8 minute read

INTERVIEW FOR TWO: FRANCESCO ARENA AND DAVID HORVITZ

BY LORENZO BENEDETTI

Francesco Arena and David Horvitz are two of the three winners of the last edition of the Henraux Prize. In order to create their works, they have Worked white marble From Altissimo in the quarries and in the Henraux establishments in Querceta. Lorenzo Benedetti interviews them for us.

Francesco Arena (top) and David Horvitz (bottom) Photo by Nicola Gnesi

FArena

Francesco Arena

Lorenzo Benedetti: In your work Cubic meter of marble with linear meter of ash there is a combination of different materials. Marble and ash, both extreme materials, are balanced in their precise equilibrium, as often occurs in your works. How was this work conceived? Francesco Arena: Cubic meter of marble with linear meter of ash is a work on time or better on times. There is no single time, man’s time is not that of stone and vice versa. The materials have their own times. The time of marble is that of the earth: geological eras, gigantic opposing forces that generate the hard, resistant material that men have always used to build dwellings that have a longer life than those who built and inhabited them. It is a material used to create monuments that serve to make a lifetime and a memory connected to it last. The ashes of the cigars I smoke is the time of a moment, a small fraction of time repeated over time that is somehow marked by its daily repetition. The ash is what remains of a breath, the physical part that you can touch is very light but resistant, it can blow away with a breath but it is practically indestructible just like the marble that you can reduce to dust but you cannot make disappear completely. The two materials in their natural state, one in the form of a mountain and the other in the form of an unstable mound, are “ordered” according to a rule given by man, a measure, that of the cubic or linear meter, that we use to establish the space we occupy in the world, to give order to the random.

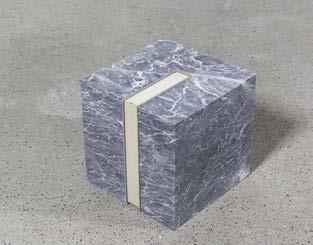

L.B.: The marble you use has a specific character. Its veins reference the movements of the smoke. This aesthetic element of marble is also linked to the combination of different elements that often put man in dialogue with the landscape. When did you first use this combination of materials? F.A.: The movements of smoke last a moment, the air immediately disperses the grey and irregular sketches of the smoke, while the veins of the marble have a very long, eternal life. the work is born from these comparisons and it is also for this reason that the line drawn and filled with ash, it is completely different from the abstraction of the curved lines of the veins or spirals of smoke. I used ash and marble together for the first time in Cubic meter of marble with linear meter of ash but later I made Ash Horizon where ash and stone are used together. That work is a block of unpolished stone, left in its natural ash grey colour from which a column/plinth has been cut to my height, 166.5 cm high, 20 cm wide and 20 cm deep. The column at 8.5 cm from one of its ends it was cut again with a disk that takes 11mm of material away during cutting, and removes it. In this way, the column was divided into two pieces, one 157 cm high - as far as the ground distance at the base of my eyes - and another 8.5 cm piece - as the distance from the top of my eyes to the top of my skull. When the sculpture is mounted, the 11mm scrap taken away by the saw is replaced by 11 mm of cigar ash collected over time. In this way, the recomposed column has my same height again and the centimetre of cigar ash corresponds to my eye level, my horizon. Before these works, I had used marble or stone together with diaries of different years, opened at right angles and joined together so as to form something solid. A block of stone is cut so as to fill the empty space between the two diaries, as in Marble between 80 years.

