thevarsity.ca

thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity

the.varsity the.varsity The Varsity

Jadine Ngan editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Makena Mwenda creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Nawa Tahir managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Sarah Artemia Kronenfeld managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Angad Deol online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Talha Anwar Chaudhry copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Khadija Alam news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

Shernise Mohammed-Ali comment@thevarsity.ca

Comment Editor

Janhavi Agarwal biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Alexa DiFrancesco features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Marta Anielska arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Sahir Dhalla science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Mekhi Quarshie sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Caroline Bellamy design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Andrea Zhao design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Vurjeet Madan photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor Jessica Lam illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration Editor

Maya Morriswala video@thevarsity.ca

Video Editor

Aaron Hong aaronh@thevarsity.ca

Front End Web Developer

Andrew Hong andrewh@thevarsity.ca

Back End Web Developer

Safya Patel deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Lexey Burns deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Jessie Schwalb assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Al Aref Helal utm@thevarsity.ca

UTM Bureau Chief

Alyanna Denise Chua utsc@thevarsity.ca

UTSC Bureau Chief

Emma Livingstone grad@thevarsity.ca

Graduate Bureau Chief

Ajeetha Vithiyananthan, Kyla Cassandra Cortez, Lina Tupak-Karim

Associate SCEs

Alana Boisvert, Selia

Sanchez, Tony Xun

Associate News Editors

Isabella Liu, Eleanor Park

Associate Comment Editors

Alice Boyle, Maeve Ellis

Associate Features Editors

Madeline Szabo, Milena Pappalardo

Associate A&C Editors

Seavey van Walsum, Salma Ragheb

Associate Science Editors

Alya Fancy

Social Media Manager

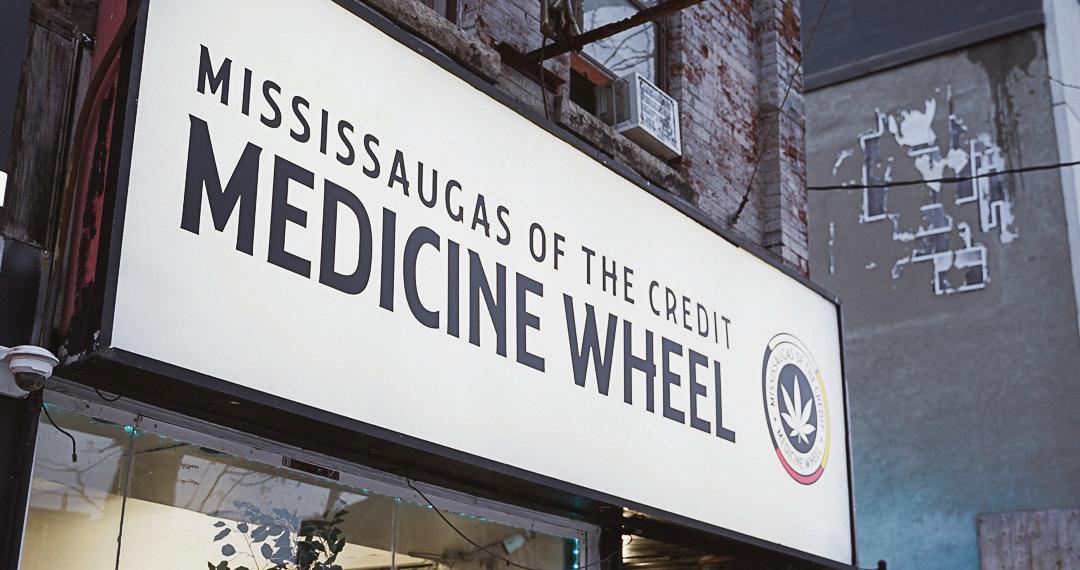

e Varsity would like to acknowledge that our o ce is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. erefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

No one on The Varsity’s masthead — our core editorial team — is Indigenous. As settlerCanadians, immigrants, and international students, we can’t speak for Indigenous students, staf, or faculty.

Our staf, which includes anyone who has contributed to the paper at least six times, includes very few, and possibly no, Indigenous writers. This estimate is based on our yearly internal demographic survey: in the 2021–2022 academic year, none of the respondents identifed as Indigenous. During each of the two years prior, we had one Indigenous person on staf who responded to the survey. (We haven’t sent out our internal demographic survey for the 2022–2023 year yet, but plan to do so in the coming month.)

These numbers mean there are gaps in The Varsity’s structure. We have heard over the years that our policies and practices are not equitable and inclusive. In addition, we are often unaware of important context and may miss the stories important to Indigenous peoples in the U of T community. This means that Indigenous students do not fnd themselves represented in our pages or our organization structure.

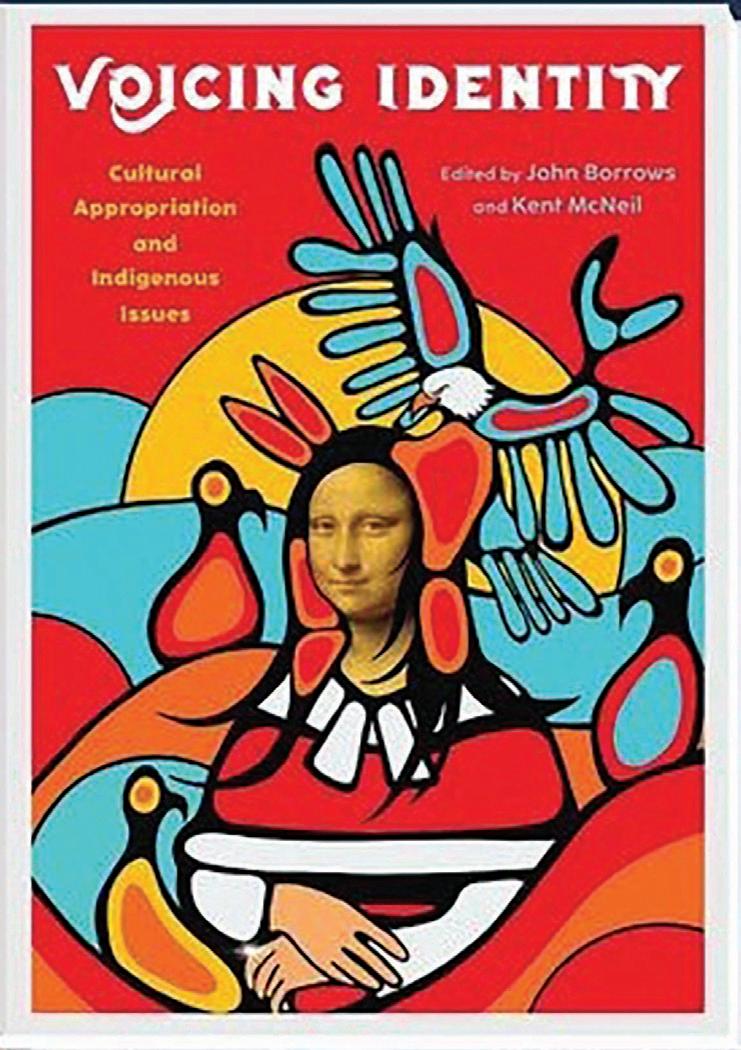

When non-Indigenous people report on Indigenous stories, that reporting is not always respectful to the people covered. In addition, Indigenous peoples and their stories are underrepresented in Canadian media at large. That is why The Varsity is determined to make more space for Indigenous contributors. It’s also why we wanted to dedicate an issue to Indigenous stories and coverage.

frst time The Varsity has gathered enough stories to release an Indigenous Issue — and that’s something we’re not proud of. A dedicated focus on Indigenous peoples in our pages is long overdue.

We’re making this a special issue so we can compensate contributors for their labour — something that often isn’t within our budget as a student newspaper. For this issue, we’ll be paying Indigenous contributors honoraria amounting to around $600 in total. The Varsity committed to spending at least $1,000 on this issue, so we’ll donate the rest of that money to an Indigenous organization, which our masthead will select in the coming days. We’ll update the online version of this article when we’ve done so.

Looking ahead, we don’t want this Indigenous Issue to be a one-time initiative. This issue represents a broader commitment to covering Indigenous communities at U of T and in the GTA. We hope that future Varsity editors will build upon that commitment for years to come.

