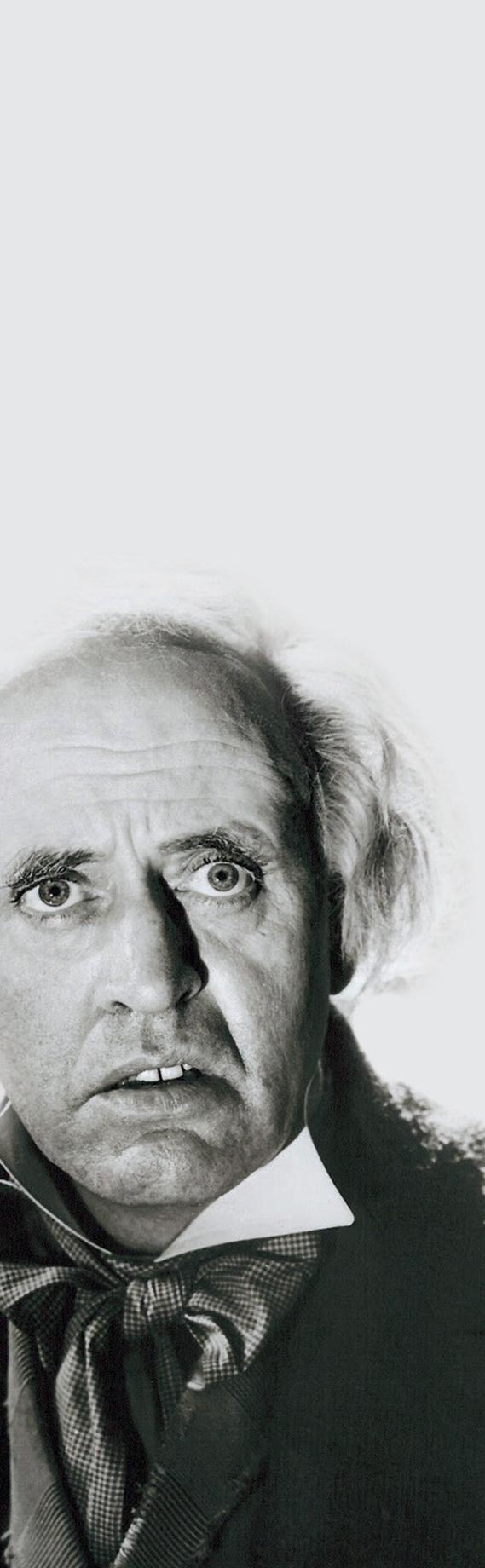

Michael Caine at 90

Best of

Best of

Regulars

12 Modern Life: What is main character syndrome? Richard Godwin 21 How to survive a sex scandal Sir Les Patterson 27 Mary Killen’s Fashion Tips 40 Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson 41 Country Mouse Giles Wood 42 Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny 43 Small World Jem Clarke 44 School Days Sophia Waugh 44 Quite Interesting Things about ... horses John Lloyd

46

46

47

48

50

50

63

63

9

64

10

12

Moray House, 23/31 Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk

66

55

57

59

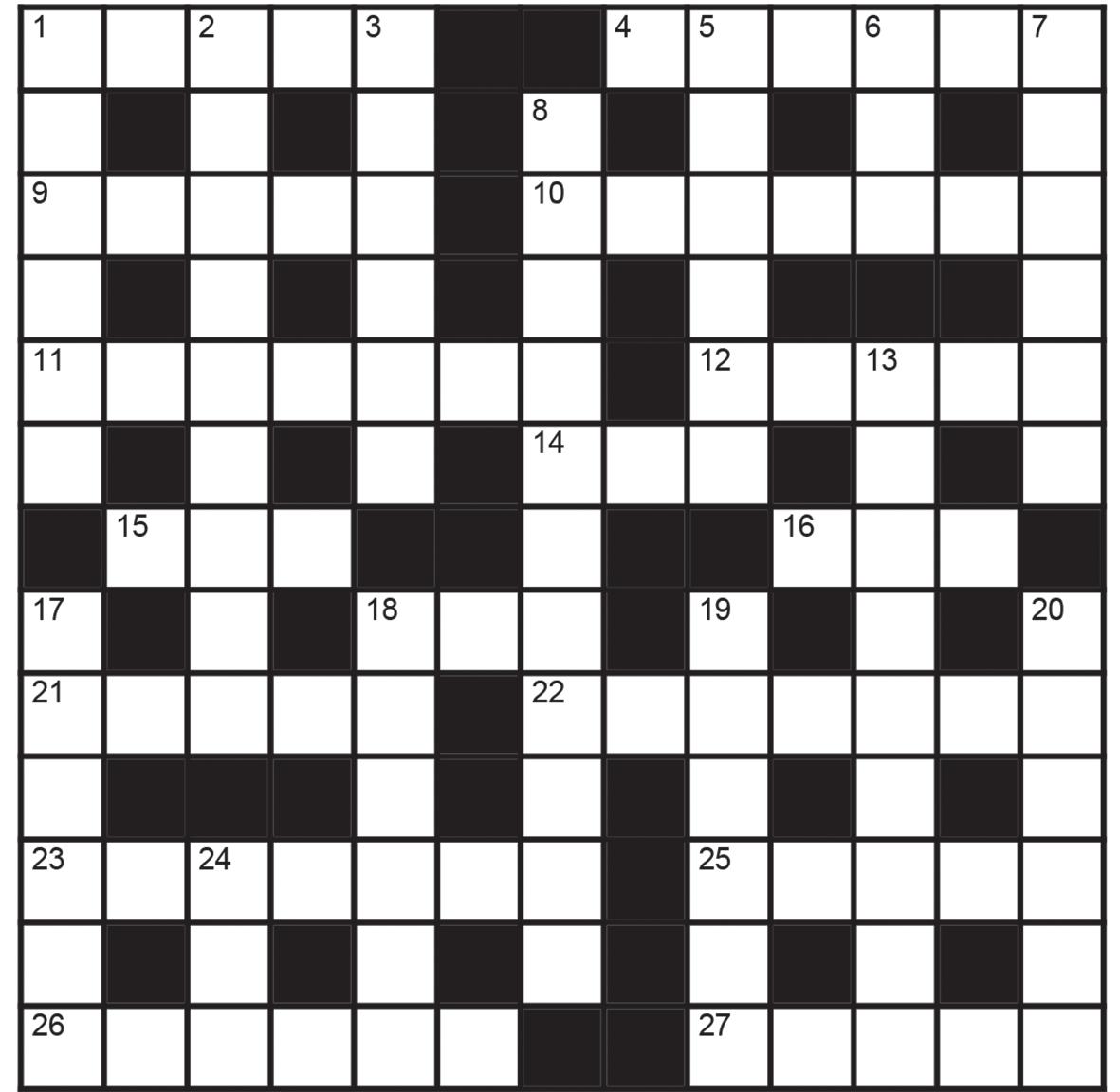

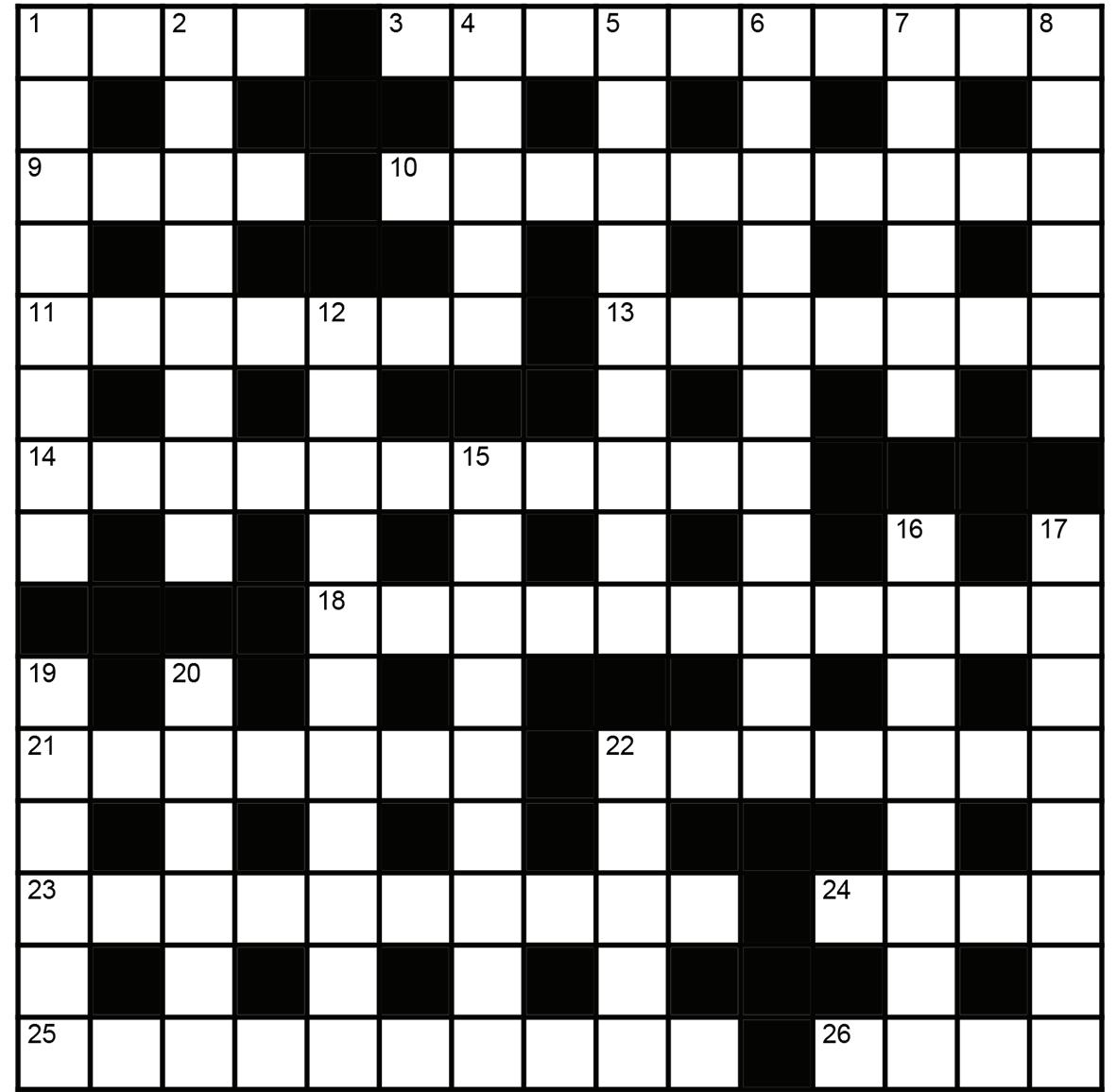

Crossword 91 Bridge Andrew Robson 91 Competition Tessa Castro

70

Golden Oldies Rachel Johnson 71 Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu

