GILES WOOD ON CLASS

My train rage – Maureen Lipman I’ll miss the calm, kind Queen – Roddy Llewellyn Britain’s funniest man – Craig Brown by Robert Bathurst

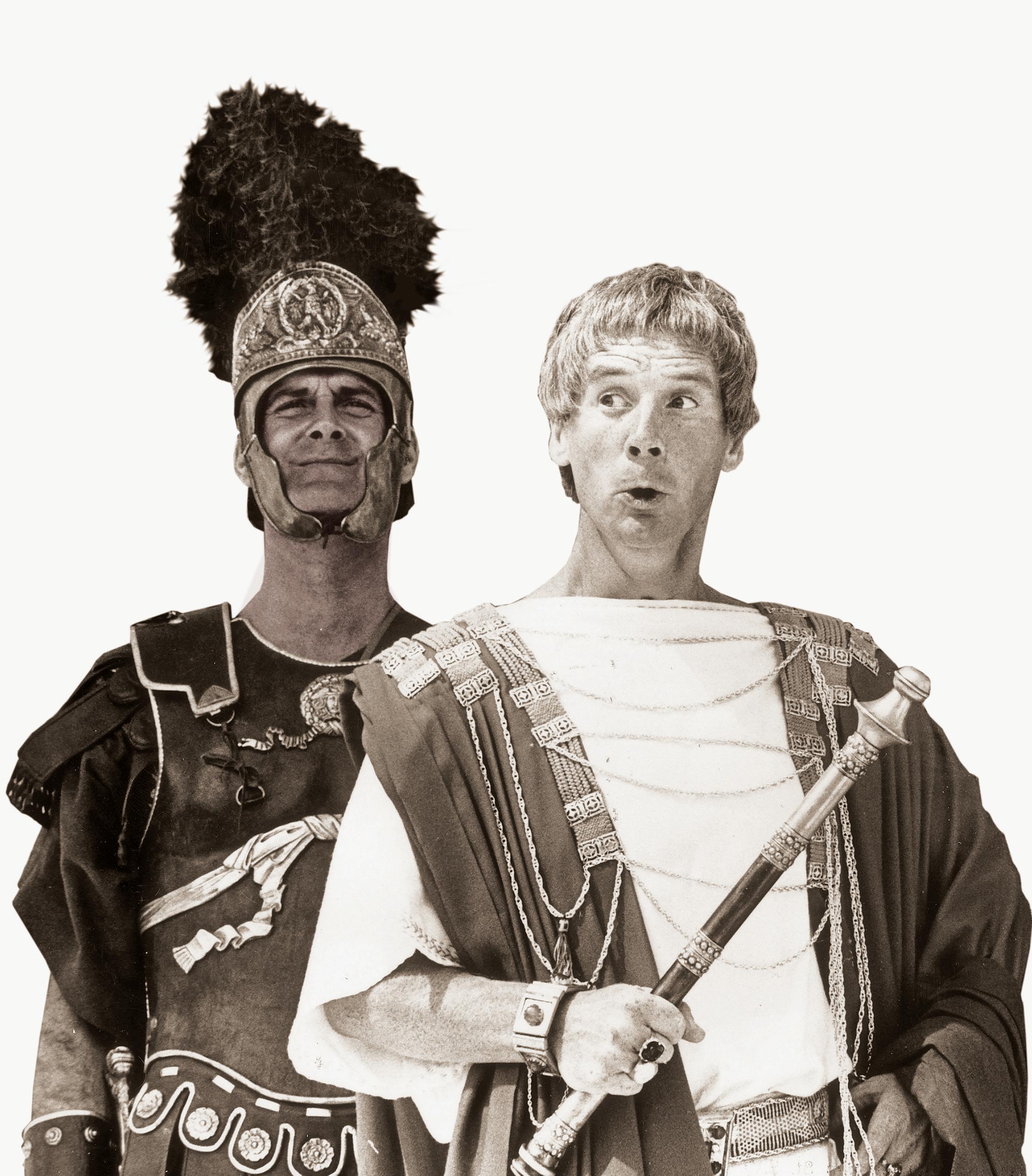

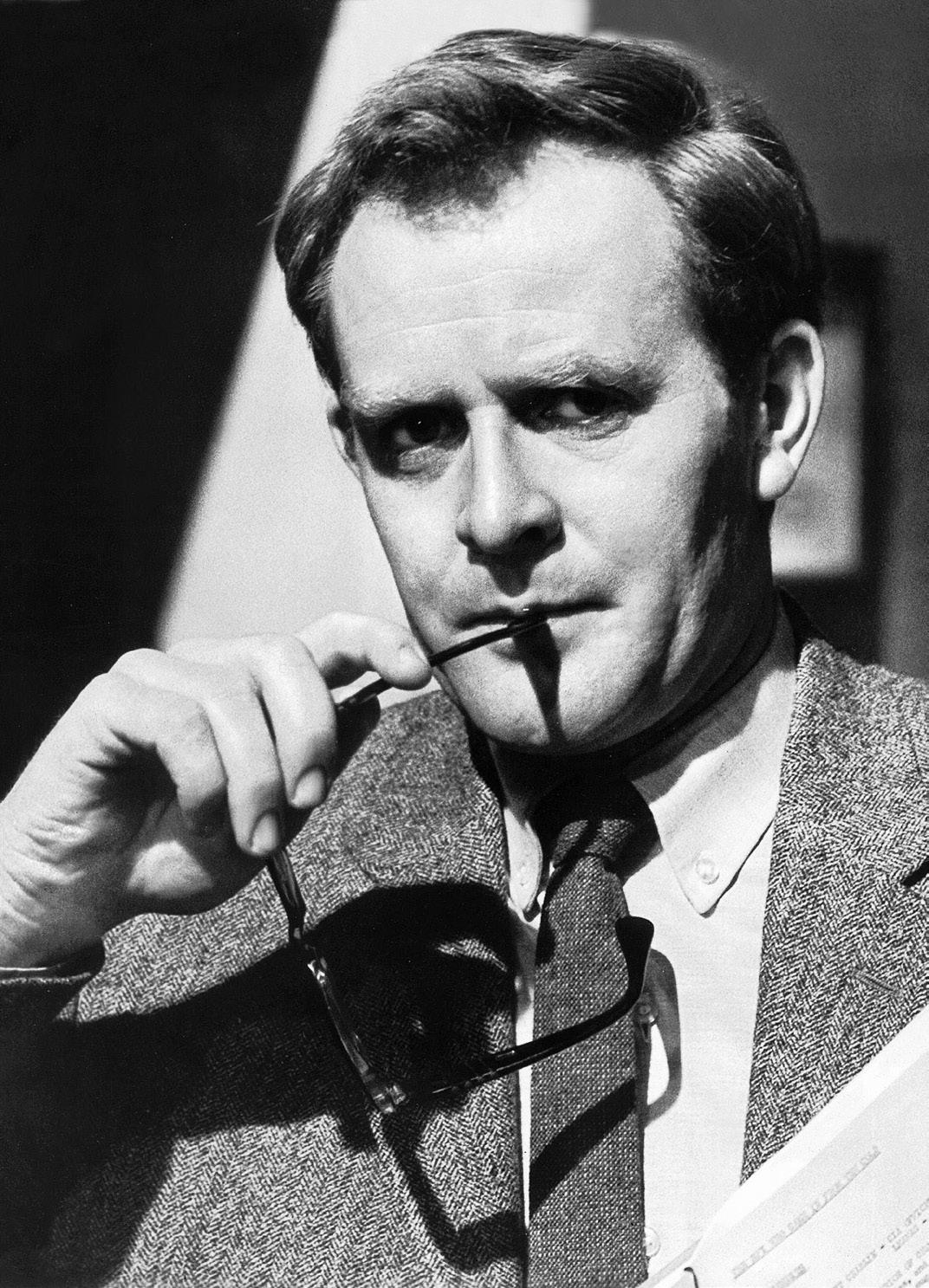

Roger Moore’s comic genius by Andrew Roberts The Saint at 60

My train rage – Maureen Lipman I’ll miss the calm, kind Queen – Roddy Llewellyn Britain’s funniest man – Craig Brown by Robert Bathurst

