THE VARSITY

21 Sussex Avenue, Suite 306 Toronto, ON M5S 1J6 (416) 946-7600

thevarsity.ca thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity thevarsitypublications the.varsity The Varsity

Vol. CXLV, No. 3 MASTHEAD

Eleanor Yuneun Park editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Kaisa Kasekamp creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Kyla Cassandra Cortez managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Ajeetha Vithiyananthan managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Maeve Ellis online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Ozair Anwar Chaudhry copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Isabella Reny deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Selia Sanchez news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

James Bullanoff deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Olga Fedossenko assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Charmaine Yu opinion@thevarsity.ca

Opinion Editor

Rubin Beshi biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Sophie Esther Ramsey features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Divine Angubua arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Medha Surajpal science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Jake Takeuchi sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Nicolas Albornoz design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Aksaamai Ormonbekova design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Zeynep Poyanli photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor

Vicky Huang illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration Editor

Genevieve Sugrue, Milena Pappalardo video@thevarsity.ca

Video Editors Emily Shen emilyshen@thevarsity.ca Front

Andrew Hong andrewh@thevarsity.ca

Razia Saleh utm@thevarsity.ca

UTM Bureau Chief

Urooba Shaikh utsc@thevarsity.ca

UTSC Bureau Chief

Matthew Molinaro grad@thevarsity.ca

Graduate Bureau Chief

Vacant publiceditor@thevarsity.ca

Public Editor

Associate Senior Copy Editors

Vacant Associate News Editors

Vacant

Associate Opinion Editors

Caitlin Adams, Ameer N.

Vacant Social Media Manager

Vohra

Associate Video Editors

Copy Editors: Alex Lee, Aryan Chablani, Callie Zhang Cindy Liang, Despina Zakynthinou, Dhritya Nair, Jahda Waldron, Jessica Lee, Jessie Schwalb, Joao Pedro Domingues Juliet Pieters, Madiha Syed, Madison Truong, Maram Qarmout Mari Khan, Matthew Cancelliere, Nandini Shrotriya, Nyela Modrek, Olivia Bello, Raina Proulx-Sanyal, Sofia Tarnopolsky Valerie Yao, Yasmeen Banat, Yulia Miyajima, Zoe Eaton Designers: Lal Ozsahin, Kevin Li, Bruno Macia, Kala Kamani

Cover: Courtesy of TIFF, design by Kaisa Kasekamp

BUSINESS OFFICE

Ishir Wadhwa business@thevarsity.ca

Business Manager

Rania Sadik raniasadik@thevarsity.ca

Business Associate

Eva Tsai, Muzna Arif advertising@thevarsity.ca Advertising Executives

The Varsity acknowledges that our office is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. Therefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

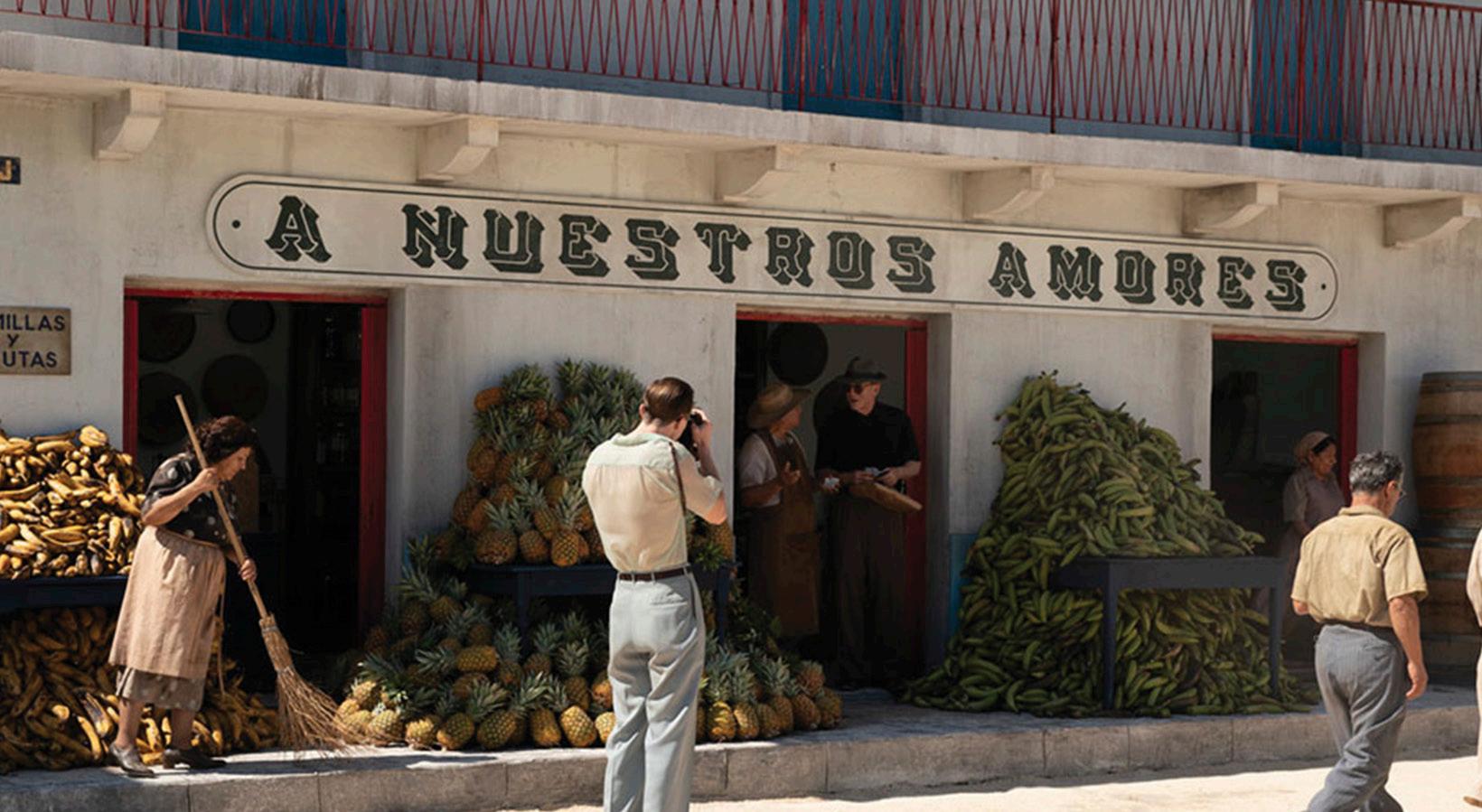

TIFF, we love you Heartbreak feels good

Divine Angubua Arts & Culture Editor

The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) is special in the way that it brings people together. From the simple people obsessed with movies, to the high-flying stars that descend upon that red carpet each day, to the journalists that flit around the streets of Toronto in search of great stories. It feels good to be a part of a culture that is bigger than yourself: an enclave that this year gifted us with new magic from the likes of David Cronenberg, Luca Guadagnino, Edward Berger, Sean Baker, Pedro Almodovar, and Halina Reijn.

Sitting in those theatres watching new and old stars shine, I am reminded of Nicole Kidman’s famed 2021 AMC Theatres ad, and the beautiful adage that at the movies we are not just entertained, “but somehow reborn.” Heartbreak

does feel good in a place like this, because that brief pain nudges us towards a better place: a realization, a transformation, maybe even salvation.

What I saw at TIFF this year made me more sensitive to love, more hopeful for the human spirit, and appreciative of the complex struggles out of which many of these films were born. Thise festival is proof that every year is a great year for film if you look hard enough, because there are always, always people who are trying to make this world a better place however they can.

The world is a better place with films that are good, nasty, and sometimes even morally corrupt. This year, I am grateful for films like Cronenberg’s disquietingly necrophilic fantasy

The Shrouds, in which a grieving widower watches the body of his dead wife rot; Reijn’s Babygirl, in which Kidman plays a CEO in a

BDSM-tinged affair with a junior employee; and especially Berger’s Conclave, in which the thesis of the men of the Catholic papacy is wickedly defamed.

This issue is for the storytellers and story seekers, the romantics and the stoics. May these films and these reviews inspire you to go and see more. May the power of good film push you towards that better place where art may turn into alchemy, and grief turn into proof that love was here.

That’s enough said.

Enjoy our TIFF and PopCulture issue.