And we don’t want to set a precedent that The Varsity pays attention to Indigenous peoples and stories for one issue a year. We are committed to regularly publishing stories about, for, and — hopefully, more and more — by Indigenous members of the university community. Both mainstream and student media have harmed Indigenous communities and continue to do so today. We are complicit in that harm — so we are also committed to taking more care.

barriers, but also stories of hope, community, and celebration. We need to approach community interactions in a way that meets the expectations of Indigenous students, staf, and faculty. We have to improve our editing and fact-checking processes to anticipate Indigenous worldviews and stories, and we need to include Indigenous voices in non-Indigenousspecifc coverage. We also need to continually revise our Equity Guide to improve our practices for reporting on and with Indigenous communities.

We will make mistakes as we journey through the early stages of this work, and as those arise, we will take responsibility for them. We welcome feedback — regarding this special issue, or about The Varsity’s initiatives to improve our Indigenous coverage in general. If there’s anything you’d like to share with us, please reach out to Jadine Ngan at editor@ thevarsity.ca.

Down the line, we hope there will be a Varsity team where multiple Indigenous students with a variety of lived experiences have a stake in leadership and decision making. We hope The Varsity will become a newspaper that builds and maintains reciprocal relationships with various Indigenous community members and covers Indigenous stories with the care and basic competency they deserve. We are not yet that version of The Varsity. But we hope we are making a step, even if only a small one, toward it — and even if The Varsity meets these aims, we know there will still be work to do.

Kunal Dadlani, Alaysha Merali, Hargun Rekhi Associate Sports Editors

Georgia Kelly, Andrew Ki

Associate B&L Editors

Arthur Hamdani, Johanna Zhang, Spencer Lu Associate Design Editors

Cheryl Nong, Biew Biew

Sakulwannadee Associate Illo Editors

Zeynap Poyanli, Nicholas Tam, Augustine Wong

Associate Photo Editors

Vacant

Associate Video Editors

Lead Copy Editors: Ozair Chaudhry, Linda Chen, Jevan Konyar, Bella Reny, Momena Sheikh, Nandini Shrotriya, Camille Simkin, Kiri Stockwood, Miran Tsay

Copy Editors: Andrea Avila, Gene Case, Selin Ginik, Ikjot

Grewal, Jane Kang, Victoria Paulus

Designer: Averyn Ngan

Cover: Evelyn Bolton

Backpage: Lindsay Bain

BUSINESS OFFICE

Parmis Mehdiyar business@thevarsity.ca

Business Manager

Ishir Wadhwa ishirw@thevarsity.ca

Business Associate

Rania Sadik raniasadik@thevarsity.ca

Advertising Executive

Abdulmunem Aboud Tartir atartir@thevarsity.ca

Advertising Executive

We’ve been trying to publish an Indigenous Issue at The Varsity for at least the past two years. After several years of efort, this is the

We have a long way to go. We need to ensure that each year’s masthead team learns about the histories and diverse cultures of the Indigenous peoples that we cover. We need to report on a wider range of stories about Indigenous peoples — stories about challenges and

Evelyn Bolton Varsity Contributor

When creating this piece, I considered the importance of an Indigenous-centered issue. I wanted to convey in my illustration how Indigenous students are entering a new age of representation and recognition. I drew the fgure to be armed with culture. She is dressed in a ceremonial ribbon skirt and carries a hand drum. The buildings were inspired by the buildings on Bloor Street West facing east at sunrise.

I would like to thank Zoe Neilson for modeling for my reference photos.

We are especially thankful to Shannon Simpson, director of U of T’s Indigenous Initiatives, for sitting with The Varsity to talk about U of T’s work on Indigenous initiatives in the past few years.

Follow this icon through the issue to see Indigenous coverage.

The Varsity is excited to announce that we will be holding a Winter Open House on Thursday February 9, from 12-6 PM. You’ll be able to interact with the masthead of your favourite student newspaper, and learn more about getting involved with us. We look forward to meeting you, and perhaps convincing you to give us a shot at being your next extracurricular activity.

NOTE: Visitors will be asked to wear a face mask in our office upon entry.

Emma Livingstone Graduate Bureau Chief

Emma Livingstone Graduate Bureau Chief

U of T ofers various resources for Indigenous students, spread across various platforms and divisions. Each U of T campus includes a separate centre focused on providing resources and hosting events specifc to Indigenous community members; UTSG is home to Indigenous Student Services, UTM to the Indigenous Centre, and UTSC to the Indigenous Outreach Program. The Varsity compiled a rundown of academic, cultural, and fnancial resources for Indigenous members of the U of T community.

First Nations House

Indigenous undergraduate and graduate students attending all three campuses can access academic services at First Nations House (FNH), on the third foor of 563 Spadina Ave.

FNH provides support for Indigenous applicants to U of T and current students in the form of academic advocacy, fnancial advising sessions, and tutorial accommodation services. Some faculties and programs, including the Faculty of Law and the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, also provide program-specifc academic support to Indigenous students. The FNH also houses the First Nations House Bursary, which is awarded to undergraduate Indigenous students who demonstrate fnancial need.

FNH hosts an orientation for incoming Indigenous students in September and events and programs for Indigenous students throughout the academic year, including traditional talking circles, a career fair, and workshops. It also hosts Indigenous Education Week, which is an annual

tri-campus event in October. The week features programs and events highlighting Indigenous art, histories, and ways of knowing. Additionally, Indigenous community members can meet with Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers for traditional teaching and advising at all three campuses.

Indigenous students can also participate in the FNH Student Advisory Committee, which collaborates with staf at FNH to develop programming and strategic initiatives.

Indigenous Research Network

The Indigenous Research Network (IRN) provides resources and support for members of the university community. These include training on Indigenous research methods and ethics, information about securing research funding, connections to Indigenous communities, and cultural and spiritual support for individual researchers.

The IRN also provides research supports to Indigenous communities, connecting them to U of T researchers who specialize in Indigenous research, facilitating networking opportunities with other Indigenous communities, and giving methods and ethics training.

Indigenous House

At UTSC, Indigenous House serves as a space for celebrating Indigenous ways of knowing and provides support to Indigenous community members. The Indigenous Outreach Program at UTSC also hosts events, including a beading circle and language lessons.

Indigenous Centre

The Indigenous Centre, located at UTM, provides resources and support for Indigenous community members. They also host events, including the upcoming All-Nations Powwow on March 25, 2023.

Financial Aid

The university ofers scholarships and bursaries for Indigenous undergraduate and graduate students at all campuses.

In addition to the FNH Bursary, the Indigenous Student Bursary is available to all undergraduate students based on fnancial need. Indigenous students who are Canadian citizens or permanent residents can access the Bennett Scholars Bursary based on fnancial need.

U of T undergraduate scholarships based on achievements in academics and extracurriculars include the Gertrude Elgin Robson Scholarship for Indigenous Students, the Dr. Lillian McGregor Indigenous Award of Excellence, the Marilyn Van Norman Indigenous Student Leadership Award, and the President’s Award for the Outstanding Indigenous Student of the Year.

The School of Graduate Studies (SGS) provides awards for Indigenous graduate students pursuing a PhD-track program through the Inclusive Excellence Admissions Scholarships for Master’s Students. This three-year pilot program aims to diversify academia and provide fnancial support to students from underrepresented groups in academia. As part of the pilot program, the SGS will provide 100 admission scholarships to students, each valued at $15,000. The SGS also provides an Indigenous Travel Grant to assist Indigenous students with travel expenses associated with participating in research or academic conferences.

A more comprehensive list of scholarships and bursaries — including program-specifc awards and external awards, as well as application instructions and deadlines — can be found through U of T Student Life.

Lexey Burns News EditorIn 2016 and 2017, Lakehead University and Trent University each implemented a policy that required all undergraduate students to take at least one 0.5 credit course focusing on Indigenous content before receiving their degree. Laurentian University implemented a requirement for all students completing a Bachelor or Arts and Bachelor of Commerce to also complete at least three credits, equivalent to 0.5 at U of T, of Indigenous content.

Some U of T community members, like Jefrey Ansloos — an associate professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), who is a Canada research chair in Critical Studies in Indigenous Health and a member of the Fisher River Cree Nation — believe that integrating Indigenous-focused program requirements at U of T could be benefcial toward students’ overall education.

In 2017, the U of T Truth and Reconciliation Steering Committee released its fnal report, which called on the university to integrate Indigenous curriculum “throughout all levels and sectors of U of T, ensuring that the content is relevant and sustainable.” In the wake of the report, the U of T administration publicly committed to include signifcant Indigenous curriculum content in all of its divisions by 2025.

