February 2025

February 2025

Style as a Lifestyle

By Jenny Kwan

Tiktok: An Uncertain Future

By Milena Garrone

Sticking Together

By Alexander Mangot

The Lowell February 2025

Editors-in-Chief

omas Harrison

Ramona Jacobson

Katharine Kasperski

News Editors

Kai Lyddan

Maren Brooks

Multimedia

Editors

Imaan Ansari

Katharine Kasperski

Yue Yi Peng

Art Manager

Yue Yi Peng

Reporters

Danya Bayer

Miles Bernson

Audrey Brogno

Cecilia Choi

Amálie Cimala

Herschel Diamond

Kai Dohrrman

Aida Donahue

Milena Garrone

Nisha Halfen

Jenny Kwan

Stephanie Li

Serena Miller

Jeremiah Moses Skyler

Sophie Murphy

Kate Schoeller

Stella Schulte

Mehreen Shaikh

Charlie Steinberg

Accolades

NSPA Pacemaker Top 10

Uma Van Yserloo

Ethan Win

Kristin Woo

Nicholas Xie

Faye Yang

Jada Zeng

Photographers

Christopher Hernandez

Dakota Colussi

Alex Hohn

Sydney Lee

Alex Mangot

Hannah Tandoc

Illustrators

Je rey Chen

Sarah Cuaresma

Cayce Hewitt

Noelle Mak

May San

Business Managers

Isabella Chan

Dena Nguyen

Web Manager

Katharine Kasperski

Social Media Manager

Anita Luo

Researchers

Maren Brooks

Anita Luo

Advisor

Eric Gustafson

2018 NSPA Print Pacemaker Finalist

2011 & 2014 NSPA Online Pacemaker

2012 NSPA Print Pacemaker

2007 & 2011 NSPA All- American

2009 NSPA First Class Honors

2007 NSPA Web Pacemaker

2007 CSPA Gold Crown

The reason students go to school is fairly straightforward; they want to learn. is should mean that teachers want to teach students and equip them with the knowledge necessary to succeed. However, many teachers at Lowell instead choose to utilize an approach reliant on textbooks, workbooks, and other similar resources instead of their own knowledge. Because of this awed style of teaching, many devoted students rely on excessive out-of-class research and tutorials on sites like YouTube to compensate for the lack of instruction they receive in class. While there are still many teachers at Lowell who treat teaching with passion and the proper level of care, lots of them can display carelessness towards their classes, which can detrimentally a ect the academic success and mental health of students.

While it is common for teachers to use textbooks to assist with lessons, a common issue among teachers is an overreliance on these resources. While it is particularly notable in math classes, this issue is present in various subjects taught at Lowell. Many geometry teachers rely heavily on the standard geometry textbooks, and their lesson plans o en consist of doing page a er page of the textbook without providing much explanation of the material. is learning method leaves students in an undesirable position, as they are forced to study pages of the books every day without receiving additional instruction or guidance. For students who learn better in more interactive environments, with more teacher-student collaboration, this teaching method is unhelpful and can make the class more di cult than it needs to be.

When teachers don’t provide students with direct instruction or allow them to experiment with new concepts, it can negatively affect the stress levels and workloads of the students.

When teachers don’t provide students with direct instruction or allow them to experiment with new concepts, it can negatively a ect the stress levels and workload of the students. As teachers fail to provide students with an adequate amount of useful instruction, students can begin to feel overwhelmed. is is because the amount of content in their classes increases as the year progresses, which consequently leads to a greater amount of misunderstanding. Since they aren’t going to class in a productive learning environment, students can get stressed out about not understanding the topics enough to perform well on exams. To make matters worse, high school students also struggle with reaching out for support when they need it. According to Edutopia, just 40 percent of high school students in

the U.S. feel that they have an adult that they can turn to when they are stressed. is feeling of isolation eventually leads to underperforming on assignments and tests, which only worsens their mental health. Despite the seemingly complex nature of this issue, it is fairly safe to say that students would feel more comfortable reaching out to their teachers for help if they felt the presence of their teachers in the classroom more. e lack of available support can also force students to essentially teach themselves the lessons outside of school, relying on resources such as YouTube and Khan Academy to teach them topics that should be the responsibility of their teachers. While YouTube and other resources are helpful to have for students who want to go above and beyond and get extra guidance outside of the classroom, many students are feeling the need to use it regularly to supplement the lack of instruction on their teachers’ part. Relying on these self-instructional methods can cause students to become overwhelmed and stressed, as they can feel high amounts of pressure to learn materials that their teachers haven’t gone over. Another issue with this overreliance on workbooks, albeit a smaller one, is that it forces many students to bring large, heavy textbooks to school every day. Some students at Lowell don’t have access to lockers, forcing them to carry around all the materials they need throughout the entirety of their day. Bringing textbooks to class every day can result in students carrying around heavier bags than necessary. To combat this, teachers should have set days where students are required to bring their textbooks, rather than requiring them daily. During the rest of the week, teachers can rely on other teaching methods such as experiments, lectures, and seminars. ese teaching methods would be less stressful and more relaxing for students, and would be far more bene cial for their learning, as they would get a balance of learning from the textbooks combined with other methods.

By incorporating di erent teaching styles into their curriculums, teachers can raise student grades and participation while having an easier time keeping their attention during class. With students more eager to learn and teachers more committed to their work, the classroom environments will see a noticeable improvement. All it takes to get there is for teachers to adapt new lesson plans and implement more variety, rather than always resorting to textbooks to teach their students.

Dear readers of e Lowell,

Happy new year! is semester, we welcomed 20 new reporters from the Journalism 1 class into our publication. Right o the bat, they have brought many strong ideas to the table, and have written thoughtful pieces for this issue of the magazine — for example, Uma Van Yserloo and Stella Schulte with their opinion piece about the harmful impacts of the use of the R-word, Aida Donahue with her media review of Arrival, and Danya Bayer with her work on our cover story about teenage pornography consumption. ese reporters, along with the rest of our new sta , have been hard at work making content for our publication, and we can’t wait to see what they create in the future.

