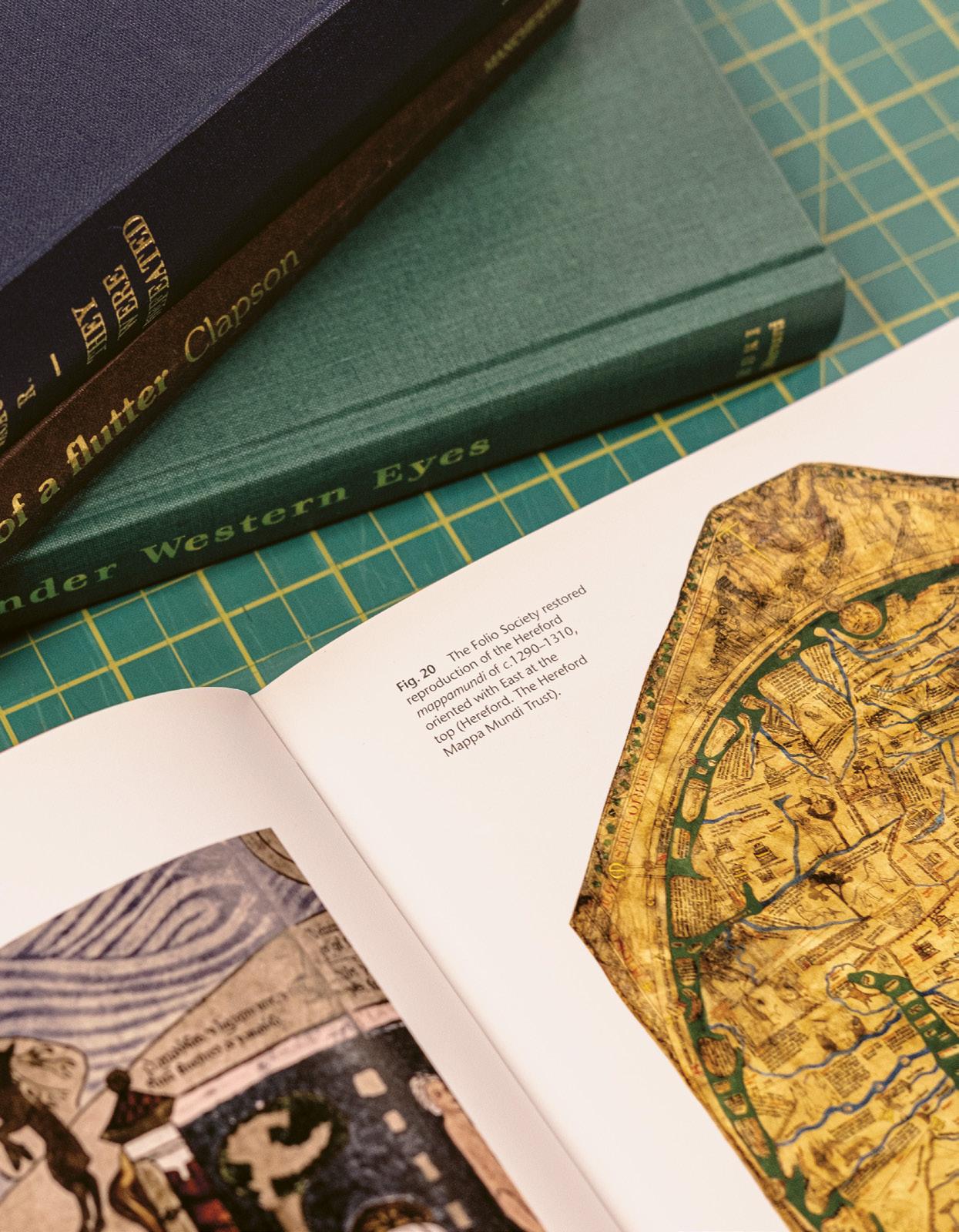

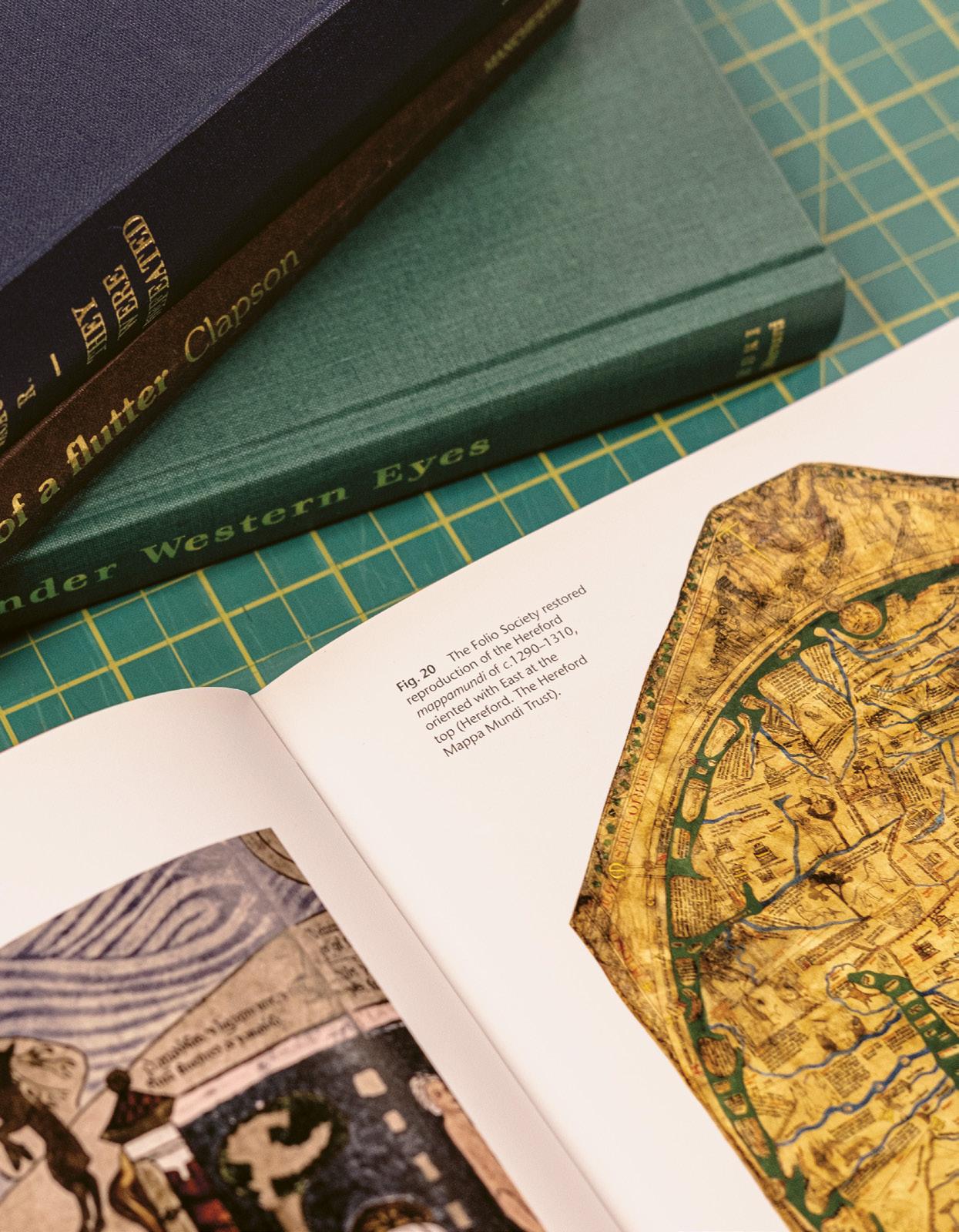

A bit of a flutter: popular gambling and English society by Mark Clapson, 1992

Find it in: S. Gaming

Forties Fashion: from siren suits to the new look by Jonathan Walford, 2008

Find it in: A. Dress

Eccentric epitaphs: gaffes from beyond the grave by Michelle Lovric, 2000

Find it in: E. Epitaphs

From the Clyde to the Jordan: narrative of a bicycle journey by Hugh Callan, 1895 Find it in: T. Europe & Gen

