Writer: Sky Kapoor Visuals: Jadine Ngan, Caroline Bellamy, Makena Mwenda

I make a pros and cons list for nearly every major life decision. Cons highlight the negatives; they tell you about the flaws of everyone involved, the sort of things you should look out for. Things you can’t look past. Things you shouldn’t like. In any case, I hate the way you take your coffee. Who the hell uses sweetener?

Every time you look at me, I find myself trying to suppress my natural impulse to spill open like a sunset, sinking deeper into my own mind.

I hate your little idiosyncrasies — the way you draw the vowels out a little too long in your favourite catchphrases, the way your eyes crinkle when you laugh, the crookedness in one of your canines.

My soul can’t cope with this. It shouldn’t be expected to.

I hate the way you always take life a little too seriously. For crying out loud, loosen up for once. You’re too traditional for someone like me — it took me a while to wrap my head around the fact that you’ll always hold doors open and never think twice about offering other people help.

When the pain is both physical and existential, you make it a little more manageable.

The only reason I care for all those cold morning commutes is because you’re at the end of them.

This could be so much easier than we’re making it.

Come on, do you really think I’ve been waking up at four in the morning naturally? I’ve been setting alarms for the foreseeable future because I know you get restless in the middle of the night and can’t sleep sometimes.

I want to be there for you. There’s a lot on your mind, and there’s a lot on mine. Somehow, these clandestine conversa tions at such an early hour feel special.

I doubt you’re talking to anyone else when dawn breaks, and that brings me comfort.

I hate the way your texts make me light up like Christ mas morning.

I hate that you’ve already told your mom about me.

I hate that no matter how

much I delude myself, it’s inev itably going to creep up.

We knew this was coming. It’s really easy to pretend you’re not waiting on someone when they’re not here.

I hate that I’m an abandoned house that you’re trying to con vince yourself not to enter. A bit too much chaos for your taste — something you’d usually wash out with soap.

I’m trapped within this situ ation, nothing but a plaything.

“How are you feeling?” you ask me.

Scared. Hurt. Terrified. Stressed. Like I miss you. Like I got hit by a semi. Like I could rival Philippe Petit. Like a freight train. Like a corpse.

“I’m okay. How are you hold ing up?” I hate that it takes every fibre of my being not to blurt out something stupid. I’m worried that in spilling myself open, I’ll tear us apart.

“Same old dilemma.” And so we get into it.

I listen to your quandaries whenever they arise. In all of this, I see the way you’re being treated, and can’t help but think — no, I know — that I could treat you better. And I would, were I given the chance.

Just lean into it. Let me show you what things are supposed to be like.

“Things are all going to work themselves out.”

I’m saying it for you as much as I’m saying it for myself.

This feeling chips away at my very being until I’m bone-white and flaking — a snow of sorrow.

I keep thinking about how badly I want to hold you when we see each other again, how dangerously it’s going to feel like home, and how, unfortu nately, I’m never going to want to leave.

I keep thinking about how devastatingly badly I want to be in your presence. How, tragical ly, I’d be more than okay with it. How, terrifyingly, I’ve never let anyone this close before. And how, horrifyingly,

I have a bad habit of trying to save people.

I hope that maybe this time things will go according to plan. Maybe, eventually, we’ll watch the darkness creep over the sky together, as if the world has drawn to a sleepy close, ready to awaken for the next day.

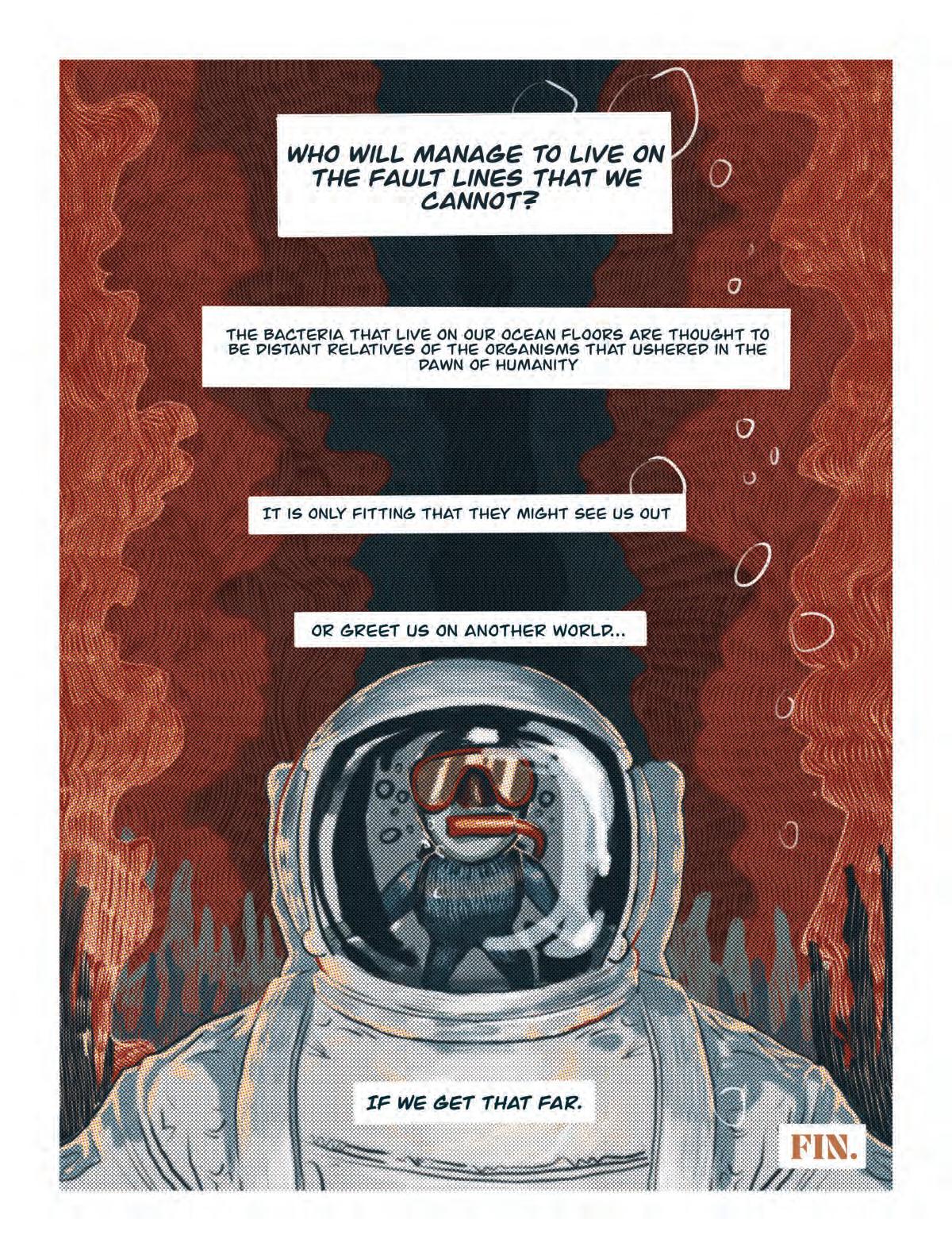

This simple and somewhat ridiculous phrase hung over my head for much of my child hood. Although I didn’t truly believe that stepping on a crack would injure my mom, I still hopped from one concrete square to another, altering my strides to fit the irregular patterns of each walkway.

I’m not alone in this strange behaviour. In an informal poll of my friends, 88 out of 96 people I surveyed recognized the rhyme. In fact, people have gone out of their way to avoid cracks for more than a hundred years — inadvertently revealing qualities that make us human.

It remains unclear when exactly the sidewalk crack superstition sprang up. The earliest source that I could find connecting sidewalk stepping to broken backs was an 1897 journal titled The Pedagogical Seminary Since the superstition needed to be relatively well estab lished for it to appear in print, I’m guessing that the rhyme entered the scene sometime before 1897.

Some sources allege that the current rhyme is a modified, less racist version of, “Step on a crack, and your mother will turn Black.” This verse would have reflected white peoples’ fear of racial “contam ination” — but I found no mentions of anyone hearing or actively using this version. Although racism underlies other childrens’ rhymes,

including “eenie meenie miney moe,” this may not be one of those rhymes.

However, other — thank fully, less racist — variations abounded. In 1923, a survey of superstitions collected from college-aged American women mentioned an iteration where “father” was swapped for “mother.” Other versions claim that stepping on a crack can cause everything from failure in school to the devil’s murder.

The wide variety of these penalties reflects a deep uneasiness about cracks. In 1895, pro fessors from Clark University conduct ed a survey asking students whether

they avoided cracks in the floors or sidewalks. More than a hundred students reported doing so either automatically or due to undefined apprehen sion. One participant noted, “If I step on a crack, I feel as if something will surely happen, either to me or [someone in my] family.” Another reported that “something in [sidewalk cracks] suggests danger.”

The most striking ex pression of this vague fear appeared in a 1897 short book called A Boy I Knew and Four Dogs. The au thor, Laurence Hutton, describes a group of children who made a point of avoiding

cracks in the ground, even going so far as to entirely avoid streets paved with bricks. “What would have happened to them if they did step on a crack they did not exactly know,” Hutton wrote. “But, for all that, they never stepped on cracks.” The ambiguity of the consequences here suggests that, at this point in time, the specific mother-related super stition hadn’t fully taken hold. I’d wager that superstitions spring up around cracks be cause they symbolize instability and openings. When one envisions the aftermath of some seismic event, crumbling struc tures or sudden fissures come to mind; the presence of cracks means that everything is about to come crashing down.

