3/4 BAKED: A RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

JASON F. MCLENNAN

THE ART OF JOSH FISHER REGENERATIVE ART

MODEL N FURNITURE

INTERVIEW WITH CEO WORLD’S FINEST CHOCOLATE

LIVING BUILDING

CHOCOLATE FACTORY

BY GAIL VITTORI

3/4 BAKED: A RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

JASON F. MCLENNAN

THE ART OF JOSH FISHER REGENERATIVE ART

MODEL N FURNITURE

INTERVIEW WITH CEO WORLD’S FINEST CHOCOLATE

LIVING BUILDING

CHOCOLATE FACTORY

BY GAIL VITTORI

For many of us in our studio its been an epic summer filled with travel, great projects and continued developments. We have moved into our new office in Fort Ward on Bainbridge Island and - while its not quite done – the light is finally at the end of the tunnel. Look for an upcoming issue that celebrates our transformation of an over 100-year old relic into a great office space. This has been an important season for the growth of our team as well – with incredible new team members joining us from India, Iran, Canada, and New England. Our team is getting more diverse and talented every season, and we look forward to introducing you to the newest members of our team over the coming months. In this issue, we highlight the work of our longest serving employee – Josh Fisher – who creates a whole world through his zany and cool illustrations, including three incredible paintings he did for our new office with his art mural partners, Fisher Bennett Sanchez.

But as the days begin to shorten, it is also a bit bittersweet. This summer has seen manifest the early worldwide ramifications of climate change –with forest fires in my home country of Canada out of control and smoke descending throughout Canada and the United States and at times reaching us here on Bainbridge Island. From Hawaii to Europe and in-between, the Northern hemisphere burned. Do we wish for cooler, wetter, weather again as soon as possible?

This issue is dedicated to a fellow green warrior who worked hard to help our industry change its impact on the planet, and who left us too soon at the start of the summer. Robin Guenther passed away and she is missed by people all over the country for her incredible spirit and the contributions she made to raising awareness at the intersection of healthcare and sustainability. Robin helped bring attention and focus to an industry that while ostensibly focused on wellness - has continued to ignore the larger patterns that contribute to creating it. I first met Robin at a GreenBuild conference about a decade and a half ago. She was collaborating with another dear friend – Gail Vittori of the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems – and it is therefore fitting that Gail has written a personal dedication here in our pages.

We miss you Robin!

Fall is here my friends. Enjoy this issue of Love&Regeneration.

Sincerely,

Jason F. McLennan Principal, McLennan Design Chief Sustainability Officer, Perkins&Will

Jason F. McLennan Principal, McLennan Design Chief Sustainability Officer, Perkins&Will

Jason F McLennan

Susan Croy Roth

Josh Fisher and Galen Carlson

September 2023, Volume 5, Issue 3

LOVE + REGENERATION is a quarterly publication of McLennan Design, LLC.

© 2023 by McLennan Design / Perkins&Will. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission and is intended for informational purposes only.

Cover: Robin Guenther

McLennan Design respectfully acknowledges the Suquamish and Duwamish peoples, who, throughout the generations, stewarded and thrived on the land where we live and work.

1954 - 2023

By Gail Vittori“Our lives are touched by those who lived centuries ago, and we hope that our lives will mean something to those who will live centuries from now. It’s a great ‘chain of being,’ someone once told me, and I think our job is to hope, to dream and to do the best we can to hold up our small segment of that chain.”

Robin and I prefaced both editions of our book, Sustainable Healthcare Architecture, with this quote from Dorothy Day. We undertook the book with the hope that it would, indeed, mean something to those who live centuries from now – but, more importantly and immediately, to effect change now, with an extraordinary urgency to communicate the most bold, consequential concepts related to buildings and health that we could articulate.

It was after one of our healthcare conference presentations that John Czarnecki, then at Wiley, approached Robin about writing a book, and then Robin turned to me, somewhat casually as I recall, asking if I would like to write a book with her –and without hesitation, I said yes. That we agreed to this unanticipated opportunity without thinking through the practical considerations of how to squeeze it into our already overextended lives, or that neither of us had written a book before, says it

all – the book was a conduit to ‘scale’ the precepts that underpinned our work: We believed that decisions associated with the design, construction, and operation of our built environment represent one of the most consequential endeavors relative to human health, and the book provided an opportunity to make visible what are too often invisible links between buildings and human health. (We proposed that the title be Sustainable Architecture for Health, seeing an opportunity to extend the market reach beyond health care, though Wiley’s preferred title Sustainable Healthcare Architecture prevailed, asserting that it would become the definitive book on green health care design.)

That the book even happened could not have been foreseen at the time. Greening the healthcare sector was gestational – the Green Guide for Health Care, which Robin and I co-coordinated initially with Tom Lent, with support from an extraordinary steering

Robin was an advocate and a senior advisor for Health Care Without Harm, a no profit that seeks to reduce the environmental impact of hospitals.

committee and modest funding from the Merck Family Fund – was just getting its legs. The U.S. Green Building Council had just green lighted development of LEED for Healthcare. There were only four LEED® certified health care buildings in the world – two hospitals and two diagnostic and treatment facilities. (In the five years between the publication of the 1st and 2nd edition books, the number of LEED certified health care buildings exploded from 4 to 180—a 450% increase.)

