King of Hearts

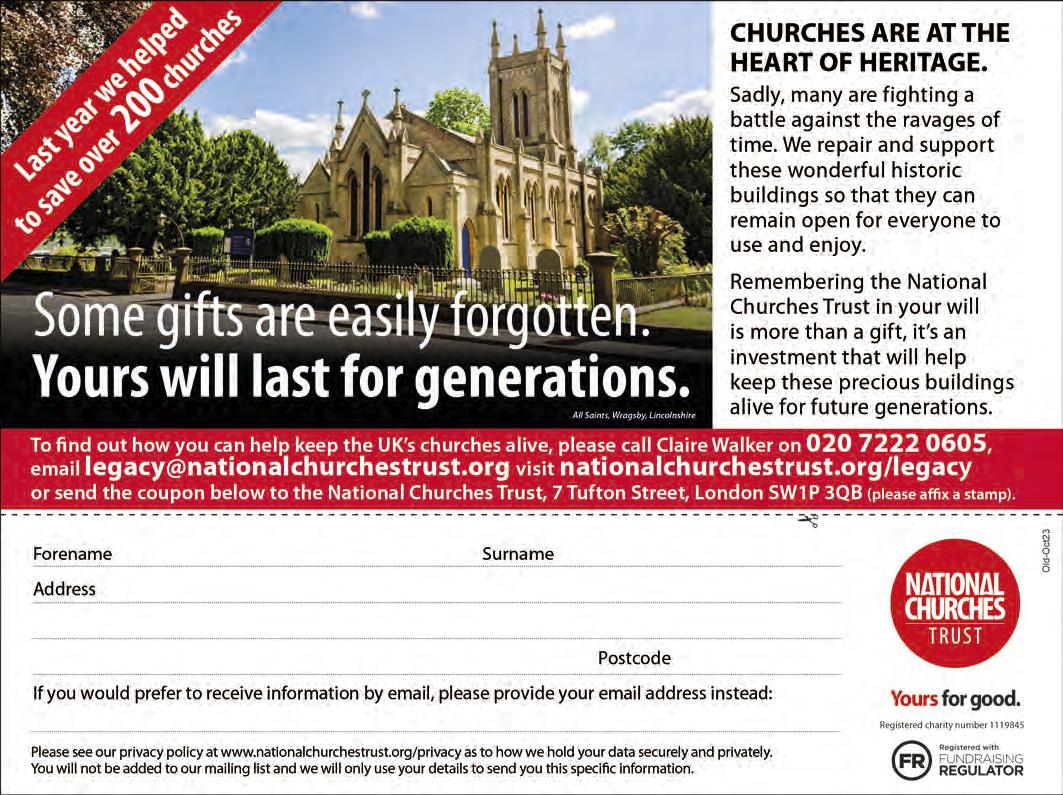

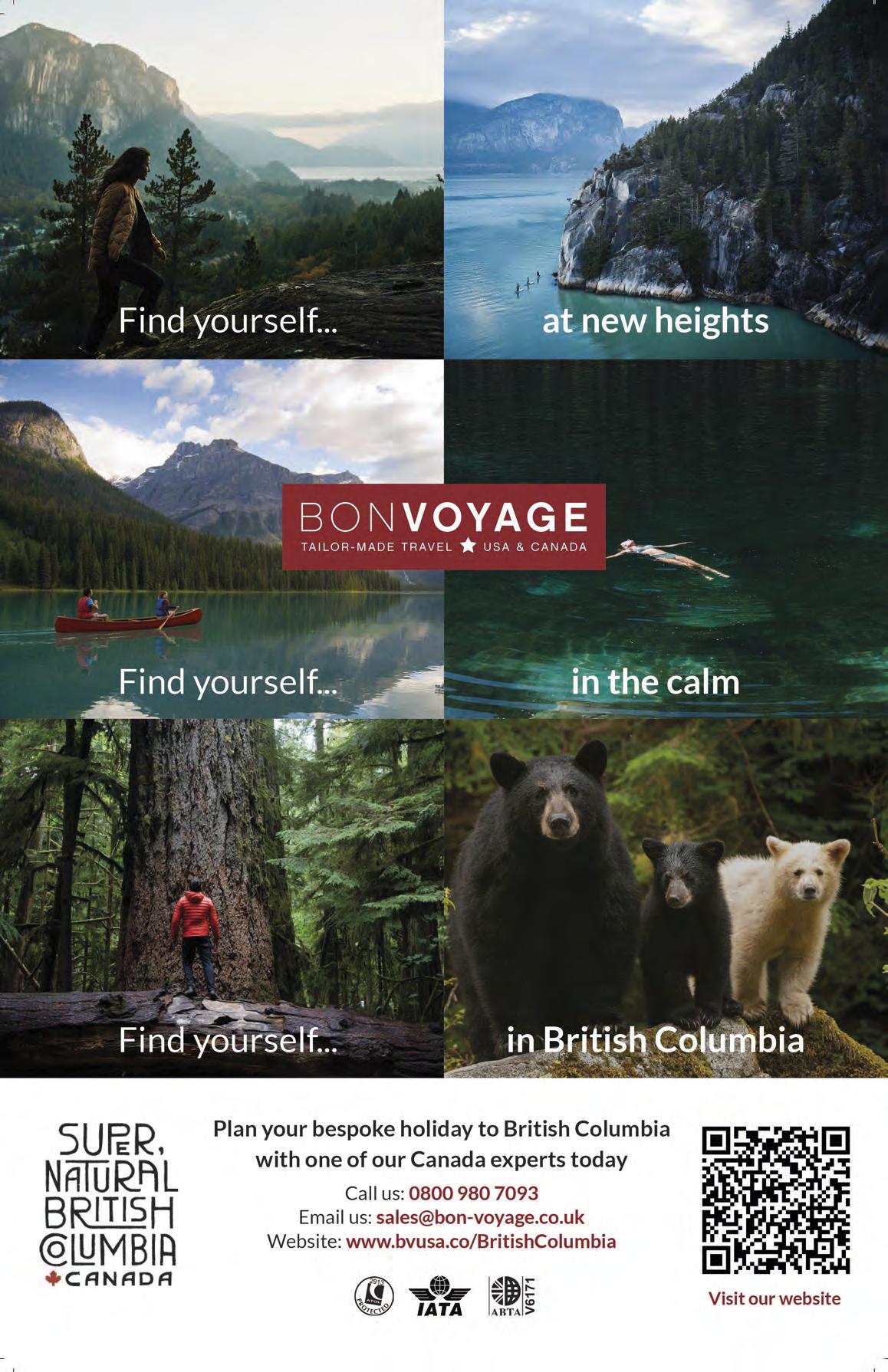

Richard Harris – Madeline Smith

Joy of

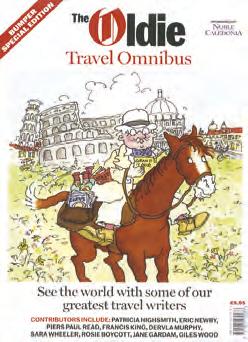

October 2023 | £5.25 £4.13 to subscribers | www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 431 32-PAGE OLDIE REVIEW OF BOOKS ‘The Oldie is an incredible magazine – perhaps the best magazine in the world’ Graydon Carter GILES WOOD WHY I HATE STAYING WITH PEOPLE

Brutalism – Jonathan Meades I was Twiggy’s ghost-writer – Valerie Grove John le Carré’s debt to Ian Fleming – Nicholas Shakespeare The charm of

