For decades, Margaret Holloway performed Shakespeare on the corner of York Street in exchange for money. Behind the mythos of “The Shakespeare Lady” was a budding actress failed by a series of places and people—including at the Yale School of Drama.

Dear readers,

As the future abounds for the new faces on campus this August, the Managing Board convened in a slightly more reflective mood. Juniors now, we have crossed the halfway mark in our journeys at Yale, and it’s prompted us to take a look back.

So too do our writers. Memory is the central theme of this issue of The New Journal. How do we mine meaning from the lives of those who have passed––and when do these stories spin out of control?

Chloe Budakian tells the story of Margaret Holloway and explores how her legacy as York Street’s “Shakespeare Lady” has been flattened and narrativized after her death. In his piece on Father Michael McGivney, Ethan Wolin chronicles the transatlantic endeavor to make a saint of a 19th-century American man—a canonization effort spanning the edges of the American East, Italy, and the internet.

Throughout the city, people contend with history and tradition. Collegiate shooting athletes exercise their privilege to compete amidst a national debate over bearing arms; mothers of gun violence victims root trees and flowers to memorialize those they have lost. Meanwhile, New Haven’s burgeoning biotechnology scene prompts us to ask: can the city learn from its past?

In this first issue of Volume 57 of The New Journal, join us in looking back.

Managing Board

Maggie, Chloe, Aanika, Sam

Thank you to our donors

The Elizabethan Club

Mark Badger Kathrin Lassila

Jean-Pierre Jordan

Aliyya Swaby

Laura Heymann

Jeffrey Pollock

Julia Preston

Armand LeGardeur

Katie Hazelwood

Benjamin Lasman

R. Anthony Reese

Andrew Court

Fred Strebeigh

Peter Phleger

Steven Weisman

David Greenberg

Suzanne Wittebort

Romy Drucker

James Carney

Makiko Harunari

Editors-in-Chief

Maggie Grether

Chloe Nguyen

Executive Editor Aanika Eragam

Managing Editor Samantha Liu

Business Manager

Alex Moore

Verse Editors

Ingrid Rodríguez Vila Etai Smotrich-Barr

Senior Editors

Jabez Choi Paola Santos

Viola Clune Kylie Volavongsa

Abbey Kim Anouk Yeh

Associate Editors

Chloe Budakian Tina Li

Ben Card

Koby Chen

Sophia Liu

Hannah Mark

Ashley Choi Calista Oetama

Matias Guevara Ruales Josie Reich

Mia Rose Kohn Jack Rodriquez-Vars

Sophie Lamb

Copy Editors

Sara Cao

Lilly Chai

Sophie Molden

Sasha Schoettler

Diego del Aguila Vivian Wang

Sophia Groff

Podcast Editor Suraj Singareddy

Creative Director Alicia Gan

Design Editors

Ellie Park

Sarah Feng

Jessica Sánchez

Photography

Colin Kim

Web Design

Laura Pappano

Marilynn Sager

Blake Wilson

David Gerber

Daniel Yergin

Barak Goodman

Daniel Brook

Eric Boodman

Stuart Rohrer

Ashley Zheng

Vivian Wang

Gavin Guerrette

Makda Assefa Kris Aziabor

Caleb Nieh

Members & Directors: Emily Bazelon • Haley Cohen

Gilliland • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • Jonathan Dach • Susan Dominus • Kathrin Lassila • Elizabeth Sledge • Fred Strebeigh • Aliyya Swaby

Advisors: Neela Banerjee • Richard Bradley • Susan Braudy • Lincoln Caplan • Jay Carney • Joshua Civin • Richard Conniff • Ruth Conniff • Elisha Cooper • David Greenberg • Daniel Kurtz-Phelan • Laura Pappano • Jennifer Pitts • Julia Preston • Lauren Rawbin • David Slifka • John Swansburg • Anya Kamenetz • Steven Weisman • Daniel Yergin

Friends: Nicole Allan • Margaret Bauer • Mark Badger and Laura Heymann • Anson M. Beard • Susan Braudy • Julia Calagiovanni • Elisha Cooper • Peter Cooper • Andy Court • The Elizabethan Club • Leslie Dach • David Freeman and Judith Gingold • Paul Haigney and Tracey Roberts • Bob Lamm • James Liberman • Alka Mansukhani • Benjamin Mueller • Sophia Nguyen • Valerie Nierenberg • Morris Panner • Jennifer Pitts • R. Anthony Reese • Eric Rutkow • Lainie Rutkow • Laura Saavedra and David Buckley • Anne-Marie Slaughter • Elizabeth Sledge • Caroline Smith • Gabriel Snyder

Meet the stars of the New Haven Independent’s comments section. By Tina Li

Side Effects

Burgeoning biotech development has residents wondering: can the city avoid the mistakes of past revitalization efforts? By Tobias Liu

In the Crosshairs

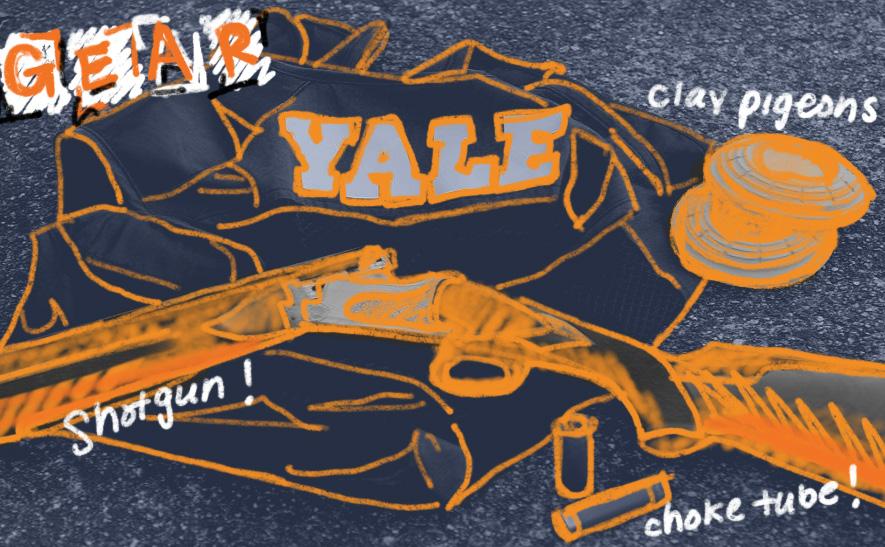

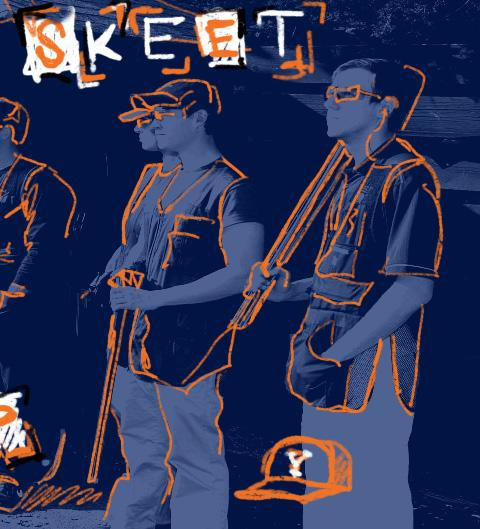

Yale’s Club Skeet & Trap team garners attention from admitted students, alumni—and gun lobbyists. By Abigail Sylvor Greenberg Growing Memory

The first of its kind, a garden in New Haven remembers local victims of gun violence. By Calista Oetama

The quest for sainthood for a 19th-century Connecticut priest ensnares a cast of characters across continents–and could transform New Haven into a center for American Catholicism.

By Ethan Wolin

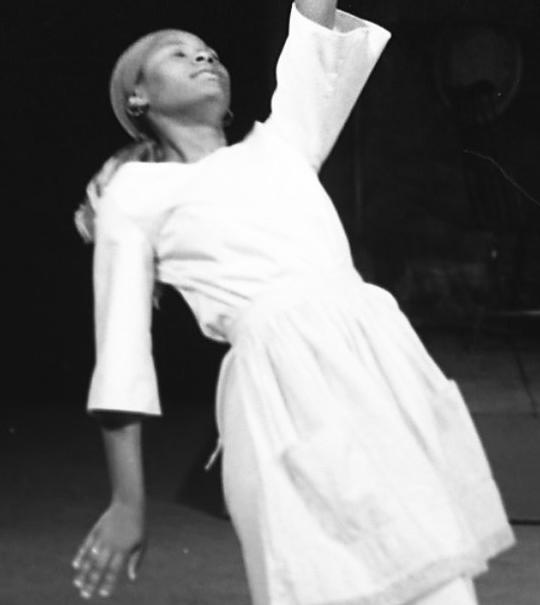

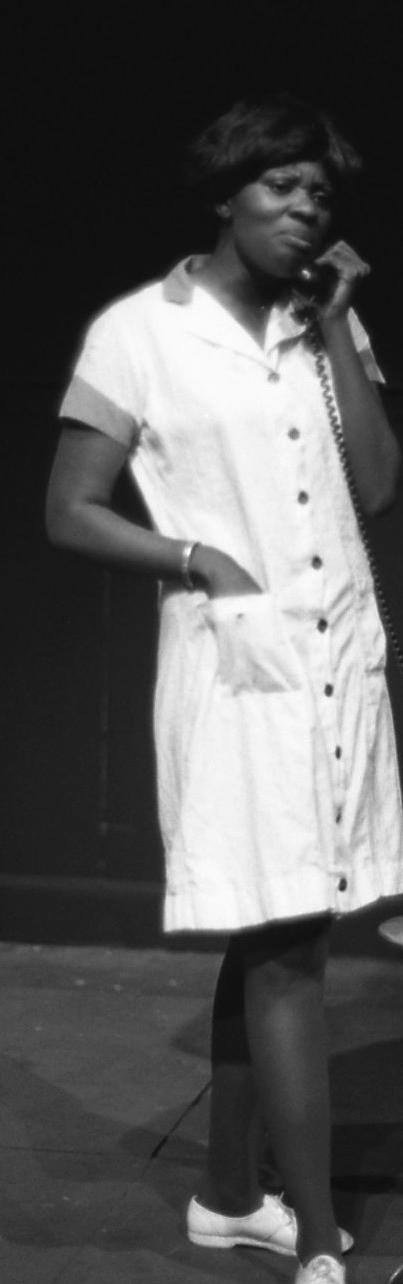

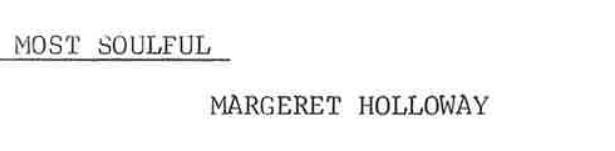

For decades, Margaret Holloway performed Shakespeare on the corner of York Street in exchange for money. Behind the mythos of “The Shakespeare Lady” was a budding actress failed by a series of places and people—including at the Yale School of Drama.

