Vol.

thevarsity.ca

thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity

the.varsity the.varsity The Varsity

Sarah Artemia Kronenfeld editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Caroline Bellamy creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Andrea Zhao managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Shernise Mohammed-Ali managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Mekhi Quarshie online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Ajeetha Vithiyananthan copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Kyla Cassandra Cortez deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Jessie Schwalb news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

Selia Sanchez deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Maeve Ellis assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Eleanor Yuneun Park comment@thevarsity.ca

Comment Editor

Georgia Kelly biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Alice Boyle features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Milena Pappalardo arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Salma Ragheb science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Kunal Dadlani sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Arthur Dennyson Hamdani design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Kaisa Kasekamp design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Zeynep Poyanli photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor

Jessica Lam illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration

Olya Fedossenko video@thevarsity.ca Video

Aaron Hong aaronh@thevarsity.ca

andrewh@thevarsity.ca

Kamilla

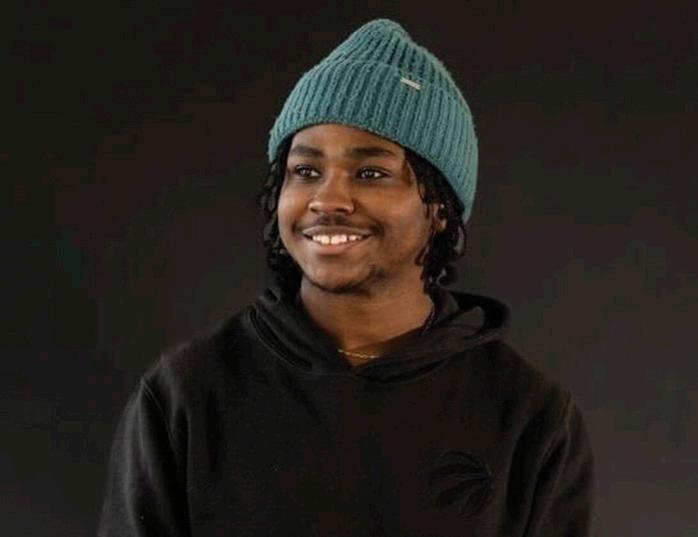

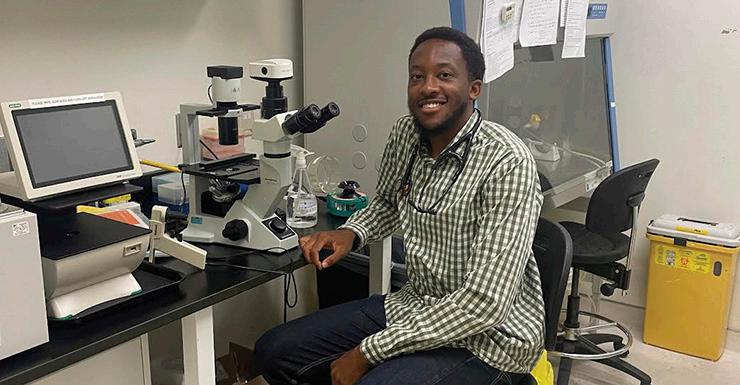

Cover Alexander Osodo :

Te Varsity would like to acknowledge that our ofce is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. Terefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

Alexander Osodo Varsity Contributor

Alexander Osodo Varsity Contributor

You must fnd a reason to fall in love with your art every time you approach your canvas. Devoid of this, the translation of thought to reality will reveal itself as an insurmountable wall. Must your work always have meaning to it beyond mere fascination? I personally don’t think so.

My afection for my art was reignited when it became a refection of my changing dialect with the world around me. I perceive it as an intimate relationship, one that is nurtured by wants and needs, susceptible to external pressures, but sharpened by a fervent dedication to reinterpreting your bride with the passage of time.

In the embryonic days of my voyage into the seas of creation, I adopted grandiose visions of what my art should be and do, visions that were desirable yet blinding. Ambitious strides toward veneration often met a festering frustration that gradually corroded my capacity to remain content with the present.

Overwhelmed and unfulflled, one day you may think, “Maybe I should give it all up.” Then you think, very quietly, “That path I crossed on my way from school would be a great spot to shoot at.” “The sky was just a bit more colourful today than it was yesterday.” “The alignment of trees

on this trail would make for a great composition.” “I wonder if person x would be down to shoot this weekend.” “Maybe I was overreacting.”

The present will begin to reveal to you that slowly but surely, your eye is becoming more keen. You are able to perceive detail better, colours and combinations more accurately, and your mind is able to more vividly compose

imaginary scenes that bring together assets strung across starkly diferent but surprisingly compatible outlets. All of a sudden, you can picture the vintage piece your friend once wore, complementing the aesthetic of that one graphic alleyway you often pass on your way to the mall.

In this process, you fnd yourself hungrier to experiment and bring ideas and people together. Following this, in a sense, your ambitions become a lot more momentary: I want to edit this photo, I want to create this design, I have this vision for how I can combine this and that. These short bursts of energy and inspiration become a lot more consistent, and much more centred on processes than outcomes. The world around you becomes a lot more romantic, and the atmosphere becomes one that naturally propels your mind towards worlds previously unimaginable scenes that you can’t wait to bring to through art.

As a Black creator, it is often easy to feel lost in the universe. More so, dedicating yourself to art and creation often comes at costs too high. I ask you to repeatedly fall in love again, and not tire of that sensation. Learn to interpret the fows of the world around you and to channel that into the evolution of your work. What goes too long unchanged often destroys itself.

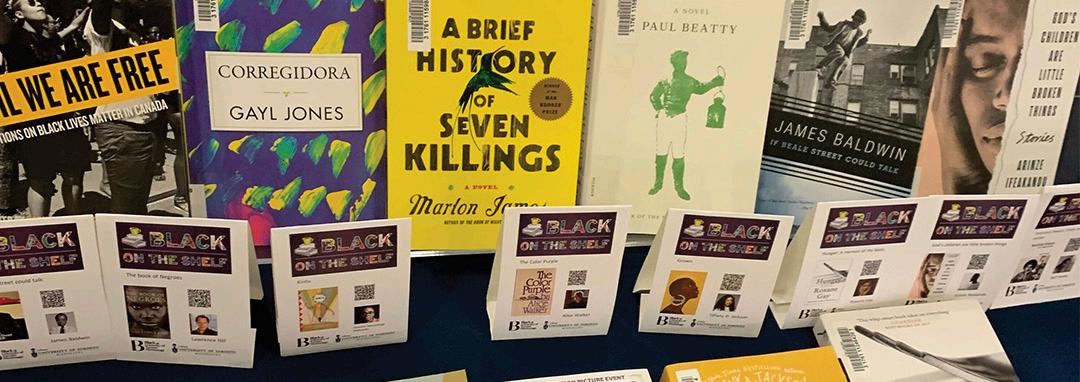

In 2020, The Varsity launched our frst Black History Month (BHM) issue. Josie Kao and Ibnul Chowdhury, our editorial management team at the time, designed it based on conversations they’d had with multiple Black campus organizations — conversations about how The Varsity has historically fallen short in its coverage of Black students’ issues and how we could improve this coverage for the future.

The BHM issue has become a regular part of our yearly schedule — but looking at our process this year, we’ve realized it now involves a lot less collaboration. That’s something we want to change.

We’ve struggled to achieve our goals of establishing clearer communications and longterm relationships with Black student groups on campus. We’re hoping to change this going forward by continuing to make this outreach a priority. We’ll be reaching out to Black student groups long after February ends and make sure we’re setting out the time to meet on a non-transactional basis.

The BHM issue has never meant to be the be-all and end-all to improving our coverage, either, and it’s certainly not supposed to be the only time in the year when we try to spotlight Black stories at the university. Instead, it’s meant as an opportunity for us to set specifc goals to better our coverage and to create space that’s especially welcoming for Black writers. In the same vein, over the rest of the volume, we’ll continue making sure we’re covering Black stories at the university. We want Black students to be a regular aspect of our weekly coverage as writers and as interviewees.

Over the last few years, we’ve settled into a routine around how we create the BHM issue. Most of our eforts centre around welcoming new writers: that’s why we reach out to the whole student body about the issue and break down the process of writing for The Varsity That’s also why we try to build longer timelines into our internal production process so we have more time to communicate with writers.

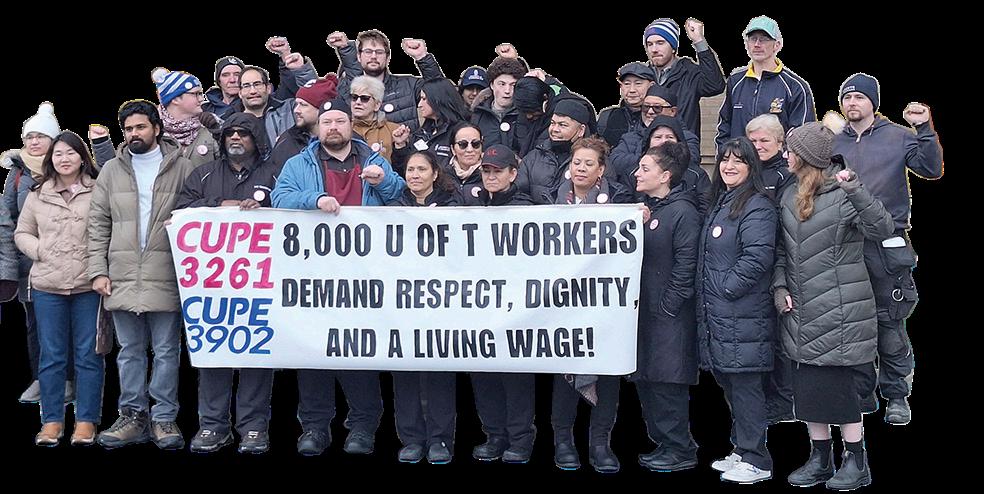

On top of that, we compensate Black writers for writing articles, taking pictures, or illustrating for this issue, to help combat the long history of undervaluing Black labour. Although we can’t compensate writers all year, and our honoraria are not very large, we still want to make this gap less egregious wherever possible.