One person sent to hospital with minor injuries after three-car collision on Bloor Street West

James Bullanoff Deputy News Editor

On September 14 around 3:00 pm, a car crashed into the front gates of the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at 315 Bloor Street West following a threevehicle collision on the same street.

In an email to The Varsity, Toronto Police Service Media Relations Officer Shannon Eames wrote that TPS received a call at 3:28 pm reporting the crash.

According to Eames, one person was transported to the hospital with minor injuries.

The Varsity was unable to determine the circumstances of the collision, but by 4:15 pm, two separate vehicles remained damaged on the road in front of the Munk School.

U of T did not respond to The Varsity’s r equest for comment in time for publication.

CORRECTIONS

In issue 1 of The Varsity, a News article titled “UTSU announces Student Senate elections plans and new platform for clubs’ funding” incorrectly stated that the UTSU Student Senate is the union’s sole governance organ. In fact, the Student Senate is a governance organ solely responsible for advising the union’s Board of Directors about student life.

In last week’s issue of The Varsity, a Sports article titled “Full out and on top: Varsity Blues Dance Team dominates the 2024 season” misspelled Blues Dance Team’s co-captain Sara Da Silva’s last name as De Silva.

In issue 1 of The Varsity, a Business article titled “U of T financial statements reveal university expenses outpace revenue growth” incorrectly conflated university endowments with donations and stated that the university’s ability to fund its programs is influenced by investors. The article has been edited to reflect that the university’s revenue consists of donations and investment income, and that the government, research sponsors, and donors can influence the school’s ability to fund projects. This article has also been edited to reflect that $305 million of the school’s net income was allocated to capital assets, not debt repayments. The following explanation of the university’s debt-burden ratio has thus been removed.

Student unions lobby to make 1.0 credit of program requirements eligible for CR/NCR

Olga Fedossenko Assistant News Editor

In August, U of T’s student unions launched a tricampus campaign to change the university’s Credit/No Credit (CR/NCR) policy.

The University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU), the University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU), the Scarborough Campus Students’ Union, the Arts and Science Students’ Union (ASSU), and the Association of Part-time Undergraduate Students are proposing to extend the CR/NCR deadline until final grades are released and to allow students to apply the policy to at least 1.0 credit of their program requirements.

What is the CR/NCR policy?

CR/NCR allows students across the three campuses to complete a distribution requirement or elective course without affecting their GPA.

In a nutshell, a student can set a course’s status to CR/NCR on ACORN before the final exam period, which begins on December 3 for the fall 2024 term. Once the course’s status is changed, the student’s final grade for the course will not appear on their transcript. Meaning, the grade would not impact the final calculations of the student’s GPA. Instead, the transcript will show a ‘credit’ notation if the student received at least 50 per cent as a final grade for the course or a ‘no credit’ if they have not. Currently, a student may select up to 2.0 credits for CR/NCR. They cannot apply or remove the status after the exam period starts, and CR/NCR can’t be used to satisfy program requirements.

Prior policy changes

U of T student unions have lobbied for changes in the CR/NCR policy since the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 2021, the ASSU issued a proposal for the Faculty of Arts & Science (FAS). The union suggested that the university extend the CR/NCR deadline until after term grades are released and allow the policy to be applied to program requirements, not just elective courses. Other unions are now lobbying for the same changes.

FAS agreed to permanently extend the CR/NCR deadline to no later than the last day of classes since the fall semester of 2021, but declined the union’s proposal to apply the policy to program requirements.

The union’s current campaign In an interview with The Varsity, UTSU’s Vice President (VP) Public & University Affairs Avreet Jagdev said that the unions believe that “students should have access to complete and accurate information about their performance in courses so that they can make informed decisions regarding the CR/NCR option.”

According to Jagdev, the unions have already conducted outreach to students across all three campuses and are continuing to collect responses through a survey they created. The survey asked students questions about how they’ve used the CR/NCR policy and how it has affected their mental health.

UTMSU’s VP University Affairs Sidra Ahsan added that extending the CR/NCR policy has been a persistent request from the student community and that it’s an issue that affects many students’ mental health and academic careers.

“The university has restated their emphasis on promoting mental wellbeing amongst students many times, yet they have left this issue unaddressed over the years,” she said.

The unions plan to use the survey’s results to advocate for an extension of the policy in the future.

In a statement to The Varsity, a U of T spokesperson noted that the university “welcomes student input to improve educational outcomes.”

Students’ response to proposed changes In interviews with The Varsity , many students expressed their support for the unions’ efforts to extend the CR/NCR deadline.

Tiana Manias, a fourth-year forensic chemistry student, said she believes that

“[students] should be able to decide [on whether] to CR/NCR [a course] after reviewing [their] final mark.”

“My fear for this change would be students taking advantage of this and [applying CR/ NCR to] crucial courses [where] they need to understand the topic they are studying,” said Manias.

She continued, “If you get a mark that would increase your final grade you should be able to keep it.”

Yet, some students disagreed with the unions’ proposal to allow using CR/NCR on program requirements.

Fourth-year physics student Logan Blaskie said that this change could also harm students’ applications for graduate school.

“Inside the area of physics, there are several courses that professors at other universities have told me are tantamount to your GPA when being considered as a potential graduate student,” he said. “[The proposed change] could presumably lead to individuals unknowingly [using] CR/NCR [on] some of these important courses… and potentially hurting graduate school applications.”

Fourth-year ethics, society, and law student Valerie Yao opined about the flaws in U of T’s current CR/NCR policy for The Varsity in 2023.

In an email to The Varsity, Yao expressed her support for the student unions’ initiative to make 1.0 credits of program requirements eligible for a CR/NCR notation.

“The university thinks that not allowing [a] CR/NCR on courses that count towards program requirements holds up its academic standards, but this concern is not so relevant,” she said. “U of T’s courses are hard enough already and just because students CR/NCR 1.0 credit for their program cannot show that the student didn’t finish the program satisfactorily.”

Disclosure: Valerie Yao is a Varsity Contributor who has written an opinion article on the CR/NCR policy in Volume 143.

A look into the current accessibility issues of modern-day cinema

Sharon Chan Varsity Contributor

On September 5, the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) returned for its 49th edition. Over 11 consecutive days, local and international films will be screened for film lovers and creators of all ages and backgrounds.

While film lovers and celebrity admirers are excited about one of the world’s largest annual film showcases, the festival has recently faced backlash for failing to accommodate attendees with accessibility needs.

Closed captioning controversy

Closed captioning is the display of text to aid deaf, deafened, or people with loss of hearing that includes not only dialogue but also descriptions of sound effects. As mentioned on TIFF’s accessibility page, people can request CaptiView — a personal listening device that can be requested from their Box Office or Front of House staff.

The portable device, with a small screen for viewing the film with closed captioning, features ‘shutters’ to prevent disturbing others watching the film.

Advocates have been urging TIFF to require captions for all films, as many are frustrated with the current system. In an interview with CBC, Michael McNeely, a 28-year-old film critic who experiences both vision and hearing loss, disclosed that the closed captioning devices provided at the festival were not functional.

He suggested that TIFF’s failure to accommo-

date its diverse audience as a leader of film festivals indicates that other film festivals are likely “falling behind.”

On TIFF’s website, the festival emphasizes its commitment to “treating all individuals with respect, dignity and fairness by removing physical, social and economic barriers to participation.”

Following McNeely’s experience, film critics and accessibility advocates are pushing to make captioning a requirement for movies entered into TIFF.

Current technology

Others have also shared negative experiences with the same closed-captioning technology that failed for McNeely.

In an interview with The Varsity, Catherine Dumé, a political science graduate student and former copresident of the University of Toronto Accessibility Awareness Club highlighted a few major issues with CaptiView: it is clunky and often out of sync with what is being shown on the movie screen.

“[It] looks like something that came out in the ’90s and just never became modernized,” said Dumé.

Last year, Dumé also wrote on the case for movie captions in theatres for The Varsity. Dumé wrote that she “would love to see the day when we actually have words on screen by default.”

Closed captioning on the movie screen

Kate Maddalena, a UTM professor specializing in technical communication and media studies, also called for greater accessibility as an important step in film.

Maddalena believes that film has always played a critical role in shaping our perspectives of the world.

