Neighbors sound the alarm as Tweed New Haven Airport sprawls.

Dear readers,

There are a lot of ways to say goodbye. The poets have tried. Louise Bogan calls it “leave-taking.” Emily Brontë reminds us to “follow out the happiest story.” Perhaps Yvor Winters puts it best: “This is the terminal, the break.” Here we are, at the terminal of our tenure, and there’s not much else to do but wave.

This issue holds a lot of goodbyes. In our cover story, Meg Buzbee explores the pain of saying goodbye to a quiet neighborhood taken over by airport turbulence. Chloe Nguyen explores Connecticut’s new ethnic studies elective and helps us bid farewell to the history curriculum of the past. We have other, smaller goodbyes—odes to the farmland that borders our city campus, farewells to staying quiet in spoken word poetry. A goodbye to home and all of its food, to the expenses of the year, to churches and summer and loved ones.

In our last issue as a managing board, we felt these farewells in everything we did: our last pitch meeting, our last production weekend, our last design proofing all-nighter. Our farewell isn’t unique. When we started our tenure as a board, we read over letters of advice from boards before ours and combed through their challenges. This February, we wrote our own letters. They are also a form of farewell, one that means we will be there for you.

We’re trying to think of this not as a goodbye but as a see you later. We can’t wait to see what our next board does, and the next one, and the next. This journal is as good as our lineage. We’ll be waiting when the plane lands.

With TNJ love always,

Abbey, Jabez, Paola, & Kylie

Thank you to our donors

Neela Banerjee*

Anson M. Beard

James Carney

Andrew Court

Romy Drucker

Jeffrey Foster

David Gerber

David Greenberg *

* Donated twice. Thank you!

Matthew Hamel

Makiko Harunari

James Lowe

Chaitanya Mehra

Ben Mueller

Sarah Nutman

Peter Phleger

Jeffrey Pollock

Editors-in-Chief Jabez Choi

Executive Editor

Adriane Quinlan

Elizabeth Sledge

Gabriel Snyder

Fred Strebeigh

Arya Sundaram

Stuart Weinzimer

Steven Weisman

Suzanne Wittebort

Abbey Kim

Paola Santos

Managing Editor Kylie Volavongsa

Verse Editors

Amal Biskin Cleo Maloney

Senior Editors

Meg Buzbee Ella Goldblum

Nicole Dirks Zachary Groz

Lazo Gitchos

Associate Editors

Naina Agrawal-Hardin Chloe Nguyen

Kinnia Cheuk

John Nguyen

Viola Clune Ingrid Rodríguez Vila

Grace Ellis Netanel Schwartz

Aanika Eragam Etai Smotrich-Barr

Maggie Grether Anouk Yeh

Samantha Liu

Copy Editors

Yvonne Agyapong Iz Klemmer

Connor Arakaki Adam Levine

Lilly Chai Victoria Siebor

Mia Cortés Castro

Podcast Editors

Meg Buzbee Suraj Singareddy

Sawan Garde Adam Winograd

Creative Director Chris de Santis

Design Editors

Tashroom Ahsan Cate Roser

Sarah Feng Jessica Sánchez

Alicia Gan Daniela Woldenberg

Angela Huo Ashley Zheng

Lily Lin

Photography

Web Design

Nithya Guthikonda Makda Assefa

Ellie Park Serena Ulammandakh

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Haley Cohen

Gilliland • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • Jonathan Dach •

Susan Dominus • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred

Strebeigh • Aliyya Swaby

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley • Susan

Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Joshua Civin •

Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • David

Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura Pappano •

Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy • Julia

Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Peter Cooper • Andy Court The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David

Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka

Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen •

Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer Pitts • R.

Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie Rutkow • Laura

Saavedra and David Buckley • Anne-Marie Slaughter •

Elizabeth Sledge • Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder •

Elizabeth Steig • John Jeremiah Sullivan • Daphne and David Sydney • Kristian and Margarita Whiteleather •

Blake Townsend Wilson • Daniel Yergin • William Yuen

cover story point

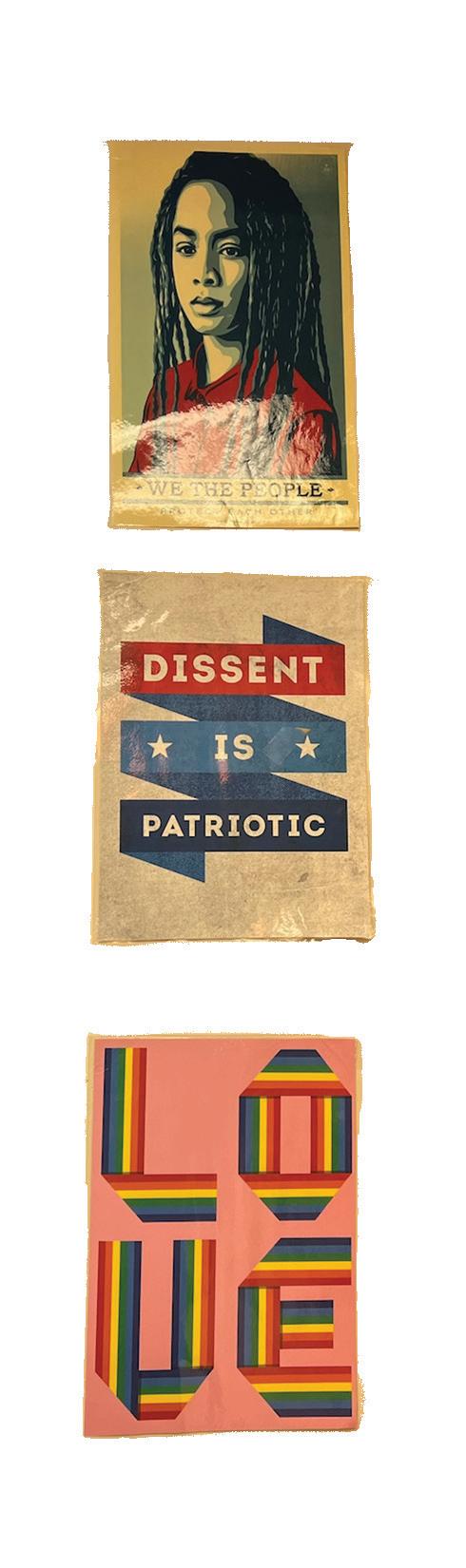

Penning Liberation

A writer explores The Word, a New Haven literary arts program for students to gather, write, and perform.

By Kingson Willssnapshots

Decked Out

A tribute to New Haven’s only dedicated skate-shop, Plush, and the public art of street skating.

By Zoya HaqFirst Light

Led by larger-than-life Chef Duff, Sunrise Cafe provides unhoused New Haveners breakfast and community.

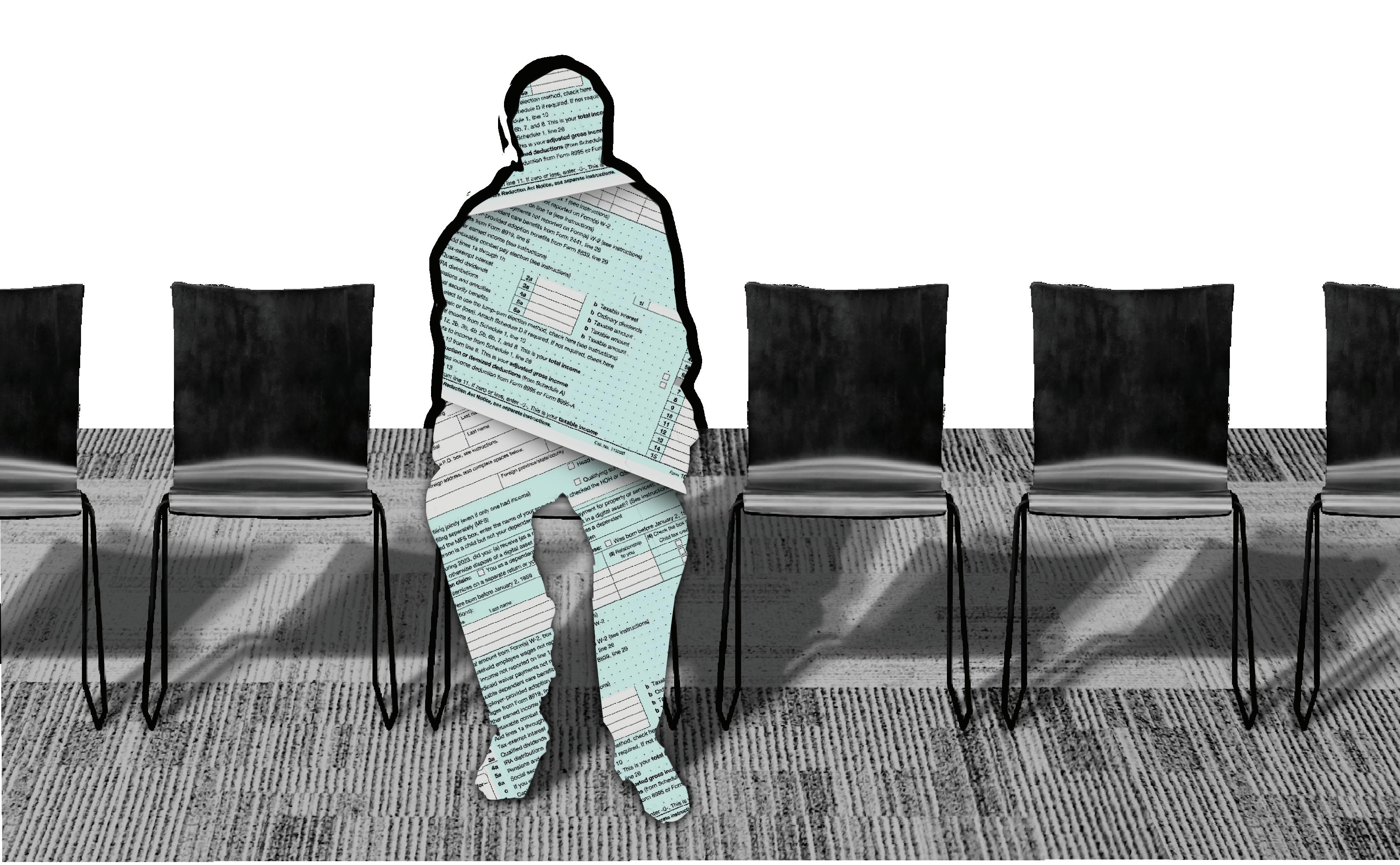

By Sophie LambTax Break

Under a complicated national tax filing system, New Haven residents and Yale students come together at the downtown Volunteer Income Tax Assistance site.

