I think of CHARM in terms of literal charms — bracelets, necklaces, all that is shiny and pretty. A year ago, I started making jewellery when I came across the supply store, Arton Beads. I would get charms from the store to make necklaces, waist beads, bracelets, and rings. Since I first stepped in the store, Arton Beads felt like a small community of crafters and everyone there seemed to love the place.

When Alexa first told me about her idea for this magazine, I didn’t think of Arton Beads. All I knew was that she was so sure about it, and that made me certain about it as well. I’d like to think that, somewhere in the back of my mind, my memories of the craft store prompted me to say yes just as eagerly.

A lot of the visuals in this magazine are literal charms — but they mean much more than that. Magazine visuals draw readers to the articles. Photos and illustrations are the first thing you notice on the page, and if you like what you see, you might be tempted to read the piece and learn something.

I have learned a lot while making this magazine. I’ve also gotten a lot of help from Varsity alumni who gave advice and shared the lessons they had learned. Technically, this magazine is mine and Alexa’s, but it’s also theirs. I hope they, and the rest of the readers, enjoy it as much as we have enjoyed making it.

— Makena Mwenda, Creative DirectorAll the people I’ve spoken to about making a magazine told me that the feeling would be similar to witnessing your first child come into the world. As I was growing up, my mom told me that she thought of my name, Alexa, because it was the same name that Billy Joel gave his daughter, and she thought that it sounded neat.

But here’s the thing people don’t tell you — when naming a magazine, there’s no unreal, cometo-life moment. The clouds don’t suddenly part, and you don’t continue your day feeling a little lighter. Instead, the process tugs at your brain until it becomes a random word generator. Once you find a catchy idea, you perfect your elevator pitch of meaning and send it off to your management team. So, sorry mom, but I don’t remember where I was when I came up with CHARM; it was just my mind hitting “refresh.”

I do, however, remember the moments when CHARM started mattering to me — when it was no longer abstract, but something I could bring into the world. I was in a creative writing workshop at school, silently judging someone’s poetry collection for not having a coherent theme. I was in the seventeenth-floor lunchroom at my summer co-op, reading the newspaper online and slurping bits of pad see ew. I was riding on a Lakeshore East GO train, praying that fare inspection wouldn’t show up because I was half-asleep and didn’t want to embarrass myself by shuffling through a bundle of receipts in my purse.

I hope that you’ll catch this magazine in these little moments, too. CHARM is a celebration of trial and error, of making mistakes and holding your breath. It was meant to cross paths with you on your shittiest day. Your life won’t be forever altered by it, but you’ll crack a smile and be reassured there’s good in this world. Maybe you’ll even listen to some Billy Joel.

CHARM became fully tangible to me two days before its last editorial production session. My mom had bought me what was supposed to be a daily planner, but it had since become a makeshift to-do list and diary. I was skipping class and counting the number of pages that would be in the magazine. When they added up to 64, I exhaled.

I wrote in the agenda: “I was scared, but now I’m not.” That’s what CHARM has given me. That’s what I hope it gives to you.

I can’t wait to do this all again.

— Alexa DiFrancesco, Magazine Editor

Writer: Jevan Konyar Photographer: Vurjeet Madan

Writer: Jevan Konyar Photographer: Vurjeet Madan

Not to be dramatic, but I would bet the lives of all my loved ones that anyone who swallows a certain amount of alcohol will inevitably consider themselves to be the most

I’m lucky enough to know when I need to shut up, but I’m not lucky enough to be able to close my mouth. This is a liability that I used to think — or hope — that most

After all, navigating social scenes as an adult is confusing. You’re allowed to keep authentic interests, but nobody is there to stop you from forcing them on others. You can talk to whoever you want, but it’s often hard to tell if they’re just listening because they are too polite to tell you that they’re annoyed. In the mess of acquaintances and vaguely familiar faces that surround you once you leave the safe haven — or at least, known evil — of high school, it’s easy to get ahead of yourself and imagine you’ve got

There are signs that you should stop or slow down a particular tangent of rambling — we all know that when someone says, “interesting,” it doesn’t mean they’re interested — but these signs are easy to ignore, or even leave unnoticed. What you have in common with other people only goes so far, and it’s often not long into a conversation before you reach uncharted territory, where you have to decide

whether it’s worth going further. Imagine, if you will, the dreaded inevitability of discussing your majors at a party. This begs the question: what do you talk about if you don’t have that topic?

From your deskmate to someone who happens to share the exact same route home as you, there’s lots of people that we talk to who share common traits with us. In cases like these, there’s nothing to stop you from rambling on about a niche hyperfixation or trying to hone a new sense of humor because you watched a new show recently and one of the characters is “literally you.” In situations like these, it’s easy to force your counterpart into the “you are annoying and I’d leave if I could” camp.

Some are born with the ability to hold a conversation, and some just aren’t. If you’re in that second group, socializing becomes a skill that you need to work on over time, and one that has a Dunning-Kruger effect of its own. Don’t let yourself get carried away — and please, for Leaving Las Vegas’ sake, let’s just stop talking to each other.

I promise I’m not hammered writing this.

Have you ever wished that the love interests you read about in romance novels were real? Have you wondered whether or not you’d be best friends with some of the supporting characters, if you existed in the same world? Do some characters just have a special place in your heart and you fancy rereading books just to revisit them?

There’s a reason why these cherished characters stand out to us or hold a particular place in our hearts, or that we feel anger, love, hatred, glee, and countless other emotions on their behalf.

Our brains are scientifically unable to differentiate between actual people in the real world and the fictional characters in novels.

In an interview with Book Riot, Maja Djikic, an associate professor and the director of the Self-Development Laboratory at the

Rotman School of Management, explained the concept of emotional transportation. Emotional transportation is a process during which we become focused on the events occurring in what we’re reading rather than the outside world. For example, we can lose track of time while reading and become oblivious to the events happening around us. Similarly, perceived distractions — such as fidgeting with our hands or tapping our shoes on the ground — help fire brain connections which increase our attention.

To truly understand why we’re so easily transported into books, we have to familiarize ourselves with the term “alief,” which is a subconscious mental state similar to “belief,” which could contradict conscious thoughts. This concept of alief was developed by Yale University’s Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science and Professor of Philosophy Tamar Gendler.

Gendler points out a difference between belief and alief.

If a person is in a real-world situation, the brain is aware and believes

that this is the real world. The person then responds to that real-world situation. When a person alieves something, their brain is aware of the real world and the imaginary world. However, the person behaves as though the imaginary world and the real world are the same.

For instance, when we watch scary movies, we’re aware of the real world and know that the monsters or villains in the film we’re watching do not actually exist. Despite our sense of reality, we still feel fear; our brains get easily deceived. Since we are in this special cognitive state of alieving, we still feel the same things that we would if the movie was our reality.

This same concept applies to us when we read books. In the real world, if our friend is hurt or navigating a painful situation, we empathize and grieve. Likewise, if a book character we’re reading about is feeling this pain, our brains alieve and we feel these pangs of empathy and grief.

Perhaps, it is because of alieving that we reread the same literature on the

bookshelves, or check them out from the library repeatedly. Since the books we read never change, they can become a tool of self reflection; we can use the books to compare our reactions to certain characters and events, testing our emotional growth. As book critic Patricia Spacks explained to The Artifice, “The stability of reread books helps to create a solid sense of self… it records both the development and the continuity of the self.” Rereading can be a way to track the changes we’ve undergone since being exposed to a text for the first time.

It’s likely that these phenomena explain why books are so special to many people around the world. But it’s also likely that we’ll never truly be able to measure the magic of literature. To some, books are nothing more than words on a page; to others like myself, they’re extraordinary enough to transport us to realities far more fantastic than our world.

When I was little, as a Polish Canadian, my relationship with traditional Polish culture was basically synonymous with my connection to Catholicism. All of my family’s gatherings were centred around religious holidays, Polish community activities were often hosted in churches, and the only time my entire Polish family came to Canada was for my Communion.

None of these details should be surprising. Today, around 87 per cent of Poland’s population is classified as Catholic. Mieszko I, the first ruler of Poland, adopted Catholicism as the state religion in 966 CE. That same year is used to mark the beginning of Poland’s history, and the Catholic Church heavily participated in the celebrations for our country’s millennium in 1966.

But the borders of Polish faith have never been as strict as some might like to think. Though my relationship with Catholicism was always complicated, I loved celebrating holidays with my family because of the sense

of whimsy that permeated these occasions. For example, there’s an odd tinge of magic to the Easter tradition of dressing up a basket, packing it with food, dressing up in your Sunday best, and waiting for a priest to bless that food with a bundle of straw soaked in holy water.

Later in life, I would make jokes about always being hit with holy water because the priest somehow knew I was queer. But, when I was a kid, those droplets falling on me felt like a rebirth. I would walk back out into the fresh spring air, my chest lighter. I would sing along to pop music during the car ride home, more prepared to tackle the coming year.

My childish sense of whimsy wasn’t unfounded, of course. Like most millenium-old communities, Polish people didn’t adopt Christianity without a fight. There were a number of Pagan uprisings after Poland’s conversion, and most peasants still adhered to the polytheistic Native Slavic Faith Rodnovery as late as the twelfth century.