Cracks can also indicate gateways: for instance, shows such as Gravity Falls and Doctor Who portray spacetime rifts — locations where different spaces and times become fused — as cracks. Although openings to new worlds can be exciting, they are also unknown entities, which can stir up fear.

The source of superstitions Although I found little scholarship on the sidewalk crack super stition’s exact origins, many social scientists have studied the human elements that give rise to superstitions in general. According to a paper published in the International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, three human tenden cies are key to supersti tions taking root in our

“Step on a crack, you’ll break your mother’s back.”

minds: habit, causal thinking, and cultural transmission.

Habits are cogni tive or behavioural routines that be come disconnect ed from their original goals. A habit forms when we learn, through repetition, to associate certain acts with neuronal rewards such as the release of dopamine and other neu rotransmitters. These circuits prompt us to continue perform ing these behaviours, even if the original rationale no longer applies.

This research helps explain why I still avoid sidewalk cracks; although I don’t ac tively believe in the supersti tion associated with them, my younger self’s rigid adher ence to the rule helped form neural pathways that reward my continued obedience to it.

Causal perception, or the tendency to interpret the world as a series of causes and effects, is also essential to understanding the rise of superstitions. If something happens following an inci dent, we tend to assume that the two events are connected. Although this type of pattern recognition can help us better predict and manage future situations, it can also lead us to connect disparate and un related happenings, thereby creating superstitions.

While habit formation and causal thinking lead individuals to believe in superstitions, cultural transmission allows them to spread. Many people I talked with had first heard about the sidewalk crack superstition in the media, including cartoons and books.

Others heard about it from friends. “It was one of those phrases that we would throw around not really knowing why we said it or how it came to be,” my friend María Díaz wrote in a message to me.

As they are transmitted, pieces of cultural data undergo a sort of evolution, morphing to fit the needs and boundaries of societies. Many social psychol ogists argue that superstitions succeed because they fulfill a human need for explanation, imposing control in a funda mentally unstable world.

This theory is supported by observa tional studies that link riskier businesses, like deep-sea fishing, with increased rates of super stitious rituals. In situations where luck doesn’t play such a large role, there is less need to artificially impose one’s will on the world through super stitions. The sidewalk crack superstition seems to further support this theory — cracks themselves are a symbol of instability, and we deal with that instability by assigning penalties to them.

Superstitions are also more likely to succeed when they offer a large reward but

don’t cost much to follow. The sidewalk cracks superstition is a good example of this: avoiding cracks takes little time or money and is far less burdensome than having to care for a family member with a spinal injury. However, I don’t be lieve that the sidewalk crack rhyme is successful as a superstition, be cause it doesn’t inspire belief. Most supersti tions are untestable and vague enough that a believer can read traces of the superstition into any outcome — think horoscopes or fortune telling. But “step on a crack, break your mother’s back” is an incredibly specific claim that’s easily disproved; as soon as a child steps on a crack and observes that their mom isn’t injured, the belief falls away.

In my opinion, the verse is more of a game than a source of fear. This purpose has been clear from the phrase’s early days. The earliest source that I could find connecting any ill effect to stepping on cracks was an 1891 article in The American Journal of Psychol ogy, which described children playing a game where anyone who stepped on a crack was “poisoned.” I’m also partial to this description of the rhyme because it aligns with my expe rience. For me, avoiding cracks is a gateway to my childhood: a way to rekindle my imagination. It’s a game I can play anytime and almost anywhere, and it’s a reminder that our attempts to impose reason on the uni verse often end up sounding ridiculous.

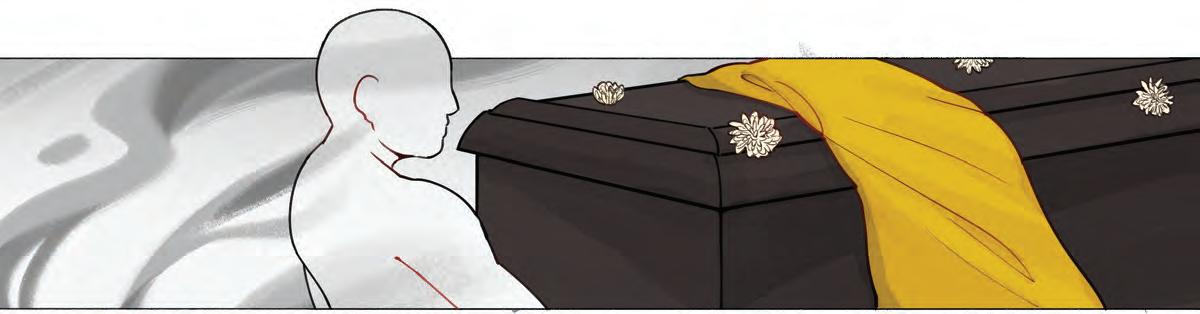

In Chinese culture, it is customary for the oldest living male descendants of the deceased to lead the funeral rites, especially when a man in the family has died.

This serves multiple functions, my parents have explained; firstly, it signifies that the family name will be carried on by viable heirs. It also upholds the image of the next generation. When a son or grandson leads the funeral, they are fulfilling a duty in deference to their departed patriarch. From an onlooker’s eyes, they represent hope for the family’s future.

My paternal grandfather passed away this past December. He had late stage liver cancer that went undiscovered until September, when he was rushed into the care of one of my father’s old friends from medical school.

I called my father a lot about it over the fall semester. The news had struck at the most inopportune moment: after about 20 years of working low-paying postdoctoral research jobs, he was in the middle of switching to a prominent position at a prestigious biotechnology company. It was a dream come true. His salary would be tripling practically overnight, and he felt that all the long nights he had spent fine-tuning his skills in academia were finally paying off.

Because of COVID-19 restrictions, though, it would be impossible for him to return to his family home for the funeral and still make it back to the US in time to start his new job. The 2022 Winter Olympics meant that international travel was highly restricted, and he would be subject to weeks’ worth of quarantine if he attempted to make the journey.

In the end, he didn’t take the flight. I saw how much it tore him apart; in 25 years of living in the States, he had never once returned home, too occupied with his work and then with the ordeal of raising me and my brother. When the photos of the funeral came in, he didn’t show them to us.

My mother was the one who delivered the news of my grandfather’s death to me. She was never close to him, but she was worried about how my father was coping, and asked me to keep an eye on him over the following weeks. He was always willing to be more open around us kids, she said — she’d tried to coax his feelings out of him for weeks already to no avail.

My mother and I talked a lot more about it when I flew home to Boston after the end of the fall semester. While my younger brother was away at school, I slept in until the early afternoon, catching up on the sleep I’d missed during finals season.

Every time I emerged from my room, bleary-eyed but finally well-rested, my mom would have the table set and a variety of homemade dishes laid out in wait. Over lunch, she would tell me about what was going on in the family — my grandfather’s funeral, her recent reconnection with her brother, and pieces of news from our other extended family members who I couldn’t hold a conversation with because of my poor Mandarin.

Inevitably, though, the conversation would turn to the subject of my father and their marriage.

To put it lightly, their relationship had always been tumultuous, even from the start. My parents had dated for eight long years prior to putting a ring on it; long enough that my maternal grandparents considered their daughter a failure for getting married so late in life. In reality, she was around 30 at the time they were married — a perfectly reasonable age by most standards.

Still, in accordance with the traditional view that a woman passes from her family of birth to her husband’s family when she gets married, they turned their backs on her after the wedding.

Maybe these stories speak more to the kind of people my maternal grandparents are than the role of women in China. Within the history of my mother’s life, though, those two things seemed inseparable, even from birth.

When she was still a little girl living at home, she told me, her birthday was celebrated during the Lunar New Year — when all children are said to turn another year older — instead of the actual day she was born. She didn’t say as much to me, but I suspected this was never the case with her brother.

After my parents immigrated to North America, our family briefly lived in Tennessee, where my younger brother was born. During the year we spent in Nashville, my mother would while away the hours when my father was at work by flipping through the Yellow Pages.

Over tangyuan and jasmine tea, she recounted finding dozens upon dozens of adoption agencies dedicated solely to the export of baby girls. At the time she was seeing this, the local news was talking about girls left behind by their families in China because of their sex assigned at birth. Walking my brother in his stroller down the street, she would be stopped by white women in the street, strangers begging her for advice on how to raise a Chinese baby.

I didn’t know what to say in response to most of these stories. That was okay, it seemed. My mother seemed satisfied enough that I was there to sit and listen while we ate. Empty bowls and dirty chopsticks would pile up on the table until we were finished with lunch, and then my mother would ease me back down into my chair when I tried to stand to help with dishes.

I was at home, she told me, not work or school. This was the place for me to relax and be cared for. I protested, trying to convince her to let me help wipe down the table or pack away leftovers, but she would silence me with another cup of tea or a mouthful of my favourite childhood snacks, which she’d squirrelled away weeks in advance for my arrival.

Jokingly, I told her that all the attention was making me feel spoiled. My mother only patted me on the shoulder and smiled in response.

“Of course I’ll spoil you,” she said. “You’re my only daughter.”

Three years ago, I travelled across the world — 11,179 kilometres, to be exact — to a continent I had never been to before. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote, I was fleeing choicelessness. I needed to find a city that could love me back. A place to call home. A place that could feel like home.

Some days, I think I have made that home in Toronto. Other days, I am not so sure.

my loved ones in Toronto know Pakistan as “back home” we cross a busy road to get to Staples and I say, “back home, I would have been harassed walking across the road.”

temperatures go below -10 degrees and I say, “back home, it doesn’t get colder than 5 degrees.”

