My Turkish Odyssey – Don McCullin The tragic fall of Truman Capote – Nicky Haslam 60th anniversary of the Great Train Robbery – Duncan Campbell Larry Grayson at 100 – Christopher Sandford Shut that door! September 2023 | £5.25 £4.13 to subscribers | www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 430 JE T’AIME – JANE BIRKIN BY SIMON WILLIAMS ‘The Oldie is an incredible magazine – perhaps the best magazine in the world’ Graydon Carter SHOEHORNS MARK PALMER I

Features

Save

See page 31

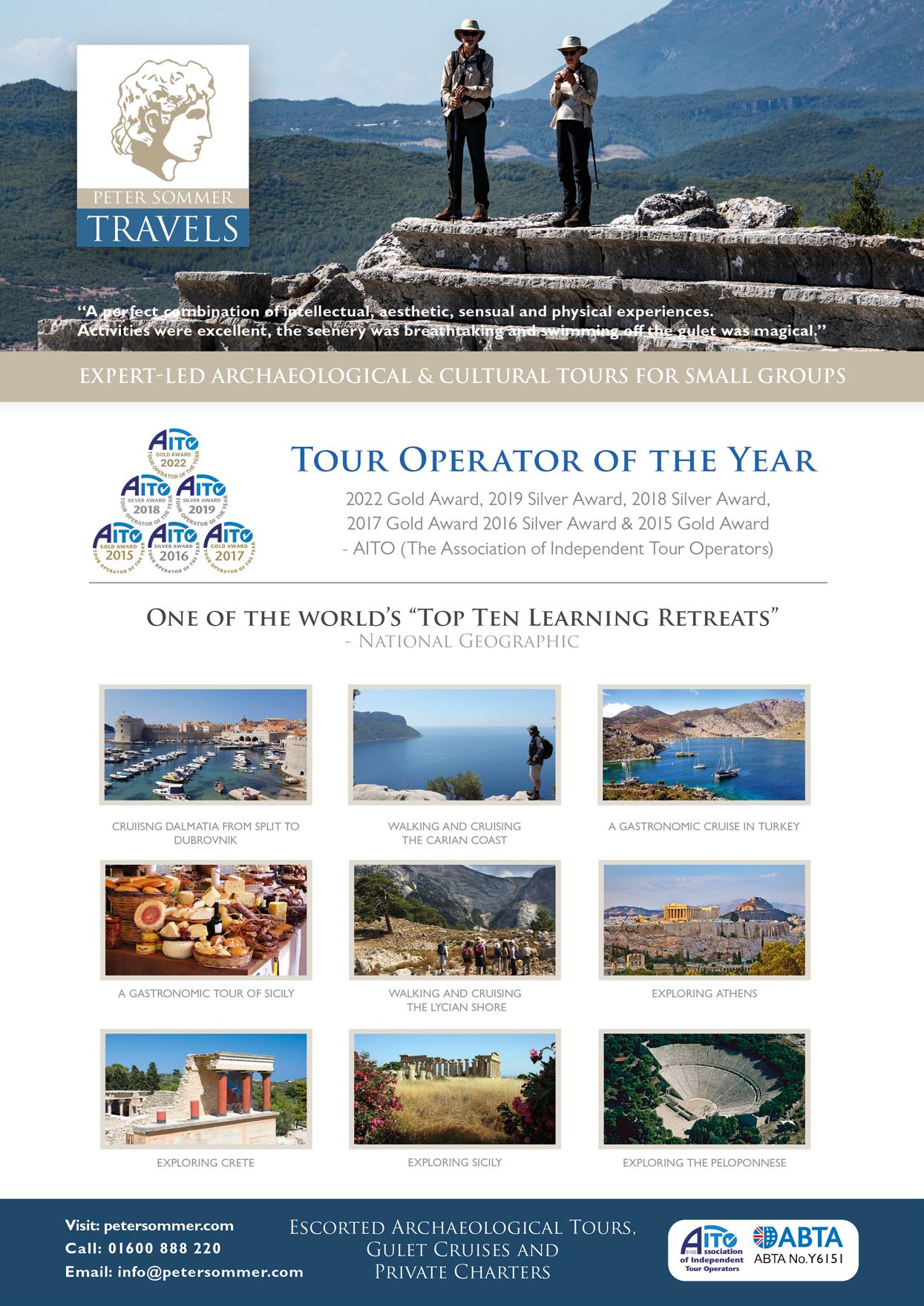

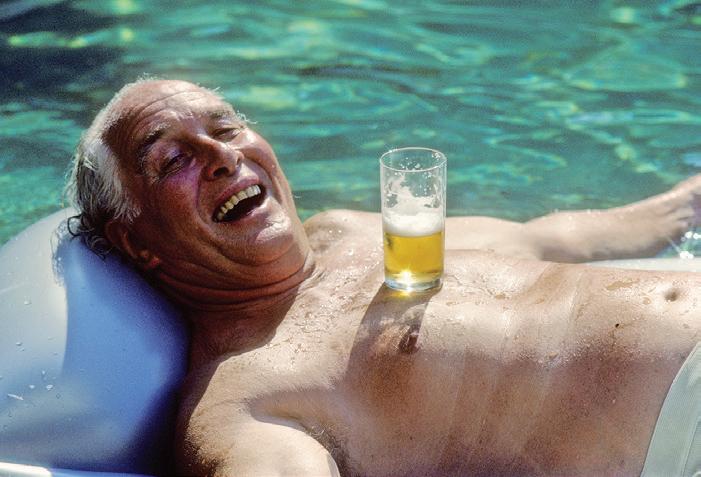

Brazil nut: Ronnie Biggs page 34

Books

54 Capote’s Women, by Laurence Leamer Nicky Haslam

55 Turning Over the Pebbles, by Mike Brearley Paul Cartledge

57 The Maverick: George Weidenfeld and the Golden Age of Publishing, by Thomas Harding Mark Bostridge

59 Vienna: How the City of Ideas Created the Modern World, by Richard Cockett Benedict King

61 Jane Austen’s Wardrobe, by Hilary Davidson Philippa Stockley

63 The Dangerous Life of Diogenes the Cynic, by Jean-Manuel Roubineau

Thomas W Hodgkinson

Arts

66 Film: The Great Escaper

Harry Mount

Regulars

Editor Harry Mount

Sub-editor Penny Phillips

Art editor Jonathan Anstee

67 Theatre: La Cage

aux Folles William Cook

67 Radio Valerie Grove

68 Television Frances Wilson

69 Music Richard Osborne

70 Golden Oldies

Rachel Johnson

71 Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu

Oldie subscriptions

Pursuits

73 Gardening David Wheeler

73 Kitchen Garden Simon Courtauld

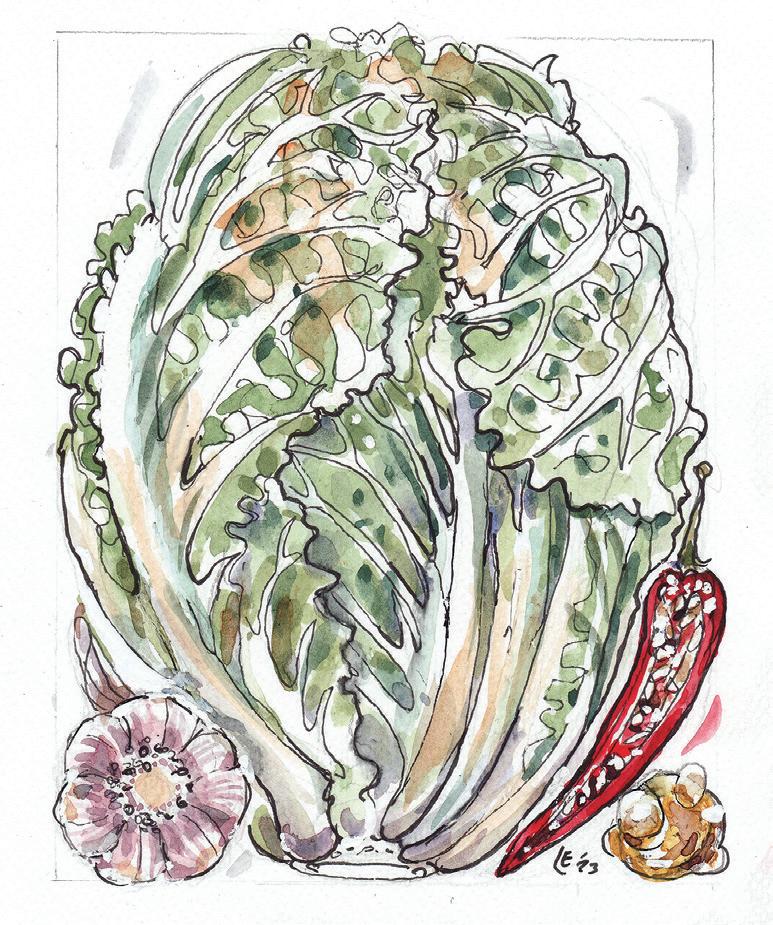

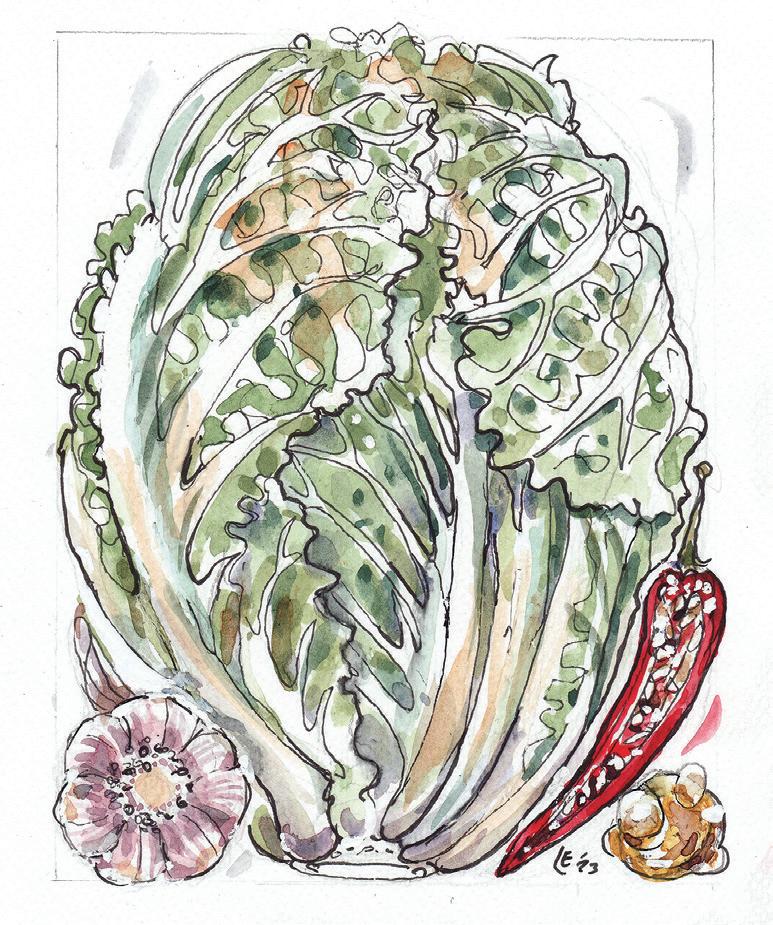

74 Cookery Elisabeth Luard

74 Restaurants James Pembroke

75 Drink Bill Knott

76 Sport Jim White

76 Motoring Alan Judd

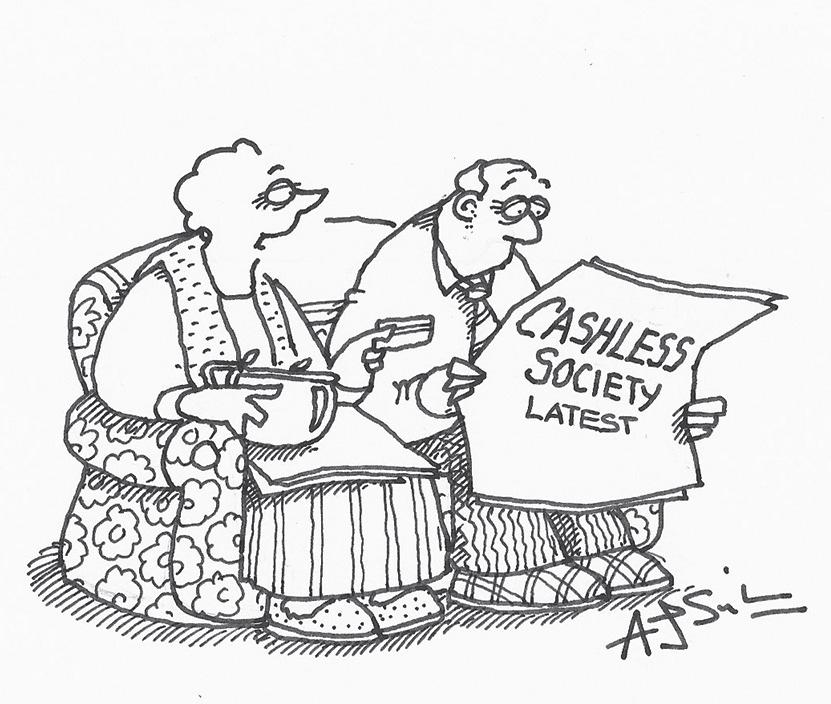

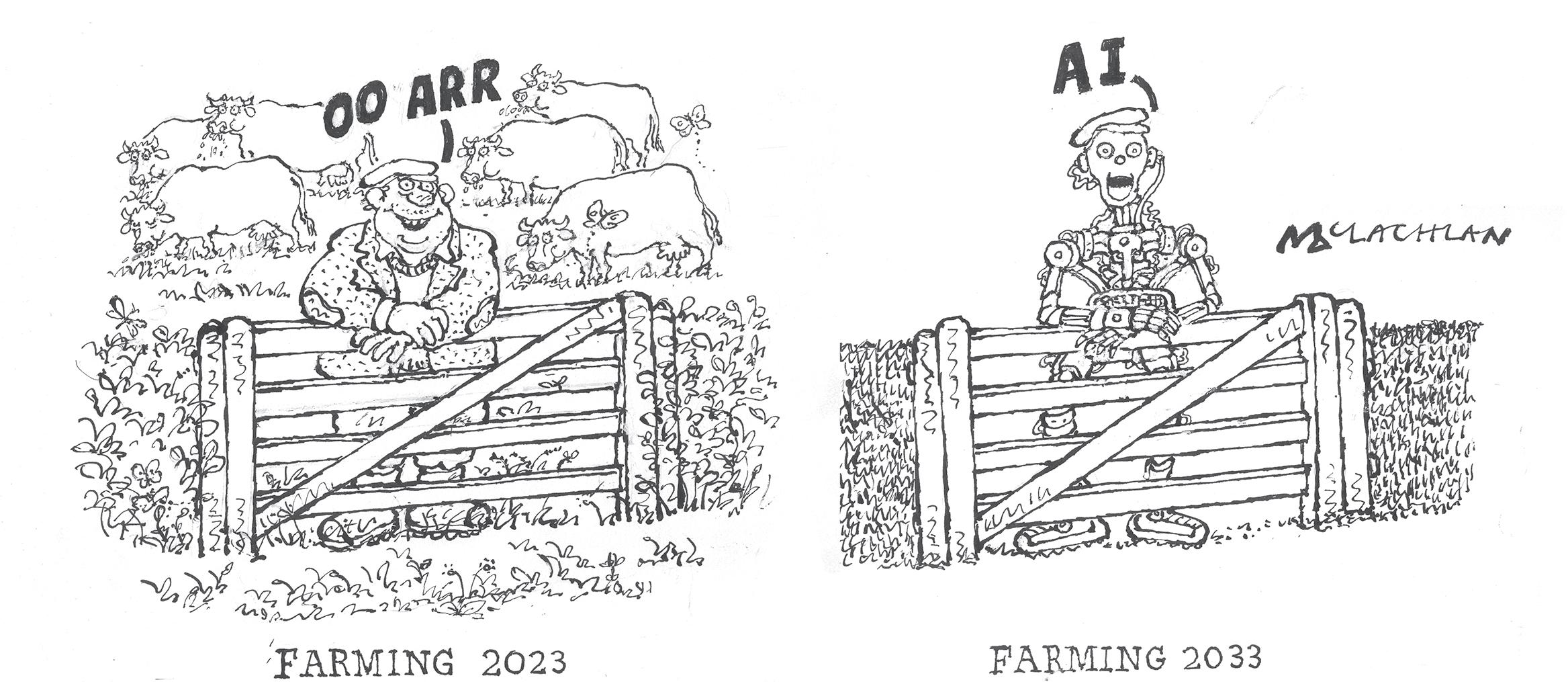

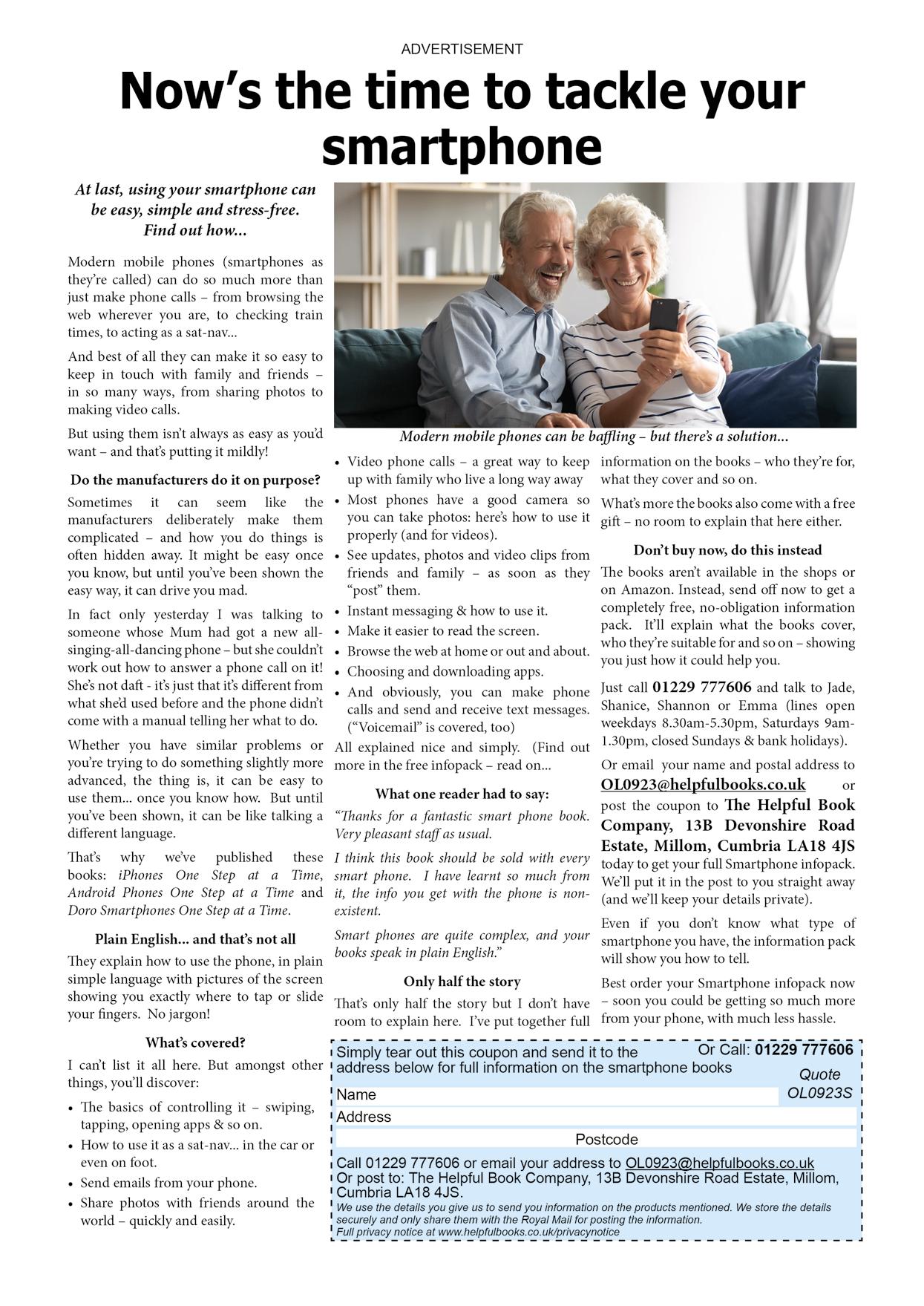

