The Nueva Way

A V E U N S C H O O L E H T 01 A workbook AUGUST 5 2020

LEARN BY CARING, LEARN BY DOING

Mission

Our school community inspires passion for lifelong learning, fosters social and emotional acuity, and develops the imaginative mind.

Vision

The Nueva School uses a dynamic educational model to enable gifted learners to make choices that benefit the world.

Values

‣ A dynamic learning community

‣ An environment of trust

‣ Social-emotional acuity

‣ Curiosity and creativity

‣ Passion and excellence

‣ Student agency

2018 graduate Lucy Wallace so eloquently described her time at Nueva in her graduation speech, highlighting the joy and wonder of her experience as a student and member of this community. There is no better way to introduce this Nueva Way workbook than through the perspective of one of our students. Take a few minutes to watch Lucy’s grad speech.

WATCH

02 © The Nueva School 2020

Introduction to the Nueva Way

To maintain our steadfast commitment to our mission, vision and values we must keep our purpose front and present. We must live what we believe and it should be obvious in our actions, interactions and in the dailiness of life at Nueva. We know that Nueva’s faculty and staff are the creators, keepers and developers of the conditions for our school to thrive and meet our lofty goals. As a member of the Nueva community, you will hear the phrase “ The Nueva Way ” and this workbook was developed to explicate and show how the Nueva Way works.

To help you better understand and engage in your own inquiry into Nueva’s ethos, the Nueva Way has been defined through 7 principles:

This workbook contains readings, videos, exercises and reflections to help deepen our understanding of and relationship with each of these principles. It is through our deep understanding and a shared commitment to these values that we will keep the Nueva Way thriving and alive for all of our community.

Take time to review each of the principles, engage in the readings, listen to the voices of the students, faculty and staff through the videos and text and respond to the questions/ reflections. We will come together in August as a community of faculty/staff to collaboratively unpack these principles and develop a shared understanding of this place we love so much.

PLEASE NOTE A FEW THINGS:

‣ The principles were carefully sequenced and build upon each other. The first five principles define the main ideas of the Nueva Way (the ‘what’) and the last two principles help describe the ways we enact the ideas (the ‘how’).

‣ We have attempted to include examples from all across our school and we will continue to add to the workbook to ensure a large cross section of representation.

Our Values:

A Place of Belonging for Gifed Learners 1 A Love of Lifelong Learning 2 3 4 5 6 7 A Student-Centered School Fostering Social Emotional Acuity & Kindness Building a Beloved Community A Nimble & Innovative Spirit

Embodied & Visible

7

03

SUMMARY

PRINCIPLES

© The Nueva School 2020

Principle

A place of belonging for gifted learners

“We create a community of belonging where all gifted students are seen, valued, and nurtured for who they are, so that they thrive in all areas of their development.”

The first principle to explore is A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners.

“Nueva is a sanctuary for gifed learners. Our gif to them is a chance to explore oneself fully.”

DIANE ROSENBERG 2019

In this section we will deepen our understanding of the students that we serve and see how we can create the sanctuary Diane describes.

GETTING STARTED 1 1 04 © The Nueva School 2020

REFLECTION: IMAGINING GIFTEDNESS

What is your understanding of gifedness? Draw or describe a gifed child.

What do you imagine a school for gifed learners would look like?

What questions or concerns do you have about working with gifed learners?

1 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners

2

3 05 © The Nueva School 2020

Mark which of these students you think may be gifted and give your reason why:

Viet

“Viet is a sixteen-year old student who seems incredibly bored in your History class. He falls asleep a couple of times over the course of the semester. He doesn’t seem to do the readings, or if he does, he never comments in class. When his laptop is up, he seems distracted, probably by games, but you never catch him playing. His homework comes in late sometimes, and there are some interesting ideas buried in his essays, you think, but it’s hard to tell because his writing is very weak grammatically.”

“Willow is a thirteen year old who gets in all her homework on time and in perfect condition, for every class. Her handwriting is extremely neat. She participates at the state level in math competitions and routinely places in the top three. Her writing is more advanced than her age level, and she always edits it without asking. She is also a competitive swimmer, but rarely has trouble keeping her schedule balanced. In her free time, she reads non-fiction books and hikes. She is very emotionally centered and often helps her friends process their feelings.”

Quincy

“Quincy is a ten-year-old who loves soccer and basketball, and would prefer to be out on the field at all times. His interest in class is wildly variable; sometimes, especially with a hands-on activity, he lights up, and his science teacher reports that he built a complicated circuit faster than any other student in the class. He had a very hard time verbally explaining why it worked, however. He likes video games and is extremely dexterous at them, famous among his peers for often achieving a high score. He also loves to draw and doodle, which can distract him in class, and his homework mostly comes in a little sloppy. He is often quite happy and even-keeled.”

“Leigh, a seven year old, is struggling with school, and especially seems to have an issue with authority. They argue vehemently with their teachers in class and out, and when teachers ask that they stop arguing and follow instructions, their reactions can be extreme and involve throwing things or screaming. They seem very fixated on the concept of what is fair and not. This behavior doesn’t seem to happen quite the same way at home, their parents report, where they do a lot of art and have a particular interest in ice-skating.”

“Anjali is a five year old student who has excessive energy at all times. She talks almost constantly, asking questions about everything, from how your morning coffee is made to why animals die to whether dinosaurs could smell well. She frequently interrupts when others are talking in class and at home. When she gets tired, she refuses to go to sleep and cries about injustice in the world, like jaguars losing their habitats and homelessness. She is very sensitive to seams and tags in clothing, and prefers seamless leggings and to have the tags cut out of everything. She doesn’t want to learn how to read, preferring her parents read to her.”

ACTIVITY: IDENTIFYING

06

GIFTEDNESS

© The Nueva School 2020

Willow

Leigh

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners

Anjali

REFLECTION: IDENTIFIYING GIFTEDNESS

All of these students are students whom we have taught over the years and who are gifted students. That being said, not all were treated or seen as such at the time. As you answer the following questions, consider the students and children you’ve encountered over the years and whether or not they might have been gifted.

What information might you need to better determine if a student is gifed and/or would thrive in a school for gifed learners?

How might factors like gender, race, and class influence whether or not a child is identified as gifed? Consider the examples; would your perception of each child and their potential gifedness change if they had a different gender identity or if you knew their racial identity or class status?

07 © The Nueva School 2020

2 1 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners

DEFINITIONS: DEFINING GIFTEDNESS

There are many different ways that giftedness is defined. Here are several definitions to consider:

National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC)

“Gifted individuals are those who demonstrate outstanding levels of aptitude (defined as an exceptional ability to reason and learn) or competence (documented performance or achievement in top 10% or rarer) in one or more domains. Domains include any structured area of activity with its own symbol system (e.g., mathematics, music, language) and/or set of sensorimotor skills (e.g., painting, dance, sports).”

Annemarie Roper

“Giftedness is a greater awareness, a greater sensitivity, and a greater ability to understand and transform perceptions into intellectual and emotional experiences.”

“Giftedness is Asynchronous Development in which advanced cognitive abilities and heightened intensity combine to create inner experiences and awareness that are qualitatively different from the norm. This asynchrony increases with higher intellectual capacity. The uniqueness of the gifted renders them particularly vulnerable and requires modifications in parenting, teaching, and counseling in order for them to develop optimally.”

© The Nueva School 2020

08

The Columbus Group

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted

Learners

REFLECTION: DEFINING GIFTEDNESS

What questions, thoughts, or reactions do you have about these different definitions?

Which definition is most intriguing or resonant for you? Why?

In what ways do these definitions align and in what ways are they different? Why might this be?

09 © The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3

Principle 1 A Place of

Belonging for Gifted Learners

Understanding Giftedness

Our Guiding Defnition

At Nueva, we most identify with The Columbus Group’s definition of giftedness.

“Giftedness is Asynchronous Development in which advanced cognitive abilities and heightened intensity combine to create inner experiences and awareness that are qualitatively different from the norm. This asynchrony increases with higher intellectual capacity. The uniqueness of the gifted renders them particularly vulnerable and requires modifications in parenting, teaching, and counseling in order for them to develop optimally.”

We understand that all definitions come with the potential for misidentification or lack of identification. As such, we strive to make sure that we both identify gifted students who need our environment to thrive and that our environment is truly nurturing to the widest possible range of gifted students we can support.

A High Achiever vs. A Gifed Learner

A HIGH ACHIEVER

‣ Knows the answers

‣ Is interested

‣ Is attentive

‣ Has good ideas

‣ Works hard

‣ Commits time and effort to learning

‣ Answers questions

‣ Absorbs information

‣ Copies and responds accurately

‣ Is a top student

‣ Needs 6 to 9 repetitions for mastery

‣ Understands ideas

‣ Grasps meaning

‣ Completes assignments

‣ Is a technician

‣ Is a good memorizer

‣ Is receptive

‣ Listens with interest

‣ Prefers sequential presentation of information

‣ Is pleased with his or her own learning

A GIFTED LEARNER

‣ Asks the questions

‣ Is highly curious

‣ Is intellectually engaged

‣ Has original ideas

‣ Performs with ease

‣ May need less time to excel

‣ Responds with detail and unique perspective

‣ Manipulates information

‣ Creates new and original products

‣ Is beyond their age peers

‣ Needs 1 to 2 repetitions for mastery

‣ Constructs abstractions

‣ Draws inferences

‣ Initiates projects

‣ Is an innovator

‣ Is insightful; makes connections with ease

‣ Is intense

‣ Shows strong feelings, opinions, perspective

‣ Thrives on complexity

‣ Highly self critical

10

© The Nueva School 2020 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Understanding Giftedness

From “The Gifted and Talented Child” by Janice Szabos, Maryland Council for the Gifted and Talented

Te Five Overexcitabilities

Excerpt from Living with Intensity, by

Michael Marian Piechowski and Susan Daniels

Overexcitability is an innate tendency to respond in an intensified manner to various forms of stimuli, both external and internal (Piechowski, 1979, 1959). Overexcitability is a translation of the Polish word which literally means “super-stimulatability.” (It should have been called superexcitability.) It means that persons may require less stimulation to produce a response, as well as stronger and more lasting reactions to stimuli. Another way of looking at it is of being spirited —“more intense, sensitive, perceptive, persistent, energetic” (Kurcinka, 1991).

There are five forms of overexcitability in Dabrowski's theory: psychomotor, sensual, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional. Each can have a wide range of expressions. The forms of overexcitability appear to be the necessary—but not sufficient— raw material for advanced, multilevel development.

Overexcitability means that life is experienced in a manner that is deeper, more vivid, and more acutely sensed. This does not just mean that one experiences more curiosity, sensory enjoyment, imagination, and emotion, but also that the experience is of a different kind, having a more complex and more richly textured quality.

Overexcitabilities impart an intense aliveness to those who experience them. They may be thought of as distinct modes of experiencing or as channels through which flow the color tones, textures, insights, visions, emotional currents, and energies of experience. An analogy is often made in many streams of information from far and near, in contrast to the old rabbit ears antenna limited to local channels

only. Behaviors and characteristics that frequently typify the five forms of overexcitability (OE) can be described briefly as follows [note: here we use Duke university’s wording, as it also highlights behavioral manifestations]:

PSYCHOMOTER

Refers to a surplus of energy. Manifestations include extreme enthusiasm, rapid speech, love of intense activity, and impulsive actions.