I would be remiss not to mention the broader sustainability context of those times in the mid-2000s, that seems almost unfathomable today: correlating buildings and health was controversial, and, in particular, were health risks of certain chemicals used to manufacture building products—in health care buildings and more generally. We were, for example, cautioned about presenting

scientifically supported data about materials and health at conferences and in trade publications. Yet, as we wrote in the Introduction to our 1st edition book (published 2008): “We can and must do better…Healthcare leaders are intentionally connecting buildings to mission and community benefit. They view these buildings as part of a life cycle continuum in which the invisible consequences of building decisions on human and ecosystem health—on the local, regional, and global scale—are as important as those that are visible inside the building’s walls every day…most of all, (they) honor the fundamental precepts of prevention and precaution—the best choice of all is to avoid conditions that create potential problems in the future.”

Indeed, as we conceived of the 2nd edition book, we put forward an integrated health-based ecological framework, predicated

on carbon neutrality, persistent bio-accumulative toxic chemical elimination, water balance, and zero waste as measures of success. That was a decade ago; we know today that these tenets are the appropriate – and needed - basis of design for a much larger cohort of projects, along with other concepts that have emerged as essential since then.

To work with Robin on this book, and on so many other endeavors over more than two decades, was profoundly and exceptionally inspiring. It was life changing. As book writing novices, we crafted our own approach, figuring it out as we went, and having the confidence that goes along with a certain amount of naiveté. Robin exuded a seasoned wisdom always: in writing the books, she sensed when a subtle or more substantive course correction was warranted, enabling us to stay on track, even as our ambitions of what we wanted to accomplish soared. We scheduled multi-day immersions in New York and Austin; challenged ourselves to pinpoint the right complement of ‘big ideas’; engaged colleagues and several people we didn’t know to write essays to bolster the book’s depth and rigor; nerded out on the intricacies of defining our ‘key sustainability indicators’ (and our complicated recipes!), and with our small, amazing support team, sifted through hundreds of projects from around the world to craft into our case studies – 62 in the first edition and 55 in the second edition. In aggregate, these projects create an irrefutable

proof of concept that the idea of turning ‘towers of illness’ into ‘cathedrals of health’ (as Charlotte Brody so eloquently postulated in a 1st edition essay) is not only possible, it is an imperative.

“I don’t know how she does it” is a rational response to Robin’s dizzying, super-human level of activity and accomplishments—she embraced her impressive portfolio of professional work with a deep level of humanism and empathy. She adored her husband Perry, her daughters and granddaughters, and acknowledged the toll of having a life partner buried in writing a book—not just once, but twice. She was funny and generous; passionate about mentoring (always conscious about having the next generation of leaders primed to take charge). She was the special friend one could only dream of having.

One can hope that in our lives an opportunity comes along to move the needle of what we most deeply care about even just a little bit, to “hold up our small segment of that chain of being” as Dorothy Day suggested. Robin’s influence and impact, her passion for innovative disruption, did more than move the needle a little bit: they represent a step change in how we think, how we do our work, and where we set the bar for basis of design. Thank you, Robin, for all your contributions.

You will forever be an inspiration to me and to so many others.

“...we have the ability to collect and reuse the material to make new products or see to it that they end up somewhere that they can be composted, recycled or preferably biodegrade.

Q: You have taken a non-traditional path to leading Model No

Would you tell our readers more about what brought you to the company and why you were excited to join and lead the Model No team?

A: I’ve always had an interest in furniture and design. Throughout my career I’ve been obsessed with commercial interiors (e.g. hospitality, work) and the impact that it has on humanity and personal experiences. Equally, I’m resolute in reducing waste and being more mindful about the materiality of products and ultimately our environment. So having the opportunity to marry the two only seemed fitting.

Q: Model No is ambitious if nothing else. How would you personally describe the company’s core purpose or reason for being?

A: We see the need to design and manufacture products differently. As a small company you can’t immediately change the ways of a $500B dollar industry, but you can show people that there is a better way to do things and still maintain design integrity. Eventually, the industry starts to take notice–which is our goal at Model No

Q: Not unlike the fashion industry, the systemic challenges of furniture relative to the planet are daunting to say the least. Estimates say commercial interiors - and the furniture in them - turn-over approximately every 5 years, leaving behind a mass of waste and carbon emissions. What do you see as the issue behind this turn-over?

A: Desire for change without perceived consequences. In the last 70 years, low-cost labor and manufacturing has trained consumers to replace products rather than refurbishing, fixing or buying second hand. In both commercial and residential settings, wear and tear, trend and personal taste change. Rather than completely changing human behavior, we are leaning in and have developed products that eliminate waste buy using existing materials to make furniture. Similarly, when the product reaches the end of life…we have the ability to collect and reuse the material to make new products or see to it that they end up somewhere that they can be composted, recycled, or preferably biodegrade.

Q: Thinking a bit about the end-game of Model No, what do you want to be different as a result of Model No and its work? What does success look like?