73

74

74

75

76

76

78

78

81

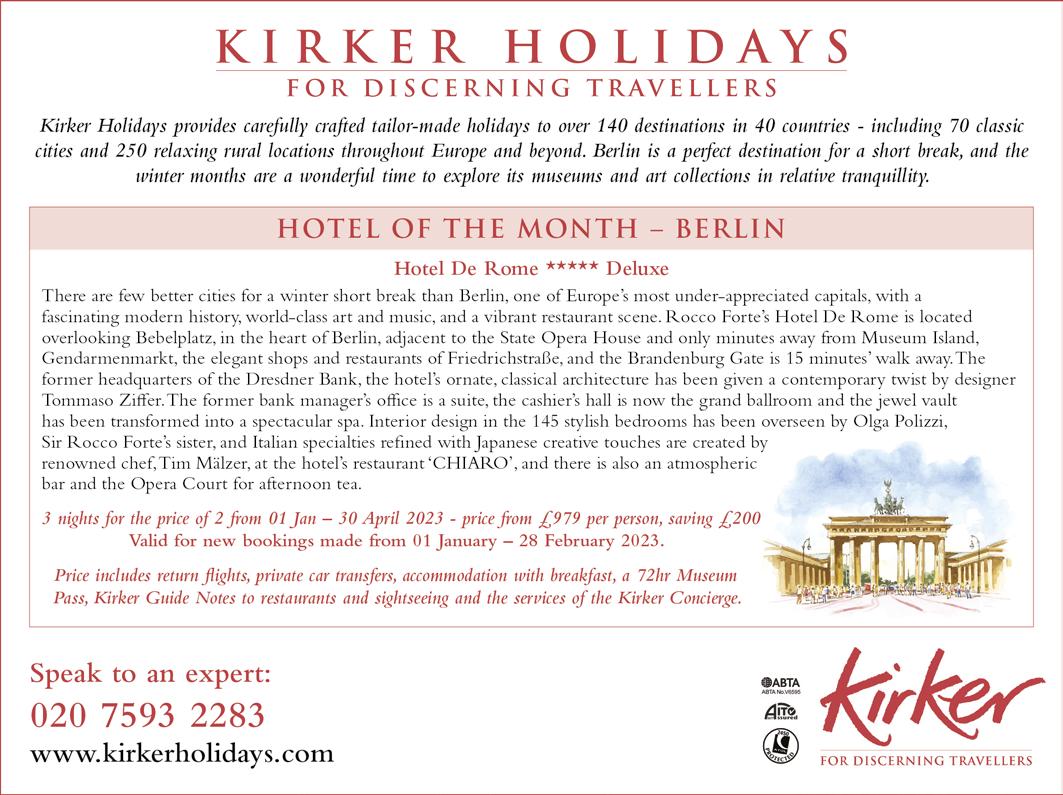

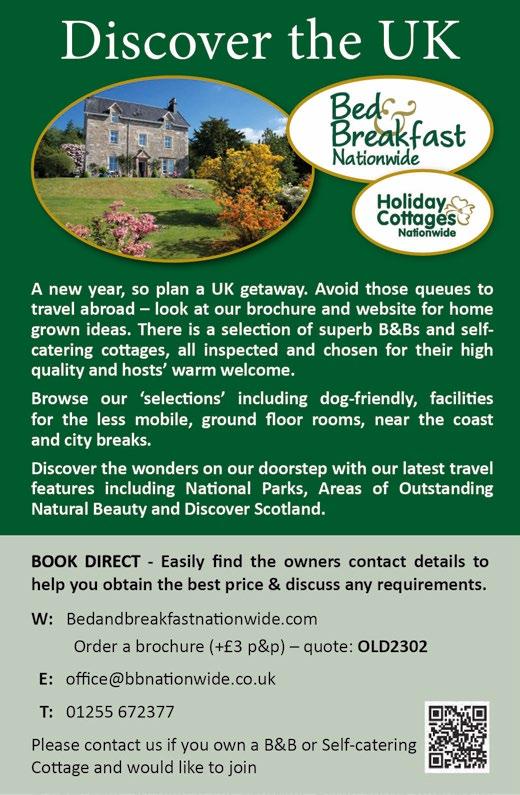

Travel

Overlooked Britain: Woburn Abbey and the flying duchess Lucinda Lambton

On the Road: Dolly Wells Louise Flind

Taking a Walk – by the North Sea Patrick Barkham

For display, contact: Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Rafe Thornhill on 020 3859 7093 For classified: Jasper Gibbons 020 3859 7096

News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

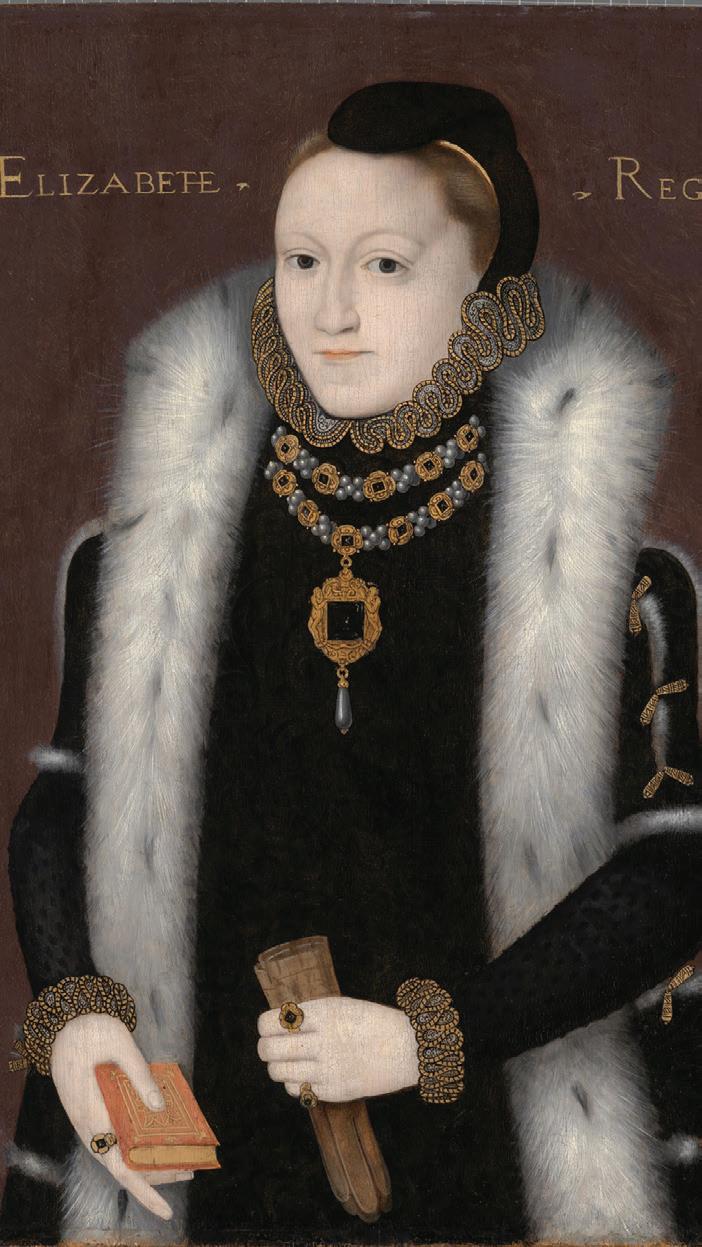

Front cover: Michael Caine by David Bailey, 1965

Just before Christmas, historian Lady Antonia Fraser composed a verse on confronting that age-old companion to faith –doubt – at Farm Street Church, Mayfair.

Whenever I doubt, I get out and about. To Farm Street I go –The journey is slow. I mutter and murmur, ‘My resolve should be firmer… Doubt? Kick it out.’

Then I flop down on my chair.

They put it specially there. So it’s solid and true, As I should be too. I pray throughout Mass. Doubt? Kick it out. Suddenly there’s a change Just within range.

The Host is held high Into the church sky. Peace is retrieved I believe…

Nick Downes is one of the most treasured cartoonists at Oldie Towers (see above right for an example).

The American cartoonist has been contributing to these pages ever since The Oldie was founded in 1992. Also prominent in the New Yorker, he is the cartooning heir to the great Charles Addams (1912-1988) – as in The Addams Family – in the gifted way he reveals the dark

Kenneth Cranham (p17) is one of our leading actors. He was in Oliver! and starred in Shine on Harvey Moon. On stage, he’s appeared in Loot, Entertaining Mr Sloane and An Inspector Calls.

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones (p18) is known as the Black Farmer. He farms on the Devon-Cornwall border. Born in Jamaica and brought up in Birmingham, he was a BBC producer of food and drink shows.

Amelia Butler-Gallie (p31) is a postgraduate at Lincoln College, Oxford. She is doing an MA in 18th-century literature. In this issue, she writes about the threat to Virgil and Homer at Oxford.

Elinor Goodman (p32) was political editor of Channel 4 News from 1988 to 2005. She is a regular presenter of The Week in Westminster and was a member of the Leveson Inquiry panel.

underbelly beneath everyday American life.

Nick has published a new book, Polly Wants a Lawyer: Cartoons of Murder, Mayhem & Criminal Mischief. Perfect for anyone with a macabre taste for the blackest humour.

Any oldies who are a little hard of hearing will be moved by Norman Lebrecht’s new book, Why Beethoven? A Phenomenon in 100 Pieces (Oneworld, £20), published in February.

The book includes a moving translation of Beethoven’s renowned Heiligenstadt Testament, written to his two brothers – Carl Caspar, a government clerk, and Nikolaus Johann, a pharmacist, who unfortunately prescribed accidentally harmful remedies for Beethoven’s ailments.

Beethoven wrote the testament in 1802, when he accepted he’d gone completely deaf after six years of increasing deafness.

He’d first spotted a shepherd, out in the fields, blowing on a wooden flute – and he couldn’t hear a thing. Then he went out for the evening in the vineyards of Heiligenstadt, on the fringes of Vienna. Around him, revellers chatted and drank new wine, clinking tankards, and Beethoven couldn’t hear any of it.

And so he wrote to his brothers, ‘I was compelled to isolate myself, to live life alone. I could not say to

‘I want to make you Mrs Psychotic Drifter!’Charles

Addams’s heir: a Downes cartoonfrom

his new bookDoubt by Antonia Fraser

Man

Call for new Welcome to Colne signs Burnley Express

Stunned detectorist finds hoard of old porn mags Sun

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The March issue is on sale on 8th February 2023.