SENSUAL

Seen in those with an enhanced level of sensory experience and is marked by the pursuit of pleasure through the senses. Manifestations may include seeking enhancing stimuli or removing oneself from stimuli.

INTELLECTUAL

Associated with striving for knowledge and truth through questioning, discovering, and analyzing, but it is not the same as intelligence, which is seen as an ability.

IMAGINATIONAL

Characterized by daydreaming, fantasizing, dramatization, and the use of imagery and metaphors.

INTELLECTUAL

Marked by an intensified level of interpersonal relations to people, things, and places, and compassionate feelings for others.

It would be hard to find a person of talent who shows little evidence of any of the five overexcitabilities. They are the underlying dimensions of thinking outside the box, the urge to create beauty, the push for stark realism, the unrelenting striving for truth and justice (Piechowski, 1979, 1999).

© The Nueva School 2020

Unfortunately, the stronger these overexcitabilities are, the less peers and teachers welcome them. Developing understanding that this is the child’s or adult’s innate makeup facilitates tolerance and acceptance—and, one hopes, even an appreciation of these fertile qualities.

The picture of superexcitability painted above assumes that these intensities and sensitivities are more or less on the surface, easy to notice. However, as Jackson and Moyle point out (Chapter 7), they are sometimes deeply hidden and therefore hard to notice. In fact, some gifted children protect themselves and try to hide their extreme sensitivity so that they give the mistaken impression of being unemotional, impassive or indifferent, and unresponsive to social cues.

“[Some] gifed children protect themselves and try to hide their extreme sensitivity so that they give the mistaken impression of being unemotional…”

When adults encounter high levels of sensitivity and intensity in children, they may not know how to respond to assist those children. Yet the challenges are even more acute for young gifted children who may not understand their own sensitivity and intensity.

11

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Understanding Giftedness

Asynchronous Development

Excerpt from “Many Ages at Once” by Lisa Rivero in Psychology Today

What is normal development for a gifted child? Many people assume that the brightest children in the classroom are the ones who are most able to pay attention, to sit still, to do their work, and to conform to the expectations of authority. They are the children who know how to act their age, at least; or, even better, they display unusual maturity. They fit in and are easy students to teach.

Parents, teachers, and others who live and work daily with these children know differently. Many young highly intelligent children are out of sync with their classmates and their environment, what one definition of giftedness, developed in 1991 by a group of professionals and parents concerned about an overemphasis on achievement, refers to as asynchronous development:

"Giftedness is 'asynchronous development' in which advanced cognitive abilities and heightened intensity combine to create inner experiences and awareness that are qualitatively different from the norm. This asynchrony increases with higher intellectual capacity. The uniqueness of the gifted renders them particularly vulnerable and requires modifications in parenting, teaching, and counseling in order for them to develop optimally.”

Brain imaging research provides evidence for this developmental difference in the maturation of very bright children. In 2006, researchers from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Montreal Neurological Institute at McGill University showed that children with greater than average intellectual ability "demonstrate a particularly plastic

cortex" in which the building up phase of the cortex, when connections are formed that allow for high-level thinking, begins and ends later than average (reaching its peak at roughly age eleven or twelve as opposed to seven or eight), and the subsequent thinning or pruning phase of cortical development is rapid.

One of the study’s authors, neuroscientist Jay Giedd, explains the process as one of sculpting:

"Right around the time of puberty and on into the adult years is a particularly critical time for the brain sculpting to take place. Much like Michelangelo's David, you start out with a huge block of granite at the peak at the puberty years. Then the art is created by removing pieces of the granite, and that is the way the brain also sculpts itself. Bigger isn't necessarily better, or else the peak in brain function would occur at age 11 or 12. ... The advances come from actually taking away and pruning down of certain connections themselves."

The block of granite in this analogy is cortical thickness, which slowly builds up in children until pre-adolescence, at which time redundancies and unused parts are whittled away, leaving behind our adult, sculpted "David" brain. The results of the study suggest that not only does the block of granite stop building up at a later age for gifted children, but that the sculpting phase may end later as well. The sculpting (or thinning or pruning) process is one of greater brain efficiency and eventually allows for mature executive processing skills of planning, organization, and goal setting (one reason why teens for whom this process is not complete do not always

take into account the consequences of risky behavior). Highly intelligent young children also have a thinner cortex to begin with, before the store of granite begins to build. Just as interesting is that brain imaging research suggests that children with ADHD also experience a later than average peak of thickening in specific areas.

"One hallmark of creative gifedness is the ability to remain resilient and child-like, to suspend reason or entertain multiple forms of it."

So, what does this mean, exactly, and why is it important? First, the asynchronous development of gifted children is not a bad thing. As M. L. Kalbfleisch writes in The International Handbook of Giftedness, "One hallmark of creative giftedness is the ability to remain resilient and child-like, to suspend reason or entertain multiple forms of it." Brain development that is delayed or prolonged may allow children more time for intellectual exploration, creativity, and growth.

Adults should know that gifted children will not necessarily fit comfortably within a group of age peers or meet the usual expectations in terms of their development. For young children, this lack of fit may lead to misdiagnoses or premature diagnoses of learning and other disorders. When parents, teachers, and health care providers do not understand the longterm, complex developmental road of giftedness, they may be tempted by the academic precocity of gifted children to place an inordinate…

More on next page

12

© The Nueva School 2020

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for

- Understanding Giftedness

Gifted Learners

Asynchronous Development

…emphasis on early achievement and fulfillment of adult expectations. Also, we might expect older gifted students to have more mature judgment at an earlier age than their classmates, even though the reverse can be true. As Dr. Nadia Webb, a neuropsychologist and co-author of Misdiagnosis and Dual Diagnoses of Gifted Children and Adults, explains , "Phenomenal intellects can coexist with mediocre executive functioning skills."

How much of the gifted developmental difference is due to nature or nurture (or whether such a dichotomous question is even the right one to ask) will continue to be debated, and more research is needed to understand more fully the developmental process and its implications. For now, parents, teachers, and health care professionals can remember that single snapshots of a child at a specific age can be misleading and that very bright

Characteristics of Gifed Students

AFFECTIVE

‣ Well developed sense of justice

‣ Emotional intensity

‣ Preference for older friends

‣ Different concepts of friendships

‣ High levels of empathy

‣ Asynchrony

‣ Mature sense of humor

‣ Can be perfectionistic

‣ “Overexcitabilities”

COGNITIVE

‣ Unusually well developed memory

‣ Curiosity

‣ Dislike of slow-paced instruction

‣ Reasons at a higher level than chronological peers

‣ Rapid learning

‣ Preference for independent work

‣ Have multiple interests

‣ Ability to generate original ideas

‣ “System thinkers” rather than linear thinkers

‣ Immersion learners

© The Nueva School 2020

children may experience neurodiversity that affects their behavior in complex ways. The international non-profit organization SENG (Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted), of which I am a director, is spearheading a public awareness effort to educate pediatricians and others who work and live with young gifted children of the potential for misdiagnosis of ADHD and other disorders, the symptoms of which overlap with traits of giftedness.

Other areas of note to keep learning about:

13

(part

2 of 2)

Perfectionism I Sensitivity II Intensity III Introversion IV Twice Exceptionality V

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Understanding Giftedness

As you think about all you’ve begun to learn about gifedness, how does it change what you think a supportive and challenging learning environment for the gifed student might look like?

How about a supportive social environment?

How might learning differences mask or amplify certain aspects of gifedness?

14

REFLECTION: SUPPORTING GIFTEDNESS

© The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Understanding Giftedness

Gifted Ed in Theory & at Nueva

Rights of the Gifed Child

Written by Del Siegle, NAGC President, 2007-2009

You have the right to:

‣ Know about your giftedness

‣ Learn something new everyday

‣ Be passionate about your talent area without apologies

‣ Have an identity beyond your talent area

‣ Feel good about your accomplishments

‣ Make mistakes

‣ Seek guidance in the development of your talent

‣ Have multiple peer groups and a variety of friends

‣ Choose which talent areas your wish to pursue

‣ Not be gifted at everything

Is It a Cheetah?

Excerpt from article by Stephanie

S. Tolan

It's a tough time to raise, teach or be a highly gifted child. As the term "gifted" and the unusual intellectual capacity to which that term refers become more and more politically incorrect, the educational establishment changes terminology and focus.

Giftedness, a global, integrative mental capacity, may be dismissed, replaced by fragmented "talents" which seem less threatening and theoretically easier for schools to deal with. Instead of an internal developmental reality that affects every aspect of a child's life, "intellectual talent" is more and more perceived as synonymous with (and limited to) academic achievement.

The child who does well in school, gets good grades, wins awards,

and "performs" beyond the norms for his or her age, is considered talented. The child who does not, no matter what his innate intellectual capacities or developmental level, is less and less likely to be identified, less and less likely to be served.

A cheetah metaphor can help us see the problem with achievementoriented thinking. The cheetah is the fastest animal on earth. When we think of cheetahs we are likely to think first of their speed. It's flashy. It is impressive. It's unique. And it makes identification incredibly easy. Since cheetahs are the only animals that can run 70 mph, if you clock an animal running 70 mph, IT'S

A CHEETAH!

But cheetahs are not always running. In fact, they are able to maintain top speed only for a limited time, after which they need a considerable period of rest.

It's not difficult to identify a cheetah when it isn't running, provided we know its other characteristics. It is gold with black spots, like a leopard, but it

also has unique black "tear marks" beneath its eyes. Its head is small, its body lean, its legs unusually long—all bodily characteristics critical to a runner. And the cheetah is the only member of the cat family that has nonretractable claws. Other cats retract their claws to keep them sharp, like carving knives kept in a sheath the cheetah's claws are designed not for cutting but for traction. This is an animal biologically designed to run.

Its chief food is the antelope, itself a prodigious runner. The antelope is not large or heavy, so the cheetah does not need strength and bulk to overpower it. Only speed. On the open plains of its natural habitat the cheetah is capable of catching an antelope simply by running it down.

While body design in nature is utilitarian, it also creates a powerful internal drive. The cheetah needs to run!

15

© The Nueva School 2020 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Why Gifted Ed?

READ FULL ARTICLE

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Ways We Think of Giftedness at Nueva

If Frankenstein Went To Nueva

Transcript of graduation speech by Lucy W., Nueva ‘18

One night at dinner about five years ago, my father told me about an NPR segment he had recently heard. The show featured a scholar of alternative histories, a woman who investigated questions like, “What if Napoleon had had a machine gun?” or “How would World War II have gone if Eleanor Roosevelt could fly?” I was eight at the time, and still not entirely clear on the difference between Napoleon and Neapolitan ice cream, so I didn’t give the idea much thought. Now, I have one such question of my own to pose today: What if Victor Frankenstein had gone to Nueva?

Now, just to be clear, this speech is not going to devolve into accusations of witchcraft or theories about a terrifying creature hidden in the back of the gym. And I realize that Frankenstein might not have even made it past the admissions office – after all, “We support the creation of history’s most notorious monsters” wouldn’t sound so great on a brochure. Instead, I want to direct your attention to another feature: the novel’s beginning, and the factors that led Frankenstein to create his namesake monster in the first place.