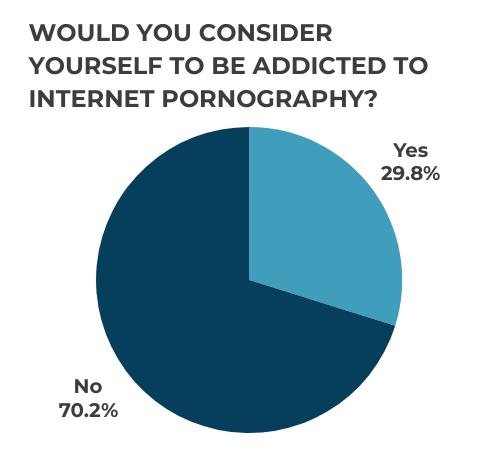

In this issue, we decided to cover a topic we believe has not been addressed nearly enough. ough an uncomfortable subject, pornography consumption is prevalent among Lowell’s student population; according to a survey conducted by e Lowell in January 2025, 23 percent of respondents regularly consume internet pornography. We were surprised to learn just how much of a negative impact pornography is having on the lives of our peers, and we hope that this article can provide some insight into this issue.

Editors-in-Chief, omas Harrison, Ramona Jacobson, and Katharine Kasperski

e Lowell is published by the journalism classes of Lowell High School. All contents copyright Lowell High School journalism classes. All rights reserved. e Lowell strives to inform the public and to use its opinion sections as open forums for debate. All unsigned editorials are opinions of the sta eLowellwelcomes comments on school-related issues from students, faculty and community members. Send letters to the editors to thelowellnews@gmail.com. Names will be withheld upon request. We reserve the right to edit letters before publication.

eLowellis a student-run publication distributed to thousands of readers including students, parents, teachers, and alumni. All advertisement pro ts fund our newsmagazine issues. To advertise online or in print, email thelowellmanagement@gmail.com. Contact us: Lowell High School 1101 Eucalyptus Drive San Francisco, CA 94132, 415-759-2730, or at thelowellnews@gmail.com.

It’s time to talk about pornography and its negative impacts on the Lowell community.

By Thomas Harrison and Danya Bayer

Elizabeth, a senior under a pseudonym, was just seven years old when she began watching internet pornography. Having never been exposed to sex before, she became curious to learn about something that she saw as mature and for adults. Soon, she was habitually exposing herself to videos full of violent sex and objecti cation that would go on to change her perception of sex for the worse. Elizabeth is 18 years old now, and though her enthusiasm for porn has long faded, she continues to watch it on a regular basis, attempting to chase the excitement it gave her as a child.

Elizabeth, like several other Lowell students, has been negatively impacted by pornography consumption.

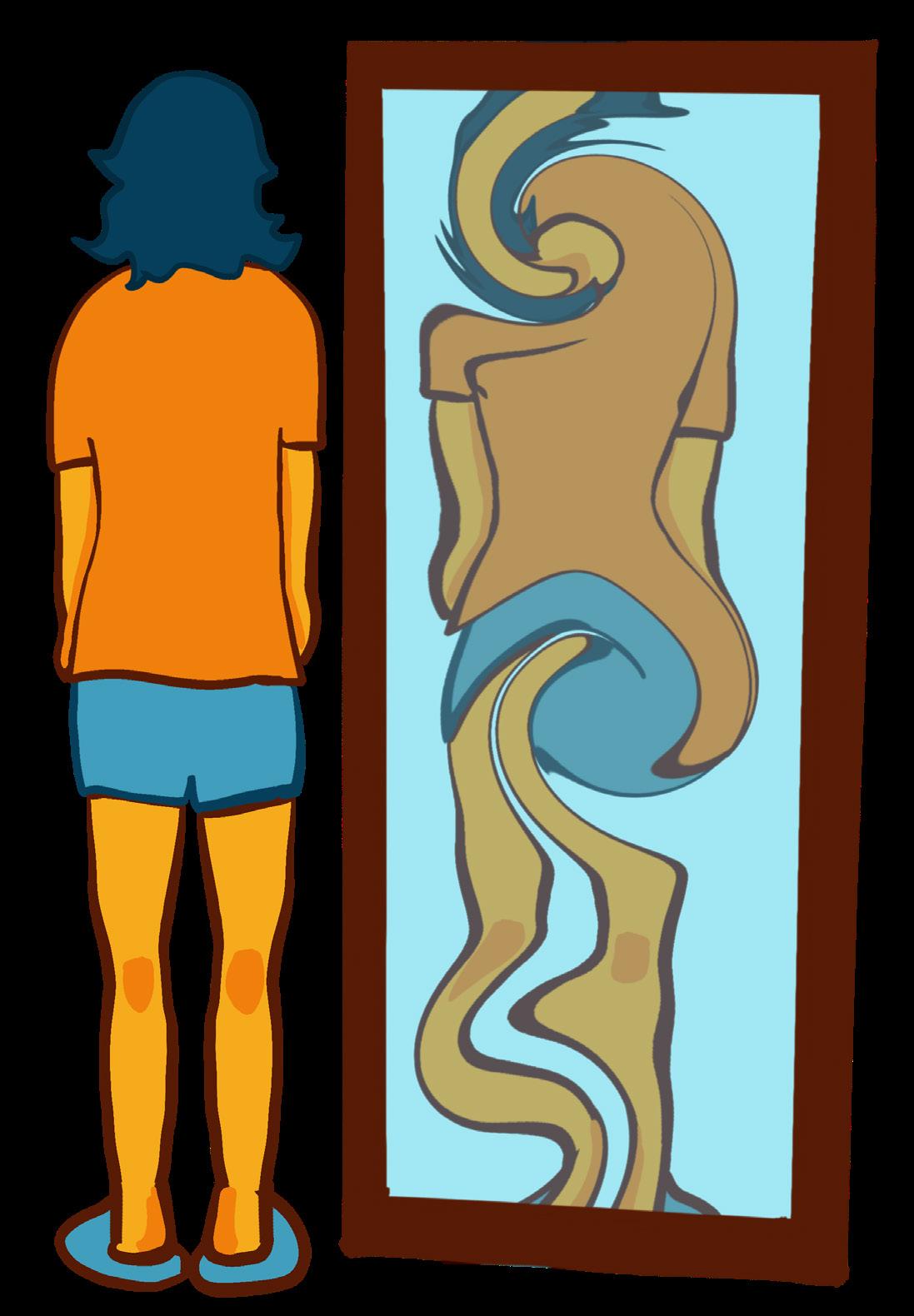

e growing accessibility of internet pornography has caused issues for Lowell students. Many students have grown up watching porn from a young age, causing them to have warped views of sex or women. Some Lowellites have developed addictions to internet porn, which eat away at their time, freedom, and self respect. Although students like Elizabeth have grown aware of its impact, some nd it hard to move past the habits and ideas that porn has forced on them.