By Chloe Budakian

Brooke Whitling Becoming a Crew Man

Tigerlily Hopson

Anaiis Rios-Kasoga

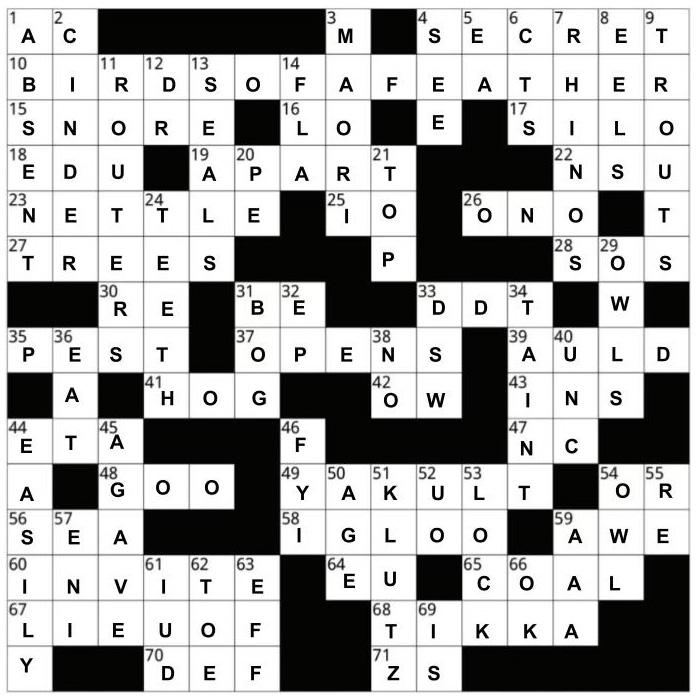

Themeless Toughie, page 39.

Meet the stars of the New Haven Independent ’s comments section.

In 2012, the New Haven Independent faced what its founder, Paul Bass, would remember as “a moment of truth.”

The online paper’s comments section had been deteriorating into a cesspool of unwieldy toxicity and petty personal jabs. One day, a particularly nasty attack on a public official slipped past Bass, then-editor-in-chief. The damage was irrevocable. With a stricken conscience, he removed the commenting option.

For a week, the Independent’s website was eerily silent. No longer were people engaging in zealous debate under articles or providing prompt feedback to writers. They instead took to Bass’ email inbox, which was flooded with letters from devastated commenters, media critics, and editors of other local papers.

In an Independent staff meeting the following week, Bass was outvoted 11 to 1 in reinstating the comments section. Though hesitant, Bass soon realized that it was simply a matter of strictly enforcing community guidelines and owning up to the inevitable mistakes.

“In that process, we learned how important a moderated comments section is,” Bass said. “Readers really deserve more of a say in the direction of coverage. We just have to be able to moderate it well.”

If you live in New Haven, you’ve likely heard of the Independent—the site receives approximately 70,000 unique visitors each month, half of the city’s population of 140,000. Unlike its peer news sites, which are often owned by media conglomerates and have succumbed to homogeneously modern designs and paywalls, the Independent’s

website resembles an early 2010s WordPress blog. Community notices and hyperlinks, all typed in humble Arial font, densely populate its side columns.

Though the Independent ultimately restored its commenting option, the New Haven Register and Hartford Courant had long struggled with hostile comments and eventually shut down their comments sections for good. The decisions were understandable. Comments sections are liabilities for small papers, Bass told me, as each comment that borders on libel can provoke a defamation lawsuit.

With rigorous moderation, the Independent’s comments section is thriving. At the bottom of every article, readers can express their disapproval and disillusionment with New Haven— but also join together in a fierce commitment to the city. “Some people call it their favorite public forum in New Haven,” Assistant Editor Dereen Shirnekhi told me (Shirnekhi was editor-in-chief of The New Journal during the 2022-2023 academic year).

Articles about contentious issues garner immense engagement. A piece covering protests over the war in Gaza

received 134 comments, and recent articles about the Rosette Street tiny homes’ residents fighting to retain their permits consistently received about sixty each. Though lighter-hearted pieces receive less attention—on average about a dozen or so comments—the same commenters who duke it out under politically controversial articles might share their common appreciation for a successful youth reading event on the New Haven Green.

The commenters are lively, opinionated, and sometimes snarky. Some write long paragraphs with links to Connecticut law or news clippings. Others share personal experiences. According to Shirnekhi, frequent commenters become “characters.”

If that’s the case, then user @Kevin McCarthy has a starring role.

Weaving around a U-Haul truck, McCarthy waved at me from his scuffed-up violet bike. He just came back from a shift of packing food at Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services, and he’s wearing a checkered Timberland button-up tucked into khakis, which are then tucked into work boots. Ever since he retired, McCarthy cruises around New Haven,

dividing his time among multiple nonprofit organizations.

McCarthy likes biking, cats, and the New Haven Independent comments section. As he talks, his fluffy eyebrows leap above his wire-frame glasses.

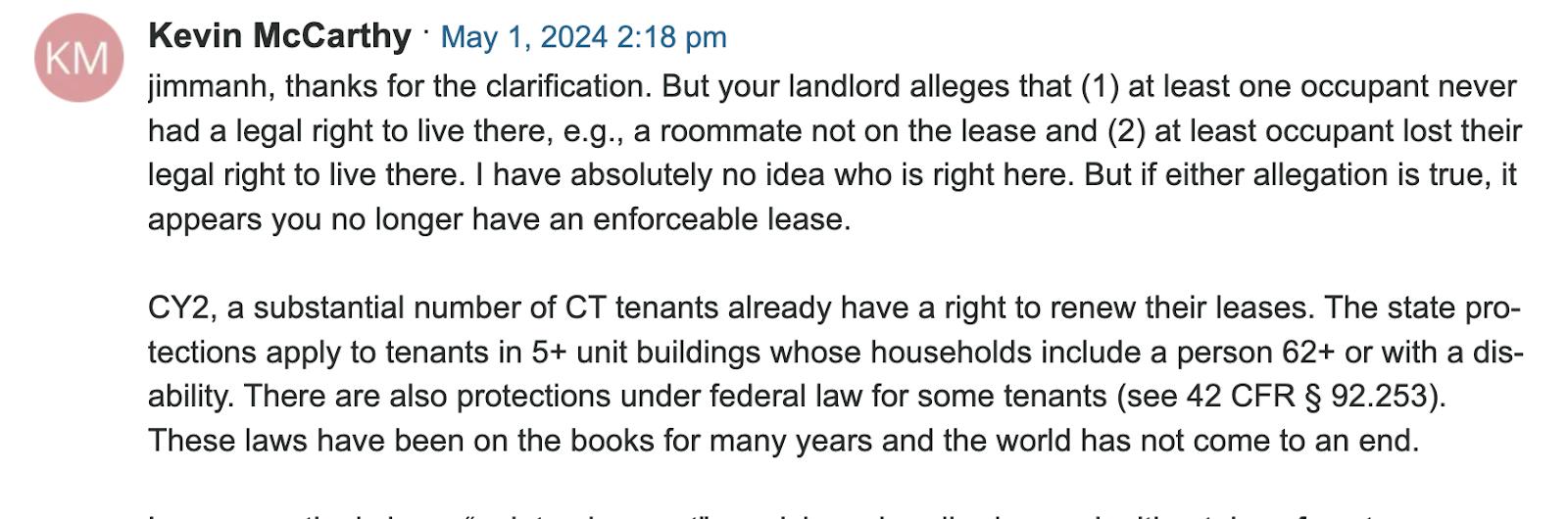

He’s known in the comments section for being judicious and impartial. During his tenure as a policy analyst in the Connecticut legislature, McCarthy became well-acquainted with issues from land use and housing to transportation and energy. It was essential, he told me, that his writeups were bipartisan. With his experience, he brings to the comments section a pragmatic understanding of city issues as well as an extensive knowledge of legalese—under an article about tenant union organizer evictions, McCarthy still cites federal and local regulations like a researcher: “(see 42 CFR § 92.253).”

His dedication to New Haven and his reliable, informative presence in the comments section landed him his own profile in the Independent . Under the article, his fellow commenters praised him as a “local treasure” and “hometown hero.”

Ben Trachten, a land use attorney, met McCarthy at a city planning commission meeting. Since then, they’ve regularly met for coffee to debate the technicalities of New

Haven’s housing issues.

“We always come up with good dialogue and a good set of ideas to move New Haven in the direction that we want to see it go: more residential density, more residential

on running around New Haven to uncover information, with which readers can then form their own conclusions. The comments section thus becomes a space where commenters run their own quasi-opinion columns.

“When you start thinking your opinion matters more than the news or other people’s opinions, it makes you less useful,” Bass said, describing the accountability they receive from commenters as “liberating.”

The comments section has also inspired change at the grassroots level. Bass fondly told me about a late commenter Rebecca Turio, or @cedar hill resident, whose passionate advocacy

choice,” Trachten told me.

Besides being a forum for open dialogue, the comments section has also become an authority check on the Independent’ s writers. Commenters don’t hesitate to provide technical corrections or criticize articles they find biased. The writers of the Independent don’t editorialize; instead, they focus

in her comments was informed by her having lived in a lower-income neighborhood. Through engaging with Independent articles and other readers, she grew more invested in activism and would attend city meetings proudly proclaiming her identity as a commenter—“I’m @cedar hill resident!”

In a city dominated by progressives, software engineer Joshua Van Hoesen stands out in the comments. In 2023, when he was campaigning for alder in Ward 26 as a Republican, he used the Independent ’s comments section to expound on his values—“old school, fiscally responsible, [and] moderate,” he told me. Van Hoesen tells me that his views were frequently challenged and even changed as he interacted with other commenters.

But Dennis Serfilippi, who ran for Ward 25 alder as a Democrat in 2019 and 2023, isn’t convinced that the comments section inspires significant policy changes. According to

Serfilippi, commenters comprise just a small portion of the populace and occupy a powerless space between the average resident and the New Haven government: more informed than the former, but not taken seriously by the latter. “Until more people get involved and understand what’s happening, then things won’t change,” Serfilippi told me.

When I asked these commenters whom they interacted with most, each immediately rattled off several names. Everyone seemed to have contentious dialogues with @CityYankee2, a staunch Republican and infamous online contrarian. McCarthy told me he occasionally disagrees with @THREEFIFTHS, a Black man from New York City, but the two are Facebook friends. He also knows @Patricia Kane, who ran for alder as a member of the Green Party in 2021.

Patricia Kane confessed that her early interchanges with McCarthy in the comments section were antagonistic. One day, wanting to smooth things over, he suggested they meet up over coffee. Though they’ll still agree to disagree, they’ve been friends since.

“I ended up mending his Irish knit sweater,” Kane said.

Like many other commenters, Kane is deeply committed to supporting independent journalism and demanding transparency from local and national governments. She believes that the New England tradition of spirited town hall meetings endures in the Independent ’s comments section.

Kane moved to Mexico two months ago. She now lives two hours behind New Haven and thousands of miles away, but she still fondly keeps up with the local happenings and all her fellow commenters—friends and adversaries alike. Though she doesn’t comment anymore, Kane hasn’t been able to detach from the community here.