Currently, English students at UTM and the Faculty of Arts and Science must receive at least 0.5 credit in Race, Ethnicity, Diaspora, Indigeneity or 0.5 English credit in Indigenous, Postcolonial, Transnational Literatures, respectively. The uni-

versity encourages students in Canadian Studies to enroll in at least one out of a list of Indigenousfocused courses.

In an email to The Varsity, Ansloos indicated that he believes the university should expand Indigenous course requirements, particularly for undergraduates. “[The] idea of a required course at the undergraduate level, at this point in Canadian history, makes a lot of sense and is entirely feasible,” he wrote.

OISE has designed Indigenous elective courses and is considering putting some requirements in place. However, Ansloos brought attention to the fact that requiring Indigenous-focused courses “is not a one-stop solution.” He wrote that he does not believe every graduate program should require Indigenous course work. Instead, he believes the university should require graduate students to take Indigenous courses if they seek to enter a sector directly cited in the national Truth and Reconciliation Commissions Report, such as the legal, social, educational, and health-care sectors.

U of T’s response

In September 2019, U of T named Susan Hill, the director of the Centre for Indigenous Studies, and Suzanne Stewart, the director of the Waakebiness-Bryce Institute for Indigenous Health at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, as academic advisers on Indigenous curricula and Indigenous research, respectively.

In an interview with U of T News, Stewart said that she aimed to prompt researchers to be more conscious of how Canada colonized Indigenous peoples and colonization’s impact in shaping Canada’s society today. Stewart highlighted the privileges colonization has presented to all nonIndigenous Canadians, especially individuals in

research positions.

In the same interview, Hill expressed the benefts of educating students about diferent historical texts through their appropriate lenses and contexts, which Hill believes is crucial to ensuring Indigenous perspectives are considered within courses.

In an interview with The Varsity, Shannon Simpson, senior director of Indigenous initiatives at the Ofce of Indigenous Initiatives, explained that discussions about implementing an Indigenous course requirement have been ongoing for several years. “It is a bit of a challenge, with all the diferent departments and divisions and the way that they have degree requirements,” she said.

“Something we have talked about a lot is that there might be more value at U of T to have content built into curriculum instead of requiring a course,” said Simpson. She highlighted that there are pros and cons to mandating courses, the biggest con being that students might see learning about Indigenous peoples as a requirement and receive fewer benefts from the experience.

In May 2022, Françoise Makanda, the senior communications strategist from the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, published an article about integrating Indigenous health into the Public Health & Preventive Medicine Program, which has been in progress for the last three years. The program launched as a pilot in fall 2021.

Dawn Maracle, a Master of Education student from OISE who is Mohawk from Tyendinaga Mo-

hawk Territory, explained that, “Canada is woefully behind” in regard to incorporating Indigenous content into the program curriculum.

Maracle explained that people throughout the U of T community “were fghting” to have an Indigenous course in diferent programs approximately 30 years ago.

“We should be far ahead of that. There are Indigenous issues to consider in public health as well as in many other topics,” said Maracle.

In 2014, U of T introduced the International and Indigenous Course Module, to allow students to learn about Indigenous history and issues outside of the classroom. In 2017, students visited Hawaii as part of the course module to learn about multiculturalism and decolonization strategies.

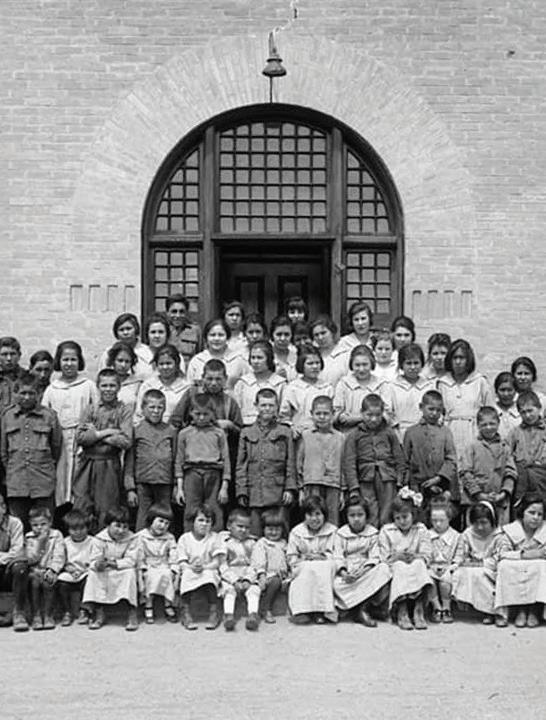

Over reading week in November 2022, a group of undergraduate students travelled to the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, as part of the course module. Students listened to the stories of residential school survivors and visited monumental sites from the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre, including a chapel and graveyard.

“When we learn in the classroom, we have an emotional bufer,” said Lydia Dillenbeck, a frstyear social sciences student and member of the University of St. Michael’s College. “We discuss and analyze serious topics without fully realizing their impacts. At Shingwauk, that emotional buffer was stripped away.”

With fles from Nawa Tahir.

A compilation of academic, cultural, and fnancial services at U of T

The Breakdown: Why only some programs require Indigenous courses

Requiring Indigenous-focused courses “is not a one-stop solution”

Deputye o ce of First Nations House. SUMAYYAH AJEM/THEVARSITY First Nations House. IRIS ROBIN/THEVARSITY

In 2017, U of T’s Truth and Reconciliation Steering Committee (TRSC) released a report that built of of the work of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In addition to highlighting the university’s role in forcing the assimilation of and perpetrating violence against Indigenous people, the report included 34 calls to action. In the report, the steering committee urged the university to commit to the long process of reconciliation.

Jessie Schwalb Assistant News EditorThe report reads that, “This report is but a beginning for the University of Toronto of what will be a long set of challenges, and yes, struggles.” The report quoted Nobel Peace

Consider building a dedicated Indigenous space at UTSG.

In 2020, U of T unveiled a design proposal for the Indigenous Landscape at Taddle Creek, located on the Hart House Green. The space marks the course of Taddle Creek — which ran from the current day intersection of St. Clair Ave. W and Bathurst St. and served as a fshing and gathering place for the Mississaugas of the Credit and other peoples before settlers buried the creek in the 1800s.

The design, created in consultation with many U of T community members, features a gathering area, signage with information and stories, benches, and a variety of tree species.

Consult with local Indigenous communities to develop a strategy to fund more Indigenous public art across all three campuses.

Since 2017, U of T has commissioned several pieces of artwork across U of T’s campuses, including the Tree Protection Zone, a work of street art located in front of Hart House that eight Indigenous artists created.

In 2019, Animikiik’otcii Maakaai, UTSC’s former Indigenous artist-in-residence, unveiled a solo exhibition featuring pieces focused on storytelling and ceremony. Mikinaak Migwans, a Faculty of Arts and Sciences professor, multimedia artist, and Anishinaabekwe of Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation, joined the Art Museum at University of Toronto as curator, Indigenous contemporary art in 2020.

Begin building Indigenous spaces at UTM and UTSC.

At UTM, U of T erected a tipi on the feld outside of Maanjiwe nendamowinan (Mahnji-way nen-da-mow-in-ahn), the building that houses the campus’ humanities and social sciences departments, which is more commonly referred to as MN. The tipi is used for various programming and ceremonies. In 2021, the university began constructing the Indigenous House on the UTSC campus, which will support various Indigenous ways of learning and knowing. The building will be surrounded by gardens and will overlook the Highland Creek Ravine.

Begin identifying and naming appropriate spaces across U of T’s campuses using Indigenous languages.

Various faculties have incorporated Indigenous languages into their signage, notably the Faculty of Law, which installed signage outside of the Indigenous Law Students’ Association ofce. These include Kwak’wala, spoken in 15 First Nations on the Northwest Coast of Turtle Island; Oneida, a Haudenosaunee language spoken in the Northeast; and Cree, an Alogonquian language family spoken in southern Canada. In 2019, U of T collaborated with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation to name the newly renovated humanities and social sciences building Maanjiwe nendamowinan, which translates to “gathering of minds” in Anishinaabemowin.

The designs for all renovations or new buildings should take smudging into account.