This process is far from infallible — we have considerable room to improve, both in our BHM issue in particular and our coverage of Black U of T communities as a whole. We need to do a lot more to improve our

communication with Black students and communities on campus. We also still lack Black editors in masthead positions at The Varsity Ideally, we don’t just want to introduce new Black writers to The Varsity in this BHM issue: we want to make sure we create a space that encourages them to return.

Ultimately, one of the ways we can start to address all of this is to talk openly about what we’re working to change. That’s why we’re writing this letter — as a start, and to make these commitments public. This shouldn’t be the last you hear from us — this is a very basic commitment, and serves to show how many more conversations we need to have about Black representation in The Varsity . But it’s a start. And if you do have thoughts you want to share, our inboxes are open.

We’re looking forward to those conversations.

“Journalism is often called the voice of the people, but how can it be the voice of the people when [those] reporting and creating stories are not an accurate representation of our world?”

Writer and lawyer Hadiya Roderique posed this question to the crowd gathered on Zoom for a virtual roundtable held by U of T’s Department of History on February 9. At the event, Black historians and journalists discussed the underrepresentation of Black people in Canadian journalism and the importance of reporting that touches on a variety of stories relevant to Black experiences and communities.

A 2022 survey conducted by the Canadian Association of Journalists found that approximately eight in 10 Canadian newsrooms had no Black or Indigenous journalists on staf. Acknowledging the underrepresentation of Black people in journalism, Roderique said, “In the absence of an inclusive environment and the absence of hearing [Black] stories, the quality of journalism sufers.”

Cheryl Thompson, a researcher and associate professor of performance at Toronto Metropolitan University, discussed the importance of making space for Black lineage and knowledge in current journalism. She spoke about how her grandmother’s advice to “listen” has infuenced

her writing to refect her community’s needs.

Thompson said that, due to their underrepresentation in mainstream newsrooms, “[many] young Black people are hesitant to get into journalism.” Responding to this worry, she stressed that, rather than focusing on the reception their journalism might get, it’s more important for young Black writers to make sure they know their history and then “go out and do the thing.”

Freelance journalist Neil Armstrong told the crowd how his career in journalism gave him the opportunity to be an activist. Armstrong explained that growing up, he wrote letters to The Gleaner — a daily newspaper published in Jamaica — that discussed various matters afecting his community. This experience showed him that he “had a voice that could be used to amplify the issues afecting [his] family and friends locally,” beginning his interest in journalism.

Throughout his more than 20-year journalism career, Armstrong has continued to use his platform to advocate for Black Canadians, maintaining that “Black media should be a voice for the voiceless.” Armstrong highlighted the intersection of historians and journalists, telling the crowd that newspapers give historians insight into societies of the past, and, in conjunction, journalists use history to aid their understanding of current events.

Roderique expresses that Black pain and tragedy are exploited in the media. “Our joy is

rare because I think the mainstream media would rather focus on Black pain,” she said.

Multiple authors have discussed how social media and companies commercialize violence against Black people, specifcally police violence, such as by aligning themselves with the Black Lives Matter movement without taking

meaningful action. In a 2023 US survey, 63 per cent of Black people said that news they see about Black people tends to be more negative than that about other ethnic or racialized groups.

“We need to be seen as full people; with the joy and the pain,” Roderique concluded.

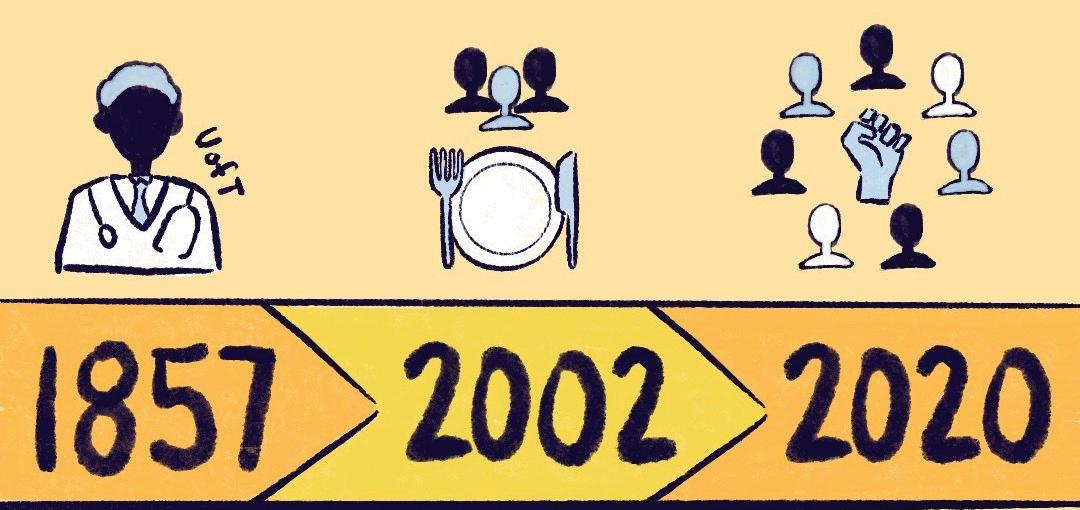

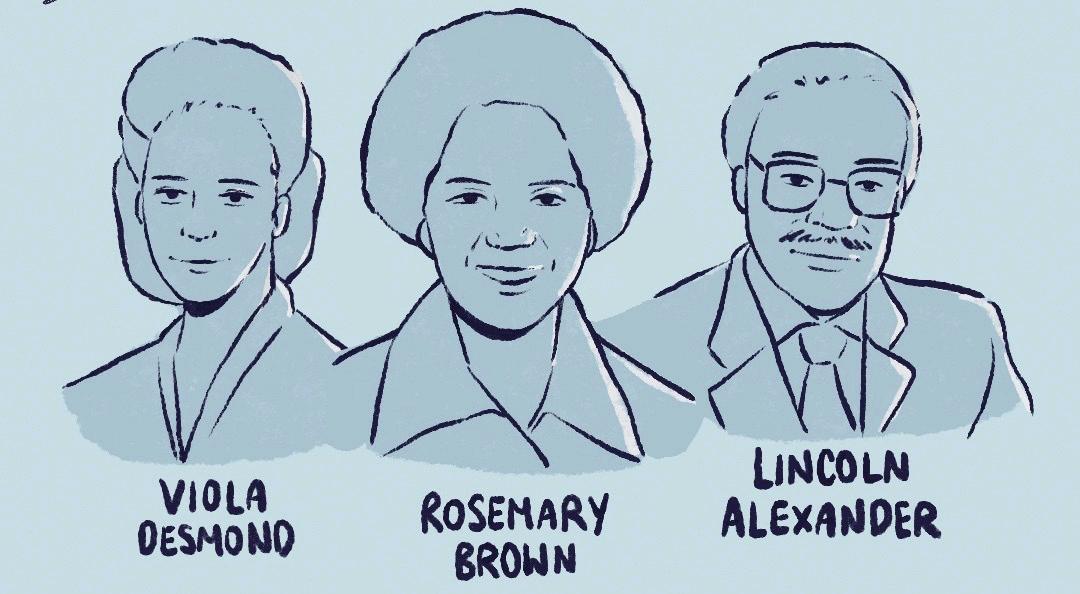

The frst Canadian-born Black doctor. A speech that charted the way toward school desegregation. A luncheon celebrating Black history. This Black History Month, The Varsity is here to highlight signifcant events in the university’s history specifcally about U of T’s Black community.

The frst Canadian-born Black doctor

Founded in 1827, U of T’s doors were originally open to Black students. One notable early alumnus was Anderson Abbott, the frst Canadianborn Black doctor. In 1857, Dr. Abbott enrolled at University College — established at U of T in 1853 — to study chemistry. In 1858, he began his medical degree at the Toronto School of Medicine, which later became associated with U of T. After completing a supervised placement with Dr. Alexander Augusta — a family friend and Black community leader who lived in Toronto at the time and received his medical degree in 1860 — Dr. Abbott received his medical license in 1861.

Dr. Abbott ran successful medical practices — frst in Dundas, Ontario, and later in Toronto — and wrote for multiple publications on topics such as biology, desegregation, and politics. Each year, U of T now awards one Black undergraduate student the Dr. Anderson Abbott Award, which is worth $4,000 “on the basis of academic achievement, fnancial need and contribution to the black community.”

Setbacks

A few years later, U of T backtracked by implementing several segregationist laws that barred Black students from attending the school. Segregation was particularly prevalent in education, with Ontario and Nova Scotia setting up legally segregated schools in the late 1800s to keep Black students separate from other students. U of T also refused Black students admission under segregation policies — in one documented case, U of T initially accepted Lean Elizabeth Grifn, who applied to U of T medical school in 1923, but later denied her entry when the administration realized she was Black.

Leonard Braithwaite — a U of T alumnus

and the frst Black Canadian elected to a provincial legislature — played a signifcant role in challenging school segregation. In his frst speech to the Ontario Legislature on February 4, 1964, Braithwaite spoke out against the Separate Schools Act — a law that permitted racial segregation in Ontario K–12 schools — in a speech at Queen’s Park. He argued that the days of segregated schools had passed.