Every morning in Mexico, without fail, Kane logs on and checks the Independent’s comments section. ∎

Tina Li is a sophomore in Pierson College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.

The difference between him and his mother is God believes in his mother.

He says he is not his mother but he conceives of the dead the way his mother does at sixty; his dreams glance to the rear and flanks (where danger waits) and his ear hears: it hurts

“Your father likes this dish. This Sunday is Father’s Day. Why you’re not coming home? Why my four boys are the smartest boys in the world and can’t help me?”

The difference between him and his brothers is his brothers believe in his mother.

By Brooke Whitling

We grew up sitting in the back pew, for the most part anyway. Sometimes it felt like we shouldn’t, like we were sitting the furthest from the message too. Like, because we could slip out without anyone seeing—the preacher’s family or the old people—we weren’t really there.

I remember the building and the part of the service where the pastor brought all the kids up to the front for the children’s thing. And the puppet shows. And we sang up there, performed for the congregation. And he would make it fun…

squeezing toothpaste to show us we can’t take our words back. And downstairs in the basement there was a hangout place, and upstairs the frog room. It was an acronym…

FULLY RELY ON GOD, or something. Only the teenagers could go to the basement, where there was a foosball table and the walls were all covered with murals. I never made it down for the big kid stuff. We stopped going so much after when I was in the frog room and the guy giving the lesson told us that everyone divorced was going to hell, and so I asked if God understands sometimes, you know, if it’s better for the

kids or the parents or everyone because maybe the situation wasn’t healthy and he knew my mom got divorced when I was little, but he said no anyway.

She was going to hell too.

And I didn’t tell my mom because I didn’t want her to know. Not that I cried in the frog room—I didn’t want her to know about hell. So I walked over to the water fountain after, and it tasted like iron. ∎

Brooke Whitling is a sophomore in Timothy Dwight College.

The quest for sainthood for a 19th-century Connecticut priest ensnares a cast of characters across continents–and could transform New Haven into a center for American Catholicism.

By Ethan Wolin

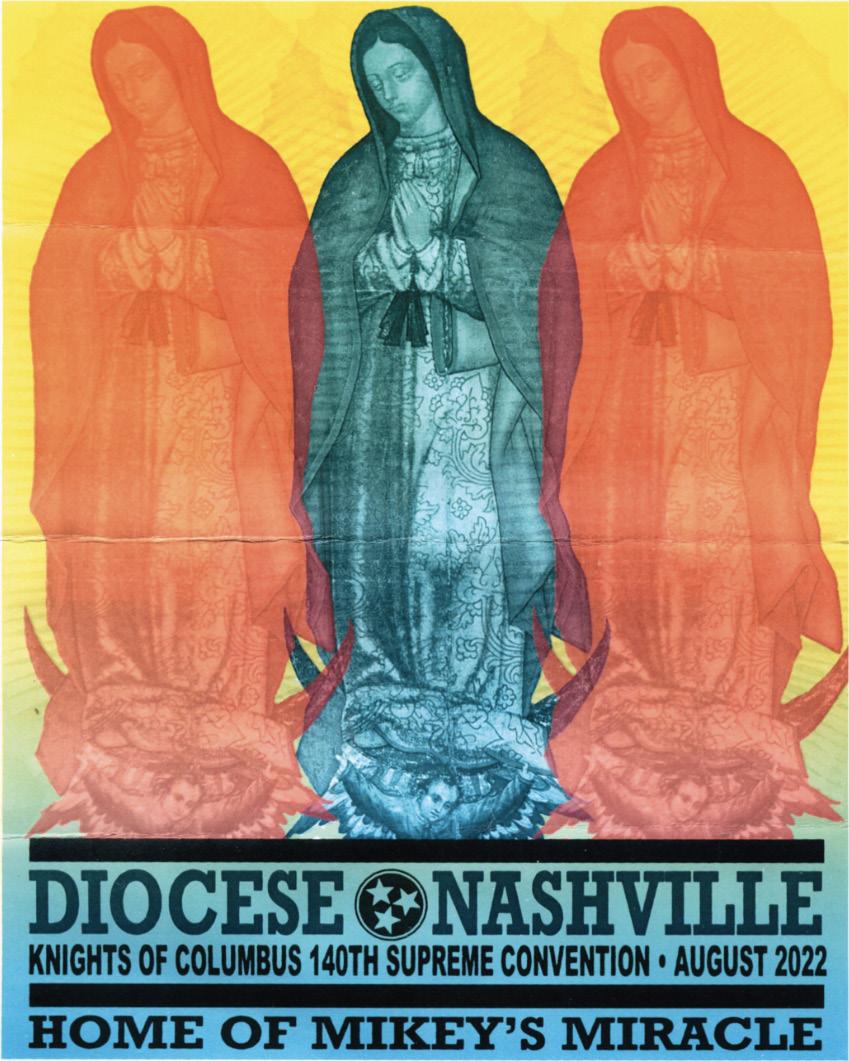

Twenty weeks into her pregnancy, in February 2015, Michelle Schachle and her husband Daniel were told their baby would not survive. An ultrasound had revealed severe fluid buildup that risked harming Michelle, too. Doctors at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center recommended terminating the pregnancy. For the devoutly Catholic couple, abortion was off the table. The suggestion angered Dan. “It’s my job to protect my children, not to kill them,” he recalled thinking. The Schachles made worstcase plans to bury the baby in their yard, in rural Tennessee. And they began to pray. They prayed for Father Michael McGivney, a 19th-century Connecticut priest, to press God to intervene on the fetus’s behalf. In 1882, McGivney founded the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s organization that sells life insurance. Inspired by McGivney, Dan had found his calling as an insurance agent for the Knights, and his sales won him and Michelle spots on a 2015 reward trip to Europe. It came at an opportune time. The couple prayed for McGivney’s aid at the Vatican, and again at the Sanctuary of Fátima, a popular pilgrimage site in Portugal, where they heard a gospel reading in which Jesus tells a nobleman whose son is sick: “You may go; your son will live.”

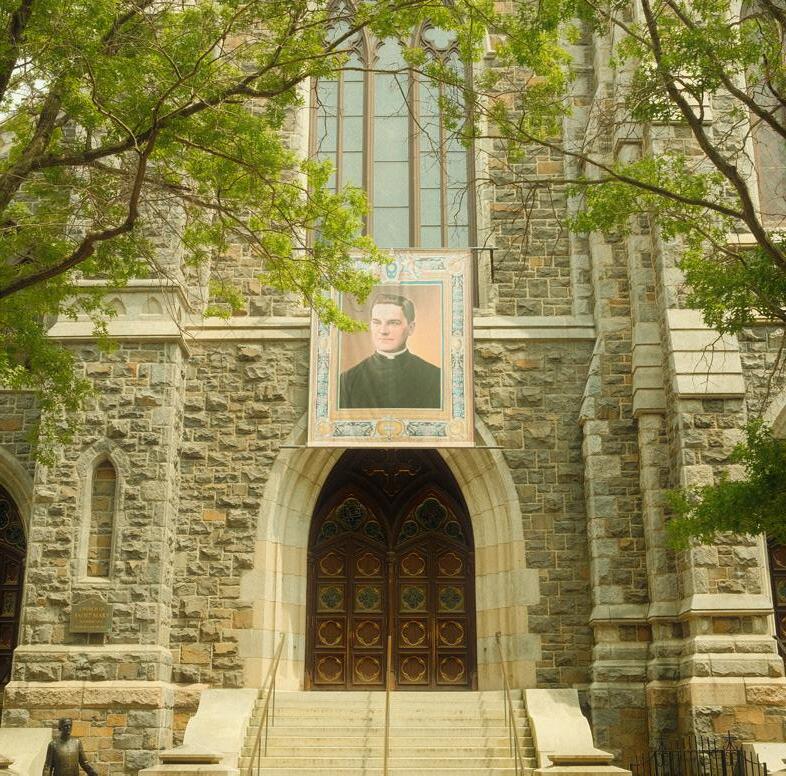

and the face of New Haven Catholic life. It would especially begin to transform St. Mary’s Church, where McGivney and a crew of laymen established the Knights, and where today his body rests entombed and his portrait hangs outside.

McGivney may, before long, become the first American-born man to be recognized by the Vatican as a canonized saint. To join the canon of saints, one must meet centuries-old standards of holiness that confirm one’s eternal place in heaven. Yet the process—driven by efforts and outcomes beyond the dead candidate’s control—draws in a vortex of characters, events and ideas that make up their own canon, a sort of afterlife on Earth. At the end of a saga playing out across the places and cyberspaces of 21st century America, New Haven may emerge as a focal point of Catholicism in the country, and McGivney as a preeminent mold for American Catholic manhood.

Right after they returned from Europe, Michelle had another ultrasound. The swelling was gone. In only the 31st week of pregnancy, she had a C-section, giving birth to a son with Down syndrome. Fear and hope melted into gratefulness. Dan and Michelle named their thirteenth child Michael McGivney Schachle. Ever the company man, Dan called a top Knights executive he had met in Portugal to report the remarkable turnaround. According to Dan, the executive passed the news to a colleague at the New Haven headquarters with a simple message: “I think we might have your McGivney miracle in Tennessee.”

The Knights had already pushed their founder well on the path to sainthood, but the world’s biggest Roman Catholic fraternal group needed two divine miracles to close the deal. The story of the new Michael McGivney— since retold in numerous news articles, Catholic podcasts and Knights videos—would, five years and five months later, bring the former Michael McGivney one step away from sainthood. It would reshape the Knights’ publicity

On May 15, 2015, the day Michael Schachle was born, the campaign for a Saint McGivney received a new breath of life.

Mikey Schachle (pronounced “shackle”) cleared a path through his relatives to jump on the trampoline with his brother and little niece. He repeatedly uttered “buh-ba-beach,” which his brother decoded as “Backyard Beach,” a song from “Phineas and Ferb.” When rain began to pelt down, Mikey, gripping a mini croissant in his right hand, proclaimed, “A rainy day.” He seemed to be everywhere around the house that Saturday afternoon last May, three days after he turned 9, smiling and eliciting smiles wherever he went. Several dozen family members and friends were there to celebrate his sister’s high school graduation and his birthday to boot.

The Schachles live in a big white house with a red roof and a brick chimney. It sits atop a hill on six acres just outside of Dickson, Tennessee (population about 16,000), some 40 miles west of downtown Nashville. When Michelle, 53, called, the guests converged on the living room to say grace. “I usually say God bless the cook, but that would be vain,” joked Dan, 49, who had grilled piles of hamburgers and hot dogs. Dan runs an insurance agency for the Knights of Columbus that spans all of Tennessee and Kentucky, a territory he covers in his four-seat Piper airplane. He entered the business

after reading the 2006 McGivney biography “Parish Priest,” a 200-page chronicle of humble beginnings.

McGivney was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1852, during an era of rampant anti-Catholic prejudice. His parents both immigrated from Ireland, and his father died when McGivney was 20. Within a decade, as assistant pastor at St. Mary’s, McGivney saw other immigrant families suffer the loss of a breadwinner. He envisioned a new men’s club, resembling Protestant-dominated secret societies, that would, as McGivney once wrote, “render pecuniary assistance to the families of deceased members.” “Knights” evoked manly responsibility, and the club’s namesake, Christopher Columbus, was regarded as a Catholic American hero.