The result of this steadfastness is that many of those Pagan traditions bled into Christian ones, creating a unique form of Christianity that is more localized than anything else. Catholicism may have been more amenable to this than other Christian denominations; it focuses on saints more than most others, leading to what could be interpreted as a unique type of polytheism.

Many rural Polish communities had small, crude statues of saints — most often the Virgin Mary — built so that locals could pray to them on days when they weren’t able to walk long distances to the nearest church.

When I interviewed her for this piece, my grandmother, Zofia Anielska, insisted that praying to these statues was never interpreted as polytheism because Catholics had a mandate to pray to all the figures of their religion. My grandfather, Marcin Anielski, who sat with me as I spoke to my grandmother, added that all the figures of the Catholic faith are intertwined. These

prayers didn’t cancel each other out but rather reinforced each other.

Some smaller religious occasions focused on these statues would be contrastingly more ritualistic and playful in nature. During May, as a child, my grandmother would meet with a group of friends and they would pray, sing, and dance around one of these shrines, joking in between sessions. She enjoyed these activities as social events more than anything else.

There seems to be a duality to my grandmother’s faith, just like there was to mine. One year, while returning from Christmas-day mass, I told my family that every time I went to Polish church, I felt like I couldn’t smile for the hour before, during, or after the service. Though my family obviously found this to be very funny, the kernel of truth to my mildly overexaggerated story is that mass itself can often feel severe, rigid, and unforgiving — in stark contrast to my more light-hearted memories of specifically

Polish religious rituals.

This is the part where I make an easy comparison between my dual experience of Catholicism and the duality presented between the Old and New Testaments. Like those masses, the Old Testament God is unforgiving yet supposedly fair. On the other hand, the New Testament God is loving and merciful. Jesus seems to have resolved humanity’s “daddy” issues.

There are also less holistic ways of integrating other beliefs into one’s faith than adopting a Pagan group’s religious practices, such as by holding on to a vestige of belief that steps outside of or in opposition to their faith. Though my grandmother’s family was never particularly superstitious, there were always things that sunk their teeth and claws into small communities. This included

some well-known superstitions — like not crossing the street behind or alongside a black cat — as well as lesser-known ones, such as sitting down for a minute if you ever return to your house for a forgotten item.

Intellectually, my grandmother doesn’t believe in any of these superstitions, but she still follows many of them, just in case. She explained to me that believing such silly trifles occasionally leaves her feeling a little guilty for showing disrespect toward God.

Either way, the echoes of paganism are prominent in many corners of the Catholic faith, which might be why the long-forgotten Rodnovery has seen somewhat of a resurgence. Today, there are between 5,000 and 8,000

Rodzimowiercy — tiny numbers given that Poland has around the same population as Canada — but their ranks have gradually been growing since its first modern adherents denounced the Catholic faith in the early nineteenth century.

While Poland’s conservatism and dedication to Catholicism mean it’s unlikely that the religion will ever truly catch on again, I hope more Polish people take an interest in these traditions as cultural practices and enjoyable ways to connect to nature and the past. Who knows, maybe if we continue to embrace diverse pagan and cultural traditions, our lands and people can become a little more magical than they already are.

A hotdog vendor smiles. He says, “What? Right.” Behind me, someone wearing a dark peacoat is playing a Peaches song. These flashes were the only detailed looks I could catch of Toronto’s Rebel nightclub.

Rebel is a large concert venue and nightclub that resides near floatings of basin water on the Polson Pier. That night, it would be electroclash musician Peaches’ last Canadian stopover on her 2022 Teaches of Peaches Anniversary Tour. I’d just flown back to Toronto and had heard from a group of friends that clubbing was a great way to find a scene you’re interested in — but all Rebel appeared to be was people spitting on one another.

Inside, it was so cold that I saw mists of saliva floating in the air long after someone

spoke. This is why I opted to keep my mouth closed and never responded when a stray foot brushed against my leg. Of all the nightclubs I’ve visited or witnessed through the media, none were like Rebel. Rebel was like walking into rooms of sound. Every corner contained its own sound, as if two records were playing at once.

I put myself through this discomfort for Peaches. From what I’ve witnessed, Peaches is one of the few live performers who will be thrilled to tackle any genre, to play a sound on any makeshift instrument. In an interview at Curly Mess, a venue in France, she once described her music as “a big mess that turns into something” — it’s clear that her songs are inspired by what she’s heard.

I first heard of Peaches at a family friend’s block party. Strangers typically frequented these parties; at that one, there

were two of them, whom I approached to ask what music they were playing. “Peaches,” an older woman responded, asking me if I’d heard her music. She handed her phone to me, and the second person grabbed my shoulders in a push. I was led to an alleyway with a row of garages, following their fingers to the street.

“This is where Peaches lived!” she said. In the music video for the song she was playing, Peaches rode a bicycle along the same alleyway, executing wheelies. The woman told me that Peaches had recreated the routine on stage with her old bicycle. At that moment, standing where Peaches apparently used to be, I thought that anyone who sang on a bicycle was worth seeing live.

I stayed on Ticketmaster’s website until my mother got home from work. She didn’t acknowl-

edge me; instead, she took out a small container of baklava from the fridge and started eating it with her gloves still on. “Already got them,” she said.

The tickets were there, in an email my mother sent me. The message said, “No need to ask,” and was written entirely in pink font. Months later, I stood at Rebel, in the windbreaker jacket that she bought for me, hiding its large label behind my arm. My legs were shaking and it was raining; the coat’s large puffs absorbed the water, and whenever I shifted my weight, it came back on my body.

There is a ripped toilet on the road in front of the club. A man in bicycle shorts taps on the porcelain, and the seat cover slams down. He sits and crosses his legs. “It’s really cold,” he says, allowing another man to pretend to flush.

Closer to the club doors, a

man passes me a Peaches’ balloon that has been thrashed by dancers. “Seeing Peaches?” he says. Apparently not for some time, but I’m let in eventually.

Two men in raincoats and bucket hats stand on top of a drum kit. Another runs to an 808 machine; it’s obvious that he’s made this trip before because his skin is so shiny that it looks like it was squeegeed. A lace spread is covering what appears to be two floor lamps on stage; when this man whisks it off, two microphones wobble loudly. He starts to sing into one and waves it close to his chest.

I attempt to focus on the man performing, but my view is interrupted by a barrel-chested stranger sucking rock candy from a bag. He pelts the audience with Hershey’s Kisses. Every piece of his chest hair sticks out of his fishnet shirt; when he turns, it looks like confetti

falling. I’m afraid some of the candy he threw might stick to my jacket, so I move closer and closer to the edge of the floor until I can’t see him.

I’m exhausted and confused. Too many objects are hanging off the stage and too many sounds are crashing on me. It is impossible to move without making physical contact. It hurts to turn my body, and I don’t know why my arm is wet.

The man singing walks off the stage and lands on someone. Peaches shambles to take her place; she’s wearing a pink-fleece robe and is holding a walker and a purse. She searches through her purse and pulls out her own microphone, then grabs the 808 machine and turns a knob. Someone starts to groan. “Oops,” she says, “That’s my mom. She’s here in the audience tonight.”

Peaches faces the audience

and cracks her neck. A bass drum buzzes. Peaches’ costume makes her movements top-heavy and slow, but I can tell from her body language that she is dancing. Peaches runs to every corner and does the splits. The audience seems fascinated by her movements; when she points to the back of the club we all turn, not knowing that she was drawing an invisible line for her dancers to follow. I’m not dancing, but I try to get into the best spirit I can with a wet windbreaker on. Peaches tosses parts of her outfit offstage and licks the microphone.

“Ladies and gentlemen, The Peaches’ Shit Band!”

The Peaches’ Shit Band consists of two young women who play drums and electric guitar. One of them pushes a drumstick into Peaches’ piled hair, and she performs the rest of

the show with it on. They ripple through ten songs in fifteen minutes. Peaches is wearing so much makeup that when she moves her head the rest of her face fails to go with her. Peaches hurls the microphone into the crowd. She shaves her fringe jacket down the middle with a sharp end of a mic stand and gives it to a dancer who kisses her on the cheek. She waves to her mother and leaves. I’m doing a faster shuffle; I am probably more happy than I’ve ever been listening to music.

A month ago, I was sitting with my godmother in her cottage on Racoon Lake. I wanted to hear something I thought I misremembered, and the way I could say this was to talk about Peaches. “I was in the theater program with her at York in the 1990s,” she told me. I mentioned the pink robe. “Sounds like Peaches,” she replied.

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of homophobia.

Part of me always gazed with envy at an existence behind a white picket fence. In many ways, I got as close to the fence as I possibly could; I had a boyfriend that I cared for deeply and two parents that were quietly relieved I wasn’t gay. When my hands

with my sexuality minimally involved experimentation, and mostly involved sitting with my thoughts.

In my freshman year of high school, from the safe haven of my childhood bedroom, I realized I could be queer. In grade 12, after years of pacing back and forth on the carpeted floor of my English classroom, I came to the conclusion that I was bisexual. It took me until this summer — while working on the North Shore of Lake Superior for four months — to realize that I was a lesbian. I sat with myself on the Canadian Shield, on some of the oldest rocks in the world.