A Hermit disclosed by Raleigh Trevelyan, 1960

Find it in: Biog. Mason, James

The Great hound match of 1905 by Martha Wolfe, 2016

Find it in: S. Hunting

Ukraine under western eyes: the Bohdan and Neonila Krawciw Ucrainica map collection by Steven Seegel, 2011

Find it in: S. Maps, 4to

21 THE LONELIEST BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY

Left: Escapees and lonely titles. Photo: Ameena Rojee

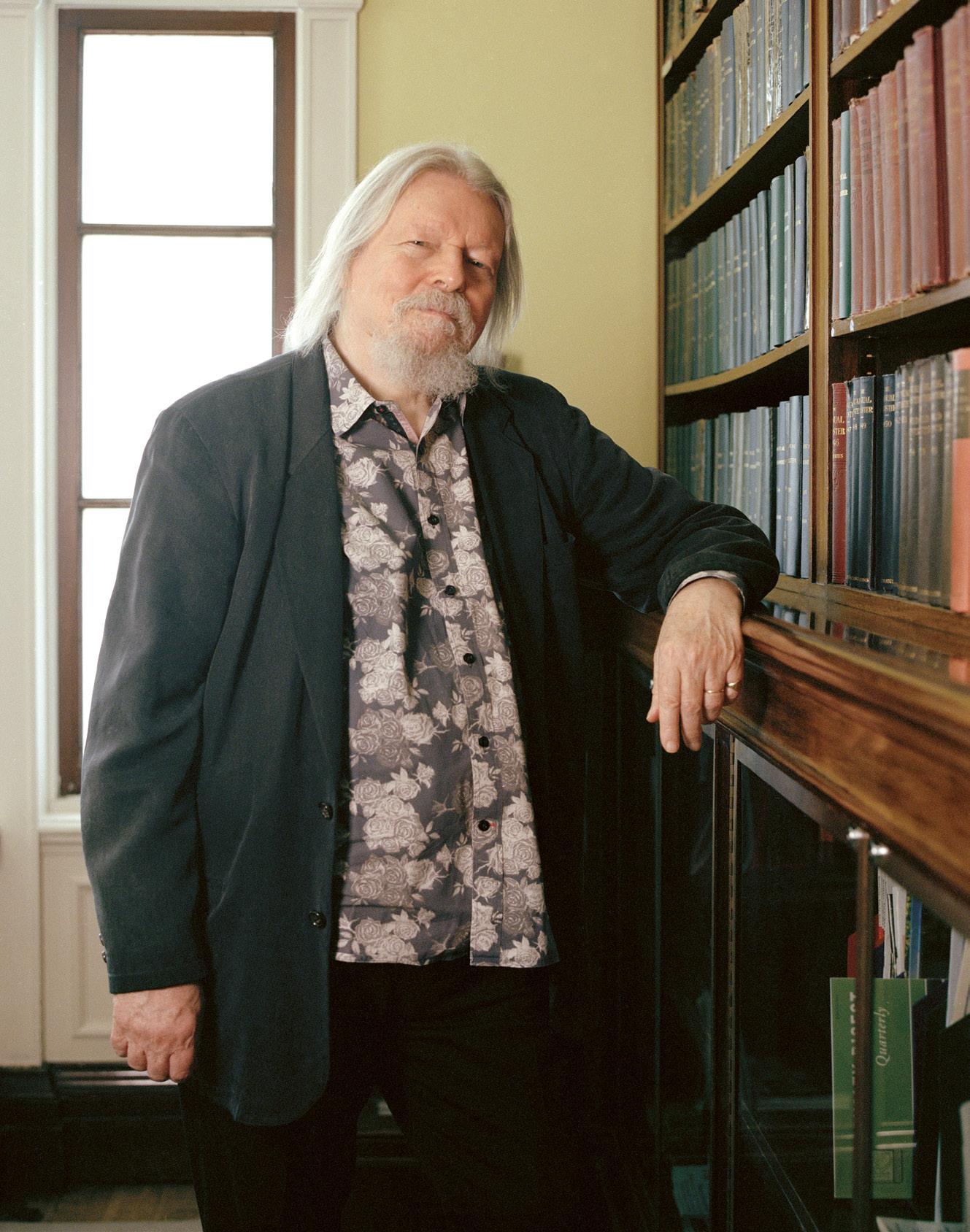

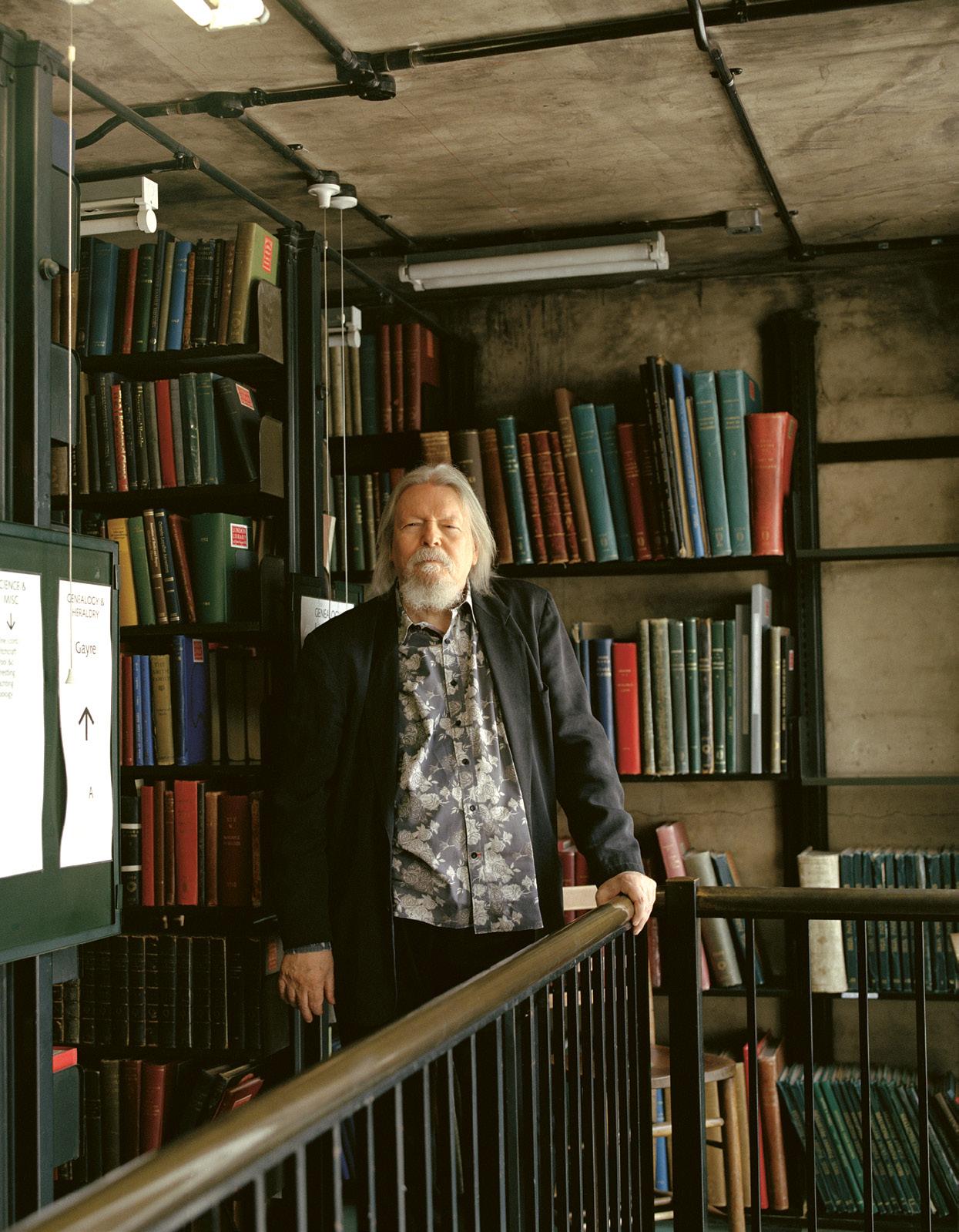

“Writing is all I ever wanted to do.” Hampton in the Library’s Study this year. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

