The Wizard from Oz

by Roger Lewis, Nicholas Garland and Bruce Beresford

Cannon without Ball – Tommy Cannon goes solo The genius of – Andrew Roberts

June 2023 | £4.95 £4.13 to subscribers | www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 427 MAX WALL, MY PAL – BY KENNETH CRANHAM MATT CARTOON BY

PRITCHETT ‘The Oldie is an incredible magazine – perhaps the best magazine in the world’ Graydon Carter

Humphries

MATT

Barry

Features

10 Grumpy Oldie Man

Matthew Norman

12 Olden Life: What was a thankyou letter? Susannah Jowitt

12 Modern Life: What is second-screen content? Richard Godwin

40 Mary Killen’s Fashion Tips 42

Regulars

Editor Harry Mount

Sub-editor Penny Phillips

Art editor Jonathan Anstee

Supplements editor Jane Mays

Editorial assistant Amelia Milne

Publisher James Pembroke

Patron saints Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

At large Richard Beatty

Our Old Master David Kowitz

95 Competition Tessa Castro

102 Ask Virginia Ironside

Books

58 Yorkshire: The North Riding, by Jane Grenville and Nikolaus Pevsner

Martin Vander Weyer

59 An Uneasy Inheritance: My Family and Other Radicals, by Polly Toynbee Roger Lewis

61 The Jewel Box: How Moths Illuminate Nature’s Hidden Rules, by Tim Blackburn

Caroline Moore

63 The Story of the Brain in 10½ Cells, by Richard Wingate Dr Theodore Dalrymple

63 Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard Artists, by Laura Freeman Huon Mallalieu

65 One Fine Day, by Ian Marchant Nicholas Lezard

67 Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines and the Health of Nations, by Simon Schama Ivo Dawnay

Arts

72 Film: Still: A Michael J Fox movie Harry Mount

73 Theatre: The Motive and the Cue William Cook

73 Radio Valerie Grove

Oldie subscriptions

To order a print subscription, go to www. subscription.co.uk/oldie/offers, or email theoldie@subscription.co.uk, or call 01858 438791, or write to The Oldie, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF.

Print subscription rates for 12 issues: UK £49.50; Europe/Eire £58; USA/Canada £70; rest of world £69.

To buy a digital subscription for £29.99 or single issue for £2.99, go to the App Store on your tablet/mobile and search for ‘The Oldie’.

74 Television Frances Wilson

75 Music Richard Osborne

76 Golden Oldies

Rachel Johnson

77 Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu

Pursuits

79 Gardening David Wheeler

79 Kitchen Garden Simon Courtauld

80 Cookery Elisabeth Luard

80 Restaurants James Pembroke

81 Drink Bill Knott

82 Sport Jim White

82 Motoring Alan Judd

84 Digital Life Matthew Webster

84 Money Matters

Margaret Dibben

87 Bird of the Month: Sedge warbler John McEwen

Travel

88 A trip through breakthrough European art Nick Trend

91 Taking a Walk: Mum’s last walk Patrick Barkham

96 On the Road: Ann Widdecombe Louise Flind

Advertising For display, contact :

Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Rafe Thornhill on 020 3859 7093

For classified: Jasper Gibbons 020 3859 7096

News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

The Oldie Spring 2023 3

13 Let’s talk nonsense Piers Pottinger

14 Tommy Cannon without Bobby Ball William Cook

neighbour

Valerie

Joy of accidents

Philip Larkin, Bletchley

reject Tim

Build your own swimming pool Matthew Faulkner 31 Teenagers’ growing pains Charlotte Metcalf 32 My friend, Max Wall Kenneth Cranham 35 Where’s the corned beef? Trevor Grove

On the Buses, 50 years on Andrew Roberts

Men shouldn’t wear wedding

Liz Hodgkinson

17 Remembering Roger Deakin Patrick Barkham 18 Barry Humphries, Renaissance man Bruce Beresford 20 Barry’s last words Roger Lewis 22 Our

from Hell

Grove 23

Oliver and Matt Pritchett 25

Park

Whitaker 29

36

39

rings

The

Notes

Brandreth’s

5

Old Un’s

9 Gyles

Diary

Postcards from

Mary

School

Quite Interesting

about ... lunch

God

52 Memorial Service:

James

The Doctor’s

Dr

54 Readers’ Letters

I Once Met… John

Jennifer

Memory Lane Terry

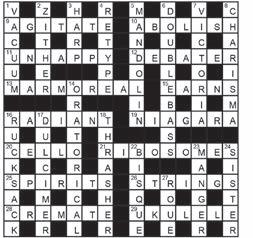

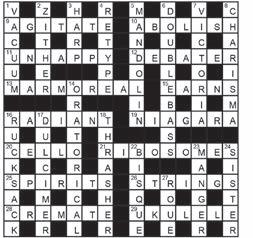

69 Commonplace Corner 69 Rant: Cash-free society Julie Cruickshank 70 Oldie Man of Letters A N Wilson 93 Crossword 95 Bridge Andrew Robson

History David Horspool 44 Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson 45 Country Mouse Giles Wood 47

the Edge

Kenny 48 Small World Jem Clarke 51

Days Sophia Waugh 51

Things

John Lloyd 52

Sister Teresa

Dame Hilary Mantel

Hughes-Onslow 53

Surgery

Theodore Dalrymple

56

Hurt

Florance 56

Morgan

House, 23/31

Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk

Moray

Great

o er

lunch p85 ABC circulation figure July-December 2021: 48,249 Subs Emailqueries? co.uksubscription.theoldie@ or 01858phone 438791

Reader

Oldieliterary

Last stop for On the Buses page 36

when you subscribe – and get two free books

Cannon on Ball page 14 Max Wall by Kenneth Cranham page 32

Save

See page 23

The Old Un’s Notes

In 1941, John Betjeman became British press attaché in Dublin.

To begin with, he disliked his time there, but increasingly he loved his three years in the country and took to signing off his letters, ‘le meas mór, do chara dhílis, Seán Ó Betjemán’.

And now a new book, Betjeman in Ireland, by Dominic Moseley, covers his visits to the country, from his first in 1925, as an Oxford undergraduate. Over 50 years later, he made a charming BBC programme, John Betjeman’s Dublin.

Betjeman wrote many poems in Ireland – and amusing letters, too. In 1943, he wrote to Myfanwy Piper, wife of artist John Piper:

‘Still do you run barelegg’d across the yard?

Still would you pillow with athletic curves

My bald, grey head upon your breasts?

Your stalwart body still excites me much

The thought of you, now spring is coming on,

Requires that I should exercise control.’

Though modest, funny Betjeman always played down his achievements, it’s clear he was good at the press-attaché job.

When he left Dublin, the Irish Times declared, ‘He took the highest possible view of his duties as press attaché and looked upon it as his duty not only to interpret England to the Irish, but also to interpret

Ireland sympathetically to the English, and if any English pressman or visitor went away with an unsympathetic view of Ireland, it was not the fault of Mr Betjeman.’

Lots of oldies were to the fore at Chichester’s Minerva Theatre recently, when the estimable Dame Eileen Atkins took the lead role as a nonagenarian New York grandmother in Amy Herzog’s 4000 Miles.

The run ends on 10th June, five days before Dame Eileen’s 89th birthday. It was directed by Sir Richard Eyre, a mere stripling of 80.

Regarding the play’s grandparental theme, Eyre reflected that he knew only one of his grandparents, the others having died young. His father’s father was a curmudgeon who ‘presided over meals with an air of

Among this month’s contributors

Bruce Beresford (p18) directed Oscarwinning Driving Miss Daisy (1989). A friend of Barry Humphries for 60 years, he directed him in The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972).

Nicholas Garland (p19) and Barry Humphries (right) illustrated and wrote Private Eye’s Barry McKenzie cartoon strip.

Oliver Pritchett (p23) wrote for the Sunday Telegraph for 40 years. His son Matt(also p23) is the renowned Telegraph cartoonist.

Kenneth Cranham (p32) starred in Oliver!, Shine on Harvey Moon and Hatton Garden. A friend of Joe Orton, he was in Entertaining Mr Sloane and Loot He will be in Angel with Rafe Spall.

silent disdain interrupted by eruptions of volcanic severity’.

One day, Eyre’s ten-yearold sister said someone had talked to her on a train. Eyre recalled, ‘My grandfather slammed his fist on the table, shaking the glasses and the cutlery, and shouted, “No one’s ever spoken to me on a train, thank Christ!!”’

Grandpa Eyre, one suspects, might not have approved of those inane ‘See it, say it, sorted’ announcements on today’s railways.

A new biography by Alicia Foster, Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris, shows quite how rich our regional galleries and museums are, in lovely pictures.