Pornography o en depicts women in degrading ways, which can seep into consumers’ views of women and sex. In Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality, Gail Dines, Wheelock College’s professor emerita of sociology and women’s studies, writes that porn desensitizes men to violence against women through “gonzo sex,” which she de nes as “hard-core, punishing sex in which women are demeaned and debased.” According to Dines, this “gonzo” porn o en shreds the humanity of the women depicted in it. “ e rst and most important way pornographers get men to buy into gonzo sex is by depicting and describing women as fuck objects who are deserving of sexual use and abuse,” Dines writes. is is o en done by putting these women through extreme, embarrassing, and sometimes painful sexual acts, most of which focus little on the woman’s enjoyment of the

act compared to the man’s. Although many are aware that these depictions of sex are unrealistic, Dines claims that pornography can cause its consumers to expect or seek out these experiences during real sexual encounters. “Men may think that the porn images are locked in that part of the brain marked fantasy, never to leak into the real world, but I hear over and over again from female students how their boyfriends are increasingly demanding porn sex from them,” Dines writes.

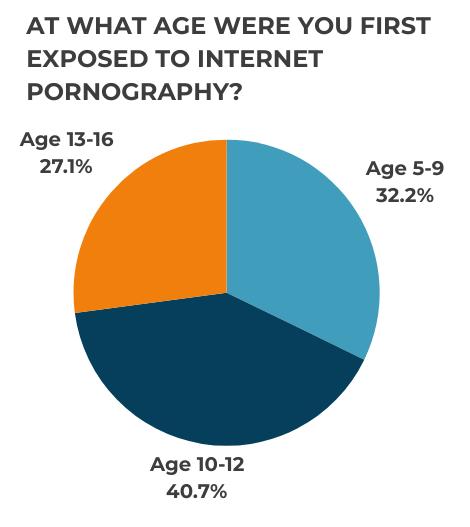

Experts worry that the rise of internet pornography has made our current generation of teenagers more vulnerable to this “gonzo” pornography than ever before. “Before the advent of the internet, it used to be that men sporadically used porn when growing up; it was the more so -core type of porn, and they o en had to steal it,” Dines writes. “While past generations of men who used porn had limited access to the material, this generation has unlimited access to gonzo porn.” is is especially relevant due to the young age at which people are watching internet pornography. In a January 2025 survey conducted by e Lowell of 173 students, 23 percent of students said that they consume internet porn on a regular basis. Out of the 59 students who provided the age at which they began watching pornography, 27 percent said that they were rst exposed to internet porn before the age of nine, and 72 percent were rst exposed before the age of 13. According to the peer-reviewed journal Handbook of Children and Screens, adolescents without sexual knowledge or experience may lack

a frame of reference for the topic, causing many to believe that porn is representative of real world sexual activity. In her TED talk How the Evolution of Porn Changed Adolescence, which she authorized e Lowell to use, Dr. Megan Maas, an assistant professor in Human Development and Family Studies at Michigan State University, shines a light on how little most students know about sex prior to being exposed to pornography. “Only 24 states actually mandate sex education in schools, and of those, only ten require that it be medically accurate,” Maas said. “Only nine require a discussion of consent, and zero require a discussion of pornography or pleasure.” In e Lowell’s January 2025 survey, over 62 percent of 60 participants who answered an optional question considered internet porn to be their rst signi cant exposure to sex, with 32 percent of 56 respondents of another optional question reporting that pornography had impacted their expectations surrounding sex. According to experts,

that impact is profoundly negative, especially with boys. “Unlike before, porn is actually being encoded into a boy’s sexual identity so that an authentic sexuality — one that develops organically out of life experiences, one’s peer group, personality traits, family and community a liations — is replaced by a generic porn sexuality limited in creativity and lacking any sense of love, respect, or connection to another human being,”

[thought that] they’re doing something they both like.” It wasn’t until around age 14 that Meredith began to question what she saw. “I started noticing that I couldn’t tell if the girl was in pain or not, or if it was consensual or not,” she said. “[Noticing] the fact that we couldn’t even see the guy, but we could see this girl’s whole face and body, is when I realized [it].”

Although not everyone will

that the guys are dominant and the girls sometimes, in some videos, want to be treated like that.” Although Veronica, a senior under a pseudonym, initially felt uncomfortable about this aggression towards women, she grew more used to it the more porn she consumed. “I feel like at the beginning, I was a little bit like, why are you doing that? Why would a woman let a man do that to her?” she said. However, her exposure to this ag-

“I started noticing that I couldn’t tell if the girl was in pain or not, or if it was consensual or not.”

Dines writes.

ese warped expectations are especially detrimental to students’ perceptions of a woman’s role in sex. Many students said that pornography had caused them to internalize the idea that sex was focused around pleasuring a man, and that women were supposed to be submissive to men during sex. Henry, a senior under a pseudonym, believes that porn promotes the idea that sex is about women letting things happen to them, rather than taking on a more active role. Similarly, Meredith, a junior under a pseudonym, feels that heterosexual porn is made solely to cater towards men, with no attention being given to the perspective of women. She claims that most pornography is lmed from a perspective that allows male viewers to imagine themselves engaging in intercourse with the women depicted in the videos, leading to the women in the videos being objecti ed in a way that the men in the videos aren’t. “ ey’re turning a woman into an object to be watched, to be lusted a er, and they don’t really do the same towards men,” she said. “When I was young, I don’t think I fully grasped the concept of misogyny yet, so I just

seek out especially violent content, aggression towards women is so common in porn that many students have grown used to it. Out of the Lowell students surveyed, over 40 percent of those who watch pornography reported watching pornography containing real or staged physical or sexual violence towards women. Elizabeth can recall an especially aggressive video that in uenced her idea of a woman’s role during sex.

gression increased with each pornography video she watched, and she began to relent. “I’ve kind of accepted it,” she said.