Roger Moore’s comic genius by Andrew Roberts The Saint at 60

Joy of eccentrics Andrew M Brown

The Saint and Dr No turn 60 Andrew Roberts

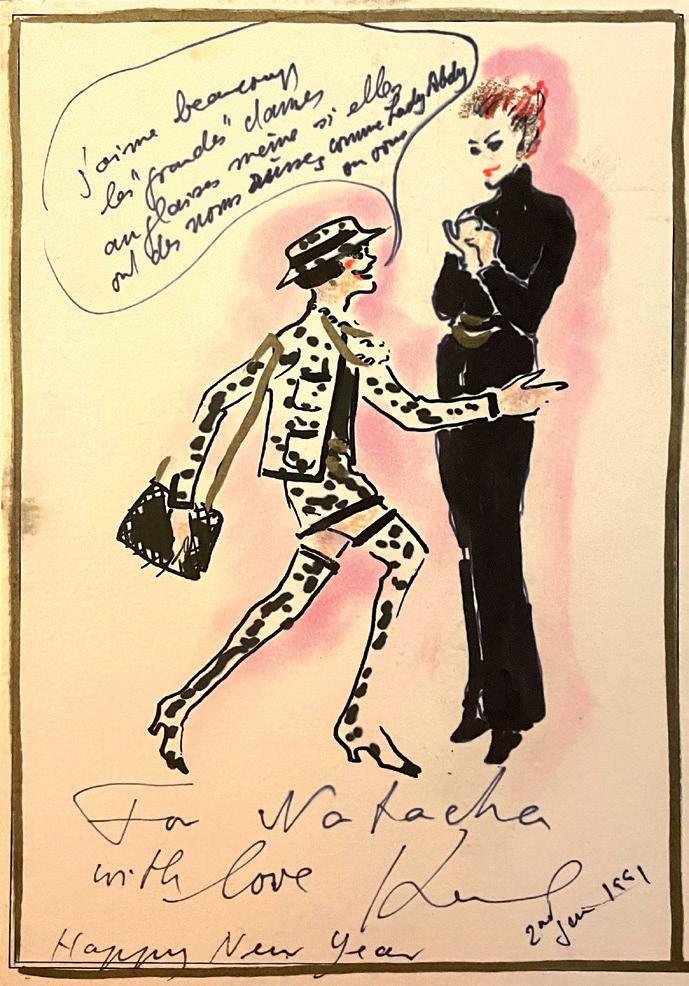

Karl Lagerfeld, my heavenly boss Natasha A Fraser

Long live Latin! Harry Mount and John Davie

A son’s suicide Cosmo Landesman

Coleridge’s new statue Drew Clode

Show-off oldies Oliver Pritchett

Allotments are good for you Victor Osborne

The spy who shocked le Carré James Hanning

Failed fogey Henry Oliver

Vera Brittain’s lost letters Mark Bostridge

The Waste Land turns 100 A N Wilson

The Old Un’s Notes

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

Grumpy Oldie Man Matthew Norman

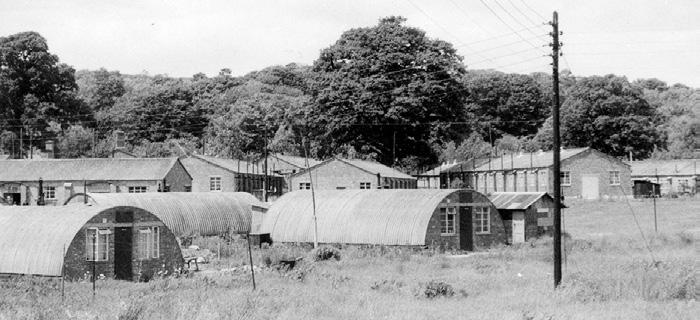

Olden Life: What were Polish resettlement camps? Liz Hodgkinson

Modern Life: What is BeReal? Richard Godwin

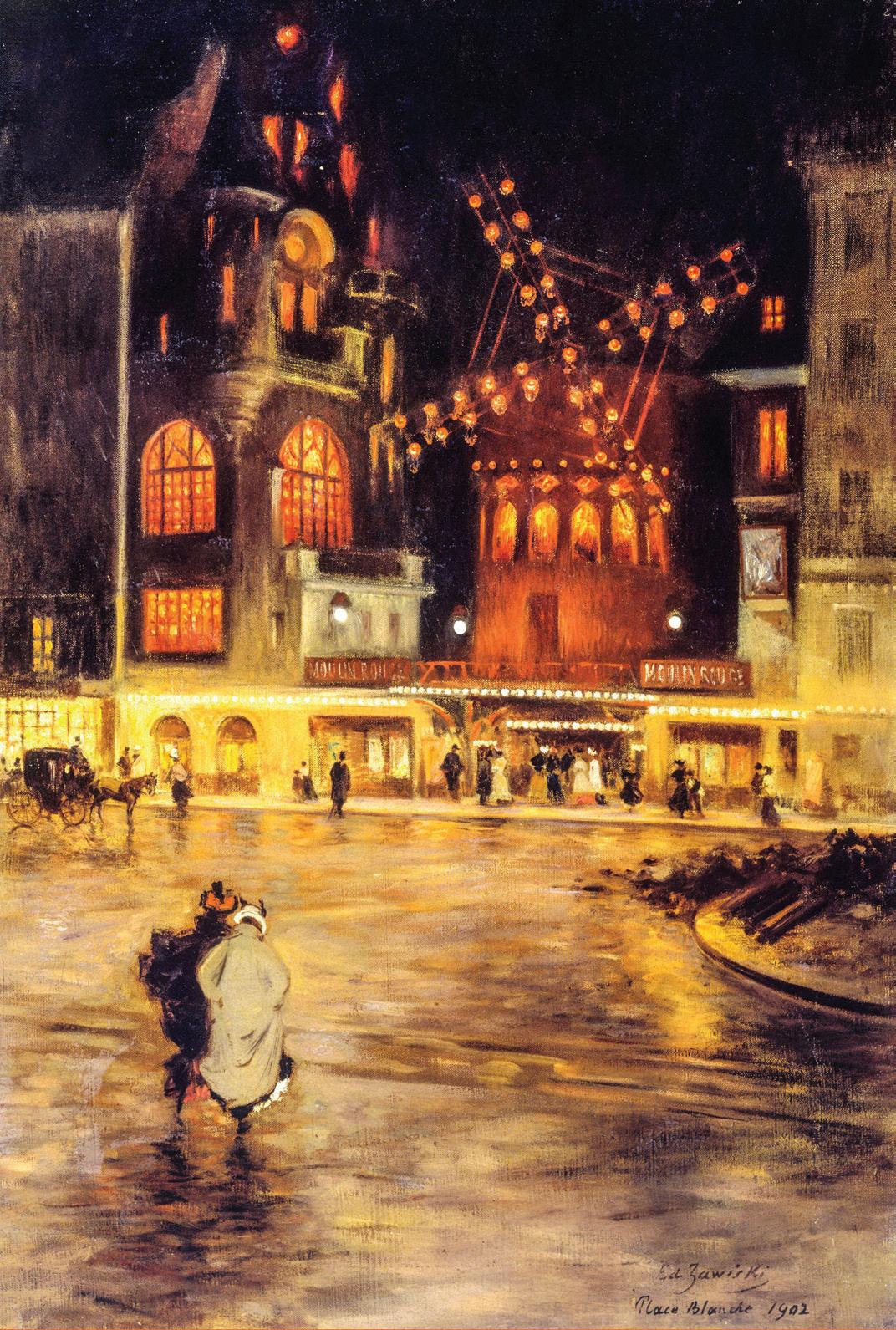

My sad return to Paris Barry Humphries

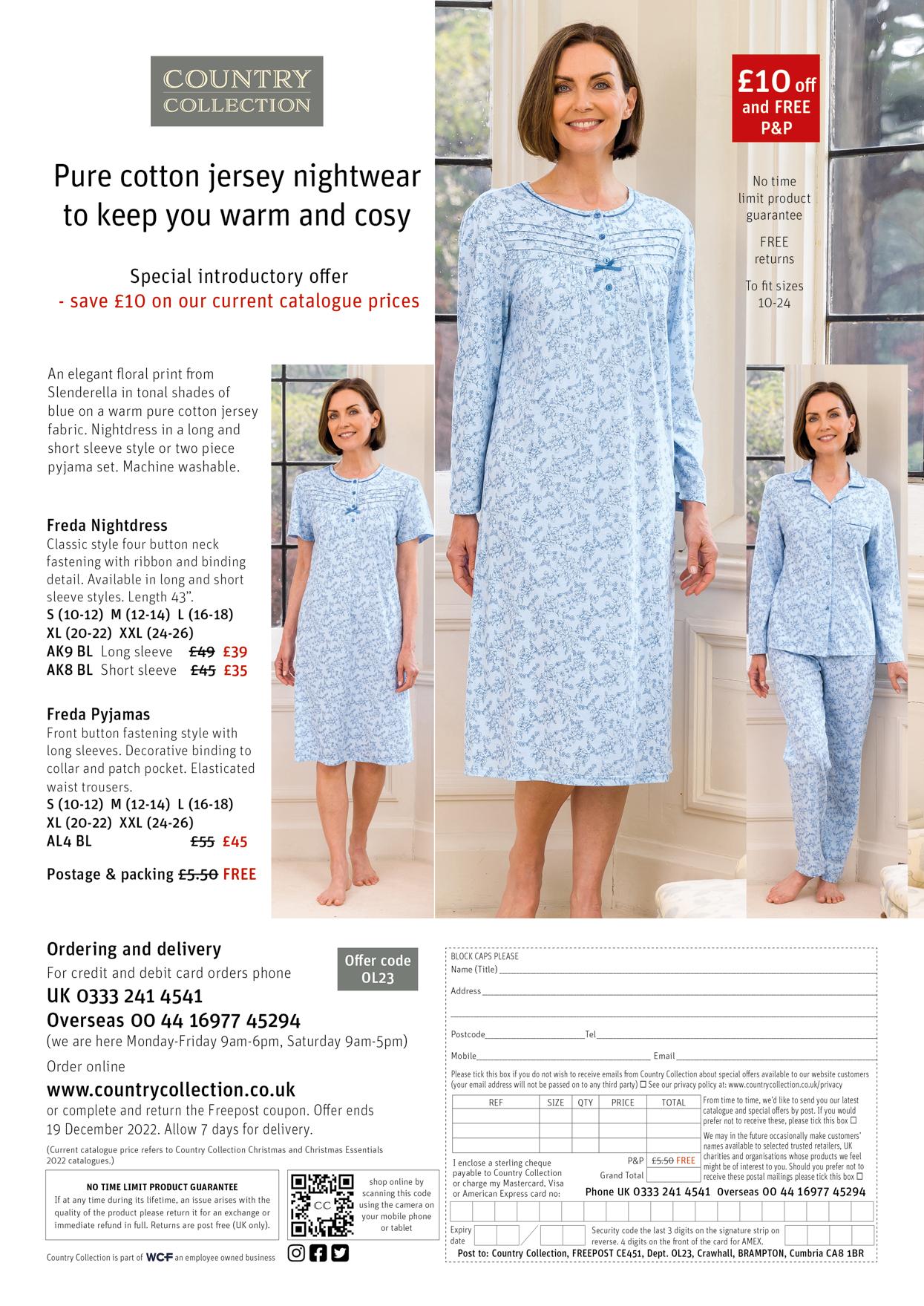

Mary Killen’s Fashion Tips

Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson

Country Mouse Giles Wood

Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny

Small World Jem Clarke

School Days Sophia Waugh

Quite Interesting Things about ... salt John Lloyd

God Sister Teresa

Memorial Service: Sir Richard Shepherd James Hughes-Onslow

The Doctor’s Surgery Theodore Dalrymple

Readers’ Letters

I Once Met… Kurt Vonnegut Christopher Sandford

Memory Lane Peter J Holloway

History David Horspool

Commonplace Corner

Rant: Train travel Maureen Lipman

Media Matters Stephen Glover

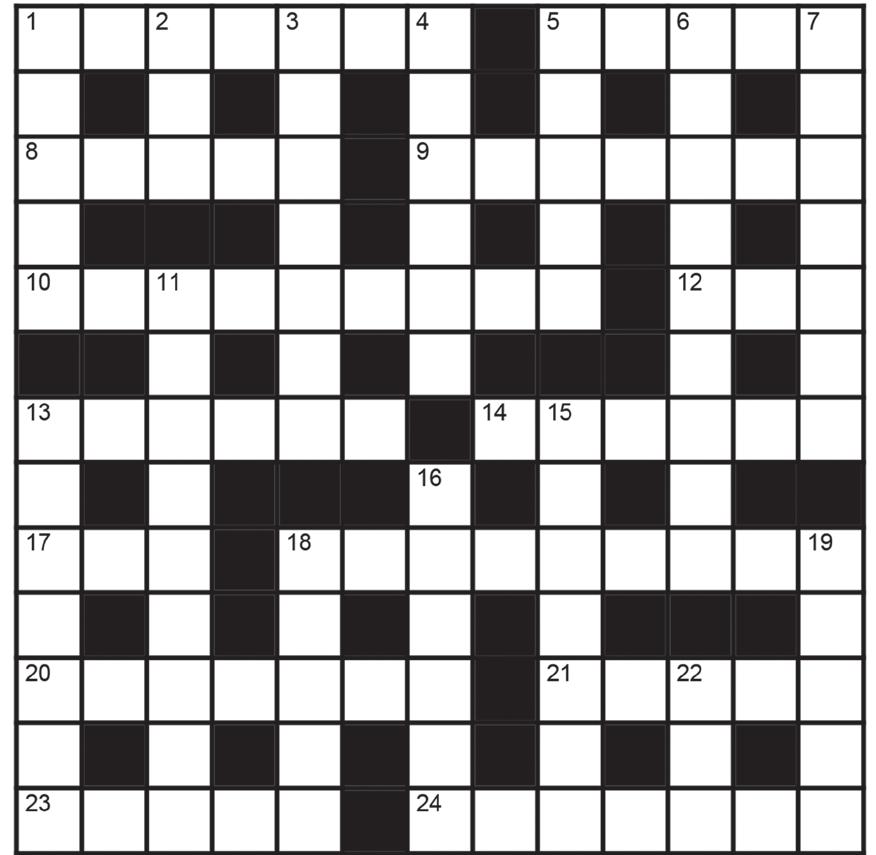

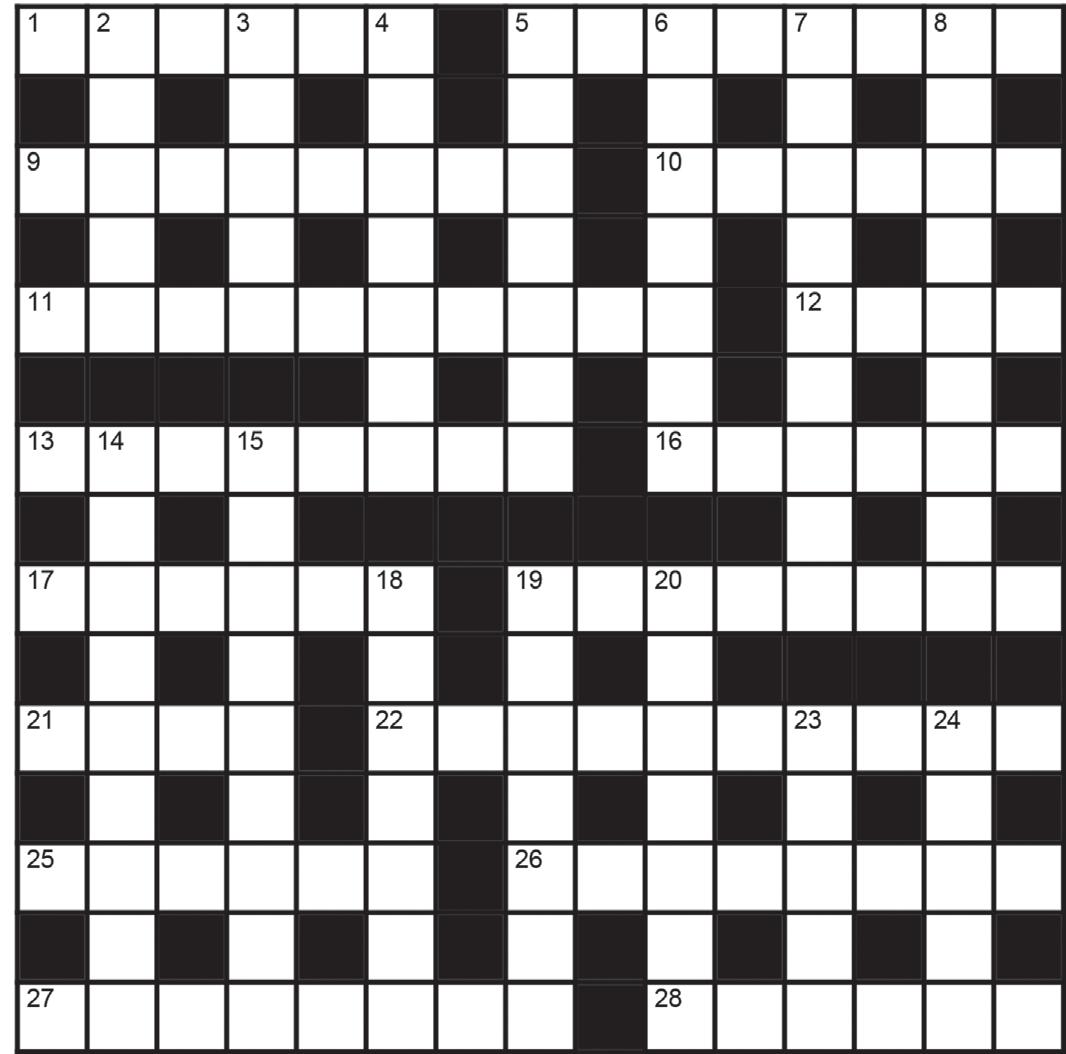

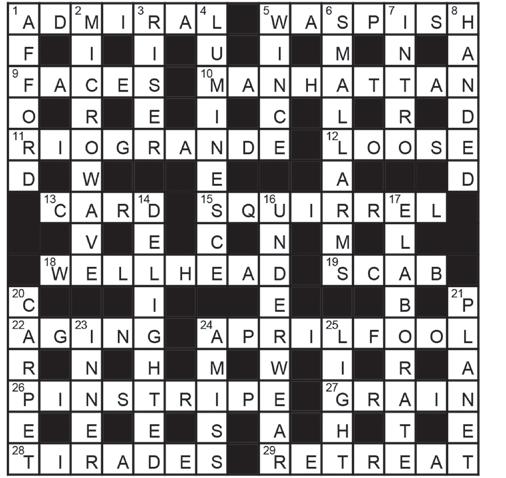

Crossword

Bridge Andrew Robson

Competition Tessa Castro

Ask Virginia Ironside

Harry Mount

Phillips

Jonathan Anstee

Liz Anderson

assistant Amelia Milne

James Pembroke

saints Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

large Richard Beatty Our Old Master David Kowitz

Abyss: The Cuban Missile Crisis, by Max Hastings Ivo Dawnay

Haywire: The Best of Craig Brown, by Craig Brown Robert Bathurst

Darling, by India Knight Georgia Beaufort

The Mad Emperor: Heliogabalus and the Decadence of Rome, by Harry Sidebottom Daisy Dunn