Braithwaite put forward a motion that the province remove the clause allowing segregated schools. One month later, education minister and future Ontario Premier Bill Davis introduced a bill that repealed the 114-year-old provision allowing for segregation. The last segregated school in Ontario closed within a year, in 1965.

Contemporary history

One of U of T’s specifc actions to tackle injustice is the creation of the Anti-Black Racism Task Force (ABRTF). The U of T administration announced the task force on September 23, 2020, as part of the university’s response to global protests against anti-Black racism.

In March 2021, the ABRTF delivered a fnal

report outlining 56 action-oriented measures. These recommendations aim to tackle anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion and excellence across the university’s three campuses.

Assistant professor in the Department of History and historian of modern Africa Safa Aidid mentioned in an email to The Varsity that she’s seen a cultural shift at U of T in how it approaches academia and community. Aidid spotlighted U of T’s hiring of more scholars who teach Black Canadian, Caribbean, and African American history. Aidid added that she feels “fortunate to be part of the new wave of young black scholars at U of T.” Aidid also mentioned a shift in student interest toward Black history. “Students are certainly more engaged and interested in Black history. Many of the students I teach are new to African history, but what brings them into my classroom is a deep interest in Africa and a sense that they aren’t getting nuanced perspectives from the media or pop culture,” she wrote.

As a whole, Aidid recognizes the steps taken by the university to promote greater degrees of Black representation and inclusion. “Though we still have a long way to go, it is encouraging to see these institutional commitments,” she wrote.

Refecting on history with the BHM luncheon

Another action taken by Black U of T community members that has left a mark on the university is the creation of the Black History Month Luncheon. The luncheon is an annual event that Glen Boothe and his colleagues in the university’s department of advancement — which coordinates U of T’s fundraising and outreach eforts — started in 2002. It features speakers and food and celebrates Black culture and excellence, intending to foster a sense of community and inclusiveness.

On the legacy of the luncheon, Boothe expresses a sentiment of contentment and fulfllment in all it has done to positively impact the Black community at U of T.

“The biggest satisfaction is the continued and growing support [for the luncheon]. Growth is always a good barometer of success, and each year there is a new group or individuals volunteering to be a part of [the luncheon] in a meaningful way,” wrote Boothe in an email to The Varsity

On a Friday afternoon, Muslim students at UTSC can often be seen lingering after Friday prayers — also known as Jummah — to talk to Imam Omar Patel.

Patel says U of T informed him on January 22 that it was removing him as the UTSC Imam, for allegedly making an anti-Israel and antisemitic post on Instagram. Still, when U of T invited him back to campus just two days later as a “member of the public,” Patel felt it was important to come and lead Friday prayers.

“If I don’t come for Jummah, and they bring in another Imam, the students then complain that ‘we miss our Imam,’ [or] ‘we want our Imam back,’ and I can’t say no to that,” said Patel in an interview with The Varsity

Patel became the Muslim chaplain at UTSC in 2016. As an Imam hired by the Muslim Chaplaincy at the University of Toronto — an independent non-proft organization focused on supporting and engaging Muslim youth — he catered to Muslim students by providing counselling sessions and weekly programs. He was directly employed by the Chaplaincy, not by U of T, but provided services on campus; a university spokesperson explained to The Varsity that the university makes “informal, unpaid, volunteer arrangements” with chaplaincies.

Patel denies having shared the post that U of T received complaints about in the weeks leading up to his removal. In an interview with The Varsity , Patel described the university’s decision to remove him from his role after approximately eight years as “shocking.”

Since Patel’s removal, students have advocated for his reinstatement, and over 6,300 people have currently signed a petition by the Muslim Chaplaincy to get him back.

“I think it’s so unfair, really, because [Imam Patel] was the only resource that we had on campus. And for [U of T] to take it away from us and then not be transparent as to why, they really showed the way that they see us as students,” Yasmin Said, a fourth-year student majoring in population health and double minoring in psychology and biology who had participated in Patel’s weekly program, told The Varsity “It really hurts."

The incident explained

According to an article by the CBC, Patel’s removal came after Hillel Ontario shared social media screenshots with U of T administrators on December 1, 2023, which it alleged that Patel had posted on his Instagram story.

Hillel Ontario is an organization that works to support Jewish students across nine diferent universities, including U of T, through campus programming and educational and religious initiatives.

The Instagram story in question — which Patel allegedly posted 45 days before Hillel Ontario sent it to U of T administrators — related to the ongoing confict between the Israeli government and Hamas. It featured a picture of a soldier holding an Israeli fag with a mirrored image of the soldier on the other side holding a Nazi fag. The caption in the story equated supporting Israel with supporting Nazi Germany and described Israel’s actions against Palestinians as genocide.

Multiple organizations that advocate against antisemitism have argued that comparing the Israeli government to the Nazi government is inherently antisemetic. A 2022 post by the World Jewish Congress — an international organization formed to advocate against antisemitism in the years leading up to the Holocaust — argues that comparing Israel or Zionists to Nazis diminishes the pain of millions who sufered during the Holocaust, playing into what it describes as “holocaust inversion.” “The Israeli–Palestinian confict is a territorial

and political one, whereas the Holocaust was the attempt to systematically annihilate European Jewry,” the post reads.

Still, some recent commentators have drawn parallels between Israeli policies and policies undertaken by the Nazi regime. In a December 2023 essay in the New Yorker , Masha Gessen — a Russian-American and Jewish journalist who lost family members in the Holocaust — noted similarities between World War IIera ghettos and the “open-air prison” caused by Israel’s 16-year-long blockade of Gaza. They argued that treating the Holocaust as a singular event that can’t be compared to other events obscures potential lessons about our actions in the present.

Patel wrote that, at frst, when U of T sent him the screenshot of the story he allegedly shared, he found that the screenshot showed no Instagram username or profle picture. He brought this to administrators’ attention, but he says that U of T still told him to stop providing services because they needed to conduct an investigation into the post.

Five days later, the administrator sent Patel another screenshot of the same Instagram story, this time with his Instagram username and profle.

At the time the frst screenshot was sent, according to the CBC, Hillel Ontario posted an open letter about the screenshot and called on UTSC Principal Wisdom Tettey to hold Patel accountable. Hillel Ontario explained the story posted could entice violence against Jewish people. As of February 25, Hillel Ontario has taken down the open letter published on its website.

U of T’s Statement on Freedom of Speech states that no university members should use language or participate in any behaviour with the intent of “demean[ing] others” based on “group characteristics” such as ethnicity and ancestry. However, the policy notes that civility “may, on occasion, be superseded by the need to protect lawful freedom of speech.”

Patel claims that U of T was not transparent during its investigation of the incident and did not allow his employer, the Muslim Chaplaincy, to take part in it.

“I feel sad, I felt isolated. I felt that the institution that I cared for so deeply, providing services to staf, students, faculty, for a long time, didn’t have enough respect to be able to carry

an unbiased investigation or an investigation where they can share the details with myself or with my employer,” Patel said to The Varsity

He explained he tried many times to talk with U of T administrators to prove he had not posted the story on his Instagram; however, his pleas fell on “deaf ears.” “[U of T] failed me, they failed the Muslim students, and they failed the entire Muslim community. And it’s hurtful,” said Patel.

He alleged to the CBC that the second screenshot sent to U of T was altered in an attempt to “smear” him, as the frst screenshots had no ties to his profle or account.

When asked about Patel’s accusations, Hillel Ontario’s media relations stated to The Varsity that the organization asked U of T to investigate the issue after they received many reports of the “disturbing social media screenshots” from “_omarpatel,” Patel’s Instagram account. U of T, as of the time of publication, has not published any ofcial statement regarding the investigation or its decision to remove Patel.

Student reactions and advocacy

Zohal Akram — a third-year studying psychology and biology — has received spiritual and counselling services from Patel. She told The Varsity that Patel’s removal has left a huge gap for Muslim students who rely on him.

“He guided me toward getting the support I needed in difcult situations that I was in. And even now, to this day… he still checks up on students and still wants to know how you’re doing,” said Akram.

Usayd Ashraf, a frst-year student studying business and management, shared a similar sentiment. Having known Patel even before attending UTSC, he found that not having Patel as a chaplain makes him feel like he has lost vital resources. “His presence meant a lot to me. And I’m sure it meant a lot for others as well,” said Ashraf.

Both Ashraf and Akram expressed concerns about U of T’s investigation. “There was no proof of him committing whatever they accused him of committing,” Akram said.

Ashraf said he felt “scared” at the university’s lack of protections for Patel. “If [this] can happen to Imam Omar Patel then it can happen to any one of us [students],” he told The Varsity

On February 4, the Muslim Chaplaincy of Toronto started a petition calling on U of T to

apologize to Patel for the damage caused by accusations against him and to reinstate him as chaplain. In the petition, the Muslim Chaplaincy of Toronto states that the university’s investigation lacked “due process” or “transparency” and that the fnal letter sent to Patel on the investigation included no “evidence or reasoning for his termination.” The petition also brings up the lack of name on the screenshots frst sent by Hillel Ontario to U of T.

As of February 25, the petition has over 6,300 signatures.

Patel is worried about the lack of mental health support available at U of T that specifically caters to Muslim students and how this might cause students to lose faith in the university. He explained that, although U of T provides students with mental health supports, UTSC currently lacks a Muslim Chaplain available to students.

Although Chaplains serve primarily religious purposes, Patel has provided mental health support to Muslim students at UTSC. Since he was fred, Patel has had to stop providing counselling sessions and weekly gatherings. “We’re adding to the mental health crisis,” he said.