GET THE OLDIE APP Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

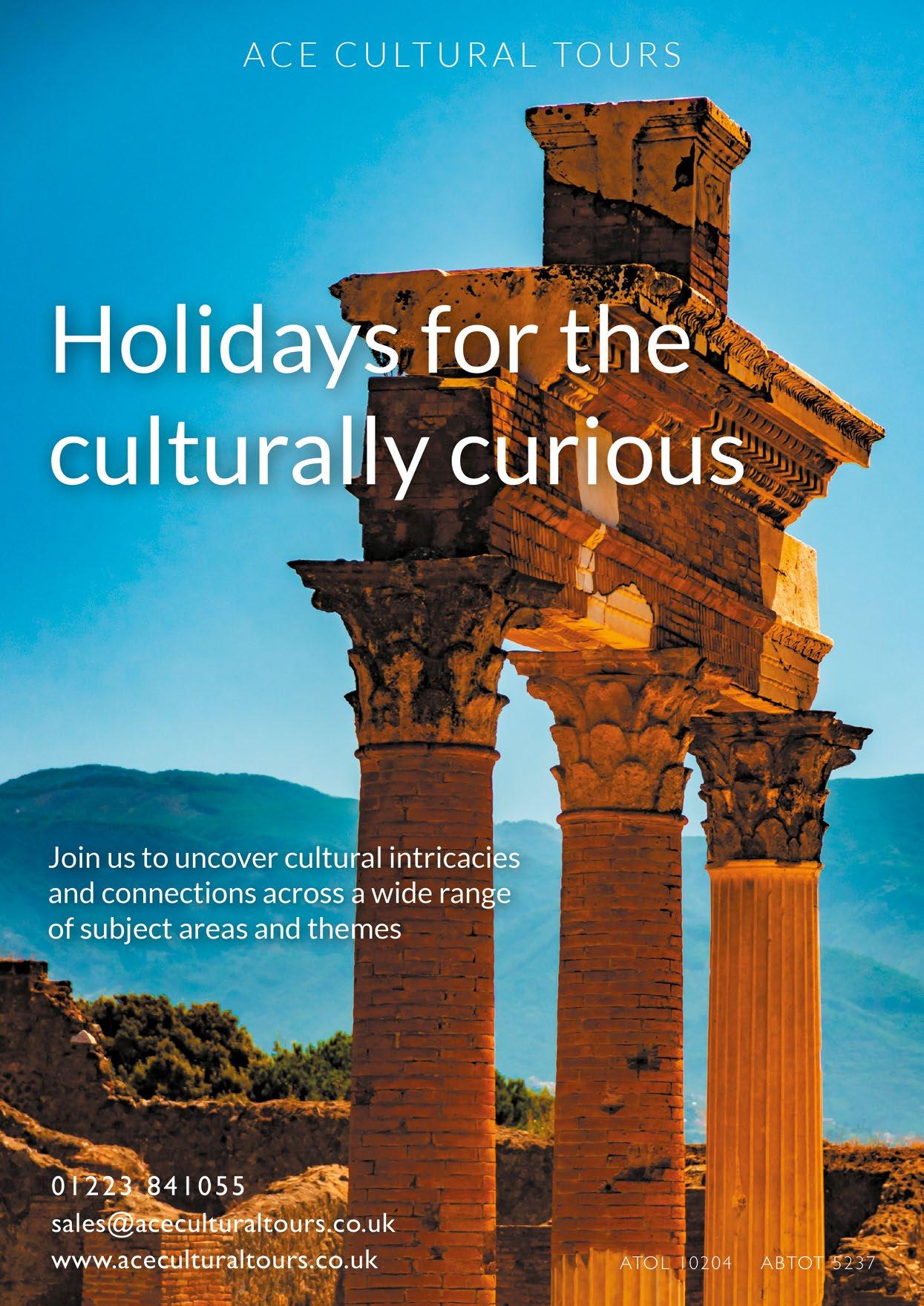

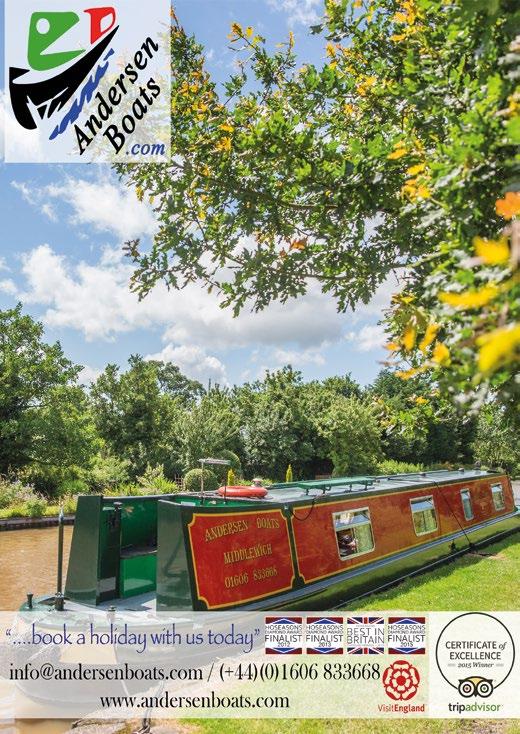

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

people, “Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.”

‘Ah, how could I admit an infirmity in the one sense that ought to be more perfect in me than in others, a sense I once possessed in the highest perfection, a perfection such as few in my profession have ever enjoyed.

‘Oh I cannot do it; therefore forgive me when you see me draw back when I would gladly have mingled with you.

‘For me, there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas. I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished.’

Poor Beethoven! Next time you’re tempted to irritation by an oldie who keeps saying, ‘What?’, remember the agony of the Heiligenstadt Testament.

Calling all oldie women artists!

The artist Posy Simmonds has drawn a brilliant cartoon (pictured below) to help promote Hosking Houses Trust.

The trust is inviting applications from women artists who would benefit from a residency (two weeks to two months) in a country cottage near Stratfordupon-Avon.

Since 2002, the Trust has offered residencies to older women writers. Over 160 writers have benefited from a period of peace for personal work without other duties.

Church Cottage is a one-up, one-down artisan cottage beside the churchyard in the village of Clifford Chambers, Warwickshire. In 2019, Arts Council England sponsored the building of a

small, light studio extension. The cottage is free and utility bills are paid.

Artists with a substantial body of successful work –particularly cartoons, illustrations, graphic novels, calligraphy or animation –are invited to apply (hoskinghouses.co.uk).

All applicants are advised, though, to keep an eye out for ‘something nasty in the woodshed’, as Stella Gibbons put it in Cold Comfort Farm (1933). Look closely at Posy’s picture to stay fully abreast of the perils.

One of the perks of the theatre critic is the occasional glass of free wine laid on by the theatres.

That’s what happened at the opening night of Hex, a musical at the National Theatre.

During the interval, the

Something nasty in the woodshed:

Church Cottage, Warwickshire, by Posy Simmonds

‘I hear you’re Australian…’

National laid on free wine for the drama critics, traditionally a not unthirsty crew. The Daily Mail’s Libby Purves, 72, was not in the mood for Château Screwtop – so she moved towards a large tray of free ice creams.

‘Hands off!’ she was told. ‘They’re for the children.’

Purves is a quiet soul and made nothing of it, but a couple of other critics were also shooed away from the tubs of vanilla and chocolate.

The New York Times International Edition’s Matt Wolf informed the National press officers they were displaying ‘ageism’. That did the trick. Modern officialdom lives in terror of being accused of an ‘ism’.

The central truth, though, is surely this: no one is ever too ancient for an ice.

James Gillray (17561815), the great caricaturist, is having a comeback!

First came Tim Clayton’s new book, James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire

In his biography of the ‘Prince of Caricatura’, Clayton followed Gillray from his first satires on the American War of Independence through to revolutionary France and the Napoleonic Wars, expertly skewering British politics and behaviour along the way.

And, in March, Alice Loxton, a 26-year-old historian, publishes Uproar! Satire, Scandal & Printmakers in Georgian London. She writes about Georgian Britain

through the illustrations of Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and Isaac Cruikshank.

Her particular themes are wild royals, political intrigue and the birth of modern celebrity – there’s nothing new under the sun!

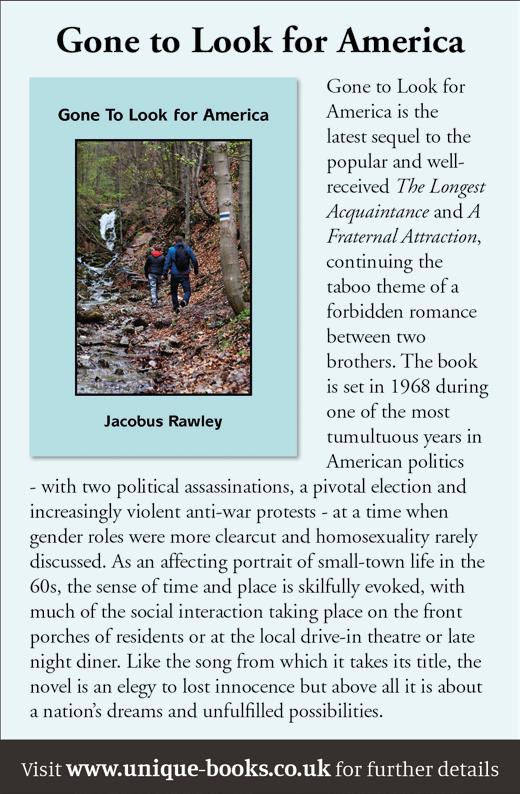

Slightly Foxed have reissued The Prince, the

Showgirl and Me, Colin Clark’s delightful memoir.

It tells of his time as third assistant director on The Prince and the Showgirl (1957), the film version, starring Laurence Olivier and Marilyn Monroe, of Terence Rattigan’s play The Sleeping Prince Colin Clark, Alan Clark’s

younger brother, captures Marilyn Monroe’s charm, vulnerability – and enchanting looks.

One day, he walked into her room, to find ‘MM, completely nude, with only a white towel round her head. I stopped dead. All I could see were beautiful white and pink curves. I must have gone as red as a beetroot… MM gave me the most innocent smile.

“Oh Colin,” she said. “And you an Old Etonian!” ’

The introduction to the new edition, by Derek Parker, also recalls Colin Clark’s later reminiscence, My Week with Marilyn (2000).

One morning, a car drew up, with Marilyn in the back seat under a blanket. ‘I don’t want to be Miss Monroe today,’ she said. ‘I just want to be me.’

So Colin set off in the car, cuddling up to Marilyn in the back seat. They went for a walk in Windsor Great Park, where they soon attracted a little crowd.

‘Shall I be her?’ Marilyn asked.

Colin continues, ‘Without waiting for an answer, she jumped up on a step and struck a pose. Her hip went out, her shoulders went back, her famous bosom was thrust forward. She pouted her lips and opened her eyes wide, and there suddenly was the image the whole world knew.’

Oh, how the Old Un wishes he’d been there, too!

‘Before we can make it o icial, we’ll need you to pee into this cup’

I hit it off with Sinéad Cusack – but she fell for the footballer instead

I have started the new year with a new hobby.

I am taking a weekly walk down memory lane – literally. My physiotherapist, Finola, is doing her best to improve my posture and balance in the hope that I fall over less in the future than I have in the past.

Part of her regimen requires me to take regular brisk walks. To add interest to my promenades, I have decided to revisit places I once knew well but haven’t been to in a while.

I started in Oakley Street, London SW3, where I lived with my parents as a little boy in the mid-1950s. It’s a wide, handsome street of Victorian terraced houses that runs from the King’s Road down to Cheyne Walk and the River Thames.

My father liked to say that everyone lives in Oakley Street at some point in their lives. Oscar Wilde and his mother lived there for a time. Scott of the Antarctic lived there with his mother. Bob Marley and David Bowie lived there in the 1970s (at different numbers).

When I first met him, the footballer George Best was living at number 87, the house where Oscar and Lady Wilde had once lived. Donald Maclean, the Cambridge spy, had lived at number 29, in the house next door to ours.

It must be 50 years since I last went into a house in Oakley Street.

In 1973, I visited number 15 to have lunch with Richard Goolden, a lovely old actor, whose claim to fame was playing the part of Mole in the original stage adaptation of The Wind in the Willows in 1929. He went on playing the part almost until he died, in 1981, aged 86.

Dickie Goolden was Mole: small, bent, gnome-like and completely delightful. Over lunch, he chattered away merrily about Kenneth Grahame (who wrote the book) and A A Milne (who wrote the play – he knew both of them) and about life in

the trenches during the First World War, when he was in charge of the latrines.

He scurried about the house – it was the family home, left to him by his mother. When I told him how much I liked our chicken soup, he ran off to the kitchen and returned triumphantly waving the empty Knorr soup packet at me.

After lunch, he took me into the kitchen and showed me his collection of empty Knorr soup packets – hundreds of them. He did not throw anything away. He took me upstairs to the top room in the house – bare floorboards with old suitcases and cardboard boxes all over the place – and showed me the shelves where he had kept every bank statement and chequebook stub he’d had since he first opened a bank account in 1914.

I am thinking of going to Ireland next, to walk the streets of Dublin, as I did one night in 1970 after a romantic disappointment.

I was in Dublin, aged 22, to be a guest on The Late Late Show hosted by the late great Gay Byrne (1934-2019), then the most famous man in Ireland – by a margin.

