4 minute read

Preserving Fairfield’s Sun Tavern with the Freemasons

by James W. D’Acosta, 32˚, Valley of Bridgeport

On the moonlit evening of November 15, 2012, Freemasons returned to Sun Tavern for the first time since 1809, thanks to Fairfield Museum’s preservation efforts. In the process, the Museum awakened the Tavern’s role in the town’s daily life. But how did saving a landmark end up nurturing an ancient society?

Friendship is at the heart of this Masonic adventure. Passion for Fairfield’s history drew Chris S. J. Jennings and Walter Matis into each other’s circle of acquaintances. Jennings, the Worshipful Master of St. John’s No. 3, knew of its early meetings at the Tavern and aspired to orchestrate a return. Matis, Fairfield Museum’s Program and Volunteer Coordinator, was involved in raising funds for vital lead paint abatement and encapsulation.

Sun Tavern’s claims to the Museum’s scarce resources are manifest. Built in 1780, it stands on its original foundations. Situated along Old Post Road in the southern corner of the town green and adjacent to town hall, it is a witness to American history since Independence. Travel along the New York City to Boston corridor still flows within sight of its windows.

That George Washington slept at Sun Tavern on the night of October 16, 1789, is the conclusion of Thomas J. Farnham in Fairfield: The Biography of a Community, 1639-1989. Additionally, John Adams wrote of being “in good health and Spirits” while staying there, and later correspondence finds Abigail attesting to the same “upon a visit at Fairfield.”

According to Matis, the Tavern is called “Penfield’s” and sometimes listed as “S. Penfield’s” in early documents. The first references to the name “Sun Tavern” appear in the late nineteenth century and may have been started by Robert Manuel Smith who lived in the structure from 1885 until the early 20th century.

Samuel Penfield bought 1.5 acres with “buildings thereon standing” from Thomas and Hannah Gibbs in 1761 and began operating a tavern on the property sometime before the revolution which fell victim to “Tryon’s Raid” on July 7, 1779. During this cataclysmic event, British troops also burned the courthouse, church, and most of the homes near the green. Sun Tavern rose from these ashes.

Lodge records reveal that Jonathan Bulkeley’s competing tavern, known to have been General William Tryon’s headquarters during the raid, was many times its meeting place during Bulkeley’s unusually long tenure as Worshipful Master from 1771 to 1788. Masonic lodges often met at taverns.