The Knights of Columbus would grow to have over 2.1 million members around the world in nearly 17,000 churchby-church councils, whose activities range from community service to military-style pageantry. Knights can reach four degrees of membership that correspond to four guiding principles: charity, unity, fraternity, and patriotism. The local mutual aid society turned into a Fortune 1000 insurance business, formally a nonprofit 501(c)(8) fraternal beneficiary society, with some one hundred twenty-three billion dollars’

worth of life insurance policies in effect.

Agents like Dan Schachle, contracted by the organization’s corporate center, sell insurance products only to other Knights’ families, earning premiums that bankroll charity— such as aid for war-torn Ukraine or natural disaster victims— and political causes related to Catholic teachings. The group spearheaded the 1954 addition of the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. It now leaves its largest political footprint in the fight against abortion, by supporting the annual March for Life and providing ultrasound machines to anti-abortion pregnancy centers.

The evening I arrived in Dickson to get to the bottom of McGivney’s rising prominence, a dozen Catholic men met in their homey parish office to discuss fatherhood over Krispy Kreme donuts. They used a Knights curriculum called “Cor” (Latin for heart) and a Knights video series called “Into the Breach.” “It’s like what the apostle said: ‘Man be the head of your household,’” one man at the table said, roughly quoting Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians. Another referred approvingly to the football kicker Harrison Butker’s viral remarks on masculinity and the domestic role of women. Two of the attendees were Mikey’s older brothers.

Suffice to say, the Schachles were well steeped in—and sustained by—McGivney’s legacy when they turned to him in their 2015 crisis. “It felt completely natural, because I had been asking Father McGivney for his help already,” Dan told me. Mikey is now homeschooled at what the family dubbed the “Father McGivney Academy.” Michelle said he has some trouble reading when his eyes grow tired. (After the life-threatening condition, fetal hydrops, went away, Mikey still needed surgeries to handle complications from Down syndrome.) On the mantelpiece in the Schachles’ living room sit a framed McGivney prayer card and an encased speck of one of McGivney’s ribs.

During the birthday festivities, Mikey sat on the ground in front of the coffee table, one arm on each side of a cake frosted bright green, yellow, and blue. The attendees filled the dark room, as candles illuminated Mikey’s face and his “Bluey” shirt—one of many gifts he received that Saturday afternoon. (I gave Mikey a stuffed panda and ate two of Dan’s burgers.) Everyone sang “Happy birthday,” and then: “May the good Lord bless you, may the good Lord bless you. May the good Lord bless Mikey, happy birthday to you.”

A subset of the Schachle clan arrived the next morning just in time for the 11 a.m. Pentecost Mass at St. Christopher Church, the only Catholic church in the 490 square miles of Bible-Belt Dickson County. Mikey spent much of the service, which was dedicated to him for his birthday, facing backward in his pew. The elderly deacon, delivering his homily, recounted the story of Pentecost before launching into a series of questions. “Do you want to know the truth? Do you want to know what Jesus taught?”

And: “Do you want to be sanctified, to become a saint?”

colloquially, a saint is a very good person—kind, selfless, moral. To Catholics, a saint is someone close to God, a dead person to whom the living can turn for an exemplar of holiness and an ally in heaven. One may aspire to follow them, but formal canonization is the end of a bureaucratic odyssey that no person can bring about for him or herself. Anyway, it would be inadvisable to try. “There’s a paradoxical twist there,” said Carlos Eire, a Yale professor of history and religious studies. “You’re supposed to be humble. You’re not supposed to attract attention to yourself.”

For centuries, church law has required two basic elements for canonization: proof that the candidate demonstrated “heroic virtue” in life, making them qualified for veneration, and proof that they have since interceded to work miracles, usually two medical cures. An authentic healing miracle must pass two tests: Is it inexplicable by medical science? And can it be attributed precisely to the intercessor in question? If yes to both, then the Vatican’s Dicastery (formerly Congregation) for the Causes of Saints deems the event a signal of God’s approval for the canonization effort.

The number of canonized saints is all but impossible to tabulate, but the number tied to the United States—as missionaries here, or later as citizens—can be counted on

two hands. The Archdiocese of Hartford officially opened the cause for McGivney’s canonization in 1997, fifteen years after the Knights’ centennial commemorations spotlighted their founder’s impact. A thousand-plus-page dossier, commissioned by the Knights to show McGivney’s heroic virtue, prompted Pope Benedict XVI in 2008 to declare McGivney “venerable.”

The Knights printed and distributed prayer cards. They had sought out the presidential historian Douglas Brinkley to undertake a McGivney biography—the book, co-written with the author Julie Fenster, that later inspired Dan Schachle. On the website of the Father Michael J. McGivney Guild for devotees, anyone can add to an ever-growing list of favors credited to him, from vanished tumors to newfound fertility. Each step of the process requires considerable legwork and expertise—including from specialized advocates in Rome—and therefore considerable funding. The Knights have not published a number, but Father Gabriel O’Donnell, who first helmed McGivney’s cause, said the direct costs have surely reached seven figures.

After word of Mikey’s birth ascended the chain of command, the task of investigating the case fell to a tribunal assembled by the Diocese of Nashville, with the medical expert Dr. Fred Callahan. In his slow Southern inflection, Callahan calls himself a “country neurologist,” although his solo practice occupies a small strip mall suite in Nashville proper. He was recruited by the bishop of Nashville, a patient and friend, to collect and summarize the medical data for officials and doctors in Rome. “I turned him down a couple times, but he kept on calling,” Callahan recalled, sitting across from me in his waiting room. “Why do you need a country neurologist for that? It’s neonatal medicine.”

Callahan, now 75, remembers only fragments of the investigation. One step that stuck: “They had guys come from Rome to swear us to secrecy.” He remembers as well the initial feedback on his draft report: “They told me that my conclusion suggested too much that I had an opinion. I said, ‘Well, I’m an American, I’m entitled to have an opinion.’” Upon my asking, he declined to tell me his opinion.

Church officials also had to check that the Schachles had prayed to McGivney and only McGivney. A family friend of theirs who was a seminarian in Rome had prayed with the Schachles during their 2015 trip; he got a call from an investigator inquiring about the targets of their prayers. Jesus and Mary, it turned out, were permissible exceptions.

On May 27, 2020, Pope Francis certified the miracle, allowing for McGivney to be beatified, or declared “blessed.” News articles and videos about Mikey’s previously private story proliferated online, in Catholic and secular outlets alike. In August, the Knights released a video that opens with Mikey, in overalls, on a chair at home. In a voiceover, Dan says, “God writes the best stories, and we didn’t realize what he was doing in our lives.”

God’s story quickly became the Knights’ story. The communications staff in Connecticut kicked into full gear to spread it, installing McGivney and the canonization campaign as central features of the organization’s public image. Victoria Verderame, then a Knights corporate

communications manager, told me the shift meant “making a concerted effort to vocalize that Father McGivney is—he is the mission of the Knights of Columbus.”

The celebrations climaxed in October 2020 at the Mass marking McGivney’s beatification. The Schachles stopped in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on their drive up to Connecticut, where they were quarantined for four days in the Omni New Haven Hotel. The main service occurred on Halloween at Hartford’s Cathedral of Saint Joseph, with limited attendance. Dan and a veiled Michelle, carrying Mikey, were interviewed live from the church plaza by a studio anchor on the Eternal Word Television Network.

The week before I left for Tennessee, Dan told me his family would not be available to see me. Only once a Knights flack arranged our encounter did I first meet six Schachles at a Cracker Barrel just off the highway. The restaurant was packed and loud at 8 a.m. as we sat down at a round table in the corner. Michelle brought an album of images and timelines reconstructing Mikey’s medical drama. Besides repeated interviews, the Schachles are sometimes treated as smalltime celebrities at a friend’s wedding or an out-of-town Mass. “It’s a nuisance, honestly, but it’s a cross that we’re willing to bear to help Christ give other people hope,” Dan said.

His discomfort with all the attention, and with my visit, ran deeper than the inconvenience. “My biggest struggle has been making sure that I am not leveraging the sacred, God’s actions, for my financial personal gain,” Dan said. “I don’t want the publicity. I want to go about doing my vocation of taking care of widows and orphans, and not say, ‘Buy insurance from me because God did this, and I’m great, and all that.’ I don’t want to go to hell because of this.”

In August 2022, the Knights’ 140th Supreme Convention—the first in-person one since the pandemic began, complete with exultation at the Supreme Court’s recent overruling of Roe v. Wade—took place in Nashville. “HOME OF MIKEY’S MIRACLE,” read a Warholesque poster. Supreme Knight Patrick Kelly saluted the Schachles in his main speech, as footage of Mikey at home played on big screens for the convention hall. Dan held up 7-year-old Mikey. “Thank you for saying ‘yes’ to life,” Kelly proclaimed.

At the Cracker Barrel, Dan explained his caution with a parable about a prideful donkey. “They hang the sacred images across the donkey’s back for the parade through town,” he said. “As the donkey comes by, everyone’s kneeling down and praising the images and stuff. And the donkey becomes too proud and won’t go into stable. He’s too good of a donkey, because everyone worships him, right? So, first of all, I’m just a jackass. Whatever’s happened to me is God, not me.”

As the whirlpool of of McGivney’s advance toward sainthood revolved around the Schachles, it would also engulf a New Haven landmark: the church where McGivney spent his seven years in the city. St. Mary’s Church stands on leafy Hillhouse Avenue, surrounded by Yale buildings. Pass by the

statue of McGivney to ascend the church steps, and, as one Catholic on campus put it, “you’re entering into a different world.” The floor is wood-tiled, the ceiling mostly sky-blue. Maroon columns rise like clumped-up red licorice.

The building was consecrated in 1874. When 25-year-old Michael McGivney arrived three years later, the church was gravely in debt. Eight years after that, the bishop handed the church to Dominican friars, members of a centuries-old religious order known for an intellectual style that meshed naturally with the Yale milieu. The Dominicans averted financial ruin at St. Mary’s and, beginning in 1907, used a grand house erected next door as their priory, a communal home.

More recently, the Knights of Columbus has picked up the tab for upgrades at the church. For its 1982 centennial, the organization installed a granite sarcophagus for McGivney’s corpse, which was exhumed from a Waterbury graveyard. “The Dominicans came in and saved this church,” Martin O’Connor, a New Haven deacon and St. Mary’s stalwart, said; the Knights, for their part, “have provided extravagantly for the church.” The two groups made for an unlikely symbiosis—between the old and the newer, the cerebral and the corporate. All the while, the Dominicans retained the St. Mary’s pulpit.

That is, until an ecclesiastical earthquake hit in October 2021: the archbishop of Hartford announced that New Haven’s eight Catholic churches—including a Hispanic one, a Polish-speaking one, and a historically Black one—would merge to form one parish with shared clergy. The official rationale was unremarkable, especially in pandemic-era New England: fewer priests spread thin across abundant churches

that had seen fuller days. But the move had an abrupt byproduct.