Toronto is so much colder, yet unbelievably warmer

you cannot forget a place you called home for 18 years it holds you like a curse some days

back home, love is a precious jewel you hide, lest you be mocked you cover every body part in loose layers, lest you be called behaya* you learn to be conscious of the curves on your body every passing moment

you don’t talk about religion, lest you be charged for blasphemy you don’t ask for professional help, lest you be called ungrateful you don’t criticize patriarchy, lest you be told you’re wrong, or called ungrateful, or charged for blasphemy

back home, you make yourself smaller lest you be called a woman in Toronto, I hug those I love outside the 7-eleven at Bloor and Spadina I wear tank tops, skirts, my little joys, and maroon lipstick I tell my friends sunsets are my religion and they know it’s true I pick up my antidepressants from the drug store in this home, I exist, I get to experience joy I almost even see the city love me back

until I take out my Pakistani passport to prove my identity in this mundane act, I become a stranger in this home I built for myself

I can adorn my identity in sunsets, Mary Oliver, and good coffee but the truth is a curse I have failed to get rid of it shows on my skin, in my accent, in my back home and the back home emerges to haunt me again it will never love me back, but at least I am not a legal alien back home

it takes 16 hours to go back home, but sometimes all it takes is being the only one asked to open my bag in a queue of white people, all except one; all except me

*behaya: An Urdu word meaning ‘indecent.’ It is a common word thrown around to refer to a woman who goes against the norms, who is seen as defying religion and culture; someone to steer clear of.

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide. Why do you feel lonely? It might be because, at the moment, you can’t see your friends in person. But we also feel lonely even in times when we can meet up with friends. What even is loneliness, and why does it feel like it’s getting worse?

Loneliness is something we’ve all experienced at some point or another. It silently takes over our minds, and makes us feel more tired and depressed, without us realizing that it is the cause of our unhappiness.

All of us, even the least so cial, will feel lonely at some point, simply because humans are social creatures. We have socialization built into us, and losing that socialization after a certain point becomes as lethal as any physical illness. It can lead to increased risks of heart disease, obesity, and suicide.

Loneliness is described as a disconnect between our per ceived and desired levels of

social connectedness. It’s what we feel when we don’t have enough friends, or we aren’t able to get the quality time we truly want with them.

An important distinction to make here is that loneliness is different from social isolation. While the definition of lone liness can vary from person to person, social isolation is objective and refers to someone who is physically distanced from society.

Professor Roger McIntyre, a researcher at UHN, pointed out that the subjective experi ence of loneliness is heightened in the case of celebrities. We hear celebrities and famous or popular individuals talk all the time about feeling lonely, and we wonder how they can be lonely if they’re loved by so many people.

Take Taylor Swift, for exam ple, who is often referred to as “the music industry” by her literal hundreds of millions of fans. Yet, in a documentary about her, Miss Americana, she

revealed that she has struggled with loneliness throughout her life — and it especially hits her when she’s in the spotlight.

“Shouldn’t I have someone that I could call right now?”

That is what she said was going through her mind after winning Album of the Year in 2016 — a moment that should have been filled with joy and celebration. And while we’re sure she did celebrate, that quote being her first response goes to show how lonely she felt in the spotlight.

We look at all her fans — all the love and adoration she gets despite the hate that the spotlight brings — and we still can’t comprehend how she must feel lonely. But the issue is that those connections aren’t the proper interpersonal relationships we need. They’re superficial, and not enough to prevent those feelings of lone liness.

Meanwhile, some individuals can be content with just three or four connections, and can feel

completely satisfied if those connections are deep enough and maintained properly.

Over the past two decades, loneliness has become more widespread and better under stood. Recently, the Universi ty of Chicago’s General Social Survey, which monitors shifts in social changes and attitudes in the United States, found that the number of people who say they have no close friends had roughly tripled since 1985. This might seem strange considering the immensely interconnected world we live in now — or it might just feel familiar, per haps acting as a confirmation of the feeling that social media exacerbates loneliness.

While the internet does con nect us with more people, these relationships are more likely to be superficial, going no deeper than the posts you see or tweets you like. They lack the deep connections that are necessary and important in maintaining

mental and cognitive health — the connections you need to not feel lonely.

The digitization of social spac es, combined with the increas ing trend in North American cit ies of people living alone, has the risk of massively increasing loneliness in the population. Digitization isn’t all bad — I’ve made friends online and had meaningful interpersonal con nections with them — but it can be harmful when all you have are surface-level relationships.

But something else is in creasing this loneliness too. It’s a nefarious part of this whole problem: loneliness itself is contagious.

Studies have shown that non lonely individuals who hang out with lonely individuals are more likely to end up lonely them selves. This happens mainly because when one person is lonely, their social habits tend to get rewired along with stress responses, making them act colder or less emotionally avail able to others they are friends with. This in turn leads to those friends feeling a disconnect between their desired and per ceived social connectedness, creating spreading feelings

of loneliness if this continues over time.

The contagious nature of loneliness is something that seems rather frightening and has the potential to exponen tially increase the risk of loneli ness as a serious illness in the population.

Psychological effects like feel ings of depression and anxiety are often described as some of the most major impacts of loneliness. And the reasons for this are entirely correlated with physiological and neurological changes — changes that are drastic enough to show up in simple MRI tests.

In an interview with The Var sity, U of T psychology profes sor Paul Whissell explained that loneliness leads to increased stress-like symptoms, which create the creation of more cortisol and noradrenaline than a healthy brain is used to. Cor tisol and noradrenaline — a precursor to adrenaline — are hormones and neurotransmit ters, chemicals that are used to signal messages and carry out processes all across the nervous system.

By increasing these neu rotransmitters, the body and brain know that something — a stressor — is messing up the system. If a stressor exists for a short period, it leads to acute stress, which is the type you would experience writing an essay the night it’s due or writing an exam you haven’t prepared for.

Low to medium levels of this stress can lead to improved memory, cognitive ability, and more — which is why you might hear some people say that they work better under stress. However, increasing these levels even just a little too high will have the opposite impact, leading to cognitive impairment and slower mem ory. Think about how you feel when you write one paper last minute, compared to when you have papers due for three of your classes and a final exam tomorrow at 8:00 am.

But the good thing about acute stress is that the impacts are reversible. Exercising a bit, spending time with friends and fami ly, or even

looking at pictures of cute animals all have been shown to reverse these impacts and return our neurotransmitter levels to normal.

But the biggest issue comes in when the stressor doesn’t go away, such as when you’re un der stress for weeks or months at a time — be it financial stress, academical stress, emotional stress, or anything else. And loneliness can cause effects that are just as bad, if not worse. When someone is lonely for long periods, stress-related hormone levels stay at their increased levels for far longer, resulting in patterns of chronic stress.

With excessive or long-term activation of these stress re sponses, we start noticing all kinds of brain changes, par ticularly in behavioural and emotional processing.

Loneliness has a marked impact on the size of the hip pocampus, the part of the brain responsible for memory. It leads to a shrinkage in the hippocampus. This reduced size has an obvious impact — a deficit in working memory — but it also

contributes to increased levels of depression and anxiety. The areas supporting the hippo campus, such as the dentate gyrus, often shrink too.

The dentate gyrus is respon sible for feeding information into the hippocampus and serves as the brain’s helper for learning and memorizing things. MRIs performed by neuroscientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development showed that in dividuals who were isolated and lonely had a dentate gyrus that had shrunk by an average of around seven per cent, lead ing to impaired learning and significant cognitive decline.

The shrinkage of these two parts of the brain has severe impacts on its own, but it also leads to an increased risk of other mental illnesses too. A smaller hippocampus, for ex ample, increases the impact that traumatic events have on the brain and leads to earlier onset of depression.

It is worth noting, though, that a number of these stud ies just show correlation, not causation — loneliness may not necessarily be the cause for this cog nitive decline.

Another part of the brain that is significantly impacted by loneliness and the stress responses it causes is the amygdala. The amygdala usual ly gets a bad reputation, since it’s labelled the centre for anx iety and fear, and some people assume we would be better off without it. But, really, the amygdala is responsible for processing various types of emotional stimuli, good and bad. It’s what comes alive when you fail an exam — but also when you find a joke funny and laugh.

Since the amygdala is so central to emotional processing and responses, it is also incredibly affected by stressful situations. Whissell told The Varsity that chronic stress literally “rewires the network which processes stress.”

“In the future, you respond differently, perhaps more strongly to stressors,” Whissell added. He explained that you become stuck in a loop where, any time there’s a stressor,

you respond quickly and get stressed rapidly, leading to your brain rewiring further to anticipate stress.

You can think of this stress response pathway like a forest, which starts with no discernible route through it. A stressor appears in the form of a lone hiker, walking through the forest to get from point A to point B, leaving not much of a trail behind. The hiker then posts about this forest in an online forum, which means more hikers travel through it, making it easier to notice the path and walk along it.

As you continue staying in that stressful environment, more and more hikers ap pear, until, eventually, there’s a constant stream of tourists and hikers walking along, disrupting the local ecosys tem and forming a path that makes it nearly effortless to walk through the forest.

The formation of this forest path is similar to how stressors

and neurotransmitters rewire your brain to make it easier to get stressed out each time you face chronic stress.

This response is also why we see people who are lone ly struggle to get out of that loneliness, no matter the help they receive. It isn’t just that they struggle to make friends or can’t socialize, but rather that they have been rewired to get stressed easier and become lonelier, making it hard to re verse these impacts.

While we can just look at the neuroscience and psychology of loneliness, it’s also import ant to consider the social aspect, which seems especially pertinent now, during the pan demic, when social isolation has become an important met ric. When we are affected by loneliness, many of us tend to push others away, despite needing that social interaction.