Gwen John and her brother Augustus John grew up in Pembrokeshire. Augustus John’s talent was first spotted by a tutor at a Tenby art school, Edward Joseph Head, a Royal Academician.

Gwen John (1876-1939), born in Haverfordwest,

The Oldie June 2023 5

John O’Betjeman

Richard Eyre: 80 years young

Important stories you may have missed

Soldiers spotted during huge military exercise in Wiltshire Wiltshire Times

honed her skills in Tenby, too. She started painting Landscape at Tenby with Figures (pictured) when she was 19. The figure of the woman in the hat was modelled by Winifred John, Gwen’s younger sister.

Drug dealer branded ‘a risk to pigeons’

The Leader

Mystery after missing guinea pig is returned Aberdeen Press and Journal

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The July issue is on sale on 28th June 2023.

GET THE OLDIE APP

Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

OLDIE BOOKS

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

The only surviving picture by Gwen John of Tenby, it’s now in the Tenby Museum and Art Gallery, in the shadow of the castle, overlooking the sea. Tenby Museum and Art Gallery also has two pictures by Gwen’s mother, Augusta, an amateur artist.

What an artist’s colony Tenby was in the late-19th century, consisting entirely of the John family!

One of the annoying things about the House of Commons is that the anger is often so palpably fake.

A moment from Jamie Stone, Lib Dem MP for Caithness, Sutherland, and Easter Ross was a telling contrast.

Gordonstoun-educated Stone, 68, is a pukka gent who is almost always genial. He is widely liked at Westminster, most MPs being aware that he acts as carer to his disabled wife. But when he rose at Prime Minister’s Questions to complain about Edinburgh’s marine-protection proposals, Scottish National MPs started heckling him.

The result was remarkable. The mild-mannered, softlyspoken Stone combusted into fury, bawling that he would ‘not be silenced’ and that the policy mattered greatly to his constituents.

The very rarity of his anger meant it stunned the Scot Nats into silence and was met with cheers from elsewhere. Rage is at its most effective when deployed by gentle souls.

It’s quite a coup to be shot down by the Red Baron – and survive.

That was the fate of Tommy Lewis, the last and 80th man to be shot down by Baron von Richthofen, on 20th April 1918.

Flying a Sopwith Camel from 3(F) Squadron RAF in northern France, Tommy Lewis survived the crash landing with only minor burns.

The story is told in a charming new memoir, Beating About the Bush: The Memoir of a District Nurse, by Audrey Head, who nursed Lewis in later life.

Lewis kept a framed

‘I realise it’s a weeping willow, George, but there’s weeping and there’s weeping’

6 The Oldie June 2023 KATHRYN LAMB

Gwen John’s Landscape at Tenby with Figures (1895-8)

Dog ght: Red Baron (above) and Tommy Lewis (below)

photograph of the Red Baron over his bed and exchanged Christmas cards with the von Richthofen family for the rest of his life. The Red Baron himself was shot down and killed at Vaux-sur-Somme on 21st April 1918, only a day after Tommy’s close shave.

Don’t be surprised if you see a film crew lurking outside the National Liberal Club the next time you’re in London at the weekend.

The historic Victorian club, overlooking the River Thames, closes to members at weekends.

That’s when dozens of TV dramas and movies have been shot there: from Downton Abbey to The Crown, and The Constant Gardener (2005) to the Christopher Nolan-directed sci-fi thriller Tenet (2020).

Entering the club is like stepping back in time to another era. Filmmakers are attracted by ‘the ornate, 19th-century interior which offers the perfect setting for period dramas’, says club member Seth Thévoz.

The club has doubled as everything from a gentleman’s club to a lecture hall, and a hotel to a restaurant.

One room was even recently turned into Harrods Food Hall for A Thousand Blows, a forthcoming Disney+ period drama.

Television and movie companies pay good money to film scenes at the club – which hosts the Oldie literary lunches, as it did the Oldie lunch for the Queen’s 75th birthday last year – and the additional revenue stream is ‘very welcome’, adds Thévoz.

Look very closely in the background of some shots of the club and you might see the portrait of Jeremy Thorpe, the disgraced Liberal leader. With admirable bravery, the club has kept the picture hanging, despite Thorpe’s downfall.

Watch out for Simon Collins’s new book, The Little Boke of Woke, which cleverly imagines examples of woke behaviour in the old days. Pictured (below) is an example – of a virtuesignalling vicar 70 years ago.

‘Are you wokeing from home again, Henry?’

Barbara Ker-Seymer (1905-93) was one of the great photographers of the 20th century.

And now a new biography, Thoroughly Modern, by Sarah Knights, tells the story of the pioneering life of the bisexual photographer.

Among her sitters were Evelyn Waugh, Margot Fonteyn and writer, heiress

and activist Nancy Cunard (pictured).

Ker-Seymer’s friends spanned the generations. Her younger pals included the painter Beryl Cook (1926-2008).

Ker-Seymer became one of her models, too, appearing in Cook’s Bar and Barbara (1984) and Bermondsey Market (1987).

The Oldie June 2023 7

Cunard lines: Nancy Cunard by Barbara Ker-Seymer

A Simon Collins cartoon

‘Do you have an olive branch?’

The King and I

What a Coronation! There were lots of loos, Emma Thompson saved a choirboy – and I stole Lionel Richie’s seat

Our new king is a Shakespeare buff, so quite familiar with the famous line spoken by Francisco on the ramparts at Elsinore at the beginning of Hamlet: ‘For this relief, much thanks.’

This line was repeated by quite a few of us oldies lucky enough to be invited to the Coronation as we arrived at Westminster Abbey and found the ancient building almost surrounded by portaloos.

There had been a rumour that ‘facilities’ would be in short supply at the royal peculiar. People were upping the pre-crowning bladder panic by repeating apocryphal tales of ‘accidents’ that had occurred at the last Coronation in 1953. The Daily Mail called me to ask if I would contribute a feature they were hoping to headline ‘The Royal Wee’.

I declined, and how wise I was. Every aspect of the Coronation was brilliantly organised. The Dean and his ever good-humoured and consistently courteous team had thought of everything. There were ramps for the wheelchairs, smelling salts for the faint, defibrillators in the side chapels and clean and classy, unobtrusively placed toilets at every turn.

When things went awry on the day, it certainly wasn’t the fault of the organisers. We were invited to take our places from 7.30am and advised that we shouldn’t expect to leave until 1.30pm. I cut it a bit fine arriving at 8.30am and took what I thought was my place – only to be told, moments later, by the great Lionel Richie that, actually, it was his.

In the event, amazingly, I found myself seated at the end of a row of hugely distinguished old soldiers – all recipients of either the George Cross or the VC – and just behind the actress Dame Emma Thompson, who deserves an extra gong for services rendered on the day.

As the 14-year-old Child of His Majesty’s Chapel Royal, Samuel

Strachan, began to address the King, someone halfway along Dame Emma’s row began coughing. And went on coughing. Loudly. And more loudly still.

Emma reached for her handbag, found her packet of Bronchostops and passed them down the line.

Happily, I don’t think there were any medical emergencies on the day. Had there been, there were plenty in the congregation ready to come to the rescue.

After the service, walking towards Victoria Station, I fell into step with one of them. She was a retired nurse, she told me – and then, seeing her medals, I realised she was Dame Elizabeth Anionwu, the UK’s first sickle-cell specialist nurse and the first nurse to receive the Order of Merit since Florence Nightingale. An hour before, she had been carrying the Orb of Sovereignty in the Coronation procession. Now she was walking on her own along the Embankment in the rain with me. I felt proud to be British.

I felt proud, too, of my buttonhole.

To my surprise, it was the only one I noticed in the Abbey. It was made up of four miniature, cream-coloured roses I had pinched from a beautiful arrangement of flowers the day before and kept fresh in the fridge overnight.

My Coronation buttonhole came from Coronation Street. Truly, it did. I am a

regular on ITV’s This Morning and, naturally, our Coronation Special came from Salford, from the set of the longestrunning soap in the kingdom.

At the end of the broadcast, as William Roache (aka Ken Barlow), 91, who has been in the series since it started in 1960, led us in three cheers for King Charles.

I discreetly dismembered the floral arrangement that was decorating the bar of the Rovers Return.

I have been partial to a buttonhole since I was a boy.

One day in the mid-1950s, as I was walking along the Strand with my father, we caught sight of an elegant gentleman getting out of a London taxi and stepping in to the Savoy Hotel.

‘That,’ said my dad, ‘is the great Nubar Gulbenkian – he wears a fresh orchid in his buttonhole every day.’

He also wore a monocle, a long bushy beard and (can I have invented this?) spats. Born in the Ottoman Empire in 1896, he was educated at Harrow and Cambridge, inherited a fortune and made another one, did good stuff for British intelligence during the Second World War, and behaved as he felt an English gentleman should.