“Writing is all I ever wanted to do.” Hampton in the Library’s Study this year. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

PLAY ON WORDS

Writer and director Christopher Hampton discusses translating classics, meeting Billy Wilder and portraying Dmitri Shostakovich

23 §

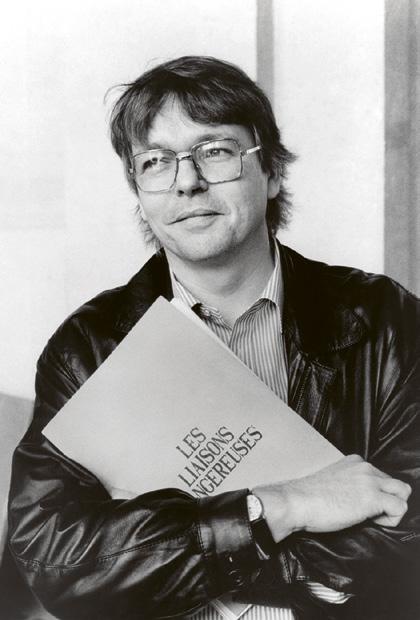

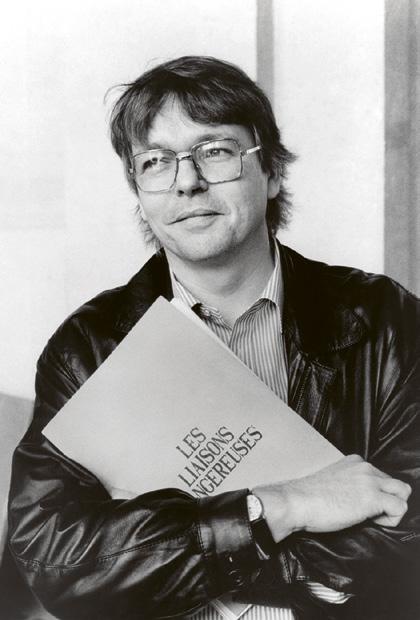

British writer and director Christopher Hampton’s career encompasses theatre, film and musicals, often adapting and translating works from the 17th and 18th centuries. His West End debut at the Comedy Theatre – now the Harold Pinter Theatre – came in 1966, at age 20, with an original play called When Did You Last See My Mother?, which told the story of a young gay man in 1960s London. Hampton was the youngest playwright ever to have a show on the West End, and was praised in The Times for his “brilliant study of the adolescent sexual outsider”. He continues to work in theatre, most recently with a musical version of Graham Greene’s The Third Man, which ran at the Menier Chocolate Factory this summer. A second success came with his play The Philanthropist, in 1970, written as a response to Moliere’s The Misanthrope. Next came Les Liaisons Dangereuses, another adaptation of a French classic – this time an epistolary novel. Alan Rickman’s performance as the predatory nobleman Le Vicomte cemented his status as a rising star, while the film adaptation took Hampton to Hollywood, where he promptly won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. Another nomination followed in 2007,

for Atonement, followed by a second win in 2020 for The Father – one of several collaborations with French writer Florian Zeller. The New York Times called the film, in which Anthony Hopkins plays a man suffering from dementia, “a majestic depiction of things falling away: people, surroundings and time itself.”

Here, Hampton talks about falling in love with translation, why he first joined The London Library and what he’s working on next.

LONDON LIBRARY Welcome back to The London Library, Christopher. In recent years, you’ve partnered with Florian Zeller on English translations of his plays The Father and The Son . When did you first begin working together?

CHRISTOPHER HAMPTON I went to see his very funny comedy The Truth in Paris around 10 years ago, which made me keep an eye out for him. The following year I saw The Father. I had dinner with Florian afterwards and said I would like to translate it. It’s been a marvellous, rejuvenating experience.

24 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Hampton in 1988, the year Dangerous

Liaisons was released.

Photo: Warner Brothers / courtesy Everett Collection

25 PLAY ON WORDS

“The cast of Les Liaisons Dangereuses was phenomenal; we had a happy summer under the radar”

Alan Rickman as the Vicomte de Valmont and Lindsey Duncan as the Marquise de Merteuil on the press night of Les Liaisons Dangereuses for the Royal Shakespeare Company, 1985. Photo: Joe Cocks Studio Collection © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

LL What was it about The Father that interested you?

CH It was just devastating. He’d got this wonderful actor, Robert Hirsch, to play the old man. I’d seen play Richard III decades ago. It was an incredibly moving performance. He was in his late 80s.

LL You collaborated on the 2020 film adaptation, winning an Academy Award for your screenplay. Tell us about that.

CH Florian hadn’t written a screenplay or directed a film before, so he asked me if I would work with him. We went through four drafts translating between English and French. He was remarkable because he only had a small budget and 25 days to make the film. It was so focused. He turned out to be such a wonderful film director. He was appointed Knight of the Legion of Honour in Paris recently, and I went to the ceremony. He’s taken a house in Los Angeles for a couple of years now – the world is his oyster.

LL Translations and adaptations are a thread running throughout your career. How did you first become interested in that aspect of playwriting?

CH In the late 1960s and early 1970s, you tended to do the published academic translation of an Anton Chekhov or a Henrik Ibsen script, and the actors would play around with it. The Royal Court decided that it would make more sense to get translations from playwrights – people who could actually write dialogue [working alongside native speakers]. They asked me to translate a play called Maria , by Isaac Babel, which was in rehearsal. I was an undergraduate at Oxford at the time [studying French and German], and it turned out that one of the two translators was a distinguished Russian don called Michael Glenny. I had to call him and say I’d been hired to improve his translation. After that I translated Uncle Vanya [by Chekhov]. It was one of the best productions I’ve ever worked on and it gave me a real taste for doing versions of the classics that I liked, and that connected with an audience.

LL It was around this time that you joined The London Library, in 1976. Did you join to work on a particular script?

CH I was translating Ghosts and The Wild Duck by Ibsen. He didn’t like his home country of Norway and lived in Munich for about 20 years, a period roughly equivalent

26 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Olivia Colman and Anthony Hopkins in The Father, 2020. Hampton adapted Florian Zeller’s play about dementia for the screen. Photo: BFA / Alamy Stock Photo

with his greatest works. So his plays would always be written in German first – he had a translator who he very closely supervised. I discovered that you have those translations here at The London Library. There wasn’t a huge demand for 19th-century German translations of Ibsen, so it was like a personal collection.

LL Did you come to the Library to write, too?

CH Yes, I liked the idea of going to work to write. Later, when I was writing films, my superstition was that the second half should be written very fast and the energy generated would somehow be visible in the finished product. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but I felt that way. I would go abroad and take a hotel room to write the second half, mostly in Paris, then Amsterdam or Italy in the 1990s. You covered a huge amount of ground that way, because otherwise you’d have to pay a large hotel bill.

LL One of your most memorable plays is also an adaptation of a novel, Les Liaisons Dangereuses. Did you know that it would be a hit?

CH In 1984 I’d done work at the National Theatre, which had gone very well, and Tartuffe for the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), but I felt slightly stagnant. Andrew Lloyd Webber invited me to work with him on The Phantom of the Opera , but I didn’t love the material, so I wrote Les Liaisons Dangereuses that year. I’d been planning it for quite a long time, but couldn’t get any theatres interested until the RSC offered me an open commission. They were not at all pleased when Liaisons came in. It turned out they had done a version called The Art of Love in the 1960s, which was what we used to call “a black polo neck job”, where the actors stood at lecterns and read the letters [from the novel] – it hadn’t generated a vast amount of enthusiasm. My version was supposed to be for the Barbican originally, but by a real stroke of luck it was demoted to The Other Place theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is tiny. It was ideal because the intensity was so palpable.