I sometimes look upon my queer friends with envy. I listen to their stories about how they were so comfortable with their sexuality that they came out when they were merely nine or 10 years old. I struggled with the prospect of being a lesbian for most of my life because I didn’t want it to be true. Even now, I look at my hands and I’m so gripped with fear and exhaustion and internalized homophobia that sometimes I don’t even really want to be queer.

So what do you do when you realize that after you come out, you’re signing yourself up for a life of otherness, of tougher conversations than you have to deal with, of constant flux? You don’t. I managed to convince myself that I wasn’t a lesbian so well that when I did eventually come out, I saw a constructed life that was never mine, and dismantled it heartbreakingly piece by piece.

Strangely, the realization of being a lesbian didn’t hit me hard. The sheer amount of time I spent grappling with the concept gave it a sense of familiarity like that of an old friend; a friend that just happened to spark an identity crisis whenever we met. But coming out to people — putting that part of myself out into existence — hit me like a ton of bricks. In one split second, a truth about myself that I had spent year after year running away from finally caught up to me. My life as I knew it ceased to exist.

Involuntary realizations knock you off your feet; you’re on the floor trying to recollect what happened, and all you can see is the world you previously thought you knew crumbling before your eyes.

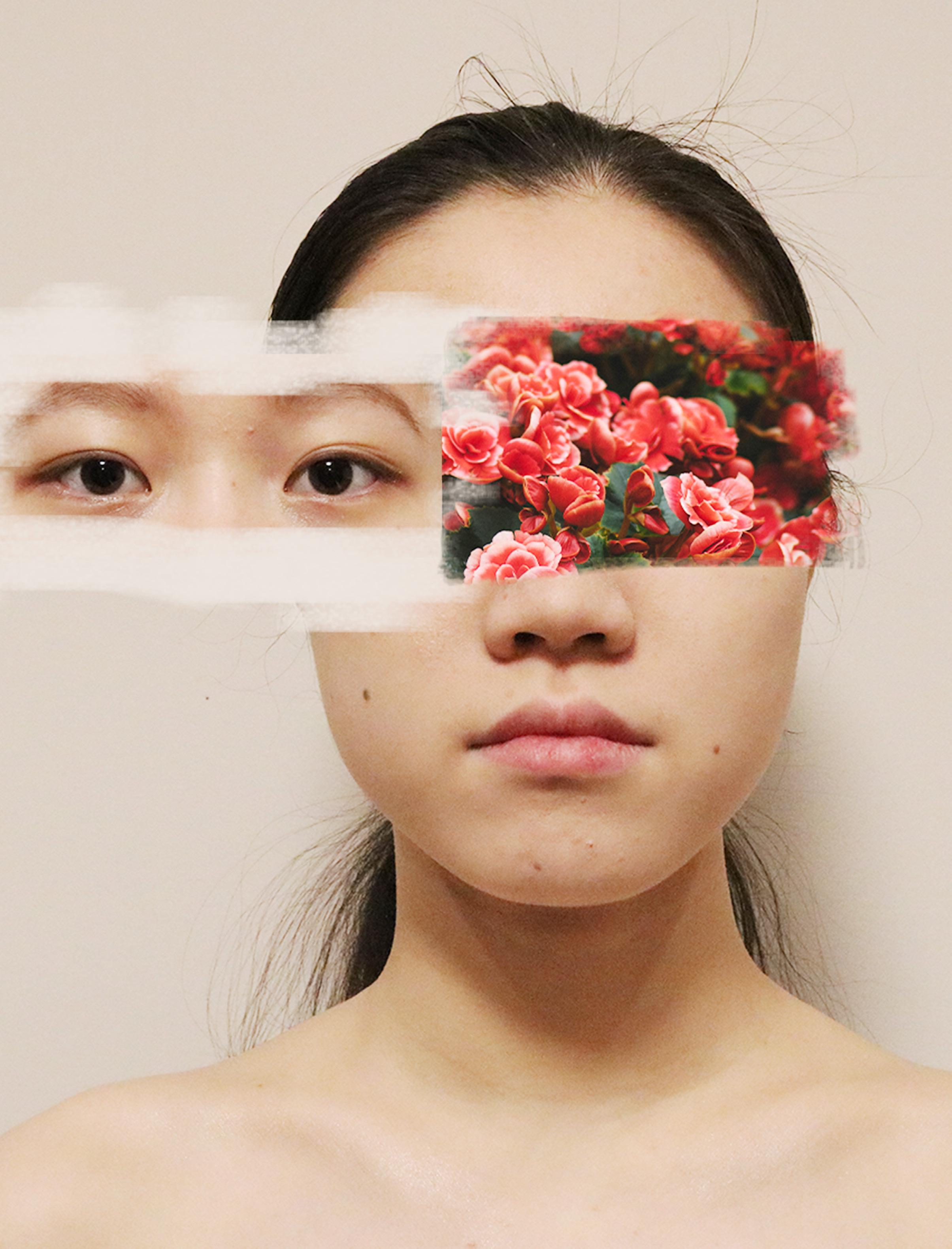

I’ve created a metaphorical chrysalis to undergo a necessary metamorphosis, but realize that my body must disintegrate into a mass of mucus for that to happen. Right now, I’m scared of perceiving myself; I’ve undergone so much change in such a short amount of time that I don’t see myself as Alice anymore. I see someone who had to hurt others to live in a new reality. I emerge from a chrysalis, but look back in horror at a pair of damp wings that sprouted off a body I no longer see as my own. Presently, mornings consist of looking up at my ceiling and asking, “How the hell am I going to get through today?”

Content warning: This article contains detailed descriptions of anxiety disorder, panic attacks, and dissociation.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how little I did to be born onto this Earth and how prominent it feels to be human. Sometimes, existing feels consuming. And it seems that, recently, it is always consuming.

Here’s the reality that I was faced with: after taking into account the chances of our parents meeting, of them having

sex, of the sperm successfully meeting the egg, and for that interaction to result in pregnancy, the odds of each of us existing is one in 10 to the power of 2,865,000. That’s a number too huge for our minds to process; a number that proves that, statistically, we shouldn’t exist.

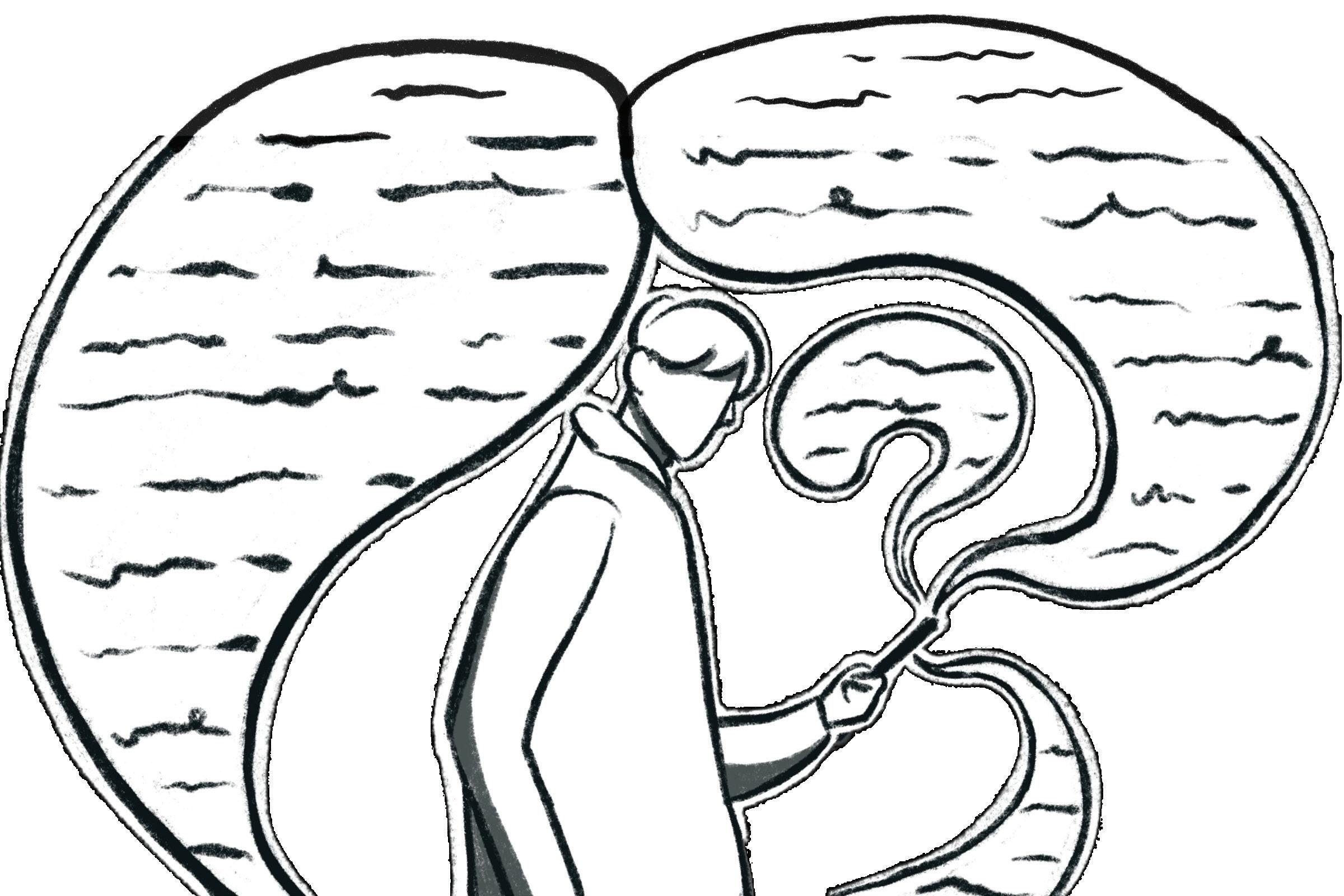

Yet, somehow, we do. The nerves in our brains travel at speeds of 268 miles an hour; our bodies follow their signals subconsciously. But what’s arguably more fascinating is everything that we’re aware of and all that we’re able to think about, argue, and debate. This conscious mind is one of our world’s unknowns; an entity

that scientists and philosophers don’t yet seem to agree on. My world came to halt one Monday evening when the weight of this truth finally settled in.