My dad called Gulbenkian ‘the Armenian Noël Coward’ and collected his quips. Gulbenkian owned two converted taxis and said of them proudly, ‘They can turn on a sixpence –whatever that is.’

He enjoyed fine dining, claiming ‘The best number for a dinner party is two – myself and a damn good head waiter.’ He was married three times: ‘I’ve had good wives, as wives go, and, as wives go, two of them went.’

On Coronation Day, I channelled my inner Nubar.

Gyles is at the Edinburgh Fringe in August: www.assemblyfestival.com

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

The Oldie June 2023 9

Right royal day: Emma Thompson; Norroy and Ulster King of Arms; Gyles

I’m fed up with feedback

Why should I review my new toothbrush?

In contemplating the toilet-plunger ordered this week in response to a blockage, as so cordially invited to do by Amazon, the mind flashes back to the quagmire football pitches of lateVictorian England.

On reflection, I’m not convinced that the above makes any sense. It could well be that I’ve been at the magic mushrooms, and am in the midst of a mildly hallucinogenic reverie.

If it isn’t the ’shrooms, the point may perhaps concern the touching tale of the Corinthian Casuals football team and the penalty kick.

The Casuals, the story goes, were so outraged by the unfairness of shooting unchallenged from 12 yards out that in protest they deliberately missed all penalties.

I mention this vignette from the glory days of British amateurism only because those days, hugely against the odds in a mercenary era, have returned.

We’re all of us amateurs now in the singular field of written criticism.

I write with the bitterness of snooker star Shaun ‘the Magician’ Murphy, complaining a few years ago that a young Chinese who beat him had no business being on the green baize at all since he was an amateur.

For decades, I covered a slew of disciplines (radio, TV, restaurants, movies) as a professional critic. The career was exquisitely tailored for one as unremittingly idle and mediocre as myself. Those who can do, as someone clever almost expressed it. Those who can’t skulk behind a computer screen sniping facetiously at those who can.

For occupying this very bottom rung of the showbiz ladder, the ultimate ambition being mildly to entertain a commuter for a maximum of two District Line stops, I was well-paid.

Criticism was not only lucrative back then, but easy. For the reviewer of daytime

telly, for instance, it was no tougher challenge 30 years ago to ridicule Eamonn Holmes and Anthea Turner than it has lately been to mine the captivating saga of Phillip Schofield and Holly Willoughby for mirth and merriment.

These days, the work is both unpaid and infinitely harder. What in the name of sanity are you expected to write?

The requests come by email, from one firm or another, all the time. ‘Your opinion matters to Spotlight Oral Care,’ reads the subject line of one recent droplet among the Niagaran cascade. ‘Thank you for your recent purchase. We hope you love it as much as we do.’

Do I, though? How am I to know? And, even if I do, should I? Wouldn’t it be presumptuous at best, and at worst positively creepy, for the mere buyer of an electric toothbrush to love it as much as its creators? Isn’t that just as unnervingly weird as loving a stranger’s child as much as its parents?

You wouldn’t want to admit to that in a review. To confess to an unnatural besottedness with a toothbrush would double as a formal application to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Still, duty calls. So for what it’s worth, while sidestepping the question of love, my opinion is this. The electric toothbrush works fine.

But that’s not going to win any prizes, is it? New Yorker magazine filmreviewer Anthony Lane might be the finest critic writing in the English language today. Even he would struggle to chisel a Pulitzer nomination out of a toothbrush.

‘Hey, M J Norman,’ goes another

request, this one about drinking glasses, ‘will you please take a minute to share your experience?’

A minute indeed. It would be the work of months, or years, or a lifetime, to unravel whether, to quote one of various questions, ‘the product meets your expectations’.

On the surface, it does. One expectation was that these tumblers would hold liquid without leaking – and they do. Until the email arrived, I naïvely assumed this to be the sole expectation.

Evidently, however, given the plural, there must have been others. Did I subconsciously expect the tumblers, if rubbed in a certain way, to unleash a genie? Or to be the catalyst for a neobiblically alchemical reaction that transforms water into malt whisky? I simply do not know.

‘Hi M,’ begins another of today’s communiqués, this from Amazon, either flirting with over-familiarity or confusing me with the late Bernard Lee, or possibly Judi Dench, ‘your package has been delivered. How was your delivery?’

How was it? Well, it wasn’t The Godfather, or the tasting menu at L’Enclume in the Cumbrian town of Cartmel, or Brideshead Revisited. It wasn’t even Phillip and Holly desperately faking mutual tolerance on the sofa.

It was identical to the last 973 deliveries. Some wildly over-pressurised, minimum-wage work slave rang the doorbell, and scarpered back to his van within the 3.27 seconds before I answered the bell, charitably leaving the parcel on the doorstep as an enticement for any passing tea leaf.

As for the plunger mentioned in that faintly psychedelic first paragraph, beyond reporting that it worked as advertised, I find myself in grave need of a psychic version to clear the feedbackwriter’s block.

Grumpy Oldie Man

10 The Oldie June 2023

matthew norman

The finest critic would struggle to chisel a Pulitzer out of a toothbrush

what was a thank-you letter?

The earliest surviving letter from Winston Churchill was a handwritten note to his mother.

In 1882, aged seven, he wrote to thank her for his gifts of ‘soldiers, flag and castle’.

The painstaking italic penmanship of the very young Churchill later gave way to the easy, flowing script of a man who dashed off handwritten thank-you letters most days of the week, as can be seen among the million items in the Churchill Papers.

Handwritten thank-you letters have made their mark in every civilisation. Persian Queen Atossa wrote the earliest surviving one in about 500 BC.

Before a national postage system and the launch of the Penny Black first stamp in 1840, the cost of receiving any letter had to be borne by the recipient, rather dimming the thoughtfulness of any thanks-giver.

By the 1860s, the penny postal system was booming. With up to 12 collections each day in Victorian London, you could

what is second-screen content?

Second-screen content is stuff you watch while simultaneously looking at your phone. According to one report by Google, three-quarters of British people – and 93 per cent of young people – now watch TV in this way.

Or should that be don’t watch TV? It’s more common to use, say, Keeping Up with the Kardashians as general room ambience, something to have on while you scroll through TikTok. Or a Premier League match as mood music while you place bets on other, more exciting matches. Nothing has our undivided attention any more.

Don’t shake your head. I bet you’ve become embroiled in the family WhatsApp as slugs mate slimily on Wild Isles. Or looked up an interesting rose varietal featured on Gardeners’

write to thank your hostess of the night before, sprinkle the note with lavender water and have her reading it, scent still fresh, by the time she sat down to midmorning coffee. Even with the invention of the typewriter in 1868, it remained infra dig until well into the 1930s to type any personal correspondence, perhaps especially a thank-you letter.

As a nation, we used to write thankyou letters for everything: a Christmas present, a dinner party the night before, or even just a thank-you for a little favour. Like the simple two-liner from Marilyn Monroe to a German swain in 1962: ‘Thank you for your champagne. It arrived, I drank it and I was gayer. Thanks again. My best, Marilyn Monroe.’

Nowadays, most people under the age of 30 wouldn’t know how to start tackling a handwritten thank-you letter. My 21-year-old daughter would, because she had a cruel and unusual mother who forced her to sit down every Boxing Day and write to thank relatives. The main

rule was to ‘get over the page’. As a result, she has beautiful, huge and loopy penmanship.

In 2022, an M&S poll showed that only nine per cent now send handwritten thank-you letters, compared with 20 per cent ten years before. Email, WhatsApp, SMS and other digital methods have erased the pen. There are even apps that can now ‘hand-write’ for you.

Still, in a busy world, that same 2022 poll showed we are ever more alive to the ‘pro-social wellbeing benefits’ of gratitude. What says thank you more eloquently than the ritual of finding paper/ card/ envelope/ stamp/ pen, crafting your best copperplate, sprinkling some wit and sincerity, getting over the page, sealing it with a loving kiss and walking to the post box?

InApril, when the price of a stamp went over £1, the final writing was on the wall for the posted thank-you. Still, consider the investment. £1 and a few minutes’ writing to thank someone for a gift will reap exponentially better presents from the giver in the future.

Susannah Jowitt

World, only to become lost in the thorns of Instagram. Or perhaps you cannot watch Question Time without tweeting about how annoying Fiona Bruce is.

It’s not your fault. The finest minds of a generation have worked extremely hard so that we all exist in a state of permanent distraction and are thus more susceptible to their malign moneymaking schemes.

It’s surprising just how invested many TV producers are in the idea of this multi-front assault. You’d imagine that if you were, say, Netflix, you’d want people to watch Netflix. Apparently not. ‘What the streamers want most right now is “second-screen content”, where you can be on your phone while it’s on,’ one screenwriter complained to the New Yorker recently.