“I continue to come in to provide a level of support: a listening ear, a hand, a hug, if possible. Just any level of support to be present with students,” said Patel.

According to Scarborough Campus Students’ Union (SCSU) President Amrith David, the SCSU and the UTSC Muslim Student Association (MSA) are currently working on steps to “voice the concerns of students to administration.” Currently, their goal is to find a way to reinstate Patel and determine what happened during the university’s investigation. According to David, the SCSU and the MSA have had meetings with UTSC acting vice-president and principal Linda Johnston about this.

Johnston confirmed to The Varsity that the university undertook a fact-finding investigation in response to a complaint about a social media post but wrote that she could not provide more information for privacy reasons.

She emphasized that the spiritual support that chaplains provide is distinct from mental health counselling that the campus makes available and added that the university “[encourages] the Muslim Chaplaincy to make other chaplains available to our students as soon as possible.”

Hannah Guo Varsity Contributor

Hannah Guo Varsity Contributor

In 1608, Mathieu Da Costa — an interpreter for Samuel de Champlain’s 1605 excursion — became the frst Black man to set foot on the landmass known today as Canada. James Douglas, the frst appointed Black politician in Canada, rose to the position of governor of British Columbia in 1851. In 1917, Black Canadian railway workers initiated the frst Black railway union in North America, later afliating with the American union Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Despite the fact that Black people make up 4.3 per cent of Canada’s population as of the 2021 census, no K-12 curriculum in any province in Canada mandates teachers discuss Black history. U of T does not require students to take classes about history focused on Black people in Canada or worldwide. In interviews with The Varsity, however, professors and students discussed the importance of learning these histories, calling for the university to make a concerted efort to incorporate them into curricula and possibly require courses on Black history.

What courses and programs does U of T ofer on Black histories?

Bárbara Simões Daibert is a visiting professor in the Centre of Comparative Literatures who teaches CDN335 — Black Canadian Studies. In an email to The Varsity, she noted a lack of awareness of Black history within U of T. She highlighted how many Canadians don’t know that slavery existed in Canada, and the fact aroused surprise from students when she mentioned it during a lecture.

Daibert described teaching CDN335 as “exciting.” She noted that the course ofers her a chance to “show [her] students the diversity of their country

and the efects of African slavery in the Americas” and deconstruct “longstanding myths concerning identities.”

7.5 per cent of Torontonians identifed as Black, as of the 2021 Canadian census. However, The Varsity only found two courses ofered this year at UTSG that appear to focus specifcally on Black Canadian history: CDN335 and HIS265 — Black Canadian History. Only 13 students are currently enrolled in HIS265, and 20 are enrolled in CDN335. U of T ofers another course at the Scarborough campus — HISB22H3 F: Histories of Black Feminism Canada: From Runaway Slaves to #BlackLivesMatter — and none at UTM.

U of T also ofers the Certifcate in Black Canadian Studies, which students can earn by completing a group of courses across various programs that tackle topics from systematic discrimination to forms of resistance. According to Daibert, this certifcate is a “great and necessary step towards a more inclusive world.”

Currently, U of T’s African Studies Program — which includes a specialist, major, and minor — offers courses on socio-economic, cultural, environmental, and political transformations in Africa. The program aims to provide multidisciplinary perspectives on African histories, societies, and diasporas, and includes language studies.

Canada’s Black history

The experience at U of T refects broader Canadian trends. A 2023 study commissioned by the Canadian Commission for the United Nations Educational, Scientifc and Cultural Organization surveyed K–12 curricula across the country. It found a lack of curricula on Black Canadians, with many curricula only focusing on Black American history instead of highlighting the contributions of and specifc struggles faced by Black Canadians.

Some Ontarians have previously called for the

province to make Black history a K–12 education requirement, noting that the focus on American history shifts focus away from Canada’s historical and continued anti-Black racism.

Some other Canadian universities — including the University of Guelph and York University — ofer programs or certifcates in Black Canadian studies or Black Canadian History. However, other universities, such as the University of Ottawa, lack programs in Black Canadian studies or even courses on the topic.

In March 2021, the U of T Anti-Black Racism Task Force released its report, which included 56 recommendations that aimed to confront antiBlack racism and foster Black inclusion and excellence. The report included one recommendation related to Black pedagogy, or teaching methods designed to promote equity in educational settings: that the university “enhance the number of workshops and learning circles focused on anti-racist and inclusive pedagogies” and ofer workshops on anti-Black racism.

U of T accepted all 56 recommendations and tracks progress on these recommendations through its institutional commitment dashboard. The dashboard shows that the university has hired two people on term contracts to focus on anti-racist pedagogies, has developed a workshop series, and has hosted events. It has also curated resources such as the Anti-Black Racism Pedagogical Collection and is creating a repository to showcase Black leaders in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Incorporating and requiring Black histories

Ann Lopez, a professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and co-director of U of T’s Centre for Black Studies in Education, wrote in an email to The Varsity that U of T could both mandate specifc courses on Black histories and work

“Make an impact.”

This is the slogan adopted by De-Mario Knowles, a second-year UTSC student double majoring in neuroscience and mental health studies with a minor in French, who has become a prominent fgure across the UTSC community. A poet and keynote speaker for the mental health charity Step Above Stigma and hailing from Durham, Knowles worked with the university to create the Mental Health Minute — a series of short videos educating UTSC students on how to access mental health services.

The Varsity spoke with Knowles about his many passions and the importance of making an impact on his community.

The Varsity: How did you get involved in both poetry and keynote speaking?

De-Mario Knowles: It all started out by accident. I was accepted into this nonproft organization called Teen Perspective. We were an activism organization made by teens for teens. We wrote journal articles about diferent stuf going on in the world.

I wanted to do something that would make me stand out. When Bell Let’s Talk Day [which aims to destigmatize and raise awareness of mental health issues] was coming around, my president at the time was like, “Guys, we should put out a poem,” and she asked, “Who wants to volunteer?” And I raised my hand, because why not? And I instantly regretted the decision.

I wrote eight verses about how I felt about mental health and how it’s portrayed in the world. I literally titled it “I wrote this poem about mental health,” and posted it on my Instagram.

I started realizing how impactful being vulnerable in the public eye can be. I realized when I write stuf, I want it to be like a conversation. When I can write like that, I can allow other people to feel recognized about how they feel. Public speaking came as an add-on. I started getting invited to schools in my area to give speeches about my poem. So that’s the backstory. It’s not anything too fancy. I’m just a regular guy, 30 minutes away from Scarborough.

TV: You wrote a three-part poem project titled “From hurting to healing,” What was the process that went into creating that series?

D-MK: I originally started with happy poems that were encouraging. I’d be like, “Hey, it’s okay if you go through this; things will get better. You just have to stay optimistic.”

Sometimes, I just want to vent about how I feel and just be sad. I wanted the poem project to be exactly like my emotional timeline, where the frst one is super sad. Then, the middle one moves forward from what happened. The third one is what I learned from it and how I’m going to apply it to my future.

The frst poem that I wrote in the project, the one about grief, was actually written one year prior. I decided to make the other two as an expansion of it. I think [the poem about] grief took a while for me to put out because it’s my most personal poem.

It was about a very traumatic moment in my life. I was really scared, but I felt like this is something that can really impact the way that people feel. If I can put this out, I can start a dialogue about a very important topic that can resonate with many people.

I was lucky enough to win an award for it from an organization called Step Above Stigma. It’s

defnitely one of my favourite things that I put out in my poetry career.

TV: You began collaborating with UTSC’s Health & Wellness Centre to produce Mental Health Minutes, a series of brief videos aimed to raise awareness for department services. How important is mental health advocacy for you?

D-MK: Mental health advocacy is very important for me because I myself am someone who lives with mental health struggles on a day-today basis. I feel like there’s never too much advocacy for mental health.

to integrate Black pedagogy into existing courses. “Systemic and lasting change requires intentionality. Mandating specifc courses is the intentionality that is sometimes required to ensure that such knowledge that was often excluded is included,” she wrote.

Daibert echoed this idea. “We have to have specifc courses on this subject, on Black Canadian studies, simply because these studies are a very important part of what happened and still happens in this nation called Canada. On the other hand, it is necessary to include other non-white forms of knowledge, and this includes pedagogy, in our existing universities and curricula,” she wrote.

Some universities have implemented policies requiring students to take classes focused on Indigenous content before graduation. However, The Varsity could not fnd any examples of Canadian universities requiring courses focused on Black content.

“I would love to start by learning about Black culture,” Timothy Wang, a fourth-year mathematics student, said in an interview with The Varsity. As an international student at U of T with a Chinese background, Wang wrote that growing up, he and his friends rarely had the chance to meet people of other ethnicities. Coming to Canada for university, Wang felt that, although he had more chances to meet individuals from other backgrounds, he had little chance to learn about Black history in Canada.

“It is important for the contributions of Black Canadians to [Canada to] be embedded in courses beyond Black History Month,” wrote Lopez.

When asked for comment on its incorporation of Black history in course curricula, U of T told The Varsity that community members can refer to the Certifcate in Black Canadian Studies, the Anti-Black Racism Task Force dashboard, and the Scarborough Charter, which the university signed in 2021.

There’s always this stigma that paints a negative light on people who have mental illnesses. People with mental illnesses are just regular human beings. They shouldn’t have to deal with this negative label on their back 24/7. I feel like mental health advocacy helps to combat that.

TV: Your slogan has been to “make an impact,” What does making an impact mean for you?

D-MK: See, that’s a good question. I’m trying to fgure that out to this day. I think making an impact just means creating the change that you want to see in the world.