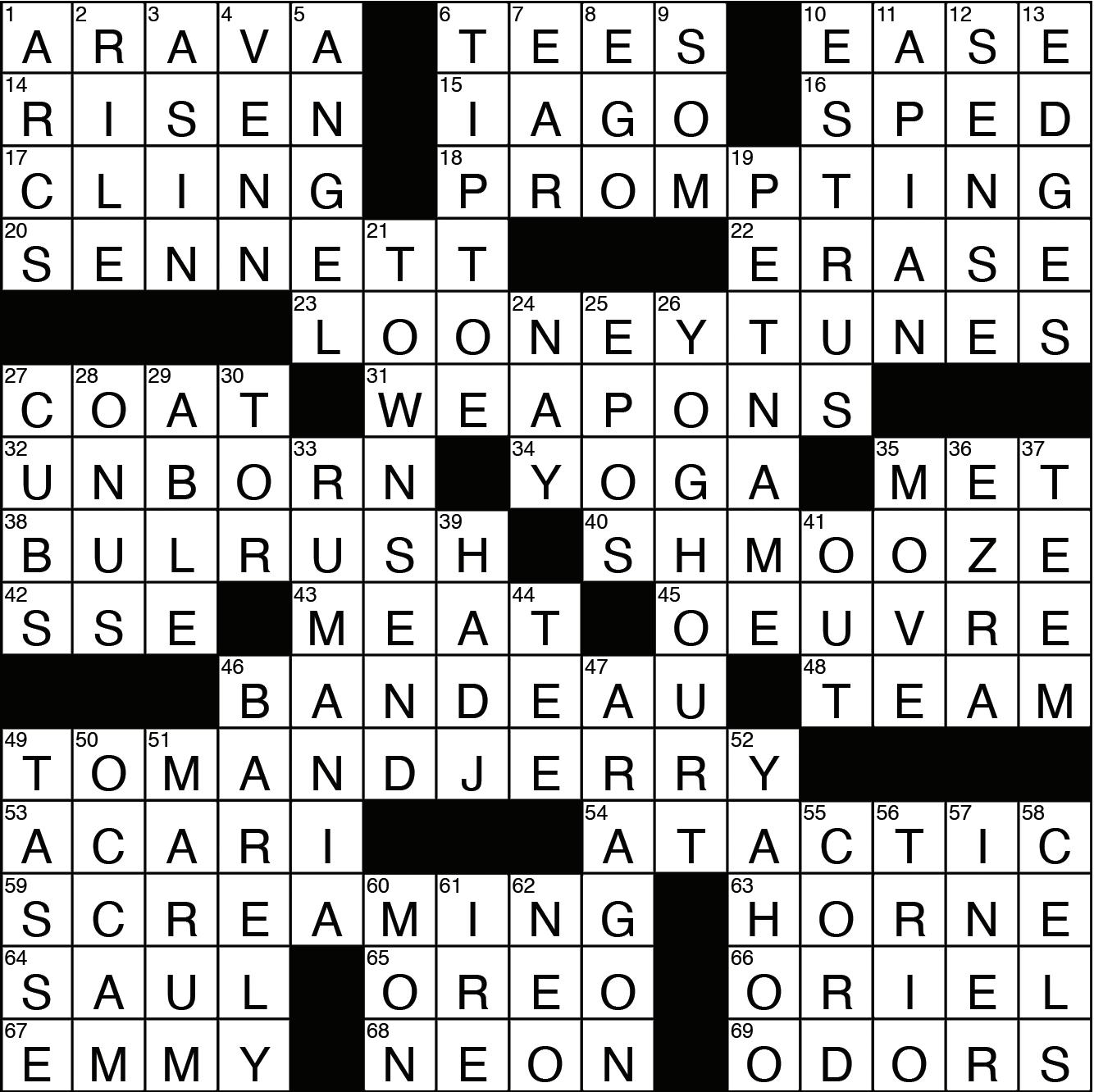

By Ai-Li Hollandercrossword: “Skate Park” by Adam Winograd, page 47.

Neighbors sound the alarm as Tweed New Haven Airport sprawls.

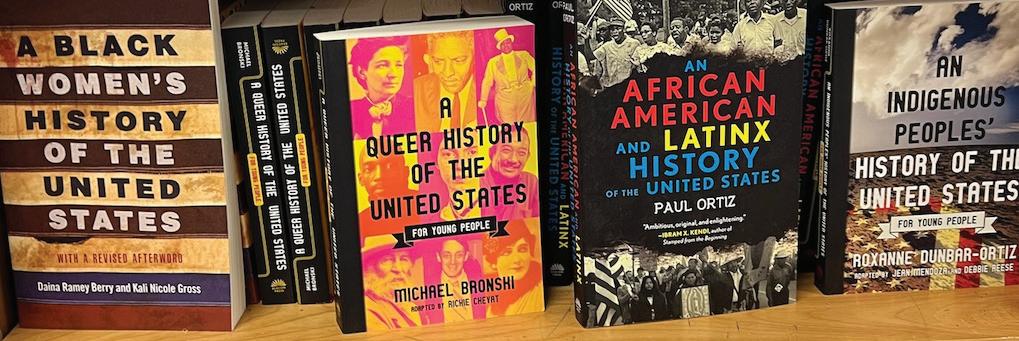

By Meg BuzbeeConnecticut became the first state to mandate an ethnic studies elective in high schools. How are New Haven teachers and students navigating the curriculum?

By Chloe Nguyenprofile

Home Truths

A writer seeks out authentic Chinese cuisine guided by Chef Jiang, the man behind his eponymous restaurant.

By Isabelle Qianpersonal essay

Name it to a God

A writer finds holiness in pews, paintings, and poetry.

By Madeline Artpoem

Moses

By Kanyinsola Anifowoshe

aside

That Summer

By Lucy TonThat

endnote

The Old Acre

A writer breaks ground on the myth-like delights of the Yale Farm.

By Lucy Hodgman

A writer explores The Word, a New Haven literary arts program for students to gather, write, and perform.

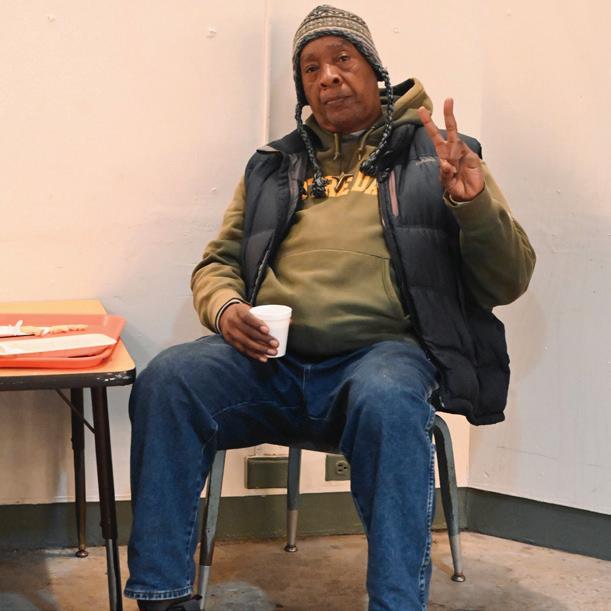

It’s a full house in the gym of High School in the Community. Tennis shoes squeak as students file into silver rows of bleachers. The air fills with the chatter of three hundred high schoolers left to their own devices.

In front of the crowd is Keiantae, a 16-year-old student rapper about to perform at his school’s Black History Month pep rally.

“I try not to really look at people because when I do I get nervous,” he told me after the show.

But this time, Keiantae can’t resist. As he gazes up from the shiny linoleum flooring, he is met with hundreds of eyes.

Giving a nod to the sound technician, Keiantae takes a deep breath and grips the mic.

Keiantae isn’t just any rapper, he’s a student poet. He’s been honing his craft in The Word, a literary arts program that has operated for twelve years in New Haven. The Word’s goal is to facilitate a radically inclusive writing and performance environment grounded in poetry, rap, and song. Every week, the group hosts “Writing Liberation Workshops” at the Neighborhood Music School— the group’s home base—and in-class poetry workshops in New Haven Public Schools, where students receive guidance on crafting poetry.

It is these workshops that brought me to Keiantae one winter morning in the “Introduction to Poetry” class of MarcAnthony Solli ’91.

In freezing weather, teens crept into class. Icy shoes scuffled along wooden floorboards as the first bell of the school day rang. One final student walked in late and found a seat in the back, a crumpled brown bag of McDonald’s peeking out from his backpack.

Shortly after, Tarishi “M.I.D.N.I.G.H.T.” Schuler entered, dressed in bright crimson red glasses and a hoodie to match. Tarishi is the current artistic director of The Word and the leader of that day’s poetry workshop.

“

M.I.D.N.I.G.H.T. is a pseudonym,” he told me. “It’s an acronym for a name I gave myself in my late teens. It stands for ‘Messiah Is Dominant Now Inspired God Helps Tarishi.’ I was born in 1976 when Alex Haley came out with Roots and a lot of parents were naming their children African names…I didn’t know until my early thirties, my name Tarishi is Swahili for ‘messenger.’ So I ended up being a poet not knowing that’s what my name meant.”

Tarishi, unfazed by the yawning class of sleepy high schoolers, asked for everyone in the room to stand. Chairs squeaked, heads rose, and shoulders slouched across the classroom as fifteen pairs of groggy eyes turned toward the smiling poet.

“Repeat after me,” Tarishi said before clearing his throat. “MEeeeee, MIiiiiii, MOOooooooooo!”

Giggles and laughs fluttered through the air as the students exchanged amused glances. This wasn’t what they had expected.

“He brings life to his poems,” one of the high school students told me after class. “His personality is contagious!” another said.

The mood shifted. One by one, students shared their own poems, greeted with applause from the rest of the class. Tarishi let the students put on their best “poetry-writing music” on the class computer, which the kids used as an opportunity to suggest their favorite new TikTok songs. Students raised their hands nervously, then quickly lowered them when Tarishi jokingly cold-called them to present. If students were too nervous (which they often were), Tarisihi recited his own poems first.

Keiantae sat quietly in the back of the classroom. His hoodie hid two clandestine white AirPods looping the drill beat to his newest poem titled “I Have a Dream” for the upcoming pep rally.

“M.I.D.N.I.G.H.T.’s a cool dude, and he’s so into it. I can’t explain it,” Keiantae told me. “It’s like he brings a different type of energy, and I mess with it.”

Keiantae is part of a new initiative by The Word. He is one of four New Haven Public School teens selected for a program that trains and hires students to become Teaching Artists like Tarishi. The fourteen-week program, which pays students $25 an hour during training, offers hands-on experiences led by mentors. Participants learn how to create course curriculums, lead workshops, and gel with other students in the program. These skills prepare them to eventually serve as independent teaching artists in New Haven.

When I asked him about his classroom’s partnership with The Word, High School in the Community teacher MarcAnthony could not understate its importance.