A: Despite having a strong mission to eliminate waste in the furniture industry, we understand the design is at the core of everything that we do. There are very few poorly designed products that are successful. So it’s important that we design products that people love…but equally important that we can proudly stand behind the products that we make knowing that we are creating something that won’t contribute to further waste. Ultimately, I look forward to seeing a large number of copycats as long as they are authentic in what they’re doing.

Q: What progress has been made so far? What has been the most surprising learning during this initial chapter of Model No’s?

A: While we are making meaningful progress, it is still early days in our journey. After launching our first products in the Fall of 2021, we’ve seen significant improvement in our product designs, especially in the area of lighting and seating, along with our production capabilities. One of the biggest lessons for me was realizing that despite designing and manufacturing in-house, there are a lot of external factors that can impact our ability to scale. I see that as both an advantage and challenge moving forward…the advantage is that it will be hard to replicate what we’re doing without time and significant resources. But it also means that we have a lot of work ahead of us until we can make a seismic shift in the industry.

“...we can proudly stand behind the products that we make knowing that we are creating something that won’t contribute to further waste.

“...we have a lot of work ahead of us until we can make a seismic shift in the industry.

Q: What excites you most about our partnership?

A: Jason’s commitment to design and its impact on the environment are well documented and reflective in the work that McLennan Design puts into the world. Having the opportunity to work together not only adds a megaphone to our world, but it gives Model No the opportunity to learn, grow and better understand where we can evolve as a brand to make an impact on future projects.

We will continue to dialogue with the team from Model No in future issues - so stay tuned to learn more!

Note – This is a reprint from a chapter in the 2011 book – Zugunruhe – The inner Migration to Profound Environmental Change by Jason F. McLennan – Ecotone Publishing

As odd as it may sound, I’ve always tried not to seek perfection. Don’t get me wrong; I always give my best effort and work hard at whatever I do. I believe wholeheartedly in committing myself to each task I face, and devoting all of my knowledge and energy to the job at hand. But … I have also learned when to stop. I have trained myself to recognize the point at which my continued efforts might actually hinder a project’s progress; the point when it’s time to release my work into the world to allow other individuals or forces to complete it.

This is the stage I refer to as ¾-baked.

When we refer to something as “half-baked,” we often mean that it is inadequate or incomplete. The phrase has a negative implication. To extend the culinary metaphor, a half-baked item is undercooked; it is certainly unappetizing and it is possibly hazardous.

When I talk about ideas or tasks being ¾-baked, I mean that they have reached a special moment in time or development where the idea has significant shape, clarity and elegance. It can stand on its own, perfectly workable, yet still has room for some improvement, some rough edges and questions

yet to be resolved. When a concept is ¾-baked, its original author or “architect” has taken it to a certain stage of near-completion, then, resisting the urge to keep refining, has offered it up to the outside world for feedback, criticism and testing. Oddly enough, aiming for this stage of development, rather than striving for perfection itself, is likely to bring about a more perfect result.

The artist who aims at perfection in everything achieves it in nothing.

-Eugene DelacroixExample of a half-baked idea - fracking for natural gas.

In my opinion, when people strive to work on things to the point of perfection, they are usually fooling themselves. “Perfectionists” spend so much time and energy making miniscule improvements that they often end up losing sight of the ultimate goals of the projects they tackle. We’ve all heard the statistic that 90% of our efforts are expended on 10% of the result. It is usually the last 10% or the last 25% that does us in – and keeps good ideas from ever going somewhere.

When I studied in Glasgow, Scotland, I had a classmate who was an incredibly talented designer. The only problem was that he always aimed for perfection in everything he did. He would work endlessly on something and never knew how to let go – he couldn’t move on until it was perfect, which meant that he rarely moved on at all. He consistently produced beautiful artifacts, but he never completed them. Regardless of the assignment and its importance, he put in the same amount of effort and placed the same amount of pressure on himself. As a result, he suffered greatly from stress, even over assignments that were inconsequential. He had been carefully taught only to pursue perfection; indeed to equate his own value as a person with how close to perfect his accomplishments were. Each assignment was a huge challenge for this student – he did not know how to stop and be satisfied. Being human, he repeatedly produced things that were

less than perfect. Not surprisingly, his self-esteem suffered greatly. He had never learned the valuable lesson of scaling effort to the importance of the task at hand. Nobody taught him that chasing perfection was a fool’s errand. By the end of the year, my friend was close to failing due to the number of assignments that he simply could not complete. He refused to move on with one element of an assignment until it was perfect; then he ran out of time or became immobilized by the self-generated pressure. The sad thing was that the quality of his work was higher than just about anyone’s in our year –but he was his own worst enemy. In trying to go for a home run each time, he never scored a single hit.

Later in life, I became friends with a man who was an amazing trumpet player. From a young age, he showed talent that his father (as well as his teachers) spotted as real potential. In an effort to encourage his son, the father ended up instilling an unhealthy set of expectations focused on being “perfect.” When my friend became older, he stopped playing altogether. I assumed that he quit because he no longer enjoyed the trumpet. In actuality, he told me that he loved the instrument and missed it terribly. But he gave it up when family and work obligations limited his practice time to what he perceived as an unacceptable level, and he began to hear nothing but his mistakes. For him, this artistic pursuit was all or nothing; he felt he needed

to be perfect or not play at all. In his case, a quest for perfection killed the music in this man, and I believe that his life was less rich as a result.

