HAMMER HORROR GLAMOUR GIRL – MADELINE SMITH JOANNA LUMLEY ON ASIAN FLU

June 2020 | £4.75

www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 388

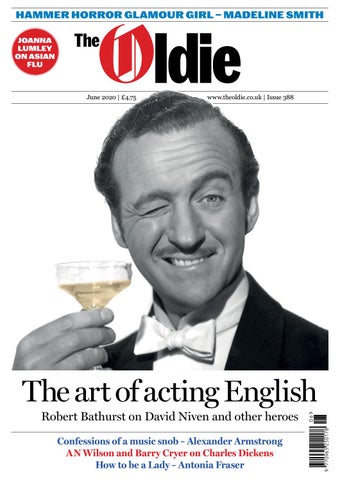

The art of acting English Robert Bathurst on David Niven and other heroes Confessions of a music snob – Alexander Armstrong AN Wilson and Barry Cryer on Charles Dickens How to be a Lady – Antonia Fraser