“It is nothing short of curriculum changing…allowing the curriculum to become a living, tangible, real thing for students where they see someone performing at the highest level of their art,” he says. “And that it is accessible. Right in front of them. Right down the street on Audubon Street.”

Keiantae sees The Word as a space to engage with his art and process hardship.

“New Haven is basically a place you want to get out of,” Keiantae said. “In order for me to make New Haven better, something’s gotta give, something’s gotta change.”

Keiantae first started rapping at the age of 12 after the loss of his father to gun violence.

“I rap about the minor setbacks to a major comeback,” Keiantae said. This adage seems to also be the theme of The Word.

On the first day we met, Tarishi and I sat across from each other in the Neighborhood Music School, about a mile away from High School in the Community. Students meet here weekly to practice for poetry slams and participate in Writing Liberation Workshops.

The day I visited was different than usual. The snack bowl of Goldfish, pretzels, and other goodies was still full. In the room, no one was there but me, Tarishi, and one student poet, Maximilian, who was also experiencing The Word for the first time.

Low turnout has plagued The Word since the start of the pandemic. “A lot of people have been struggling with afterschool programs,” Tarishi said, sliding me a pack of gummies. COVID-19 has imposed hardships on previous attendees of The Word: students lack the time to make art

as they scramble to find jobs to support families—not to mention the anxiety that comes with moving out of social isolation and trying to resume “normal” life with face-to-face interactions.

“But I feel like we are making a lot of progress and strides in the in-school workshops,” he said, referencing the in-class poetry workshops that The Word currently leads in eight public middle and high schools in New Haven.

Back in the gym of High School in the Community, students rise from their seats. Bodies sway and phones flash to the beat. Keiantae looks out to a sea of sparkling lights. As he raps the lyrics he perfected in The Word’s in-class workshop, he announces: “Alright, now I know that y’all mess with it. Let me really give y’all a show.” ∎

Kingson Wills is a sophomore in Silliman College.

In 1887, Moses dies, leaving Sarah alone with two-year-old A’lelia.

I have lifted the still slick tongue of the man. I have placed the coin—cool and heavy—beneath. I have let the mouth swing shut. Relinquished the blue-bruised body.

If there is such a thing as love, I have trembled in its shadow—thick velvet cape trailing, catching in the splintered floor. I have wondered what type of woman this shroud will become.

I have felt a small creature watching me with cavernous eyes. In the night, I have shown my mother-teeth.

—Kanyinsola Anifowoshe

If you turn left from Chapel Street onto Orange Street and walk about a block, chances are you’ll see a group of teenagers performing kickflips and ollies on the pavement. They’ll be outside a storefront with a giant wall of glass. That’s Plush: New Haven’s only dedicated skate shop, decorated with colorful skateboard decks and populated with the trendiest gear on the market.

Sir-Michael Burrow is the employee behind Plush’s white, rounded counter. As soon as I walk in, he shoots me a big smile and waves me over. “Feel free to ask any questions about anything in shop, and I’ll pull it out for you,” he says. He’s sporting a simple white T-shirt and blue jeans, nothing flashy. His outfit blends in with the plain white wall behind him. White accents—they’re everywhere. They contrast sharply with the colorful racks of clothes that hang a few feet from him, displaying popular brands such as Carhartt, Dickies, and Converse.

Burrow is from Waterbury, Connecticut, and has been skating in New Haven since he was 17. Now, at 25, he has a glint in his eyes when he talks about skating. He’s flanked by containers overflowing with skate periodicals and poster books.

Burrow’s favorite word is “sidebar.” As we begin to talk about Plush and its connection to New Haven skating, he throws it into our conversation to add more context to the growth of Connecticut’s skating culture. “Just a sidebar,” he says. “Another sidebar.”

Sidebar: a skate video filmed in Connecticut in the nineteen-nineties called Mama’s Boys brought more skaters to the city and

revitalized New Haven’s scene. Sidebar: when Plush opened, Vans came and shot a piece that put New Haven on the map again. Sidebar: for the past few decades, a vibrant skate film culture has been brewing in the city.

Before Plush opened in 2022, the last skateboarding shop in the city closed in 2015. The closure left New Haven skaters with a long commute to find gear and community.

Alexis Sablone, an Olympic skateboarder, and Trevor Thompson,

also a professional skater, both grew up around New Haven and recognized the inaccessibility of centralized hubs for skating culture in their home state and city. They decided to open Plush, harnessing the power of the local skateboarding community, and the expertise of Connecticut-area skaters like Burrow, to bring the shop to life.

Burrow tells me that their industry connections as professional skaters made the opening process seamless.

“Anyone can open a skate shop, but, like, you need to know what the hell’s actually going on in the trend scene and what companies are cool like the back of your hand,” Burrow said. “As pros, Alexis and Trevor are friends with people who are pros. It’s about being plugged in.”

Rifling through the clothing racks of the store—organized by color to create a rainbow of choices—you’ll find high-end skate brands ranging from the more commercial Vans to the Colorado-based Polar Skate Co. Behind the hanging clothes is a mural of skate decks and boards; to the left of them, you’ll find a wall displaying the most trendy sneakers on the market. The highly-curated selection of options in Plush and the aesthetic of their presentation make it feel like not just a skate shop, but an art gallery.

Plush’s role in New Haven isn’t really retail, though. It’s to create a space where New Haven skaters can come together and build camaraderie.

Plush holds monthly events, like skate video screenings and

pop-up vintage markets. “It’s a meet up place,” Burrow says. “You have everyone knowing that there’s this one place where they can come together and, you know, skate together whenever.”

Community hubs like Plush naturally function as sites for structural change, too. As a centralized location for skaters, Plush has been instrumental in advocating for more skating spaces in New Haven. The majority of this advocacy can be tied back to Ben Berkowitz, co-owner of Plush.

Since lending a hand to Sablone and Thompson in the opening of Plush, Berkowitz, who is also a local skater, has used the scale of Plush’s wide-reaching community as proof to the city of the need for more skating locations. He’s been successful. Berkowitz worked with New Haven and the Parking Authority Board to transform Temple Street Parking Garage, a formerly unofficial skating hub, into an official indoor skatepark. With his encouragement, city leaders opened Scantlebury Park, a skatepark on Ashmun Street, and a new skating bowl on George Street in 2021.

However, the preservation of street skating, an essential part of skateboarding culture, has been harder to reconcile with the city—and with Yale.

While street skating is not technically illegal in New Haven, it is heavily policed, especially on and around

Yale’s campus. Beinecke Plaza, a popular skate spot, is often patrolled by Yale Security personnel, and skaters have faced backlash—including removal— for trying to skate it and other parts of campus.

“Street skateboarding… it’s kind of what makes skateboarding skateboarding,” Burrow says. “The spirit of resilience, of getting kicked out and coming back is a big portion of street skateboarding. Builds character.”

When I walked into Plush, Burrow had been laughing with four teenage boys, all decked in mostly-black baggy jeans and T-shirts. As soon as Burrow and I start talking, the boys flee to the street. I can still see them outside of Plush’s giant window, skating in circles around the block. One of the boys comes up and taps on the window, making a face at Burrow. He laughs.

“I’ve known these kids for a while because I’ve been skating out here for a few years,” Burrow says. “That’s another thing—skating, shops like these, it gives the kids a place to go instead of a bar or some other time-wasting thing. Skating is…it’s freedom. We’re giving them that here.”

I grew up skateboarding. Walking into Plush, I was instantly comforted by the familiarity of the shop’s environment, its palpably laid-back energy. Hip-hop music played softly over the loudspeakers

as the teenagers around the counter laughed with Burrow. I could have met them in a skatepark back home—they were wearing the same outfits that were so recognizable to me, and had the same quippy way of speaking that felt like a constant challenge. Skating not only liberates; it also connects.

Another tap at the window. It’s been a few minutes since the last. Same kid— same face, small and covered by a mop of light-brown hair. Burrow’s eyes light up. It’s clear that these kids aren’t just shop regulars. They’ve become his friends. Burrow strolls to the door and yells out into the chilly February evening. “Mead! Get in here.”

The kid—no older than 17—glides up to the door and steps in. He’s holding a mini, skateboard-shaped fidget toy. He comes up to me at the counter and gives me a nod. The fidget skateboard flips in his fingers.

Mead taps his foot on the ground. “Are you a student?”

When I nod my head yes, he looks at Burrow and takes a deep breath.

Mead has been skating for six years. “Not that long,” he assures me. His terrain is the street, not the parks. Echoing Burrow’s reflection on the power of street skating, he tells me that street skating preserves skating culture.

“A lot of people that don’t skate assume it’s all about the parks, but

skating started on the street, it’s meant for the street,” he tells me. “Street skating is something you can learn from. You need dedication for it. It’s escapism. I use it to cope.”

For the first time in our conversation, he makes direct eye contact with me. “You go to Yale?”

I nod.

Yale’s Schwarzman Center has funneled thousands of dollars into local skatepark construction, including Scantlebury Park’s and the skate bowl on George Street. While the main publicized reason for this funding has been to support the cultural benefits of skateboarding, Mead thinks that the popularity of Beinecke Plaza as a skate spot acts as a secondary motivation.

“I’ve been wanting to tell someone this, so Yale should hear it. They have power,” he says. He flips his fidget skateboard on the counter. “Just because the city and Yale keep building these skateparks and stuff doesn’t mean that they change anything for us street skaters. Pouring money into that isn’t going to change the fact that we’re going to skate Beinecke.”

He articulates his final point with a passion that differs from his earlier drawl: “And if they really want us to stay off their property, don’t build the skateparks outside. Like, centralize it in the city. It’s a trek to get to the parks.”

He’s not wrong. The closest park to Plush is Scantlebury Park, located behind Pauli Murray College off of Ashmun Street. It’s a twenty-five-minute walk from Plush’s centralized, downtown location.

The next day, I make the journey up to Scantlebury, located off the Canal Trail. My jacket barely keeps me warm against the frigid wind. It beats at my face as I navigate the icy sidewalk. The playground next to the skatepark is, unsurprisingly, empty. As I trek up the short hill that leads to the base of the park, though, I can hear the click of wheels against asphalt. The only person within eyesight is a single skateboarder practicing tricks on the slopes.

His name is Michael Skirkanich. He’s middle-aged, definitely older than the kids I saw at Plush. Unlike them, he’s wearing a helmet. “Don’t want to crack my head open,” he says. When I sit down on the concrete next to the skatepark, we begin to talk about Scantlebury.

the musicality of the sport, the rhythm of the wheels. I think that, in a strange way, my yearning for that feeling was what made me so interested in the presence of skateboarding on every street in New Haven—one of the first things I noticed about the city was how much skating was embedded into its culture. At street corners and in parks, on campus and off, there are skaters. The sound of wheels on asphalt is an essential part of the urban melody of my new home.