Because porn caters so strongly to male pleasure, it can make sex seem less appealing to women. Elizabeth has become uninterested in the idea of having sex with men altogether. “I think because I watch porn, I don’t really want to have sex,” she said. “I see it as being for the man. It doesn’t seem like it’s for the woman’s pleasure… It’s not very fun.”

“I remember watching some a while ago where [the man] tied [the woman] up and fucked her, and it gave me this idea

Porn has caused Elizabeth to see women as having a set role during sex, and doesn’t associate the idea of sex with having her sexual desires fullled. is has drawn her to the idea of lesbian sex, despite Elizabeth herself identifying as a straight woman. “I guess it’s appealing because there’s no man involved,” she said. “Being able to do the same things on another person that you can do with yourself, and having someone recognize what you need in sex… at seems appealing, I guess.”

Similarly, Meredith takes issue with porn’s lack of emotional connection, which she sees as essential to a positive sexual experience. “[In porn], there’s no communication

“My brain just got used to what it was given at the start, which was pretty heavy already, and then it just wanted more.”

and there’s no a ercare,” Meredith said. “You’re not talking to the person about what you like or what they like.” She feels that communication and consent are downplayed in most pornographic content, and worries about the impact that could have on viewers’ perceptions of sex. Meredith recalls her friends talking about a lack of communication in their rst sexual experiences, as their partners didn’t take the time to ask questions or discuss boundaries with them. “It was very fast and it was kind of harsh, and I feel like that could be tied to porn consumption. e most important part of sex is love, I think, and that’s what porn completely diminishes.”

Porn’s “gonzo” depiction of sex has led students to have issues in their own sexual experiences. Henry feels that his exposure to the unrealistic depictions of sex in porn has made it di cult for him to perform in sexual situations, which makes his partner feel insecure. “ ey think that it’s the fault of their performance, when it’s mine,” he said. Consuming pornography has caused Meredith to feel that there are high expectations for her performance during sex. “ e girls are always feeling pleasure, they’re making noises and stu

like that,” she said. “It’s very exaggerated. I feel like I have to do those same things, even if it doesn’t feel that good…I feel like I have to fake it myself sometimes.” Veronica believes that watching pornography from a young age has caused her to develop stronger, o en unwanted sexual thoughts, and describes herself as hypersexual as a result of this consumption. “I think my brain chemistry has been altered because of it,” she said. “I oversexualize everything. and I do it subconsciously. I don’t even realize I’m

doing it.” She says that sexual situations constantly appear in her head, and she struggles to get rid of them, recalling a

situation where she was unable to focus in class because she was thinking about sex. She also frequently imagines herself in sexual situations with her peers, even when she doesn’t feel any sexual attraction towards them. She feels that these thoughts are o en out of her control, and is ashamed when she recognizes the implications of her actions. “If I think about someone doing that to me, I would be really disgusted,” she said. “So I’m disgusted by the fact that I do that to other people.”

Despite these issues, many Lowell students nd it hard to shake their porn consumption habits. Out of the students in the survey, over 29 percent of the 58 who responded to an optional question consider themselves to be addicted to porn. “ ere’s a dopamine rush when I’m watching it,” Veronica said. “It’s like when you’re scrolling on TikTok or something, [I feel like] it has the same e ect on your brain.” Veronica o en loses sleep by staying up late to watch pornography, and feels that she lacks the self-control to stop herself from consuming this content. “[Pornography is] pretty detrimental to mental health, I’d say,” she said. “If all you’re looking forward to is watching stupid fucking porn, it just feels weird.” Although Meredith no longer watches pornography, at the peak of her addic-

tion she was watching it on an everyday basis. “Around COVID, I would watch it every day, not even for pleasure, just out of pure interest,” she said. Henry compared his pornography addiction to a drug addiction, in the sense that the more he consumed, the higher his tolerance became, making him turn to more intense content in order to receive that same hit of dopamine. “My brain just got used to what it was given at the start, which was pretty heavy already, and then it just wanted more,” he said. For Henry, this meant seeking more niche, extreme, and unrealistic porn categories to satisfy his cravings, including BDSM, a sexual fetish involving uneven power dynamics and, in some cases, physical violence towards women. Although he has tried multiple times to stop watching porn, his cravings for dopamine have kept him coming back. Some students have continued watching porn despite feeling negatively about themselves for it. “[Porn] has lowered my self-esteem, making me feel really guilty,” an anonymous survey respondent said. “I always think, ‘What would others think about me if they knew this part of me?’”

is signi cantly more intense than the porn of previous generations. Meredith doesn’t think she would have thought about dangerous acts like choking as sexual if she hadn’t seen them in pornography, and believes that porn had made dangerous things seem normal to her younger self. “[Porn] normalized things that I wasn’t necessarily supposed to see, which only made me more curious… ings that could be harmful to myself if I were to put myself in that situation,” she said. Elizabeth recalls

“The most important part of sex is love, I think, and that’s what porn completely diminishes.”

seeing an excess of videos focused on inappropriate dynamics, such as incest and inappropriate age gaps. “Even just scrolling, you’ll see ‘new 18 year old girl’ or something like that,” she said. As someone who has recently turned 18, these videos make Elizabeth especially uncomfortable.