And, ultimately, loneliness affects us all. While there is much more to learn about the effects of loneliness in society, one thing is for certain: we can’t fight it on our own.

If you’re from Brampton, you either wear it on your sleeve, or you say you’re from Toronto — there’s no in-between.

From the perspective of someone who hasn’t lived in the GTA for most of their life, the Flower City might seem like a quaint suburb with a pleth ora of famous alums (Michael Cera, Tyler Seguin, Roy Woods, Alessia Cara, Tristan Thomp son — the list really goes on.)

If anything, you might assume that there was something in the water that made Bramp ton churn out celebrities like there’s no tomorrow. However, for people like me who grew up in and around the GTA, saying you’re from Brampton can often lead to ridicule.

I’ve actually seen Brampton jokes in the Twitch chats of

American streamers, which says a lot. Sometimes they’re jokes about the vast number of bad drivers in the city or about how everyone here dreams of being from Toronto. Others poke fun at Bramptonians who claim to be ‘gangsters,’ but live in mas sive houses with BMWs in the driveway — a stereotype also known as a “Brampton man.” The humour never seems to end.

And for the most part, these are just jokes — harmless hu mour meant to poke fun at yet another copy-and-pasted sub urban Ontario city. Cities like Hamilton catch their fair share of jokes too. However, when Brampton gets called names like “Browntown” and “Bram ladesh,” or when it’s referred to as a “ghetto,” the constant

barrage of comments becomes less of a joke and more of a racially motivated attack.

Brampton has a very diverse community: a big chunk of the population is of South Asian descent and the suburb is home to one of the world’s largest populations of Sikhs. Some see this diversity as something to attack, which is nothing short of ignorance.

Of course, Brampton is not immune to legitimate critique — one of its most glaring problems is its housing crisis. A rise in demand, caused by an increase in population over the last de cade, has sent housing prices skyrocketing. As a result, not only has homelessness spiked, but a predatory practice of over crowding people into a small house — which often affects

Writer: Angad Deol Photographers: Leroy Agholor & Caroline Bellamyvulnerable postsecondary inter national students — has taken root in the city. Some estimates place the number of illegally rented suites at around 50,000, which should be concerning for all citizens of Brampton.

Brampton also has to reck on with racism. For example, Black students in the Peel region’s schools face dispro portionate amounts of racism and are suspended much more compared to students of other backgrounds.

My closest friend in high school — and to this day — is Michael Osei-Ababio. Michael grew up as a Black person in a predominantly South Asian city, and his experiences of racism within Brampton are absolutely heartbreaking. “I found that it was very stressful to live in

[Brampton]. I can remember times in my childhood, up to middle school — even high school — I’d be visiting a friend, and before I’d go in, I’d have to ask if their parents were okay with Black people.”

He recalled times where he would be walking on a street with friends who were afraid about a relative spotting them with a Black person. No one should be fearful when walk ing with their friends just be cause of the colour of their skin, but many of my Black peers growing up shared the same experience. I can recall Michael telling me these sto ries as we walked to his place for lunch or during our spare period. He felt that it was like torture living in Brampton and his mental health suffered as a result.

When I asked him what he thought of the “Brampton man” stereotype, he said he feels it comes from an “obsession with wearing other people’s struggles as a costume.”

“The Brampton man is a character,” he said. “The Brampton man is in itself a caricature of what the Bramp ton man’s parents think Black people are.” When I heard him say that last part, I saw him potentially go through a mo ment of catharsis.

When I asked him how Bramp ton could improve on inclusivity,

Michael said he hoped to see a movement toward openness and ac ceptance. In high school, he found peo ple who were much more open-minded and progressive, and he hopes that more people can embrace cul tures that they weren’t exposed to growing up. Honestly, I was on the verge of tears when he told me that I made him feel more comfortable in high school.

After the Black Lives Matter protests that were sparked by the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020, Michael saw that more Bramptonians became more accepting.

Through progress comes justice, and I hope one day Brampton can be a place where everyone feels welcomed, and where families can live

comfortably both financially and socially.

In a few decades, perhaps Brampton will be a city that peo ple look to as a beacon of hope for suburbs everywhere — and I look forward to that day.

Across the world, national boundaries are generally funky and odd, but that’s especial ly true in Africa. The African continent is home to some of the most diverse nations in the world. Despite that diversity, some countries have sharp, geometrical borders — for example, Algeria, Mali, and Namibia.

That phenomenon is strange because ethnic groups don’t claim land in idiosyncratic geometric forms. Instead, they cluster in irregular fashions, influenced by various factors such as trade.

As a result, African borders encompass various ethnicities. Sometimes, in countries like Togo, there can be up to 100 ethnic groups in one country. In other cases, borders cut across ethnic groups. This border ar rangement creates scenarios where people share the same language — or at least, mu tually intelligible languages — yet have different national ities. That’s because Africans weren’t given the opportunity to organically develop their own sovereign states.

In what is historically known as the “scramble for Africa,” colonial powers such as France, Great Britain, and Portugal “scrambled” to cut pieces of Africa for themselves. In doing so, imperial powers robbed Af ricans of the historical agency to determine their own borders, explicitly creating a disconnect

between lived African realities and arbitrary borders.

However, the “scramble for Africa” went beyond the cre ation of artificial state lines; it also involved the imposition of the European nation-state model. As Kjell Goldmann writes, “The nation-state… is ‘one of the most characteristic European political institutions,’ developing over the centuries

from the late Middle Ages until the era of the French Revolu tion, first based on loyalty to a monarch or dynasty and then on a people with a common language and traditions.”

When nation-states are created, it is often the result of a power shift where a new nationalist movement takes power from an existing regime. France, Britain, and other Euro pean powers had their borders determined by wars and cultural differences. Their boundaries are therefore organic and relevant to the people they govern.

Meanwhile, on the African continent, those same European powers constructed artificial nation-states — a process that would later have implications for African nationhood and identity. The model they used requires a certain type of singular national ism to function. In Africa, for this nationalism to take hold, ethnic identity had to be significantly weakened so that the people could re-emerge as a “nation.”

The nation-state model is a recent invention, and that it’s definitely not the be all and end all of governmental struc ture. There are multiple ways

allowed to imagine themselves beyond the historic traditions of Europe?

The 1960s saw a wave of independence sweep over the African continent. Afterward, African leaders were left with the challenge of governing artificially constructed states. In many of these cases, many African states adopted the lan guage of the colonizer as one way to foster national identity, since the states themselves were devoid of any association with specific ethnic groups and languages.

How history shapes identity These historical processes have had consequences for my self-understanding as an African.

were born outside of the con tinent, my understanding of what it means to be Ivorian is quite hollow. Being Ivorian — apart from the attieké and plakali and sauce graine I very much enjoy — sometimes feels like a small and distant part of who I’m supposed to be. When I look at a map, my imag ined African identity doesn’t go beyond the borders of the Ivorian country.

aries, there are also linguistic similarities that I don’t share with other Akan Ghanaians because I don’t speak my in digenous language, Baoulé. the Akan ethnic group, which

claim this African identity as my own when I’m unable to speak my own language?

When my mother and my grandmother are on the phone, they converse completely in Baoulé, and I’m left to simply wonder what is going on during their conversation. There’s an element of generational divide in that: I feel like I am losing out on important parts of who I was supposed to be if I were rooted in my language.

To some extent, I do believe the language I speak influ ences how I understand my African identity. Just like the artificial boundaries imposed on Africans, my African identity sometimes feels decontextual ized and virtual due to colonial actions.

disparity between the two areas. St. James Town is considered one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the city, while Rosedale is con sidered one of the wealthiest. You can see this difference in the landscape when you visit these spaces. If you stand on the corner of Bloor and Sher bourne and look south towards St. James Town, you see a very ‘downtown’ view, in contrast to the bridge and abundance of trees that you see when looking north towards Rosedale.

neighbourhood within the city, but it is often regarded as ‘sketchy’ by people who have never visited. This reminds me of the broken windows theory: in summary, the theory that a place that looks unsafe pro motes dangerous activity simply due to its appearance.

Torontonians’ view of St. James Town is often attribut ed to the population of people experiencing homelessness who take shelter around the neighbourhood, as well as to the concrete jungle within its borders. This perception is fur ther promoted by the view that nearby Rosedale is luxurious in comparison to St. James Town.

I’ve spent 20 years living where St. James Town and Rosedale collide. As any Toronto local would know, there’s a sharp contrast between these two neighbourhoods that are just west of the Don Valley Parkway. St. James Town is known for its ethnically diverse residents, street art, and dense modernist high rises. Meanwhile, Rosedale is recognized for its enjoyable green spaces and its higher-in come population, which inhabits grand houses of diverse styles.

During my childhood, I used to play soccer and tennis and learned to ride my bike at Rosedale Park, just north of

my home. When I grew older and began exploring the city on my own during my free time, I would walk through St. James Town. There, I discovered restaurants and works of art close to my home and spent a semester volunteering at Art City on Sherbourne Street. The more time I spent in both neighbour hoods, the more the similarities and dif ferences between the two became explicit to me.

Now, I often review Toronto census data maps in my classes, which showcase the

However, the two neighbour hoods do share more character istics than one would expect. No matter how different they are physically, both spaces are shared and appreciated by the people who live there. They both hold community gather ings, such as the St. James Town Festival and Mooredale’s Mayfair in Rosedale. Each of these celebrations reflects the characteristics of the neigh bourhood and its values, and both of them build connections within the community, albeit in different ways.

St. James Town is a unique

But, in the end, both neigh bourhoods are filled with in teresting people, art, distinct architecture, and history. I truly recommend adventuring through both neighbourhoods and enjoying what they each have to offer.