After the Romanovs, by Helen Rappaport Owen Matthews

Siena: The Life and Afterlife of a Medieval City, by Jane Stevenson Jasper Rees

David Stirling: The Phoney Major, by Gavin Mortimer Alan Judd Arts

Film: Mrs Harris Goes to Paris Harry Mount

Theatre: An Inspector Calls William Cook

Radio Valerie Grove

Television Frances Wilson

Music Richard Osborne

Golden Oldies Rachel Johnson

Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu

● To place a new order, please visit our website subscribe.theoldie.co.uk

● To renew a subscription, please visit myaccount.theoldie.co.uk

● If you have any queries, please email help@ subscribe.theoldie.co.uk, or write to: Oldie Subscriptions, Rockwood House, 9-16 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, West Sussex RH16 3DH

77 Gardening David Wheeler

77 Kitchen Garden

Simon Courtauld

78 Cookery Elisabeth Luard

78 Restaurants James Pembroke

79 Drink Bill Knott

80 Sport Jim White

80 Motoring Alan Judd

82 Digital Life Matthew Webster

82 Money Matters Margaret Dibben

85 Bird of the Month: Bewick’s Swan John McEwen Travel

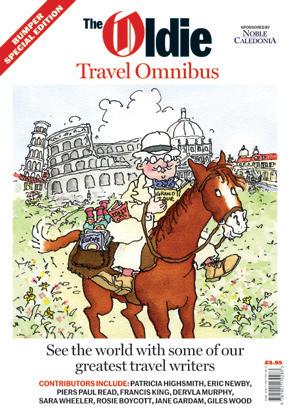

86 Crete’s Greek gods and British heroes Rick Stroud

88 Overlooked Britain: the Blockley trout memorial Lucinda Lambton

90 On the Road: Roddy Llewellyn Louise Flind

91 Taking a Walk: Staffordshire’s enchanting woods Patrick Barkham

New Oldie

Central

● Please email bookorders@theoldie.co.uk

Advertising For display, contact : Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Rafe Thornhill on 020 3859 7093

For classified: Jasper Gibbons 020 3859 7096 News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

Front cover Roger Moore in The Saint, 1966. Bettman / Getty Images

The 50th anniversary of Are You Being Served? was rightfully celebrated by Roger Lewis in our May issue.

Sadly, it’s not just the hallowed premises of Grace Brothers department store that are no more. In a new book, London’s Lost Department Stores: A Vanished World of Dazzle and Dreams, Tessa Boase celebrates their heyday.

Boase writes, ‘Today, we have little idea of the sheer dazzle of these “Halls of Temptation” during the golden age of shopping –their theatrical spectacle, assault on the senses, architectural élan. From the Art Deco of Derry & Toms, with its Moorish roof garden, to the startling Moderne lines of Holdrons of Peckham Rye, department stores led the way in fashion and design.’

Derry & Toms, on Kensington High Street,

began life as Toms family grocery in 1826. It was popular with suffragettes. In 1911, the store was advertising ‘Charming Hats for the June 17th Demonstration.’

The store was in its pomp in 1933 when that vast Art Deco building was erected. In 1936, it even had its own roof garden installed, with one and a half acres of soil hauled up to the roof, and a flowing stream and fountains pumped up from the store’s artesian well, 500ft below the High Street. There was even a flock of flamingos.

Sadly, in 1973, Derry & Toms closed. Richard Branson later set up a

nightclub on the roof terrace – closed since 2018.

Mavis Nicholson, the broadcaster, interviewer and former Oldie agony aunt has sadly died at 91.

Oldie contributor Roger Lewis remembers:

‘Mavis Nicholson was one of Kingsley Amis’s student conquests when he was a lecturer in Swansea. They remained friends, and he often visited her and her husband, Geoff Nicholson, a newspaper rugby correspondent, at their house near the Young Vic. Amis’s novel Take a Girl Like You is dedicated to the Nicholsons.’

Mavis became quite famous with her afternoon chat shows, in the early days of Channel 4, having been picked out by Jeremy Isaacs.

Cosmo Landesman (p25) founded the Modern Review in 1991 with his thenwife, Julie Burchill, and Toby Young. He writes about his son’s suicide and his book Jack and Me: How NOT To Live After Loss.

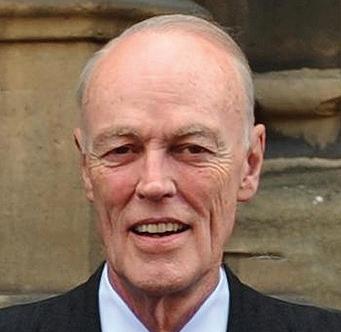

Robert Bathurst (p57) was David in five series of Cold Feet and Sergeant Wilson in Dad’s Army: The Lost Episodes. He starred in Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell. He was in Love, Loss & Chianti this summer.

Daisy Dunn (p59) is author of Not Far from Brideshead: Oxford between the Wars. She also wrote Catullus’s Bedspread, In the Shadow of Vesuvius and the Ladybird Guide to Homer

Rick Stroud (p88) is author of Kidnap in Crete: the True Story of the Abduction of a Nazi General. He wrote Lonely Courage about the women of SOE. He’s won an Emmy and was nominated for a BAFTA.

Derry

Toms (1826-1973)

Roger Lewis continues, ‘She had a sort of Welsh motherly air, and everyone confided in her – Elizabeth Taylor, Nina Simone, Kenneth Williams. Eric Morecambe’s encounter with her is lightly fictionalised in his novel Mr Lonely.’

Mavis always hoped that the old VHS tapes, where they existed, would be remastered and put on DVDs.

Roger says, ‘Perhaps people opened up to Mavis because her programmes were broadcast in midafternoon and there was an assumption no one was watching – unlike the altogether higher-profile Parkinson or Aspel.’

Mavis asked much shrewder questions than other celeb interviewers. She cleverly asked Dame Edna Everage, ‘Edna, were you a man, what sort of clothes would you wear?’

Shoppers upset at news of the Co-op cat’s death Aberdeen Press Journal

Roger Lewis says, ‘I knew her at The Oldie, where at the famous literary lunches she mistook me for Robbie Coltrane.’

Mavis suffered terrible anxiety attacks, and removed herself from public view altogether – eventually ending up in the remote countryside near Oswestry.

She also felt Geoff’s death very keenly. She was a nervous person, and the nerves got worse.

Roger says, ‘Mavis was a wonderfully kind and loyal friend, and we clicked in the way only fellow (Englishspeaking) South Welsh persons can. I thought the world of her. Everyone did.’

To commemorate the death of the Queen, historian Lady Antonia Fraser has written a new verse for The Oldie.

‘How many kidneys did your husband have when he came in?’

entertaining some models at a New York apartment when one of them ran in, complaining about Tyson’s attentions.

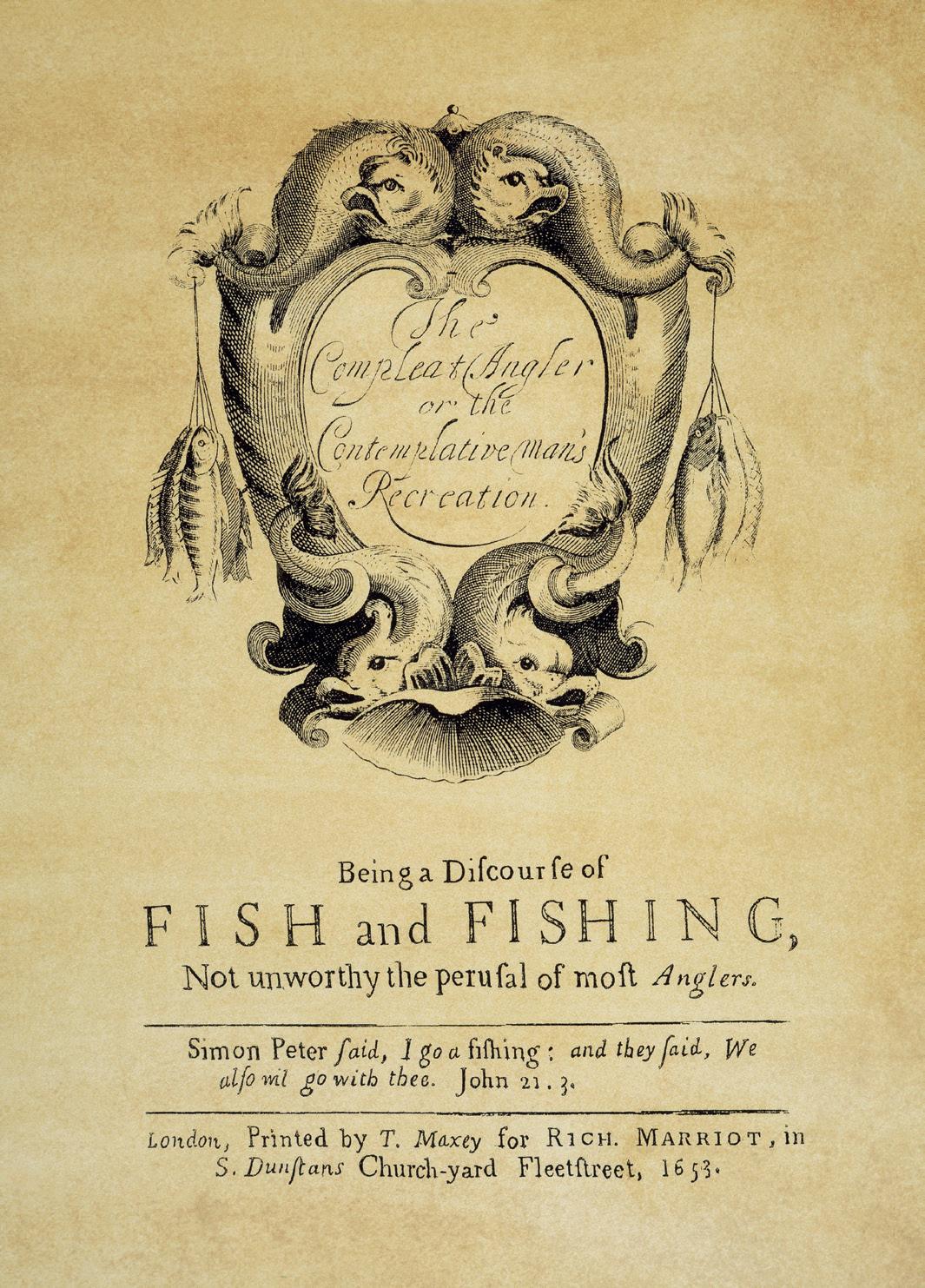

anniversary, Penguin are publishing a new gift edition of the book, so readers can discover a little-known classic that hasn’t been in print for a while.

Set in a fictional boarding school, the book follows Jim, a pleasant young pupil who has the unfortunate habit of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, as when two of the school’s silver sports cups are stolen in a burglary.

The Wodehouse ingredients – the gift for inspired turns of phrase and a farcical plot, based on a wrongly accused innocent (see Bertie Wooster in the Jeeves novels, passim) –are already there.

What joy to see the birth of the Master’s genius!

Bumps in short road Times

Gym at Bourton Leisure Centre closes for refurbishment Cotswold Journal

£15 for published contributions NEXT ISSUE

The December issue is on sale on 16th November 2022.

GET THE OLDIE APP Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

When a soft white hand Caressed my fur, I knew it was her.

When a gentle slap Discouraged my yap, I knew it was her. I’ll miss the caress. I’ll miss the slap; Most of all The Royal Shoes, Planted so near, Planted so long.

In charge of my fate, Shining and strong, Her dogs, her dears She calmed our fears. We knew from those Shoes That we can’t bear to lose She was our Queen

Learning that Disney TV were running an eight-part biopic of the boxer Mike Tyson, the Old Un wondered whether they would include his encounter with the elderly philosopher Sir Freddie Ayer, which took place in New York in 1987.

Well known as a ladies’ man, Sir Freddie was

‘Do you know who I am?’ asked Tyson, when Sir Freddy remonstrated with him. ‘I’m the heavyweight champion of the world!’

‘And I am the former Wykeham Professor of Logic,’ answered Ayer. ‘We are both pre-eminent in our field. I suggest we talk about this like rational men.’

This October marks the 120th anniversary of P G Wodehouse’s first novel, The Pothunters, published in 1902.