LL Was Alan Rickman [who played Le Vicomte] in it from the start?

CH Yes. He was the suggestion of my wife [Laura de Holesch]. She’s good at casting. She had seen him in [the BBC TV series] The Barchester Chronicles, and I’d seen

him playing Trigorin in The Seagull at the Royal Court Theatre. He was great. The whole cast was phenomenal; we had a happy summer under the radar. Luckily, an eccentric producer couple from Chicago bought the rights for £100,000 and stuck it on in the West End, purely because they’d seen it and loved it. It ran there for five years. The day after it opened on Broadway, we sold the film rights.

LL Were you closely involved with the making of the film?

CH Lorimar [the production company] offered for me to be an associate producer, so I could keep some control. They also accepted Stephen Frears [as director], who I wanted because he didn’t usually do period pictures. They asked us to get it out quickly, so I gave Stephen the script on 1 January. We were shooting at the end of May, and we were in the cinema before Christmas. There wasn’t time for any interference. There’s such a lot in this profession that is linked to lucky breaks.

LL How did winning your first Academy Award feel?

CH It was unexpected, and in those days it was quite casual. There wasn’t all the crazy hoopla and publicity. We travelled out on Thursday night, the ceremony was on the Sunday and we all went home on Tuesday.

LL What are you working on at the moment?

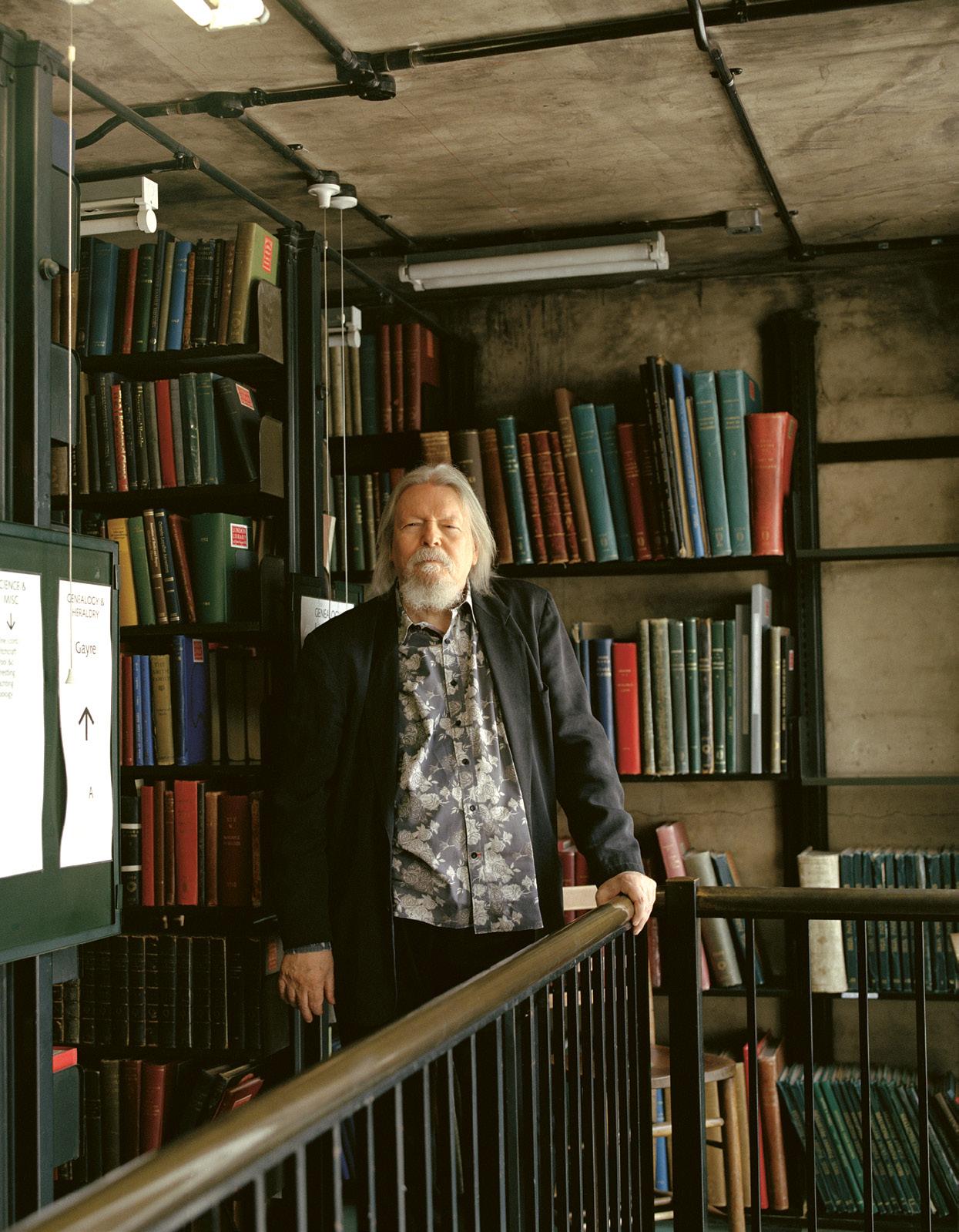

CH I’ve made a film on Shostakovich with a young Polish director who I think is very good. It’s based on Julian Barnes’ novel, The Noise of Time, which takes three moments in Shostakovich’s life – it’s a clever way of approaching the subject. Shostakovich was the only major composer who stayed in Russia after the revolution, and the novel is about how you negotiate 30 years of an oppressive regime.

LL Did you use the Library while writing it?

CH Yes, I borrowed a lot of books, mostly biographical. When you adapt a novel, you’re basically aiming to be faithful, but there are a lot of frills around the edge that you need to fill in. I’m looking for dramatic contributions to the structure. I discovered that the 25 years that Barnes’ story covered had begun with the forced withdrawal of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 4 , because it wasn’t consonant with socialist requirements. It was finally allowed to be played again around the time the last

27 PLAY ON WORDS

Hampton on the top floor of the Back Stacks. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Hampton on the top floor of the Back Stacks. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

section of Julian’s book occurs. So that gave me a linking thread between the three acts, which is very useful.

LL And you’ve now made a film about Billy Wilder, too. How did that come about?

CH It’s a loose adaptation of Jonathan Coe’s book Mr Wilder and Me, and will likely be out in 2024. I met Billy Wilder first in the early 1980s when I wrote a play called Tales from Hollywood, about German and Austrian emigres who fled Hitler. I went to LA in order to meet as many of them as possible. I thought Wilder would never agree to it, but on the contrary, he spent an entire morning talking to me about his early experiences in Hollywood. He was very amusing, it was a memorable morning. A couple of years later, I wrote to him and said I was interested in making an opera based on Sunset Boulevard He said, “You should know that by some cruel boo boo of the capitalist system, writers have no rights to screenplays, so you must address yourself to Paramount.” But he took a great interest in it, he came to a preview and gave very precise notes to Trevor Nunn, the director. He saw the opening. He said to my writing partner, Don Black, “You boys were very clever. You didn’t change anything.”

LL How do you find writing for the screen compares with writing for the stage?

CH I’ve always found writing plays gruelling. But once they’re accepted by the theatre, working with actors is one of the most enjoyable processes of all. I also really like the crossword puzzle aspect of translating.

LL Did you always want to be a writer?