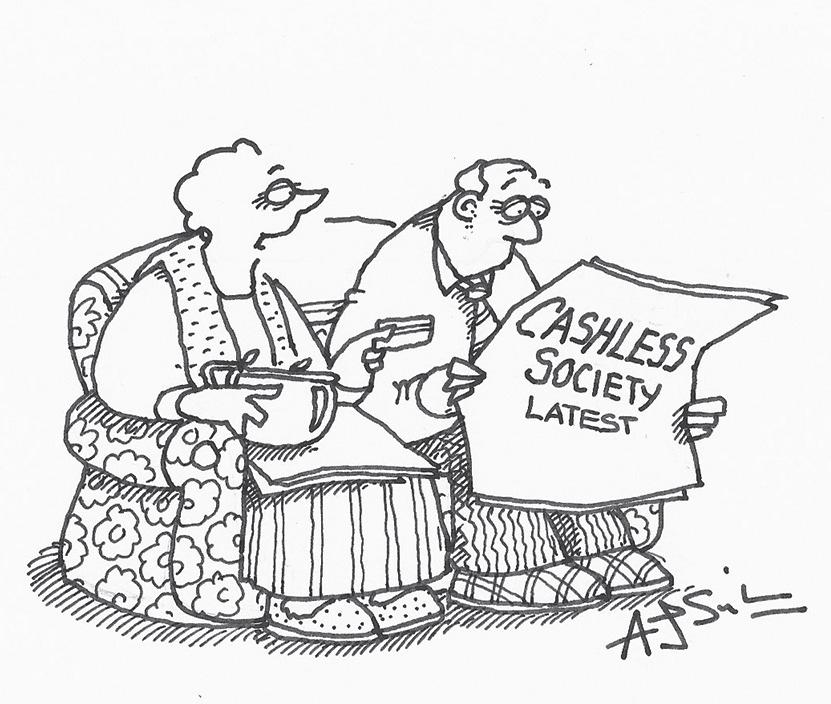

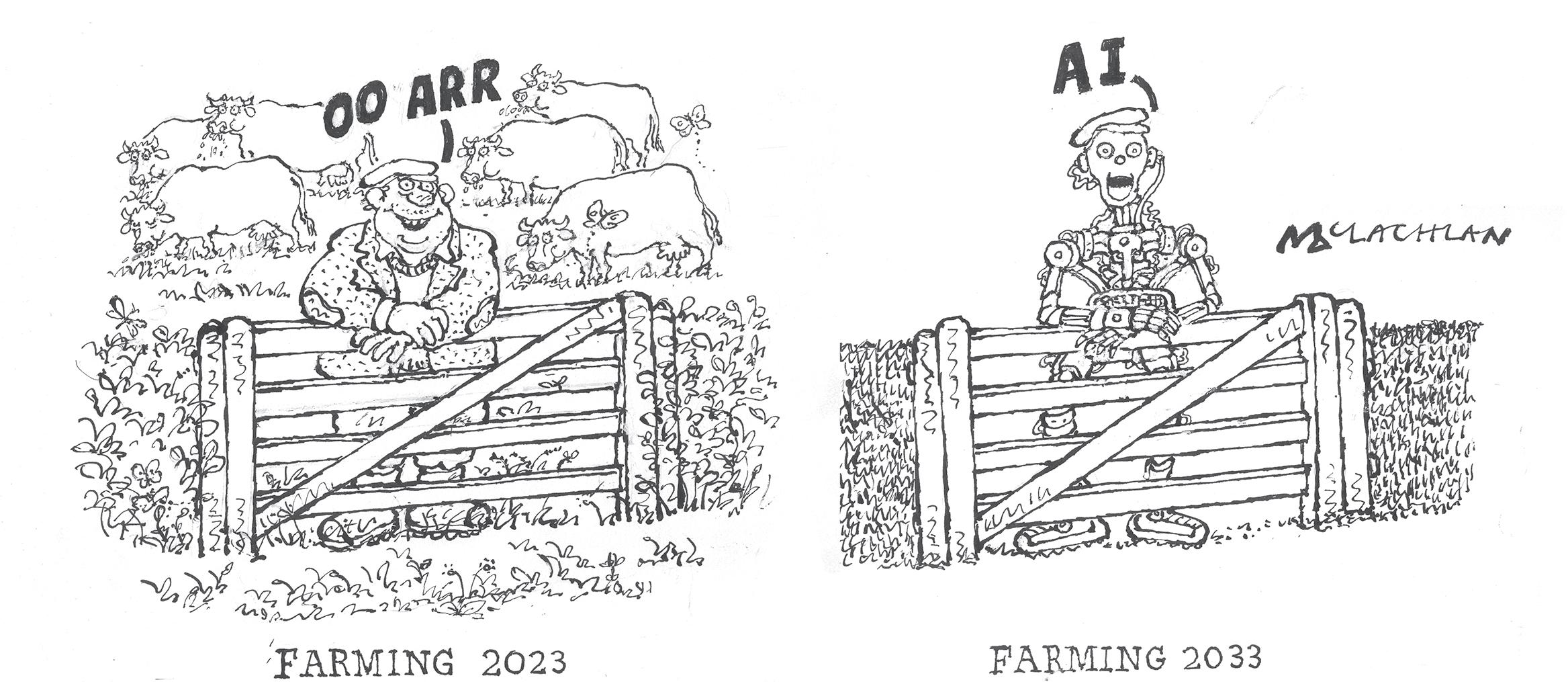

78 Digital Life

Matthew Webster

78 Money Matters

Margaret Dibben

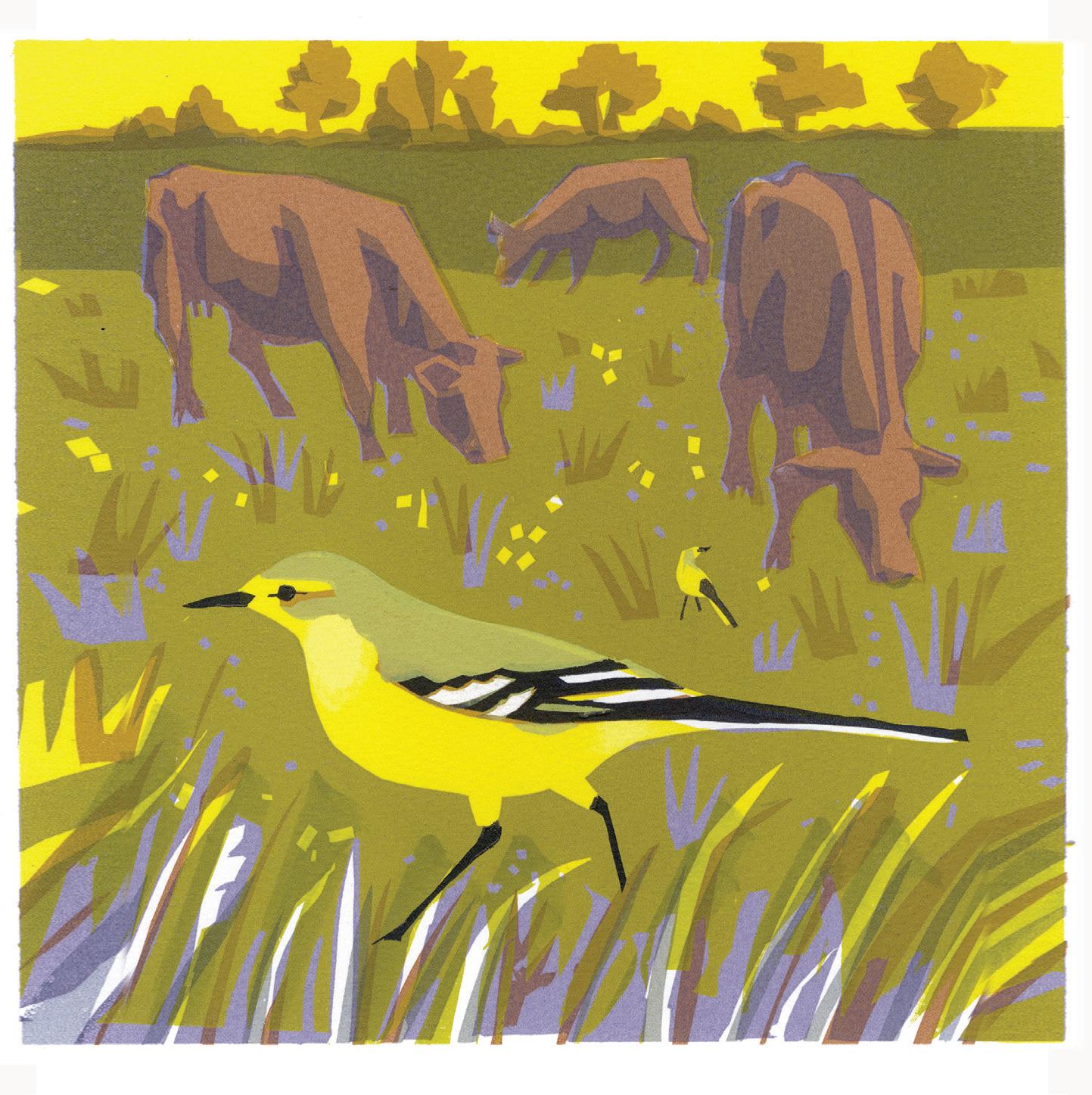

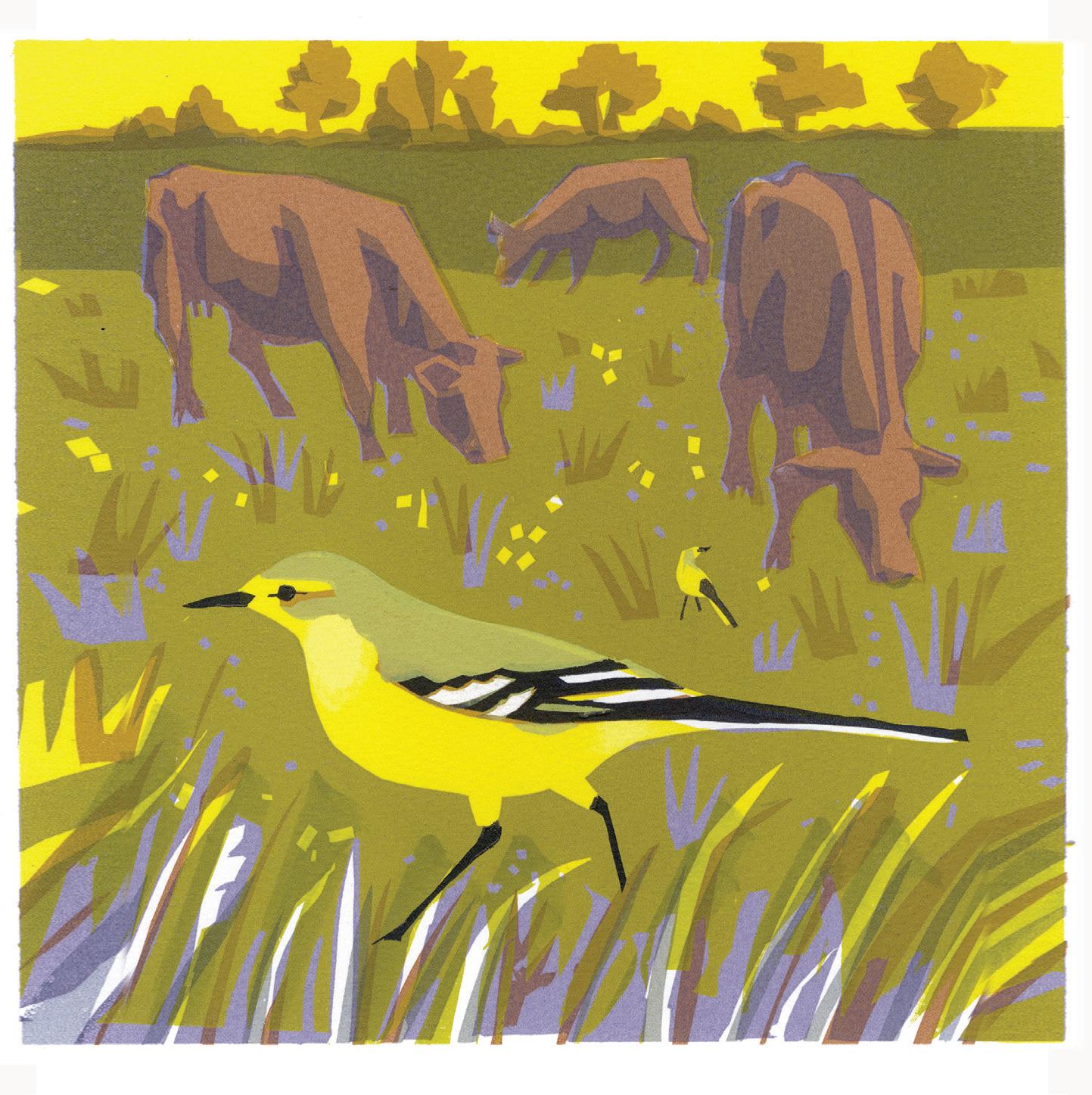

81 Bird of the Month:

Yellow wagtail John McEwen

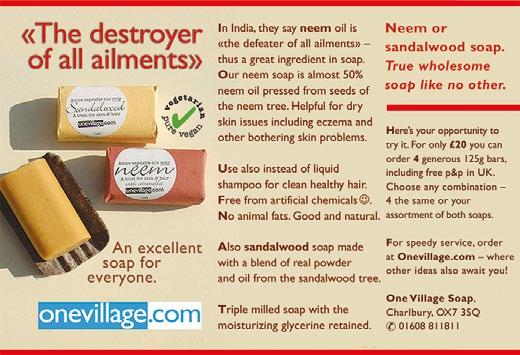

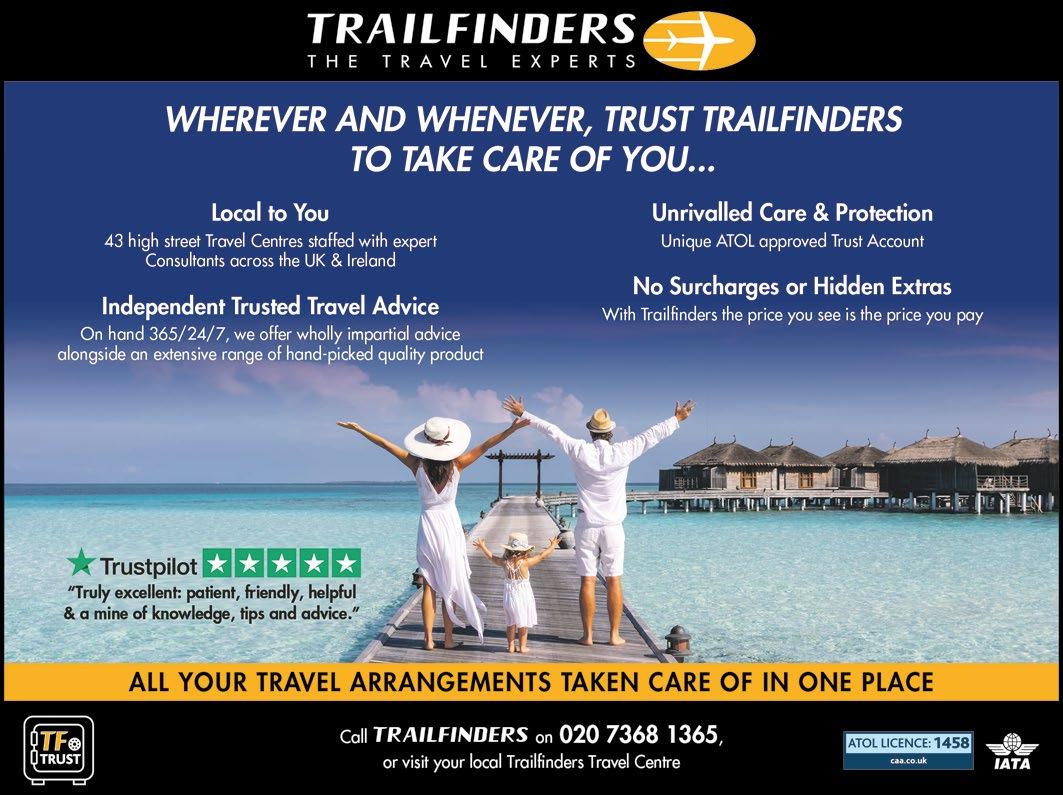

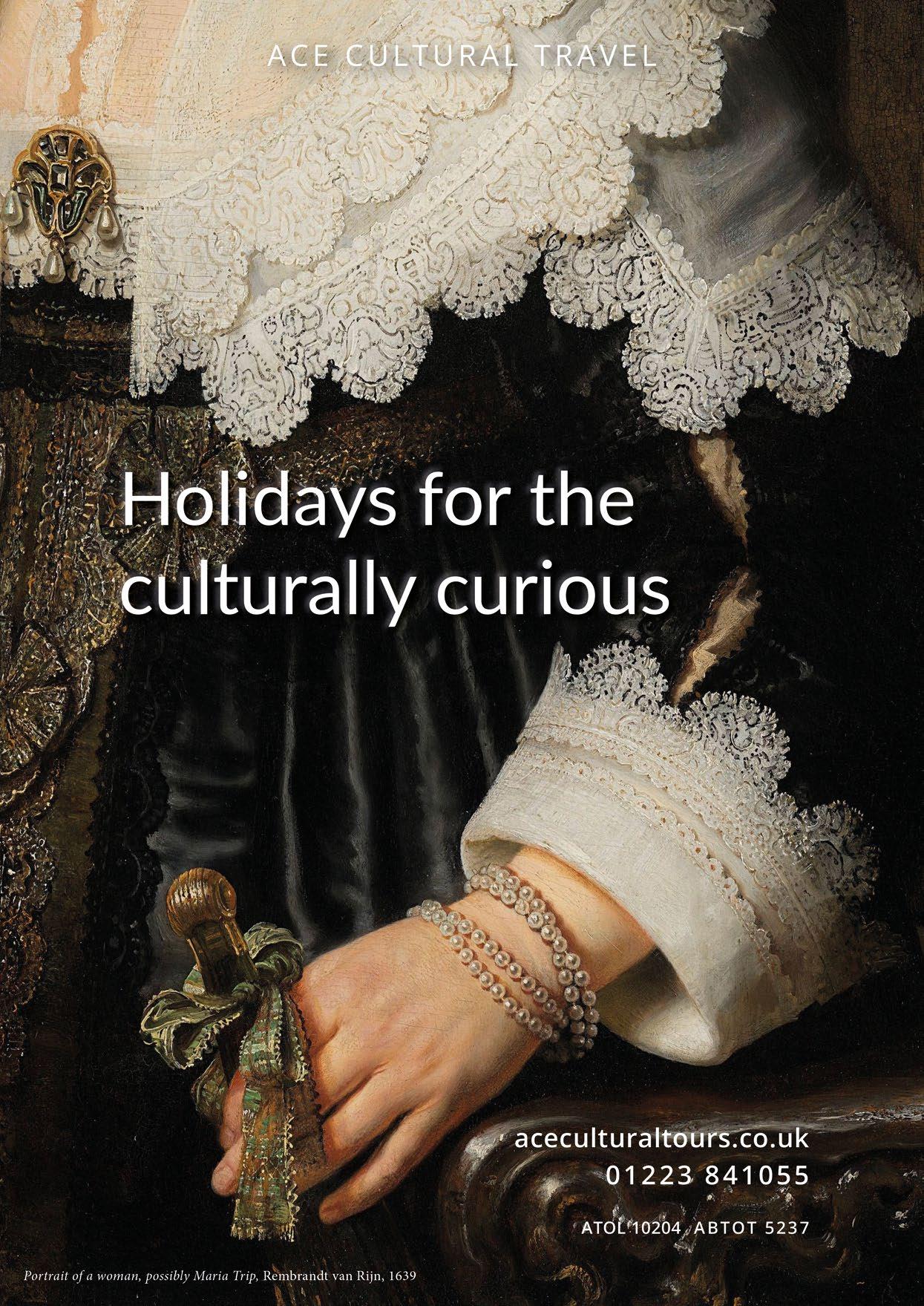

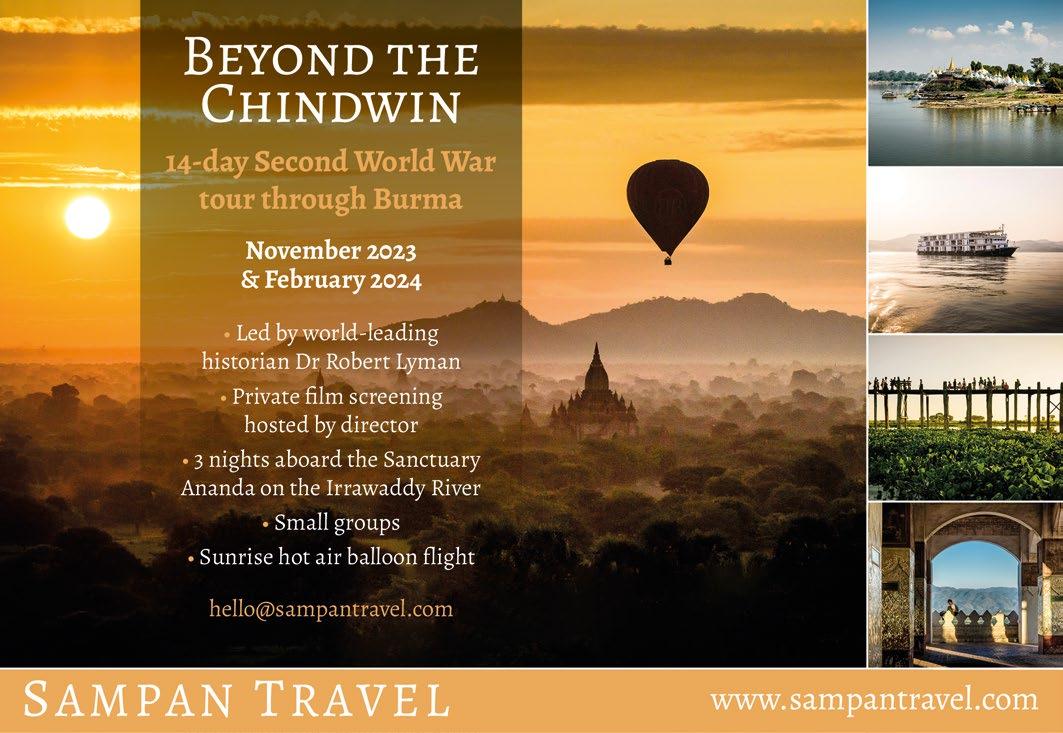

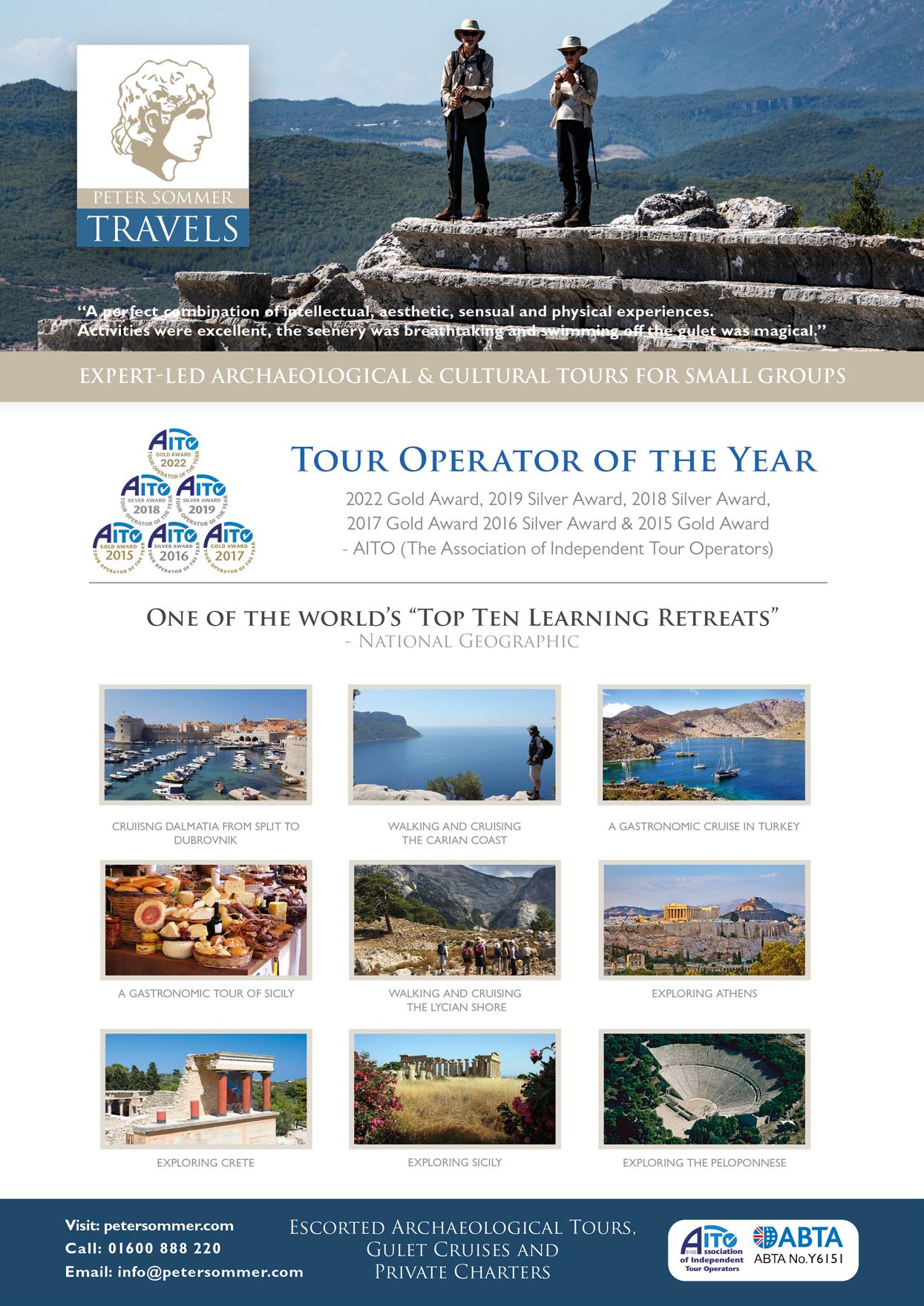

Travel

82 Down Sussex way

William Cook

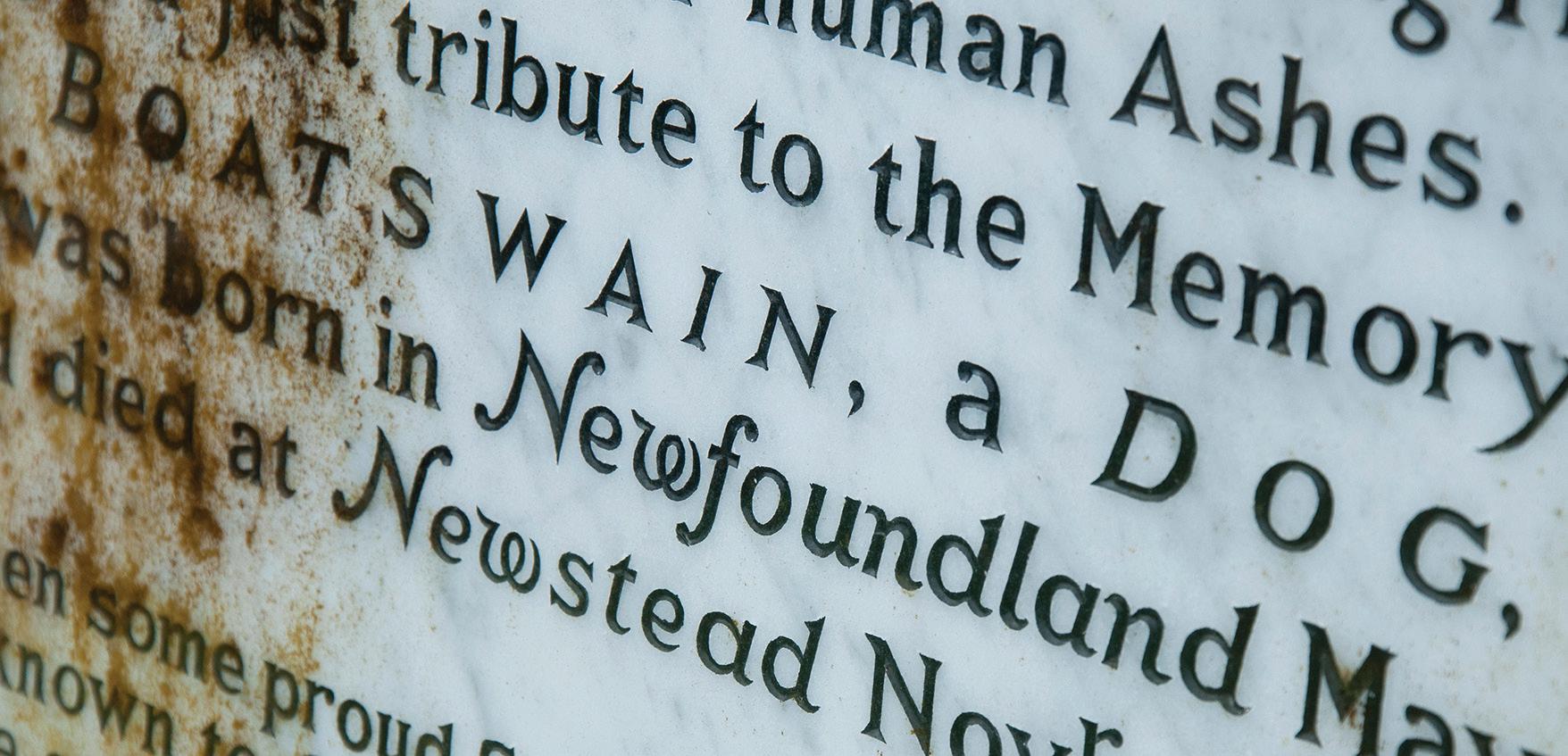

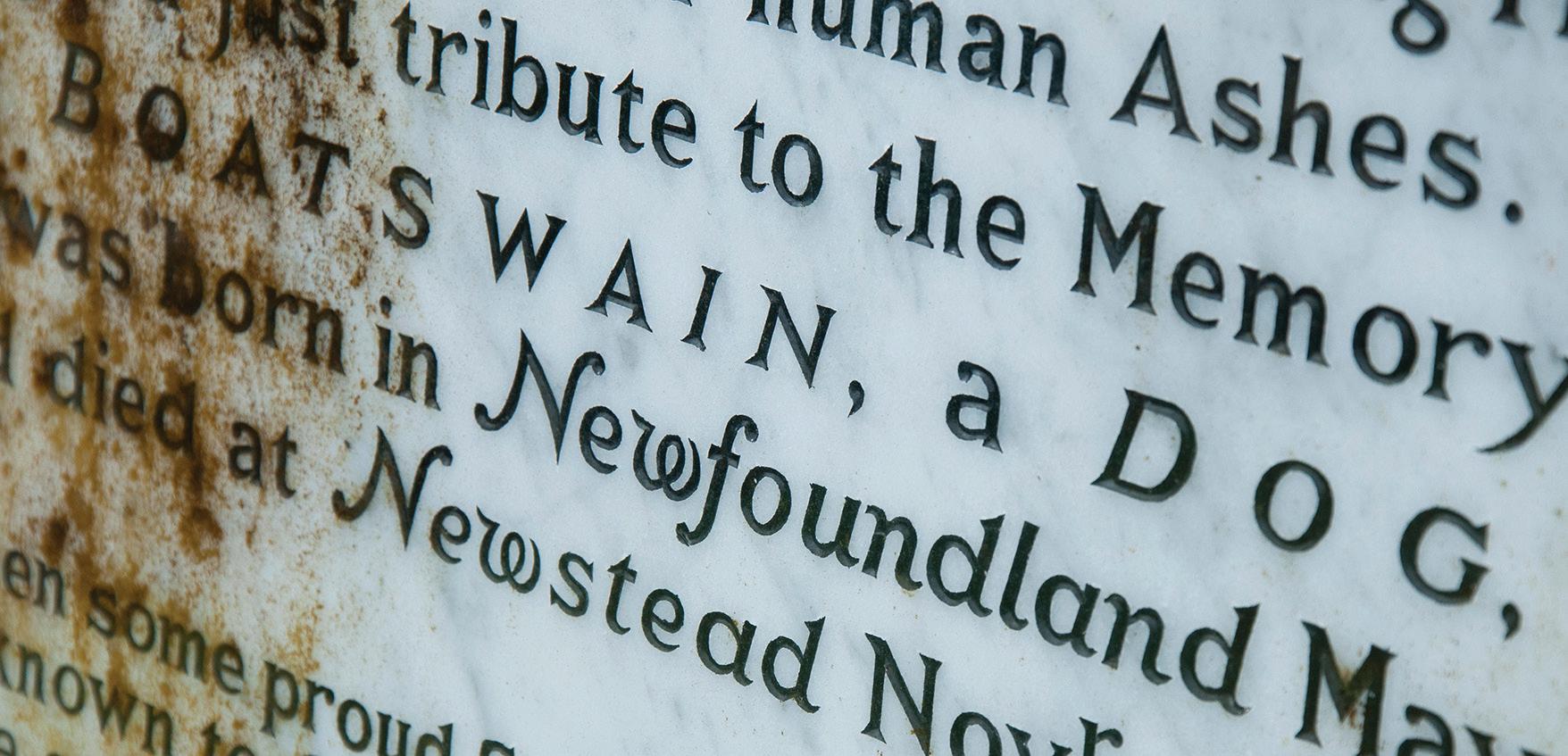

84 Overlooked Britain: Byron’s dog

Lucinda Lambton

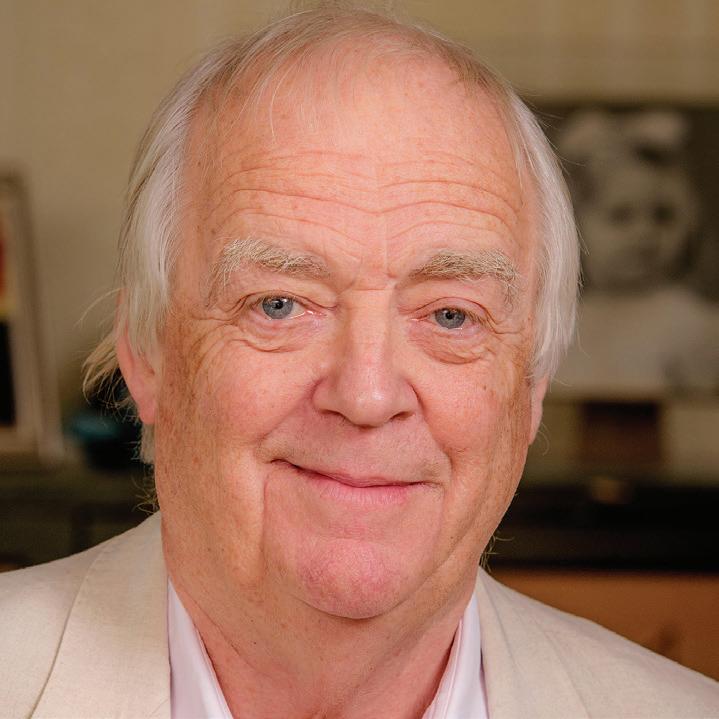

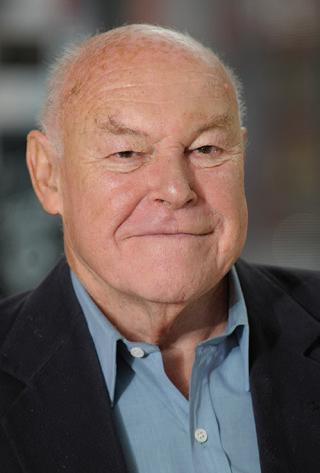

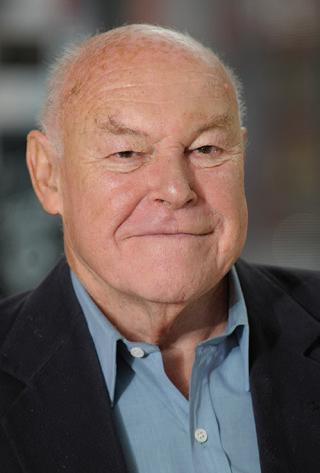

86 On the Road: Tim Rice

Louise Flind

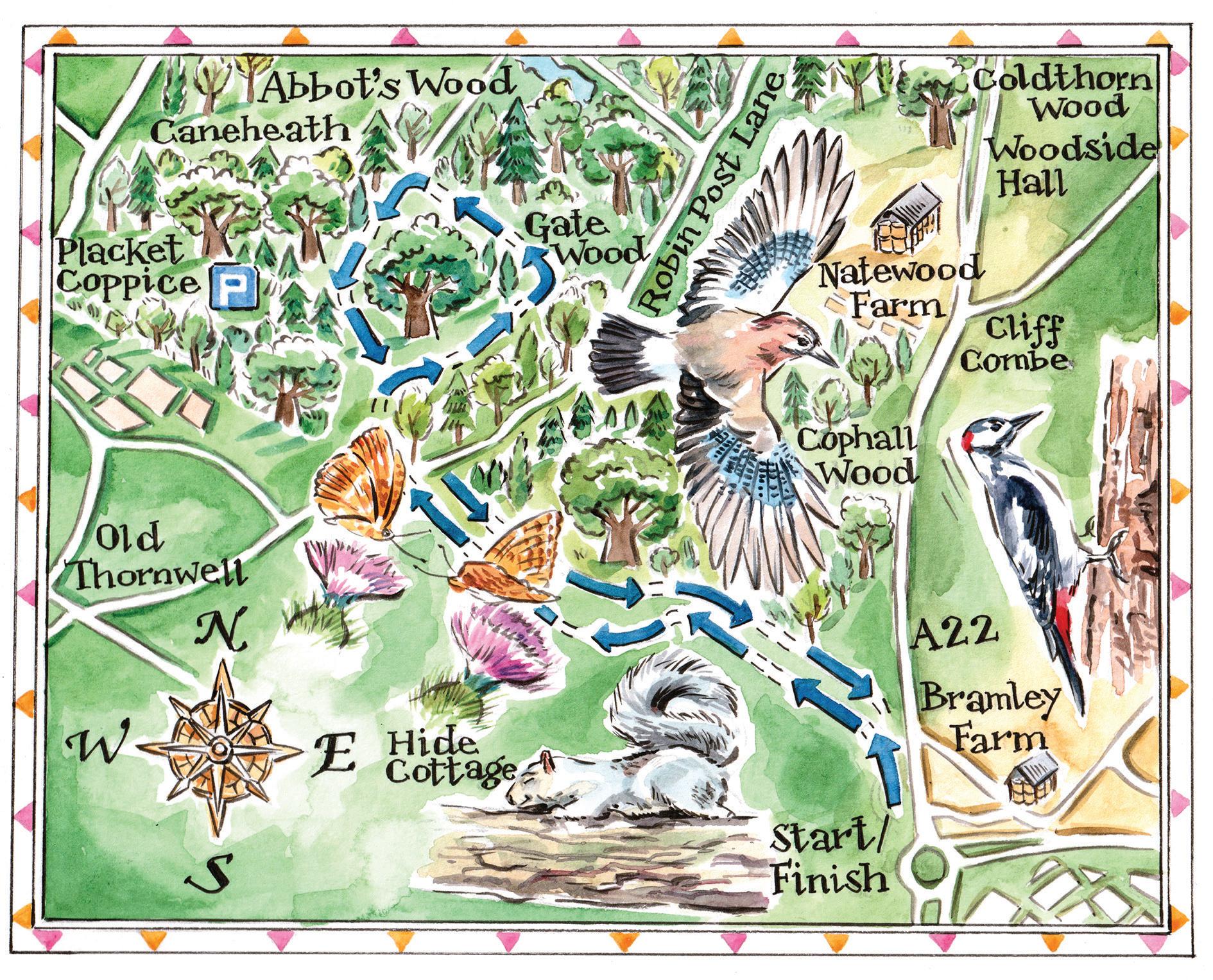

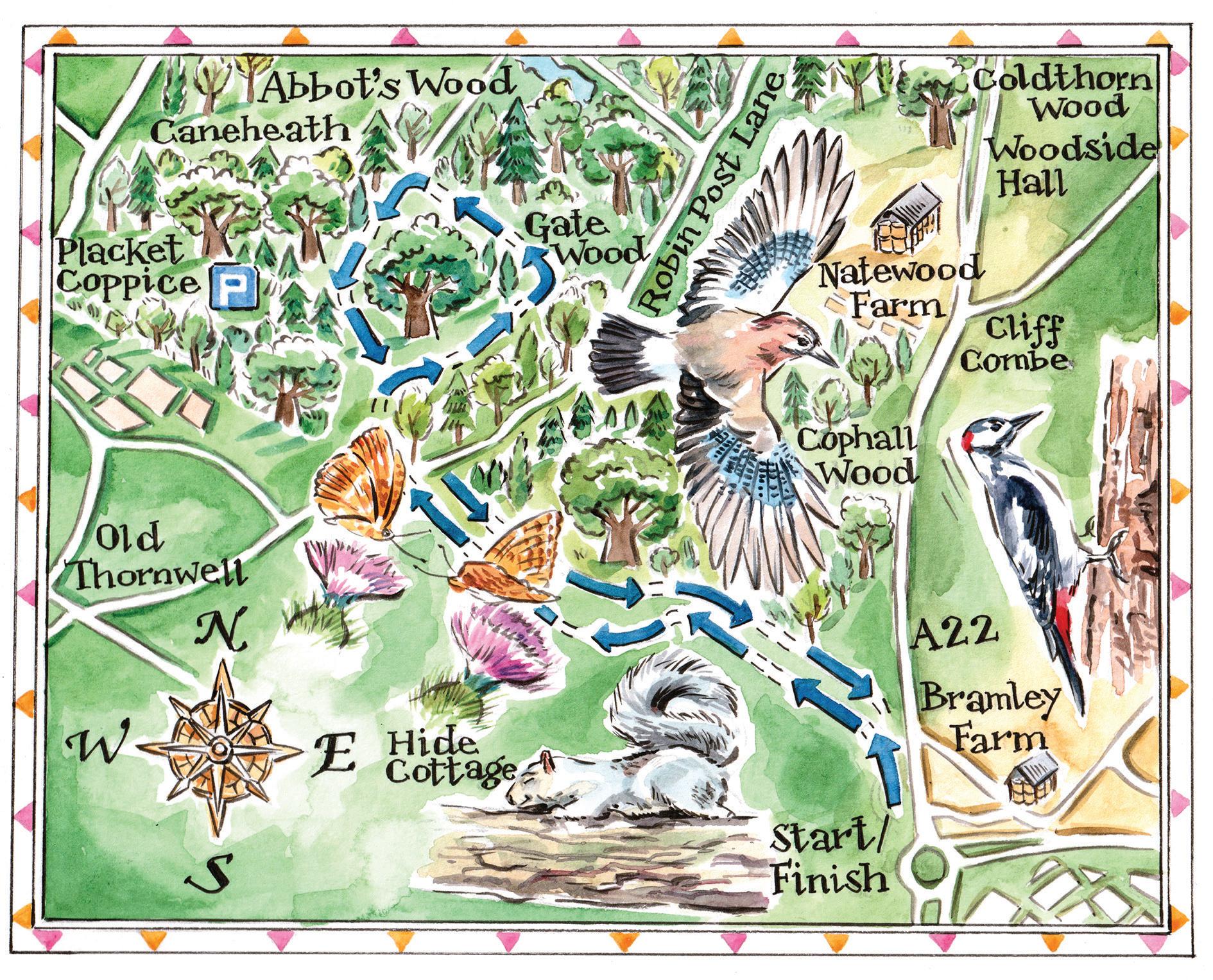

87 Taking a Walk: Holy Abbot’s Wood

Patrick Barkham

Reader Offers

The Oldie literary lunch p35 Reader trip to Copenhagen p79

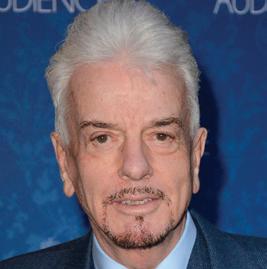

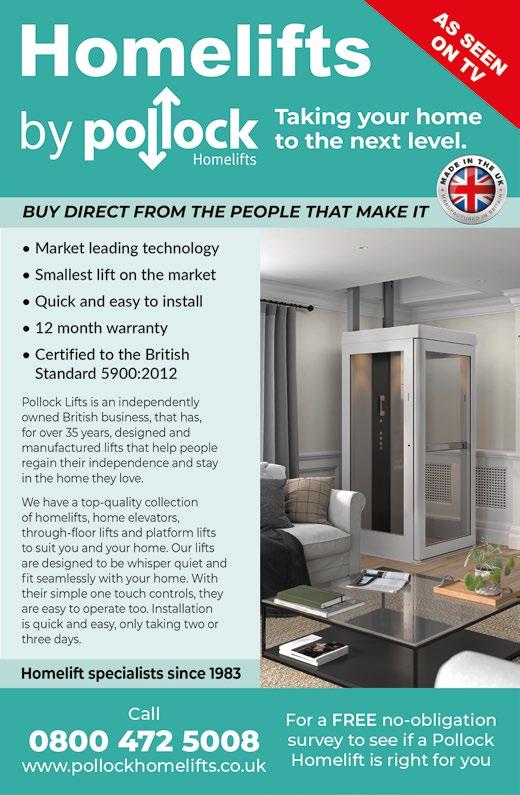

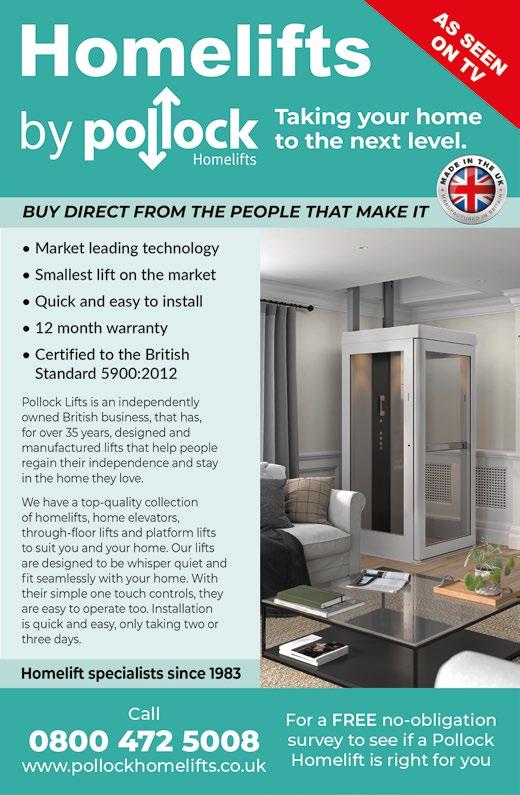

Advertising

Moray House, 23/31

Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk

Supplements editor Jane Mays

Editorial assistant Amelia Milne

Publisher James Pembroke

Patron saints Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

At large Richard Beatty

Our Old Master David Kowitz

To order a print subscription, go to www. subscription.co.uk/oldie/offers, or email theoldie@subscription.co.uk, or call 01858 438791, or write to The Oldie, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF.

Print subscription rates for 12 issues: UK £49.50; Europe/Eire £58; USA/Canada £70; rest of world £69.