I was working late one evening, waiting tables at my hometown bar. I think I was in the process of cashing out a customer — truth be told, this episode was so panic inducing that I don’t exactly remember — when I suddenly got hit with a cold sensation. It launched me into a frenzy of fear and confusion — I had visited this bar weekly for the past three years, and yet I didn’t recognize where I was.

I had previously been diag-

nosed with anxiety disorder and had since accepted that my body is prone to panic attacks. But this time was different: I was disconnected; my movements were unfamiliar, my voice sounded odd, and my vision was distorted. On the walk home, I cried to my sister; back at my apartment, my roommate consoled me. For hours, I sat cross legged on a matted rug, trying to put into words the feeling that I was experiencing.

“I’m not real.”

This feeling lingered for two days after. I went on a run, unsure of how my legs were moving, fearful that I would suddenly forget how to send

signals through my body and that they would suddenly stop working. When my panic subsided, I forgot about it: it was an exceedingly bad panic attack that had run its course. I would breathe deeply and journal and it wouldn’t happen again. It couldn’t happen again.

This summer, I visited my father back home in the United Kingdom. I took a walk with my grandmother in the woods that I grew up in and knew so well, that, once again, I became cold. I wasn’t sure why I was anxious, but I sensed my body was telling me there was something that I hadn’t addressed — that I was neglecting an anxiety that ex-

This episode had opened a window: I now had these thoughts and I couldn’t forget them. So, back in Canada, I made a plan. I began to consider a shift in perspective; perhaps I needed to confront my fears and become more in touch. More observant. More contemplative. More and more.

If you’re a philosophy buff, you might be tempted to identify my initial thinking as existentialism, which emphasizes individual responsibility to create life’s meaning rather than relying on a higher power or religion to do it. The term existentialism was coined in the 1800s by Søren Kierkegaard,

existentialist; I’m saying that studying their way of thinking can be beneficial. Consider that existentialism encouraged me to finally break that window — instead of trapping my curiosity, I would foster it. Or I would try to. Here I was, afraid and incognizant, but alive.

Zoom out I wish that I could write to tell you that I’ve completely stopped letting myself become overwhelmed by all that once consumed me. This isn’t the truth; rather, I’m learning to sit with myself. I don’t think the point of life is to be still all the time, but I like sitting. Not to the extent that it induces stress and fear, of course, but enough

to breathe, focus on my surroundings, and remind myself that I’m lucky to exist. I’m lucky to be real.

I’ve created a nickname for these moments, my little time outs during a surge of self-awareness. They’re my ‘zoom’ moments. I can choose to ‘zoom in,’ to examine the problem that I’m struggling with in more detail through research until the worries subside. Just as easily, I can choose to ‘zoom out’; I can sit in silence, I can focus on my breathing, and I can select a neon object in the room and stare at it until I’m comfortable.

When I researched my symptoms, I found that what I was experiencing could be dissociation, a possible symptom of anxiety

isted in a body that, at that moment, I didn’t accept as mine. The feeling lasted for weeks; I felt that I had betrayed myself and I couldn’t make it go away.

Zoom in

After my walk, I was silent. I spent time in my head and on Google, searching for an explanation for why my body was so anxious. I felt that I was thinking faster than ever before, firing questions at myself about myself that I was inadequate to answer. I felt awe and dread — awe that I knew how to move my arms, blink, breathe, see, and speak; fear that I would suddenly lose all these abilities if I took them for granted.

a Danish philosopher. The movement emerged from three pillars: phenomenology, a philosophical movement that encourages us to understand the world and its tools from a first-person perspective; freedom, which outlines that we bear the responsibility for who we are and the decisions that we make; and authenticity, by which we refuse to succumb to external pressures that compromise our personal freedom.

I’m not saying that I’m an

disorder. When a person experiences dissociation, they can feel disconnected from their surroundings or themselves.

This reaction temporarily alleviates potentially overwhelming emotions, as traumatic memories. It may also temporarily reduce feelings of shame.

But disassociation isn’t a healthy long-term solution; it prevents healthy coping and processing. It’s vital that people who’ve experienced dissociation similar to mine discuss their experiences with a medical professional.

I’m not a medical professional, reader, and there’s no universal band-aid to fix anxiety. While I can offer you my solutions, what works for me might not work for you. If you’re like me, I want you to find what works for you so you too aren’t overwhelmed by dread.

If you’re like me, don’t be scared of the label. I’ve often felt that the world tells us to place a label on all that we see, track our potential symptoms, and

find a diagnosis. As frustrating and scientific as this process can be sometimes, it’s truly the only way to objectively know whether or not you need help.

What if you find a corner of the internet with the right list of symptoms? What if the prognosis isn’t as sinister as you’re anticipating? It can be isolating to navigate dreadful feelings and to convince yourself that you’re the only one thinking about them.

Now, when I get anxious or introspective, it helps to remind myself that a lot of the things that I don’t know, a lot of other people don’t know either.

If the average person were to deeply consider the depth of our brains, all our confusions, and unknowns, they also might spiral in dread. The truth of the matter is that we’re all different — while some of us become philosophers and are excited about delving into life’s inquiries, some of us can’t spend a moment without feeling like we’ve lost our minds.

Simultaneously, it’s true that we’re all existing at the same time. Our minds are working in curious ways: our brains tell us to breathe, to think, and to not worry about thinking. Our bodies are intertwined with worries and fears and love and living.

Yes, I’m petrified of failure, success, and the moments in between. I often feel over-

whelmed, but I’ve found a sanctuary in knowing that I’m not alone in my fears. While these moments are scary, the coping mechanisms I’ve found make me feel safe; through them, I can learn a little more about the world if I choose. And, if I opt to focus on my own little world instead, I know I’m not losing myself. I’m becoming myself.

Every other Sunday or so, twenty drivers climb into the world’s fastest cars and go motor racing, chasing each other through twists and turns at breakneck speeds in search of victory. To the uninitiated observer, Formula One may seem to be an incredible waste of time,

lar by the year, and perhaps for a good reason. The racing is thrilling, the show is spectacular, and the drivers and crew make for a delightfully entertaining cast.

Lights out and away we go Formula One’s most obvious appeal is in its racing, which

ly unpredictable during each round. Each track presents new challenges and opportunities, demanding a different set of skills from the drivers. Monaco — where it is difficult to overtake another car due to the narrow track built upon winding city streets — demands a strong performance

made a return to the F1 calendar, features steeply banked corners at turns three and 14; Silverstone includes the iconic three-corner combination of Maggots to Becketts to Chapel and demands great skill in wheel-to-wheel racing. The machinery and personnel also play a part; a failure or malfunction of any part of the car or a human error made by any member of the team — a slow pit stop, a wrong strategy call, or a lockup — can take a driver from first to last in a matter of seconds. The competition is anything but repetitive; anything can and might happen on a fateful enough Sunday when races

Formula One cars are at the pinnacle of engineering perfection. Each team has a dedicated crew of engineers working tirelessly to optimize the body of the car and the power unit, ensuring that their machinery is both quick and reliable. These behind-thescenes experts pore over every last detail, scrutinizing data from telemetry and simulations, perfecting torque transfer and brake balance. Modern formula cars are gorgeous, dizzyingly quick, and exorbitantly expensive, designed to shave

pensive, designed to shave off every last thousandth of a second to gain any advantage possible. Formula One is the ultimate partnership of man and machine, demanding every last inch of performance from both the driver and the car.

As much as the focus of Formula One tends to be on the drivers on track, the strategy calls from the team on the pit wall play a massive role in deciding the outcome of each race. Calls made by these strategists depend on weather conditions, a driver’s current position in the race, and even the tactics employed by other teams. Teams have to ensure that their drivers are on the right kind of tyres for the weather and that they are not on the same set of tyres for so long that the rubber begins to degrade, but must also ensure that as little time is wasted in the pit lane as possible, all while fending off rivals for positions and championship points. Seven-time champion Michael Schumacher’s win in the French Grand Prix in 2004 is a modern strategy masterclass; his Ferrari team was expected to call him to the pits three times, but his strategist devised a plan for a four-stop race, which deceived his rivals and allowed him to use his car’s superior speed in clean air to take the win, despite trailing for much of the first two-thirds of the race. Strategy calls — both brilliant and regrettable — are a defining part of the sport; the garage is where championships may be lost and won.