Features

I ghosted Twiggy's memoir page 29

World's

Books

54 Modern Buildings in London, by Ian Nairn

Jonathan Meades

55 Emperor of Rome, by Mary Beard

Daisy Dunn

57 Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire, by Michael Palin

Roger Lewis

59 The Savage Storm: The Battle for Italy 1943, by James Holland

Alan Judd

61 Albrecht Dürer: Art and Autobiography, by David Eskerdjian

Alexander Hope

63 The Fraud, by Zadie Smith

David Horspool

Arts

66 Film: The Miracle Club

Pursuits

73 Gardening David Wheeler

73 Kitchen Garden Simon Courtauld

74 Cookery Elisabeth Luard

74 Restaurants James Pembroke

75 Drink Bill Knott

76 Sport Jim White

76 Motoring Alan Judd

78 Digital Life Matthew Webster

78 Money Matters

Margaret Dibben

81 Bird of the Month: Redshank John McEwen

Travel

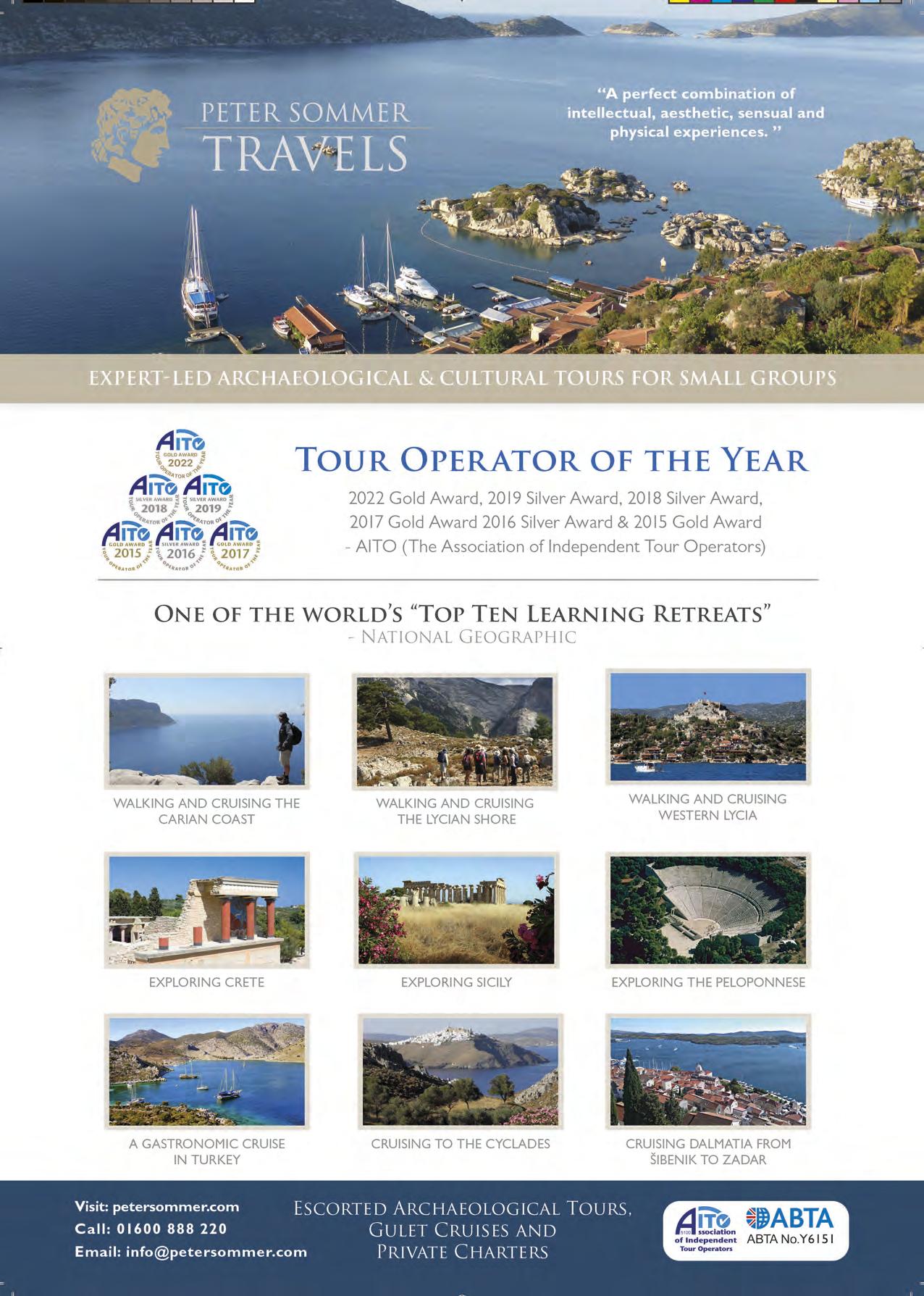

82 High Art in Low Countries William Cook

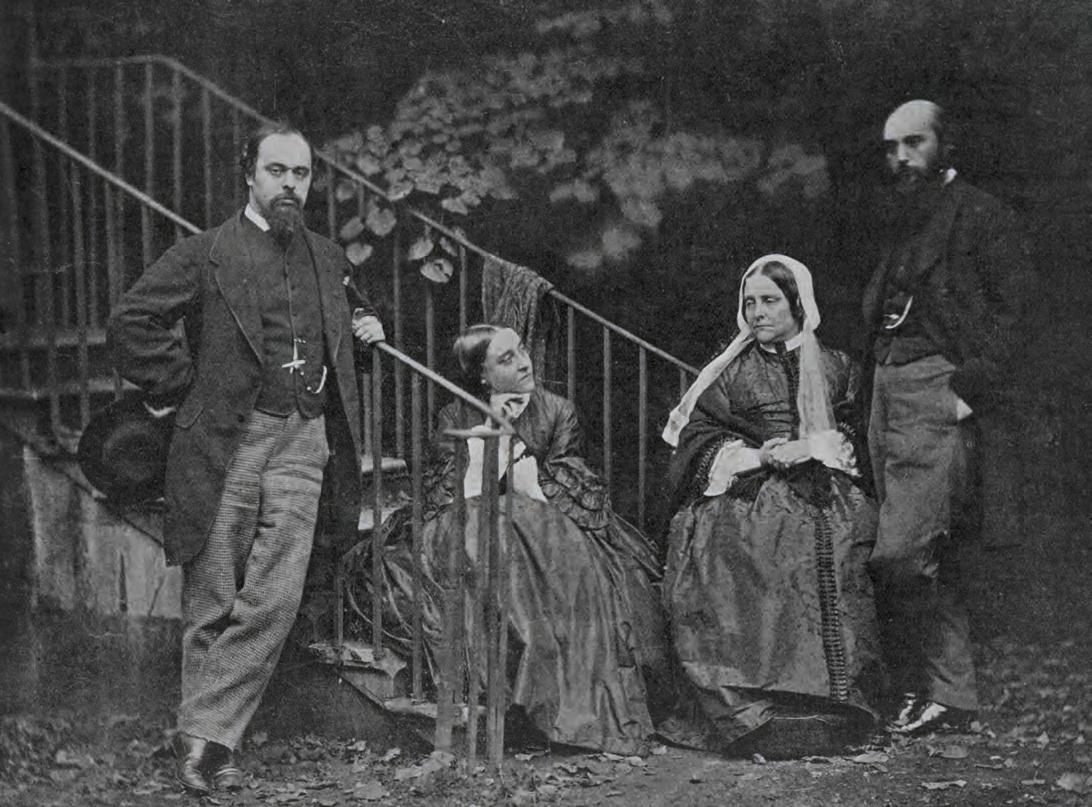

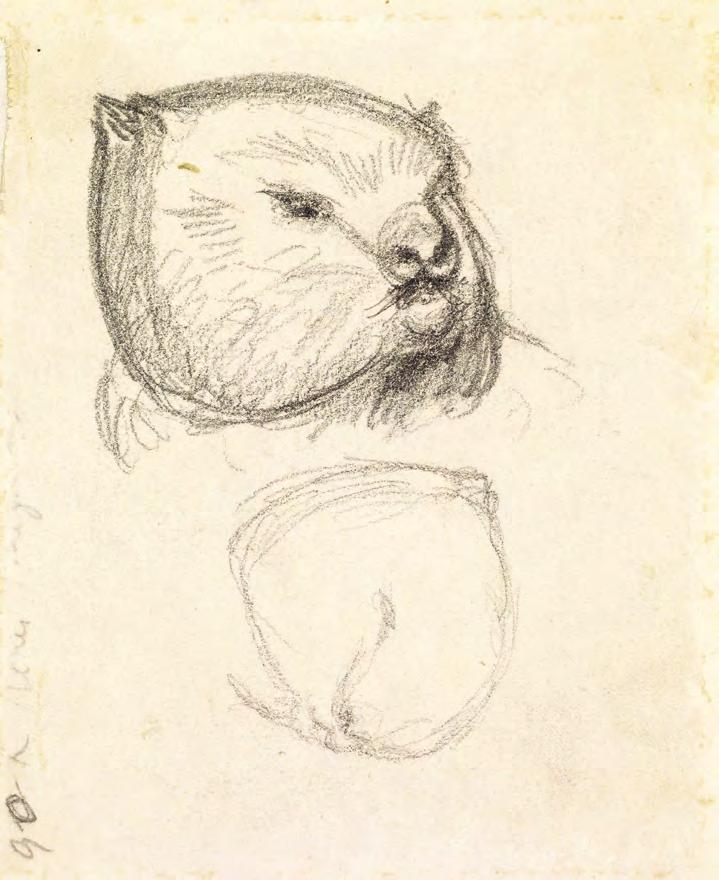

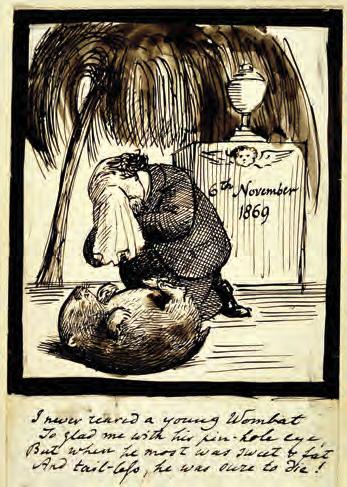

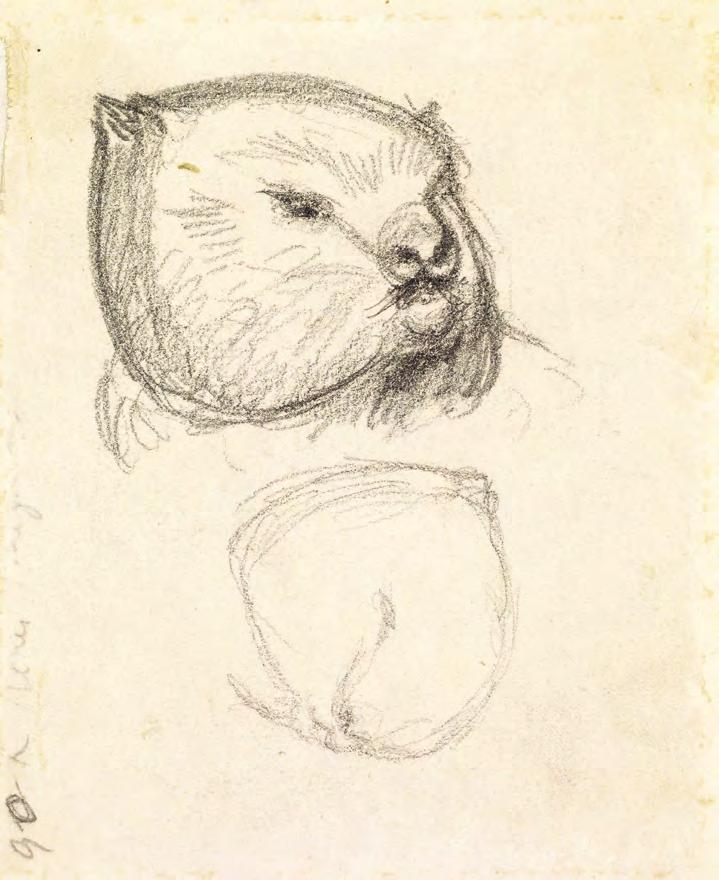

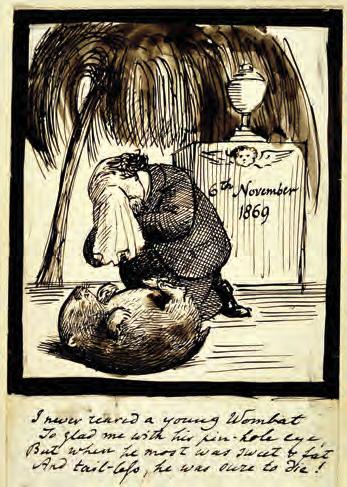

84 Overlooked Britain: Rossetti’s wombat

Lucinda Lambton

86 On the Road: Annabel Croft

Regulars

Harry Mount

67 Theatre:As You Like It

William Cook

67 Radio Valerie Grove

68 Television Frances Wilson

69 Music Richard Osborne

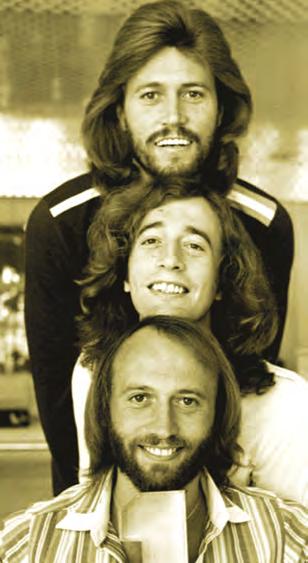

70 Golden Oldies

Rachel Johnson

Louise Flind

87 Taking a Walk: Blenheim woods

Patrick Barkham

The Oldie literary lunch p35 Reader trip p79

Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk

Editor Harry Mount

Sub-editor Penny Phillips

Art editor Jonathan Anstee

Supplements editor Jane Mays

Editorial assistant Amelia Milne

Publisher James Pembroke

Patron saints Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

At large Richard Beatty

Our Old Master David Kowitz

Oldie subscriptions

71 Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu Moray

To order a print subscription, go to www.subscription.co.uk/oldie/offers, or email theoldie@subscription.co.uk, or call 01858 438791, or write to The Oldie, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF.

Print subscription rates for 12 issues: UK £49.50; Europe/Eire £58; USA/Canada £70; rest of world £69.

To buy a digital subscription for £29.99 or single issue for £2.99, go to the App Store on your tablet/mobile and search for ‘The Oldie’.

Advertising

For display, contact : Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Jasper Gibbons on 020 3859 7096

For classified: Monty Martin-Zakheim on 020 3859 7093

The Oldie October 2023 3

14 My invitation to Camelot Madeline Smith 16 Bond's influence on Smiley Nicholas Shakespeare 18 Jobs for the girls Ysenda Maxtone Graham 20 My interview Hell Griff Rhys Jones 23 Antonia Fraser on her uncle, Anthony Powell Harry Mount 26 Euan Myles, British Atlas 29 Ghosting Twiggy Valerie Grove 30 Life on the Cornish edge Sasha Swire 32 Salerno, 80 years on Richard Oldfield 34 LBC turns 50 Duncan Campbell 35 In love with nostalgia Jon Askew

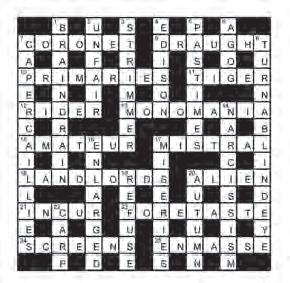

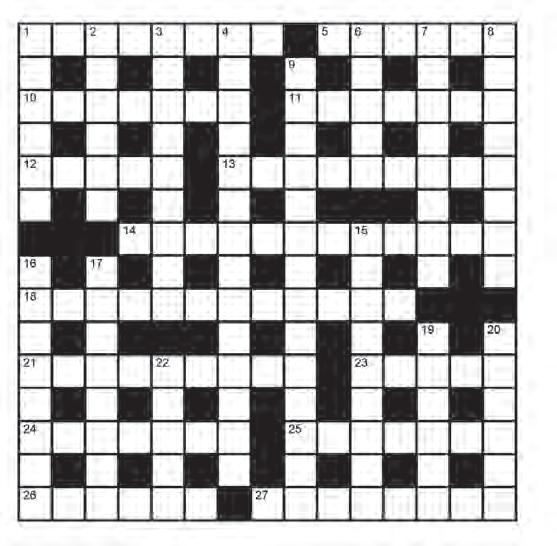

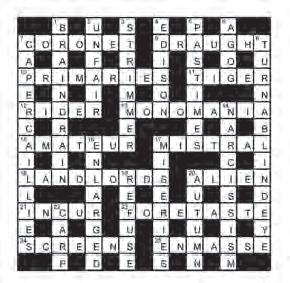

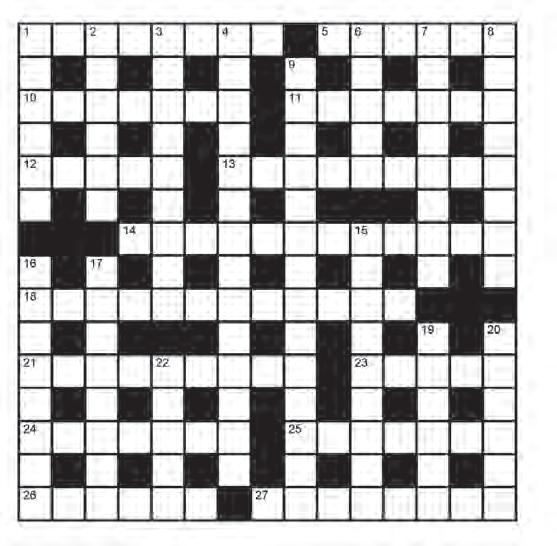

5 The Old Un’s Notes 9 Gyles Brandreth’s Diary 11 Grumpy Oldie Man Matthew Norman 12 Olden Life Sonia Zhuravlyova 12 Modern Life Charlotte Metcalf 37 Oldie Man of Letters A N Wilson 38 History David Horspool 40 Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson 41 Country Mouse Giles Wood 42 Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny 44 Mary Killen’s Beauty Tips 45 Small World Jem Clarke 47 School Days Sophia Waugh 48 God Sister Teresa 48 Memorial Service: Tom Stacey James Hughes-Onslow 49 The Doctor’s Surgery Dr Theodore Dalrymple 50 Readers’ Letters 52 I Once Met… Donald Sinden Robert Portal 52 Memory Lane Roy Collins 65 Commonplace Corner 65 Rant: Reading texts on TV Matthew Webster 89 Crossword 91 Bridge Andrew Robson 91 Competition Tessa Castro 98 Ask Virginia Ironside

House, 23/31

cover ALAMY

News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk Front

ABC circulation figure July-December 2021: 48,249 Subs Emailqueries? co.uksubscription.theoldie@ or 01858phone 438791

best globe-maker page 26

when you subscribe – and get two free books

page 21

Save

See

14

In Camelot with Richard Harris page

Reader Offers

The Old Un’s Notes

IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT FOR SUBSCRIBERS

As you may know, we recently moved to a new subscriptions service provider, CDS Global, in order to provide you with a better service. CDS Global looks after hundreds of well-known publications and, now, The Oldie.

If you subscribe via direct debit, we will be writing to you via post or email to ask you to sign a new direct debit mandate because your old direct debit mandate had to be cancelled due to the move to the new subscription house. We are sorry for the inconvenience but signing up will only take you a few minutes.

Don’t worry: we won’t actually take payment until ten days before your next subscription term starts. So you can update your direct debit and save money, even if your current term expires well into 2024.

You can update your direct debit for your next term either by going online using the URLs below or calling 01858 438 791.

You will need your customer number, which can be found above your name and address on the magazine’s envelope.

PRINT-ONLY

For print-only renewals, please go to: checkout.theoldie.co.uk/ Renewal/NOLDMG23

DIGITAL-ONLY

For digital-only renewals, please go to: checkout.theoldie.co.uk/ Renewal/NOE1MG23

PRINT AND DIGITAL

For print and digital renewals, please go to: checkout.theoldie. co.uk/Renewal/NOBDMG23

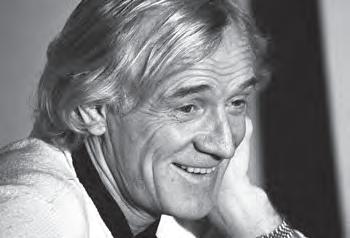

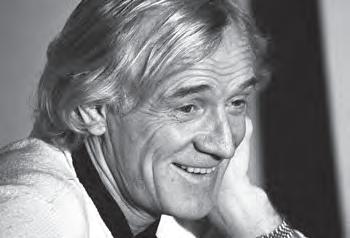

Peter Vaughan, best known for starring in the 1970s TV sitcom Porridge, was born 100 years ago this year.