“Cinema is lots of things… it’s a way to put on someone else’s head for a while and [see] the world in a different way,” said Maddalena in an interview with The Varsity

When asked about the current push to mandate captioning as a requirement for movies, Maddalena expressed full support for the initiative.

“It’s not a huge ask. Film technology is so advanced — they’ve got CGI that can recreate actors.”

Maddalena also acknowledges that displaying closed captioning on the movie screen could potentially be distracting for viewers. To minimize the distraction, she believes there needs to be a balance between aesthetics and inclusivity.

Film critics and accessibility advocates hope that TIFF can learn from its past mistakes and ultimately become a driving force for an inclusive cinematic experience for everyone.

Disclosure: Catherine Dumé is a Varsity contributor who has written an article on closed captioning in film in Volume 144.

Eshnika Singh Varsity Contributor

On September 10, US Vice-President (VP) Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump met for the highly-anticipated presidential debate in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The debate was hosted by ABC News moderators, David Muir and Linsey Davis.

The candidates debated several topics, including immigration, climate change, US intervention in Afghanistan, gun control, fracking, and much more. With the presidential election coming up on November 5, The Varsity spoke to some U of T students and faculty about key highlights from the debate.

Who are the candidates?

Donald Trump is the Republican Party candidate and 45th US president. In May, Trump was found guilty of 34 counts of felony convictions for falsifying business records and was later denied a delay for his sentence. Two months later, Trump was injured after an assassination attempt during a rally in Butler, Pennsylvania. At 78 years old, Trump is the only US president in history with no political or military experience before taking office, and the first US president to be impeached by Congress twice.

Current VP Kamala Harris became the Democratic Party’s presidential candidate after President Joe Biden stepped down from the race. Harris took office as the VP in 2020, making her the first woman VP in US history. In 2003, Harris was elected District Attorney of San Francisco and twice served as attorney general of California from 2010 to 2017. Now, at 59 years old, she is the first Black, Indian, and woman presidential nominee.

The debate started off with questions about the economy and the cost of living. In response, Harris outlined her plan to mitigate the housing crisis by offering a tax cut of 6,000 USD to families with newborns and assisting small businesses with a 50,000 USD tax deduction. Trump outlined his plan to impose import tariffs and make other countries “pay [the US] back.”

Jack Cunningham, an international relations professor with the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, explained what effect Trump’s plans would have on Canada in an email to The Varsity : “[Trump’s] proposed 10 per cent [tariff]… on all imports would do serious damage to a Canadian economy still heavily dependent on exporting to the US market.”

Trump defended the overturning of Roe vs. Wade — the 1973 decision which protected women’s rights to have an abortion under the US Constitution — claiming that Democrats support what Trump describes as “abortion in the ninth month” or “execution after birth.”

Trump also mentioned that 85 per cent of Republicans, including himself, believe that abortion should only exist for cases of rape, incest, and saving the life of a mother.

Moderator Davis fact-checked Trump’s claim on the Democratic Party’s abortion policy, saying, “There is no state in this country where it is legal to kill a baby after it’s born.”

The moderators made more corrections later into the debate as well, regarding Trump’s false claims about immigrants in Ohio eating pets and about losing the 2020 presidential election to Biden by a “whisker.”

Harris countered the former president: “In over 20 states, there are Trump abortion bans which make it criminal to provide health care…

[and some of which] make no exceptions for rape and incest.” She emphasized that the government and Trump should not be telling a woman what to do with her body.

Priya D’Souza McDonough — a fourthyear U of T student studying Near & Middle Eastern Civilizations and art history, and registered to vote in New York — expressed their concerns about access to abortion under both governments.

“Although the Democratic party claims to fight for the right of queer Americans to exist and to pursue happiness in this country, they have done precious little to actually protect those rights. The same thing can be said about access to abortion after the overturning of Roe v. Wade,” they wrote in an email to The Varsity

The two candidates were also asked about their stance on the Russo-Ukrainian war and Israel’s war on Gaza.

Harris stated that she condemns the actions of Hamas on October 7 and believes in Israel’s right to defend itself. However, she also recognized that “innocent Palestinians have been killed.” Harris called for a two-state solution, release of Israeli hostages, and a ceasefire deal.

When asked about Israel’s war on Gaza, Trump stated that the war would have never started if he were president. He extended his statement to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, saying that he would end the war in Ukraine if he is elected president.

McDonough commented on the two candidate’s views on Israel and Palestine. “What also worries me, of course, is both candidates one-upping each other on how much they ‘love’ Israel, and will continue to send Israel weapons that have been proven to be dropped on civilian areas [and] in ‘safe zones.’”

On September 10, Israel bombed tents sheltering displaced people in al-Mawasi: an Israel-designated 'safe zone' in southern Gaza. As of writing, Al Jazeera estimates that more than 40,000 Palestinians have been killed in Israeli attacks.

Liam Cox — a third-year student from New York studying history and international relations — commented on the state of the elections, writing that, “A Republican federal government is likely to have negative effects on American international prestige and power projection, climate change, safety, maneuverability, equality, etc.”

The final countdown

After the debate, the polls have not shifted much. According to ABC News polls, Harris is seen as the debate winner. As of writing, Harris is leading 48.1 per cent to Trump’s 45.4 per cent post-debate, according to Project FiveThirtyEight polling data. Although Harris called for another debate, Trump has stated that he won’t debate her again, claiming that he had won.

While some have shown support for Harris, others have questioned how she defines herself. For Cunningham, Harris has “a less well-defined image in the minds of most voters, and that [image is] largely negative.”

“In the September 10 debate, Harris had to do several things,” wrote Cunningham. “She had to provide voters who didn't think they knew enough about her, and in many cases thought she was too liberal for their tastes, with a sense of who she is and reassure them that she is an acceptable alternative to Trump.”

“Even [Trump’s] most outrageous antics won’t fundamentally change the way most people view him, so the election is likely to remain very close,” wrote Cunningham.

Hollywood

September 17, 2024

varsity.ca/category/business biz@thevarsity.ca

the finance behind filming at

Architecture, tax breaks, and “one of the best shitty jobs”

2024–2025 fiscal year.

Movies and TV shows filmed at U of T range from The Boys (2019) to The Incredible Hulk (2008) You might have seen film crews around campus, covering up our coat of arms with crests for imaginary schools, while some of your classmates may have also worked on those sets.

U of T holds a particular appeal for studios, not just because it’s located in a film-making hub with tax incentives, but also due to its varied architecture. Filming on campus generates revenue — both for the university departments that book spaces and coordinate with producers, and for the students who land gigs as background actors. Some of these students told The Varsity that opportunities in Toronto have allowed them to gain experience, make money, and have fun — all in a day’s work.

Who gets paid?

U of T charges studios and production agencies

$4,000 per day to film on the St. George campus. The charge doesn’t include additional costs like food or city-issued filming permits. However, other locations in Toronto may cost film companies more. For instance, the Ontario government charges

$6,700 per day for studios to shoot interior scenes at select public courts and offices in Toronto.

There are no fees for students to use shared spaces during regular building hours to film for class assignments or for extracuriculars, but the school does not facilitate filming requests for student's personal projects.

The event-booking branches on each campus — Campus Events at UTSG, Hospitality & Ancillary Services at UTM, and Retail & Conference Services at UTSC — collect those fees and coordinate with studios. These three branches are ancillary units: they operate semi-independently from the university, submit separate budgets, and aim to turn a profit, which they pay into U of T’s massive operating budget.

UTSC Conference Services’ 2024–2025 budget forecasted that the unit — which also rents out campus spaces for a summer camp and preuniversity orientation — will bring in $2,791,000 in revenue during the fiscal year from June 1, 2024, to April 30, 2025. However, after covering expenses, the unit expects to make $41,000 in net income.

When it presented its budget in February, UTM Hospitality & Ancillary Services projected $798,886 in revenue from facility and space rentals during the

These amounts represent only a small fraction of the university’s $3.52 billion in total revenue. The revenue from event-related ancillaries is also small compared to other ancillary units. For instance, the university expects residences at UTSC alone to bring in $711,000 in net income for the 2024–2025 fiscal year.

U of T did not respond to The Varsity’s questions about how much money it made from renting out campus spaces for filming.

Toronto on top

US-based studios often choose to shoot in Canada because of its favourable exchange rates and substantial benefits for companies that hire local actors and crews. Other Canadian universities also host movie studios — for example, scenes from the romcom movie She’s the Man were filmed at the University of British Columbia, and students at Mount Royal University watched actors from the TV series The Last of Us run past their classroom windows.