To celebrate the

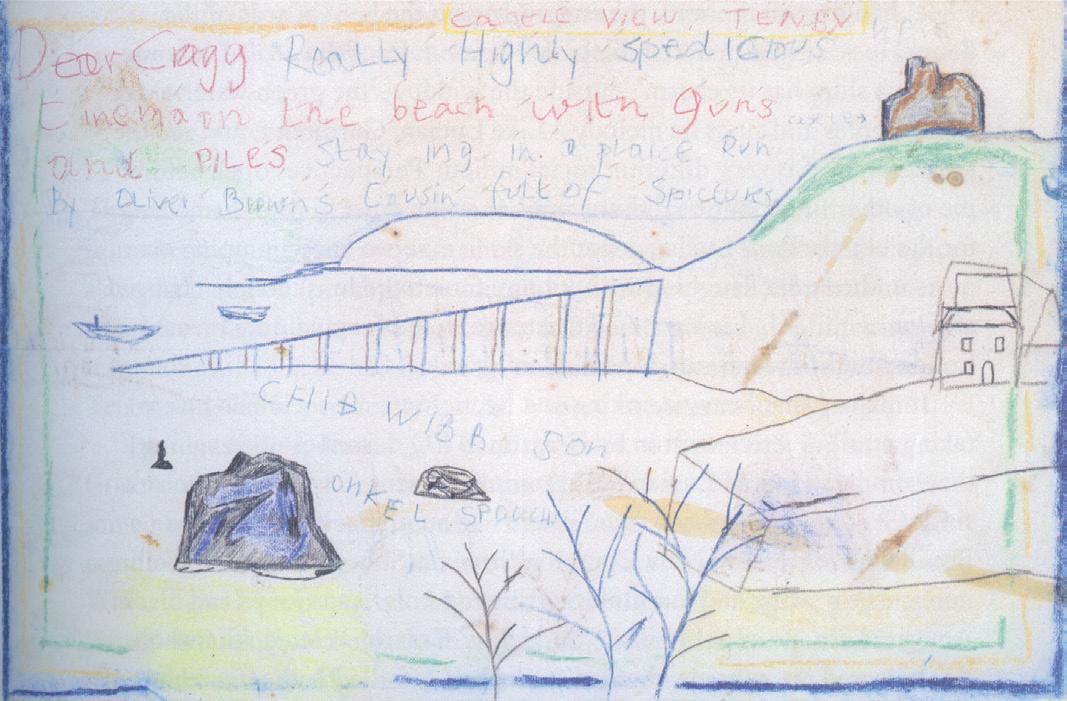

What bittersweet delights are to be found in a new book, It’ll All Be Over by Christmas: The First World War in Postcards, by John Wilton.

Pictured is one by Donald McGill (1875-1962), best known for his sublime saucy seaside postcards.

Wilton writes, ‘During the war years, many cards did not feature the war but town and village scenes and days by the seaside.

‘Others, however, were part of a massive propaganda campaign. The British government’s task was first to

‘They then had to persuade the population that they should fight or support the war effort in other ways.

‘There was also a plan to portray the enemy as both evil and ridiculous. The Kaiser and his son “Little Willie” were singled out for ridicule.’

With 150 illustrations and some rare postcards, it’s well worth a nostalgic read.

Oldie columnist Barry Humphries was the star turn at the recent Lord’s Taverners’ tribute lunch to Michael Parkinson.

Their long friendship began with Parky’s first interview, which ‘put me on the map’, Barry assured the Lord’s audience.

It had nothing to do with

cricket, Barry added: ‘I attribute my great age to the total avoidance of all forms of sport, particularly cricket. If I’d known he had anything to do with cricket, I’d never have spoken to him.’

‘That’s a great question’ persuade the population that the war was just.

After his cabaret performance – a tribute to Parky in verse, wearing a pair of Dame Edna’s glasses –Bazza received on stage the customary thank-you gift bag, containing, as usual, a single bottle of champagne.

Barry raised it aloft. ‘What a perfect gift for a teetotaller,’ he said, with a grimace. ‘Thanks for nothing!’

As the Old Un settles into autumn, he fondly cherishes the highlight of his summer: stumbling across the Shearing Shed at the Royal Welsh Show in Builth Wells.

Nestled between the Cattle Ring and the Angora goats, shearers sweated in the heatwave, competing to be the best in their class.

In the Veterans section (61 years and over), each competitor skilfully sheared three lambs. While he didn’t

win, there was a standing ovation for Barrie Kent – the oldest competitor at 91.

Born on the family farm near Aberystwyth, Barrie grew up shearing by hand before switching to an electric clipper. He left home and eventually ended up working with cattle in Worcestershire.

Still, he always kept his hand in because ‘a day shearing was the equivalent to coming home with a week’s wages’.

After retiring nearly 30 years ago, he bought a few Lleyn sheep so that he could practise on his own flock. Today he keeps 100 breeding ewes.

Anything from two to five days a week, he goes to Pilates or yoga. His teacher is a shearer, too. Together they contract-shear around the county. What’s his secret to such an active life? He’s quite clear about that.

‘Not stopping!’ he says.

Our muchloved deputy editor and patron saint of The Oldie, Jeremy Lewis, died in 2017, aged 75. In his memory, we run the Jeremy Lewis Prize, worth £500. It rewards the sort of writing that emulates Jeremy’s wit and lightness of touch in his books and journalism.

What to write about

In 400 words, recount a memory (similar to our Memory Lane column, on page 54 of this issue). Please begin by saying when the events you describe took place. How to send your entry

Simply email your entry to editorial@theoldie.co.uk by 13th November 2022. Please mark it JEREMY LEWIS PRIZE.

What for you were the most moving moments during the coverage of the Queen’s funeral?

For me it was, probably, the first sight of her coffin being borne on the shoulders of those fine young soldiers – or possibly her groom, Terry Pendry, on the Long Walk at Windsor, standing, head bowed, with the Queen’s pony, Emma, as the royal hearse drove Her Majesty home for the last time.

Because I was part of the BBC team covering it all, every day over the ten days between her death and the funeral, I found myself in London walking from Green Park tube station across the park to the Victoria Monument outside Buckingham Palace where the BBC (alongside scores of other broadcasters from across the world) had set up their makeshift studios.

Meeting the throngs of people, of all types and ages, coming to the Palace to pay their respects – in their thousands, often with tears in their eyes and small bunches of flowers in their hands, and quite a few with little Paddington Bears – was very affecting. The mood was quiet, but friendly.

On the Friday before the funeral, as I was walking across the park, a little boy, aged seven or eight, ran towards me, stopped, bowed at the waist and said, ‘Good morning, Your Majesty!’

Yes, he had mistaken me for the King. (Well, we are the same age.) It turned out his mother had recognised me and exclaimed, ‘Look, it’s that Gyles off the telly!’ and her son had misheard the name and jumped to the wrong conclusion. I confess I hesitated a moment before I disabused the boy.

It’s easily done. At the lunch Joanna Lumley and I hosted with The Oldie in July to mark the 75th birthday of our now Queen Consort, Craig Brown looked across the crowded room and was excited to see Norman Scott (former lover of Jeremy Thorpe, the former Liberal Party

Leader acquitted of conspiracy to murder his ex-boyfriend in 1979) seated in a place of honour right beside Camilla.

It took Craig back to the celebrated dinner (marking Margaret Thatcher’s 80th birthday) at which the disgraced former minister John Profumo was seated conspicuously at the Queen’s right hand.

In this instance, it wasn’t Norman Scott at all. It was the distinguished children’s author, Sir Michael Morpurgo – at 78, four years Scott’s junior. They do both share a love of horses.

When I say it’s easily done, I mean it.

In the BBC’s Portakabin production office, on the night the Queen’s body arrived back at Buckingham Palace from Scotland, I went up to India Hicks, a direct descendant of Queen Victoria and daughter of Pamela Hicks, who as Pamela Mountbatten had been a lady-inwaiting accompanying the young Princess Elizabeth when she heard the news of her father the King’s death in Kenya, in 1952.

Carried away by the emotion of the moment, I kissed India on both cheeks and held her hands, and offered my condolences to her and to her beautiful mother, adding for good measure how well I had known her wonderful aunt, Patricia Mountbatten, and her splendid uncle, Lord Brabourne, and how I had even had the honour of knowing her heroic grandfather, Earl Mountbatten of Burma.

At this point, I glanced over her shoulder and recognised the real India Hicks sitting in a corner texting someone

on her mobile. I realised then that the person whose hands I was clutching so closely was a bemused make-up artist who was there working for the BBC.

I went to three funerals inside ten days: those of my sister, Jennifer, aged 84; my sovereign, Elizabeth II, aged 96; and my friend Theo Richmond, 93, television director and writer, who will be best remembered for his book Konin, published in 1995, still available and a must-read for many reasons.

The book tells the story of a small Jewish ghetto in a small town in Poland – and of Theo’s obsessive quest to discover its fate and find its survivors and to place on record something of what the Nazis had destroyed.

It is an extraordinary book and Theo was a remarkable man, both deeply serious and terribly funny. At his funeral, his widow, the award-winning novelist Lee Langley, told us about the cartoon she and Theo had on a wall at home. It’s of a man sitting up in bed saying to his wife, ‘I thought I’d get up early. Got a lot of worrying to get through.’

According to Lee, ‘Theo often got up early. He was a world-class worrier. A global catastrophist. To paraphrase Philip Larkin, anxiety was to Theo what daffodils were to Wordsworth. I never left the house without Theo’s being sure I’d be knocked down in the street by a bus or a car or even a bicycle.’

This pessimism notwithstanding, Theo felt a day without laughter was a day wasted.

Lee told us, ‘He once said he had a project: we wouldn’t ever say goodnight without his making me laugh. He managed it for as long as he was able.’

If you’re lucky enough to have someone to live with, make them laugh before lights out tonight.

Although my mother had a successful career as a fashion journalist, she missed out on not one but two other vocations.

Those with ungodly staying power will find the second outlined at the end, but the first career for which nature ideally equipped her was that of interrogator. She could break the hardest Lubyanka inmate with nothing more in her arsenal of torment than verbal relentlessness.

‘Have you booked it yet?’ she asked a couple of months ago, the ‘it’ being one of those enticements with which the daytime television audience is unceasingly bombarded.

Joining funeral insurance, recliner chairs and pulsating devices on which Ian Botham places his feet is a commercial for a viral vaccine.

‘Have you booked it?’ she reiterated after the first enquiry was met with sullen silence.

‘Inexplicably,’ I replied, ‘what with it being a few seconds since we became aware of its existence, no, I haven’t booked it.’

The vaccine, plugged during every Countdown advert break, is for shingles.

‘Shingles can be very dangerous,’ she went on.

‘In the name of God,’ I heard myself mutter, ‘not the old wives’ tale about the spots meeti—’

‘If the spots meet around the waist,’ intoned my mother, ‘you can die. And even if you don’t, it’s a nasty, agonising illness. I want you to book the jab.’

During the next ad break, the inevitable ensued.

‘Have you booked yet?’ she enquired.

‘Yes, I have. I booked it while Susie Dent was doing her Word of the Day.’

‘I didn’t hear you.’

‘I did it by telepathy. They give you a 15-per-cent discount for booking telepathically. Takes pressure off the call centre.’

‘Nonsense,’ she declared. ‘Book it

now. I’ll pay. Consider it an early birthday present.’

How could a chap resist? A fortnight on St Maarten, a season ticket for Spurs, shingles jab, Maserati … these are the high-tariff items about which those with a 59th birthday on the horizon tend to dream. ‘All right, I’ll book it,’ I yielded.

‘When?’

‘Soon. I’ll book it soon.’

‘How soon?’

‘Soon enough.’

‘Soon enough to get shingles,’ she bleakly observed.

‘Is this really an emergency? We’ve gone several decades without mentioning shingles,’ I protested.

‘Exactly. There’s not another moment to lose,’ she said, eerily in the tone of Sherlock Holmes offering the hansomcab driver a sovereign to get him to Waterloo by sunset.

‘Can I finish my tea? I’m fairly sure shingles will have the decency to lay off until I’ve finished my tea.’

‘Don’t finish your tea. Book it now.’

My mind turned to Nineteen EightyFour, and specifically to whether O’Brien would have bothered with the rats if he’d had my mother for his Room 101 sidekick.

So it was that, not long after this medical symposium, I found myself in a branch of Superdrug with a rolled-up left sleeve.

‘What made you book?’ asked the inoculator, a witty Glaswegian woman.

‘My mother. She wanted to get me something nice for my birthday.’

‘Well then, if you’re a good boy, and don’t make a fuss, I’ll stick a rosette on the jab area instead of a plaster.’

The good news is that, in the weeks since, I have remained ostentatiously free of any stress-induced chickenpox-related virus.

The less good news is that there is no way, and never will be, of determining whether the vaccine is responsible. The alternate timeline in which I eschewed the jab will for ever be unknowable.

For Doctor Who, it would be easy. He or she, or they, could take the Tardis to the future that developed after my mother never saw the advert, to discover whether shingles struck in that parallel reality.

In the guise of Tom Baker, the Doctor did much the same, albeit in the slightly different context of cosmic annihilation. In Pyramids of Mars, he showed Sarah Jane the results of not acting to prevent Sutekh, the Ancient Egyptian god of destruction, from escaping the Eye of Horus. He took the Tardis to a desolate, Sutekh-ravaged future.