His character ‘Grouty’ –the criminal Mr Big in the fictional prison HMP Slade who was menacing in an Ealing comedy sort of way –became one of the show’s best-known supporting characters, even though he only appeared in a handful of episodes.

Interviewing the great man – who later played Mr Stevens Sr. in Remains of the Day – had its challenges. So Oldie contributor York Membery discovered when he spoke to him at his home in Sussex for a national newspaper several months before his death in December 2016, aged 93.

‘My editor wanted me to quiz him about all things “Grouty” but Porridge was

the last thing he wanted to discuss,’ recalls Membery.

‘Having worked as a character actor since the late 1950s, he regarded Porridge as a minor episode in his career. He made only passing reference to it in his memoir.

‘So when it became apparent that the two of us were at cross-purposes, I was politely shown the door.’

But Membery has no hard feelings. ‘Porridge just wouldn’t have been the same without Grouty,’ he observes.

Japan’s demographics are posing some acute problems for the nation, not least because it has the world’s second-highest proportion of people aged 65 and over.

Dementia is predicted to affect one in five people there by 2025 – and with this debilitating condition can come acute loneliness and discrimination.

But a recent innovative social experiment has caught the attention of Japan and the world. It’s called the ‘Restaurant of Mistaken Orders’ – a dining spot in Tokyo staffed by waiters and waitresses with some degree of cognitive impairment.

The idea for starting this restaurant came to TV presenter Shiro Oguni when he worked on a story about dementia: ‘Like everybody else, my awareness of it at first tended towards negative images of people who were radically forgetful,’ he says. ‘But, actually,

The Oldie October 2023 5

MOVIESTORE COLLECTION LTD / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Grouty, King of Slade Prison: Peter Vaughan (1923-2016)

Important

stories

you may have missed

Boyfriend threw a remote control at television Dundee Courier & Advertiser

they can cook, clean and do other “normal” things for themselves.’

For Oguni, the restaurant is an opportunity to think about how kindness can take root in society. Although orders do sometimes go wildly astray, diners are generally extremely happy with their experience.

‘Dementia is not what a person is, but just part of who they are,’ says Oguni. ‘People are people. The change will not come from them. It must come from society. By cultivating tolerance, almost anything can be solved.’

Parish council won’t pay £2k to keep toilets open The Journal (formerly known as The Newcastle Journal)

Farm gate goes viral Western Telegraph, Pembrokeshire

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The November issue is on sale on 18th October 2023.

GET THE OLDIE APP

Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

OLDIE BOOKS

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE

Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

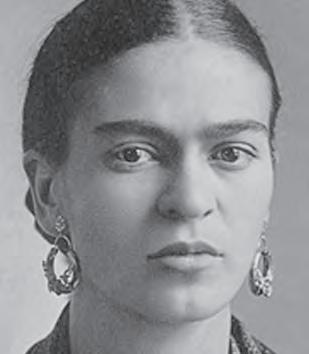

Newspaper obituaries of the South African journalist Jani Allan reheated her unsuccessful 1992 libel case against Channel 4, which had accused her of an affair with the Afrikaaner rabblerouser Eugene Terreblanche.

The obits reprised such

details as her flatmate’s claim to have peered through a keyhole and seen Terreblanche’s white bottom bouncing up and down on top of the willowy Allan.

What they did not report was an unlikely friendship Allan later established with one of Fleet Street’s most observant Roman Catholics, David Twiston-Davies, letters editor of the Daily Telegraph.

The late ‘Twisters’ was a short, loud character with a taut pot belly and purple snout. Always ready to listen to an underdog and always open to the forgiveness of sin, he invited Allan to submit letters for publication.

This necessitated long lunches in London’s clubland, or those parts of it that admitted women. Twisters and Jani became an unlikely (Platonic) couple, she still wonderfully glamorous and leggy, with Farah Fawcett hair

and a drawling Sarf African accent, while Twisters, a good foot shorter than her yet twice her circumference, bawled forth in an accent that was part-Downside, partNewfoundland, about saints, monsignors, Lord Longford and the Tridentine mass.

Jani, returning to the Telegraph offices with Twisters after one such lunch, was haloed with smiles. It was almost as if she loved old Twisters. And we can be absolutely certain that he never laid a finger on her.

The Oldie salutes the memory of Sir Robin Day, whose 100th birthday would have fallen on 24th October 2023.

Whatever else you can say about the Grand Inquisitor – the title Day gave his autobiography – he transformed the art of the current-affairs

‘Sod it! The bastards are on strike!’

6 The Oldie October 2023

Lady in red: Jani Allan

‘He doesn’t chase me as much as he used to’

interview. In the pre-Day era, journalists tended to ask questions such as ‘Excuse me, Prime Minister, but might you favour us with your impressions of the recent talks in Washington?’

Afterwards came the attack-dog approach that dominates the airwaves today.

The son of a post-office official, Day served in the Royal Artillery before going up to Oxford, where he was President of the Union.

He joined the staff of ITN in 1955, but it was his long tenure at the BBC, where he presented both Panorama and Question Time, that made him a household name.

Day’s trademark heavyrimmed glasses and bow tie became the stuff of caricature, most of it affectionate.

Some of Day’s interactions with the great and good had an almost ambassadorial dignity compared with the modern breed. But he still had his moments.

In 1982, on Newsnight, Day asked the Secretary of Defence, John Nott: ‘Why should the public believe you on this issue, a transient, here today and gone tomorrow politician, rather than a

senior officer of many years’ experience?’ Nott unclipped his microphone and walked off the set.

Divorced with two sons, Day had a forensic mind, a dry wit, messianic self-belief and great charm, even if the last came with a sensitive on-off switch. He died of a heart condition in August 2000, at the age of 76. Describing his craft, he once said: ‘The interviewer should be firm

and courteous. Questioning should be tenacious and persistent, but civil.

‘I shudder to watch interviewers who think it clever to be snide, supercilious or downright offensive.’

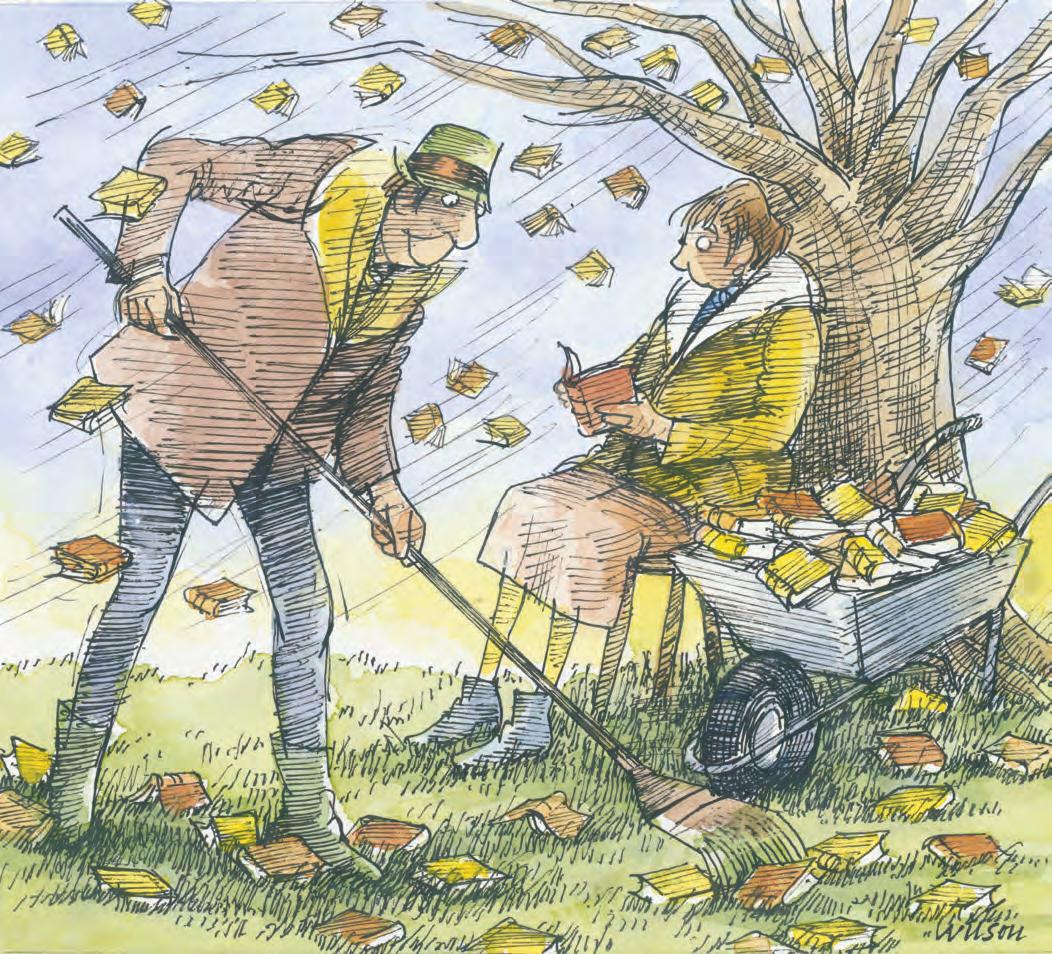

It’s a welcome return to bookshops for Andrew Barrow’s The Tap Dancer, a comic classic, first published in 1992 and now reissued in a new edition by HarperCollins.

When it came out, Alan Bennett

said of the book by Barrow, an Oldie contributor, ‘My favourite novel and one I wish I’d written.’

The story of a son’s irritation at being the butt of his father’s jokes and victim of his brothers’ indifference, it’s a favourite of the regular Oldie contributor Craig Brown. Brown says, ‘Andrew Barrow has the most curious, in both senses, comic ear and, as if by magic, can turn everyday speech into the stuff of sublime comedy.’

‘I know it’s junk food, but sometimes you just can’t say no’

The Oldie October 2023 7 TRINITY

MIRROR / MIRRORPIX / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Happy 100th birthday! Sir Robin Day with journalist Sarah Baxter

‘Caroline, is there any truth in these rumours about you and that reman in the upstairs at?’

An everyday story of lesbian lust

Are you into podcasts? I am in a big way, but a lot of other oldies aren’t. I even have friends who pretend not to know what a podcast is.

‘Radio 4 is good enough for me,’ they say. And, yes, Radio 4 is indeed glorious. I have just been recording another couple of episodes of Just a Minute (a Radio 4 staple since 1967), and, with Sue Perkins now happily at the helm, I think the show is as fun and funny as ever. Same goes for The Archers – a radio favourite since 1951.

With The Archers, of course, you get a lot more sex than you do with Just a Minute. From Ambridge the other day, we were treated to the radio soap’s firstever on-air lesbian kiss.

We have had gay girls in Borsetshire before, but this was the programme’s first audible Sapphic encounter.

Pip Archer was none too keen on Stella Pryor at first, but when Stella’s dog Weaver was killed in a farm accident (remember, this is an everyday story of country folk), one thing led to another, and what began as a comforting hug transmogrified into an erotically charged osculatory embrace.

It was nicely done. It felt unforced and authentic.

The Archers regularly credits its agricultural advisers. If there was an intimacy coordinator in the studio on the day of this particular recording, we were not told, but they should take a bow.

BBC Radio can give you lots. Podcasts can give you lots, lots more. Essentially, a podcast is an audio production made available in a digital format for downloading over the internet.

The word ‘podcast’ itself first saw the light of day in an article in the Guardian in February 2004 – so it might be a misprint. But if it isn’t, some say the word is a contraction of ‘iPod’ and ‘broadcast’, while others claim the ‘pod’ part is an acronym for ‘portable on demand’.

Either way, there are at least five million podcasts out there for you to choose from (produced in a multiplicity of languages in countries around the world) and you can access them via your computer or an app on your iPhone or by barking at the device on the kitchen sideboard, ‘Alexa, play The Oldie podcast!’

Politics, pornography, true crime, self-help, gardening, goitres (and how to live with them) – you name it and there’ll be a podcast series (or several) devoted to it.

The production quality varies, but the best of them rival (and sometimes outclass) anything that the BBC has to offer.

For five years, I have been presenting a weekly podcast about words and language with my lexicographer friend Susie Dent. It’s called Something Rhymes With Purple because I thought purple (like orange and silver) was an unrhymable word. I was wrong. To hirple is to walk with a limp.

This month, I’ve launched a new podcast called Rosebud.

Admirers of Citizen Kane won’t need to ask why. It’s all about first memories. What is your very first memory? Not one prompted by an old family photo, but truly your first recollection.

That’s where the conversation starts and then it leads to other firsts. Dame Judi Dench, my first guest, told

me that her first boyfriend was called David Bellchamber.

‘We were six at the time,’ she revealed, ‘and I knew he was serious when one day he said to me, “I think we should start calling each other ‘darling’, don’t you?” ’

I have a different guest every week. Many are old friends, such as Judi Dench or Miriam Margolyes (much of what she told me is podcastable but not necessarily broadcastable – that’s the joy of podcasting: anything goes), but I am meeting new people, too. For example, Nicola Sturgeon.

That was a podcast encounter that took me by surprise: a) because I really liked her; b) because she was so candid about her singular childhood; and c) because she told me how much she liked, admired and felt indebted to our late Queen – which was something I didn’t expect from the firebrand former leader of the Scottish National Party.

‘She was very kind to me,’ she said. Nicola, a Glasgow girl, also told me about her first love. His name was ‘Sparky’. ‘And he was,’ she said, grinning.

