The real Boris Johnson by Ivo Dawnay, his brother-in-law Maggie Thatcher’s house-buying tip – Anne Robinson Elizabeth I’s love nest – Quentin Letts King of Carry On – by Roger Lewis Charles Hawtrey August 2023 | £5.25 £4.13 to subscribers | www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 429 SAVE LIVERPOOL STREET STATION! GRIFF RHYS JONES ‘The Oldie is an incredible magazine – perhaps the best magazine in the world’ Graydon Carter R . I . P. GLAMOUR BY CHARLOTTE METCALF

Features

Books

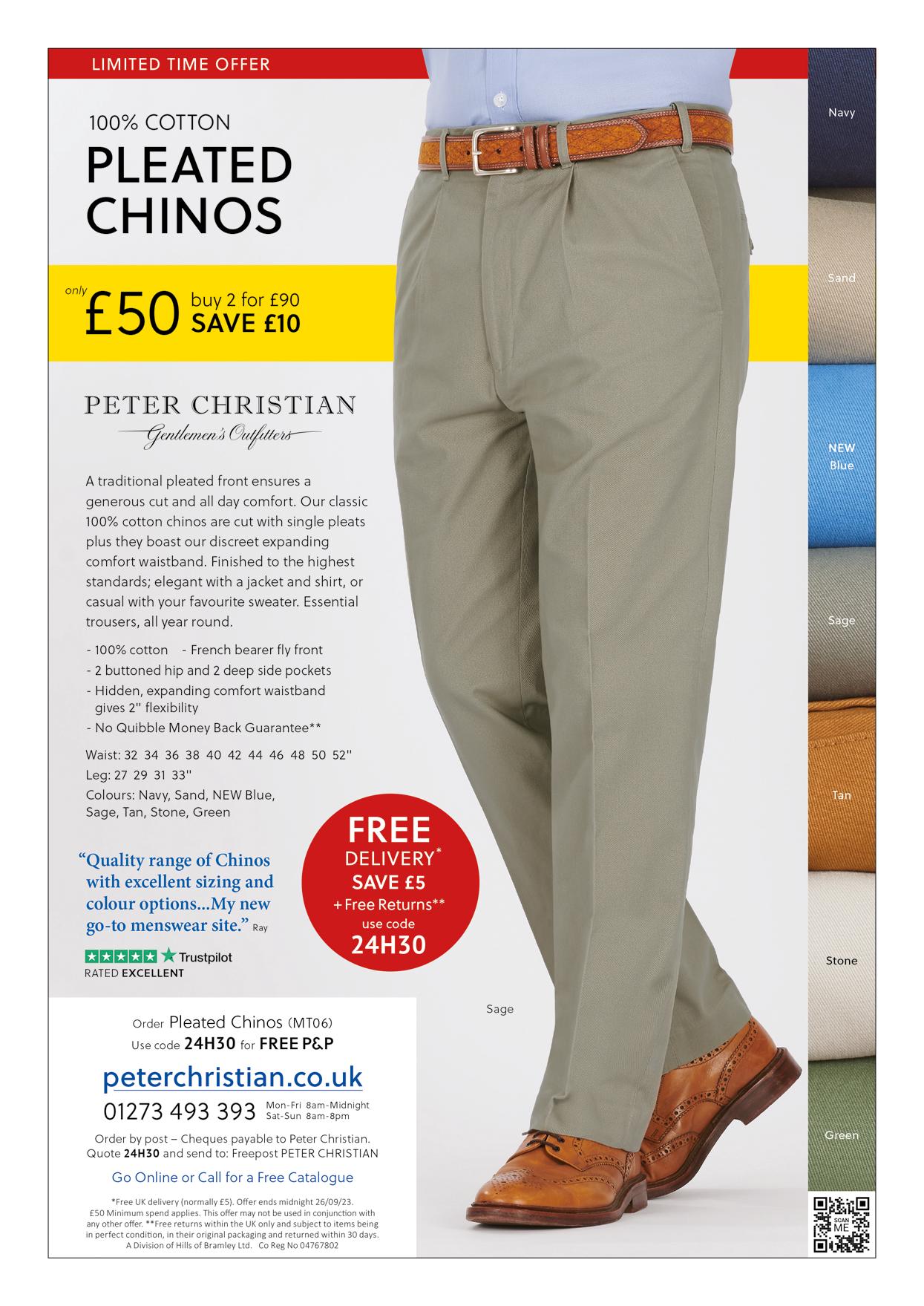

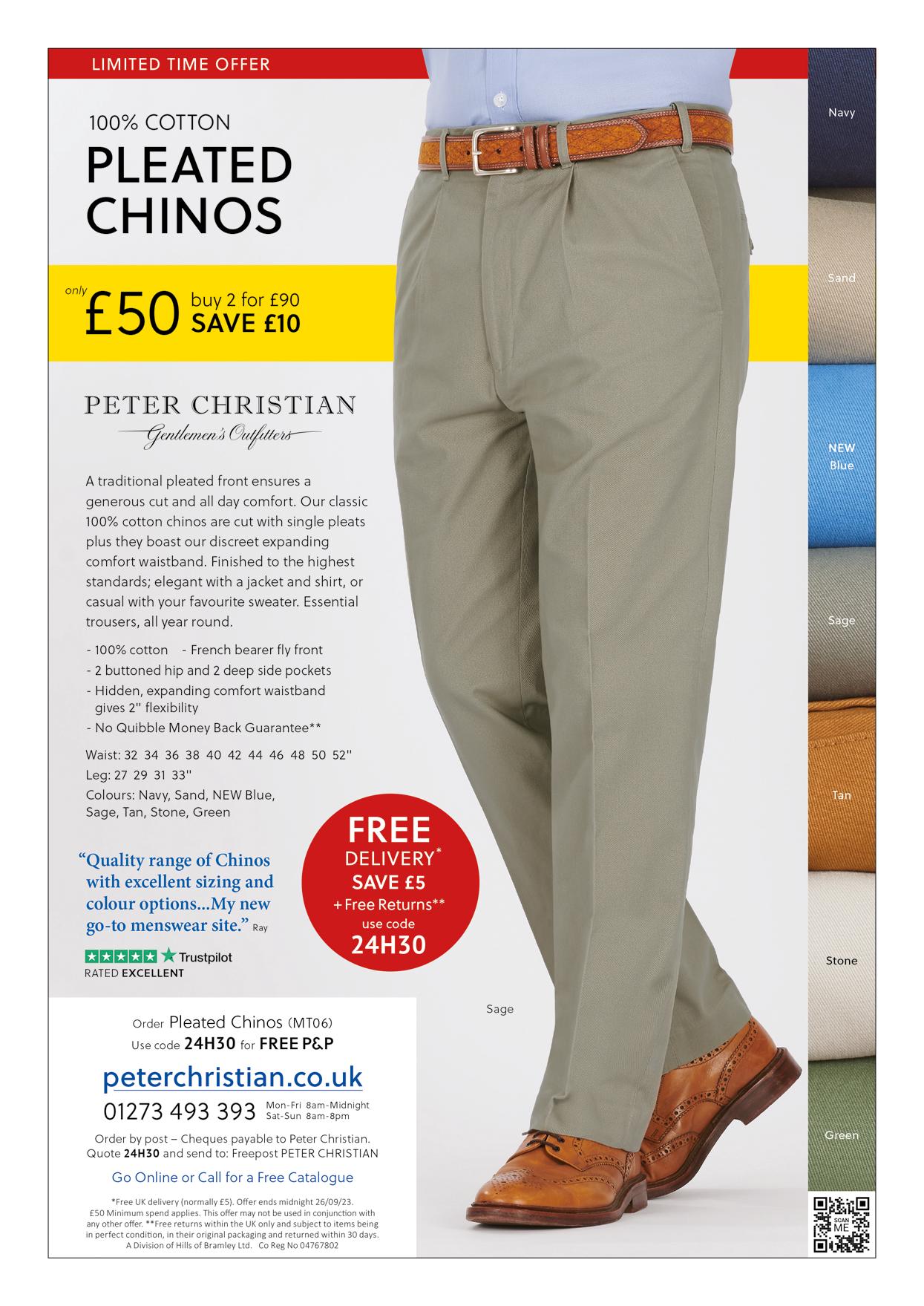

54 Big Caesars and Little Caesars: How they Rise and How they Fall, by Ferdinand Mount

Ivo Dawnay

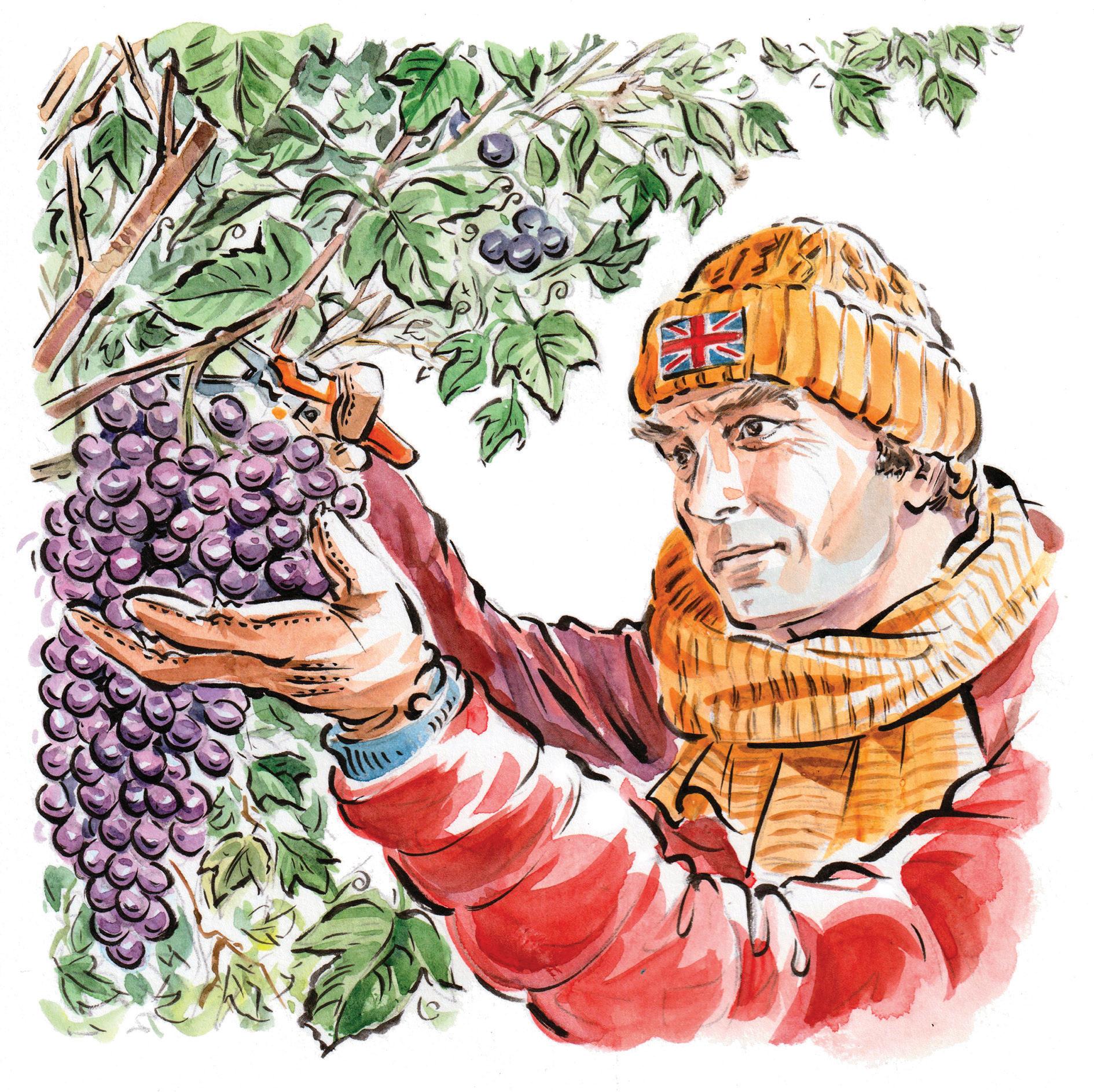

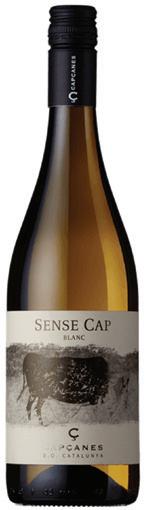

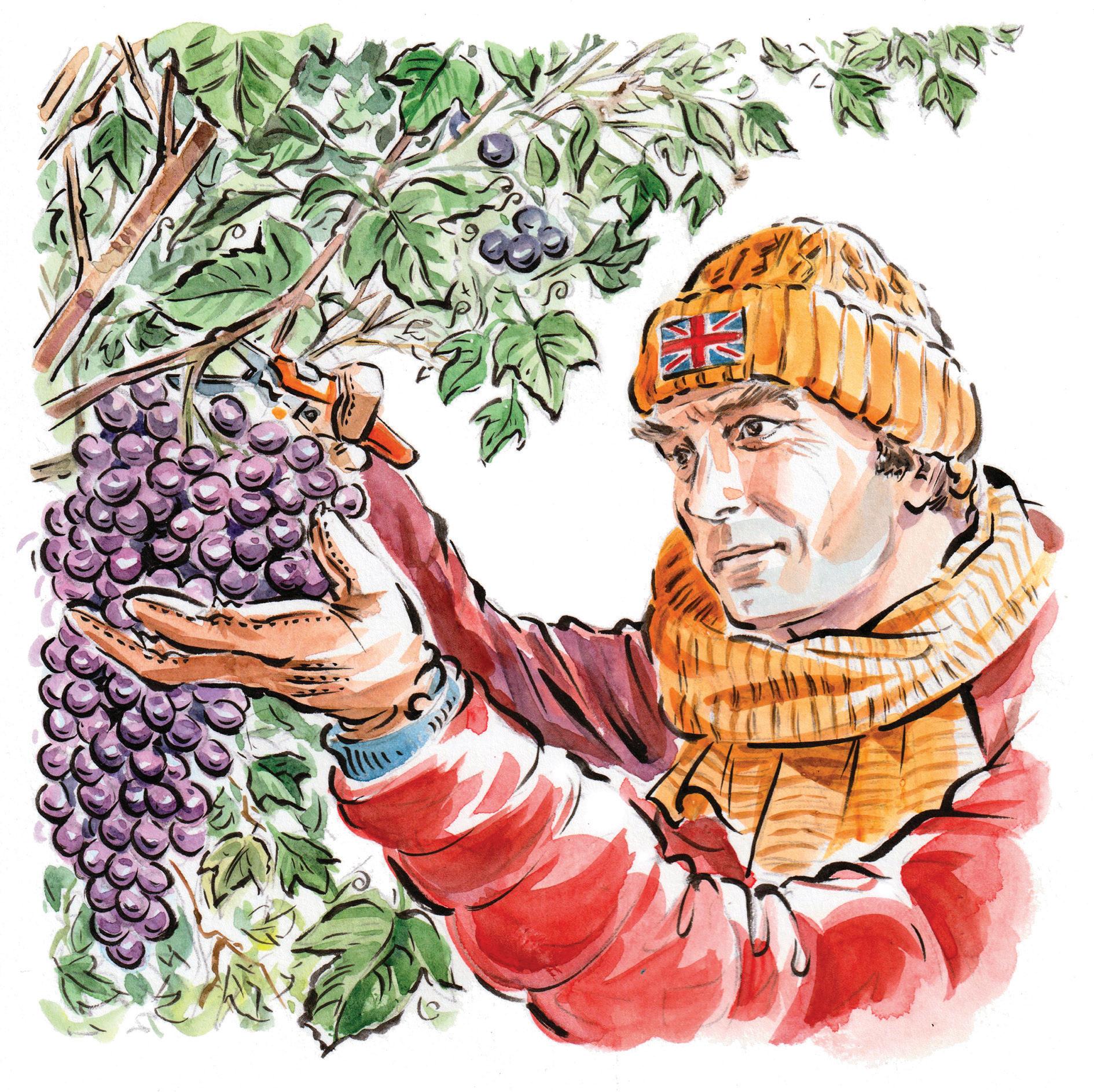

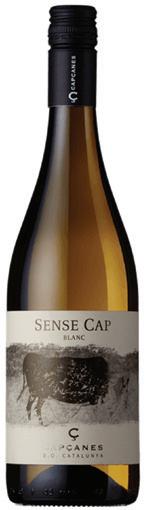

57 Vines in a Cold Climate, by Henry Jeffreys

Bill Knott

59 Last Post, by Frederic Raphael Nicholas Lezard

59 Metropolitain: An Ode to the Paris Metro, by Andrew Martin Christopher Howse

61 Surreal Spaces: the Life and Art of Leonora Carrington, by Joanna Moorhead

Lucy Lethbridge

63 The Three Graces, by Amanda Craig Mary Killen

Arts

66 Hello, Bookstore

Harry Mount

67 Theatre: Crazy for You William Cook

Pursuits

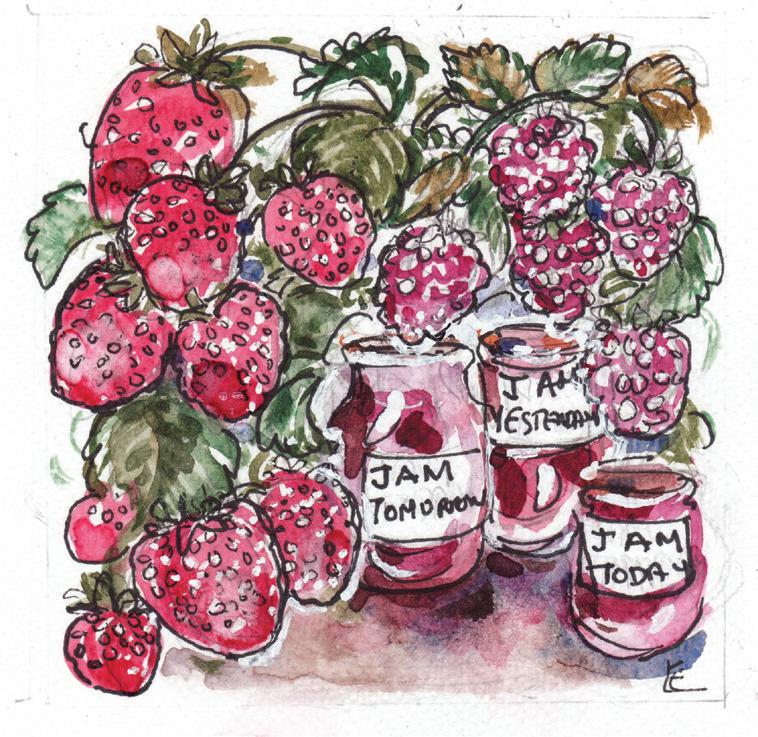

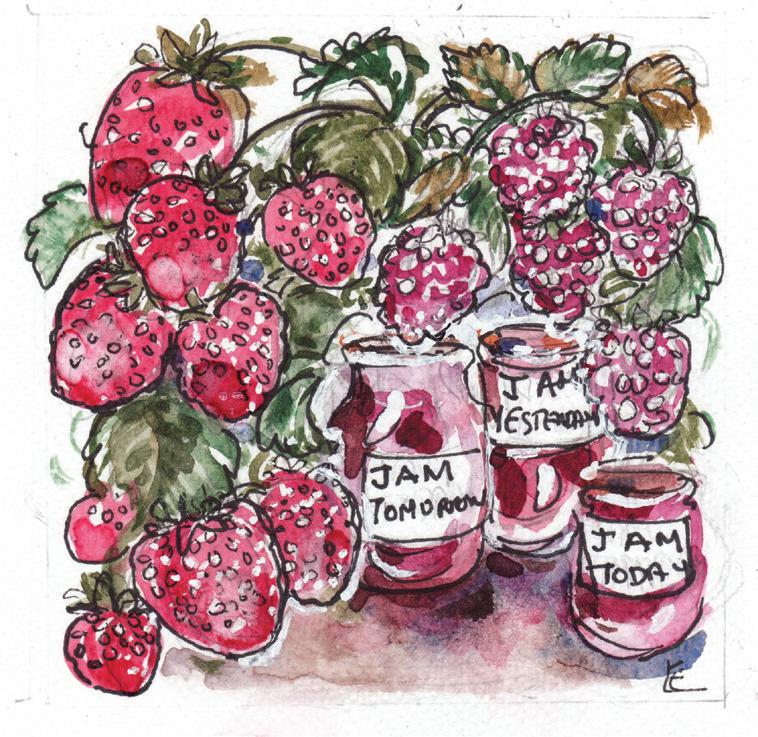

73 Gardening David Wheeler

73 Kitchen Garden Simon Courtauld

74 Cookery Elisabeth Luard

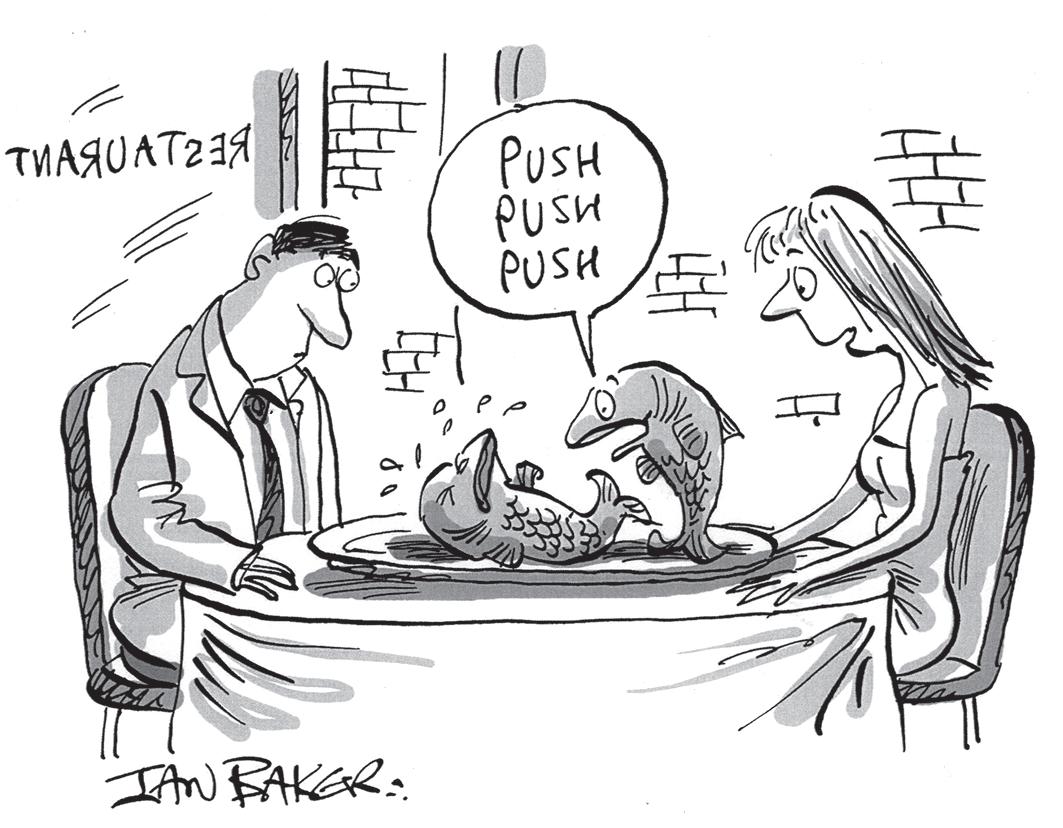

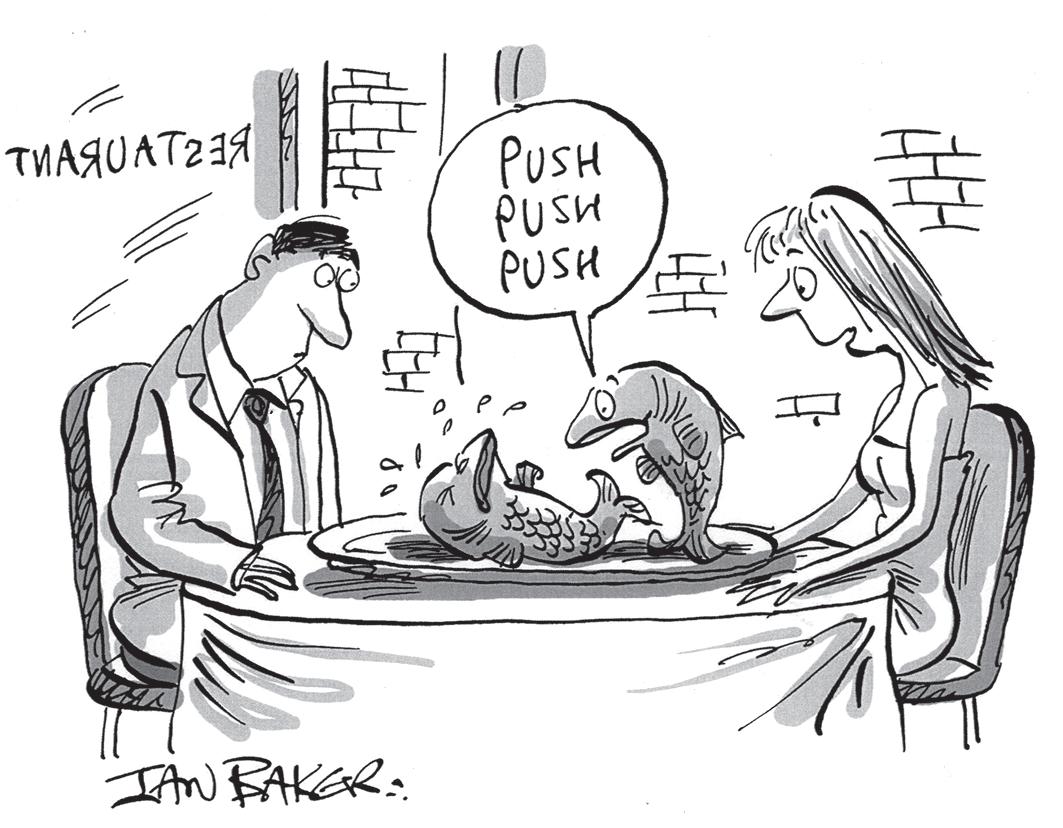

74 Restaurants James Pembroke