I like how ambiguous it is. I feel like it can apply to many diferent contexts. It can be for educational advocacy, journalism, science, or anything, as long as it makes a diference.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Vanessa Opoku — a fourth-year student double majoring in human biology and population health — is currently running under the ELEVATE UTSC slate.

She is the current Racialized Student Collective Coordinator with the SCSU. In this role, she organizes cultural events and operating hours for the Racialized Students’ Collective — an SCSU ofce that runs weekly events and aims to bridge the gap between the SCSU and student clubs that may not be aware of the union’s club funding.

“From what I've surveyed from students, there's a lot of skepticism with SCSU,” said Opoku in an interview with The Varsity. She believes there are a lot of “improvements” that the SCSU can make by forming closer connections with departments and the university as a whole, and she feels her experiences shape her to be a good candidate for the job.

Hunain Sindhu is running for SCSU president under the IMPACT UTSC slate. As a ffth-year environmental geosciences specialist, he has been interested in campaigning for an SCSU executive position “for a while,” he said in an interview with The Varsity. He served as president of the Muslim Students’ Association over the last two years and is the current SCSU director of physical and environmental sciences.

“The president is responsible for shaping not only the vision, but also sort of the mindset of the team and leading the executive team of SCSU… I have a lot in mind that I want to change, or implement, or make better,” said Sindhu in an interview with The Varsity

Her main campaign points include creating a community care hub with mental health support, providing resources to students through discounts to platforms like Grammarly, and championing a Bias Reporting System and Anti-Racism Task Force to ensure a safe and inclusive environment for all.

“I want to advocate for you correctly,” she said.

Desteenie Africa is running on the ELEVATE UTSC slate. A ffth-year city studies major with a double minor in English and sociology, Africa told The Varsity that her familiarity with current academic policies and her wish to “make students more prideful that they are specifcally at UTSC and not just U of T as a whole” motivated her to run for this position.

The primary focus of Africa’s advocacy, if elected, will be extending the credit/no credit period to allow UTSC students to choose no credit after receiving their exam grades.

Africa also hopes to advocate for a policy where courses with over 100 students enrolled must ofer a web or hybrid option.

Finally, Africa wants to introduce a course recovery policy that would let students remove a failing grade from their transcript if they retook and passed the course. Such a policy exists at UTM, but not at UTSC or UTSG.

Africa has worked with AccessAbility Services — a thea student and academic service equity ofce at UTSC that coordinates student accommodations — since her frst year. She said this job has helped her identify existing communication barriers between administration, professors, and students, which helped spark her interest in the VP AUA position.

“I’m like the voice for everyone,” Gori Debo-Adesina, a fourth-year political science and philosophy double major, told The Varsity when describing why he wanted to run for VP external.

Currently representing philosophy students on the SCSU’s Board of Directors, he said that his experience advocating for students and forming relationships with his high school administration prepared him for the role. Debo-Adesina’s campaign focuses on addressing students’ needs by revamping health, housing, and transit.

To ensure students can access quality health insurance after graduation, he wants to work with GreenShield — the SCSU’s current health insurance provider — to create a system where students can retain the same healthcare plan after graduation, where the union would pass insurance on to individual graduates.

“We know how important residency is for people and, even within the opening of Harmony Commons, people are still struggling to fnd a good residence,” he said. To address this issue, he hopes to create a platform where students can fnd affordable housing options with landlords vetted by the SCSU.

Debo-Adesina also hopes to continue the SCSU’s advocacy for a bus connecting the UTSG and UTSC campuses and a universal pass similar to that provided by the UTMSU.

His main campaign points include overseeing an expansion of the Student Centre to create an inviting, equitable space for campus groups; designing policies so that UTSC provides students from globally distressed regions with fnancial, academic, and mental health accommodations; and establishing avenues of communication so students can share their aspirations and concerns about the SCSU’s initiatives and operations.

“Really getting those ideas from students that a lot of students may have is important,” he said.

Zanira Manesiya — a ffth-year student double majoring in neuroscience and mental health studies and minoring in English literature — is running as part of the IMPACT UTSC slate. Currently, she sits on the UTSC Campus Afairs Committee and the Council on Student Services, which advises UTSC on student life. She also works as a coordinator for the SCSU’s Food Centre.

In an interview with The Varsity, Manesiya outlined three main focuses if elected.

First, she plans to advocate for increased departmental scholarships or grants to further support students fnancially. She also hopes to advocate for afordable textbooks and other course materials for students.

Second, she plans to lobby for “academic policies that will ease the academic burden on students,” such as pushing the deadline for a student to designate a course credit/no credit until after students receive their course grades.

Finally, she hopes to introduce an Academic Advocacy Coordinator role at the SCSU to help students deal with academic integrity ofences and support the work of the VP AUA.

“Working with people of all backgrounds, both locally and globally, has championed my belief that supporting each other and working together is the best way to move forward,” she told The Varsity

Omar Mousa, a fourth-year linguistics major specializing in psycholinguistics, is running for VP external on the Impact UTSC slate.

In an interview with The Varsity, Mousa described himself as a person “who likes to take the lead.” He said that, through direct work with the UTSC administration and holding the administration accountable for their actions, he could make an actual diference as a VP external.

Mousa’s campaign focuses on decreasing the fnancial burden for students. He wants to implement a free or discounted transit pass for UTSC students and collaborate with the administration to reconsider campus housing fees.

He also said that one of his objectives is to organize rallies that would hold the administration responsible for recognizing global events that afect students. He previously organized walkouts for the Palestinian Culture Club and continues to work with the Toronto Chapter of the Palestinian Youth Movement.

Finally, Mousa wants to strengthen tri-campus solidarity through grassroots organizing on topics such as the Boycott, Divest, Sanction movement — a movement that aims to exert fnancial pressure on the Israeli government.

Rafay Malik — a third-year student specializing in political science — is the only candidate running to be the 2024–2025 Scarborough Campus Students’ Union (SCSU) vice-president, campus life. A part of the IMPACT UTSC slate,

Arthur

Aanya Sinha, a fourth-year international student double majoring in psychology and religious literature, is running as part of the ELEVATE UTSC slate.

Currently, Sinha is a part of the Mental Health Advisory Board led by Neel Joshi, Dean of Student Experience & Wellbeing. She believes her experience in mental health advocacy and awareness makes her well-suited for the role.

“I care about people and I care about how UTSC is forming… I am very proud to say I’m from UTSC and I want to make sure that that legacy goes on,” she told The Varsity Her platform focuses on organizing events for cultural understanding and enhancing mental health on campus. Sinha, who identifes as LGBTQ+, wants to highlight related events and initiate more collaboration with cultural clubs. She also wants to support facilities, improve safe spaces funding, increase scholarships, and promote equity by ensuring accessibility resources.

Sinha says she is devoted to making sure union members support students by promoting transparency. “I think the biggest problem a lot of students go through is not knowing about community and not having friends that are going through the same thing as them.”

Malik has been involved in a number of clubs at UTSC, including the Pakistani Students’ Association and the Muslim Students’ Association. Malik has also served as an emcee for the SCSU’s Frosh.

In an interview with The Varsity, Malik emphasized a few of his campaign focuses.

First, he plans to organize a start-up fund for clubs to streamline the process of creating a club on campus. He hopes that students who submit a request to start a club can be immediately accepted, receiving money from the fund to cover their start-up costs.

Second, Malik hopes to improve collaboration between the SCSU and the Ofce of Student Experience & Wellbeing (OSCW), which oversees multiple departments, including AccessAbility Services; the Academic Advising & Career Centre; the International Student Centre; and Student Housing and Residence Life. In particular, he wants to improve transparency and communication between the two organizations and introduce regular meetings between staf members to plan events ahead of time.

Finally, he’s planning to “bring back the Toronto Raptors subsidized sports games” and organize a beginning-of-the-year concert that would be free for students to attend.

If elected, Malik hopes to see the new SCSU executive team be “much more involved and incorporated into the actual student body” so students can recognize and approach them.

didate running for 2024–2025 Scarborough Campus Students’ Union (SCSU) vice-president (VP) operations as part of the IMPACT UTSC slate. Bah has been an executive for U of T’s Black Students in Business club for fve years. She is also involved in the UTSC Geography and City Studies Student Association. In an interview with The Varsity, Bah said that her extracurricular activities “taught [her] a lot about leadership and budgeting.” She’s also familiar with the union’s operations, having worked at the SCSU front desk.

Bah’s campaign aims to support students in managing their fnances amid infation. Her three priorities centre around improving the SCSU’s Food Centre, the union’s student tax clinics, and Bistro 1265’s menu. Through fnancial workshops she wants to “help students better manage their money” given recent infation.

Additionally, Bah hopes to create a “studentto-renovation committee” that would direct a renovation of the student centre, ensuring that students’ voices are heard and implemented.

Concerning transparency, Bah is committed to overseeing expenses and ensuring “that these [transactions] refect what students are really wanting on campus.” Lastly, she hopes to encourage students to take advantage of what SCSU has to ofer and “[know] where their money is going.”

Kamilla Bekbossynova

Shifara hopes to establish a Community Care Center as a part of the Student Center expansion to prioritize proactive outreach to address student well-being. She also plans to implement an online tool where students can share their experiences related to discrimination anonymously as a way to “pinpoint recurrences” of particular issues. Finally, she hopes to partner with LGBTQ+ organizations to introduce new bursaries, programming, and safe spaces.

“I’m running for this role because I’m passionate about providing that inclusive environment for all UTSC students and uplifting the diverse and underrepresented communities here on campus,” Shifara told The Varsity. “I want everyone to be seen and heard. And I’m here to listen and take responsibility to act on students’ concerns.”