Requiring no such Time Lord technology to be certain, my mother is taking full credit for my continuing shingles-free status. ‘Of course that’s why you haven’t got it,’ she observed a couple of days ago when the commercial made its 149th appearance of the day. ‘If it wasn’t for me, you’d be scratching yourself to death.’

The advert yielded to the walk-in bath, and then the noble Lord Botham, pretending to hobble before the footvibrator thing miraculously restores his athletic prowess.

A thought first flashed to mind like a thunderclap headache, and then spilled into words. What if the roster of geriatric commercials is boosted to the tune of a penis enlargement?

‘I’m not buying you one of those,’ said my mother, elegantly hinting that the other lost vocation was in Carry On scriptwriting. ‘From the way you tolerated that shingles jab, the one thing you do seem able to cope with is a little pr—’

‘If it wasn’t for me,’ my mother said, ‘you’d be scratching yourself to death’

Who would buy a vaccine off a telly ad? My mother

GIVE ONE 12-issue subscription for £39, saving £20.40 on the shop price, and get one FREE copy of The Oldie Annual 2023 worth £6.95

TWO subscriptions for only £65, saving £53.80, and get one FREE copy of The Oldie Annual 2023 AND one FREE copy of The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons worth a total of £15.90

THREE subscriptions for just £79 – BEST DEAL, saving £99.20, AND get the two books plus The Oldie Travel Omnibus, worth a total of £21.85

Complete

with

Freepost RTYE-KHAG-YHSC Oldie Publications Ltd, Rockwood House, 9-16 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3DH

CALL 0330 333 0195

Interviews with Rula Lenska, the actress now touring with The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel play, often say she was born in St Neots, Cambridgeshire, my home town.

In fact, she was born on 30th September 1947 at the Polish Resettlement Camp at Diddington, a tiny village about five miles away, although her birth was registered in St Neots.

But what were resettlement camps?

After the Second World War, many Polish refugees, including Rula’s aristocratic family, weren’t able to return to their homeland as they had supported the Western Allies. The British government took responsibility for them, founding the Polish Resettlement Corps in May 1946. The only way these people could be accommodated was by putting them into camps and barracks vacated by the Americans and Canadians after the end of the war.

Eventually, around 250,000 Poles

came to the UK to be housed in the camps, often situated in remote locations on large country estates. The biggest was at Northwick Park, Middlesex, which housed a thousand people. The camps were operational from 1946 to 1969.

Rula’s camp in Diddington, like most of the others, consisted of a vast collection of corrugated, rusting Nissen huts. The huts first housed prisoners of war and then became an American military hospital before being requisitioned as a resettlement camp.

I only knew about the camp because I used to pass it on my way to school on the bus and often wondered what went on there as it looked both mysterious and abandoned. I never saw any signs of life or any people.

The camp was in reality a busy place.

Pretty much self-sufficient, it followed Polish customs and the Polish way of life. There was, initially, little integration with the locals who remained suspicious of foreigners in the English countryside.

The Diddington camp had a maternity hospital and more than 1,000 babies were born there between 1947 and 1949.

A secondary school was established, with about 300 pupils and a Catholic church was set up in one of the huts. All the teachers and ancillary staff lived on the site, which had water and electricity, although conditions were rough and ready and certainly very basic.

There was a cinema at the camp, which was just as well as there was absolutely nothing to do in Diddington, a village of only 100 residents with no shops or pubs. Then, gradually, from about 1955, the Nissen huts started to fall into disrepair, as the residents began to leave. Many went to live in nearby Huntingdon. Today, there is absolutely no sign that the camp ever existed and no memorial or plaque to commemorate it – which is sad.

Liz HodgkinsonBeReal is a smartphone application that allows you to share photographs of yourself with your friends and the world at large.

It is the Generation Z social media phenomenon of 2022. By August, it had gained 10 million daily active users, 55 per cent of whom are estimated to be aged 16 to 24.

‘Not another social network!’ I hear you cry.

And, funnily enough, that’s exactly how BeReal pitches itself – as an antidote to the more established photo-sharing platforms. ‘BeReal won’t make you famous,’ it reassures you when you sign up. ‘If you want to become an influencer, you can stay on TikTok and Instagram.’

All BeReal asks of you is to post a single unfiltered picture per day. Well, two pictures actually. It uses both cameras on your phone, front and back,

so that your messy bedroom, school classroom or (most likely) computer screen forms part of your image, along with a small inset of your face. You can’t edit or touch up these images. And you must take your double-portrait at a time of BeReal’s choosing.

Everyone’s phone pings at the same random time – and then everyone has only two minutes to take their photo.

There’s a pleasing happenstance to the results. Depending on the time the ping goes out, you might get a clutch of morning commutes or evening meals. On 5th September, the call arrived at the precise moment Liz Truss was announced as Prime Minister.

‘Just found out about liz truss via bereal how’s your afternoon going,’ complained one Gen Zer.

The internet meme merchants have already got to work imagining what other historical disasters might look like on BeReal, from 9/11 to the Crucifixion.

You can also find mock-ups of celebrity BeReals, imagining what, say,

Harry Styles might actually be doing at 3.17pm on a Thursday. As for actual celebrities, they appear few and far between on BeReal – for the moment at least.

One of the reasons people like BeReal is that it reminds them of ye olde internet – before it became the commercial hellscape it is today.

But does it fulfil that implicit promise – to make us more real? The thing about Instagram is, people only share stuff that’s interesting. It’s edited highlights. BeReal is more like unedited lowlights. If you happen to be riding a rollercoaster, playing pickleball, or making love to your personal trainer when the BeReal notification arrives, you’re likely to miss it.

Hence the app abounds in the mundane: desks, computers, offices, sofas, pavements and playgrounds. If anything, the app has the effect of making people’s lives seem duller than they actually are. Not such a bad thing.

Richard Godwin

What makes for a real eccentric? It’s a question I’ve been chewing over since deciding to pick a new crop of Daily Telegraph obituaries for a book, Eccentric Lives

‘The eccentric’ is the quintessential Telegraph obituary subject, pioneered in the late-1980s by the great Telegraph obituaries editor Hugh Massingberd.

Massingberd’s idea was that our quirks and foibles are what make us truly human. He was inspired by P G Wodehouse and the 17th-century antiquarian John Aubrey’s Brief Lives, among others.

Aubrey brought sharp and witty observations: the philosopher Thomas Hobbes would sing loudly when he went to bed at night – ‘not that he had a very good voice, but for his health’s sake; he did believe it did his lungs good and conduced much to prolong his life’.

Back in the 20th century, Massingberd uncovered a rich seam of Technicolor eccentrics, such as the 9th Earl of St Germans, obituarised in 1988. He listed his recreations in Who’s Who as ‘huntin’ the slipper, shootin’ a line, fishin’ for compliments’.

Could you get away with that now without seeming to be trying too hard?

I’m not sure. Eccentricity today risks being confused with a kind of elitism. The modern eccentric learns to be subtler. Massingberd himself was an eccentric but, as his friend Craig Brown wrote after he died in 2007, aged 60, he ‘did his best to appear conventional’, ‘like most true eccentrics’.

Not that the attempt was entirely successful. A very big man, Massingberd ‘pushed generosity well beyond the bounds of sanity’, paying for everyone’s dinner even though he was ‘invariably strapped for cash’, and presenting himself, in his newspaper columns as in life, as an 18th-century gourmand – ‘a valiant trencherman’. He was once photographed as a Roman emperor, ‘garlanded with sausages’.

Now there you see two key features of the real eccentric. Massingberd’s ‘two fingers’ to the diktats of 1990s health commissars reveal a spirit that bridled at conformity, and his presentation of himself brimmed with a sense of cheerily not caring what people thought.

That last quality is seen in Johnny Barnes, aka Mr Happy, a Seventh Day Adventist in Bermuda, who for 30 years would wave benedictions at commuters from his spot at a roundabout on the road into the capital, Hamilton.

From 3.45am onwards, he blessed motorists with ‘I love you – God loves you!’ Far from dismissing him as a religious odd bod, locals adored him.

Most of the obits in the book are of little-known figures like Mr Happy; that was part of the point of Massingberd’s transformation of the form. The obitwriter’s spotlight was newly pointed at those who would once not have been deemed ‘worthy’. But a yearning to reject convention is found everywhere – even on the benches of the House of Commons.

The Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe –as prosecuting counsel at his trial for conspiracy to murder put it – was at the centre of a ‘tragedy of truly Greek and Shakespearean proportions’. He also ticks the right boxes for inclusion in our book – the box marked ‘outmoded dress and eccentric headgear’, for example.

While electioneering, Thorpe favoured a brown bowler hat and, as an Oxford undergraduate, ‘frock coats, stove-pipe trousers, brocade waistcoats, buckled shoes, and even spats’.

His obituary spoke of a ‘quick mind’ reacting strongly against ‘bone-headed Establishment snobbery, arrogant management or racial injustice’.

The obit is also clear-eyed about how Thorpe’s ‘mask of the jester’ could quickly give way ‘to a fixed, distant and icy stare’. ‘Far from being a tragic hero,’ it concludes, ‘he appeared … amply provisioned with common human flaws.’

Oddballs: Sathya Sai Baba, guru; Rev David Johnson, prankster; Viv ‘Spend, spend, spend’ Nicholson; Morris dancer and rocket scientist Roy Dommett

Does anything about Thorpe remind you of that young fogey you knew in your youth? Not the murderous, conspiring bit, maybe, but the snazzy waistcoats and the hats? Wasn’t there always at least one who affected 1950s Received Pronunciation and wore a tie and tweed jacket (with accessories – a brilliant undergraduate in my college sported a monocle)?

It’s irrelevant that Dad might be an IT consultant from Peterborough. The son’s tweed jacket and non-mainstream manner is a kind of rebellion. It shows courage to invite the mockery of snobbish peers too scared to diverge themselves. And those outward oddities may be ‘put on’ but, over time, the sillier ones will fall away. The rest will become baked in – real.

What matters about the true eccentric is the mind beneath. Today’s eccentric is the truly ‘neurodiverse’. He or she has a mind that kicks against the homogenising of management training, committees and devices designed to smooth out the bumps.

Real eccentricity is about nurturing an independent spirit, the quality the Telegraph obituary celebrates.

How that spirit manifests itself is infinitely varied. It doesn’t have to be attention-seeking or contrived. The eccentric today may hide his or her light deeply under a bushel.

Look carefully, because you probably know one. Perhaps you are one.

Andrew M Brown, the Daily Telegraph obituaries editor, is editor of Eccentric Lives: The Daily Telegraph Book of 21st Century Obituaries (Unicorn, £25)

On 4th October 1962, ITV aired the first television adaption of Leslie Charteris’s Saint novels.

The star was the 34-yearold Roger Moore (1927-2017), then best known for Ivanhoe and Maverick

When the last adventure aired on 9th February 1969, 118 episodes later, many viewers regarded him as the ideal screen Simon Templar, surpassing even

was made under the auspices of ITC, which specialised in ‘International Man of Mystery’ television series. The producers were the B-film veterans Robert S Baker and Monty Berman. Moore had previously attempted to buy the rights to the novels by Leslie Charteris (1907-93) but found

ITC’s MD, Lew Grade, wanted Patrick McGoohan to play Templar, but Baker and Berman thought he lacked humour.

One early challenge was a car for the Saint. The producers intended to use a Jaguar Mk X, but the company refused to loan a demonstrator and turned down Moore’s offer to buy one, so long was

However, a crew member had recently seen a rather splendid Volvo P1800. So the leading man visited the firm’s British concessionaire in Mayfair. Shortly afterwards, an immaculate white coupé arrived at Elstree Studios. That original P1800 has recently undergone a complete restoration. As the series progressed, Templar acquired updated versions.

Volvo also provided cars for the star’s off-screen use, which proved ideal for his many personal appearances.

In 1963, Coopers of Brompton Road invited their customers to ‘Meet the Saint in Person’, accompanied by ‘a guard of honour’ of the massed band of the Dagenham Girl Pipers.

Templar encountered many a sinister

villain in his escapades across the world. They were portrayed by a regular team of ITC character actors, including Burt Kwouk (Cato in the Pink Panther films).

The Saint also had an interesting approach to continuity, with cars changing model in mid-chase and, thanks to the art of undercranking, Ford Zephyr 4s having the ability to travel at 150mph.

Future stars also enhanced the casts – Julie Christie in Judith, an overacting Oliver Reed as a Greek-American gangster in Sophia, and Steven Berkoff as a ‘heavy’ in The Man Who Gambled with Life. Warren Mitchell played a Rome taxi driver in three stories. Escape Route featured Donald Sutherland making one of his many appearances in 1960s British television. The Russian Prisoner is especially enjoyable for the sight of Yootha Joyce as a KGB colonel and Anthony ‘Tony Blair’s father-in-law’ Booth as her somewhat clumsy sidekick.

ITC promised audiences ‘exotic locations’, although, for most of the plots, ‘abroad’ involved ten-year-old stock footage and driving on the wrong side of the road in Hertfordshire.

Unusually, the two-part adventure Vendetta for the Saint was shot overseas; albeit in an ‘Italy’ dominated by righthand-drive vehicles with Maltese number plates. None of which prevented The Saint from airing in more than 80 countries and becoming Grade’s most profitable export.

The critical element in the programme’s success was the toooften-underestimated Roger Moore.

The TV critic Nancy Banks-Smith contended he had ‘long realised that raising his right eyebrow and turning his left profile to the camera is all that is required of him’.