75 Drink Bill Knott

76 Sport Jim White

76 Motoring Alan Judd

78 Digital Life Matthew Webster

78 Money Matters

Margaret Dibben

81 Bird of the Month: shag

John McEwen Travel

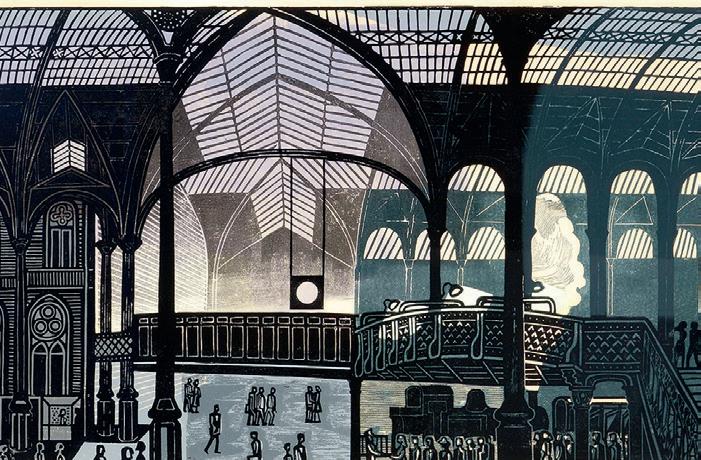

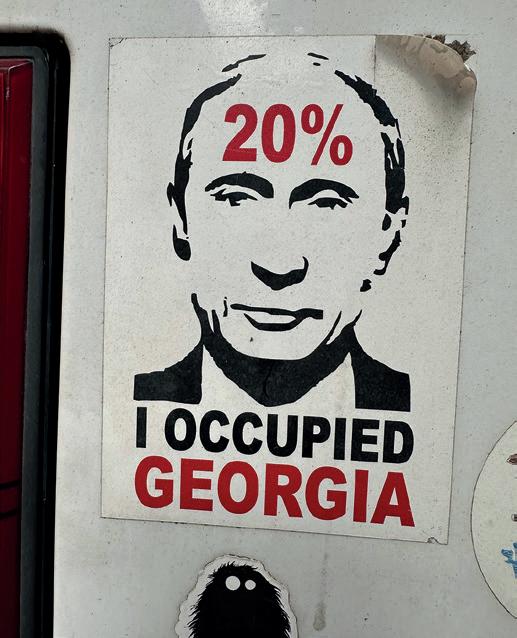

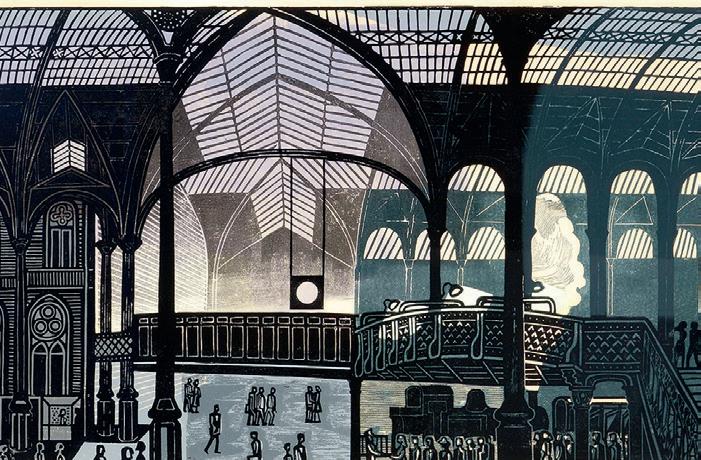

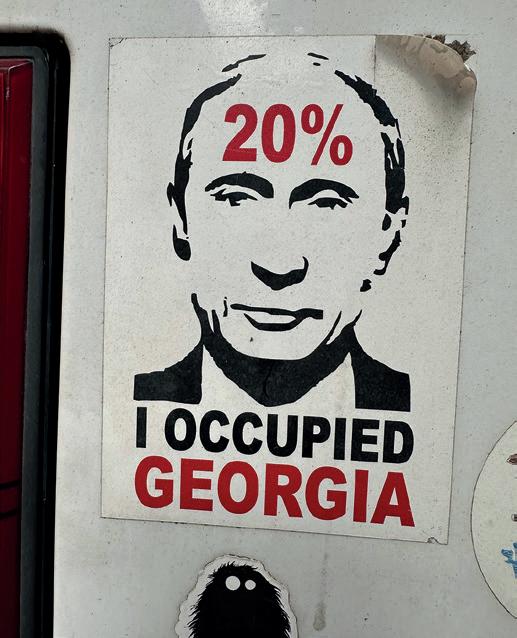

82 Georgia, Jason and the Golden Fleece

Justin Marozzi

82 Overlooked Britain: Roman loos Lucinda Lambton

86 On the Road: Jools Holland

Louise Flind

Regulars

Editor Harry Mount

Sub-editor Penny Phillips

Art editor Jonathan Anstee

67 Radio Valerie Grove

68 Television Frances Wilson

69 Music Richard Osborne

70 Golden Oldies

Rachel Johnson

71 Exhibitions

Huon Mallalieu

Oldie subscriptions

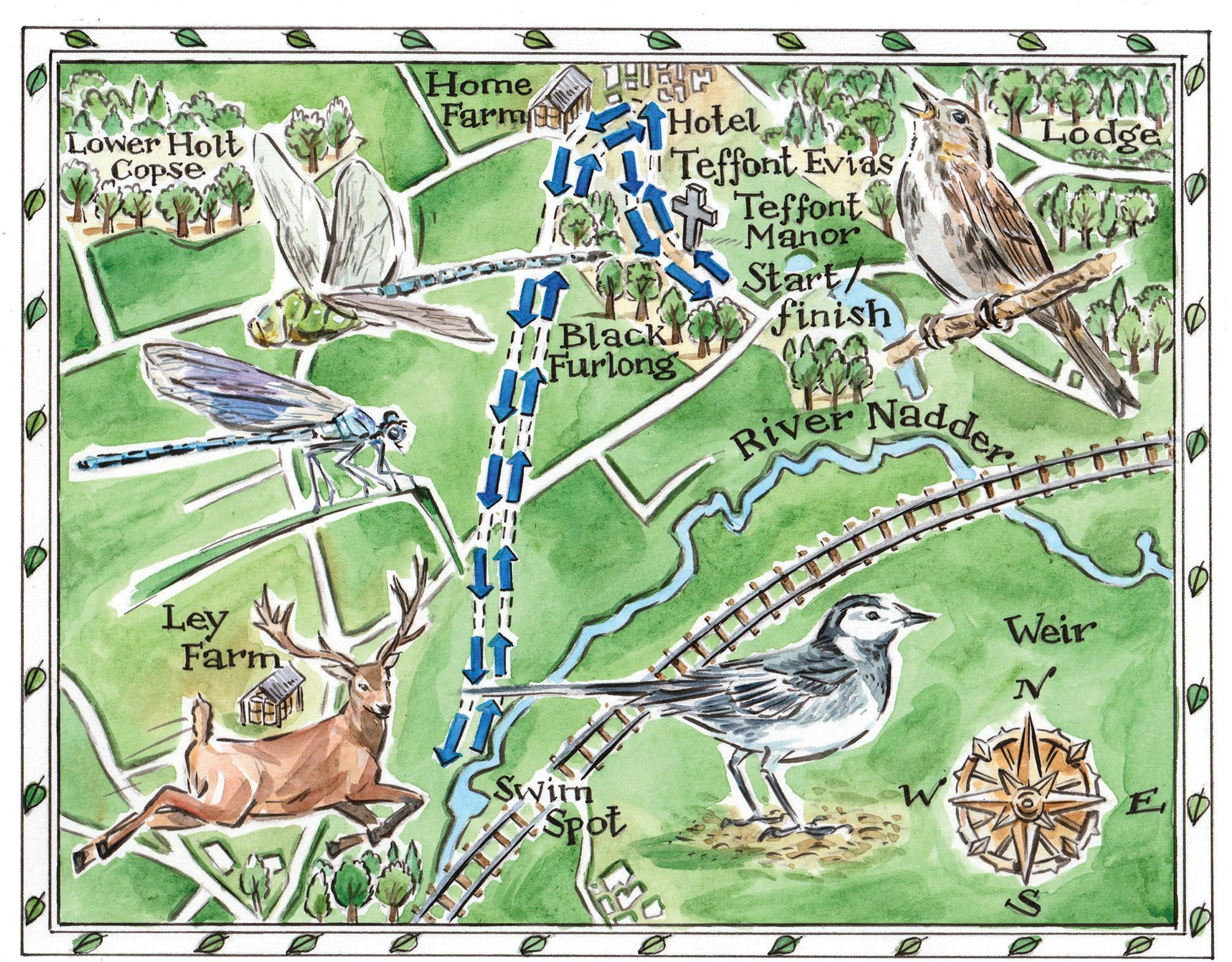

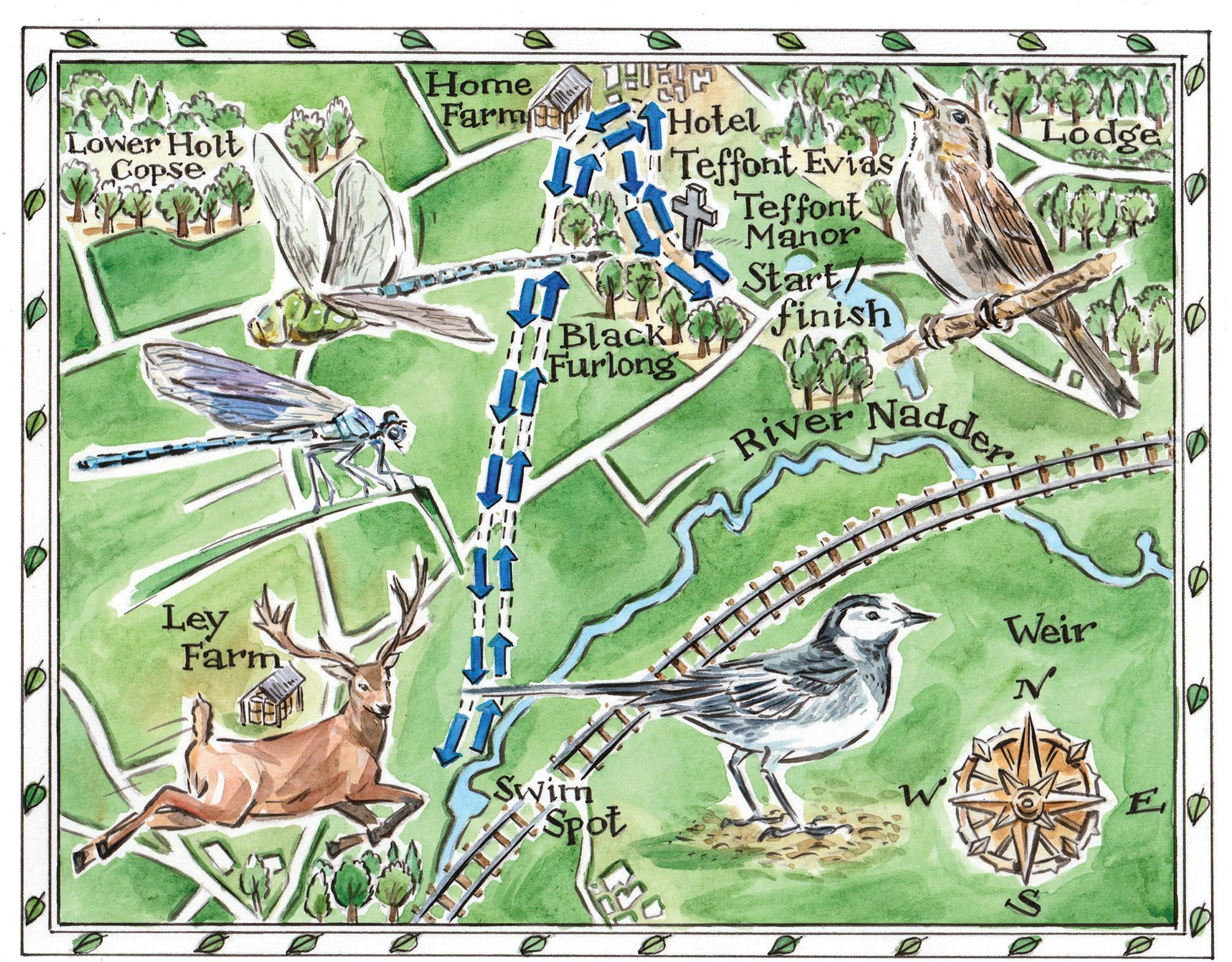

87 Taking a Walk: Wiltshire's happy valley Patrick Barkham

Oldie

Advertising

Moray House, 23/31 Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk

Supplements

editor Jane Mays

Editorial assistant Amelia Milne

Publisher James Pembroke

Patron saints Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

At large Richard Beatty

Our Old Master David Kowitz

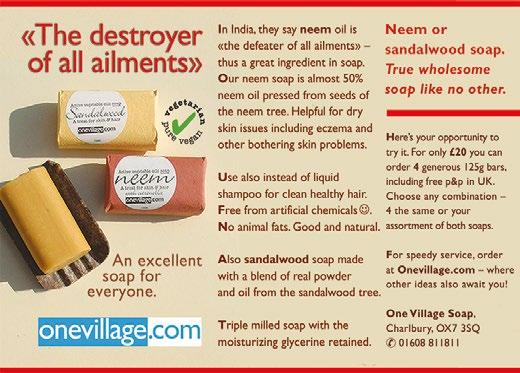

To order a print subscription, go to www. subscription.co.uk/oldie/offers, or email theoldie@subscription.co.uk, or call 01858 438791, or write to The Oldie, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF. Print subscription rates for 12 issues: UK £49.50; Europe/Eire £58; USA/Canada £70; rest of world £69.