Smudging is a practice in multiple Indigenous traditions, where individuals burn herbs or plants such as sweetgrass, sage, and cedar as a means of purifying themselves or a space. Multiple rooms across U of T are preapproved for smudging. The renovated William Doo Auditorium, located in New College, includes smudging rooms. The UTSC Indigenous House will use heat sensors instead of smoke detectors throughout the building to allow for smudging.

The provost should hire a signifcant number of Indigenous faculty by creating funds specifc to that goal.

Since 2017, the proportion of Indigenous faculty and staf at the university has grown, partially because of the creation of new Indigenous positions. In 2016–2017, the vice president and provost dedicated a new fund to hiring faculty from groups underrepresented at U of T and, in 2017–2018, initiated a separate fund specifcally dedicated to hiring 20 new Indigenous faculty and 20 new Indigenous staf. The university also began a Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, which hires Black and Indigenous scholars and supports their research and career development.

The university should build additional avenues to support networking opportunities for Indigenous faculty and staf.

In 2019, the Ofce of the Vice-President, International facilitated a research partnership between U of T Indigenous scholars and scholars at the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, and the Melbourne Indigenous Transition School to create a plan that supports students to engage in Indigenous research in Australia and Canada. The Indigenous Research Network launched in 2021, forming connections between researchers, faculty, and staf focused on researching the challenges that Indigenous communities face.

Conduct exit interviews with any Indigenous faculty and staf who leave the university.

According to Simpson, all staf and faculty have the opportunity to participate in an exit interview. There is no formal system in place to interview all Indigenous faculty and staf who decide to leave.

Prize recipient Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s speech at Six Nations community near U of T, reminding the university community, “Don’t ever think it’s over.”

In an interview with The Varsity , Shannon Simpson, senior director of Indigenous initiatives at the Ofce of Indigenous Initiatives (OII), discussed the difculty of tracking progress on the TRSC’s calls to action. “[The calls to action] will be ongoing. They’re not things that we’ll probably ever be able to cross of the list,” she said.

The Varsity sought to document U of T’s progress on each of the 34 calls to action.

Review the anti-discrimination training materials supplied to hiring committees to ensure that they discuss specifc issues related to Indigenous peoples.

In 2020, the Ofce of the Vice-Provost, Faculty and Academic Life organized a workshop for leadership and faculty who participate in hiring, tenure, and promotion processes. The workshop aimed to provide leadership and faculty with guidelines for incorporating equity and inclusion into hiring decisions, as well as reducing the efects of bias. The OII encourages placing Indigenous faculty on hiring committees and ofers training sessions on Indigenous issues. According to Simpson, U of T does not require that members of hiring committees participate in any diversity and inclusion training sessions.

Assess the Indigenous cultural awareness training programs and begin discussions about how community members can promote equity and cultural sensitivity in relations to Indigenous peoples.

The OII piloted Indigenous Cultural Competency Training sessions in 2019. That same year, it hired John Croutch as Indigenous Training Coordinator, who took on the role of customizing training sessions for the university’s senior leadership.

Each division should consider creating an Indigenous leadership position within the Ofce of the Dean.

Multiple divisions have hired Indigenous advisors, mentors, and Elders in residence, some of whom are cross appointed with the Ofce of the Dean. These divisions include the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Victoria University, the Faculty of Architecture, the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, the Faculty of Law, and Woodsworth College.

Consider creating an Indigenous Advisory Council largely made up of Indigenous community members external to U of T.

The Council of Indigenous Initiatives Elders’ Circle, which is afliated with the university, existed prior to the TRSC’s 2017 report and comprises Elders who are not employed by the university. The Circle meets three times a year to review the university’s governance, strategic planning processes, academic and research programs, and relations to employees. Twice yearly, the Dalla Lana School of Public Health consults the WaakebinessBryce Institute for Indigenous Health National Aboriginal Community Advisory Council, made up of 22 Indigenous academic and community members from across Canada.

The provost and the vice-president, research and innovation should collaborate with the Faculty Association to convene a working group to investigate issues related to research in and with Indigenous communities, create guidelines for ethically producing this research, and determine how the university should assess this research for tenure and promotion.

In 2020, the Academic Advisor on Indigenous Research started the Ofce of the Vice-President, Research and Innovation Indigenous Research Circle to advise on community-focused research, programs, and policy. Additionally, members of the Indigenous Research Circle serve as staf on the Indigenous Research Network, which connects Indigenous scholars and promotes participatory Indigenous research.

Actively increase the number of Indigenous staf members who support important programs such as those aimed at strengthening Aboriginal languages and supporting Indigenous students. Over time, U of T should aim to fund these positions through core budgets instead of year-to-year add ons.

In 2016, U of T started the Diversity in Academic Hiring Fund, which funds positions targeted at Indigenous and Black faculty. According to the 2020 Report on Employment Equity, 1.1 per cent of staf self-identifed as Aboriginal, and the proportion of staf who identifed as Indigenous/Aboriginal and as racialized increased from the previous year.

Expand access to Elder services and fnancial supports for connecting with Elders.

U of T has introduced multiple initiatives to connect students and faculty with Elders. The Elder’s Circle meets with diferent divisions and members of the university community, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. New College has partnered with local Indigenous governments to create a program connecting students and Elders monthly. The Waakebiness-Bryce Institute for Indigenous Health holds monthly student/Elder talking circles, and Ontario Institute for Studies in Education hosts language events featuring Elders.

Examine the role and structure of the Elders Circle, particularly how the Circle’s mandate difers from the Council of Aboriginal Initiatives. U of T should also promote the importance of Elders across campus, particularly in advising senior leadership.

The 2019 report of the OII discusses the Elders’ Circle and the importance of Elders at U of T more broadly. According to the report, the OII encourages “the community to engage and grow in connection with them. The teachings and support of the University’s Elders are regularly called upon by divisions and academic units.”

Integrate signifcant Indigenous content into the curriculum of all divisions by 2025, and evaluate each division’s progress regularly.

In response to the Canadian government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, multiple faculties introduced initiatives to make Indigenous content mandatory, including the Faculty of Medicine, the Faculty of Law, and the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. Since 2017, many divisions have taken additional steps to incorporate Indigenous curricula. Some, including the Faculty of Arts and Science, have convened working groups to advise on Indigenous curricula. UTSC ofers grants for the development of Indigenous curricula and hosts an annual retreat for faculty to develop Indigenous curricula. In 2019, the Ofce of the Vice-President and Provost appointed Susan Hill, director of the Centre of Indigenous Studies and a citizen of the Haudenosaunee (Wolf Clan/ Mohawk Nation), as the Academic Advisor on Indigenous Curriculum and Education.

Develop opportunities for faculty, instructors, staf, and teaching assistants to learn about Indigenous issues. Create and fund a group, ideally made up of people of Indigenous heritage, to develop Indigenous curricula based in Indigenous knowledge and practices.

The OII ofers three training sessions that discuss Indigenous allyship, reconciliation, and land acknowledgement for both staf and students. In 2019 and 2020, more than 2,700 U of T community members attended these training sessions. U of T has hired education developers focused on Indigenous pedagogies.

Expand oferings in Aboriginal languages, starting from local languages and expanding to provide a broader range of languages. Provide consistent funding for teaching Aboriginal languages and the Indigenous Language Initiative

In 2017–2018, U of T provided courses on the Iroquoian language family and Anishinaabemowin. Currently, U of T’s Centre for Indigenous Studies (CIS) ofers courses on Anishinaabemowin, Kanien’kéha, and Inuktitut. The CIS also includes Ciimaan/Kahuwe’yá/ Quajaq, an Indigenous language initiative that facilitates language workshops, conferences, and activities for community members. The Varsity could not determine the levels of funding U of T dedicated to these courses and programs.

Develop research training modules that recognize the history of settlers conducting research unethically in Indigenous communities. Provide specifc cultural and research ethics training to any scholars who aim to work in or with an Indigenous community.

In 2019, The University of Toronto Libraries hosted lectures on Indigenous research methodologies, ethics, and ways to support Indigenous researchers. That same year, The Vice President and Provost’s Ofce appointed Suzanne Stewart, an associate professor in the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and member of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation, as the Academic Advisor on Indigenous Research. Her mandate includes advising faculty and students with interest in conducting research in Indigenous communities and developing best practices for conducting research that respects Indigenous peoples.

The Indigenous Research Network also provides services to support any faculty, staf, and students who are engaged in Indigenous research, including events, training, and individual meetings.

Create a subcommittee of the Research Ethics Board focused on Indigenous-related research and tasked with developing a way to coordinate with Indigenous communities when the board reviews research proposals.