To buy a digital subscription for £29.99 or single issue for £2.99, go to the App Store on your tablet/mobile and search for ‘The Oldie’.

For display, contact : Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Jasper Gibbons on 020 3859 7096

For classified: Monty Martin-Zakheim on 020 3859 7093

News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

Front cover Shutterstock / ITV

The Oldie September 2023 3

Classical drama: Don McCullin page 26

Larry Grayson’s centenary Christopher Sandford 16 World’s best film sets Gareth Neame 18 Women can’t have it all Charlotte Metcalf 20 Douglas Adams fired me John

23 Je t’aime, Jane Birkin Simon Williams 26 My Turkish Odyssey Don McCullin 29 Throw caution to the wind Piers Pottinger 30 Coco Chanel’s eternal style Philippa Stockley 31 I sacked the Queen’s bankers Michael Cole 32 Smoking’s hotter than vaping Richard Howells 34 Life on the run Duncan Campbell 35 Ode to the shoehorn Mark Palmer

14

Lloyd

5 The Old Un’s Notes 9 Gyles Brandreth’s Diary 11 Grumpy Oldie Man Matthew Norman 12 Olden Life Colin Westney 12 Modern Life Richard Godwin

Oldie

Letters A N

History David Horspool 40 Town

Tom

41 Country Mouse Giles Wood 42 Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny 44 Mary Killen’s Beauty Tips 45 Small World Jem Clarke 47 School Days Sophia Waugh 47 Quite Interesting Things about ... offices John Lloyd 48 God Sister Teresa 48 Memorial Service: Donald Trelford James Hughes-Onslow 49 The Doctor’s Surgery Dr Theodore Dalrymple 50 Readers’ Letters 52 I Once Met Josephine Baker Josephine Masters 52 Memory Lane Marjorie Lund 65 Commonplace Corner 65 Rant: Moronic adverts Stephen Brook 89 Crossword 91 Bridge Andrew Robson 91 Competition Tessa Castro 98 Ask Virginia Ironside

37

Man of

Wilson 38

Mouse

Hodgkinson

ABC circulation figure July-December 2021: 48,249 Subs Emailqueries? co.uksubscription.theoldie@ or 01858phone 438791