But Toronto comes out as a top location for shooting screen media. In 2024, MovieMaker Magazine rated Toronto as the best city to live and work in as a filmmaker. Additionally, the Toronto International Film Festival — one of the most prestigious film festivals in the world — enhances the city’s prominence in the film industry.

The City of Toronto aggressively markets itself to studios, highlighting its “multicultural pool of actors” and skilled crew members on its website. The provincial agency Ontario Creates offers logistical and funding support to studios through targeted programs and by leveraging public and private partnerships. This helps studios secure tax credits that, when combined, can offer up to 45 per cent savings on labour costs and 35.2 per cent savings on overall production costs.

In 2021, the screen media industry in Toronto was valued at $2.5 billion. According to the comprehensive movie database IMDb, more than 17,000 films have been shot in the city. However, Toronto rarely appears as itself in movies, as its aesthetic, yet generic, settings more often stand in for American cities.

A 2021 report commissioned by the City noted that, despite the increased production of foreign movies, domestic movie production declined in Toronto since 2014. “Producers, especially domestic ones, are being crowded out of the Toronto production market,” the report states.

U of Television?

Along with being situated in Toronto, U of T’s ‘Harvard of the North’ reputation attracts studios seeking an Ivy League stand-in. In the cult classic Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle, Knox College stands in for Princeton University, while U of T buildings including Whitney Hall and the McLennan Physical Laboratories double as MIT and Harvard buildings in Good Will Hunting.

The varied architecture also lends itself to horror — for example, Robarts Library appears as a mega-prison in the action horror movie Resident Evil: Afterlife

Along with feature-length films, U of T also provides interesting settings for commercials. Senen Sevilla has worked as a set decorator on ads for brands like McDonalds and Money Mart. He told The Varsity that his role includes “[wearing] many hats” — from buying furniture to setting up and taking down sets.

Sevilla said that filming at U of T excites him. “A lot of commercials are in a kitchen, a living room, a dining room, a bathroom, all the same thing… So when we shoot at U of T, I know it’s gonna be cool.”

But much like the obstacles faced by our favourite movie characters, filming at U of T doesn’t come without challenges.

U of T enforces strict rules about what studios can and can’t show, and urges productions to maintain the university’s anonymity while filming. Sevilla said that crews make an effort to leave locations in good shape, partly because they don’t want the university to ban them from shooting here in the future.

U of T tends to limit filming to weekends, reading weeks, or the summer. Sevilla noted that, in Toronto, most filming takes place during the summer and spring anyway since producers often prefer to avoid dealing with harsh weather.

Filming in Toronto also creates job opportunities for students looking to appear as extras, also known as background actors. In 2021, Toronto’s film industry employed approximately 35,000 people. However, film crews don’t just pick up students off the street — background actors must be approved, sign releases, and get fitted to ensure their wardrobe matches the setting.

Felicitas Damiano, who recently completed her masters of teaching in dramatic arts and social sciences at U of T, along with her part-

ner Jake Pereira — a fifth-year student studying drama, political science, and Spanish — have frequently worked as background actors. This includes spending eight days at St. Michael’s College shooting scenes for a TV series remake of the 1999 film Cruel Intentions

Damiano told The Varsity that becoming a background actor had interested her for years, but she didn’t see an opportunity to break into the business growing up in Barrie, Ontario. “When I started at U of T… I was like, okay, now I’m living in Toronto. They actually do a lot of filming here. This could actually be possible,” she said.

Ulis Bertin, a third-year student studying English and European affairs, worked as a background actor on Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, which Netflix plans to release in 2025.

“They told me not to cut my beard because they were going for a very specific look,” Bertin said. He worked three days in total, putting in 14hour days and earning $16.55 an hour.

“It gives you experience [and] it shows you know the film world,” Bertin said. “More than anything for aspiring actors, it’s a good source of money, because it requires almost zero preparation and yields pretty good, long hours.”

Pereira noted that he earned about $1,000 on the set of Umbrella Academy. However, he explained that, although non-unionized background performers earn minimum wage, unionized performers — with either a drama degree, spoken lines, or who have worked 1,600 hours or 200 days as background actors — receive at least $31.75 per hour, along with travel and overtime bonuses.

Acting in films shot on campus has its perks, with Pereira noting that, “It’s just cool to see the university… become something completely different.”

But that doesn’t mean the work can’t be hard. Damiano told The Varsity that, despite Cruel Intentions being set in the summer, they filmed scenes in December. “So we were in shorts and T shirts outside in negative two degrees,” he said. “The moment they [said] cut, all the makeup people and wardrobe people would come running with sleeping bags.”

Bertin’s advice to students? Apply as a background actor. “It’s a shitty job, but it’s one of the greatest shitty jobs,” Bertin said. “I made many friends, people who I could never have met studying at U of T.”

Britt Rolston, a fourth-year arts management student at UTSC, has worked as a scanning representative at TIFF for three years, ensuring that ticket holders are admitted into viewings. She is employed specifically for the two weeks of the festival, usually working 5–6 hour shifts, and is just as enthusiastic about working at TIFF. “I loved it… It’s nice to have this experience,” she said.

TIFF offers vouchers to its workers every year for watching films, gaining early access to ticket selection, and receiving discounts for the CN Tower and Ripley’s Aquarium. However, working at TIFF has its drawbacks.

Rolston explains, “You get the odd person who’s like ‘Do you know who I am’?” While the entertainment industry can sometimes involve

Front-of-house employees, box office workers, and facilities attendants at the TIFF Bell Lightbox — the permanent cultural centre at the heart of the annual festival — are covered by the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees Local B-173 union agreement. This agreement serves as the bargaining agent for all facilities attendants at the Lightbox. According to Light, almost nobody working at TIFF is under a union, which he said is

These festivals often scale up massively for short, one-time events, which requires a flexible workforce. Due to the nature of

With the Hollywood strikes affecting 2023’s turnout, TIFF decided to reduce its full-time staff by 12 positions. TIFF’s vice-president of public relations and communications, Judy Lung, claimed in a statement that the after-effects of the pandemic lockdowns and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists’ strikes necessitated measures to “optimize our yearround and festival operations.”

Despite the challenges, part-time annual workers and U of T alumni find a unique appeal in their TIFF experience. Light noted that some volunteers have been returning for 30 years. “It feels like a summer camp reunion every September for hundreds of us. It’s a very special kind of community and I am so glad to be experiencing it from my position,” he said.

September 17, 2024

thevarsity.ca/cateogory/opinion

opinion@thevarsity.ca

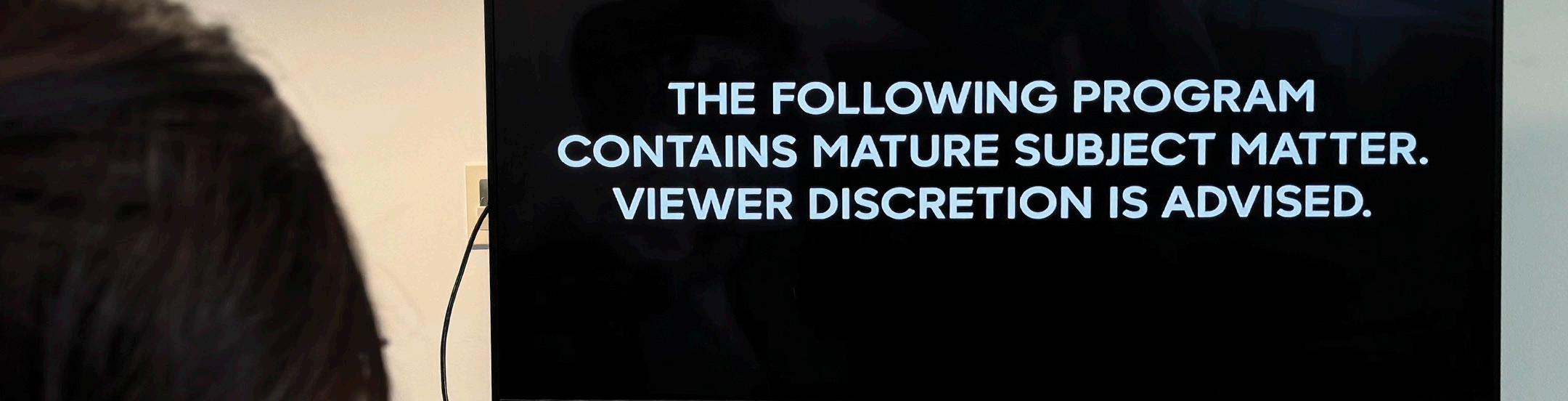

Trigger warnings are a necessary addition to modern media These warnings in film are meant to empower viewers, not censor creators

Leah Cromarty Varsity Contributor

Content warning: This article discusses domestic violence, sexual violence, and self-harm.