She is one of thousands of Hollywood TV writers who recently went on strike in America over low pay, intolerable

conditions and a general feeling of being messed around.

The so-called Golden Age of TV that produced high-quality shows such as Mad Men and Game of Thrones is over. The streamers have figured out that most viewers don’t want novelistic complexity. They want something that isn’t too hard to follow, while you’re bidding on eBay or completing a Wordle.

That’s why the streaming giants (Netflix, Amazon Prime, Apple TV, Disney+ etc) pay top dollar for classic 1990s shows such as Friends, Seinfeld and The Simpsons. And it explains innocuous Netflix fluff like Emily in Paris. It’s non-event TV. It’s ambient TV. It’s second-screen content.

Meanwhile, you just know some Californian money man is currently looking at those striking screenwriters and wondering, ‘Why not get AI to do the writing and be done with it?’

Richard Godwin

12 The Oldie June 2023

JASPER

/

Good manners: Marilyn

CHAMBER

ALAMY

We used to love people talking rubbish, from Edward Lear to Monty Python. It’s time for an absurd revival, says Piers Pottinger

Do talk nonsense

Throughout history, the British have revelled in nonsense.

In 1846, Edward Lear published A Book of Nonsense, which captured his readers’ imagination. Lewis Carroll wrote the most famous nonsense poem, Jabberwocky, in 1871.

Almost a century later, in 1948, Stefan Themerson founded an eccentric publishing firm, Gaberbocchus. He maintained this was the Latin rendering of Jabberwocky. He published the first English translation of the absurd play Ubu Roi by Frenchman Alfred Jarry, which sadly appealed only to a tiny audience. Stefan remained loyal to all forms of nonsense until his death in 1988.

In the 1960s, nonsense came into its own, championed by the great Spike Milligan. Oldie-readers will fondly recall The Goon Show, the epitome of radio nonsense. Spike had more to offer with his seminal Silly Verse for Kids, and his brilliant television adaptation of The World of Beachcomber, featuring Dr Strabismus and the Filthistan Trio, which consisted of three ‘Persians’ and a plank.

Strabismus would try to test the truthfulness of proverbs: for example, ‘When one door closes, another opens.’ He set up 30 front doors in a field, closing one and waiting for another to open. It never did.

I loved the actor Michael Redgrave declaiming random names from the weekly list of Huntingdonshire Cabmen. Sadly, only one episode of this wonderful series still exits, and it hasn’t been shown of late.

Stanley Unwin (1911-2002) invented a nonsense language, Unwinese. It featured in many television programmes, even in Carry On films. He claimed he had learnt his unique gobbledygook from his mother, who would talk of ‘falolloping’ (falling) down the stairs and grazing her ‘kneeclabbers’. Unwin continued talking nonsense as a career into his 90s.

In 1963, Michael Codron produced a show at the Comedy Theatre called An Evening of British Rubbish, featuring a custard-pie machine and an Oriental orange joke. It ran for a year and featured the great duo the Alberts.

Bob Blackman (1926-96) had a unique

act, singing Mule Train while repeatedly hitting himself on the head with a tin tray. That was it.

I once spoke to him, after he’d given the act up. Many years of battering his poor head had caught up with him, and he was forced to look for something new. He told me he had created an act where he climbed a stepladder he’d set on fire, singing I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles. Sadly, this act never made it to the stage.

One of the most nonsensical people to bring us joy was the self-styled Prince Giorgio Carbone of Seborga (1936-2009). He declared Seborga, a village in Italy with a population of 247, to be a legitimate principality, citing evidence from 954 AD. Carbone was in fact a florist from the village, but he awarded himself the magnificent title of His Tremendousness.

The villagers endorsed him, and the previously unknown Seborga became a minor tourist destination, generating good local income. Carbone received an annual sandwich and a weekly coffee in recognition of his service to the community. He was my favourite example of glorious nonsense.

Monty Python began to build its huge following in the late sixties with sketches full of magnificent nonsense, still revered today.

Then we waited until 1990, when Reeves and Mortimer’s Big Night Out gave us a proper dose of hilarious nonsense. Regular features included the two ginger-haired aromatherapists

whose catchphrase was ‘You have to smell to be well’. It initially baffled the Channel 4 viewers, but soon won an enormous following, leading to ever more memorable programmes including Shooting Stars

On the radio, Count Arthur Strong, created by Steve Delaney, first appeared in 2005. Despite threatening retirement, he will be touring British theatres in 2024. The BBC have abandoned him, but he remains a popular peddler of ludicrousness.

After Carroll, Lear and Milligan, it is hard to think of great examples of nonsense in literature today, or even in the theatre or television (Count Arthur Strong apart).

In architecture, there are plenty of visible examples. The tradition of the folly is alive and clearly evident in many great British gardens, as well as in Italy, where the tradition goes even further back. The Sacro Bosco, featuring the Villa of Marvels in Bomarzo, Lazio, was created by Prince Vicino Orsini in 1552. It fell into neglect for many years until surrealists such as Salvador Dali rediscovered this most bizarre of follies and heralded its revival and restoration.

Today, nonsense is more obvious and less funny in some of the wokery we all endure. It is normally political and, more often than not, polarising. There is little pure nonsense to raise a smile.

Isn’t it time for a nonsense revival?

The Oldie June 2023 13

MIRRORPIX

Piers Pottinger is a public-affairs consultant and funster

Shut up, Eccles! Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe rehearse The Goon Show, 1963

Loose Cannon

Is there anything quite so melancholy as a bereaved straight man, soldiering on as a solo turn after the funny half of the double act has died?

Ernie Wise cut a lonely figure after Eric Morecambe died – and Tommy Cannon, without Bobby Ball beside him, I feared might be much the same.

I needn’t have worried. It’s nearly three years since Bobby died, aged 76 (a cruel combination of pulmonary disease and Covid). Though Tommy still misses him terribly, he seems content and self-assured. His bright eyes twinkle with fun and laughter – he wears his 85 years lightly.

Still, it’s impossible for me (and countless other Cannon & Ball fans) to meet him without thinking about Bobby. I’ve met Tommy twice before, both times with Bobby, backstage in Blackpool and Skegness, and both times they were hilarious. Bobby was like a big kid; Tommy was like his elder brother.

Meeting him this time in York (where he lives with his second wife, Hazel – the mother of three of his five children), I find he’s still terrific company. But I can’t help staring at the empty space beside him where his double-act partner ought to be. ‘Sixty years together – it’s like a marriage,’ he tells me.

Tommy always thought he’d be the first to go, simply because he was six years older. ‘I can never forget him. He’ll always be in my mind. I’ll always be thinking of him.’ Sometimes he watches old clips of their act on YouTube. ‘I sit there, and I think to myself, “My God, you were so damn funny.” ’

He’s currently preparing a one-man show – quite a challenge for someone who spent over half a century as half of one of Britain’s best-loved double acts.

He’s not a natural comic, like Bobby (‘He’s always had funny bones,’ says Tommy, slipping into the present tense), but I’m sure he’ll make a success of it. You’d want to spend an evening with him – and from September

you’ll be able to, in An Evening with Tommy Cannon.

‘When Bob passed away, I was sort of at a loose end,’ he says. ‘And then suddenly I thought to myself, “I can do the life story of Cannon & Ball.” How we met, how hard it was in the early days…’ It sounds like a great idea for a show.

Thomas Derbyshire was born in Oldham in 1938. ‘It wasn’t the best place – it wasn’t the worst by a long way,’ he says, stoically – but to me his childhood sounds positively Dickensian. His dad was a miner – he left home when Tommy was six. His mum worked in the local mill, ten hours a day. ‘The noise in the

cotton mills was horrendous – she was stone-deaf,’ he says. ‘They were hard days.’

Tommy was an only child. Their house (‘a one up, one down’) was next door to the Yorkshire Penny Bank. ‘Don’t worry, Mum,’ he told her. ‘I’ll rob the bank some day and we’ll be rich.’

When his mum remarried, his stepfather moved in, bringing four children with him. ‘Tin bath, outside toilet – all them people in that house was a nightmare.’

Kind neighbours used to give him broken biscuits. ‘Everybody was an auntie or an uncle – there was a lot of lovely, warm people, but there were also

14 The Oldie June 2023

Three years after Bobby Ball died, Tommy Cannon, his bereft comedy partner, is back on stage. He talks to William Cook

ITV/SHUTTERSTOCK

a lot of people who were hard, because they had to be.’

Education was no respite. ‘I was Tommy Thicko at school,’ he says. ‘I had dyslexia, which was unheard of in them days – the only thing that saved me was sport.’

His PE teacher predicted he’d be a professional footballer, but it never happened. He left school at 15, drifted from job to job (‘I went down the pit for two weeks – it petrified me’) and ended up welding in a local factory, where he met an infectiously funny bloke called Robert Harper.