St. Mary’s, “due to its significance, its location,” would be “the mother church” in the hands of diocesan priests, said Father Ryan Lerner, who oversees the consolidated parish. After 135 years there, the Dominicans, it became clear, would have to go.

A Facebook post by the friars announcing their departure accumulated comments from devastated churchgoers: “Heartbreaking news. Blessed Michael McGivney pray for us.” “Executive decisions with hazy rationales are not only upsetting, they are also insulting.” One reaction came from farther afield. “So sorry to hear! To our St Mary’s family. Blessed McGivney, pray for St. Mary’s,” wrote Dan Schachle. The episode remains a sore subject at St. Mary’s, where regulars speak in adoring terms about how the Dominicans shaped their spirituality.

Adding to the unsavory flavor of what one parishioner likened to a “dirty real estate play” by the archdiocese, many suspect that McGivney’s beatification less than a year earlier—and his tomb’s heightened power to attract pilgrims— had piqued the archbishop’s interest in taking more direct control of the church. The signs of an ulterior motive stuck out to Eire. “This is so ancient. The bishops like to have the relics. They like to have a church that attracts pilgrims,” he said, adding that, among others who know church history, “We all laughed about it when it happened, and cried at the same time, because it’s just so typical.”

The archbishop, Leonard Blair, who stepped down in May, acknowledged that McGivney’s sarcophagus figured in his decision to remove the Dominicans from St. Mary’s. The archdiocese offered the Dominicans alternative posts, which the friars said they did not have enough time to consider before being kicked out. “We have to have a pastoral plan for the city that also includes the reality of, I hope, a future saint being buried right in the middle of it,” Blair told me over the phone. “And so this was not aimed at the Dominicans or anything. It’s just part of a larger thing.”

It will be a future the Dominicans helped usher in. They tended to McGivney’s tomb and have long held top religious positions at the Knights. One Dominican, O’Donnell, led the canonization effort’s initial phase while living in the St. Mary’s priory and still leads the McGivney Guild. “It’s easy to take a cynical view of it, but I would resist that,” O’Donnell, now 81, said of his fellow friars’ expulsion. Father John Paul Walker,

the last Dominican pastor of St. Mary’s, played a key part in honoring McGivney’s beatification the year before. “I guess you could say that there is some irony in the timing,” he allowed.

The St. Mary’s priory, as it’s still imprecisely known in the Dominicans’ absence, now houses the parish offices and several priests. The Dominicans’ exit was “not a good chapter in the history of this parish,” Deacon O’Connor, a former chief of the New Haven Fire Department, said as we sat in the building’s wood-paneled dining room. “The Dominicans changed my life,” he said. “Why would they leave, or be asked to leave, when you have a shortage of priests? So that still baffles me. They built this house.”

Clergymen, anticipating that a Saint McGivney will attract untold pilgrims, said the house may someday be converted into a visitor center with bathrooms and a gift shop.

As he looks out over hillhouse avenue, McGivney’s expression is hard to read. His lips seem to form a frown, yet his boyish cheeks crease around his nose and mouth as if on the cusp of a smile. His shimmery eyes, gazing to the right, suggest something like a distant pride. The official portrait— the chief visual embodiment of McGivney’s afterlife—hangs from the church’s gothic stone facade.

If St. Mary’s Church elevates the man’s face, the global headquarters of the Knights of Columbus—on the other, grayer side of downtown New Haven—further elevates his name. It’s the second-tallest building in town, a modern monument of concrete, brick, and glass with imposing cylindrical towers at its four corners. Emblazoned across three floors’ windows are the words “BLESSED MICHAEL McGIVNEY.”

A brutalist building down the block from the Knights’ tower, once home to a mix of local agencies and organizations, now houses the Blessed Michael McGivney Pilgrimage Center. In July 2023, the city’s consolidated parish was christened the Blessed Michael McGivney Parish. Every Sunday Mass in New Haven includes a prayer for McGivney’s canonization. In short, McGivney has never been more visible in his adopted hometown. “From a Catholic perspective,”

Michael McGivney Pilgrimage Center, 1 State St

O’Donnell wrote in a McGivney Guild newsletter last year, “New Haven, Conn., is now officially ‘McGivney City.’”

A few American-born men besides McGivney are blessed, too. Among them is Stanley Rother, an Oklahoman priest who was martyred during Guatemala’s civil war. It is difficult to know whose proponents will attain their final certified miracle first. According to McGivney’s great-grandnephew, a Bridgeport lawyer, the Vatican has received evidence about a Connecticut woman who recovered from a medical emergency with McGivney’s aid. (The Knights did not respond to a request for corroboration or more details.)

Depending on whom you ask, McGivney stands for the priesthood (his example redeems a vocation plagued by scandal), for baseball (he loved to play), for civic associations (the Knights has defied their decline), for nuclear families (he supported them through tough times), or for American Catholicism’s vitality (his homegrown holiness could be its sign and seed). As the Knights’ avatar, he represents, above all, traditional Catholic manhood, fatherhood, and brotherhood, at a time when the Knights see all three under threat. “If more people knew about the virtue and the aims of Father McGivney, that could change our whole culture,” Dan Schachle said.

Two years after founding the Knights at St. Mary’s, McGivney was transferred from the church to one in Thomaston, Connecticut. He died six years after that, at age 38. If he is canonized, the Knights will no doubt savor a spectacle in Rome. Meanwhile, in Dickson’s tight-knit Catholic community, the Schachle miracle’s certification garnered little attention in 2020, when parishioners were preoccupied with frustration about COVID-19 restrictions. In May, St. Christopher’s priest told me the miracle was “old news.”

Not so for the Knights of Columbus: A July 2023 promotional video titled “We are the Knights of Columbus” features Dan discussing “Father McGivney’s mission” while a clip of Mikey with two of his siblings rolls. And not so for New Haven, either. The annual feast day dedicated to McGivney comes on August 13, between his birthday of August 12 and his death date of August 14. This year, it featured a special Holy Hour and Mass at St. Mary’s. For almost the first time since McGivney’s stint there, regular diocesan

priests are pastoring at St. Mary’s, hoping their forerunner’s rise will invigorate church life. One of the priests has brushed-back brown hair and a youthful face that make him unmistakably resemble McGivney.

During a Sunday Mass in April, in the back left corner of the church, one woman sojourned at length by McGivney’s sarcophagus. Branford resident Victoria Pallotto started frequenting St. Mary’s shortly before the pandemic, drawn in by the Dominicans. Although their departure rankled her, Pallotto has no trouble juggling devotion and disapproval. “We’re all humans. We all have faults and weaknesses and greeds,” said Pallotto, who previously consulted as a headhunter for the Knights.

McGivney has become more than a human: a myth, and perhaps many things more. To Pallotto, he is part of a heavenly world that coexists with ours. The wrinkle where the two worlds meet—where divinity becomes tangible— is a matter of Catholic doctrine: the unity of body and soul. Maybe McGivney’s presence can help others, like Pallotto, bridge the gap.

Long after he died, his inheritors have invested themselves in him, time and again. From Tennessee to Connecticut, and far beyond, they have made his vision their own, putting faith in a future he promises from above. Their investments are multiplying, past living memory of the principal. The greatest reward has yet to come. Call it spiritual insurance. The premiums have been paid.

Ethan Wolin is a sophomore in Silliman College.

This project was supported by a Howard Topol Travel Fellowship from Silliman College and by The New Journal’s Edward B. Bennett III Memorial Fellowship.

By Tigerlily Hopson

“Here comes Dick, he’s wearing a skirt, here comes Jane, you know she’s sporting a chain.”

– “Androgynous” by The Replacements

IBecame a British crew man. Five foot two, a woman, American, and I’d never rowed in my life. I swaggered about campus in a gold chain, spoke in a deep voice, affixed a “Yale Crew” decal to my computer case, and wielded British epithets. My friends expressed concern about this sudden transformation. “When you start wanting to be a misogynistic man, there is something to unpack,” one of them told me. I had gone from an ardent feminist to loudly talking about the girls I wanted to “fook.”

My sophomore fall, the entire heavyweight crew team seemed to be in the science class for non-science majors called Planets and Stars. I stared at the mass of muscly men, jostling and play fighting, their long legs splayed, their snickers loud. They were all tall, all blond, all British or at the very least Australian, and all sporting chains. They looked untroubled. “Did you do the homework?” “Fook no, mate.”

I was an anxious, straight, cisgender girl who cared too much. I cared too much about school and the state of the world and my family and what people thought of me. I cared until it hurt inside. Singing lullabies and making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with the crust cut off was how I spent my early teenage years. I was selfless for my little brother, like how my mom was selfless for

me. Was this destiny for women? To care while the men walked off carefree?

In Planets and Stars, I also stared at the girls. In particular, a girl with a messy mullet who smoked cigarettes and made my cheeks tint pink. A friend told me to listen to we fell in love in october by girl in red. Fall leaves crunched under my boots. Smoking cigarettes on the roof, you look so pretty and I love this view. I tried to complete problem sets, calculating the distance to stars. Looking at the stars, admiring from afar, my girl, my girl, my girl.

Transfixed by crew men, I dressed up as one for Halloween. Backwards baseball cap, athletic shorts, and Kyle’s gold chain. I yelled the whole night in a British man’s voice. When I sat, I manspread. When I walked, I swaggered. When I danced, I thrashed. I didn’t care how men saw me, euphoric in this new embodiment.

I never took the chain off. I permanently spoke an octave lower. I shelved my bell hooks books. I talked about the girls I liked as if I was a crew man. “Yuh, she’s so hot, mate.”

It was a bit—except it wasn’t. Did I want to be a man? Did I feel like I had to be a man to be with women? “Lesbians are not women,” my roommate told me when I came to her, distressed. She was quoting Monique Wittig. Gender is oppositional—the identity of women is relational to men, and vice versa. As I desired women, and wished to be desired by women, I no longer perceived the male gaze. I flailed about in my womanness, unmoored. What I had been told all my life made me unattractive to men—being

assertive, being unfeminine—made me attractive to women. My face without makeup was not ugly, but handsome.

It was my junior year, and I had settled into my identity—I dropped the British accent and the “Yale Crew” decal from my computer. I fell in love with a best friend. This was a friend I shared everything with. We held hands. We gazed at the stars. We read feminist theory together in the library stacks. I told her I wanted to raise children with her in a commune. She was straight. Until she started questioning her sexuality. Then, she started dating a man.

She took me to a bench in the concrete courtyard of her apartment complex. “This is where I asked him to be my boyfriend,” she said. “I’ll show you how it happened. You pretend to be him. I’ll be myself.” I sat next to her, legs spread slightly, so my knee touched hers. How would I sit if I were him? She told me how much she liked me. Her features blended with the dark. “Then we kissed.” Facing each other, our black eyes glimmering, we stared in silence. I want to be her boyfriend. It came suddenly and strongly. I want to be her boyfriend.