Experts agree that discussing sex and pornography in class is necessary for young people to develop a

doing the education for us,” said Maas. “We won’t like those results any more than if we let the fast food industry educate them about nutrition and eating.” For some students, watching educational content about porn helped kickstart realizations about the impacts of pornography on their own lives. For example, Veronica did not recognize that she had a porn addiction until she saw a TED talk on YouTube describing what that meant. She considered the video to be a wake up call, allowing her to re ect on her porn consumption habits for the rst time. As another supporter of stronger sex ed curriculums, Dines has held discussions in which young adults were successfully pushed to reevaluate their own relationships with porn in a classroom setting. “In the decidedly nonsexual arena of a college auditorium, men are asked to think about what [pornographic] images say about women, men, and sexuality,” Dines writes. “Stripped of an erection, men are invited to examine their porn use in a re ective manner while thinking seriously about how images seep into their lives.”

According to experts, there is a direct link between the growing accessibility of porn and the growing intensity of its content. According to Dines, the easy accessibility of internet porn has forced pornography studios to produce increasingly extreme content to appeal to viewers in a competitive market. “As the market becomes saturated and consumers become increasingly bored and desensitized, pornographers are avidly searching for ways to di erentiate their products from others,” Dines writes. As a result, teenagers like Henry are being exposed to pornography that

healthy relationship with sex and with women. “I am afraid that if we continue to ignore what’s going on in teens’ brains and their bodies, and we do not give them the education that they need, then the porn industry is going to be

Because internet pornography is so available, students have been encountering extreme content at young ages. is has long-term impacts on their perception of sex and relationships. As someone who began consuming pornographic content at age nine, Veronica hopes that future youth won’t be impacted in the same way that she was. “I don’t want them to have their expectations set that this is what a woman should do, that this is what a man should do, that this is what sex should look like, that this is what you should look like,” Veronica said. “I feel scared for them because I don’t want them to be scarred. I think I kind of was.”

Lowell February 2025

In a high-stress environment like Lowell, students need an outlet to destress and self-express. Here is what four Lowellites do in their free time.

“Tere’s no constraints on what you must create.”

“I believe there’s something for everybody in the Pokemon communit.”

“To me, LEGOs are a great way to learn as a kid and to relieve personal stresses as an adult.”

“Building custom keyboards is a very rewarding hobby in my opinion.”

By Ramona Jacobson and Maren Brooks

Some Lowell students struggle to access effective methods of travel in San Francisco, facing issues with the efficiency of public transit or unable to utilize alternative forms of transportation.

Junior Jack Ryan Fernandez Yambao rushes to leave Lowell’s campus after school, anxiously checking bus schedules in the hope that he will be able to reach the Mission District in time to pick his sister up from school. Without consistent access to a car, Yambao relies on public transportation as his primary method of traveling around the city. He had promised his parents that he would arrive on time, but as his bus becomes increasingly delayed and his commute lengthens by the minute, this begins to seem impossible. Worrying about his sister being le at school and dreading his parents’ reaction to his now inevitable late arrival, Yambao wishes that he had an easier and more e cient way to commute across the city. Yambao is one of many Lowell students who, whether by choice or necessity, rely on forms of transportation other than driving to travel within San Francisco.

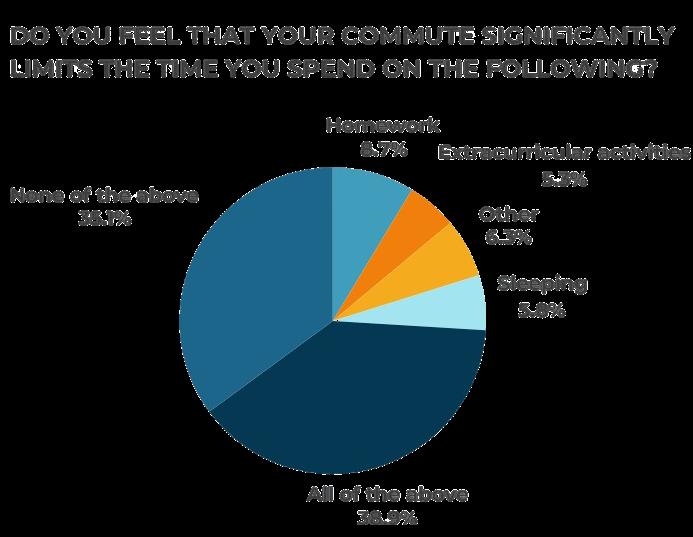

Some Lowell students struggle to access e ective methods of travel in San Francisco, facing issues with the e ciency of public transit in their neighborhood or lacking the resources necessary to utilize alternative forms of transportation. While driving can save time and reduce the di culty of students’ commutes, many students don’t have consistent access to a car. Long commutes, which can be caused by factors including long distances to transit stops or delays in service, can detrimentally impact students’ lives, limiting the time that they are able to spend on schoolwork and other activities. is issue creates unique challenges for students who use public transportation by necessity, and budget concerns faced by San Francisco’s public transportation providers could introduce greater diculties for the many city residents who rely on it.

According to a survey administered by e Lowell in January 2025, 64.9 percent of respondents said that their commute signi cantly limited the amount of time they are able to spend on activities including homework, extracurriculars, spending time with friends, and sleeping. Although the convenience and e ciency of transit routes varies for students living in di erent

Lowell February 2025

areas of San Francisco, public transportation is still the primary resource that many students depend on to navi-

gate the city. As a result, many students must rely on an unpredictable schedule of buses and trains to commute, cutting into the amount of free time they have outside of school. San Francisco is unique for its widely used networks of public transportation. e San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) and Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) lines are extensive enough to theoretically allow residents to travel to all areas within the city. In 2013, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA)’s Free Muni for Youth pilot program was introduced, providing free transportation to all riders aged 18 or under and making Muni even more widely accessible to students. e program was put into e ect permanently in 2015.

Despite these bene ts, San Francisco’s public transportation system is not free of issues. Sophomore Phoenix McNab, a member of the Lowell Transit Club who expressed mostly positive views on San Francisco’s public transportation, acknowledged its problems. “ e frequency [of buses] is not enough,” he said. “If they added more frequency, then it would probably be a lot better.” Senior Daisy Meeks feels that transit reliability issues, such as buses failing to arrive on schedule or leaving riders waiting for extended periods of time, can create stress and uncertainty for public transportation users. “You can’t always rely on [transit],” she said. “Sometimes you really need it to come at a certain time and it doesn’t.” Junior Otto Krause feels that he has recently observed changes with the ease and

accessibility of public transit. “Costs are going up, reliability is going down, and it’s making it hard for people to get around,” he said.