Victor Frankenstein is a Nueva kid. Over the course of my time here, “Nueva” has been incorporated into my vocabulary not just as a proper noun, but also as an adjective. It refers to both a community and a worldview – unbridled intellectual energy, an ardent desire for knowledge, and endless efforts to achieve it.

Frankenstein has all of these qualities. He mentions his “thirst for knowledge” at every moment possible, describing the universe as “a secret which I desired to divine,” experiencing “gladness akin to rapture” upon

studying science. It’s like an admissions packet come to life. I see these same traits reflected throughout my Nueva experience. One of the things I most love about our class is the unique way in which each one of us finds beauty and fascination in the most unlikely places. Whether it’s underwater hockey or economic policy, Nueva students share Frankenstein’s sense of rapture in the areas they care about, and it is this infectious joy that makes Nueva such a special place. Plus, I have a feeling Frankenstein would have no problem finding extracurricular activities. After all, reanimating a corpse is just a slight variation of a robotics competition.

For all these reasons, I imagine that Frankenstein might be a perfect fit for the school. However, it is also worth remembering that he faced some personal challenges throughout his life. While Frankenstein adores science and the pursuit of knowledge, this level of passion can be overwhelming and exhausting. His temper is “sometimes violent,” his passions “vehement.” When he has no access to educational resources, he is left to “struggle with a child’s blindness,” and he describes himself as “occupied by exploded systems, mingling a thousand contradictory theories.” Though Frankenstein and I don’t have too much in common, I think I know what he means here. The desire to learn is a wonderful thing, and also a challenge. At times, I feel like my mind moves so fast I can barely breathe, spinning through iterations and schemes and crazy ideas, at least thirty percent of which are almost certainly illegal. And before I came to Nueva, these difficulties were almost unmanageable. The purpose of school seemed to be not learning, but following the rules. I

© The Nueva School 2020

remember one time in second grade when I dutifully worked my way through several packets of simple math problems. I brought the packets to my teacher, eager to move on and learn more. But when she handed me a new packet, I was dismayed to find that the problems in this one were of the exact same kind as the last batch. I started to see school as a chore I had to drag myself through, and not only did this make weekdays miserable, it also left me on my own to deal with the wildness and constant motion of my own mind.

Thankfully, I found Nueva. Nueva is ready and eager to handle the intensity of its students, to take this kind of ardent, nineteenth-century, conquerthe-universe desire for knowledge and use it as a tool for the good. I have countless joyful memories of my first year, and the following ones brought many more of these magnificent adventures. By the time high school rolled around, the feats of our grade were truly spectacular. A sensational production of Heathers, countless fire alarms during block six in ninth grade, succulents blooming all over campus, and the buzz of sound that emerges from debaters’ mouths while they are “spreading” – these are just a few of the countless marvels of the last four years. Through these exploits, we built a community of excitement, exploration, and enthusiasm, one that made me feel valued and connected, proud of who I was and grateful for the people surrounding me. Nueva has played a huge role in helping me deal with the challenges that Frankenstein also faced, and today, I can proudly say that I have…

More on next page

16

If Frankestein Went to Nueva

…made it through seventeen years of life without creating a single deadly science experiment.

So, to go back to the question with which I began, what would have happened if Frankenstein had gone to Nueva? I think he would have thrived. He would have worked towards the understanding of the universe he so desired, at the same breakneck speed, but with friends and teachers to guide him and a design-thinking template to make sure he’s brainstorming properly and some strictly enforced guidelines around flammable materials. He would have explored other things, too, taking

a painting class or joining cross-country or reading an oddly familiar nineteenth-century novel in ninthgrade English. He wouldn’t have been alone in his discoveries, and he would have had the chance to balance tireless study with human contact. And at the end of his senior year, he would be a part of what I see here today: a group of caring, committed people who are fearlessly dedicated to exploration. We will all face hard times in our lives, and intense curiosity is not always easy to manage. But the last four years have given me confidence that we will all rise to the challenge. Frankenstein begins not with Victor Frankenstein’s

narration, but with the letters of the sailor who meets him in the Arctic. I find these passages the most beautiful pieces of the book, and the best to encapsulate my love for Nueva. Thus, I want to end with this sailor’s words.

“There is something at work in my soul which I do not understand...there is a love for the marvelous, a belief in the marvelous, intertwined in all my projects, which hurries me out of the common pathways of men, even to the wild sea and unvisited regions I am about to explore.” May all of us retain this belief in the marvelous and carry it with us wherever we go.

How We Got Here

Statement by Diane Rosenberg, Head of The Nueva School 2001-2020

The reason the Board and community so easily affirmed our mission, vision, and motto has a rich, complicated history. It’s only easy now because it was so hard for so long. Throughout our history, our school has struggled to maintain its identity as a school that serves a particular population, a population that some would describe as a special-needs population.

California, unlike some other states, dismantled gifted and talented programs decades ago. Other states, like Maryland, have long safeguarded funding for gifted and talented programs by identifying this population as a population with different learning needs, not dissimilar in that regard from students at the other end of the learning spectrum. Educators

everywhere recognize that meeting this range of needs requires more than a talented teacher who is able to differentiate instruction within the classroom. The pace at which students learn, the breadth of knowledge they bring, and the depth of questions they ask are simply different. They are not better, not worse. They are just different, and these gifted learners are as deserving of our societal attention as all other learners are.

While the 1960s were a time of great hope and a time of social progress, the egalitarian spirit, while well-intended, dismantled critically important educational programs. The intention was not unlike Leave No Child Behind — well intended and inadvertently leaving many behind.

© The Nueva School 2020

This egalitarianism took on a spirit of anti-intellectualism as populism swept the nation. Intellectuals were ridiculed and there were clear political shifts from prizing intellectuals as leaders to prizing a man-of-the-people as a leader — charisma more than content. Scientists and academicians lost their midcentury status, and so did students at the top. “All students are gifted” became a phrase preferred to “all students have gifts.” As educators, we were quick to identify students as gifted artists, musicians, athletes, or actors, but we were reluctant to identify students as gifted learners. In a reaction to scholastic achievement as the measure of a young person, identifying

More on next page

17

A

Principle 1

Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Ways We Think of Giftedness at Nueva

(part 2 of 2)

How We Got Here

…gifted learners and creating special programs for them seemed to diminish the potential of all others. This antiintellectual shift had dramatic effects on programs throughout the nation. In the effort to be more egalitarian, the shift diminished what is simply natural and normal for this population of student learners. It was for this very reason that Nueva was founded and continues to thrive today. Ours is the gift of being normal. That is Nueva’s single greatest gift to our students.

Because American society has struggled with identifying the population our programs were designed to serve, Nueva has struggled with the weight of an unfortunate label. While we are devoted to our mission and the population we serve, we have long struggled with the label “gifted.”

“Because American society has struggled with identifying the population our programs were designed to serve, Nueva has struggled with the weight of an unfortunate label.”

It’s ironic that while elite sports are championed and well-funded, academic programs for an equally talented population are not. Instead, the students themselves, not just the programs, are labeled as elitists. We know that Nueva provides a safe haven, emotionally and intellectually, for gifted learners. In the early years, the school used “gifted,” “high potential,” and “high achieving” interchangeably. We have many, including in our own community, who would like us to use “high potential” or “high achieving.” It’s simply more socially acceptable, although “high achieving,” in particular, is often quite different from gifted. Some parents who happily choose Nueva for programs and peer group often wish that, once

their own children are enrolled, would abandon our stated public mission.

This has caused soul-searching and mission drift over the years. In 1994, the school had lost its way. The Harvard School of Education was brought in by the Board to determine what the school needed to do. What the researchers found was that Nueva had joined the pack and defined gifted along with others: “all children are gifted.” If a child was a gifted musician but not a gifted student in the classroom, that was fine and the child was admitted. If a child was a gifted artist but did not do well academically, that child was admitted. The advisers deemed the IQ range unsustainable — 100 to 175 — and the school was serving no one well.

The recommendation was to reclaim the school’s distinctive mission and redefine the academic range to encompass gifted to profoundly gifted. The Board affirmed this recommendation.

Just as the school was rediscovering itself, it imploded. In 1997, the school went from a stable school of nearly 300 students to a school in crisis when the Middle School head was fired by the Board, the Head of School resigned in protest, and the founder stepped off the Board. The school nearly closed that summer. Six members of the Board and an equal number of committed faculty kept the school afloat and the vision of what could be alive. That winter, the Board hired Andrew Buyer to begin as the new Head of School in July 1998. Andrew arrived with a sense of optimism and possibilities, eager to help heal and shape this community.

But Andrew did not believe in the school’s mission. He believed in progressive education, and for the first time in the school’s history, the school labeled itself as a progressive school, but not as a school serving gifted learners. The school joined the progressive network but stopped presenting at the California Association

country. Qualifications for admission were widened yet again; IQ was once more becoming a soft measure.

Because so many seasoned faculty had left the school in the debacle, Andrew hired many new, inexperienced teachers, who were drawn to the sense of possibilities and the start-up nature of the school. There was tension between seasoned Nueva faculty, who wanted to hold on to the values of the old Nueva, and the younger faculty, who felt this was a time to create a new mission. Within two years, there were serious tensions between the Head of School and Board about the school’s mission. The school entered a strategic planning phase, engaging the full community to envision its future. The Board, many faculty members, and nearly all parents affirmed the school’s original mission to serve gifted learners. It was also during this strategic planning phase that the vision and mission were rewritten and our motto created. The head realized this was not a mission he could support and decided to leave. A new head was hired. Diane Rosenberg began in 2001.

The first three years were a struggle for this new head with the newly hired Nueva faculty — a battle over the school’s mission and direction. The head asked the Board to vote to affirm the mission and to issue a public statement about the school’s direction. The head was given the directive to make the necessary changes, which resulted in the departure of 27 (of 70) faculty, staff, and aides. This permitted the silenced, seasoned faculty to begin to lead again, shaping distinctive curricula, reasserting the school’s mission. The school entered the 2004 strategic planning process with enthusiasm. All were brimming with new ideas. Admissions were strong and the school was growing. It was clear the school would reach the cap of 400, and it was obvious that lack of facilities was constraining programs and ideas.

18

© The Nueva School 2020

A

More on next page Principle 1

Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Ways We Think of Giftedness at Nueva

(part 2 of 3)

How We Got Here

(part 3 of 3)

It was clear the school would reach the cap of 400, and it was obvious that lack of facilities was constraining programs and ideas. The school considered adding the exploration of a new high school to the strategic plan but then took it out.

To educate all faculty about the qualities and characteristics of gifted students, the school decided to host a Gifted Learning Conference. Planning began in 2005 for the first 2007 conference.”

Planning began in 2005 for the first 2007 conference. The focus was on the needs of gifted students. We couldn’t afford to send all teachers to Confratute or NAGC, but we could bring an invigorating conference to our own campus, and our teachers were eager to create a distinctive experience of our own. They are both learners and learned.

We were also eager to educate the broader educational community about this special-needs population. We invoked Mission II, which was the first time it had been mentioned in several years.

There was a sense of Nueva as a phoenix rising, and it galvanized the community.

