April 2013

www.TheOncologyNurse.com

Vol 6, No 3

Side Effects Management

Cancer Center Profile

Center for Cancer Prevention and Treatment at St. Joseph Hospital Nurse Navigators and the Continuum of Care

New Developments in the Management of Hand-Foot Syndrome Associated With Oral Anti-VEGF Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor–Targeted Anticancer Therapies By Joanna Schwartz, PharmD, BCOP, and Shannon Hogan, PharmD Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences—Vermont Campus Colchester, Vermont

H

and-foot skin reaction (HFSR), also known as hand-foot syndrome or palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE), is an adverse effect of several chemotherapeutic agents. The syndrome is characterized by redness, swelling, pain, and tingling in the palms

of the hands and the soles of the feet. Other symptoms may include sensitivity or intolerance to hot or warm objects or fluids, hyperkeratosis (callus), blistering, and dry skin. Callus-like thickened tender blisters with some surrounding Continued on page 31

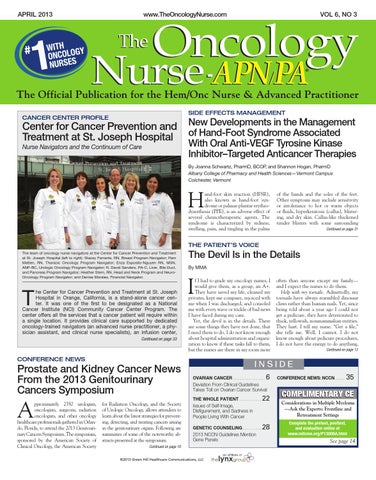

The Patient’s Voice The team of oncology nurse navigators at the Center for Cancer Prevention and Treatment at St. Joseph Hospital (left to right): Stacey Ferrante, RN, Breast Program Navigator; Pam Matten, RN, Thoracic Oncology Program Navigator; Enza Esposito-Nguyen RN, MSN, ANP-BC, Urologic Oncology Program Navigator; R. David Sanders, PA-C, Liver, Bile Duct, and Pancreas Program Navigator; Heather Stern, RN, Head and Neck Program and NeuroOncology Program Navigator; and Denise Morales, Financial Navigator.

T

he Center for Cancer Prevention and Treatment at St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California, is a stand-alone cancer center. It was one of the first to be designated as a National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Cancer Center Program. The center offers all the services that a cancer patient will require within a single location. It provides clinical care supported by dedicated oncology-trained navigators (an advanced nurse practitioner, a physician assistant, and clinical nurse specialists), an infusion center, Continued on page 33

The Devil Is in the Details By MMA

I

f I had to grade my oncology nurses, I would give them, as a group, an A+. They have saved my life, cleaned my privates, kept me company, rejoiced with me when I was discharged, and consoled me with every wave or trickle of bad news I have faced during my care. Yet, the devil is in the details. There are some things they have not done, that I need them to do. I do not know enough about hospital administration and organization to know if these tasks fall to them, but the nurses are there in my room more

Conference News

Prostate and Kidney Cancer News From the 2013 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium

A

pproximately 2350 urologists, oncologists, surgeons, radiation oncologists, and other oncology healthcare professionals gathered in Orlando, Florida, to attend the 2013 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. The symposium, sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Society

for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Urologic Oncology, allows attendees to learn about the latest strategies for preventing, detecting, and treating cancers arising in the genitourinary organs. Following are summaries of some of the noteworthy abstracts presented at the symposium.

often than anyone except my family— and I expect the nurses to do them. Help with my toenails. Admittedly, my toenails have always resembled dinosaur claws rather than human nails. Yet, since being told about a year ago I could not get a pedicure, they have deteriorated to thick, yellowish, nonmammalian entities. They hurt. I tell my nurse. “Get a file,” she tells me. Well, I cannot. I do not know enough about pedicure procedures, I do not have the energy to do anything, Continued on page 13

inside Ovarian Cancer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6

Deviation From Clinical Guidelines Takes Toll on Ovarian Cancer Survival The Whole Patient. . . . . . . . . . . .

22

Issues of Self-Image, Disfigurement, and Sadness in People Living With Cancer Genetic Counseling. . . . . . . . . .

2013 NCCN Guidelines Mention Gene Panels

Continued on page 10 ©2013 Green Hill Healthcare Communications, LLC

28

Conference News: NCCN. . . . . . .

35

Complimentary CE Considerations in Multiple Myeloma —Ask the Experts: Frontline and Retreatment Settings Complete the pretest, posttest, and evaluation online at www.mlicme.org/P13008A.html

See page 14