Lights, camera, champagne

The sporting aspect of Formula One is a display of speed and courage; everything else on race day is a showcase of engineering brilliance and

quick-thinking strategy. What many fans quickly realize once they begin to watch the sport is that the competition has also long been a show of splendour. The races take place in dazzlingly unattain able venues all around the world and famous, important guests are present at nearly every round.

Formula One is perhaps the most global spectacle in the world today. The sport origi nated in Europe in 1950, with six Grand Prix races across the continent that year, and quickly expanded to include tracks around the world. For mula One’s jet-setting crew now makes its rounds to some of the most glamorous and unattainable cities in the world — from Singapore to Monaco and everything in be tween — bringing the show to fans on five continents over the course of 22 races. The international appeal of the sport is second to none and allows fans a glimpse at lav ish locales around the world in addition to the racing.

Formula One is a play ground for the wealthy and powerful, with celebrities be ing a constant fixture at rac es since the very beginning. Heads of state, stars of the screen, and accomplished athletes from other sports are often among the fans in the grandstand, taking in a few hours of thrilling motor-racing and smiling for the cameras that spot them in the crowd. A unique sense of fame — an old-fash ioned, golden-age, gladia torial brand of stardom — is bestowed upon the drivers who spend their weekends dancing with danger, with the top finishers of each race awarded with shiny trophies and sparkling champagne for their valiant efforts. Outside of the track, they can be spot ted at Met Galas and Ballon

tremely popular among fans. Vettel, who announced his retirement earlier this season, has grown to be an eager champion for gender equality and climate justice. Alonso, the oldest driver on the grid and two-time champion and absolute racing fanatic, has shown no signs of slowing down. The most recently crowned world champion of the 2022 drivers is 25-yearold Verstappen, who likes to spend his spare time playing racing and FIFA video games and doting on his two cats named after Monagesque clubs. Previously hotheaded and honest to a fault, he once quipped irreverently about headbutting interviewers and about the time his father left him at a gas station in Italy as a boy, but with two titles now under his belt, he seems to have matured into a more appeased and humorous version of himself.

Other fan favourites include Daniel Ricciardo, complete with his constant cheeky grin, and Ferrari’s golden boy Charles Leclerc, who fancies a banana costume or an impromptu piano performance when he’s not vying for race victories. Each driver has a unique backstory, personality, interests, and ambitions; with twenty of them on the grid, there is a driver for every fan to look up to, and support.

For all its faults — the burnt diesel, the absurd danger, the seeming triviality of it all — Formula One retains an irresistible, irrefutable appeal. From the engineering magic and snap-decision strategies to the glittering venues and cosmopolitan celebrities, the world’s favourite motorsports series has a charm like no other. The next time you find yourself with nothing to do on a Sunday afternoon, tune in for a race — I promise, you won’t be disappointed.

Writer: Safiya Patel Illustrator: Jessica Lam Photographer: Jadine Ngan

Writer: Safiya Patel Illustrator: Jessica Lam Photographer: Jadine Ngan

I grew up oblivious to the patriarchy.

Growing up in a house with two sisters and loving and proud parents who have always supported my every goal, I never had cause to believe that there was a systemic reason for why I could not achieve anything I wanted to. My mom worked part time as a physiotherapist and my dad ran his business from home — as far as I knew, a woman could do anything a man could.

As I grew older, the warm bubble around my little corner of the world slowly began to fade away. At school, I read books about young girls in Afghanistan living under the Taliban regime, young girls who were forced to cover their hair and pretend to be boys just so they could leave their homes. It was then that I began to realize that the safety to which I was accustomed was not universal. I began to understand the privilege that living in a Western country afforded me.

I came to appreciate the values of the country whose passport I held, and beamed with pride whenever Canada’s multiculturalism was mentioned. Here in Canada, I could

dress however I wanted. In Canada, my jejune perspective told me that I could become whomever I wished.

But when I did start dressing how I wanted, when I started covering my hair with a headscarf — as my religion, Islam, stipulates — I didn’t feel the same warm acceptance that my bouncy ringlets had enabled. The offhand comments laced with disdain, the stares and whispers I became a target of, shattered any pride I had in my country.

Living in the Western world might indeed afford me certain privileges, but my identity as a Muslim woman mitigates these privileges.

Rejection hurts — as anyone whose crush has ever snubbed them should know. And it hurts all the more when it comes from a place to which you have only ever given love.

As the solace of the Western world faded away, I realized that my illusion stemmed from a very small corner of the world that preached freedom but then created a rigid definition of it. My world was small and safe; every step I took away from it made me realize just how small it was.

When I stand in front of the mirror every morning, I tie up my hair in a way that I know will elicit tangles and headaches, then hide it under a headscarf. It’s not always easy to know that I am making myself just a little less beautiful. But I make this choice every day because I want to be more beautiful in

God’s eyes. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as the saying goes, and I have made a choice regarding which beholder’s opinion I value.

Islamic guidelines ask women to wear a headscarf and guard our modesty in both how we dress and act. This modesty is called “hijab” — an Arabic word that means “veil.” While hijab commonly merely evokes images of the headscarf, it encompasses more than that. It represents the general idea of carrying oneself in a modest manner.

Regardless of any cultural or personal connection a woman has to her hijab, the underlying reason we choose to wear it is because God asks us to.

If you ask hijabi women — those who are free to make this decision without the encroachment of political or cultural values — why they wear hijab, you will get a myriad of answers. Some will say it frees them from being a slave to Western culture, which reduces a woman to her body. Others, that they take pride in displaying this outward symbol of their belief. Others still, that they value their modesty.

My hijab is simply a symbol of the strength of my belief — and a tool to hide bad hair days. But I am not the spokesperson for all hijabi women. Although we have the same underlying beliefs, our personal reasons are just that — personal. They concern only ourselves and God, not our fathers, not the old man across the street yelling at us to go back to our country, and certainly not any political leader.

While the ruling parties of countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia politicize women’s modesty, there is no basis for this in Islam. By no means does hijab involve external accountability; Islam gives neither men nor political

authority figures the right to force a woman to wear a headscarf or punish her when she doesn’t.

In fact, Muslim men must observe the modesty of hijab by restraining their eyes even before women cover their hair. Instead of condoning or facilitating oppressive institutions such as Iran’s morality police, Islam does the opposite. If you see that someone is not observing the hijab, you don’t get to chastise them. You simply look away.

In contrast to Iran’s morality police, Islam’s morality police involve only one’s own conscience and one can only police their own modesty.

“There is no compulsion,” the Quran specifies, “in religion.”

This lack of compulsion, the freedom to act according to one’s own will, is also characteristic of the culture in modern Western society.

dom of choice, to celebrate the acceptance of and displaying one’s identity.

However, this liberalism is inherently paradoxical — such acceptance of different identities and beliefs and values exists only within rigid, well defined borders. In an interview with The Varsity , UTM Political Science Professor Katherine Bullock explained this phenomenon: “Since religion is often considered dogma and not reason-based, and tradition and customs are seen as chains inhibiting individual freedom, liberal culture often looks askance at religiously-motivated dress such as hijab.”

The perpetuation of the idea of these chains is illustrated through the politicized, oppressive construction of the hijab in the Islamic Republic of Iran, which has led to the death of Mahsa Amini. In response, the world has erupted in outcry against the Islamic Republic of Iran’s

Iranian women are removing their hijabs in protest of the regime’s regulations surrounding the headscarf and publicly burning their hijabs to symbolize their rejection of and rebellion against the regime. Women around the world are cutting their hair to display solidarity with Iranian women.

Such a movement is both necessary and noble, but the nature of the subject allows for misguided — even Islamophobic — rhetoric surrounding the religious symbol of hijab. The hijab is a visual symbol of the Republic’s misogynistic regulations. It is also, first and foremost, a symbol of faith for Muslim women around the world.

French actresses such as Marion Cotillard and Charlotte Gainsbourg are among those who have cut their hair to make a statement against a regime that makes a woman’s body the subject of public debate and anti choice regulations.

tion is fitting for France, where laws similarly restrict a woman’s decision to wear

Such inconsistency is not unusual in the Western world. As Bullock outlined, Western people “may feel a sincere desire to help Iranian people

poses hijab on women to the point of beating a woman to

ued, “The impassioned rallies and reactions ignore the flip side in their own countries, where women are banned from wearing hijab or niqab.”

Bullock concluded, “One must support a principle universally, not selectively.”

Ruling parties of countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia have imposed restrictive laws on women and are involved in horrifically violent practices surrounding women’s modesty, which have time and again received criticism, and rightfully so. However, not unlike how Iran transforms the hijab from a personal value into a political statement, Western countries impose legal restrictions on the use of the hijab — in the name of liberalism.

