T R E L A D

RE

e

th w o h s show . e r u l i fa ay s ’ w m s t a i r t rog los p s y a r h e v e reco ife Servic f l o w A ldl i W d n Fish aNASH HEN BY STEP

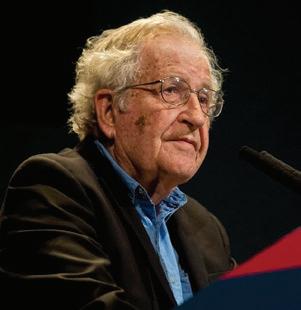

Not long ago, I rolled into windblown Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, seeking to renew an old acquaintance—with a program aimed at rescuing the red wolf, a critically endangered species, from extinction. The refuge is in a boggy and buggy section of coastal North Carolina, a wide amber floodplain of tall reeds and scrub trees. It is only sparsely inhabited—unless you count otters, cottontails, raccoons, and a long list of shorebirds. There’s a significant population of black bears here, too. One stared me down along a dirt road in the refuge before it made a leisurely pivot and ambled off into a thicket. This is also home, just barely, to Canis rufus, the rarest kind of wolf on the planet. I called the offices of the refuge, whose website invites visitors to occasional “wolf howlings,” but I was told that the program has been discontinued. Indeed, wild red wolves may themselves soon be discontinued. Fossil evidence indicates that red wolves inhabited the region from Florida to New York and west to the Mississippi River for nearly all of the past ten thousand years. But they’ve arrived at the edge of extinction in the wild now because of a derelict federal agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Paradoxically, it is the same agency that once rescued them. The program’s near-collapse is emblematic of a hunkered-down Service, its upper-level administrative culture long broken. Through several national administrations, the agency has been chronically allergic to controversy about endangered species, often ready to kneecap its own mission with delays, evasions, and capitulations. Stephen Nash, a visiting senior research scholar at the University of Richmond in Virginia, is the author of Grand Canyon for Sale: Public Lands versus Private Interests in the Era of Climate Change.

52 | DECEMBER 2020 / JANUARY 2021