THE STREETS

A Street Photography Magazine

And when I say artist, I don't mean artist the way you might think of artist.

When I say artist, I mean somebody who does human work, unpredictable work –makes a connection with someone else and changes them for the better."

– Seth Godin, Author"There is a new class of person – an artist.

Photograph by Meredith M Howard

Photograph by Meredith M Howard

Front cover photo Back cover photo

Editor and Creative Director Creative and Digital Assistant Marketing Consultant Photography Assistant Copy Editors

Special thanks to Contributors and collaborators Website Email Instagram

Publisher ISSN

Tony Maake Patty Jansen

Meredith M Howard Eva Howard Christi Rhyne Julieann Tran Shelley Wunder-Smith and Alicia Kramer Greg Howard and Elise Howard Picolo Diop Artina Emma Zeck H Gay Allen Matthew Stromer Matthew W Warren Ako Julieann Tran Mercedes Bleth Alex Torrey Jyotik Bhachech Kevin Fuentes Cordaro Gross Aimee Labrecque Yan Zheng Eduardo Asenjo Matus Ricardo Delgado López Umcolisi Terrell Chris Veal Mark Miller www.thestreetsmag.com info@thestreetsmag.com @thestreetsmagazine

James Meadows Henry J Parsons Drew Brucker Courtney Jones Howard Levenson Krista Gill olive47 Mary Farmer Lela Brunet Janice Rago Patty Jansen Jennifer McKinnon Richman Dániel Horváth Terence Lester Matt Yung Arlene Brathwaite Elizabeth Bloodworth

Tony Maake Stefan Els Martijn Roos

Meredith M Howard LLC 2476-0927

All work is copyrighted to the photographer, artist, or author. No part of this magazine may be used without permission of THE STREETS.

We didn't have to print this book. We could have just let it exist amorphously in the digital world. Printing is expensive, time-consuming, and – these days – unexpected.

But we want you to have the experience of sitting down and holding this book in your hands, flipping the pages, and enjoying the art in a real, physical way. We want this book to be an extra connection with the community, an encouragement to the artists, and an inspiration to "normal" people who want to do extraordinarily creative things.

This 2018 Collection is full of people "doing the work they didn't have to do" because of the love of the art, the people, and the connections. Seth Godin calls it "generous work" – people sacrificing short-term comforts, time, and money to make long-term change and contributions.

Generous work appears in many different forms. Generous work is a street photographer noticing the value in a stranger and telling that person's story in a way that builds a bridge of empathy. Generous work is a group of artists devoting an entire weekend in the hot sun to create a free outdoor gallery of murals, so that when you drive by, you will smile and think about life in a different way. Generous work is a group of people moving out of the suburbs to Historic South Atlanta in order to transform the neighborhood from the inside out. Generous work is making it out of poverty and then going back to pull others out, too.

Generous work is fueled by love. And when love is involved, the work becomes a gift – both to the recipient and the giver. That doesn't mean the work was free, because sometimes there was payment and usually there was sacrifice. But generous work breathes life into the world. So, we hope that this book full of gifts by these generous contributors encourages you and delights you and inspires you to do your own generous work.

"So much of the future is going to be done by people doing the work they didn't have to do."

– Scott Belsky, Entrepreneur and Author

"A labor of love has a way of paying off. Just not in the way you would expect."

– Scott Belsky

"People tend to see what they want to see."

Photographs by Meredith M Howard

Pictured here: Phil Oh @mrstreetpeeper

Photographs by Meredith M Howard

Pictured here: Phil Oh @mrstreetpeeper

Photograph by Tony Maake @tonyshouz. See interview on page 340.

Photograph by Tony Maake @tonyshouz. See interview on page 340.

Picolo Diop appeared on the cover of THE STREETS – 2017 Collection. At the time of its printing, we didn't know who he was. I have since tracked him down, interviewed him via email, and then had the opportunity to meet him in person at Pitti Uomo in Florence. He is much more than a well-dressed dandy. He is a business owner, a designer, and a tailor. I asked him here about his life and work.

– Meredith M Howard

– Meredith M Howard

I was born in Dakar, Senegal. I moved from Senegal to Europe when I was 14 years old. I continued my studies in Spain and Italy. After that, I started work. Now, I live in Florence, Italy.

My business is called P&T [Picolo & Tiziano]. I am Picolo, and Tiziano is the artist Fiorentino. I used that name because I like to mix art and fashion. I started P&T with my brother Nas six years ago. I started P&T Marketing and Art with Cheikhou Keita, the director of art and my personal photographer. I do this business with passion and love. I do everything with heart.

How did you learn to make suits by hand? Are there many other tailors still making suits by hand, and do you think this craft will continue for long?

I learned how to make suits by hand from one of the big tailors in Italy. The suits are made-to-measure and also hand-sewn. The craft is going to continue for a long time.

P&T sells shirts that combine bright African patterns with classic style. Who designs these shirts and where does their inspiration come from?

I am the creator of P&T, and I am the designer, too. The inspiration comes from Western African culture and Italian taste. They are created for men’s elegance. All handmade.

What is your favorite part of your business?

My favorite part of my business is when I put together the combination of the colours and when I walk down the street and see people wearing it.

What do you dream of doing in the future?

I dream of making P&T very big and having shops in all of the big cities around the world.

One of my greatest pleasures is to grab a camera and go “run the streets,” as we used to say in my teens. Idle time chasing designs and making art with the camera, wherever I find it, is as natural to me as breathing. And sometimes I will go to insane lengths to pursue a scene or image that captivates me. I have been chased off of property; lost my car keys down a drain, while hanging from a tree; and ruined shoes and clothing climbing around many construction sites. And when I find an image or design that calls to me, I will take hundreds of shots, until I have exhausted all the pleasure I can. But I am glad to pay the price, because I consider it my creative therapy and the antidote for hassle in my life. These images are the result of pursuing my passion of getting lost in the world of the lens.

You’ve heard it from others before: "My mother gave me a Brownie when I was five." But the difference is that she also engaged with we in the search for the most artistic way to tell the story. She was a wannabe artist, and we had many fun excursions “chasing” good photos. Those first experiences carried through all of my professional and creative life because it taught me there may be technical guidelines one follows to get good photos, but artistically you have the opportunity to create by any means you want. I speak to the emotions.

You said that you will go to "insane lengths" to pursue an image. Can you tell us your favorite story about one of those situations?

When I was photo editor for Louisville Magazine one of my responsibilities was to capture the flavor and progress of Louisville. I also specialized in the arts. One day I went out to shoot the "topping out" of construction of Citizens Plaza, the (then) tallest building in Kentucky. As you probably know, photographers hate to go to photo ops because the client always wants the photo of the dignitaries and the usual ribbon cutting, speeches, etc. I was determined to do something different.

It was raining that day and unbeknownst to my editor, I talked my way inside the building, took an elevator to the top floor and convinced a construction foreman to let me go up to the driver’s cabin on the crane. In order to get high enough to see the tree being moved to the corner of that building, I had to climb hand-over-hand up the main trunk of the crane with my gear in the rain and wind. Believe me, it gave a new meaning to the phrase "blowin’ in the wind." I really wasn’t scared until I got back down to the ground and realized how high it was.

You have done a lot in your life – majored in art, studied theology, written poetry, created murals, paintings, and pottery, worked as a professional photographer and as a staff photographer for various organizations, taught photography classes, and more. Do you usually focus on one interest at a time and then move on, or do you work on different types of projects at once? How do you feel about focus vs. diversification in one’s career?

In high school I was voted "The Most Versatile." So, I am fortunate to be able do many things at once, and I am energized by the pursuit of various forms of art. I find that my photography informs my collage work, and my fused-glass experiences "ignite" my curiosity about encaustic work, etc. I guess I was meant to be diverse in my interests. I have taken over 20,000 photographs in the last 10 years, with over 4,000 completed works. I have six pieces of photo encaustic and fused glass at APG, each featuring photographs. You could say I focus on diversification.

