Vol. CXLV, No. 19

21 Sussex Avenue, Suite 306 Toronto, ON M5S 1J6 (416) 946-7600

thevarsity.ca thevarsitynewspaper @TheVarsity thevarsitypublications the.varsity The Varsity

Eleanor Yuneun Park editor@thevarsity.ca

Editor-in-Chief

Kaisa Kasekamp creative@thevarsity.ca

Creative Director

Kyla Cassandra Cortez managingexternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, External

Ajeetha Vithiyananthan managinginternal@thevarsity.ca

Managing Editor, Internal

Maeve Ellis online@thevarsity.ca

Managing Online Editor

Ozair Anwar Chaudhry copy@thevarsity.ca

Senior Copy Editor

Isabella Reny deputysce@thevarsity.ca

Deputy Senior Copy Editor

Selia Sanchez news@thevarsity.ca

News Editor

James Bullanoff deputynews@thevarsity.ca

Deputy News Editor

Olga Fedossenko assistantnews@thevarsity.ca

Assistant News Editor

Charmaine Yu opinion@thevarsity.ca

Opinion Editor

Rubin Beshi biz@thevarsity.ca

Business & Labour Editor

Sophie Esther Ramsey features@thevarsity.ca

Features Editor

Divine Angubua arts@thevarsity.ca

Arts & Culture Editor

Medha Surajpal science@thevarsity.ca

Science Editor

Jake Takeuchi sports@thevarsity.ca

Sports Editor

Nicolas Albornoz design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Aksaamai Ormonbekova design@thevarsity.ca

Design Editor

Zeynep Poyanli photos@thevarsity.ca

Photo Editor

Vicky Huang illustration@thevarsity.ca

Illustration Editor

Genevieve Sugrue, Milena Pappalardo video@thevarsity.ca

Video Editors

Emily Shen emilyshen@thevarsity.ca

Front End Web Developer

Andrew Hong andrewh@thevarsity.ca

Back End Web Developer

Razia Saleh utm@thevarsity.ca

UTM Bureau Chief

Urooba Shaikh utsc@thevarsity.ca

UTSC Bureau Chief

Matthew Molinaro grad@thevarsity.ca

Graduate Bureau Chief

Vacant publiceditor@thevarsity.ca

Public Editor

Associate Senior Copy Editors

Asmi Khanna, Damola Omole, Sharon Chan

Associate News Editors

Avin De, Shontia Sanders

Associate Opinion Editors

Caitlin Adams, Ameer N. Vidal

Associate Features Editors

Sofia Moniz, Chris Zdravko

Associate A&C Editors

Mashiyat Ahmed, Ridhi Balani

Associate Science Editors

Mariana Dominguez Rodriguez

Social Media Manager

:

Cover Rania Phillips

Associate Sports Editors

Medha Barath, Aunkita Roy Associate B&L Editors Loise Yaneza, Brennan Karunaratne

Associate Design Editors

Jaylin Kim, Chloe Weston, Simona Agostino

Associate Illo Editors

Jason Wang, Kate Wang

Associate Photo Editors

Nidhil Vohra, Jennifer Song

Associate Video Editors

Yan Luk, Sataphon Obra

Associate Web Developers

BUSINESS OFFICE

Ishir Wadhwa business@thevarsity.ca

Business Manager

Rania Sadik raniasadik@thevarsity.ca

Business Associate

Eva Tsai, Muzna Arif advertising@thevarsity.ca

Advertising Executives

The Varsity acknowledges that our office is built on the traditional territory of several First Nations, including the Huron-Wendat, the Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit. Journalists have historically harmed Indigenous communities by overlooking their stories, contributing to stereotypes, and telling their stories without their input. Therefore, we make this acknowledgement as a starting point for our responsibility to tell those stories more accurately, critically, and in accordance with the wishes of Indigenous Peoples.