Despite the SFMTA’s e orts to provide accessible services for youth across San Francisco, some students face far longer commutes than their peers. Yambao, who relies on Muni to travel to school and work, experiences di culty with extended trip times from his home located between the Mission and Potrero Hill neighborhoods. According to Yambao, he feels that the signi cant length of time he spends commuting on public transit takes time away from other areas of his life. “Having to work around [the commute time] when it comes to extracurriculars and at-home responsibilities, plus work and schoolwork, is de nitely a limiting factor,” he said. “Trying to balance a lot of things with something so unpredictable can be really inconvenient.”

Yambao feels that his commute reduces the range of opportunities, such as jobs and extracurriculars, that he is able to pursue. He has his driver’s license, but does not have full-time access to the family car. As a student uses public transportation by necessity, Yambao has a signi cantly longer commute in comparison to some with full access to a vehicle. “I think that if I was able to get a car or use a car more o en, it would

allow me to [use that time] more,” he said.

Overcrowding, inconsistent timing, and other transit challenges are especially prevalent on the 29 Sun-

set bus, which many Lowell students take. According to a survey conducted by e Lowell in January 2025, 49 percent of student respondents said they take the 29 bus. Both Meeks and junior Sylvia Nickolopolous expressed di culties with this bus line, citing unreliable service and consistent overcrowding. “It can be really crowded, and every once in a while, it will not come for a long period of time, and then I have to be late to school,” Meeks said. Nickolopolous has also experienced the 29 buses becoming crowded with students. “It’s a clown car situation,” she said.

According to SFMTA Transit Planner Adrienne Mau, the SFMTA is aware of students’ challenges with the 29 bus line. In 2019, responding to feedback from community members, the organization began developing the 29 Sunset Improvement Project. e project aims to reduce delays and long wait times for 29 bus riders, as well as reducing “pass ups,” when people are not able to board because the bus is too crowded. e project is set to be implemented in stages, and the majority of its planned changes have yet to take e ect.

As a 29 bus rider, McNab has not yet seen the full impact of the project on the bus line. “I’ve seen improved frequency, which is good, but other than that, not much,” he said. “What they really need to do is implement a 29 Rapid bus, but they need funding for that.” Nickolopolous has similar ideas for improving the bus line’s e ectiveness. “I think that two-car buses, just adding more space, is a great solution,” she said. In addition to these issues, the SFMTA is navigating nancial di culties that could bring changes to service and accessibility in the coming years. e SFMTA is currently facing a nancial de cit that is projected to grow into a budget gap of hundreds of millions of dollars, the e ect of a combination of nancial troubles le over from the COVID-19 pandemic and high rates of in ation. According to Mau, the SFMTA’s budget crisis has the potential to exacerbate any existing issues with the access and availability of Muni buses in San Francisco. “ ere’s these worst case scenarios, like [if] we have to signi -

cantly reduce transit service on certain lines,” she said. “Federal requirements require agencies to keep lifeline lines running, but that might still mean longer [wait times], meaning, instead of 10 minutes, it could be 15 or 20 minutes until you see a bus, or it might stop short at a certain location and then you

have to transfer somewhere else.” Mau emphasized the SFMTA’s commitment to providing essential and equitable transportation access to all San Franciscans. “We have this equity viewpoint, [where] we ensure that communities who don’t have any other way of getting around aren’t disproportionately a ected,” she said. “Schools are also top of mind, to ensure that students are able to get around.”

Some students who don’t drive seek out travel alternatives beyond public transportation. Senior Olivia Santos bikes to school every day, choosing this option above public transit due to its convenience, time e ciency, and environmental bene ts. “It takes me the exact same amount of time to bike to school as it does to take the train, but the di erence is that I leave my house and I am on my way to school. I don’t stand at Church Station for 20 minutes waiting for the train to come,” Santos said. “Biking allows me to actually get to school on time.”

Although Santos feels that she is able to access safe bicycle routes within her Duboce Triangle neighborhood, she wishes for more bicycle safety infrastructure within the city as a whole. “[San Francisco needs] more protected

bike lanes, because even when there’s a designated bike lane, there are always motorcycles, there are always cars,” she said. Santos feels that some San Francisco drivers dislike bicyclists, having experienced aggressive and incautious behavior from drivers while bicycling. “[I feel like] there’s not a single person on the road who has any love at all for a bike,” she said. “Like, why? I’m on a bike and you’re in a massive vehicle.”

According to Mau, the SFMTA is currently working on projects to improve bicyclist and pedestrian safety in San Francisco. “In 2014, we established our Vision Zero policy citywide, focusing aspirationally on [achieving] zero vehicle tra c-related deaths in the city,” she said. e Vision Zero policy has provided the SFMTA with an avenue to begin street safety projects for bicyclists and pedestrians, namely the Vision Zero Quick Build Program, which quickly implements safety improvements in areas with high rates of pedestrian and bicycle injuries. “Since the inception of our Quick Build program, which was around 2019, we’ve completed 50 miles of Quick Build tra c safety projects throughout the city, which also means that we’ve rolled out a considerable amount of protected bike lanes,” she said. “We have these tools now, and the support from our SFMTA Board, to really get that protection.”

San Francisco’s public transportation networks are an essential service for Lowell students. Krause believes that e ective and a ordable transportation options are a necessity, and feels that the city’s transit resources have the capacity to continue improving. “It helps low income families get around San Francisco,” he said. “If public transportation is reliable, it’s a very helpful solution.” Mau encourages students to continue reaching out to the SFMTA with comments or concerns about their public transportation experiences. “[We want to] connect with students and community groups about the work that we’re doing,” she said. “We want them to see us as people, rather than just the city government. ere’s so many di erent ways to get involved, [and] di erent ways to make your concerns noted.”