Your images in this series include detail shots that turn the image into an abstraction. And some look cross-processed or infrared. Did you take these photos with abstraction in mind, or did you see it during the editing process?

When I gave a talk to the Art Partners of the High Museum, I explained it this way: "Finding the artistic view of a subject in the camera is, for me, like having an orgasm . . . I’m attracted, intrigued, captivated, and swept up in the imaginings of what will happen when I get to do the post-processing. I get further exhilaration from using current tools to produce images that appeal to me and others who live in the current world. I see possibilities from the beginning, but nothing compares to experiencing the discoveries that happen as I explore them in post."

You preside over the Design Salon at the Atlanta Photography Group. What have you learned from other photographers there?

That there is, in each of us, undiscovered talents and skills that just need to be coaxed out and given freedom. It’s been very rewarding to see that happening in the group and to know that I played a small part in its birth. The energy that I get from this interaction has inspired me to grow as well. Plus, we have a lot of fun.

Your question is quite on point for me. I’ve been toying with the idea of a retrospective show featuring my photography, fused glass/photography, photo encaustic, photo collage, and other work, but the thought of managing that is daunting. I’ve got the work. I’m just not sure if I have the energy to make it happen.

Find H Gay Allen on her website at www.hgayallen.com

My earliest memory of being drawn to photography was playing around with my mother’s Polaroid camera as a child. I remember having this immense joy of being able to capture anything that was going on in front of me and in less than a minute, there it was – a copy for you to hold in your hands and show others.

My mother soon hid the camera from me as I was burning a hole through her pocketbook with flashbulb and film replacements. When I was 17, I bought my first camera, a Ricoh L-20 pointand-shoot for 35mm film. I would take it with me everywhere and spend almost my entire work paycheck just buying and developing film. I would continue to use that camera for the next 15 years until 2004, when I purchased my first digital camera.

I started making videos when I was in high school. We had a television station in our school that allowed us access to equipment we could check out. I would always get the VHS camcorder and make these videos that were very often silly documentaries with me as the narrator and cameraman. There was never a script with any video I would make. I would just give my friends, family, neighbors and anybody else who would help me a starting and ending point of an idea and have them follow my lead as I recorded them. I would edit the footage with two VCRs at home. Since 2009, everything I shoot (video & photos) is with an iPhone.

Your films are pretty quirky. What is your motivation and inspiration for them? And how do people respond to them?

"Quirky" is definitely a reasonable word for some of my video work. I began making videos for YouTube in 2009. Then, my inspiration was making parodies of the types of things I was watching on YouTube around that time like wedding proposals, unboxing videos, fake movie trailers, tech shows, lip-sync videos, all of which are now ubiquitous on YouTube, but at the time were a very small percentage.

Eventually, as the iPhone became a better video camera and the App Store had thousands of apps for creatives to enhance their workflow, I found myself tapping into areas of creation with visuals never before possible for me. I started working more in the abstract and experimenting with filters, effects, distortion, etc. while at the same time trying to create something that was honest and coming from a place of truth. I made several videos where the dominant theme was anxiety and depression but also tried to inject my sense of humor into it to make it a little more palatable.

I’ve had a couple of videos that have won some awards, and I’ve had a video reach a million views in a month. I consider that pretty damn good. People’s reaction to my video work has always been either no comment at all or "that’s brilliant." I know my work is not really commercial, but I also know that there are people like me who enjoy this kind of work. The hardest part has been trying to find them. In the beginning I was fixated on getting hits and subscribers to justify my existence as a creative. Now, I am at a place where that doesn’t matter. Just trust in what you do, be honest, have fun, and my audience will find me.

Do you usually go out looking for something to photograph, or do you just take a picture when something catches your eye? Do you know how you are going to edit it when you take the shot?

There are days when I will specifically go out looking for something to shoot. But I believe most of the time it’s what catches my eye at any given time during the day, and since my iPhone is always with me, it’s easy to do this. A number of times I’m taking still-life photos of common things like buildings, flowers, trees, lighting fixtures, pictures of my friends or strangers. Occasionally, I will take some of those images and import/export them through several of the apps I have, applying many different effects until it looks completely different from the original image. After it rains, I like to experiment with the many ways I can get shots from reflections in the puddles created. I like to take pictures of skyscraper buildings in Chicago and mirror them along with several other tweaks until it looks like something so futuristic or not a building at all. There really is no end to what you can create from any photograph. There’s no such thing as an unusable photo, as you can always turn it into something visually engaging and abstract.

“I’ve been waiting a long time for the ability to create at the speed of thought.”

The friend who connected us said that your son has struggled with PANDAS for years. Can you tell us a little about that experience?

My 13-year-old son has an autoimmune disorder called PANDAS, which causes debilitating psychiatric symptoms. At the risk of sounding dramatic, I am not sure how we survived the past five years. At times, his symptoms were so severe he could not move from one room of the house to another. Every waking moment for him was controlled by intrusive thoughts and compulsions. One of his compulsions was to change his clothes and open the front door. One night last winter, this went on from 7:30 pm until 7:30 am. My wife walked with him around the block and back into the house for 12 hours, as he repeated this compulsion. To watch your child suffer like that is indescribable. We were physically and emotionally drained for years. We also felt that the healthcare system had failed him. We were sent away from the ER on many occasions, being told that he did not meet the criteria for hospitalization.

And did your son receive treatment that helped him?

Luke was on many antibiotics and has had a number of both high dose and low dose IVIGs. The low dose is the one that seemed to work the best and has brought us to where we are today. Much, much better. Miracles happen.

I was able to make a connection with my son."

How has all of this (your son’s illness and journey) affected you as a parent and as an artist?

As a parent, it has affected me greatly. I was not prepared for this fight, and it scared the hell out of me. In my life, up until the point my son was exhibiting the worst of his illness, I had never truly experienced such pain, fear and hopelessness. If it hadn’t been for my wife who discovered this treatment and never gave up on him, I may never have found the strength to keep going, and that makes me feel ashamed. As an artist, it both stalled my work and also helped make it more real when I dealt with themes of sadness and depression. But through my work, I was able to make a connection with my son, as he is a big fan and contributor to my NOT IN FOCUS web series. And through some of the worst times he was going through, he always seemed to perk up and get excited when he knew I was putting a new episode together, which he still helps me with to this day.

I’m sure there were times when other people – friends, family, strangers – didn’t know how to respond to your son or know how to support you. How would you have wanted people to respond to you and support you?

The symptoms of this illness are so bizarre, they are hard to comprehend unless you live through them. What most people don’t understand is how few doctors in this country treat this illness. When people would see the severity of our son’s symptoms, it sometimes felt that they were wondering why we weren’t doing anything. The thing is, we were doing everything we could. That being said, we received much support.

For my son to continue to get better and better, which he has by leaps and bounds compared to where we were just a year ago. A night and day difference. Everything else is secondary to that.

Find Matthew’s photos and videos at www.hipbattersea.com and follow him at Instagram @matthewstromer

Matthew W Warren

Matthew W Warren

Model: Ako

Model: Ako

Matthew: This was one of probably 30 different places that I lived within Clayton County. I lived here with my grandparents, and we were super young. We’re going to go to the spot where we used to play.

Ako: So, what age did you live here?

Matthew: This was from like four to six. This is one of the first places I actually remember living. Yeah, welcome to my home!

Matthew W Warren put together a photoshoot with Ako and took us back to his childhood home to show us how he uses his roots to make his art.

Matthew (continued): I think Ako can speak for us, too, when we say, "Welcome to where the arts are from." Seriously, they pushed all of us to one spot and were like, "We don’t want nothing to do with you." And out of that, we were like – "OK, we’re just going to tell the story about it then."

I bring you here because I want to show you a piece of my life, but the majority of the spots where I’ll shoot Ako in or Ziggy or other models are places I’ve lived . . . We did another shoot right down the street from my dad’s house because what greater thing than to use where you’re from?