To buy a digital subscription for £29.99 or single issue for £2.99, go to the App Store on your tablet/mobile and search for ‘The Oldie’.

For display, contact : Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Jasper Gibbons on 020 3859 7096

For classified: Monty Martin-Zakheim on 020 3859 7093

News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

The Oldie August 2023 3

14 Charles Hawtrey, the genius of Carry On Roger Lewis 16 Joy of not driving Jennifer Florance 17 Thatcher’s housing tip Anne Robinson 18 Death of glamour Charlotte Metcalf 20 Who killed Sir Harry Oakes? Charles Owen 21 Elizabeth I’s love nest Quentin Letts 23 Hell is boring people Oliver Pritchett 26 My fairy godmother Harry Mount 29 Save Liverpool Street Griff Rhys Jones 32 Heroic Harriet Crawley David Ambrose 34 A cruise-ship entertainer’s life for me David Pybus 35 Happy has-been Julian Neal

5 The Old Un’s Notes 9 Gyles Brandreth’s Diary 11 Grumpy Oldie Man Matthew Norman 12 Olden Life Graham Sharpe 12 Modern Life Richard Godwin 37 Oldie Man of Letters A N Wilson 38 History David Horspool 40 Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson 41 Country Mouse Giles Wood 42 Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny 44 Mary Killen’s Beauty Tips 45 Small World Jem Clarke 47 School Days Sophia Waugh 47 Quite Interesting Things about ... cigarettes John Lloyd 48 God Sister Teresa 48 Memorial Service: Hilary Alexander James Hughes-Onslow 49 The Doctor’s Surgery Dr Theodore Dalrymple 50 Readers’ Letters 52 I Once Met… John Lewis John de Bruyne 52 Memory Lane Pamela Howarth 65 Commonplace Corner 65 Rant: packaging Carolyn Whitehead 89 Crossword 91 Bridge Andrew Robson 91 Competition Tessa Castro 98 Ask Virginia Ironside

cover Landmark Media /Alamy

Front

ABC circulation figure July-December 2021: 48,249 Subs Emailqueries? co.uksubscription.theoldie@ or 01858phone 438791

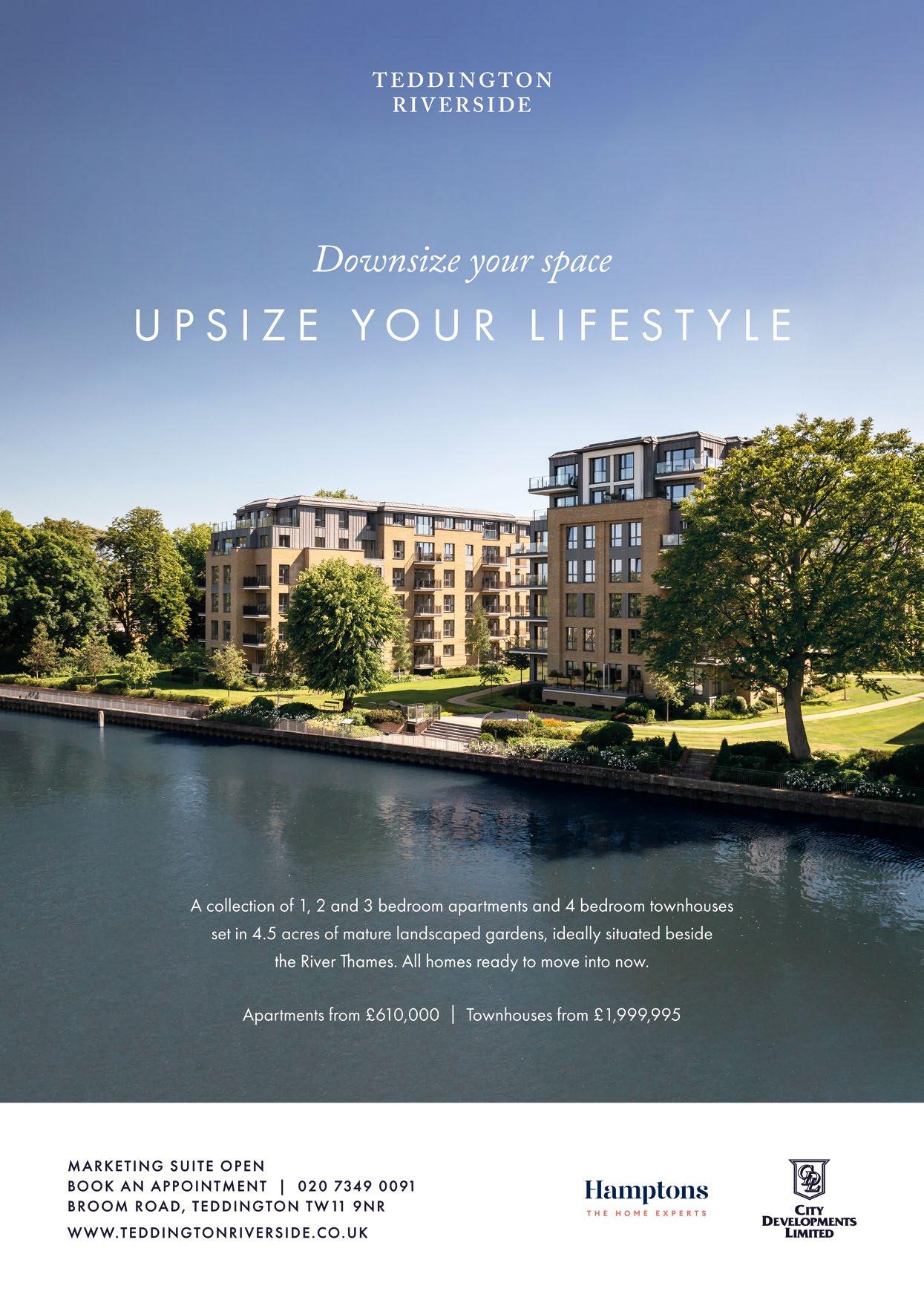

Annie met Maggie page 17 Lost and found: Snodhill Castle page 21 End of the line for Liverpool St? page 29 Save when you subscribe – and get two free books

page 31 Reader Offers

When

See

literary lunch

Reader trip to Northern Spain

p35

p79

The Old Un’s Notes

‘Given sufficient notice, one can always be spontaneous.’

If this saying reminds you of Oscar Wilde, it’s entirely appropriate. With this aphorism, Robert Eddison has won the fourth Wilde Wit Competition run by the Oscar Wilde Society, in partnership with The Oldie and The Chap. Oldie columnist Gyles Brandreth is the Society’s honorary president.

Eddison’s quote topped the list of more than 300 entries sent to the Society. Contestants vied with each other to produce Wildean aphorisms, both amusing and profound.

The shortlist was chosen by the Oscar Wilde Society Committee and guest judge Darcy Alexander Corstorphine, who won the first three years. He was invited NOT to enter this year, so as to give others a better chance.

Second place went to AJ West for this quip: ‘If it weren’t for nihilism, I’d have nothing to live for.’

Third place went to Simon Scarratt for: “A man who always tells the truth can never be trusted.”

Congratulations to our witty winners, who — like James Whistler — spoke so cleverly that Oscar himself might have wished he had said it.

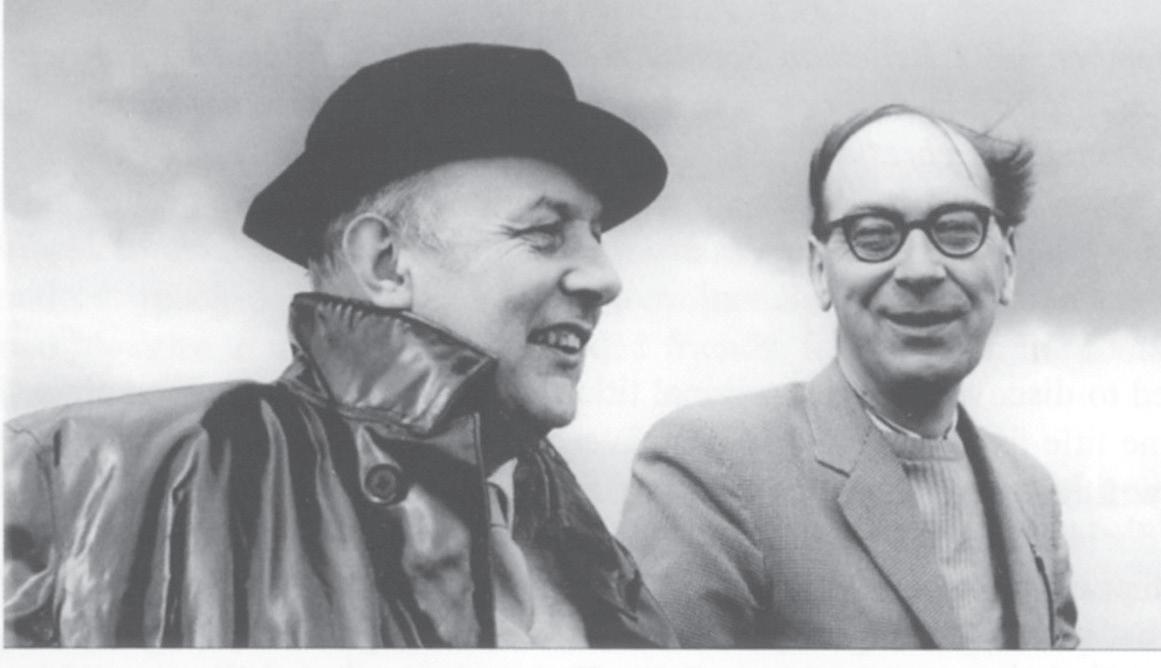

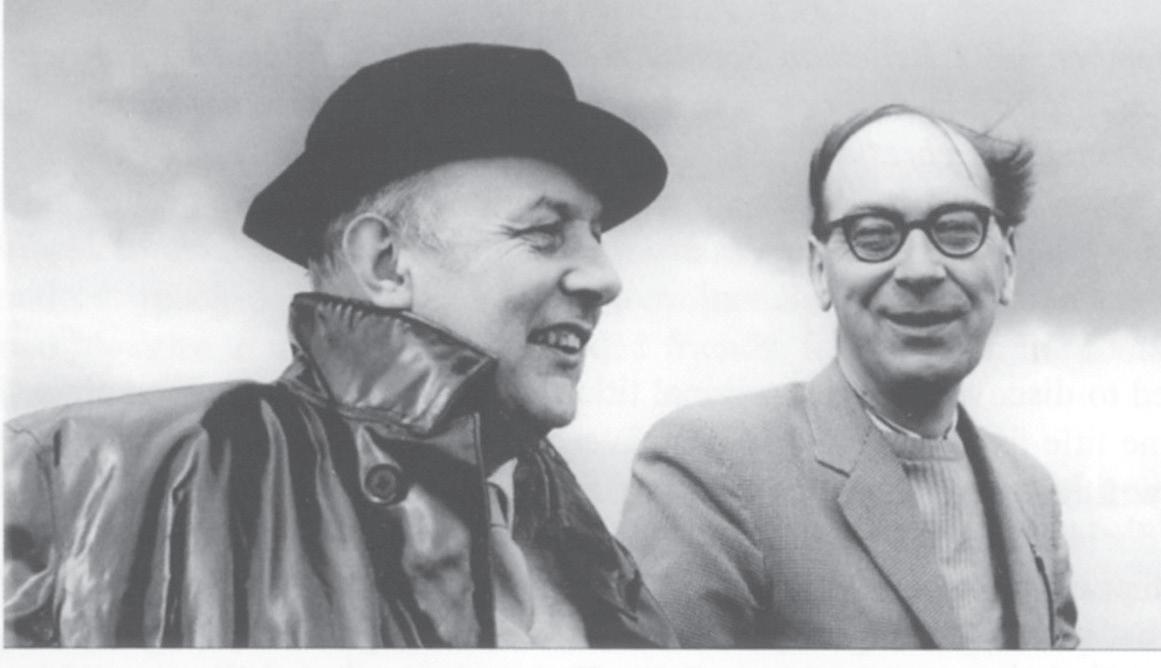

John Betjeman and Philip Larkin were fine poets, great friends – and

surprising Lotharios. So writes Philip Pullen in the new issue of The Betjemanian, the journal of the John Betjeman Society.

Pullen quotes Betjeman’s wife, Penelope, berating the poet for his affair with Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, the Duke of Devonshire’s sister.

Among this month’s contributors

Charlotte Metcalf (p18) is an awardwinning film-maker and freelance writer. She is the editor of Great British Brands and co-presents the Break Out Culture podcast.

Griff Rhys Jones (p29) starred in Not the Nine O’Clock News and Alas Smith and Jones with Mel Smith. He co-founded Talkback, the TV production company, and presented A Pembrokeshire Farm

David Pybus (p34) has lectured aboard cruise ships for 25 years, on everything from Dragons’ Den to pirates. He is a perfume expert, who has recreated the scent found on the Titanic.

Justin Marozzi (p82) is a travel-writer. His books include Islamic Empires: 15 Cities That Define a Civilisation, Tamerlane and The Man who Invented History – Travels with Herodotus

Peas in a pod: John Betjeman and Philip Larkin filming in Hull, 1964

‘I will take no halfmeasures,’ Penelope Betjeman writes. ‘I am fed up with your divided life and completely false set of values… I’m damned if I am going on with you in this perpetual dichotomy with insomnia, hysterical nerves, fear of losing your reputation etc etc.’

As Pullen writes, this could so easily have been written by Monica Jones, Philip Larkin’s much betrayed girlfriend, to Larkin.

Pullen also quotes the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster’s line that ‘Betjeman was the only person he knew who managed to be married, have a mistress and live the life of a bachelor all at once.’

In his fine article, Pullen also notes the fees Larkin and Betjeman got for their charming BBC programme in 1964, where the two poets tour Hull. Larkin got £125. Betjeman got £200. As Pullen says, Larkin ‘would not have been amused’.

The Oldie August 2023 5

BBC

Important stories you may have missed

Decision on 200 homes plan in Harrogate is delayed

Northern Echo

Shopping trolley dumped in park

Bolton News

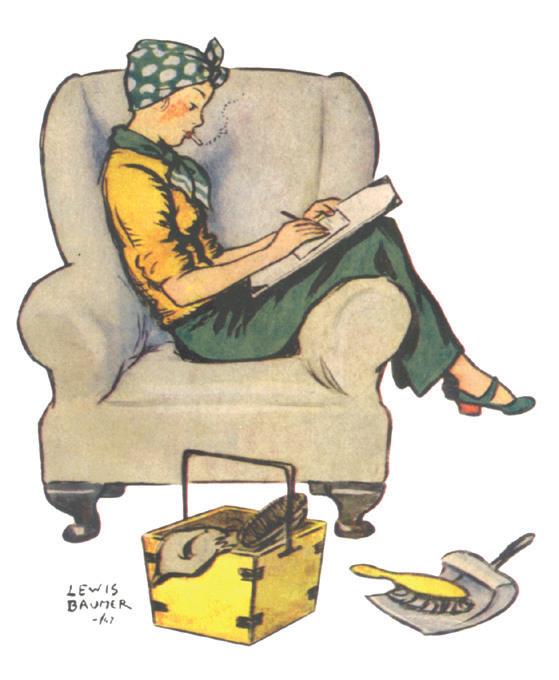

Oldie readers will remember AP Herbert (1890-1971), the MP and comic writer Less well-known is his 1928 creation, The Voluble Topsy. She was a sort of Bridget Jones of the 1920s meets Nancy Mitford – and she now returns in the reissued The Voluble Topsy (1928-1947) (Handheld Press).

An It Girl before It Girls were invented, she is a deb and a flapper.

And she has a fine line in breathless patter, delivered in stream-of-consciousness letters, crammed with spelling mistakes, to her friend Trix:

‘Nowadays, the papers only have to say, “You must flock to Thingummy or Whatname,” and we all flock; my dear, it’s too gregarious and unSaxon, and really nobody’s happy this year unless they’re standing in a quue.’

Three cheers for the return of Topsy!

Bench fear for OAPs

Millport Weekly News

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The September issue is on sale on 26th August 2023.

GET THE OLDIE APP

Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

OLDIE BOOKS

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

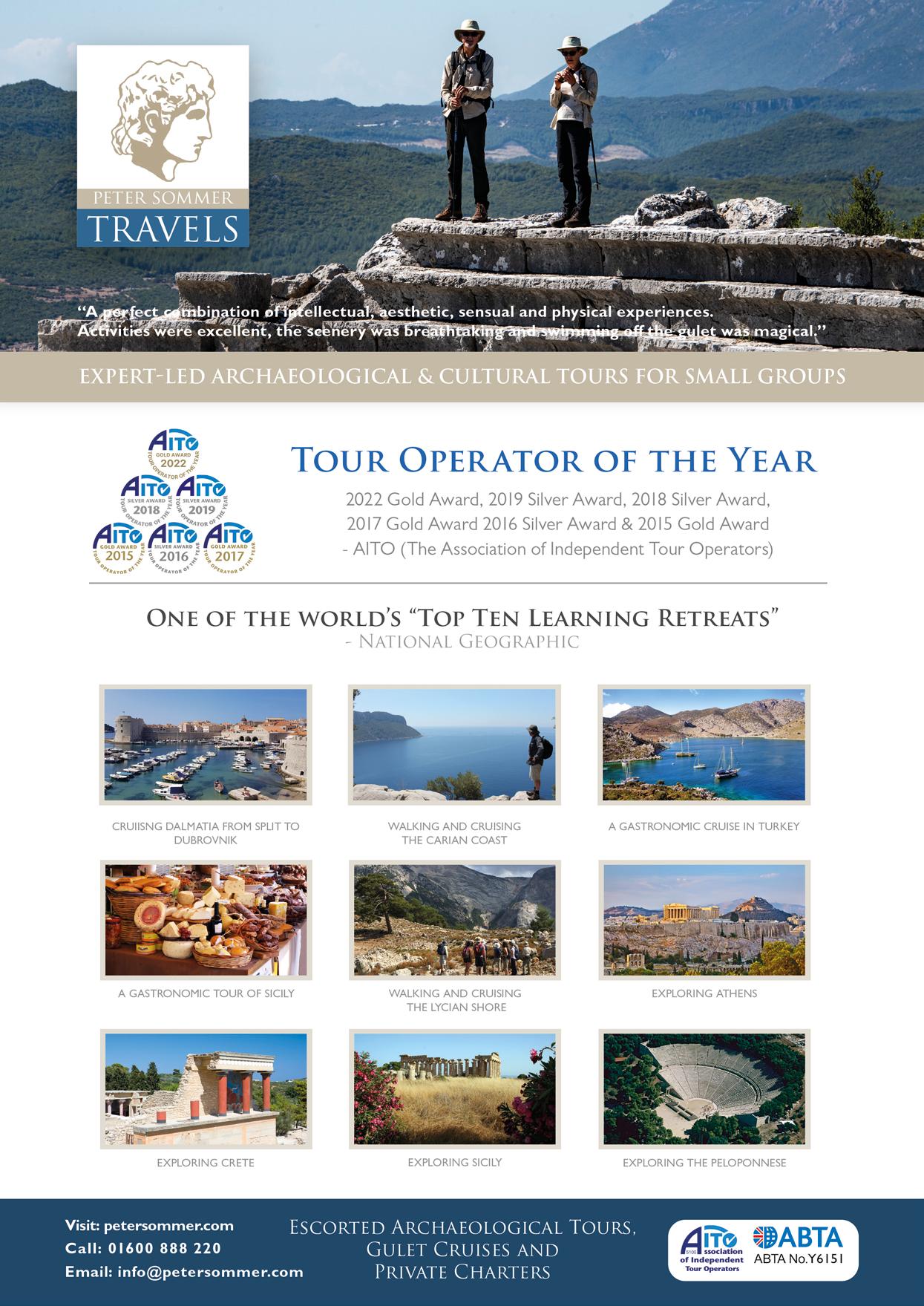

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

Roger McGough, the poet who put the beat into Merseyside, has written a musical, Money-Go-Round And he is taking the cautionary tale about our lust for gold, loosely based on The Wind in the Willows, to the Edinburgh Fringe.