The 2012 and 2017 strategic plans reaffirmed with ease our core mission to serve a particular population. There was discussion and resolve. Our mission was clear. In our most recent plan, we decided we needed to stop being embarrassed or defensive about the label. We needed to redouble our outreach efforts. We all know there are gifted learners in every classroom in this country. We need to help their teachers identify those students and make sure these students don’t languish. We know they are at risk.

That will be our school’s next stage of growth — Mission II in action at a national level. We are in the process of creating not only a Giftedness Institute but a center. The pendulum is swinging and the time is right for Nueva to serve. We still have struggles with families who love what they see and want this population of learners for their children, but they certainly wish we would just “get rid of this label.”

“Te pendulum is swinging and the time is right for Nueva to serve.”

We still have teachers who choose Nueva for our constructivist approaches, the beauty of our campuses, the generosity of our community, and the pedagogical freedom, but are nevertheless uneasy with the mission. For those of us who have ever experienced mission mismatch, we know that rancor becomes more acute with time, not less. Dissatisfaction grows and there is a desire to change the school rather than find the courage in one’s self to seek a better match elsewhere. The Board knows this, too.

In the last six years of rapid expansion, we have experienced mission mismatch with some families, with some faculty, and with some administrators. We have also been privileged to have a cohesive Board with chairs who have led wisely. Because each member of the Board is deeply and personally committed to the students we serve, our mission anchors all decision-making. There is no wavering at the Board level, which allows teachers, staff, and administrators to focus on the execution of our collective vision.

This is our community’s great good fortune and our greatest strength. We have kept our eyes on the prize and

will weather the challenges in this period of great change and growth. We have been here before and we are stronger for the soul-searching we were forced to undertake. As we know all too well, schools are fragile places, and our history reminds us to be vigilant, aware, and humble.

19

© The Nueva School 2020

Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Ways We Think of Giftedness at Nueva

REFLECTION: UNDERSTANDING GIFTEDNESS

Reflecting on these snapshots of how Nueva community members feel about what Nueva is, answer for yourself: why is gifed education important?

What do you see as core to the Nueva gifed education that you want to learn more about, or that you are most drawn to helping with?

What further questions do you have? What else do you think you need to know or learn to best serve the needs of our students? Write them down and remember to ask them at New Faculty Orientation!

20 © The Nueva School 2020 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted Learners - Understanding Giftedness

1

2

3

REFLECTION: REMOTE GIFTED ED

What would you imagine are the particular vulnerabilities of gifed learners during remote learning? What considerations do we have to take into account? How might we design a remote experience that supports gifed students?

One Last Statement

We want to make sure it’s clear that you don’t need to be gifted to be a great teacher or supporter of gifted learners! The most important part of being a teacher or supporter of gifted students is honoring their lived experience and nurturing their growth intellectually, emotionally, socially, morally, etc., as you would for all students.

21 © The Nueva School 2020 Principle 1 A Place of Belonging for Gifted

- Understanding Giftedness

Learners

A lifelong love of learning

“We nurture and encourage a lifelong love of learning through joyous, authentic and rich learning experiences. We foster an environment where students pursue their intellectual curiosity and create learning that feels boundless.”

Our next principle asks us to foster in our students and ourselves, a love of learning. We seek to nurture in our students the lifelong pursuit of knowledge and experiences, both to help them understand themselves as gifted learners, and for the sheer joy that it brings. As Lucy stated,

“Tankfully I found Nueva. Nueva is ready and eager to handle the intensity of its students, to take this kind of ardent, nineteenthcentury, conquer-the-universe desire for knowledge and use it as a tool for the good.”

2

LUCY W, NUEVA ALUM, 2018 GRADUATION SPEECH

GETTING STARTED Principle 2 22 ©

School 2020

The Nueva

REFLECTION: YOUR LIFE OF LEARNING

Reflect on a time you felt truly engaged in learning. What were the conditions?

Reflect on your own educational experience with teachers. Has anyone in particular supported your own love of learning, and if so, how?

What needs to be true for joy to live in your classroom or in our school?

23 © The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3 Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning

Resources on a Love of Learning

What’s the Research on Motivation?

Excerpted from How Learning Works by Susan

A. Ambrose

When students successfully achieve a goal and attribute their success to internal causes (for example, their own talents or abilities) or to controllable causes (for example, their own efforts or persistence), they are more likely to expect future success. If however, they attribute success to external causes (for example, easy assignments) or uncontrollable causes (for example, luck), they are less likely to expect success in the future.

For instance, if a student attributes the good grade she received on a design project to her own creativity (ability) or to the many long hours she spent on its planning and execution (effort), she is likely to expect success on future design assignments. This is because she has attributed her success to relatively stable and controllable features about herself. These same features form These same features form the basis for her positive expectations for similar situations in the future.

24 © The Nueva School 2020

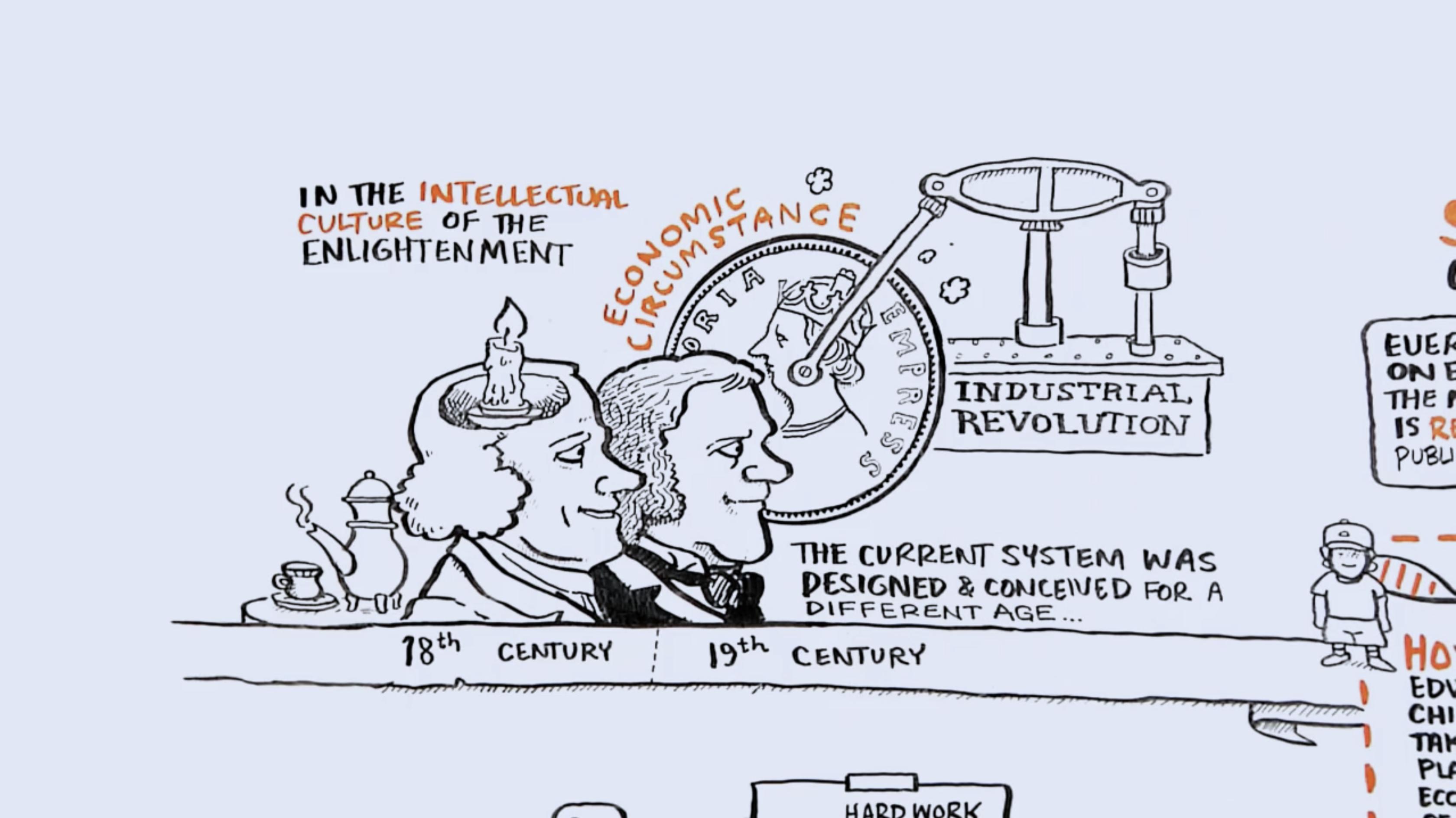

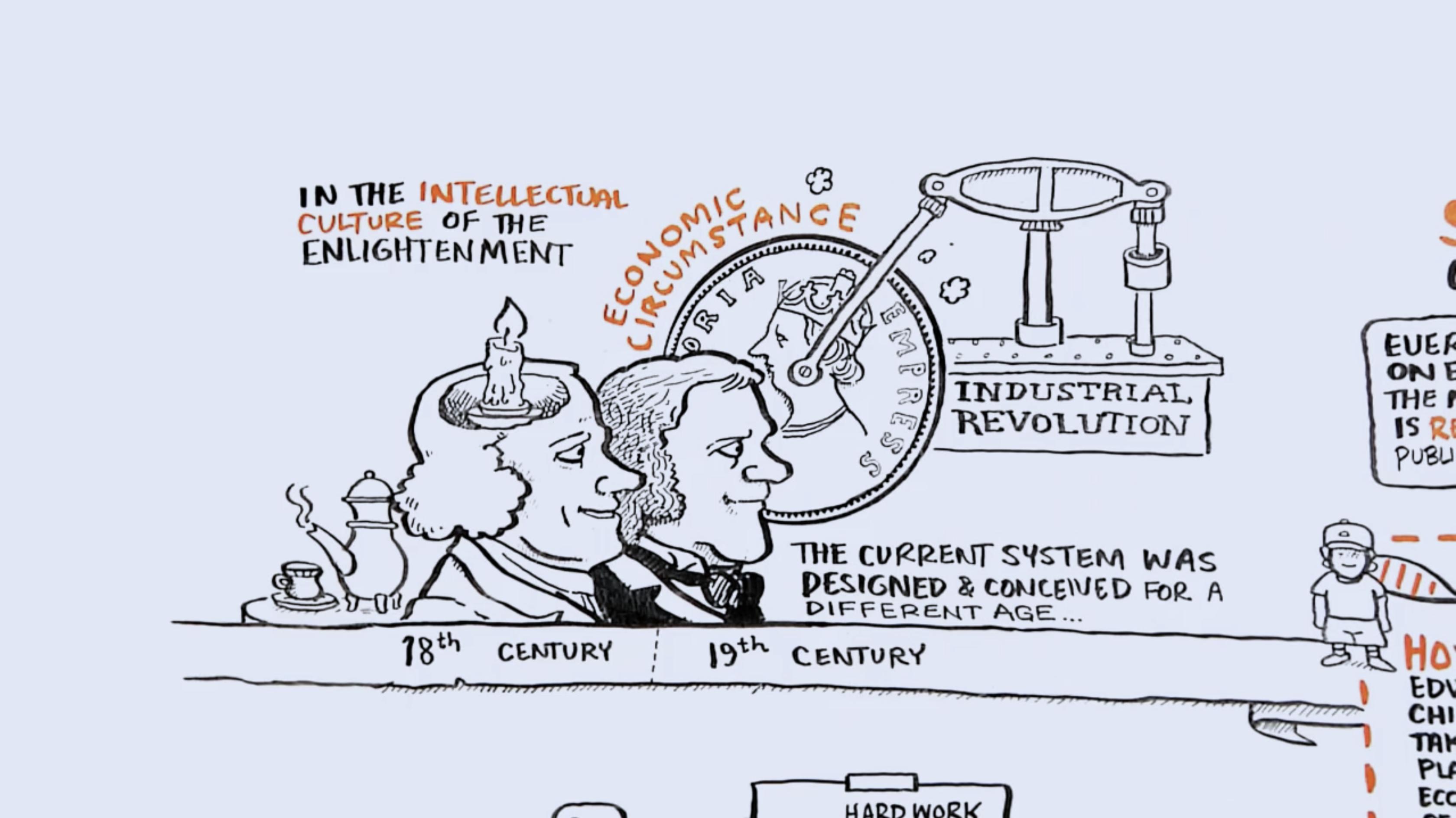

Show Off Student Work 5 Take Time to Tinker 6 7 8 9 10 11 Make School Spaces Inviting Get Outside Read Good Books Offer More Gym & Arts Classes Transform Assessments Find the Pleasure in Learning 1 Give Students Choice 3 4 Let Students Create Tings 2 Te Joys of Learning Collated from “Joy in School” by Steven Wolk Have Some Fun Together READ FULL ARTICLE Changing Paradigms WATCH An animated TED Talk

by Ken Robinson

READ FULL EXCERPT Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning

REFLECTION: READING RESPONSE

Afer reading, what are some of the ideas you are drawn to from the above resources? What would you like to explore?