Man, we understand each other when we work together. I told Ako on the way over here, "You know we’re going make it work whenever we get together. It’s not even stressful. It’s fluid. It’s like drinking water."

Meredith: Do you tell Ako what to wear or does he come up with his own outfits?

Matthew: Ako’s style is one of the main reasons I hit him up. I told him . . . what did I say?

Ako: You referenced an idea, and then I just kind of put it together.

Matthew: Yeah, I trust him . . . the color scheme down to a turtleneck. See, I was thinking like a collared shirt or something like that, but I like this. The only thing is I said, "Man, it’d be dope if you would have had some athletic socks and sandals." Or some thermal socks, but he didn’t have any athletic flip flops. But in the future we’re going to do that. We’ll probably focus in just on the flip flops.

Before I began shooting models, I just grabbed architecture around Clayton County . . . I love harsh light – done right, obviously . . . The harsh light reveals colors. Everything’s just totally different when shot in harsh light. Fortunately, with what we do, we’re able to make that work.

"Welcome

[Matthew used a disposable camera for half of the shoot, so we talked about experimenting.]

Matthew: People are so scared to get out of their set editing style. I don’t know where that came about. I don’t know why. Instagram kind of made you do that. You want to look at the squares. But it limits you to color palette. It limits you to experiment with other styles.

Ako: So, you’re saying an artist might have the same style of editing throughout every picture, just to keep it cohesive?

Matthew: Like if you used the same beat on every track. That’s the equivalent of it.

Meredith: I feel like it sometimes makes people more successful if they stay in the same track. But then it gets a little boring for the artist.

Ako: It should be seasonal. Like if you have a project coming out and you need everything to look cohesive for a project, you can stay within one of set of editing. But then if you have another project, you need to switch it up because a new project means a new look.

Matthew: I play drums, too. I like DW kits. I like the wood they use. But I’m not opposed to getting an electric Roland on the next song . . . For the people from 2015 until now, when they go and shoot it has to be a white background, some little green bush in the middle, and maybe a girl with a similar pose. Man, just try to shoot with some 1970s film or something like that. That’s what we do as creatives – we have to constantly challenge our imagination.

Meredith: How did you get into photography originally?

Matthew: When I was in 10th grade, which was 2004, I went up to Pittsburgh with my family. That’s where my mom’s side lives. And at the time photography wasn’t a huge thing. But I thought, "I just want to show my friends what they don’t get to see because I get to go up there and just bring it back to them." So I took a disposable camera.

That was the first time I picked up a camera. It was without the intent of saying, "I’m an actual photographer." I just wanted to show them memories. I just wanted to show them my greatgrandmother. My great-grandmother’s from Mexico, and her style of living – you would walk up in there, and you would smell onions and tomatoes. I wanted to get some of this and show it to some people. Because it looked different than Clayton County. Just the style of houses. It looked more urban than what urban is considered down here.

But actually pursued – like "I want to go do this for a living" – was five years ago. And I had no idea how to pursue it or how to go about it . . . My first gig was a Vacation Bible School at this church called Victoria Christo where my wife went to church, and they invited me because they were like, "Man, you take really good pictures." I thought, "I’m going to give these people documentary-style Vacation Bible School." And I still have those photos. I like looking back on those because it was carefree. Around 2012-2013 while photographing subjects at events I thought, "I want to do this."

“That’s what we do as creatives –we have to constantly challenge our imagination.”

Meredith: Did you have a job back then and transition into photography?

Matthew: I didn’t graduate high school, so I went straight into landscaping, construction, grocery stores. Went back and tried to graduate. Failed again. I remember telling Clayton County school, "Y’all are wasting your time. I’m going to be an artist when I get older." It’s not that I wanted to be famous. I don’t want to be an icon . . . At the time, my mindset was playing drums and keys. I’m a musician. I’ve been playing drums since I was like six . . . I was in a band for two years full-time, so I would play at some of the clubs in Atlanta. We’d get paid off those gigs. We had a distribution deal. I produced and wrote a lot of the material . . . At that time, I was just like, "This is what I’m going to do. I’m either going to be a musician or write music for people." So, I was in a band, but off and on, construction. Sometimes without a job. I worked at a lot of places. Warehouses. When you’re taught that there’s nothing after education. Your mind starts going – "This is it."

Meredith: Your first photography job was for a church. After that, how did you keep it going?

Matthew: I don’t even remember what was after that. Every time I would say, "I’m going to pursue this as a career," people would ask, "You sure you don’t want something on the side?" And after time goes by, you just start getting bombarded with discouragement. You’re like, "Whatever, man. You just a failure in life." And the only person who said, "You should pursue this," was my wife. We got married in 2014, and she said, "I want you to pursue your business full-time." So we took those steps. It was really rough. I was shooting local rappers’ album covers. I worked at John Casablancas modeling agency shooting models’ head shots. I used to shoot a lot of 5ks and marathons. That was exhausting because you had to run with them. I’d get a calendar, and out of the 30 different 5ks that you have this month, I’m going to get four of them. I’m going to have a job every single weekend.

My family always tells me, "You didn’t get a diploma, but you did get a social education." Those high school hallways. The bullying from just one class to another. I was like, "Am I going to get in a fight?" I got to be ready to get roasted on. So, it built all that up to where you go out in the real world and you’re like , "Man, I’ve been through some hell." Social education – I passed with flying colors. That led me into not being scared of rejection from a company. The worst they can do is say "no."

Meredith: Did you consciously develop a retro style? Like Ako’s clothing with the parking lot and the way you put it together and edit it?

Matthew: I believe that anything we do – the arts, whether we’re accountants, or work at a grocery store – our work ethic is a reflection of our upbringing, our experience, things that were said. That’s why some people are lazy, some people aren’t. But it’s all a result of our upbringing.

I love hip hop. Clayton County has an urban vibe. Going back to my actual neighborhood – it should be a reflection of that. It wouldn’t make sense if my photos were bright and airy. I’m not degrading that style at all, but I don’t see things like that . . . There are certain things for certain people. Mine is a result down to the colors. I like warmer photos.

“There’s just some 70s funk going on. And you can hear it without it being played.”

Matthew (continued): Even with the south side of Atlanta – I’m talking about South Fulton, College Park, East Point, Forest Park – we have this retro style. When I’m driving down Tara Boulevard or going through Main Street of East Point or going down Cleveland Avenue, I feel like an electric guitar is just playing some blues at the moment. There’s just some 70s funk going on. And you can hear it without it being played.

One of the things that I put on my website that I just came to find out is the most beautiful part about us is that we have no say-so in where we were born, what language we will speak, what family we’ll be a part of. And the beauty of that design is that you can not change that. You can try to run from it. You can over-embrace it. But I think the balance of it is remembering it, applying it, but not overdoing it. My style has developed because of my surroundings, my upbringing, down to my father, to my mother, to my friend Damen that lived right next door to me.

Julieann: When Meredith showed me your photos and mentioned that you were from the south side, I thought, "I’m from there!" Your photos definitely portray what the south side has, and it’s amazing to see those photos in such an artful way. I was pretty impressed.

Matthew: Is it a proper translation?

Meredith: She said to me, "How does he make this area look so good?"

Julieann: Growing up here, it’s like you mentioned – gangs, crime. So, I’m impressed by your work.

“I’m not really drawn to the in-between of this life . . . I love extremes.”

Matthew: Even like that – "How do you make this area look so good" – it’s been taught to us that it is so bad. Part of me is like – not that I want people to be poor – but I love the fact that we have that. Like I said, if I had been in Buckhead and went to school up there, it’s not that I would have been basic, it’s just I would have had a different life. I wouldn’t have been able to tell the story like this . . . I’m not really drawn to the in-between of this life . . . I love extremes.

Meredith: I like extremes too. I live in the suburbs, and when people say, "Shoot where you’re from," I keep trying to do that. But then I think, "This is boring."