McGough, 85, our Oldie People’s Poet of the Year in 2021, has long been a fan of the Kenneth Grahame classic.

‘It was a favourite book as a child, and Toad of Toad Hall was the first play I was in at school,’ he says. ‘Apparently my rendition of Mr Badger is

still considered unbeatable,’ he says.

In 1985, he was asked to write the lyrics for an American version of the book, which had a very fleeting brush with Broadway. Undefeated, he was inspired to write a children’s book, Money-Go-Round, in which a coin is passed around each of the famous characters in the novel until it returns to its original owner.

‘I wanted children to regard friendship as more important than money,’ says McGough.

Then the penny dropped. Money-Go-Round could be a musical, too.

McGough, who first went to the Fringe in the early 1960s as part of The Scaffold, is also

founding member of South London band LiTTLe

MACHiNe [sic], a trio who take poetry – from medieval to Metaphysicals, Shakespeare to Carol Ann Duffy – and set it to music.

For the musical, bandmate Steve Halliwell, former lead of 70s ‘bad ass rock band’ King Swamp, wrote the score.

A cast of six (a whole orchestra by Fringe standards) rehearsed in McGough’s home patch in Barnes, agitating against the ‘destructive pursuit of wealth’ while playing Mr Toad, Mole and Ratty.

Here’s hoping the show goes with a bang – or a ‘Poop-poop!’, as Toad might put it.

6 The Oldie August 2023 KATHRYN LAMB / NEIL SPENCE

Lost Mitford: Voluble Topsy

People’s Poet: Roger McGough

‘Talk to me while I ignore you’

Congratulations to Lore Segal – the American writer who, at 95, is still publishing witty short stories.

Her latest collection, Ladies’ Lunch, is full of wry insights into oldie life in New York. Segal quotes the anonymous one-liner, ‘How pleasant the sight of a cheerful old person.’

And she is good at insights into the declining returns of old age: ‘Those were the days when I used to know eighty per cent of the people at a party. Now I know two people.’

Segal, born into a middleclass Jewish family in Vienna in 1928, escaped the Nazis to

Britain on one of the first Kindertransport missions. After graduating from Bedford College for Women (remembered fondly by Pamela Howarth on page 52) in London in 1948, she moved to New York. Her first novel, Other People’s Houses, came out in 1964 – and she has been writing ever since, for nearly 60 years.

Long may she continue to chronicle the lives of oldie New Yorkers.

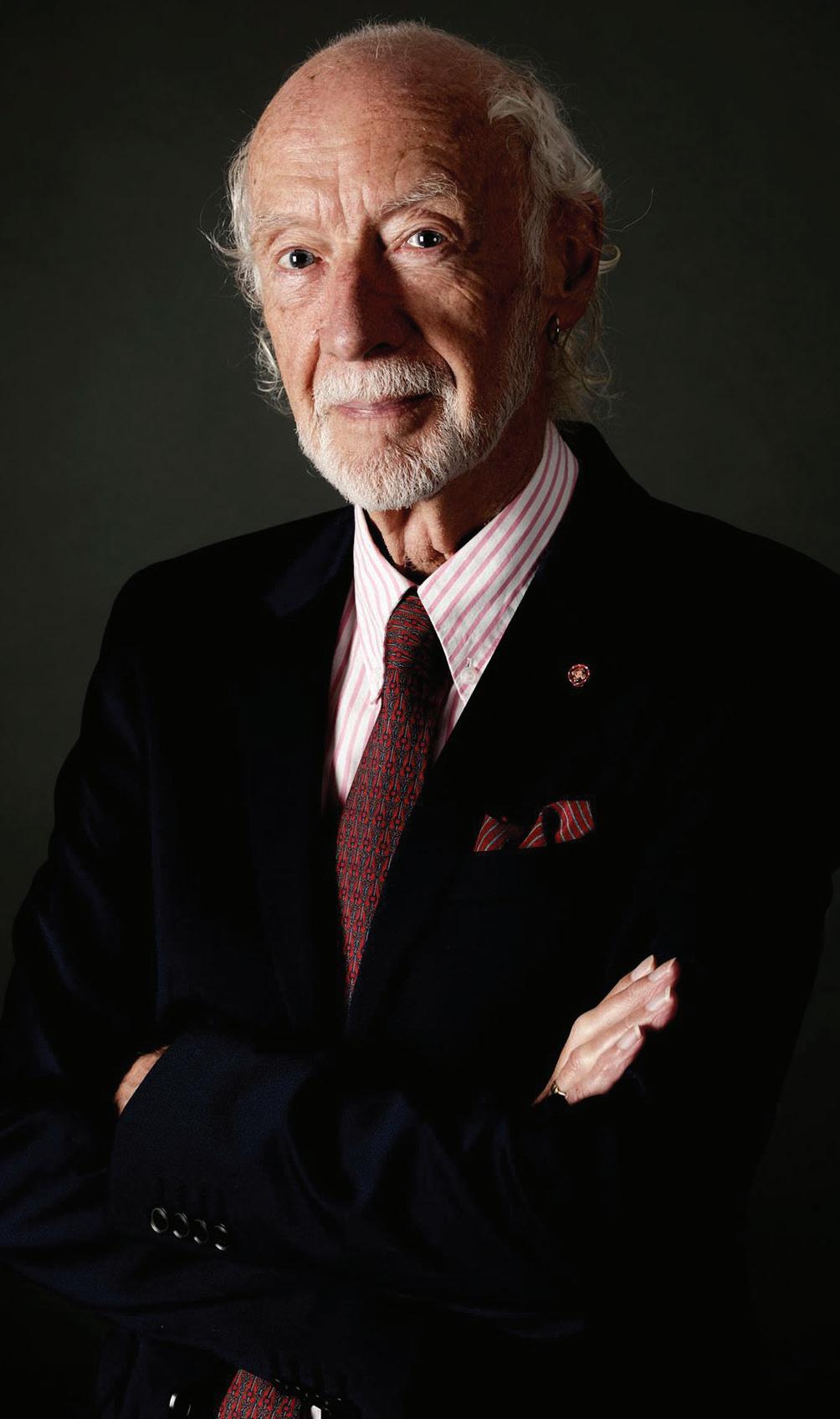

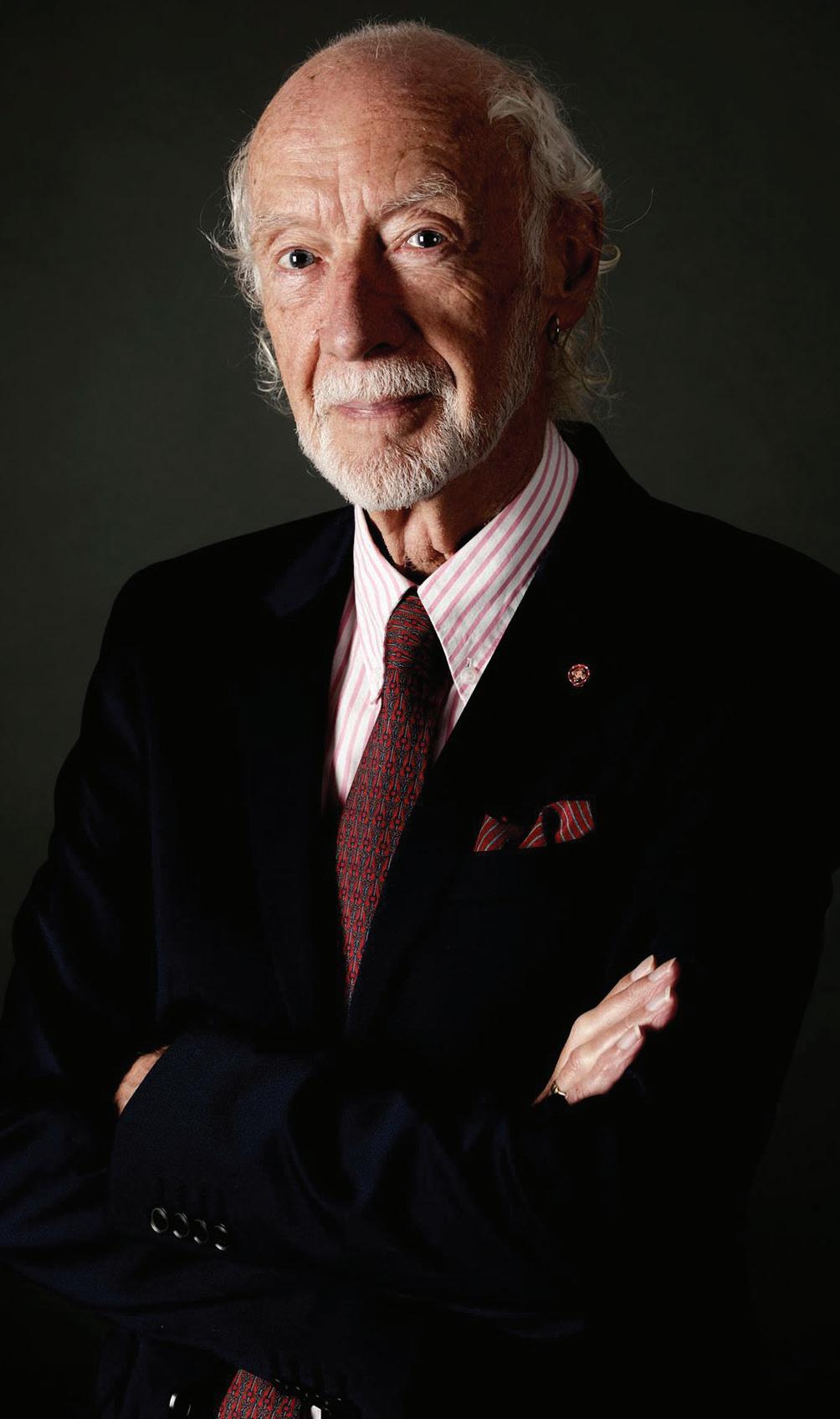

Many congratulations to Barry Fantoni, the cartoonist who joined Private Eye in 1963, the same year as The Oldie’s founder, Richard

Ingrams, became editor of the Eye.

At 83, Fantoni has written and drawn a charming children’s book, Pep, the story of a Barcelona FC-loving cat, inspired by Pep Guardiola, the treble-winning Manchester

‘This one’s good if you like complaining about the heat ... and this is excellent for complaining about the food ... of if you prefer complaining about ...’

City manager and former Barcelona hero.

Among Fantoni’s creations at Private Eye were the dreadful poet E J Thribb. He also invented Neasden FC, the appalling football team, currently languishing in the North Circular Relegation League. Neasden are run by their permanent manager, ‘tight-lipped, ashen-faced supremo Ron Knee (59)’, and supported by their two loyal fans, Sid and Doris Bonkers.

Surely it’s time for Barry’s two great inspirations, Neasden FC and Barcelona FC to take each other on at Barcelona’s Nou Camp Stadium?

‘Sandraremember those naturists we met in Lesbos in ‘97?’

The Oldie August 2023 7

Pep, the feline footballer

‘All parents ght, son’

Killers I have known – and liked

‘Never commit murder,’ said Oscar Wilde. ‘A gentleman should never do anything he cannot talk about at dinner.’

To date, there has been no blood on my hands, but that may change. I am busy devising the perfect murder. I haven’t had so much fun in years.

It started as a cure for insomnia. When I go to bed, I nod off right away. At 5am, I wake up and can’t get back to sleep. That used to be a problem. Not any more. I now kill the time between when I wake and when the alarm goes off at 7am on an imaginary killing spree.

I don’t have a particular victim in mind. My focus is on the murder itself. It has to be quick, clean and undetectable.

As regular readers may remember, not long before she died, P D James, one of my favourite crime writers, told me the simplest way to murder someone is to take them for a quiet walk along Beachy Head. At 530 feet high, the East Sussex sea cliff provides the perfect setting for an unexpected killing.

When you are sure no one is looking, simply, suddenly and sharply, push your victim over the edge.

Fifty years ago, I published my first book, Created in Captivity. It was about prison reform and about how the creative arts – painting, poetry, drama – can help prisoners on the road to rehabilitation.

Researching the book, I met several murderers and built up a small collection of their paintings and sculptures. My favourite was a still life by Donald Hume (1919-78), a double murderer who ended his days in Broadmoor.

In 1949, Hume, a petty criminal with a pilot’s licence, murdered a fellow petty criminal who, according to Hume, had upset him by kicking his beloved dog, Tony. In his London flat on the Finchley Road, Hume stabbed his friend to death with a wartime souvenir, a Nazi SS dagger, and dismembered him with a lino-cutter and a hacksaw. Hiding the

torso in the coal cupboard (where his wife wouldn’t find it), he parcelled up the head and legs and drove with them to Elstree Airfield where he boarded a light aircraft and flew towards Southend and the English channel. He successfully dropped the body parts and the murder weapon into the sea.

The next day, managing to avoid both his wife and the cleaning lady, he asked a decorator to paint over the bloodstains on the wall in his flat and then, with the decorator’s help, carried another parcel – this one containing his victim’s torso – downstairs and into his car.

This time, he misjudged the route of his flight and instead of completing the perfect murder by dropping the evidence into the Channel, he dropped his package onto the Essex marshes.

The torso was found and Hume was charged with murder. But the jury failed to reach a verdict. At his second trial, he pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of being an accessory after the fact and was sentenced to 12 years. On his release, he killed another man during a botched bank robbery in Switzerland. This time, he was using a gun. That’s not my style. Guns are noisy and unreliable. Daggers

and hacksaws are messy and involve a lot of risky clearing up. I’m with P D James and the short, sharp shove – and with the great Agatha Christie who, given the choice, always opted for poison.

The only murderer I have known that I would properly call a friend was another Hulme, but with a different spelling.

In 1954, when she was just 15, Juliet Marion Hulme and her best friend, Pauline Parker, stuffed a half-brick into a lisle stocking and lured Pauline’s mother into a lonely park where, together, the teenage girls bludgeoned the mother to death.

It was a grim and grisly story, turned into a 1994 film by Peter Jackson called Heavenly Creatures, in which Kate Winslet played the part of my friend.

The ‘gymslip murderers’, as they became known, escaped the gallows because of their youth and Juliet Hulme tried to escape her past by changing her name. By the time I met her, she had become Anne Perry, a bestselling author of historical murder mysteries.

For a while, we were quite close. We went on a book promotion tour together around France and, at the start and end of the day, often shared a meal together. Though I tried, because she seemed such a nice person, I could never get it out of my mind that, once upon a time, she had committed a murder.

Ridiculous as it sounds, whenever she brought two cups of coffee to our table I always made sure I drank from hers and not mine and each time she picked up a steak knife, I flinched.

When she came to stay with us in London, my wife and I locked our bedroom door overnight – as quietly as we could.

Anne Perry died on 11 April this year, aged 84. Of natural causes . . . I think.

Gyles is appearing at the Edinburgh Fringe in August

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

Some people count sheep – when I can’t sleep, I plan the perfect murder

The Oldie August 2023 9

My friend, the murderer: Anne Perry

‘Mum and Dad, can I borrow the wheel tonight?’

10 The Oldie August 2023

Warning! Moronic road signs ahead

Admirers of the highest classical culture will fondly recall Clash of the Titans, the 1981 filmic meisterwork in which Laurence Olivier’s Zeus and his fellow Olympians look imperiously down on humanity, and use their limitless powers to manipulate the affairs of mankind.

The identity of this modern deity may never become known beyond the screen-filled room in which they toy with mortal events.

But somewhere, in some municipal, modern Olympus elegantly styled after the Lubyanka, there is a Zeus du jour with a penchant for torturing motorists with palpably false traffic information.

There could in fact be dozens of them dotted all over the land. If only for narrative simplicity, however, I prefer to believe in a lone deity responsible for every fraudulent illuminated road sign that plagues a motorway or A road.

What drives this mischievous creature is less a matter for us than for a phalanx of world-ranked psychoanalysts, split evenly into three teams and working in eight-hour watches around the clock.

Whatever the motivation (psychosis; boredom; the weird compulsion to punish an inferior species), these pixillated messages are increasingly divorced from reality.

Long before a recent nightmare on the M4, suspicions had been raised by such old favourites as: ’50 mph: Congestion Ahead.’ You must have experienced yourself the delight of spending an hour travelling at the marginally slower speed of 0.7 mph – only to discover, the moment you reach the end of the queue to find the road ahead clear, that the queue had been generated neither by weight of traffic nor an accident.

The sole reason for the congestion was that a sign warning of congestion had caused motorists to slow to a crawl. One appreciates a cute self-fulfilling prophecy, of course, not to mention the irony

inherent in this motoring version of iatrogenesis (a medical disorder is caused solely by medical treatment).

Recently, however, the deity has taken to egregious taunting with warnings styled not as statements of fact, but as vague claims for which the god of motorway signage has plausible deniability.

‘50 mph,’ read one lately encountered on the M3. ‘Report of lane closure ahead.’

In this context, ‘report’ is the most vexing euphemism to afflict the language since the Radio Times took to describing the output of sitcom writer Roy Clarke (Last of the Summer Wine; that excrescence starring Patricia Routledge as a pantomime snob) as ‘gentle comedy’ – the word ‘gentle’ standing proxy here for the word ‘no’.

What ‘report of lane closure ahead’ appears to mean is: ‘No lane closure ahead, but I’m bored witless stuck here doing nothing, and I want you to know how I feel.’

We know that ‘report’ is a lie for two reasons. First, the presence of a camera every three inches on motorways means that no ‘report’ would be required by anyone with access to: a) screens showing live footage; and b) the miracle of eyesight.

Secondly, not long ago on the M4, I saw this: ‘40 mph: report of wild animals on road ahead.’

The commitment to fairness dictates an admission. Technically, it is possible that the westbound M4 (or, come to that, its easterly twin) will be invaded by rampaging hordes of wild animals. A

truck close to concluding its long trek from the Serengeti might be involved in the pile-up that causes its rear door to spring open, releasing dozens of big cats on to the hard shoulder.

More likely perhaps is a breakout from nearby Windsor Safari Park. Fans of the Planet of the Apes franchise will be familiar with the uprising led by Caesar, the pioneering talking chimp whose craving for social justice would eventually lead to Charlton Heston having that chilling epiphany on a New York beach.

One day, then, it is plausible that the inmate of a zoo – probably one of the higher primates, though conceivably the Spartacus of the hippo enclosure – will spearhead the mass escape and beastly invasion of the M4 that would justify such a message.

The recent afternoon on which the sign was observable, on the picturesque outskirts of Slough, was not that day.

Once again, anyone charged with observing traffic video would have struggled not to notice a herd of wildebeest sweeping majestically along the middle lane. And, even if so, it’s a fairly safe bet that one of the countless over-sharers of Twitter would have mentioned the appearance, on the bonnet of their Lexus, of a giraffe, a pair of ostentatiously mating mountain gorillas and a freshwater crocodile.