I stopped skateboarding when I was 15 because of a shoelace-in-wheel trip that left me in an arm cast for a month. Sitting criss-cross on the side of the curving, concrete slopes, I tell Skirkanich this. I tell him about the weird fear I have of stepping on a board now, about how it reminds me of the crack I heard— and the instant shoot of pain I felt—four years ago when I last did it. He scoffs.

“You’re telling me you broke your wrist four years ago and haven’t gotten back on a board? I broke my ankle. I’m here,” he says. I’m reminded of Burrow’s point: that skating is all about resilience. You just have to keep going for it. Skirkanich echoes him. “You have to keep trying, keep going for it.”

“Come stand on my board and you’ll see,” he says. “You gotta try.”

“I like being out here alone,” he tells me. “When I’m here, I don’t care about, think about anything else. It’s just skateboarding. Without the squirts—the teens—I can focus.”

As we’re talking, he pauses every so often to focus on a particular trick or flip. “I come out here seven, eight hours a day,” he explains. “I see every day as a good day or a training day.”

Unlike Mead, the skatepark is an essential space for Michael. It provides a structured space for him to focus on the “artistic” side of his skating craft.

After all, to him, skateboarding is, in one word, self-fulfillment. “Not many people can do this, and that fulfills me. Landing a trick, the sound, it’s like music, it fills me up.”

Music. He’s right. I’m reminded again of my own skating roots. I used to love

He waves me over, kicks his board towards me. “It’s all about baby steps.”

I balance myself on his board. He holds his arm out. “Hey, it’s nice. Mercedes of skateboards. Be careful,” he makes sure to let me know. For the first time in a long while, I feel the liberation of skating. How it is freedom, like Burrow told me, how it is self-fulfillment, like Michael tells me, and I get it. It clicks.

Back at Plush, Burrow left me with some words that pretty much sum it up. “New Haven, skating, music, culture, film, they all go hand in hand,” Burrow told me. “Skating is art. It needs to be treated like art. It needs to be respected like art.”

Art on the street—art in the park. Both go hand in hand. Skateboarding, as art, is an inherently public sport. It deserves space both in structured environments and in the city at large.

Stand on a board like I did, and maybe you’ll get it too. ∎

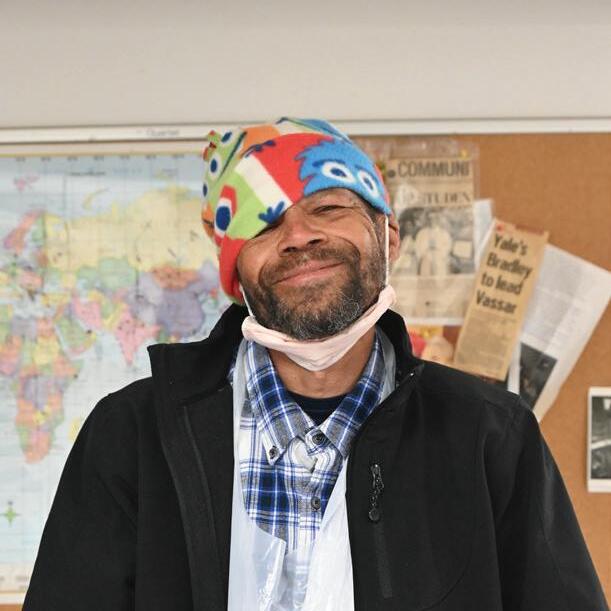

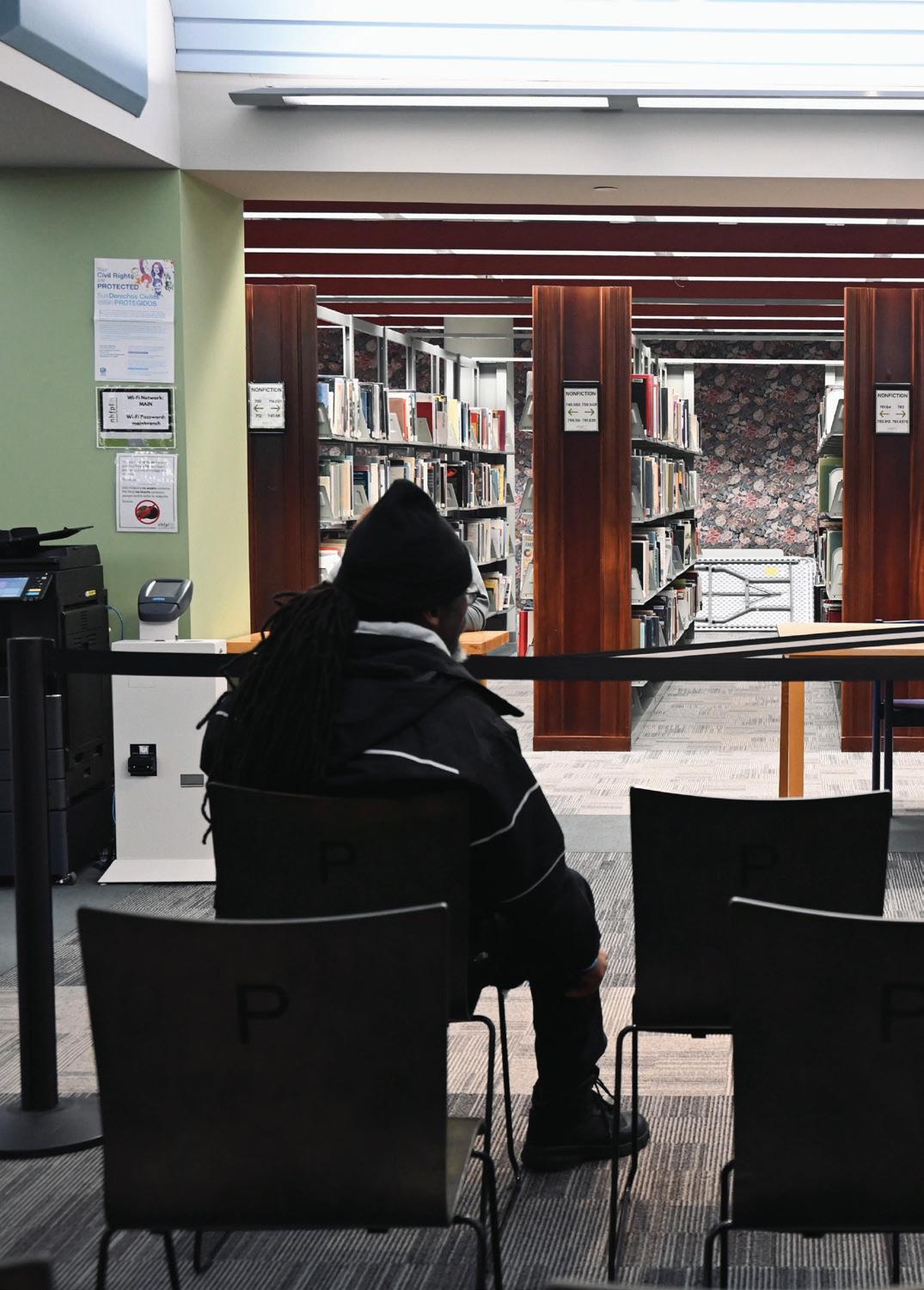

Led by larger-than-life Chef Duff, Sunrise Cafe provides unhoused New Haveners breakfast and community.

By Sophie Lamb

Paul McDuffy has been feeding people since he was 12. “We were raised poor,” he tells me after his Friday shift at Sunrise Cafe. “And because of being poor, my mom taught us how to stretch $1 in the community.” McDuffy has lived in New Haven his entire life. He reminisces about the butcher at Ferraro’s Market who taught him to use his family’s food stamps to buy food in bulk, and the Westville neighborhood barbecues where his mom laid out burgers dripping in mayo and relish.

McDuffy—or Chef Duff, as he’s affectionately called by guests and coworkers at Sunrise Cafe—likes to use “we” interchangeably with “I” when he talks about food. Towering over staff in a threadbare apron and wrecked purple Jordans—a gift from his best friend and “corner brother”—Duff has a gentle gravity. He grew up in the nineteen-eighties, as New Haven faced economic collapse. The city was razing once-vibrant communities to construct the Oak Street Connector interstate, and the fiery factories that guarded the city’s harbor were transforming into vacant redbrick shells. From 1970 to 1980, the city went from being the thirty-eighth most impoverished in the nation to the seventh. By the time Duff was in ninth grade, a quarter of New Haven youth were living below the poverty line.

bus stop. When one approached him, his immediate reflex was to hand her the contents of his wallet. “She politely said ‘No, sir, I really don’t want your money. I really am hungry.’” Instead of taking the bus home, Duff took the bus to Stop & Shop, bought $12 worth of canned bologna and Wonder Bread, and returned to the Green.

He kept coming back. Five days a week, Duff finished his guard shift and started cooking. His meals morphed from bologna sandwiches to boiling pots of meatball chili; he went from feeding ten people to hundreds. Friends and strangers alike helped him buy groceries and serve. “It was cool,” Duff says,

I first volunteered at Sunrise in late October. On the dark walk along Chapel Street, I anticipated a standard soup kitchen—bags of pre-packed food, limited seating, and a line of people twisting out onto the sidewalk. Instead, when I stepped through its glass doors, I was greeted with rows of white tablecloths stretched taut over wooden tables, slouching with fat vases of flowers and steaming cups of coffee. Guests sat and laughed, or danced to music spilling from a piano in the corner. A couple of volunteers ran from an industrial kitchen out into the dining room, balancing trays piled high with fish tacos, french toast, and orange juice.

Duff’s classrooms were marked by conflict. His mom used to warn him: “Kids act out and bully other kids because they’re hungry.” She would pack an extra chicken sandwich in his bag each day to feed friends who didn’t have food at home. Watching them smile after a good meal invigorated pre-teen Duff: “We can show people love through food [so] I made a promise to feed as many people as possible.”

In 2015, Duff began working overnight shifts as a security guard. He recalls walking past a group of ten unhoused girls huddled against the morning chill on the New Haven Green, on his way to the Chapel Street

“It was like the community was backing me.” In November 2020, word of Duff’s cooking and tenacity reached Sunrise Cafe’s doorstep. At the time, Sunrise was struggling with a dramatic drop in guests and fluctuations in kitchen staff.

Now it’s bustling. Open weekdays at 6:30 a.m., Sunrise serves free breakfast to some three hundred unhoused guests out of the basement of St. Paul and St. James’s church. Chef Duff uses donated ingredients to cook a perpetually rotating menu of fried fish tacos, sausage and grits, lasagna, French toast, and fried chicken. When I ask why lasagna for breakfast, Duff laughs. “I want to treat them. I want them to eat what they usually don’t get to eat.”