I wore ties and waistcoats. My friend said I looked good in them. My roommate found me sobbing on my bed. “I wish I had a dick,” I choked out. It was a biting wish that gnawed within me, a desire that throbbed between my legs. “Then maybe she’d be with me.” I told my friend I liked her, and sent flowers to her door. She stayed with her boyfriend— leaving me with myself.

tures out of rocks, drawing with cray ons, running around in the mud. I loved princesses, and I loved superheroes. My hair was wispy and shorter than my chin. There’s another, a few years later, where I’m wearing a dress, my legs crossed, my hands clasped. I’m sitting below my boy cousin, who’s raised above me. My eyes look blank. I remember thinking I had to sit pretty. In my dorm room, I struggled in solitude. My body was ill with anxiety and my mind clouded by depression. I was peeling away old trauma, unlearning self-sacrifice and impossible standards

the floor. When she is finished, we both look at me in the mirror. My face relaxes into a floppy grin.

Little things give me joy. A pack of Hanes boxers. White undershirts for teenage boys. Old Spice body wash with an ominous octopus on the front.

I’m wearing a necktie in a bar, swigging a shot of whiskey and a Budweiser. A person comes up to me, and I play with her hair. They giggle. He tells me I’m pretty. She uses all pronouns—he, she, they—but tonight, she says, she feels girly. My body presses on hers as we lean

on the pinball machines. “What are your pronouns?” she asks. “I don’t know,” I everything in between. And yet, it also sheds she and he completely. It’s a pronoun of the self—beyond petty, old things like grammar books. I realize, I don’t have to be a crew man. I can just be myself. When I sit, I manspread. When I walk, I swagger. When I dance, I thrash. ∎

Tigerlily Hopson is a senior in Berkeley College.

Burgeoning biotech development has residents wondering: can the city avoid the mistakes of past revitalization efforts?

By Tobias Liu

At 100 and 101 College Street, two opposite towers rise into New Haven’s skyline. Glimmering tinted windows conceal 1,038,000 square feet of labs and research space—a hub for the city’s burgeoning biotechnology sector. It wasn’t always like this.

Seven decades ago, former New Haven Mayor Richard Lee described this area, for-

transform the Oak Street Connector from a limited access highway into an “urban boulevard” with sidewalks and businesses. The goal of the DCP was to reconnect the two parts of downtown that the highway had separated for 60 years. The grant was a significant contribution for a city with a budget of around $475 million at the time.

DeStefano assembled a team of professionals and city administrators to brainstorm ideas for redeveloping the highway to create long-term economic value. The center of that redevelopment, they decided, would be the budding biotech industry. Fueled largely by innovation from Yale researchers, biotech leverages biological research to create new

merly the Oak Street neighborhood and part of the broader Hill neighborhood, as a “hard core of cancer which had to be removed.” To Lee, the neighborhood’s poverty was a disease that could metastasize and infect other parts of the city. He acted swiftly to contain it: in 1959, Oak Street became the first victim of New Haven’s federally funded urban renewal plan, which promised to bring an old, industrial city into a new economic era.

The Oak Street Connector was born. A limited access expressway designed for high-speed traffic, it aimed to extend Route 34 from Interstate 95 through New Haven, connecting the suburbs to the city. Lee hoped this plan would result in long-sought economic development. But by the 1970s, funding had dried up, and by the 1990s, construction to finish Route 34 was abandoned.

Five thousand demolished living units, 350 closed businesses, twenty-three thousand displaced people, and a milelong “Expressway to Nowhere” stood testament to Lee’s first-line therapy. His supposed cure for “cancer” had severed the Hill neighborhood from downtown New Haven, accelerating the Hill’s decline.

Five decades later, the city again set its sights on Oak Street, this time under Mayor John DeStefano Jr. In 2010, the City won a $16 million federal grant for the Downtown Crossing Project. It would

medical treatments and technologies— breakthroughs that the city hoped would erupt here in New Haven.

Amid the City’s efforts to fix Lee’s urban renewal “cure for cancer,” the literal fight against human cancer and disease has become remarkably significant.

“The synergy between the growth of the [biotech] industry and the desire to remove the highway came together at just the right time,” said Michael Piscitelli, New Haven’s current Economic Development Administrator.

The city and Yale envision an economic renewal centered around biotech. But New Haven and Yale have a history of letting big-picture economic development blot out residents’ needs, as the failures of their 1960s urban renewal effort demonstrate.

The question of who will benefit from the city’s investment in biotech remains

fraught. Jobs in biotech are often inaccessible to people without advanced degrees. And as expensive real estate for these firms reshapes New Haven’s skyline, some residents are left wondering if the city has pushed their need for affordable housing to the side.

In 2013, after years of planning, DeStefano initiated the demolition of the 54-year-old Oak Street Connector. “What was once a symbol of lost opportunity will again become a thriving part of our community,” he said at the time.

The question remains: as New Haven expands into a new era of urban development—largely focused on bolstering biotech—will the city repeat past mistakes of ignoring residents’ needs?

New Haven’s recent surge in biotech traces back to 1992, when Alexion Pharmaceuticals, founded by Yale professor Leonard Bell, became the city’s first major success in the industry. In 2007, the company launched a blockbuster immunosuppressive drug, Soliris. Fourteen years later, Alexion was acquired by AstraZeneca. The company now occupies 100 and 101 College Street.

“[Alexion] set the standard for the ability of our community to mature a biotech company,” Piscitelli said.

When DeStefano first stepped into office in 1994, he began to develop a partnership with then-Yale president Richard Levin, turning to the biotech industry as a potential remedy for the city’s declining economy. Ideally, the partnership would be mutually beneficial: the University would translate its research into Yalelicensed technologies, while New Haven’s economy would benefit from housing a growing, lucrative industry.

This new focus on technology transfer was formalized in 1995, when Yale tripled the budget of the Office of Cooperative Research—an entity created to translate research from Yale into products—and hired a former Pfizer executive to serve as its director. The OCR began to work closely with faculty whose research had potential commercial value to find investors. By 2000, 13 biotechnology companies had sprung up in New Haven.

The investment in biotechnology began to physically change the city’s urban landscape. Yale hired developer Carter Winstanley to create private sector lab

space for companies near the university. In 2000, Winstanley developed a nine-story biomedical research building at 300 George Street. By 2005, the space was fully leased to Yale, Yale New Haven Hospital, and a variety of biotechnology companies.

Through the recession of the late 2000s, Yale and New Haven’s new biotech machine continued to churn out new companies as the university helped its researchers monetize their work by investing in them and connecting them with venture capitalists. In 2009 alone, Yale churned out 5 new startups, and by 2010, the number of biotech companies in New Haven rose to around fifty. Developers raced to keep up with demand for laboratory space, and office occupancy rates rose. By then, Winstanley owned over one million square feet of commercial space between projects at Science Park and 300 George Street—but this still wasn’t enough space to support the rapid pace of new lab-space-dependent biotech research flying out from Yale.

“The pattern of history is always on our mind,” Piscitelli said. “The city paid a heavy price for urban renewal. We want to make sure we learned from that experience, that new development speaks to the future.”

still, the irony of the city’s plan— fixing one urban renewal failure with another—isn’t lost on New Haven residents, as the comments sections of New Haven Independent articles about the Downtown Crossing Project and the

city’s investment in biotech suggest.

“The city should have a plan in place for a developer to build a 40-story apartment building on the future site that would be across from 101 College…where people can mostly live, but also work and play,” writes commenter @_quinnchionn_.

“New Haven has spent millions on in the past decade, correcting the work by the cities ‘Best and the Brightest’ urban designers of yore,” writes @George Polk.

“New Haven is two cities, and I fear the growth of the industry will exacerbate the divide between them. I trust that most of the folks working in biotech are fine individuals. But I suspect few understand what it is like to live paycheck to paycheck (I don’t.) And they will be able to afford the rents in the new developments. Few New Haveners can,” writes @Kevin McCarthy.

Anstress Farwell, president of the New Haven Urban Design League, an independent nonprofit voice on planning and development issues, is also wary. When the plans for the Downtown Crossing Project came out in 2012, Farwell and the New Haven Urban Design League released a thirty-page report on its flaws, arguing that the plan does not actually serve its purpose of connecting the Hill to downtown New Haven. Further, Farwell worries that the plan prioritizes cars over pedestrians. Farwell told me that some of the designs in the final plan had changed from the original vision that won the federal grant—changes, she said, that reflected the city’s tendency to align with Winstanley’s interests.

“[Winstanley] is a facility planner, not

an urbanist,” Farwell said. “He’s focused on operations, not on infrastructure and creating systems that need to be at certain standards.” She worries that Winstanley’s emphasis on parking space over sidewalks will result in “dead economic space,” as a parking garage employs hundreds less than an inhabited business and would pay less in taxes. While such parking space would accommodate suburban commuters and make new development more immediately profitable, Farwell argues that it would do little for the Downtown Crossing’s goal of reconnecting Oak Street.

Farwell showed me two maps that hung in her office: one of off-street parking in New Haven in 1951 and another of parking in 2008. The difference is stark: on the second map, the red spots indicating parking take up almost half of the page.

Over email, Winstanley wrote that he agreed with the goal of minimizing parking, saying that 101 College Street. used a parking garage shared by several different buildings, and that the building had 86 percent less onsite parking than 100 College Street. “While not perfect, it seems like a significant step in the right direction,” Winstanley wrote.

Keeping a parking garage out of 101 College Street made room for a public plaza, allowing people from the neighborhood to “walk right out into the space,” Piscitelli said. It aligned with the city’s goal to create what he called a “more vibrant street life.”

Flawed or not, the Downtown Crossing Project and the construction of the College Street towers have likely solidified what city historian Michael Morand described as New Haven’s new “eds and meds” economy for the future. While Morand is skeptical that a biotech surge will match the employment levels of New Haven’s old manufacturing giants such as the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, he is optimistic that the industry could provide an important base for the city’s economic development.

“The economy used to rely on manufacturing guns and weapons of war,” Morand said. “The new focus is on human health. A good transition!”

employment in New Haven’s old weapons manufacturing industry generally did not require an advanced education, allowing all, regardless of education

level or origin, to access jobs in the 19th and early 20th century. Meanwhile, 90 percent of biotech jobs require at least a bachelor’s degree, according to Peter Dimoulas, grant program administrator for Southern Connecticut State University.

“That means that for the growth to benefit residents, there needs to be a strong commitment to investment in education and job training,” Morand said.

In response, the city has created several initiatives aimed at preparing New Haven Public School students for careers in biotech.

The first of these initiatives was BioPath, a nonprofit partnership between the city and SCSU. In 2015, the city and the university signed a memorandum of understanding to support career advancement in the biosciences.

BioPath has developed events such as the New Haven Science Fair and other programs to help teachers understand what a career in biotech looks like and incorporate it into their lesson plans. Funding for BioPath has come from industry partners like Alexion. The goal is to create pipelines for students from New Haven Public Schools to jobs in biotech.

“We need to make sure that we’re not selling them a pipe dream,” Dimoulas said.

During 101 College Street’s development, Winstanley decided to place a classroom in the center of the building, which has become an integral part of BioPath’s BioCity program. The program selects a cohort of high school juniors from four New Haven public schools for a biotech career training series.