His show was huge, and he was more famous than the Pope. Truly.

I remember him as leprechaun-like,

very charming and quite unspoilt by his incredible success. For me, though, the excitement of the night was not appearing on Ireland’s most popular TV show. It was meeting the actress Sinéad Cusack at the star-studded post-show party.

Sinéad and I became immediate friends – and found we had been born barely two weeks apart.

We exchanged jokes, theatre stories and our phone numbers within minutes and talked simultaneously, nose to nose, non-stop. Our hands kept touching.

I was bowled over by her. And she liked me. I know she did. For an hour or so, we had a really lovely time together – and then…

And then I introduced her to George Best! Why did I do it? She told me she wasn’t interested in football. I believed her.

George was a fine footballer, of course, but he wasn’t Pelé or Maradona, let alone Messi or Mbappé.

He wasn’t articulate or funny, and he wasn’t that good-looking either. He was rather awkward and scruffy, in fact. But Sinéad said goodnight to me and she went off with him. And, alone, I walked the streets of Dublin.

Sinéad will be 75 at the end of February. I will be 75 at the beginning of March.

Between our birthdays, my friend Sheila Hancock turns 90. She is a wise and funny lady who has been getting some stick in the press for talking up the value of the old-fashioned stiff upper lip.

I am with Sheila all the way. Let’s have more resilience and less bleating and blubbing and letting it all hang out. Keep your woes to yourself. Sinéad fancied George Best. She married Jeremy Irons. Get over it.

Gyles celebrates his 75th birthday with Judi Dench, Sheila Hancock and friends at the London Palladium, 5th March. In aid of Great Ormond Street Hospital

matthew norman

matthew norman

This time, it struck me at 4.30am – the halfway mark of a refreshing five-hour sojourn in A&E – I truly mean it.

Admittedly, I’d been equally convinced that I meant it on three vaguely similar occasions in the last couple of years. The ultrasound on the testicular lump (epididymal cyst). The ECG to investigate cardiac arrhythmia (nothing lethal). The gastroscope after years of acid reflux (tiny duodenal polyp).

Each time, I believed I meant it when, while striking the cowardly atheist’s classic deal with God, I swore to the deity in whom I unbelieve that, if I could dodge the bullet, a radical metamorphosis would ensue.

This time, however, I really, really meant it.

The development that took me to the Royal Free, in the smug liberal leftie Shangri-La of Hampstead, was of a type that appeals to the professional hypochondriac more in the abstract, as described on a newspaper’s health page, than in the personal and particular.

Much as I’d like to euphemise, for the squeamish and those struggling to plough through this nonsense over their breakfast egg, I will simply repeat what I told a delightful Portuguese triage nurse in that miraculously empty department.

When I was asked what had enticed me to pay a visit on that picturesque, snowy early morn, the unwonted succinctness was dictated by the intensity of the pain radiating across the entire region between navel and upper thigh.

‘Can’t pee,’ I muttered, so sotto voce he wasn’t sure what he’d heard.

‘Sorry, are you saying you cannot go to the toilet?’ he followed up.

‘I’m saying no such thing,’ I said, relocating the gift for irksome loquacity. ‘I most certainly can go to the toilet. I have been to the toilet 30 or 40 times since midnight. What I cannot do, on reaching the toilet, is pee.’

‘Nothing?’

‘Not a f****** droplet.’

Sudden-onset urinary retention is not one of those symptoms that permit you to live in denial for long. A dodgylooking mole you can ignore for months. Blood on the Andrex can for a good while be ascribed, with fingers crossed, to piles.

But the total inability to urinate, apart from the indescribable mental anguish, is a bona fide medical emergency. It can lead, if not promptly treated, to renal failure, sepsis and death.

‘Are you in pain?’ asked an equally delightful staff nurse from Rome, as he attached a saline drip to the cannula. Plainly, this was neither the time nor the place for sledgehammer irony.

‘Never felt better,’ I responded. ‘If the roads weren’t so icy, I’d be off for a run.’

He smiled wearily, took some blood and went off to order an analgesic suppository.

A quiet A&E department in the middle of the night, with its weirdly seductive, harsh lighting and eerily serene atmosphere, lends itself beautifully to reflection on one’s own depthless inadequacies.

Obviously, in any such circs, the hypochondriac assumes it to be metastatic cancer, the primary tumour grown large enough to obstruct the urethra.

But, if not, should the cause be benign and treatable, it would be utterly shameful not to use the reprieve as the catalyst for reform.

In the CT scanner, the pledge was duly made. Let me off, Lord of whose non-existence I’m unshakably convinced, and to thee I vouchsafe to cut out the lashings of whisky and mounds of junk food; to redirect the untold hours in front of the telly to reading books; even to writing the sort of barely mediocre novel of which I might at best be capable.

‘Do you have the results?’ I asked the Portuguese when he ambled over to check the saline drip. He nodded. ‘It’s cancer, then? Kidney, bladder, prostate? All of them?’

‘It’s a kidney stone.’

‘Cancer and a kidney stone?’

‘Just a kidney stone.’

‘No cancer then?’

‘No.’

‘Can I kiss you?’

‘I’d rather not.’

I offered a fist bump. He graciously accepted.

A doctor confirmed this, and by 7.30 I was back at my mother’s house, where I’ve lately been in residence. I took her coffee and a buttered half-bagel, almost relishing the revived agony for the reminder of what it wasn’t.

Never one to centre-stage, she took the news stoically. ‘This is terrible,’ she said, adroitly side-stepping the triviality of the diagnosis. ‘I will never get over the shock.’

‘Of course you will,’ I reassured her. ‘All things pass. Even, eventually, this sodding stone.’

‘They say the pain’s every bit as bad as childbirth,’ she helpfully advised. ‘If not worse.’

I informed her of the epiphany; of how, from that moment on, I would cease squandering time in front of the telly, and begin looking after both body and mind.

‘Oh yes,’ she said, pursing lips. ‘Of course you will.’

The morning passed as pleasantly as the scrotal and abdominal excruciations would allow, in front of ITV, until I fetched us both quadruple Scotches and opened negotiations about lunch.

Several plant-based options were proposed, and jointly rejected. ‘McDonald’s?’ she proffered.

‘McDonald’s it is.’

After years of false alarms, my trip to A&E was a real emergency

The phrase Noblesse Oblige first appears in a Balzac novel, Le Lys dans la Vallée (1836). An elderly aristocrat tries to sum up for a younger friend how to live.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as ‘Noble ancestry constrains to honourable behaviour; privilege entails responsibilities.’

Why is the concept originally French?

It’s related to the idea of chivalry, the word itself deriving from the French word for horseman, chevalier (from the lateLatin caballarius). This word doubled as a term for a member of a higher social class, as it did with the Greeks and Romans.

The code of chivalry, familiar to us from Arthur’s knights and Pre-Raphaelite paintings, dated from the end of the 12th century, but was never codified. It derived from the medieval Christian institution of knighthood and was popularised in medieval literature.

The code of chivalry originated in the Holy Roman Empire, deriving from the idealisation of the cavalryman, especially

in Francia, where Charlemagne’s horse soldiers were such a potent force. By the late Middle Ages, chivalry had become a moral system that combined knightly piety, warrior ethos and courtly manners. This created the sense of honour and nobility that underlines Balzac’s famous phrase.

Dr Johnson saw as a source of nobility Aristotle’s notion of ‘the great-hearted man’, whose magnanimity embraced generosity of spirit as well as valour. As early as the Iliad, Homer’s Sarpedon understood the concept, telling Glaucus they enjoy royal privileges because they lead by example in battle.

Alexander the Great lived by this principle and his troops loved him for it. The Roman aristocrat Regulus endured a lingering death rather than break an oath he had given to his Carthaginian captors.

Modern democracies have understandable difficulty with the concept of nobility, preferring to admire it from afar in plays or historical novels.

Remember Burke’s words to the House of Commons on the death of Marie Antoinette: ‘I had thought ten

thousand swords would have leaped from their scabbards. But the age of chivalry is dead, and that of sophisters, calculators and economists is upon us.’

Still, the men who went out to govern the British Empire continued to read the Greeks and Romans at school. Few would have admired the selfish morality of Achilles or his Roman counterpart Coriolanus. Cicero’s advice to a future governor may have been preferred: ‘The first duty of a governor is to ensure the happiness of the governed.’

Modern aristocrats have not always behaved well. None of Stephen Ward’s grand clients would testify for him at his 1963 trial during the Profumo affair.

But the public schools of today still believe in doing service to those less fortunate and in making pupils aware that ‘privilege entails responsibilities’ – a memory of Noblesse Oblige.

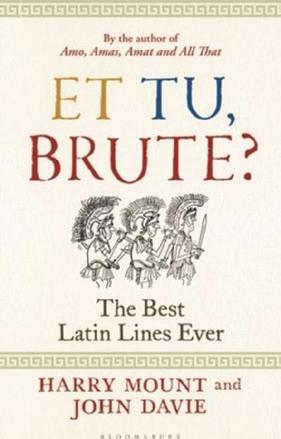

John DavieJohn Davie was head of classics at St Paul’s School, London, and a lecturer at Trinity College, Oxford. He is co-author of Et Tu, Brute? The Best Latin Lines Ever

Main character syndrome is when you find yourself behaving like the protagonist of some kooky Hollywood romcom. Or maybe it’s a French arthouse movie for you, a Taylor Swift video, or a novel by John Le Carré.

You imagine all the world is your stage and everyone you interact with is a supporting player. Not a medically recognised condition, it’s a way of investing each mundane interaction with cinematic grandeur and novelistic significance.

The term gained currency on pandemic-era TikTok, when millions of bored teenagers started uploading parodic videos, gently ironising their own humdrum lockdown routines. Some are funny deconstructions of common

Hollywood tropes – the montage of the romcom heroine returning to her home town, for example.

Main character syndrome isn’t confined to TikTok. It is a widespread instinct in our self-conscious, mediasaturated age.

And it goes back a long way. Duffy, the sad bank clerk in James Joyce’s story A Painful Case (1914), seems to suffer from it: ‘He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense.’

I remember my English teacher declaring this to be the behaviour of a ‘loon’ and my girlfriend and me turning to each other to say, ‘But we do that all the time!’

Vladimir Nabokov was alert to the syndrome, too. The unhappy hero of his story Signs and

Don Quixote: daydream believerSymbols (1948) suffers from a condition called ‘referential mania,’ whereby ‘the patient imagines that everything happening around him is a veiled reference to his personality and existence’.

The archetype is Miguel de Cervantes’s 17th-century hero Don Quixote, who has read so many romances about knights in shining armour that he imagines himself to be one. Keith Waterhouse reinvents the form in Billy Liar (1959).

It isn’t easy having main character syndrome. ‘No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast,’ Duffy muses in A Painful Case – another of those third-person past-tense sentences of his.

But there is also something rather consoling about it too. Are we not, after all, the main characters in our own lives? Is life not rendered all the more meaningful by our noticing all the little signs and symbols?

Walk around your town, pretending to be a film star – and tell me it isn’t an improvement.

Richard Godwinwhat is main character syndrome?

what was Noblesse Oblige?

