7 minute read

The Bomber Harris recipe

by The Oldie

The wartime head of Bomber Command was a dab hand in the kitchen, remembers his grandson Tom Assheton

The Bomber Harris recipe book

Advertisement

The Namib desert, south-west Africa: a young Arthur Harris, a former farmer and now a bugler in the 1st Rhodesia Regiment, tips liquefied bully beef from his ration tin on to the sand in disgust.

He vows to apply his practical mind to the problem of eating well in the military, once they have booted the Germans out of southern Africa. Victory duly came on 9th July 1915 at Khorab, after a gruelling desert trek. The campaign over, he decided to continue the fight in Europe, if he could achieve this from a seated position. There was no place for him in the cavalry – so he joined the fledgling Royal Flying Corps.

Eighty years ago this year, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris assumed his post as Commander-in-Chief at Bomber Command. For the next three years, he prosecuted, with the American 8th Airforce, the only direct action against the Nazi fatherland, until the Allies crossed the Rhine in March 1945.

More than 57,200 of his 125,000 men were killed. The Germans lost a great deal more.

How does a man take his mind off such matters, even for a few brief moments? Harris cooked. He chopped carrots, he constructed complicated sauces, he collected up his visitors’ ration books and co-opted the local butchers for the best ingredients. There were many famous visitors to Bomber Command throughout this period, from King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to politicians and military commanders (British, American and even Charles de Gaulle – although that didn’t go so well).

Harris would show his guests the Blue Books, photographic evidence of the damage being inflicted on German cities

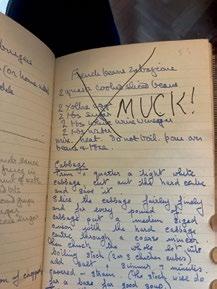

Bomber’s surprise: pages from the recipe book, recently rebound

and industrial sites. Many of them also dined at his table. Of course, Harris was too busy to cook himself, but his chefs were familiar with his interventions and direct action in the kitchen. He was at heart a practical man.

Harris’s daughter, my mother, Jackie, also experienced his ‘direct action’ at Winkfield Place in the late ’50s, under the stern eye of Constance Spry and Rosemary Hume. Harris would turn up early at the college to collect Jackie, so that he could make a round of the kitchens where the girls were learning to cook. Spry and Hume adored him, and his interventions were enjoyed by all, except for my poor, embarrassed mother.

They eventually awarded him his own Cordon Bleu certificate – after he posted them a cooked sausage.

Harris’s recipe book, with additions from my grandmother and mother, has recently been rebound. This encouraged me to take a closer look.

It is leather-bound, indexed and almost pocket-sized. Harris hated to write and so most of his recipes are in his wife’s hand. He spent time between the wars in Africa, India and Palestine, which gave him a love for spicy dishes.

He enjoyed messing about with complicated recipes. I have some of his cookbooks, too, and his margin notes are funny and sometimes quite rude. ‘Muck’ is a favoured term (as pictured above).

My sisters and I knew him when he lived at Goring-on-Thames, from the ’60s to his death in 1984, aged 91. He was known to us as Pappy and we to him as ‘the Monkeys’. He liked snacks (although he loathed that word). On one occasion, he sent my sister and me on the train to buy all the Frazzles in Reading. He was a big man, with the same neck-collar size as his bull terrier. We would weigh him on the scales at the train station.

There are far greater experts than me on the strategic bombing offensive of Germany in the Second World War. Listen to episode 28 from my podcast, Bloody Violent History, if you want it from the horse’s mouth. We knew Harris as

our large and entertaining grandfather. Tough, funny, practical and kind.

And there were many examples of the last of these. My mother’s godfather, Squadron Leader Peter Tomlinson, crash-landed his Spitfire in Holland in 1941, while on a photo reconnaissance mission for Bomber Command. He spent more than three years as a PoW in Stalag Luft III (his brother, the actor David Tomlinson, played a main part in the 1950 escape movie The Wooden Horse, set in this camp). The final act of his internment was a gruelling deathmarch west, forced by the retreating Germans, to avoid the Soviet advance.

By the time he was repatriated to England, Tomlinson was starving and ragged. He phoned his old station at High Wycombe, the headquarters of Bomber Command, and asked to be put through to his boss. Harris took the call and told him he had had a plane standing by to collect him from Europe but that he was now to wait at the station.

Harris sped off in his Bentley, having first left instructions for a welcome-home feast to be prepared for the returning hero. Harris knew Tomlinson would be in bad shape, his stomach shrunk from three years of virtual starvation in the camps. The ‘feast’ prepared was two boiled eggs with toast soldiers. Harris was both practical and kind.

Before lunch, Harris would sometimes tell us stories of animal adventures in India and Africa. Part of his ability to cook had developed from collecting ingredients for the pot with a rifle.

But his stories were more entertaining than tales of hunting lion. He had a lion cub as a pet. When it got too big, he gave it to the not-so-great King Fuad I of Egypt, who put it in the zoo in Cairo, and later had it shot.

Lunch from the Bomber Harris recipe book

Our first course: Swedish curry soup Sour apples, white onions, ‘heavy’ cream and curry powder. Lauren Clement, the chef, gave it a tweak by adding a delicious sourdough crouton topped with caramelised baby onion, pickled green apple and edible parsley lace

Entrée: monkfish and prawns in a red chilli sauce Very unusual and delicious sauce for an Englishman to make and enjoy 70 years ago

Veal cutlets ‘Old Bossy’ It turns out Old Bossy refers to my grandmother, who was sweet, very beautiful and more than 20 years younger than her husband. A rich, theatrical dish with a flambé finale

Navarin of Lamb An unctuous classic: use the best end of neck – important

And, for pudding, a little lemon pot from my mother’s repertoire

Left: Jackie Assheton with son, Tom. Above: with parents, Arthur & Jilly Harris, 1944

In India in the early ’20s, Harris had a ragged squadron of Bristol F2 fighters to chase the tribesmen up and down the North-West Frontier. He also had a pet Himalayan bear called Baloo. It’s a long story – that’s how we liked it (my poor grandmother). It ends atop the High Commissioner’s best apricot tree with the bear at the summit, Harris in pursuit in his now ruined cricket whites and the Commissioner’s sweeper boy with a bite on his bare bottom – cue weak bear puns.

Lunch would be heralded not by a dinner gong, but by the romantic twang from a six-foot-tall music box in the hall, playing the Intermezzo from Cavalleria Rusticana. It’s something of a Pavlov’s bell in our family to this day.

The Harris recipe notebook is kept in my mother’s kitchen. Recently rebound, it has stirred an interest throughout the family. Harris was never one-dimensional. The variety of recipes is a clear demonstration: Canadian yellow-pea soup, tripes à la Dauvillaire, coupe Caprice, coulibiac and bobotie.

We took a dip into the rich choice of recipes with a lunch at my home in Stockwell. The glistening faces of Harry Mount (The Oldie’s editor), James Pembroke (The Oldie’s publisher), my mother and James Jackson, the copresenter of our military podcasts, did the great man’s hearty appetite justice.

Plates were wiped clean; I was surrounded by ‘good doers’. Harris approved of a ‘good doer’.

And from my seat I could see, on a kitchen shelf, the rusty remains of one of those tins of bully beef from the Namib desert. The catalyst to Bomber’s lifelong pursuit of eating well.

For copies of recipes, email Tom on talk@bloodyviolenthistory.com