At the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the VicePresident, Research and Innovation is in the process of establishing an Indigenous Research Ethics board that would include Indigenous faculty. This board will supplement the preexisting Decanal Advisory Committee on Indigenous Research, Teaching and Learning, which continues to advise the Faculty of Arts and Sciences on issues pertaining to Indigenous research.

Work with other universities to convene a committee discussing the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans and how it applies to research involving Indigenous peoples and communities.

In 2020–2021, Suzanne Stewart, Cathay Rournier, and the Indigenous Research Circle compiled a report consulting on Indigenous Research Ethics. Although this consultation did not include other universities, it suggested ways to adapt the Tri-Council Policy Statement based on a literature review and consultations with U of T and Indigenous community members.

Commission Indigenous authors to compile an accessible reference guide to Indigenous cultures and history, available to all U of T faculty, staf, and students through the internet.

The University of Toronto Library website includes multiple reference guides related to Indigenous peoples, including resources on the Indigenous history of Tkaronto, language resources, and Indigenous publishers and authors.

Consider creating a single, easily accessible Indigenous web portal where Indigenous students can access a variety of resources.

The Indigenous Gateway provides an overview of services, programs, and initiatives accessible to students across all three campuses.

Create a working group to investigate barriers for Indigenous students across undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs. Consider where the university might use admissions initiatives targeted at Indigenous people, particularly in graduate programs. Although the university convened an Indigenous Students Working group before the release of the TRSC report, The Varsity could not fnd evidence that it has convened one since. However, multiple graduate programs have implemented specifc pathways for Indigenous applicants, including the Faculty of Law and the MD program at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

Invest more to publicize and recruit to existing college pathway programs and targeted Indigenous access and bridging programs. These allow students who don’t meet admission requirements and who fnished high school more than two years ago to gain entry to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences while earning credit toward their degree.

The Indigenous Studies website and Indigenous Gateway include information about the Transitional Year Programme and Academic Bridging Program. Applicants can contact the Recruitment Ofcer at First Nations House to discuss options for admission. The Varsity could not determine the amount of money U of T has invested in advertising these programs over time.

Ask the working group recommended in call to action 25 to examine issues related to Indigenous student housing. The Varsity could not fnd evidence that the university created a working group to investigate access to student housing for Indigenous students.

Conduct a detailed study of how U of T might rework existing funding mechanisms to better support Indigenous students. Design a fundraising campaign where community members can donate to provide Indigenous students with scholarships and needs-based bursaries. U of T ofers multiple awards and bursaries aimed at Indigenous students, which can be found on the Indigenous Gateway website. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences allows individuals to donate specifcally to the Indigenous Students’ Scholarship Fund.

With the input of Indigenous students, staf, and faculty, design an education module, available to all, that introduces students to Indigenous cultures, histories, and the relationship between Indigenous peoples and U of T. U of T ofers education modules as part of the Indigenous cultural competency toolkit, including self-directed modules created in collaboration with Indigenous leaders.

Design a sustainable mentoring program that connects frst-year undergraduate Indigenous students with volunteer Indigenous faculty, staf, and students.

Some colleges and faculties, including Woodsworth College and Temerty, ofer Indigenous-specifc programs to connect incoming students with peers or faculty members. However, no U of T campus ofers a campuswide mentoring program specifc to Indigenous students.

Administration should discuss how the university will fundraise to meet the calls to action in the TRSC report and consider creating an overarching Indigenous Reconciliation fund.

The Defy Gravity campaign advertised specific donation funds to support Indigenous curriculum, spaces, scholarships, and research. However, the university has not created an overarching Indigenous Reconciliation fund.

Consider creating an Indigenous Advisory Council, composed of members of Indigenous communities who are outside U of T, which would monitor U of T’s progress on implementing the Calls to Action. Currently, the Ofce of Indigenous Initiatives, which does not include members external to the university, carries the responsibility of monitoring and driving U of T’s progress on the calls to action.

U of T should require all divisions to report to the provost each year, documenting the progress they’ve made in implementing the calls to action.

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences published an interim report in 2022 discussing the progress it has made toward the calls to action. The faculty also released similar reports in 2017 and 2021. However, The Varsity could not fnd evidence that other divisions reported their progress.

Every three years, a monitoring body should review the university and divisions’ progress on the calls to action. The role of monitoring U of T’s progress on the calls to action falls on the Ofce of Indigenous Initiatives, which publishes a report annually on the university’s progress. According to Simpson, the OII is currently working on creating a dashboard to track U of T’s progress on each recommendation.

With fles from Nawa Tahir.

sufered two wounds from self-defense on her hands.

In the Global News interview, the student said that she cannot currently return to her classes. She has also expressed that it’s unlikely she will ever use the TTC again.

The incident

The student explained to Global News that she doesn’t recall looking at her attacker. Instead, she had been focusing on another commuter who was crocheting. She only remembers Valdez moving toward her. The student attempted to fee, but fell, after which Valdez sat on her lap and began stabbing the student in the head with a folding knife.

The student then began screaming and calling for help until two men pulled Valdez of of her.

“I remember looking at myself in the TTC mirror, in the refection of the mirror, and I was bleeding, my entire face was blood,” she told Global News.

After the streetcar pulled up to the Sussex Avenue stop, a witness told the Toronto Star that the police were on the scene within two minutes. Offcers have since recovered a knife from the scene and highlighted that they would be evaluating the streetcar’s surveillance videos from the incident.

Content warning: This article discusses recent stabbings on the TTC and includes scenes of intense physical violence. It also contains a brief mention of sexual violence.

The January 24 TTC streetcar stabbing victim was a frst-year U of T architecture student, Global News has revealed.

Around 2:00 pm on Tuesday, a 23-year-old woman was attacked on a southbound 510 Spadina Avenue streetcar. The attack, which police do not believe was targeted, occurred just before the Sussex Avenue stop on the edge of the UTSG campus. The woman told Global News that she

believes she was stabbed approximately six or seven times in the head.

Police arrested Leah Valdez, the 43-year-old suspect, on the scene. Valdez is facing fve diferent criminal charges from the unprompted attack, including attempted murder, carrying a concealed weapon, possessing a weapon dangerous to public peace, aggravated assault, as well as the possession of a prohibited or restricted weapon with the knowledge that its possession is unauthorized.

Following the attack, the student — whose name Global News did not release for safety reasons — was rushed to St. Michael’s Hospital, where she says surgeons operated on her for an hour and a half. She stayed at the hospital overnight but has since been discharged. She has multiple staples and stitches on her head and also

Victim’s educational dreams put on pause

The victim explained to Global News that she moved from India to Prince Edward Island in 2018 before receiving her permanent residency in Canada, which allowed her to aford tuition. She has lived in the Greater Toronto Area since September 2022.

She told Global that she will eventually recover from her physical injuries, but she is traumatized and cannot leave her home. The student added that she is now afraid of people. Despite this, she still wishes to fnish her studies and “fnally have [her] dream come true.”

This attack against the U of T student follows the December 2022 death of 31-year-old Vanessa

Kurpiewska, who was a victim of a stabbing at High Park station. Police believe Kurpiewska’s attack was random, and that the attacker did not know her.

On Thursday afternoon, Toronto Police Chief Myron Demkiw, Mayor John Tory, and TTC CEO Rick Leary announced that the Toronto police would be increasing its presence across the TTC. This decision followed several other violent incidents in the last week, including one case of sexual assault at Kipling station, and a case in which an individual chased TTC employees with syringes near Dundas station.

While some commuters have welcomed the bolstered police presence, others believe the decision fails to address “root causes of violence,” including inadequate mental health-care services.

According to an article by the Toronto Star, the TTC reported over 450 diferent serious incidents against TTC users in the frst half of 2022. Some of the reports included robbery, assault, and harassment. Despite recent TTC customer levels sitting at 68 per cent of pre-COVID levels, if the attacks from early 2022 had continued throughout the year, the total number of reports would have averaged an increase of around 35 per cent from 2019.

Valdez was scheduled to appear in court on Wednesday, January 25, and will return to court on Monday.