CH It’s all I ever wanted to do. I’m not quite sure where it comes from, but it is marvellous and I’ve never done anything else. My mother and father were crazy about sports. I was brought up in Egypt; they were always playing tennis or yachting, while I was curled up with a book. But they didn’t discourage me. I wrote a novel when I was 16. I couldn’t get it published and then it dawned on me that the best bits were the dialogue. •

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity

→ Turn the page to read more about works adapted or translated by Christopher Hampton

29 PLAY ON WORDS

“My mother and father were always playing tennis or yachting, while I was curled up with a book”

Four works that have inspired Christopher Hampton’s writing

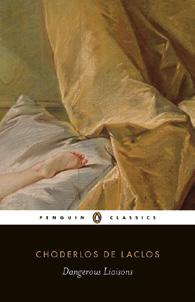

DANGEROUS LIAISONS

BY CHODERLOS DE LACLOS (1782)

Published before de Laclos fought in the French Revolution, this novel reveals the immorality of the ancien régime in the romantic machinations of its aristocratic protagonists. The epistolary format meant Christopher Hampton initially struggled to get his stage adaptation made, until it became a hit for the RSC.

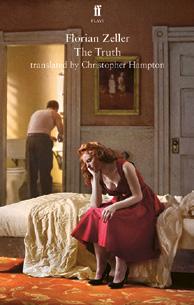

THE TRUTH

BY FLORIAN ZELLER (2011)

Hampton loved this comedy, exploring infidelity and secret knowledge, when it opened in Paris. The experience led to multiple collaborations with Zeller for stage and screen. He translated The Truth and The Father for the West End, and their Hollywood production of the latter won an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

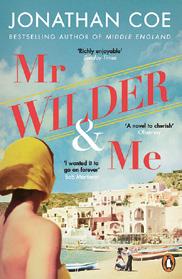

MR WILDER AND ME

BY JONATHAN COE (2020)

BY JONATHAN COE (2020)

This fictionalised account of the making of Billy Wilder’s 1978 film Fedora is told through the eyes of Calista, a Greek film composer nearing the end of her career. Hampton’s screen adaptation, slated for release some time in 2024, is “a very free version” of the novel, focusing on Wilder and the production of Fedora

THE NOISE OF TIME

BY JULIAN BARNES (2016)

Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s life is told through three real-life events in this fictionalised biography: his interrogation by secret police, his reluctant installation as a state functionary and a tour of the US. Hampton is working on a film adaptation, with his research “very much helped” by books in the Library.

30 THE LONDON LIBRARY READING LIST

A DIFFERENT TRAIL

Selina Mills dispels myths about the lived experience of blindness that stretch back to antiquity, finds Lottie Jackson

32 §

Mills, shown here in the Art Room, calls the library “a refuge and a community”.

Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Mills, shown here in the Art Room, calls the library “a refuge and a community”.

Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Ilove the smell,” muses the veteran broadcaster and author, Selina Mills. “This wonderful musty, warm and woody smell of books. And the sound of the metal stairs in the stacks.” As a longstanding member of The London Library – Mills joined when she was 24 – she has, in her words, “never left”. “It’s been a refuge, a literary community and a haven from competitive London. I am able to hear my own mind here.”

And it was here, nestled in the Library basement, that Mills worked on her recently published memoir, Life Unseen – a historical romp through the mythologies, religious tracts and literary tales that have informed, and often clouded, our perception of blindness. From Homer and John Milton to Jorge Luis Borges, Helen Keller and even Neo in The Matrix, Life Unseen stitches together the lives and legends of blind people across western culture. But, as Mills explains to me, the intention behind the book was not a nostalgia trip – far from it. At its core, Life Unseen aims to demystify sight loss, to rally against the punitive fantasies and delusions that have plagued generations of blind people. Whether sight loss is perceived as a catastrophic calamity, a state of pity or even a target for fetishisation, society still doesn’t

understand much about the spectrum of blindness. That’s despite there being 217 million people in the world who have moderate to severe vision impairment.

“It’s a very lonely experience losing your sight,” says Mills, who is legally classed as blind with 15% of her sight remaining. Having always experienced eyesight problems, Mills slowly began to lose her sight a few years ago. Now, she lives in a “blurry state of half-seeing”, able to read 26-point-size fonts on an adapted computer and using text-to-speech software to write. “I wanted to find out how others had experienced it – to give myself a map of how other people had managed sight loss. The silence over how to live a life with blindness was loud.”

When it comes to redefining how blindness is viewed, Mills is fearless and unsentimental. As she writes in the opening pages: “Why can’t blind people be, well, just non-seeing?” Her book possesses a frankness that is not only refreshing but radical among a literary tradition that is liable to typecast blind people into binary categories: either tragic or superhuman and inspirational. In 2022, Mills also co-wrote a libretto for The Paradis Files, about the life of musician and composer Maria Theresia von Paradis. Though talented and successful – her friend Mozart is thought to

34 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“

“The Library has been a refuge, a literary community and a haven from competitive London. I am able to hear my own mind here”

have written his Piano Concerto No. 18 for her to perform – von Paradis was pestered by quack doctors who claimed they could cure her blindness. “It’s important to reclaim blindness from [these] polar extremes because many visually impaired people are trapped by the stigma surrounding blindness, only understood as individuals who must be pitied, fixed or rescued from their supposed terrible fate,” says Mills with the same urgency and clarity that permeates her prose. “Sighted people project all sorts of myths onto you, and it’s hard to push back and change these perceptions. So writing the book gave me the courage to decide how I defined myself on my own terms.”

What began as a factual text evolved into something more personal and self-interrogating during the writing process. Mills recalls how she first attempted to write Life Unseen as a straight history book, but it ended up feeling “rather clumsy and heavy”. It was then that she elicited the advice of her novelist friend and fellow London Library member Mavis Cheek, who used a metaphor of pouring cheese sauce over broccoli to make the prose easier to digest. She suggested weaving together historical fact with personal revelation. At that point, Mills began to orientate her own story within its cultural context, taking inspiration from the travel diaries of writers such as Edward Lear,

35 A DIFFERENT TRAIL

Bethan Langford (centre) as the blind musician and composer Maria Theresia von Paradis in The Paradis Files , with Andee-Louise Hypolite (left) and Ella Taylor. Photo: Alastair Muir / Shutterstock

Axel Munthe and Norman Douglas. “I found that much of what fascinated me was what I needed to know for myself. It was a personal quest. I wanted to take my readers on a journey with me, rather than lecture them.” Life Unseen emerges as Mills’ very own odyssey.

“It took me a while to find my voice,” confesses Mills, who established her career as a senior reporter and broadcaster for the likes of Reuters and the BBC. Undoubtedly, memoir-writing was going to be a drastic departure from her days breaking finance news for The Telegraph, or covering a Nazi war crimes trial for the International Herald Tribune. “Journalistic writing is a much tighter form than longform fiction – you have to get to the point very quickly, report clearly and in a hierarchical order,” says Mills, while describing how she was forced to unlearn that rigidity. “What I loved about writing my memoir is that you can wander and wonder and pause and consider moments in time. It gives you the ability to take yourself on different trails; you have to relax and enjoy the ride.”

For Mills, The London Library is the ideal setting to do this. A place where, ensconced on a comfy sofa or peering out onto St James’s Square, she relishes the chance

36 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Mills’ book A Life Unseen: a story of blindness , shelved under S. Blind.

“It was a personal quest. I wanted to take my readers on a journey with me, rather than lecture them”

Photo: Ameena Rojee

to sit, read and think. “Writing a book is like solving a puzzle – working out how to construct the architecture of a sentence, feeling the rhythm, tone and cadence.” I am interested to know about her experiences with accessing the Library. As someone who is legally blind, are there logistical obstacles or additional challenges to navigate? “I relied heavily on the librarians to help me find books and periodicals – this has been crucial,” admits Mills. “The staff at the front desk are endlessly helpful, kind and efficient. The number of books they have found for me, which I did not find through my own research, made this book happen.” This included everything from Irene Metzler’s Disability in Medieval Europe to Edward Wheatley’s Stumbling Blocks Before The Blind , which is an academic history of blindness in the Middle Ages.