By Amálie Cimala

The Czech Republic does not exist,” blatantly stated my rst-grade classmate. “What do you do there, just check boxes?” Heat rushed to my cheeks, and I felt a sense of embarrassment associated with my ethnicity that I had not yet encountered before. Sharing my annual summer plan of visiting my family in the Czech Republic to my seven-year-old peers ended up sparking an identity crisis that would last nearly a decade. I had never been ashamed of my ethnic and cultural background before, but suddenly everything shi ed: I had realized how di erent I was from my peers.

Both of my parents were born in communist Czechoslovakia, when it was still part of the Soviet Union. When she was nine, my mom ed the country with her mother to join my grandfather in America. He had le years prior, when my mom was born, to escape political turmoil. Later, a er the regime fell, my father joined my mother in the United States a er they got married (they had met during a summer she was visiting). I grew up with stories of my parents’ relatives being thrown in prison for expressing anti-communist ideas, and seeing the lasting impact my family’s history le on them. As a young child I admired their bravery and strength, and was always eager to share their stories with my classmates. However, as I got a little older, namely around rst grade, my unique heritage became something that made me weird instead of cool. Before this, my classmates found my bilingualism impressive (we spoke Czech at home) and envied my summers spent in the Czech Republic (my parents kept a house there). is sudden shi led me to attempt to erase that part of myself in pursuit of being able to t in and be liked.

more di cult. Unlike other rst generation children in San Francisco, I had no sense of community: I didn’t know any other Czech people in the city outside of my parents, grandparents and brother. I felt isolated, and since I had no one to lean on, my relationship to my ethnicity and culture became a struggle I faced alone.

My rst language is Czech; I didn’t learn English until I started preschool. I was almost oblivious to American pop culture and was o en unfamiliar with the shows and movies my classmates and friends o en referenced. While my parents incorporated American media into our household, I felt frustrated that none of my friends could understand the cartoons and characters I loved and watched every day. I felt alienated from my peers, so I turned to the most logical solution at the time: become as Americanized as possible in the hopes of tting in. I believed that if I consumed American media instead of engaging with my Czech roots, I could nally blend in. is was an era of my life popu-

Not only do I accept my

I pride myself on it.

Before starting at Lowell, I attended a small private school. Most students were of Asian or Irish origin, so my Slavic background made me stand out in a school where it was essential to blend in to avoid getting teased. I was constantly getting picked on for the ethnic food I brought, characters I liked, and how I would accidentally say something in Czech instead of English. Not having a friend who was also Czech made this even

lated by my own cultural cleansing, and repression of my ethnicity. I never brought up being Czech in fear of being pretentious, and swore myself to never mention any Czech shows or characters because I felt my peers would never understand anyway. Even worse, in my eyes, they already saw me as “weird.” I refused to bring cultural dishes to school, ever since I got told that my Guláš (Czech beef stew) smelled bad by a classmate during lunch. If I ever slipped up and accidentally said something in Czech instead of English, I felt ashamed; I didn’t even want to be bilingual. is sense of shame lasted from rst grade until the beginning of high school. Even at my peak of Americanized identity, I was not content. I felt plastic, like I was purposefully hiding something, yet at the same time ashamed of hiding it. While I was shi ing away from my culture, my older brother was moving in the opposite direction. He had changed

the default language on his computer from English to Czech, in an attempt to get more familiar with reading the language. He started borrowing Czech books from my dad, falling in love with old Czech rock, and sharing Czech memes with his American friends. Peering into his uorescent laptop screen, I felt embarrassment ood me, as I could not read a single word in Czech. In the attempt to be liked by people I myself didn’t even like or want to embody, I had completely lost myself and my Czech-American identity, which had once made up the core of who I was as a person. e realization of that moment was so potent, it altered my mindset forever. e summer before my sophomore year, I spent my annual two and a half months in the Czech Republic with my family. My earlier realization had sparked a re within me to reconnect with my ethnicity and culture like never before, and being in the best place to express it only let that desire burn brighter. I did everything I could to learn to read Czech, and found myself at peace in the place I had blamed for my misery. While it was not an easy thing to accept, I realized that the only way to face my deeply rooted insecurity regarding my ethnicity was to reconnect with it, face it, and accept it instead of being averse to it. Although my connection to America and the English language is stronger than my one to the Czech Republic and its language, I am proud of how far I have come, not only in literacy, but in the strong sense of love and appreciation I have for my ethnicity and culture. While I don’t think that I will ever feel as though I completely belong in America, or the Czech Republic, I nd myself comfortable in my Czech-American identity. I no longer believe that my ethnicity is something that makes me weird. Actually, it allows me to empathize with others who share similar experiences. Not only do I accept my Czech-American identity, I pride myself on it. It is something that I no longer wish to hide. Instead, I showcase it and display it for everyone to see. So to my rst grade classmate: the Czech Republic does, in fact, exist, and every day I wake up proud of my connection to it.

BY AIDA DONAHUE

Denis Villenueve’s 2016 lm

Arrival is a love letter to language. rough its layered storytelling, it examines the complex interactions between communication and understanding. e movie focuses on contact with aliens, a trope it uses to explore the idea that the language we speak can in uence our perception of the world, extending even to our concept of time. e lm follows Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams), a renowned professor of linguistics living a quiet existence up until the U.S. military enlists her in the global e ort of establishing communication between mankind and an alien species. Without warning or explanation, the aliens, called heptapods, descend on Earth in 12 separate vessels that disperse across the globe. eir arrival creates international tensions as governments work to respond, while Banks strives to bring the aliens and hu mans together

of linguistic relativity, the idea that the language we speak impacts our overall outlook on life by changing the way that we process it. rough interacting with the aliens, Banks develops a newfound understanding of chronology, one completely di erent from standard human comprehension.

that they’re attempting to make effective contact with the aliens. Governments across the world struggle to collaborate in addressing the heptapods’ arrival, creating con ict and misunderstanding. e challenges