subscribe – and get two free

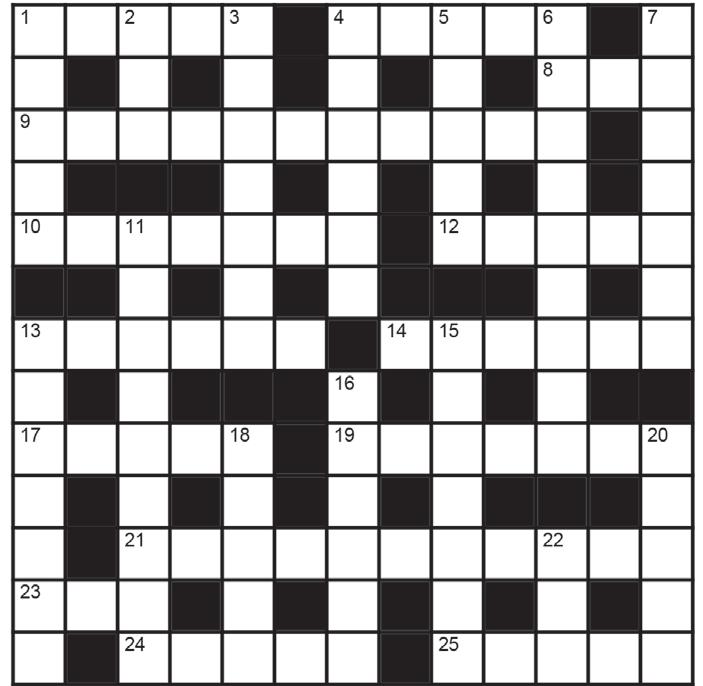

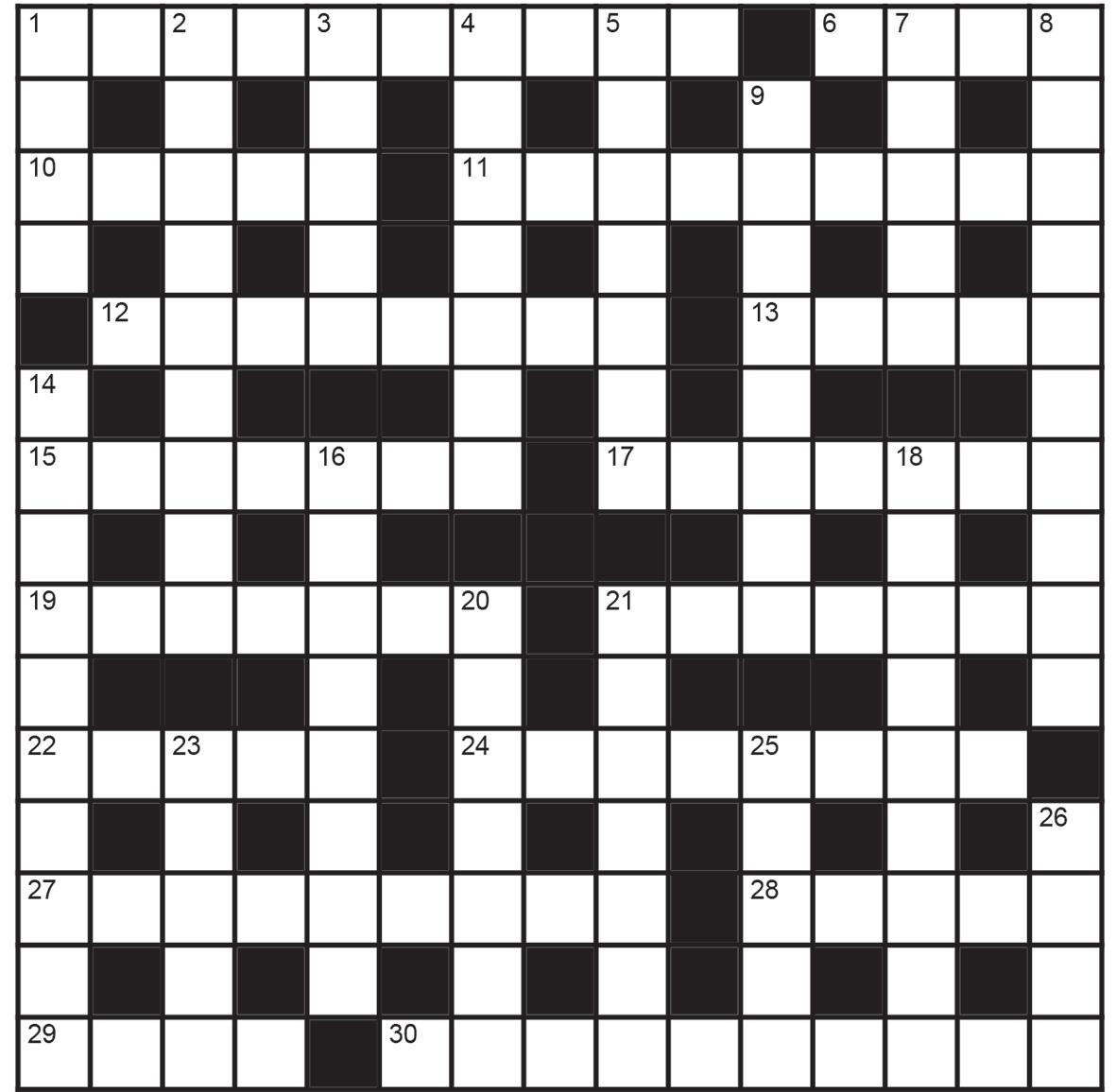

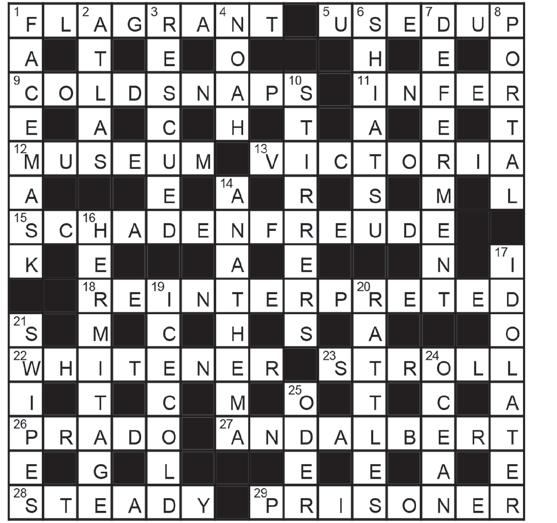

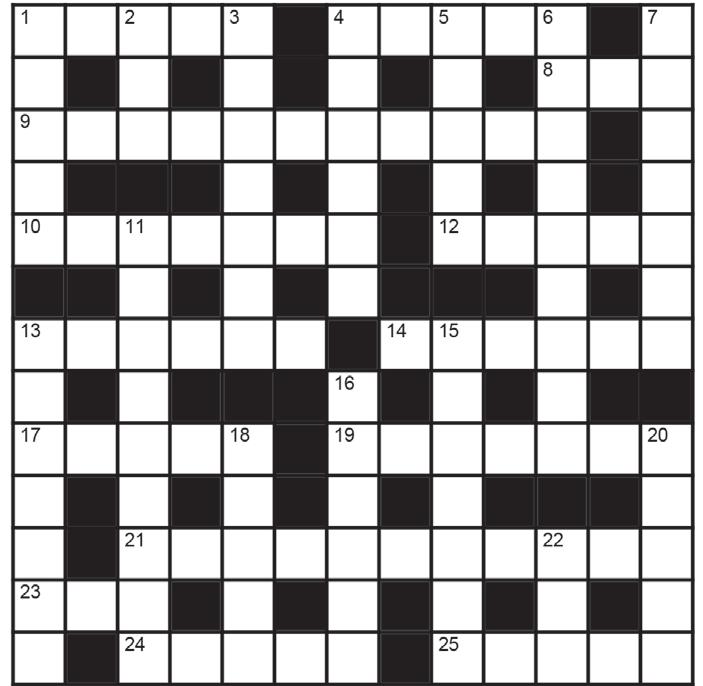

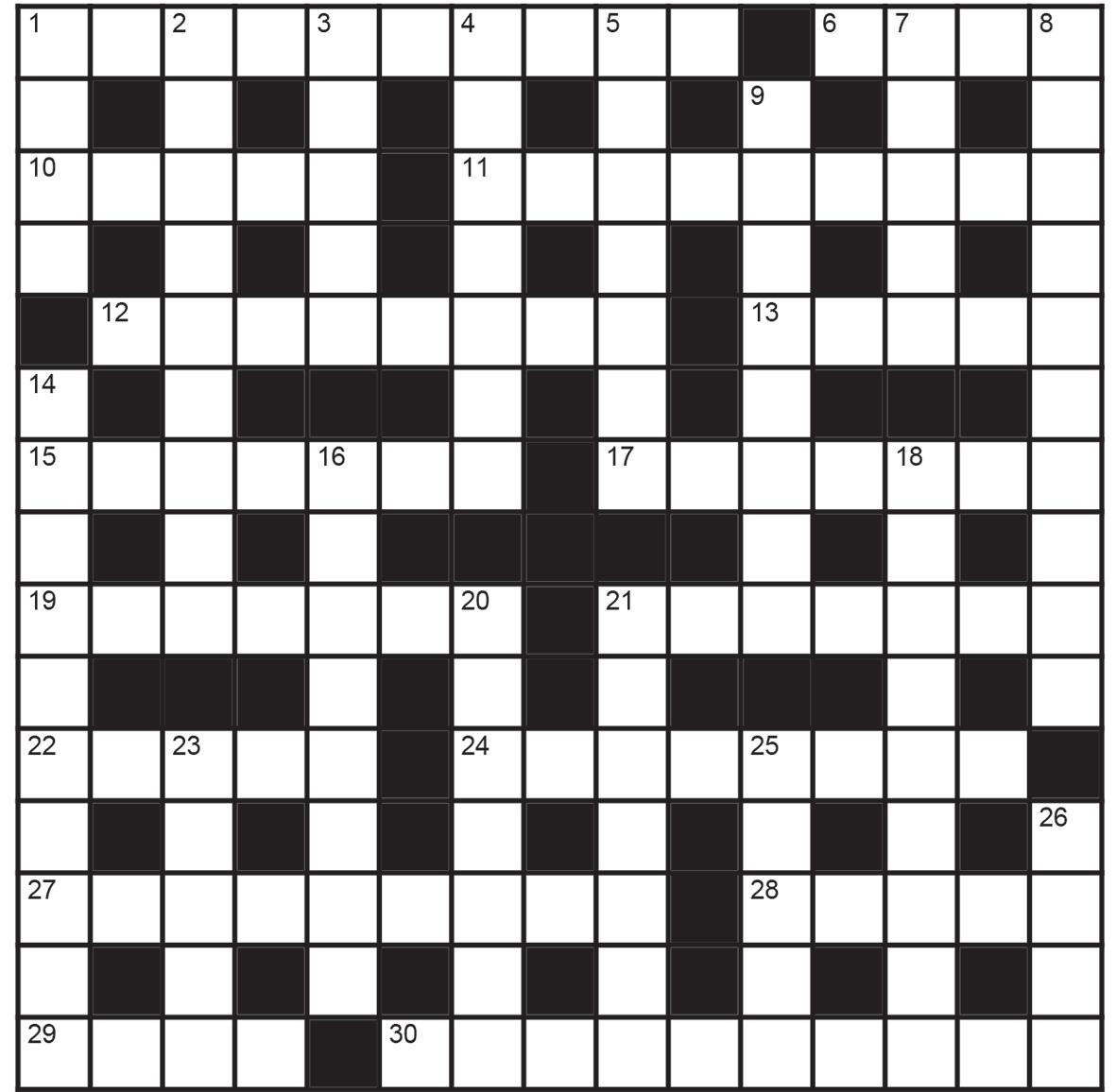

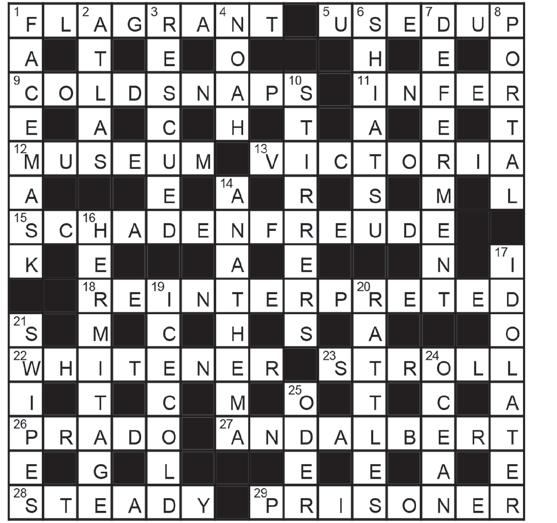

when you

books

Camp sight: Larry Grayson page 14

The Old Un’s Notes

The smoky-voiced actress Glynis Johns, best remembered as the singing suffragette Winifred Banks in the 1964 film Mary Poppins, turns 100 on 5th October.

Born in South Africa, where her parents were on a showbusiness tour, Johns came to Britain at the age of five and attended Clifton High School in Bristol while training as a ballerina.

After appearing in the chorus of several West End musicals, she made her big-screen debut alongside Ralph Richardson in 1938 political drama South Riding.

It was the first of 60 films she graced at roughly yearly intervals until her cameo role as a grandmother in the undistinguished American comedy Superstar (1999).

Perhaps it’s due to the proverbial spoonful of sugar, but it’s pleasing to note that many of Mary Poppins’s senior cast members are still with us. The film’s co-stars Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke are 87 and 97 respectively, and both are apparently in robust health.

Glynis Johns herself, having outlived all four of her husbands, now lives quietly in a retirement community in Hollywood.

Once a martyr to severe migraines, Johns later said, ‘I finally learned how to relax.

‘And, since I have, the headaches which plagued me for years disappeared. When you let God in on your

problems, you can let go and live.’

Of her four marriages she added, ‘It was absolute conservatism on my part. I was brought up to feel that if you wanted to have an affair

with a man, you married him. I have friends who, if they’d followed that rule, would have collected an awful lot of pieces of paper by now.’

Surely it’s high time we recognised this enduring

Among this month’s contributors

John Lloyd (p20 and p47) wrote The Meaning of Liff with Douglas Adams. He produced The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Not the Nine O’Clock News, Blackadder, Spitting Image and QI

Simon Williams (p23) was James Bellamy in Upstairs, Downstairs. He and his wife Lucy Fleming play her parents, Peter Fleming and Celia Johnson, in Posting Letters to the Moon

Duncan Campbell (p34) was the Guardian’s crime correspondent and LA correspondent. He wrote If It Bleeds, The Paradise Trail, The Underworld and That Was Business, This Is Personal

Nicky Haslam (p54) is an interior designer who performs the songs of his friend Cole Porter. His tea-towel list of common things includes ‘Swimming with dolphins’ and ‘Jiggling your knee’.

British icon with a damehood, in time for her century?

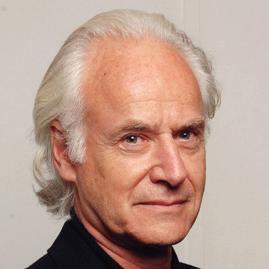

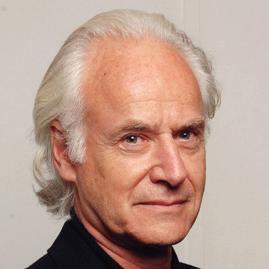

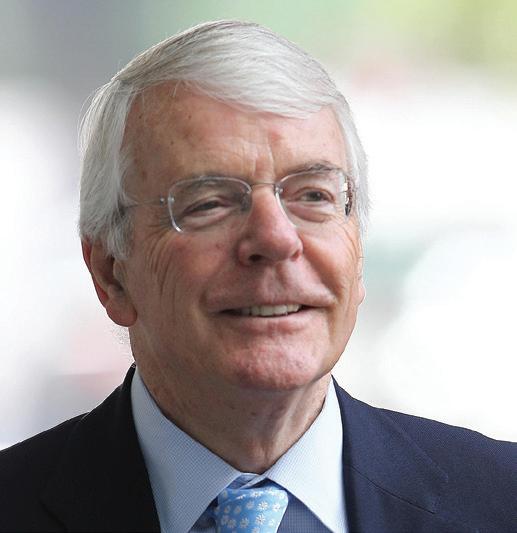

Former Prime Ministers John Major and Tony Blair were at Westminster Abbey for the recent memorial service of Lord Boyce (1943-2022), once the First Sea Lord.

Major collared the Oldie’s Memorial Service correspondent, James Hughes-Onslow, who was instrumental in bringing Major’s brother, Terry Major-Ball, into the spotlight. In 1994, Hughes-Onslow ghosted Major-Ball’s book, Major Major: Memories of an Older Brother

‘You must be something of an expert on this sort of thing, James,’ said Sir John to Hughes-Onslow about his memorial service expertise. ‘We all read you.’

Hughes-Onslow told Major, ‘You look younger every time I see you.’

‘If only that were true,’ said the polite former PM in his charming, selfdeprecating way.

The Oldie September 2023 5

Sister Suffragette: Glynis Johns in Mary Poppins (1964)

Oldie reader: John Major

Important stories you may have missed

Missing vole delays bridge opening

Eastern Daily Press

The obituaries of Bob Kerslake (1955-2023), the former head of the Civil Service, omitted one detail of his time running Sheffield Council two decades ago.

Woman was sent to steal man’s doormat – and nobody knows why Stoke-on-Trent Live

High street takeaway to close for two weeks

Sheerness Times Guardian

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The October issue is on sale on 20th September 2023.

GET THE OLDIE APP

Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

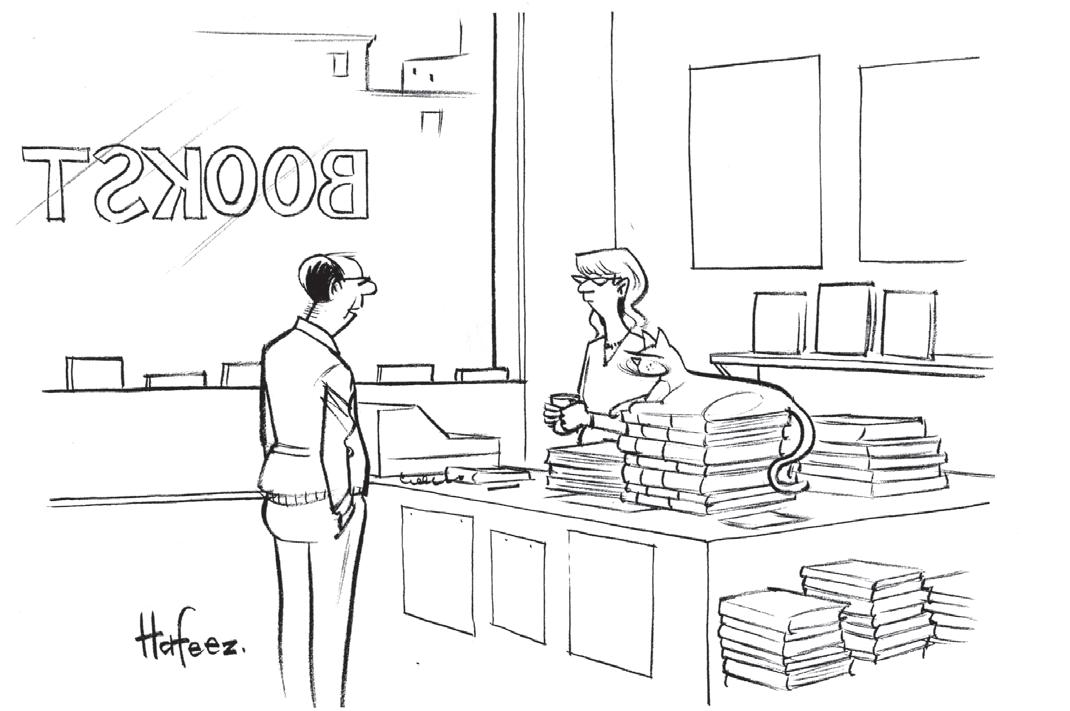

OLDIE BOOKS

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

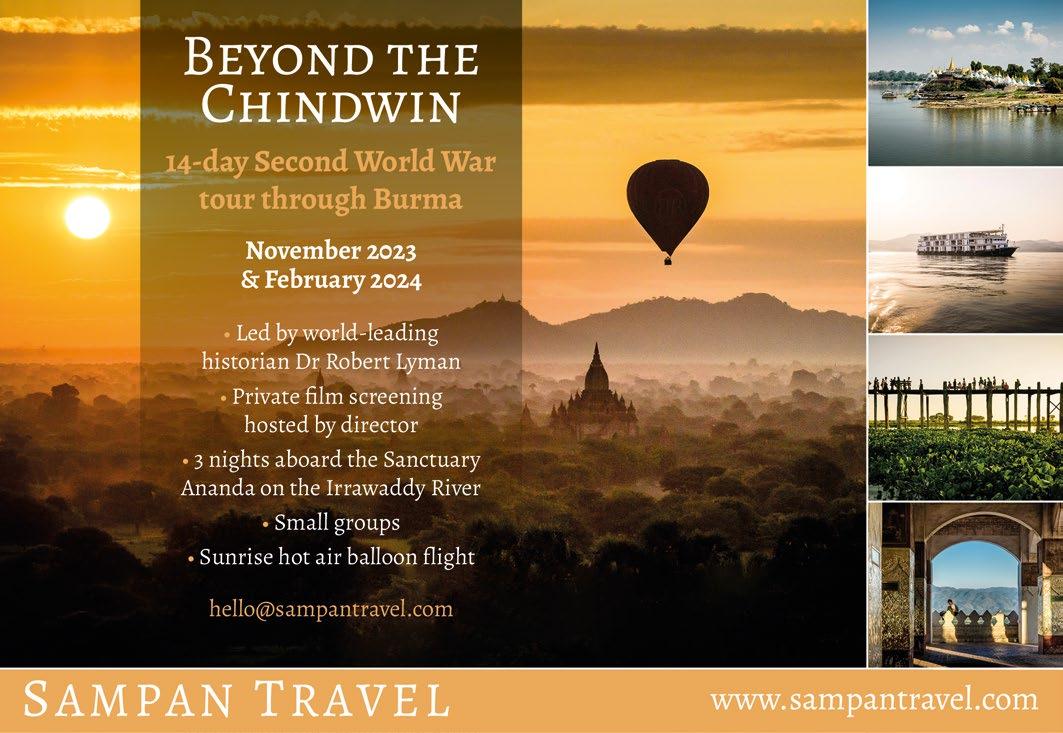

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

An art display of large metal spheres was placed in the city’s Millennium Square. In affectionate tribute, they are still known as ‘Bob’s balls’.

Donald Swann, the composer and comedian best known for his At the Drop of a Hat revues with the lyricist Michael Flanders, would have turned 100 on 30th September this year. Having first met while at Westminster School in the 1930s, Flanders and Swann teamed up professionally after the war, in which Swann had registered as a conscientious objector. Their songs were characterised by a keen sense of absurdity, complex rhyming schemes and catchy

choruses. The Hippopotamus Song (‘Mud, mud, glorious mud’) was their most celebrated number. Slow Train was a fine elegy to the stations cut by Dr Beeching.

In 1964, the deeply religious Swann gave a sermon at St Paul’s Cathedral in which he said that only satire could cleanse the soul of the dreariness of ordinary life.

Like many great creative duos, the Flanders-Swann partnership was sometimes strained. Long concert tours – they were a smash in the States – eventually lost their appeal for Swann, who came to feel there were other things he wanted to write besides comical ditties about gnus, gasmen and London buses.

The pair always looked mismatched – the bearded and lugubrious Flanders, wheelchair-bound after a bout of polio, and the bespectacled, slightly fey Swann tinkling the piano.

They broke up the act in 1967 after 11 years together but remained friendly up to the time of Flanders’s death in 1975. In later years, Swann, who was married with two daughters, wrote everything from operas to religious music to a revue co-created with the poet Henry Reed about a fictitious butch composer named Hilda Tablet.

Swann died of cancer in March 1994, at the age of 70.

‘I never met anybody who knew Donald who didn’t like him; his friends positively adored him,’ one of his obituarists wrote – which isn’t a bad epitaph.

A Commons adjournment debate in July, saluting the late Scottish National Party matriarch Winnie Ewing (1929-2023), was opened by fellow SNP member Ian Blackford, possibly Westminster’s most garrulous orator.

Adjournment debates normally last no more than 30 minutes. This one stretched to an hour. Blackford, pausing from anecdotes about Winnie’s fondness for a dram, recalled that she once sent him a video address for his election campaign.

‘It was not short,’ said Blackford.

MPs: ‘Oh, the irony!’

When the debate finally ended, Deputy Speaker Nigel Evans bolted from the chair like a hare. It turned out he had been bursting for the loo from the very start.

6 The Oldie September 2023 KATHRYN LAMB

Have some Madeira, m’dear: Flanders and Swann

‘Don’t worry. He won’t bite’

Annoyed by your snoring husband?

In 1936, Anne Balliol and Ralph Y Hopton wrote Better Bed Manners

Now in a new edition, it includes the chapters Going to Bed under Difficulties and In Bed with a Nice Person.

One chapter, The Seven Great Problems of Marriage, includes insoluble questions. Among them is The Problem of Light

As the authors observe, ‘Science has realised that the one who is trying to sleep is insufferably annoyed by the wide-spreading light of the bedfellow who loves to read.’

And how wise Sir Walter Scott was: ‘Even the kindest people are savage at night.’

Parliamentary reports are normally published at Westminster but the chairman of the Environment Select Committee, Sir Robert Goodwill, launched its report on species-reintroduction with a fancy event at the Great Yorkshire Show.

The whiff of manure, snouts in the trough, chorused moos: a country show is maybe not such a bad place for a political event.

Old-fashioned cigarette smokers might be fast becoming an endangered species now that most people have quit, vape or resist the allure of the demon tobacco.

But England’s greatest living playwright, Sir Tom Stoppard, 86, was defiantly puffing away on an outdoor terrace at the National Theatre during the interval of a recent performance of Dear England

‘Old habits obviously die hard,’ chuckled a fellow theatregoer wryly.

The acclaimed new James Graham play stars Joseph

Fiennes as England football manager Gareth Southgate; Stoppard wrote the screenplay for the hit 1998 film Shakespeare in Love, in which Fiennes played the Bard.

Needless to say, Sir Tom looked very stylish as he puffed on his gasper – so much cooler than vapes, as Richard Howells writes on page 32.

Civic transport planners claim lower speed limits are good for the planet, but it may only be a theory.

For two years, Labour’s

‘Your poor wife has told me so much about you’

Lord Campbell-Savours has been asking the Department for Transport to provide evidence that vehicles travelling at 20mph emit less carbon monoxide than those trundling along at 30mph.

In 2021, he was told ‘the department does not have specific results’.

He recently tried again during House of Lords questions. No dice.

Lady Vere, a transport minister, said it was ‘up to local authorities to decide on local speed restrictions’. Are eco-claims about 20mph zones mere hot air?

The Oldie September 2023 7 STEPHEN BISGROVE / ALAMY

Smoking jacket: Sir Tom Stoppard

‘It’s

full of type ‘O’s!’