What can you do and/or have you done as a teacher or supporter of students to set up an environment that nurtures intrinsic motivation? What about one that nurtures joy?

One of the prevalent myths about joyful classrooms is that for students to enjoy learning, it has to be easy, over- or under-structured, gimmicky, or unchallenging. We at Nueva find that the opposite is very ofen true for our learners. How might you build truly challenging, difficult, open-ended learning opportunities for your students that catalyze a love of learning?

25 ©

The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3 Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning

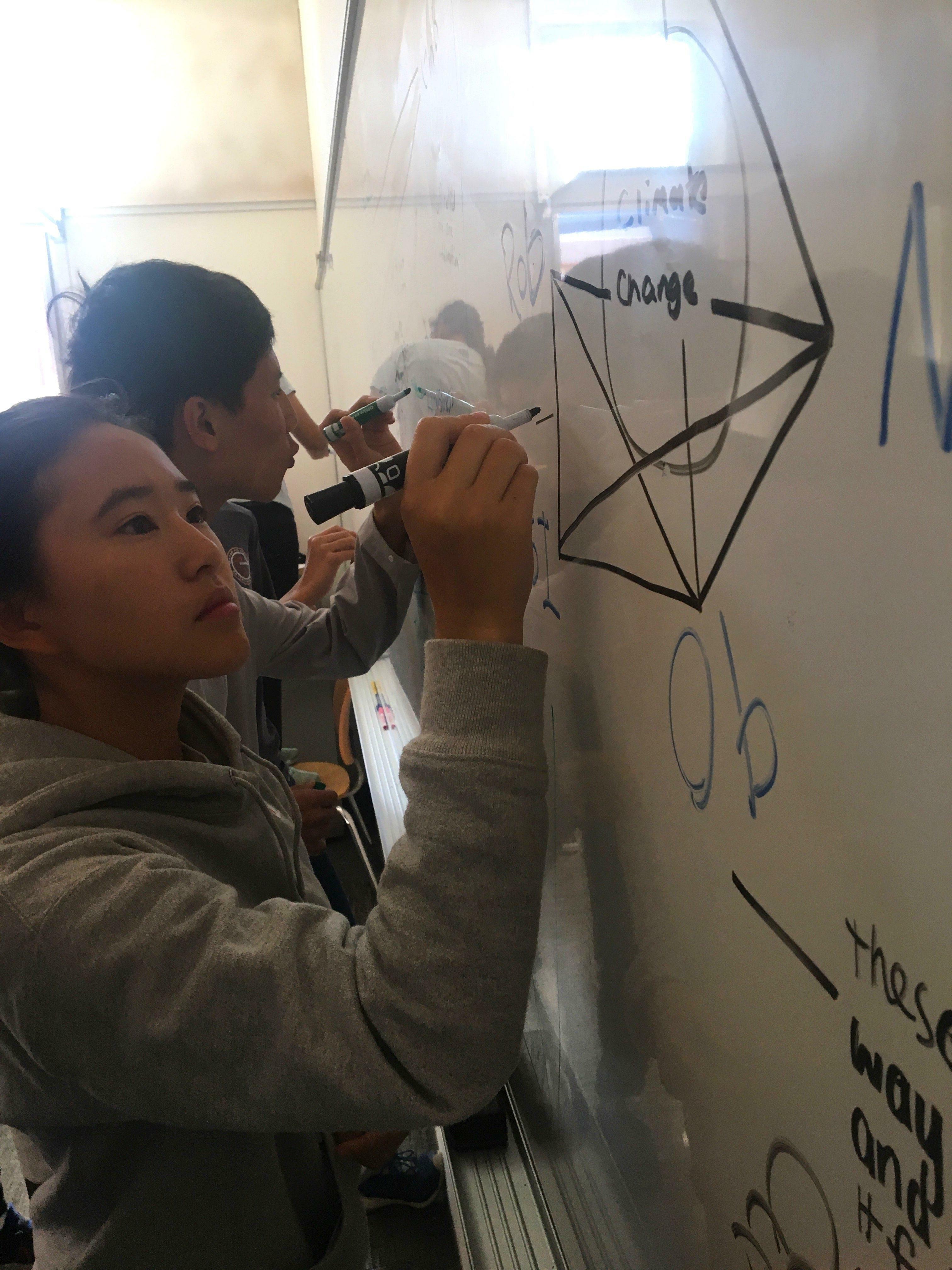

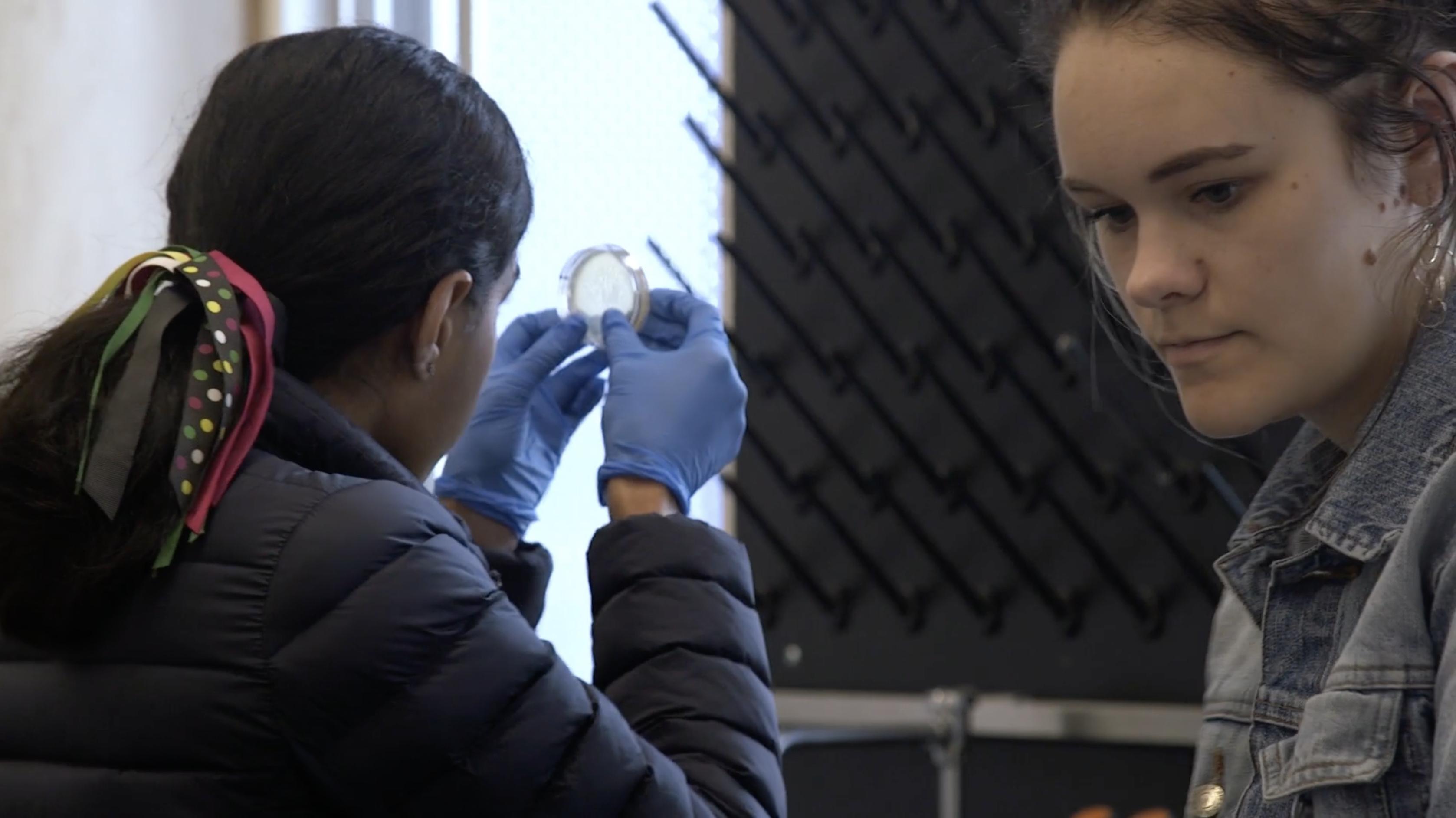

Curating Joy at Nueva

As you look at these examples, consider the multiple ways teachers curate joy and a love of learning in their classes and beyond; how do they blend challenge, learning by doing, open-endedness, and learning as a social activity? How do they allow ownership of their learning and their classroom by the students?