Laïcité, France’s constitutional principle of secularism, works to legally separate church and state and claims to adopt neutrality toward religion. However, the country banned wearing visibly religious symbols in professional settings in 2004, and wearing religious face coverings — such as the niqab, an extra layer of modesty that some Muslim women choose to wear — in any public setting in 2010. Several other European countries have followed suit, with Switzerland being the latest to adopt the latter policy in 2021.

These restrictive laws are not foreign to our side of the ocean; in 2019, Québec introduced Bill 21, which prevents public sector employees

from wearing any religious symbols at work and denies government services such as health care and public transportation to anyone wearing face coverings for religious reasons.

The crux of these laws is that religious values should not bleed into government institutions. Never mind that a giant gold crucifix hung over the speaker’s chair in Québec’s National Assembly at the time the bill was passed.

Such legislation imposes restrictions on religion in the name of protecting secular governing, but in fact fails to separate the two, instead weaving them together by bringing politics into religion. Governments have found a loophole to paradoxically dictate the practice of religion under the guise of maintaining neutrality toward it.

Western governments’ practice of appointing themselves arbiters of religion is fruit — albeit of a less violent variety — from the same tree as Iran or the Taliban regime dictating what women must wear.

As a child, I found safety in the glamour of Western liberalism. Now, however, I chafe at any discussions of feminism, because such conversation requires a reference point and thus inevitably demonizes conservative

ideals, such as those of my religion. By equating the religious symbol of the hijab with political control of women’s modesty, the same rhetoric that uplifts the acceptance we preach in North America leaves little room for accepting religion.

While Afghan soldiers or British colonizers need not have ever touched a headscarf, the hijab nonetheless became a weapon in their arsenal; they transformed it into a symbol of the enemy’s brutality that they claimed to be fighting to eradicate. By becoming the antithesis of the free woman, the hijab became the weapon of Western governments.

From the United States to Canada to France, our governments opine on and excavate the inner workings of oppressive laws of other states, but they only do so when politically convenient.

Take, for example, the US-Afghanistan war. In 2001, the United States’ then-President George W. Bush affirmed, “The central goal of terrorists is the brutal oppression of women.” However, Bush’s status as a women’s rights’ champion is dicey; while the American presence in Afghanistan did indeed enable Afghan girls to go to school and criminalized violence against women, his administration primarily focused its liberation of

oppressed women only on women living in Afghanistan.

Meanwhile in Saudi Arabia, women experienced a rivalling repression; male family members were ‘guardians,’ and had the de facto right to dictate a woman’s every step outside of the home — including whether she could even step outside of the house — as well as to exercise violence against female family members, and even file legal complaints of “disobedience” against the latter. Women could not drive and were denied custody rights.

But United States’ presidents have long adopted an effusive response to Saudi Arabia’s activities, including overlooking this oppression to maintain ties with the kingdom; such a response fosters military cooperation and preserves the States’ access to oil.

And when Britain invaded Egypt in the late seventeenth century, the first Earl of Croner, Evelyn Baring, wrote that this occupation was a quest to free Egyptian Muslim women from Egyptian men’s supposed ideals of repression, allowing them a chance at a civilized life. But Baring was fickle in his advocacy for women’s rights, apparently restricting that advocacy to countries whose values differed from England’s; back home, he was the president of the Men’s League for Op-

posing Woman Suffrage. Bullock’s assessment of such cherry-picking activism is perfectly pithy: “Western governments, like all governments, usually place trade interests and security alliances ahead of a uniformly applied principle of human rights.”

It is easy to point a finger at our southern border or criticize what we find in the annals of Europe’s colonization, but Canada is not a stranger to this inconsistent solidarity. Even the country’s response to the recent surge of global ongoing protest illustrates the Western practice of fighting for women’s rights only when the subject of ridicule has enemy status.

In an interview with The Varsity, U of T Faculty of Law Professor Anver Emon contrasted Canada’s lighting up the parliament with the colours of the Iranian flag to show solidarity toward the women of Iran with Québec’s Bill 21: “The largely silent response to the illiberal-cum-authoritarian Law 21 in Québec, when juxtaposed with protesting the Iranian government, is not about liberalism, or supporting women’s choice.”

“Rather, it’s consistent with a foreign policy that has, since 2011, demonized Iran,” Emon explained. Iran’s repressive laws indeed call for challenge and dissent but, as Emon noted, Canada’s own political agenda, and not the Republic’s cruelty, is the impetus for Canada’s show of solidarity.

After the United Nations Security Council imposed sanctions on Iran in response to the country’s nuclear program beginning in 2006, Canada was among the countries that followed suit. In 2010, under the Special Economic Measures Act, Canada tightened existing sanctions and, beginning in 2011, amended the act to im-

pose the general prohibition of import and export with Iran.

These sanctions and their exacerbation through the 2011 prohibitions, Emon explained, “contribute to devastating [Iran’s] economy,” and thus also “Iran’s people.” As such, Canada shows solidarity with Iranian women while contributing to the suffering of these same people.

In Emon’s words, “Lighting up Parliament with Iranian colours in solidarity with the protests is hypocritical, costless, and politically convenient.”

Iranian women need more than a merely performative fireworks show; they need people in power to hear them, to take action to remove them from their suffering, to free them from oppressive political power.

And contrastingly, Muslim women do not need a white knight — no pun intended — to ride into our lives and emancipate us from the shackles of our religion or from a religious patriarchy; in a world that preaches realizing one’s identity, some of us choose to chain ourselves to these ideals.

Our hijab is not an evil we need saving from, nor can it be reduced to the definition that oppressive political regimes impose upon it. Here, in Canada, Muslim women

might have the freedom to choose whether to wear hijab, but we walk on our tiptoes, afraid that this visible symbol of our beliefs will reduce us to an idea of the hijab that is synonymous with oppression, to the construction of hijab that permits self-congratulatory rhetoric from the Western world as it attempts to free us from this illusion of repression.

It’s not our hijab that veils our identity and freedom, but the shadows we have to hide it under.

Many things could go wrong before, during, and after weddings, much like what happened in the 1991 film, Father of the Bride. Wearing a wedding ring symbolizes the bond of matrimony, whether in a happy marriage or not. Not only does the purity of love matter, but the purity of the precious gemstones, diamonds, and gold that goes into crafting the perfect ring is also under high scrutiny. Seldom do people pay attention to the sustainability, sourcing, and exploitation hidden under the blinding sparkles of jewels. The more I dig into the bejeweled industry of small-scale artisan gold mining, the more heartbroken I become. I have thus decided to share my findings in the hope of strengthening our collective conscience as consumers, whether you plan on getting married or not.

Historical records of using mercury to extract precious metals, a process known as mercury amalgamation, can be dated as far back as the mediaeval era. This extraction technique was first industrialized in the sixteenth century in what was then New Spain, or present-day Mexico. Mercury supply in South America was reliant on mines such as ones found in Huancavelica, Peru. However, a considerable amount of mercury was lost in the extraction process of silver and gold. This mercury waste was exacerbated by a chemical reaction between mercury and other ionic salts found in

mined ores.

The scale of mercury emission only grew with the passage of time. Many of these gold mines are either illegal or operate clandestinely in conservation areas, famously along rivers in the Western Amazon. In the past decade alone, the Peruvian Amazon has seen more than forty percent growth of small-scale gold mining, discounting growth outside of protected areas.

Small-scale gold mining is an industry that is present in more than seventy countries, which are responsible for one fifth of the world’s gold production. Artisanal gold mining is implicated in the livelihoods of at least ten million people, including people living in economically deprived nations. These unregulated small-scale gold mines are the greatest contributors to anthropogenic mercury pollution in low-income countries.

I was even more startled to find that more than three million women and children are estimated to be among the workers who handle mercury in the gold extraction process. The gold mining mercury waste mostly ends up in nearby waters, such as rivers, lakes, and streams. Such unprocessed runoff poses health threats for communities dependent on those water sources. There are figures showing that up to 95 per cent of mercury used in small gold mines could be released into the environment. Hence, the workers in smallscale gold mines are not the only ones exposed to mercury. Mercury exposure is hazardous for pregnant women; Japanese scientists found that the

organically active form of mercury can cross the placenta and affect fetal development. The neural development of offspring can be endangered if pregnant women accidentally consume mercury-contaminated fish. Scientific literature has documented intellectual disability and impaired cognitive functions in the babies of mothers exposed to methylated mercury.

Additional research revealed that the latency before the onset of mercury-related symptoms takes longer than expected. The dormant period of mercury exposure’s adverse effects lengthens in an exposure-dependent manner. These life-long conditions from prenatal mercury exposure are estimated to cost around $11 billion in economic productivity over the lifetime of affected children.

As human existence depends on the health of the Earth, I read more about the ecological impact of mercury pollution in various ecosystems. A 2022 study published in Nature Communications documented methylated mercury in soil neighbouring artisanal small-scale gold mines for the first time. Moreover, mercury can also enter the ecosystem in vapour form from the regular burning of the chemical at gold mines. The Peruvian Amazon mining town samples are exposed to mercury vapours in concentrations comparable to highly industrialized countries such as the US, China, and South Korea.