Sunrise’s full menu and restaurant-style ordering system is the work of Ellen Gabrielle, who founded Sunrise in 2015. She envisioned a more humane soup kitchen— complete with a menu where guests can order and have food brought to them in a restaurant-style service model.

Sally, a retired nurse and social worker, has been volunteering for Sunrise since the beginning. She watched Ellen build the Cafe. “Yes, these places are very important for feeding… people. [But] the goal from the beginning was to make [Sunrise] a dignified place to eat.” Throughout our conversation, she keeps returning to the word “dignified.” If guests need an extra pair of gloves, clean socks, or someone to talk to, they ask for Sally. Wrapped in a mask, glasses, gloves, and a plastic apron, she slips between the kitchen, food pantry, and clothing closet with her keychain in hand.

Most mornings, Robert eats behind Sunrise’s piano. “I play it any chance I can. So I don’t forget,” he tells me with a smile, adjusting his black beanie as we talk. “Not having a place to be is a lot of pain to bear, so I use piano to get away from the suffering.” He pauses, placing his battered copy of R&B For Dummies on the music rack, and erupts: long fingers delicately pulling across the length of the glittering Yamaha, head swaying,

eyes closed. Finding serendipitous joy like this is Robert’s driving conviction. “It’s good you can come to a place early in the morning to eat. And I get to play the piano here. That brings me happiness.”

Fostering a comforting space hasn’t always been easy. When Duff first arrived, “it was hard for us [to] even serve a meal without a fight breaking out.” He’s “quit in his head” a thousand times over. The weight of these challenges is built into the fabric of Sunrise: the heavily bolted pantry, plastic knives, and worn-through floors.

“Some days it’s intense. People have their moments,” says Casey, a mom of five who just moved to New Haven from Alaska. “Moments” are what Casey calls fights. Her oldest son, Eprum, a tall, curly-haired teen, sits next to me. “[Eprum] has moments all the time… because that’s what they are. They’re over soon.”

He reminisces about the butcher at Ferraro’s Market who taught him to use his family’s food stamps to buy food in bulk, and the Westville neighborhood barbecues where his mom laid out burgers dripping in mayo and relish.

I sit down with Casey during a lull in my morning service. She’s soft-spoken, swathed in two jackets to keep warm from the January chill. As we talk, she turns away from me to lock eyes with Eprum, or leans over to brush the hair from her one-year-old’s forehead. Eprum is autistic, and Casey is solely responsible for his education. Between teaching and caring for her toddler, Casey hasn’t had time to find a job. The family is currently living in the Continuum Shelter on Foxon Boulevard. At the end of February, their ninety-day stay period will run out. “We don’t know what we’re going to do,” she says, her fingers wrapped tightly around Eprum’s hand. They’re hoping to receive a Section 8 voucher—a federally

mandated program that subsidizes the cost of rent for low-income people—but, according to the Connecticut Department of Housing, it can take up to “a few months’’ for their application to be processed.

Robert is also trying to get Section 8 benefits. “To get a voucher you need papers. And it’s impossible to keep track of papers when you carry your life on your back. It’s not like you can lock your Social Security Card in a bush.” He laughs and fiddles with a few keys. “Right?”

The day we talk, Robert is leaving Sunrise early to attend a series of job interviews. He’s nervous about employment—he’s still reeling from a string of exploitative employers and worries the time spent on a job will be time taken away from finding housing. Earlier this year, he was hired to put up a wall for a church—a three-week stint of nailing, plastering, painting, and sweating in a church basement. “I went to the lady for my paycheck,” he says, “and she told me, ‘I’m not paying you.’ They know that if you don’t have a permit, a license, not insured, you don’t have a leg to stand on.”

Between fleeting conversations with guests and volunteers, I met a construction worker reeling from eviction, a musician from New Orleans who found a place to live, and a Yale Law School graduate grieving a brutal divorce. Despite varying tracks to homelessness, guests share parallel experiences in their fight to escape it. They describe their first nights without a home spent on friends’ couches and in cars; when their friends’ patience ran out, they turned to temporary shelters. These shelters house people anywhere from three to ninety days. But as homelessness rates continue to increase in Connecticut, shelter housing is stretched thin, leaving long waiting lists, and overcrowded accommodation. In hopes of a more reliable option, many apply for Section 8. But, as in Casey and Robert’s case, this process can take months. As shelter slips in and out of place, many end up on the streets. Most days, Robert walks until he finds somewhere safe enough to sleep: “There’s really no place where you can sit and be. You’re just wandering.”

In Sunrise’s cluttered kitchen, I meet Nelson, a dimpled, grinning 30-something who came to New Haven from Puerto Rico when he was 7. The move made him grow up fast; he supported himself and his sisters

through high school before meeting his girlfriend of ten years. Nelson first became homeless after his girlfriend suffered a stroke, and he couldn’t spread his income thin enough to cover the costs of rent and healthcare. He thought he would never escape. “I used to sleep in hallways,” he tells me. “When I couldn’t find food, I just drank water.” For twelve years, he bounced between housing arrangements and living on the streets until landing in prison four years ago. He’s currently living in a halfway house

“Get angry. We're all in this fight together,”

Chef Duff tells all of Sunrise’s guests. He wants them to walk through these doors and leave better.

I was starving on the streets. Now I can be that help for someone else.” For many of the volunteers, working at Sunrise is a way to reconcile their experiences with homelessness.

However, for many of the guests, eating at Sunrise can hold up a mirror to the battles they are facing. Robert stops me at the door. “I need you to know I don’t ever feel good having to come here another day," he says.“You go in Sunrise and you look around and you see what you’re going through ten by ten by a hundred times.”

Duff believes there can be power in that. “Get angry. We’re all in this fight together,” he tells all of Sunrise’s guests. He wants them to walk through these doors and “leave better”—whether that is wiping down a tablecloth or getting sober. Duff speaks a lot about the successes and failures he watches pass through Sunrise’s walls: “Everybody who [gets] a job comes to me and says ‘Chef, I have a job.’” They tell him if they found new housing or bought their girlfriend a coat. They also tell him if they relapse or get kicked out of a shelter.

triumphantly chants, “Baby’s here, baby’s here!” Arms laden with goodies—and a steaming stack of chocolate pancakes— he hugs Casey, Eprum, and Casey’s oneyear-old. The chaos of Sunrise swells around them: piano filling the air, steam rising from cups of hot coffee, laughter booming from the kitchen. Casey left her support system when she left Alaska. “But Chef takes care of us,” she smiles.

“Evil works twenty-four hours a day. It never takes a break. It never rests. It never stops.” Duff’s voice cracks as he tells me this. You can feel this evil pressing in on all sides of Sunrise, a midnight swarm of evictions and addictions, of bad employers and bottomless legal battles. “I gotta go ahead and make sure we love each other.” ∎

Sophie Lamb is a first-year in Jonathan Edwards College. while he works on getting back on his feet. One of the ways he’s healing is by waking up at 5 a.m. every morning to volunteer at Sunrise. Nelson brims with enthusiasm, carrying trays of food three at a time, high-fiving and hugging me as we pass each other. “I wished someone would help me when

Running to the back pantry to collect a bag of mango yogurt, stuffed unicorns, and applesauce, Duff

Check out the second episode of the TNJ Podcast! In this episode, Suraj Singareddy interviews organizers with Yalies4Palestine and Jews4Ceasefire, Meg Buzbee digs deeper into her investigation on Tweed New Haven Airport, and Sophie Lamb brings us into Sunrise Cafe. Listen to these stories, and more, on The New Journal website!

By Meg Buzbee

By Meg Buzbee

Diana Gilman-Ford doesn’t like to fly. She hasn’t been on a plane since the late nineteen-nineties, and even then, she didn’t make it off the ground. While the plane was still on the tarmac, she suffered a panic attack and had to disembark. Still, for most of her life, GilmanFord looked up at planes in the sky with awe. What a marvel, she used to think. Men in the sky.

Then, in August 2022, Tweed New Haven Airport, located just 50 yards down the street from Gilman-Ford’s house, entered into a forty-three-year contract with the airport management company Avports LLC . The deal paved the way for a one-hundred-million-dollar investment in the expansion of the airport. A year earlier, in May 2021, the Airport Authority had announced a new partnership with Avelo Airlines, an ultra-low-cost carrier that began offering flights out of New Haven in November 2021.

Now, over twenty Boeing 737 jets take off and land each day on the Tweed runway, situated three miles from downtown New Haven. Sometimes the jets move as late as 10:30 p.m. Gilman-Ford calls her house, which she has lived in for twelve years, a newfound “nightmare.” She keeps her windows closed to block the smell of jet fuel. She stopped hanging the clothesline and pruning the garden last year. And then there’s the noise. “I don’t even have words for the noise,” Gilman-Ford said. “There are times it’s so bad you cannot even function.”

“I have great empathy for people who live near the airport,” said Matthew Hoey, the First Selectman of Guilford and Chair of the Tweed

Airport Authority Board. Still, he has supported the airport expansion from the beginning. He worked with Avports and Avelo in the initial stages to secure their investments. From his perspective, the expansion of Tweed is for the common good. “The success of the airport has spillover for the region, and for the immediate vicinity,” Hoey said. And besides, “No one who bought a house didn’t know the airport was there.”

Opponents and proponents of the Tweed Airport expansion seem to operate in entirely different registers. Critics of the airport, largely residing within a few miles of Tweed, denounce the noise and air pollution, as well as increased traffic and safety concerns. Gretl Gallicchio, who lives in New Haven near the airport, said that she had to “completely reevaluate what it means to have a future” in her once quiet neighborhood. “It’s depressing,” she said, “to watch the place where we’ve lived be destroyed.”

Residents of these low-lying, shoreline neighborhoods already contend with warming and flooding, local consequences of the global climate crisis. They are skeptical of the value of Tweed’s future LEED -certified, energy-efficient terminal—especially when the aviation industry plays a massive role in carbon emissions. Such environmental concerns would be compounded by jumbo jets, the traffic, and the increased strain on emergency services that will come with the expansion.

Proponents of the airport are quick to recognize these concerns but dismiss them with

utilitarian logic—more people will benefit from Tweed than will be hurt, and thus the expansion will be justified. The benefit takes many forms: economic growth from jobs in aviation and construction, accessible and affordable travel from Avelo’s budget flights, and a potential decrease in energy use after construction of the new, LEED-certified terminal.