Shifara said that she aims to work with the president to propose policies that provide fnancial, academic, and emotional support to those from distressed regions. She also plans to engage with a wide range of campus groups to run events specifc to certain marginalized groups.

Shifara’s experience includes helping with Frosh, teaching youth at her community centre, and participating in Black Student Engagement — a program through UTSC’s Ofce of Student Experience & Wellbeing that provides spaces for Black students to access support services.

How to vote: UTSC undergraduate students can cast their votes from March 4–6, 10:00 am to 6:00 pm, in the Instructional Centre, Student Centre, and Bladen Wing hallway. Along with voting for candidates, students can vote to approve or not approve a $7.23 per session per full time student and $3.62 per session per part time student levy paid to Regenesis UTSC, an environmentalism club.

What does each role do?

The President acts as chief spokesperson for the organization, leads the other executives, and helps determine the union’s direction.

The Vice-president (VP) academic and university afairs represents the union in various university committees, lobbies U of T to improve students’ experiences, and provides advice to students on academic afairs.

The VP external develops the union’s political campaigns and represents the union externally and in some university committees.

The VP operations creates the union’s budget, administers payroll, negotiates with staf, and keeps documents up to date, among other responsibilities.

The VP campus life is responsible for recommending, scheduling, advertising, and coordinating all of the SCSU’s events, along with processing clubs’ requests for funding and representing the union on university committees related to residence, food, and licensing.

The VP equity raises awareness of discrimination at UTSC and in the community, ensures that the union’s actions refect the union’s anti-oppression stances, and acts as the ofcial liaison with U of T organizations that handle topics surrounding discrimination.

Beauty is wild.

Wild in the depth of its meaning.

Wild in the interesting ways it can be expressed. Wildly beautiful in the diverse ways it can be interpreted and understood by its audience.

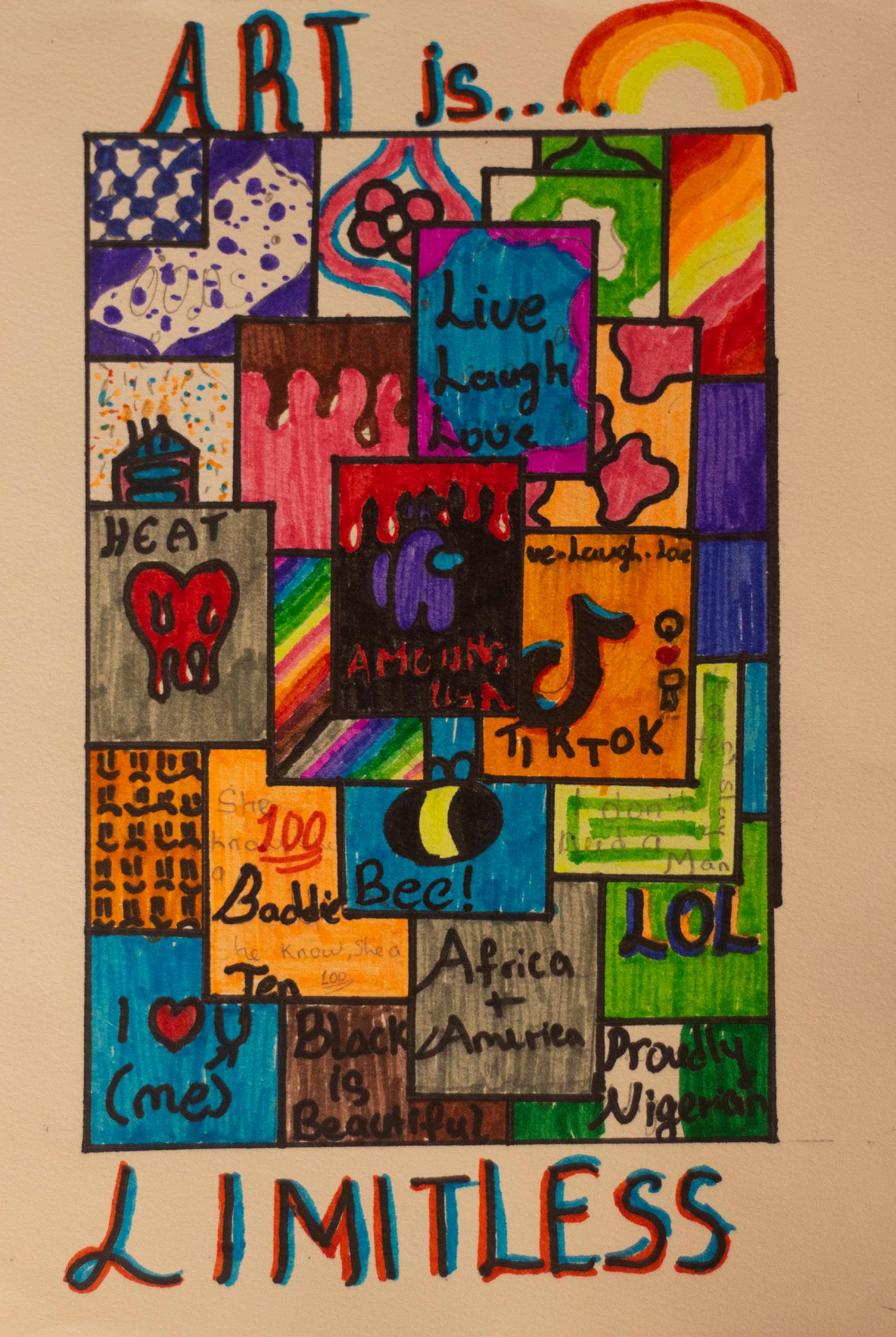

Chizuloke Olisaekee, in her 12 years on earth, exemplifed beauty in many wild ways.

She exemplifed beauty through her love for dance, her art, and her stage performances — Miracle being her biggest and most special performance. She elegantly served many roles during this school musical. As a bookseller, she proudly displayed beauty as she walked across the stage showcasing her own storybook, Shy Sharon. As a ribbon dancer, her beauty radiated as she majestically swung the red ribbon, tall and proud, in many directions.

Chizuloke symbolized beauty as she distributed and read Shy Sharon to older and younger school children in her home country, Nigeria. She embodied beauty as she lived out her fctional story Shy Sharon, when she helped a withdrawn classmate slowly bud out of her shell to make a presentation in class — a classmate who then also began to advocate for her needs to the teacher.

Chizuloke boldly demonstrated beauty in dance, regardless of who was or wasn’t watching. A proud lover of Afrobeat, K-pop, and gospel, she danced to the music of her favourite artists playing in her head as she walked the streets of Toronto, rode the bus, spent time with friends, and even when she lay with her back to the foor as she fxed a broken chair. She magically wooed the audience during her last school talent show when she snuck surprisingly onto the stage, injecting new dance steps into the routine, electrifying the room with a resultant roar.

She displayed beauty as the youngest person in the classic choir in church.

Chizuloke symbolized beauty by embracing her identity, wearing her natural hair — Black and proud — and standing up for her culture and food. For her, food was more than just sustenance. It was an expression of identity, a connection to others which she passionately expressed through her desire to help people understand Nigerian food and culture. Chizuloke proudly cherished her name and its meaning — God is sufcient — in several beautiful ways. She made sure she taught others how to pronounce it correctly and carefully decorated it with fowers and/or love symbols whenever she wrote it.

Through her love for nature — puppies, fowers, and preserving the earth — Chizuloke radiated beauty by prioritizing reuse. In her own small ways, she redesigned used boxes, wrapping papers, and containers that would otherwise have been thrown away.

By seamlessly connecting with people around her, irrespective of age, nationality, and identity, and making sure everyone felt included, Chizuloke expressed beauty. Her love for God, her family, friends, and community, which she willingly gave back to, is a great example of beauty, which we hope to carry on.

Give Chizuloke a piece of paper, pen, pencil, or Sharpie and wait to see the dimension of beauty she will produce. It is no surprise her class teacher always looked forward to her assignments, especially her writing and art projects, as they were laced with passion and creativity! Her beautiful creativity went beyond writing materials; she also expressed it in the unique ways she designed food. She had big dreams of baking unique Afrocentric-designed cakes when she got older.

Though her physical candlelight was tragically blown out, her beauty lives on in its purest and wildest form. The light her beauty lit in the hearts of many shines brighter. She lives on in our hearts and is fondly celebrated in The Varsity’s BHM issue and always.

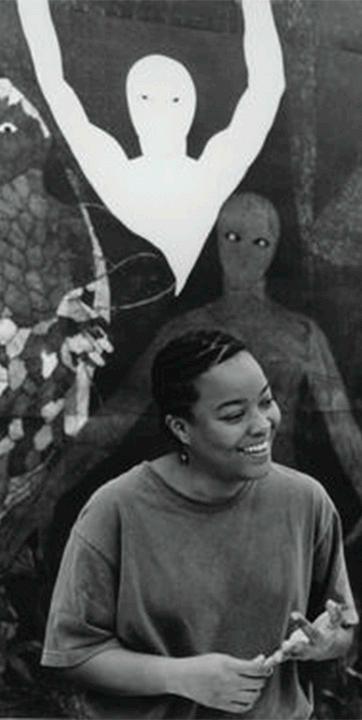

Content warning: This article mentions suicide. True inspiration, possessing both power and fragility, and capable of transcending assumptions to reveal an intrinsic spirit — the autonomous, technically adept, and sacred creations of AfroCuban printmaker Belkis Ayón (1967–1999) hold a wellspring of appreciating how one conveys one’s needs as an artist and as a human.

