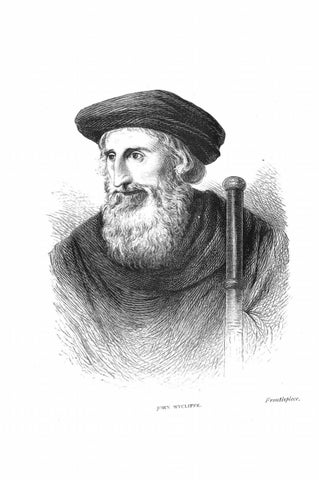

Fron ti.tpirn¡.

Anonymous, Life and Times of John Wycliffe. The Morning Star of the Reformation.

Issuu converts static files into: digital portfolios, online yearbooks, online catalogs, digital photo albums and more. Sign up and create your flipbook.