Once upon a time, handwritten letters took days or even months to arrive in a recipient’s mail box. Now, emails are sent and received almost instantaneously via internet connection. There is no doubt that connectivity has made our lives more efficient than ever. But an overemphasis on speed has bred a generation of ‘right now’ consumers.

Many of us are willing to pay more in exchange for expedited delivery of goods or services — but could this phenomenon im ply that we have grown impatient as a society? In an attempt to find an answer to that question, I was struck by how excessive exposure to fast food symbols has translated into radical shifts in consumer behaviour, specifically in fast fashion.

Fast food is an iconic symbol of a modern lifestyle that val ues efficiency and immediate satisfaction. Obesity, diabetes, and a heightened risk of car diovascular disorders are some well-known examples of the health hazards associated with overconsumption of fast food. But there is far less attention directed toward studying the effect of fast food on other areas of life. We often intentionally save time that we would usu ally spend on our daily routines, such as meals, to make room for other activities. Counterintuitively though, data collected

from the US indicates that there has been no proportional growth in happiness corresponding to the increase in leisure time over the past 50 years.

Based on existing literature about behavioural priming, U of T researchers even suggested that the presence of fast-food symbols, like imagery, could condition people to display time-saving behaviours. They conducted a series of experi ments to test the hypothesis. One of their experiments mea sured impatience by changes in participants’ reading speed: although participants were under no time pressure in the experiment, their reading speed accelerated if they were exposed to fast-food symbols.

Furthermore, the studies showed that exposure to fastfood-related concepts impacts our decision making. Researchers tested this theory by dividing a group of undergraduate students into two cohorts. One cohort was asked to recall memories of the last time they ate fast food, while the control group was told to remember their most recent visit to a grocery store. Then, they were asked to fill out a marketing survey that asked them to rate the desirability of a set of products.

Students who were primed by fast-food concepts preferred time-saving products over less efficient-sounding alternatives.

For example, four-slice toasters were more popular than single-

— the here and now — often leads to multitasking, which prevents us from savouring the small pleasures in life.

One study conducted sev eral experiments to examine whether exposure to fast food culture reduces the happiness that people derive from plea surable experiences. The first experiment looked at whether differences in food packaging — food presented in ready-togo branded packaging or ce ramic tableware — influenced people’s enjoyment or ability to appreciate images of beauti ful scenery. Participants were shown a picture of nature, but one group of participants had been primed with exposure to fast-food packaging, and the other had not. Afterwards, the fast-food group had lower ratings of self-reported hap piness. As part of the same study, researchers also ran an experiment exploring whether exposure to fast food affects individuals’ ability to savour experiences. They asked par ticipants to listen to a melody, using self-reported impatience and the subjectively perceived length of the melody to mea sure whether they perceived the experience as longer and therefore less enjoyable. This trend was apparent in a follow-up experiment that also revealed a significant decrease in positive emotional response to an excerpt of music for par ticipants primed with fast food.

The idea that small pleasures offer a reliable path to happi ness is an established theory. Just as impatience stealthily erodes our appreciation of art, we seldom consciously pay at tention to how these seemingly insignificant moments of enjoy ment in life have an impact on our happiness.

So, in the future, it’s proba bly best to take a moment to weigh your wants and needs on an honest scale before you decide to click on the banner of a ‘sitewide flash sale.’

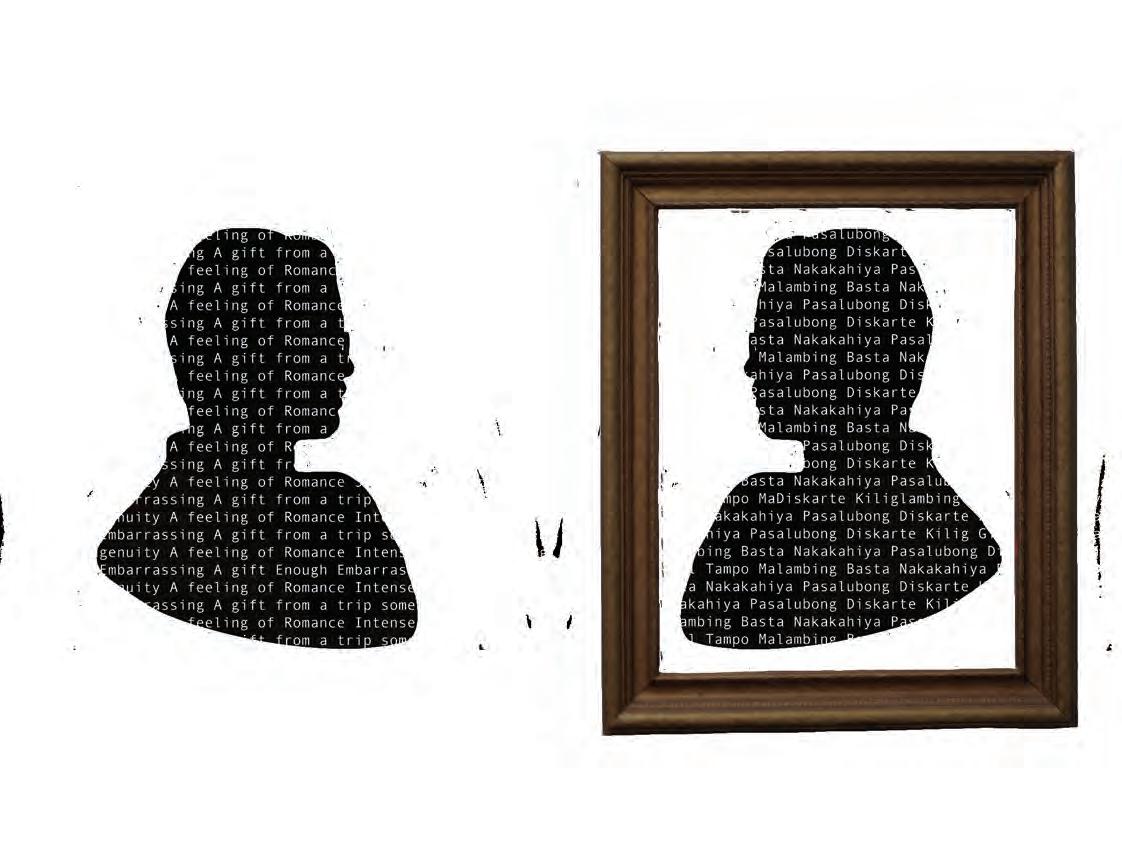

A bilingual speaker wrestles with the futility of telling things perfectly

Writer: Alyanna Denise Chua Visuals: Alyanna Denise Chua & Caroline Bellamy

One Tuesday morning, I was standing in line at a Tim Horton’s, my hair drip ping wet and the smell of chlorine clinging to my sweater. I was scanning the menu board, deciding whether to try something new or get something I al ready knew I liked, when I noticed the cashier.

Her skin was kayumang gi. The closest English translation of this word is ‘brown,’ but that’s mislead ing. The English language doesn’t have a word that decently captures this ex act skin colour, which is prevalent among Southeast Asians — a tone that’s mid way between the pale com plexion of most East Asians and the darker complexion of most South Asians. But Tagalog, the national lan guage of the Philippines, has a word for it — kayu manggi.

As I approached the front of the line, I heard the ca shier speak. Between the forceful pronunciation of her ‘r’s, the melodic quality of her voice, and the way she verbalized every vow el and consonant in every word she spoke, I could tell she was Filipino too.

It was my turn to order. I ordered a chicken wrap, then I asked her, in part just to make sure and in part just to start a conversation, “Are you Filipino?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Oy! Magkababayan tayo,” I said. (“Oy! We’re compatriots.”)

She nodded. I was ready to ask her which part of the Philippines she was from or how long she’d been working at Tim Horton’s. But she handed me my re ceipt and called the next person in line.

I stood to the side. I felt

desperate — at that point, I hadn’t spoken to anyone in Tagalog for a few days.

The first time I had to speak in English every day was when I came to Canada in 2019. I thought it would be a breeze; after all, I already read and wrote better in English than I did in Tagalog.

But conversing with oth ers, it turns out, is where I constantly meet my limits. My words in English may sound perfectly fine to oth ers — I often articulate my points well and successfully convey information — but they sound unvarnished to my own ears.

Here’s what I mean: I find English to be too direct and pointed. To myself, I sound clinical and even mechan ical whenever I use the language. My words sound more forceful. These qual ities are all great when I’m delivering a presentation or working in a team, but not when I’m trying to connect with the humanity that sur rounds me. To me, English is not as playful as Tagalog; I find it hard to dress the language down and make it more relaxed.

Tagalog speakers tack an endless number of par ticles to the ends of our sentences — “it’s good naman” (“it’s good”), “I’m okay lang” (“I’m okay”), or “that’s what they want eh” (“that’s what they want”). “Naman,” “lang,” and “eh” may not change the mean ing of these sentences, but without them, these sen tences lose much of their feeling, personality, and vigour. They lose much of their humanity.

My younger sister once told me that we switch our personalities slightly de pending on the language

that we speak in. I suppose it’s true, because when we communicate with each other, we don’t just ex change words — we also exchange who we are.

That scares me. With just a change of language, I be come a slightly different per son. English Alyanna is more assertive and direct, while Tagalog Alyanna is more spontaneous and witty.

I miss that second ver sion, and I wish that people here in Canada could meet her. But most of the time, she’s only accessible in Tagalog.

Sometimes, I mourn the fact that translating Ta galog-specific words and phrases into English will always be an imperfect en deavour. As a result, I also have to mourn the impos sibility of expressing some facets of my character.