The one thing everyone can agree upon is how enormous and successful the expansion of Tweed services has been already, and how impactful future changes will likely continue to be. Since the first Avelo flight took off from New Haven on November 3, 2021, and landed in Orlando about two hours later, Avports has seen an eleven-fold increase in air traffic at Tweed. In 2020, there were thirty-eight thousand enplanements at Tweed. In 2023, there were 465,538. According to Tom Rafter, Executive Director of the Tweed New Haven Airport Authority, Tweed is the second fastest-growing airport in the United States. This may only be the start. Under Avports’ master plan for its lease from the Airport Authority, effective until 2065, the company will invest one hundred million dollars into Tweed and oversee the construction of a new terminal and extension of the runway.

To Hoey, New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker, and most other politicians with a stake in the fight, the equation is simple. Tweed brings jobs and revenue to the region. Private investment from Goldman Sachs-owned Avports pays for the venture. Government departments oversee permits and regulations to ensure that construction is up to federal standards. The world carries on, the same as it always has, now with six additional flights from New Haven to Florida every day. But for residents like Gilman-Ford, it’s a world changed. The noise that disrupts her sleep, the vegetable garden and clotheslines she feels she’s lost access to, and the black soot she says covers the outside

of her house are enough signs of the impact. “I don’t care what that study says,” she said, speaking about federal environmental impact reports. “Because we know, we’re living here.”

For all its rapid growth, Tweed is tiny, sitting low down in a large bowl just twelve feet above sea level. To get there, drivers exit I-95, the main throughway to town, and roll down a two-lane road with yellow lines down the middle and parking lanes on either side. Only small green signs with a white airplane icon and an arrow indicate that Tweed is nearby. Single-family homes spaced about 15 feet apart with grassy lawns line the block. Speed bumps and yard signs increase in number closer to the airport: “Keep Tweed Small,” they read. On the tarmac, across the street and behind the terminal, there’s usually at least one purple, white, and yellow Avelo 737 jet. Morris Creek flows underneath the air traffic control tower, underneath the terminal, and down the tarmac on the other side.

Tweed Airport is not a new addition to this tree-lined New Haven neighborhood. Opened in 1931 as the New Haven Municipal Airport, it took the name Tweed in 1961 from its first manager, John H. Tweed. Having purchased the land from East Haven in 1931, the City of New Haven fully owns the acres that Tweed sits on and leases it to the Tweed Airport Authority. The complex also crosses into neighboring East Haven, although East Haven does not share any financial ownership. Throughout the twentieth century, flight offerings shifted as different airlines attempted to run routes through New Haven. Due to the short length of the runway and small terminal, planes were small and flight schedules inconsistent. More often than not, passengers chose to fly from New York, Hartford, or Westchester instead.

Before 2021, there were not constant 737s at Tweed as there are today, which seat up to 120 passengers; instead, just narrow-bodied airliners seating about seventy-five people maximum. This was due to a 2015 legal battle, where the Connecticut government prevented the Airport Authority from expanding the length of the runway. The move would have allowed for larger planes and additional carriers to service Tweed. Then, in July 2019, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed that decision.

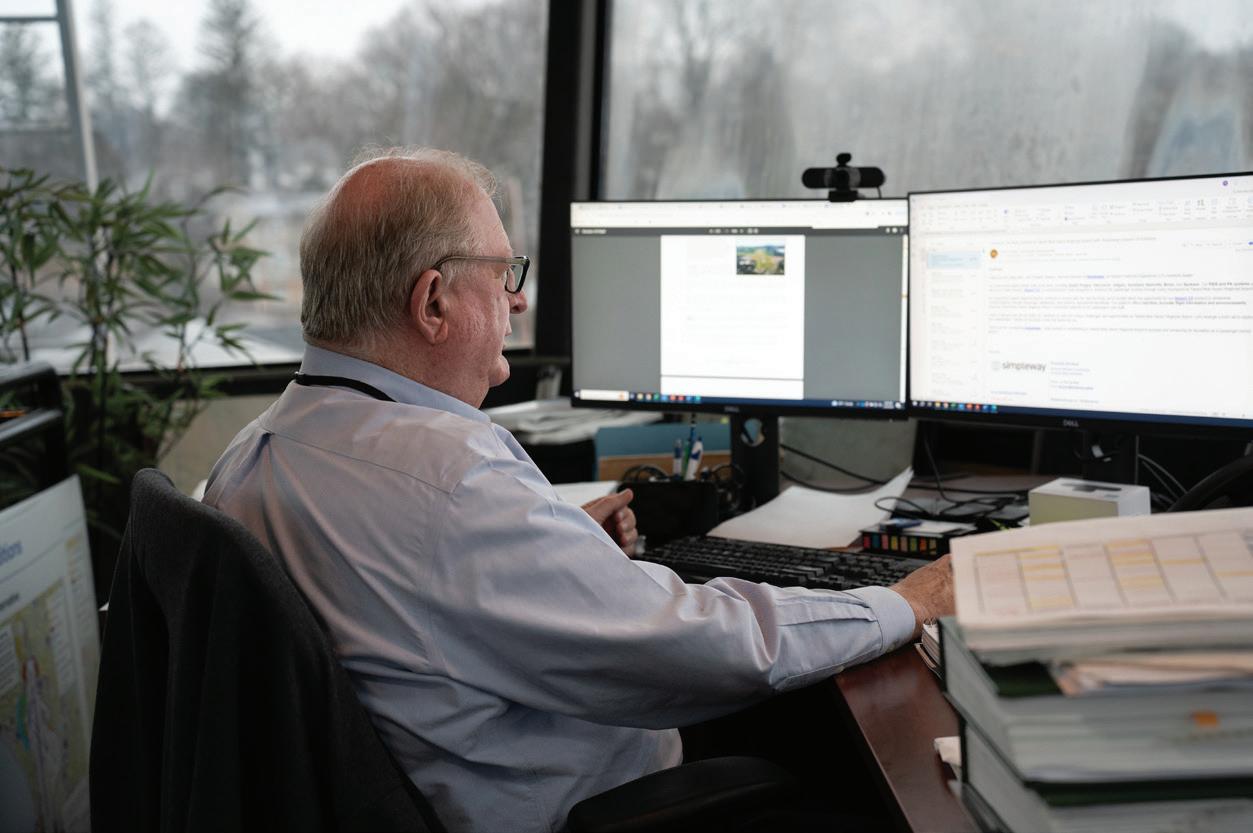

Rafter, the Executive Director of the Airport Authority, keeps a small orange booklet with the details of the Supreme Court ruling on his desk at his Tweed office. It reminds him of past resistance to the airport and the avenues through which expansion was still able to move forward.

Rafter, like Hoey, who sits on the board, seems unfazed by local opposition to Tweed

expansion. A veteran of the aviation industry, he’s been in similar situations before. “I’ve lived at the end of runways, I’ve lived near airports,” Rafter said. “I understand their concerns.” He says opponents, though vocal, are not the only ones with an opinion about Tweed. The people who use the airport, who fly the Avelo flights, park in the nearby parking lot, and work jobs in the terminal, he argues, are showing their support for the airport and its expansion through their actions. Tweed also has its vocal cheerleaders: numerous residents of New Haven, East Haven, and surrounding towns who post updates on new Avelo routes, videos taking off over the Long Island Sound, and updates on weather delays.

Yale students and affiliates alike also frequently fly through Tweed. Camila Young ’26 has taken over twelve Avelo flights since beginning college between New Haven and her home in Miami. “I really like Tweed,” she said. For Young, the small airport is convenient and she finds the people there friendly. “It seems kind of like the mom-and-pop version of the airport.”

Most days, Rafter has the tower to himself. From up here, he can see the entire expanse of Tweed: the houses on Burr Street which sit right across from the airport gates; the cars loading and unloading in front of the terminal; the brook that runs from the parking lot to the tower; and the planes as they land, taxi, disembark passengers, and take off again. Above it all is the expansive sky, visible for 360 degrees from the wrap-around windows in Rafter’s tower.

From up here, Tweed looks beautiful. The tarmac is lower than the surrounding houses, with orange and red foliage on all sides. To the East Haven side of the airport, where the new terminal will be built, Rafter points out a few commercial buildings and the woods he says separates the airport from residential areas. “The longest highway in the world is a runway,” he says. “There are airports around the entire country and they are part of a larger system.”

Gilman-Ford stands in the parking lot of Robinson Aviation on the east side of the terminal, watching the planes. Next to her, the surface of her car, a 2010 Mercury Sable, is covered in a thin layer of brown grime which she says is from airplane combustion. A yellow “Stop Tweed Expansion” sticker is peeling off at the edges. A plane took off three minutes ago, and it takes that long for the jet fumes to make their way over on the wind.

Both Gilman-Ford and her daughter have asthma. She said her daughter’s asthma attacks

have become more frequent since Avelo arrived. In East Haven, more than 21 percent of children have asthma compared to just 14 percent in New Haven and just 13 percent throughout the rest of Connecticut. East Haven is already home to several oil storage facilities, power plants, and trash collections, not to mention a mile-long stretch of I-95. East Haven is also an Environmental Justice Community, defined by the Connecticut state government as an area with high poverty rates where developers must have a plan to engage local stakeholders before they can seek permits. This is usually done through public meetings or comment periods, where residents can provide feedback on proposed plans. Because Tweed has been zoned as an airport since its inception, and because airports fall largely under federal jurisdiction, the expansion hasn’t legally required all these state-level procedures.

As a result, some residents have taken it upon themselves to assess the environmental and health impacts of Tweed on the already-impacted communities. A local environmental group called 10,000 Hawks partnered with Tufts University researcher Neelakshi Hudda to study air pollution around Tweed. Residents kept air quality monitors in their homes over the course of two weeks. Hudda found that ultrafine air pollution particles increase by 188 percent during plane takeoff and landing, up to half a mile away from the airport.

In December 2023, the Federal Aviation Authority ( FAA ) issued a Finding of No Significant Impact ( FONSI ), which concluded that Tweed’s expansion would have no significant impact on the environment. This finding was the result of the FAA Environmental Assessment ( EA ), a routine procedure that must be completed for expansion plans to move forward.

“When I heard the news of the FONSI I burst into tears and I doubled over on the floor,” Gallicchio said. “I was literally that shocked. The EA was a complete shocking act of greenwashing.”

Save the Sound, a New Haven-based nonprofit, is currently appealing the Environmental Assessment. It cites the numerous state and federal agencies—including the Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection—that, like Gallicchio, have pointed out shortcomings in the document. For example, ultrafine particle pollution was not considered in the FAA’s EA, as these are not federally-regulated pollutants. Neither were the impacts of leaded fuel used by small, private aircrafts. Wetland impacts are also largely left out of the document, which states that there are “no critical habitats within the project site,” a fact that local residents and Save the Sound refute.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the aviation industry accounts for 3.5 percent of warming worldwide. If the industry were a country, it would be the sixth-largest emitter in the world as of 2019. Opponents of Tweed see this as a key reason to limit the growth of the airport. “This is an expansion of an impossibly wet, small, foggy airport during an era of climate crisis when every responsible policy maker I know talks about ways we need to reduce our carbon usage and our carbon footprint,” Gallicchio said. She said that when she brought up these concerns to Elicker in a July 2022 meeting with him and Economic Development Administrator Michael Piscitelli, she was quickly dismissed.