The debate about whether to put trigger warnings at the beginning of films is nothing new. However, the discussions have lately resurfaced with the promotion of It Ends With Us, a film adaptation of Colleen Hoover’s bestselling young adult novel of the same name. With themes of domestic violence and emotional abuse at the film’s core, fans were divided over the necessity of warning audiences about these sensitive topics.

One side of the trigger warning discourse claims that trigger warnings could diminish a film’s emotional impact, while the other argues that providing context empowers viewers to make informed decisions about engaging with emotionally difficult material.

Far from stifling creativity or coddling viewers, I believe that trigger warnings enable audiences to confront difficult content on their own terms and allow filmmakers to promote compassion and inclusivity without compromising the creative process. By offering advanced notice, trigger warnings foster an environment of consideration and empathy, allowing audiences to make informed decisions about what they watch.

Purpose and criticisms of trigger warnings Trigger warnings serve a straightforward but important purpose: to inform audiences of potentially distressing content. These warnings typically precede films that engage with sensitive topics like sexual violence, domestic abuse, or self-harm. The warnings help ensure viewers are mentally and emotionally prepared for the content ahead.

However, some argue that trigger warnings ‘coddle’ individuals by encouraging them to avoid uncomfortable content.

These critics, such as journalist Greg Lukianoff and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, believe trigger warnings promote a society where we would be left unchallenged and avoidant of difficult emotions or ideas that are essential to personal growth. For instance, if one attempts to avoid distressing content related to war, they may be limiting their historical knowledge.

Yet, the individuals who advocate for trigger warnings are usually those who have experienced traumatic events of abuse and violence and, therefore, already have a deep understanding of the material they wish to see warnings for. They will not lose much insight by choosing not to engage in the related content because they already know it first-hand.

Moreover, the argument that trigger warnings lead to avoidant behaviour is unsupported. For example, a 2023 study published by American healthcare academic publication Springer showed that most viewers still choose to engage with possibly triggering material even after being forewarned. This, to me, demonstrates that trigger warnings do not promote avoidance but simply provide viewers the ability to choose the material they watch.

Additionally, I don’t believe that the filmmaker decides whether to dictate whether viewers must

confront difficult material or not. In fact, I believe the filmmaker has a responsibility to inform individuals about potentially distressing content.

Forced exposure to distressing material can be harmful for survivors of trauma. Exposure to stimuli that remind survivors of their traumatic experiences can be detrimental, as the appropriate healing processes vary from person to person.

Finally, the perception that trigger warnings stifle creativity is similarly misguided. From my experience, informative warnings neither spoil the narrative nor detract from its emotional impact when executed correctly. Netflix’s short lists of distressing themes on the introductory pages of their films and shows are great examples of effective and subtle trigger warnings. Offering information this way does not spoil the story, but keeps audiences informed.

The issues with psychological studies

Critics of trigger warnings often cite psychological studies that suggest that trigger warnings have little or even adverse effects on viewers’ stress levels. However, these studies have significant limitations. Some studies, for example, rely on random participant samples rather than focusing on trauma survivors or those with post-traumatic stress disorder: individuals who would benefit the most from trigger warnings.

Furthermore, I think we must question how applicable laboratory experiments are when

Goc

Atinc

Varsity Contributor

Recently, I caught myself doing something interesting when I went to the cinema. As soon as the credits rolled, without even leaving my seat, I instinctively reached for my phone and opened Letterboxd to log the film I just watched. I wanted to make sure I’ve documented the experience, checked the box, and moved one step closer to ‘beating’ the number of movies I watched last year.

Not too long ago, it would’ve probably been unthinkable to review every film we saw or know exactly how many films we watched each year. Today, Letterboxd has fundamentally changed the way we engage with movies, transforming the formerly private experience of moviewatching into a collective, social activity.

Letterboxd isn’t just a platform for film logging — it gamifies the entire movie-watching experience. You write reviews and people can like or reply to them. You make a watchlist and people follow it. It’s non-stop dopamine for film lovers.

It’s a community, a game, and in some ways, an integral part of how we consume and critique films today.

Rise of the Letterboxd

Developed by Matt Buchanan and Karl von Randow in 2011, Letterboxd aimed to create a fun and engaging tool for film lovers. IMDb is a longstanding comprehensive database for film information while Rotten Tomatoes aggregates critics’ and audience ratings. Letterboxd, however, focuses on social interactive experiences where users can write reviews, follow each other, and

engage in film discussion: much more like social media. Anyone can make an account and start reviewing films on Letterboxd.

In 2024, Letterboxd had over 14 million users, which skyrocketed from 1.8 million in 2020. Even as its user base expands, Letterboxd’s age demographics have stayed relatively concentrated around young people. According to software analyst platform YouScan’s audience insights, around half of all active users are under 35, with the majority being between 16 and 24 years old.

Social intelligence researcher Ben Ellis argues that the platform’s effective use of other social media helped fuel its popularity. Letterboxd produces YouTube content, such as filmography breakdowns with actors, while posting short videos from film festivals on Instagram and TikTok. Red carpet interviews about celebrities’ top four Letterboxd movie picks have also trended online.

Many apps today like Duolingo and dating platforms utilize gamification to boost user engagement, adding features such as challenges and rewards to keep users on the platform. While I believe this adds a fun, competitive element to the movie-watching experience, I can also see its negative aspects.

Users may feel pressured to watch or finish movies they don’t enjoy just so they can log them. Letterboxd turns the movie experience into a competition, compelling users to watch more films and write exaggerated reviews to stand out and gain likes: diluting the fun of genuine film appreciation.

I think the app can also force people to manufacture a false sense of identity. For example, some of my friends worry that others will criticize their favourite movies. Some people may also not log their

translated to classrooms or cinemas. A 2023 study from Current Psychology argued that trigger warnings can worsen anxiety by preparing people to anticipate stress, concluding that trigger warnings have negligible benefits. However, the study tried to prove its theory by using a trigger warning on participants that simply read, “Researchers have been asked to give a trigger warning for the clip” before playing them the visual content.

Without any specificity of the disturbing material, the warning’s vagueness may have reasonably induced the participants’ anxiety because they did not know exactly what the researchers were warning them of. In reality, however, the effectiveness of a trigger warning depends on its tactful, precise, and sensitive execution — which I feel is difficult to fully replicate in a laboratory setting.

The power of choice

Whether or not trigger warnings truly reduce anxiety is not what matters the most to me — what matters is that viewers deserve to be informed of.

In the same way that photosensitive warnings protect those with epilepsy, I believe trigger warnings safeguard mental well-being. Many survivors of traumatic events often rely on the warnings to comfortably approach new films. Dismissing or devaluing the importance of these warnings only reinforces the dangerous notion that human mental well-being is secondary to artistic vision.

Trigger warnings represent a simple act of empathy. They are not a burden on creators, but a tool that invites more people into the conversation. Ultimately, I think trigger warnings uphold both artistic integrity and the audience’s autonomy, enriching the viewing experience for all.

Leah Cromarty is a fourth-year student at University College studying English, philosophy, and history.

guilty pleasure movies because it does not fit their ‘Letterboxd identity.’

In spite of all this, Letterboxd reignited my desire for cinema. Everyday, I log in to see what my friends recently watched, add their recommendations to my impossibly long watch-list, and get the intense desire to watch the most average film that they wrote “WAS THE BEST PIECE OF ART I HAVE EVER WITNESSED IN MY ENTIRE LIFE.”

Changing the way we watch movies

Letterboxd has built a community of film enthusiasts, making it easier for viewers to access film recommendations and curated lists. I think this helps increase young peoples’ interest in classic films, as less than 24 per cent of the films logged on Letterboxd between January 2023 and April 2024 were current-year releases.