Matthew: That’s what I thought at first. That’s what I thought about my [photographs of my grandparent’s house]. It was like a typical family vacation, but people were like, "No, I love that." Because even though I thought it was this corny story, people were like, “I didn’t get to live that.” So I was like, "I’m just going to dig into the depths of my childhood –whether or not it will be what I think people are going to like." Maybe that’s hope for somebody. Jon Foreman taught me that – lead singer of Switchfoot. He’s probably one of my favorite poets of all time.

“The most beautiful part about us is that we have no say-so in where we were born, what language we will speak, what family we’ll be a part of. The beauty of that design is that you can not change that. You can try to run from it. You can over-embrace it.

But I think the balance of it is remembering it, applying it, but not overdoing it.”

Julieann: In some of your photos, you incorporate fashion with the location that you’re in. Why do you include fashion?

Matthew: Honestly, I’m not a very experimental person when it comes to fashion because I’m like, "That won’t look right on me." I love fashion. I believe it’s a whole other outlet of the arts. But the real reason is, in high school, my dad shopped at thrift stores when it was just the way to afford clothes for your kids. I’m not saying we were poor growing up, but he was a single dad. He took us there, we got clothes, and we went to school. In Clayton County schools, if you do that, you get made fun of like crazy. That’s the part of social education that’s so vital. Many parents nowadays would be like, "That’s torture for a kid. I would never put my kid through that." I look back on it – it sucked, but I embrace it. Down to where I would get so insecure about what I was wearing that just looking at someone else’s wardrobe that week would just satisfy my eye. To kind of put it on me at the time. Girbauds – I want those. I want to be able to have the velcro strap at the bottom and walk around with the Chuck Taylors on. But I can’t. Free-stylin’ was a big thing in Clayton County schools. You’d be in the lunch room and somebody would come with a beat and you’d start free-stylin’. It was who could make fun of who the best. And there was this guy one day, I saw him look down at my shoes and he said [rapping], "You gonna lose. Matt Warren’s wearing church shoes to school." And the whole crowd busted out laughing. You can’t show your emotions. You have to prove how hard you are. At the time, I was like, "F*** this. I hate this. I hate coming to school."

I stood by the lost-and-found, and at the time, Adidas Superstars were back in style and K-Swiss with the five stripes. And somebody would leave them in gym, and I snatched those things up. At our school, you marked them at the bottom, so somebody knew if you stole them. So, I took a pair of all black Adidas Superstars, and I’m like, "I’m fly. I got this. I’m not going to get made fun of anymore."

That was the desperation. That was the urge to have some kind of minimal fashion just to dress it up enough so you don’t get made fun of. The urgency of that is what started it. Fashion’s everything in urban schools. If you don’t have on a certain article of clothing, you are going to get made fun of. And some people go, "You’re weak for giving into peer pressure." I’m like, "It shaped the way I see myself dress." I would imagine outfits. When you can’t have something, what you produce from that is everything.

Julieann: I’m impressed that you remember what that guy rapped in the lunch room.

Matthew: Those things are the hardest. But in this case, inspired. Thank you, Bernard White! Boy, he got me that day.

Meredith: So, what do you dream of doing in the future?

Matthew: There’s a certain people group that actually have time to think about future plans . . . I’m not trying to create a story of struggle, but we were not taught, "OK, you need to plan for the future. What’s your five year plan?" That vocabulary didn’t exist . . . I want to be able to plan for the future, but fortunately – not unfortunately – it’s always been like, "What do we have going on tomorrow?"

My hopes are – as far as photography goes – I want to put on a national exhibit. To put on the south side of Atlanta as if it were a New York, as if it were a Los Angeles. My boy Tamarcus Brown (@hazelandco), we just got off the phone with each other last night, and he was like, "Homie, nobody’s doing what you’re doing, man." And in my humblest approach to that, I’m like, "Thank you. I hope nobody lived the exact same story as me." We were talking about that and I said, "Why can’t it be as known? Why can’t people think of the south side of Atlanta like that – because when you think of the hip hop industry since 2003, Atlanta has just exploded, and none of those rappers, none of those artists are from the north side of Atlanta."

“They just shoved us all in a corner, but we got the best stories.”

Matthew (continued): There are some from the west side. There are some from the east side. But the majority and the most iconic – Outkast – are from the south side. Young Thug is from Jonesboro south. They fail to tell you that. The only mention of this side of town is filth. Ever since the mid-90s when the projects were torn down, they just shoved everybody – poverty, filth, gangs and crime – to this part. I made a joke back there that they just shoved us all in a corner, but we got the best stories. I love that. I don’t want to be no cookie-cutter. I’m glad I’m not a product of "white flight" in the mid-90s. I’m glad my dad stayed, so that I could see a certain lifestyle and translate that for you. I want to share that.

Meredith: Well, I think you’re doing an awesome job at it. I think that is one of the best ways to do it – through the arts. Showing that everybody’s beautiful in an artful way.

Matthew: That’s the hopes. You’re the first person that I told on a recording – a national exhibit. I want to do a photography tour. I don’t know what steps need to be taken, but that would be dope.

Follow Matthew W Warren on Instagram @matthewwwarren and on www.matthewwwarren.com

Follow Ako @akoslice

Meredith: How did you originally get into photography?

Mercedes: My older sister was starting to get into photography, and I always just copied everything that she did. I got a camera when I was in high school and started taking close-up pictures of plants and all that lame stuff you do when you first get a camera. I really wanted to study photography in school – go to the art school – and my parents didn’t want me to, which is fine. But I found a loophole in photojournalism. I’m really glad I did, because it fits me so much better than I think art school photography would have. I have a lot of respect for more artistic photographers, but I really love the storytelling aspect of photojournalism. I went to Grady College of Journalism [University of Georgia], and then got into the photojournalism program. That’s when I really fell in love with it and really learned how to use my camera and how to tell stories with it.

Meredith: What did you think you were going to do after school?

Mercedes: I really thought that I was going to be a photojournalist. You kind of get intoxicated with it. I think journalism can sometimes be an act of martyrdom. I thought, "I’m going to start at all these really small papers and work my way up to New York Times and be a war photographer." It just gets very intense, and I was really into it.

But when I was the chief photographer for the school newspaper, I had to shoot a tragedy. One of the RAs in a dorm died, and they were like, "Go shoot it!" I’m very soft, and I never really realized it until that moment. I felt like a vulture. And I know capturing those moments is important, but it was at that moment that I realized, "I don’t think I can do this." The picture was awful. It was a terrible experience. It was toward the end of my junior year when that happened, and I only had one semester as a senior because I graduated early. So, I was like, "I don’t know what I want to do now because it’s not this."

I got an internship as a fashion photographer for umano, a small clothing brand in Athens, and I loved it. It was a completely different form of storytelling. It kind of got me out of that mindset and into thinking, "Ok, what else can I do with photography?"

Meredith: What did you do for them specifically?

Mercedes: I started full-time after I graduated. It was really small. It was a startup. There were only five of us full-time, so we were all wearing a bunch of different hats. I was social media manager, blog manager, and photography manager. I did everything from planning shoots and getting models to editing photos, writing copy, and planning all social media layouts.

Meredith: That’s awesome experience.

Mercedes: Yeah, it was really great. Unfortunately, the company closed in February.

Meredith: That’s a hard industry.

Mercedes: It is. And especially in Athens. It’s just not really a fashion hub at all . . . I’ve been trying to get more into photography this year just because I miss it. I miss being able to be creative every single day. I work at a communications agency right now, which is great. I’m learning a lot. It’s like a 180 from what I was doing before. You learn so many different things working for huge corporate clients than you do for a startup and vice versa. So I’m glad that I’ve had both of them . . . It has been cool because with umano, it was kind of forced creativity every day, and I would leave my camera at the office on the weekends just because I didn’t want to touch it anymore. And now I’m kind of forced to be creative outside of work, which has been fun. I’ve been shooting with friends again and trying to get back into it. I think travel photography can be a lot easier because you’re constantly inspired. There are different things everywhere, so of course you want to take pictures of all these things that you haven’t seen before. Whereas getting inspired in your own city with your own friends who you see every day can be a little more difficult. I’ve been getting excited about that challenge again.