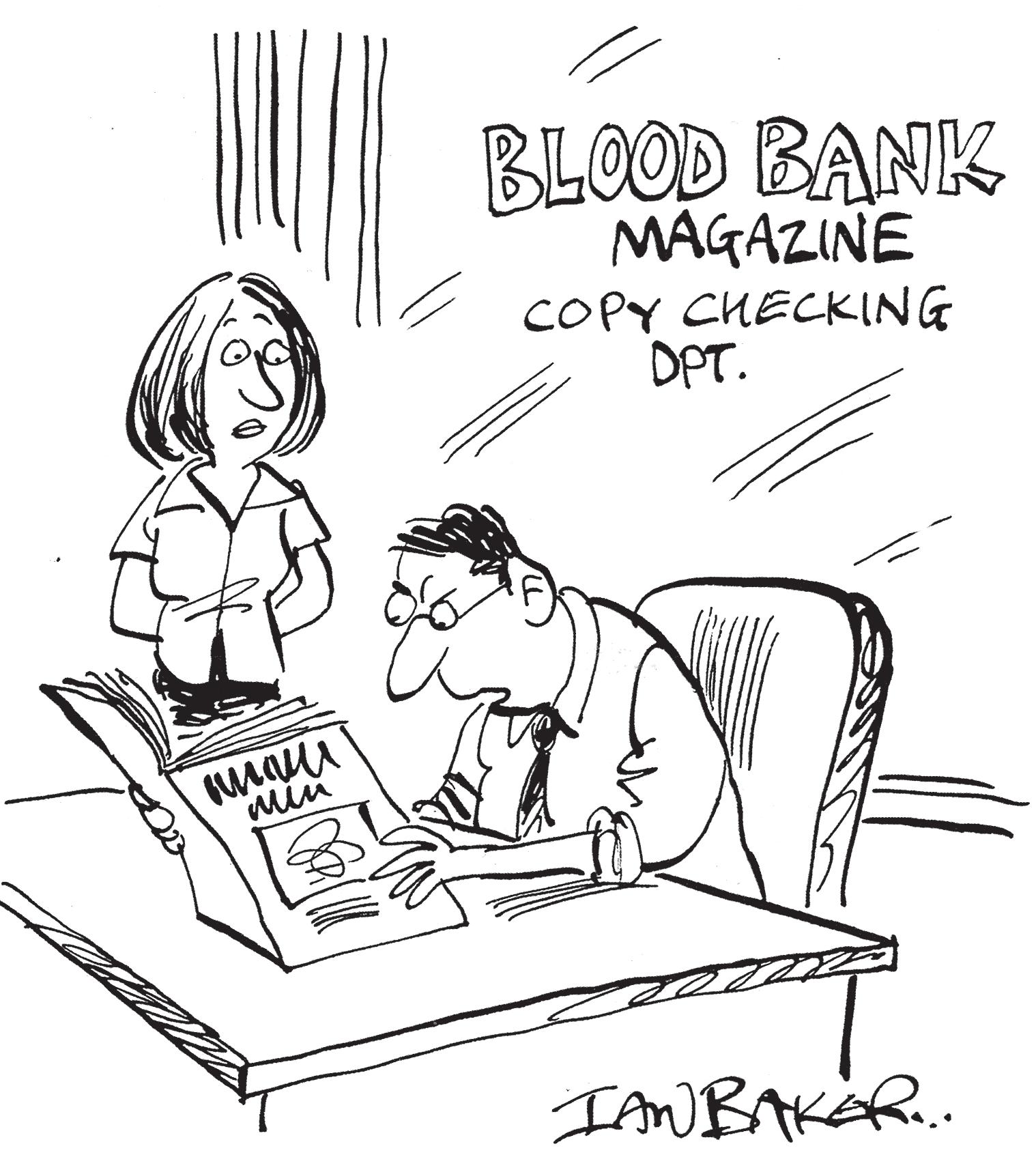

Noël Coward’s MeToo moment

The night the Master groped Judy Campbell, Jane Birkin’s mother

Sadly, I didn’t know Jane Birkin, the Anglo-French actress, singer and beauty, who died in Paris in mid-July at the age of 76.

I had admired her since I was a teenager and saw her, naked, in Antonioni’s seminal Sixties movie, Blow-Up. Later, I got to know the star of the film, David Hemmings (19412003). He told me that Birkin only agreed to get her kit off in Blow-Up because her husband at the time, John Barry, taunted her, saying she wouldn’t dare.

David explained that Jane was very self-conscious about her diminutive bust, but claimed he had reassured her with the line, ‘Who’ll be looking at your breasts, darling, when your face is so lovely?’

Happily, I did know Jane Birkin’s mother, the actress Judy Campbell (1914-2004), and she was very beautiful, too. She had no misgivings about her bust. She told me that, during the Second World War, when she was touring with Noël Coward, playing Elvira in his play Blithe Spirit, she was startled to find Coward, mid-scene, unexpectedly putting his arm around her shoulder and then slipping his hand inside her evening gown and under her breasts. She told me she was rather thrilled at the time.

‘Have I succeeded where so many other women have failed?’ she wondered.

No. Coward was simply trying to keep his hands warm in a cold theatre during fuel-rationing.

Her first claim to fame was singing A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square in the 1940 revue New Faces

The title of the song (one of my favourites) was taken from a short story by Michael Arlen. Eric Maschwitz wrote the lyrics, Manning Sherwin the music.

To my surprise, in the Daily

Telegraph the other day, Charles Moore, attributed the song to Noël Coward. How do these mistakes get through?

More egregious still, in the Mail on Sunday recently, as a so-called ‘Quote of the Week’, the words ‘Emma Chizzitt’ appeared with the explanation: ‘The name Rebus author Ian Rankin mistakenly put on a fan’s copy of his book – the Australian had actually asked, “How much is it?”’

It’s an old joke first made famous by Kenneth Williams when he was in Australia promoting his book Acid Drops in the early 1980s.

I fear I have reached the age when I find myself constantly muttering to myself, ‘Who edits these papers? Does nobody know anything any more?’

Let me tell you a story... Once upon a time, some 60 years ago, a young boy and a young girl were at separate but neighbouring schools.

They knew each other and were attracted. She thought that he was dashing in his sport of fencing. He thought she was elegant in her tennis dress, but nothing happened beyond friendly, gently flirtatious conversation.

They lost touch and lived hundreds of miles apart but, through a mutual friend, received news of one another.

Last year, both being widowed after long marriages, he, no longer a shy boy, made contact. That first telephone call lasted 40 minutes. Subsequent calls rarely lasted less than an hour.

One day, she declared that she loved seaside piers. ‘Right,’ said he, ‘I shall kiss you on every pier in the land!’

That’s how I got to hear about Paul and Janet.

Alongside Timothy West and Joan Bakewell, I am a proud patron

of the National Piers Society, an organisation that celebrates and does its best to help preserve our country’s rich heritage of piers.

Paul contacted the society to help plan his pier-cum-kissathon. Once Britain boasted more than a 100 piers, he discovered. We still have around 63.

According to Paul, ‘Worthing and Brighton were soon visited and “kissened”.’ The next trip took in Clevedon, Weston Grand, Weston Birnbeck, Weston Revo, Burnham, Teignmouth Grand, Paignton, Torquay Princess, Weymouth Pleasure, Swanage, Bournemouth, Boscombe, Hythe, Southsea South Parade and Bognor.

‘Phew!’ says Paul, ‘Only 35 to go.’

When the couple reach the final pier, Paul tells me that (if he still can) he plans to drop on one knee and pop the question.

‘Piers,’ says Paul, ‘are very romantic.’

Who needs Tinder, Grindr, eHarmony or Hinge when you can get in touch with www.piers.org.uk?

I am spending the summer in Edinburgh, strutting my stuff daily with a one-man show as part of the Fringe. Then, in September and October, I am off on tour, taking the show around the UK.

In some places, it’s sold out. In others (for example, Colchester and Cardiff), there are ‘seats in all parts’ and I’d love to see you.

The only downside to being away from home for so long is that I miss our cat. She’s called Nala. We inherited the name (and the cat, in fact) from our neighbours.

Mark Twain named his cat Bambino. Christina Rossetti called hers Grimalkin. Ernest Hemingway had a cat named Snow White. Iris Murdoch named hers Black Madonna.

If we could have christened Nala ourselves, we should have given her the name the poet Thomas Hood gave to his: Scratchaway.

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

The Oldie September 2023 9

Judy Campbell in 1940

Nothing compares to you, Mum

Is there a more comical phrase, from the mouth of someone pushing 60, than ‘I’m an orphan now’?

There may be rivals. ‘Suella Braverman,’ for example, ‘she’s nice.’ Or ‘I love flying Ryanair.’

For all that, there is something so innately amusing about a decaying sea monster echoing a red-haired moppet singing about tomorrow being a day away… Suffice it to know that I’ve been using that line relentlessly of late, and been rewarded with grins.

Orphanhood commenced in late July, when my mother died almost immediately after the news broke about Sinéad O’Connor. She was buried in August at exactly the same time as the Irish singer.

They had little else in common. My mother had the hideous singing voice she bequeathed me via her DNA, and never ignited a photo of the Pope on live television.

O’Connor almost certainly couldn’t make chopped liver like my mother, and must have been a less hypercritical back-seat driver. Troubled as she sadly was, it’s hard to envisage her screeching, ‘Matthew, you’re going to kill us both,’ whenever a speedometer nudged 15mph.

But in the timing of death and interment, the two were sisters. So excuse the lurch into the bleedin’ obvious when I say of my mother that no one compared (no one compaaaaared) to her.

Familiar as she may have become to that mythical beast, ‘the regular reader’ of this column, I never did justice to her ferocious loyalty, staggering disinhibition, unquenchable kindness, terrifying frankness and ferocious intolerance.

It was she, in a Wimpy Bar in 1973, who rejected seven consecutive cups of tea for unacceptable weakness. And she who later, in a swankier joint, sent back a Scotch on the rocks on the novel ground

that ‘This ice is much too cold.’

When it came to calf’s liver, her requirements as to thickness were so exacting that for a while she carried a pair of callipers alongside the mirror, purse and make-up items in her handbag.

As her personal chef and chief carer these recent years, I know that living with my mother was sometimes hard. But I’d be more than willing to give it another try, because she was as beguilingly lovable a person as I and so many others have known.

Her range of bespoke witticisms was wide, but the one that surged to mind at the funeral was the one she unleashed whenever asked if someone had died. ‘If she didn’t,’ she’d reply, ‘they took a terrible liberty burying her.’

It felt a terrible liberty burying her, because she never grew old in anything but the stark numbers. She was 88 during last winter’s World Cup – she loved her football – and astonished us with her percipience.

Those watching the final with her, and the phalanx of pundits on the BBC, were totally bamboozled by France’s first-half lethargy against Argentina. ‘They don’t look well to me,’ she observed during the interval. ‘I reckon most of them have a bug.’ No one else aired the possibility until after the game, when the French coach Didier Deschamps mentioned a virus that swept the camp in the previous days.

‘Of course I was right,’ she concurred when congratulated on the insight. ‘I’ve only been wrong once in my life – and that was a mistake, and it turned out I’d been right all along.’

As with the loss of any parent, her death unleashes an avalanche of memories, from her impossible glamour during my childhood when she looked almost the spit of Audrey Hepburn and travelled the world as a fashion editor; to the dazzling smile that melted such recent visitors as the nurse who asked if she knew where she was. ‘New Zealand,’ she snapped contemptuously back.

But the memory that most vibrantly stands out comes from a lunch at a Berkshire restaurant a dozen or so years ago, on her daughter-in-law’s 50th birthday.

Even by this family’s standards, it was an eccentric outing from the moment my wife, at my mother’s request, fetched her tortoise Miles from the car and encouraged him to take a constitutional around the table.

My mother was so enchanted by the sight that she toasted Miles a bit too freely. A while later, I was summoned to the Ladies by a nervous waiter. It took her several minutes to undo the lock. When she did, I found her sitting on the floor paralysed by giggling. I helped her up, and we staggered back to the table sobbing with laughter.

We often did, not least on the day her own mother died in 1990. ‘I’m an orphan now,’ she greeted me when I arrived to comfort her, and we exploded with mirth. Grief is no excuse for tiresome sombreness. We didn’t agree about everything, but we agreed about that.

‘I just can’t help feeling that we’d get along better if you had a better job’

A simply magnificent character, she was dependably hilarious until very nearly the end of her long and richly varied life. If there’s any finer way to be remembered than that, I can’t imagine what it might be.

Grumpy Oldie Man

The Oldie September 2023 11

She died at the same time as Sinéad O’Connor - and she was a comic genius matthew norman

who were the Peculiar People?

The Peculiar People were a Christian group founded by James Banyard in Rochford, Essex, in 1838. Banyard, the impoverished son of a ploughman, was born in the town in January 1800.

He became a dissolute youth with a reputation for drunkenness. He was later jailed for petty acts of smuggling and poaching.

He married his first wife, Susan Garnish, in 1823. His drunkenness worsened and culminated in him losing his money and, it is said, most of his clothes at a fair. Susan demanded that he change his ways or she would leave him.

So he started to attend a Wesleyan Chapel in Rochford. It is believed he soon ‘saw the light’, became a teetotaller and even preached on occasions.

In 1837, Banyard became friendly with William Bridges, who was a visiting Methodist preacher from London. He

what is an NPC?

NPC stands for non-player character. It describes the characters in computer games that the player doesn’t control.

The ghosts in Pac-Man, the eponymous expeditionary force in Space Invaders, the villagers you interact with in Zelda, the bystanders you run down in Grand Theft Auto – these are all examples of non-player characters.

NPCs are crude forms of artificial intelligence and essential parts of just about any game you could care to play. They run along predictable paths, as dictated by the programmers. The aim is usually to better them using your superior human intelligence.

After a few plays, you realise the best way to kill a Cacodemon in Doom is to throw a ‘frag’ grenade into their mouth, or that the best way to score a goal in Fifa is (according to my nine-yearold) ‘playing a through ball from

was so taken by his new friend’s views that he became a born-again Christian, preaching forgiveness in all its forms. But his zeal did not find universal favour with all the chapel members, and he was refused permission to hold his own evening prayer meetings.

Banyard’s strength of character and self-belief resulted in a split among the chapel members. He attracted a group of followers, known as the Banyardites. They strongly believed in spiritual healing and the power of prayer and refused the use of the medical profession.

Banyard and his followers called themselves the ‘Peculiar People’ from phrases in the Bible that appear in both Peter and Deuteronomy. He said the group’s name reflected a translation of ‘God’s cherished personal treasures’. Their form of worship was based on their interpretation of the King James Bible In 1843, Banyard married for a second time, to Judith Knapping, and they had seven children. His wife was from a wealthy family and this enabled him to

buy a plot of land on which to build the Peculiar People’s first chapel. He became the group’s first elected leader.

Sometime later, Banyard’s son fell seriously ill and he summoned help from a doctor, which caused dissent among his flock, and many left. He continued to preach until he died in 1863.

In 1910, there was a diphtheria outbreak in Essex, which split the followers again into Old Peculiars and New Peculiars, depending on their views on the use of medical care. This split wasn’t healed until the 1930s.

By 1956, members had changed the group’s name to something less divisive, namely the Union of Evangelical Churches. A chapel was built but in the 1980s it was demolished to make way for a housing estate. There were other changes, which included the creation of the Rochford Community Church in 1987. The Union of Evangelical Churches continues in east London and Essex. The original name of the Peculiar People is almost forgotten.

Colin Westney

the edge of the box’. But NPC has a subsidiary meaning, too. In internet slang, an NPC is someone with no critical reasoning skills who parrots political talking points in a seemingly pre-programmed manner.

‘If you get in a discussion with them, it’s always the same buzzwords and hackneyed arguments,’ one poster explained on the anything goes forum 4chan in 2016. ‘It’s like in a [video game], when you accidentally talk to somebody twice and they give you the exact lines word for word once more.’

The term became popular with Right-wing trolls on social media after Donald Trump’s election when it was commonly used to dismiss Hillary Clinton supporters. And it has re-emerged with a vengeance on Twitter since Elon Musk took over the platform.

I noticed it when a user tweeted that his wife was selling their Tesla, so appalled was she by the direction Twitter had taken under Musk. ‘Lol, then your wife is an NPC,’ replied a person called

@MAGAtakes. What’s quite funny about this is Musk’s fanboys (who tend to overlap with Trump fanboys) behave precisely like NPCs.

But is it so bad being an NPC? I got into a discussion not so long ago with the philosopher Sacha Golob about whether AI art undermined human individualism.

‘It is really hard to be an individual, right?’ he said. ‘Most of us aren’t really individuals. With most people, the things they like, the goals they have, the positions they take are of a type. It’s why everyone’s Instagram posts look the same.’

Maybe it’s simply best to admit it. Over on TikTok, meanwhile, the NPCs are having the last laugh. The big craze of 2023 is ‘NPC Streaming’. This is when real-life people pretend to be computer-game characters and parrot set phrases when followers send them digital knick-knacks.

‘Mmm! Ice cream so good!’ and so on. If that made no sense, I promise you, watching one of these performances makes even less sense. But some people make thousands of dollars a day this way.

Richard Godwin

12 The Oldie September 2023

NPC ghosts: Pac-Man

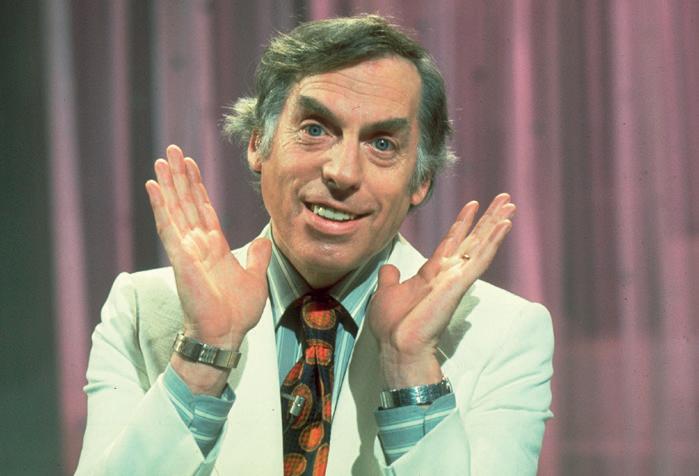

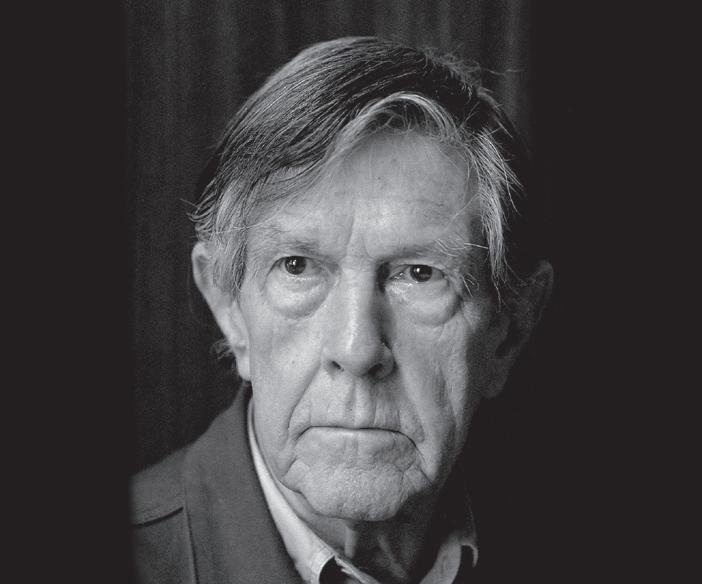

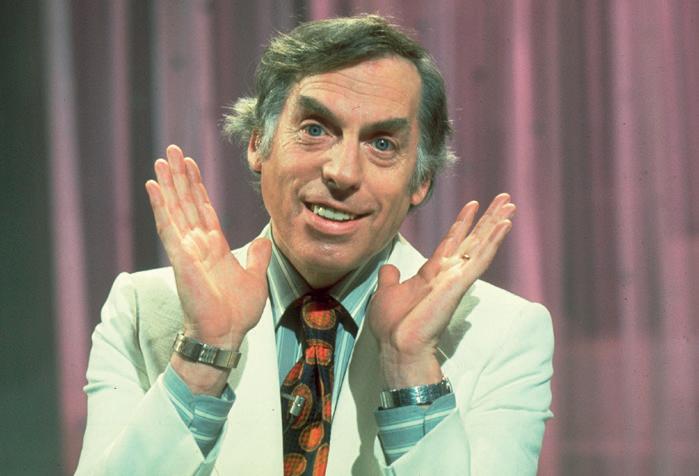

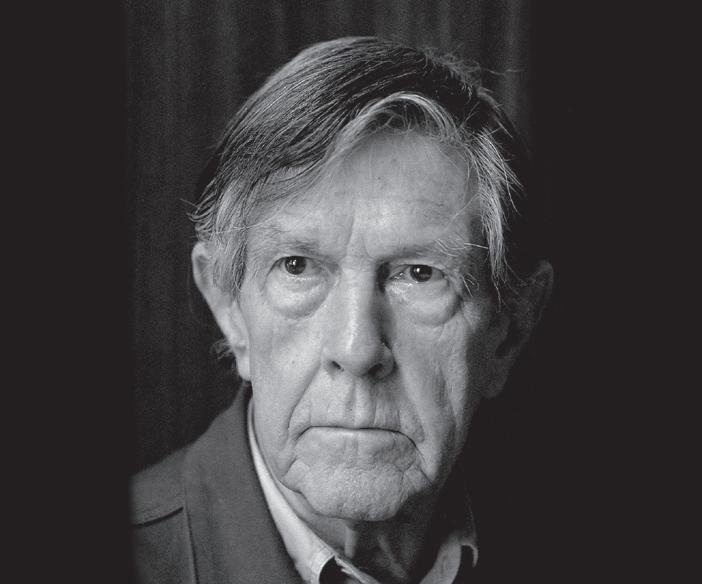

Larry Grayson, born 100 years ago, was a child actor, female impersonator – and national treasure. By Christopher

Sandford

Shut that door!

You might think a birth name of William White, which as a boy he shortened to Willie White, had quite enough comic potential for an entertainer who later brought high camp to British television.

But, in the end, he rejected it for the nom de panto Larry Grayson.

William was born, out of wedlock, on 31st August 1923. He never knew his father and grew up with a foster family in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, where his mother sometimes visited him as ‘Aunt’ Ethel.

Then his foster mother died when he was just six years old, leaving him in the

care of her two adolescent daughters.

His childhood may have had its Dickensian side, but it also supplied many of the real-life models for his later comic monologues featuring the likes of Apricot Lil, Pop-it-in-Pete the postman, and Slack Alice, the coalman’s daughter with her Black Bottom.

Leaving school at 14, William made his stage debut at a local working men’s club, singing a number called In the Bushes at the Bottom of the Garden. Both it, and his later repertoire, were a veritable dictionary of musical innuendo.

From there, using the name Billy Breen, he went on to develop a variety act as a female impersonator, sashaying

around in a knee-length frock and a beret. Delivering his lines with pursed lips and fluttering eyes, he was as high camp as a row of Alpine tents.

A few years later, he changed his stage name for the final time, taking the surname of the Show Boat star Kathryn Grayson, and adding ‘Larry’ because he liked the sound of it.

Grayson spent the next 30 years slogging his way through clubland, honing his brand of slightly surreal, observational comedy.

Some of his trademark catchphrases took root as a direct result of his working environment. ‘Look at the muck on ’er’ originated when he followed a parrot

14 The Oldie September 2023

ITV / SHUTTERSTOCK

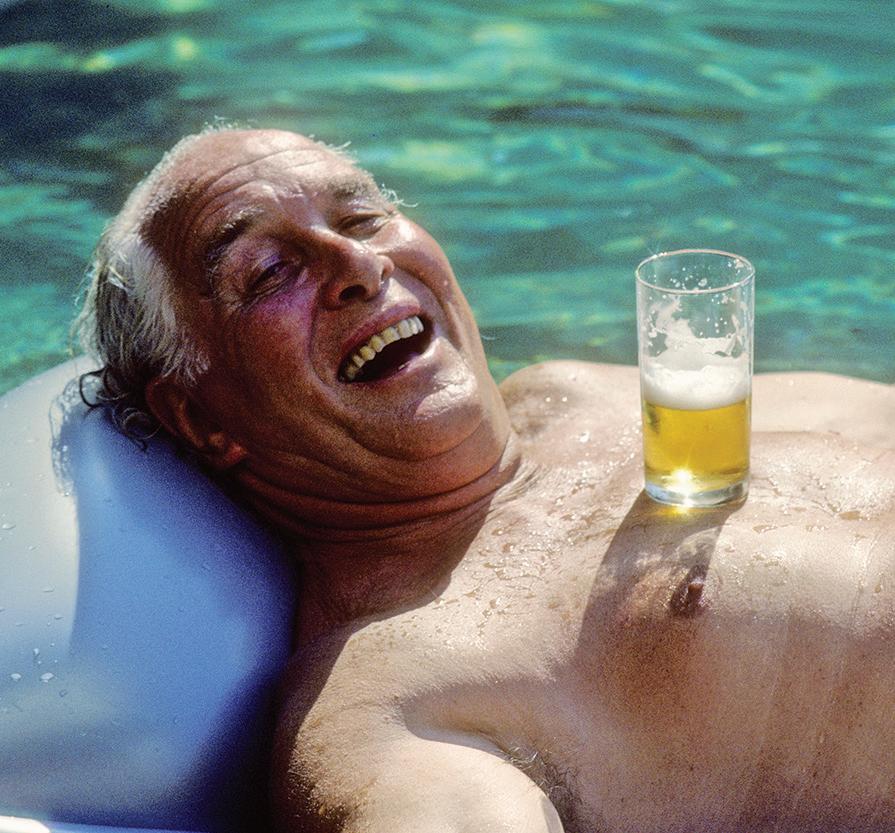

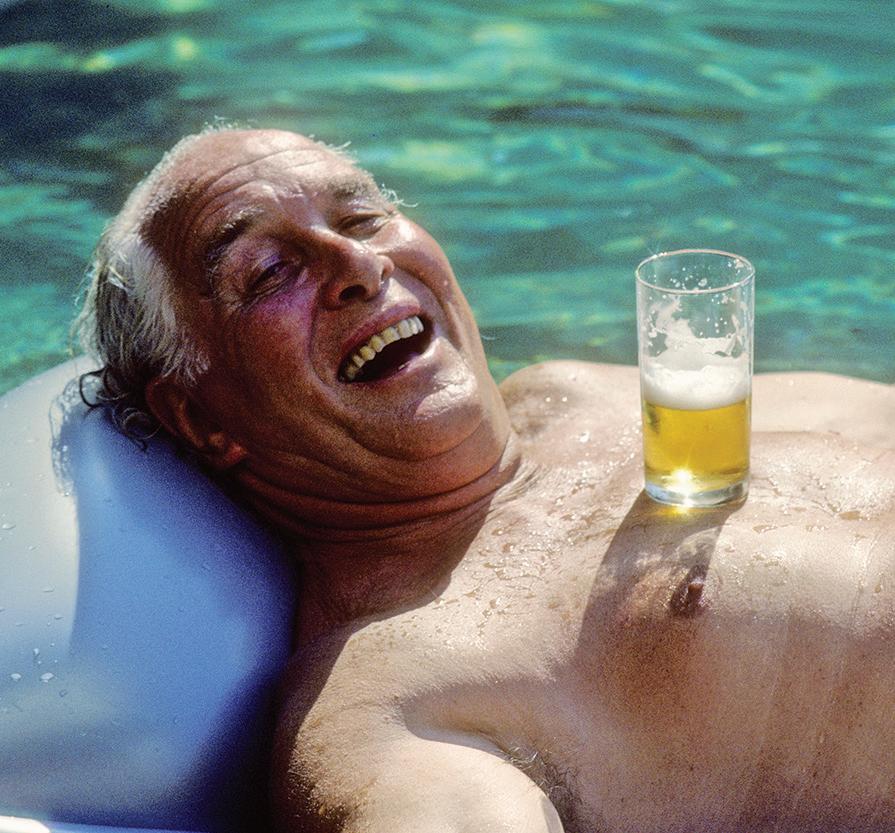

In the swim: on The Larry Grayson Show, 1977

impersonator – or a real parrot, in some accounts – out on stage.