In the Daily Mail, Virginia Ironside (now The Oldie’s agony aunt) admired Moore’s ‘astonishing hair’ and said that, ‘of his kind of hero, he is one of the smoothest and the best’.

Each week, Templar could be relied

on to cope with shaky back projection, break down balsa-wood doors or crash through ‘border crossings’ that appeared to be made of cardboard.

Most importantly, Moore would frequently demonstrate his considerable light-comedy talents.

Many of the most enjoyable stories had Templar swapping bons mots with Sylvia Syms, Patricia Haines or Ivor Dean as the definitive Detective Chief Inspector Teal. The pre-credits sequence established the mood, with a supporting actor uttering, ‘Why, it is the infamous Simon Templar!’ An animated halo would then appear above Moore’s quiff as he pulled an entertainingly wry expression at the camera.

In 1965, the NBC television network bought The Saint, which meant ITC filmed the last 47 editions in colour. The almost Miss Marple atmosphere of the original episode, The Talented Husband now seemed very remote. The Fiction Makers is the nearest the series came to the Emma Peel-era Avengers, and The Power Artists had Templar encountering a gang of beatnik art students.

Meanwhile, the producers exhausted the supply of Charteris’s original books, and the author was not always impressed by the new narratives. ‘As usual, this script is fit for Junkin(g)!’ he wrote of the efforts of the story editor, one Harry W Junkin.

By the late 1960s, Moore sought new acting challenges, remarking, ‘The Saint, although I’m very grateful to him, is rather a predictable chap.’

In fact, it was Templar, rather than 007, who showcased Roger Moore’s talents – too often derided by Moore himself – not least in the first colour episode, The Queen’s Ransom

It has a villain with a fez and an eyepatch, ITC’s stock footage of a white Jaguar heading off a cliff and Roger Moore at his considerable best.

And the result is eyebrow-raisingly good television.

On 5th October 1962, the first cinematic adaptation of an Ian Fleming 007 novel went on release.

The star was an up-and-coming 32-year-old actor named Sean Connery – yet it might have been Richard Todd, David Niven or Patrick McGoohan uttering the line ‘Bond, James Bond’ to Eunice Gayson.

Throughout the

60-year history of the Bond film, the list of alternative casting choices has varied from the plausible (Oliver Reed, Lewis Collins or Sam Neill) and the intriguing (Laurence Harvey or Richard Burton) to the surreal: the journalist Peter Snow.

In July 1961, the trade paper Kine Weekly announced that Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had obtained backing from United Artists to film the sixth Bond tale.

One challenge was a budget of $1 million. This may have been a sum beyond the dreams of a Carry

On or a Hammer Horror, but was still not high by the standards of a major Hollywood production.

Another was choosing the right man to play the role of the secret agent, described by Vesper Lynd as resembling singer Hoagy Carmichael.

Fleming had his own casting ideas, including Edward Underdown, a tall, elegant actor – less Carmichael and more John Le Mesurier’s slightly less languid brother. There was little of the ‘cold and ruthless’ spy of Casino Royale.

Underdown’s range mainly encompassed military officers, with the occasional diversion into deadpan comedy and B-film villainy.

There was also the issue that, by 1962, Underdown would have been 54, while 007 was supposed to be in his thirties. Yet, a few years earlier, he might have made an entertaining Bond in the kind of black and white thriller screened by Talking Pictures Television, with Shepperton’s backlot doubling for Jamaica.

The author also suggested David Niven, who, like

James Bond in Dr No

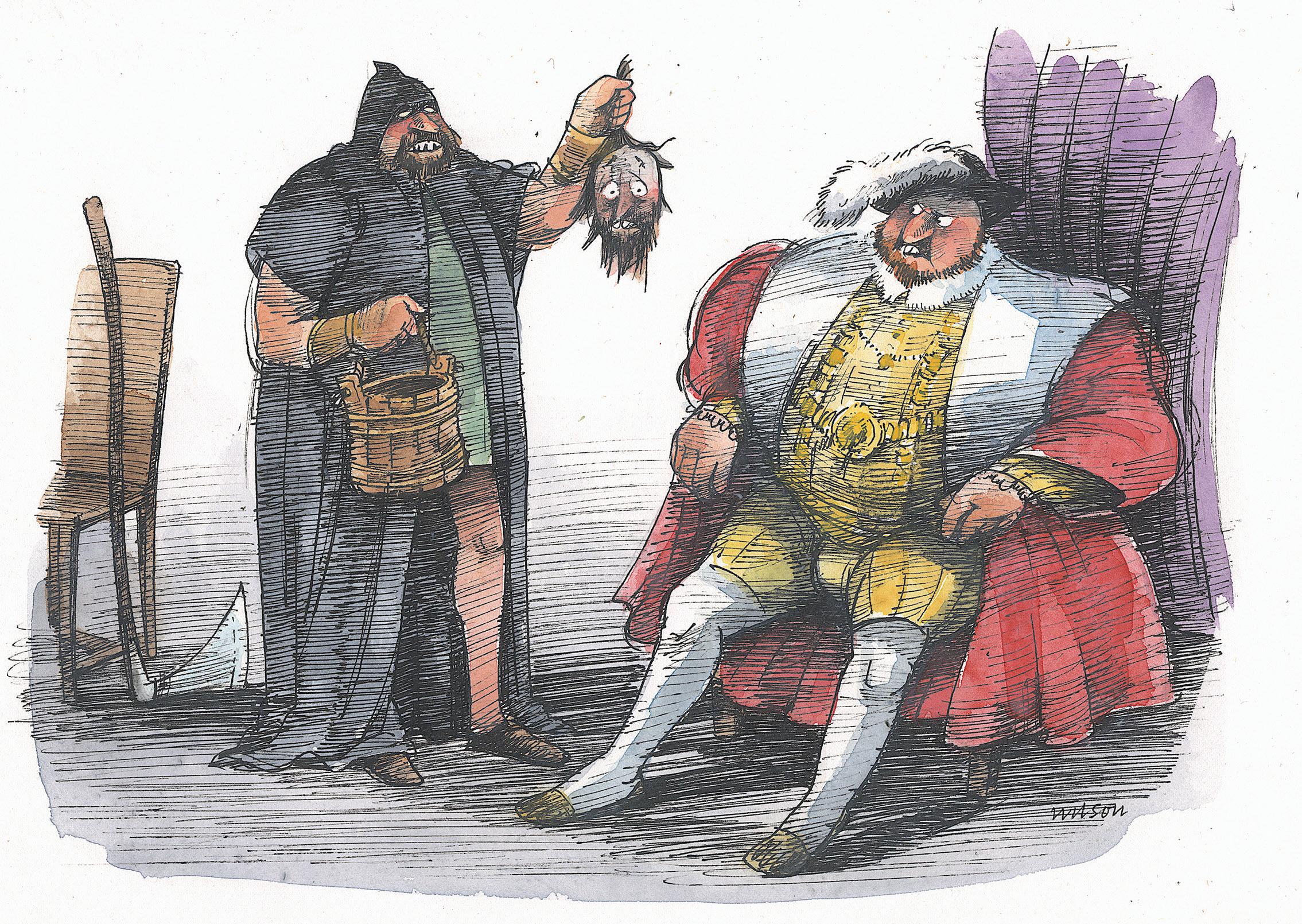

screens in the same week in 1962. Andrew Roberts salutes them

Possible Bonds (clockwise from above): Stewart Granger, Richard Todd, Patrick McGoohan, Richard Johnson, Edward Underdown, David Niven

Underdown, was in his early fifties and considered insufficiently tough by the producers, despite his war record.

A few years later, Niven did play Bond in the spoof version of the first 007 story, Casino Royale (1967) – Broccoli and Saltzman did not option it.

Unfortunately, the picture had the joie de vivre of a public-information short about drains, with Niven’s moustache seeming to wilt in embarrassment.

Fleming also recommended Stewart Granger, who might have made an exciting Bond, had he been 20 years younger, or Richard Todd, who, at 43, was nearer the right age.

He was considerably shorter than Granger, but this mattered less than his screen persona. Todd excelled at depicting stoic sincerity but wasn’t exactly associated with the dangerous protagonist of the books. It is hard to dispel the mental image of his 007 jovially smoking a pipe and upbraiding the fiendish doctor for not wearing a tie.

The producers approached James Mason and Cary Grant, but they were both too old and disinclined to be tied to a long-term contract. Of the younger performers under consideration, Rod Taylor later stated that he spurned the role as beneath him – ‘That was one of the greatest mistakes of my career!’

Patrick McGoohan, who later starred in The Prisoner, was a logical choice, as he was then famed for playing John Drake in ITV’s Danger Man.

However, 007 did not accord with his beliefs. The actor told the press the role had ‘an insidious and powerful influence on children’.

So the search continued, from William Franklyn, the future face of Schweppes commercials, to Patrick Allen, ‘king of the voiceovers’.

The most plausible casting choice was Richard Johnson, an associate artist of the Royal Shakespeare Company recommended by Terence Young, director of Dr No. Like Connery, he was dark and saturnine, but Johnson used his MGM contract to reject the role.

A low-budget but ambitious spy drama entitled Danger Route gives an impression of how a Johnson 007 could have been more world-weary, cynical and aggressive than the immaculately tailored MI6 agent.

History relates that Connery gained the role, impressing the producers with his physical grace. His fee was also less than that of Cary Grant, a significant consideration, given the limited funds.

The reviews for Connery’s first outing as Bond ranged from ‘Every male will instantly identify with this devastating he-man’ (Tatler) to ‘an Irish-American look and sound which somehow spoils the image’ (Times) and ‘wooden and boorish’ (Monthly Film Bulletin). Box-office receipts in the UK told their own dazzlingly successful story.

Six decades later, overfamiliarity with the 007 franchise can often obscure how revolutionary Dr No appeared in the context of 1962 British cinema.

The studio back projection behind our hero’s Sunbeam Alpine can look unconvincing, and some cast members sound as though they were post-synched by another actor. But Connery’s performance was the critical element in its success. He was not an unknown leading man but lacked an established screen image, allowing him to create the template for the cinematic Bond, against which audiences judged his successors.

That said, Oliver Reed would have been a splendid 007. And Peter Snow might have made the many longueurs of Moonraker enjoyable.

David Niven’s moustache seemed to wilt with embarrassment

K arl Lagerfeld – or ‘the Kaiser’ – was my first boss in Paris.

Though proud of this great feat, I won first prize as his lousiest assistant at the Chanel Studio. It was 1989, the height of the supermodel and the French luxury brand. Chanel’s tweed suits, little black dresses and handbags were whizzing out of their boutiques.

But, being Karl, he thought it was tremendously funny that I was a dilettante. ‘You spent your life on the telephone,’ the German designer later teased me. Hard to believe, but while he was adding pearls, satin camellias and other accessories to the lithe limbs of supermodels such as Linda Evangelista, Claudia Schiffer and Naomi Campbell, I was busy gassing to my dark-haired Notting Hill Gate-based girlfriends, nicknamed ‘the moustaches’ by The Crown’s Peter Morgan.

Occasionally, the then 56-year-old Karl turned in my direction and smiled broadly. Contrary to his sourpuss reputation, he favoured the different and had an infectious sense of humour.

Veruschka – the celebrated 1960s model – described him as a 19th-century gent who wore his immense culture lightly and was both generous and affectionate.

A journalist’s dream, the well-read and charismatic Karl never forgot a name or an insult; he seduced by being witty and outspoken in four languages: English, French, Italian and his native tongue. He also had a tremendous joie de vivre and urge to share.

Reading the new book Hidden Karl and seeing Robert Fairer’s photographs of the Chanel years in the 1990s and 2000s, I was reminded of the euphoria Karl encouraged among his team and the models. ‘Fashion has to be fun –otherwise what’s the point?’ he often said.

True, Karl lied about his age – born in 1933, he knocked off five years – but it’s hard not to agree with Marie-Louise de Clermont-Tonnerre, the retired Chanel executive, that ‘he was a godsend’ for the fashion house:

‘I was working there when Gabrielle Chanel passed away and the bloodless atmosphere was compared to the Kremlin, just after Stalin died,’ says the spritely 80-year-old.

Indeed, Karl’s winning flair, Teutonic discipline and precision revolutionised Chanel. For 36 years, he revamped the house’s heritage and codes and turned Chanel into a must-have brand from 1983 until 2019 when he died at 85, with his boots on.

It was Anna Wintour’s idea that I work for Karl. As was her way, she faxed Gilles Dufour, Karl’s bras droit, in September 1989.

A meeting was arranged but, although every Parisian I met enthused, ‘Karl will looove you,’ I wasn’t so sure. He’d had a much-publicised bust-up with Inès de La Fressange, his former muse.

And then, after two months, it happened. Or rather Anna intervened. That first meeting with Karl took place in November 1989 at the Chanel Studio on the Rue Cambon. The receptionist called to announce his arrival. Among my Chanel Studio colleagues – Virginie Viard, Victoire de Castellane, Armelle Saint-Mleux and Franciane Moreau – I noticed jewellery was added, lipstick was applied and high heels were slipped on. Suddenly, a fleet of white canvas tote bags appeared, delivered by Brahim, Lagerfeld’s then chauffeur (who was eventually fired for flogging handbags on the side).

The ceremony was regal – followed by Karl, who was sporting a forest-green Loden coat. Quite plump and small, he refused to look at me in the eye. Instead, Karl pushed his sunglasses up, peered down and chose to comb through a tote packed with papers, crayons and pencils.