One time, my roommate invited me to try some of the soup she’d made. But because she’d only made a small portion, I wanted to decline. I wanted to say, “Nakakahiya.” Encapsulat ed in this single Tagalog word is a sense of embar rassment and modesty, as well as a reluctance to incur a debt. The closest English translation of this is, “That’s embarrassing.” And so, that’s what I said.

It was the next best thing, but it didn’t even come close to my intended meaning. I suppose my roommate will never know that every time I say, “That’s embarrassing,” what I really mean to say is, “Nakakahiya.”

I have a Filipino aunt in Toronto who looks after me. Whenever I tell her, “I miss speaking Tagalog,” what I really mean to say is that I miss being fully able to convey what I mean

and having the person I’m speaking to understand the feelings and nuances of what I’m trying to tell them. I miss conversations where we are able to communicate the full scope and meaning of each other’s words, and therefore, of each other’s identities.

Whenever I tell her this, my aunt just nods and tells me to see her more often. I suppose she gets it.

But I also suppose that dwelling on all of these things will not do. I’ve been trying to accept the limits of language in human com munication; I suppose it’s because I have to.

Sometimes, I grieve the fact that the people I meet in Toronto will only ever know a cursory, approxi mate version of who I nor mally am. But sometimes, I also think that the people I know in the Philippines won’t be able to access this more assertive version of myself — a version who may be less quick to joke around with, but who can better stand on her own two feet.

Right now, I’ve come to settle for approximations. I am always hyperconscious of the nuances that I’m un able to communicate in En glish. I sometimes lose sight of the reality that, at the end of the day, I and the people I meet here in Toronto are still able to understand and connect with each other.

Maybe perfect communi cation is a futile goal. Maybe it becomes even more futile when one knows countless untranslatable words and phrases from another lan guage. Maybe this is the best I will ever be able to do.

One day, I will also make my peace with that. But for now, I guess, bahala na si Batman.

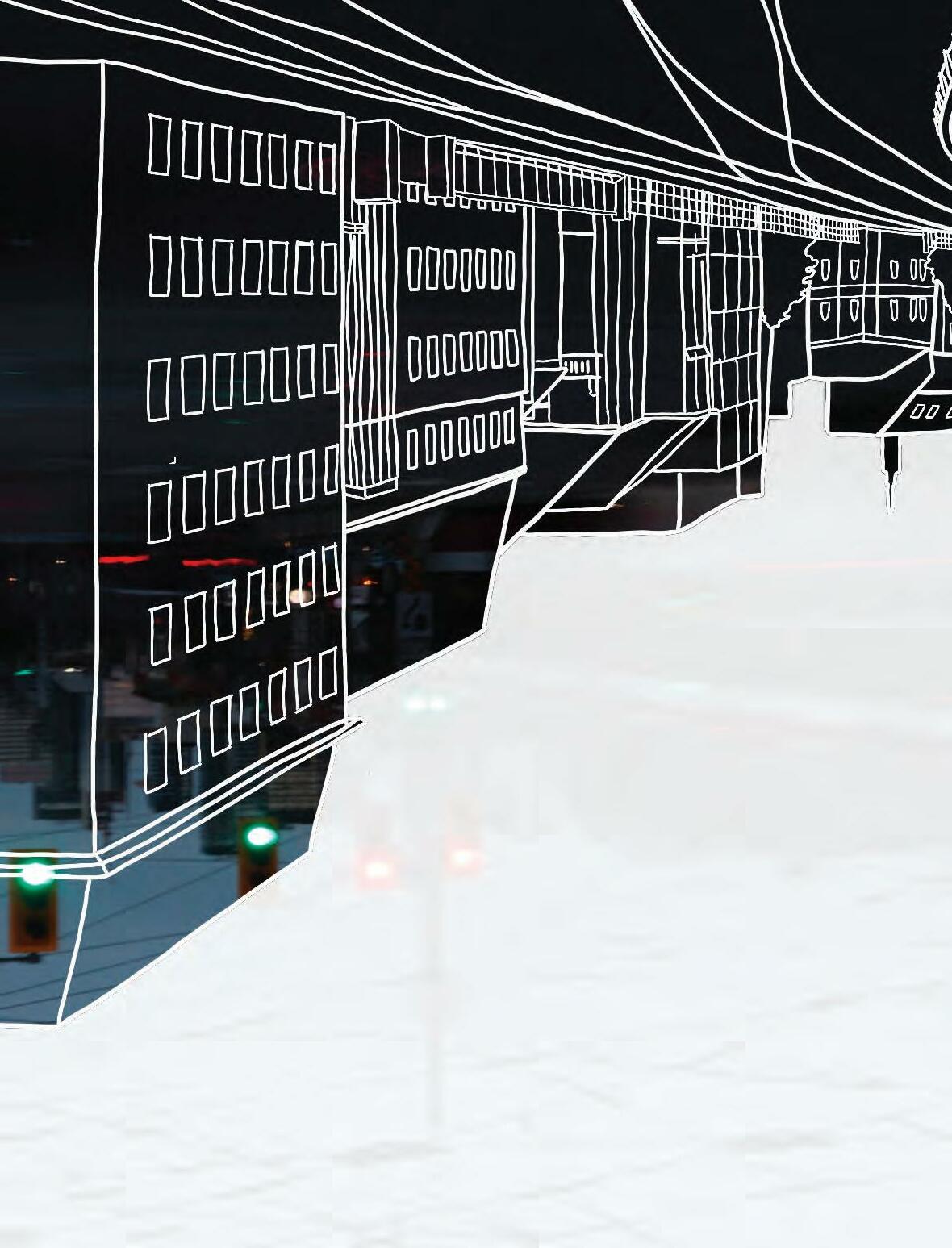

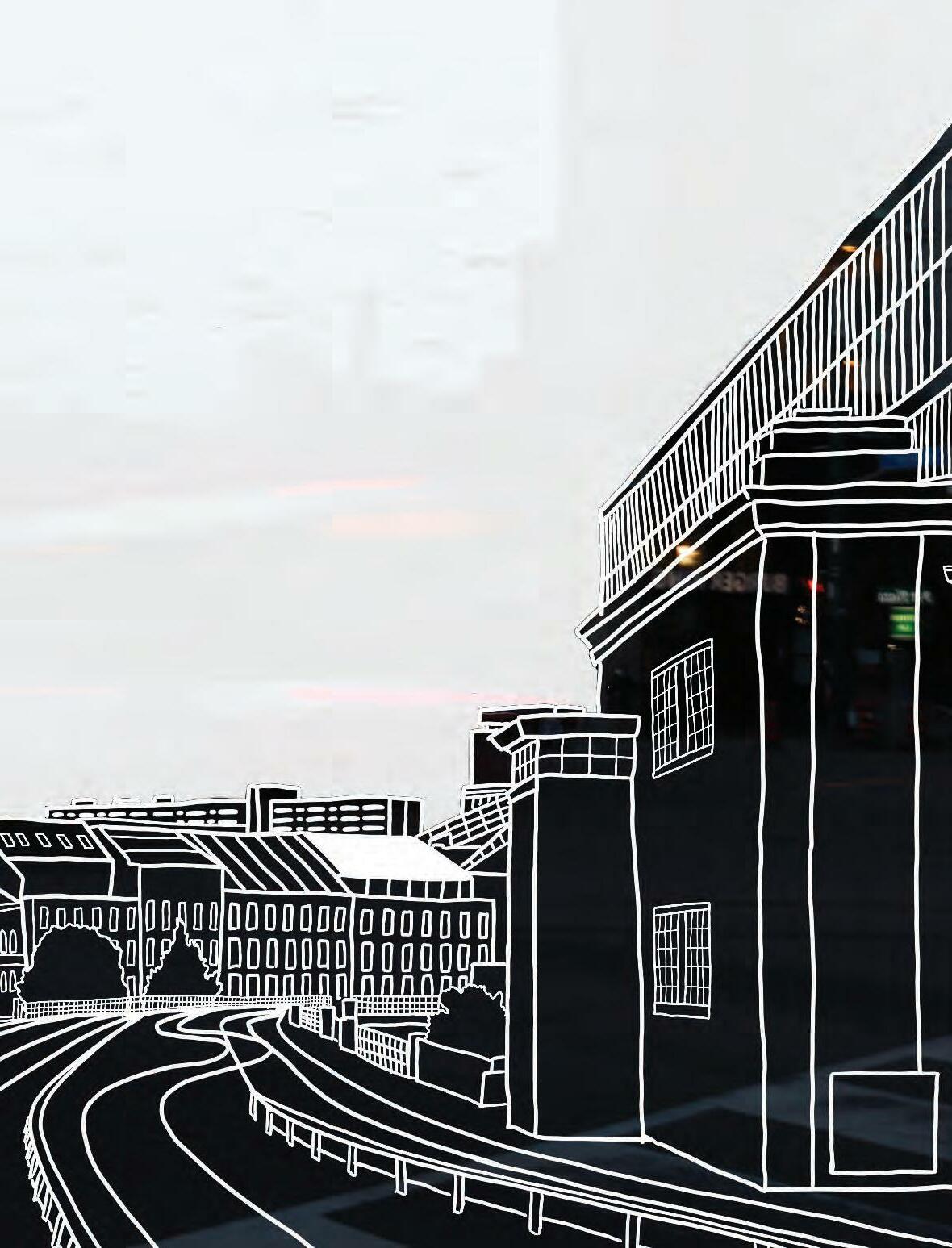

There’s a story I like to tell about two cities and a wall. This story is not a particularly interesting one — there’s no punchline or moral to drive it home. It is simply a series of facts, each falling in place one after the other. On August 13, 1961, the Berlin Wall went up overnight. Two U-Bahn and one S-Bahn lines that crossed under East Berlin territory were promptly armed with live

electricity and barbed wire, alerting would-be defectors of their certain demise. They called them ‘Geisterbahnhöfe,’ which translates to ‘ghost stations,’ because they came with all the lights still flickering. They’re a haunting sight. When the stations were reopened after the fall of the Berlin Wall, they were filled with cobwebs and cobble stones — the receipts of 28 years of wreckage and ruin. Today, if you go to Berlin, you can still see Checkpoint Char lie, the crossing point where would-be refugees lost their lives jumping to freedom on the other side. You can meet all the ghosts that never left — they’re still walking around on the platform and boarding trains every day, as usual. They just look like people now.