‘Shut that door!’ – his most famous catchphrase – came when he felt a sudden draught while performing at a seaside theatre in Redcar. Grayson instinctively shouted the phrase, got a laugh and kept using it.

A gentle and genuinely shy man, Grayson was in some ways an unlikely candidate to be a public entertainer, let alone one who pranced around the nation’s provincial clubs and holiday camps in a frock before finally hitting the big time in his fifties.

Post-war British audiences may have enjoyed a good drag act, but the times as

a whole were still inhospitable to openly gay performers. Perhaps, as a result, Grayson preferred to keep his personal life quiet.

The closest he ever came to a love match was with a Nuneaton school friend called Tom Proctor, who was killed in action at the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, at the age of 21. Grayson never got over the loss.

His only live-in companion in later life was his beloved foster sister and surrogate mother, Florence, known as Fan, although he was once rather improbably said to have been engaged to the actress Noele Gordon of Crossroads fame.

‘Larry and sex just didn’t go together,’ says his former manager, Paul Vaughan. ‘I remember when gay activists were trying to out him, and two of them came in to meet him in his dressing room. He just sat there with his poodle, Arthur Marshall, and said, “Now what’s all this about?”

‘One of them said, “Mr. Grayson, we just want you to come out and say you’re a homosexual.” Immediately Larry put his hands over Arthur’s ears and said, “Ooh, you can’t use language like that in front of my dog.”’

Grayson’s big break came in 1972, when the ATV boss Lew Grade signed him up for his Saturday night variety show, before giving him his own 16-part series, Shut That Door! Actually, it was more like a door opening.

When Bruce Forsyth left the BBC in 1978, Grayson took over as host of The Generation Game, which was soon trouncing Forsyth’s rival ITV show The Big Night in the ratings.

An engaging mixture of observational humour, sexually ambiguous jokes and good, old-fashioned show business oomph, it once attracted an audience of 25 million viewers, although admittedly the competing channel was out on strike at the time.

Unusually, it was Grayson himself, not the network executives, who ended his tenure on The Generation Game in 1982, citing his desire to ‘go out on top’ – another line he delivered with a knowing roll of his eyes.

After a series of only fitfully successful comebacks, Grayson made his final television appearance on 3rd December 1994, as part of the Royal Variety Performance recently filmed at the Dominion Theatre in London.

‘You thought I was dead!’ he commented from the stage, referring to his long absence from the nation’s screens. Sadly, only a month after the show’s transmission, he actually was dead, after suffering a fatal haemorrhage at his Nuneaton home in the early hours of 7th January 1995. He was 71.

Grayson never quite became an international superstar, although he had his moments, and was obviously reluctant to be a spokesman for anyone’s causes.

‘Endearing’ was the usual verdict, upgraded in the polite obituaries to ‘beloved national treasure’.

The Oldie September 2023 15

Christopher Sandford is author of The Man Who Would Be Sherlock: The Real Life Adventures of Arthur Conan Doyle

On The Larry Grayson Show and, left, with the Lochiel Marching Band of Scotland on The Generation Game in 1978

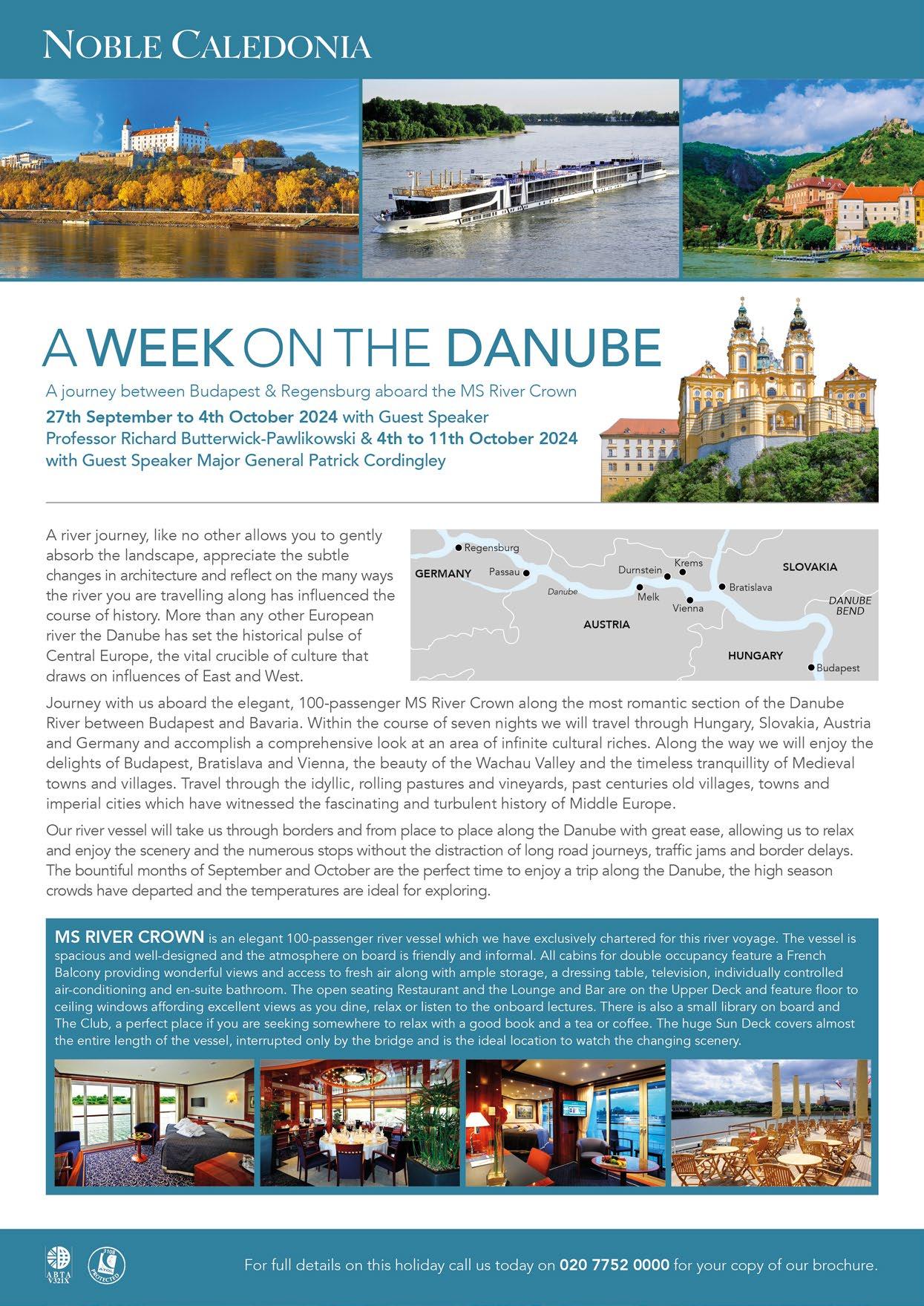

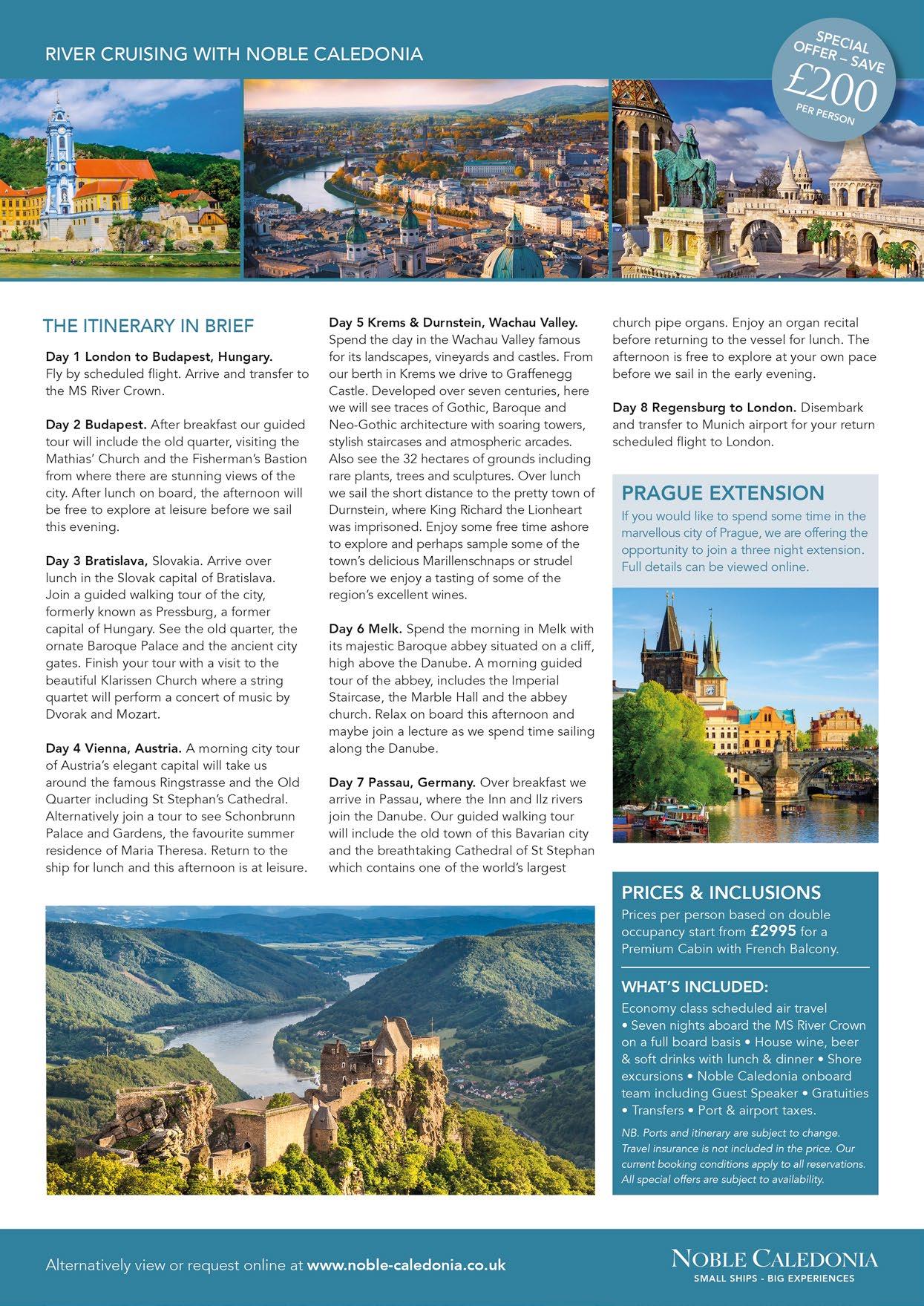

For his film sets, producer Gareth Neame turned Edinburgh into Belgravia and Hungary into colonial Virginia

Location, location, location

Only a handful of films or television shows that are developed – when a script is written and the concept worked out – will actually make it to the screen.

For all sorts of reasons. Priorities change, executives leave their jobs, budget issues ... the list goes on.

When I was developing Downton Abbey in 2009, it suddenly started to look as though we might get our show ‘greenlit’. Until then, the series was just words on a page and the abbey itself was in my imagination.

While most film settings are an amalgam of different places in the minds of the creatives involved, when I asked our writer, Julian Fellowes, which real location best characterised the show, he immediately proposed Highclere Castle.

Because it hadn’t been seen often on screen before, I had to confess I had barely heard of the place. I took a look.

Unannounced, I arrived in an empty car park and bought my ticket for the house tour. Our group consisted of me and a young father with his two sons who seemed more interested in the outstanding Egyptology exhibition than the architecture of Sir Charles Barry.

Cut to a year or two later and Highclere had become one of the most famous historic buildings in the world, just as Castle Howard was world-famous in the decades after Granada’s landmark Brideshead series.

When the setting is the show itself, choosing the location is like casting the star actor. Suitable as Highclere certainly seemed, it felt too crucial a decision to make that easily. I insisted that we spent the autumn of 2009 looking up and down the length of the country at the other

candidates to ensure we had considered every possible option. Newby Hall in Yorkshire was almost the one.

Having visited many dozens of places, we came back full circle to Highclere –chosen due to its dazzling architectural self-confidence, symbolising the apogee of the British aristocracy.

Prior to Downton, most period dramas had been literary adaptations and heavily dependent on Georgian and Regency architecture – so Barry’s high Victorian statement was a fresh approach on screen. We loved the elegant suite of interconnecting state rooms and the fact that it is somehow both grand and intimate, ideal for a series that’s ultimately about a family.

Highclere Castle – the ‘Real Downton Abbey’, as it is now affectionately known – became the backbone of our world, though viewers often forget that only the

exterior and state rooms are used. The bedrooms upstairs and the whole servants’ quarters were constructed on a sound stage. That’s why a footman could take a tray of food up the backstairs at Ealing Studios, to serve the dishes in the dining room, filmed at Highclere about a month later, with the extraordinary Van Dyck portrait of Charles I gazing down.

For the village itself, Bampton in Oxfordshire was selected. Again, this picturesque Cotswold village had never appeared on screen, though it is now famous enough to merit coach tours – unofficial and neither encouraged nor authorised by us, I can assure you, good denizens of Oxfordshire!

You’d think that choosing locations is all about creativity and the look, though, as with practically everything in life, it is ultimately about money. Many countries around the world offer attractive financial

16 The Oldie September 2023

Neame visited dozens of houses before casting Highclere Castle as Downton Abbey

incentives to producers to select their camera-friendly landscapes. In choosing where to shoot, I have to combine the on-screen visuals with the most costeffective locale based on my budget.

Only James Bond globetrots to all the real settings in those movies. For most producers, the trick is to find one place and create the world from there.

We once made an eight-hour American television series where every episode was set in a different country.

Stories set in Nigeria, Myanmar, San Diego, Paris, Kosovo, Kashmir and Haiti were replicated using a combination of South Africa and Prague. Strong tax breaks in both jurisdictions, you see.

When I made three seasons of Jamestown for Sky, the 1620 Virginia colony was constructed in Hungary, which has one of the best tax incentives in Europe and a first-class film industry.

Central Europe endures the contrast of bitterly cold winters and extremely hot summers. When Sky bought the show, I had to insist they stick to a defined schedule: while I could create a subtropical feel filming May to September, the other half of the year would be more appropriate for a show set in Siberia.

The River Danube became Chesapeake Bay and very convincing it was too. We flew Native American actors from North America and the soundtrack of insects added to the actualité.

Hungary also doubled as 9th-century England for all five seasons of our Netflix series The Last Kingdom and the subsequent movie Seven Kings Must Die. I shot a film about the Gallipoli campaign in Andalusia and a miniseries about the Gunpowder Plot in Romania.

Most films and television series require hundreds of different locations to tell the story. Film people get terribly excited when they are breaking new ground. The location manager proudly explains to the director and designer that this chalk quarry – or whatever – has never before been revealed on screen. In fact, audiences don’t really give a hoot about that, if they even notice at all.

For Downton Abbey, we use many of the same grand locations they use on The Crown, including Lancaster House, Wrotham Park and Goldsmiths’ Hall, but I doubt many viewers are troubled by the duplication. Because any production has multiple locations, it is how you curate these, and combine them, together with the set decoration and cinematography, that can ring the changes.

A lot of film-making is about logistics. Although Highclere Castle happens to be

both the exterior and the interior of Downton, it is perfectly normal to switch these things around and film the exterior of one building and the interior of another.

When a setting is particularly complex and the real thing just doesn’t quite exist as the script demands, then an on-screen setting can be a combination of multiple locations, giving the appearance of a single place in the finished show.

Woe betide the director who selects one location in the Highlands of Scotland and another in south-west England. In that scenario, we lose at least a day’s filming time getting from one location to the other, with trucks being driven through the night.

We like to cluster locations together and make a company move as infrequently as possible. A film crew is an enormous circus and there is no point us choosing the ideal-looking location if we can’t get all our machinery and personnel there easily. At times roads are even built!

There were some mumblings in Somerset when we decided to film Lorna Doone in the Brecon Beacons in 2000. We filmed right out in the wilds during the fuel-tanker drivers’ strike and came perilously close to running out of fuel.

The joy of location hunting is about landscapes and architecture, both in abundant supply in this country.

The BBC series Spooks was set inside MI5, supposedly. Shooting such a high-profile series on the street outside MI5’s real headquarters Thames House in Millbank would have been logistically impossible. So, we found an alternative central London building of the same era, in similar Imperial Neo-classical style, Freemasons’ Hall in Covent Garden, which doubled as our intelligence base.

In recent years, advances in visual effects have made so many things

possible that could not have been achieved before. Another challenge was our 2019 production of Belgravia. The SW1 postcode, with the majority of the capital’s embassies, plenty of high-end residences and busy traffic, absolutely prohibited filming on any scale.

I asked my colleague Donal Woods, also the Downton production designer, if we couldn’t make a show called Belgravia in Belgravia, then how could we do it?

On his laptop he showed me pictures of Edinburgh’s New Town, with the obvious flaw that the stone buildings are not stuccoed – the signature look for Thomas Cubitt’s Belgravia development.

Furthermore, a large number of houses in Belgravia have rather grand porticoes, where in the New Town they tend to be flat-fronted. He then revealed images where the ‘stucco’ was artificially added on afterwards. And so, all the exteriors were filmed in Edinburgh, with white stucco and entire porticoes added on digitally. The results were remarkable.

As with cinematography, costumes and music, locations are one of the main components of the toolbox to create a film or television show. The possibilities really are endless and they change our own perception of the landscapes and built environments in which we live.

And we are so blessed in these islands. For an American or global audience, the appeal of Downton Abbey, The Crown or Bridgerton is their mystique. But, in this country, none of us live far from beautiful and historic locations.

Some are frequently – or famously – seen on screen, but many more are waiting for their moment in the limelight. We live among pictures and stories.

The Oldie September 2023 17

Gareth Neame is the producer of Downton Abbey

London Scottish: Belgravia was filmed in New Town, Edinburgh

You can’t have it all

Women are told you can be a good mother and have a dazzling career. It’s an impossible dream, says Charlotte Metcalf

Apsychotherapist once told me that around half her patients were middle-aged women trying to come to terms with not having children.

As someone who almost missed motherhood myself, I was struck by this and began wondering why my generation of female oldies had been so easily seduced by the idea of having it all when, simply, we could not.

When I arrived at Cambridge University at the end of the Seventies, there were still far fewer women than men. Those of us who’d somehow barged our way into this male-dominated bastion were made to feel like high-achieving pioneers, convinced we’d go on to have glittering careers, unlike most of our mothers.

My mother, a highly intelligent, competent woman, neither attended university nor worked. She was so in awe of my ability to enter a hallowed academic institution, an opportunity never presented to her, that she didn’t think it was her place to discuss life’s basic but important concerns with me. Only very occasionally did she suggest I should not leave it too late to have children.

After university and a sojourn in movies and pop videos, I became a documentary director. I travelled the world with my camera, congratulating myself on having a fascinating, fulfilling career. I’d bought a one-bedroom flat with a small mortgage in my mid-twenties and was earning enough to take holidays in nice hotels.

One day, I was filming in an African village and a group of women asked me how many children I had. I confessed that I had neither children nor husband.

‘Oh no! So then you having nothing!’ they wailed with pity. I ignored the niggling anxiety this exchange rendered and instead regaled guests at my 40th birthday party with the story, insisting friendship was the only necessary ingredient for having it all.

Allison Pearson’s 2003 book I Don’t Know How She Does It shed a harsh, unforgiving light on juggling motherhood and career. Wealth buys nannies and a supportive infrastructure, but it can never buy back those precious moments watching children’s first steps, the school plays, the sports day mini-triumphs.

For me, the book was proof that I’d made the right decision not to have children. Yet it was an omission rather than a decision, and, for all my stimulating, globetrotting jobs, I was miserable.

It was with joy that I discovered I was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter and inherited a stepdaughter in my forties. I thought my freelance career would be flexible enough to grant me the best of both worlds, but all too fast I floundered.

I was once filming at a Chinese takeaway on an Essex council estate under siege from a gang of racist boys.

It was around 1am and the children, aged between ten and 12, were becoming increasingly rowdy, threatening and taunting the beleaguered brothers who ran the place. I already had some good footage but I knew if I stayed another hour, I’d capture some even better, harder-hitting shots. Yet I left, yearning to return home to my baby. I hadn’t done my best work, but then arrived home too late to be of any use.

I’d failed at both job and motherhood.

To be a good film-maker demands grabbing a camera and leaving the house whenever the story demands.

Even with all the nannies in the world, who as a mother is ever really emotionally ready to leave a child’s bedside, birthday party or piano recital?

Motherhood makes you soppy. I used to be tough enough to point my camera at almost anything and made numerous films about female genital mutilation. With daughters, I’d become fearful, upset and emotional.

I became a journalist instead, believing this would allow me more time at home and less stress. I underestimated how hard it was to break into newspapers and magazines. On top of that, print journalism was floundering, migrating online. Pay was – and remains – pitiable.

There are of course many mothers in lucrative, leading roles today. My generation’s ‘have-it-all’ pin-ups are Nicola Horlick and Ursula von der Leyen (pictured), President of the European Commission with her seven children.

But lockdown made millions rethink their work-life balance. Now, as costs spiral and the recession bites, what’s really going to make us happy? A huge job will keep a decent roof over our heads but it detracts from the time with family and friends that keeps us sane.

Socrates had it right all along: ‘The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less.’

My daughters face paying half their salary on rent and crippling university loans. They can’t envisage ever earning enough to buy a flat. Despite their generation’s collective anxiety, their expectations are more realistic than ours were. Without such an emphasis on over-achievement, they could end up being happier. My life has demonstrated that striving for it all is a sure route to failure.

18 The Oldie September 2023

Charlotte Metcalf is editor of Great British Brands

How does Ursula von der Leyen do it?