Placing his coloured sketches on his desk, he revealed he’d met my mother (the writer Antonia Fraser) and my grandmother (the writer Elizabeth Longford) at the house of their publisher, George Weidenfeld, cofounder of Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Seasoned to the creative, I instinctively liked Karl. I decided that he was irked by the disruption, being keener to work. Yet, in spite of the mild gruffness, he was touching. When he was leaving, Gilles needed to help him put on his coat. Karl blamed his surprisingly short arms on an unfortunate family characteristic. Of course, I kept such observations to myself. Karl was a king, surrounded by courtiers eager to repeat stories and win favour.

A few days later, Karl looked at my decoupage jewellery and scarf designs. After choosing two pairs of earrings, he focused on my fabric that depicted a teapot pouring out jewels.

Taking an A3 piece of paper and a thick pen, Karl sketched and marked out how the teapots should be placed. The following season, my double-C teapots were splashed across a black satin silk fabric, manufactured by Cugnasca in Italy, and used for Chanel blouses, jackets and skirt linings.

Two more prints followed. One showed hand-drawn double-C cards mixed in with pearls and diamond tears. The final one boasted double-C clocks flying on jewelled wings.

Apart from these three successful yet unpaid endeavours, I was more of a studio mascot than a helpful assistant. Karl described me as ‘a good-natured, belle-époque actress’. Being a keen amateur photographer, he took my portrait several times.

There were magnificent, candlelit dinners – held either at his Rue de l’Université apartment or at Lamée, a country house outside Paris. An enthusiastic collector of the 18th century, Karl was a walking encyclopaedia about the period. He was a skilled host, too, among his soigné and international guests.

Looking back, I see that those soirées captured how high fashion was still wrapped up in Parisian society. Karl straddled both worlds, seamlessly – as did his ex-friend Yves Saint Laurent. The designers had fallen out over Jacques de Bascher, Karl’s boyfriend, and the rift widened further. There was even a sense that Paris was divided between Yves’s camp and Karl’s.

Meanwhile, the only time I was

Karl gave Natasha an 18th-century diamond brooch for her 1997 wedding

Karl used to say that Antonio Lopez had no equal with regard to his fashion drawings. However, Karl was capable of sketching and imitating every single designer’s style. Swiftly achieved, his drawing was fascinating to watch.

Naturally, there were dramas. During the 1991 fall winter couture show, Linda and Christy Turlington brandished Lesage-embellished redingotes and matching, thigh-high boots. Certain flaps had not been closed. Ravishing as they looked, their underwear was revealed. The show was unveiled at the Ritz.

And I remember overhearing Princess Caroline of Monaco joke, ‘Well, I guess, next season we need to show our panties.’

Poor Colette – in charge of the offending atelier – was fired. It seemed odd for such a professional seamstress, and I wondered if the looks had been sabotaged. Karl had never liked Colette.

No question, there was a darkness to Karl. Yet, in general, those days were light-hearted and fun. A twilight period in Parisian fashion, it was a time when individual creativity reigned.

The design of clothes outshone handbags. Parties were spontaneous, raucous and inclusive. Eccentric and/or bratty behaviour towards the press was tolerated.

Four years later, it would totally change. Hubert de Givenchy was the first to retire in 1995. He sold his house to Bernard Arnault – the luxury titan –who had already acquired Christian Dior, Christian Lacroix, Louis Vuitton and Celine. It was the beginning of major money in fashion and major corporations offering Faustian pacts to creators.

cattle-pronged into action – usually by Gilles – was when Karl produced his Chanel shows.

During those periods, Gilles distributed his original sketches to the various ateliers. Two personal favourites were Monsieur Paquito –responsible for Chanel’s couture suits – and Madame Edith, who’d worked with Mademoiselle Chanel and created ready-to-wear flou dresses.

Meanwhile, a lengthy, portable screen was pinned with photocopies of Karl’s sketches. If only I’d photographed them. Each one was delicately coloured with Chanel make-up, while the buttons and trim were accented with a gold pen.

Instead of nose-diving like his nemesis Saint Laurent, who disappeared into a sea of drugs and alcohol, Karl shed 65 pounds and forced Chanel to go global.

Mastering the internet helped his cause, as did spectacular fashion extravaganzas and an addition of commercial collections such as Cruise.

As Robert Fairer’s photographs attest, Karl Lagerfeld was utterly unleashed when he reinvented Chanel for the 21st century.

Karl Lagerfeld Unseen: The Chanel Years (Abrams) by Robert Fairer is out on 20th October

T he word of the decade – here’s hoping it isn’t the word of the century – is a Latin hybrid.

Coronavirus comes from the Latin corona (‘crown’) and the Latin virus, originally meaning a poisonous secretion from snakes – ie a kind of venom.

Used together, though, the words corona and virus these days have only one miserable meaning. Scientists gave the virus the name because those knobbly bits on the surface of the virus are like the crests and balls of a crown.

Once again, even with the worst of modern horrors, it is the Latin language that put it first and put it best – unless ancient Greek got there first, by lending its alphabet to those horrible virus variants like Delta and Omicron.

Latin lives on in some corners of Britain – even where it shouldn’t. Justin Warshaw QC, a family lawyer, still finds Latin useful in his work:

‘The law is a goldmine of great Latin tags. Legal Latin was apparently abolished by Lord Woolf in 1999, acting pro bono. Thankfully, the judgment was interim and, mutatis mutandis, major reforms have been avoided.

‘The forum is still conveniens, habeas corpus invoked, the Carta remains Magna and the guilty has mens rea for his actus reus.’

And there still is plenty of Latin left in everyday, non-legal life; words we use without thinking of them being Latin, so embedded are they in the English language – from doctor to bonus; from major to minor.

We rarely stop to think what extraordinary survivals they are: completely intact words transported all the way from ancient Rome, unsullied by a journey across a continent and several millennia.

Latin isn’t an austere relic to be

worshipped behind glass, at a distance or in a museum. Latin is there to make you laugh, move you to tears and charm you by its beauty and cleverness. But by its pleasing cleverness, not its scary cleverness.

That pleasing cleverness is why

late Queen did it in her speech at the Guildhall in 1992: ‘In the words of one of my more sympathetic correspondents, it has turned out to be an annus horribilis.’

Elizabeth II’s ancestor Elizabeth I was even keener on the Latin language.

Amazingly, her Latin handwriting

We all know a bit of Latin – and there are lots more lovely words and lines out there to enjoy. By Harry Mount and John Davie

motto was a charmingly simple one: Semper eadem ‘Always the same.’

It wasn’t just in 16th-century England that Latin was so popular.

Across Europe in the Middle Ages, Latin was the intellectual lingua franca: a bridge language or ‘Frankish language’ – as in the Franks, the word used for Western Europeans in the late Byzantine Empire. So William of Ockham (1285-1349) used Latin for his rule, Ockham’s Razor:

Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem.

‘No more things should be presumed to exist than are absolutely necessary.’

Three hundred years later, the French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) was using Latin for his principle, Cogito, ergo sum. ‘I think, therefore I am.’

Also in France, a little earlier, the philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) was a Latin obsessive, as was his father, who wanted his son to have Latin as his first language.

In his father’s Bordeaux château, servants were ordered to speak to little Montaigne in Latin only, as his mother and father did, too.

Montaigne became fluent in Latin and had Latin and Greek quotes painted on the roof beams of his library.

Among them was this one:

Solum certum nihil esse certi et homine miserius aut superbius. ‘Only one thing is certain: that nothing is certain – and nothing is more sad or arrogant than man.’

Enoch Powell, a Greek professor at Sydney University at 25, turned to Latin, too, for his – very horribilis – 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech.

When he declared, ‘Like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood”,’ he was quoting Virgil. He was referring to the passage in The Aeneid where the Cumaean Sibyl predicted to Aeneas that a war in Italy would turn the Tiber red with blood.

Bella, horrida bella, Et Thybrim multo spumantem sanguine cerno.

‘I see wars, horrible wars and the Tiber foaming with much blood.’

Virgil, the Aeneid

In Withnail & I (1987), Withnail (Richard E Grant) and Uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths) also use Latin to add spice to their drunken game of poker.

They alienate Marwood (Paul McGann) by speaking in Latin:

Uncle Monty: Nonne solus cedetur? (‘Surely, only Marwood will lose.’) Withnail: Reginae servandae defit. (‘He’s short of the queen that can save him’ – Camp Uncle Monty giggles at the idea of a queen coming to the rescue.)

For all the high-minded pleasure these little bursts of Latin give when they’re dropped into English, the Romans didn’t think it was such a high-falutin’ language. Latin was used by the Romans in the most wonderfully vulgar, low-falutin’ way.

Take this graffiti found at Pompeii:

Lucilla ex corpore lucrum faciebat. ‘Lucilla made money from her body.’

On a nearby wall, someone wrote,

Sum tua aeris assibus II.

‘I’m yours for two bronze coins.’

It wasn’t just rude words they loved to write. In the Domus Tiberiana in Rome,

there’s a crude picture of a man with an oversized penis for a nose. Graffiti artists also drew dogs, donkeys and horses. But they liked phalluses most.

And real, day-to-day Roman Britain comes vividly, graphically to life in the Latin letter sent from warm, southern Gaul to a frozen legionary in Vindolanda, Northumberland, listing the contents of his support package:

Paria udonum ab Sattua solearum duo et subligariorum duo.

‘Socks, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants.’

In other Vindolanda letters, Roman legionaries long for luxury items from back home: Massic wine (a fine Italian vintage), fish and olive oil – the ideal Mediterranean diet. And they turn their noses up at the local Pictish fare: cereal, spices and venison.

There are many mentions, too, of cervesa and callum – that is, beer and pork scratchings, and all 1,000 years before the British pub was invented.

Because the teaching of Latin, so unfairly, has been increasingly restricted to private schools and grammar schools, it’s wrongly thought of as a ‘posh’ language. That impression is deepened by Latin’s use in mottoes and for inscriptions on grand buildings.

But, as that Roman graffiti in Pompeii shows, people swore in Latin; they haggled with prostitutes in Latin; launderers wrote their laundry signs in Latin. And, also, some of the finest poetry ever written has been in Latin.

We all speak a bit of Latin already, whenever we watch a video, go to the circus or follow the media.

And there are lots more lovely Latin words and lines out there.

All you have to do is follow St Augustine’s advice in his Confessions in the 4th century AD:

Tolle lege, tolle lege ‘Take up and read, take up and read.’

* Vivat Latin! – ‘Long live Latin!’

Cosmo Landesman’s son belonged to a tribe of lonely, young addicts who never get started in life before they end it all

When my son Jack was a small boy, I carried him on my shoulders – and I carried him in my heart – everywhere I went.

But then the small boy became the troubled teenager and the troubled teenager became the tragic young man: Jack killed himself in 2015, aged 29.

What happened? Life happened. Somewhere between his teens and his twenties, Jack (my son with my ex-wife, writer Julie Burchill) became one of those Lost Boys who get stuck in a life-long adolescence. They never grow up, preferring to give up on life – before they’ve begun to live.

These are tough times for young men – as the disturbing rates of suicide and the growth in mental-health problems show. Lost Boys like Jack are often depressed, self-destructive, addicted to drugs, lost and lonely. You can see them on the streets begging for money or sleeping rough – these sad Lost Boys with no way home.

It’s funny how one minute you have a sweet boy who fills your life with sunshine and joy. The next, you have this pot-smoking, lazy lump of a son with crazy tats and piercings who sits all day on the sofa doing nothing in front of a computer screen.

And you wonder: where did my sweet boy go?

Time passes. Life changes. But Lost Boys stay the same. Parents tell themselves it’s just a phase they’re going through: no need to worry. Meanwhile, their son’s peers are making progress –going to university, finding partners and finding jobs.

I remember a friend boasting about how his son had got into Oxford – and I boasted back that my son had got into Britain’s top rehab place, the famous Priory.

Black humour helps ease parental worry – until you discover your son is doing heavy drugs, drinking too much

and starting to talk about suicide.

That’s when the dark, fearful thoughts start to turn up – usually around 3am. You know you have to do something to save your Lost Boy; but you don’t know what to do.

Lost Boys are often bright and get a place at university or art school – and then suddenly for no reason drop out.

Parents tell themselves it’s only a matter of time before their Lost Boy finds himself. They don’t understand that he doesn’t want to find himself: he wants to obliterate himself with drink and drugs. Anything to quieten those voices of hurt and self-hate that rage inside his head.

And the parents of these Lost Boys don’t understand what happened to their boy: ‘He was so clever and gifted.’ Lost Boys are very creative when it comes to making music or painting or writing. They often have the dream of playing in a band, and they’re always in the process of ‘getting a band together’, ‘making a demo’ or ‘doing some gigs’. They’re always on the brink of doing something – and end up having done nothing.

These Lost Boys have the dream but not the self-discipline to make it come true. They are too fidgety to focus on a career; too self-centred to work with others. Consequently, they feel like failures – but tell the world they don’t give a f**k. That’s just their hurt talking.

Lost Boys are impossible to live with and impossible to let go of. First they break your house rules and then they break your heart. They beg you for money and a second chance and promise a new beginning.

‘This time,’ they insist, ‘things will be different – you’ll see.’ And it’s always the same.