Destruction and alteration of the natural landscape is inevitable in establishing ar-

tisan small gold mines, often right in the heart of some of the global biodiversity hubs. An ecological study on the impact of mercury pollution to the Amazonian ecosystem concluded that mercury emissions are deposited and transmitted through trophic levels of food chains. It is important to note that inorganic mercury must undergo methylation by microorganisms in order to be made available for entry into the natural food web. As characteristic canopy leaves in the Amazon rainforests behold mercury concentration well above the mean values in all kinds of forests around the globe, forests near gold mines are potential “hotspots for mercury bioaccumulation into terrestrial food webs.”

As a human being, I am alarmed by these emerging reports, and there is good reason for you to be too. Environmental protection is a life-saving effort for our own livelihood as humankind. Being the top predator on Earth means we are susceptible to mercury exposure through meat consumption. We must act now before the portrayal of Earth as a desolate planet in Wall-E becomes a reality. International corporations continue sourcing gold from informal small-scale gold mines because of financial incentives. We have the power, as consumers, to hold these companies accountable by supporting sustainable jewellery brands. Besides inspecting the purity of gold wedding bands, we should pay close attention to the purity of the air we breathe and the food we eat. Eco-friendly living is not enough; ‘tis the time to be eco conscientious.

Content warning: This article contains discussion of violent crime and violence against women.

Most of us would happily agree that we condemn murder. We recoil from reports of crime in our own communities and shrink back from televised acts of violence in the world at large — reasonable, moral reactions to such vile actions.

Nonetheless, stories about these events propagate, and true crime still occupies a pervasive place in our minds. Try as we might, we can’t

seem to drag our eyes away from the screen or yank our headphones out when certain names and stories rise to the surface, such as JonBenét Ramsey, Ted Bundy, D.B. Cooper, Jack the Ripper, O.J. Simpson, and The Zodiac Killer, among many others.

Why, despite the horror and disgust, do these tales hold so much power over us? What makes us keep coming back to true crime, and what function does it serve in our daily lives?

The term “true crime” is usually used to describe any media about… well, a crime

that really happened. Prudent readers will observe that the term “true” here is almost entirely subjective. Naturally, everything from the order of events to the identity of the culprit may be framed differently depending on the storyteller. Depending on the retelling, a true crime podcast, TV show, or novel might be accurate down to the timeline, location, and grisly details. It also might act as a vehicle for an author’s — or an audience’s — ideas about what might have happened, especially when a case is unsolved.

This brings us to one of the most evident reasons for true crime’s enduring popularity: it’s hard to resist a good story. The longevity of the genre seems testament to this fact — in Britain, pamphlets recounting tales of violent crimes circulated as early as the 16th century. Compared to the binary guilty-or-not verdicts of the justice system, retelling crimes like stories provided more nuanced insight into a perpetrator’s cause and culpability, and a more entertaining one at that.

Today, most scholars rec -

ognize the 1966 non-fiction novel In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences as the inaugural work in the modern true crime genre. Truman Capote’s work vividly retraced the violent murder of the Clutter parents and two of their four children, which rocked the family’s tiny hometown in western Kansas. Despite its shocking subject matter, the book’s success signaled a genre-wide shift in convention. True crime now favoured works like Capote’s that emphasized the identity and motivations of the perpetrators, as well as the authors’ personal relationships — real or purely literary — to them.

For a more recent example, it’s hard to beat Sarah Koenig’s 2014 podcast Serial, a detailed retelling of the 1999 murder of Baltimore high school student Hae Min Lee. Infamously, Serial combines both evidence presented in the case against the accused killer — Lee’s classmate and ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed — with Koenig’s extensive interviews with Syed while the latter was in prison. Not only were listeners able to follow Koenig as she read through court documents and interviewed family, they could also hear Syed’s voice for themselves, scrutinize his tone of voice in conversation, and pore over every turn of his phrase.

Beyond the success of narrative-style true crime hits like In Cold Blood

and Serial, scientific evidence also supports the idea that true crime enthusiasts are frequently invested in following the narrative aspects of a crime. One 2018 study surveyed participants recruited from true crime podcast social media groups on their reasons for listening. Among more than 300 participants, the three most common reasons were entertainment, described on the questionnaire as “I love a good mystery”; convenience, as podcasts are an “easy way to hear more true crime stories”; and boredom, as “I have nothing better to do.”

This finding was supported by research conducted at the School of Justice at Queensland University of Technology in Australia in 2020. The researchers asked 124 university students to rate how much they agreed or disagreed with certain motivations for listening to true crime podcasts. Again, the most commonly endorsed reasons were tied to entertainment, rather than safety or education. Partici -

pants were most likely to agree with statements like “listening to true crime podcasts is compelling,” or that they enjoyed “speculating on who was involved” and “putting together the pieces of evidence.”

This suggests that many people enjoy true crime for the same reason they enjoy a fictional murder mystery or psychological thriller. They’re interested in following a story as it unfolds, and they find it gratifying to try connecting the evidence and identifying a culprit.

Interestingly, patterns emerging from both of these studies hint at another reason that true crime media tends to stick with us. In both cases, researchers sought out a relatively demographically balanced sample of true crime consumers to serve as participants. But respondents were overwhelmingly women — even in the 2018 study, in which participants were largely recruited from Reddit, a platform known for its

predominantly male user base.

In fact, women actually make up the majority of true crime consumers. Most Amazon reviews of true crime books are authored by women, even when controlling for the fact that book review writers are overall more likely to be women than men. When presented with books on other comparably violent subjects like war or gang violence, women still favour novels about true crime.

Amanda Vicary and R. Chris Fraley, authors of a seminal paper on why women are drawn to true crime, suggest that this gender-based disparity exists because women experience a greater fear of crime, a notion supported by previous research. In this way, true crime media doesn’t just serve as entertainment, but a source of potential advice for survival.

In one study featuring over 13,000 participants, Vicary and Fraley gave participants a choice between two books depicting a woman who escaped from a killer. Women preferred the book that included a “clever trick” facilitating the character’s escape. This preference was also found in men, suggesting that the inclusion of the

trick may simply have caused the book to sound more interesting to potential readers. However, it was accompanied by a follow up, which found that women were also more likely than men to select books depicting female victims. In other words, women favoured stories with survival tips and victims that resembled them more, increasing the value of potential safety advice.

Altogether, Vicary and Fraley’s research suggests that women in particular may be interested in true crime for reasons other than entertainment alone. Boosting vigilance may be an extra incentive for women, who are more likely to be the victims in memorable, high-profile cases.

In fact, a notable amount of prolific true crime media is presented by women — in addition to Serial with Sarah Koenig, there’s also the podcast My Favorite Murder , hosted by comedians Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark. Apart from circulating information related to self defence, the communities that spring up around this media can provide a unique space for women to discuss both their own fears about victimization as well as other mental health concerns. In this way, engaging with real-life tragedies can act as a form of emotional catharsis and ease underlying anxieties.

Regardless of gender, consuming true crime media can induce an electrifying rush of

excitement. This idea is supplemented by previous work exploring why people enjoy horror media like scary movies. For one, exposing ourselves to frightening experiences is exhilarating — picture the rush of adrenaline you get after being jumpscared. For most of us, it’s also new and unusual, so it may make us feel more worldly or accomplished.

Relatedly, people who strongly enjoy horror are often high in the trait of “sensation seeking,” meaning that they feel more compelled to seek out new, thrilling experiences. Recent work has shown that this trait of sensation seeking is also positively associated with morbid curiosity, or the desire to know more about

traditionally unpleasant subjects like death and terror. Exposure to morbid events, such as autopsies or executions, is likely to induce a physiological response in the body and activate parts of the nervous system associated with excitement and responses to stress.

So people who already enjoy genres like horror are also likely to be curious about the morbid topics often covered in true crime media, and engaging with true crime stories can create feelings of excitement and novelty that get them hooked on the subject.

However, alone, these justifications ignore a glaringly scary fact: true crime is true. It really happened.

“Do you even lift, bro?” : Lifting the weight of diet culture

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of eating disorders and body dysmorphia.

Growing up in the early 2000s, I was constantly exposed to diet culture. It was ingrained through the advice of peers when they told me to “drink water when you’re hungry” and further emphasized as I passed racks of grocery store magazines that quizzed me, “How much do celebrities really weigh?”

Eventually, I, along with most of my peers, matured and learned to identify the toxicity of these diet culture fads. We became exposed to a greater number of representations of eating disorders in these very grocery store magazines.

On a larger scale, I was recently reminded of the effects of eating disorders while reading iCarly star Jennette McCurdy’s memoir I’m Glad My Mom Died, which delves into her experience dealing with multiple eating disorders throughout her life. Within the first week of its release, the memoir sold over 200,000 copies and, in the same month, it became the number one New York Times Best Seller for non-fiction.

Following the release of McCurdy’s book and after experiencing similar negative emotions toward their own bodies, some influencers have taken to social media platforms to exhibit their own insecurities. Their stories have come to light through a variety of different trends, including ‘realistic fashion hauls’ and posed photos that users

posted in comparison to the photos they kept in their camera roll. The goals of these trends, which were often created by women, were to allow other women to feel comfortable in their bodies, no matter their size.