Bobby had always been an entertainer. When he was a kid, he appeared on the hit radio show Workers’ Playtime, with his sister. Now he was playing local pubs and clubs. He asked Tommy along, they hit it off, and Bobby asked him to join him and form a double act.

‘Aye, all right,’ said Tommy. He didn’t take it too seriously. He thought it might be a way to earn a bit of extra brass.

Unlike Bobby, Tommy had never considered a career in showbusiness. Before their first gig together, he was so

nervous that he threw up in the dressing room. He never could have done it on his own, but Bobby’s confidence sustained him, and he soon discovered, to his surprise, that he had a lovely singing voice. Playing the northern clubs night after night with Bobby was a great way to learn the ropes.

They started off singing ballads, but the banter went down better than the songs. So they ended up as comics – on the club circuit, comedians got more money. Tommy’s deadpan delivery made Bobby’s clowning twice as funny. Renamed Cannon & Ball, the act finally took off. After a week’s booking at a club in Wales, they decided to give up welding and go full-time. It was the first time they’d left Lancashire.

Playing those working-men’s clubs was the toughest (but by far the best) apprenticeship.

‘They were hard men,’ says Tommy, but if you could please them, you could please anyone. ‘You’d have an audience come in at lunchtime which would be men only – they’d be very judgemental.’

If they came back in the evening with their wives and girlfriends, that was always a good sign. ‘But there were many, many times when we didn’t even see the evening performance, because we got paid off.’ They died loads of times but, as Bobby used to say, if you don’t die, how are you going to learn?

They finally got their own TV series in 1979, after 16 long years in clubland. Tommy was already 40. They both had wives and children. By now they were earning two grand a week playing the clubs – so they weren’t desperate for stardom.

They came across as two old friends having fun together, and the punters lapped it up. In 1980, they sold out

Blackpool Opera House: 3,200 seats, two shows a day, for 18 weeks. There was nothing innovative about them, but they understood their audience and they had the common touch. ‘We termed ourselves as a working-class act.’

Cannon & Ball were peak-time TV stars throughout the 1980s. ‘Twenty million viewers, every Saturday night –there weren’t a lot of stations, the way there is now.’

When the TV career tailed off, Tommy and Bobby went back on the road again. I saw them live a couple of times and they were fantastic. The jokes had beards, but no one cared. Like all good double acts, it was about the relationship between them.

The thing that made them so popular was their empathy with their audience. ‘Most of the people who grew up with us came from a similar background – there was always a warmth from an audience for me and Bob.’

Like Morecambe & Wise, their act was fuelled by affection – for their fans and for each other. Viewers felt they knew them. They were the last sentinels of a bygone age, when comics could still draw on a common pool of shared experience. We shall not see their like again.

Of course, seeing Tommy performing on his own won’t be the same, and he isn’t pretending otherwise. ‘I haven’t got funny bones – I haven’t. I wish I had, but I haven’t.’

He’s too modest. It will be an uplifting, life-enhancing show and, in these fractious times, that’s a blessing. I’ll be in the stalls, loving his happy memories of Bobby. See you there.

An Evening with Tommy Cannon is touring, 21st September 2023 to 11th May 2024

The Oldie June 2023 15

Solo act: Tommy Cannon, 84, today

The way they were: Tommy Cannon (left) and Bobby Ball in 1990

Writer Roger Deakin belonged to the lucky generation, who missed national service and rejoiced in 1960s freedom. By

Patrick Barkham

Born to be wild

The train that carried Roger Deakin from London to his Suffolk farmhouse passed his four small fields before stopping at Diss station, five miles north.

With his advertising executive’s gift for persuasion, Roger persuaded the driver to slow down on the fast straight outside his home, so he could hop off at his own personal request stop.

Like so many of his generation, Roger made the most of his freedoms. He is best known today for Waterlog, an entrancing account of swimming via rivers, lakes and lidos through Britain, beginning in the spring-fed ‘moat’ beside his house.

Published in 1999, it has become a nature-writing classic, and a compelling assertion of the individual’s freedom to swim in Britain’s (often private) rivers.

Roger would’ve been 80 this year; he died of a brain tumour in 2006. He was a notable member of a memorable generation who missed national service by months, came of age just when the Lady Chatterley trial and the Beatles invented sex, and then enjoyed postwar prosperity, affordable property and accessible global travel.

What fortune! What freedom! But Roger’s life shows how liberty had to be fought for.

Unlike today’s specialists, Roger was a generalist in an era when it seemed possible for anyone (at least those with ‘acceptable’ accents or skin colour) to turn their hand to anything.

The one constant in his life was a notebook in which he jotted poetry and philosophy. On visiting the wealthy family of one ’60s girlfriend, he observed of the ‘Churchillian’ father, ‘My God – what a huge difference between our two generations – complete chasm!’

Looking back, I think his generation could be the most distinctive that ever lived. In retrospect, the social and cultural transformations they engineered appear inevitable, but at the time there was no guarantee of success. It’s never easy to shrug off decades of ossified ways of doing things.

Roger was born in Watford, the bright, only child of a railway clerk and a secretary. With London on one side of his modest bungalow and countryside on the other,

he ran wild through fields and copses. He hated confinement. Even so, he had to run home for tea when his mother stood in the garden and rang a bell.

The state paid for a scholarship to Haberdashers’ which led to Cambridge and then to copywriting in Soho just as London swung. Plenty of voices still demanded conformity to old norms, but Roger embraced the new rebellion, growing his hair long and rejecting suburbia and the traditional family. He set up home with an extended ‘family’ of friends in a cheap rented flat in thenshabby Queen’s Gardens.

Roger could’ve stuck with a conventional advertising career but there were so many other freedoms to enjoy.

He moonlighted by scouring rural auction houses for stripped pine,and imported pottery from La Bisbal in Spain, whither he sped on fun-filled adventures in his open-topped Morgan.

He inveigled flatmates into helping him upcycle kitchen chairs into rocking chairs, selling them to the ‘trendies’ on Portobello Road market. His notebooks record one sale to Judi Dench.

There was sexual freedom, too. The pill was ‘the greatest invention of modern science – along with penicillin!’ enthused 24-year-old Rog in a 1967 notebook. He married (and had a son) but his freedom-

seeking didn’t stop, and an affair ended his marriage.

While his freedom-seeking made for glorious beginnings to relationships, his refusal to countenance constraints – or compromise – created romantic turmoil. Freedom had its cost.

In 1972, Roger devised the National Coal Board’s ‘Come Home to a Real Fire’ campaign (a slogan gleefully adopted by second-home-scorching Welsh nationalists of the day).

But he remained a maverick, who illicitly kept live chicks in his agency’s basement screening room and swanned off to his Suffolk farmhouse when he should’ve been at work.

Like many of his generation, he seized the opportunities provided by cheap property, restoring the ruined 16thcentury house he’d spied in the summer of ’69 and persuading the farmer to sell for £2,000.

After dabbling in self-sufficiency, he became an English teacher at the local grammar school. He played Joni Mitchell in lessons, organised classroom ceilidhs and, on discovering his sixth-formers couldn’t identify an elm, while teaching Howards End, spirited them out of school to admire one.

When school became too stifling, he became an early freelancer, devising Save the Whale! concerts for Friends of the Earth and co-founding a charity, Common Ground, which championed the local nature of hedgerows and orchards.

Later on, he made films and became a music impresario, bringing folk and rock to Benjamin Britten’s Aldeburgh Festival.

While researching Roger’s biography, I was inspired by meeting so many of his generation. It wasn’t simply age that liberated them to speak so honestly about the joy and pain of life alongside him.

Openness has become a habit of a lifetime. At 80, many of Roger’s friends are as vital, cussed, questing and freedom-seeking as they have ever been. They are worth celebrating.

More timid subsequent generations might learn something from them, too.

The Oldie June 2023 17

PETER

The Swimmer: The Wild Life of Roger Deakin by Patrick Barkham (Hamish Hamilton, £20) is out now

EVERARD SMITH

Free spirit: Roger Deakin (1943-2006)

Bruce Beresford mourns his friendBarry Humphries. Cartoon by Nick Garland

Goodbye, possums!

Ifirst met Barry in London in 1963. I’d seen his one-man show on stage in Australia, where he was already well known. Apart from a couple of appearances in small clubs, he had little reputation in London. He did odd jobs (as did I), including breaking old vinyl discs in a record factory.

He dressed conservatively in those days, usually in Edwardian style, with waistcoat and hat. Over the years, his ensembles became increasingly bizarre, with an array of brightly coloured jackets and trousers and, at times, painted shoes.

He never abandoned wearing ties, although in Australia men of all ages amble through city streets in shorts and T-shirts. The only men wearing ties are politicians and those on trial.