My friend Michael Plumbe has died, aged 91. He was a good man with a serious love of language. I knew him through the Queen’s English Society. When Mike last emailed me, days before his death, I thought he was losing it. But once I had given his email the attention it deserved, I realised he wasn’t.

‘I codnul’t blveiee waht I was radnieg,’ he wrote. ‘Aoccdrnig to rsceearh at CmarbgdieUinervitsy, it deons’t mttaer in waht oedrr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer are in the rghit pcale. Bcuseae the hamun mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istelf, but the wrod as a wlohe.’

Rset in paece, Mkie. It was fun kowning you.

Gyles’s latest book is Elizabeth – An Intimate Portrait

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

There’ve been gay girls in Borsetshire before – now we’ve been treated to their first ever on-air kiss on The Archers

The Oldie October 2023 9

DAVID BETTERIDGE / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

First love: Judi Dench

Put the brakes on, Cycling Mikey

This is absolutely the last thing a writer on nodding terms with sanity would admit to in print. If the editor has any residual professional pride, he’ll start the trenchant sacking letter on reading the next sentence.

But I cannot find the words.

I can, not to brag, find some words. However, the adequate words for a certain Mike van Erp remain beyond location.

I’ve been searching fruitlessly for them for about a month, since reading about him in the Sunday Times. Every time I think about him (and I’ve thought about little else), a peasouper of psychotic rage descends to blind whatever bit of the mind’s eye peruses the frontal lobe for mots justes.

What follows, to spell out the preemptive apology, is guaranteed to be even closer to unredeemed gibberish than that old mythological pal ‘the regular reader’ has been schooled to expect from this page.

What I can do is offer some dainty morsels from the article, in which a reporter tracked Cycling Mikey, as he pleases to know himself on social media, going about his business as a vigilante of His Majesty’s thoroughfares.

Now let it be stated that, in the unending battle between driver and cyclist – as asymmetric a contest as those between rifle-toting cowboys and native American archers – all my sympathies lie with the latter.

Drivers tend to be selfish, entitled horrors who merrily ignore the safety of bikers. The Daily Mail-ish, smug, middle-aged-white-male notion that speeding is a matter of personal choice, and not criminality, is an abhorrent perversion of libertarian sentiment.

Cycling on city streets is a wickedly dangerous pursuit. So I doff my cap to Cycling Mikey, and others such as Jeremy Vine, who devote themselves to shaming

and facilitating the punishment of hateful drivers who put their lives in peril.

But… but… but… argh… really, I mean, really… I mean… in the name of all the saints.

Nope, can’t find them. A short break and a swig of Famous Grouse may assist.

All right then. Where Cycling Mikey loses our admiration – and I hope this once I speak for us all – is that he doesn’t content himself with going after the bad guys. He also enjoys grassing up drivers who are no threat to anyone.

Wearing a helmet with a video camera embedded, he looks through windows as he pedals up, filming anyone he catches touching their phone, and forwarding the footage to a police website.

He does this even when the driver… he does this even when… he does this… nah, I need another swig.

OK.

He does this even when that driver is stationary in a traffic jam, with handbrake on and engine off.

Technically, of course, this is a crime carrying a likely penalty of six penalty points (half a ban) and a heavy fine. Even so, and to underline a previous point, what can you say?

In the piece, Cycling Mikey relished a novel experience. ‘I haven’t yet caught a member of the emergency services,’ he said on finally breaking that regrettable duck. When an ambulance driver, stationary in a jam, checked his phone, CM sidled up to film it.

The paramedic’s admission of guilt and courteous apology cut little ice with our Nemesis. ‘I’ll be reporting him,’ he told the reporter. The outcome of another plea for clemency, from a static

motorist with six points on his licence, whose livelihood would vanish if dobbed in, isn’t clear.

‘I felt his pain,’ admitted CM, ‘but nice people still end up killing and seriously injuring others.’

Indeed they do, albeit though seldom, one has to believe, when their vehicles are not in motion.

In his defence, his cyclist father was killed in Zimbabwe, albeit by the drunk driver of a moving car rather than some poor sod glancing momentarily at a message while travelling at an estimated 0.000000mph.

He is evidently a decent chap, earning a portion of his living by caring for a disabled teenage boy. The rest, presumably the bulk, comes from advertising on a bespoke YouTube channel with some 100,000 subscribers.

And, undeniably, the man is brave. As observed by one of the great poets – Lord Byron, perhaps, or possibly Homer (Simpson) – snitches get stitches. One of these days, some gridlocked nebbish facing unemployment for touching a mobile could do something truly awful to him.

Genuinely – forgive the piety –I hope not. Grief does peculiar things to people, while that portion of his hobby that punishes horrific drivers (not exclusively in black Range Rovers; other 4x4s are available), and deters others from imperilling cyclists’ lives, is noble and valuable work.

But God forbid someone caught with engine off lashes out. Presuming that at least a few of the 12 good people and true are London motorists who spend much of their miserable lives in gridlock, I am reminded of the philosopher Bernard Manning’s thought on Ken Dodd’s acquittal for tax evasion.

‘Get a bleedin’ conviction? In Liverpool, they were f****** lucky to get a jury together.’

Grumpy Oldie Man

The two-wheeled vigilante should stop harassing gridlocked drivers matthew norman

The Oldie October 2023 11

‘As one of the great poets observed, snitches get stitches’

what was bicycle face?

The dawn of the modern bicycle age at the end of the 19th century ushered in a moral panic among the guardians of public virtue. Some doctors warned that using the contraption could lead to a medical condition they dubbed ‘bicycle face’.

‘Over-exertion, the upright [and immodest] position on the wheel, and the unconscious effort to maintain one’s balance tend to produce a wearied and exhausted “bicycle face”,’ reported the Literary Digest in 1895.

It went on to describe the condition: ‘usually flushed, but sometimes pale, often with lips more or less drawn, and the beginning of dark shadows under the eyes, and always with an expression of weariness'.

Elsewhere, others said the condition was ‘characterised by a hard,

what is micro-cheating?

In our day, you were cheating if you were caught red-handed in bed with the wrong person. Nowadays, cheating is far more nuanced, with layers of tiny betrayals or ‘micro-cheats’.

Young people connect online, often by liking someone’s Instagram photograph or TikTok post, as well as responding to Snapchat messages. Yet if you have declared you are committed to someone, those actions are then deemed microcheats – and you’ll know immediately if it’s happening to you.

If you are following your beloved’s social media profile online – which you are certain to be – you can see instantly if his or her number of followers or friends has increased. You can quickly ascertain who the new friend is – and woe betide your beloved if it’s a good-looking person. That is a micro-cheat.

Today, there are numerous means of meeting people virtually, and a correspondingly large number of ways

clenched jaw and bulging eyes’, which was of course most unfeminine.

In 1895, the New York World published an exhaustive list of don’ts for women riders: ‘Don’t imagine everybody is looking at you’, ‘Don’t use bicycle slang. Leave that to the boys’ and ‘Don’t cultivate a “bicycle face”.’

In an 1897 article in London’s National Review, British doctor A Shadwell claimed to have coined the phrase. He described the dangers of bicycling, especially for women, saying ‘cycling as a fashionable craze has been attempted by people unfit for any exertion’.

So what was really going on?

Threatened by the speed with which cycling was taking off, and what it could mean for society and women’s role in it, the Establishment attempted to ridicule, or even medicalise, a perfectly normal activity.

If women decided to hop on their bikes, what might they do next?

Developing ‘bicycle face’ was the least of the female cyclists’ concerns, especially for America’s

Annie Londonderry, who cycled around the world between 1894 and 1895. She made the move from skirts to bloomers to a man’s suit during the course of her journey, slowly becoming more and more of an affront to those who thought women cycling was uncouth.

The press said, ‘Miss Londonderry expressed the opinion that the advent of the bicycle will create a reform in female dress that will be beneficial. She believes that in the near future all women, whether of high or low degree, will bestride the wheel.’

Although she was a bit of a fabulist when it came to her own adventures, Londonderry wasn’t wrong about both the change in dress – out went the whalebone corsets and in came shorter dresses, split skirts and even bloomers –and women’s push for freedom.

The silent steed has been the choice and symbol of suffragettes and feminists the world over, promising its riders the pleasures and advantages of speed, good health and greater freedoms.

Sonia Zhuravlyova

of tracking people’s activity and catching them out. If your partner has claimed to have blocked an ex, and then that ex’s name pops up in a group comment on a shared post while you’re watching a movie or TikTok video together on your phone, your partner has lied and micro-cheated.

This ability to monitor who’s doing what with whom, has created an atmosphere in which even a minor infidelity is not to be tolerated.

My 19-year-old daughter, approached by three boys on a Greek beach, refused to divulge her ‘Snap’ or allow them to sit down with her, on the basis that she has a boyfriend. In fact, the ‘boyfriend’ was not even ‘officially’ her boyfriend, given there is a whole other set of rules around what constitutes an ‘official’ relationship. Secondly, how her boyfriend was supposed to find out about such an oldfashioned, non-virtual approach, I am not at all sure. But that’s beside the point because today’s generation feels a strong obligation to these draconian rules of amorous engagement.

In the same way, she turned down the

offer of a friendly mum who suggested her son take her out with his group of friends to get to know more people on the island we were holidaying on. Even though it was merely a social, friendly gesture, any kind of one-to-one contact with a member of the opposite sex can be construed as a micro-cheat.

Given most oldies spent their entire youth chatting people up both socially and sexually, most of us forged many good, lasting friendships with the opposite sex. My daughter sees my large cohort of men friends as proof I am a flirt, and flirting is no longer acceptable unless you have made it very plain on every online platform that you are single.

Living via social media means it’s never been easier to track other people’s movements. In our day, you’d have to hire a private detective to discover what young people can find out in a micro-second.

This constant surveillance means we’re moving inexorably into a morally prescriptive age with the growing ability to police and punish every micro-cheat.

Charlotte Metcalf

12 The Oldie October 2023

Pedal power struggle

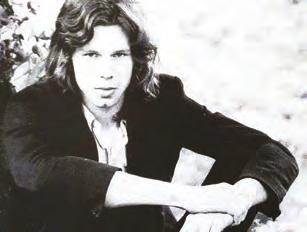

My invitation to Camelot

In the early Seventies, little girls fresh from stage school were thick on the ground. They were common as daisies in a field and regularly picked off and handed round the studios like sweets.

I was a convent girl and that had an even wider appeal. One in the eye for the nuns – and somehow more challenging.

If this sounds cynical, it also happens to be true.

But among the dross there were some very decent and respectful souls. It was learning how to distinguish them.

The occasional big star would procure girls via their agents or management. Producers would be more direct and could make life unbearable for an actress unless she played footsie. But force was rare and most ingénues knew that complying could lead to fame and fortune – if you were very lucky and had a degree of talent and looks.

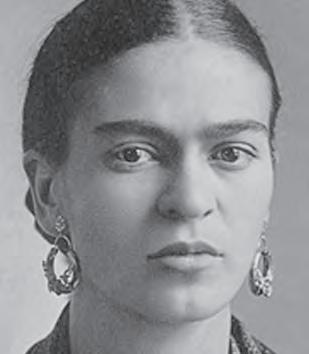

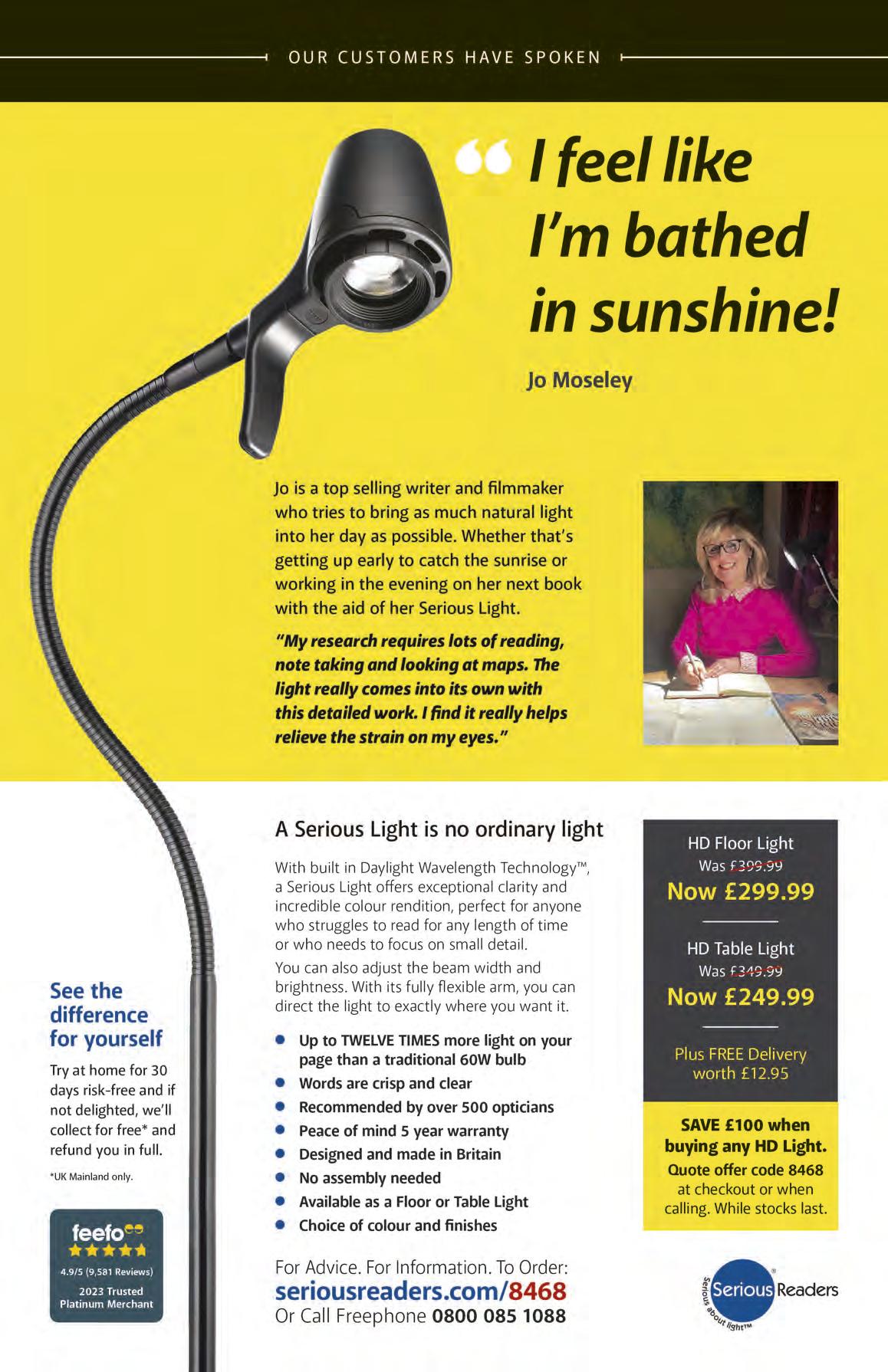

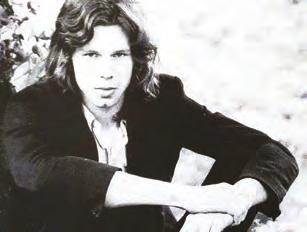

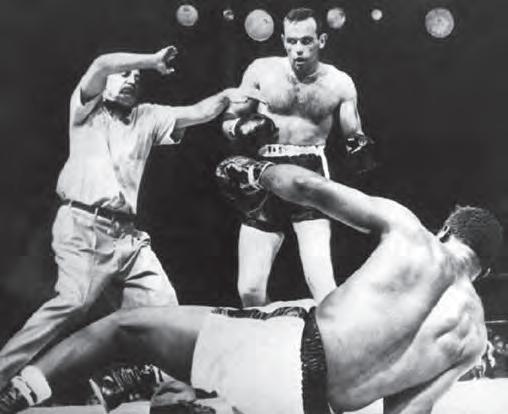

My small star was in the ascendant in 1971, when I was 20 – and Richard Harris rang. Or rather, his management contacted me.