In learning the heptapods’ language, Banks inherits the aliens’ perspective. Heptapods don’t view time as linear, and this is re ected in the way they write, through circular logograms. Instead of an alphabet, they use singular symbols to express entire ideas. As Banks works to understand the aliens’ language and expression, their nonlinear understanding of time begins to in uence her own memories and perceptions. Scenes vary between present and future, enhancing the emotional dimensions of the story by delving into her personal experiences in disjointed, seemingly unrelated sequences. While this creates a somewhat confusing plot progression, it proves to be integral to the story. Only when the true motives of these aliens have been revealed do we learn what these interspersed memories and experiences mean to the story. e human characters in Arrival seem to face the most significant di culty in communicating with each other, which is ironic given

to communication between the human characters serve as a criticism of humanity itself in our inability to function as a collective, peaceful unit. e movie portrays mankind in the harsh truth of its dysfunctionality, providing a sharp contrast to the heptapods’ calm, knowing natures. e science ction genre is sometimes dubbed inaccessible in its attempts to bring complex concepts into the lens of storytelling. With theories, species, kingdoms, planets, space shuttles, and more, the world of science ction can be complex and confusing, driving away some viewers. Arrival is a far less alienating example of the genre. In it, people become more human by learning an extraterrestrial language, which is not only more inviting to science ction skeptics, it’s genius. is depth makes it an enjoyable work of art, taking nothing away from its credibility as a brilliant piece of science ction.

BY STELLA SCHULTE AND UMA VAN YSERLOO

As Violet, a student under a pseudonym, scanned the test paper that had just been returned to her for a score, she overheard her tablemates bickering. “How’d you do so bad on that test? What are you, r*tarded?”

Immediately, she became uncomfortable, recognizing the unkind and o ensive attitude that many of her classmates held toward their peers with special needs. is was the rst of many times she would hear this word used at Lowell.

Many Lowell students seem to believe that it is acceptable to use the R-word as an insult or “joke.” Both in and out of the classroom, this o ensive slur is o en used to call someone “unintelligent,” and is so commonly used that students have become desensitized to the word. However, this slur is insensitive and derogatory, and its prevalence at Lowell harms an important part of our community. Lowell students should stop using o ensive and ableist language. We need to make our school a kinder and more compassionate environment for our peers with disabilities. For many years, the R-word was considered a socially acceptable term. It was not ocially recognized as a slur in court until President Obama passed Rosa’s Act in 2010, which banned the use of the R-word in legal documents. One could argue that because the R-word has only recently been recognized as a slur, people are still learning not to say it, and therefore, its use is not sig-

ni cantly problematic. However, the use of this word, regardless of someone’s intentions, deeply affects Lowell’s special needs community. Even when it’s not said directly to students with disabilities, the R-word makes the Lowell environment seem more hostile and unsafe for these students. For some Lowell students, name-calling and teasing their friends with the R-word has become a habit. Adrian Rizo, a Special Day Class (SDC) teacher in an autism-focused classroom, has observed the R-word used more o en between abled stu-

dents than from an abled student to a student with disabilities. is is an example of covert ableism: when people know not to be hateful directly to resource students, sometimes referred to as special education students, but will spew o ensive remarks at their friends regardless. When Rizo has observed the R-word being used at school, he says it feels as though the community has a lack of compassion and respect for resource students, even if the R-word is just being used between friends. Many resource students at Lowell say that they have not encountered any use of the R-word at school. However, there is room for improvement in making it a

more welcoming place for students with disabilities. Janna Rudolf, a teacher for the deaf and deaf-blind at Lowell, advocates for respectful curiosity, believing that asking questions with genuine interest will reduce the separation and stigma surrounding students with disabilities. “If you’re curious, stay curious, ask questions from a curious place and a respectful place,” she said. Rizo says that simply trying your best to be inclusive and mindful of your language can help resource students feel more welcomed within the school community. “It would be nice to see more of an e ort from the population,” Rizo said. “[Lowell students] aren’t experts either. We’re all just people, so I think e ort goes a long way.”

Lowell High School should be a safe and accepting community for all its students. No matter their di erences, students should respect their peers, especially those who deal with discrimination on and o campus. When one group is mistreated, it a ects everyone, creating an environment based on judgment and hostility rather than acceptance. When the R-word is used as a “joke” between friends, it diminishes its severity. e continual use of this word in a joking manner fuels the idea that it is ino ensive. In reality, the R-word is a form of hate speech that degrades and disregards people with special needs. Eliminating the use of the R-word at Lowell will create a safer, more welcoming environment for all.

Down

1. SZA’s Grammy-winning “out of this world” song

Across

4. Golden Globe-winning, tennis-centered love triangle

2. “I’ve played these games before” is from which show?

6. 2024’s very “emotional” top movie

8. “That’s that me ____”

3. is “midwest princess” blew up with her song HOTTOGO

9. Don’t forget to thank this Grammy Top Album winner ____

10. Hit show based on League of Legends

5. For the second year, ____ is the most listened to artist

11. Deadpool vs. ______

7. Former Dance Moms star turned bad girl

Across

Down

4. Golden Globe-winning, tennis-centered love triangle

1. SZA’s Grammy-winning “out of this world” song

6. 2024’s very “emotional” top movie

2. “I’ve played these games before” is from which show?

8. “ at’s that me ____”

3. This “midwest princess” blew up with her song, HOTTOGO

9. Don’t forget to thank this Grammy Top Album winner

5. For the second year, ____ is the most listened to artist

10. Hit show based on League of Legends

11. Deadpool vs. ______

12. Grammy-winning diss

7. former Dance Moms star who gained popularity with her song about being a bad girl

14. ______ green

12. 5 time Grammy-winning diss

13. Broadway musical turned movie that coined the term “Holding space”

15. This Netflix original is 2024’s Most Watched series

16. first victim of several celebrity look alike contests

Come by room S107 with your correctly completed crossword to get a baked good during blocks 4 and 5! First come, rst serve for each block!

14. ______ green

13. Musical that coined the term “Holding space”

15. is Net ix original is 2024’s Most Watched series

16. First victim of several celebrity look alike contests

Would you like to see your ad in the next issue of e Lowell?

Email eLowellManagement@gmail.com