It is of course utterly futile to rail against this addition to the myriad horrors of attempting to travel through this miserable country.

Those whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad, as, I think, Sophocles, put it.

But it’s hard to avoid the feeling that, in the field of deity-generated, roadrelated horror, Oedipus got off lightly with nothing worse than killing his father at the crossroads and the maternal coupling which ensued from that.

Grumpy Oldie Man

The new motorway hazard – phantom traffic jams and mythical beasts matthew norman

The Oldie August 2023 11

Technically, it is possible the M4 will be invaded by hordes of wild animals

what was a boardman?

The boardman was the lowest-paid, most important member of staff in the betting shops that appeared legally on the nation’s high streets from Monday 1st May 1961, then known as licensed betting offices.

He – almost always ‘he’ – was the only member of staff to liaise directly with the clientele, as the other workers were clustered behind a counter, protected by a bandit screen.

The boardman stood in the main area of the shop, liaising with customers. He displayed on his chalkboard – later replaced by white plastic ones and felt-tip pens – the latest betting odds and race results.

Horseracing and greyhound racing accounted for almost the entire turnover of a betting shop. The biggest betting events were the Grand National and the Derby.

what is white people food?

White people food is a piece of white bread with a sorry slice of ham and a sad tomato. It’s a hard-boiled egg and a side of undressed salad. It’s hummus and carrots. It’s a cheese sandwich. It’s a ‘lunch of suffering’.

And it’s a source of fascination and horror for Chinese youths, who claim to be astonished at the bland, spiceless al desko meals we Westerners routinely ingest.

The term originated on the socialmedia site Xiaohongshu, when a Chinese student uploaded a video of a woman on a Swiss train working her way through a head of lettuce and some ham. ‘I saw the pinnacle of white people cuisine today…’ the student told her followers.

This prompted a flurry of responses from other users, describing the joyless meals they’d seen on their travels, typically meagre vegetables and processed meats eaten cold out of lunchboxes.

A long-time resident of Germany

Race commentaries were transmitted over an in-shop Tannoy system – TV coverage was banned until the mid-’80s.

An ambitious boardman’s promotion would result in his becoming a ‘settler’. This meant working behind the counter where, after training, he – again a male role – would calculate the pay-outs customers’ winning bets had won.

When live TV coverage of races was introduced, boardmen became first an endangered species and then an extinct one.

Machines were introduced to settle bets automatically, allowing the person overseeing the process to concentrate on other matters, often becoming shop manager, which enabled companies to cut staffing costs.

Anyone looking for a realistic impression of a ’70s/early-’80s betting shop should watch the BBC series Big Deal, starring Ray Brooks as Robbie Box, which captures the milieu perfectly.

I began frequenting betting shops in

the late ’60s, aged 18, working in one aged 21 as a boardman.

I took pride in displaying runners’ details for the races on the in-shop board, in probable betting order, listing odds against the name of each horse, highlighting the favourite in a different colour.

Once the race was ‘off’, I’d follow the spoken commentary, writing against each horse’s name its current position in the race. I graduated from my role, learning the position of ‘settler’ via evening classes.

My betting-shop career ended suddenly. Filling in as a counter clerk, I handed one punter £100 too much.

I felt the manager had caused this problem by writing the amount due in longhand, letting the tail of a y extend into the pay-out section on the betting slip, where the total appeared in numbers – turning 50 quid into 150. The till was £100 short.

You bet I was sacked!

Graham Sharpe

reported that a colleague of theirs had the same lunch every single day: oatmeal mixed with low-fat yoghurt, plus half an apple and a carrot. ‘If such a meal is to extend life, what is the meaning of life?’

Many Chinese youths are now, ironically or otherwise, experimenting with ‘white people lunches’ of their own. Others theorise about what led the West to such pitiful meals.

Perhaps we have relegated food to subsistence as opposed to pleasure? Perhaps it’s something to do with Christian guilt? Perhaps we don’t know any better? It’s a mystery.

Not since a Chinese businessman recoiled from the ‘putrefied discharge of a cow’s udder’ (ie blue cheese) served to him at a Michelin-starred restaurant have our culinary habits been served up to us with such a healthy dollop of defamiliarisation.

Now, I could discourse for a long time on the simple pleasures of a good ham sandwich; or a plate of crudités with mustardy vinaigrette; or a simple, perfect caprese salad. Indeed, it wasn’t so long ago that we British mocked the

French for their fancy sauces as it was generally considered that our produce was so superior as not to require any embellishments.

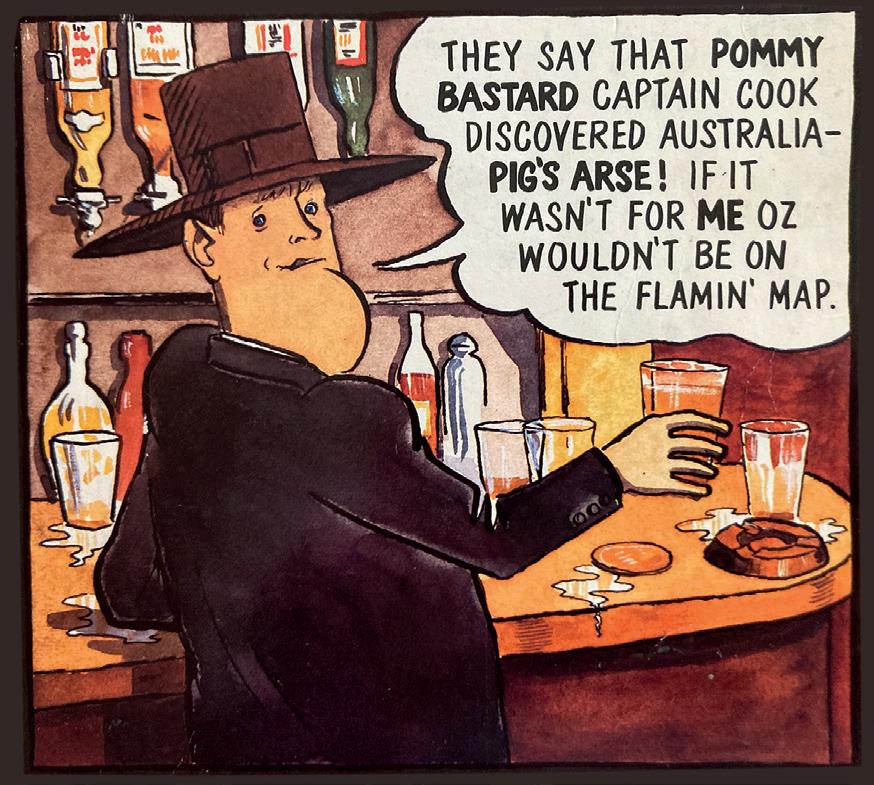

These days, though, it’s more commonly British food that’s scorned for its blandness. So perhaps we should breathe a sigh of relief, for here we are, lumped in with the Italians, Australians and Swedes, as if we were all the same. Besides, how many of us would appreciate the finer differences between, say, Jiangsu and Szechuan cuisine? Not many, I fancy.

And here’s another little crunch of irony to savour. It’s common for us Westerners to characterise Chinese people as joyless workaholics. But in China, two-hour lunch breaks remain standard; workplaces are generally expected to have decent canteens serving hot food, which is eaten communally; and some even provide beds for post-prandial naps.

So, as Chinese youths ironically embrace our sad, lonely Tupperware lunches, perhaps we could turn, nonironically, to Szechuan crab, dan dan mian, chicken rice, Peking duck and lashings of jiaozi – followed by a nice sleep. It seems like a good exchange.

Richard Godwin

12 The Oldie August 2023

White lunch

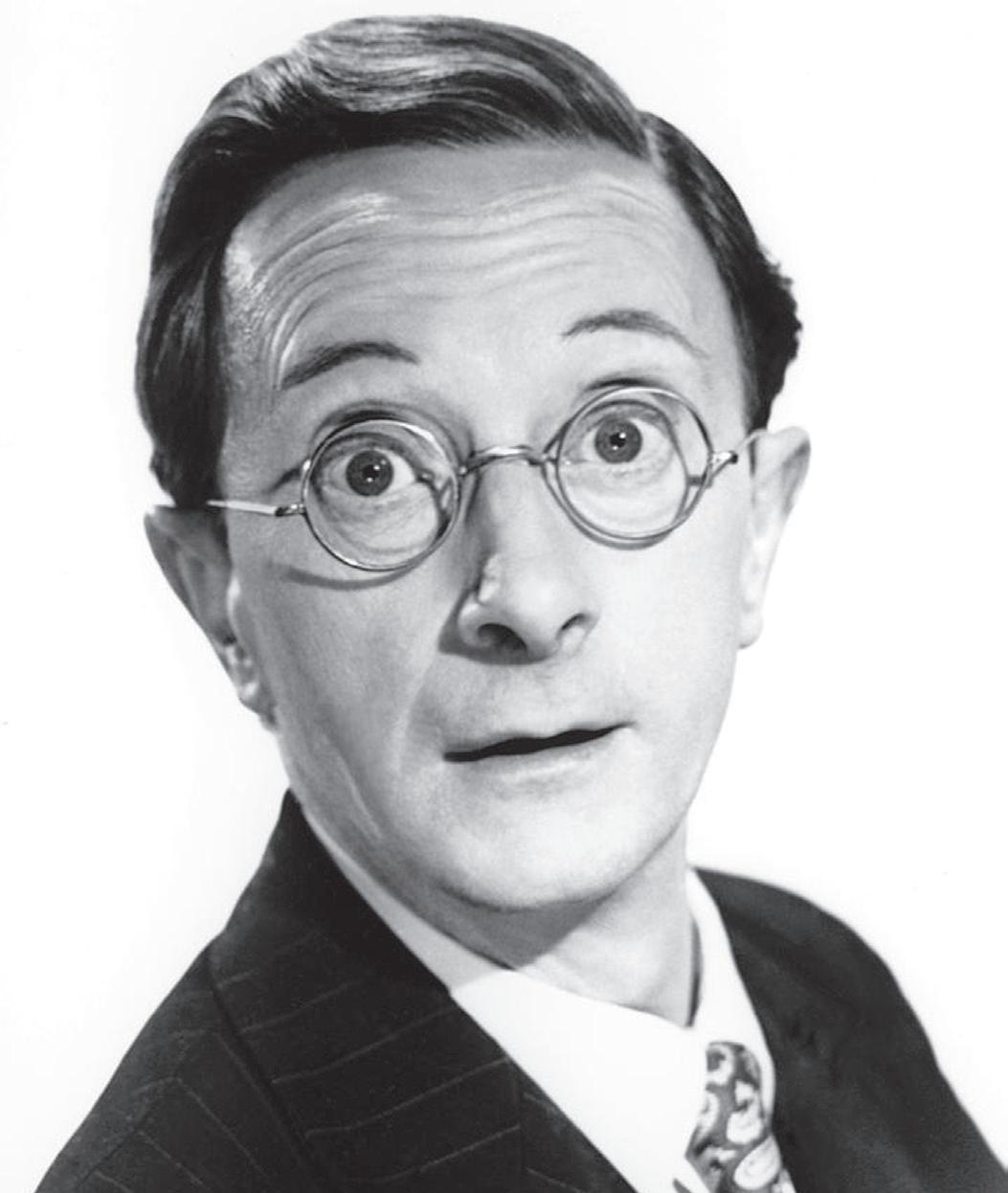

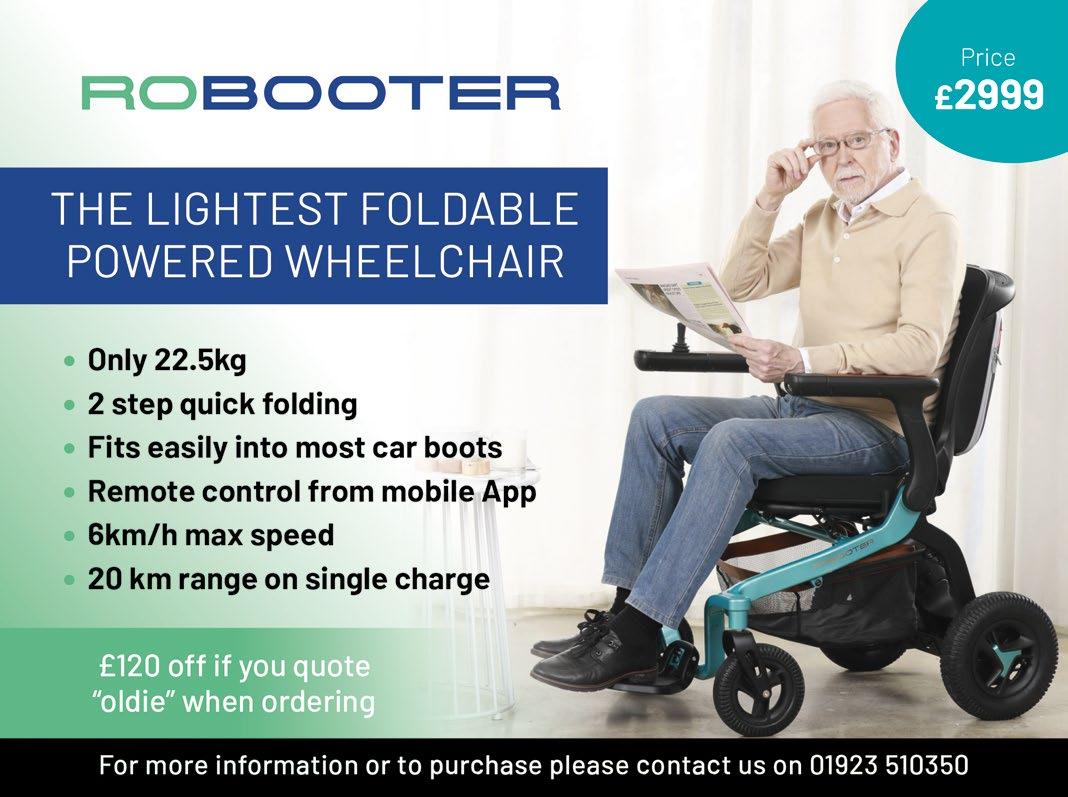

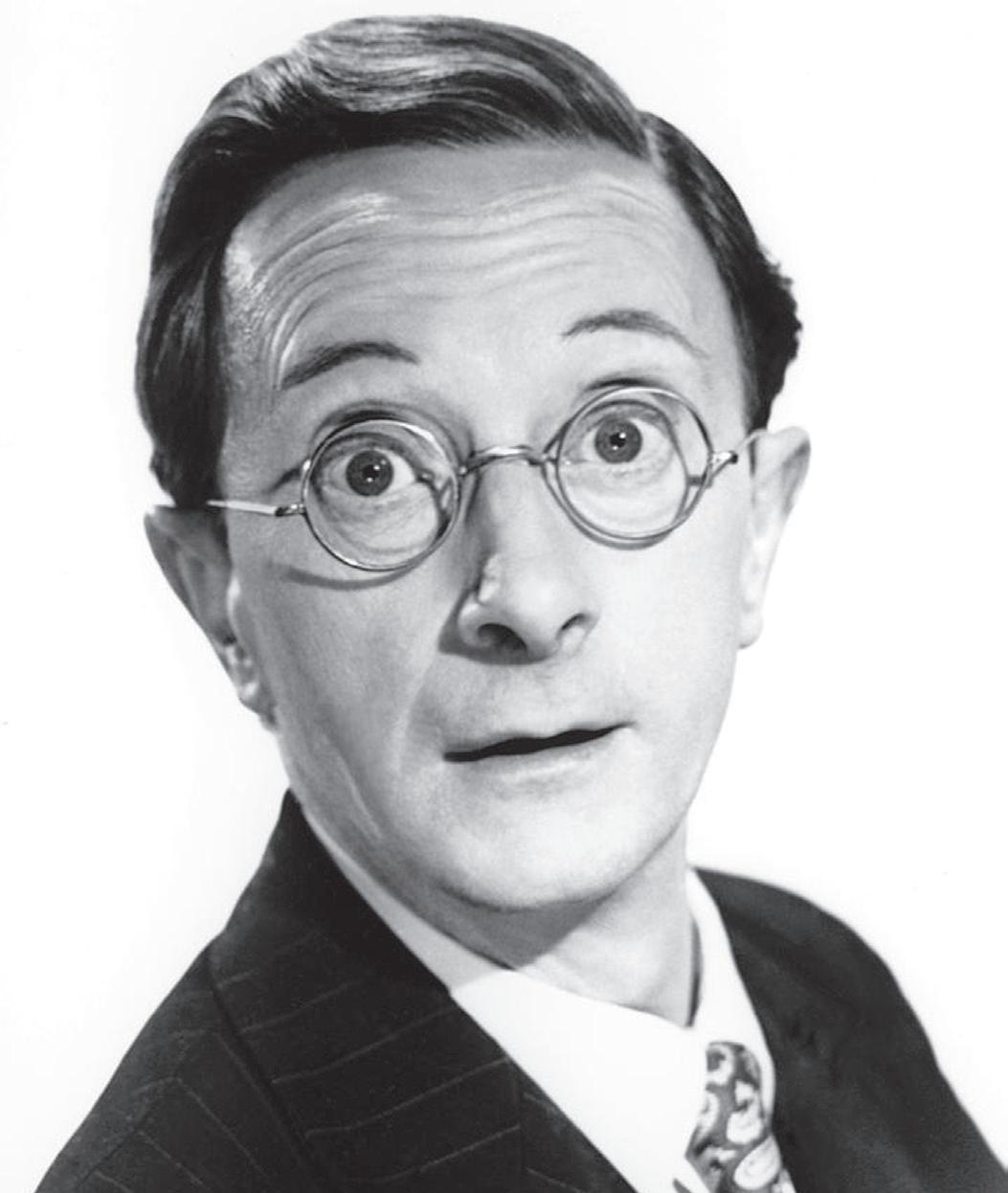

Thirty-five years after Charles Hawtrey’s death, his biographer Roger Lewis salutes the funniest Carry On star – and Barbara Windsor’s favourite

King Charles

Abook worth having would be a gazetteer of our great and generally unsung character actors, supporting players, comic turns – stalwarts such as Richard Wattis, Raymond Huntley, Colin Gordon, Eric Barker, Julian Orchard, Jonathan Cecil and, of course, from the Carry Ons, Charles Hawtrey.

Hawtrey, like those others, was never the centre of attention. He had little to do with plot development. He wasn’t required for romantic interludes. He simply stood there, as Private Widdle, Tonka the Great or the Duc de Pommfrit, smirking slightly and glancing from side to side, unmistakably his eccentric self.

Whenever he appeared (‘Oh, hello!’), the scenes would be given a reliable boost, a dependable bounce. Audiences immediately relaxed and knew they were about to enjoy themselves.

Barbara Windsor said, ‘He was my favourite actor in the team,’ and Hawtrey is certainly the one who remains genuinely funny today.

Kenneth Williams now seems too shrill, with a personality like a pan of milk boiling over. Sid James’s cackling lechery is hard to stomach. The oafishness of Bernard Bresslaw was seldom amusing, and I never could stand Kenneth Connor gulping with sexual frustration. Peter Butterworth, in fairness, excelled at shiftiness.

It is Hawtrey, however, who was imbued with a true comic spirit. He had complete confidence in himself, especially when it came to camp innuendo: ‘He could toy with his dirk’; ‘Oh, don’t make it hard for me’; ‘She’s helping me stick my pole up’; ‘My thing’s caught’; ‘I can’t do it lying down’ and so forth – Talbot Rothwell’s endless bottom jokes and knob gags.