There is quite a bit of information about his early years (in fact, all his years) in the autobiographies he wrote: a couple as Barry Humphries (My Life as Me is superb), a couple as Edna Everage and one or two as Sir Les Patterson. I think that Les Patterson’s The Traveller’s Tool is the funniest book I’ve ever read.

It’s delightfully politically incorrect by today’s puritanical standards – probably by the standards of any era. My favourite chapter is ‘My Tool in Your Hand’.

Two books by Barry that I find myself constantly re-reading are collections of poems he values, both privately printed in exquisite binding: At Century’s Ebb (2008) and Poems I Like – an Anthology Responsibly Sourced (2021). Among the latter collection is a poem by John Cooper Clarke (the only living poet included), Things Are Gonna Get Worse

Two of the verses follow.

What, me worry? I should care, Shit for brains, wire for hair, I seen the future and I ain’t there, Things are gonna get worse.

Things are gonna get worse, nurse, Things are gonna get rotten. Make that hearse reverse, nurse, I’m trying to remember everything that I’ve forgotten.

During those years in London – the 1960s – I realised that Barry’s addiction to alcohol was a major career impediment. He amazed me by managing to deliver brilliant performances in Lionel Bart’s Oliver and Maggie May, as well as playing Long John Silver in a production of Treasure Island at the Mermaid.

I realised, when I went backstage one afternoon, that he’d managed to play Long John while totally inebriated, improvising dialogue which had the audience collapsing with laughter.

In 1972, Barry was visited, in hospital, by people from Alcoholics Anonymous after an incident in Melbourne where he was robbed by a couple of pub roughnecks and dumped by the side of a road. The AA people were persuasive –he never drank again.

His quick wit never ceased to astonish me. Edna’s endless bons mots on her TV shows were never scripted by a team of backstage writers but always produced by Barry on the spot.

In San Francisco, I once stayed with him for a week while he was doing a stage show. Every night, his wife, Lizzie, and I would go to pick him up. Invariably, I saw the last half hour or so of his show and was amazed that the jokes and situations – as well as the overall running time – varied considerably from night to night. There was a loose overall structure, but Barry’s irrepressible humour couldn’t be shovelled into a fixed time.

Last year, my wife and I went to York to see the stage show Barry was touring around England. In the dressing room, after the performance, Barry slumped into a sofa and said to me, ‘Why am I doing this, at my age?’

I replied, ‘Because there’s nothing you like to do more than go on stage, tell anecdotes and hear people laughing.’

I was struck, from the first time we met, at Barry’s incredible range of interests – apart from acting. He was fascinated by Oscar Wilde and the Sitwell family, particularly Osbert and

Sacheverell. He collected books, invariably first editions, and had a flair for unearthing many of the minor, or half-forgotten, writers and poets of the 19th and early-20th centuries. He knew every rare-book dealer in England – just as he seemed to know every art dealer.

His art collection must contain thousands of paintings, sketches and lithographs. The works are all figurative, all exquisitely painted. Many are tastefully erotic but, apart from Charles Conder and perhaps Jan Toorop and Jan Frans de Boever, there are few widely celebrated artists.

Barry had little interest in modern popular/punk rock/hard rock music, but admired Stephen Sondheim, Andrew Lloyd Webber and George and Ira Gershwin. He appeared on Broadway with the musicologist/singer Michael Feinstein, performing works by many of the great American songwriters of the 1930s.

He was also fascinated by the group of Weimar composers, among them Kurt Weill and Mischa Spoliansky, persecuted by the Hitler regime for their ‘degenerate’ music. His presentation of a number of the Weimar songs was acclaimed in Sydney and London in 2018.

His taste in classical music also tended to gifted but less acclaimed figures. He became friends with the Belgian composer Jean-Michel Damase, a distinguished pianist who composed melodic orchestral pieces. I met him with Barry. Damase, a quiet and gentle man, always seemed to me to be slightly puzzled by the admiration of the tall Australian actor.

Similarly, Barry was a fan of the German composer Ernst Krenek. Krenek’s music was also labelled ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis, which resulted in his wisely moving to America. He lived for some years in Palm Springs and died there in 1991. Barry visited Krenek a number of times in the 1990s and promoted his music in Australia – which led to his celebrated 1920s opera Jonny Spielt auf being presented in Melbourne in 2022.

18 The Oldie June 2023

NICK GARLAND

Barry was surrounded by – and friends with – many celebrities in England, America and even Australia. Unlike many famous actors, he was never obsessed with his own fame, though he appreciated its being responsible for the best table at restaurants.

His courteous, amiable manner was extended to everyone he met and everyone he worked with. Stage crews, as well as actors, returned to his shows for literally decades. In the Sydney hospital, he was visited by a group of Lesettes – girls from Les Patterson’s stage appearances many years previously. The hospital was inundated with phone calls from wellwishers abroad, among them King Charles.

One of my sons, Benjamin, has Down’s syndrome. He has known Barry all his life and saw many of his stage shows and,

of course, the two Barry McKenzie films I directed. When in England, Barry always remembered to contact him by phone or to visit him on the Isle of Wight. They had long conversations on Benjamin’s favourite topics: (a) Fawlty Towers; (b) the Beatles; (c) Some Mothers Do ’Ave ’Em; (d) Doctor Who.

Benjamin called me when he was told that Barry had died and said, ‘I cried when I heard.’

I’m sure that many people cried. I was somewhat taken aback at the outpouring of positive articles and TV coverage in Australia, as there had been so much talk over the previous year or so about Barry’s political incorrectness (!) and right-wing political views (nonsense!).

With his death – his loss – there has been widespread realisation of the extent of his genius.

Bruce Beresford directed The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) and Barry McKenzie Holds His Own (1974), both starring Barry Humphries.

The Oldie June 2023 19

Nicholas Garland illustrated the Barry McKenzie cartoons in Private Eye, written by Barry Humphries

Dame Edna Contemplating a Bust of Barry Humphries by Garland – after Rembrandt’s Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer. Below: Garland and Barry by Barry, 1970

Barry’s last words

For 40 years, Barry Humphries wrote to Roger Lewis about John Betjeman, Oscar Wilde – and the Grim Reaper

I’m getting to be like John Gielgud, when he lamented, ‘All my real friends are dead’ – Michael Winner, Bryan Forbes, Barry Cryer and now Barry Humphries.

I knew Barry for about 40 years, ever since I interviewed him for a colour supplement. We subsequently met in odd spots of his own choosing, such as the Freud Museum in Hampstead, where he reclined on the couch – or the National Galley in Wales, so he could point at a picture by Anton Mauve and remark on the coincidental use of mauve paint.

Served a meagre portion of pie in the cafeteria of a veteran car museum in Coventry, he said to the waitress, ‘Has news of my diet reached the kitchen?’

I miss him terribly – he was a sort of father figure, whose approval and admiration I always sought.

‘I enjoy all you put your pen to, whereas my maladroit sentences seem to announce my decline,’ he said to me once.

Far from it – his letters and (latterly) emails I will always prize, and was proud to receive. He also wrote, ‘We’re off to Australia on Wednesday and, like all old men going upstairs or opening the fridge, I can’t remember why.’

Usually, our correspondence revolved around artists and authors. ‘I used to haunt the Gotham Book Mart in the hope of getting a glimpse of Edward Gorey and instead I met Salvador Dali.’ Or ‘I went to Hove with John Betjeman to meet Bosie, who talked of the races. We couldn’t divert this stream of turf talk.’

Wilde often turned up in out chat. Barry didn’t appreciate Rupert Everett’s biopic. ‘It was all about the agony and

20 The Oldie June 2023

NEIL SPENCE

Barry Humphries at his Hampstead home, 2021

ecstasy of pillow-biting. A few of Oscar’s quips chucked in and a few totally apocryphal scenes, like in the pub where he sings The Boy I Love Is Up in the Gallery to a spellbound audience of Frogs in fancy dress. It’s shithouse.’

He was good at being caustic, like this on Victoria Wood: ‘The worst work I’ve ever done was when I was trying to be liked. I’m not good at it, but I’ve fooled a lot of people. Victoria was exceptionally likeable. That epithet would be a posthumous insult if it ever cropped up in my obituaries. So would be “delightful”.’

He was highly attentive to language: ‘Have you noticed the current modish word is “unprecedented”?’

Another expression he hated was “to be honest”, “perfectly honest” or “absolutely honest”, which Barry thought portended dishonesty, mendacity. ‘Oh and what about all those inclusive TV commercials? They are so conspicuously inclusive, you wonder why they don’t include Eskimos or Kalahari bushmen. Racism, I presume.’

Political correctness, of course, set him off. He’d not be told by anyone.