KEY VIDEOS

GingerBread Man

KEY POSTERS

How to Make a Stone Axe

Students in the

To Be Nueva

Excerpt from 2016 speech by faculty & alum

Aron Walker

Aron Walker

"Nueva, I tell people, is like a buffet, with more options and courses than can be sampled. And the learning is like a buffet: if you are used to a sit-down restaurant where waiters come and serve you dishes, and you therefore do not rise to fill your own plate, you still starve…

26

© The Nueva School 2020

Bringing the Silk Road to Nueva WATCH

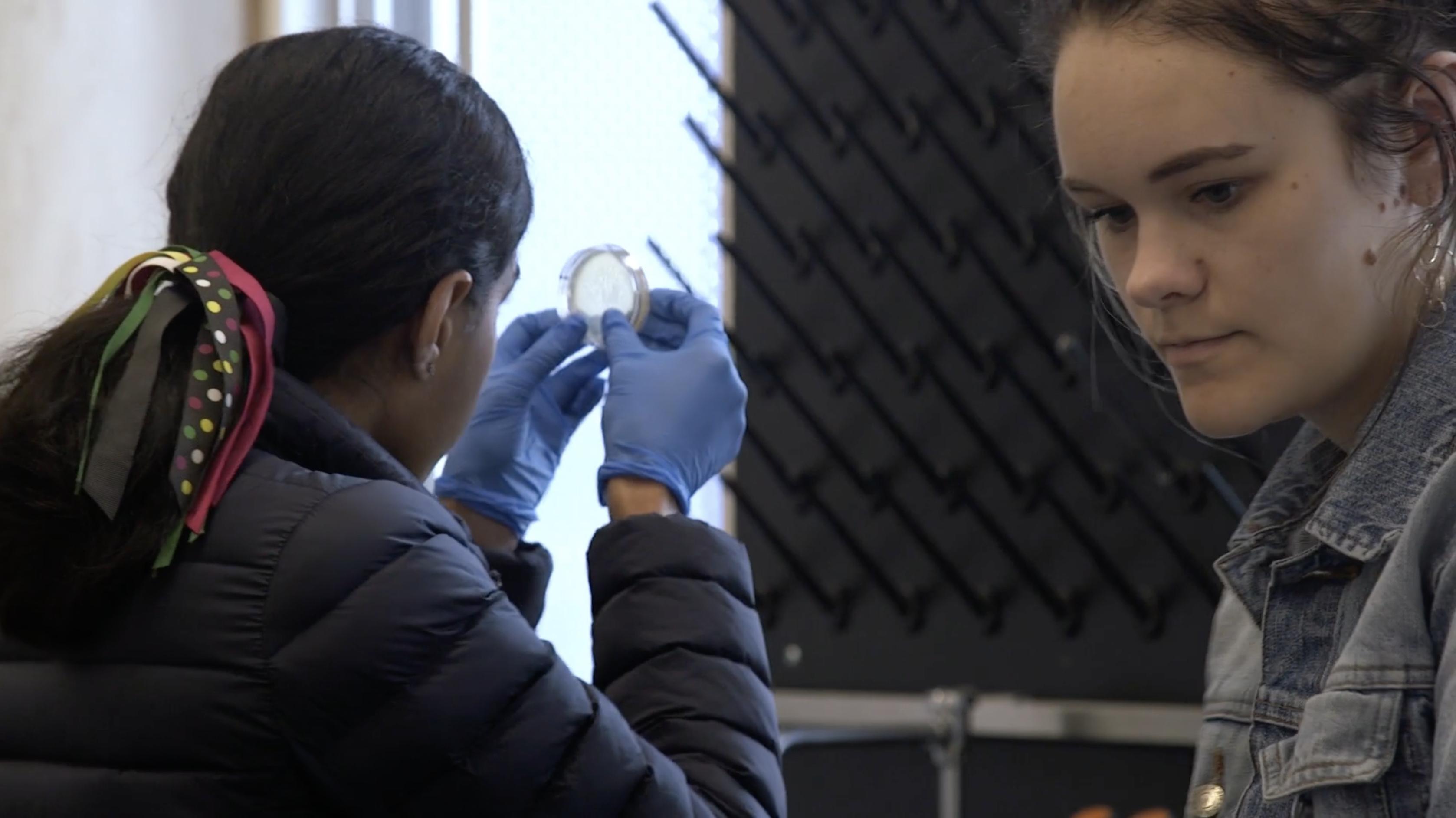

Claire Yeo’s Museum in a Classroom

I-Lab

Mystery VIEW

READ FULL SPEECH

Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning

Drug Design With Francine Learn by Digging

REFLECTION: CURATING JOY AT NUEVA

What did you see in the examples that stood out to you? Are there any themes that arose in your mind when watching?

What catalyzed a love of learning in these various instances?

27 © The Nueva School 2020

1

2 Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning - Curating Joy at Nueva

REFLECTION: REVIEW

What are you wondering afer finishing this unit?

Using your radical imagination, how can you create, for all students, the conditions for a loving environment and a love of learning to flourish?

What is the gap between what you feel you must teach (and how you think you need to teach) and allowing for joy and love of learning to guide your teaching? What have you not felt permission to do? How can you unleash that?

What brings you joy? (For we believe a joyous teacher creates joyous classrooms and joyous staff create a joyous school!)

28 © The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3

3 Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning - Curating Joy at Nueva

ACTIVITY: INTENTION-SETTING

We want to give you explicit permission to prioritize a love of learning in your class or in your role and to embrace conditions that lead to joy. We are an institution that believes in iteration and failing forward. We want you to feel excited to try out new practices, embrace uncertainty, and challenge yourself to grow and explore as an educator. To that end, we encourage you to set some intentions for yourself to pursue in the next 3-6 months. Please use the following prompts to help you do so:

What would you like to create in the coming year, as part of your role, that brings joy and affirms a love of learning? What practice, pedagogy, vision, or exploration have you always wanted to embody and/or try? What would you like to see manifest this year?

What limits you? What do you feel is holding you back? What would you be doing if you felt like you were given permission and opportunity to do so?

What do you need to help you manifest the practices and pedagogy that you explored in the first prompt? What will help you feel joy and possibility this year?

29 © The Nueva School 2020

1 PROMPT 1

2 PROMPT

2

3 PROMPT 3 Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning - Curating Joy at Nueva

Joy in the Remote Classroom at Nueva

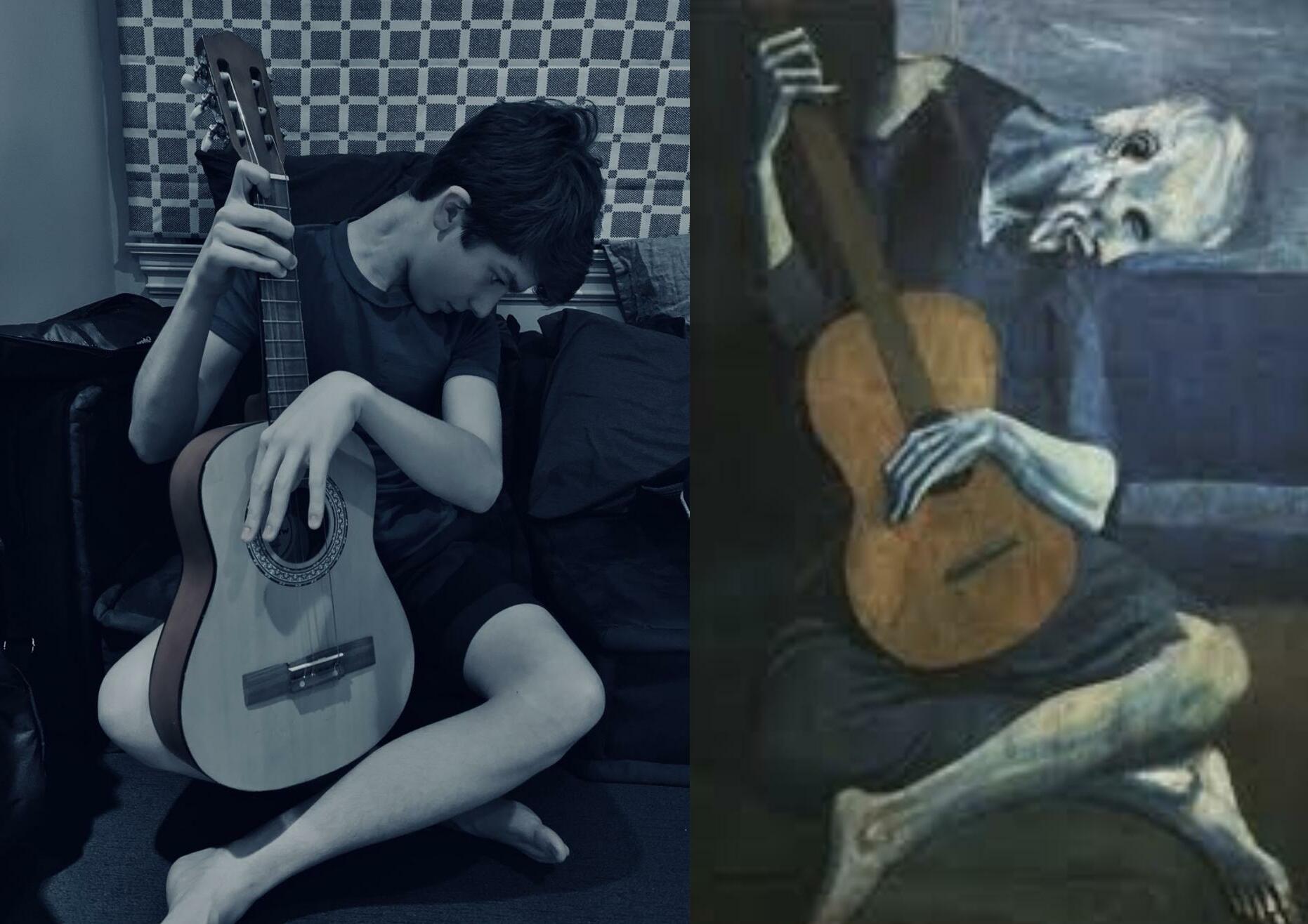

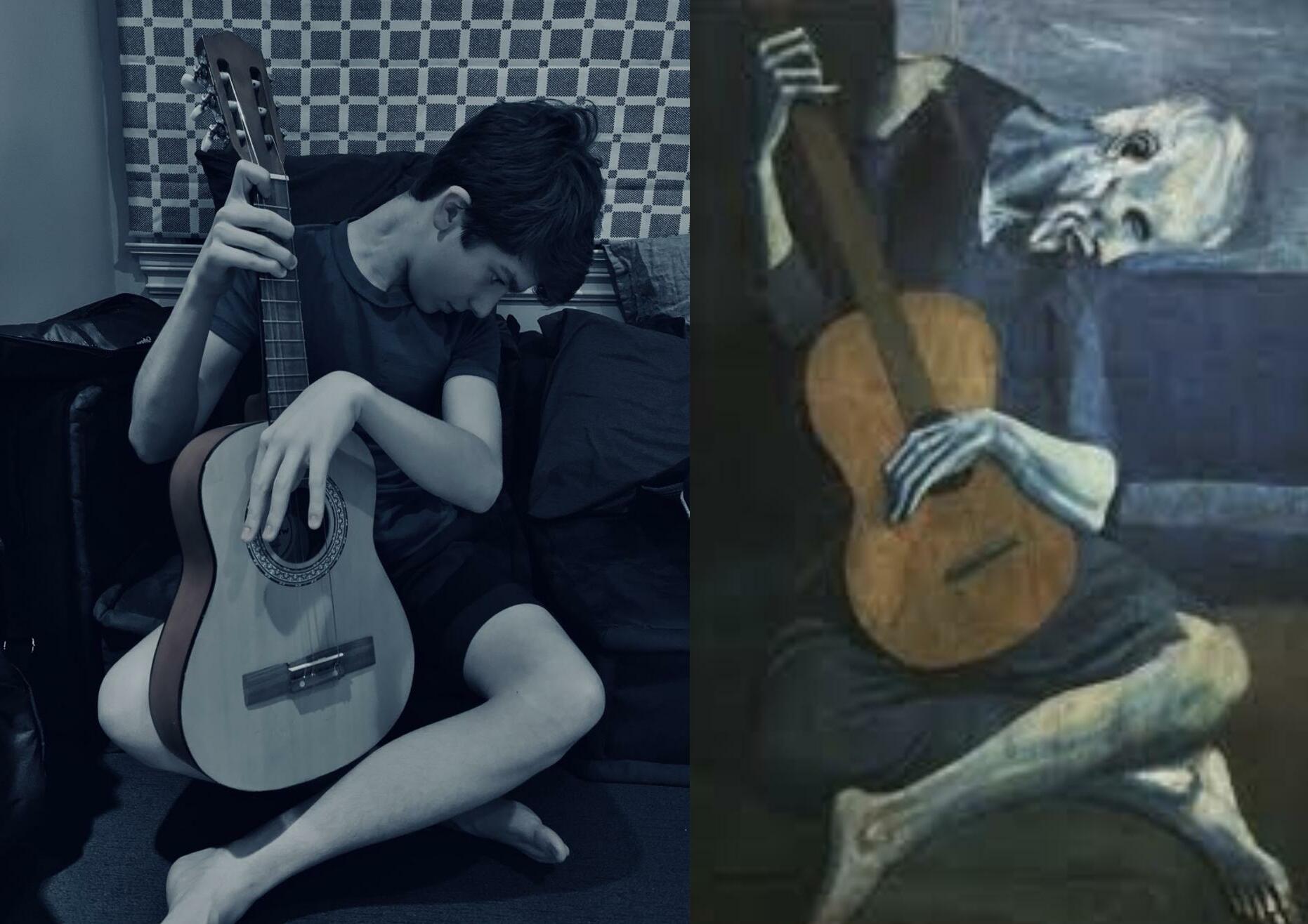

Recreación de Arte

Spanish language students recreated iconic Hispanic works of art using 3 objects they had in their homes

Costume Parties

I-Lab Engineer John Feland surprised his students with a different costume every zoom class.