I had been seen regularly on television in The Two Ronnies and various other comedy shows. I am guessing that this was why Richard was keen for us to meet.

He was then 40, the mightily successful star of This Sporting Life (1963) and Camelot (1967).

A beautiful Rolls-Royce arrived at my gate in Kew and there were flowers to entice me to the Savoy Hotel where he spent most of his time, ignoring his mansion in Melbury Road, Kensington.

He emerged from his hotel room, wearing caramel leather. A long coat

MOVIESTORE / SHUTTERSTOCK

Richard Harris enchanted Bond Girl Madeline Smith with poems and letters but, to her eternal regret, she spurned him

14 The Oldie October 2023

When Irish eyes are smiling: Richard Harris (1930-2002)

I adored him but had no idea where we’d go in this extraordinary relationship

made him look godlike. He was a very handsome man.

I was treated with the utmost respect. He was delightful company, and even more so when he visited my parents in Kew.

My father, of Scottish and Irish descent, was completely intoxicated by him. They chatted together about Irish poets and music, as they stood together in the garden.

Then Richard leapt on to my bicycle and tore up the lawn. He was on fire. I adored him but had no idea where we would go from here in this extraordinary relationship.

I knew his reputation with drink and was fearful. I was also still virginal, despite appearances created by the ever-eager photographers in 1971. I was always too willing to comply and the images they created on film were very far from my shy and inhibited self.

I had remarkably little to say for myself and genuinely wondered what this fascinating and complex man would see in me.

I do not believe I ever properly read his very touching letters and poems, which appear here for the first time. It really cuts me up to admit this to myself, as I now look at the wonderful poem he sent me in May 1971.

Here is an extract:

Time flies. It flies timelessly Into a page of nothingness.

Strangers touch with touching hands Touchingly.

A deep meeting.

Fleeting time

Disentangles

Gentleness, Pushing fingers into memory. Nothing will remain; Only the warm, planted wildflowers of impression.

A glow in winter.

A love song sung in the palm. Reflections of a distant future Mirrored into today’s yesterday.

Time washes.

Nothing is removed.

It only dries the eyes of the fingertip tears

That smears

The ripe departure.

And how I like another poem he wrote to me from the Savoy Hotel in 1971. Here is an extract:

your

Thought of you while sleeping Thought of you while Thought of you Thought of Thought

I blame my lack of maturity for what happened next.

Richard was filming The Snow Goose (1971) with Jenny Agutter, who was then dating Patrick Garland. The film was Paul Gallico’s masterpiece.

Richard rang me from location late at night. He was well into his cups. He invited me to come down NOW to the location and join him there. It hurts me

to recount that I was terrified, had no idea what my parents would say and – oh foolish girl – I pretended I was seeing somebody else. As I write this, it is with disbelief, as though it had happened to somebody else.

I was later seized with dreadful guilt and regret. I never heard from him again.

The fault was entirely on my side. How very different his and my lives might have been.

The Oldie October 2023 15

For

eyes only: Madeline Smith in 1971

Madeline Smith starred in the Hammer horror films and was Miss Caruso, a Bond Girl, in Live and Let Die (1973)

The Man with the Golden Pen

One chief of British Intelligence described James Bond as ‘the best recruiting sergeant in the world’.

Another former head of MI6, Richard Dearlove, agrees that the fictional spy’s impact has been huge: ‘Definitely, it’s had a positive effect. It’s made the Service the most famous intelligence organisation.

‘There is no linking or reality at all, but that’s not really the point. It’s reputational, it’s myth-building, it’s contributed to the brand. In the most distant part of the world, everyone has heard of MI6. There are big espionage cases, not just walk-ins like Oleg Gordievsky and Vasili Mitrokhin, where people have gone to the British when it would be more logical to approach the Americans, and who particularly like the British because of the Bond culture.’

This is more than borne out by my interview with the former KGB colonel Alexander Lebedev. We meet in the Edition Hotel, off Oxford Street.

Fifteen minutes late, in he strides: a man in black, blond hair cropped short, early sixties, round glasses. He guides me into a back room, curtained off, where a table is reserved. Part philanthropist, part fantasist, part tabloid gangster, Lebedev is surrounded by staff who come up or contact him on the iPhone he monitors on the stool beside him.

He said, ‘In 1982, I first worked for KGB. I went to Libya to tell stories about Lenin in Tajoura. I had studied English. To be or not to be. I read that again the other day. How does it go on?

‘I still need to refresh my memory, but my mother was a teacher of literature and history. When first I became aware of Fleming? Not before 1988, when I arrived in UK. I still watch the movies. I’ve seen all of them. I look at my wife, Elena. I really think she would do a good movie. I show you. This is the

trailer. We’ve finished seven seconds. I’m going to show to John Malkovich and Kevin Spacey.’

He plays me the brief sequence on his phone. In a tight red onesie, gripping two long-barrelled pistols, his wife shoots at various white busts on pedestals which crash to the ground. It appears to copy a Bond movie in every frame.

‘It’s called Banksters. Set in Russia, Ukraine, the US. It’s about bankers, corruption, about global financial fraudulence, apartheid – dramatic, full-scale fiction.’

He puts the phone down. ‘I started reading Ian Fleming when I came here. Smiley, yes.’

‘Smiley is le Carré.’

Ian Fleming was an underrated figure in the Second World War and after – and an influence on John le Carré.

/

By Nicholas Shakespeare

M. MCKEOWN

GETTY IMAGES

16 The Oldie October 2023

Fleming: 'in the inner sanctum of covert operations'

He thinks about this. ‘Le Carré is more closer to reality. Bond, it’s an adventure.’

Soon after, he stands up. He has to go. He is joining his son Yevgeny for a party they are throwing for the UK’s new prime minister of a few hours, Boris Johnson.

At John le Carré’s last public appearance, I put it to Fleming’s most obvious successor, whom I had known for more than 30 years as David Cornwell, that he had created George Smiley as a rebuke to James Bond and an embodiment of everything Bond was not – cuckolded, ugly, old, unsporty, cerebral, morally torn.

Yet didn’t the two authors have elements in common – even though le Carré seemed to want to place as much distance as he could between Fleming and himself? Both had left their British private schools early and gone to live in Switzerland and Germany, where they learned to ski well. Both had joined the British Intelligence Service, with Cornwell nearly coming to work for Fleming on the Sunday Times as part of the Mercury team (which recruited a number of intelligence officers).

Both had married an Englishwoman called Ann; both wrote their break-out novels in a matter of weeks. Both received brickbats when they tried to escape their genre. And le Carré, having set up real battles within the soul when his books begin, often ends them with Ian Fleming climaxes.

The parallels did not end there. Le Carré had used Sean Connery and Piers Brosnan as lead actors, and Paul Dehn (Goldfinger) as a screenwriter (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold), and, for his next project, le Carré had told me, he wanted none other than Daniel Craig to play Alec Leamas in his new six-part adaptation of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold.

Even if it were merely to recoil from him, le Carré’s denial of any indebtedness to Fleming (‘I have never had much interest in him or his books’) was as impossible to swallow as his shifting stories about how he had come up with his pseudonym – on a shopfront seen from the top of a double-decker bus, being the most common.

But, as his biographer, Adam Sisman, says, ‘He provided several different explanations of why he chose the name John le Carré, and afterwards admitted that none of these was true.’

Ian Fleming told Georges Simenon how he followed Balzac’s method of borrowing his characters’ names from ‘a good name outside a shop’. Then I read

Fleming’s description in Thrilling Cities of the Casino in Monte Carlo, where Ronnie Cornwell had taken the young David to gamble for perilous amounts.

What pulled me up was Fleming’s reference to the call of ‘Carré’ uttered by the croupier amid ‘all the noisy abracadabra of one roulette table’.

At once, I thought of the first Bond villain, Le Chiffre, who meets Bond at the baccarat table a decade before Cornwell chose his pseudonym. I thought of Le Cercle, Fleming’s group who frequented casinos in pre-war France. And I made this extravagant leap: could Cornwell have come up with ‘le Carré’ in subconscious homage to Le Chiffre and Le Cercle and the croupier’s ‘Carré’ calls – to Ian Fleming, in other words? I emailed him. No answer. He had died.

Bond, as ex-Colonel Lebedev astutely observes, is ‘adventure’. But what I discovered after four years in Ian Fleming’s company, uncovering material that because of his secret status has taken its time to be released, is how much Fleming’s life was ‘closer to reality’ and more harrowing than Bond or le Carré put together. Fleming actually lived the seriousness which le Carré’s novel sought to convey. Le Carré, like Bond and Graham Greene, was only a minor player in British Intelligence.

‘The trouble with David,’ said one MI6 colleague, ‘is that he was never involved in a successful operation.’

Fleming, by contrast, was in the inner sanctum of the ‘central inaccessible citadel’, as his naval intelligence chief,

Admiral Godfrey, called it – and a more significant figure in the history of covert operations than Bond, le Carré or Greene ever were.

Ian and his brother Peter formed part of an unbelievably select group who were cleared to know the war’s top secrets, the decrypts from the codecracking centre in Bletchley Park. In April 1940, the list of those with access to this information, known as Ultra, was restricted to less than 30.

Fleming was also one of a trusted few who were charged with trying to bring the United States into the fight, and worked to set up and then coordinate with the foreign intelligence department that developed into the CIA. Following the Allied victory of 1945, he continued to play an undercover role in the Cold War from behind his Sunday Times desk.

When all this is said, Fleming emerges as significant despite Bond and not wholly because of Bond. He was an influential figure in his own right, someone even world leaders wished to consult, who had a fascinating story to tell, but one that security concerns and a strong stripe of diffidence prevented him from writing.

To simplify horribly, there would be no James Bond had Fleming not led the life he did. But if Bond had not existed, Fleming is someone we should still want to know about.

on 5th October

LONDON RED CARPET / ALAMY The Oldie October 2023 17

Ian Fleming: The Complete Man by Nicholas Shakespeare (Harvill, £30) is out

John le Carré wanted Daniel Craig to star in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold

Jobs for the girls

Women were once confined to typing, cooking – and ironing Mr Right’s shirt. By Ysenda Maxtone Graham

On the last morning of the summer term at the all-girls St Margaret’s School, Bushey, in the 1950s, the deputy headmistress would walk each leaver, one by one, up the aisle of the school chapel at the final assembly.

This was a rehearsal for their fathers walking them up the aisle of a church, which it was expected they soon would.

Marriage was their hoped-for imminent destination. But what did Britain’s daughters do between the final assembly and the day of meeting Mr Right? Did they master any new skills? Did they earn any money?

These were my questions, in writing Jobs for the Girls: How We Set Out to Work in the Typewriter Age.

I used to be good at guessing at first glance whether a woman had been to Cheltenham, Heathfield or St Mary’s Ascot. It was partly the shins, partly the timbre of voice.

My new skill is guessing women’s post-school trajectories.

‘Did you leave school at 16, without a maths O-level, then go to a finishing school in Switzerland, perhaps Tah-Dorf or Mon Fertile, and then do the London Season, and then did you go to St James’s Secretarial College, or was it Mrs Hoster’s, and then did you work as a secretary in – well, perhaps not quite 10 Downing Street but somewhere in, say, Mayfair?’

‘How did you guess?’

Or I ask, ‘I think you might have got into Oxford or Cambridge. Was that thanks to a crammer? But I bet you still had to go to a secretarial college, as that was often the only way in for women.’

Or ‘I bet you got into one of the London hospitals to train as a nurse. Did you live at a nurses’ home with a candlewick bedspread?’

‘How did you guess?’

These were the broad brushstrokes of women’s experiences, in those days when life was much more prescribed than it is today. Deprived of maths and science

O-levels by their unambitious schools, many young women were stymied in terms of careers before they even started.

They weren’t qualified to train for medicine or the law, unless they’d put a foot down in their early teens and demanded to be allowed to do the relevant subjects – which only the boldest girls (often seen as ‘stroppy’ or ‘difficult’) did.