I cherish this exchange, in Carry On Henry: ‘Your hand on it,’ says the king, intending to seal a contract. ‘I never even put my finger on it,’ replies Hawtrey’s Sir Roger de Lodgerley, thinking he’s referring to Joan Sims.

Hawtrey was born in Hounslow in 1914 as George Frederick Joffre Hartree. Perhaps he changed his name to create confusion with a debonair West End actor and manager, popular at the turn of the century, Sir Charles Hawtrey (1858-1923).

Whatever the motivation, he attended the Italia Conti singing and dancing academy, and recordings were made of his boy treble. Hawtrey was in seasonal shows with names such as Bluebell in Fairyland, and he was often cast as a Lost Boy in Peter Pan. His Captain Hook at the Palladium in 1936 was Charles Laughton.

Like Elizabeth Taylor, therefore, Hawtrey began as a child actor and remained one. He had the demeanour always of an elderly child, who never fully grew up.

Starting in 1932, he co-starred in several Will Hay films, as the bespectacled, elfin class-swot. During the war he appeared in revue, joining Judy Campbell, Jane Birkin’s mother, when she delivered A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square. Calling himself Charlotte Tree, he perfected a drag act

– more Danny La Rue than Dame Edna. On the night the Café de Paris was bombed, Hawtrey helped carry buckets.

Hawtrey was directed in Shakespeare at the Old Vic by Tyrone Guthrie and did occasional Sunday concerts reciting the classics. I wish he’d been offered the chance to do more of this sort of thing. He’d have been ideal in Restoration Comedy, Sheridan or Congreve.

In 1969, he was marvellous as Marley’s Ghost in a spoof of A Christmas Carol: ‘I say, how much longer do I have to stand here moaning and clanging?’

Instead, there were endless bit parts in black-and-white films. I spotted him as a station porter in a Powell and Pressburger picture. As pale as a parsnip, elongated and undulating, with no dialogue, he’s apparent in Passport to Pimlico (1949) – playing the piano in the pub, looking cheerful in crowd scenes.

No doubt Hawtrey could have gone on playing these small roles for ever – he was in a now-lost television series called Our House (1960) – but nothing was going to be memorable. He turns up in

14 The Oldie August 2023

RANK ORGANISATION FILM

Oh, hello! Charles Hawtrey

Dentist on the Job (1961) and is to be glimpsed in What a Whopper (1961). I spotted him in The March Hare (1956) and in Brandy for the Parson (1952), with Kenneth More.

But it’s the 20 years Hawtrey spent making the Carry Ons that grant him immortality.

Peter Rogers and Gerald Thomas released a sort of smiling devilry in him. As a recruit in Carry On Sergeant, the first of the series, in 1958, instead of being weak and mincing, Hawtrey thoroughly enjoys bayonet practice: ‘You beast, peasant, commoner, have at you, varlet!’

He became adept at conveying mad courage, whether dragged up as an undercover policeman in Carry On Constable (1960), or as an effete French aristocrat in Carry On Don’t Lose Your Head (1967). Awaiting his turn at the guillotine, he is handed a letter. ‘Drop it in the basket,’ Hawtrey says nonchalantly. ‘I’ll read it later.’

In all these cheap films set in hospital wards, schools, army barracks, the North-West Frontier (actually Snowdonia), the Sahara desert (Camber Sands) or the resort of Elsbels (the Pinewood car park), where Kenneth Williams flinches, snarls, recoils and hisses, Hawtrey twinkled.

In Carry On Cleo (1964), which used sets left behind from the Taylor/Burton Cleopatra, Hawtrey, in Hume Cronyn’s costumes, totters about the palace as the ‘dirty old sage’.

Hopping along the country lane in Carry On Camping (1969), his pots and pans jangling in his rucksack, he’s supremely happy, as he is wearing a kilt in Carry On Up the Khyber (1968).

Boarding the holiday coach in Carry On Abroad (1972), he is peerlessly blithe. ‘Where’s the crumpet?’ he is asked. ‘Oh,’ says Hawtrey, ‘I don’t think they’ll be serving us any tea.’

It’s a tragedy, however, when an artiste knows his worth and is inadequately rewarded. Hawtrey felt insulted to be relegated beneath Hattie Jacques in the billing, yet Peter Rogers refused to improve his conditions, or to pay him as much as Sid James. None received repeat fees.

When Hawtrey complained, Rogers sacked him. He was replaced by dire Lance Percival in Carry On Cruising (1962) and by dreary Norman Rossington in Carry On Christmas (1973). Disappointed, Hawtrey started drinking – and he was drinking on the set, gin concealed in lemonade bottles.

Instead of waiting for him to sober up, Thomas kept the cameras rolling. This is why in Carry On Spying (1964) Hawtrey is flat out in the background. In Carry On Abroad, he is seen swigging what appears to be suntan lotion. He is soon flat out on the beach. In Carry On at Your Convenience (1971), during the works outing to Brighton, Hawtrey staggers along the pier and is shortly flat out in the charabanc boot.

It is a paradox that a celebrity who gave the public so much pleasure became increasingly renowned for off-screen peevishness. Lunching daily on brown Windsor soup at the cafeteria in Bourne & Hollingsworth, Oxford Street, Hawtrey

was unapproachable. He refused to grant autographs and was a tricky customer with photographers.

‘No, bring me a nice gentleman instead,’ he’d insist, when for publicity purposes he was meant to pose with busty starlets.

In 1968, Hawtrey moved to Deal, drawn to the delights of the bandsmen at the Royal Marines School of Music. To this day, he is remembered with dread in the town, where he was barred from all the pubs because of his antics.

In 1984, his house burned down, a rent boy having dropped a cigarette down the sofa. Hawtrey was found by rescuers in bed holding a melting telephone.

When the fire brigade carried him down their ladder, Hawtrey insisted on climbing back up, as he’d forgotten his wig.

Having barely worked since 1972, he died 35 years ago, on 27th October 1988, aged 73. Smoking had caused arteriosclerosis and his legs needed to be amputated – an operation he refused. ‘I want to die with my boots on,’ Hawtrey said.

When the nurse asked for his autograph, he threw the water jug at her. His funeral was attended only by the undertakers.

I wish I knew where his remains were interred or his ashes scattered. I’d like to pay homage.

The Oldie August 2023 15

In Carry On Again Doctor (1969)

As Private Widdle, with Peter Butterworth and Joan Sims, Carry On Up the Khyber (1968)

Roger Lewis is author of Charles Hawtrey 1914-88: The Man Who Was Private Widdle

My road to nowhere

Ican’t drive. Not ‘I don’t drive’, ‘I haven’t got a car’ or ‘I would rather not drive’. I really can’t drive. Now that I’m looking back it doesn’t seem such a big deal, but in the ’70s driving was the Holy Grail for young people and not driving was almost as bad as not being able to read.

When I turned 17, learning to drive seemed as if it would be a doddle.

‘Ten lessons should do it,’ my driver friends hooted enthusiastically. Alan, my first instructor, took me out in his immaculate Mini and invited me to get behind the wheel. We jumped up the road for a bit.

Twenty minutes later, we stopped. Alan unglued my rigid hands from the steering wheel and I tried to relax my toes which had plaited themselves in knots of agonising cramp.

Alan, smiling but a bit rigid, assured me that the first lesson is always a ‘breaking-in’ period and it would get better. But it didn’t, and Alan bit the dust. If anything, it got worse.

Seventeen years and as many driving instructors later (I changed them every year), I was still a non-driver, without even one test under my seat belt. It wasn’t cool. Everyone I knew could drive. Well, apart from my sister. She couldn’t drive. Yet.

Not driving stood in the way of a lucrative career in journalism. I worked on a newspaper and had to catch the bus everywhere. On jobs, I would say that I had parked round the corner and then slink off to the bus stop.

I met my 18th instructor around this time. This one seemed OK. He once stopped my wild screams when I approached a roundabout. He didn’t moan when I dirtied his paintwork by slithering around too near the pavement on wet days and, for the first time, the cramps in my feet unknotted. So, reader, I married him.

I think that this was the nearest to

driving success I ever reached. It wasn’t happily ever after, though. A few years later, the marriage failed the test and I looked around for another instructor.

I also looked around for a new job. It wasn’t easy, but I had a strategy. When the inevitable question ‘Do you have a clean driving licence?’ arose, I had three stock answers. The first was a direct negative, but I would tear up and hint at

Much later, I joined the BBC as a newsroom broadcast assistant. But promotion depended on having driving skills, and without them I would remain grounded in the newsroom.

So back to the sheer terror of driving lessons. Because my sister was now taking regular lessons, sibling rivalry also entered the equation.

The madness finally stopped 45 years after my first sweaty, crampy session in the Mini, when I finally gave up. One day, I was prowling around the newsroom with that just-before-a-driving-lesson look. The usual nausea had set in.

A colleague noticed my heaving green face and asked me what the problem was.

‘Driving lesson soon,’ I gasped, fresh waves of sweat breaking out.

He gently took me aside and told me that he too used to suffer like this. In fact, he was so awful that, during a particularly bad test, the examiner abandoned him in the car, preferring to walk back to the test centre. Sitting there in the car, he came up with the ideal solution –give up.

a mysterious medical condition, which meant it was impossible for me to get behind the wheel. To my relief, no one asked what that condition was and we moved on swiftly to the next question.

The second answer was that I did have a clean licence. How were they to know it was only a provisional one? The third answer came with an outraged look, as I told them that I don’t drive. This implied that I used to drive but my love of the planet now prevented me from doing so.

He told me there are some things in life you really can’t do. It doesn’t mean you are stupid or less of a person. You just can’t drive – it’s not the end of the world. In fact, the world is greener because of non-drivers.

I picked up the telephone, cancelled my lesson and dropped ten years.

The man who gave me the advice spoke so much wisdom. So, reader, I married him too – and I intend to never have another lesson.

Life is sometimes a bit tricky. We walk a lot, and for every house move we have to consider the proximity of shops, railway station and a doctor’s surgery – but I am so much happier. The joys of giving up should never be underestimated.

Incidentally, my sister passed her test.

16 The Oldie August 2023

After 45 years learning to drive, Jennifer Florance has finally given up – and she’s never been happier

After 17 driving instructors, I was still a non-driver, without even one test

‘No problem! I read the lesson on how to fill out accident reports’

Maggie’s tip for first-time buyers

A guide to house-buying by Anne Robinson – and Mrs Thatcher

Not long before her departure from the political scene, I was invited to a Christmas lunch at Lord McAlpine’s country house, where Mrs Thatcher and Denis were the main guests.

We were 12 in all: an odd mix, including Terence Donovan, Mrs T’s favourite photographer, Olga Polizzi and her husband, William Shawcross, and Henry and Tessa Keswick.

In the slightly awkward pre-lunch drinks, I was standing with two other guests and Mrs Thatcher when, out of nowhere, she announced (and this is best done in a slow, deliberate voice after a couple of gins):

‘I always say to young people, “Buy a big house when you first get married and then you don’t have to move.”’

‘Yes, Prime Minister,’ chorused the other two.

I couldn’t help myself: ‘But, of course, Prime Minister,’ I responded haltingly, ‘not everyone can afford a big house when they first get married.’

She turned to face me full on.

‘I bet,’ she said, ‘you’ve made some money out of houses while I’ve been in office.’

By golly, I had. In the eighties, flipping West London properties paid far better than journalism or being a quiz-show host. As a result, I was known to every silk-socked, tassel-shoed estate agent in Kensington. John D Wood, who inexplicably favoured hiring young officers from the Blues and Royals, invited me one year to their office Christmas party.

And when they sent a new girl to take me to a viewing, I automatically asked what regiment she’d served in.

Alas the last two decades have produced a harsher world. Those posh boys from the big firms are now charged with making thirty calls a day, and from 15 viewings they need to achieve one offer – or they’re out.

That means the single operators –often called finders – are thriving. They

have good contacts, people skills and importantly the time to play nanny, shrink, best friend and even ‘close companion’ until the magical words ‘We’ve exchanged’ are uttered.

Cannily one of this tribe has now written an anonymous – he goes by the nom de plume Max –account of a year in his life selling super-prime homes in London. If you are as devoted to Location, Location and Kirsty and Phil as I am, you’ll be gripped.

There’s the Oscar-winning actress who always arrives five minutes early. The billionaire so rude and foul he makes Kanye West seem like Mother Teresa. The sad, deserted wife, the American influencer who may or may not have the price of a Tube ride and the National Treasure in the Cotswolds with an ugly, almost unsaleable 1910 pile.

Best of all is ‘Uncle Fortescue’, who belongs to Natasha, the aristocratic assistant in Max’s office. Uncle Fortescue lives in Victoria Road, W8. It doesn’t come more desirable in Kensington, except that the inside of Uncle Fortescue’s home is a filthy slum for which Uncle Fortescue wants an unrealistic ten million.

Plus he only wishes to sell to an Englishman. Not any sort of Englishman. Because when a wealthy trader from Yorkshire shows an interest, Uncle Fortescue instantly objects because he’s common.

The author also describes showing me a house and ‘twittered on about the joys of an ensuite bathroom’ when I cut him short with, ‘You’ve got a non-speaking

role.’ Quite right.

These days, I don’t wait that long. As we enter a property, I tell Rupert, Giles or Tarquin to imagine my mobile is a remote control pressed to mute him. And unless I hold it up to his face, I wish to hear nothing. Especially not the blindingly obvious.

I don’t recall the encounter with Max, but he comes across as an absolute sweetie. For months, he patiently wraps a protective arm round Zara when her horrible husband goes off with the Pilates teacher and she and her children must find a new home for half the price of a Notting Hill mansion.

The answer is Queen’s Park, where a four million price tag is not unusual and there are now apparently more Filipinos emptying dishwashers than there are in Belgravia.

Max is gay and in a bit of a muddle about his life. Meanwhile, his small team variously fall in and out of love with each other, their clients and, worse, their clients’ unreasonable, spoilt, horrible children.

In a struggle to discover a more meaningful direction, the author even records regular visits to his shrink, Quentin. I like the sound of Quentin, who is no slouch.

For one appointment, he announces they are going on a field trip. Specifically, to visit a sex shop, the Clonezone.

The quest is for Max’s sexual liberation. Once he’s there, in a spirit of helpfulness the salesman in leather chaps explains of an item on display, ‘This can bring you to orgasm without a physical touch to the actual phallus.’

If that moves you more than the property dramas, the address is 266 Old Brompton Road, London SW5 9HR.

Highly Desirable – Tales of London’s Super-Prime Property from The Secret Agent by Anonymous (Headline, £22) is out now

The Oldie August 2023 17

The PM said, ‘I bet you’ve made money out of houses while I’ve been in office’

Maggie the Builder: at Canary Wharf, 1990

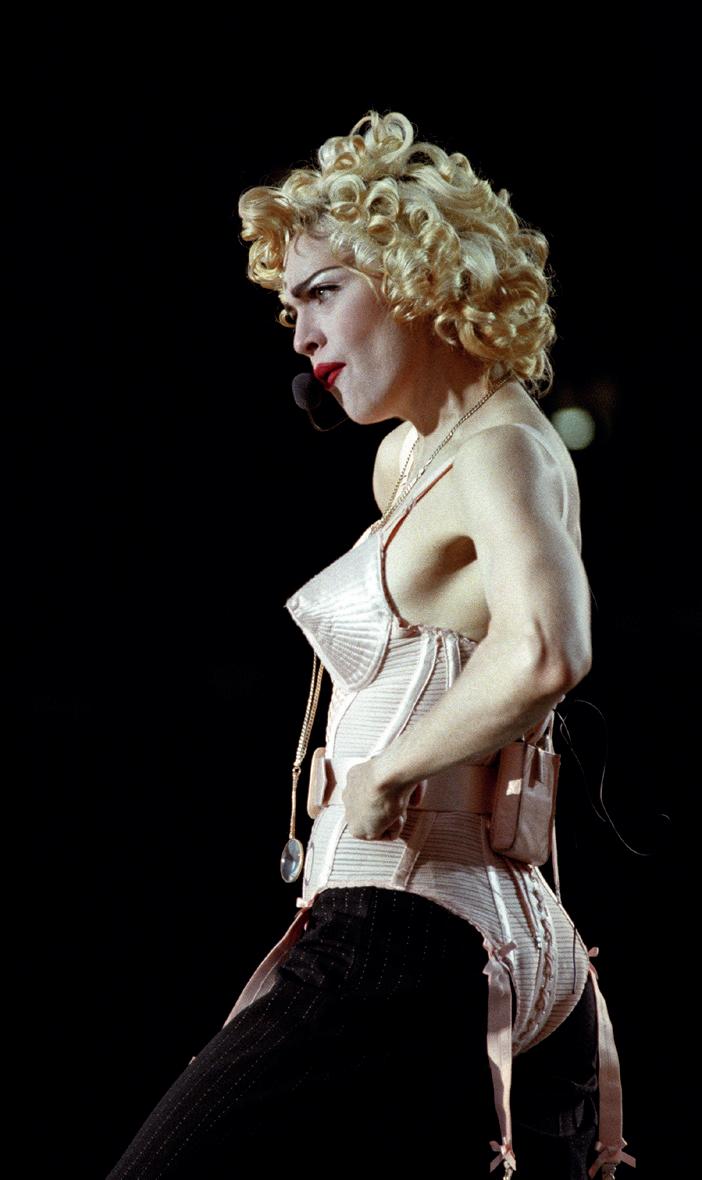

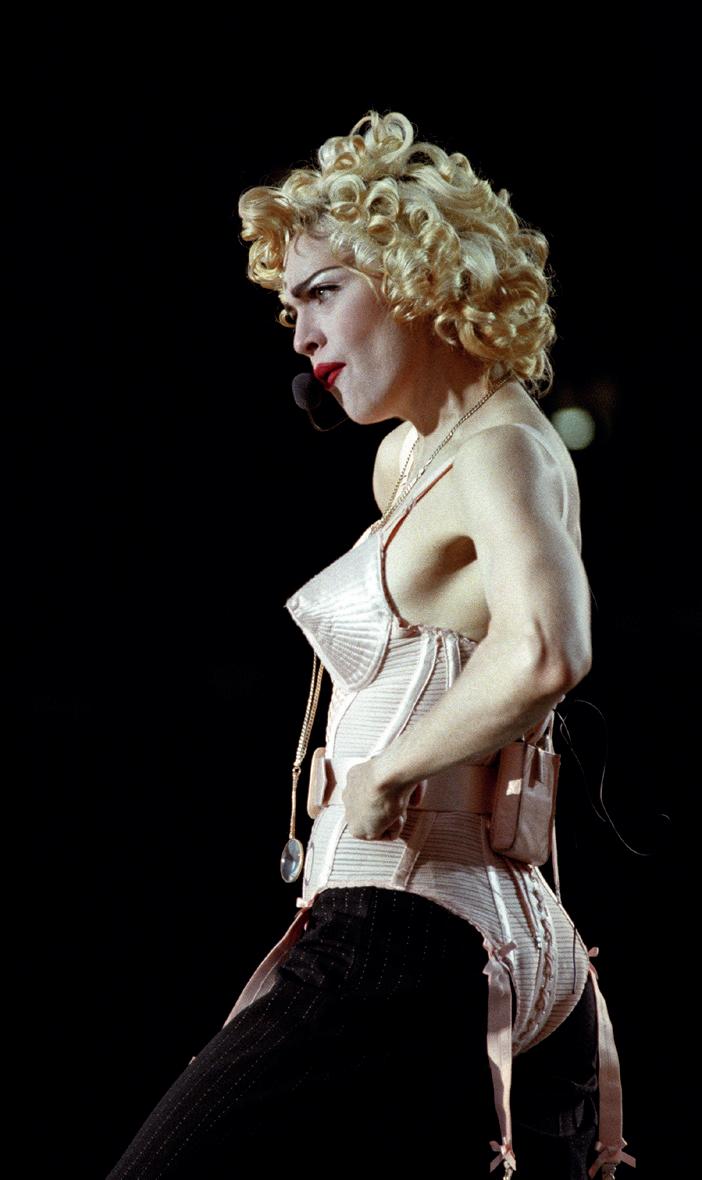

RIP the glamourpuss

Marilyn Monroe, Audrey Hepburn and Jackie O all had it – before Instagram and celeb egomania destroyed glamour. By Charlotte Metcalf

Botox, fillers and surgery have made cosmetic perfection attainable and banal. And celebrities are constantly baring their souls or revealing their ‘truth’, rendering their over-shared life stories banal – and distinctly unglamorous.