“[Piscitelli] said that global warming is a global problem and this is a local issue,”

Gallicchio said. Piscitelli did not recall this conversation and referenced the potential local environmental benefits from moving the terminal—including higher stormwater storage capacity at the airport. Elicker also contested that this is his administration’s position. “[Planes] have jet fuel that is detrimental for the climate,” Elicker said. “But that doesn’t mean we should never fly anywhere. We can’t look at the airport in isolation and there is so much we are doing as a city to reduce our climate impacts.”

The current expansion put forth by Avports includes plans for a six-story parking garage, a 638-foot runway expansion, a 462,500 square-foot airplane parking building, and the new terminal that will come in at around 80,000 square feet. Residents and environmental activists alike fear the potential harm this construction will have on surrounding wetlands, and also the prevalence of flooding. Low-lying and coastal East Haven is already a flood-prone city, with almost a third of homes at severe risk of flooding within the next thirty years. The new terminal will be built on stilts to protect against future water damage. This is still a rare design for airport terminals, but one that might become more popular as flood risks from climate change increase.

Throughout the three-year expansion fight, opponents have complained that everyone seems to be paying attention to other things, anything but Tweed, including those who are tasked to legislate on it. At an April 2023 meeting of the South Central Regional Council of Governments, East Haven Mayor Joseph Carfora accused his colleagues of negligence as they voted to pass a resolution in support of the Tweed expansion and the draft Environmental Assessment.

“First of all, I want to ask everyone on this board,” Carfora said to the assembled council. “Has anybody read this EA ?” It was a hybrid meeting—Elicker called via Zoom from his New Haven office. Carfora held up a copy of the 216-page draft environmental assessment document, spiral bound with a plastic cover. “Has anybody took the time out to read this?”

Hoey and Elicker responded that they had read most of it, but only two other people in the adjoined crowd raised their hand, both onlookers, not members of the council. “I want to ask all of you,” Carfora then said. “How can you vote if you don’t know what’s in this?” The rest of the members looked on, a few holding on to their hands, as Carfora continued to speak, growing irate. Carfora cursed, and only then did

Elicker chime in.“Point of order,” he said. “If we could all use appropriate language.”

Carfora’s motion to table the resolution failed with a 5-4 vote. He stood up and, along with two staff members, left the meeting. The council then voted on the original resolution in support of the Tweed expansion and draft environmental assessment. It passed unanimously, though two members abstained: North Haven First Selectman Michael Freda and Woodbridge Deputy First Selectwoman Sheila McCreven.

Although half the airport sits within East Haven’s borders, ownership belongs solely to New Haven. Legal jurisdiction and regulation largely fall on the federal government, as is the case with airports around the country. “This is lopsided,” Carfora said before he left the April 2023 meeting. “Every time I look back at this I’m getting more information. Everything is twisting and turning and it’s all against East Haven.” One aspect that East Haven does have a small amount of control over is the Tweed Airport Authority Board of Directors, a group of fifteen unpaid volunteers appointed to govern the airport.

Of the Board’s fifteen members, eight are appointed by The New Haven Mayor’s Office with confirmation from the Board of Alders, five are appointed by Carfora of East Haven, and two are appointed by the South Central Regional Council of Governments ( SCRCOG ). The Board governs Tweed and appoints the Executive Director, although since the

forty-three-year Avports lease was approved, its day-to-day responsibilities have shrunk. The Authority and the Board do accept noise complaints from residents, who also can send them directly to the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection through a complaint line. Board meetings are also open to the public, and the board reserves time for comments and questions from individuals, but they rarely respond directly to public comments. More often than not, individuals are referred to the FAQ page on the website.

When Carfora walked out of the SCRCOG meeting on April 26, 2023, he couldn’t stop the council from passing a resolution in support of the Tweed expansion and draft environmental assessment. Ironically, Avports, which leases Tweed from the Airport Authority, which leases land from the City of New Haven, did not need the SCRCOG’s vote of support to proceed with its expansion plans.

As a certified airspace, Tweed is under the specific jurisdiction of the federal government, specifically the FAA , which regulates the American aviation industry. The administration’s primary duty is to guarantee the safety of planes and passengers in the air. To ensure this, it manages air traffic control, regulates planes and airlines, and issues licenses to pilots. The organization’s main goal, as stated on its website, is “providing the safest, most efficient aerospace industry in the world.”

In East Haven, more than 21 percent of children have asthma compared to just 14 percent in New Haven and just 13 percent throughout the rest of Connecticut.

To this end, the FAA has conducted its job admirably in New Haven. Air traffic has expanded, becoming more accessible and efficient, and there have been no major safety incidents since Avelo arrived at Tweed. But although the agency has Environmental Programs that ensure airports are up to the standard, environmental protection and regulation is not the FAA’s top priority, nor is it a part of their stated mission. Yet, the FAA is still the only body—municipal, state, or federal— with the ability to definitively find that there

will be no significant impact from the expansion on the land, waters, and people surrounding Tweed.

On September 26, 2023, another federal department got involved in the dispute. Admiral Rachel Levine, the Assistant Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a letter to four FAA officials urging them to conduct an Environmental Impact Statement ( EIS ) for Tweed’s expansion. In addition to restarting and expanding study into environmental and health impacts, the EIS would also necessitate considerably more community input and feedback. In the letter, she references the environmental and health hazards many neighborhoods around Tweed already face, notably their high asthma rates. The letter was issued in September. Three months later, the FAA issued the Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact, with no plans to move forward with an EIS .

Adam Sarvana, the Communications Director for Levine, declined to comment on this story. “At this point we’re going to let the letter speak for itself,” he said. All Levine could do was “strongly recommend the FAA conduct further analysis,” as she wrote in her letter. The power ultimately landed within the internal operations of the FAA .

East Haven and local nonprofit Save the Sound are making one final effort to halt the expansion by appealing the decision to the federal level. If they win, the decision could force an EIS and a much deeper look into the potential impacts than the current EA does. Still, the changes that have already happened— the onset of Avelo, the ten flights landing at Tweed every day, and the increase in traffic and pollution around the airport—do not require any additional permission or approval. They are here to stay.

From Rafter’s perspective, these impacts are not the only ones to consider. He sees Tweed as having an obligation not only to East Haven, but also to communities much farther away—all along the southern U.S. coast where Avelo flies to. That network of the aviation economy, connected by runways, planes, and corporations that easily cross state lines, relies in part on Tweed. On a heavy traffic day, it may take twenty or twenty-five minutes to reach downtown New Haven from Tweed Airport. In that same amount of time, 150 people could be halfway to Baltimore, one of the eighteen Avelo destinations. These transportation routes, as they become more habituated, create a connection between two places, economies, and communities that is no longer dependent upon physical proximity. In Rafter’s air traffic controller office, it’s easy to feel close to the wide sky and the planes crisscrossing it high above.

The ground below is far away.

Gallicchio may be getting ready to leave. The neighborhood she loved, where she raised her three kids and has lived for twenty-five years, has now changed to the point of unrecognition. “I am one of the people with the wherewithal to leave,” she said. “The people who are going to have to stay here and watch their homes and their neighborhood and their physical health deteriorate, it’s depressing.”

Gilman-Ford doesn’t have plans to leave yet, although she has taken a step back from the airport fight. “It’s just consumed me,” she said. “It’s consumed my kids. I took the flight tracker off my phone,” she said. “I must have filed three hundred complaints, I never got one response, not one.” She used to take her kids walking along the Tweed border on Thompson Avenue; she'd point out groundhogs and ducks to them along the path. The trees were cleared in 2020 as part of a drainage plan, and the animals never came back. Now that they are gone, Gilman-Ford is letting her own garden grow at her house one block away. The garden is overgrown but she doesn’t want to cut down the rhododendron bush—rabbits recently moved in. “I’m going to be the idiot that leaves all the crappy brush on my front yard,” she said. “I don’t want to kill the animals.” Above her, in the sky, the air boomed as another Avelo 737 came in for landing. ∎

Meg Buzbee is a senior in Pierson College and a Podcast Editor of The New Journal.

A writer seeks out authentic Chinese cuisine guided by Chef Jiang, the man behind his eponymous restaurant.

Everything at Chef Jiang seems designed to reflect light. The glossy wooden tables, the seats upholstered in shiny orange vinyl, the oversized oriental vases. Even the plates of food—hot, spicy, and glistening with oil—have become surfaces of refraction.

In one photo from a profile online, Chef Jiang’s owner, Jiang Zhongshan, wears a black chef’s uniform and a white cap, and he drapes his arm commandingly over the side of a chair. In person, however, he is quiet, slow-speaking, and straight-faced—in a black zip-up hoodie and white athletic shoes. He tells me that he spends most of his time thinking about the restaurant, its workers, and its customers. I ask him if he has any funny stories, and he shakes his head. I ask him if he has ever dealt with any bad customers, and he shakes his head again. He does not seem accustomed to talking about himself.

Jiang doesn’t speak English. The first thing the restaurant’s hostess asked me when I called to schedule an interview was if I spoke Chinese. I told her that I did. That is technically true. My Chinese is good, although not as good as it should be—which is to say, not perfect. Throughout my interview with Jiang—conducted entirely in Chinese—I sometimes have to ask him to repeat himself. He does so generously. Because we so often

hear about the pressures of the professional kitchen, it is easy to forget that cooking is a skill that takes a lot of forgiveness. Jiang watches as I stop in the middle of a sentence and wave my hands abstractly, searching for a way to rephrase my question. He says nothing, only smiles and waits.

Before Chef Jiang took up residence on 67 Whitney, the building was occupied by Great Wall Restaurant, a Chinese restaurant that closed down in June of 2023, after sixteen years of business. I ate there only once. It was their brunch special: a classic combination of soymilk, congee, and youtiao. I remember the tile floors and the overhead fluorescent lights. Because the restaurant was under renovation, my friends and I ate our congee out of small transparent containers with white plastic spoons.

In comparison, Chef Jiang incarnates a different, shinier version of the Chinese restaurant. “I wanted to have a place that felt modern,” Jiang tells me. Sure, there are still remnants of traditional Chinese restaurant kitsch—the neon OPEN sign in the window, a faint jazz cover of “Don’t Stop Believing” playing over the speakers—but for the most part, the space looks like something that has just been unwrapped from its plastic.