“The program’s goal is to get real life exposure to what science is really like,” said Robert McCain, science supervisor for New Haven Public Schools. “Hopefully [students] go into biosciences as their major, and give back to New Haven by getting a job here, because there’s so many bioscience openings.”

McCain hopes to expand the program, but its grant funding—$1.5 million from the American Rescue Plan and $1.5 million from the Department of Education— will run out in three years. He’s looking for different ways to find the money needed to continue the program, but he knows it will be a challenge.

“When we started researching, we were trying to model ourselves after someone who’d already done this, but we couldn’t find any places that have done anything like this in a large urban city,” he said.

Since 2021, BioPath has secured over 150 job and internship placements. BioCity hopes to reach 75 students over the next three years. BioLaunch, another similar program headed by Craig Crews, a Yale professor and the founder of biotech company Arvinas, has cohorts of 30 individuals each academic year. The numbers are not huge, but they’re a “proof of concept” that needs to be established; then, hopefully, they will scale up, Piscitelli told me.

Katherine Perez, an alumni of Wilbur Cross High School and SCSU, told me how SCSU’s guidance in helping place her in a biotech internship with Medtronic “opened [her] eyes to see what’s out there.”

After completing a master’s degree in physics, she returned to Wilbur Cross, where she had just finished her fifth year teaching an early college credit class to help high school students get a head start on their careers.

Melanie Burgos, who grew up in New Haven and also attended SCSU, told me that her BioPath mentorship helped place her in an internship and inspired her to found the “Latinx in STEM ” club at the university.

“The truth is, you need the experience, the research, all these things to succeed all while managing college. It’s so difficult, and [Dimoulas’ team] allowed us to find those opportunities. In my wildest dreams, I never would have thought I would have the opportunity to actually do research in a lab,” Burgos said.

She served as a panelist for the first two years of BioPath’s Connecting Students and Professionals of Color events—events that she said have allowed her to connect with industry

professionals like Alexion, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer.

As the city works with Yale and the biotech industry to mend their historical failures and move past their old industrial economy, they will need to replicate success stories like Perez and Burgos’. A successful new biotech economy will bring money back into the city, but could also raise the rent for those living in New Haven when affordable housing is already scarce.

The city has plans to continue housing development in places such as Pierpoint and Church Street South and insists that their focus on developing on parking lots and vacant land reduces the displacement of residents from their homes. But renters still confront rising rents, and locals may find themselves excluded from the biotech job market in the city’s search for a cure.

“A rising tide lifts all ships.” said Dimoulas. “But the question that remains is: are the opportunities in New Haven also for New Haven? Can the average student from New Haven, Hamden, West Haven—can they gain meaningful employment among these companies?”

On most days, people in suits stream in and out of the College Street buildings. Dimoulas wonders if, in a decade, students from New Haven public schools—perhaps from the Hill—may find themselves among them. ∎

Tobias Liu is a junior in Trumbull College.

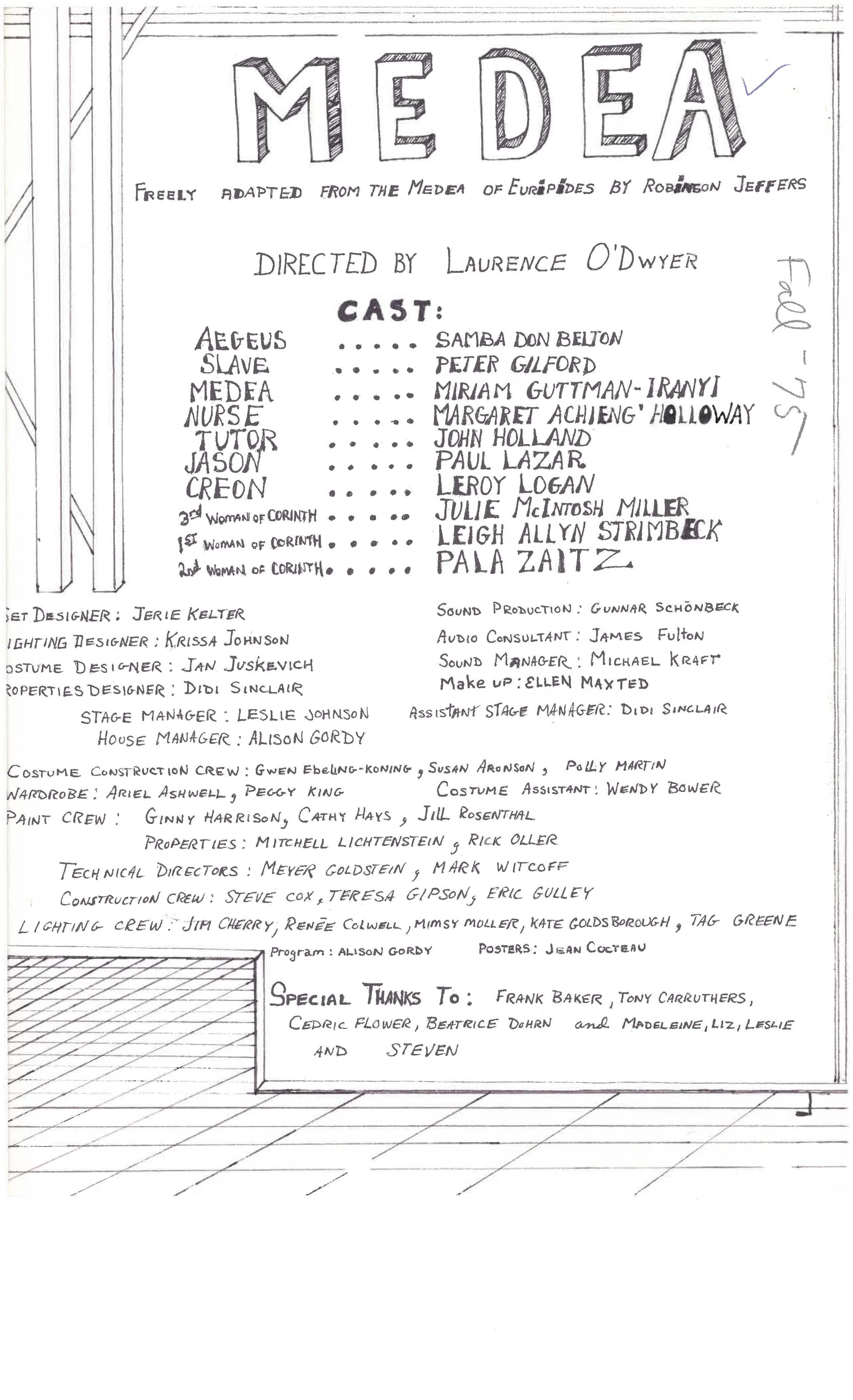

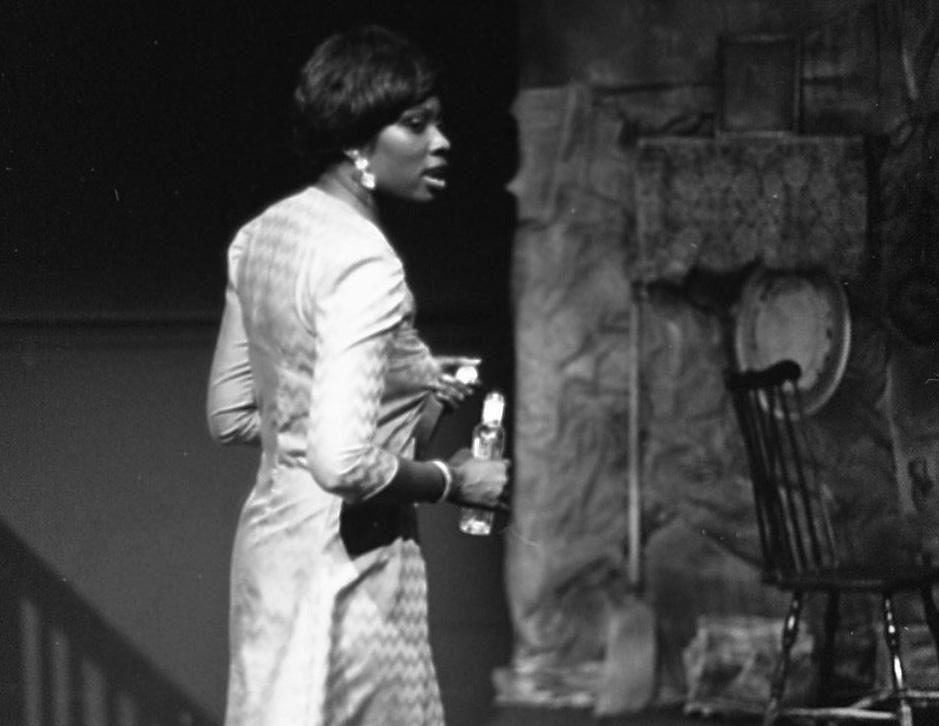

For decades, Margaret Holloway performed Shakespeare on the corner of York Street in exchange for money. Behind the mythos of “The Shakespeare Lady” was a budding actress failed by a series of places and people—including at the Yale School of Drama.

By Chloe Budakian

*This article contains references to sexual assault.

:

As Holloway became more comfortable with her cohort, her teachers grew intrigued, if not charmed by her. “From Holloway’s writing, one gets a sense of explosion, spewing forth, release––as though she had never expressed herself out loud on paper before,” wrote one English teacher. The teacher described Holloway’s intuitions about literature as “unusually mature,” observing that students would defer to Holloway before contributing their own responses, as if she were their spokesman.

Though she was shrewd, she was not without humor. In Holloway’s progress log, a tutor recounts a story Holloway told about a white Albany High classmate who called her a slur and demanded answers to a math assignment: “Holloway gave her all the wrong answers and is enjoying the fact that the girl is still taking geometry.”

At the end of the ABC program, its director, Dr. Frank Morral, recommended Holloway to Northfield Mount Hermon, a boarding school in

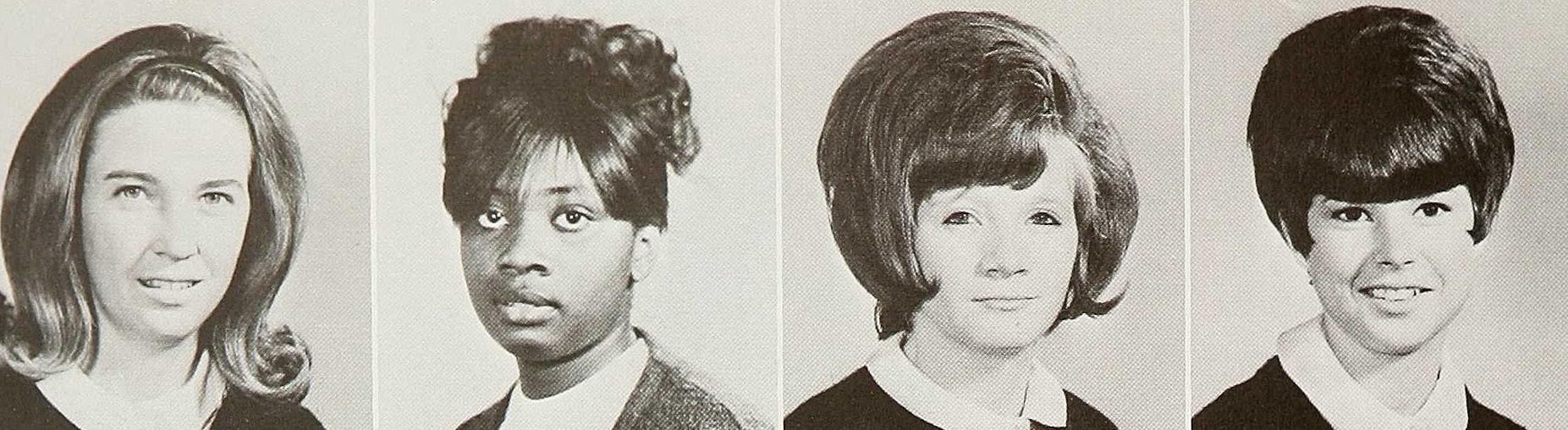

The Northfield Class of 1970 had 198 students. Faces from the yearbook suggest that nine of them were Black.