One of the secrets to success is knowing when to stop, how hard to work and for how long. I have seen so many great talents waste their skills on the hubris of perfection.

In so many disciplines, the “perfect is the enemy of the good.” People obsess over details, worrying about acceptance, approval and propriety. By the time they finish an endeavor, the reality has often changed, making their deliberations all for naught. I’ve watched as skilled professionals have blown projects not by under-performing but by over-thinking to the point where they missed deadlines and/or exceeded budgets. Show me a perfectionist, and I’ll show you someone who doesn’t get much done.

People throw away what they could have by insisting on perfection, which they cannot have, and looking for it where they will never find it.

- Edith Schaeffer

The greater the emphasis on perfection, the further it recedes.”

- Haridas Chaudhuri

The thing that is really hard, and really amazing, is giving up on being perfect and beginning the work of becoming yourself.

- Anna Quindlen

In any endeavor, scale the effort of your work to the effort required for success. Accept that sometimes your ‘best’ is not always the same under all conditions.

Do not overthink or overdo. Learning balance and restraint without harsh internal judgment is a fundamental requirement of true success.

How do we seek and identify the ¾-baked sweet spot of our own undertakings? How do we give ourselves permission to be less than perfect, while demanding from ourselves more than mediocrity?

Often, when I am seeking my own answers to life’s dilemmas, I cook. I find that cooking provides many lessons applicable to our lives and the decisions we have to make. Releasing a project when it is ¾-baked is a lot like preparing asparagus. Let me explain: If you steam fresh asparagus until it is “perfectly cooked,” it will actually end up overdone and soggy by the time you eat it. Why? Because it continues to cook as long as it’s hot. Anyone who enjoys this particular vegetable knows that there is a very fine line between deliciously al dente and horribly mushy asparagus. An experienced chef knows when to remove it from the hot water – while it’s still undercooked; about ¾ cooked. Some even plunge it into cold water immediately after removing it from heat. In either case, the universe (in the form of cold water or the absence of hot water) finishes the job to help accomplish crunchy-but-cooked excellence.

When we put something out in the world – an idea, a design, a project – we must be willing to accept that the idea is not likely perfect. When we are open to possible changes and criticisms and invite others to expand upon our original vision, we give our work and ourselves a great gift. When we hold onto an idea too long as we pursue its perfect execution, we run the risk of squeezing the life right out of it.

So an idea’s sweet spot – the time and place in which it is ¾-baked – is the point between its conception and its death by strangulation.

When we release our ideas into the ether, magical transformations can take place. It takes courage to let go of our biggest and boldest work, especially when doing so requires acknowledging imperfections and possibilities for error. But taking that chance often leads to great things – magical things, even – when the ideas are good enough to take on a life of their own.

The universe, it seems, will provide what is required when we allow it to, doing away with bad ideas (usually for everyone’s benefit) and elevating good ones. The individual who gives birth to the idea, and is strong enough to release it fully when it is ¾-baked, enables the world to:

1. Determine whether the idea is worthy,

2. Strengthen the idea and help it shine more brightly,

3. Focus importance on the idea rather than the author,

4. Remind us all that letting go of ego can be the best idea of all.

After all, if it’s change we seek, we need not concern ourselves with glory. Work released in the right spirit tends to find ways to reward its creator. The ideas that come out of the collective movement will safeguard our future, regardless of how or by whom they are created. Releasing ideas into the universe in the spirit of selfless passion for change results in powerful magic.

Since the mid-1990s, I’ve been focused on a concept that I call Living Buildings. I coined the term while working on a project in Montana called the EpiCenter, as our team sought to describe building performance that was “truly sustainable.” The idea is that nature, not machines, provide the ideal metaphor for the buildings of the future.