This is not solely a story about trains or walls — or about Ber lin, for that matter, for all of its uniquely fragmented history that lends itself well to tales like these. It is also a story about the momentum of motion — how

it drives our societies and how progress halts in its absence, for better or for worse.

But for now, let’s talk about trains, walls, and Berlin. The vivisection of the subway lines, the closing of the Brandenburg Gate, and the construction of the Berlin Wall were all collat eral damage from the greater sociopolitical issue of the Cold War. The trains stopped arriv ing in downtown Berlin under the same decrees that closed borders and installed spyware — the same laws that swept books off shelves and art off of gallery walls.

Freedom of movement is a di rect reflection of the freedom of choice. With freedom of move ment also comes questions about our freedom to choose when to move, where to move, and why. It comes with ques tions about what options are afforded to whom because of the choices that are made by the people and the powers that be. The luxury of movement is not a luxury afforded to all of us, even when transportation seems to be available.

Here in Toronto, for instance, the costs associated with public transport discourage

some people from making use of the system, who may need it the most. A quarter of recently surveyed lower-income respondents reported that they’d skipped buying food in order to pay their TTC fares; one half reported walking long distances to avoid paying unaffordable public transit fees. Even in a city like ours, which prides itself on development and democracy, it is clear that we still have a long way to go before we can all access the right to mobility and reclaim authority over our lives.

It is also obvious that, for all the trouble that surrounds it, our society and way of life depend greatly on movement. The pandemic has given us a clear view of a world halted in its tracks — of the monot ony and often dysfunction of motionless communities and cities. It has served as a re minder that not all of us have the autonomy over our lives to enjoy the necessary privilege of slowing down.

But not everyone has slowed down. It’s a desperate mea sure of these desperate times. There’s a bus line in Toronto — the 35 Jane route — that carves its path through the city’s north-western neigh bourhoods, which are mostly populated by working class,

racialized residents who hold essential jobs in other parts of the city.

When the pandemic hit, they had no choice but to keep work ing as they always had. The buses of the 35 Jane remained full in the morning and at night, despite the prohibitive costs of transit and the continued dan gers of the pandemic. Without the 35 Jane and all the routes like it, there are no cashiers at grocery stores, no warehouse staff packaging impulse buys, and no clean emergency rooms ready for the next big crisis. Without movement, there is no life as we have come to know it, and perhaps this too will be our undoing.

What comes next? When you consider only the matter of trains, the answer seems to be simple. Look to Japan, Sin gapore, or Sweden and you will find railway lines serving entire cities. You will find semi-af fordable tickets, nearly clean platforms with complete walls and doors, and stations painted to look like cotton candy and rainbows and Greek yogurt tins. The rest of the story becomes a little harder.

I have no answers to ques tions of freedom — freedom of movement or otherwise

— or to questions of neighbour hoods and cities and countries and borders, which sometimes emerge all together. I do not know how to take on systems of power, to give choice to the people, or to make our deci sions truly ours, and I am not in any way equipped to try.

But this is a story about trains, walls, and Berlin. It’s a story about Toronto and Tokyo, Singapore and Stockholm; of good luck and bad tidings; of old neigh bourhoods and new world orders; of borders crossed and paths not taken. It is a story about movement and momentum. It is a story about oppor tunity and choice, of the decisions we make and the ones made for us, and of nothing ven tured for noth ing gained.

And in the end, like ev ery other tale I tell, may be it was no more than a story of two cities and a wall.

Writer: Cameron Kerr Visuals: Caroline Bellamy

Writer: Cameron Kerr Visuals: Caroline Bellamy

Toronto used to be a city of rivers and creeks. In the area that is now U of T, we had our own river, which was known as Taddle Creek.

The river and the city are a dy namic duo that led the human race to civilization stardom. Rivers gave us our first meals, provided nutrients to our first crops, and powered our first industries.

But during the nineteenth century, we forgot about rivers’ importance and buried them underground for the sake of development. Now, in the concrete jungle that many of us call home, seeing a blade of grass or a stream of water is cause for celebration.

Toronto used to be a city of rivers and creeks. In the area that is now U of T, we once had our own river, which was known as Taddle Creek.

Taddle Creek’s past Taddle Creek’s story starts 13,000 years ago, when the Laurentide ice sheet made its last advance northwest toward Toronto. The glacier tore up sediment, shaping the landscape of southern Ontar io. Once melted, the glacier’s northwest movement lent all rivers in Toronto — including

Taddle Creek — a southeast flow.

The Taddle Creek area was first inhabited by Indigenous communities that moved into Toronto in 9,000 BCE. Today, this area is recognized as the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Missisauguas of the Credit, the Anishinabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples.

Taddle Creek gave them fresh water and fish, and then became even more important when corn was introduced to southern Ontario in 500 CE. In digenous communities shaped the creek’s banks into flood plains in order to create fertile soil to grow food. The river’s generosity allowed villages to grow until the start of European settlement in the mid-seven teenth century.

Initially, European settlers’ relationship with water was a continuation of Indigenous reliance on waterways. But soon, they discovered that the glaciers had moved large collections of sediment to the banks of rivers like Tad dle Creek. Brick, chimney, and drainage tiles could be made from those deposits. In 1796, Toronto’s first brickyard sprung up at Taddle Creek, meant to manufacture bricks for the city’s first parliament building.

By providing the city with the

foundation for development, Taddle Creek signed its own death warrant. European construction accelerated and population density increased. Our recip rocal relationship with Taddle Creek broke down, and a lack of sewage practices led com munities upstream to pollute Taddle Creek. By 1830, reports were talking about the awful smell of the creek.

Still, Taddle Creek became U of T’s river, and proved to be a centerpoint for student culture. Its importance to the U of T community increased even further when, in 1855, Taddle Creek was dammed in front of present-day Hart House to create McCaul’s pond.

Taddle Creek’s story starts 13,000 years ago, when the Lauren tide ice sheet made its last advance north west toward Toronto.

Taddle Creek and McCaul’s pond gave students a place to skate, fish, swim, and ponder by a riverbank. In November 1881, The Varsity reported that freshmen had been forced to dunk in Taddle Creek after an argument with senior students.

A few years later, in October 1883, The Varsity published a poem titled “To The Taddle, A Graduate’s Farewell.” It featured a student’s solemn goodbye to the creek, describing how “[Taddle Creek’s] poetic surroundings… are an education in themselves.”

Despite the world of rivers coming to an end, the students at U of T kept the last section of Taddle Creek alive.

It was fate that the power of politics and pollution would kill Taddle Creek. In September 1881, U of T put the problem of Taddle Creek’s pollution on its

Board of Management agenda. The university advocated for burying the river because of concerns for student health.

The City responded that the creek was on private property, so U of T would have to pay for some of the project. A report from The Varsity in December 1881 stated that the City’s proposed solution would cost $9,000, which is equivalent to around $220,000 today.

Unfortunately, pollution

worsened with the building of McMaster Hall — the pres ent-day Royal Conservatory of Music — in 1881. The building featured an open sewer placed beside Taddle Creek, even though open sewers had been discouraged since 1845. Fur ther reports were published in The Varsity in November 1881 and March 1883 describing the state of McCaul’s pond and the

pollution coming from Taddle Creek. At this time, the uni versity and the City were still debating payment.

Our solution was to bury the waterway. In May 1884, U of T signed off on the construc tion of a sewer system that would bury the creek under ground. This came after the introduction of Toronto’s first Medical Officer of Health, Dr. William Canniff, in 1883, and the release of new research on sewage and health by Dr. William Oldright. By 1886, Taddle Creek was lost to us. Its last few years had been tarnished by politics, pollution, and corner cutting.

It is surprising that a river that played a pivotal role in both Indigenous and colonial civilization was removed so quickly from our landscape. Today, it fuels our artificial wa ter cycle by transporting sew age and storm water through downtown Toronto.

Still, you can find evidence of Taddle Creek’s survival.

Originally, Taddle Creek

By 1886, Taddle Creek was lost to us.

If you walk from Casa Loma to U of T, you will find traces of the buried waterway.

flowed through present-day Philosopher’s Walk, down through Hart House and to ward College St. If you walk from Casa Loma to U of T, you will find traces of the buried waterway. Kendal Avenue makes an abrupt 90 degree turn just south of Bernard Av enue, following a similar turn by the creek. A few hundred meters further south, the St. George subway station uses multiple sump pumps to keep Taddle Creek’s water out of its tunnels. Down the block, the creek’s buried waters once

Our city is built on the backs of stories that are forgotten, such as the story of Taddle Creek.

flooded the basement of the Remenyi House of Music.

Finally, Philosopher’s Walk still follows the path of Taddle Creek from Bloor St to Hoskin Ave. The path’s landscape is similar to that of a river bank. At one of its lowest points, near the entrance at Hoskin Ave, stands a grand willow tree. Willow trees are an example of riparian vegetation, meaning that they can only grow near sources of water.