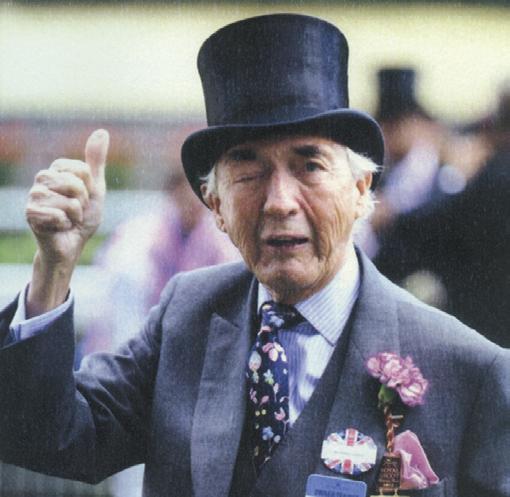

As the great actor turns 90, Andrew Roberts salutes his long apprenticeship in forgotten B movies

Sixty-five years ago, many cinemagoers wanted to avoid the supporting feature for the Danny Kaye vehicle Merry Andrew.

That supporting feature – Blind Spot (1958) – was standard B-film fare, with scenery costing approximately 5/6d. The only redeeming element was the lastminute revelation of the villain, nicely underplayed by a tall, fair-haired actor billed 13th in the opening credits.

It was the great Michael Caine, who will turn 90 on 14th March.

‘Michael Caine-spotting’ is a pastime familiar to those of us who appreciate British cinema of the 1950s and early 60s.

Caine did national service between 1952 and 1954, seeing active service in Korea. After he’d left the army, it was a long, hard slog before he hit the big time.

Before the release of Zulu in January 1964, he appeared in 16 films. In 1958 alone, Caine made six brief appearances, including as a Gestapo officer confronting Jack Hawkins in The Two-Headed Spy. A year later, he was a squaddie in a cinema commercial promoting Watney’s Ale.

Caine memorably describes this treadmill of bit-parts and temporary jobs in his autobiography The Elephant to Hollywood

His one prominent cinema role of this era was as an inarticulate Irish labourer in the 1957 comedy How to Murder a Rich Uncle. Unfortunately, playing Gilrony required little more of him than looking woebegone and saying ‘Aye’ in a very strange accent.

Otherwise, he was making minor

appearances, including as a matelot at the beginning of Sailor Beware (1956) – Paul Eddington was a shipmate – and again in The Bulldog Breed (1960), helping to rescue Norman Wisdom from Oliver Reed’s Teddy Boy gang.

Towards the end of the 1950s, there appeared to be a glimmer of hope of big roles – with the possibility of Caine’s joining Associate British Picture Corporation’s stable of contract artistes. But the casting director Robert Lennard told him, ‘I know this business well and believe me, Michael, you have no future in it.’

Caine was far from alone in having his talents ignored by British cinema. Peter Sellers was 30 when he starred in The Ladykillers (1955), and Ian Hendry didn’t achieve a major film role until he was 31.

Meanwhile, in 1961, the 28-year-old Caine cameoed as a police constable in the science-fiction drama The Day the Earth Caught Fire – ‘and I didn’t even manage that very well’.

Still, Caine’s stage and television CVs were expanding. He is one of the last prominent British film actors to emerge from provincial ‘rep’, starting his career in 1953 at Horsham under the name Michael Scott. The West Sussex County Times praised how ‘Mr Scott switches alarmingly from quiet charm to maniacal frenzy’ in the play Love From a Stranger (based on Agatha Christie’s short story Philomel Cottage). Another critic noted how the performance attracted ‘an idolising bevy of high-school beauty’ in the audience.

Shortly afterwards, the former Maurice Micklewhite adopted the

professional identity of Michael Caine, inspired by The Caine Mutiny (1954).

Over the next few years, he would appear at Stratford East and in Birmingham in The Long and the Short and the Tall as Private Bamforth, alongside fellow cast member Terence Stamp.

Television increasingly augmented Caine’s stage work, including a part as a Swiss prisoner in The Adventures of William Tell, wearing what looked like a tea cosy. His small screen roles gradually improved, and in 1961 he co-starred with Frank Finlay as a mentally disturbed occupant of The Compartment, a duologue written by Johnny Speight.

The Stage applauded Caine’s ‘fascinating performance’, which is ‘missing, believed wiped’. The year 1961 saw him cast as the splendidly named Ray the Raver for Granada’s The Younger Generation series of dramas.

In 1962, Caine appeared as an escaped mental-hospital inmate in Speight’s The Playmates and told a reporter, ‘That’s the end of Cockney nutty parts on TV for me.’

Towards the end of the year, Caine starred as Willie Mossop in an ITV adaptation of Hobson’s Choice. But the best cinema could offer him was a gangster role in Solo for Sparrow, one of

the Edgar Wallace Mysteries B-film series. The conclusion of this epic involves a low-budget gun battle, the arrival of a police Wolseley and a surprise guest appearance from a chicken.

Then 1963 proved Caine’s breakthrough year, with his West End debut in Next Time I’ll Sing to You and the title role in the BBC play The Way with Reggie. Dennis Potter regarded his performance as the ambitious docker as ‘beautiful’.

Although the Daily Telegraph’s reviewer was less keen, he referred to Caine as a ‘bright young actor’.

When Edna O’Brien interviewed him for the Evening Standard, he informed her that in Zulu ‘I play an aristocrat and I am proud of that. It means I’m not just a Cockney with a capital “C”.’

The days of uttering trite dialogue in second features now belonged to the past. Yet those cinemagoers who avoided Blind Spot missed an opportunity to see a star in the making.

Johnny Brent anticipated the insouciant charm of Harry Palmer in The Ipcress File (1965) and Lt Gonville Bromhead’s dulcet tones in Zulu. Caine modelled the slow speed of his accent on the Duke of Edinburgh. He’d noticed that grand people speak slowly because they know their audience will listen to them; while the less grand had to speak quickly before someone interrupted them.

And only an actor of Caine’s skill could make the threat ‘You haven’t been rash enough to inform the police, I hope’ and a getaway car that changes from a Vauxhall Victor to a pre-war Hillman remotely believable.

He is one of the last prominent British film actors to emerge from provincial rep

When Kenneth Cranham performs Rudyard Kipling, he thinks of the late Josephine Hart, the writer and poetic pioneer

In February, I’ll be performing a selection of poems by Rudyard Kipling, Wilfred Owen and Robert Lowell and I’ll read prose by J B Priestley. The show explores the poignant experience of human beings in war.

The first third of the show will be Kipling. His poems take me back to Bill Gaskill (1930-2018), the theatre director at the National Theatre and the Royal Court. I was in eight plays directed by Bill, including a part as Len in Saved by Edward Bond at the Royal Court.

The last production Bill directed was his own funeral service. For his list of chosen readings, he wrote, ‘Kenneth Cranham – Kipling’.

He didn’t say which one. So I chose Kipling’s When Earth’s Last Picture Is Painted, with the lines:

When Earth’s last picture is painted and the tubes are twisted and dried, When the oldest colours have faded, and the youngest critic has died, We shall rest, and, faith, we shall need it...

I chose those words because Bill once tried to ban critics from his productions!

I also performed Mandalay, with its stirring refrain:

On the road to Mandalay, Where the flyin’-fishes play, An’ the dawn comes up like thunder outer China ’crost the Bay!

The poems go up to the recent past, in the shape of the American poet Robert Lowell (1917-77) and his poem on the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, in 1968, Women, Children, Babies, Cows, Cats:

We was to burn and kill, then there’d be nothing standing women, children, cows, cats.

Looking back, I can remember doing a series of poetry performances. I shared a stage with Christopher Logue at the National Theatre, performing his poems about London. I did a selection of Samuel Beckett at the National with Peggy Ashcroft.

For a Christmas service at Westminster Abbey, I recited a text

about Joseph and Mary seeking sanctuary in the dark of night. I read a three-word phrase, describing their plight: ‘Far from home’. Simple words – great power. The boys’ choir really did sound like a choir of angels.

I read, too, for the late Josephine Hart (1942-2011), the author of Damage, a pioneer of poetry performances and the wife of Maurice Saatchi.

Josephine thought that ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’ was the first line of pure poetry she’d ever heard, as a little girl in Ireland.

As Randy Newman writes in his song Kathleen (Catholicism Made Easier), ‘I’ve always been crazy about Irish girls.’

In the February show, my daughter, Kathleen Cranham, will perform poems found by Josephine, the great huntressgatherer of poetry: Train by Helen Mackay; Perhaps by Vera Brittain; Paris, November 11, 1918 by May Wedderburn Cannan.

When I first read about Josephine, the dynamic, brilliant writer and promoter of performed poetry, I wanted to be one of her gang. Knowing she loved Elvis, as I do, I hand-decorated an Elvis cassette and sent it to her. Elvis worked his magic.

She asked me to perform Kipling at an evening at the British Library – a role previously performed by Roger Moore.

I emulated Roger’s favourite party piece, Kipling’s The Mary Gloster, a 16-minute storm of words from a dying father to his son:

Harrer an’ Trinity College! I ought to ha’ sent you to sea –

But I stood you an education, an’ what have you done for me?

The start of the reading was delayed because Margaret Thatcher was due to arrive – she was now retired and suffering from dementia but remained a Kipling fan. The hall at Downing Street during her time there was dominated by a large painting of Kipling, sitting at his writing desk in profile.

Margaret Thatcher’s favourite poem was If. I’d been given the task of performing it, including the lines:

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them, ‘Hold on!’

John Major was also in the audience. His parents had been in music hall – a key element in Kipling.

Thanks to Josephine, I read in the Josephine Hart Poetry Hour at the Donmar Theatre in 2011. She put together a compilation of First World War poetry, writing what she called ‘introductions’ to groups of poems.

That triumphant week, she’d been battling cancer and had to be replaced by the actress Deborah Findlay. On the afternoon of the show, 2nd June 2011, it was announced that Josephine had died.

Her charming, witty, perceptive introductions were beautifully read by Deborah. Our hearts wept for Maurice. The audience and we readers were blind with tears.

One of my poems was To Any Dead Officer by Siegfried Sassoon, with the lines:

I’m blind with tears, Staring into the dark. Cheero!

The Soldier, performed by Kenneth Cranham, is at the Marylebone Theatre, London, on 5th February

Getting the 5.52am train from Exeter St David’s to Paddington is not a journey for the faint-hearted. But I believe face-to-face meetings are essential to build and maintain relationships in our business and personal lives.

It is an expensive trip at this time of the morning and a long way to go for a one-hour meeting. Still, my belief is that the old-fashioned way of doing things outstrips the convenience of the modern age.

‘Why not send an email or have a Teams or Zoom meeting?’ my younger colleagues are always asking.

I organise trips up-country myself from my farm on the Devon-Cornwall border, and I do so as if I were getting ready for a date. I confirm, confirm again, and ring ahead so I can hear from a person’s lips that the meeting will be going ahead.

I got one of my bright, young, university-educated interns to organise this particular trip. As I journey onwards from Paddington to Holborn, it is as if I have landed on another planet. Almost everyone is glued to their phone, oblivious to the world around them.

I am relieved to reach the sanctuary of my destination and the office reception area, and I give praise that I can escape those humanoids controlled by their screens.

‘He is not in.’ The reply pulls me up short. But I have a 9am appointment with him. ‘Sorry, but he has been on holiday for the past week and he will not be back for another four days.’

I ring my intern to ask if the meeting has been confirmed. Frustration bubbles up to explosive levels when I’m told the damning words, ‘Well … I sent an email.’

Since the start of the digital revolution, I have been in a losing battle with young people. I try to get them to understand that, rather than expecting

things to get done by sending an email, they must pick up the phone and speak to people.

The new form of business communication is via WhatsApp messaging and emails. Everything is text-based. This technology has speeded up communication. But it is breeding a generation of young people who are terrified of picking up the phone and speaking to a human being.

Although the mobile phone was first invented so that people could talk to one another more easily, mobile speaking devices are now mobile texting devices. Calling and leaving voice messages is almost extinct.