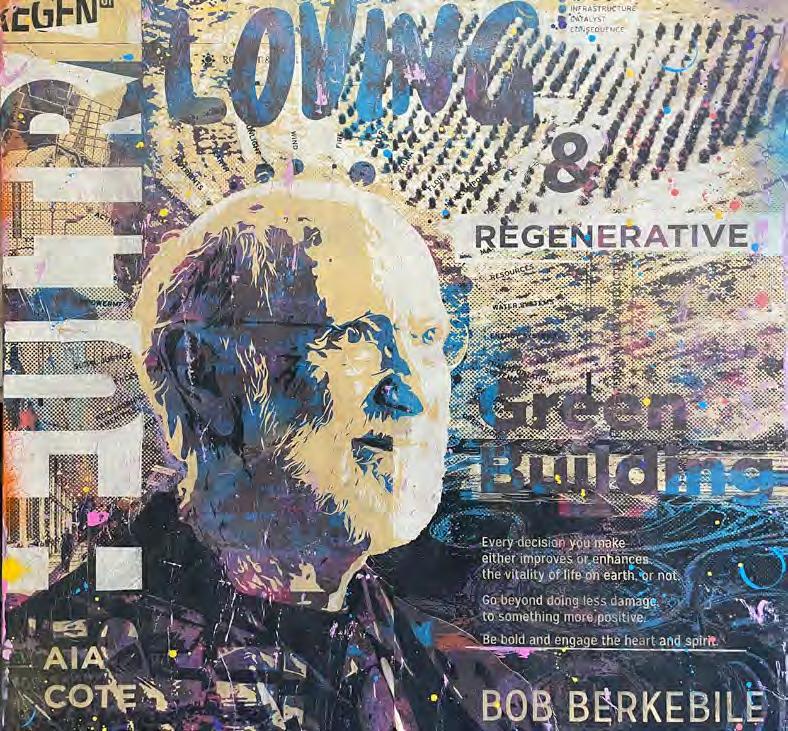

What is a Living Building? Imagine a building designed and constructed to function as elegantly and efficiently as a flower; one that is informed specifically by place, climate, topography and microclimate. Imagine buildings that generate all their own energy with renewable resources; capture, treat and re-use water in a closed-loop process; operate pollution-free with no toxic chemicals used in any material – all while being a beautiful inspiration to anyone that interacts with them. Even before LEED came to fruition, Bob Berkebile and I spent hours focusing on how to develop the Living Building idea, eventually publishing a series of articles on the subject. Back then, it was always only a fuzzy concept – a vague notion of the kind of impact that we desired buildings to have.

In 2005, I was encouraged by the growing strides that the green building industry was finally making. I had worked on two Platinum LEED projects and two Gold LEED projects, all of which were done on budget and on time, and I was convinced that the industry was ready to go deeper. So in my spare time in the evenings and on weekends, I began working on codifying what a Living Building needed to do to deserve the designation. I finished the first version of the Living Building Challenge while moving out to Seattle before starting as the new CEO of the Cascadia Region Green Building Council in the summer of 2006. I knew that what I had on my hands was a special document, but I also understood that it was far from perfect. It was a powerful idea –3/4-baked – and ready to be shared with the industry. I decided to bring the intellectual property to Cascadia and to give it away without asking for any compensation. It had too much potential to be “owned” by a single individual, and the spirit of the tool demanded that personal profit could not be a motivator in releasing the work. But there was an important condition: when I offered the tool to the organization’s board of directors, I told them that they could have it provided that we made it a centerpiece in the organization’s future. They accepted, and that decision started a chain of powerful and positive outcomes.

Any good idea needs three things: the right timing, the right message and the right platform. With Cascadia, all three began to align to make the Living Building Challenge a reality. Pulling some strings with some friends at the US Green Building Council, Bob Berkebile and I united to present the idea at the 2006 GreenBuild in Denver to a crowd of several thousand leading practitioners. Opening right before my childhood hero, David Suzuki, we asked the assembled delegation to join us in accepting the “Challenge.” In a moment that will always remain a powerful personal milestone for me, the whole assembly rose in a spontaneous standing ovation. Releasing a ¾-baked idea had started a paradigm shift in the building industry. Since then, what has happened has been truly phenomenal: thousands of projects have emerged all over North America and beyond, with Living Buildings now a reality in every climate zone and region. These buildings provide critical models for how people will live, work and play in the coming decades, finally reconciling the balance between the natural and built environments. Thousands of people from many different disciplines - most of whom I have never even met - are now working to advance the ideas of the Living Building Challenge. I could never have done this alone -the trick was releasing a beautiful vision ¾ baked into the world and watching what happened.

Release your ideas and innovations to the world when they are ¾ baked.

Learn when to stop and invite others to contribute and collaborate and reject the urge to constantly refine and improve until something is perfect before sharing.

Chasing perfection is a fool’s errand.

The chance for perfection grows by letting go - not by hanging on.

If you’ve seen any of the videos or renderings illustrating the regenerative work that our team has created, Josh Fisher has most likely had a hand in the design and creative visualization of it. Josh is an Associate and Director of Visualization with the Mclennan Design team. He is also one of the original founding members of Mclennan Design and for the last decade has implemented his artistic talent in the design of projects across North America and beyond.

What you may not know, is that Josh is also an emerging local artist, on the ArtsWA State registered art panel, a past Kitsap County Arts Commissioner, co-founded an independent art studio, and has a growing collection of public and private work ranging from LEED approved interior murals, multiple art commissions for the City of Bremerton, a 300 foot mural for the City of Friday Harbor, a 120-foot mural for Sound Transit, and an increasing collection of gallery work.

He not only works full time at McLennan Design, and progresses his art, and remains involved in his community, he is also a devoted husband and a father of four young boys!

We sat down with our coworker, artist, and friend and asked a few questions about his art, inspiration, and ambitions.

Q: When do you find time to pursue your art with the full-time demand of your job and with four young boys at home?

A: It’s certainly a decision and commitment to set aside time to create art with the daily work our studio is doing and then balancing that with home life and four energetic young boys. In this phase of my life, even if it’s just sitting down for 15 minutes to draw or doodle something, I’m trying to weekly do something. It usually means I’m carving out time after everyone is asleep to get creative in some capacity. Depending on the status of murals and commissions, once a month or sometimes more we’ll meet at my buddy’s art studio and get paintings done after all our families have settled for the night. It’s always a highlight and it’s a great way to get inspired after studio time, share ideas, have some music playing, and collaborate.