Principle 2 A Lifelong Love of Learning - Curating Joy at Nueva

A studentcentered school

“We place students at the center of our decision-making and pedagogical design in order to catalyze intellectual, social, and emotional learning and ensure more meaningful, rich, culturally responsive, relevant and effective experiences.”

GETTING STARTED

As lifelong learners ourselves, Nuevans strive to ensure learning is meaningful, engaging and joyful. One way to foster and deepen a love of learning is to keep students at the core of what we do.

3 Principle 3

31 © The Nueva School 2020

REFLECTION: TO BE STUDENT-CENTERED…

What does student-centered pedagogy actually mean? Draw/graph/mind-map a student-centered classroom or a student-centered school.

What was a time you felt you were at the center of your learning?

Describe a practice or approach in schools that is not student-centered.

32

© The Nueva School 2020

1

2

3 Principle 3 A Student-Centered School

Resources on Student-Centered Education

KEY READINGS

The Understanding by Design Framework

The Image of the Child

A Learning Culture with No Ceilings WATCH

Distinctions of Equity

By Zaretta Hammond, as featured in “How to Develop Culturally Responsive

Teaching for Distance Learning”

by Amielle Major

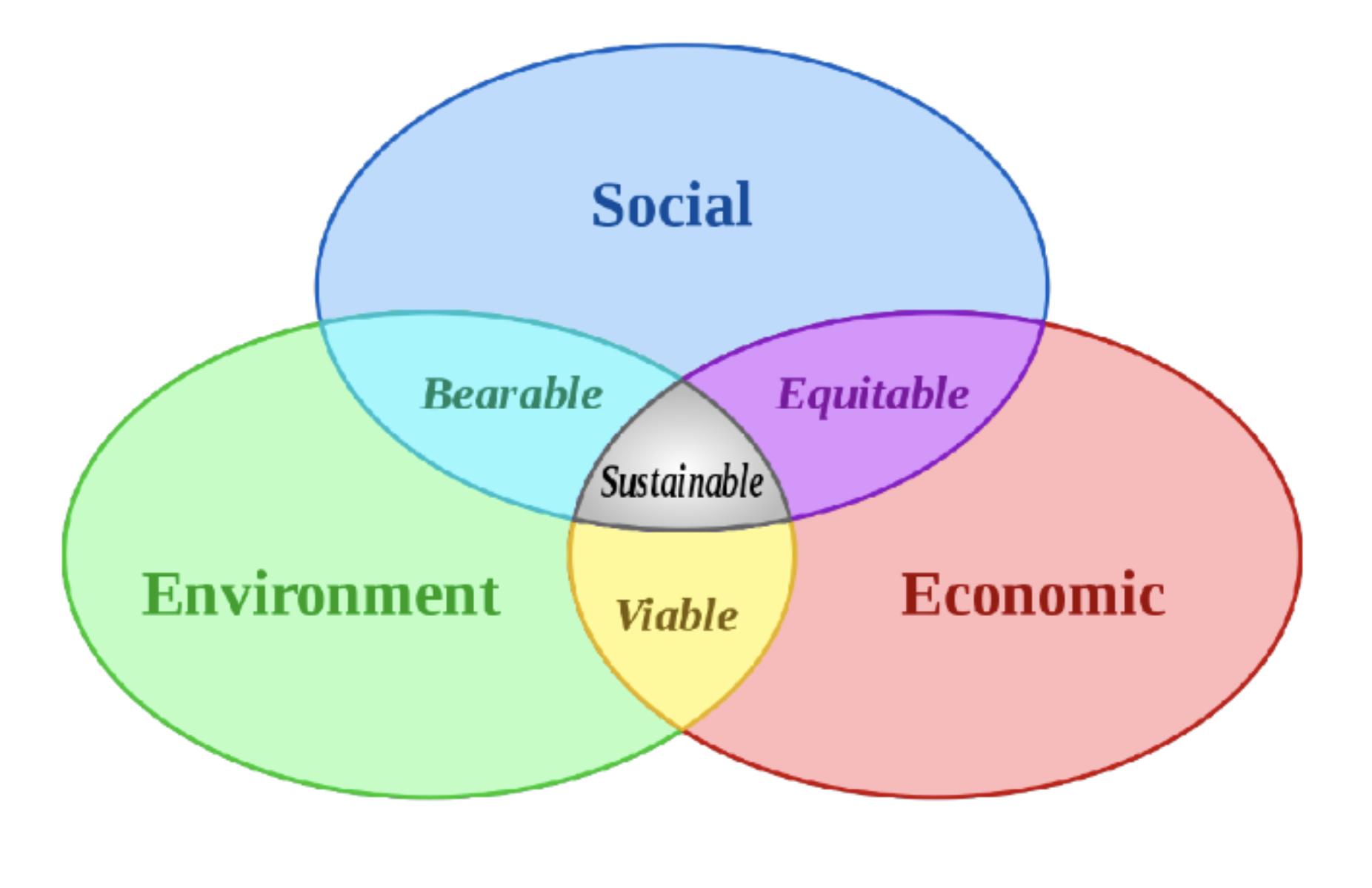

It is important to distinguish between three key areas when engaged in equity work. We often confuse their particular purposes. As a result, we use them interchangeably when they are not. Below is a simple chart to help you understand the distinctions between them. Remember, it is not a continuum. You cannot begin with multicultural education and believe it will lead to culturally responsive instruction. Why? CRT is focused on the cognitive development of under-served students. Multicultural and social justice education have more of a social supporting role.

Multicultural Education

Focuses on celebrating diversity

Centers around creating positive social interactions across differences.

Diversity and inclusion efforts live here.

Concerns itself with exposing privileged students to multiple perspectives, and other cultures. For students of color, the focus is on seeing themselves refected in the curriculum.

Social Justice Education

Focuses on exposing the social political context that students experience.

Centers around raising students’ consciousness about inequity in everyday social, environmental, economic, and political situations.

Anti-racist efforts live here.

Concerns itself with creating a lens to recognize and interrupt inequitable patterns and practices in society.

Social Harmony Critical Consciousness

Culturally Responsive Education

Focuses on improving the learning capacity of diverse students who have been marginalized educationally.

Centers around the affective & cognitive aspects of teaching and learning.

Efforts to accelerate learning live here.

Concerns itself with building cognitive capacity and academic mindset by pushing back on dominant narratives about people of color.

Independent Learning for Agency

33 © The Nueva School 2020

Principle 3 A Student-Centered School

Curriculum begins with parts of the whole. Emphasizes basic skills.

Curriculum emphasizes big concepts, beginning with the whole and expanding to include the parts

Strict adherence to fxed curriculum is highly valued. Pursuit of student questions and interests is valued

Materials are primarily textbooks and workbooks.

Learning is based on repetition.

Teachers disseminate information to students. Students are recipients of knowledge.

Teacher’s role is directive, rooted in authority.

Materials include primary sources of material and manipulative materials

Learning is interactive, building on what the student already knows.

Teachers have a dialogue with students, helping them to construct their own knowledge.

Teacher’s role is interactive, rooted in negotiation.

Assessment is through testing and correct answers. Assessment includes student works, observations and points of view, as well as tests. Process is as important as product.

Knowledge is seen as inert.

Students work primarily alone.

Introduction to Constructivism

Knowledge is seen as dynamic, ever changing with our experiences.

Students work primarily in groups.

By the Center for Educational Innovation at the University at Buffalo

What is constructivism?

Constructivism is the theory that says learners construct knowledge rather than just passively take in information. As people experience the world and reflect upon those experiences, they build their own representations and incorporate new information into their pre-existing knowledge (schemas). Related to this are the processes of assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation refers to the process of taking new information and fitting it into an existing schema.

Accommodation refers to using newly acquired information to revise and redevelop an existing schema.

For example, if I believe that friends are always nice, and meet a new person who is always nice to me, I may call this person a friend, assimilating them into my schema. Perhaps, however, I meet a different person who sometimes pushes me to try harder and is not always nice. I may decide to change my schema to accommodate this person by deciding a friend doesn’t always need to be nice if they have my best interests in mind. Further, this may make me reconsider whether the first person still fits into my friend schema.

Consequences of constructivist theory are that:

‣ Students learn best when engaged in learning experiences rather passively receiving information.

‣ Learning is inherently a social process because it is embedded within a social context as students and teachers work together to build knowledge. Because knowledge cannot be directly imparted to students, the goal of teaching is to provide experiences that facilitate the construction of knowledge.

This last point is worth repeating. A…

More on next page

Traditional Classroom Constructivist Classroom 34 © The Nueva School 2020 Principle 3 A Student-Centered School - Resources

Introduction to Constructivism

(part 2 of 2)

traditional approach to teaching focuses on delivering information to students, yet constructivism argues that you cannot directly impart this information. Only an experience can facilitate students to construct their own knowledge. Therefore, the goal of teaching is to design these experiences.

Consequences for the classroom

There are many consequences for teaching and the classroom if you adhere to constructivist principles. The following chart from the Teaching and Learning Resources wiki compares traditional and constructivist classrooms across several components,

Essential components to constructivist teaching

There are several main components to include if you plan on adhering to constructivist principles in your classroom or when designing your lessons. The following are from Baviskar, Hartle & Whitney (2009):

‣ Elicit prior knowledge

New knowledge is created in relation to learner’s pre-existing knowledge. Lessons, therefore, require eliciting relevant prior knowledge. Activities include: pretests, informal interviews and small group warm-up activities that require recall of prior knowledge.

‣ Create cognitive dissonance

Assign problems and activities that will challenge students. Knowledge is built as learners encounter novel problems and revise existing schemas as they work through the challenging problem.