Having been a Library member for so many years, Mills knows the building’s layout extremely well. However, I am struck by the sense that The London Library offers something more than convenience and practicality. It is a bustling hub of intellectual stimulation and belonging. “I love bumping into other writers at the end of a working day – and nodding in appreciation of the discipline of writing,” says Mills. “I am not alone here.” •

Lottie Jackson is a writer, editor and disability activist who has contributed to publications including Elle, The Guardian, Vogue and The Telegraph. Her memoir, See Me Rolling, is out now

Mills at the Library entrance. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Mills at the Library entrance. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Harris in St James’s Square. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Harris in St James’s Square. Photo: Ameena Rojee

SOUND AND SENSE

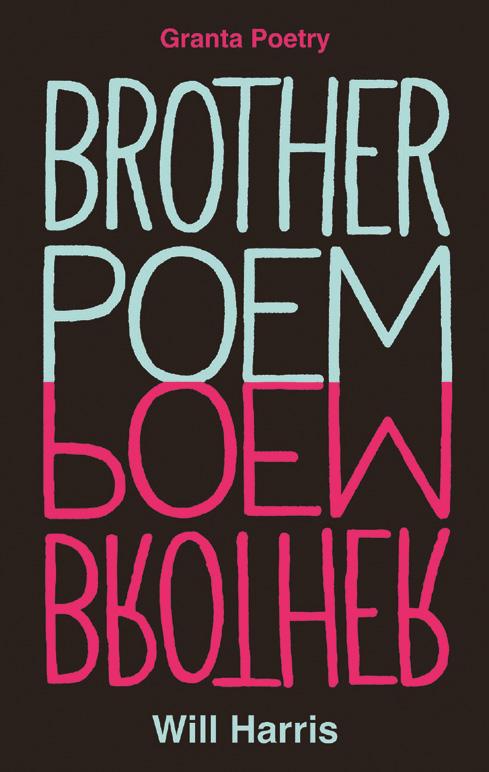

The parallels between poetry and working with the elderly are clear to Will Harris, but don’t talk to him about Philip Larkin

39 §

As a teenager, the poet Will Harris, now 43, regularly spoke to an elderly gentleman at the care home in which he volunteered. One day the man, recalling his memories of the Blitz, told Harris of a time when the Luftwaffe flew so low over London that the china in his cabinets trembled. The memory struck Harris as “dreamlike”, a sensation he’s felt many times since. He went on to volunteer for Marie Curie as part of a befriending service during the pandemic and today, alongside his writing, Harris is the activities coordinator in a Tower Hamlets care home. He pursued this work in the wake of lockdown – partly out of a desire to “be more connected with people” and partly in response to his personal reading around palliative care.

“A lot of communication, especially with people who have some form of dementia, is semi-verbal. You’re picking up on things people say and echoing it back to them and using speech in a different way. I hear the same stories, or fragments of stories, repeatedly,” he says, when we speak. Harris’ work with the elderly has not directly informed his writing so far, but he is keenly aware of the parallels. “Poetry can often simulate that effect, where there’s a haze followed by these particular moments that stick out,” he says.

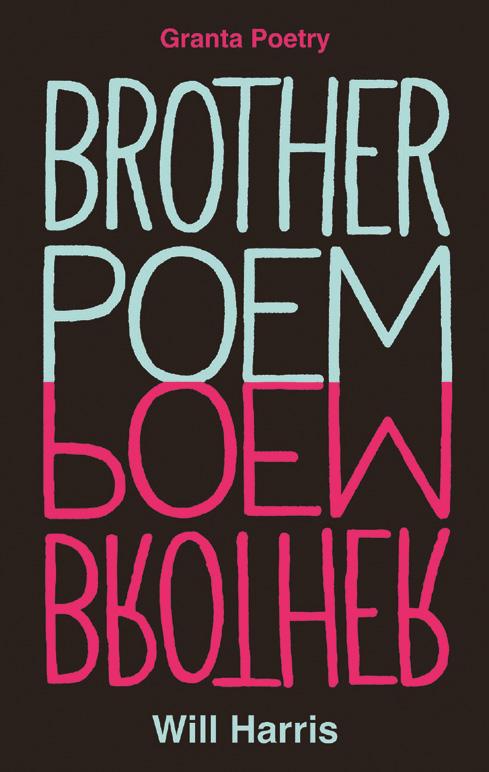

This sense of time and language – as being malleable, illusive – permeates Harris’ work. His critically acclaimed first book, Rendang, draws on his mixed Anglo-Indonesian heritage, dipping in and out of timelines and weaving together recollections in a kind of temporal patchwork. Released in 2020, it won the Forward Arts Foundation’s

40 THE LONDON LIBRARY

Harris’ latest collection “oscillates

a

around

fictional sibling”. Photo: Courtesy of Granta Poetry

In June, outrageous stood the flagons on the pavement which extended to the river where we spoke of everything except the fear that would, when habit ended, be depended on. Our fear of darkness as the fear of darkness never ending. To hell with it, you said, and why not? Let’s buy a dirty and slobbery farm in Albion. What country is this? There was the big loom we little mice were born to tarry in. Its patter made the bad things better. O we sang against the light as we sang against the battens! Cold that June and mistshapen, the river mind and all else matter, I called you. Where are you? It’s getting dark. But these being statements, they ran away before I could say hummock coastline theft. This is where we used to speak of everything. I need one more hour please. One more hour. My affordable memories sold, I hung my phone from the highest flagpole and kissed the face of England once discreetly, though it wasn’t you and neither was the mist wherefrom in dingle darkness buzzed a single notification. Call me when you get this. And see I’m calling now, whether or not this is now or in time

41 SOUND AND SENSE

The opening untitled verse in Brother Poem Reproduced by kind permission of Will Harris and Granta Poetry

Felix Dennis Prize for Best First Collection and was shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize. His second collection, Brother Poem , was released earlier this year and oscillates around a fictional sibling, whom Harris inserts into early childhood memories both real and imagined.

Harris’ own childhood was spent in west London. The son of an antiques dealer and a secretary, he discovered poetry as a teenager following the loss of his paternal grandparents. “I got scared of dying even though I was only 14. I felt like I had to do things, to learn things,” he recalls. “I got really into philosophy, then I got into novels, essays and poems. And I think it was just poetry… It was like a condensed medium, it felt clear, it felt more direct. The urge to write came from that experience of death.” During this time, Harris enjoyed experimental work by the likes of Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens and HD (Hilda Doolittle), “strange, poetic and rambling” verses from which meaning couldn’t be easily extrapolated. Writing that could have appeared on a school syllabus – “anything that was like, Philip Larkin” – immediately drew his ire.

“Poetry is often taught by people who don’t really like it, which is why they teach it for the meaning,” Harris says. “There was no one [at school] who just seemed to love language and that, to me, is what poetry is about. It’s just

immersing yourself in the arbitrary connections between sound and sense. That’s why children are amazing poets and amazing readers of poems, because they haven’t been taught that it’s something they need to understand, to unpack.”

Harris adopts this viewpoint in Brother Poem. As with Rendang, the collection distorts chronology. But rumbling tummies, felt-tip pens and childish refrains such as “mine not yours’’ are folded into the titular poem, grounding it in childhood. Adopting this perspective was a response to the pressure he felt when writing Rendang. “The expectation, as a writer of colour, that your work is about something was really paralysing,” he says. By “something” does he mean heritage and race I ask? “Yes, and it was more specifically the sense that the ‘about-ness’ couldn’t be chosen. As [the prizewinning poet] Sarah Howe puts it, ‘whatever you write, race is writing you’. I’d find myself playing these games, pre-empting readings, offering counter-readings, metanarratives, to squirm my way towards breathing space.”