Q: What are you trying to communicate in your work?

A: Simple: Love where you live! If my art has a theme or is trying to say something, it’s rooted in the belief that we should do the most good possible towards others and the place we live, work, and play and to enjoy the daily life of doing these things!

The second theme would be for goodness sake, can we be a little more courageous and entertain the idea that the places we live in could be just as desirable and worthy of love as the places we go vacation to? The idea that we spend our short vacations to get out of town and go to other places that are usually just better urban places or filled with preserved nature, are walkable, filled with detail and character and then come back home for the rest of the year to accept things as is, is something I hope my art speaks too. The idea would be that in our own backyards, neighborhoods, and towns are people and places worth caring for and that have tremendous potential.

A: There’s a combination of things that inspire me and help me cultivate my art. Being a lifelong learner, retaining a curiosity about things, and exploring ideas with imagination help to provide a steady supply of inspiration that informs the work I do. It’s also been beneficial to build relationships with other creatives in my area and get inspired by what peers are doing; it’s easy to get excited about making art and doing public projects when you see the meaningful impact they have and create things together with friends. I find that I’m frequently cross-referencing ideas and things we’re doing in the firm, and they work themselves into the art; even if it’s as simple as doing a public mural and spending time researching what might be unique flora or fauna to a particular place or special cultural elements that we can celebrate and incorporate into the artwork. I try to continuously experiment and explore new areas, challenge my own perceived limits, push forward to larger scales of art, and work towards meaningful outcomes for each project I do to stay inspired and motivated.

A: My practice primarily involves photography, stenciling, acrylic painting, and hand drawing illustrations. With the paintings and murals, the works and scenes are mixed media based on images and motifs that through layering process and technique - becomes a sort of visual diary or collage of researched images, vintage paper such as maps, advertisements, articles, music sheets, or topographical charts that are blended with stencils, paintings, and drawings. Depending on the complexity and scope of the mural, I’ll work with my project team to explore and experiment with the right approach and concept.

In the personal drawings and art, such as the madeup world scenes, I typically begin with a blank piece of paper and just start drawing whatever comes to mind as a sort of creative outlet and pour into it ideas for some sort of idealistic landscape and scene. These are fun pieces to develop and explore as a sort of unconstrained outlet, but you could almost imagine that it could be a sketch of a real place somewhere in the world.

Q: What pieces of art are you the most pleased with?

A: My favorite mural so far is the one that I was able to create with my buddy, Cory Bennett Anderson @artbycbennett. We won a Pacific Northwest regional RFQ for an almost 300-foot mural for the Town of Friday Harbor. We painted a mural inspired by the flora and fauna of the San Juan Islands in less than a week during the summer. It turns out that the wall was on the busiest street on the island and we had the town driving by watching our progress each day! With our timeline and families back home, we had to paint the entire wall in less than 4 days. We would stay up painting in the evening, have positive vibe music playing, and the locals loved it; driving by each morning to see how much changed overnight. We always try to engage with locals when we do public murals and on the island we invited K-12 students to come out and help paint, making their mark, by adding a hand print, name, or word. This invitation is one way that we can help connect with the people and place, and now the island residents have stewardship in the mural and can walk up and see where their mark is now part of the larger art concept.

A: Yes, absolutely. It’s hard to turn off the idea generator when I get to work with a team like McLennan Design, who dreams big, is future oriented, asks challenging questions, and daily tries to do better than the status quo, especially regarding the quality of the homes, workplaces, and environments we live and play in. In a lot of the art I do, there is a deep-rooted sense of trying to create places that are filled with life, character, detail, fun, and whimsy, and that’s a conscious reaction to the unfortunate mundane built environments that are all too commonplace. Murals are one way to instantly break up the monotony of a public space and an opportunity to make something that grabs attention and adds some color, fun, and whimsy to an area.

Having 10 years of experience seeing how we can imagine buildings, urban spaces, and products that are healthy, beautiful, and connected to place has provided me with a keen eye for seeing public spaces and areas around towns as a canvas for art that, in its own way, can communicate similar ideas through murals and community engagement. Daily at MD we’re approaching our work with multiple lenses: what can we learn about the place we’re designing in, about the people who live and lived there, analyzing local ecology and ecosystems, and creatively as well as technically merging all these inputs into the design solutions we create to help create places for our clients and communities.

In my art and public murals, I’m approaching the process in a similar way. Public murals are - in a way - a statement being made and something that I get entrusted with the stewardship of; they’re placed in communities that I don’t live in, yet have the opportunity to blend inspiration and my art. So doing murals that reflect these influences and context is one way that I create art that respects and celebrates people and place; just like we try to do in our work as McLennan Design.

“Foilage Series”

New series of ecological flora, and fuanabased paintings and illustrations

A: First and foremost, to be grateful for any time I get to make art! I never want to lose appreciation and acknowledgment that it’s a gift and blessing to be able to make art. Throughout my development as an artist, I’ve received support and encouragement from family, friends, and clients and I hope to be able, through my art, to be just as charitable and supportive of others as I have the ability and opportunity to do so.