“I am the only black student in my dorm and it can get quite depressing at times,” Holloway wrote in a letter to Morral. “It isn’t a very good feeling knowing my background when all I hear is talk about ski trips; $500.00 coats, (just for classes), vacations in London, etc.” One of Holloway’s few Black classmates, Cornell Hills, remembered a similar isolation. “You couldn’t be Black at Northfield Mount Hermon without hanging out with somebody [from the African American society] otherwise you would’ve gone insane. Like you

Even among other Black students, Holloway didn’t fit in completely. Hills remembers her as serious, intense, and even intimidating. “Back then if you wore an afro, you’re immediately identified as being somewhat militant,” Hills said.

Holloway had dark skin, and Hill remembers that she was perceived as the most “African” woman at Northfield. Hills remembers Holloway had few friends, and few romantic prospects. “She might have been seen as being too Black,” he said.

In varying degrees, Holloway lived on the outskirts of ABC, Northfield Mount Hermon, and the AFRO-AM Society.

Despite her alienation, Holloway found autonomy at Northfield. “A person does not have to live up to any reputation, there is almost no outside interference, and your parents cannot keep there [sic] apron strings choked around your neck,” she wrote in a letter to Morral.

After graduating from Northfield, Holloway attended Carleton College for a year as a comparative religion major. There, she acted in student productions for the first time and fell in love with theater. After her freshman year, Holloway transferred to Bennington College in southern Vermont, where she enrolled as a drama major.

***

It was at bennington, a small, private liberal arts college, that Holloway’s best friend and dormmate Laura Spector first heard the word “trust fund.”

Their friendship was not an obvious match. “Looking at us, you would never put two and two together,” Spector said. Spector, who is white, was a tiny dance major (“5’1 and a half,” she said, emphasizing the “half”). And there was Holloway: outspoken, “stunning, six feet, gorgeous” with long, slender limbs, piercing eyes, and an afro. Spector remembers her laugh well. Her shoulders would shrug, she’d let out big, whooping giggles, and her head would bob as she covered her mouth.

Spector and Holloway formed a friend group with two other students, including Philemona Williamson, now a prolific visual artist. “It was a family, the best family I ever had,” Spector reminisced. “I think for Margaret, too, it was like a really bonded family.”

At Bennington, privilege was assumed, not displayed. Students were artists: they lived in the woods with personal studios. Ski coats were replaced with big overalls and flowing skirts. When commitment to high art was the standard, students were regarded more for their talent than their family history. And Holloway had talent in spades.

The qualities that had isolated Holloway—her charisma, her physical presence, her wit, her laughter—bonded her to her new cohort. According to three classmates, Holloway was a Bennington star. “They viewed her with absolute respect. Absolute awe. She was a queen,” Spector said.

Every year, Bennington students took a non-resident term to pursue their art in the “real world,” which often brought them to a second bubble: New York City. But Holloway, who lacked the same familial wealth as her peers, remained at Bennington.

In fact, Holloway was estranged from her parents entirely. Of the thirteen people I spoke to— close friends, artistic collaborators, acquaintances who knew her only as the Shakespeare Lady—all mentioned that she talked openly about parental abuse. Some recounted sharp tensions with her father, and many remember Holloway saying she had been abused by her mother.

At Bennington, Holloway had confided to Spector that a family member had raped her as a child. She was abused. She wanted no contact. To Spector’s knowledge, Holloway never returned to Albany after she left for Northfield. Holloway stayed at Bennington during holidays; for Thanksgiving one year, she went to Spector’s house. During the summers, she took on odd jobs at Northfield, ABC, and Bennington.

Bennington was her family. The institutions that brought her to the North were her home. It was her Southern upbringing, however, that informed her first original play.

On a sparsely decorated stage, Holloway stood alone, improvising much of the material and in total control. Holloway became Jeanette, a Black servant to a Southern white woman. Jeanette lamented the death of her first lover, who was lynched after “looking wrong” at a white woman. Jeanette gossipped with her friends. She went to large parties. She attended a Southern Baptist church service.

Repeatedly, Jeanette’s thoughts flash back to an

early childhood memory when her mother, bathing her, told her what to expect from her life. In a parallel vignette, a Haitian voodoo dancer and drummer cast bones that prophesied the events of Jeanette’s life.

“The real strength of the play is that Ms. Holloway does most of it by herself,” read a review in the Bennington Banner. “She could just decide: this is it,” Alex Brown, a Bennington classmate, told me. “They’re listening. I’m ahead of them. Most actors are waiting to see if the audience is there.”

It’s hard not to read Holloway’s life into the play. Her life, like Jeanette’s, bore the weight of circumstance––of poverty, of injustice, of life as a poor Black woman in the South. Circumstance, and the limitations it imposed, became a kind of predestination for Jeanette, committing her to a life of poverty and discrimination.

Not so for Holloway. No bones could have foretold that she would become a standout in one of the country’s most elite drama schools––nor could they have foretold what happened afterward.

In December 2004, the new york times published an article about Holloway. It was headlined “A Resurgent Downtown Wearies of a Street Poet’s Antic Disposition.”

“Margaret Holloway chose Shakespeare [Hamlet, Act I, Scene II], of course, for her first performance after serving 53 days in jail for failing to appear in court on charges of disorderly conduct, breaching the peace and other urban theatrics,” wrote reporter William Yardley.

In the article, Yardley quotes a bartender at a local pub. “She just badgers you,” the bartender says. “My buddy paid her $50 once to be left alone for a year.”

According to the Times article, Holloway was set to appear in court to discuss her use of crack cocaine

and schizophrenia medication. “But perhaps most important,” the article read, “she must convince the judge that she has stopped offending merchants and passers-by on the gentrifying blocks east of the historic New Haven town green, where expensive new condominiums are on sale just steps from her squalid third-floor room.”

In the public consciousness, Holloway had all but lost her name. To most, she was “The Shakespeare Lady”—a figure bearing the mythology that she was once a student at Yale. Yet, little is known about what happened when Holloway attended the School of Drama. When Holloway’s career was finally within grasp, circumstance plummeted her life in the opposite direction.

When describing the culture at the Yale School of Drama, Holloway’s classmate and one of the School’s first female directing students, repeatedly used the phrase “psychological torture.”

“It was like an Agatha Christie novel,” Gordon said. The directing students were immediately made aware that only some from their original class would make it through the School of Drama. “You look at your colleagues and go, ‘who’s gonna die?’”

When Holloway was a student, the School of Drama operated on a probationary basis. For their first two years, no student’s spot was secure. Each year, faculty expelled students who did not perform up to par.

Such was the philosophy of Dean Robert Brustein, founder of the renowned Yale Repertory Theatre. Brustein—who passed away in 2020—was a bold, relentlessly authoritative giant in the American theater scene.

Brustein came to Yale with a pedagogical vision of “professionalizing” the school. Students Brustein championed would get the opportunity to work with his professional actors at the Yale Repertory Theatre.

It seemed to Gordon that the pressures of the School of Drama only strengthened Holloway’s dedication to her training. Gordon remembered her as “intense,” “fearless,” and “regal”—impressively in command of her material. “I think a lot of people in my class were afraid of her. I was a little afraid of her too.”

Brustein had “a few woman favorites,” Gordon told me. Holloway was not one of them. Gordon remembered how Brustein often overlooked Holloway, reserving recognition and opportunity for his favorite students—one of whom was Meryl Streep. “I would say Holloway was equally a star in the making but had to fight harder for everything she got,” Gordon said.

Brustein had controversial opinions about race: he publicly criticized August Wilson, a Black playwright who advocated for theater about the Black experience, accusing Wilson of promoting separatism.

In 1972, a group of eight Black School of Drama students staged a protest in front of the Yale Repertory Theatre, holding signs that read “We Do Exist” and “King Brustein is insensitive to black artists.” According to Yale Daily News coverage, the protestors expressed frustration

over “stereotypical casting of blacks as marginal characters, and hostile attitudes expressed by the faculty at attempts to present elements of the black experience.”

Brustein chose not to comment for the YDN article. In many ways, the structure of the School of Drama spoke for itself.

“This is the way he operates, on students’ fear of losing their Yale degree,” said one student in a 1975 YDN article. “He confuses loyalty with competence,” the student continued. “His attitude is, ‘If you don’t like it, get out. And if you’ve come this far, what can you do?’”

In the spring of 1975, Robert Lewis, the head of the acting department, cast Holloway in a class production of “Death Comes to Us All, Mary Agnes” by Christopher Durang, a School of Drama alum and Brustein favorite. Lewis cast Holloway as the maid, a sexual role that required Holloway to take off her shirt and seduce two male characters. Later in life, Holloway said she felt she was cast as the maid because of her race.

On March 27, 1975, Brustein received a letter from Holloway. In it, Holloway described how she had approached Lewis with concerns about the “physical nature” of the play, but he had dismissed her. That night, at rehearsal, Holloway says Lewis mocked her in front of other cast members by implying that she was too fragile to even hear sexually explicit language. “Although I didn’t show it, I was absolutely shattered,” Holloway wrote. “I could not believe that a man I had loved and respected and hung on to his every word for all these months had repeatedly insulted my personhood that way.”

Holloway concluded the letter by expressing that she had “no place to turn.” “I considered begging out of the part, but after Bobby’s response I feared my acting classes would be in jeopardy,” she wrote. “I could not afford that. I cannot express to you the loss I feel.”

On the official Yale School of Drama program, Dennie Gordon plays “Elizabeth,” the maid. In the published play, her name is “Margaret.”

Holloway had enough.

That same year, Holloway left Yale and went back to a happier time in her life— Bennington—where she pursued a master’s in theater. There, Holloway wrote and directed “Facials,” her thesis play. According to a review in the Bennington alumni magazine, the play examines the life of two women—a prostitute and a journalist—as they “wrestle with authority figures and sexual domination.” “My image was that both women were wallowing in shit,” Holloway said.