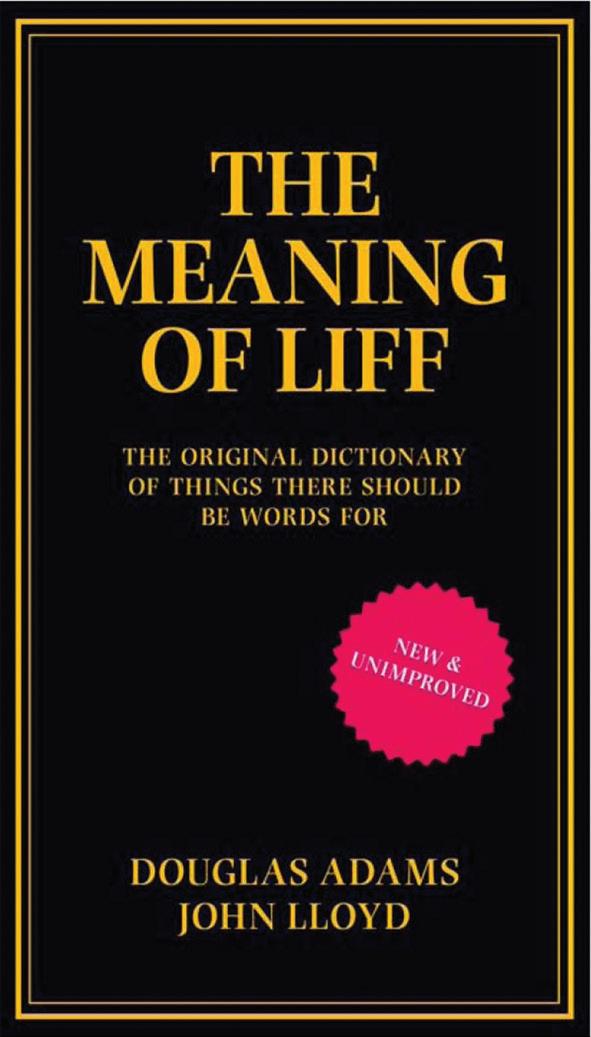

Forty years ago, John Lloyd wrote The Meaning of Liff with Douglas Adams – despite a huge row over their previous collaboration

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Dictionary

In my early twenties, my best friend was a tall, clumsy genius called Douglas Adams.

In 1978, he had got stuck writing the first series for BBC Radio 4 of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and asked me to help him finish it.

We’d written together often before –so I said yes.

‘I don’t suppose there’ll be a second series, Johnny,’ he said, ‘but, if there is, let’s do it together.’

It had taken Douglas 10 months to write the first four scripts, but we polished off the last two in three weeks.

The series was an instant success and, before it had even finished going out, we’d been invited to lunch by no less than six publishers.

We signed with Nick Webb at New English Library for £3,000 – half for each of us – and booked a month’s holiday in Corfu to write it.

Then Douglas sacked me. He’d decided the episodes we’d written together weren’t as funny as the ones he’d written on his own.

I was blindsided, heartbroken and furious. I couldn’t even look at him. ‘Are you all right, Johnny?’ he asked solicitously. And when I made it very clear I wasn’t, he said, ‘Why don’t you get yourself an agent?’

So I went to see the redoubtable Marc Berlin, still my agent today and known (for his tough negotiating skills) as ‘The Berlin Wall’.

He ran London Management, the largest entertainment agency in the country, and told me gleefully, ‘We can take this guy for 10 per cent of anything with the name Hitchhiker on it for the rest of his life!’ I was appalled.

‘No, no,’ I said, ‘I just want my half of the advance for the book.’ And we settled on that, though Douglas wasn’t pleased.

‘When I said, “Get yourself an agent,”

he yelled, ‘I meant, “And write your own bloody book!” ’

Astonishingly, given the acrimony between us, we set off for Greece together.

It was odd to begin with. Douglas would get up in the morning and sit at a table on the terrace in an enormous Terry Pratchett hat and start writing, while I went down to the windswept taverna on the beach from where the Great Novelist was visible to all.

By about 11am, the GN was creatively

exhausted. He’d trudge down the hill and we’d tuck into a bottle of retsina and play games. Our favourite was one Douglas’s old English master had introduced to his class in free periods, or at the end of term. ‘What do you think Epping means?’ he’d say. Or ‘What do you think an Ely might be?’

Ely was the first definition we came up with – ‘The first, tiniest inkling that something, somewhere, has gone terribly wrong.’ It was so neat, so useful and so satisfying that we became hooked. I

JILL FURMANOVSKY VIA ROCKARCHIVE.COM

20 The Oldie September 2023

Adams and Lloyd: ‘Imber’ – lean from side to side while watching a cinema car-chase

kept notes of all the best ones.

Douglas failed to finish the book on that trip, and I went off to television to produce Not the Nine O’Clock News

In 1981, Robert McCrum, the editorial director of Faber & Faber, got in touch about publishing a spin-off joke-a-day calendar from the show. I took on the job of editor.

Though Not the Nine employed dozens of freelance writers, finding two appropriate jokes for each day of the year (one for the front of each page and one for the back) was a huge task and I soon ran out of material. Scrabbling around for ideas, I found the notes of my chats with Douglas in 1978 and was surprised at how good the lines were.

Kettering n. The marks left on your bottom or thighs after sitting sunbathing on a wickerwork chair.

Silloth n. Something that was sticky and is now furry, found on the carpet under the sofa the morning after a party.

Motspur n. The fourth wheel of a supermarket trolley which looks identical to the other three but renders the trolley completely uncontrollable.

I put these into the book – which was called NOT 1982 – under the heading ‘Today’s new word from The Oxtail English Dictionary’.

When the proofs came out, Faber’s chairman, Matthew Evans, said, ‘There’s one idea in here that stands out and could make a book in its own right – the dictionary definitions.’

I told friends about this and soon had a peremptory message from Douglas: ‘Do nothing before you speak to me.’

So we wrote it jointly, co-published by Faber and Douglas’s imprint, Pan. By then, Douglas was an international

The Meaning of Li Glossary

Aalst n.

One who changes their name to be nearer the front.

Ahenny adj.

The way people stand when examining other people’s bookshelves.

Albacete n.

A single, surprisingly long hair growing in the middle of nowhere.

Articlave n.

A clever architectural construction designed to give the illusion from the top deck of a bus that it is far too big for the road.

Berriwillock n.

An unknown workmate who writes ‘All the best’ on your leaving card.

Fulking vb.

Pretending not to be in when the carol singers come round.

Grimbister n.

Large body of cars on a motorway all travelling at exactly the speed limit because one of them is a police car.

Harmanger n.

The person who takes the blame while the manager you demanded to see hides in his o ice.

Kentucky adj.

Fitting exactly and satisfyingly. The cardboard box that slides neatly into a small space in a garage, or the last book

which precisely lls a bookshelf, is said to t ‘real nice and kentucky’.

Lamlash n.

The folder on hotel dressing tables full of astoundingly dull information.

Ockle n.

An electrical switch which appears to be o in both positions.

Peoria n.

The fear of peeling too few potatoes.

Polperro n.

The ball, or mu , of soggy hair found clinging to bath over ow holes.

Shoeburyness n.

The vague uncomfortable feeling you get from sitting on a seat which is still warm from somebody else’s bottom.

Spo orth vb.

To tidy up a room before the cleaning lady arrives.

Stebbing n.

The erection you cannot conceal because you are not wearing a jacket.

Symonds Yat n.

The little spoonful inside the lid of a recently opened boiled egg.

Woking vb.

Standing in the kitchen wondering what you came in here for.

smash, with Hitchhiker books selling by the million. In meetings with the publishers, my suggestions were met with polite indifference and Douglas’s with rapturous admiration and applause.

I wanted the cover to scream, in bold letters: ‘DOUGLAS ADAMS – THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GLOSSARY.’

I couldn’t have cared less where, or how small, my name appeared. Douglas, however, insisted on calling it The Meaning of Liff. This was because Monty Python had just released their film The Meaning of Life and he figured we might get extra sales from myopic people who thought it was the book of the movie.

To do him justice, he also insisted on equal billing (even though I argued no one would care, or even notice).

Then there was the sizing. I was happy for it to be in a standard format, but Douglas was adamant it should be small enough to fit in a breast pocket. And completely black, like a prayer book.

That was what happened, even though creating a unique size cost the publishers money and annoyed booksellers because it was almost invisible to the naked eye.

Nonetheless, the first run sold an amazing third of a million copies – or, as Douglas despondently put it, ‘only a third of a million’. It was well below the pay grade he’d become accustomed to.

The one advantage of the sizing was that we were able to adorn the back of later editions with three crisp reviews: ‘Brilliant’ – the Times; ‘Brilliant’ – the Sunday Times’; and ‘Small’ – the Cheshunt & Waltham Telegraph.

Douglas died in 2001, impossibly young, at only 49. I have never borne him any ill will. Quite the reverse.

I have a saying I try to live by: Disaster is a Gift. If Douglas hadn’t fired me from Hitchhiker, I’d probably never have done anything else and would have just been ‘that bloke what’s-his-name who works with Douglas Adams’.

Only the other day, a good friend of mine asked me if I’d ever read a book called The Meaning of Liff

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I wrote it.’ He looked astonished and pulled his dog-eared copy out of his pocket. He stared at the front cover in disbelief. ‘Good Lord,’ he said, ‘I’d never noticed…’

John Lloyd and Douglas Adams wrote The Meaning of Liff – the Original Dictionary of Things There Should Be Words For (Boxtree)

fit was the The Oldie September 2023 21

Je t’aime

The actor Simon Williams had a teenage romance with the late Jane Birkin – and was utterly bewitched by her

Andrew Birkin, Jane Birkin’s brother, and I were illicit smoking buddies at Harrow. His mother, Judy Campbell, and my father, Hugh Williams, were West End stars.

Judy performed A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square – perhaps it was from her that her daughter Jane learnt the subtle skill of not-singing.

Best of all, Andrew had a sister, Jane, whom I fell in love with before even meeting her. I too had a sister, Polly, and we soon became a foursome.

It was a special time – we were innocents halfway out of childhood – we played it cool, we jived and blew smoke rings; we played kick-the-can.

One Easter holiday, Andrew wrote a short film, a tragic story of a toff who falls in love with a working-class girl who is incurably ill.

We spent the holidays filming in Chelsea and on the Downs – it involved endless chasing – me grossly anguished in pursuit, and Jane breathless, pitiful and then dead in my arms.

Andrew very sweetly wrote in a love scene to be filmed on the boating lake in Battersea – which turned into a blissful afternoon of licensed kissing with many retakes. When they showed a clip of the film on my This is Your Life in 1986, Jane spoke from the heart about our precious childhood days.

The atmosphere in the Birkin household in Chelsea was not unlike the home of the Bliss family in Hay Fever I would pitch up in my tweed jacket and sit gazing at Jane – not easy as I always whipped off my National Health glasses. It was puppy love, of course – never really reciprocated – but she wasn’t averse to being worshipped even then.

I once found Jane and her father, the heroic David Birkin, drinking champagne and giggling. I had no clue what they were celebrating.

Years later, Jane told me the celebration was for her first period – she had been the last in her year to get it.

She would take me up the King’s Road pointing out all the astounding swinging people – long-haired beatniks, and everyone in bright colours determined to forget the war.

We went to see Audrey Hepburn in The Nun’s Story. Darling Jane had tears pouring down her cheeks and I loved her with a terrible ache – very slowly I put my arm round her.

There’s always been a gamine quality of Audrey Hepburn in Jane – gauche and elegant at the same time.

During the term, she’d send me little sketches of herself lolling about at home. I’m looking at one now of Jane with hair back-combed lying on a chaise longue with her parrot beside her, the walls covered with trendy pics.

When Jane first went to (and fell in love with) Paris, she was living en famille. I would hitchhike up from Tours where I was supposedly studying, and we’d spend hopeless afternoons wandering along the Seine trying to work out how to become movie stars. I gave her a Françoise Hardy LP.

She had a 7pm curfew and I told her

I was staying with friends and spent my nights in the waiting room at Gare Du Nord. In the morning, I’d wait outside the gates of her house with two pains au raisin. In terms of romance, we were in no-man’s-land. I had no idea how to move things forward and we lapsed into an on-off friendship that’s lasted ever since – founded mostly on nostalgia.

Jane went to improv classes at the Royal Court and became enthralled with the avant-garde. She was cast in The Passion Flower Hotel in 1965, the grooviest musical in town, while I was stuck playing the juvenile in drawingroom comedies. I would see her across the dance floors of West End nightclubs with men I never imagined to be her type – she was the beauty to a variety of beasts.

When she auditioned for and got a part in Blow-Up, Jane was nervous about the nudity required of her. ‘My tits are just minuscule,’ she laughed.

I had dinner with her after her first day’s filming in the nude and she was bubbling with liberation. Once she’d taken her dressing gown off, she said it was a piece of cake – ‘I walked about all day totally naked and nobody seemed to even notice.’ I bet they didn’t.

I’ve watched and marvelled at the variety of Jane’s life, the extraordinary choices she made of projects and partners, and the way she tapped so easily into the zeitgeist of Paris life and became an icon, a rebel with many causes. But she never lost her waif-like innocence or the ability to not take herself too seriously – she never lost the giggle of the teenager I had worshipped.

The newspapers say that she eventually gave up on love and was perfectly happy living alone. Maybe not. I remember her once quoting the famous Tennyson line: ‘It’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.’

We shook our heads – we weren’t so sure about that.

The Oldie September 2023 23

Simon Williams starred in Upstairs, Downstairs

Thrill of the chaste: Simon Williams, 17, and Jane Birkin, 16, in Paris, 1963

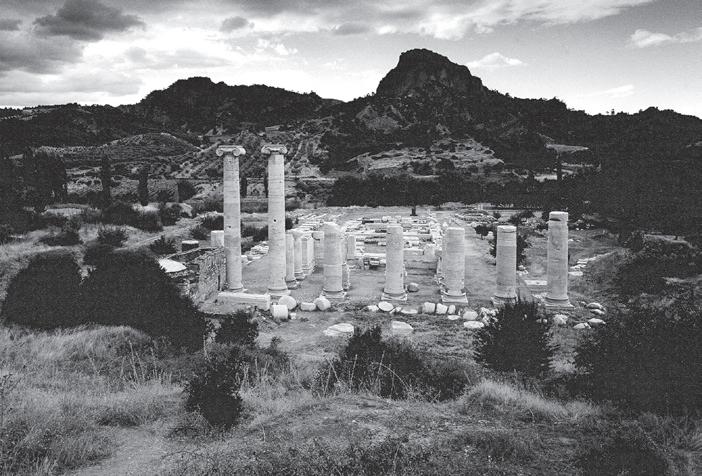

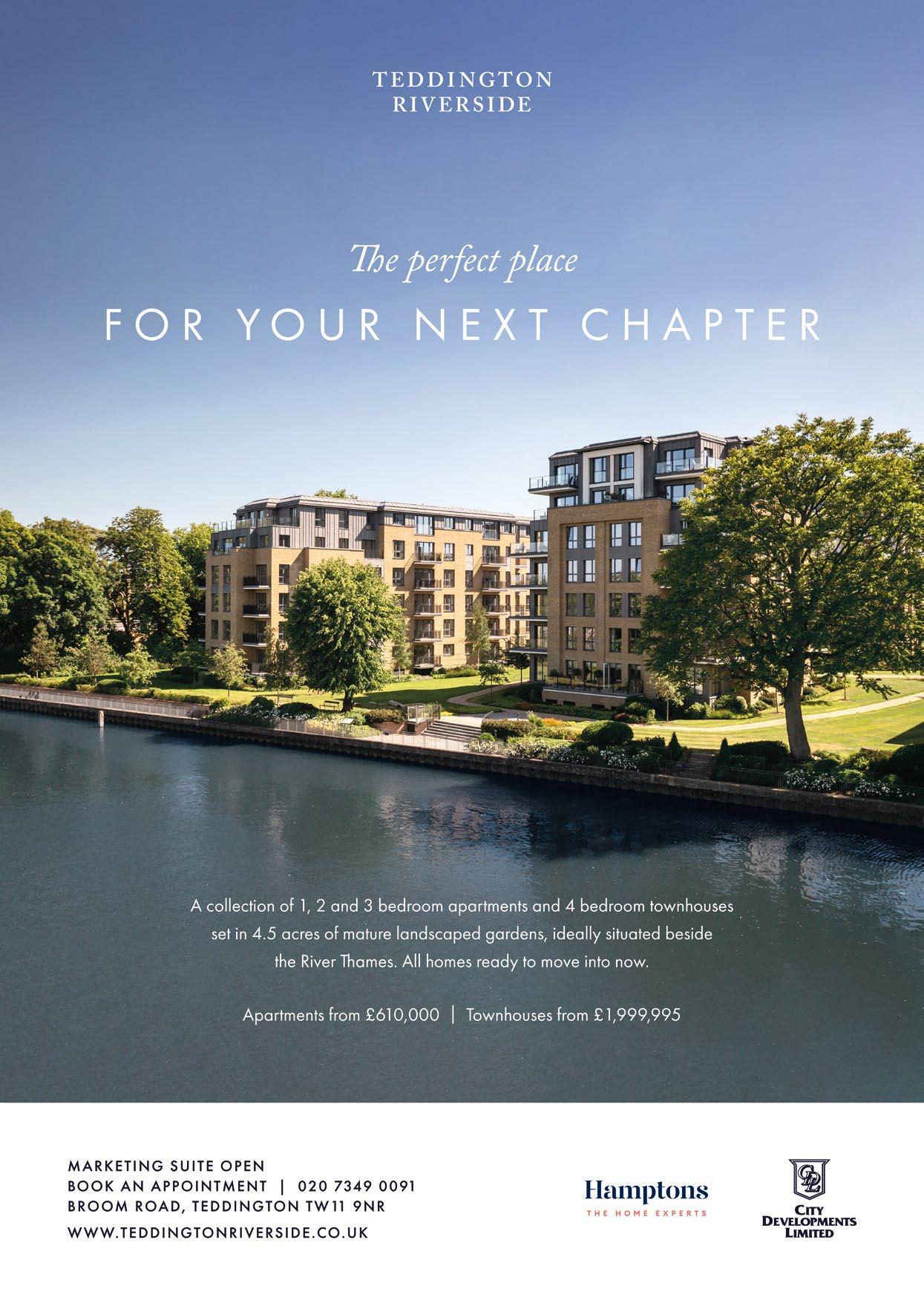

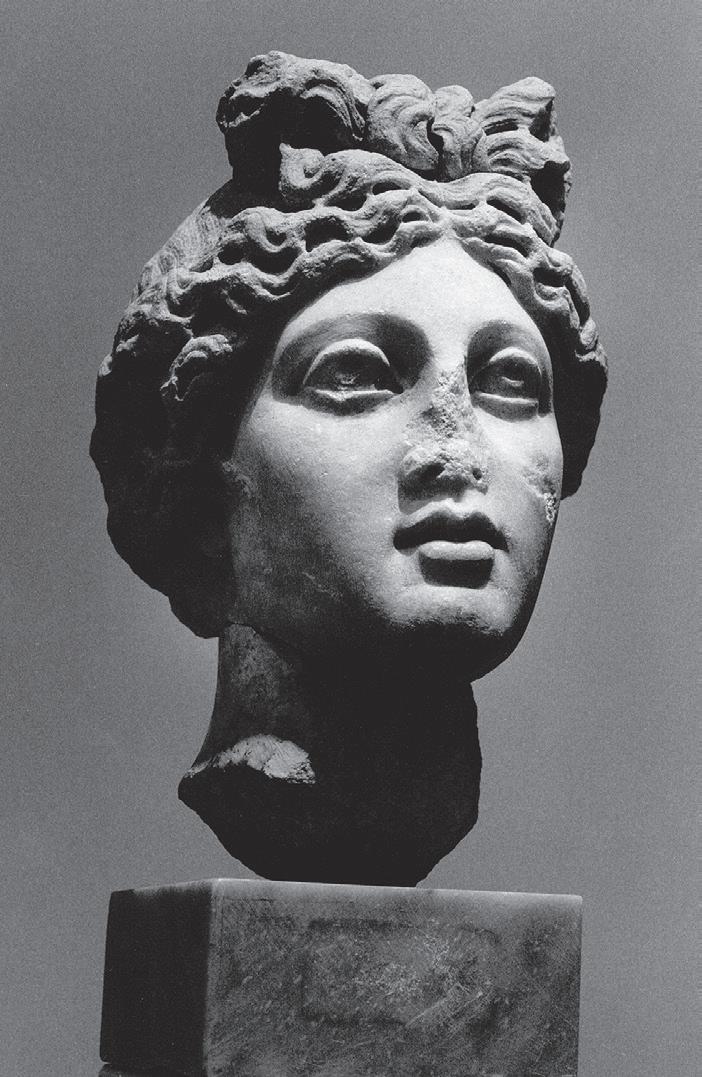

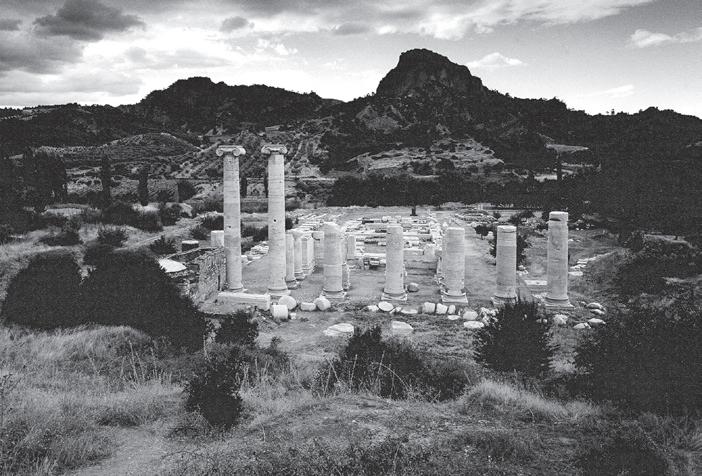

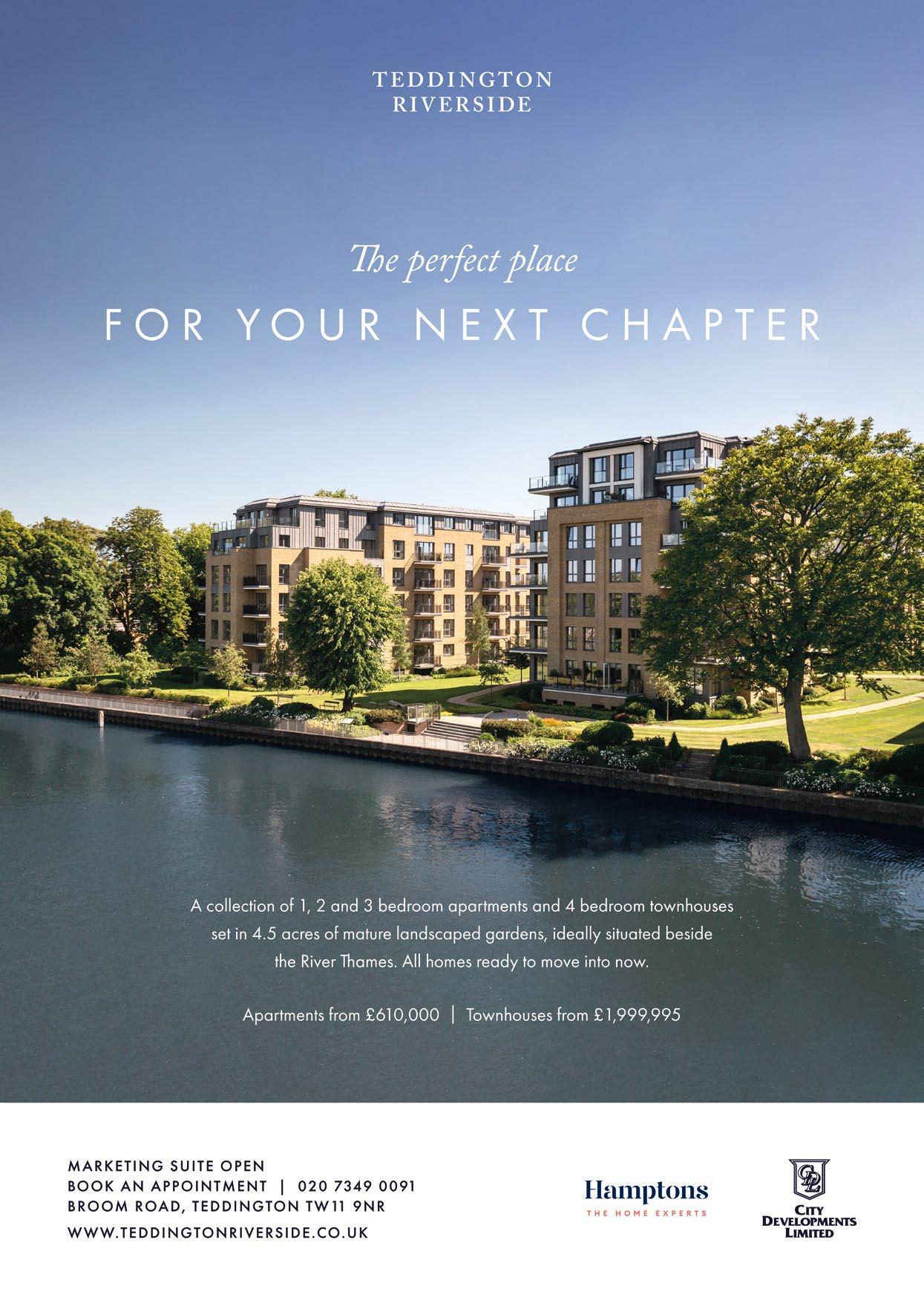

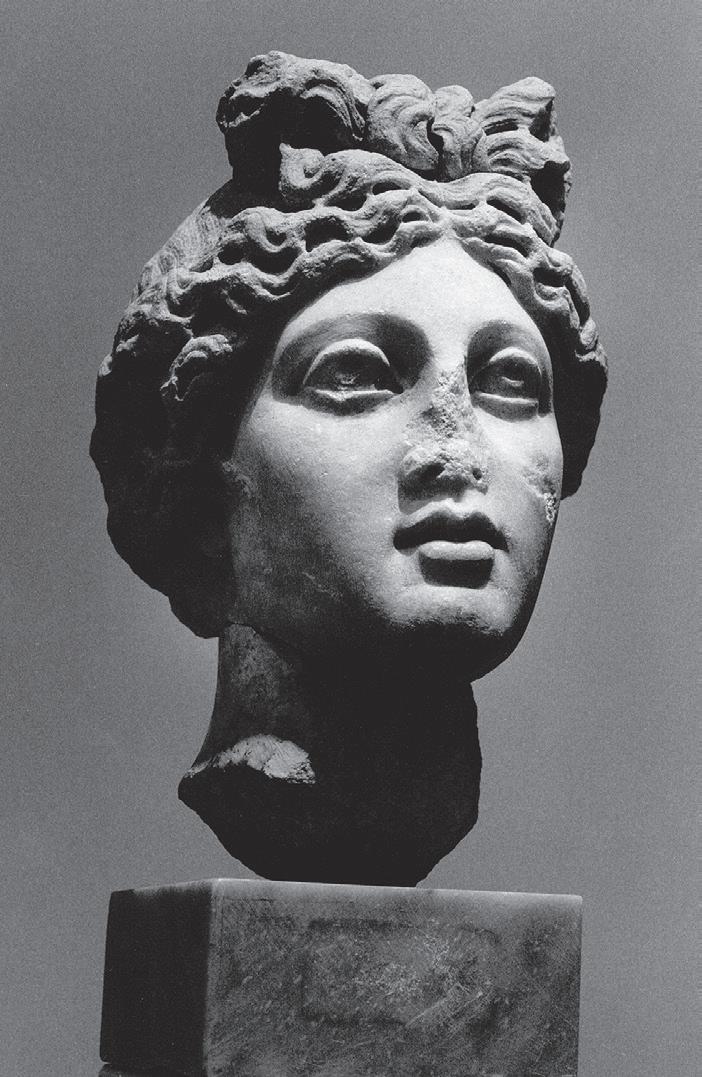

Don McCullin, 87, Britain’s greatest war photographer, turns his lens to the heavenly ruins of Asia Minor

My Turkish Odyssey

Ihave been travelling the world for the past 65 years – so I can’t explain how Turkey evaded me until recently.