For those who regard art as the paramount language for the human condition, a retrospective of Ayón’s art is indispensable. She intimately comprehends the mechanics of infuence, reference, and exposition, seamlessly weaving the composition of life into art memorably.

Born in Havana, Ayón was an applauded printmaker and teacher active in the feeting decades of the post-modernist art period and the Período especial en tiempos de paz — a term that roughly means “special period in the time of peace” — in Cuba.

Even in her childhood, during an economically depressed period in Cuba, her talent was not overlooked. Starting at the age of 12, she attended prestigious art institutions in Havana and eventually became a teacher at Instituto Superior de Arte de la Habana (ISA), where she got her Bachelor of Arts in printmaking.

This kind of routine and discipline inherent in the practice of art cultivates true masters like Ayón. For any artist, discipline is a manifestation of spirit. There’s a symbiotic relationship between movement and representation, and that relationship underscores the inevitability of change within the artistic journey.

Collagraphy: Ayón’s medium of artistic expression

Ayón’s brilliant visual compositions cannot be separated from the socioeconomic landscape of Cuba during her time, particularly the tumultuous

Período especial en tiempos de paz beginning in 1991 amid the collapse of the Soviet Union. During this era, Cuba felt an economic and resource depression fuelling rationing and social demonstrations. The reality of this period made the reality of Ayón’s art indeed a poignant political response to the scarcity of resources, which compelled her to harness creative ingenuity to an intimate use of visuals and symbols in her work.

Her chosen medium was collagraphy, which she defned as an engraving process consisting of a type of printed collage formed from various materials arranged and pasted on cardboard supports. Collagraphy takes a lot of physical intricacy and a nuanced understanding of the texture that comes out of this art medium. One advantage of collagraphy is that it allows an artist to produce works in quantity during a period of fewer resources.

Through collagraphy, Ayón captured the essence of conficts caused by her reality and provided a powerful commentary on the human condition amid adversity. At this point, her work became more monumental in its composition, redrawing a space to confront the censorship, violence, exclusion, inequities, and power structures of late twentieth-century Cuba.

The sense of drama that unfolds in her compositions is portrayed by a range of lightness and darkness, which grows bolder in her work as she progresses in her artistic career. These monochromatic colours of black, white, and grey are employed to characterize the silhouettes of her symbols, where the inspired composition begins the mystery.

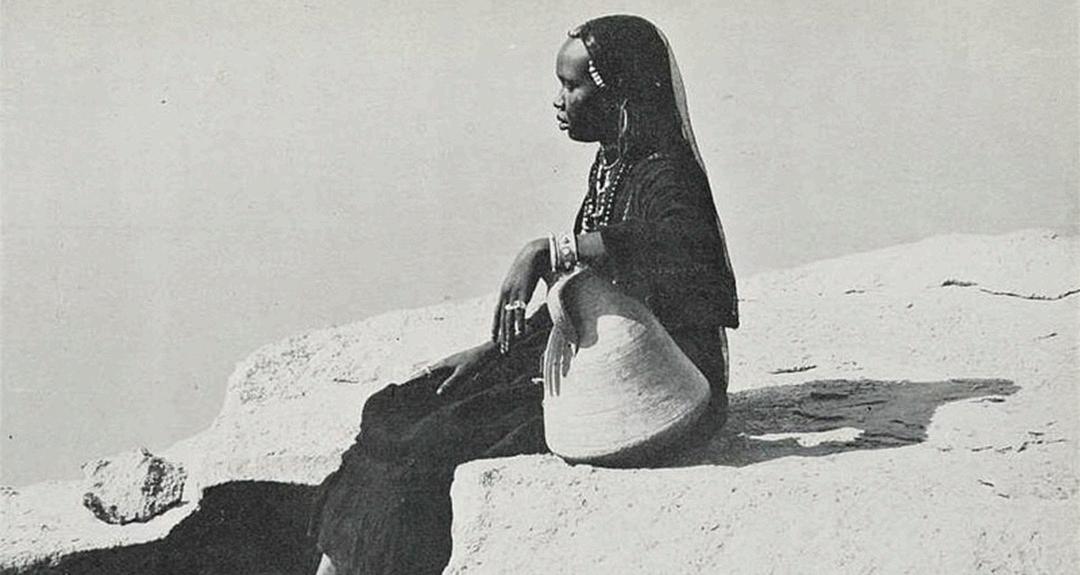

Ayón’s inspiration from West African spiritual traditions

Drawing from religious traditions of the Cross River region in West Africa, the Abakuá Society emerged in 1836 as a clandestine force among young Afro-Cuban men, particularly in Havana, as a defant response to the dehumanization of slavery and oppressive regimes.

Ayón leaned heavily on the mythology of

Abakuá, a society that was forbidden to women.

While researching its secretive practices, she encountered stories of the goddess Sikán — a woman “martyred by men to reclaim the sacred voice,” she explained in a 1993 interview. The symbolism of the fsh, coveted as a sign of wealth, resonated deeply within the Abakuá mythos; men sought to venerate and appropriate its power, sacrifcing the goddess Sikán and animal skin to make instruments that contained the sacred sound.

Through her exploration of these themes, Ayón illustrated a complete yet unseen imagery through the textures of the society’s symbolism, from her scenes of initiation rites to her salient portraits of Sikán.

Sikán, embodying the language and norms of a male-dominated society, serves as Ayón’s conduit to acknowledge the often overlooked but deeply felt presence of women within Cuban reality.

This dynamic relationship exposes the contradictions and complexities of collective memory.

Sikán’s legend, in many respects, morphs into a cautionary tale, reinforcing the marginalization of women within the Abakuá tradition, reminiscent of Eve’s role in the biblical narrative of original sin. Ayón subverts the Abakuán Sikán myth by ofering a critical, outsider perspective on a society and mythology dominated by men.

Her deliberate reinterpretation of this lore is acutely aware of the intersecting realities of history, aesthetics, culture, and language, inviting contemporary audiences to reevaluate their idealization of these narratives. Within the enigmatic folds of the Abakuá secret society of men and with the iconography of Catholicism, Ayon conveyed the complex composition of Cuba’s cultural and spiritual roots.

Strength and vulnerability in Ayón’s endeavours

Ayón’s dedication was not without burden, as her death by suicide at the age of 32 left a large void in the artistic landscape. Nevertheless, her

Divine Angubua Associate Comment Editor

work and talent continue to cast a profound and mysterious aura, enveloping Cuba with a cloud of spirit that remains cherished and protected. Recognizing how an artist devotes attention to reality is a discipline that requires a great level of spirituality. In the enigmatic depths of the endeavours of artists such as Belkis Ayón’s lies a profound paradox of strength and vulnerability where the relentless pursuit of artistic expression converges with profound introspection, creating masked masterpieces that resonate with timeless power.

At frst, give thanks, for He makes all things new, Then clean your fruit for rot shall spoil the soul, Break gently as grace these roots of wrath, and watch for Time who feasts on tender fesh. Do not dwell on the price you paid for life when food is set, for regret makes the stew run cold.

Remember who you were when fullness was empty rooms where witches went to purge, the fesh of mango child, the heart of a lost sheep, Bring down the yams of labour now,

Let sweetness draw the juice of lust, And grind the grain of ghostly past, As spinach heeds to tears of brine, Like ichor at the starved altar, give with desert what your body has borne. There is wilderness within so wet and blue with night, Where gods with golden claws may hunt and demons dance beneath the virgin moon, Where, time was lost and you shall fnd me, Where, Cobalt fruit, golden seed, you wept as you consumed, There exists, a place where you fll up the deeper dark, With noise, and slick, and breath come apart, And it was good, For you have claimed it so. The bruised skin from which you bite, the forked creature that stalks in pale light,

Give thanks, for this was made for you.

Xarnah Stewart Varsity Contributor

Xarnah Stewart Varsity Contributor

The 1979 release of the song “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang marked a pivotal moment in music history, introducing the world at large to hip-hop and rap. Little did anyone know, at the time, the profound and lasting cultural efects these genres would have on the entire musical landscape.

Since the release of “Rapper’s Delight,” hiphop has evolved into a multifaceted cultural phenomenon, giving rise to diverse subgenres such as East Coast, West Coast, gangsta rap, conscious rap, and trap music. This evolution has allowed hip-hop to transcend cultural boundaries, becoming a global force that infuences music, fashion, language, lifestyle, and activism. Hiphop was and continues to be a platform for Black and other marginalized communities to amplify their historically silenced voices.

It’s not only the original lyrics of MCs that deliver a message of resistance; hip-hop also created the rebellious art of sampling. Sampling is a fundamental and distinctive element of hip-hop music production that has profoundly impacted the genre itself and the wider music industry. It involves taking a portion, or “sample,” of a preexisting sound recording and incorporating it into a new musical composition. This practice emerged as a creative and cost-efective way for early hip-hop producers to craft beats and create unique sonic textures.

The history of sampling

During the early twentieth century — both in New Orleans and elsewhere — jazz musicians frequently incorporated hooks, licks, progressions, or snippets of melodies from their fellow musicians’ compositions into their live performances. This practice was a form of homage — which is something that would continue in later in rap music sampling — that was rooted in a genuine sense of respect and admiration for the original composers.

The act of “borrowing” these musical fragments became a widespread tradition and it contributed to a playful and enjoyable atmosphere during live jazz events. This not only pleased the audience but also added an extra layer of enjoyment to the vibrant world of jazz performances.