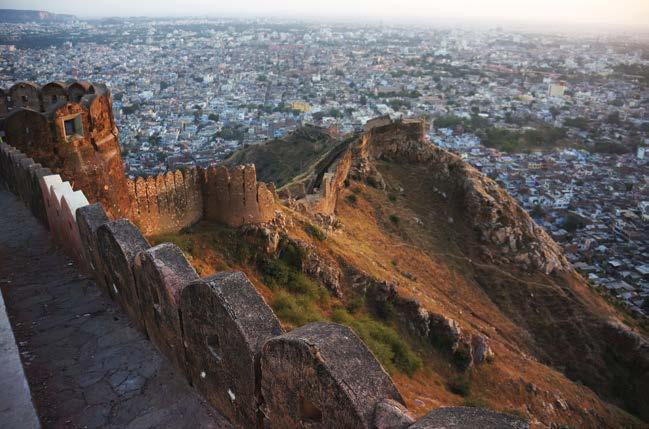

Meredith: You took a trip to India in March. Why did you decide to go there?

Mercedes: My boyfriend and I love to travel. We’ve both been a lot of places. He’s been more places than I have. I’ve been to Europe a lot, but I had never been to any place like India. I don’t know why we chose India as our first trip together, but we had just never been that far and we really wanted to go experience it and experience the food and the people. I think we kind of wanted an intense trip. My boyfriend founded umano. So after umano closed, we both needed something intense to kind of overwhelm our senses. So we chose India, and it was just that – an overwhelming of the senses.

Meredith: How would you describe it?

Mercedes: A lot. A lot of tastes. A lot of sounds. A lot of religions intermixing. And extremes on every end. The most extreme environment you’ve ever been in of loudness and craziness and people. And then you go into some of the temples and it’s the most extreme peace you’ve ever felt. It’s just like a constant roller coaster.

Meredith: Wow. How long were you there?

Mercedes: We were there about 11 days. I wish we had stayed longer because it’s such a shock when you first get there. It takes a little while to get used to how loud it is. And then by the time you’re settled, you love it, and then it’s time to go home.

Meredith: I saw the picture of the men peeling the potatoes, and Jyotik (page 64) showed me a similar picture of people peeling potatoes. So what’s up with all the potatoes?

Mercedes: That was at the Sikh house of worship, Bangla Sahib. It was beautiful. They prepare food every day for anybody who wants to come eat. So every day there are people preparing tons and tons of food. And you can worship with them, but you don’t have to pay. Sikhism is a very peaceful and inviting religion.

Meredith: In one of your photographs, there is a man praying on the steps. Was that a common thing to see?

Mercedes: That was also at the Sikh temple. It’s a huge temple with all these different rooms, and then outside there’s people everywhere praying. It’s pretty common to see people praying. And there’s cows everywhere. Most of the traffic jams are because of cows. Traffic there is like nothing I’ve seen ever. We got around in tuk-tuks most of the time – the little open-air cars – and it’s never quiet. Everybody is constantly honking. Nobody pays attention to the lanes really, so everybody’s just swerving. There’s tuk-tuks, there’s cars, there’s whole families on bicycles carrying all of their furniture or all of their food for the week, and then cows just in the road.

Meredith: Were there any times when you felt really uncomfortable?

Mercedes: Yes . . . It was amazing, and I’m so grateful I went. It’s such a celebration of tastes and sounds and culture, but there are so many sad parts that make you check your privilege . . . We stayed in Airbnbs the whole time, which I’m really glad we did to kind of get all angles of it and get to know the people who were hosting us . . . I think it’s really eye-opening because you really do see the wealth disparity. Here it’s segmented. You have your fancy downtown area, and then you have your impoverished areas. But there you’ve got these gorgeous high rises and people walking out in suits, and then literally across the street is the saddest slum that you’ve ever seen. So having all of that right next to each other was really hard to see. And that was everywhere. Agra is the city where the Taj Mahal is, and that’s really all that’s there. The surrounding area is very poor. There’s this huge, gorgeous hotel next to the Taj Mahal, and I think a lot of people will stay at that gorgeous hotel, walk over to the Taj Mahal, and then leave, and that’s all they see. We stayed at an Airbnb that’s more in the village, and I really struggled that day. That day in Agra, there was this huge festival, so the streets were insanely crowded. There were cows everywhere blocking the roads. People everywhere. So our driver was trying to find our Airbnb and pulled into this place that definitely wasn’t it. There were people everywhere surrounding the car, and he started to back out, and there was a baby behind our wheel. The mom picked it up. We didn’t hit it, but I started crying. It was very overwhelming. It was more overwhelming because it didn’t seem like it was that big of a deal. She just picked the baby up, wiped it off, and walked away like it wasn’t a huge deal. And I just lost it. I’m very much an introvert anyway, so that kind of environment is a lot for me and that situation was crazy.

I needed some time, so I just sat in our Airbnb for a little bit. Some of the pictures in this series were actually taken by my boyfriend that night. I like leaving them as part of the story, because while I was having my moment recouping inside, he was able to go out in that festival and capture some really cool images.

Meredith: How do you think the trip affected your view on life?

Mercedes: I think I learned a lot from how accepting they are. There’s a lot of intermixing of religions. There’s Sikhism and the Bahá'í faith and Hinduism, and they’re all very different but they all blend together so peacefully. You’d see a tuk-tuk driver who was a Sikh who had no problem driving a Hindu person. I think there was so much acceptance for other people’s religions that we don’t even really have here.

I’m definitely a lot more thankful for how easy everything is here in comparison. I wouldn’t say that India is this sad country that I want to pity because it’s not. It’s gorgeous. And they have a lot that we don’t have. But the parts that are bad are really bad, and we don’t have anything like that.

Meredith: Earlier, I mentioned Jyotik, the Indian photographer. I was wondering if you would have any questions for him?

Mercedes: Well, like I was saying about having to find inspiration in your own city. It was easy for me to find inspiration in India because it’s so different, but for him, how does he a fresh perspective? And are all of the things he sees still super interesting and unique to him or are they just day-to-day images?

Meredith: That’s a good question. I always struggle to document my own home. I grew up here in Atlanta. Photography has given me a greater appreciation for Atlanta – trying to notice things.

Mercedes: I bet meeting up with a lot of different photographers and being exposed to their world and how they see Atlanta [helps]. I moved to Atlanta in June. I grew up in Georgia and have been to Atlanta tons, but I’ve never lived here until now. And I know there are so many different sides to Atlanta that I’m not exposed to. The first time I met Matthew (page 36), he was wearing a shirt that said "South Side", and I assumed Chicago. And I said, "Oh, are you from Chicago?" And he was like, "No way, I’m from South Atlanta!"

Meredith: That’s so funny. He’s proud of where he’s from . . . In thinking about your career and life, what do you dream about doing in the future?

Mercedes: I really have a heart for startups – especially ones with a social mission. At umano, with every product you purchased from us, we gave a backpack full of art supplies to a kid. And kids drew all of the artwork on our shirts. So, every time we sold a shirt with their artwork, we got to give a backpack to another kid. It was a virtuous cycle. We got to go into schools to hang out with kids, and I love squishy stuff like that. So, my ultimate goal is to get back to that.

I enjoy working in an agency and working with a lot of different brands to kind of get to know how everything works. Umano was my first job, so everything that I learn now, I think, "Oh, I could have done so much better for the company with the stuff I know now." So, right now, I’m just thinking about equipping my toolbox, so that in the future, I can go into a brand I care about and make a difference.

Follow Mercedes on her website at mercedesbleth.com and on Instagram @mercedesbleth

I was born and brought up and currently stay in Ahmedabad, Gujarat in the western part of India.

I like the dynamism of life and people in India. India has an amalgam of culture, religion, technology, and architecture, and every thing survives in its own manner. The streets of my country are my favourite places. When I walk around, I see people in their own livelihood. They carry their own attire. An attire of emotions and personality to come up each day. India is all about diversity.