If you or someone you know is in distress, you can reach out to:

• The U of T My Student Support Program available 24/7 at 1-844-451-9700 or 001416-380-6578 outside North America

• Good 2 Talk Student Helpline at 1-866925-5454

• Connex Ontario Mental Health Helpline at 1-866-531-2600

• Gerstein Centre Crisis Line at 416-9295200

• U of T Health & Wellness Centre at 416978-8030

Andrea Zhao

Design Editor

Andrea Zhao

Design Editor

On January 26, U of T’s Centre for Research and Innovation Support (CRIS) hosted an online seminar on decolonizing and Indigenizing research.

The event was chaired by Nicole Kaniki — Director of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) in Research and Innovation at U of T — who conversed with Sandi Wemigwase, a PhD candidate in Social Justice Education at U of T and the Indigenous Research Special Projects Ofcer at the Indigenous Research Network. Wemigwase is a citizen of Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in Harbor Springs, Michigan.

The event was part of the In Conversation With…Visiting Topics in EDI in Research & Innovation series organized by CRIS. Each seminar focuses on a diferent topic related to EDI in research and innovation.

The seminar began with a discussion on the possibilities for Indigenous research at U of T. Wemigwase spoke about the resources that the Indigenous Research Network ofers to researchers and students at varying stages of their careers, as well as the support available for Indigenous communities and nonprofts. The panellists then discussed practices that researchers should consider when working with Indigenous communities. Wemigwase highlighted the need for Indigenous involvement, collaboration, and consent in research,

and for recognizing the validity of Indigenous worldviews and perspectives.

Wemigwase also emphasized the importance of reciprocity in relationships between the researcher and the communities that they work with. She noted the importance of asking them, “what can I do for you that would help you?” and “how can this relationship be reciprocal?”

Wemigwase said that decolonization should involve Indigenous communities regaining autonomy of their traditional lands, but that many other steps could be taken along the way to achieving this goal.

One aspect of decolonization, according to Wemigwase, is the cultivation of Indigenous sovereignty. This would entail allowing Indigenous peoples “to have their own agency over what it is that happens to them,” explained Wemigwase.

Finally, the panellists discussed data collection practices. Wemigwase emphasized the importance of communication between researchers and the communities they work with during the data collection process. She also discussed how researchers should consult the people they work with when reporting on collected data.

Another important factor, said Wemigwase, is to consider the impacts of data and those who may be afected. She concluded, “Data isn’t necessarily just numbers, but there are actual… beings in the spirit behind that.”

The event concluded with a discussion on resources that the university ofers, which researchers can use to learn more about Indigenous research and working with Indigenous communities.

The next event hosted by the CRIS will take place on February 1, and will focus on adopting EDI principles into humanities and social sciences research.

Content warning: In addition to discussions of antisemitism, this article also mentions antiPalestinian violence.

On December 5, 2022, Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s (TFOM) Dr. Ayelet Kuper published a paper describing antisemitism she experienced during her year as the faculty’s senior advisor on antisemitism. Kuper is an associate professor and the associate director of Faculty Afairs at TFOM.

During her term as a senior advisor, which lasted from June 2021 to June 2022, Kuper heard colleagues perpetuate stereotypes about Jewish people, deny the existence of antisemitism, and refuse to accommodate Jewish students.

In response to Kuper’s paper and other recent instances of antisemitism, multiple groups highlighted the need to address antisemitism at the university and support Jewish students.

Kuper’s article

Kuper, who is a descendant of Holocaust survivors, documented numerous instances of antisemitism that she experienced at TFOM. Kuper was told “that Jews lie to control the university or the faculty or the world, to oppress or hurt others, and/or for other forms of gain,” referencing common stereotypes about Jewish people.

Others at the faculty told her that antisemitism can’t exist because everything that Jewish people say is a lie, “including any claims to have experienced discrimination.” Kuper also highlighted diferent student groups’ refusal to provide kosher food at events.

Some of the stereotypes Kuper documented pertained to the pandemic. Kuper wrote that she’d witnessed discussions blaming Jewish people for “concocting or causing” COVID-19 and perpetuating the belief that Jewish people mandated vaccines for their fnancial gain.

Kuper also heard dozens of times that TFOM’s “antisemitism problem” stemmed from the 2021 war in Gaza, blaming antisemitism on the Israeli government’s policy. Kuper overheard her colleagues complain about “those Jews who think their Holocaust means they know something about oppression.”

According to Kuper, some people associated with TFOM use the term ‘Zionism’ incorrectly and attempt to improperly redefne the term. Kuper defned Zionism as “the belief that Jews have the right to national self-determination,” adding that Israel “should be allowed to continue to exist as a country.” The term ‘antiZionism’ refers to the movement opposing Zionism and contesting Jewish people’s right to treat the State of Israel as their homeland.

Kuper’s article mentioned a January 2022 incident that she termed “the most well-publicized episode of antisemitism at TFOM this year.” Irwin Cotler, a former Canadian federal justice minister and attorney general, and professor emeritus of Law at McGill, presented a talk on antisemitism at TFOM for International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In response to the talk, 45 U of T faculty members sent a confdential letter to TFOM’s Acting Dean Patricia Houston. The letter criticized the event for favouring the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) defnition of antisemitism, which the university’s Antisemitism Working Group (AWG) had decided not to adopt a month prior.

The IHRA defnes antisemitism as “hatred toward Jews,” which is “directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.”

The confdential letter also stated that the talk reinforced anti-Palestinian racism by label-

ling “legitimate criticism of Israel as examples of antisemitism.”

Responding to the confdential letter, Doctors Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (DARA), a Toronto-based grassroots organization, released an open letter addressed to Houston, framing the confdential letter as antisemitic for its use of “well-worn anti-Jewish contrivances.” Over 300 Jewish faculty members at the university signed the DARA letter.

“There are, of course, those who speak up for Palestinians (for example) who do so without being antisemitic,” Kuper clarifed in her paper.

However, Kuper noted that, when other TFOM members insisted that Zionism implies “hating all Muslims” or “wanting to murder all Palestinians,” they cast Jewish Zionists through a skewed lens.

In October 2022, TFOM Dean Trevor Young apologized for the faculty’s restrictive quota system, which limited the numbers of Jewish MD students accepted to TFOM and physicians hired at partner hospitals for decades before and after World War II.

That same month, Hillel UofT, the centre for Jewish life at the university, received news that someone had drawn a swastika in front of the Munk School of Global Afairs & Public Policy.

In an Instagram post discussing the incident, Hillel UofT wrote that the defacement of a U of T building bearing the name of a preeminent Jewish donor was “emblematic of a larger problem at the University of Toronto.”

On January 9, 2023, the University of Toronto Students’ Union also published a statement highlighting the Munk School defacement, and expressing alarm about the rising rates of antisemitic instances at U of T and in Toronto.

At the latest Governing Council meeting on December 15, 2022, U of T President Meric Gertler highlighted the importance of addressing antisemitism and the work of the AWG, which U of T established in 2020.

The AWG submitted its report, which includes eight recommendations, in December 2021. Among those recommendations was that U of T ensure that kosher food is available on all campuses and actively apply the university’s Policy on Scheduling of Classes and Examinations and Other Accommodations for Religious Observations to avoid scheduling mandatory school events on signifcant Jewish holidays.

The AWG also recommended that “the University should frequently reiterate its commitment to academic freedom and inclusion.” The report called on the university to remind community members that the university won’t restrict events based on the presence of controversial content but that events must proceed in a “respectful, safe, and open manner.”

In his statement to the Governing Council, Gertler said that the university is committed to implementing all eight of the AWG’s recommendations and has “made signifcant progress.” Gertler also highlighted the steps TFOM has taken to acknowledge and combat antisemitism within the faculty. These measures include regularly consulting with Jewish learners — postdoctoral fellows and clinical residents — to support them, while also introducing curriculum changes and anti-racism training.

Miriam Borden, a member of the AWG and a PhD student in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, wrote in a statement to The Varsity, “When an [antisemitic] incident does occur, it reverberates throughout the entire Jewish community on our campus. The efect is chilling, alienating, and wounding.”

Borden wrote that, while the working group cau-

tions against curtailing academic freedom or free speech, the university should consider antisemitism as egregious as other forms of racist and religious discrimination.

On January 23, U of T held a restorative circle to provide a forum for community members to share their experiences with antisemitism. In an interview with The Varsity, Jacqueline Dressler — Hillel UofT’s Advocacy Manager and the event’s facilitator — explained that the university has often asked Hillel UofT to host such events because of its prominent role in the Jewish community on campus.

“We think it’s wonderful that the university comes to us and asks us to help support them… to make sure the Jewish experience is refected in the university’s culture,” said Dressler. “We should always be talking about antisemitism and how it afects Jewish students all the time, all year round,” she added.