‣ Apply knowledge with feedback

Encourage students to evaluate new information and modify existing knowledge. Activities should allow for students to compare pre-existing schema to the

novel situation. Activities might include presentations, small group or class discussions, and quizzes.

‣ Reflect on learning

Provide students with an opportunity to show you (and themselves) what they have learned. Activities might include: presentations, reflexive papers or creating a step-by-step tutorial for another student.

Examples of constructivist classroom activities

‣ Reciprocal teaching/learning

Allow pairs of students to teach each other.

‣ Inquiry-based learning (IBL)

Learners pose their own questions and seek answers to their questions via research and direct observation. They present their supporting evidence to answer the questions. They draw connections between their pre-existing knowledge and the knowledge they’ve acquired through the activity. Finally, they draw conclusions, highlight remaining gaps in knowledge and develop plans for future investigations.

‣ Problem-based learning (PBL)

The main idea of PBL is similar to IBL: learners acquire knowledge by devising a solution to a problem. PBL differs from IBL in that PBL activities provide students with real-world problems that require students to work together to devise a solution. As the group works through the challenging real-world problem, learners acquire communication and collaboration skills in addition to knowledge.

‣ Cooperative learning

Students work together in small groups to maximize their own and each other's learning. Cooperative learning differs from typical group work in that it requires interdependence among group members to solve a problem or complete an assignment.

© The Nueva School 2020

35

Principle 3 A Student-Centered School - Resources

Differentiated Instruction: a Primer

By Sarah D. Sparks

How can a teacher keep a reading class of 25 on the same page when four students have dyslexia, three students are learning English as a second language, two others read three grade levels ahead, and the rest have widely disparate interests and degrees of enthusiasm about reading?

What is Differentiated Instruction?

“Differentiated instruction”—the process of identifying students’ individual learning strengths, needs, and interests and adapting lessons to match them—has become a popular approach to helping diverse students learn together. But the field of education is filled with varied and often conflicting definitions of what the practice looks like, and critics argue it requires too much training and additional work for teachers to be implemented consistently and effectively.

Differentiation has much in common with many other instructional models: It has been compared to response-to-intervention models, as teachers vary their approach to the same material with different students in the same classroom; data-driven instruction, as individual students are frequently assessed or otherwise monitored, with instruction tweaked in response; and scaffolding, as assignments are intended to be structured to help students of different ability and interest levels meet the same goals.

Federal education laws and regulations do not generally set out requirements for how schools and teachers should “differentiate” instruction. However, in its 2010 National Education Technology Plan,

the U.S. Department of Education lays out a framework that places differentiated teaching under the larger umbrella of “personalized learning,” instruction tailored to students’ individual learning needs, preferences, and interests. This framework assumes that all students in a heterogeneous classroom will have the same learning goals, but:

‣ “Individualization” tailors instruction by time. A teacher may break the material into smaller steps and allow students to master these steps at different paces; skipping topics they can prove they have mastered, while getting more help on those that prove difficult. This model has been used in iterations as far back as the late Robert Glaser’s Individually Prescribed Instruction in the 1970s, an approach which pairs diagnostic tests with objectives for mastery that is intended to help students progress through material at their own pace.

‣ “Differentiation” tailors instruction by presentation. A teacher may vary the method and assignments covering the material to adjust to students’ strengths, needs, and interests. For example, a teacher may allow an introverted student to write an essay on a historical topic while a more outgoing student gives an oral presentation on the same subject.

That distinction is accepted by some, though far from all, in the field.

The ambiguity has led to widespread confusion and debate over what differentiated instruction looks like in

practice, and how its effectiveness can be evaluated.

For example, a 2005 study for the National Research Center on Gifted and Talented, which tracked implementation of “differentiation” over three years, found that the “vast majority” of teachers never moved beyond traditional direct lectures and seat work for students.

“Results suggest that differentiation of instruction and assessment are complex endeavors requiring extended time and concentrated effort to master,” the authors conclude. “Add to this complexity current realities of school such as large class sizes, limited resource materials, lack of planning time, lack of structures in place to allow collaboration with colleagues, and ever-increasing numbers of teacher responsibilities, and the tasks become even more daunting.”

Evolution of the Concept

Differentiated instruction as a concept evolved in part from instructional methods advocated for gifted students and in part as an alternative to academic “tracking,” or separating students of different ability levels into groups or classes. In the 1983 book, Individual Differences and the Common Curriculum, Thomas S. Popkewitz discusses differentiation in the context of “Individually Guided Education, … a management plan for pacing children through a standardized, objective-based curriculum” that would include smallgroup work, team teaching, objectivebased testing, and monitoring of student progress. …

36 ©

The Nueva School 2020

More on next page

Principle 3 A Student-Centered School - Resources

Differentiated Instruction: A Primer

(part 2 of 3)

…Carol Ann Tomlinson, a co-director of the Institutes on Academic Diversity at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, and the author of The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, 2nd Edition (ASCD, 2014) and Assessment and Student Success in a Differentiated Classroom (ASCD, 2013) argues that differentiation is, at its base, not an approach but a basic tenet of good instruction, in which a teacher develops relationships with his or her students and presents materials and assignments in ways that respond to the student’s interests and needs.

Differentiated Instruction Strategies

In theory—though critics allege not in practice—differentiation does not involve creating separate lesson plans for individual students for a given unit.

Ms. Tomlinson argues that differentiation requires more than creating options for assignments or presenting content both graphically and with hands-on projects, for example. Rather, to differentiate a unit on Rome, a teacher might consider both specific terms and overarching themes and concepts she wants students to learn, and offer a series of individual and group assignments of various levels of complexity to build those concepts and allow students to demonstrate their understanding in multiple ways, such as journal entries, oral presentations, creating costumes, and so on. In different parts of a unit students may be working with students who share their interests or have different ones, and with students who are at the same or different ability levels.

During the 1990s, teachers were also encouraged to present material differently according to a student’s “learning style”—for example, visual, auditory, or kinesthetic. But while there

have been studies that show students remember more when the same material is presented and reinforced in multiple ways, recent research reviews have found no evidence that individual students can be categorized as learning best through a single type of presentation.

Rick Wormeli, an education consultant and the author of Fair Isn’t Always Equal: Assessment and Grading in the Differentiated Classroom, instead suggests in a 2011 essay in the journal Middle Ground that teachers differentiate based on “learner profiles”:

“A learner profile is a set of observations about a student that includes any factor that affects his or her learning, including family dynamics, transiency rate, physical health, emotional health, comfort with technology, leadership qualities, personal interests, and so much more.”

Impacts of Technology

Differentiated and personalized instructional models have also evolved with technological advances, which make it easier to develop and monitor education plans for dozens of students at the same time. The influence of differentiation on school-level programs can be seen in “early warning systems” and student “dashboards” that aim to track individual student performance in real time, as well as initiatives in some schools to develop and monitor individualized learning plans with the student, his or her teachers, and parents.

Advocates of hybrid education models, such as the “flipped classroom”—in which students watch lectures and read material at home and perform practice that would normally be homework during class time—have suggested this could help teachers

differentiate by recording and archiving different lectures that students could watch and rewatch as needed, and providing more one-on-one time during class.

Professional Development

By any account, differentiation is considered a complex approach to implement, requiring extensive and ongoing professional development for teachers and administrators.

In the 2005 longitudinal study that found no consistent implementation of differentiation, researchers noted that “many aspects of differentiation of instruction and assessment (e.g., assigning different work to different students, promoting greater student independence in the classroom) challenged teachers’ beliefs about fairness, about equity, and about how classrooms should be organized to allow students to learn most effectively. As a result, for most teachers, learning to differentiate entailed more than simply learning new practices. It required teachers to confront and dismantle their existing, persistent beliefs about teaching and learning, beliefs that were in large part shared and reinforced by other teachers, principals, parents, the community, and even students.”

In the 2009 book, Professional Development for Differentiating Instruction, Cindy A. Strickland notes that most schools do not provide sufficient training for new and experienced teachers in differentiating instruction.

Ms. Tomlinson said that teachers can begin to differentiate instruction simply by learning more about their students and trying to tailor their teaching as much as they find feasible. “Every…

More on next page

37

© The Nueva School 2020

Principle 3 A Student-Centered School - Resources

Differentiated Instruction: A Primer

(part 3 of 3)

…significant endeavor seems too hard if we look only at the expert’s product. The success of all these ‘seasoned’ people stemmed largely from three factors: They started down a path. They wanted to do better. They kept working toward their goal.”

Including students of disparate abilities and interests also requires the teacher to rethink expectations for all students: “If a teacher uses flexible grouping lesson by lesson and does not assume a student has prior knowledge because he is a 'higher' student but really assesses and groups, based on need sometimes and other times by interest, the students will get what they need,” Melinda L. Fattig, a nationally recognized educator and a co-author of the 2008 book Co-Teaching in the Differentiated Classroom, told Teacher magazine that year.

Critiques

In practice, differentiation is such a broad and multifaceted approach that it has proven difficult to implement properly or study empirically, critics say.

In a 2010 report by the research group McREL, author Bryan Goodwin notes that “to date, no empirical evidence exists to confirm that the total package (e.g., conducting ongoing assessments of student abilities, identifying appropriate content based on those abilities, using flexible grouping arrangements for students, and varying how students can demonstrate proficiency in their learning) has a positive impact on student achievement.” He adds: “One reason for this lack of evidence may simply be that no large-scale, scientific study of differentiated instruction has been conducted.” However, Mr. Goodwin pointed to the 2009 book Visible Learning, which synthesized studies of more than 600 models of personalizing learning based on student interests and prior performance, and

found them not much better than general classroom instruction for improving students’ academic performance.

Both in planning time and instructional time, differentiation takes longer than using a single lesson plan for a given topic, and many teachers attempting to differentiate have reported feeling overwhelmed and unable to reach each student equally.

In a 2010 Education Week Commentary essay, Michael J. Schmoker, the author of the 2006 book, Results NOW: How We Can Achieve Unprecedented Improvements in Teaching and Learning, says attempts to differentiate instruction frustrated teachers and “seemed to complicate teachers’ work, requiring them to procure and assemble multiple sets of materials” leading to “dumbed-down” teaching.

Likewise, some advocates of gifted education, such as James R. Delisle, have argued that advanced students still are not challenged enough in a differentiated environment, which may vary in the presentation of material but not necessarily in the pace of instruction. He argues that “differentiation in practice is harder to implement in a heterogeneous classroom than it is to juggle with one arm tied behind your back.”

“There is no one book, video, presenter, or website that will show everyone how to differentiate instruction. Let’s stop looking for it. One size rarely fits all. Our classrooms are too diverse and our communities too important for such simplistic notions,” Mr. Wormeli said in an interview with Education Week blogger Larry Ferlazzo.

“Instead, let’s realize what differentiation really is: highly effective teaching, which is complex and interwoven; no one element defining it.”

38

© The Nueva School 2020

Principle 3 A Student-Centered School - Resources

How To Develop Culturally Responsive Teaching for Distance Learning

By Amielle Major

Te coronavirus pandemic and school closures across the nation have exposed deep inequities within education: technology access, challenges with communication, lack of support for special education students, to name just a few. During this crisis, there are still opportunities to provide students with tools to help them be independent learners, according to Zaretta