I would like to see changes in preservation of historical monuments, a justified use of technology and more work to be done on developing humanity and respect for art.

I have never been to India, but several of my friends have visited. They loved it, but when they returned home, they felt depressed for a while because of the extreme poverty they saw. However, many of your photographs convey a sense of joy. What is the prevailing feeling and outlook of the people around you?

People have all kinds of emotions here. Keeping aside my patriotic feeling for my country, I neutrally see about what my images could reflect. Do they reflect a sense of happiness, satisfaction, a sense of belongingness as a human being? I always feel that a photograph makes one connected to oneself. If we search for poverty, our camera will capture it; if we seek joy, our lens will make those images. It is how we see things happening – the perspective behind the images in a poor man’s home or his gesture on street or elsewhere is what matters to me.

“If

I used to make drawings and paintings. But they seemed so static and so imaginary. So I initially bought a compact digicam around 2010 or so and started making pictures in my room and surroundings. This exploration with my camera and experiencing life in each moment made me more inclined towards photography. I am passionate about it. My mind gets new forms of inputs and new experiences each time I move with my camera along the streets.

I am a psychiatrist by profession. I work with clients having some or the other psychological issues and with people under stress. I try to explore their mind and find out the best possible solution. I love my work, as it fulfills my basic wish of exploration. I also love talking with people and know more about how situations impact a human mind. I like to know how the mind develops its own processes to help a person.

When I interviewed Mercedes (page 56), she said it was easy to find inspiration in India because it is so different from her own life. However, it is often difficult to find inspiration in her own city. Are the people and scenes you photograph interesting to you? Or are they just normal everyday life that you think someone else might find interesting?

There are many people around here. Not everyone is interesting. As a photographer I need to capture emotions to which people can relate. I cannot photograph everything that comes in front of my eye. I try to find positive gestures in chaos or a crowd. Very small moments unseen between many things. I do not know about whether someone might be interested or not. It is an instinct that keeps me moving around Ahmedabad to discover the greatest gift to humans, i.e., life.

Cows are an integral part of the Indian community and culture. Cows are a part of society. We respect and accept their existence. Yes, they are stray animals, yet respected in terms of food, religion, and life. Also, a few people in the city still own so many cattle at home which are often moving around their residence. A few of my images reflect the "urban cow" – existence of the cow in city streets.

Why are there so many cows everywhere?

Mercedes also said that many religions blend together so peacefully in India. She feels like there is more acceptance of other religions in India than there is here in America. Do you feel like people are really accepting of other religions, or is there any unspoken discrimination? And how would a Hindu family feel if their child decided to convert to Islam or Christianity or decided not to practice any religion?

This is a very interesting area. I feel religion and culture was there in India ages long. With science, technology, and development in terms of business and education, there is a lot of amalgam. People are now focused on work and development. Acceptance is a virtue. Indians are so very democratic to enjoy each festival of each religion. Atheist ideology also exists here. "We are harmony-loving emotional people. So we don’t mind anyone’s ideology." This is what an Indian thinks in India.

In the future, I would like to work more on street photography or documentary. Maybe in my city at first and then exploring other cultures as well. The world is so big enough and full of life. When you search for life, life comes back to you with a new gift. I consider this gift to be creativity. With this creativity, I make images and make the connection stronger.

Meredith: I want to start at the beginning with your childhood. You were born in Los Angeles?

Kevin: Yes. My parents are from a little town in Guatemala called Tecun Uman. From there they migrated into the United States in 1989. They went to Los Angeles, California. I was born in 1995, and I have two older sisters.

Meredith: Did your parents tell you any stories about immigrating and how that was for them?

Kevin: Yes, their story is actually really scary. My mom and dad got married at 18. The town they were living in was super corrupt and was getting taken over by drug cartels. The town next to them was where El Chapo was actually caught. They wanted to get away from that. They wanted to have kids and start a family and not have us in such a violent environment.

So their story starts with them getting what’s called un coyote – like a coyote. They take you through a series of paths that the U.S. government doesn’t have knowledge of. They got split from the coyote and had to take their own path because the government showed up. They took a route that took them toward a river. My dad’s a really bad swimmer. He almost died that day, but luckily my mom is super good at swimming. She saved my father’s life when they were crossing into the United States. That’s one of my motivations. My dad almost passed away just to come here for us. Everyday, I think that to myself, and it motivates me to keep pushing and pushing.

"My dad almost passed away just to come here for us.

Everyday, I think that to myself, and it motivates me to keep pushing and pushing."

Kevin (continued): From there they got jobs in Los Angeles. Just random jobs because you can’t really get a career going straight from a different country. They are definitely my number one inspiration. I always hear these immigration stories about firstgeneration kids in the United States, and they’re talking about how they are so thankful. And it’s super true. You have to think about where all that inspiration really came from. And when you look into it, it’s from your parents. They worked so much for me to be here. It’s insane.

Meredith: Where in LA did you grow up?

Kevin: Hollywood. I was born in the Hollywood Hospital. My mom would always tell me, "You were destined to be a star. You were born in Hollywood." I always say, "Calm down, Mom. I don’t want to be a star." I don’t think I would ever want to be famous. It’s too much pressure. Too many people watching you.

Meredith: How did you get into photography?

Kevin: Photography all started in high school when I was actually skateboarding. I would go out with friends who were amateur skateboarders. They were just skateboarding for the fun of it, and then later on, they actually got signed onto companies. I would take photographs of them and submit it to their companies and they would send me tiny checks like $50 or $100. And I was like, "Wow! You can make a living off this." In high school, I was in a photography class and one of my teachers signed me up for photo competitions. I actually ended up winning the first competition, and they gave me a $1,000 check. I used that to buy my first camera because I was borrowing friends’ cameras.

Meredith: When did you move to Atlanta?

Kevin: Around 1998 my parents made that big move. My uncle offered my dad a job here in Atlanta constructing houses and interiors of apartments. I was three years old when I came to Atlanta.

Meredith: Did you go to Gwinnett Tech?

Kevin: I did go to Gwinnett Tech. It was not my primary choice. At first when I was in high school, I thought, "I’m not going to go to college, because I won’t have enough money." I won a scholarship while I was in high school for the Art Institute, and when I got that scholarship, I thought, "Maybe there’s a little bit of hope." But I ended up not going. I didn’t want to enroll. I just wanted to take some classes, but they wouldn’t let me use the scholarship for that.

I ended up not using it at all and taking loans out to go to Gwinnett Tech. I got a job there as an IT Studio Manager. That really helped me develop what I wanted to do – or what I thought I wanted to do. I feel like there’s always these stepping stones for every artists where you think you want to do one thing, but then you realize it’s either impossible or it’s something you just don’t want to do.

Meredith: So what did you think you wanted to do?

Kevin: I really thought I wanted to be a portrait photographer because that’s what I was doing a lot when I was there. We had these two giant studios there, and every single day I was there until midnight creating portraits and trying to create something new. That’s definitely still something I want to do, but it’s really difficult to make a living off of portraits. That was always my goal – to create artwork that I love but also something that I can give back. At the end of the day, I want to give back to the people who helped me get to where I am. It’s a really important thing that I think a lot of artists forget. I think that’s what a lot of millennial artists forget to do is to look back and to see who actually helped you. Who helped you push your work and expose you to the world of photography.

Meredith: When did you intern for Creative Loafing?

Kevin: I interned while I was at Gwinnett Tech. I was required to have a internship. I contacted Joeff Davis. He said, "Send me your portfolio and resume." I had my professors write me recommendation letters because I really wanted this. He called me and asked me questions and then said, "When can you start?" So, I took that opportunity and pushed it as much as possible to get into as many concerts, events – things that a regular photographer would be restricted to. It was great.

Meredith: Where do you think you’ve learned the most?

Kevin: I think just shooting around the city. At Gwinnett Tech, I definitely learned technical stuff, but not photography related – just organizational skills. I always love taking photos of random people, and there’s something in my imagination that I just like to make up stories about them.