“I think that’s why I wanted to focus on early childhood. Race, class, gender, sex, everything is up for grabs at that age. You don’t know what those signifiers are, but you can feel them and see them. It was a really interesting age for me to live with again, to remember a time before these things became concrete [...] I wanted to let the

42 THE LONDON LIBRARY

“There was no one at school who just seemed to love language and that, to me, is what poetry is about”

Harris has been a Library member for over a decade. His 2018 essay Mixed-Race Superman put him on the literary map. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Harris has been a Library member for over a decade. His 2018 essay Mixed-Race Superman put him on the literary map. Photo: Ameena Rojee

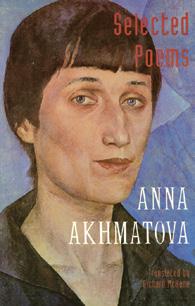

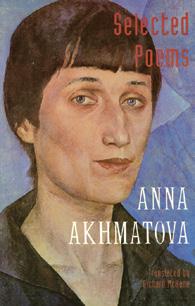

SELECTED POEMS

BY ANNA AKHMATOVA (1989)

Harris admires the “exigency of form and the moral weight of images” in this collection by the Russian poet. Her intensely personal, romantic work was declared anti-revolutionary in 1925 and banned by the Soviet state. This volume includes the full text of Requiem, a reflection on Stalin’s tyranny written over three decades from 1935.

MIDWINTER DAY

BY BERNADETTE MAYER (1999)

Told in six parts over the course of a day, this poem’s “intense focus on the minutiae of daily experience opens up a portal into the very trippy underside of reality,” says Harris. Born in Brooklyn, Mayer came to prominence in the 1960s as part of the New York School of writers and artists, who used stream-of-consciousness narration.

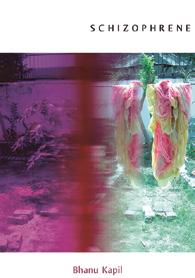

SCHIZOPHRENE

BY BHANU KAPIL (2011)

British poet Bhanu Kapil explores the legacy of South Asian colonial partition, “articulating the shock, comedy and double-vision of living between cultures,” says Harris. Her fourth book combines research into the prevalence of mental illness in diasporic Indian and Pakistani communities with first-person reflections on healing.

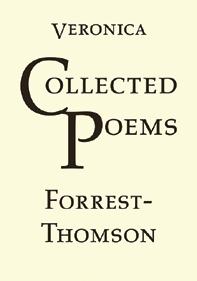

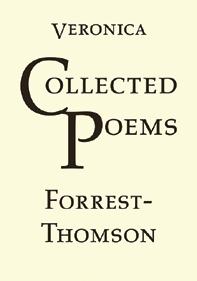

COLLECTED POEMS

BY VERONICA FORREST-THOMSON (2008)

BY VERONICA FORREST-THOMSON (2008)

Harris recommends this book “for its embrace of artifice and the thought-music that only poems make (‘An axe is not like a knife that carves a turkey’)”. The cult Scottish writer died in 1975 at the age of 27. Largely unknown during her lifetime, and in the years following her death, she’s now considered an important Postmodern poet.

44 THE LONDON LIBRARY

READING LIST

Will Harris recommends four outstanding poetry books, all at the front of his shelf as he wrote Brother Poem

resources of poetry – sound, rhythm, repetition, the things that made me love poetry as a teenager – dictate the sense.”

While the majority of Brother Poem was written at home during lockdown, Harris is a long-time member of The London Library. He was first given a membership aged 23. “I was living in Peckham at the time, five of us in a two-bedroom house, so it was pretty necessary to have that space to work,” he recalls. Later, the stacks proved essential when writing Mixed-Race Superman, the 2018 essay exploring mixed-race identity that put Harris on the literary map. It garnered praise from the likes of Inua Ellams and Rowan Hisayo Buchanan, while Raymond Antrobus said it was one of the books he gifts most frequently. Earlier this year, Harris delivered a reading at the Library’s centenary celebration of TS Eliot’s The Waste Land . He thinks the Library is a brilliant resource for young writers and is particularly fond of the Science & Miscellaneous collection in the Back Stacks, which has its own gloriously idiosyncratic classification system. “Everything is arranged thematically,” he says. “So you can go and read all the books ever written on mirrors or hypnotherapy.”

Today, Harris lives in north London with his partner of 10 years, the artist Aisha Farr. He co-facilitates the Southbank New Poets Collective, which supports up-and-coming writers from diverse backgrounds, and cites graduates Hasti, Jinhao Xie and Oluwaseun Samuel Olayiwola as writers to watch.

More projects are on the horizon; Harris is poised to judge the 2023 National Poetry Competition, whose alumni include James Berry, Carol Ann Duffy and Tony Harrison. A Monitor Books pamphlet, featuring a conversation between Harris and the poets Jay Bernard, Mary Jean Chan and Nisha Ramayya, is coming out later this year. He has more prose in the pipeline, too, mostly concerned with working in care. Harris says that experiencing the “brutality” of the sector (the government recently announced plans to cut £250m from social care workforce funding amid a chronic staffing crisis) will be reflected in his upcoming work. “What I’ve written has always been a reflection of where I’ve been at,” he explains. “I started working in care homes in September 2021. I didn’t think I was going to write ‘about’ it when I did – I’m still sceptical of writing that is ‘about’ – but maybe inevitably, it’s changed me. It’s affected how I think about stories, ownership, art, communication, family – I’m not sure how those ideas will settle.” •

Alice Kemp-Habib is an arts and culture journalist whose writing has appeared in The Guardian, Financial Times, The Economist and The Bookseller

45 SOUND AND SENSE

“I wanted to let the resources of poetry – sound, rhythm, repetition, the things that made me love poetry as a teenager – dictate the sense”

EVENTS

Brush up on screenwriting with Daisy Goodwin and enter the world of the Bloomsbury set

26 October

BLACK HISTORY MONTH: THE R.A.P. PARTY @ THE LONDON LIBRARY

Poet and playwright Inua Ellams brings the R.A.P. Party back to The London Library for Black History Month. This time, the theme is Rhythm and Prose, with a star studded lineup. Plus, event regular DJ Lily Fileen will be spreading her wings beyond hip-hop to play tunes that get you on your feet. Writers + a DJ = the best night out you’ll ever have in a library.

12 October ORLANDO DAY: THE INSPIRATION OF VITA SACKVILLE-WEST

Olivia Laing, Juliet Nicolson, Charlie Porter and Shola von Reinhold join chair Shahidha Bari to discuss the enduring influence of Vita Sackville-West and celebrate the 95th anniversary of her friend Virginia Woolf’s publication of Orlando . Sackville-West was a trailblazing novelist and queer icon who would weave her Bloomsburyset friends into her writing. In turn, she was a great inspiration to others, notably in the creation of Orlando

In partnership with the Royal Society of Literature

7.30pm – 8.30pm, in person

7pm – 9.30pm, in person

3 November WRITE & SHINE

Start your day with a 90-minute virtual writing workshop live from the Library. November’s session takes the friendship of psychological fiction writer Beryl Bainbridge and novelist Bernice Rubens, the first woman to win the Booker Prize, as its starting point. The pair became friends after meeting on a writers’ trip.

This is the final workshop in a series led by author Gemma Seltzer, celebrating the friendships, societies and creative communities that found inspiration at the Library.

7.30am – 9.15am, online

16 November

THE LONDON LIBRARY MASTERCLASS: SCRIPT TO SCREEN

Daisy Goodwin (creator of Victoria) leads a panel of experts as they explore screenwriting. Discussion and an audience Q&A will reveal how to write and sell a script.

This is a London Library memberexclusive event. Please have your membership number ready to book.

6.30pm – 8pm, in person

30 November

SAVE THE DATE: THE LONDON LIBRARY MEMBERS’ CHRISTMAS PARTY

Join fellow London Library members and staff in raising a glass to the festive season. Booking is essential. More details to be announced soon.