In regard to Kuper’s claim that student associations did not provide kosher food at TFOM events, Amit Rozenblum — senior director and senior Jewish educator at Hillel UofT — explained that Hillel UofT ofers fve-dollar kosher meals for students fve days a week.

He explained that Hillel UofT typically outsources kosher catering and ofers recommendations for groups seeking to provide kosher food at their events.

Dressler commended Kuper for highlighting the types of antisemetic incidents that have “become really common on university campuses.”

“All members of the U of T community really should be outraged with the things that Dr. Kuper is describing,” Dressler said.

Kuper did not respond to The Varsity’s request for comment.

Content warning: This article discusses antisemitic violence, including mentions of concentration camps and genocide.

During the week starting January 22, U of T hosted various events to discuss historic and current antisemitism, leading up to International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Friday, January 27.

The events took place amid recent conversations about antisemitism prompted by allegations of hate speech at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine and U of T’s rejection of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) defnition of antisemitism.

This year’s International Holocaust Remembrance Day marked the 78th anniversary of Soviet troops liberating the Nazi death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, where more than one million people were murdered.

Restorative Circle

On January 23, U of T’s Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity Ofce hosted a Restorative Circle for the Jewish community via Zoom. According to the event description, the event was intended to “share the impact and harm of antisemitism on us and our community — as well as repairing and refecting together.”

Jacqueline Dressler, the manager of advocacy at Hillel UofT and the event facilitator, asked participants to refect on matters ranging from “an intention that will support you on your journey of healing,” to “Jewish joy, or [feelings of] resilience.”

Participants responded to this activity through the chat function, because verbal communication was not available to participants. Some discussed studying the Torah, connecting with distant relatives, and “solidarity across diferences.”

The university originally set up the event in re-

sponse to antisemitism concerns at U of T. “I can’t comment on how the university was promoting it, because we’re not employees of the university,” Dressler told The Varsity in an interview. She said she initially “didn’t get the impression that it had to do with Holocaust education week.”

Survivor testimony

The following day, Hillel UofT, Jewish Addiction Community Services (JACS), and Friends of Simon Wiesenthal co-hosted a International Trauma and Survivor Testimony event at the Wolfond Centre on 36 Harbord Street.

The event included a presentation by Jenna

Quint — JACS’ Courage 2 Change program coordinator — on the sociological and medical manifestations of intergenerational trauma, down to its genetic impacts.

She discussed the four main adaptational styles of families of Holocaust victims. These include “victim families,” aficted with pervasive depression; prideful “fghter families” who lack the ability to trust; “numb families,” with intolerance for positive or negative stimulation; and the successful, “we made it” families, whose children may feel neglected in the pursuit of goals.

During the event, Gershon Willinger, a Holocaust survivor, gave a presentation on his child-

hood. During World War II, many parents hid “unknown” or “hidden” children in attics or cellars, or even sent them to Christian families or certain religious institutions to hide them from the Nazi regime. Willinger became one of these “unknown children” after his parents were killed in the Sobibor death camp in Poland in 1943.

Sima Shmuylovich, an undergraduate student majoring in computer science at UTSG, who attended the presentation, told The Varsity, “I’m obviously happy that U of T is trying to do more events… but I think it’s typically only people from the Jewish community who show up. Getting the larger community to come is defnitely the goal.”

Book Panel Discussion

On Thursday, the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies hosted historian Harold Troper in a panel discussion about his 1983 co-authored book, None is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948. The book is widely credited for exposing Canada’s unwillingness to accept Holocaust refugees.

Allison Kinahan, a graduate student in the history department, told The Varsity, “The focus on the Canadian aspect is interesting, but I think in conversations there should be an element where we discuss our own colonial past.” She added, “But, from what I’ve heard about the Holocaust events that are being held this week, I think that is being covered as well.”

In an interview with The Varsity, Troper said, “It’s not false modesty for me to say that I’m as surprised as anybody by the success of the book, by the way it has shaped discussion and debate.” He continued, “That the book still speaks to people today about the Canadian scene today and about issues of refugees and immigration speaks to the power of the written word.”

With fles from Lexey Burns.

January marks Tamil Heritage Month, and, on January 25, the UTSC International Student Centre, St. George Centre for International Experience, and UTM International Education Centre collaboratively hosted a panel discussion featuring three Tamil members of the U of T community.

The panellists discussed connecting to their Tamil heritage, navigating misinformation about their identity, and cultivating a sense of community at U of T.

Stories

The Tamil people are an ethnic group primarily made up of Tamil-language speakers in southern India, Sri Lanka, and throughout South Asia. Many Tamil people practice Hinduism, although the community also includes Jains, Christians, and Muslims.

Panellists Ninthusha Uthayakumaran, Jananee Savuntharanathan, and Pirakasini Chandrasegar were all born and raised in Canada. Their parents left Sri Lanka as a consequence of the Tamil genocide during the Sri Lankan Civil War, which lasted from 1983–2009.

Although some Tamils arrived in Sri Lanka before 500 BC, the British forcibly brought other Tamils to Sri Lanka to work tea plantations in indentured servitude, starting roughly 200 years ago. Following independence, the new Sri Lankan state denied many Tamils’ political rights, excluding them from the Sri Lankan

Parliament, and they continued to experience generational poverty.

Confict escalated to regular attacks and battles between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a militant independence movement aiming to create a separate Tamil state, and the Buddhist Sinhalese people, who are the major ethnic group in the country. In 2009, the Buddhist Sinhalese people defeated the LTTE. Throughout the 26 years of confict, a total of approximately 80,000 deaths occurred, 350,000 people were displaced, and one million people became refugees.

All three panellists expressed that being Tamil is deeply intertwined with their lineage. Savuntharanathan, a UTM graduate student, explained that their shared history of trauma enables them to build a community together.

Chandrasegar, a fourth-year UTSC student, added, “What it means to be Tamil is holding that whole lineage, holding all of that ancestral pain, and hopefully educating the rest of the world about what it means [to be Tamil].”

Uthayakumaran, a recruitment and admissions ofcer at Rotman’s School of Management, recounted her difculty in resonating with her Tamil identity at many points in her life. “Did it mean that I spoke the language, I can cook the food, I take part in the fne arts?” she asked. “Is that what being Tamil means?”

It wasn’t until she entered her graduate program that she began to further explore her identity and history. Now, she describes being Tamil not only as “very internal” and “very personal,” but also as “being resilient.”

Being a Tamil student at the U of T also comes with its challenges. All of the speakers emphasized “miscommunication and misinformation” from others as one of the biggest barriers they’ve faced.

“Especially when I’m talking in diferent spaces,” Chandrasegar said. “People don’t necessarily understand, especially those who aren’t educated about the subject [of Tamil culture].” She encouraged students to further educate themselves on Tamil history by taking the time to fnd new resources or even asking more questions to avoid making comments that may downgrade a person’s lived experiences.

Savuntharanathan added that people tend to assume she’s from a specifc place of origin. She explained that Tamil is a language and Tamil people come from around the world, not just one place.

As a child, Savuntharanathan would often struggle with the stereotype of Tamil people having “ties to terrorism,” as well. She shared, “To this day, sometimes I feel like I’m a threat to society and I don’t know why.”

For Savuntharanathan, a lot of the miscommunication she faced came from the news and political discourses. She added, “It’s so important to understand the history that we come from, to truly understand us as a person.”

Uthayakumaran noted that when she was a student in her undergraduate and graduate programs, she “didn’t know where to go to fnd other students” that were like her or that would understand her.

For all the panellists, being able to share their culture and personal life experiences with others enhanced their time at U of T. Chandrasegar recounted that there was a lack of Tamil representation during her frst few years at UTSC. This resulted in her founding the Tamil Student Union, which provided her with a new community and safe space.

Before concluding the event, the panellists offered advice for U of T students and the university administration as a whole.

Uthayakumaran encouraged more diversity on campus. She emphasized the importance of bringing in diverse course materials that are not “fully Eurocentric” to provide diferent perspectives in the classroom.

“One thing I would even tell my younger self is to not think that you’re not Tamil enough,” Savuntharanathan said. Regardless of birthplace, she explained, “We all just bring such a uniqueness, just from our own lived experiences.”

All three speakers expressed that fnding a community to interact with can make university a much more positive experience. “There is definitely one community you belong in. Look for that community — and if you can’t fnd it, make that community,” said Uthayakumaran. “Community starts with you.”