Meredith: I saw that story that you posted the other day on Instagram. Was that a real story or did you make that up?

Kevin: I actually just made that up. I spent like three or four hours staring at this photograph thinking of what this guy’s story could be, and my girlfriend, Sarah, said, "Does everything have to be real? Can you create some sort of fantasy?" And that’s what really pushed me to think, "Maybe I can make

a story up." My mind is full of stories anyway and concepts. So why not put it together with words?

Meredith: I liked it. It sounded real.

Kevin: I think I’ve always wanted to write too. I’ve just never had proper English because Spanish was my first language. So, I’m always like, "Is that the right word?"

[During this interview, we were walking around downtown Atlanta, and Kevin spotted a particular building.]

Kevin: This is one of my favorite buildings that I’ve gone on top of. It wasn’t legally, but I feel as if artists don’t do that legality part.

Meredith: That doesn’t bother you – going places where it’s not legal?

Kevin: No, definitely not. I think that comes from being a skateboarder because as a skateboarder, you cannot skate any skate spot. People were like, "You can’t skate here. You could get hurt and sue us." But really skateboarders aren’t after a lawsuit. They’re just trying to get their tricks and make art with it. I’m totally against it being in the Olympics because even though you’re being active, I don’t really find it as a sport. It’s more of a lifestyle art.

Meredith: How do you find the abandoned buildings that you shoot?

Kevin: I signed up for this realty website, and it shows you what properties have been abandoned . . . But a lot of the times it’s just exploring. I guess it’s being in the right place – but also the wrong place – at the right time.

"I guess it’s being in the right place – but also the wrong place – at the right time."

Meredith: Earlier you said you don’t think portrait photography is the way to go. So, what do you want to do?

Kevin: First, when I was at Creative Loafing, I thought I wanted to be a photojournalist because I did write some articles for them. I covered the whole Women’s March. I did the MLK march. I got a really good image of some MLK relatives right up front. It was a really powerful image. So I thought I wanted to do that at first, but honestly, I don’t know what I want to end up with. Right now, I’m working with Bhargava with Chil Creative – creating and editing photos and video for clients. I recently came out with a shirt (see "3:00 PM to 3:00 AM" at fourofour.co). I feel that I’m wanted there and that I’m doing something right. Especially with fourofour. I don’t see any other companies offering free workshops to the public. So, I think maybe doing something around that. I want to do everything, but I can’t.

Meredith: Do you think you’ll stay in Atlanta?

Kevin: I think Atlanta is the hot spot right now. I think Atlanta’s definitely the home for maybe 10 years or so. Then I’ll maybe think about moving. Honestly, wherever I can get work and find new opportunities. I was in a business management class, and I got an internship with Bhargava during that class. I ended up dropping out because I was learning so much more with Bhargava.

Meredith: Is there anything that you know about photography now that you wish you had known when you first started out?

Kevin: Getting subjects comfortable was definitely a hard thing for me to develop. If you had met me a year ago, you would have thought I was super quiet.

Meredith: Really?

Kevin: I was so quiet. I didn’t talk at all. I was very to myself. And then people were saying, "Why aren’t you putting your photography out there?"

What I did was I talked to Sarah who deals with people who are very uncomfortable all the time because they have a psychological problem and are scared to talk about it. She explained to me how to get them to expose who they are. So when I’m shooting a subject, I walk around with them and get to know them. And that way, at the end of our walk, I can say, "Alright, I think I’m ready to take a photo of you." Because I really want to get to know them first before I take a picture of them. That’s definitely the thing I’m really working on in 2018 – getting to know my subjects more and not just have it be a photoshoot but have it be a connection. A new friendship almost.

When I saw Kevin’s photographs of abandoned buildings (page 76), I was inspired. I immediately envisioned a dancer in that space. I believe you should follow the trail of inspiration when it will stretch you to the next level. So, I decided to shoot a video.

First I had to find a building we could shoot in safely and hopefully legally. Kevin suggested Lindale Mill. And then I had to find some dancers. I wanted either a hip hop dancer or an animator, and the only local source I knew about was Dragon House – a hip hop incubator that has been featured on the television show "So You Think You Can Dance." Through an Instagram search, I found Cordaro (who has since left Dragon House and gone out on his own). I asked Aimee Labrecque, who teaches at my daughters' dance studio, to join us. I found some royaltyfree music on Soundcloud, devised a concept, and we all headed out to make a video. During our drive, we talked to Cordaro about his life and work.

Meredith: Where are you from originally?

Cordaro: I grew up in Detroit, Michigan. I lived there 17 years.

Meredith: What was it like? I’ve never been to Detroit.

Cordaro: And you don’t want to go either.

Meredith: Oh, really?

Cordaro: Yeah, it’s rough out there. It’s one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S.

Julieann: Why did you move to Atlanta?

Cordaro: Dance. I got a few opportunities here that kind of pushed me to keep going. In Detroit, it’s really rough out there. I couldn’t stay in that environment. And I already knew what I wanted to do as a kid.

Meredith: When did you start dancing?

Cordaro: Ten years old.

Meredith: What made you want to start?

Cordaro: Watching Michael Jackson. It actually all started from a Winterfresh commercial. There was this old guy and he was waving and I thought, "That’s cool. I want to learn how to do that." So I just emulated it. As I got older, I got serious about dancing.

Meredith: So how long did it take you to learn what you do now? Would you call it animation?

Cordaro: Yeah, animation. I’m still learning. It’s going to take a long time. But as far as where I am now, I would say about 15 years of being serious about it.

"It actually all started from a Winterfresh commercial."

Meredith: How much do you practice?

Cordaro: A lot.

Meredith: Last summer, I tried to learn how to tut. It is so hard. I mean, it looks hard, but then when I tried to do it, it’s even harder than it looks.

Cordaro: I don’t even remember how I learned how to tut. It just came to me. But I could do a tut set, and you could ask me to do the exact same thing I just did, and I wouldn’t be able to do it.

Meredith: It just flows out?

Cordaro: Yep.

Meredith: I think when you are doing what you were born to do, it kind of flows . . . So, I saw that you used to be a part of Dragon House, but then you recently went out on your own. When you were with them, what were you doing?

Cordaro: We had a house, and we all used to live together. We had an agent that represented us – Xcel Talent Agency. When I was in it, we would do NBA halftime shows, bar mitzvahs, shows with different artists. We’d go out and do it and then come home and practice and wait for the next opportunity.

Meredith: How many people are in Dragon House?

Cordaro: There’s 20 now.

Meredith: Why did you decide to go out on your own?

Cordaro: I just wanted to put a little more focus on my name.

Meredith: So you felt you were being promoted as a group as opposed to individuals?

Cordaro: It’s hard to explain. Being in a crew, we all worked under the same agency. We were all in competition. That’s not always friendly. I decided to take a journey on my own.

Meredith: What is your dream job or gig?

Cordaro: Just travel the world and see the whole world. I’d rather live out of a backpack to see the whole world than do anything I don’t want to do.

Meredith: Is there anywhere specific you want to go?

Cordaro: Tokyo, Dubai, China.

Julieann: Do you see yourself dancing for the rest of your life?

Cordaro: Yeah.

Meredith: Do you have a regular job during the week?

Cordaro: Yes, now I do. For the last four years, I didn’t. I was living strictly off of dance. But I don’t have an agent now, so I’m pretty much rebuilding and starting from scratch. I actually work in electronics now. And when I get home, I practice.

Meredith: Do you feel like you need an agent to get booked or can you do it on your own?

Cordaro: It depends. You can put out a video and it can go viral and then the connections will come to you, and you don’t need the middle man. But if you don’t have the connections and you have a middle man, he finds where you fit in.

Meredith: What kind of music do you listen to?

Cordaro: Araabmuzik. Favorite artist of all time. He remixes and creates different beats . . . I love all of these EDM songs. They sound like dreams. Hip hop . . . I’m not too sure about hip hop.