How times have changed since Peter Sarstedt’s 1969 hit Where Do You Go to (My Lovely)? defined glamour. Allegedly about Sophia Loren, it portrays a beautiful woman pursued and fêted by the richest men in the world, gliding effortlessly between St Moritz, Juan-lesPins and her Parisian apartment.

Only the singer knows of her humble beginnings in the backstreets of Naples. Even now her past is widely known, we still picture the movie star alighting in Capri from a Riva before being whisked off to a secret rendezvous in a scarlet convertible.

Rags-to-riches stories are nothing new, and many celebrities today have clawed their way out of modest, if not downright tough, working-class beginnings.

Yet what strips most of them of glamour is not their struggle but their propensity to talk about – even boast of – their pasts. Stories of depression, abuse, breakdown, drugs, alcohol and rehab abound, almost as a rite of passage.

Did we stop to wonder whether Cary Grant or Brigitte Bardot grew up in a trailer park? We knew Marilyn Monroe was emotionally vulnerable, but her reputation as an irresistible siren remained intact, mainly because she never sat on a sofa chatting to a cosy daytime-television host about being Norma Jeane.

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton might have conducted their wildly volatile love affair in public, but the idea of either of them sharing images of their private life on Instagram or signing up for I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! is unimaginable.

‘Glamour’ no longer implies an elegant figure slipping into the Ritz behind stylish sunglasses. Instead, we think of raunchy underwear models or the

scantily-clad compères of shows such as The X Factor or Love Island

Even then, we’re bombarded with unflattering phone snaps of them caught unawares, or interviews about their collagen intake or fashion tips. Movie stars like Lauren Bacall have never seemed so distant.

The ease with which we can find out every detail about famous people today has rubbed the sheen from even the most impressive figures.

Take the American First Ladies. Jackie Kennedy was glamorous, remaining publicly dignified as a tragic widow before being rescued by a Greek tycoon.

Yet the First Ladies of recent years fail to make the grade. Melania is ruled out by dint of her gold-digging proximity to Donald. Hillary’s garish blue pant suits alone disqualify her. Michelle was making the grade until she tore up the rule book by over-sharing in her own book Becoming. To remain glamorous, preserving an aura of enigma is essential.

Princess Diana stopped being glamorous the minute she revealed her misery to Martin Bashir. The nation held its breath as she revealed her egocentric frailty, rendering her a pitiful victim rather than the hard-working, charming beauty we’d previously admired from afar. And we have only to look at her son and Meghan to witness the damage caused by endlessly communicating their ‘truth’.

We want our heroes and heroines inscrutable, like swan-necked Princess Grace. Yet we’re in an age of Instagram, tell-all Q&As, Hello! magazine, self-help books and Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle

website Gloop. The word ‘lifestyle’ alone would be frowned upon by Nicky Haslam as ‘common’. It’s hard to imagine Marlene Dietrich selling a candle on-line that smells of her vagina.

The new exhibition Diva at the V&A sets out to explore how the diva’s role has changed and been subverted over the years. From performers such as Billie Holiday, Maria Callas and Vivien Leigh via Whitney Houston and Tina Turner, the exhibition turns to current divas such as Elton John and Lizzo.

It’s a fascinating subject for a museum famed for celebrating fashion to embrace, tracing how elusive glamour has given way to flamboyant extravaganza and camp spectacle. And this goes hand in hand with gushing emotion – just look at the recent Oscar acceptance speeches.

In his brilliant book Fracture, Matthew Parris, who presents Radio 4’s Great Lives, argues that many great lives are shaped by trauma. While that remains true, the constant exposure of our inner lives to public scrutiny has eroded glamour, even though the mentalhealth benefits of emotional openness are undoubtedly plentiful.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines glamour as an attraction or appeal that enchants, casting a magical spell.

The last time I saw anyone do that was in the early ’90s, when Audrey Hepburn, as a Goodwill Ambassador, made an appeal on behalf of UNICEF at the Palais des Nations in Geneva. In a plain, brown dress, skeletal with cancer and with hardly any hair, she talked passionately and eloquently about the children in need of our help.

She said not a word about herself and bewitched every one of us, not just with her compassion and beauty but with her humility and restraint –glamour personified.

18 The Oldie August 2023

The Diva show is at the V&A until April 2024

Monroe in The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

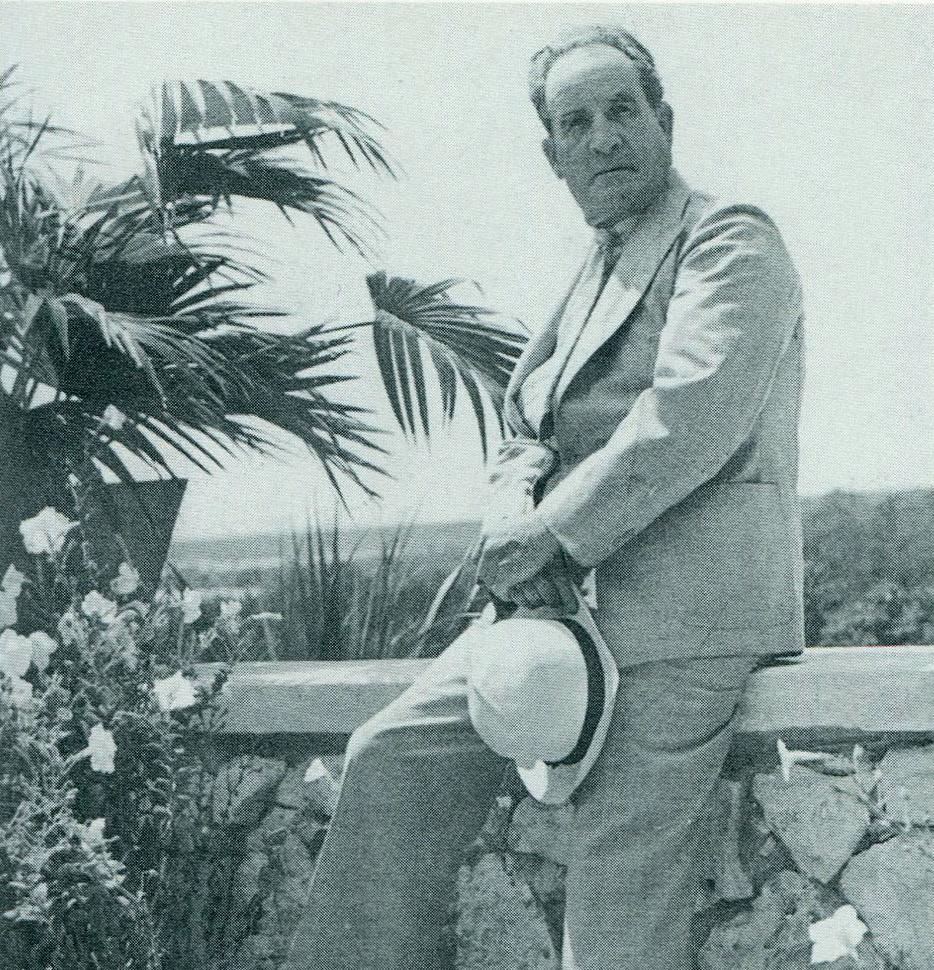

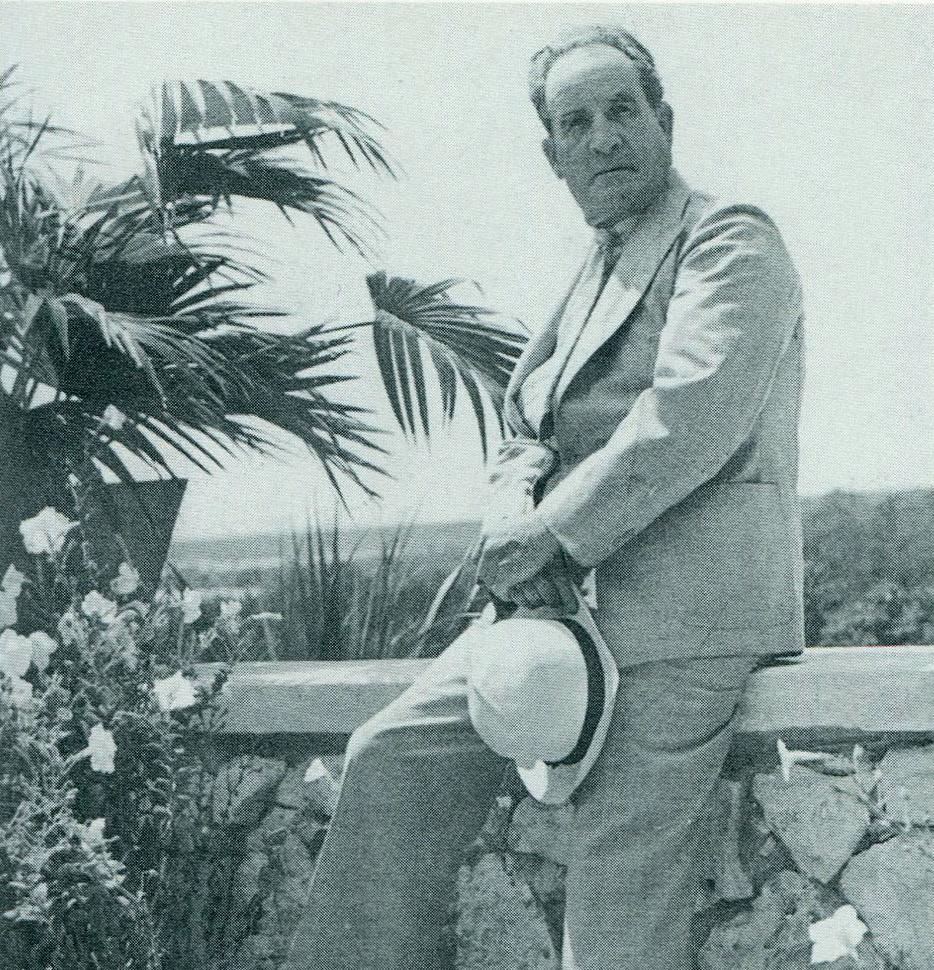

Murder in paradise

Sir Harry Oakes, a tycoon friend of the Duke of Windsor, was killed in the Bahamas 80 years ago. That night, a young Charles Owen was nearby

The night of 7th July 1943 was heavy with an approaching storm.

My sister and I were in our beds. Our mother came to kiss us goodnight before going out to dinner. I asked her if she was going to Government House. The incumbents were the Duke of Windsor, now Governor of the Bahamas, and the Duchess.

‘No,’ she whispered, ‘and what a relief. Wallis always teases me because I have nothing decent to wear. It all went down with the ship.’ She was dining with friends, she said, ‘and after that we are going to play Murder’.

Lying awake in the dark and the heat, we could hear the cockroaches running up and down behind the wainscoting. The maid had shaken disinfectant powder in cracks in the walls and the creatures, like us, were finding it difficult to settle.

We were renting an old plantation house in Nassau. Fifteen months earlier, we had been aboard the Blue Funnel liner Ulysses, two weeks out from Australia, bound for Liverpool, when the ship was torpedoed by a German submarine and sent to the bottom. We were rescued by a US Navy corvette and taken to Charleston, South Carolina.

Later we moved to Nassau, which was in the sterling area, to wait for a convoy to take us back to England. I was eight years old. Several of my contemporaries on the island became well known later.

Jimmy Goldsmith and I shared a bench in the schoolroom. I remember one morning when he was looking forward to tennis lessons and his mathematics teacher had to tell him off for practising strokes with his racket instead of paying attention.

That night in July, the storm struck Nassau shortly after midnight – thunder and lightning, the waves surging up the beach and the rain coming down in sheets. By the time it had blown itself out, Sir Harry Oakes, Bt, one of the world’s richest men, had been

bludgeoned to death and set on fire in his beachfront home.

Born in Maine, Oakes made his fortune in Canada as a gold-prospector, living under canvas in freezing conditions, often existing only on scraps. Settled in Nassau, where his huge wealth was sheltered by minimum rates of tax, he was a large employer of native labour.

A keen amateur golfer, Oakes was due to play the Duke of Windsor on the day his body was found. He owned the course and had the habit of irritating his opponents by using his bulldozer to change holes and bunkers overnight between rounds.

Count Alfred de Marigny, born in Mauritius, twice divorced, good looking in a rakish sort of way, with a yacht named Concubine and a hereditary courtesy title, was known to his friends as Freddie. He was also Sir Harry’s son-in-law, having married the Oakeses’ daughter, Nancy, as soon as the beautiful young woman had come into her inheritance.

Relations between Marigny and his father-in-law were strained and the two hadn’t spoken for several months. On the night of the murder, shortly after 1am, Marigny had driven two dinner guests to their home about a hundred yards from

Oakes’s house. The timing and the location, along with his known antipathy to Oakes, were potentially incriminating. Marigny was arrested, remanded in custody and escorted to jail.

The Duke of Windsor, whose open dislike of Marigny was no secret, secured the services of two detectives, members of the Homicide Bureau, Miami. At the magistrate’s hearing, the court learned that Marigny was in dire financial straits and that Oakes was in the process of changing his will, putting Nancy’s share of her inheritance beyond her reach until she was 30 – which was 11 years distant. Moreover, Marigny had been heard making threats against Oakes.

At the end of August, Marigny was committed for trial when the Quarter Sessions opened in October. He was returned to his cramped prison cell and its sweltering heat for a further five weeks. A rope was ordered from the chandler for the hanging.

The murder inquiry revealed that, on the night of the murder, Oakes’s wife had been away. Oakes had had some guests to dinner and one of them, Harold Christie, a real estate developer, had stayed the night to avoid driving home in the storm. It was Christie who had found Oakes’s body the following morning.

In the trial, it proved impossible for the police to establish definitively how and where Oakes had been killed. Under rigorous cross-examination of Marigny, the fingerprint evidence against him fell apart and he was acquitted.

He received a telegram offering congratulations that he had ‘won by a neck’. The jury took a more jaundiced view and recommended that he be deported.

The crime remains unsolved. Over the years, people who have continued to probe for answers have met with unexplained ‘accidents’.

Despite this discouragement, there are others who are still trying to unravel the secrets of what has been called the greatest murder mystery of all time.

20 The Oldie August 2023

Sir Harry Oakes, 1st Bt (1874-1943), at The Caves, one of his six homes on the Bahamas, 1940

Elizabeth I’s love nest

By Quentin Letts

Snodhill Castle is England’s newest Norman ruin.

More than 900 years old, it is only just starting to surrender some of its misty secrets, including a rediscovered royal chapel.

Most castles were well documented, having for centuries required military funds. Of Snodhill there is, in historical records, oddly little mention.

Were clerks instructed to lift their quills out of the ink and keep its existence classified? Was this remote site in western Herefordshire a secret base? Or was it a romantic hideaway for royalty?

On a Bank Holiday Monday earlier this summer, a hundred locals clambered up Snodhill’s grassy motte, as indeed any modern visitor can, to inspect an archaeological find.

Television journalist Nik Gowing chaired proceedings. The actor Robert Bathurst read from the diaries of Francis Kilvert, the Victorian clergyman who picnicked on Snodhill’s tree-covered mound on Midsummer’s Day in 1870.

Kilvert and friends drank punch and boiled a saucepan of new potatoes, the men smoking and talking politics while the women did much of the work. Little changes.

From Snodhill’s ruins, fringed by oxeye daisies and the occasional spear of hemlock, the views of Herefordshire’s Golden Valley are certainly divine.

Below lie fields with Anglo-Saxon hedges, sheep’s bleats rising from distant meadows. To the oak-dotted horizon stretches a deer park where aristocrats could gallop and cavort. One area was known as a lovers’ water meadow.

Not that it was all pleasure. From the 12th to the 15th century, the Marches saw repeated biffing of and by the Welsh, during raids by Llywelyn the Great, Dafydd ap Gruffydd and Owain Glyndŵr. Snodhill, sometimes called Snothill, was one of several Marches forts but none was so little chronicled and none had a royal chaplain.

Under its main tower, the Bank Holiday visitors were shown the outline

of the royal free chapel uncovered by Herefordshire Council’s archaeology department. The chapel’s existence was common knowledge but its location had been long lost.

There had been speculation it stood outside the castle but here it was, right in the bailey, near private apartments better suited to a boutique getaway than to a rural garrison.

The dig found evidence, furthermore, of frenzied destruction, probably by 17thcentury Puritans, who left the chapel’s ornate interior in rubble and its sacred artefacts bent out of shape. Behind the altar was a lockable chamber where valuables – or lovers? – could be concealed.

Garry Crook, chairman of Snodhill Castle Preservation Trust, noted the rare level of violence with which the chapel was wrecked. Whoever destroyed it was in the grip of moral outrage.

Could it not simply have been a general’s tactical desire to put the place out of military action? Maybe, but Snodhill saw no battle action in the Civil War and the nearest siege, at Hereford, was pretty low-key. Two cannonballs exist in a house near the castle, but it is thought they are souvenirs from elsewhere. In recent centuries, they were used as cheese presses.

Until five years ago, the castle was engulfed by vegetation and was home to deer, redstarts and badgers, whose setts undermined the masonry.

Then a preservation trust got going, volunteers hacking away centuries of gorse and securing funds from the likes

of Historic England and the Garfield Weston Foundation.

Walls and the north keep were rescued from collapse. Timber felled in the work was turned into salad bowls, which are being sold to raise funds.

‘There is a lot more of the castle to see today than there would have been in Kilvert’s time,’ said Surrey Garland, a Snodhill trustee.

A former bishop of Hereford, John Oliver, who in younger days often clambered over Snodhill with his family, became the first bishop to say a blessing at the chapel for hundreds of years.

The chapel was a ‘royal peculiar’, which meant chaplains were chosen by the monarch rather than by some finger-wagging prelate.

For such a small baronial castle to be a royal peculiar may have been unique. One of Snodhill’s chaplains was the composer Robert Fayrfax, the Elton John of Henry VIII’s day. His songs included ‘I love, loved and loved wolde I be’.

Ash trees at the site date to the 16th century. In 1563, Elizabeth I gave Snodhill to her intimate, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester.

A lover’s parting gift? Dudley kept Snodhill for only four years. We may not know – we cannot tell – but maybe this rural idyll stirred such painful memories for him after his fall from Elizabeth’s favour that he could no longer bear to visit it.

‘The man must indeed be of a mind void of imagination,’ wrote T Prosser Powell, a 19th-century local squire, ‘who can stand here on the ruin of this old border castle, where lords of the Marches fought and sported and loved, and say such a spot is utterly uninteresting. How difficult it is to sweep aside the cobwebs of ages and look into the dark corners of the story of these border chiefs.’

Why did Powell say ‘fought, sported and loved’? Did local gossip from Elizabethan days survive to Victorian times?

Was Snodhill Queen Bess’s love nest?

For years, Snodhill Castle was engulfed by gorse and badgers’ setts. Newly restored, it has now revealed royal secrets.

Quentin Letts writes for the Times

The Oldie August 2023 21

England’s newest Norman ruin: Snodhill

Letter from America

A criminal tale of two cities

Stranded by bad weather the other day in Portland, Oregon, I took a walk.