When he was notoriously cancelled by the Melbourne Comedy Festival a few years ago, he told me, ‘The Barry was always a silly name for a comedy award. Perhaps the Lezzo has a more accurate ring.’

He signed petitions in support of J K Rowling, who was in the soup with the transgender mob. ‘It is pitiful we have to go out on a very dangerous limb to defend the truth. By condemning the Stasi who excoriate JKR, we are now on the blacklist.’

Yet Barry never stopped working. There was, for example, what he called a ‘non-event’ with Rob Brydon at the Palladium, where he had to discuss his favourite cinematic comedy moments, introducing clips. ‘I can’t think of any, except the cabin scene in A Night at the Opera or the dwarf in Don’t Look Now. I thought the pram and governess scene in Battleship Potemkin might be risible and the green-chunder scene in The Exorcist.’

I recommended Shelley Winters swimming underwater in The Poseidon Adventure. ‘Thanks to you,

the subaqueous Shelley made an appearance,’ he reported the next day. ‘That Sheila can certainly hold her breath.’

During lockdown, Barry dodged the curfews and went to Cornwall, ‘to Zennor, where I fell off the cliff in March 1962. The helicopter rescue made the national news.’ All the rules and restrictions made him nervous. ‘Skulking about does make one feel a bit Jewish, like dodging the patrols in Vichy France.’

He never liked the sound of Hastings, where I’ve lived since 2018. ‘What’s at the end of your pier? A derelict theatre? A palm-reader? Michael Kitchen and Honeysuckle Weeks? It’s not for you, Roger. You might bump into Inspector Foyle, but otherwise it’s a depressing place, like all those other sinks on the South Coast, full of cheap B and Bs and whiffy retirement homes, reeking of old roasts, cabbage and rarely changed Depends … You’d be better off in Sidmouth.’

He then added, ‘Sydney Harbour looks very grey this morning – so I think I’ll give Larkin’s letters a miss.’

Then, in January, the bad news came. ‘God has touched the pause button on my life. Various ills and inconveniences have assailed me since before Christmas. I ended up in Sydney being devoured by an enormous Siemens scanner. The company that funded Hitler’s election had discovered tumours in my spine.

‘This desolate news is just for you. I felt somehow I should tell you. They have zapped me, and the doctors are hopeful. I’m surrounded by little nurses from Galway and Manila. The doc says I can’t go back to London until late March, but who’d be in a hurry to go back there anyway?’

In April, he said, ‘Just entered my fourth month in hospital. They say I’m nearly out, but I’ve heard that before. I loll here like an odalisque watching old TV shows – London as it was a couple of years after I got there. Not much traffic, pretty and forgotten dolly birds, sideburns, flared pants and impossible baddies. Wonderful action stuff really performed by the actors.’

It got worse. I had a heart attack; he broke his hip. ‘I’m horrified to hear your desolate news. Now is not Our Time. What a pity we’re not in the same institution. The supernatural is all we have to rely on and it never lets us down and even if it does, we are completely unaware of it.

‘With love to you and dear Anna. Your bedridden friend, Barry.’

The Oldie June 2023 21

‘The worst work I’ve ever done was when I was trying to be liked’

A card for Roger, Dieppe Opera House, 1977

Neighbour from Hell

Mr Collins was a Victorian spec builder, responsible for thousands of redbrick villas in north London’s Metroland. One of them, since 1981, is ours.

The Mr Pooters of the 1890s were proud of their vernacular features: lofty, corniced ceilings, pillared porticos, stained glass, marble fireplaces, Puginesque tiled floors.

Having a large family, we needed the space. After stripping the hall wallpaper, we found the pencilled draft of a notice:‘This House can be completed in 10 days. Decorations to suit Owner or Tenant. Apply J Collins, Athenaeum Court, Muswell Hill, N.’

We chose our Cole & Son wallpapers according to the precise date: 1896.

Sadly, no such respect had been accorded the detached houses that had stood across the road until 1969. They had been replaced – pre-‘conservation area’ label– by a high-rise block, Eleanor Rathbone House: flats for 62 elderly Jewish refugees.

Miss Eleanor Rathbone, Independent Labour MP from Liverpool, championed Holocaust survivors. In her name, this chimney-like, monolithic, flat-roofed tower of pre-cast concrete panels had risen while residents watched aghast. Storey piled on storey: 12 in all, obliterating sunlight.

Visitors to our house would say, ‘Nice house – ghastly building opposite!’

Then, one day in 1987, I heard that its architect was still alive: Walter H Marmorek, aged 75, from Vienna. He agreed to an interview for my Sunday Times column –àpropos the Prince of Wales’s ‘monstrous carbuncle’ views.

He was absolutely charming and so was his historic office in Gray’s Inn Square, its date etched in stone on the lintel over his door: 1667. But above his desk was a framed image of his monstrosity, photographed from the south: pristine white, gleaming in sun, amidst trees. Nothing like our rear vision

of its damp-stained, grey concrete lift shaft, a blot on our landscape, visible for miles.

Dr Marmorek had never been back to see his handiwork.

‘This was how we built in 1969,’ he shrugged. ‘High, and economically.’ It came in within budget (£270, 487).

‘Did it please you as much as the 17th-century buildings around you now?’ I asked.

He laughed and said that was a leading question. He even said, ‘Architects have a disadvantage, compared with doctors. We cannot bury our mistakes.’

Quite. Reinforced concrete and galvanised steel in inappropriate places can’t be forgiven, like a passing, ugly fashion: they are unavoidably visible, for all time. Architects’ names should be prominently displayed on every building. ‘Si monumentum requiris, circumspice,’ says Christopher Wren’s epitaph (‘If you

seek a monument, look around you’). Today, we ask desperately, ‘Quis fecit?’

‘Who did it?’

Dr Marmorek sent me a Christmas card every year thereafter. The first residents of his building have all gone, as has he – aged 100, in 2013. He was childless but his legacy lingers.

Last year, the current owners, a property firm, started rebuilding the low-rise annexe to his original tower. Our objections to their planning application were fruitless. In came the bulldozers, diggers, scaffolders and flappingplastic sheets – a year of noise and disruption.

Two storeys are now five. So we watch as another featureless slab blights our life and blocks our view.

I hear the writer Robert Byron’s words: ‘Of all the arts, architecture is the nearest to the most people, affects their happiness most closely, obtrudes on their sight most often…’

22 The Oldie June 2023

For 40 years, Valerie Grove has lived opposite a modernist horror – and now it’s spawned an extension

Valerie’s view: Eleanor Rathbone House, London N6, built in 1969, plus extension

–

Why are accidents so amusing? Oliver and Matt Pritchett have the answer

I’ve often wondered what members of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) do for a bit of fun.

How rollicking are their Christmas parties? I am sure they are not a patch on the larks we have at SPoMA, the Society for the Promotion of Minor Accidents.

We were founded to celebrate the joy of grazes, bruises, trips, twisted ankles and barked shins, which can, let us admit, be funny to witness and even better to talk about later.

The black eye, the exaggerated hobble, the arm, in a sling or the larger-than-necessary plaster will always get the conversation going. It can be a particularly rewarding pastime for the elderly to share. A much better topic than, say, the unseasonal weather. You can always delight your friends with your swollen upper lip and the story to go with it.

My own special party trick is to squirt one of my pills from its blister pack, then spend a minute or so crawling round on the floor looking for it, bump my head on the furniture as I haul myself to my feet, then get a dizzy spell and lurch about the room. My ungainly skating across the kitchen on a stray ice cube, ending in a collision with the stove, has also been much appreciated.

Comedy would be all the poorer if there were no minor accidents. Life would be drab if no umbrella was ever blown inside out and no pedestrian was ever drenched by a puddle and a passing car.

I am not sure if a banana skin has ever actually upended a pompous gentleman, but there is still hilarity to be found when your (or someone else’s) flailing downfall is brought about by damp autumn leaves or a discarded slice of pizza on the pavement.

New members are always welcome at Mishap House, the headquarters of SPoMA. You will feel at home as soon as

you arrive in the quaint, dimly-lit, low-beamed and highly polished entrance hall and you are sure to get a warm greeting from our Hon Sec Mrs Hardacre, known affectionately to all as Butterfingers.

Membership entitles you to join in our many risky activities, such as pulling a muscle or stubbing a toe in the Tuesday Unfitness Class. Or you may choose just to have a relaxing drink in our licensed bar, Spillages, down the steep staircase in the basement.

On many occasions, you will hear the familiar sound of cutlery, plates, saucepans and assorted vegetables hitting the floor as Mrs Hardacre holds one of her ‘drop-in’ mornings.

And on the last Friday of every month, we celebrate Minor Burns Night, a ‘show and tell’ occasion for people who have blisters from their cooker or their iron. Noteworthy scalds are also a feature.