This event was part of the university’s Our Stories series, wherein students and staf from diferent communities are invited to share their personal stories in commemoration of various awareness months celebrated across each campus.

experiences with identity, representationJanuary 27 marked International Holocaust Remembrance Day. MAEVE ELLIS/THEVARSITY

On January 25, Mariana Valverde — a professor emeritus with U of T’s Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies — and Brian Gettler — an associate professor at UTM’s Department of Historical Studies — presented their research on the material history of U of T’s lands at a public lecture held at the Canadiana Gallery.

Their research found that the university acquired almost 226,000 acres of land from the Crown in 1827, which they sold for almost $43 million in today’s currency. In addition, U of T’s eforts to develop the lands allocated to UTM sparked disputes between the university and local homeowners.

Valverde and Gettler’s research is part of a nationwide efort to investigate how settlers used dispossessed, stolen, and unceded Indigenous lands to fnance the development of universities in Canada.

Their lecture is part of the CrimSL Speaker Series, hosted by U of T’s Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies. According to the centre’s website, the speaker series aims to expose students to topics, research methodologies, and theoretical perspectives in criminology and sociolegal studies.

U of T’s original endowment lands

Valverde’s research focuses on U of T’s original endowment lands and how much U of T profted from the sale of these lands. Endowment capital refers to money or property given to U of T, which U of T typically invests to generate income.

Valverde explained that the governments of most settler-colonies such as Canada were “cash poor but land rich,” meaning that they did not have enough money to directly fnance educational institutions but possessed an abundance of land. “Of course,” Valverde said, “these lands were taken from Indigenous peoples.”

Valverde found that, in 1828, the government gave King’s College — the precursor to U of T — almost 226,000 acres of land that the Crown had seized. It repeatedly instructed U of T to sell these lands — particularly to settler farmers — as a way to generate revenue and fund the university.

These lands did not come in one piece, Valverde found. At the lecture, she presented historic maps showing that U of T’s original endowment included land in the townships of York, Monaghan, and Haldimand, among others.

However, Valverde said that U of T’s current endowment lands are not likely from the original endowment package. By 1861, U of T had already sold the majority of these original lands, generating almost $1.4 million – amounting to almost $43 million in today’s currency.

Valverde cited a 1906 report from the Royal Commission on the University of Toronto, which stated that, “throughout North America little in the fnancial history of universities has been more noticeable than the good efect of large grants of wild land.” As such, the commissioners recommended that the government give U of T a total of at least one million acres of land.

While Valverde could not determine whether

this additional endowment ever took place, she wanted to illustrate “the sense of entitlement” settlers felt toward Indigenous lands.

Gettler’s research explored UTM’s founding during the postwar boom of university-building. He found that, in the 1960s, U of T’s board of governors passed a bylaw granting them the ability to expropriate or seize property. U of T tried to expropriate homeowners near UTM’s lands in order to develop the UTM campus. However, on June 28, 1965, U of T cancelled its expropriation plans due to pushback from local homeowners.

Gettler also found that the U of T committee in charge of planning the satellite campuses had conficts of interest. For instance, the committee included land and property developers who U of T later hired to develop newly bought lands for the satellite campuses.

In an interview with The Varsity , Gettler noted the “tightly knit connections between forproft corporations and the university” that he found in his research. He also explained that the news at the time often reported on the disputes over UTM’s development. “Yet, we don’t know about them [now],” Valverde said.

A nationwide research efort

Valverde told The Varsity that their work is part of a nationwide research project that aims to create a public history website documenting how Indigenous dispossession funded Canadian universities. According to Valverde, the project started “very informally,” right before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. She began working with two other professors based in Vancouver and estimates that the efort now includes around 12 to 15 researchers from institutions including the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, University of Victoria, and Saint Mary’s University.

Currently, the research team is preparing to apply for a grant so they can create the website. Valverde said that the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg already agreed to host the website.

Along a similar vein, historian Robert Lee and journalist Tristan Ahtone conducted the US Land-Grab Universities investigation. They examined how the US funded 52 universities with nearly 11 million acres of dispossessed Indigenous lands.

Beyond the website, Valverde said, “It’s up to Indigenous students, faculty, and nations that have been afected by the land grab to think about… what they might need or want.”

On January 27, the University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU) Board of Directors (BOD) met to approve levy fee increases and the 2022–2023 Operating Budget.

Wenhan (Berry) Lou, vice-president internal, presented a motion to dedicate $10,000 toward urgently replacing a broken fridge at the Blind Duck. The fridge lasted 15 years, and a new replacement is projected to last another 15 years.

Levy fee increases

Felipe Nagata, the UTMSU executive director, presented 2023–2024 levy fee increases for the upcoming year. Nagata confrmed that fees will increase but services remain the same. “All fees are pretty much increased by [Canada’s consumer price index (CPI)] with the exception of the U-Pass.” The CPI represents changes in consumer prices due to infation.

The UTMSU Food Centre levy fee, which is the only fnancial contribution to the food centre budget except for donations, will increase from $0.64 to $0.68 per session. This levy fee afords the operation and stafng of the food bank, while the Mississauga Food Bank supplies the food for the centre. A session is equivalent to one semester.

The Academic Society levy fee which goes toward the operation of 17 clubs and societies at the UTM campus will increase from $1.19 to $1.26 per session. The UTMSU Student Society fee will increase from $37.51 to $39.72 per session for full-time students and $1.22 to

$1.29 per session for part-time students, as per the CPI.

The UTM chapter of the World University Service of Canada Program levy fee afords the sponsorship of a refugee student’s full tuition as well as social and academic support to aid their transition to Canada. This levy fee will increase from $2.08 to $2.20 per session for full-time students, and from $1.28 to $1.36 per session for part-time students.

The Canadian Federation of Students funds the implementation of on-campus grassroots campaigns such as Consent is Mandatory, United for Equity, We The Students, and Reproductive Justice. This levy fee will increase from $8.86 to $9.42 per session.

All increases were approved.

The U-Pass and health and dental plan

For the upcoming academic 2023–2024 year, the Mississauga Transit U Pass will be changing from a physical pass to a digital pass; students will be able to tap their phone onto the Presto card readers. The UTMSU will pilot the digital U-Pass program in the summer semester. As the U-Pass will be digital, there is no longer a replacement fee if a student loses their physical copy.

The student cost for the Fall/Winter 2023–2024 Mississauga Transit U-Pass will increase from $144.74 to $157.77 per session, while the Summer 2023 U-Pass will remain $192.29. “The summer fee remained the same… because the summer students currently pay more for the pass than the fall/winter students,” Nagata said. He added that the increased cost of the Summer U-Pass was due to decreased rid-

ership in the summertime.

The UTMSU student society fee designated for the Green Shield student insurance Accidental Health Plan will be increasing from $102.09 to $112.30. The Dental Plan will increase from $83.34 to $93.87. All student levy fee increases were approved unanimously, and subject to implementation in the upcoming 2023–2024 year.

Lou presented both the Blind Duck and the UTMSU’s Operating Budgets from the 2022–2023 year. The Blind Duck, the on-campus pub and restaurant run by the UTMSU, noted a $3,000 increase in both rental income — from renting space to Chatime, a bubble tea location in the Student Centre — and an increase in Alcohol Labour Income because it is the only place on campus that sells alcohol.

Lou highlighted that the Blind Duck saw a $2,000 decrease in ticket sales and an increase in rentals of CO2, china, and linens — up $1,000 from its Preliminary Budget of $3,000. The report also indicated that there was also a $10,000 increase in salary expenses. Overall, the Blind Duck lost $18,800.

Because of the unexpected decreases in sponsorships for orientation events, the UTMSU saw a $171,169 increase in expenses for Frosh Week from the forecasted $35,000. The union experienced a $49,000 defcit in the Major Events budget category.

Also forecasted in the budget is a reading week trip to Montréal, which is budgeted at

$36,000. The UTMSU hopes to raise $33,400 in students’ ticket sales, resulting in a $2,600 net expense for the union.

The upcoming budget forecasts increased funds allotted to the InfoBooth for the purchase of tickets. This service facilitates access to discounted vouchers to Wonderland, Boston Pizza, bowling, escape rooms, and Cineplex Movies.

The budget indicates a $26,000 increase in Executive Stipends after the BOD voted to increase executive salaries in September 2022.