8 minute read

SELFRIDGES PUBLIC REALM: URBAN MARBLE

BY ALESSIA DELISI

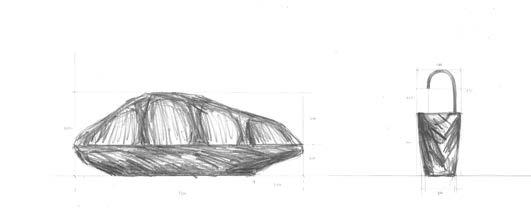

Sketch of the project

Left the entrance to the Selfridges department store on Duke Street, London Courtesy Djao-Rakitine

In London, in the Mayfair district, David Chipperfield’s project for the entrance of the Selfridges department store converses with a bench and a fountain sculpted in precious Italian marble. It is signed by the landscape architecture firm Djao – Rakitine.

The square is symbolically dominated by two sculptural elements, a marble bench and a fountain, while four trees define the architectural space, confusing nature and artifice. We are in London, facing the new entrance to the Selfridges department store on Duke Street. It was designed by the British architect David Chipperfield who, in addition to the entrance, imagined an environment dedicated to accessories, in the eastern wing of the structure, whose success story began in 1909. Playing with dark tones, in open contrast with the cream-coloured stone of the adjacent buildings - compared to which it is slightly set-back - Chipperfield’s project restores Selfridges to its former glory while maintaining its aesthetic autonomy. The imposing glass window that overlooks the entrance, which extends over three floors, is in fact framed by thin columns covered with bronze and rests on a black prefabricated concrete structure, with the two monumental pillars marking the portico. Essential, geometric, respectful of the historical heritage of the building and representative of its cultural importance - it was the first shop to make shopping a seductive experience, made up of expectations, courtesies, shop windows set up like works of art and illuminated day and night - Chipperfield’s design is part of a broader redevelopment plan aimed at reinforcing the identity of the store, improving, on the one hand, its urban presence and on the other, pedestrian circulation. Inside, plaster supporting columns, immaculate floors and ceilings recall the neoclassical architecture of the original building and, like the lights - elegant glass spheres that reference the type of lighting in vogue in the 1920s - maintain their independence with respect to the display system. The light stone of these spaces on the ground floor is then resumed externally, where white terrazzo floors seem to extend the space, accentuating the sense of continuity with the department store. The Djao–Rakitine, Henraux project is situated within this elegant context. A Landscape architecture studio founded in 2015, Djao–Rakitine worked in Moscow (with Strelka KB) as well as other cities in Russia, Luxembourg (with Promobe), it also developed original solutions for private clients in China and Slovenia. Its founder, Irene Djao – Rakitine, has experience behind her at the London studio VOGT (from 2009 to 2015) and another at the prestigious Atelier Jean Nouvel in Paris (from 2006 to 2009). Convinced that drawing by hand is essential for the development of ideas and projects, whereas digital design allows for the precise coordination of all the other members of the design team, including for Selfridges, Djao-Rakitine focused on the specific characteristics of the site, analyzing its historical, social, economic and natural aspects whilst creating prototypes and models for each phase. The result is a suggestive piece of street furniture that openly communicates with the Chipperfield designed entrance on Duke Street. Faced with the majestic black columns that dominate the portico, the Djao–Rakitine project is comprised of a bench and a marble fountain but also includes a redevelopment of the entire street experience - from the wide and renewed flooring to the lighting - all enclosed within the symbolic confines of four trees to embellish it. The square appears as a meeting point and a place of

The Djao–Rakitine project is comprised of a bench and a marble fountain but also includes a redevelopment of the entire street experience - from the wide and renewed flooring to the lighting - all enclosed within the symbolic confines of four trees to embellish it.

Front view of the bench and of the fountain. Courtesy Djao-Rakitine

Section of the project

Both pieces of furniture are made of precious Italian marble; through their blunt shape, they help give the idea of a natural environment that potentially extends beyond that which can be seen, in contrast to one of the busiest areas in London.