Long-term, I would consider it a success and honor to create a body of work that inspires a monumental shift in how we view the ordinary spaces in our own neighborhoods and towns. I want to help contribute to a transformation of the communities we live in from unproductive landscapes and mediocre buildings to thriving life-filled landscapes with buildings and places that are cared for with artistry, detail, and beauty. Why do we pack up and get out of town to go visit other places across the world when our own homes and areas we live in have the potential to be just as special and worthy of love? If I could make art that speaks to these ideas and inspires meaningful change, that would be worth it!

Raising a family and having children, I’d love for them to grow up and see through my work an example of how it’s possible to have a professional career and also be an artist, involved in your community, and integrate your interests in what you do for hobbies and for work. I hope as they get older that I could create murals and projects in other cities and landscapes that allows us to travel together, visit new places, meet new people, and for them to get exposure to other geographies and demographics and for that to inspire whatever they do in their life!

We have a website under development which will be launched soon. Until then, check out @fisher_bennett_sanchez to see more of our murals and artwork that I create with my art partners.

I HAVE BEEN SO hawk-addled and owl-absorbed and falcon-haunted and eagle-maniacal since I was a little kid that it was a huge shock to me to discover that there were people who did not think that seeing a sparrow hawk helicoptering over an empty lot and then dropping like an anvil and o my god coming up with wriggling lunch was the coolest thing ever.

I mean, who could possibly not be awed by a tribe whose various members can see a rabbit clearly from a mile away (eagles), fly sideways through tree branches like feathered fighter jets (woodhawks), look like tiny brightly colored linebackers (kestrels, with their cool gray helmets), hunt absolutely silently on the wing (owls), fly faster than any other being on earth (falcons), and can spot a trout from fifty feet in the air, gauge piscine speed and direction, and nail the dive and light-refraction and wind-gust and trout-startle so perfectly that it snags three fish a day (our friend the osprey)? Not to mention they look cool— they are seriously large, they have muscles on their muscles, they are stone-cold efficient hunters with built-in butchery tools, and all of them have this stern I could kick your ass but I am busy look, which took me years to discover was not a general simmer of surliness but a result of the supraorbital ridge protecting their eyes.

And they are more adamant than other birds. They arrest your attention. You see a hawk, and you stop what minor crime you are committing and pay close attention to a craft master who commands the horizon until he or she is done and drifts airily away, terrifying the underbrush. You see an eagle, you gape; you hear the piercing whistle of an osprey along the river, you stand motionless and listen with reverence; you see an owl launch at dusk, like a burly gray dream against the last light, you flinch a little, and are awed, and count yourself blessed.

They inspire fear, too — that should be said. They carry switchblades and know how to use them, they back down from no one, and there are endless stories of eagles carrying away babies and kittens and cubs left unattended for a fateful moment in meadows and clearings, and falcons shearing off the eyebrows of idiots climbing to their nests, and owls casually biting off the fingers of people who discover Fluffy is actually Ferocious. A friend of mine deep in the Oregon forest, for example, tells the story of watching a gyrfalcon descend upon his chickens and grab one with a daggered fist as big as my friend’s fist, but with much better weaponry, and then rise again easily into the fraught and holy air

while, reports my friend with grudging admiration, the bird glared at him with the clear and inarguable message, I am taking this chicken, and you are not going to be a fool and mess with me.

I suppose what I am talking about here really is awe and reverence and some kind of deep thrumming respect for beings who are very good at what they do and fit into this world with remarkable sinewy grace. We are all hunters in the end, bruised and battered and broken in various ways, and we seek always to rise again, and fit deftly into the world, and soar to our uppermost reaches, enduring with as much grace as we can. Maybe the reason that so many human beings are as hawk-addled and owl-absorbed and falcon-haunted and eagle-maniacal as me is because we wish to live like them, to use them like stars to steer by, to remember to be as alert and unafraid as they are. Maybe being raptorous is in some way rapturous. Maybe what the word rapture really means is an attention so ferocious that you see the miracle of the world as the miracle it is. Maybe that is what happens to saints and mystics who float up into the air and soar beyond sight and vanish finally into the glare of the sun.

The new factory and visitor center will be a restorative destination that welcomes guests with a multi-use arrival plaza surrounded by a regenerative landscape that is envisioned to include restored prairies, bioswales, pollinator gardens, orchards, and publicly accessible walking trails and event fields.

As a studio dedicated to creating great places through the practice of architecture and regenerative design, we are thrilled when our work enables our friends, clients, and the communities we practice in to scale up their positive impact through the services they provide.

Maybe it’s the boxes of chocolate our team has been snacking on, but we’ve been having a blast helping imagine, create, and design a new chocolate factory and visitors center Concept for World’s Finest Chocolate (WFC) company based in Chicago, IL.