The rest peeled off into what I now think of as a lost world: a world of eccentric institutions to keep them occupied and prepare them for adulthood, and a world of a million ‘little jobs’.

One of my favourite photos in Jobs for the Girls is of a gaggle of young women in aprons and bonnets, on the cusp of adulthood, who’d been sent to the Atholl Crescent School of Domestic Science in Edinburgh, to be trained in the art of making sheep’s-head broth and ironing men’s shirts. I was told the fiancé of one of the students broke off their engagement when he found out she’d failed the hygiene exam.

Secretarial college girls found themselves back in yet another strict institution run by severe, snobbish and

(this time) shorthand-obsessed old ladies. The nearest those ladies ever got to a witticism was asking the girls each morning, ‘So, which of you came up on the milk train?’. That meant, ‘Which of you was at an all-night party last night?’

The true test of success at the Whitehall Secretarial College in Eastbourne was answering ‘Yes’ to ‘Do you dream in shorthand?’

When it came to getting a job, there were millions of the things. They dangled like apples from a tree. You could pluck one, taste it, and if you hated it, you could discard it and get another one the next week.

‘We wore our jobs lightly,’ said Perina Braybrooke, among whose first jobs in the early 1950s was working in the watch department at Asprey’s. One of her duties was to take all the valuables out of the shop window before going home. She says, ‘I took them out at 3pm so I could get to my party.’

These young women could rent cheaply, shared ‘digs’ with friends in Knightsbridge and South Kensington. Lunch hours were long, giving them time to get their hair done.

Penny Eyles recalled having her hair washed and set at Hebe’s in Aldwych in her lunch hour, having first booked her snooty advertising bosses into Rules for their much longer lunch.

She re-emerged ‘back-combed, doused in hairspray, and looking like my mother, the whole creation shaking in the wind on Waterloo Bridge’.

I was a university leaver in 1984 who failed to get a job as a sales assistant at Zwemmer’s bookshop, as there were 1,200 applicants.

So that earlier jobs cornucopia sounded like a golden age, in spite of the tyranny of carbon-paper layers and bossy men in charge.

18 The Oldie September 2023

ALAMY

Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s Jobs for the Girls: How We Set Out to Work in the Typewriter Age (Little, Brown) is out on 27 September

Just my type: a class in the 1950s

My interview Hell

Ibroke a self-imposed rule some years back and did an interview with a broadsheet – the Daily Telegraph – to advertise something or other. God knows what. The subsequent article didn’t mention it, but it got publicity all right.

It went to form. The journalist didn’t usually do this sort of interviewing lark. He had been involved with famous people I had once employed. He told me earnestly that he wanted to return to TV.

OK… I had to very gently explain that it was beyond my powers to help him. A minor celebrity press interview is a highwire juggling act. The interviewer is, after all, demeaning themselves. They should be talking to Brad Pitt or the King, or someone more worthy of their attention. So abase yourself.

Be watchful, too. Be bland about the

BBC. Don’t be accused of ‘ranting’ about your employer.

Money? Sidestep that, for God’s sake. Reports of my wealth have been greatly exaggerated, but I am clearly undeserving. To say or even imply that I don’t worry about it, provokes an underlying belief that you are ‘lying’. A big mistake.

Try to be gently humorous, obviously. (The Sunday Times, after a ten-minute phoner about wind farms, reported that I was ‘totally unfunny’ in real life.)

But, whatever you do, no irony, hypotheticals or hyperbolic exaggeration. They will always be taken literally.

So I chattered away. The interviewer hadn’t booked the public room in the Charlotte Street Hotel where we met, but he wanted privacy. He kept slamming the door. The staff kept opening it again.

He got increasingly exercised, not to say unhinged, and I was gradually forgetting my basic rules.

An interview is evidence. There is no part of what you say – no sentence, chance remark, caveat or three-word correction – that may not be taken down and used against you. And it goes on for three hours.

In this case, we came suddenly to the proposed mansion tax – a notion hovering around before a recent election. ‘Ha ha. That. I want to make something clear. I don’t take any political view on this at all. It is entirely up to the government,’ I waffled.

‘But you live in a big house, don’t you?’ ‘Er…’

Now, when somebody says this sort of thing, you can lie.

Never lie! Never lie. If he had said,

20 The Oldie October 2023 ITN / SHUTTERSTOCK

When Griff Rhys Jones spoke to a journalist, he didn’t realise every self-righteous ninny on Fleet Street would lacerate him

Head to head: Mel Smith and Griff Rhys Jones, Not the Nine O’Clock News (1985)

‘You have a big todger, don’t you?’, I would have honestly set him right. ‘Huge.’ Don’t joke!

And I did live in a big house. You can possibly see exactly how big online, because a columnist from the Guardian later published my exact address along with the actual floor plans of my house, on the basis that I was stealing land from the people.

But I was stumbling now… I wanted to explain that the valuable house was an accident. We bought it in what was a cheap place, a long time ago, when it was a wreck. We wouldn’t have the ready cash to pay a big annual tax, but it didn’t matter. That was the point.

My family were grown-up, and we were old and probably going to downsize anyway. Phew.

Ponder that incontinent splurge, do, because every single, hurried, get-out excuse caused a fury of contempt, derision and troll violence.

How dare I suggest that I might not want to pay the mansion tax? How dare I imply the house was a wreck? Some people live in real slums. How dare I live there when, just across the road, there was a health centre that served real people, said Bonnie Greer.

Yeah, I didn’t get that last point either. But what triggered a super-geyser of sewage was the observation that it was no longer easy to do what we had done: ‘You wouldn’t find a run-down house in London any more. I would probably have to go to France in search of a big, dilapidated house.’

The interview duly appeared. A mate messaged me early to tell me how funny it was. Good. But then I bought the rag and saw the front page. There was a banner headline: ‘Griff Rhys Jones says he will leave the country if the Labour Party gets in.’

Eh? I froze. Note: there were no quotation marks here. I did not actually say such a thing. Neither ‘off the record’ nor as an aside. Why would I? Such a concept was utterly absurd. It was a sort of wild, speculative surmise, based, somehow, on that last sentence.

The world imploded. A torrent of abuse spouted forth. Every prig, selfrighteous ninny on Fleet Street and social posturing nincompoop online took the opportunity to lacerate me.

Friends rang up, aghast. I have never been on Twitter. I have seen reasonable

and much-loved National Treasure friends destroyed by it. So I was kept abreast of what was happening.

On Saturday morning (and I guess this was because its members had to work as sociology lecturers), Class War arrived, yelling and frothing, in the square outside the house.

After demanding that I come outside to face their wrath, they stuck stickers on my door (and my neighbours’, too) and poured superglue into the locks of nearby BMWs.

I didn’t see this. Well, I was in my house in the country. But, hey, I got their point.

They weren’t as loud as my agent, darling wife and close friends. What was I going to do? I was doomed. This was the end of me.

I went to noted lawyers. They sent me a shopping list of charges. To silence a newspaper – a sizeable sum – per rag. And an exact charge for shutting down each and every online reference. Per reference. It seemed reasonable at £175 plus VAT, until a little mental calculation of what ‘trending’ actually meant in terms of sheer volume.

Should I talk to Rod Liddle, go on Newsnight, appear on LBC, speak to the Mirror and hold a press conference? Reply on Twitter? Sue? All these were instantly on offer.

I did nothing. Nothing at all. I dismissed the lawyers. I ignored everybody. I didn’t even hide under the table. I gave no opinion, justification, response or comment. I just didn’t exist as a mouthy gob for three days.

And the result? By Monday, it was gone – a tumbleweed storm in a doll’shouse teacup. The overheated, ravenous mob of priggish sewage-stirrers poured into another gutter. If I mention this now, even to journalists, they are bemused, because it made such a gigantic low impact. It was meaningless.

Seriously, the press, the internet, the shrill, screaming narcissistic, powerseeking cancel culture is entirely without form or merit or even power, if you are prepared to utterly ignore it.

Respond and you are doomed. If I had answered back or sought the truth, I genuinely believe you would have known about all this already.

Though, of course, now you do. But be reassured: it is effluent under the bridge.

* Books for UK addresses only Europe/Eire:

£58; USA/Canada:£70; Rest of world: £69 To order your subscription(s), either go to www.subscription.co.uk/ oldie/o ers or call 01858 438791, or write to Freepost RUER–BEKE–ZAXE, Oldie Publications Ltd, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF with your credit-card details and all the addresses. Always quote code POLD1023 This o er expires 4th October 2023. Subscriptions cannot start later than with the November issue WHEN YOU TAKE OUT (OR GIVE) A 12-ISSUE SUBSCRIPTION FOR £49.50* SAVE £13.50 over 12 issues BEAT THE PRICE RISE AND GET TWO FREE OLDIE BOOKS WORTH £14.90

The press is entirely without power if you are prepared to utterly ignore it

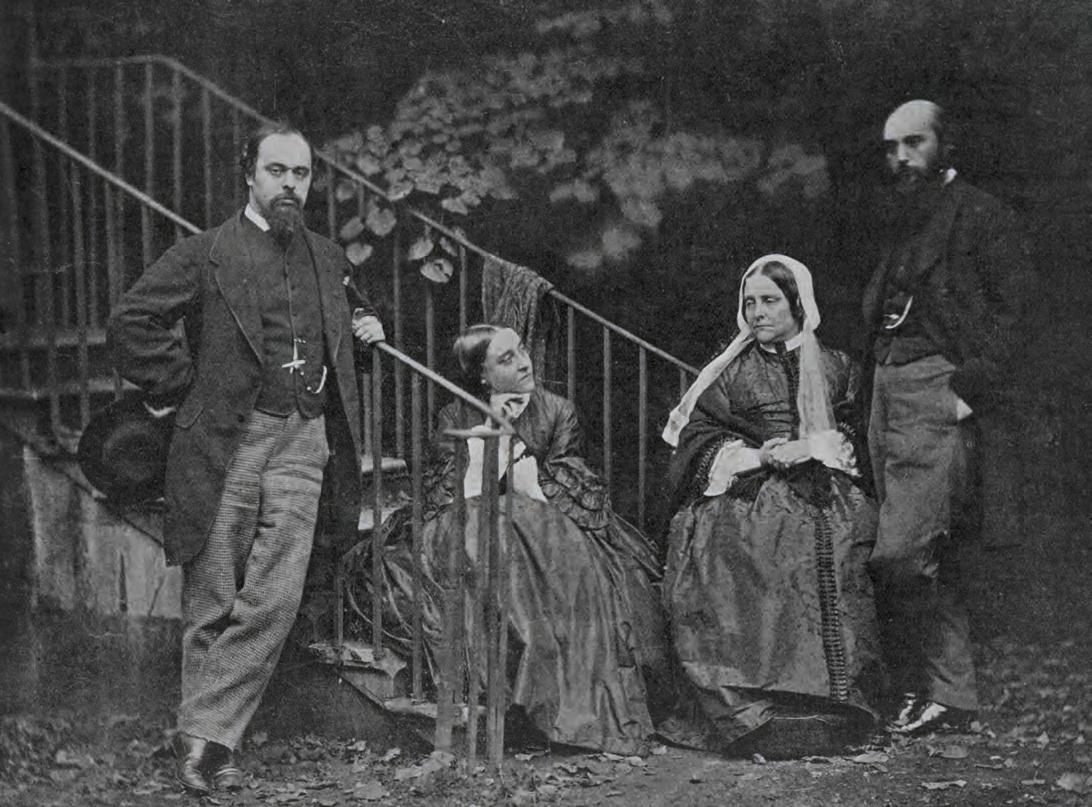

Lodging with Uncle Tony

Lady Antonia Fraser tells Harry Mount about staying with Anthony Powell, her uncle, as he began A Dance to the Music of Time in 1949

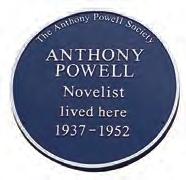

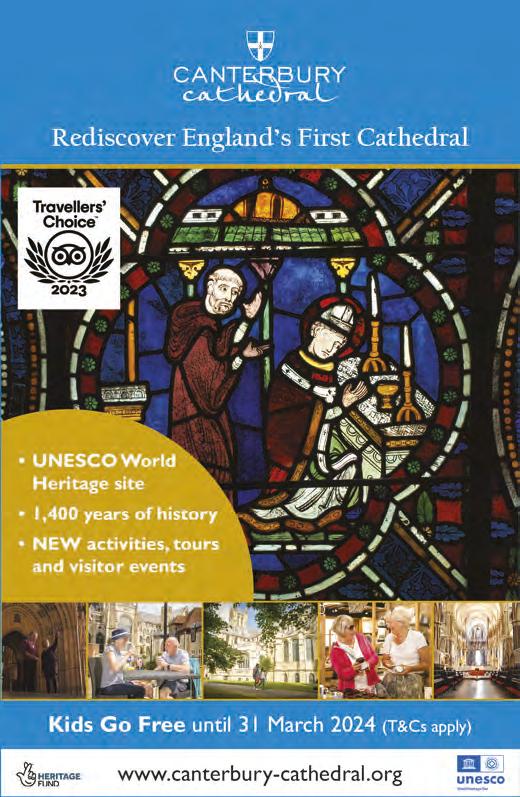

On 16th September, the Anthony Powell Society revealed a blue plaque on the writer’s home at 1 Chester Gate, just off Regent’s Park.

My father, the writer Ferdinand Mount, Anthony Powell’s nephew, said a few words. Also there was his elder son, the film director Tristram Powell. His younger son, John Powell, is Patron of the Society.

Powell (1905-2000) and his wife, Lady Violet Powell, lived at the house from 1937 to 1952. There Powell began his 12-novel sequence, A Dance to the Music of Time. And it was there in 1949 that the Powells’ niece, Lady Antonia Fraser, then 17, came to lodge.

Antonia, now 91, was also at the ceremony at her old home. She moved there from Hampstead Garden Suburb, where her parents, Frank and Elizabeth Pakenham (later Lord and Lady Longford), lived.