Technology has given us the gift of speed and convenience but, in the process, it has begun to strip us of our ability to connect – and connection is what is vital to the human soul.

We live in an age when people are desperate for human connection but, because they are so glued to their phones and computers, they are losing the vital skills that enable them to forge such a bond.

It is only when we talk to someone that we are able to build a clearer picture of what they are truly saying and, importantly, meaning. That contact gives us a glimpse into a person’s personality. We can hear the complexity that makes up their character.

Messaging is transactional unless you have the gift of poetry. Something

said in a text can have a completely different meaning from the same thing said on the phone or in person.

For some time now, having seen the growing trend to communicate with people only via text or email, I have been running my own private campaign to try to save people from themselves.

In my company, The Black Farmer, no matter your rank, everyone has to do their turn on customer service – and that means picking up the phone and speaking to someone.

Obviously this intern didn’t get the memo. Perhaps I should have emailed. I see every day how this customer-service approach pays dividends, as most people are so grateful that we bother to phone them.

I fear this problem of a younger generation, uneducated in how to connect with people, means that those of us who grew up navigating human interaction at every turn will be called upon in our older years to pass on those skills.

Companies that thought it wise to manage people of a certain age out of their business will soon realise they have a human-resources problem: a young workforce that has evolved to become so like the machines they worship that they have forgotten that most human art of connection.

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones is a farmer and founder of The Black Farmer food range

Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones, the Black Farmer, has to teach his young employees to pick up the phone and talk directly to people

olest me, Les. Molest me in my workplace, you dirty old devil!’

The replay on the CCTV screen froze on a shot of my bum. The boardroom at Oz House was as full as a pommy complaints box – with Australian dignitaries, all old mates, shitting themselves. Otherwise, the boardroom was very quiet.

On the screen, I recognised Chantelle Pugh, one of my nubile PAs and a trusted member of Team Patterson. I looked around the room. There was the picture of Betty Windsor on the wall; some bastard had forgotten to replace it with Charlie.

Naturally, on the evidence of the hidden CCTV camera, my politico colleagues were a bit concerned that their own extra-curricular activities were similarly under electronic scrutiny. Most, if not all, research assistants in the office had had more than one distinguished visitor in her workplace – or, in the case of Bronwyn Cheknik, workplaces.

The reason for all this snooping is that the Labour Government wants the electorate to believe it’s cracking down on political immorality in high places – and every happily married man knows where those high places are located. Are you with me? So I was the sacrificial kangaroo. I was Patterson the patsy.

But I only got rapped over the knuckles because I know where too many bodies are buried. The PM was a nice bloke, and I’d helped him out of a few tight corners, some of which were very tight indeed. With me?

My colleagues were pretty understanding as well about my peccadillo (more pecker than dildo), considering most of them were fully paid-up scallywags themselves.

A few Labour PMs ago, I really did our bloke a favour.

Prior to that, I’d given him a sweetener: a lovely vintage Persian rug and an original Renaissance artwork of a Chow sheila with a green face on velvet, both from Kuala Lumpur.

I was trying, on behalf of a developer mate, to get demolition permission to bowl over some ‘colonial’ building in Melbourne. One of the last.

I knew the PM could sort out those heritage bastards who were standing in the way of one of the biggest shopping malls in the Southern Hemisphere in Australian history, and the Chows and their money were on the table. So it was a lay-down misère.

Then I heard on the grapevine that there was a rundown emu farm on the Queensland border of bloody nothing.

I persuaded the Australian Prime Minister to spend half a mill on that shit property in the outback. Everyone laughed at him, but I told him to hang on.

Well, about 18 months later, the emus had all carked it, but the Indonesians offered my eminent mate 20 million big ones for that shitty bit of nothing.

Turns out it’s full of uranium worth a zillion. Even after they had squared off the Aboriginal owners and their shonky Sydney lawyers, there was still a shitload left in the pot. The PM was as happy as a pig in poo.

But he owed the Indos big time, didn’t he? A bit of payback was required. There are more ways than one to bribe a head of state, and our bloke wasn’t too smart at international wheeling and dealing, though he’d come a long way from selling Toyotas on the Parramatta road.

Of course the bloody Indos used the poor bastard to the hilt – concessions here, mining rights there, deals worth a zillion. Even I got a finder’s fee – a week in Jakarta for two with all the trimmings.

Sadly, my wife, Gwen, God love her, couldn’t make the trip because they were running a few more tests on her that week, and I was forced to rub along without her. Me and Meredith Acropolis went instead.

My Gwen was off with the fairies thanks to the three Vs: Valium, vodka and Vera. She loves that TV show. She watches it mostly for the fashion tips.

A couple of Labour administrations later,

I was in strife again for going the grope – at a Christmas party of all things!

I bet little Jesus saw a thing or two going on with the shepherds and shepherdesses when he peeped out of the manger. Well, I was sent for ‘counselling’ by a not unco-operative shrinkess*, but I was fed up. I’d served Australia selflessly for donkey’s years, and what did I get?

Counselling! I want out. I’m sick of bloody woke. With my international credentials and my grasp of pretty well everything, I’m starting the new year on Les Patterson’s terms.

It’s not generally known that I groomed Tony Blair, and one of his team leaked it to me that old Tone makes a bundle on the lecture circuit. Particularly in the US. The Seppos† lap up his story about how he talked the heartless Royals into leaving their funkhole at Balmoral Palace and coming down to London to chuck a few daisies on Lady Di’s casket.

Boy, do they love that ‘true’ story!

The exclusive agency that handles Tone suggested a title for my lecture tour: LES PATTERSON, MUSINGS AND APERÇUS. To be perfectly honest, I’ve never done either of them, but if I wanted an audience of wall-to-wall pillow-biters and freckle-punchers, then that would be the perfect title.

In my search for a top job, I had an interview yesterday.

‘What is your greatest weakness, Sir Les?’ asked the too-clever-by-half interviewer.

‘I reckon it’s honesty,’ I replied, after a moment’s reflection.

‘I don’t think that’s necessarily a weakness,’ said this smartarse.

‘I don’t give a f**k what you think,’ says I, quick as a flash.

Have a good one!

LES

* A female psychiatrist † (Aust coll, obs) Hypocorism for septic tanks – Yanks

Sir Les Patterson was caught with a nubile research assistant with his trousers down – but got off scot-free

The first Rainbow Gathering was in 1972, when thousands of people climbed Table Mountain in Colorado to pray and meditate for world peace.

In the summer of 1986, I received an invitation at a Hare Krishna temple in Los Angeles to go to one of the Gatherings in the foothills of Big Sur, California – an invitation that was to change my life.

What followed has been an epic 36-year journey of love and learning with the Rainbow Family, which has taken me to Gatherings all over the world – Hawaii, Thailand, Morocco, Russia, Guatemala, the Canary Islands, Australia, the Arctic Circle, Israel, Mexico and almost every country in Europe. My daughters have grown up at Gatherings and still sing the Rainbow songs.

I decided to put together a new book of my photographs to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Gatherings.

The Rainbow Family is not an organisation. It is non-commercial, non-political and non-religious. It has no leaders and no one to represent it.

At least three Gatherings happen every month all over the world. Thousands of people go to Rainbow Gatherings and yet it has no members. Some say it is the largest non-organisation of non-members in the world.

Gatherings can be reached only by foot and are often at the end of a long trail through a forest, a jungle or a desert.

My longest walk in was a gruelling eight-hour climb up a trail in the Dolomites in Italy.

The Gatherings last a month and follow the lunar cycle, new moon to new moon, peaking with a full-moon celebration in the middle.

The heartbeat of every Gathering is the music and the singing circles. Heart-

opening Rainbow songs, medicine songs, bhajans and mantras are sung communally in dance, in praise, in reverence – around campfires or in tipis. There are no facilities. Everything is done as organically as possible. We wash in streams, rivers or lakes. We cook on open fires. We drink from fresh-water springs. We dig communal or private ‘shit-pits’ and use ash, lime and earth to cover up our deposits.

We take everything out that we bring in. We aim to leave nature more beautiful than we found it.

It’s incredible but it works – we always have an abundance of everything that we need. The magic and the connection you feel are the essence and heartbeat of Rainbow.

Joth Shakerley’s Rainbow is available from jothshakerley.com (£65)

For 55 years, Peter Tatchell, 70, has been beaten up at protests. Just back from Qatar, he reveals how he prepares for his injuries

When I was asked by Qatari human-rights defenders to stage a protest in Doha in the run-up to the World Cup, I was apprehensive.

Sure, I’ve done more than 3,000 protests over the last 55 years, been arrested 100 times and experienced 300-plus violent assaults. So I’m a risk-taker and not afraid of a few knocks.

But Qatar upped the risk factor to a much higher level. It is a police state where protests are banned. Protesters get beaten and jailed. Westerners have died after being arrested. I was afraid – but my fears were overridden by the importance of shining a light on Qatar’s abuse of women, LGBTs and migrant workers.

I knew protesters can end up in prison for several weeks – or months. I took a calculated gamble that the Qataris would not want bad publicity a month before the World Cup.

When I said goodbye to my partner the day I left for Doha, I was anxious. I did not know when we would see each other again. I made an addendum to my will and left him money to pay my share of the bills for the next few months, in case I was incarcerated. Unlikely, I thought, but not impossible. Best to prepare for an ugly outcome.

To get into Qatar, and evade pervasive state surveillance, I borrowed ruses and deceptions that I’d read about in spy novels: hiding my placard in a copy of the Daily Telegraph; using evasion techniques to lose any state agents on my trail; taking a new, clean mobile phone; and avoiding all contact with Qatari rights activists.

Once I got there, I posed as a tourist, visiting the information office and taking selfies outside Doha’s main attractions.

It worked. I succeeded in staging a one-man protest in front of the National Museum of Qatar. But not for long.

Police and state security turned up. I was detained and interrogated on the pavement. When they warned me that what I was doing was illegal and a serious offence, I feared the worst.

To my surprise, after 49 minutes I was released and told to go to the airport and get my onward flight to Sydney. The Qataris apparently realised that jailing me would be a PR disaster 26 days before the start of the World Cup.

The story of my protest and the human-rights issues I raised were reported by over 4,000 media outlets worldwide, reaching an estimated audience of nearly a billion people.

That was the objective: to expose the abuses of the Qatar dictatorship and stand in solidarity with brave Qataris who are striving for democratic reform.

They can’t protest, out of fear of the draconian consequences. So I went to Doha to amplify their cause and support their struggle.

Since I was 15, I’ve done many similar protests – some are depicted in the current Netflix documentary Hating Peter Tatchell. They’ve included staging the first LGBT+ protest in a Communist country, in East Germany in 1973, which resulted in my interrogation by the Stasi. I went to Moscow in 2007 to support Russian LGBT+ activists who attempted to hold a Pride parade.

We knew the dangers and, sure

enough, I and others were badly beaten by neo-Nazis, with police collusion.

I am best known for two attempted citizen’s arrests of the Zimbabwean dictator Robert Mugabe – the more recent one, in 2001 in Brussels, resulted in my being beaten unconscious by his thugs. On the bright side, it helped highlight the brutality of his regime.

These bashings have left me with a bit of cognitive and eye damage. But it doesn’t stop me. I’m still campaigning.

Despite the many edgy protests that I’ve done, they’re still incredibly nerve-racking every time. I fear not succeeding – being caught before I manage to do the protest. I also fear jail time or being beaten. The nervous tension causes a splitting headache. I feel nauseous. My stomach churns over.

I get the shakes and my body temperature plummets. These physical discomforts don’t deter me. The campaign goal drives me on.