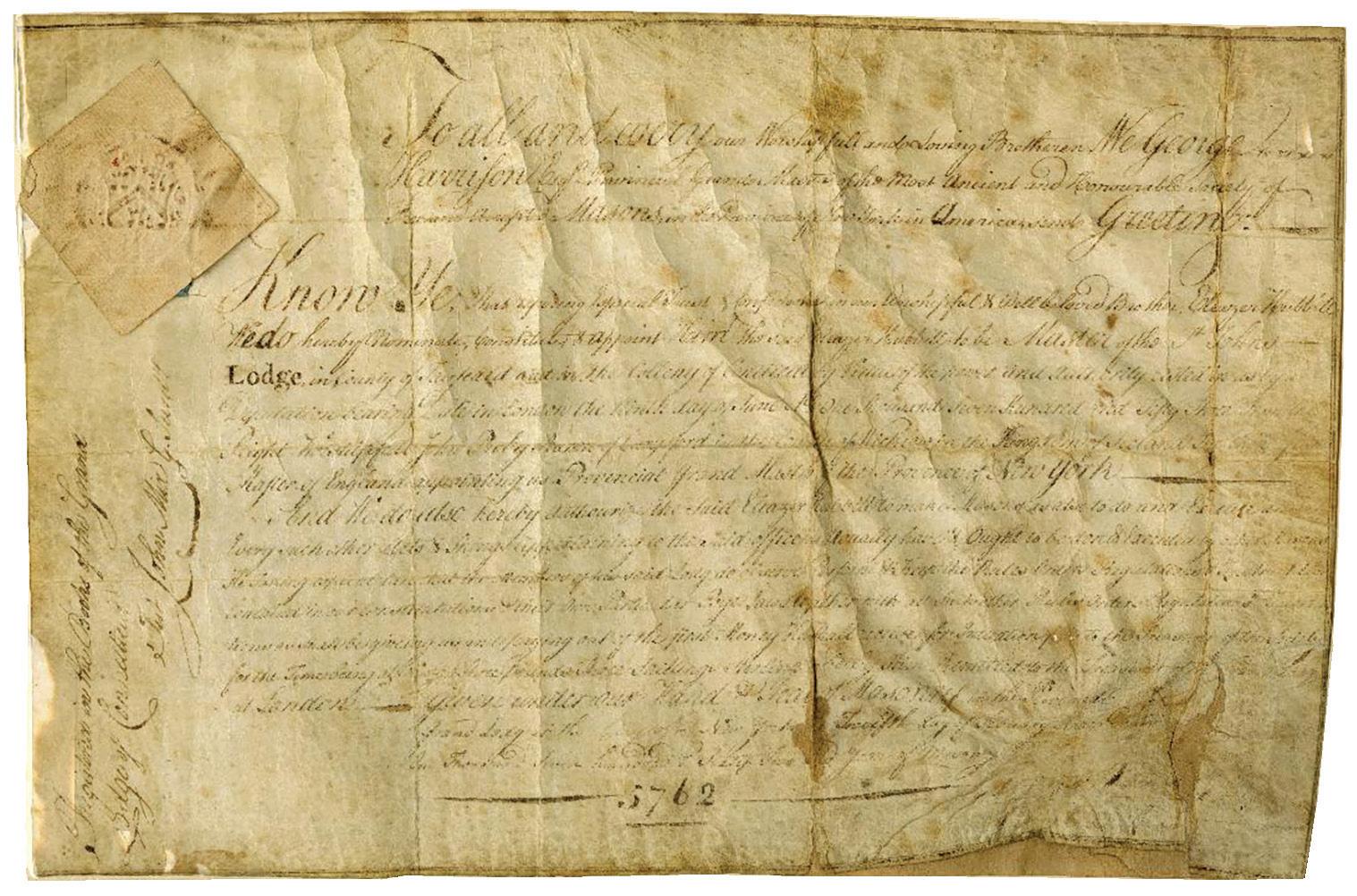

Seeking funds to preserve Sun Tavern, Matis conducted a presentation at the lodge which led to a major donation from The Connecticut Freemasons Foundation. Masons were thrilled to help preserve a meeting place of St. John’s Lodge No. 3, the first lodge in Fairfield County. Established in 1762, its charter bears the date 5762 because Freemasonry adds four thousand years to the Common Era to symbolically allude to the creation of the world.

The author leading a Masonic meeting seated in the Windsor armchair preserved from 1762.

DANIEL REGAN

In gratitude, Fairfield Museum gave permission for the 2012 meeting. To augment the rich physical setting members wore period clothing, from Continental Army uniforms, Scottish kilts and the cotton waistcoats and silk stockings of country gentlemen to the humble go-to-church-andweddings linen and wool of farmers and tradesmen.

Ascending the narrow steps to the second floor, Masons entered the room George Washington, their eminent Brother, likely was given for his overnight stay. With candlelight playing upon the room’s 12-inch planks and open hearth, members performed the Master Mason degree with centuries-old precision.

Stewards of artifacts safeguard their preservation, but the Sun Tavern experience demonstrates that allowing their original use, even briefly, can nourish the surviving spiritual and intellectual culture of historic groups. In this case, Freemasons were invigorated and Fairfield Museum gained access to the fraternity’s private records and an understanding of its activities.

When Masons gather, they strive to create an ideal community in which religious, political, racial, and class differences yield to their common humanity. Efforts to live according to these Enlightenment principles, embedded in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution by Brother Benjamin Franklin and many others, play out imperfectly across the arc of our national history. Fairfield Museum now understands what this looks like at the local level.

Charter of St. John’s No. 3 dated February 12, 5762 or 1762 in common usage.

This story first appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of Connecticut Explored, the magazine of Connecticut history, ctexplored.org.