A couple of years ago, I had the great pleasure of meeting the charming Turkish Ambassador to London at the time, Ümit Yalçın, and it was with his blessing, and alongside my dear friend, the author Barnaby Rogerson, that we embarked on a series of journeys to discover the remains of Roman Turkey. These, I thought, have been somewhat overlooked in a country so full of other historical treasures.

The ambassador opened all the most important museum doors for us, which was marvellous, and I was lucky that Barnaby was a fount of knowledge on the history of these sites.

I remember how I couldn’t get over the beauty of the exhibits at the Istanbul archaeological museums and didn’t know where to start.

The museum in Antalya was equally eye-opening, with the most impressive display of huge Roman figures and some of the best and most creative lighting I have seen in any museum, thanks to the director, Dr Candemir Zoroğlu, who studied for two years at the British Museum.

I realised I would need a whole lifetime to document Roman Turkey, as there are simply hundreds of sites waiting to be discovered. Sadly, I am past the age where this is possible, without the strength to clamber over beautiful temples and amphitheatres. A misplaced foot, as I have found to my cost in the past, can be dangerous.

I felt so rewarded by the visual feast presented to me, but also by the warmth and welcome of the people.

DON MCCULLIN

26 The Oldie September 2023

Don McCullin’s Journeys Across Roman Asia Minor (Cornucopia, 1st September), commentary by Barnaby Rogerson

Left: Early Roman Imperial agora, Sagalassos

Below: Agrippina crowning Nero in the Sebasteion, 1st century AD, Aphrodisias

MONICA FRITZ The Oldie September 2023 27

Head of Aphrodite, 2nd-3rd century AD, Aphrodisias

The fourth-largest Ionic temple in the world: the Hellenistic and Roman Temple of Artemis, Sardis

Don McCullin and Barnaby Rogerson by the Roman aqueduct at Aspendos, 2nd-3rd century AD

Throw caution to the wind

The best decisions in life are made on the spur of the moment, says Piers Pottinger

Spontaneity can be wonderful. Several years ago, I was at Deauville Races on a glorious Normandy summer’s day.

Despite hours of homework, my selections had all failed to cross the winning line anywhere near the front. In the last race, I had ten euros left and decided on the spur of the moment to throw caution to the wind.

I picked four horses at random to finish in the correct order in the first four places – a real long shot. To my astonishment, it came off. My wife and I enjoyed a splendid dinner at Deauville’s finest restaurant that evening. In more than 50 years of backing horses this was, sadly, a unique experience.

Some of the most memorable moments in sport have originated in a single, spontaneous piece of skill: the inspired pass in rugby, the sensational shot in golf or the unexpected goal in football. Hours of training and meticulous planning become insignificant when a Messi, Seve or Gareth Edwards produce the moment of magic.

The same applies in comedy, where the term ‘ad lib’ is short for ad libitum, Latin for ‘according to pleasure’.

Jimmy Carr today and Max Miller, in the music-hall days, had the gift. Frankie Howerd could not ad lib, even if his carefully rehearsed asides often appeared spontaneous. He said the best ad libs were the ones he had practised longest.

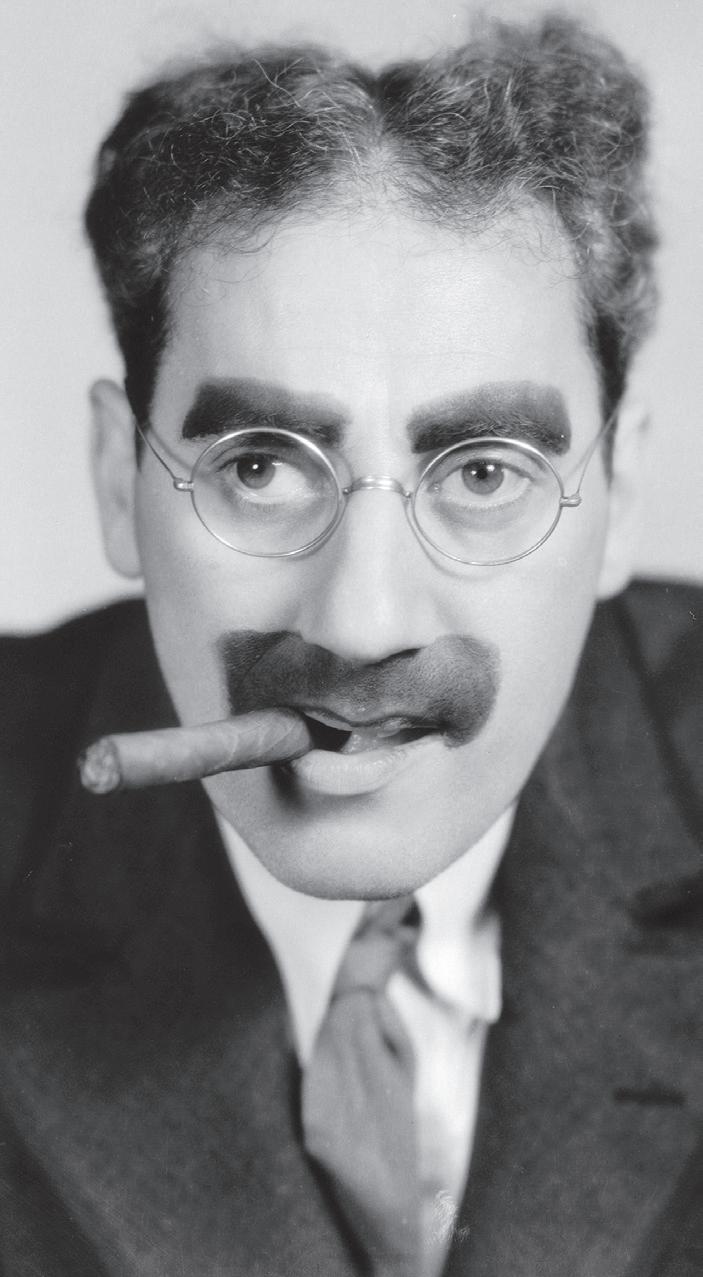

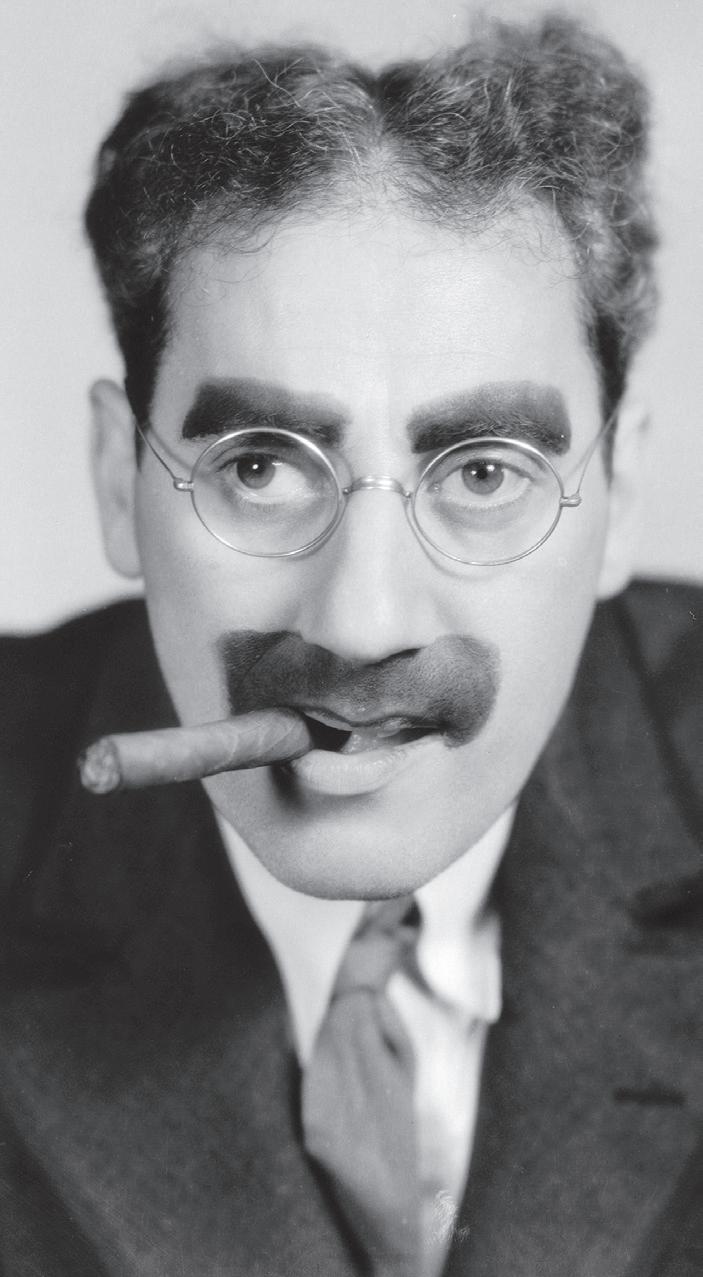

The master of the wisecrack, Groucho Marx, hosted a television show in the early 1950s where, each week, he would have a guest who had done something unusual. One week, this was a formidable lady who had had 17 children.

When asked by Groucho why, she said, ‘The answer is simple, Mr Marx. I love my husband.’

Without missing a beat, Groucho was rumoured to have said, ‘Well, I’m kinda fond of my cigar, but I take it out of my mouth sometimes.’

It was television in a prudish era, and

it is believed the notorious quip was edited out before the show was aired.

Great artists add a flourish at the last minute to enhance their work.

In 1446, Petrus Christus added a fly, seemingly sitting on the frame, to his Portrait of a Carthusian. Turner added a last-minute splash of red to his painting Helvoetsluys on the eve of the Summer Exhibition of 1832 – simply to irritate his great rival, Constable.

My late uncle, Don Pottinger, was one of Scotland’s top portrait painters. He would spend months on a single portrait. Yet he admitted he often captured the true essence of his subject best in the lightning-fast first sketch.

‘I’ve got it!’ he’d shout.

He felt that the best portraits looked as if the subject was almost conversing with the artist. A wonderful Rembrandt self-portrait in the National Gallery of Scotland epitomises that thought.

Even in the normally staid world of

business the occasional spur-of-themoment gesture can be effective. The great tycoons were often flamboyant characters who revelled in making spontaneous gestures.

Lord Fraser of Allander, the original Hugh Fraser of House of Fraser, was legendary for his humanitarian gestures and sometimes his more commercial ones. He was once asked at a dinner if he felt his business was too Scotland-centric. He replied, ‘See what happens tomorrow.’

The next morning, he announced to his board that he was going to buy Harrods. He did.

The most dangerous – indeed terminal – form of spontaneity is spontaneous human combustion. Larry E Arnold, director of ParaScience International, recorded in his 1995 book, Ablaze!, that there had been 200 cases over the past 300 years.

In 1746, Paul Rolli of the Royal Society wrote of the death by spontaneous combustion of Countess Zangheri Bandi. Described as a ‘large, dull woman’, she frequently doused herself with camphorated brandy to clear her multiple skin blemishes. She also consumed two bottles of brandy a day.

She was found as a pile of ash one morning by her maid, after sitting by her bedroom fire to enjoy a nightcap before turning in. As she was probably almost entirely composed of brandy, it’s likely that the fire ignited the alcohol, causing the fatal explosion.

Most recent cases of supposed spontaneous combustion are explained by doctors as being caused by copious intakes of alcohol. Worth bearing in mind when a friend suggests ‘One more for the road?’ and you make a spur-of-the-moment decision.

The Oldie September 2023 29

Very wise cracks: Groucho Marx, master of the lightning-quick riposte

From rags to rich men

Coco Chanel designed the little black dress and Jackie O’s pink suit –and had a gift for attracting tycoons. By Philippa Stockley

Today the word Chanel conjures up sugary tweeds and perfume.

In fact, Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel was the 20th century’s most influential designer. During a 60-year career, her designs shaped generations, from the 1926 little black dress to the famed suit of the Fifties. She died in the Ritz in 1971, aged 87, after working all day.

And now a new V&A show is paying tribute to her genius.

Chanel used rich and aristocratic men as a climbing frame to bankroll and promote her. She constantly refreshed her designs, running an empire by her forties, and outlived all her competitors.

But her meteoric rise had a dismal start. She was born illegitimate to market traders in 1883. Her mother died when Chanel was 11 and her father sold her two brothers and dumped her and her sisters in an austere Catholic orphanage. They never saw him again.

So began a lifetime of lying: about her background (rich, loving father, rich aunts); her age (she knocked years off, even in her passport); and her abilities (she said she couldn’t sew, yet hemmed sheets at the convent, then worked at a tailor’s, adjusting soldiers’ jodhpurs).

So also began a life of work, innovation and ruthlessness, plus a constant search for a rich man to protect her.

She landed her first useful beau at the tailor’s. Womanising textile heir Étienne Balsan had a hunting lodge north of Paris. In 1905, Chanel moved in as his mistress. Thin, small and intense, in her early twenties but pretending to be younger, she wore Balsan’s clothes. Her gamine look, at odds with fashionable S-bend corsets, trailing skirts and huge hats, enchanted Balsan’s rich women-friends. She began to make hats for them.

At Balsan’s, she met ‘Boy’ Capel, whose family money came from coal. She followed Capel to Paris — yet the dumped Balsan generously loaned her his Paris apartment to open a shop in, and then sent his society friends there.

She worked hard at hats, got into magazines and, with Capel’s backing, bought her first premises, at 21 Rue Cambon. In 1912, they visited Deauville, where Boy bought another shop.

She began designing clothes with easy, loose lines; uncorseted and sporty — a revelation to women accustomed to being trussed up like chickens.

A 1916 ‘Jersey’ collection, made with a knockdown job-lot of stretchy underwear fabric, put her firmly on the fashion map: magazines raved and satirical cartoonist Sem, who was a friend, documented her clothes and glamour.

In 1919, Capel died in a car crash. In 1920, Chanel took up with the impoverished Grand Duke Dmitri of Russia, who had connections. In return, she bankrolled him. He introduced her to Ernest Beaux, the perfumer who actually created Chanel No 5 (whatever she claimed), which by 1924 was being mass-produced by the Bourjois-owning Wertheimer brothers.

Chanel only got 10 per cent, which rankled so much that in 1940 she tried to get the Nazis to close them down.

Dmitri also introduced her to the Duke of Westminster, for whom she dumped him. This massive promotion resulted in stupendous gems and a shop in Mayfair, where she offered ‘Le Style Anglais’, with exclusively woven tweed. Meanwhile, she went around in men’s cardigans and brogues, and fished with Winston Churchill. Westminster married. But now she was world famous.

Americans adored her androgynous styles; Garbo and Dietrich wore her widelegged trousers, stripy tops and berets. In 1930, Samuel Goldwyn paid $1 million for her to design for him in Hollywood. She hated it.

She employed thousands and her designs continued to evolve, from gossamer organza dresses to gold and enamel jewellery, all illustrated in leading magazines.

The war changed everything. She stopped production, but shrewdly kept her perfume shop open to retain her premises. A long affair with a former German diplomat has since raised eyebrows, but MI6 cleared her of wrongdoing.

In 1954, she staged a remarkable comeback, adored (again) by Americans, who found her styles, including the now established Chanel suit, ideal for the modern working girl. They considered ‘Mademoiselle’ a feminist. Sales spiralled.

Then came the most famous suit of all: Jackie Kennedy’s pink one, worn the day of her husband’s 1961 assassination. Even though Kennedy only wanted his wife to wear American-made fashions, Chanel fan Jackie had the pattern, fabric and trimmings sent over, and the suit was… made in America.

Chanel never missed a trick. As the Sixties rolled on, she ditched men, becoming the darling of film stars from Jeanne Moreau to Romy Schneider, who all wore Chanel in films. As the Seventies began, the old chain-smoker, in tweed suit, wig and hat, was busy designing hippy-happy, drop-waisted outfits in dazzling, clashing brocades.

Yet, secretly in 1954, she’d sold Chanel to the Wertheimers. In return, they bankrolled her. The Ritz and all her expenses were paid for by rich men, while she retained complete artistic control.

It suited her.

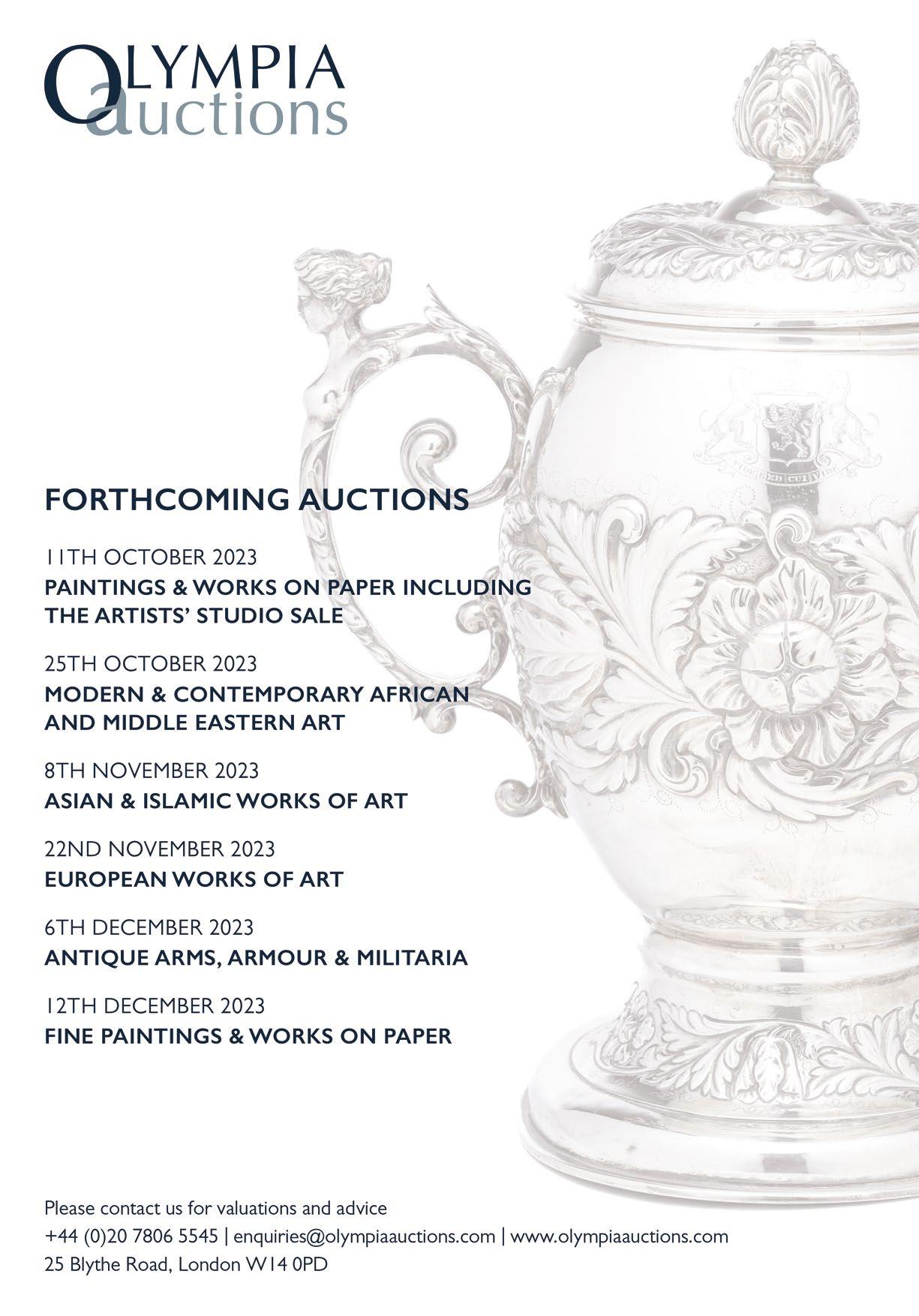

Gabrielle Chanel – Fashion Manifesto is at the V&A, 16th September 2023 to 25th February 2024

30 The Oldie September 2023

‘Mademoiselle’: Coco Chanel in 1938

Michael Cole sacked Coutts long before they sacked Nigel Farage

You’re fired!

Ten years before Nigel Farage was de-banked, I sensed it was all going wrong behind the Coutts pepperpot façade in the Strand. So I sacked the royal bankers.

It was a hard decision. I had been a member of Coutts & Co for 41 years. But I had to leave because it was no longer the bank I joined in 1972.

The manager of the Norwich Coutts office wore a frock coat, wing collar and cravat. He signed me in with his quill pen. Mr Masters then visited me at home, met my wife, opened an account for her and promised one for our baby daughter when she grew up, which happened as night follows day. It was that sort of bank, friendly but correct. We were encouraged to think of ourselves as members of a nice club, not mere customers.

Coutts didn’t indulge in gimmicks. The only ‘welcome gift’ was a brown leather wallet for the chequebook.

I had switched banks, from Lloyds, because my accountant said Coutts were ‘good lenders’. I never borrowed a penny and kept my account in credit.

I was invited to lunch in one of those pepperpot turrets decorating the frontage of the Coutts HQ. The chairman was Sir Ewen Fergusson, a former Scotland rugby international, whose size-14 feet qualified him to have his shoes made on the NHS. He was succeeded by David Douglas-Home, formerly of Morgan Grenfell, who became the 15th Earl of Home on his father’s death.

I was invited mayfly-fishing on one of Hampshire’s celebrated chalk streams. There the bank’s chief executive, Perry Littleboy, kindly encouraged a small brown trout to attach itself to my hook so that we could forget about the wretched business of angling and go to lunch.

If Giovanni de’Medici can be accused of inventing banking, Thomas Coutts (1735-1822) gave it the English patina of respectability. He cleverly distanced it from its usury by adopting a solemn facial expression in a gloomy office with a

loudly ticking clock, to disguise the fun of getting rich using other people’s money.