In my experience, I’ve noticed a similar rising interest in classic films among the younger generation. When I attend screenings of classic films at Toronto International Film Festival Cinematheque, a year-round program featuring a curation of classic films, I’ve noticed that the audience is predominantly made up of young people. However, this increased interest in movies is not limited to the classics.

A study conducted by international market research company Kantar examined the movie-going habits of 15–30 year olds in France and found that this age group particularly values the experience of watching films on the big screen as well

as using the cinema to socialize with friends. I see a strong correlation here: as the younger generations’ interest in cinema increases, Letterboxd provides them the tool to share their experiences. This way, film lovers can socialize at theaters but also continue their love for cinema online.

Letterboxd critics

You could argue that Letterboxd is undermining traditional film criticism by allowing everyone to review films — but I disagree.

While I enjoy reading Letterboxd reviews for fresh perspectives on films, I still turn to professional critics for deeper analysis. It’s my belief that rather than harming the film criticism industry, Letterboxd is carving out its own niche of light-hearted and humourous film reviews. The most creative and succinct review I’ve read recently was from a friend on Letterboxd, seemingly addressing the director of a film: “Don’t shoot a movie again.”

Letterboxd has quickly become one of my favourite apps. As a film lover, it fills a void the younger generation has long needed: a place to not only log what we watch, but to have conversations, discover new films, and connect with others who share the same passion. Honestly, I can’t wait to finish writing this article so I can get back to watching a movie and logging it right away.

Atinc Goc is a fourth-year student at UTSC studying psychology and sociology.

September 17, 2024

thevarsity.ca/category/science science@thevarsity.ca

JI LN LAM/THE VARSITY

understand the relationships between different objects in an image.

The letters ‘AI,’ are only a measly two syllables, yet become bundled with a bevy of trepidations and an equal amount of hype. It has made diagnosticians and even prophets out of researchers. Helping us separate the artificial from the intelligence was Ray Perrault of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Perrault spoke about the Stanford AI Index Report on the last day of the Absolutely Interdisciplinary conference on May 8. Coming in at just over 500 pages, the Stanford AI Index Report is a behemoth that documents the recent trends in AI. The Stanford Institute’s mission is to produce research that is rigorously vetted, broadly sourced and quantitative. People talk, but numbers talk louder.

The report was put together in 2023 and published on April 15. Given how fast AI develops, maybe my human eyes prevented me from catching some developments since then. So, when you’re reading this, if you find yourself thinking that surely the figures must’ve changed, I encourage you to find out. Now that we have our bearings, here are the key insights from the report that Perrault discussed.

AI performance on benchmarks

To measure the technical capabilities of an AI model, researchers have come up with clever benchmarks that are essentially pop quizzes for AI. Researchers grade the performance of AI models on these different benchmarks.

While it is true that AI outperforms humans on many benchmarks, it is still lagging on others, like competition-level mathematics or visual common sense reasoning. ‘Visual common sense reasoning’ refers to the ability to

Perrault explained that researchers introduce a benchmark and, after a couple of years, AI models catch up to human performance on that benchmark: their progress reaches saturation. Therefore, researchers are always coming up with new benchmarks and testing new capabilities of AI. So the Sisyphean struggle of AI development carries on.

Previously, AI could only answer prompts in one medium at a time — through text or image. As new benchmarks have shown, AI can process different mediums simultaneously.

The researchers tested this through multiple choice questions in different subjects involving both text and diagrams. The performance of humans on this test was around 80 per cent on average while the best AI models give correct answers around 60 per cent of the time. The models are ahead in some benchmarks and are slowly catching up in others.

Corporate investment in

Corporate investment in every industry has been shrinking since 2021, so investment in AI has been naturally shrinking too. However, the percentage investment in generative AI compared to other types of AI has been on the rise. The common public sentiment against AI can be distilled into one pressing question: “Is AI going to steal my job?”

Is AI the bullet in the chamber that kills job security? Perrault weighed in.

A report from consulting firm McKinsey & Company has found that while businesses’ AI adoption shot up from 2017 to 2019, it has remained stable since then. Despite all the attention that ChatGPT and other AI models garnered, behind the smoke and the mirrors, these industries didn’t immediately translate

“

The news is not all bleak though, as the number of open or publicly available AI models are growing. These models are made to be transparent: you can pry them open, see the inner workings, and tweak them.

”

to workflow changes. Of course, the incentive to use AI in the workforce is very much still present. The report reveals that adopting AI in businesses can reduce costs and boost revenue.

But, for now, AI is not going to take your job.

For those weary of the monopoly in the AI industry, there’s dire news: most large tech companies have monopolies in emerging AI

technology. Google is producing the largest number of AI models, with 40 models since 2019. Most AI models are coming from private companies and not from academic campuses. The private technology companies developing AI are also low on transparency and developing the frontier models of new AI is getting more expensive — with the largest ones costing well over 100 million USD.

The news is not all bleak though, as the number of open or publicly available AI models are growing. These models are made to be transparent: you can pry them open, see the inner workings, and tweak them. Open models allow other developers to learn and build on what already exists. However, the fact remains that closed models like those from private companies often outperform open models.

Governments are starting to heed the warnings that dystopian writers have been spouting for decades. We’re thankfully still far removed from the scorched-earth, post-apocalyptic world of Terminator , but the rapid march of AI development has raised eyebrows. Policymakers have identified a need to regulate AI to allow our infrastructure to catch up to it. In 2023, the US proposed 181 bills which aimed to regulate AI and most of the proposed regulations have been about constraining rather than expanding the use of AI.

AI continues to develop at the speed of a jet-plane and we are left watching the contrails behind. The Stanford AI Index Report gives us a peek into the direction we’re headed. With government policies, corporate investment, and human skepticism nudging the future of AI, Perrault’s report demystified some of these forces and prepared us as we wait for the contrails to dissipate into the atmosphere of our society. Hopefully, now we are a little more ready for an impending sonic boom.

September 17, 2024

thevarsity.ca/category/science science@thevarsity.ca

Why this visionary novel remains an essential read for fans of science, history, and speculative fiction

Razia Saleh UTM Bureau Chief

If you’re a STEM student or simply fascinated by human history’s vast complexities, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation will satisfy your reading needs. Asimov was a Russian-American biochemist turned novelist who became one of science fiction’s ‘greats’. He crafted a narrative that intertwines the scientific principles of his time with the vast history of a possible future where humanity’s destruction looms over future development. Foundation is the first novel of Asimov’s

“The Traders”, and “The Merchant Princes.” Foundation introduces the reader to the concept of psychohistory, where the world of fictional science merges with the fields of mathematics and sociology, predicting the futures of human populations. According to Asimov, psychohistory is a mathematical method that “deals with the reactions of human conglomerates to fixed social and economic stimuli.” The main character, Hari Seldon, uses psychohistory to predict human behaviour. Seldon has a vision that twelve thousand years into the Galactic Empire Supreme, the world will die. From here began the collection of all human knowledge —

Set on the planet Terminus, “The Mayors” explores the Foundation era, when the brilliant first mayor Salvor Hardin governed Terminus City. The Foundation ousted the Encyclopedists, a political party focused on only academic pursuits, becoming the dominant party in the political arena of the empire. Hardin uses nuclear energy to control the city, sustain its growth, and avoid control from other planets. In the novel, nuclear power is the main technological advancement in the world, symbolizing the weaponry nuclear power exhibits. This leads to warfare and an obsession for power — causing many of the worlds to regress from the technological advancements the empire has placed on the earth.

Since Asimov’s novel was published in 1951,

technology was not as advanced as today’s use of AI technology. Nuclear power was believed to be the power that provides infinite energy.

“The Traders” focuses on Limmar Ponyets, a shrewd trader who is responsible for influencing the sale of Foundation-controlled nuclear technology to other worlds. Ponyets rescues Foundation agent Eskel Gorov, who fails in attempting to introduce nuclear technology to worlds outside of the empire. Due to his actions on the planet Askone, Gorov is imprisoned until Ponyets rescues him and eventually gets the leader of Askone to accept the Foundation’s technology by disguising it as a religious artifact.

“The Merchant Princes,” the first novel’s final chapter, introduces Hober Mallow, another master trader who tries to find if there are technological remnants in the Galactic Empire. He finds that the Empire’s economy is weakening, but he uses this knowledge to take the power of the Foundation’s trade business to become the first ‘Merchant Prince,’ a key power contributor alongside Seldon and Hardin. Ultimately, the world sees a shift from the scientific control of power to a more political force.