When it comes to community impact and potential, our friends at World’s Finest Chocolate are second to none. Since 1939 they have crafted premium chocolates and confections and have helped communities raise over 4.5 billion dollars through their fundraising campaigns for schools around North America. We’re excited to share our early conceptual work as just a teaser of things to come as the project develops. The design is surely to evolve once beyond concept, but we can anticipate that the future factory and visitor center will become a cherished community asset and enable the company to increase it’s meaningful impact in the lives of so many.

World’s Finest Chocolate is outgrowing their current factory in Chicago and when their Third Generation Family CEO, Eddie Opler met Jason F McLennan and learned about the Living Building

Challenge and philosophy of regenerative design he recognized this was a perfect opportunity to both create a new facility that will enable WFC to expand it’s services, but to also do so in way that complimented the company’s values around environmental stewardship. The company’s mission: To deliver extraordinary value with fun and purpose.

Our team has been developing an initial testfit concept that provides WFC with a new adaptable factory and interactive exhibition spaces as well as visitors’ center amenities where guests can get a first hand look, taste and experience inside a chocolate factory. Envisioned as an approximately 400,000 square foot facility, the factory and visitor experience center will enable seamless, modern, efficient operations and a guest experience that is second-to none to simultaneously occur. Visitors will be able to journey through spaces that celebrate the community impacts WFC has helped through it’s fundraising efforts, honor the legacy of the Opler family, provide an experiential exhibit that takes guests through the chocolate making process; from where chocolate is grown, how it’s processed, and produced. Greenhouse spaces will showcase what it’s like in a cacao plantation and sugar cane farm so that even in a northern climate, visitors could visibly experience and understand the origins of chocolate and do so in an interactive and fun way. Throughout the exhibition spaces, there will be peek-a-boo

Left: Inside the visitor’s center exhibition hallway where guests can journey through spaces learning about the chocolate making process, see factory operations in action, and celebrate the community impacts of WFC.

moments where guests can view the operational factory and see first-hand the many stages of work and production that goes into making chocolate bars and eventually making their own custom chocolate treats at the end of the journey

From a sustainability standpoint, the vision is to create a factory and visitor center that meets all the requirements of the Living Building Challenge and includes rooftop solar arrays, passive heating and cooling and advanced MEP systems, pollinator friendly vegetated roofs, and landscaping that includes rain gardens, bioswales, orchards and gardens, event lawns, and restored prairie meadows. Integrated in the landscape will be community recreational spaces and an event hall with café, retail, and a living

machine that will showcases how the building responsibly handles and treats it’s water and waste.

When built, this facility is anticipated to become a major tourist destination in the UpperMidWest and will demonstrate responsible design and development in a fun and purposeful way to millions of visitors over its lifespan. Our hope is that this not only promotes even more growth and community impact through the WFC chocolate bars but also regenerates a place, inspires all who visit, and becomes a new standard for how factories can be built; all for the love of chocolate!

Stay Tuned for continued development!

Left: Conceptually, the gable roof form is derived as a series of row houses that provide enough height for cacao tree greenhouses. The gable form is then repeated for each part of the chocolate making experience center.

Designed by Jason F. McLennan, the founder of the Living Product Challenge, and his team at McLennan Design, Mohawk Group is proud to introduce the Lichen Collection, the first floor covering to achieve Living Product Challenge Petal Certification. Inspired by assemblages of multi-hued, multi-textured lichens and their regenerative role in our ecosystem, the Lichen Collection is o n the path to give more resources back to the environment than it uses during its entire life cycle.

In July 2022, McLennan Design merged with global architecture and design firm Perkins&Will to accelerate and scale up decarbonization. One of the world’s leading multi-disciplinary regenerative design practices, McLennan Design focuses on deep green outcomes in the fields of architecture, planning, consulting, and product design. The firm uses an ecological perspective to drive design creativity and innovation, reimagining and redesigning for positive environmental and social impact.

Founded in 2013 by global sustainability leader and green design pioneer Jason F. McLennan and joined by partner Dale Duncan, the firm dedicates its practice to the creation of living buildings, net-zero, and regenerative projects all over the world. As the founder and creator of many of the building industry’s leading programs including the Living Building Challenge and its related programs, McLennan and his design team bring substantial knowledge and unmatched expertise to the A/E industry. The firm’s diverse and interdisciplinary set of services makes for a culture of holistic solutions and big picture thinking.

Jason F. McLennan is considered one of the world’s most influential individuals in the field of architecture and green building movement today, Jason is a highly sought out designer, consultant and thought leader. The recipient of the prestigious Buckminster Fuller Prize, the planet’s top prize for socially responsible design, he has been called the Steve Jobs of the green building industry, and a World Changer by GreenBiz magazine. In 2016, Jason was selected as the Award of Excellence winner for Engineering News Record- one of the only individuals in the architecture profession to have won the award in its 52-year history.

McLennan is the creator of the Living Building Challenge – the most stringent and progressive green building program in existence, as well as a primary author of the WELL Building Standard. He is the author of seven books on Sustainability and Design used by thousands of practitioners each year, including The Philosophy of Sustainable Design. McLennan is both an Ashoka Fellow and Senior Fellow of the Design Future’s Council. Jason serves as the Chief Sustainability Officer at Perkins&Will and is the Managing Principal at McLennan Design.