3 minute read

John C. Johnson

Pioneer Trailblazer, Part II

BY MARK MCLAUGHLIN

Advertisement

tions: 7,400 and 7,150 feet. In addition, only 6 miles were above 7,000 feet on the cut-off, compared to 34 miles on the original Carson route, which made the detour theoretically usable year-round. At the time turnpike operators did not charge for the road itself, which usually existed prior to upgrades being made, but tolls were payable for bridges or improved sections that made wagon travel safer and quicker. Many emigrants on their way to settle California protested various tolls as well as the fee demanded at the Johnson Cut-off summit crossing.

In 1855, California legislators finally passed the California Wagon Road Act, which provided up to $100,000 for the construction of a state road over the Sierra, to be chosen by a panel of commissioners. Around that time Col. Johnson donated his section of road to the state and many improvements and realignments over the past 168 years now offer motorists the modern ease of trans-Sierra Highway 50.

Tragic end for Johnson

Despite their comfortable family life and Col. Johnson’s professional success, in March 1876, the 53-year-old entrepreneur and his eldest son George Penn (age 22) journeyed from their ranch to Cochise County, Ariz., to raise crops for sale to a U.S. Army post in the region. They squatted on well-watered land and planted 20 acres.

During the Gold Rush tensions were high between miners and indigenous California Indians whose land and culture had been invaded. During the so-called El Dorado Indian Wars of 1850-51, John Calhoun Johnson served as an adjutant for the California State Militia and appropriated the title Colonel when the army bivouacked on his land.

With some background in law, Col. Johnson occasionally served as a judge for local miner and property disputes. He was civic minded and an active member on the county’s Democrat Committee, the dominant political party in California during the 1850s. He also served as El Dorado County’s first treasurer (1850-1852).

During extensive explorations of Tahoe Sierra terrain, Johnson is credited with being the first Euro-American to discover Fallen Leaf Lake near Emerald Bay. He named the lake after his Delaware Indian guide, Fallen Leaf.

Johnson

Cut-off established

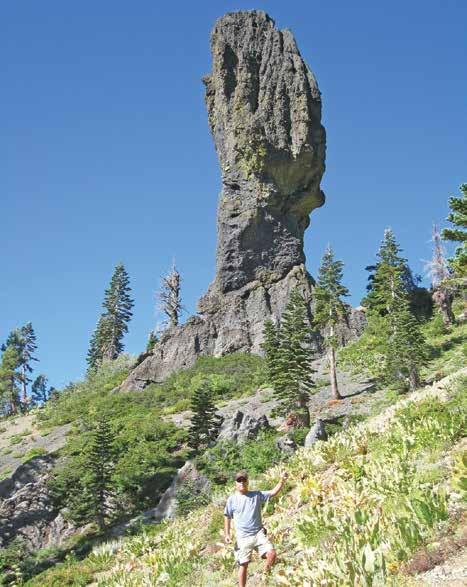

Never one to shy away from oppor- tunity, in 1852 Col. Johnson traced an old game and Indian trail that some prospectors had used to cross the mountains. Johnson chose this beaten track for a partial new alignment of the Carson Pass Emigrant Road and along with a hired crew manually cleared an alternative route.

The Johnson Cut-off split from the established Carson River route — saving 17 miles — and improved the trail to the point where it became the favored road into California. Despite Johnson’s efforts, the road was still dangerously steep and narrow, clogged with granite boulders and often blanketed in suffocating dust. Even so, the increased volume of wagon traffic drove more people to Johnson’s Ranch and money into his coffers.

A significant challenge for emigrants on the original Carson Trail was that it crossed the Sierra ridgeline twice over passes at 8,573 and 9,500 feet in elevation, an altitude plagued by winter-like conditions much of the year. The double-pass on Johnson’s Cut-off, however, had summits with much lower eleva-

In 1853, 19-year-old Emily Hagerdon migrated to California from Ohio with her parents and two brothers. In a letter she wrote of the transformative journey, she said that while crossing the Sierra in a thunderstorm her skirts became a hindrance when covered with mud so: “I tore my dress skirt off about four inches below the waistline and my underskirt being quite short it made it much easier for me to travel.”

As the Hagerdon’s family wagon rolled past the Six Mile House in October 1853, Johnson, now a 31-year-old, financially successful bachelor, spotted Emily and her practical but revealing traveling outfit. He said, “There goes the girl I will make my wife.”

The next day Johnson approached Emily’s parents, Luther and Fanny, and offered them jobs on his ranch. The family moved onto J.J.’s property and, as he predicted, John married Emily in January 1854. They had nine children — seven survived to adulthood. By all accounts the couple enjoyed a harmonious relationship.

In April 1860, Johnson’s Cut-off drew national attention when Pony Express rider William “Sam” Hamilton raced through it heading east with the U.S. Mail.

On Sept. 13, George left their isolated agricultural outpost for business. Returning to the ranch a few days later, he found his father dead, allegedly murdered by San Carlos Reservation Apache Indians. Farmhand Calvin Mowry had also been killed. The culprits ransacked the house, killed the poultry, stole horses and a mule, and shot Johnson’s dog, leaving it for dead. The field of crops was destroyed. Devastated, George returned to Placerville. In 1905, on behalf of his deceased father’s estate, George P. Johnson filed a civil lawsuit in Sacramento against the U.S. Government and Apache Indian [Nation] for restitution of Col. Johnson’s losses in the Arizona attack. According to sworn deposition statements from the proceeding, George declared that “Moccasin tracks and pony tracks were all over the field. There were moccasin tracks around where father was killed. The trail went straight toward the San Carlos Reservation…so we took them to be Apache Indians…” [from the government reservation].

I have no knowledge of how this case was settled, but it was a tragic and violent end for John Calhoun Johnson, a pioneering luminary of the Tahoe Sierra.

Special thanks to J.C. Johnson descendant Jim Knudsen and his wife Kris, as well as Sierra Historian Dana Scanlon, for assistance with this story. n