Antonia says, ‘I greatly disliked Hampstead Garden Suburb because it was too far out for a boy to take me home in a taxi as it was outside the limit for a normal London cab.

‘I felt this hampered my social life and Violet, who was a very generous and warm-hearted woman, took pity on me. Tristram and John were still very young and I felt very much at home and at the same time free.’

Antonia remembers Powell embarking on his magnum opus.

She says, ‘We used to have breakfast and then came the time which I now treasure, when Violet would say, “Buck up, Antonia, and finish your breakfast. I need to clear the table so Tony can write his novel.” And of course this turned out to be A Question of Upbringing, the first volume of Dance.’

She says, ‘I chiefly remember the need to get out and let him work. This was very different to the situation I had grown up in as my father, who was a don at Oxford, left the house each morning to go and work at Christ Church.

‘So Tony settling down to work

every day at the kitchen table made a great impression on me and I remember feeling that this was a pleasant way to work.

‘I appreciated from being with them how much fun being a writer could be and that it would be a wonderful life for someone who was a compulsive reader, as I was and still am.’

Antonia went up to Oxford in 1950. When the first volume of Dance came out a year later, she became addicted to the sequence. Her favourite is The Soldier’s Art (1966).

Critics rushed to identify real-life people who inspired Powell’s characters, chiefly Kenneth Widmerpool, the crass politician-on-the-make. Frank Longford supposedly nominated himself as the inspiration for Widmerpool.

Antonia thinks not: ‘I never heard him say that and I think it more likely that someone else made that comment, which my father then repeated. I don’t think he was like Widmerpool in the slightest. If there is a character who might have been partly inspired by Father, then I think it would be Erridge.’

In the series, Erridge, a socialist peer, is the brother-in-law of the narrator Nick Jenkins, as Lord Longford was Anthony Powell’s brother-in-law. Still, others (including A N Wilson, see page 37) think George Orwell inspired Erridge.

While Antonia was lodging with the Powells, she was plunged into the heart of literary London. She says, ‘I remember seeing Malcolm Muggeridge at Chester Gate, as

he was a really close friend of Tony’s at this period and lived nearby.’

During her stay in Chester Gate, in 1950, Orwell died of TB. Powell and Muggeridge arranged his funeral at nearby Christ Church, Albany Street.

After Antonia left Chester Gate, she remained in close contact with the Powells. In 1961, she went on a Swan Hellenic cruise with them.

Antonia says, ‘There is a scene in Temporary Kings [1973] featuring a Tiepolo ceiling and, on that cruise, I was actually with Tony when we looked at a Tiepolo ceiling in Venice, so this is a proud memory for me.’

Antonia later invited Powell to a performance of Mozart’s Seraglio in her Holland Park garden.

She says, ‘He asked me what people would normally comment on when they were at the opera. Luckily, I had a review from the Financial Times, which said one character was more of a baritone than a bass but this was normally the case with this character. This comment then appeared in Temporary Kings

‘So I did see then how he would adapt life into his fiction, but also his care in getting things right.’

Antonia’s Oxford tutor, Anne Whiteman, inspired Emily Brightman in Dance: ‘Anne was very proud to have been the inspiration behind the character. This always amused me as Dr Brightman is a bit of a nightmare, being terribly bossy – most unlike Anne.’

The Powells also got on well with Antonia Fraser’s late husband, Harold Pinter. Antonia says, ‘Like Tony, Harold loved literature and the English language was everything to him. And then there was red wine, which they both enjoyed.’

Before Antonia married Pinter, Powell asked her, ‘What is Harold? How do we describe him?’

She said, ‘Well, you can call him my companion.’

Powell said, ‘You mean like an old lady?’

There was a pause and Antonia said, ‘Exactly like an old lady’ – and Powell roared with laughter.

The Oldie October 2023 23

Antonia’s room was by the blue plaque, Regent’s Park

Literary Lives

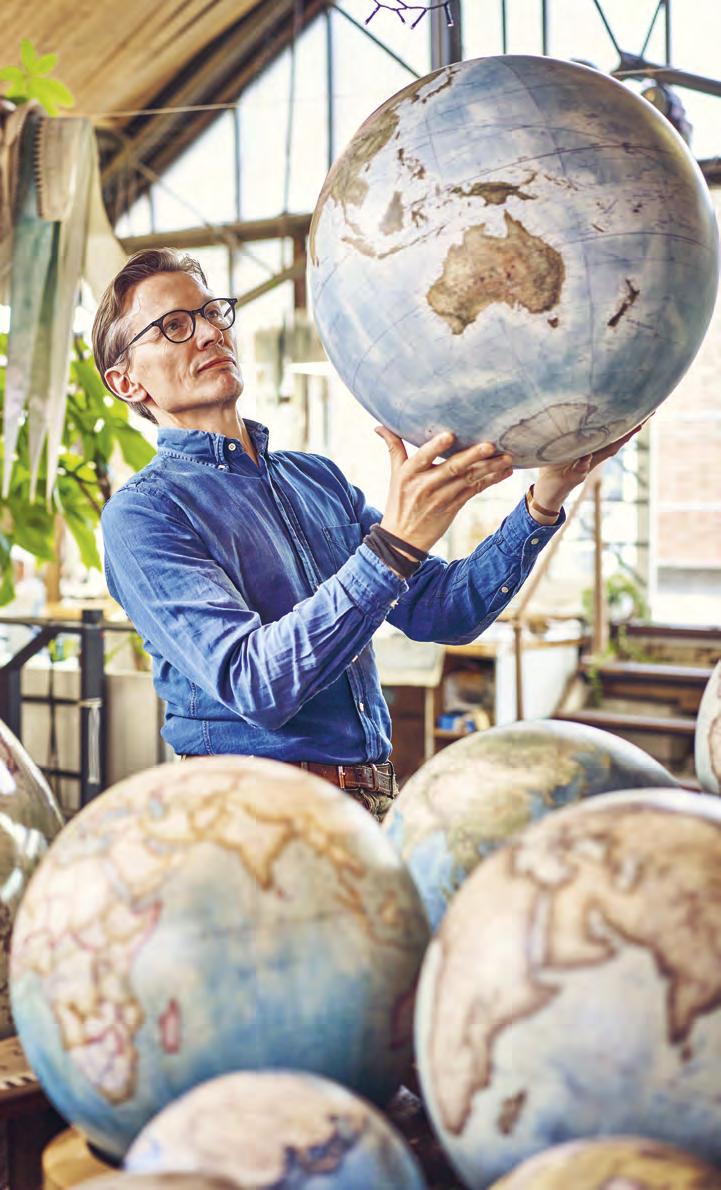

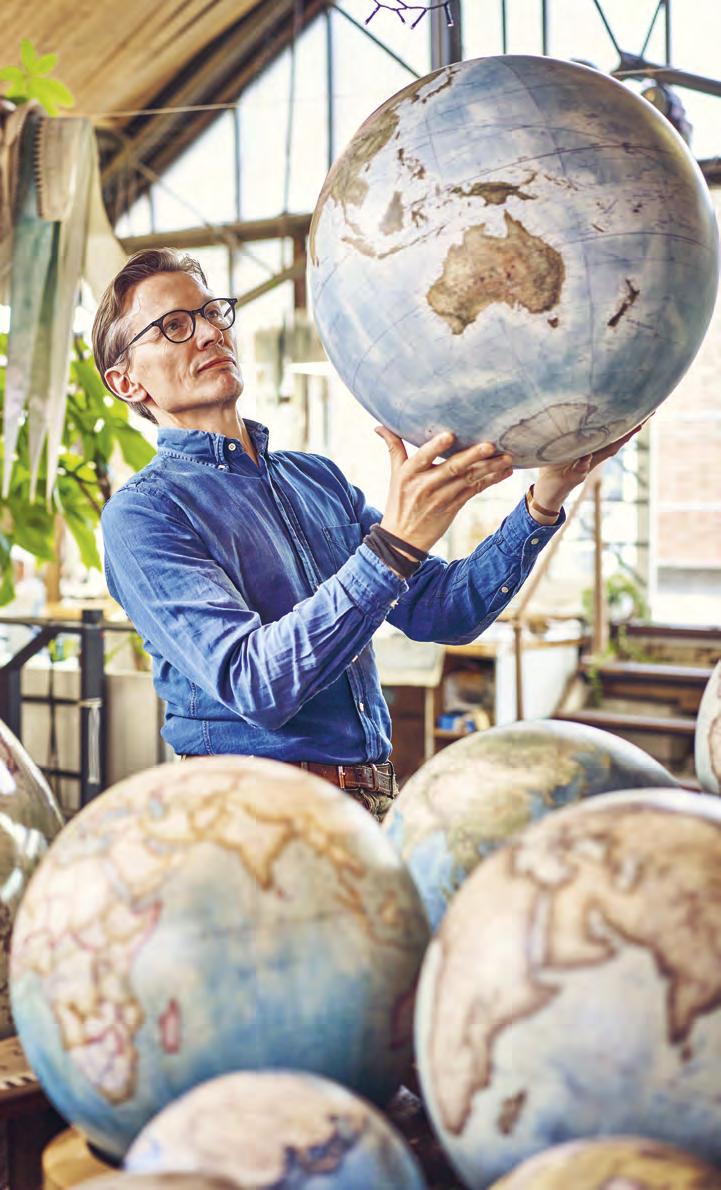

The British Atlas

Bellerby & Co, the only bespoke globemaker in existence, has won the Queen’s Award for Enterprise twice.

The founder, Peter Bellerby, began the business in 2010 after failing to find a special globe for his father’s 80th birthday.

Today, his company makes terrestrial, celestial and planetary globes for customers around the world.

And now he’s written a book to celebrate the world of globe-making.

Left: Peter Bellerby and finished globe

Below: painting ‘gores’, sectors of the curved surface between lines of longitude

26 The Oldie October 2023 EUAN MYLES JUSTIN RATCLIFFE

In his new book, Peter Bellerby, the only bespoke globemaker in the world, reveals his secrets to making the perfect planet

SEBASTIAN BOETTCHER

SEBASTIAN BOETTCHER

OWEN HARVEY

The Oldie October 2023 27

The Globemakers: The Curious Story of an Ancient Craft (Bloomsbury, £25) by Peter Bellerby is out now

Clockwise from above: prepping a sphere before the map is added; pasting on the glue; sticking on the polar ‘callotte’, the last piece of the map; a colour wash is added

EUAN MYLES

EUAN MYLES

Twig lit

As a Twiggy musical launches, Valerie Grove recalls writing the Neasden icon’s autobiography in 1975

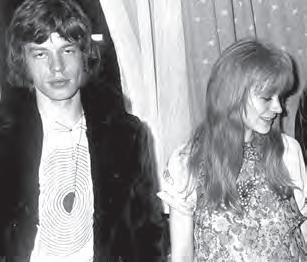

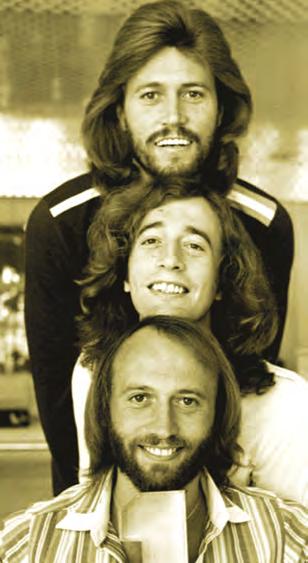

It’s almost 50 years since I became Twiggy’s first ghostwriter. Of course it was Justin who brokered the deal. Justin de Villeneuve (né Nigel John Davies from Edmonton) was no longer her Svengali/boyfriend, but he was still running ‘Twiggy Enterprises’.

Her autobiography would be a slim volume, we joked. All royalties would go to Twiggy Enterprises (sadly for me, as the book, Twiggy by Twiggy, 1975, did rather well).

She was three years younger than me and three stone lighter. We knew the same London suburbs, we’d bought the same black, lace-trimmed frock at Biba in 1964 (for £3), when I was doing A-levels and she was at the Fender Club in Harrow in her Mod gear: Hush Puppies, white lipstick, kohl-rimmed eyes.

One day, Justin took her to Leonard of Mayfair to have her hair cut into that gamine blonde cap. The Daily Express photograph was captioned ‘This is the face of 1966’: an instant icon in an icon-mad decade.

When we met in 1974, Twigs was about to play Cinderella at the Palladium that Christmas, singing her heart out in a small, true voice. And she had a new boyfriend. She’d ditched unfaithful Justin for a hulking American B-movie actor 20 years her senior, Michael Witney, her leading man in a forgotten film from 1971 called W. When I arrived at their gloomy mansion flat in Cornwall Gardens, Witney was usually still in bed.

She told some funny stories, quite artlessly. She’d once been seated at dinner near Princess Margaret, who had asked who she was.

Twiggy: ‘My real name’s Lesley Hornby but most people call me Twiggy.’

HRH: ‘How unfortunate!’

On American TV, Woody Allen asked the teenager, ‘Who’s your favourite philosopher?’ She replied, ‘What’s a philosopher?’ and he was the discomfited one.

And when her mother in Neasden, surrounded by reporters, was asked, ‘Has

your daughter’s success changed your social life, Mrs Hornby?’ she replied, ‘Well, I’ve joined the Conservative Party!’

Twigs had total recall about everything she’d worn, and an infallible instinct for upcoming trends, like catsuits, which she made herself.

Justin fleshed out the racontage. He’d been a likeable Jack-the-lad sort of villain when he spied the waif-like Twiggy and her huge blue eyes. When she was catapulted into the headlines by photographer Barry Lategan and fashion editor Deirdre McSharry, Davies reinvented himself as Justin de Villeneuve, Svengali to her Trilby, guarding her from paparazzi who called him ‘that creep’.

Soho was Justin’s manor, Flash Harry his style. Son of a bricklayer, he’d been a bouncer at a Wardour Street clip joint, ‘Tiger Davies’ the fairground boxer, and ‘Mr Christian’ the shampoo boy at Vidal Sassoon. He’d dealt in bogus wine labels, blue movies, market-stall antiques. He kept quiet about being already married.