I confess that I kicked my Lost Boy out of my flat. We rowed so much and his drug usage was out of control. I couldn’t stand living with Jack. I called it ‘tough love’ – I soon discovered that there’s nothing tougher than standing by and watching someone you love screw up their life.

Many Lost Boys become homeless, surfing the sofas of friends, sleeping rough and living on state benefits and their wits. They beg and steal. They buy and sell drugs. And the sad thing is they lose their kindness and then their moral compass.

Lost Boys can be very sweet and charming – but also rude, selfish and uncaring about others.

Parents do the best they can. They get their Lost Boy on medication – and he comes off his medication. They get him into therapy – and he quits therapy. He comes off drugs and goes back on drugs.

And so the cycle of fresh starts and failed attempts goes on and on until you cry, ‘I give up! Sort out your own life!’

If I had a fiver for every time I said that to Jack, I would be a rich man.

Lost Boys are difficult to sympathise with. They are often middle- and upper-class kids who were given every opportunity in life – and managed to screw up every opportunity that came their way.

The good news is that some Lost Boys eventually find themselves and make something good out of life.

The bad news is that some Lost Boys are so lost that, like my boy, they decide to kill themselves instead.

Jack and Me: How NOT to Live After Loss (Eyewear Publishing, £20) by Cosmo Landesman is out now

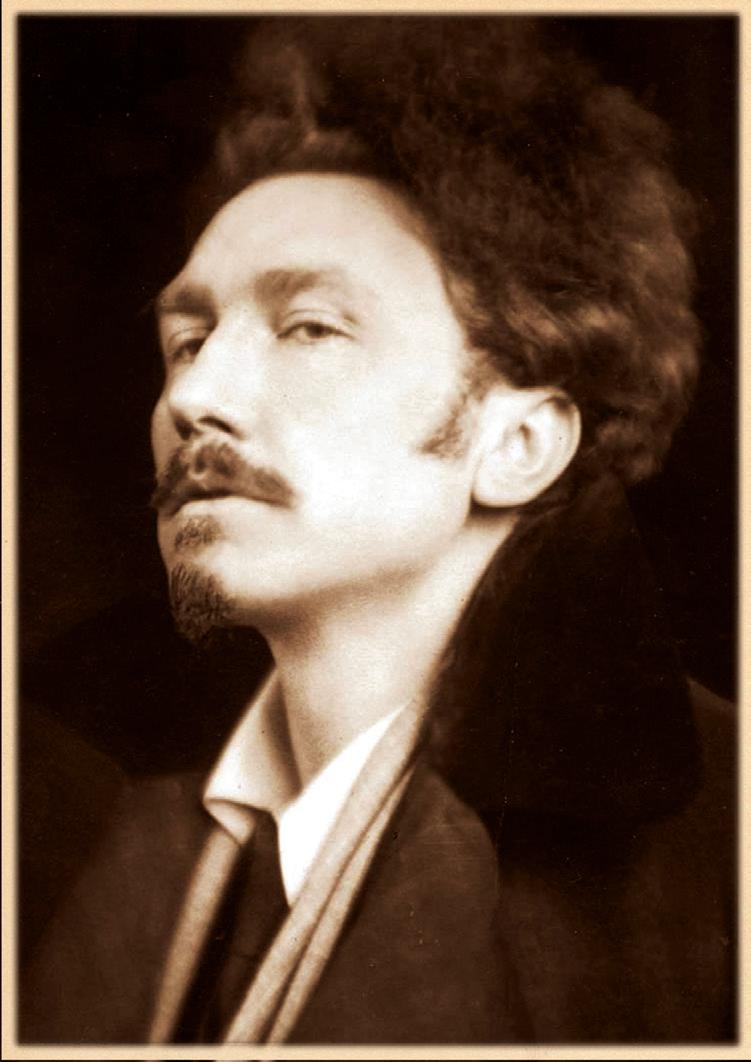

On his 250th anniversary, a statue of the poet will be erected in Ottery St Mary, his Devon birthplace. By Drew Clode

On 21st October, a statue of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) will be unveiled, 250 years to the day since his birth in 1772.

It will stand in the local church in his small, thriving home town: Ottery St Mary, tucked away in a pocket of countryside in deepest south-east Devon.

The town was his birthplace. It speaks volumes that the church and community are honouring the author of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan with such a tribute.

The statue, sculpted in bronze by Nicholas Dimbleby – the youngest of the three brothers – will be unveiled at 11.30am, the exact time of the poet’s birth 250 years ago. Pictured below is his clay model of Coleridge’s head.

It will stand, life-size, on the edge of St Mary Ottery’s south wall, staring at the exact spot, not 100 yards distant, where the young Samuel first drew breath.

The statue of the poet will dominate your view as you climb the ancient brick steps into the churchyard and walk up to meet him face to face. At last, he has come home.

Coleridge spent the first nine years of his life in Devon, roaming the banks of the Otter and playing in the churchyard at St Mary’s. He embarked on his prodigious learning in the schoolhouse. It was just yards from the house where he had been born and his father, John, was headmaster.

Coleridge by Nicholas DimblebyJohn was also the village minister, and baptised his youngest and last child at the font in St Mary’s Ottery in December 1772. The church is a glorious edifice –‘lying large and low like a tired beast’, according to Pevsner – modelled in part on Exeter Cathedral.

In 1782, his mother’s fear of poverty following his father’s death drove the young Sam away to school: to Christ’s Hospital, a charity school then situated to the east of St Paul’s in London. He later wrote of his ‘weeping childhood, torn by early sorrow from my native seat’.

During his school days, he returned only three or four times to the village and to a troubled relationship with his mother and siblings. Apart from a near-calamitous attempt at an Otterybased reunion with his favourite brother, George, in 1807, there is no evidence that he ever returned again.

Meanwhile, according to his biographer Richard Holmes, ‘Coleridge had become, in effect, the black sheep of the family, and a proverb among his brothers for profligacy and lack of discipline.’

He died in July 1834 in London’s Highgate and lies with his wife, daughter, son-in-law (and nephew) and grandson in a derelict cellar beneath St Michael’s, the local parish church.

There is no evidence that he ever wished to be buried in what has become the ancestral church at Ottery St Mary. And there’s no evidence that his family there opposed the burial in Highgate – he wasn’t the family favourite because of his opium-taking and, to put it mildly, his eccentric attitude to marriage and family life.

But anecdotes can have a persuasive force all of their own. As late as the 1920s, a member of the family was confiding to a Canadian academic –Kathleen Coburn – that ‘the old reprobate’ was a bit of a disgrace: ‘All those badly written scribblings –couldn’t even write a decent hand that

ordinary people can read – full of stuff and nonsense.’

But this all happened long ago. This October, his descendants and the residents of Ottery St Mary will have brought to reality a 140-year-old dream (the statue was first mooted in 1882).

They have returned the poet to his home town, magnificently sculpted in bronze, standing exactly where he spent so many of his happiest years, reading, moping or occasionally absorbed in Gothic re-enactments of the hundreds of stories he’d precociously read.

It wasn’t easy. Fundraising was an arduous, non-stop graft. Seeking and obtaining the various permissions were exhausting. The church stands on Church of England land, situated in a conservation area. The Diocesan Advisory Committee, East Devon County Council, the church governors and Historic England all had to be convinced of the rightness of the case.

There were endless questions. The sculptor had to be chosen and the best position agreed. There were discussions of how the statue would look – and what was the choice of material and the best type of stone to sit in this particular soil.

All these challenges more than took up the nine years needed to bring this passionate idea to this month’s brilliant, moving climax.

Coleridge’s great-great-great-great grandson Richard, due to become chair of another trust devoted to refurbishing the poet’s tomb, has thanked many people in Ottery and further afield who helped this project through to its conclusion.

Richard Coleridge said, ‘The real tribute, thanks and gratitude belong to Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

‘His contribution to our literature, our theology and our philosophy, and the ideas that this man, from this small town, brought to his country and the world are unique and, along with this statue, bear witness to the greatness of the man himself.’

‘Ihave seven grandchildren. They all went to university.’

‘Oh really. I have seven grandchildren, too – three vegans, two transgender, one hunt saboteur and one with a job title of six words, none of which I understand.’

‘I keep calling my wife Molly. That’s our dog’s name.’

‘Well, I frequently call the man in the newsagents darling.’

‘I’m still waiting for my cataract operation.’

‘Sorry – I missed that. You’re talking into my bad ear.’

‘I got up three times last night to go for a pee.’

‘I got up three times and the third time I lost my way back to the bedroom. Found myself trying to get into the garden.’

‘I reckon this jacket will see me out.’

‘See these shoes? I bought them in 2002. Good as new.’

‘Of course, I need subtitles for everything on the telly these days.’

‘I counted. I have to take 11 pills every day.’

‘Me too. I take 11 pills. The doctor has just given me this new one. What do you think of this? Purple and yellow stripes. Like a regimental tie. God knows what it’s for.’

‘My nostril hair has turned white.’

‘It was a shock to discover that my son has been a subscriber to The Oldie for five years.’

‘I had a turn last Thursday.’

‘Well, I had an episode.’

‘I’m on my third new knee.’

‘Really? I’ve lost count of my hips.’

‘Last month, I went to three cremations, a scattering and two memorial services.’

‘I just went to four cremations. The fourth was a mistake; I arrived too early at the crematorium and went to one for a perfect stranger. Rather a good service, actually.’

‘Time for my lie-down.’

‘Sorry, I didn’t catch that. Must have

The Oldie Annual 2023 A4 PB 192pp £6.95

Et Tu, Brute? Harry Mount and John Davie Signed copy £14.99 HB 264pp

Bliss on Toast Prue Leith £14.99 HB 192pp

The cost-of-living crisis will push millions of people in Britain into food poverty. The predictions grow more apocalyptic by the day. Private Fraser in Dad’s Army was right. We’re all doomed. Doomed.

But hold on. We’ve been here before – and in far more threatening circumstances. In two world wars, Germany’s submarine offensives tried to starve Britain into submission.

In both cases, allotments came to the rescue – not completely, but they did make a significant contribution to the nation’s larder. They enlisted civilians in a war effort which was also a great morale-booster, with the pithy slogan ‘Dig for Victory’.

There is no sign that the Government is considering the wartime measures to requisition land for extra allotments. But the National Allotment Society (NAS) is quietly preparing for a huge surge in demand for plots from desperate people who can no longer afford to buy all the food they and their families need. It had a full dress rehearsal when COVID struck and demand soared.

The President of the society, Phil Gomersall, says 60 new allotment sites are going to be provided by housing developments as part of their recreational facilities. Each site can provide up to 100 plots. Many existing sites, including his in Leeds, are considering breaking up standard plots into two or four smaller ones which are more suitable for modern families.

The standard plot is 360 square yards, the size set in Victorian times as sufficient for a working man to feed his family with fruit and vegetables throughout the year. That’s nearly five times the size of a cricket pitch.

Local authorities are becoming more allotment-friendly as they realise their benefits go beyond fruit and veg to

improved physical and mental health and stronger community spirit.

Gomersall says, ‘Councils see these benefits come without a financial or administrative burden on them as allotments are self-financing and we are encouraging them to be self-governing.’

The ad-hoc Victorian allotment movement was formalised in the 1886 Allotment Act, which licensed local authorities to provide allotments.

The number peaked in the Second World War, with 1.4 million plots nationwide. They gradually fell out of fashion afterwards as people became more prosperous, falling to a low point of 265,000 in 1997.

The first event to reshape the allotment world was the BBC comedy The Good Life (1975-8). Richard Briers and Felicity Kendal played a middleclass couple who drop out of the rat race and try to become self-sufficient by turning their suburban garden into an allotment.

The series ditched the stereotype of the allotmenteer as an old, curmudgeonly, cloth-capped working man in favour of the aspirational middle class in search of a purity of purpose. Thousands

enthusiastically flocked back to the land – including me. I started my allotment 45 years ago, in 1977.

In the early 2000s, women began to discover allotments. They were almost completely absent in the old days, but now they came in search of healthier food for their families during a spate of food scares. They often bring their children with them, swathes of colour from the flowers they grow and greater sociability.

The old curmudgeons grumble about noisy children running around as if the allotments are a playground. But they do no harm, and childish laughter is as joyful a sound as the birds’ dawn chorus in spring. They will grow up associating allotments with fun and happiness.

There are now 330,000 plots in cultivation. The number of plots is growing – but so are the waiting lists for newcomers. The average wait is about five years. The longest was 18 years, in Camden in north London, before the plot in question was allocated in 2020.

The NAS estimates that the typical cost of running a standard plot is £247 a year, producing crops worth nearly £2,000 from 203 hours’ work. That averages out at only four hours a week.

I spend only half that time working, so take less in crops. Still, I spend much more time on the plot, pottering about, socialising and relishing the tranquillity.

The future looks challenging but, as Gomersall says, ‘Allotments will always be good for the nation’s health, wealth and happiness.’

I am determined, too, to find an upside to the other existential crisis looming over us; global warming. I’ve sketched a new allotment plant layout for when Britain develops an Italian climate. There’ll be a small grove of olive trees and a fig or a pomegranate under which my fellow plotters and I can gossip and shelter from the sun.

Most importantly, I will have a minivineyard where l will make a delicious and cheeky Vino Osborne. Cheers!

‘To betray you must first belong. I never belonged.’

So said Kim Philby in defence of having secretly thrown in his lot with the Soviet Union in the 1930s.