I spent the summer mesmerized by Asimov’s fictional world, which pulled me into an addicting universe mirroring our world’s struggles but with a twist of adventure and ethical dilemmas. It kept me on my toes with characters that I am sure you will eventually be invested in as you start on this seven-book series.

Asimov’s twists are unexpected. One thing that can be boring about science fiction is the constant need to include galactic battles like Star Wars to please the audience, but it does not add any depth to the storyline. Asimov

Scroll, swipe, repeat: How social media is rewiring our attention span

The digital age dilemma of why we struggle to stay focused amid distraction

Asmi Khanna Varsity Contributor

As students head back to school this fall, their aspirations soar are strong and their dreams grow. Yet, there’s one dreadful distraction we can’t seem to outwit: the buzz, beeps, and dings of notifications tugging at the pocket of our pants. “It’ll just take a few seconds,” we say as we grab our phones. But those seconds often turn into minutes and hours as we jump from app to app, trapped in an endless and alltoo-familiar cycle of struggling to return to work.

Social media platforms, such as TikTok or Instagram, use algorithms that condition our brains to crave quick bursts of content — shortening our attention span and making it easier for us to watch an hour’s worth of reels than to sit through a one-hour lecture. On our phones, when something bores us, we can simply scroll away. In real life, that option doesn’t exist.

The constant stream of algorithm-driven content makes it increasingly challenging for students to stay focused. A 2018 Pew Research Center survey found that 31 per cent of teenagers in the US lost focus in class due to cell phone use. Additionally, while doing homework, 51 per cent of teenagers watch TV, 50 per cent use social media, 76 per cent listen to music, and 60 per cent send text messages.

How are attention spans changing?

The growing social media addiction is fuelling a worldwide decline in attention spans. In an interview with the American Psychological Association, Gloria Mark, a psychologist and chancellor’s professor of Informatics at the

University of California, Irvine, shared alarming statistics from her study on global attention spans.

Mark noted that the average global attention span in 2004 was 2.5 minutes, which dropped to 75 seconds by 2012, and has since decreased to 47 seconds over the past 5–6 years. However, attention spans are not uniform. According to Mark, they consist of both focused attention and rote activity, which is repeated actions with little required thinking.

In focused attention, individuals are actively and consciously engaged in a task, such as reading a complex article. In contrast, rote activities involve tasks that are less challenging, like playing video games or scrolling through social media, which ac counts for most screen time.

A shrinking attention span causes people to switch their focus between tasks more frequently. Mark hypothesized that attention switching would potentially increase stress levels, as measured by elevated blood pressure, and increase the likeli hood of making errors while completing tasks. Mark’s correlation study revealed that constant attention shifting due to compromised attention spans led participants to make more errors, require more time, and experience greater stress.

Remedying the attention span: Importance of balance, visualization, and our environments

While excessive attention switching can be detrimental to mental performance and stress levels, a balanced combination of focused tasks and rote activities can replenish energy, prevent burnout, and enhance attentional capacity.

For example, scheduling breaks after paragraphs while writing long and tedious essays may help ideas flow

better, reduce stress, and maximize efficiency.

Balancing focus and breaks is essential — especially in a technology-driven world where managing distractions is crucial for productivity. By understanding how to use breaks effectively and recognizing triggers for losing focus, we can better integrate technology into our lives while maintaining productivity and well-being.

In an interview with CBS News, Mark recommends exploring the reasons behind our loss of focus. By isolating the causes of distractions,

takes the approach to science fiction with a bigger perspective, answering the big questions of today’s society without the extravagant big battles in space.

The book is not just a work of fiction, but a mirror reflecting the relevance of science in shaping our future. It explores the role of science in shaping future human civilizations, preserving the knowledge we’ve acquired from past to present, and the nature of history’s repeated nature. The Foundation’s technological superiority allows the community and nearby worlds outside the Galactic Empire to become dependent on the Foundation.

Some may say the story resembles Frank Herbert’s Dune, but some believe that Asimov’s work inspired Dune. However, the two stories and their purposes are entirely different. Asimov gives the reader a vision of what scientific insights may do to change an entire civilization’s fate in the long term, especially in a society where data and statistical models play an increasing role in how the world works.

What makes Foundation an exciting read for adventure and novel scientific fiction enthusiasts alike is the love for introspection, challenging us to understand the power and limitations of science. By inviting readers to reflect on the forces that drive societal change, we know the importance of safeguarding humanity’s knowledge. Whether you’re a STEM or humanities student, Asimov’s classic tale will leave you pondering on humankind’s future and initiating controversial conversations about it. For U of T students looking to expand their horizons into the field of science and speculative fiction, Foundation is an essential complement to your reading list.

people have shorter attention spans. It’s the environment we live in. It’s the phones.”

Ultimately, improving your attention span is achievable by ensuring adequate sleep, taking regular breaks, and spending time outdoors. Sleep is a crucial component of attention, as it directly affects your ability to stay focused. Quality sleep is best achieved in a quiet, dark, and comfortably cool environment. Avoiding caffeine and late-night naps also promotes brain health.

Reclaiming control over our attention is no longer just about resisting distractions — it’s about reshaping the activities and environments we engage in. The key is not to vilify the tools that distract us, but to use them with intention. So, the next time a notification tempts you to scroll, remember this: every moment you take to pause and refocus is a victory for your attention. Your attention, after all, is a valuable resource. Guard it

representation and reality…] can lead to diminished empathy and understanding among audiences. The absence of realistic representation also impacts the visibility and participation of disabled actors and creators in any film industry.”

harmful

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide.

When I was undergoing treatment for leukemia, I couldn’t bear to watch a single movie. Sitting on my hospital bed, my laptop was always tightly closed and stored away on the other side of the room. Instead, I spent time with my sister in relaxing games of Scrabble.

My reluctance to watch movies wasn’t because movies are a waste of time, nor was I against watching a good film in general — it was because of what the movies were often about and how they affected me. Imagine coming back to your small, empty hospital room after finishing a round of chemotherapy. You’re emotionally and physically drained, only craving a simple distraction. You open Netflix, but all you see is movie after movie that uses cancer as an ingredient to spice up its plot.

Yeah. Not a good feeling.

The characters in these movies either pass away from their condition, fall hopelessly in love to make the character’s condition seem all the more tragic, or do both: fall in love and then die. As someone who has lived through the conditions that these movies so offhandedly abuse, these carelessly reductive movies cannot entertain me.

After successfully beating cancer, I am now a proud survivor. Still, I don’t want to see these kinds of films anytime soon or ever again. When the credits roll, I’m left with a bitter taste in my mouth and a single thought swirling in my head: “The main character had cancer, and she lost the battle. What if that was me?”

Approximately one in six people in the world live with a disability, so it’s safe to imagine that many others would be as irked as I am when they see their own experience exploited for cinematic entertainment.

A disparity between representation and reality

Torontonians like myself know that the city always gears up for the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). The 11-day festival includes movies of all genres, produced by companies from all over the world — including the exact movies that I avoided when I was undergoing treatment.

TIFF is not shy about showcasing movies depicting characters with physical illnesses or disabilities: the film Miss You Already, for example, premiered at TIFF in 2015. This dramatic romantic comedy follows the struggles of Jess and Milly, who are childhood friends. While Jess is trying to have a baby, Milly is diagnosed with breast cancer. The diagnosis sends shocks into Milly’s world and she goes through a form of cancer treatment: chemotherapy.

But that’s where things go wrong.

Although Milly experiences a relatable whirlwind of emotions of sadness, frustration, and rage, her way of living and acting as a cancer patient undergoing treatment is overly dramatized to the point where it is difficult to connect with her — even as a former cancer patient myself. Milly becomes as impulsive as a rebellious teenager: she gets drunk day and night and repeatedly cheats on her supportive husband, the father of her children.

Movie characters with cancer like Milly who are depicted as reckless and single-minded perpetuate a disparity between representation and real life, alienating the audience living with a physical illness or disability. Miss You Already uses a cancer diagnosis as a tool to instigate one big adventure for a character rather than to accurately tell the story of a cancer patient. But this isn’t unique to Miss You Already, as many storytellers in the film industry seem to prefer to exploit an experience for dramatic effect and entertainment over valuable representation.