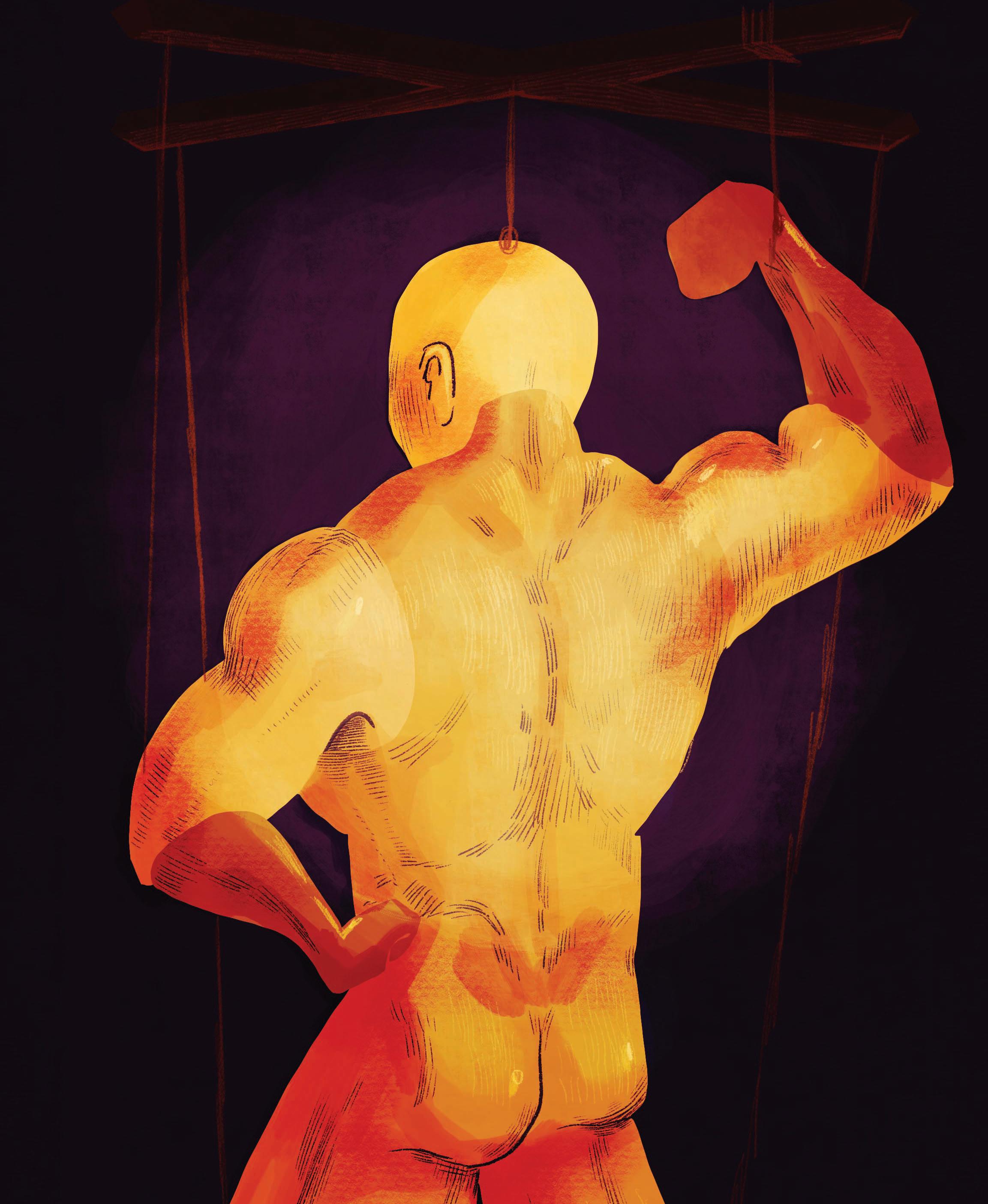

Another movement is growing simultaneously, which promotes fitness to men, increasing the competitiveness involved in exercise. This culture, nicknamed ‘gym bro culture,’ encourages these men to exercise regularly with peers to increase their physical gain and lose weight through traditional dieting and bulking — habits that research has found to be harmful.

Of course, it’s incredible that body positivity trends exist for women — 97 per cent of us have at least one negative thought about our bodies each day. However, another side of this picture goes unnoticed: more than 90 per cent of men struggle with body dissatisfaction. So, amid what the internet is branding the “female body positivity movement,” I want to know — where is this representation for men?

Is it cutting or bulking season? To gain muscle and strength, athletes and gym goers often undergo phases called bulking and cutting. Cutting involves eating fewer calories than you burn in order to lose fat. In comparison, bulking entails eating more calories than you need in order to put on weight, then building muscle through resistance training.

Kyle Ganson is an assistant professor at U of T’s Inwentash Faculty of Social Work.

In a 2022 study that Ganson was the first author of, named,

“

‘Bulking and cutting’ among a national sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults,” nearly half of the male participants reported attempting a “bulk and cut” cycle in the past year. The study determined that participating in these bulk-andcut cycles was associated with a stronger drive for muscularity.

In a quote given to Medical News Today, Ganson wrote that because of the popularity of bulking and cutting, as well as its avocation through online and fitness communities, “we need to be thinking of it as potentially overlapping with serious mental and behavioural health conditions that can have significant adverse effects.”

Ganson continued by highlighting that healthcare professionals should be “aware of this unique behaviour and not just screening for ‘typical’ eating disorder behaviours, such food restriction and binge-eating, or ‘typical’ body-focused attitudes and behaviours, such as [a] drive for thinness.”

For many, the bulk-and-cut cycle can begin as a manner of observing more prominent results in fitness, a lifestyle intended to maintain health. So how can this seemingly well-intended action transform into forming toxic habits? The answer seems to lie in the practice’s intense nature.

A dramatic transformation

One of the main issues with cutting is that it glosses over exhibited symptoms of eating disorders, mainly anorexia, in the name of health. Maximuscle is a health nutrition company in the United Kingdom whose website features an article

called, “Bodybuilders [sic] Top 10 Tips to Help You Cut.” Some of these tips include using cardio exercises to increase your calorie deficit — the shortage in the number of calories consumed relative to the number of calories needed to maintain body weight — and decreasing the amount of cooking oil you use when preparing meals. Other tips included upping your water intake and “Be[ing] Ready To Deal With Hunger.” Do you notice the recurring messaging here?

The sudden weight gain of bulking, on the other hand, presents significant body image issues for the bulker — a problem that the general fatphobic culture in Western society further encourages. In the popular TikTok series “Wheymen,” user @eddygee cites a verse that they call “Bromans 3:24.” The verse goes: “If they do not love you at your bulk, they do not deserve you when you’re shredded. For a true gym bae looks at work ethic and judges only by where a person is headed.” Despite this user’s well-intended message — that people in your life should love you despite what your body looks like — they push the idea that men are not typically attractive during their bulking phase.

To prevent the self-consciousness that stems from the fatphobic pressures ingrained in our society, many individuals choose for their ‘bulking season’ to happen in the winter, when they can hide their bodies under baggy clothes. This then enables the ‘cutting season’ to happen over the summer, when we typically wear less clothing to show off our bodies. The problem with associating bulking and cutting

with specific months is that it makes it easier to slip into these habits year after year.

To achieve bulking goals, some individuals eat massive amounts of food in a short period of time in order to hit their macronutrients’ — macros — goal numbers each day. When tracking macros, you are essentially counting how many grams of proteins, carbohydrates and fat you’re eating in your daily meals. Such activities have allowed individuals to develop binge-eating disorders and potentially even bulimia. There are multiple articles and Reddit posts sharing tips on how to not throw up throughout the bulking phase. Tracking macros also has the potential to become addicting; trying to stop tracking may leave an individual feeling like they’ve lost control and induce feelings of anxiety.

Maintaining “healthy”

On the toxic end of bulking-and-cutting patterns lies muscle dysmorphia (MD), colloquially known as ‘bigorexia.’ It is a health condition that makes individuals dissatisfied with the muscle they currently have and pressures them to constantly think about building more. It is a type of body dysmorphic disorder.

Some of the more specific symptoms of MD include spending hours at the gym, pushing your body beyond its physical limits day after day, and following specific diets to cut body fat and add muscle, with no end in sight.

The tricky aspect of MD is that a lot of its symptoms also correlate with an active lifestyle, which blurs the line between health and a health concern. Often, those with MD also develop orthorexia, an obsession with eating healthy foods. People with orthorexia and those with MD follow strictly disciplined diets and essentially become so preoccupied

with consuming the most nutritious foods that it interrupts other aspects of their lives.

With the addictiveness involved with going to the gym and tracking macros previously mentioned, it’s really not a surprise that addiction in gym bro culture goes deeper. Many weightlifters and bodybuilders have been found to have abused anabolic steroids, which non-athlete weightlifters primarily use to improve appearance. Steroid use is primarily associated with MD, and some steroid users have

started steroids because they believe that they are at a lull in their physical transformation journey and that weight training alone is not enough to reach the muscle mass they want. The use of steroids has been shown to trigger anxiety, depression, paranoia, and psychosis in individuals who are potentially susceptible to mental health problems.