L.B.: The human form is often present in your works. Geometric, translated into a way of measuring distances, weight or

Clockwise from the top: Francesco Arena, Cube (Petrolio), 2018, marble, book, 21x21x21 cm Courtesy Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Milan Photo by Lorenzo Palmieri

Francesco Arena, Lost Horizon, 2016, stone, books, 157x32.5x16 cm Courtesy Sprovieri, London Photo by Roberto Marossi

Francesco Arena, Marble between 80 Years, 2018, marble, 2 diaries, 16x12x16 cm Courtesy Studio Trisorio, Naples Photo by Roberto Ruiz

Francesco Arena, Metro cubo di marmo con metro lineare di cenere (Cubic metre of marble with linear metre of ash), 2018, marmo macchietta, cigar ash, 100cm x 100cm x 100cm Photo by Nicola Gnesi

The materials have their own times. The time of marble is that of the earth: geological eras, gigantic opposing forces that generate the hard, resistant material that men have always used to build dwellings that have a longer life than those who built and inhabited them.

time. There is also a clear reference to the artist’s point of view, the horizon from which he looks and measures the world. In the moment of transformation of the figurative into the abstract there is a kind of universal language, which is abstract but at the same time creates links with different times, places and cultures. Could one often interpret your works as a series of abstract self-portraits? F.A.: The shape and size of many of my works are linked to the size of my body, they are self-portraits in subtraction where verisimilitude is not sought with my appearance, but fidelity with a given space occupied in the world. The sculpture is another body with which we seek a relationship, it is an object whose use is not only visual but which also requires the perception of the physical characteristics of the material from which the sculpture is made. The apparent abstraction of selfportraits is actually the result of a process of gradual subtraction that serves to highlight a cut and dry given, for example, the height of my visual horizon, which, in the work aspires to be a shared reference point.

David Horvitz, A Mountain / A Sea, 2018, Statuario Altissimo, various dimensions Photo by Nicola Gnesi

DHorvitz

When they take a stone, they write their name. I ask for first names only. I don’t want it to be a certain person. A “David” instead of a “David Horvitz”. I don’t want it to be about who has it, but that someone has it.

David Horvitz, A Mountain / A Sea, 2018, Statuario Altissimo, various dimensions Photo by Nicola Gnesi

David Horvitz

Lorenzo Benedetti: For the project at the Fondazione Henraux last year you showed a work titled A Mountain / A sea in which you are reversing the idea that is common about marble like a heavy material. In your project this material seems more to become a form of communication. How did the project start? David Horvitz: It is a story. A kind of coincidence that I brought the work. The movement of marble, of people and of stories. Maybe a piece of stone carrying with it a story. I put a piece of the marble on the side of the freeway in Los Angeles. Connecting these two places. To me, this was the main work, this little gesture. documented in photos and a text, translated. Translation is moving between two points, like the stone moving between two points. In the show was a pile of rock, crumbled. All from a single block of white marble. People could take a piece home. This act, this movement, was to parallel what I did in Los Angeles, and the mountain would disappear, it would disperse, though it’s still there, just in pieces in a distributed decentralized form. Maybe on a shelf or in someone’s pocket.

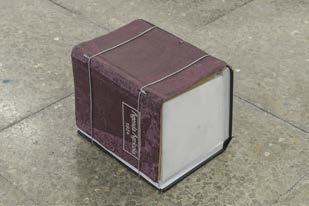

L.B.: In your practice there is a form of entropy. Dispersion/diffusion are the translation from a stone to a story. Do you have a way to record the scattering of the work? D.H.: There is a book for people to write their first name’s only. When they take a stone, they write their name. The book is left as a document of names anchoring the stones that are no longer there. I ask for first names only. I don’t want it to be a certain person. A “David” instead of a “David Horvitz”. I don’t want it to be about who has it, but that someone has it. The book as an anchor holding the weight of the stones, or of the stories.

L.B.: In your project you deal with the concept of monument in a different way. A block of marble acquires a different status when it moves and links different places and stories together. There is a relationship between the migration of people and migration of stones. The white stone that is now at the interchange between two freeways is coming from a famous quarry in Italy. The mountain is fragmented and the people take the stone with them like a fractal of a landscape. It looks that disappearing is a form of showing. Like the act of carving a mountain is making the form. Is for you the void a form? D.H.: It depends how we understand the void. For me the work very much has a form, its form is just in movement. Does the wind have a form? Obviously, yes it does. But at each moment that form is air being scattered across a landscape. For me, maybe the word scattering is more apt than void. In its absence in one place, it is present somewhere else.