Render

Right The entrance of the Selfridges department store on Duke’s Street, London Courtesy Djao-Rakitine

reunion, a space that, although rising within the city, allows you to hide away from its bustle. In a metropolis where most public drinking fountains have disappeared, the Djao–Rakitine fountain offers visitors, residents and employees of the district the pleasant opportunity to fill their bottles with water, thus reducing the proliferation of single use plastic bottles. Thanks to its four different shapes and sizes, the bench instead provides a place for different people to meet or take a rest. Both pieces of furniture are made of precious Italian marble; through their blunt shape, they help give the idea of a natural environment that potentially extends beyond that which can be seen, in contrast to one of the busiest areas in London. In fact, in such a soil the possibility of planting and growing trees was in fact very limited. This is why the selected species are the result of a careful study of the soil, which also includes the creation of grids made to optimize the growth of the trunks. And this is also why the choice of the marble to be used for the two monoliths fell on the ancient Verde Luana, a particular type of rock characterized by surprising undulating veins in different shades of green, interrupted by a number of white inserts. Extracted from the Apuan Alps, in Tuscany, where it was formed about 25 million years ago, therefore Verde Luana is the material that is best suited to evoke, with its serpentine consistency and the continuous and transverse movement, a mountainous landscape made of water and stone. As Irene Djao–Rakitine explains, that during the creation she chose to smooth the corners, focusing on the organic nature

The bench and the fountain by Irene Djao–Rakitine can also be read in this manner, which, although conceived as unique objects, carry with them - because of the techniques used - the germ of reproducibility. Accordingly, it is not surprising that today more and more companies are choosing marble for projects with a strong appeal for identity and an assured visual impact.

Above Some details of the bench and of the fountain

Left The entrance to Selfridges department store on Duke Street, London Courtesy Djao-Rakitine

of the form, the creation of the bench and the fountain has seen the succession of many phases: “I started making sketches by hand. So I modelled and sculpted the two elements with clay, many times and with many variations. When, we - at the studio - Selfridges and the David Chipperfield Architects were satisfied with the aesthetics, proportions, functionality and complementarity of both objects, we scanned the models in 3D and started digitally refining the details. The 3D digital models were then used to cut stone blocks with a CNC machine. Finally, I worked on the manual finishing of the sculptures with Dorel Pop, a very experienced craftsman, and Lorenzo Carrino, who assisted us in the manufacturing process, all of this was made entirely in Tuscany at Henraux”. Thanks to this extraordinary combination of techniques and skills, Djao–Rakitine has created a work that, while remaining in line with the general ethos of Westminster and the range of materials that characterizes it, presents itself as a unique moment in the Mayfair district, whose tipping point is above all in the clever union of technology and craftsmanship that it reveals. Despite being massive and secure, the shapes created by Djao–Rakitine evoke a sense of lightness, accentuated by the light color and the extreme smoothness of the marble. The characteristics of nonreproducibility, as well as a link with the territory of extraction, make it a precious material and in some ways unique. The contribution that this can give to design - understood as the production of objects in series - is therefore in terms of an added value that is added to the talent and creativity of the designer, whose creations thus become comparable to works of art. The bench and the fountain by Irene Djao–Rakitine can also be read in this manner, which, although conceived as unique objects, carry with them - because of the techniques used - the germ of reproducibility. Accordingly, it is not surprising that today more and more companies are choosing marble for projects with a strong appeal for identity and an assured visual impact. After all, as the designer Martino Gamper asked some time ago, why venerate an industrially produced object if there are still hundreds of copies? The meeting of marble and design does this: it reconciles what is only seemingly irreconcilable and does so at a time when the debate on sustainability and the creation of objects with a longer life cycle is particularly active. In a world where the abundance of waste is the other face of consumerism, marble is in fact among the few materials capable of tracing a line, lasting over time, which unites man in an exemplary way - his artistic and technological skills - with nature.