We may have cast the Taddle aside, but the willow tree is a reminder that it is still here.

The burial of Taddle Creek was not without repercussions: it

affected Toronto’s water man agement system. The city’s sewage system was construct ed in such a way that sewage tunnels would overflow into creeks and rivers, ultimately reaching Lake Ontario. But due to our rising population density and the decrease of non-paved urban spaces, the city needs to process higher amounts of sewage and storm water.

Currently, the city experienc es one sewage overflow every week, which results in flooded basements and contaminated water. In the coming decades, it will cost the city $1.5 billion to improve this system.

Ultimately, this problem stems from the moment we disconnected from the natural water cycle in the nineteenth century. We left the dynamic duo of city and river behind, and are witnessing the fallout of that today.

There is a solution, though: globally, some activists are promoting river daylighting, or the reexposure of rivers. This enables waterways to reestablish the natural water cycle. The soil and riparian vegetation that exists along side a healthy river can absorb water, reducing the load on the sewer system. That, in turn, reduces

flooding and property damage.

The City of Toronto has set a goal to preserve and re-es tablish a natural hydrologic cycle in the coming decades, and daylighting could be one way of achieving that goal.

Our city is built on the backs of stories that are forgotten, such as the story of Taddle Creek. If we want to break out of the concrete jungle, we must understand the stories of the past, recognize their impact in the present, and correct our mistakes. These stories may decide our city’s future.

If you or someone you know is in distress, you can call…

Maybe you’ve seen this phrase at the end of an article in The Var sity . Have you ever wondered what happens next?

Usually, when you call a helpline, you’re looking for immediate support. But if you haven’t called in to a helpline before, it’s not always clear what you should expect. That can make it nerve-wracking to wait on the other side of the line. Or, if you’ve called in before, you’ve still probably got some questions about how helplines work. It’s not like mental health services are known for their accessibility.

But hundreds of U of T students are still calling these helplines every month, and a lot of them are calling back multiple times in a row. They’re clearly getting something out of it.

So, maybe it’s worth looking at stu dent helpline experience in detail. What actually happens when you pick up the phone and dial in?

Two of the most common helplines around campus are Good2Talk and U of T’s in-house mental health service, My Student Support Program (My SSP). They’re both specifically de signed for postsecondary students, and the university likes to provide links to them in a lot of its mental health literature. They’re both ad vertized in similar ways — as places for immediate counselling or getting further mental health resources.

Almost all of the students who wrote to The Varsity to talk about their expe riences with mental health helplines had tried calling or texting Good2Talk at one point or another. Good2Talk is run by Kids Help Phone and some Ontario-specific mental health services,

and it’s often billed around campus as a chat line. It’s an anonymous helpline accessible through phone, text, and Facebook Messenger.

A lot of students also mentioned My SSP, which is a frequently ac cessed resource among U of T stu dents — around 650 to 850 students across U of T’s three campuses reach out to it every month, according to Jesse Poulin, current director of the keep.meSAFE program, which manages My SSP.

keep.meSAFE was founded by guard.me, a health insurance com pany that provides services to many international students and faculty. According to Poulin, it started as a program that specifically targeted international students. guard.me noticed many students were using insurance to access emergency mental health care services, so it launched keep.meSAFE as an early intervention mental health service that international students could

access before they reached a point of crisis. Since then, the program has grown to cover domestic stu dents as well.

In light of its original purpose — to support students before their situation is dire enough to require emergency mental health services — it’s probably no surprise that My SSP seems to focus heavily on stressful school situations and pro viding students with tools outside of immediate helplines.

“The top issues that we see, time [after] time… are things like stress, anxiety, [and] depression. Often times in that order,” said Poulin, in an interview with The Varsity “Those are what we’re really here for. And if students have more se rious issues, we can support them and guide them to more appropriate long-term support.”

When you call or text My SSP for the first time, you can expect to go through some intake questions with a responder — things like your name, your school, what

language you’d prefer service in, and why you’re calling. In most cases, you’ll then be redirected to a coun sellor. A session with a counsellor will usually last an average of 45 minutes, but, according to Poulin, there’s no strict limit on your call time. If you want further support, you can book a series of ongoing virtual check-ins with the same counsellor.

“[The counsellor will] want to un derstand what the issue is and give the student practical tools to help them manage whatever it is they’re worried about,” said Poulin. “It’s really issue-driven — we do want to focus on solutions. It’s not talk therapy.”

Barriers to access My SSP responders are licensed counsellors trained in chat or tele phone counselling. Poulin stressed that keep.meSAFE has made a spe cific effort to hire counsellors with a variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds, located in different countries, so that international stu dents who are currently living

outside of Canada can still get mental health service within their jurisdiction.

Whether you’ll be able to find a counsellor that meets your specific needs, however, often depends on who’s available. keep.meSAFE cur rently serves 100 different Canadian postsecondary institutions, drawing upon a rotating network of counsel lors. The exact number of responders available at any given time varies on the day and the time — students seem to call in the most in the evenings, for example, and call numbers tend to peak on Wednesdays every week — but Poulin says that, at peak call times, there are usually hundreds of counsellors available.

Even so, many students have had issues accessing My SSP’s services. Some felt that, after a certain num ber of calls, respondents started to hint that they should really be using other services.

Other students have report ed having trouble connecting to operators at all. Vy Le, a firstyear student in media studies at UTSC, wrote to The Varsity that she’s called both My SSP and Good2Talk before, and she’s sometimes had trouble reaching a helpline responder. “Some times no one would be there to respond to my call. Other times, it took quite a long time still to get connected to a counsellor,” she wrote.

Although Le did eventually reach a responder, she some times found the length of the intake process discouraging. “When you’re too mentally ex hausted, it can be difficult to even talk to someone or prop erly engage in a conversation,” she explained. Overall, although she’s had good experiences with these helplines, she wouldn’t necessarily recommend them to someone experiencing a panic attack, or who needs immediate help, given the time it can take to reach a responder.

Naaz Sibia is a fifth-year

computer science specialist at UTM. On a large Discord server that she runs for UTM students, she frequently sees students who are in severe distress, venting about their mental health. Since November, almost once every two weeks, she’s had to reach out to students who seem like they may need immediate help.

Since she’s not a trained mental health professional, she often tries to refer students to resources like My SSP. Many of the students she’s talked to, though, have had a hard time actually getting connected to a professional.

“Generally, they had to wait from about 30 minutes to even three hours, and then eventually what ended up happening is they would have a break down and they just switch [the phone] off. There were times when they did get through and the person just said, ‘We don’t have enough people to take you at the moment,’ ” she said.

“It’s taking a lot of encouragement to [get students in crisis to] even make that call,” she said. “It would be nice if they didn’t have to hear that

there aren’t resources to help them.”

Both My SSP and Good2Talk have a need-to-disclose policy, where if an operator thinks that a student’s life may be in danger, they are required to report it to emergency services. Poulin says, however, that no matter what happens on a My SSP call, U of T will never be informed of it without the consent of the student.

A number of students wrote to The Varsity to talk about their experi ences with helplines, and most of the students who reported having positive experiences had primarily called or texted to talk to someone in a time of acute stress or crisis.

Syed Hussain Ather is a PhD stu dent in medical sciences, and he’s mostly gone to helplines to find a place to talk. In an interview with The Varsity , he said that when he wants to talk through heavier or more personal issues with someone, he’s sometimes worried about burdening his friends with stress they aren’t

trained to deal with. Calling in to My SSP or Good2Talk is an easy way for him to be able to work through his feelings with a trained professional.

Padmaja Rengamannar, a fourthyear student in journalism and polit ical science, has called Good2Talk a number of times in her four years at U of T. “It’s always nice to have a service that helps you get through and anchor you through crisis sit uations,” she told The Varsity in an interview. “That’s always been my experience with Good2Talk.”

Good2Talk has become her helpline of choice, because she appreciates the anonymity, and finds that it tends to have shorter wait times. She’s gotten hold of counsellors in as few as 10 to 15 minutes, and she remembers waiting up to an hour to talk to a re sponder during finals season, when the line is at its busiest. With My SSP, she’s found that it has regularly taken her a couple of hours to connect.

Although she usually calls in with immediate, short-term concerns, Good2Talk has also redirected her to other mental health resources in the community that she can access on a long-term basis. Counsellors have taught her coping strategies that she uses in her everyday life, and she’s used their advice to get better at setting boundaries for her own mental health. She’s received words of advice and comfort on crisis lines that have really stuck with her, which she comes back to again and again.

Calling into Good2Talk so often has even helped her get better at talking about her mental health.

“It’s hard work to share your story over and over again,” she admitted. “[But] I know myself a lot better. I’m able to share my story.”

Of course, not all students who have called into Good2Talk have had good experiences. MacKenzie Stewart cur rently works for the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, but he finished his undergraduate and master’s degrees

at U of T. When he was still an under graduate student, he had a partner who was hospitalized for mental health reasons. Stewart was having a hard time processing the situation and figuring out what to do about it, so he called into Good2Talk, which he’d seen advertized around campus.

When he reached out to someone, though, he felt like the counsellor was very dismissive of all his prob lems. “I don’t think they asked me any personal information in terms of my own self, like, what was I hoping to get out of the call? What did I need?” Stewart explained, in an interview with The Varsity. “I feel like it was me explaining… the circum stances I was there for, and them just trying to be like, ‘But there’s other places you can go than here.’ ”

What’s more, Stewart, who is a trans man, was frequently misgen dered by the counsellor. He explained to them that his boyfriend was in the hospital on suicide watch, and that he was scared for him. “They were just like, ‘Oh, but all girls have problems with their boyfriends. It’s okay.’ ”