Julieann: So, you’re more into EDM?

Cordaro: Yeah, music that takes my mind to a different place.

Julieann: How did you find this artist?

Cordaro: In high school. I saw a video on Facebook that blew up because he can play the mess out of the MPC.

Julieann: What is an MPC?

Cordaro: It’s a device that has different instruments on there, and he uses it to make the drums and beats. You have to look the video up. I saw it in high school, and ever since, I just liked his music. I started shooting videos to his music. Last year, I ended up working with him.

Julieann: How did that happen?

Cordaro: His manager reached out to me. He flew us out, and we went to Chicago and New York.

Julieann: Wow, that’s awesome.

Meredith: Are there any dancers that you look up to as role models, or are you just trying to be unique?

Cordaro: Both. I actually came up under Nonstop. He made a YouTube video to "Pumped Up Kicks" that got 130 million views. He’s the guy that actually trained me. Then I branched off to learn more on my own.

Julieann: He trained you in Atlanta?

Cordaro: Yeah, Atlanta.

Meredith: Do you think Atlanta is a pretty good market for dance, or do you feel like you have to go to LA or New York?

Cordaro: Yeah, LA would be a bigger market, but as far as freestyle dancers, we have opportunities in Atlanta. It would be Atlanta, LA, sometimes New York. But LA is the main place for marketing because there’s always auditions and stuff going on. Pretty soon Atlanta will be like that too. We’ve got all the movies coming down here.

Julieann: Can you remember a time when you’ve had a creative roadblock?

Cordaro: Yeah, figuring out new moves – sometimes that can get kind of tough. You just have to keep going through it until your brain creates something. Or if you see something, you can use that as inspiration. Every dancer has that creative block. That’s why you have to practice every day.

Meredith: Where do you get inspiration from generally?

Cordaro: Other dancers. Movies. You might see something funny on a movie and think, “Can I make a move out of that?” Or something scary and try to make a move out of that.

Julieann: What do you mean making moves out of scenes in a movie?

Cordaro: Animation is pretty much "whatever you see, you try to bring it to life." If I see a robot acting silly then I’m going to try to imitate that robot. If I see something like "The Ring" – the scary scene with the girl when she comes up the steps then she twists her head – I will try to imitate that the best way I can to make it look almost like that.

Julieann: How does your family feel about your dancing?

Cordaro: They love it.

Julieann: They support you?

Cordaro: They always pushed me to pursue my dream. Whatever it is you want to get out of this world, you can get. You have to just keep going. Keep pushing – no matter how hard it gets.

Meredith: Has there ever been a point when you thought, "This is just too hard. Maybe I should do something else?"

Cordaro: Yep. But you just can’t quit. You put all this time into dancing and then you say, "I’m done," then you go to the grocery store and you hear a song . . . I couldn’t quit if I wanted to.

Follow Cordaro @cordaro777 and follow Aimee @aimeelabrecque. Watch the video at www.thestreetsmag.com

Photograph by Meredith M Howard

Photograph by Meredith M Howard

– Elliott Erwitt, Photographer www.magnumphotos.com

"You can find pictures anywhere. It's simply a matter of noticing things and organizing them. You just have to care about what's around you."

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

I was born in China. Now I am working in Paris as a photographer and an illustrator. What are three words to describe the city where you live?

I have been living in Paris for seven years. For me, Paris is both familiar and unfamiliar. It’s also a city of fashion and vintage, tension and comfort.

How is Paris comfortable and uncomfortable, and how is it similar and different from China?

I understand the place, the food, the museums, but the people, the culture . . . As I am a stranger who comes from a completely different culture, it is not easy to enter French social circles. It is similar to China in that the people like to stay in familiar social circles. It is different in that France is very, very open to its young creators.

The French talk a lot. That’s very good. And Paris is a huge museum – not just the museum of art but also the mix of people who come from different countries.

The reason why I got into photography and illustration is that firstly I’ve graduated from L’école Penninghen in art direction. Secondly, I like to observe different people on the street. This is a space of photography and illustration where I enjoy myself. I take pictures of the chicers on the street every weekend, and I also draw illustrations in my spare time.

Which activity is easier for you – photography or illustration?

At the moment, illustration is easier because I have been drawing for five years. I do not have a lot of experience with photography.

Allée des Cygnes, in the 15th district. It is just near the Eiffel Tower. I enjoy taking a walk on that street when the leaves are falling on autumn days.

As Paris is the capital of fashion, the Parisians are always very chic. I draw sketches of the passersby when I wait for the subway.

What are your hopes for the future?

I hope I can carry on taking pictures and drawing images to post on Instagram. This is my little secret garden showroom.

Photographer

Eduardo Asenjo Matus

Photographer

Eduardo Asenjo Matus

Where do you live, and what are three words to describe your city?

I live in Valdivia, Chile – one of the rainiest cities in my country. Three words to describe it are cold, gray and wet.

It all started with a small Fujifilm x10 – a premium compact camera with a retro style. Then I discovered the world of mirrorless cameras, very similar to my Fujifilm, but with better image quality and the option of changing lenses. I currently use an X-E2S with a 35mm f/2 and a fisheye 8mm. It’s a reflex in a compact body ideal for street photography.

Tell us about your love for the imperfection of the image.

When I started photography I always liked the noise and the movement – something similar to a dream. I have hearing problems, and I wanted to reflect this in my photographs. The speed was perfect to demonstrate the noise in a conversation. It is difficult to try to listen to a person in the city. I represent the noise with the blur in the image and what I can hear with the focus. One of the songs that inspired me for all of this was “The Sound of Silence” by Disturbed.

I realized that this type of photo does not attract much attention in my country since they only look for perfection in the image. My photographer friends made fun of me because I was only taking blurred pictures. They thought they were bad photos. But I was looking in the opposite direction of perfection. I fell in love with the imperfection of the image, sometimes using broken or dirty filters.

“I was looking in the opposite direction of perfection.”

To create the image, I use a very low shutter speed. First, I look for a place that I like and sit down to wait for the moment. I usually photograph the person who calls my attention to the group or people who walk at a different pace – slower or faster than the others. They stand out because of their speed. I use a neutral density filter to compensate for the light and long exposure. I use the intentional movement of the camera to create the blur and movement. It’s something similar to panning.

I’m very inspired by the music and grayness of my city. I like to meet people from other countries with the same interest and who understand the style of my photography.

I am the happiest person in the world riding my bicycle and spending time with my girlfriend.

I would like to be invited to and travel to different countries to exhibit my work. I would like to have a photo book and to work for an important magazine.

Follow Eduardo on Instagram @eduardo.asenjo.matus

I live in Cali, Colombia. There are a lot of words I could use to describe my city, but because of its sunsets, music, and people I’ll say Cali is warm, cheerful, and diverse.

I ride my bicycle daily around the city and look for stories to tell. I design and make backpacks. I listen to music and write poetry.

I started to take photographs in 2011 when I visited Bogotá, Colombia’s capital city. I walked daily through the center of the city with a borrowed camera, and that is when I began to understand that photography has the power to immortalize stories.

"Raíz de Árbol" (Tree Root) was born on a trip to Nariño-Colombia where I sought my identity as a photographer – to understand and recognize where I come from and what I want to preserve. I come from a farming family in Nariño and have another project looking to preserve recipes and family memories. "Tree root" is a metaphor for my photographs. I feel that I am a root, hidden and perceiving, and my feelings are the sprouting branches and leaves. Those are my photographs.

Once I discovered Vivian Maier’s work, she was a great inspiration. Her practical choice to work as a nanny – as well as her city scenes and portraits – constantly inspire me as I photograph the city streets in Colombia. The main difference is that I choose to share my work.

“That is when I began to understand that photography has the power to immortalize stories.”

I often visit a block in downtown Cali called "Carrera 10" where there is some destruction and a visible lack of equality, yet it is filled with simply beautiful scenes. I visit this street every week to buy materials for the backpacks I make, and it is full of humble people and contrasts.