The couple were boracic (lint: skint) and at the start had to borrow their bus fares, but Justin had the rabbit (and pork: talk). He knew that if he said Twiggy earned a grand an hour, people would pay that. Ford gave her a Mustang, years before she could drive.

New York and Hollywood went wild to welcome them. When they flew back from Japan in 1967, Justin’s old barrow-

boy friend Teddy the Monk hefted £100,000 through Heathrow in a suitcase. Which kept Justin in multiple Porsches and Tommy Nutter suits –he got his taste for posh stuff when evacuated to J B Priestley’s house during the war – and the pedigree dogs he never managed to housetrain.

Wherever the couple went, stars flocked to meet them – Tony Curtis, Tommy Steele, Lauren Bacall, Sonny and Cher. In Jamaica in 1970, Noël Coward told Twigs she’d be marvellous in his early plays. He said she should definitely do The Boy Friend film with Ken Russell. Which Twiggy did in 1971. She danced her socks off, won two Golden Globes, went to Hollywood for the premiere and met her hero Fred Astaire.

The last words in our book were:

‘I’m 26 now. That means I’ve had a decade of being Twiggy. They’ve been ten amazing years. I don’t think I could ever have envisaged any of it happening. What people never understand is that I come from a sane, ordinary background and I’m sane and ordinary – and lucky.’

So ended Chapter One of her life. In 1977, she did marry Michael Witney, father of her daughter, Carly. But Witney turned out to be an unreformable alcoholic, who died in 1983, aged 52, of a heart attack in McDonald’s.

Almost 50 years on, Twigs is lovable Dame Twiggy. For three generations, Twiggy has been a household nickname.

In 1988, she married her good man, the actor Leigh Lawson, ex-husband of Hayley Mills. Ben Elton has now written up her early life in a new musical. Twiggy turns 74 as the show opens. Justin is 84 – and I’m agog to know who will play him. Twiggy told her second ghostwriter, in 1997, that he was just ‘the lad who got lucky for a time’. Which is true.

On the other hand, without Nigel Davies, her early life story could have been Cinderella without the Prince.

Close-Up: The Twiggy Musical, Menier Chocolate Factory, from 18th September

The Oldie October 2023 29

What a Dame! In The Boy Friend (1971)

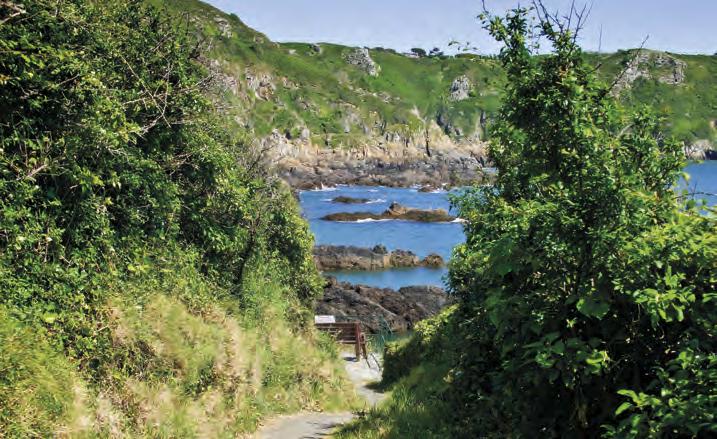

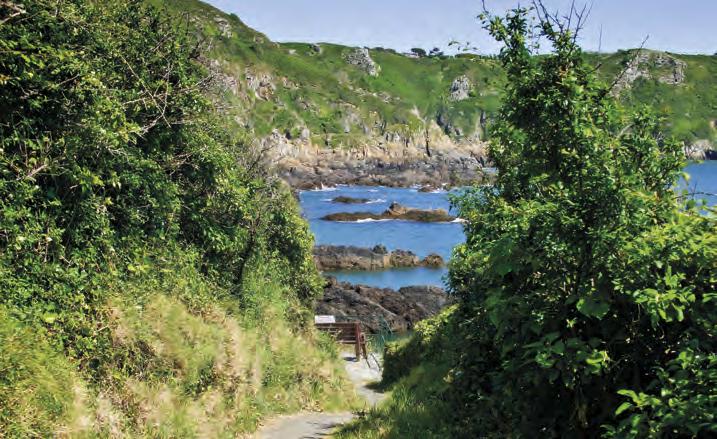

Sasha Swire walks the windswept, wave-battered South West Coast Path, home to Butlin’s and solitary bird-watchers

Life on the edge

The journey I describe in my new book is one that is deeply familiar to me: the South West Coast Path.

It is a linear journey, which blows westward and then turns east, following, for 630 miles, the contours of natural borders.

My journey started at Minehead in Somerset, clambering up North Hill to a gorse-tangled plateau, and from there travelled through three counties, finishing in Poole in Dorset.

It passed through big towns, small towns, villages and hamlets; even wilderness. It wove between gone worlds that have risen and dissolved. It offered artistic associations and rocks that are more durable than the gathering of heavens. It gave me freedom on blond beaches under blue skies, and God over saint-wooed ground.

When I started walking, I was not seeking a lucid understanding of an edge world; just eco-therapy, as respite from the stresses of my job in an urban existence. I came where many people come, to the line between land and sea. I just wanted to add my feet to the current of a coastal path looking seaward.

As I sauntered along, on and off over a ten-year period, I became increasingly charmed, even enthralled, by the sheer level of expressive forces at work on the fringes.

What I discovered was the edge is where the action is; not the surface.

Minehead to Porlock

The hills have eyes.

What must they have seen from this protrusion of Exmoor that rises beside a town looking out to sea? The English seaside as its port declines: quay town houses turned to boarding houses, steamships, bathing machines, a steam train, ice-cream parlours run by Italian immigrants.

There are amusement arcades, a theatre, a cinema and concert hall, and

a pier. In the 19th century, polo ponies were exercised on the beach. In 1874, the railway brought even more summer visitors. Hotels were built and more shops opened. Then, in the 20th century, stiff competition from resorts abroad meant a chill wind blew on these seaside resorts.

Poor transport links, an ageing population and low expectations ensured that Minehead will spend the next decades running to stand still. It is another story about the near and the far

away. Of other places and other worlds.

I am on North Hill, at the start of my walk. Rising 900ft from the sea, the hill hovers over the town in a friendly fashion. I am on rare coastal heathland. Among gorse and bracken, bell heather and ling, I have clear views across the Bristol Channel. Somewhere below me, although I cannot see it from here, spread out before the sea, lies that which Minehead is reliant on for its economic health: Butlin’s holiday camp, the largest employer in this small coastal town.

30 The Oldie October 2023 ANDREW HAYES / ALAMY

Its founder was a rogue called Billy Butlin. Billy looked like a diminutive Rhett Butler and behaved like one, particularly with women; he was an archetypal edgeland character.

Born of fairground stock, he acquired his business acumen ducking and diving between the gingerbread stalls and toffee-apple barrels, flirting with the punters and learning where and when to use his animal charm.

His first pitch was a hoop-la stall, his prizes cheap rewards, chocolate and dyed wrens passed off as canaries.

From there, he moved on to operate a string of arcades, amusement parks, fairground pitches and zoos all over the country. For one who bobbed and weaved, it is appropriate that his early fortune came from importing dodgem cars. A natural gambler, he borrowed heavily to set up his first holiday camp in Skegness in 1936. Many more would follow as his business boomed after the war. The camp in Minehead opened in 1962, and flooded the area with 30,000 people in its first year alone.

The Minehead camp was built on

former grazing marshes, with a trench around the perimeter to keep the sea out. It is a story of enclosure: enclosing the British holidaying public in their masses. As a painting exists within a frame, the same could be said of a holiday camp.

Billy Butlin became Britain’s seaside ringmaster, the significant performer in his own big tent show, directing the audience’s attention and producing a seamless performance. He was bigger and better than anyone else in the pleasure-dome world.

Billy came to an edge in the natural world and created another artificial one, a cultural one, and in doing so changed the coastal topography of Britain for good.

On this, my first day of walking, I come to Hurlstone Point. There is a birdwatcher with his binoculars raised, standing lonely at the sharpness of the edge. ‘What can you see?’

He reels off a list: falcons and wheatears, stonechats, ring ouzels and black redstart. He tells me a wide array of birds hover over this point and adds that Hi-de-Hi! Butlin’s, Minehead, opened in 1962

it’s an excellent time of year to watch them, because the migrants are flying overhead on their journey to Africa.

He comes to this location because it is where the earth retreats and he has room to move outwards, further and further away from the near space in which he resides.

And it is not an uncommon sight, solitary men obsessed by birds, in this border territory.

I have a theory: that birdwatching in men comes from the dark corners where the conflicts with hunting and hurting reside.

Man’s whole narrative has been of escaping the wild, suppressing his savage and primal instincts: one of moving towards civilisation, away from caveman conditions towards hearth and home. But I wonder if there is still something beating in his heart from that time –some residue?

This intense viewing of species and behaviours, understanding the intricacies of their world, is like any great hunting or military operation; it takes careful planning and thinking.

On 29th October 1942, a long-range bomber was flying low like a big homing pigeon over this swampland, having completed a mission against German U-boats in the Bay of Biscay. It was returning to its base at Holmsley South Airfield in the New Forest and, like the bird itself, was following the grooves and hollows of valleys and seas, flying low to evade hawks and harassers.

Because of heavy rain and poor visibility, it clipped the top of Bossington Hill, which was in low cloud, and swung westward over Porlock, debris falling from the stricken plane.

A wheel and part of the undercarriage plunged on to Sparkhayes Lane before its carcass dropped heavily into the marsh, killing 11 of its 12 American crew. The airmen’s memorial, which has been moved from its original site on to the footpath so more people can see it, is made from the remains of the aircraft.

When people die like this, slipping between different realms, they become ghosts where they fall and that is how they stay alive with all that is already there. After all, what goes on here is otherworldly, ethereal, fluid; those native to the marsh already brave and longing to forget and smouldering through time.

It truly is a land fit for heroes. A place of desperate reaching.

The Oldie October 2023 31

Sasha Swire’s Edgeland – A Slow Walk West (Hachette) is out now

Dad’s Salerno elegy

Eighty years ago, Richard Oldfield’s father wrote a heartbreaking tribute to two comrades, killed in battle

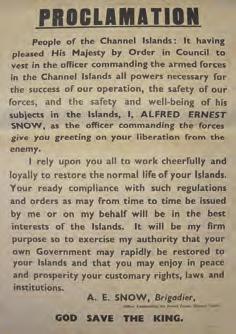

The 9th of September marked the 80th anniversary of Operation Avalanche, the Allied landings in Italy near Salerno.

My father, Christopher Oldfield (1921-81), fought in the Italian Campaign. He had two years at Oxford before joining the Grenadier Guards in 1942. In 1943, he was sent with his battalion, the Sixth, to North Africa and thereafter to Italy. He was wounded twice, once in North Africa and once in Italy.

During lockdown, I found in tin boxes half a dozen exercise books full of the poems, essays and short stories he wrote, all in pencil, while at war, and the letters he sent to his aunt. He was very close to her, both his parents being dead.

He wrote to her, ‘I can tell you nothing of where I am or what I have been doing … I wish I could say something that would make my letters to you a little more interesting, but I’m afraid the censor wouldn’t let the little bit of news that might amuse you through.’

His own internal censor suppressed almost all indication of the beastliness of war. The worst moments in Italy are described dismissively: ‘a bit uncomfortable’, ‘not very pleasant’, ‘not feeling very lively’ and, after being wounded, ‘a slight headache’.

Among the topics to which my father instead resorted, somewhat Pooterishly, are injections for his aunt’s rheumatism and the hope that they will be successful, the fact that his niece can write in block letters, the difficulties of finding someone to mow the lawn and of feeding the hens in the rain. Thanks for socks that his aunt has sent and his search for gloves for her are recurring themes.

The essays were light-hearted and witty, in the style of Max Beerbohm whom he revered. The poems were morbid and cynical.

One of the exercise books was secondhand, still containing at the back some jottings in Italian by a schoolboy who must have been its previous owner. At the front, there were half a dozen

poems written by my father in 1943 in Italy. The last of these poems was entitled In Memoriam:

So, two more gone; different in all else, But similar in this, that both were friends

Of mine. To vilify the fate that bends Us as it wills, whether we will or no, Were useless. Better far to acquiesce In silence stern, and by that silence show We serve with dignity our country’s ends.

’Tis useless to wish back the days that were, And worse still to remember and complain, For memory perpetuates the pain. Two friends of mine –Thank God for them; and yet They’re not the only dead, by any means. Just two more gone; it’s easy to forget –Of course it is – nor think of them again.

What matter two among ten thousand dead?

A hundred friendships vanish in a day. Need they? But what use questions? We obey.

Humane, sane logic is a wondrous thing, Jove’s gift to humans – but of no great use To puppets dancing on Bellona’s string. Accept things as they are, and turn away.

December, 1943

On the first page, like the rest of it in pencil, my father had written and then crossed out ‘Dedicated to IMB and PA’. He replaced this with: ‘Dedicated to two officers of His Majesty’s First or Grenadier Regiment of Foot Guards of whom one was killed in action near Battipaglia and the other died of wounds at Salerno during the month of September 1943.’

It does not take more than a couple of minutes with Nigel Nicolson’s The Grenadier Guards 1939-1945 and with the internet to penetrate the anonymity of this dedication. IMB was Captain Ian Moncrieff-Brown.

His nephew is the journalist Craig Brown, who responded when I sent him a copy of this poem: ‘ That’s so fascinating, and moving, too. Ian was my father’s older brother, and was quite wild and dissolute before the war: he went to Cambridge (I think) and did no work but just had fun, keeping on changing his courses so he could prolong the experience.

‘My grandfather then wouldn’t let my father, who was a much more dutiful character, go to university as he didn’t want to waste any more money

‘At some point after the war had begun, the two brothers had a terrible argument and were on non-speaks.