6.30pm – 8.30pm

For more information, and to be the first to hear about events at the Library, refer to the fortnightly newsletter, scan this QR code or visit londonlibrary.co.uk/whats-on

46

life and

Above: The

legacy of Vita Sackville-West will be explored by a panel of writers this autumn. Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

INCREASING FINANCIAL RESILIENCE

Philip Broadley, the Library’s Treasurer, reviews the 2022–23 financial year: one that benefited from exceptional, generous legacy income

The 2023 annual report, covering the year to 31 March, is now available to read on the Library website. The Library has benefited this year from substantial, unrestricted legacy income. This has generated an operating surplus and allowed the trustees to set aside funds to support future improvements to the Library.

Membership and usage

For the fifth successive year, we saw growth in net membership. The year ended with 7,458 members. We welcomed more than 1,300 new members in all categories. This growth was offset by 1,244 members leaving the Library: our retention rate of 83% showed a deterioration of three percentage points.

Membership has increased slightly in the first five months of the current financial year. The trustees are aware of the pressures on everyone’s income. We believe it is important to do everything we can to retain members by maintaining service levels while keeping fees as low as possible. At the AGM in November, trustees will be proposing fee increases of 5.1% (3.7% if paying by annual direct debit), again below published measures of the inflation rate.

Members made more than 55,000 visits to the Library and almost 57,000 books were loaned. We increased expenditure on acquisitions of printed and digital material by 11% this year to £276,000, and 4,700 printed items were added to the catalogue.

Financial review

The table included summarises the results of the p ast three years and shows that this year the Library’s total funds increased by £661,000.

Membership and trading income increased by 2% as the number of members grew and in-person events and external hires returned to pre-pandemic levels. The costs of running the Library decreased by 3%, mainly due to lower project expenditure.

Net fundraising income increased fourfold – principally because of significant legacy income, though income from donations also increased by 92%.

Each year-end, the Library’s financial investments are reported at their market value. There was a small reduction of £133,000 in the value of the investment portfolio, now £7.4m. We also recognise a decrease of £609,000 in the accounting surplus of the Staff Superannuation Fund.

A surplus of £767,000 is reported in the accounts but the Trustees do not consider this to be available to the Library.

At year-end, the Library held total funds of £31.7m, of which endowment funds represent £5.8m.

The value of donations

We have once again received substantial income from members and supporters, all of whom are listed in the annual report. Your generosity is vital for an organisation that receives no regular public funding. The Trustees thank everyone who has supported the Library in whatever way.

Three significant legacies from former members are recognised in the accounts this year. The Library received a further £112,000 from the estate of Christopher Smith, which has been added to the restricted fund for collection care that bears his name. During the year £650,000 was received from the estate of Susan Batty and £1,366,000 was received in June 2023 from the estate of Gweslan Lloyd. Accounting standards require this legacy to be recognised in the 2023 accounts as an accrual of known future income. Ms Batty’s and Mr Lloyd’s

47

legacies were unrestricted. The Trustees have decided to designate £750,000 of this legacy income to a new Repair and Renovation Fund and £380,000 to the Tom Stoppard Innovation Fund. These designated funds will enable continued investment into the Library’s buildings, systems and infrastructure over a number of years.

We will all benefit in the years ahead from the extraordinary generosity of these three members. We are truly grateful.

A return to operating surplus

A key objective of our strategic plan is the elimination of the operating deficit by 2023–24. Even after designating most of the legacy income to specific funds, the Library was able to generate a surplus of £110,000, meaning we achieved this target a year early. The progress to achieve this from 2018 is shown in the graph. The Trustees anticipate the operating result for the year to March 2024 to at least break even.

Operating results since 2018

Thanks to the continued growth in the number of members and generous legacy income received over the past 12 months, the Library’s financial position has strengthened this year.

Operating Results

THE LONDON LIBRARY 48

2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 £200,000 £100,000 £0 –£100,000 –£200,000 –£300,000 –£400,000 –£500,000 –£600,000 –£700,000

+£110k Surplus

49 ANNUAL REPORT Financial review 2023 Total 2022 Total 2021 Total £’000 £’000 £’000 £’000 £’000 £’000 Charitable activity and trading operations Income from memberships and trading activities 2,957 2,894 2,700 Less: related expenditure (4,232) (4,437) (3,942) Net operational cost (1,275) (1,543) (1,243) Fundraising activity Fundraising income 2,851 2,851 915 1,999 Less: related expenditure (402) (329) (289) Net fundraising income 2,449 585 1,710 Net investment income 229 236 196 NET INCOME/(EXPENDITURE) 1,403 (722) 664 before investment losses/(gains) Gains/(losses) in the value of investments (133) 644 1,034 Increase/(reduction) in the estimated SSF surplus (609) 706 711 NET MOVEMENT IN FUNDS 661 627 2,409

MEET A MEMBER

How radical histories of Britain fed into Elle Machray’s explosive debut novel

I never thought I was going to write a novel. Then, after George Floyd was murdered in 2020, I didn’t know how to process how I was feeling, and started writing poetry. It didn’t feel enough. I was accepted into the HarperCollins Author Academy, and began writing my first book.

Set in 1770, Remember, Remember follows Delphine, a woman who escaped slavery in 1766. She learns that her brother Vincent has also won his freedom, but things don’t go to plan. A trial is taken to the King’s Bench and, when it fails to deliver justice, Vincent and Delphine end up moving from legal action to something more extreme.

I wanted to explore the Gunpowder Plot – though it had happened a century prior to when my book is set – to understand what could drive a group of people to attempt something that devastating. In the 1770s, tensions were rising in Britain, cities had been fraught with protest and riots – the public was demanding change from politicians.

The Memoirs of Granville Sharp, a lawyer and one of the first to campaign to end the British transatlantic slave trade, and The Diaries of John Wilkes, 1770–1797, an 18thcentury radical, were both incredible sources, which

I accessed through the Library. I constantly referred to Popular Contention in Great Britain, 1758–1834 by Charles Tilly, and David Olusoga’s Black and British was like my bible. I borrowed the books he used as sources, which sparked ideas and fleshed out the world of the novel.

Some of the story is actually set in St James’s Square – though when I began, I wasn’t aware of the Library, even though I’d often walked past. I was given a membership in 2021. I now visit every time I go to London and love writing in the French language section a few floors up, overlooking the square. It feels very historic and it’s always quiet, which is what I need. Because I live in Edinburgh, the online resources and postal loans are really useful, too.

If there’s anything I’d like readers to take away from the book, it’s that we can be multiple things at once; a hero and a villain. When we fail to hold onto that idea, that’s when we get polarised.

As told to Deniz Nazim-Englund

Remember, Remember is out on 1 February 2024

50

“Some maps had been separated from their parent volumes to go it alone.” The cultural historian Kassia St Clair explores the Library’s unborrowed. Photo: Ameena Rojee

“Some maps had been separated from their parent volumes to go it alone.” The cultural historian Kassia St Clair explores the Library’s unborrowed. Photo: Ameena Rojee

“Writing is all I ever wanted to do.” Hampton in the Library’s Study this year. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

“Writing is all I ever wanted to do.” Hampton in the Library’s Study this year. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Hampton on the top floor of the Back Stacks. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Hampton on the top floor of the Back Stacks. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

BY JONATHAN COE (2020)

BY JONATHAN COE (2020)

Mills, shown here in the Art Room, calls the library “a refuge and a community”.

Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Mills, shown here in the Art Room, calls the library “a refuge and a community”.

Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Mills at the Library entrance. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Mills at the Library entrance. Photo: Hanna-Katrina Jędrosz

Harris in St James’s Square. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Harris in St James’s Square. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Harris has been a Library member for over a decade. His 2018 essay Mixed-Race Superman put him on the literary map. Photo: Ameena Rojee

Harris has been a Library member for over a decade. His 2018 essay Mixed-Race Superman put him on the literary map. Photo: Ameena Rojee

BY VERONICA FORREST-THOMSON (2008)

BY VERONICA FORREST-THOMSON (2008)