Assistant Professor Chavon Niles at the Department of Physical Therapy in the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, who researched critical disability studies, shares a similar sentiment as mine about cultural misrepresentations of disability. In an email to The Varsity, she explained, “When the media predominantly portrays disability through a negative or limited lens, people with disabilities may feel that their experiences are misunderstood or devalued by society, leading to feelings of isolation and disconnection from social life.”

“This isolation,” continued Niles, “is further compounded by the fact that many fictional stories and visual media fail to represent the structural barriers and discrimination that people with disabilities face daily.” Instead of exploring the complexities of life with a physical illness or disability, Niles argued that many films accentuate

the character’s tragedy by showcasing their bad decisions and fatal endings.

Milly does not experience any character development in Miss You Already, staying entirely onedimensional from beginning to end. She receives her cancer diagnosis early on in the movie, and the rest of the plot simply relies on her diagnosis to shape her as a character. Milly’s story is told from a negative lens because it subjects a cancer patient’s experience to a string of terrible decisions and a tragic ending: death. Miss You Already sends a message that cancer patients are defined by their diagnosis and that all the decisions they make and the actions they take in their lives are an extension of their illness — right up to their untimely death.

Another film that misrepresents life with a physical illness is Blackbird, which premiered at TIFF in 2019. Blackbird is your typical family drama. The mother, Lily, is going through a hard battle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a terminal disease that affects the nervous system. She brings three generations of her family together one last time before taking her own life.

In the final family gathering, the audience witnesses an explosion of family secrets that have been simmering for quite a while. From Lily disclosing that she encouraged her husband to enter a romantic relationship with their family friend to Lily’s daughter revealing that she has been suicidal and admitted to a psychiatric hospital, problems surface and arguments erupt with the trigger being the nearing end of Lily’s life.

While tensions and stress levels can arise when a loved one is about to take their last breath, the dramatic family gathering and exaggerated subplots for cinematic entertainment distract from exploring the emotional experience of a character battling with ALS. By the end of the movie, audiences will remain ignorant about the reality of ALS and how it impacts a person, with little attention paid to depicting how Lily felt or how her illness impacted her.

Assistant Professor of cinema studies Rakesh Sengupta elaborated on the disparity between representation and reality in an email interview with The Varsity. He said, “I feel this [disparity between

Poor cinematic representation for entertainment’s sake does more harm than good, especially to young audience members like myself who deal with or have dealt with a physical illness or disability. Blackbird, for example, barely touches on an ALS experience, making it practically invisible under all the extravagant family drama and reducing the illness to the start of a tragic ending. This shows how representation can ironically endorse invisibility if done improperly.

“We must remember that young audiences are in a critical stage of identity formation and are particularly susceptible to the messages they receive from [the] media,” wrote Sengupta.

After watching Miss You Already and Blackbird I remember the grand escapades and the dramatic family secrets so much more than the actual diagnoses in the stories. This sends the message that the experience of someone with cancer or ALS is not worth exploration and is rather a way to embellish the story.

Romanticization with consequences

When making a movie about people with physical illnesses or disabilities, storytellers take on the responsibility of accurately representing the affected people and their experiences. However, instead of drawing from the richness of real life, they take the easy route of combining a tragic love story with a tear-jerking ending for more viewership. The result is toxic romanticization.

Me Before You fect example of a book and film that captured the audience’s hearts and brought even hard-hearted people to tears. This movie takes the romanticization of a disability to another level and then ends in blunt pessimism.

The movie follows Will — who became both quadriplegic and pessimistic from an accident two years ago — and his new and quirky caregiver, Lou. The more Will spends time with Lou, the more

her optimism rubs off on him. They end up falling in love — no shock there — but ultimately, love cannot save Will. He still chooses to die, believing he cannot live a fulfilling life while paralyzed.

Not only does Me Before You portray the life and death of a person struggling to reconcile with his quadriplegia through a romantic lens, but it also sends a dangerously fatalistic message about living with a disability.

Niles also addressed the dismal effect Me Before You can have on young adults: “[The] narrative… where the disabled character’s life is depicted as not worth living… sends a harmful message that can deeply influence how young adults with physical disabilities perceive their own value and potential.”

Despite surviving a motorbike accident and falling deeply in love, Will decides that life with a physical disability is not worth living. I see this compelling audience member with similar disabilities toward hopelessness and thoughts of self-doubt: “Is my life worth living?”

“This internalization can lead [young adults with disabilities] to a lack of self-confidence, social withdrawal, and a reluctance to pursue ambitions or advocate for their rights, perpetuating a cycle of marginalization and disempowerment,” Niles wrote.

Movies for teens also shamelessly use physical illness and disability to amplify the emotional impact of their romantic plots. The teen flick Five Feet Apart follows Stella and Will, who are both diagnosed with cystic fibrosis — a genetic disorder that damages the lungs — and must keep a good distance from each other to avoid spreading harmful bacteria between them. Unsurprisingly, they develop an instant romantic connection and proceed to do exactly what they shouldn’t if Stella and Will are patients at the same hospital, but despite being under the care of nurses and doctors, they manage to leave and go on rebellious adventures together.

During one of their rebellious adventures, Stella falls through a frozen pond, and Will performs mouth-tomouth CPR, dramatically breaking the distance that their shared

illness requires them to maintain.

By the end of the movie, Stella finally receives her long-awaited lung transplant, but it’s unclear if Will is still alive since he is ineligible for a transplant. He confesses his love to Stella and vanishes forever.

Five Feet Apart uses cystic fibrosis to tug at the same heartstrings that quadriplegia does in Me Before You. The characters are reduced to their physical condition, with romance as the only thing that draws them out of it.

While I am an avid romance lover, using characters with physical illnesses or disabilities in love stories to provoke viewers to feel dispassionate. Stella only shows interest in being more than her illness when her love interest is by her side or after her best friend Poe passes away from cystic fibrosis. This suggests that people with a physical illness or disability need a big emotional event, like falling in love or experiencing loss, to live life to the fullest.

When the credits roll, I’m left with a bitter taste in my mouth and a single thought swirling in my head: “The main character had cancer, and she lost the battle — what if that was me?”

Ayala Sher, a second-year history and studio art student at UTSC with a non-visible physical condition, shared concerns about cinematic depictions of physical illnesses and disabilities.

“I really dislike when a disability is reduced to a plot device,” she said. “For example, someone’s mother might experience cancer, and that’s used to teach the character that life is important… that just feels quite disrespectful.”

Sher believes that romanticizing and misrepresenting an illness or disability in a movie can have harmful consequences. “I have quite mixed feelings because less accurate portrayals can be… frustrating at best and offensive and harmful at worst,” said Sher.

“At times, films can reduce the character to their disability, so that character might not have any traits outside of their disability.”

A call for better, more nuanced cinematic representation

Movies have social and cultural influence, and when they dramatize and romanticize physical illnesses and disabilities, they can reinforce barriers and discrimination.

As we live in an era of expanding

mass media and increasing film production, it is crucial to nurture better cinematic representation. Without better representation, more disabled people could be negatively impacted, especially given that the number of Canadians with disabilities increased by 4.7 per cent from 2017 to 2022.

Jheanelle Anderson, a research assistant at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, believes that the feelings of isolation and pessimism experienced by many people with disabilities are due to societal culture.

“I don’t think people with disabilities… isolate themselves from social life purposefully,” she said in an interview with The Varsity

With both apparent and non-apparent disabilities herself, Anderson knows firsthand how society imposes limitations on people with disabilities. “The environment itself is so inaccessible in multiple ways, whether it’s structures [or] attitudes.”

The cinema is one environment that endorses inaccessibility through flawed representation. As a result, real, living individuals may begin to see themselves in an equally flawed light.

However, some movies do successfully deliver genuine stories, and the TIFF film I Am: Celine Dion (2024) is one of them.

I Am: Celine Dion takes the audience on an epic journey through the “My Heart Will Go On” singer’s life and her experience with stiff-person syndrome: a rare neurological disease that causes stiffness and spasms. It highlights both the ups and downs of an individual battling an illness while juggling family life and a career as a singer. By opening up about her personal struggles and courageously including footage of herself experiencing an unexpected seizure while filming, Dion offers a raw, behind-the-scenes look at life with stiff-person syndrome.