To reduce potential injury, I wear padded clothes and a small rucksack to protect my back. I stuff tissues in my back pockets to cushion a fall. My protest trousers have deep pockets or zips, so I don’t lose my money and phone if the police throw me around.

I carry ID and proof of address to reduce delays in my release after arrest. Protests are physically exhausting, so I pack sweets and an energy drink.

Some people say I’m brave. No. Not in comparison to truly heroic humanrights defenders in Russia, Iran, China and Ukraine. They pay with their lives and liberty. I’ve never been jailed or tortured. I’ve got off lightly.

Retirement? No, thanks. I’d find it boring and there are still many humanrights battles to fight and win.

I’m 70 now and hope to continue for another 25 years. Like the Duracell bunny, I plan to go on and on.

Hating Peter Tatchell is currently on Netflix

I was watching daytime television, as a way of decompressing, when a charming old boy in a three-piece tweed suit appeared on the screen.

He was sitting by a crackling log fire in a book-filled room with a dog at his feet as he answered, in alert and genial manner, the questions of his interviewer.

I was just thinking to myself, ‘I wonder if he’s a widower?’ as I called to mind an elderly spinster friend who might be just up his street.

But, as the camera moved into close-up, I saw something stuck onto the centre of the adorable man’s forehead. Pale-pink-coloured and conical, it protruded about two inches from his head, with a diameter of about three inches.

What on earth was it filled with? And why was he not self-conscious about it?

The growth was, I judged, likely to be either seborrheic keratosis or a keratotic horn – both sun-induced – and whether benign or malign it clearly needed to be excised at a surgery. But the old boy continued to discourse in an amiable manner as though there were nothing wrong.

And there is the rub. A multitude of disfigurements can appear on the face, usually after the age of 50. When we get them, they creep up on us so slowly that we come to accept them as part of our facial landscape.

Blobs – a non-clinical term, obviously, but the one into which category I place the aforementioned horn – include everything from the tiny skin tags that look a bit like Rice Krispies hanging by stalks off the face and neck, to colourless facial warts and slow-growing cysts, which can spring up on any site on the head and can, if left untreated, grow to the size of a tennis ball.

Even if we admit to ourselves that these blobs exist, two factors make us ignore them.

One is the syndrome exemplified by Dr Max Pemberton, the Daily Mail’s doctor: FOFO (Fear of Finding Out),

Warts and all: Cromwell told Peter Lely not to ‘flatter me at all; but remark all the roughness, pimples, warts and everything’

Pemberton himself, despite being a practising doctor, left a red mark on his own face for a year because of FOFO. He knew that the sooner he went to have it checked out, the better – but he still left it a year. When he finally went to a dermatologist, the diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma and, luckily for him, it has been caught in time – just.

The second factor is that we don’t like to bother our overstretched NHS GPs. And the third is that even if we can pay for a private dermatologist, that would involve getting a referral letter from our overstretched NHS GP – and so we tend to put the problem on the back burner.

Don’t do this. The vast majority of unsightly blobs on the face are entirely

benign and can be swiftly dealt with. If you do not have them removed, they act as a distraction to your interlocutors.

They can’t concentrate on what you are saying. They are putting all their energy into not staring at the blob and wondering how they can tactfully suggest you have it dealt with.

Another age-related disfigurement is called an angioma. Angiomas are bright-red mini-blobs with a cherry like appearance. There are also spider angiomas, which lie just below the skin’s surface and radiate outwards like a spider’s web. These are also harmless and often worn proudly by those country dwellers who see themselves as merely ‘ruddy-faced’.

May I inform you that any skin blemish – even a tattoo – that is not standing proud on your face can be made invisible – I promise you – by Veil Cover Cream. You get sent a little selection of colours to try before buying. It is simple to apply; be sure to follow the instructions carefully for best effect.

The standing-proud blobs can often be simply sliced off by means of curettage. Seborrheic keratosis – flat, colourless, raised bumps under the skin –are often more prevalent on male faces than on female. These are entirely benign clinically – but not visually. Mercifully they can be treated by shave excision, in other words the doctor simply slices them off – with no lasting scars.

I myself have twice been able to help people by gasping guilelessly, as though I’ve only just noticed it, ‘Oh look! You’ve got a thing on your face just like I used to have. I’ve just had mine cut off by the brilliant Mr P. Have you heard of him? He’s the dermatologist everyone is going to. It was entirely painless and he reassured me it was benign. Do you want his number?’

Both of them did want his number –and, by use of this chatty, conversational approach, neither was offended.

Don’t ignore warts, cysts and skin tags. They can be easily removed

In 1989, I moved from the country to live in a mansion-block flat in Battersea, with my family and bull terrier, Parker.

Through Parker and his canine friends I met a variety of local people, including many of my neighbours. There was one who commanded attention, and I often saw him walking in Battersea Park where we exercised our dogs.

He was tall and well-built with broad shoulders and long limbs. Nobody approached him, as he looked forbidding and seemed quite private. He usually carried a football and was always accompanied by his small dog.

One day, when I was in the park talking to a neighbour, this impressive looking man passed us.

‘Do you know who that is?’ my neighbour said, once the coast was clear. ‘He’s John McVicar.’

Memories came flooding back from the newspapers I’d read. McVicar (1940-2022) was an armed robber who managed to break out of Parkhurst. He promptly tried to rob an armoured security van and went back to jail. He escaped again and was made Public Enemy Number One by Scotland Yard.

After his recapture and eventual release, his autobiography was made into a film, McVicar (1980), in which he is played by the lead singer of the Who, Roger Daltrey.

Now I realised McVicar lived in the block of flats next to mine. I couldn’t recognise the description given of him as a violent thug; he was always courteous and reserved. He liked to hear about Parker, and his own dog, Clemmy, used to greet me like an old friend.

One evening, when I was taking Parker for his walk, I was aware McVicar was behind me. He was with Clemmy, returning to his flat on the first floor. Just as I was about to turn back to go home, his dog appeared and started to jump up at me.

Parker was enraged, picked up Clemmy by his jaws and shook him violently. The dog screamed and I tried to separate him from my bull terrier. Without saying anything, McVicar took over and managed to free his dog. I assumed I’d be in deep trouble but, to my astonishment, McVicar was very understanding and polite. After that, he invariably asked after Parker and we would have a friendly chat.

After about a year, a young man called Scott moved into the flat next to mine. He owned two very large dogs who were locked up in his flat and howled.

A few months later, the area was buzzing with rumours. A young man had been badly beaten up by McVicar and reporters were gathering to interview the locals. Everyone thought McVicar would be sent back to prison for years.

Eventually more details came out. Scott, my neighbour, had been attacked over something that involved his two dogs.

Scott had come home early in the morning to let his dogs out. McVicar was just about to go into his flat when Scott’s dogs saw Clemmy, rushed forward and proceeded to tear her to shreds.

McVicar dived in to rescue her and

his arm was badly bitten. He held up his bleeding arm and asked Scott what the hell he thought he was doing. Scott retaliated with a stream of insults and became extremely aggressive. Provoked beyond endurance, McVicar beat up Scott, who ended up in casualty with bruises and a broken nose.

After leaving hospital, Scott contacted the Sun with his story. He was due to receive several thousand pounds following an almost certain conviction.

I told a friend of McVicar’s I would be happy to be a witness to his behaviour over the incident with Clemmy. Summoned to Kingston Crown Court, McVicar defended himself. I appeared as the main character witness. He gave his account of what had happened, and his calmly delivered defence was convincing.

The judge seemed impressed. I told the court what had happened when Parker shook Clemmy ‘like a rag doll’ and McVicar acted with politeness and restraint.

Later that evening, I heard on the radio that John McVicar had been found innocent. He left a message on my answerphone thanking me profusely and inviting me to have dinner with him.

I was pleased to accept. He took me to a fashionable Battersea pub and we talked for hours, mostly about athletics and the weightlifters competing in the Olympics – interests we shared.

I’m glad to have known John McVicar, a strangely intense, private man. It was impossible not to admire him for overcoming a violent past to educate himself in prison and pursue a career as a journalist and author.

I wasn’t surprised to hear that when he died recently, he’d been living happily in a caravan in Essex, away from everyone he knew.

A fiercely proud man, he wouldn’t have wanted anyone to witness his physical deterioration.

John McVicar – the armed robber who kept breaking out of jail – was a lovely neighbour, says Vivian Marnham

The university’s classics department is threatening to cut back on Homer and Virgil. Amelia Butler-Gallie is horrified

Otempora! O mores! The Classics faculty at the University of Oxford is looking more likely to proceed with proposed reforms to the degree course, first suggested in 2020.

Homer and Virgil – the greatest poets of Greece and Rome – would be pushed to the sidelines in favour of a more diverse assortment of Classical texts and contexts. Horribile dictu!

The implications – not only for undergraduates, but also for the wider cultural messages this sends about how we value civilisation’s most magnificent literary works – are gargantuan.

The reforms would mean the compulsory study of the Iliad and the Aeneid, normally examined during second-year Honour Moderations (or Mods), becomes an optional study for papers in Greats, the Classics Finals papers.

As Virgil warned in Book VI of the Aeneid, ‘facilis descensus Averno’, ‘the descent to hell is easy’!

I applied to study Classics at Oxford a few years ago and was, quite rightly, rejected. The dons who interviewed me easily sniffed out my grammatical ineptitude and lack of linguistic ability.

But I did end up reading English there and have always retained a deep love of – and veneration for –Classical literature.

Only a lunatic would contemplate exiling Shakespeare from the English syllabus because he’s too difficult.

That’s precisely what makes Shakespeare worth reading at degree level. To ignore him would be to miss thousands of vital allusions and references in lesser-known writers who came after him.

In my English degree, Shakespeare is so indispensable to a comprehensive view of English literature throughout the ages and his language so inexhaustibly complex that he is given an entire paper

in my English exams. Surely Homer and Virgil deserve the same level of reverence, if not more?

Seeking to make Classics more accessible to those who have not had the opportunity to attend private schools sounds laudable, but it will backfire.

Pupils who did Latin or Greek A-Level will certainly have read extracts from the Iliad, the Odyssey or the Aeneid (in the original or in translation) before university. What good does it do to delay introducing the magna opera of Classical antiquity to less fortunate undergraduates once they get to Oxford?

In the name of access, these texts will be reserved for and enjoyed by a coterie of privileged public-school students. The Classics – and their literary treasures – belong to everyone, regardless of background.

Some people claim that banishing Homer and Virgil from Mods will make work more ‘manageable’ for all students. This bureaucratic jargon reeks of the old jibe that my generation (Generation Z) is less capable of learning the same things our predecessors encountered. Patronising and untrue.

Maintaining high standards is

actually a kindness, mollycoddling an insult.

The Classics department ought to have more faith in their undergraduates’ ability to engage with and grasp challenging ideas. As the American politician Jesse Jackson said, ‘No one has ever suffered from being talked up to.’

Homer and Virgil wrote universal truths – and garner universal appeal. Their influence on writers both within and beyond the ancient world is immeasurable. How hubristic to remove them from the centre of the Classics course at the university that has been the centre of Classical scholarship for centuries.

As Virgil wrote in the Aeneid, ‘Sunt lacrimae rerum.’ Seamus Heaney’s translation captures the sense: ‘There are tears at the heart of things.’