With the evolution of technology, sampling went on to develop beyond its jazz origins. Some historians cite the invention of the Mellotron electronic keyboard and its predecessor, the Chamberlain, as some of the earliest pieces of sampling technology. But it wasn’t until the 1970s and the 1980s, starting with the mixing and manipulation of vinyls done by DJs and MCs in South Bronx, New York City, that sampling became the art form we know today.

Switching between two vinyls on two separate turntables during street parties and nights at the club, DJs would draw drum beats from one and vocals from the other, looping and playing the tracks over the other and seamlessly binding them together. Sampling was popular because it was cost-efective: all one needed was the vinyls they wanted to use and any two sets of turntables, which were extremely common and easy to fnd in the 1970s and 1980s.

Sampling for Black artists

American music critic Amiri Baraka argued in his essay “Technology & Ethos” that Black people in North America had to create their own technology to fnd liberation, since preexisting technology was often made to exclude the Black perspective. In fact, innovations in music often primarily occur due to the lack of technology that people have to reproduce the sounds they desire. Black people thus had to create their own sounds.

It is no wonder, then, that new technology began to emerge in Black communities in the 1980s through to the 1990s, after the Civil Rights Movement had used television

and radio to its advantage. Black artists used stretching and sampling in their bedrooms, and fgureheads like Herbie Hancock “hacked” the synthesizer to develop the sounds that he was looking for. New musical genres and styles emerged when Black people made room for themselves and adopted mainstream technology to create their own means of production and sound.

Sampling, one might argue, originated as a part of a resistance against mainstream forms of technology that excluded Black people. This might be why sampling, from the moment it became a powerhouse in the music industry, started to be seen as a threat. When it travelled beyond the neighbourhoods where it originated, the industry started trying to take it down almost immediately.

The death of sampling

Music never truly became commodifed until the rise of the Industrial Revolution and the creation of the phonograph. People stopped making music and started buying it instead, and music became less about music and more about money.

The lawsuit Tuf City brought against the Beastie Boys in 2012 showcases how the modern world prioritizes money in music. The record label Tuf City attempted to sue the Beastie Boys for using a drum sequence from the 1982 song “Drop the Bomb” by Trouble Funk in their song “Hold It Now, Hit It.” However, the lawsuit was fled by Tuf City without Trouble Funk even knowing, and a day before it was fled, one of the founding members of the Beastie Boys, Adam “MCA” Yauch died of cancer. Even after Yauch had passed, the record label did not back down, showcasing that the lawsuit was, above all, an aggressive grab for money.

This lawsuit, like many other aggressive sampling lawsuits, stemmed from a 1991 US District court case Grand Upright Music, Ltd. v Warner Bros. Records Inc., which made artists responsible for making sure they’d been granted permission from the original artist before sampling music.

This lawsuit changed hip-hop music forever. Before, artists had been able to build their entire albums from samples upon samples of other music without thinking twice. But the 1991 ruling led to the gradual decline of the artform; now, to sample, you have to be able to aford paying royalties to the original record label and artists — or to aford being sued.

This is why now, you only see people like Kanye West and Nicki Minaj pulling interesting

and recognizable samples out of their libraries and into their iconic albums. Artists like them do so as if to advertise their wealth. This made sampling inaccessible to most hip-hop artists, especially in hip-hop’s early days when most rappers and MCs were coming from less-thanfavourable circumstances. This, to me, rings true to the constant class oppression that society is always forcing Black people into.

But understanding what constitutes intellectual property and what counts as stealing is central to the legality of sampling. Sampling had been deemed okay when people did it during street parties where no one was making money, but it suddenly became near-criminalized the moment those same people started to make money from music.

As Craig Jenkins put it in his review of Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold us Back , “Overnight it became forbiddingly difcult and expensive to incorporate even a handful of samples into a new beat… producers scaled back their creations, often augmenting one choice groove with a bevy of instrumental embellishments.” Even though the censoring of artists led to new sounds of East Coast rap in the 2000s, it still does not discount that the strict laws around sampling silence Black voices.

The criminalization of sampling, however, did not stop sampling as a whole. Just like the creation of the artform was made due to innovations, the continuation and perseverance of it also came through with innovations. No more than fve years after the landmark 1991 ruling, DJ Shadow released Endtroducing..... where he sampled dozens of songs throughout the album. He did so by distorting and reshaping the sampled music so much that he hoped people would fail to recognize it.

Enter stage left: PinkPantheress in her bedroom

Before she was PinkPantheress, in high school, Victoria Walker sampled songs on GarageBand and posted her remixes without the intention of making money. In terms of infuences, she cites her mother and “the UK music channel” for introducing her to garage, jungle and drum and bass music growing up, and even nods to K-pop as an infuence. She described her high school music to NPR as “a nice little hobby.”

Unexpectedly, her early career took of in 2021 due to the viral TikTok success of songs she built from interesting samples. PinkPantheress has emerged as a notable fgure in the realm of music sampling,

garnering attention for her distinctive and eclectic approach to blending genres. What sets her apart is not just the range of genres she explores, but also the skill with which she navigates and fuses these elements, creating a sound that defes easy categorization.

The two songs that led her to be a fan favourite — “Break it Of” and “Pain”— both sample UK club classic tracks that were recorded before she was even born. NPR identifed the samples: “Break it Of” uses a 1997 drum-’n’-bass track called “Circles,” produced by an English DJ named Adam F, and “Pain” samples “Flowers” by Sweet Female Attitude, remixed by Sunship.

When asked by iconic music reporter Nardwuar about how she fnds her samples, PinkPantheress replied that she just scours the internet and YouTube. This method has led to some critiques from individuals who accuse her of “defling the classics,” implying a tendency to draw from and tinker with well-known songs rather than explore more obscure or diverse samples.

However, PinkPantheress does far more than rework hits and has demonstrated a nuanced approach to sampling that challenges such criticisms. A notable example is her use of Franz Buchholtz’s “And Yet…” from an outof-print album by his band Signaldrift in her track “Noticed I Cried.” By selecting a sample from an artist associated with a bankrupt record label and featuring unreleased material, PinkPantheress showcases an ability to unearth hidden gems and breathe new life into obscure, forgotten sounds.

She is one of the many people who are trying to reclaim sampling. “People need to realize that sampling isn’t a new thing,” PinkPantheress told NPR, “Sampling is embedded into a lot of genres: EDM, garage, jungle, DnB, rap, hiphop.” Her perspective challenges the notion that sampling should be reserved for a select few and highlights the difculty in determining which artists should have the privilege to engage in this creative practice.

As she continues to make music under the record label Parlophone, PinkPantheress contacts the artists and other record labels to sample their music. While PinkPantheress is recognized as a trailblazer in music sampling, the future of music is a dynamic and multifaceted landscape shaped by various artists and infuences. As technology continues to advance and musical boundaries further dissolve, the exploration of diverse sounds and styles remains a central theme in the evolution of contemporary music.

As my home country Egypt sufers one of the worst economic moments of its modern history, I fnd myself asking whether it’s relevant to have the same conversation I have every other Black History Month: to remind you that Black Egyptians exist. Who cares when we’re all sufering regardless of race, ethnicity, or religious afliation?

Since the ongoing depreciation of the Egyptian pound that began in early 2023, the Egyptian economy has taken a major hit. Prior to the currency devaluation, 30 per cent of the country already lived under the poverty line, many of whom live in the southern parts of the country.

When I speak with my community members back in Aswan — the southernmost governorate of Egypt, which is home to many Black Egyptians — I realize just how bad it is. People I grew up with are forced to sell their jewellery and prized assets to make ends meet. Many I know have had to alter plans for their children’s education, and everyone I speak to is seriously considering immigration.

My childhood is marked by this unbelievable duality, one where I would travel between the metropolis of Cairo and the villages and townships of Aswan, seeing parts of Egypt that most Egyptians don’t even know exist. In my experience, the communities of Aswan live with poorer infrastructure, with few proper chances for education, and are often displaced by the state many times over: either directly, as in the case of our forced displacement to build the Aswan dam, or indirectly, where many of us had to migrate from areas like Aswan to Cairo for our mere survival. To be in Aswan means to be surrounded by resilient people, yes, but to be without basic necessities.

And then I would visit places like the North Coast, where rich Cairenes and all of the state’s

benefciaries have claimed ownership and treat it like some sort of Mediterranean playground. It always boggled my mind because this is the Egypt that they so heavily push in the media, while the other Egypt I know of is entirely omitted from the narrative.

I often think of how radically diferent my life could have been if my grandfather stayed in Aswan instead of migrating to Cairo. Would I have had the luxury of taking my sweet time to get through my degree while switching from major to major? Would I have even been fnancially capable of studying at a university, let alone a decent one? And now, as the country faces total economic collapse, I think of what price the people of Aswan have to pay that won’t be reported on and will be dismissed. Truthfully, the thought of that price scares me. And I fnd myself praying for all of us.

But we didn’t stay in Aswan. The fact that my words about my people’s experience are reaching you means that the sacrifces of my grandpa weren’t in vain — that his resilience paid of. The

Black Egyptian is not some sort of mythical creature nor some sort of docile sage. Black Egyptians sufer once through omission from the narrative of Egypt, and twice by belonging to it. So, for you, across the globe, to be able to sit with what that means for millions of people is a victory: a redemption for my people after years of sacrifce.

I recall the story behind one of my favourite songs: “El Leila Ya Samra.” The story goes that in 1962, Egyptian-Lebanese poet Fouad Haddad was serving time in prison, alongside many communists, political opponents, artists, and thinkers. Among them was Zaki Murad, a Nubian-Egyptian communist activist. Murad was spending another birthday in incarceration. The state of the country after its 1952 coup d’état, as well as the injustice and torture that befell him and his comrades, weighed heavily on him.