The town still prides itself on its 1880s converted sawmills-and-saloons ambience. But, surveying central Portland from a nearby hilltop, I was struck more by the similarity to Dunkirk in 1940.

Several hundred homeless residents, looking like the remnants of a defeated army, were hunched together around braziers or lying in rows of cots on the pavement. No one in Portland bothers about the remaining laws against public drug use or befouling the streets.

The much-shrunken, demoralised police department, its budget slashed in the wake of the George Floyd riots of 2020, currently has just 749 officers, its lowest total since 1980. The city has added 175,000 new residents in the same period.

Just outside this toxic bubble, there’s the ‘real’ Oregon, represented by a long chain of bucolic hamlets inhabited by friendly, well-dressed men and women. It’s a world essentially unchanged since the days of JFK in the White House and Dean Martin slurring his way through That’s Amore on the radiogram.

It’s as though the whole area has somehow managed to slip through a crack in the space-time continuum; to lie not so much indifferent, as oblivious to the march of progress.

You see long rows of neat, clapboard houses, many with a US flag fluttering out front, and spruce little towns with names like Rockaway Beach, Seaside and Tilamook. After the experience of nighttime Portland, it’s like going to bed in a Hieronymus Bosch painting and waking up in one by Constable.

Should you have an emergency of some kind in rural Oregon, you can expect a swift response. In the metropolis of Baker City, with 10,000 residents, the police promise to be at

your door within seven minutes.

Over in Yamhill, in the heart of Oregon’s wine country, the local sheriff simply gets on his bike to investigate the odd Saturday night complaint about someone overdoing the Bacchic rites.

So, nowadays, it’s a lottery what might happen when an American householder summons the law.

In downtown Portland, the average response time to a 911 (or 999 equivalent) call ranges between 45-90 minutes. In New Orleans, officers take two and a half hours to attend a crime. That’s long enough for the perpetrator to take in dinner and a show in the French Quarter on his way out of town.

Over in Austin, Texas, meanwhile, a retired police officer named Robert Gross recently complained that he’d rung his former colleagues on the force ‘four or five times’ to report a dead body lying in his back garden. It eventually took them two days to respond.

‘I was surprised, but not shocked,’ Gross added of his experience of dialling 911. ‘It’s a shambles.’

Where I live in Seattle, 100 miles north of Portland, it’s all a question of priorities when it comes to an emergency response. One day last summer, trying to report a car break-in, I spent 40 minutes on hold, alternately listening to canned Mantovani music and a recorded announcement assuring me how vital my call.

The ‘detective’ who arrived on the scene 24 hours later displayed all the

befuddled style of Lt. Columbo, without any of that great sleuth’s forensic skill.

Set against this, the Seattle police chief has urged ‘anyone suffering or witnessing any form of racial harassment’ to call 911, and promises the ‘fastest possible response … Even if you’re not sure a hate crime is involved, call us immediately. We are here to help.’

More recently, I happened to pick up the phone to ring a publisher’s office in London to ask about the progress of a book I’d sent them.

Five minutes after I hung up, there was a thunderous knock at the front door. Two extremely large Seattle policemen walked in, an impressive variety of guns and other hardware on their hips, and demanded to know why I had just rung the nation’s designated emergency hotline.

It took some time for the penny to drop. The publisher’s number included the critical digits 911. Merely by dialling it, I’d triggered a police computer somewhere into dispatching a squad car to my home.

I felt like asking the officers why they thought an innocuous phone call to an office 5,000 miles away might take precedence over one reporting a burglary. But it was neither the time nor the place, I decided.

The men didn’t look like the sort of people who debate the vagaries of British STD codes, let alone the finer points of book production. So they thoroughly searched the premises. I thanked them for their time and watched them drive off to their next appointment.

Next time my car is broken into, I’ll call my publisher.

Satisfaction

Christopher Sandford is author of Keith Richards:

. Brought up in Britain, he now lives in Seattle

Portland is running out of cops – in Seattle, I can’t avoid them

22 The Oldie August 2023

Christopher Sandford

Two extremely large policemen walked in, an impressive variety of guns on their hips

Danger! Boring story alert

Have you ever found yourself telling the same excruciatingly dull anecdote twice? Oliver Pritchett has invented the ultimate cure

Do you find that when you are telling an anecdote to someone, you suddenly get the uneasy feeling you have told the same person the very same story before? Maybe several times?

It is one of the perils of getting older. You embark on an amusing reminiscence, lose confidence, falter –and then decide to plough on to the punchline. The trouble is, people are too polite to stop you in your tracks, even when you have begged them to say if they’ve heard it before.

The wonderful news is that I have developed an app that solves this problem. It is called Borenomore.

Its database holds hundreds of your best anecdotes. By means of sophisticated voice-recognition technology, each anecdote can be identified by a trigger word or phrase, such as my dear old granny or donkey’s years ago or my headmaster or complete fiasco – and of course a great mate, my first car, a prank, the war and rather a funny thing actually.

In a matter of seconds, the app can identify the anecdote that’s in the offing, run through all the contacts on your phone and highlight the names of those persons who were present when the anecdote was previously deployed.

An alert is then sounded. You can choose your default alert from a selection that includes a beep, a discreet cough or an audible yawn.

Sometimes, when you are halfway through some reminiscence, you realise

you have forgotten the point of it, the punchline, or the names of crucial characters in it.

No problem. Just touch the ‘abort anecdote’ button on the app and your phone will actually ring itself, so that it appears that you have been interrupted by a call.

You can also alter the settings on your app to suit the surroundings where your reminiscence is likely to occur. The default settings include ‘bar’ and ‘family occasion’ and ‘wedding speech’, ‘coffee morning’ and ‘reunion’. You can, of course, customise the app to suit other surroundings.

The deluxe version of Borenomore

has an additional function. If, in the course of a story you are telling, you happen to mention, for example, what you paid for a house or a meal in, say, 1957, this handy little device will immediately calculate the equivalent of that sum in today’s money.

The app is not quite ready to be downloaded yet. There are one or two snags that need fixing. I’ve been developing it with an old mate who was a contemporary of mine at school.

Actually, there’s a rather funny story about him…

CHRISTIE’S

/

The Oldie August 2023 23

Anecdotage: David Oyens’s De Stamtafel: Storytelling in a Café, 1879

IMAGES

BRIDGEMAN

Oliver Pritchett worked for the Sunday Telegraph for over 40 years

I have developed an app that solves this problem. It is called Borenomore

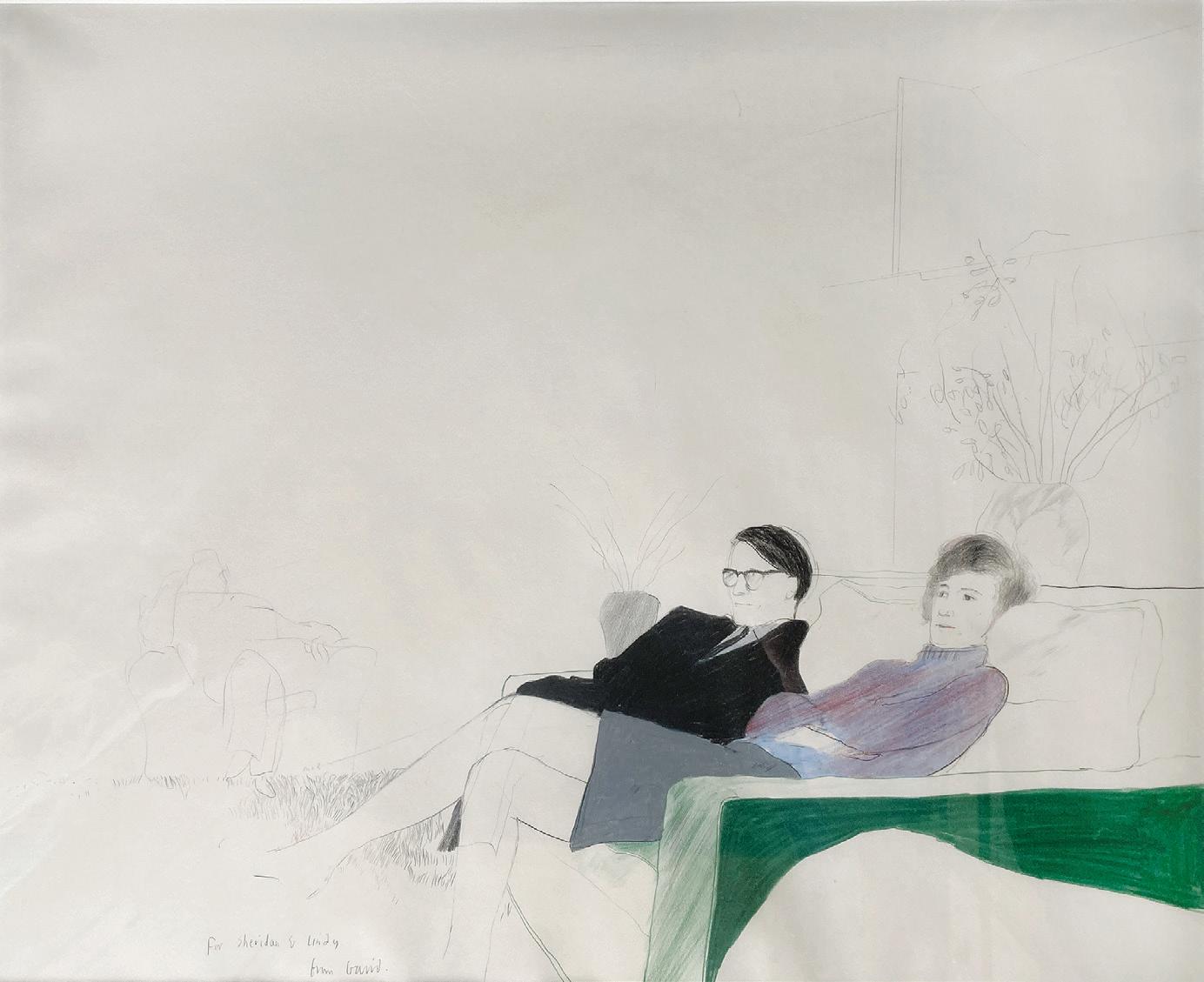

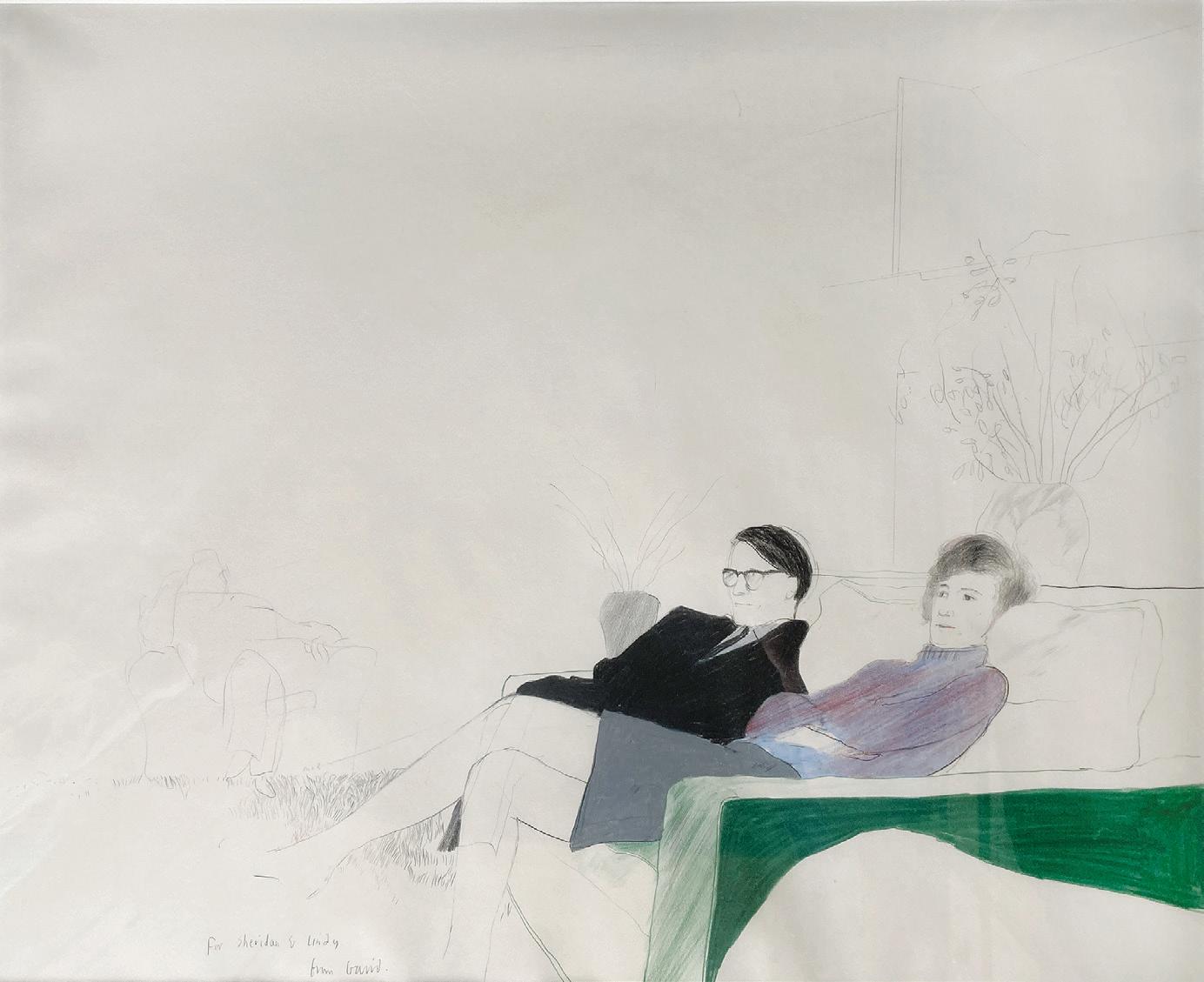

Lindy Dufferin was a painter, cow-breeder, yoghurt-manufacturer and chatelaine of a great Northern Irish house. By her godson Harry Mount

The Last Marchioness

It wasn’t hard getting people to write down their memories of my dear godmother, the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava (1941-2020), for a tribute book I’ve just edited.

Memories of Lindy Dufferin came thick and fast – and she always produced a different, striking reaction in people.

‘She had no neutral gear,’ said her friend Tom Stoppard.

‘She laughed. I miss her,’ said David Hockney – whose early pictures were dealt in the 1960s at London’s Kasmin Gallery, co-owned by Lindy’s late husband, the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (1938-88).

And the singer Van Morrison said of Lindy, his neighbour in County Down, ‘We’re both eccentric.’

Lindy packed several lifetimes of work – and fun – into her 79 years. She was a painter, conservationist, champion cow-breeder, yoghurt-manufacturer –and chatelaine of Clandeboye, an enchanting country house between Belfast and Bangor.

Painting under her maiden name, Lindy Guinness, she was taught by Oskar Kokoschka, Sir William Coldstream and her great mentor, Duncan Grant.

She often painted her champion Holstein and Jersey cows, whose milk is used for Clandeboye Estate Yoghurt.

Every one of the five million yoghurts sold has a Lindy painting on it. ‘That’s how I came to be the most famous disposable artist in the world,’ she joked.

Her furious activity extended beyond Clandeboye. In 2019, she had the idea of bringing sheep back to Hampstead Heath, inspired by Constable paintings showing cattle grazing on the Heath in the 1820s and 30s. Two Oxford Downs and three Norfolk Horns – rare breeds –were duly brought onto the Heath.

She felt that serious things could be achieved, even if – or especially if – you were enjoying yourself.

She wrote in her diary:

‘If there is laughter and joy, however serious the business at hand, you create

Lindy at Clandeboye, after winning the 2007 UK Premier Herd Competition. With Scott & John Robertson, Mark Logan & Clandeboye Gibson Jingle, champion cow Douglas, she hosted Camerata Ireland, the All Ireland Chamber Orchestra, as part of the Clandeboye Festival. It will be held at Clandeboye this August.

more than if it is too heavy-handed and serious. Fun is serious – it’s the best thing to have fun and to play makes one creative and one makes things that one had no idea were possible.’

When Sheridan Dufferin died, aged only 49, in 1988, he left her the Clandeboye estate.

It became, alongside her painting, her life’s work. She built several golf courses, opened the Ava Gallery and created a champion herd with her manager, Mark Logan (pictured). She set up a forest school in the Clandeboye woods for local children to learn about nature and created new gardens with her head gardener, Fergus Thompson.

With the great Belfast pianist Barry

By the time she died from cancer in 2020, Clandeboye was as busy as – if not busier than – in the glory days of her husband’s illustrious ancestor, the 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (18261902), Viceroy of India, Governor General of Canada and British Ambassador to France.

What a fairy godmother she was to me, too – extraordinarily generous when I was a child. Not just with presents but in boosting me with confidence as an achingly shy teenager.

A friend compared us to Babar the

26 The Oldie August 2023

Elephant and the old lady – and she was just as affectionate and gentle a companion to me all my grown-up life as Madame was to Babar.

In one of her obituaries, the Daily Mail made a sublime typo: they called her a ‘conversationist’ rather than a conservationist.

In fact, they were right: she was a conversationalist like nobody else (as well as a great conservationist).

She was extremely funny: a brilliantly skilled tease who could diagnose exactly what you thought and what you were like and, in an affectionate way, joke about your characteristics. I roared with laughter so often with her.

But, still, she took her duties extremely seriously – even if, at the same time, she could joke about them and observe their funny aspects.

She spent many evenings discussing the future of Clandeboye after her death. She was the last of the Dufferins – well, to be precise, she was the last Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava. The marquessate died out with Sheridan’s death in 1988. His cousin Francis Blackwood became Baron Dufferin and Clandeboye, succeeded by his son John Blackwood as the 11th Baron in 1991.

Lindy never showed off about the history of Clandeboye, the Dufferins or the important objects the family had gathered over the centuries. In fact, she knew that history inside out, despite being a questing modernist in her art.

She painted in ever more avant-garde styles, constantly experimenting. Tom Stoppard says, ‘I caught her at the best moment in her Cubist cow movement before she took it too far!’

Of that movement, Lindy said, ‘I am searching for the essence – or platonic form – of the cowishness of cows. They intrigue me.’

Peter Mandelson, who got to know Lindy when he was Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, loved the cow pictures:

‘I bought some paintings by Lindy but, to my eternal regret, I did not buy any paintings of her famous cows (no money).’

Lindy acknowledged in her diary that she’d been taught by so many greats that

Newly weds: Sheridan & Lindy Dufferin by David Hockney, London, 1964. Sheridan, co-owner of the Kasmin Gallery, was one of the first dealers to spot Hockney she had to fight to track down her own style: ‘I might have found my own voice – a sort of mixture of me and so many masters that I have studied and loved. How to use colour instead of line – that seems to be my quest.’

She and Sheridan collected modern pictures, and spotted modern artists such as Hockney, with a rare eye. But they both deeply appreciated the hallowed status of history and the past.

They added to and conserved their historical collections and knew and understood their significance – without displaying any pomposity.

Once, leafing through the books in the

Clandeboye library, I came across a book on Troy by Heinrich Schliemann, the German archaeologist who’d discovered the site of Troy in the 19th century. To my astonishment, there was a letter stuffed inside the book from Schliemann to the 1st Marquess, written in ancient Greek.

I rushed to Lindy, full of smug pride at finding the letter and my ability to read the Greek. She was interested from a historical point of view – but she never showed any of that distasteful pride herself in her considerable possessions and achievements.

With all her gifts in mind, I felt a book should be put together in Lindy’s honour. In part, it was to remember her painting, her mercurial nature and her gifts for sweet kindness and uniquely funny conversation.