Join SPoMA today and get a free gift. For men, it’s the society’s tie with its attractive gravy, toothpaste and raspberry-jam motif. For women, it’s a stylish, leaky pen.

So take care – but not too much.

Oliver Pritchett wrote for the Sunday Telegraph for 40 years. His son Matt is the cartoonist on the Daily Telegraph

The Oldie Spring 2023 21

Dead funny

The Oldie May 2023 19 * Europe/Eire: £58; USA/Canada:£70; Rest of world: £69 To order your subscription(s), either go to www.subscription.co.uk/ oldie/o ers or call 01858 438791, or write to Freepost RUER–BEKE–ZAXE, Oldie Publications Ltd, Tower House, Sovereign Park, Market Harborough LE16 9EF with your credit-card details and all the addresses. Always quote code POLD0623 This o er expires 31st August 2023. Subscriptions cannot start later than with the October issue WHEN YOU TAKE OUT (OR GIVE) A 12-ISSUE SUBSCRIPTION FOR £49.50* SAVING YOU £13.50 BEAT THE PRICE RISE AND GET TWO FREE OLDIE BOOKS WORTH SPECIALBUMPEREDITION The Pick of the All-Time Best With an introduction by Harry Mount Annual 2023 CONTRIBUTORSINCLUDE:AUBERONWAUGH,WILLIAMTREVOR, MILESKINGTON,GILESWOOD,BERYLBAINBRIDGE,JANMORRIS, TOMCOURTENAYANDRAYMONDBRIGGS PACKED FULL OF CARTOONS £14.90

From the next issue, The Oldie will be £5.25 - still great value but it’s even cheaper if you subscribe

Bletchley reject

By Tim Whitaker

This spring, Bletchley Park celebrated World Poetry Day by recalling notable poets who served there. Among them were Herbert Read and Vernon Watkins, who turned their creative talents to codebreaking during the war.

One poet firmly rejected was Philip Larkin. Sixty years later, he’s still firmly persona non grata at Bletchley.

How Bletchley recruited staff remains a mystery. It was informal and eccentric – essentially down to whether you were ‘right’ for the job. Larkin should have fitted the bill – public school and Oxford, with intellectual and librarian attributes.

Larkin (1922-85) was at Oxford when his compatriots were enlisting in the services. Declared unfit for service on grounds of bad eyesight, he was left in a career quandary. The natural route was the civil service.

He applied as a ‘temporary assistant principal’, saying, ‘I don’t know what it entails, and I don’t much care … the job will probably be loathsome’.

Rejected, Larkin explained, ‘I’ve not got a civil-service job. I went for an interview, and I suppose they didn’t like the look of me. That’s fine, because I didn’t like the look of them either and had been dreading the arrival of some footling 9-6 job in an out-of-theway place.’

But Larkin made an impression.

Writing to Kingsley Amis on 1st September 1943, he revealed, ‘I got a letter on Thursday, saying I had not been recommended for appointment. This makes me think I must have offended them terribly in some way…

‘Soon afterwards, another letter came saying they had sent my name etc to the Foreign Office who wanted people for a branch – “40-50 miles from London”.

‘This will be hackwork of the worst order, I imagine, but there’s no interview attached to it – which is just as well, for at interviews I must obviously show them that I don’t give a zebra’s turd for any kind of job, and which militates against me.’

Explaining more to a friend, he wrote, ‘They have forwarded my name to the Foreign Office, who sent me a form to fill up this morning, enquiring what languages I knew. Ha ha. I’ve got a good mind to put Anglo-Saxon down. Trouble is, I don’t even know that.

‘Or perhaps I might arrogantly reply that a man who is master of his own language needs no other.’

Describing his Bletchley interview to Kingsley Amis, he said, ‘Anyway, I saw some Admiralty people who were very nice, and gave me teas and a cigarette, but couldn’t promise anything. Pity.

‘Then on Wednesday I went to Bletchley and heard about the work you do there. “Of course, yah’re workin against the clock all the tahm … one day orf everah seven … one week everah three months … Christmas, Eastah, Bank Holiday – they don’t exist… Billets … evah been billeted? No… Very difficult … overcrowded … spread out all ovah the countryside … special ’buses and trains to bring you in … we work shifts. 12-9, 9-4, 4-12 midnight. Think your eyes can stend workin’ by artificial light…

‘Salary £260 [the Admiralty had been £300 plus war bonus] min. We’ll let you know within the next few days.’

Larkin came away singularly

unimpressed, ‘I’m not sure I want to know. I think I should very soon want to go away from that place and not go back to it again. In fact, I felt like that when I went away from it on Wednesday. I felt that soon after I started work there, I should be put in a wooden box and lowered into a hole dug in the earth.’

His rejection spurred mixed emotions, outlined in a letter to Kingsley Amis: ‘The reasons for this gloom are several … they include receiving a letter saying that Bletchley doesn’t want me.

‘Now of course this is of course very fine as far as it goes: as I said before, I didn’t want to go to B, but there is something humiliating about being turned down a second time.’

Chased by the Ministry of Labour, Larkin landed a job as the librarian for Wellington, Shropshire.

When Larkin’s centenary was celebrated last year, I thought this story might interest Bletchley Park for its glossy magazine, Ultra. But this was clearly very much off brand.

My rejection letter stated there were ‘more positive and informative stories to include, instead of an article in which Bletchley Park is being described in such a negative way by a well-known poet, who only briefly visited the site’.

Worse still, ‘he fundamentally did not want to work here.’

We don’t have the notes from Larkin’s interview – only his letters. Of course, it’s the curmudgeonly Larkin with very contradictory views about work. But we’ll never know whether he’d have been a Bletchley success story, cutting years off the war.

For the time being, anyway, there won’t be a display board at Bletchley featuring him and other rejected notables.

Tim Whitaker is a member of the Larkin Society and the Friends of Bletchley Park. His mother served in Hut 3 from 1942 to ’44. Letters are taken from Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940-1985, ed Anthony Thwaite Enigma machine: Philip Larkin

The Oldie June 2023 25

During the war, Philip Larkin was keen to become a code-breaker. Despite his brains, he didn’t make the grade.

In the swim

How to build a swimming pool this summer for under £1,000.

By Matthew Faulkner

By Matthew Faulkner

Morning dips, leisurely lengths, reading on the lilo, evening cocktails… Everyone needs a swimming pool every now and then.

But even if you have the space for one, the installation costs can be punishing and the costs of heating the thing crippling. To add insult to injury, a swimming pool doesn’t even add much to the value of your house; a measly seven per cent according to commentators (much less than a tennis court, apparently).

Small wonder that what starts out as a good idea all too often ends up in the Maybe One Day file – and we opt instead for a fortnight abroad, where we can enjoy someone else’s pool with none of the downsides.

That’s what I thought last year – but then it started to eat away at me. ‘How hard can it be?’ I thought and, not being someone easily deterred, I set to it. What could possibly go wrong?

With wife and children indulgently rolling their eyes, I took the metaphorical plunge and contacted our local Man with Digger. We broke ground where once there had been a vegetable patch – three raised beds which over the years had produced scarcely so much as a potato salad and a few bowls of borscht. Even if the whole project were to fail, the veg would not be missed.

Half a day later, we had a hole in the ground. Not enormous, but long enough for a few good strokes, and the rest was left to me. Next, the heavy lifting of posts and railway sleepers to build up the sides.

A rough application of Pythagoras’s theorem ensured all the corners were right angles, more or less – easy enough – but keeping it level was more of a challenge. Without fancy lasers or even a long spirit level, water spilling off one edge was a constant possibility – and an infinity pool was not part of the plan.

Enter the water-filled transparent hose as a spirit level; a rudimentary device but accurate pretty much to the millimetre. A few bags of Postcrete and a

quantity of bolts later and it was done: square and level.

Keeping the water in the pool was something of a leap of faith. While you can buy a proper ‘bag liner’ for £800 or so, this went against the spirit of the enterprise. I went for a large, heavy-duty tarpaulin, the sort of thing you might use to cover a caravan, capped with a course of decking.

An assortment of carpet offcuts from the tip – some far too nice to be buried in the Dorset clay – provided essential protection against roots and stones.

And now for the tech bit. All pools need a plughole. The installation of a single pipe and valve did require a bit of head-scratching – once it was covered up, there would be no going back.

The local pool company sold me the necessary pipework for £50 or so, wishing me well and pushing their full-service brochures on me. I ignored these, totting up my savings while asking myself yet again whether all this was a good idea.

The cognoscenti will note with alarm the lack of filter and pump. True, without them there will be bugs galore checking in and not checking out. But the upsides are compelling: a few minutes every day with sieve in hand will revive your hunter-gatherer instincts and reacquaint

you with joys you last experienced when pond-dipping at school.