Amelia Butler-Gallie is a postgraduate researcher in 18th-century literature at Lincoln College, Oxford

As Jesse Jackson said, ‘No one has ever suffered from being talked up to’Virgil with muses Clio and Melpomene – Tunisian mosaic

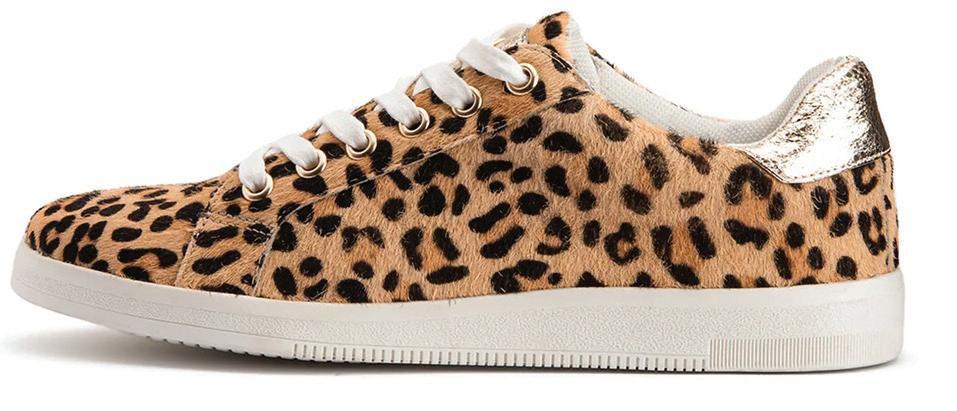

Goodman loves her leopard-skin pair

When she was my age – in her seventies – my maternal grandmother had two pairs of shoes and a pair of slippers.

Both shoes were lace-ups on sturdy, two-inch heels, of the kind nannies or schoolmistresses wore.

My paternal grandmother had two similar pairs and a pair of wellington boots because she lived on a farm.

Both had roughly the same uniform: tweed, pleated skirts, cream blouses and a long cardigan with a pocket for a handkerchief.

My mother was much more fashionconscious well into her nineties. Her favourite magazine was Vogue. She was aware of trends – big bows at the neck and padded shoulders when Mrs Thatcher was power dressing.

She would take the hems up and down – just the right amount above or below the knee to conform with the direction of travel laid down by fashion editors.

And she always looked good.

Her biggest regret was her feet –which I have inherited. A doctor stupidly told her when she was 12 that she wouldn’t be able to walk as an adult because they were so weak.

In fact, she could walk almost up to the time she died, but only if she wore shoes made for her by the NHS, stuffed with arch supports. They were flat leather lace-ups – one grey pair and one navy. She despaired of ever looking really glamorous in them.

How much easier it would be for her today. Now everybody wears trainers.

They evolved many years ago out of shoes worn for exercise. When I was a child, my mother would never have let me swap my Start-Rite sandals for them: ‘only village children’ wore plimsolls, as they were called then.

Now they cross all class divides. When ITV’s Robert Peston interviewed former prime minister Liz Truss at the Tory Party conference, both of them were wearing trainers.

Peston complained recently that he was forced to remove his trainers at a London gentlemen’s club and borrow some of their smart shoes.

Princess Alexandra is said to wear trainers at formal functions. The former MP Nicholas Soames, now a peer, wears trainers with Savile Row suits. Other MPs wear trainers to speed between the Millbank TV studios and the Commons.

The trend accelerated in lockdown. When I crept back to London after almost two years in the country, everyone of all ages seemed to be wearing trainers.

Some carried bags with high heels in them for meetings with clients or to pop into the Ritz, which bans trainers (the nightclub Annabel’s will let you in, provided they are ‘fashion’ trainers). When the late Peter Cook was asked to remove his before gambling at the Ritz Casino, he said, ‘What? My lucky trainers?’

Alongside everyday trainers, I have a leopard-skin pair, expressing my inner Theresa May, and another pair with sparkly stars. I wore these recently at a funeral.

Fashion magazines show young models wearing floral dresses with ‘elevated trainers’. One magazine assured an anxious reader that flowery trainers are fine for weddings. And according to the Guardian, ‘trainers with a trouser suit became the go-to look for

CEOs doing Ted Talks’. Influencers offer advice on what colour trainers to wear: white last year.

The problem is once your feet have got used to comfort, they rebel angrily when pressganged into high heels. And there are certain things you can’t do in trainers – such as dance the tango, or dine at certain men’s clubs. One woman is currently involved in a legal suit with a staid City club whose rules insisted on a trainers ban.

On a recent trip to that emporium of middle-class respectability Peter Jones, 80 per cent of the women were wearing trainers or rubber-soled jodhpur boots. The only stilettos were on mannequins in the windows.

It won’t last. When the older generation starts wearing the uniform of the young, the younger generation moves on.

My generation likes to think of itself as not bound by the rules that meant most grandmothers dressed alike 60 years ago.

We wear jeans, almost regardless of the shape of our backsides. We like to think we are expressing our individuality by wearing whatever skirt length we like, bright colours and voluminous knitwear to cover the bulges.

I have a vision of the time when I have to go into a home. All the residents will be wearing trainers. Some wellmeaning, irritating entertainer will urge us to get up and dance in them. They will be as much a uniform for us as those little, heeled lace-ups were for my grandmothers.

Grandchildren, meanwhile, will have their feet in plaster after operations for bunions from wearing stilettos after trainers went out of fashion.

Elinor Goodman was political editor of Channel 4 News, 1988-2005

In 1984, Margaret Thatcher was due to visit the famous school. Two days before, a menacing ‘parent’ cased the joint. By Robert Portal

In the autumn of 1984, the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was invited to be the guest of honour at Harrow’s annual School Songs. I was at the school at the time.

Churchill Songs, as the event is known, involves the whole school together singing from the school songbook, followed by an address from a person of note with links to the school, on a topic of their choice.

School security (such as it was – there wasn’t much) was ramped up. On the Tuesday (Songs was on the Thursday), our custodian (known as Custos) was in Speech Room, where Songs is held.

In walked a man with a strong Northern Irish accent, asking if he could be shown round the school as he might be interested in enrolling his son as a future pupil.

Smelling a large rat, Custos let him into Speech Room before darting out, slamming the door and locking it. He then went off to inform the head of school security, who told him to keep the door locked and he would ring Special Branch.

Special Branch told him to keep the man there – they were on their way. The head of school security then ran over to Speech Room. There, to his consternation, he found the door open, Custos looking sheepish – and no Northern Irishman.

Custos explained that the man had been trying to smash the door down with such violence, he’d felt he had no choice other than to open it.

This was what he repeated to Special Branch when they arrived. Custos was asked to accompany them back to

Paddington Green to identify this man using the old-fashioned Identikit. This he did.

And that seemingly was that until, one morning, three weeks later, on 12th October, the country awoke to learn of the atrocity committed by the IRA in Brighton. A bomb had been detonated at the Grand Hotel, killing five and brutally injuring many, including Norman Tebbit and his late wife, Margaret Tebbit.

A manhunt then followed to find the perpetrator. He was eventually caught, tried and was sent to prison.

His name? Patrick Magee. The same man who came to our school, asking to look around, as he was interested in enrolling his son as a future pupil.

The kitchens of the National Liberal Club are closed until May. So we have decided to go on tour, in aid of local charities (save the dates: 26th April at Fairlight Hall near Hastings; 9th May, back at the National Liberal Club)

on Et Tu, Brute? The Best Latin Lines Ever, written with John Davie Latin omnibus, from Virgil to saucy gra iti

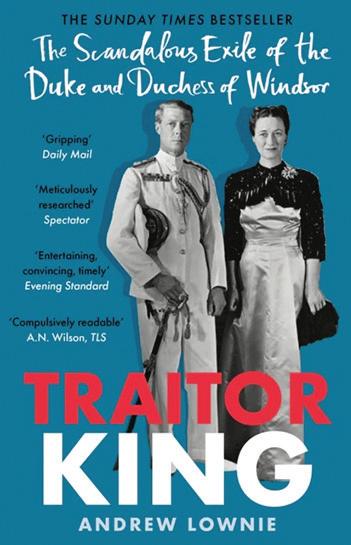

on Traitor King: The Scandalous Exile of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor The gripping tale of the Windsors after the Abdication

on Diary of an MP’s Wife

The juicy inside story of the David Cameron years

From The King’s Speech to The Crown, historical dramas are full of lies. Playwright Francis Beckett prefers the truth

Turning history into drama, you have some artistic licence.

You can be cavalier about the precise facts, alter the sequence of events and even invent some, and you have to invent a lot of dialogue.

But is there a line you mustn’t cross?

In November, two former prime ministers, Tony Blair and John Major, attacked The Crown for depicting Prince Charles (now King Charles) lobbying them to help force his mother to retire.

I know the problem. I’ve just written a historical play, Vodka with Stalin. It tells the story of the troubled relationship between Stalin and the Communist Party of Great Britain.

The meetings with Stalin happened, but I invented a pivotal scene between Communist leader Harry Pollitt and Labour Party leader George Lansbury.

My other play, A Modest Little Man, about Clement Attlee, has been performed in London and Liverpool. I wanted to build up the importance of my central character. So I was less than fair to big figures in his Cabinet, such as Nye Bevan and Herbert Morrison.

It was on Attlee’s behalf that I felt indignant when I saw the 2017 film Darkest Hour. Writer Anthony McCarten gives us a war cabinet in 1940 that believes Britain to be defeated and wants to negotiate with Hitler. Winston Churchill (Gary Oldman) is isolated and alone until King George VI gives him support.

Which is rubbish. Churchill’s crucial support came from Attlee and Attlee’s deputy, Arthur Greenwood. Churchill, Attlee and Greenwood outvoted the defeatists, Chamberlain and Halifax, in the five-member war cabinet.

I cannot see a good dramatic reason for not telling the truth here.

In 1940, Britain was hours away from a German invasion that military chiefs thought would succeed. That the government was not panicked into negotiating was mostly the work of Churchill and Attlee. That’s a dramatic enough tale. Why not tell it?

There’s also a widely mocked scene in the film, in which Churchill takes a trip on the London Underground and speaks to Ordinary People who buoy him up with their John Bull spirit. It’s laughable but transparent, unlike the falsehood about defeatism, which is neither.

There’s another example in the 2010 film The King’s Speech, about the speech therapist who enabled King George VI to speak without stammering.

Timothy Spall’s Winston Churchill urges Edward VIII to abdicate in 1936. He tells the future George VI (Colin Firth), ‘Parliament will not support the marriage [to American divorcee Wallis Simpson]. There are those who are worried about where he will stand when war comes with Germany.’

This is the opposite of the truth. Churchill wanted the King to face down Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and stay on the throne. Churchill was even touted as the leader of a potential ‘King’s Party’.

It lent weight to the stammering story if you could link it to the much bigger issue of fighting Hitler, even though no one made this connection at the time. In a film that simplistically pits the goodies (pro-abdication) against the baddies, it’s convenient to have a national hero like Churchill on the side of the goodies.

As history gets more recent, offence is more likely. I have seen in Neil Kinnock’s archive a hurt private letter he wrote to David Hare after seeing the latter’s 1993 play, The Absence of War. Though the leading character was called George Jones and was not Welsh, Hare admitted he was a thinly disguised Kinnock, struggling through the 1992 general election, which Kinnock unexpectedly lost.

Kinnock wrote to Hare, ‘No one watching it, or writing about it, will make the distinction between what is biographical and documentary and what is fictitious and theatrical.

‘George is remote, garrulous, innumerate, a noble soul manipulated into respectable coma and searching for scapegoats.’

Hare felt Kinnock was seeing it not as drama, but as reportage, which it isn’t.

I have some sympathy with Kinnock. As he wrote to Hare, the play ‘echoes the mythology’. No one seeing it was going to say, ‘It’s only a play.’