Jiang is as much a businessman as he is a cook. He tells me that every

aspect of the restaurant’s physical design was carefully planned and that food is only one part of the dining experience. Jiang understands something about his customers: they value the aesthetics of the thing almost as much as the thing itself. He shows me the restaurant’s Instagram page; one reel showcases shining interiors alongside shots of chow mein, dumplings, and fried rice, all filmed aggressively up close. The video cuts to a shot of orange chicken in time to the beat of Beyoncé’s “ MY HOUSE.”

Jiang grew up in Hunan, a province known for its spicy cuisine, and comes from a culinary family: his father was a chef, as was his grandfather. He attended culinary school and went on to work at an elite restaurant in Beijing. Hearing that economic possibilities were more plentiful in the U.S., he immigrated alone from China to the East Coast in his thirties. His wife and daughter joined him five years later, while he was working at a small Chinese restaurant in New Jersey.

“Not everyone who opens a restaurant will succeed. If you are lucky enough to have a restaurant, what’s the point in thinking, some fourteen years later, that you wish you hadn’t done it?”

A couple years ago, Jiang heard about a lease in Farmington and decided to open Chef Jiang’s first location in 2021. Whitney Avenue is his second location, which he selected in part to cater to Yale students. He has his eye on Providence—and Brown University—for his next restaurant.

I ask Jiang about his regrets; he says he has none.

“I’ve never really thought about it. I’ve never asked myself what I would have been if I hadn’t become a chef,”

Jiang tells me. “The journey was so hard—really, really difficult—and required sacrifice. Not everyone who opens a restaurant will succeed. If you are lucky enough to have a restaurant, what’s the point in thinking, some fourteen years later, that you wish you hadn’t done it?”

I don’t ask him about sacrifices. When we’re not talking about the restaurant, the conversation ends quickly— perhaps, it seems to me, because he doesn’t have much to say. He briefly mentions his daughter, Lily, who will be graduating high school in the spring. Even though they are no longer separated by the Atlantic Ocean, he doesn’t get much time with her between her schoolwork and his restaurants.

“We aren’t very close,” Jiang tells me.

On the weekends, Lily sometimes takes up shifts as a host and waitress. She is not as shy as her father. “He doesn’t speak to me much,” she says in English, after I ask her about their relationship.

Still, when Jiang stops by to check on us as we chat, Lily turns to smile at him.

“What are you talking about?” he asks us.

“We’re badmouthing you,” she says, laughing, and he places his hand on her shoulder in the specific way that fathers do: fondly and with weight.

When I ask Lily to describe her father, she immediately tells me that he is very serious. When I ask Jiang to describe himself, he thinks for a moment, and then says that he considers himself a kind person. This makes Lily laugh. Nevertheless, I think that I understand what he means. Jiang rises to bring me a mug of tea the second that I sit down to interview him. He insists that I take home some food after every meeting. He tells me that his favorite person to cook for is anyone who enjoys his cooking.

The dish that is most important to Jiang is not on the menu. A stir-fry of tofu and pork is too simple to be served at most restaurants. It’s a nameless food—the sort that people cook at home. My mom makes it; Jiang’s mother made it too. As a child, his family could only afford to eat the dish once a month. They bought the pork from a man who sold meat door to door, carrying it on his back with a wooden pole.

Jiang understands that food is situational and taste is temporal. His mother’s tofu dish exists in the past. It is the kind of thing to which he can never quite return.

Now Jiang tells me that he does not make the dish at home. He can never recreate the flavor.

“It wasn’t that the dish even tasted that good,” Jiang says. “But I was a little kid, and I only ate it once a month.”

Jiang understands that food is situational and taste is temporal. His mother’s tofu dish exists in the past. It is the kind of thing to which he can never quite return.

Igrew up eating at a lot of Chinese restaurants. These places were usually family-owned. They were almost always carpeted and decorated with fake plants. Some featured aquariums of large fish, and as a child, I was always worried that these fish were the same ones that would end up on the revolving table an hour or so later.

Among my family and our circle of friends, the highest praise that you could give a Chinese restaurant was to say that it was authentic. I considered authenticity the rallying cry against Americanized Chinese food, exemplified in my mind by chow mein and anything else served at Panda Express. It wasn’t even that I disliked Panda Express; in fact, I harbored a secret longing for its orange chicken and honey walnut shrimp. Still, I understood that enjoying “fake” Chinese food was the sign of being a “fake” Chinese person. The most hurtful insult of my childhood was whenever my dad, disappointed at my rejection of delicacies such as chicken feet or pig ears, would sigh and say to me, “I guess you really are an American.”

Articles reviewing Chef Jiang online make sure to highlight the restaurant’s more exotic dishes: gizzards, frogs, stinky tofu. I wonder if the perceived abnormality of these foods is meant to indicate their authenticity, as though the sign of a properly foreign meal is that it seems instinctively unappealing to the traditional American palate. I wonder, also, when Americans started caring so much about the legitimacy of ethnic food anyways.

Online, I watch a segment of a local news station from one month ago. In the video, Jiang stands alongside his marketing manager and two news anchors before four platters of food. “A lot of us are getting Chinese food, but we’re not getting the real Chinese food,” one of the news anchors explains.

That’s the selling point: authenticity. The food is real because the tofu is spicy and the fish comes with its head still attached. Jiang’s marketing manager tells the anchors that these are examples of dishes that Chinese people might cook at home, and the anchors marvel at how different this food is from the Chinese food that they had always known. Throughout the video,

I watch Jiang. He says nothing, just smiles and chuckles. Everyone else is speaking in a language that he does not understand.

...when we say that food is authentic, what we mean is that it tastes like something we have tasted before. That’s all it really is. Just the commonplace longing for something that you already know.

Jiang tells me that he adjusts his cooking to be more accessible for American customers. In addition to lowering spice levels, he has also included in his menu a section devoted to Americanized Chinese food staples like General Tso’s chicken and Mongolian Beef. Most American customers, he reasons, will first come to Chef Jiang for these familiar dishes. But

when they come back, they might try something more adventurous, and then they’ll keep coming back to try new things, and they’ll bring their friends along, and this is the slow process of teaching Americans what Chinese food really is, so that someday, maybe Jiang won’t need to put General Tso’s chicken on his menu.

In the meantime, though, he tells me that he isn’t particularly bothered by questions of authenticity.

“I just want people to eat here,” he says.

In Chinese, when you call something authentic, you say that it is dìdào. The word itself is constructed of two characters, one meaning “land,” the other “road.” This makes me think about how the concept of authentic cuisine never would have existed if people hadn’t traveled so far away from their own native lands. The original use of the term, dating back to the Ming dynasty, was actually as praise for products of a certain locale. Since then, however, dìdào has taken on an additional meaning: that which is

tangible or real. To me, there is something that feels so Chinese about this— the idea that truth must be intimately tied to home.

I eat dinner at Chef Jiang twice in the span of two weeks. The first time, I wait half an hour on a busy Saturday night to get a table with two friends, neither of whom are Chinese. We order scallion pancakes, chow fun, stir-fried lamb, bean sprouts, and Dan Dan noodles. As we eat, I find myself informing them that this is the good stuff, the real deal of Chinese cuisine. By the end of the meal, we are exhausted—both from eating and from talking about how excellent the food is.

My second dinner at Chef Jiang is during the Lunar New Year, upon the invitation of a family friend—a Chinese professor at Yale. She is from Shanghai and is probably the best cook I know. I ask her how she recognizes when a dish is authentic or not. “I only really know if I’ve had it before,” she says, which I understand as her graceful way of telling me that my question is a poor one.

In the middle of dinner, I take a quick trip to the bathroom. In one corner, there is a palm-like plant in a dark

blue ceramic pot. I reach down to press my fingers against the roots. I feel the smoothness of the plant and the softness of the dirt. It’s real.

After our first interview, Jiang insists that I bring some food back to my dorm. From the menu, I select the wontons in chili oil, which he packs up for me in a black plastic container.

If you want to know the truth, I have no idea if the food at Chef Jiang is authentic or not. I haven’t been back to China in close to ten years. When I go out for dinner with my non-Chinese friends and try to explain whether the scallion pancakes are real or unreal, it’s an exercise in bullshit, the indulgence in a feeling of expertise that I can claim and others cannot. This is one of the pleasures of tribalism—the ethnic secret, the esoteric knowledge, the self-aggrandizing idea that my taste buds actually do have some instinct for truth.

We never even made scallion pancakes at my house. Instead, we bought them frozen from the Chinese grocery store and heated them with slices of cheddar cheese melted blasphemously on top.

…that summer and the swollen pregnant heat, when Isa and I would walk around the house in our underwear and spend our water bill in the cavities of those hard plastic ice trays, that summer when I had two jobs and there was no poetry left in me by sundown, that summer when we’d keep the windows cracked open and every Saturday the dirt bikers would roar down the road and rattle all of our mismatched kitchenware, that summer I let seashells collect on the bathroom window, that summer I broke the wheels of my parents’ best suitcase bringing thirty-five books back to the library, that summer I waited for you to drive up to me on the weekends, that summer I started a fire by the lake and all of my clothes smelled like smoke and clean tobacco, that summer the man started following me, that summer the shape of my body changed, remember that one?

—Lucy TonThatBut when I sit on my couch and eat Jiang’s wontons, I remember making wontons at my kitchen table, and also the restaurant back at home where my mom used to order this same dish for me after school. I think about how these wontons taste like something familiar. And how, when we say that food is authentic, what we mean is that it tastes like something we have tasted before. That’s all it really is. Just the commonplace longing for something that you already know.

“Exactly,” Jiang says, when I try to explain all this to him at the end of our last interview. He nods at me, as though in approval. “Authenticity is just what we say about something that makes us think of home.” ∎

She believes in the Virgin the way I believe in the mountain, though in one case the fog never lifts.

But each person stores his hope in a different place.

– Louise GlückI went to the service because I wanted to sing hymns. My sophomore fall had been a warm one. I spent it reading into texts from a girl I wanted to be with, drinking purple gin and minty tea, and not thinking about any higher power. I hadn’t been to church since I declared my atheism at 13. But then it was December. I was alone, and the afternoons were dark. I wanted music that sounded like light.

I dragged my friend Lucy to the Christmas service on campus. We sat on the balcony. Below us, poinsettias lined every aisle and window sill. Their symmetry pulled the music into a new sphere; the air seemed to purr. Before “Silent Night,” we watched the light unfurl candle by candle, each congregant passing their flame to the next. I let wax drip onto my fingertips. We pretended not to notice the shake in each other’s voices.

After the service, we ate takeout and Lucy read me a poem by Ada Limón:

And I think of that walk in the valley where J said, You don’t believe in God? And I said, No. I believe in this connection we all have to nature, to each other, to the universe. And she said, Yeah, God.

We pasted this into a document and named it “religion.” Today it is thirty-nine pages long, filled with prose

and poems written by women we love. We add a piece of writing if it makes us feel this connection we all have: to nature, to each other, to the universe.