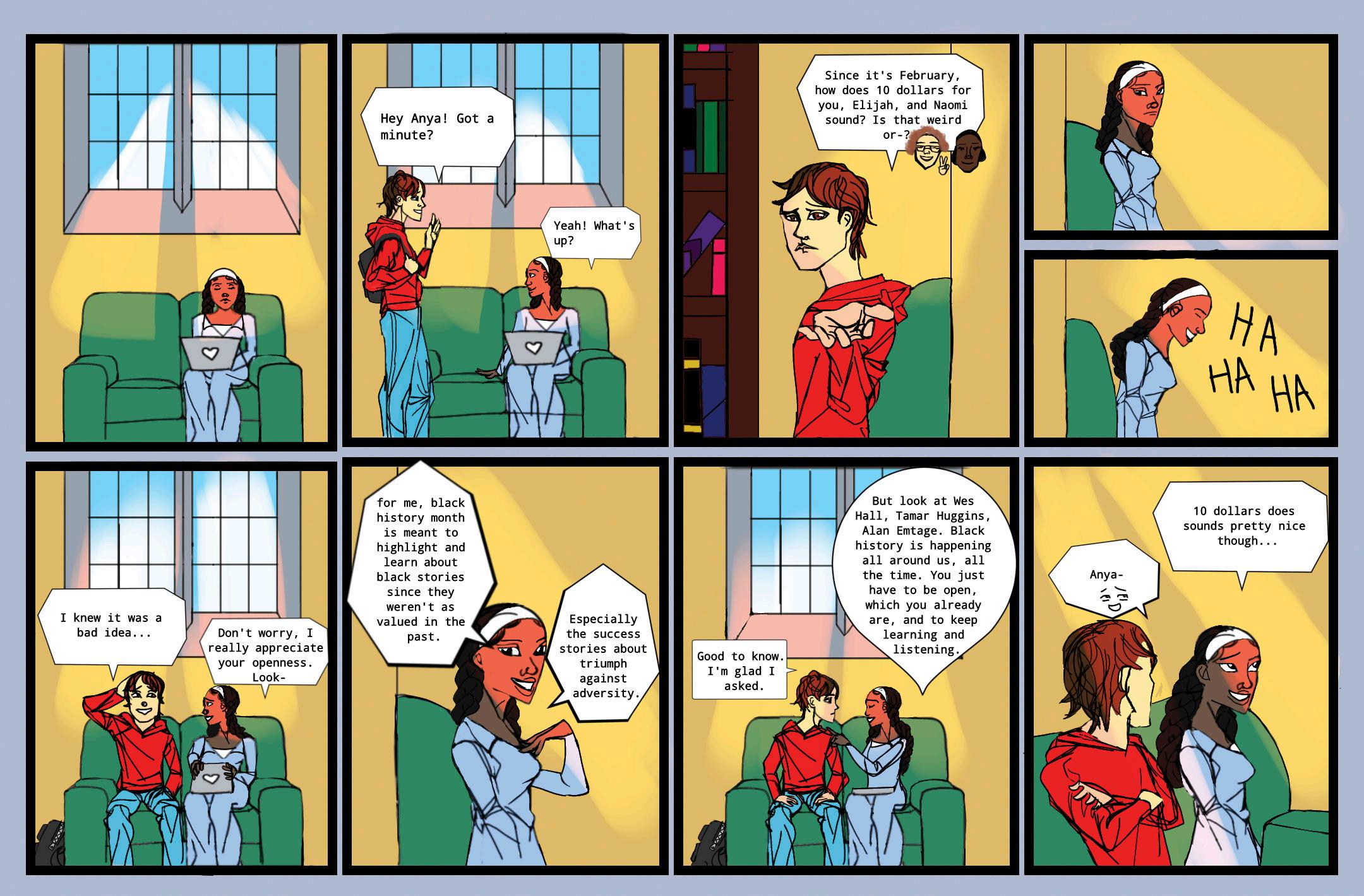

Rania Phillips Varsity Contributor

This year, my message is shaped by the theme of moving forward while looking back. In my past work, I explored the significance of Black art from a personal standpoint — my journey to gain a greater appreciation of my family’s features and how that growth reflects the larger society’s broader push toward progress. However, as I grow older and become more

politically engaged, I better understand the incremental nature of collective justice and the individual costs that come with its ebb and flow. It’s hard not to feel discouraged by the news, but inaction is not an option. In this piece, I aim to convey what I believe are the essential pillars of social progress: the courage to confront oneself and recognize one’s role in Black history, the need to grapple with both internal and external barriers to meaningful change, and the resilience to keep moving forward.

In hopes of taking a collaborative step toward equitable coverage

Eleanor Yuneun Park Editor-in-Chief

In March 2020, The Varsity ’s Public Editor published an article titled “Black History Month demands respectful reporting.” As the position requires, then-Public Editor Osobe Waberi held our paper in check by reflecting on the Editor-in-Chief and Managing Editor’s process of putting together the issue and — importantly — recording a list of dos and don’ts for journalists at The Varsity and beyond.

Not only did the items on Waberi’s list inform our reporting since they were first published, but our consultations with the Black Students’ Association (BSA) also largely shaped our editorial decisions in creating our initial Black History Month (BHM) issues.

The Varsity has only begun publishing an annual BHM issue not so long ago in 2019.

What began as a suggestion from a couple of masthead members’ evolved into a yearly issue featuring a cover illustrated by a Black artist on campus — an idea also suggested by the BSA — and full of articles that highlight diverse Black student experiences both on campus and beyond.

Unlike the process that birthed our BHM issue, our recent processes have been significantly less collaborative. The previous

Hello there!

volume acknowledged this in the 2024 BHM issue’s Letter from the Editor, and I regret that our current volume did not approach our BHM issue so differently.

As of fall 2024, Black students made up 5.57 per cent of U of T’s three campuses, while other racialized groups like East Asian students comprised 33.94 per cent and white students made up 24.73 per cent. Although the people who compose The Varsity ’s Masthead are not the same as Waberi’s colleagues at the time — none of whom were Black-identifying — Black students are still a minority at our paper, whether it be among our Masthead or contributors.

Given this, our BHM issues in recent years have begun through our school-wide emails to reach all full-time students across three campuses. While we’ve received an incredible number of emails this year from students looking to write, draw, and edit for this issue, we know that this is only the first step. Our responsibility is to ensure that the students stay with us with the knowledge that our paper is a place worth returning to.

Marking the sixth anniversary of our first BHM issue, we want to return to why the first issue was possible in the first place: collaboration and consultation. The Varsity ’s BHM issue exists not to mark the pinnacle of discourse but to revisit and evaluate our commitment

to incorporate Black writers, illustrators, photographers, and stories regularly into our weekly coverage, so that a BHM issue does not vary much from our other weekly issues. But has our coverage reflected the ultimate end goal of our BHM issue?

No.

And we want to do better — not just through a single letter like this but through a constructive feedback and application system. We’ve sent out a survey to the BSAs across our three campuses, the African Students Association at UTM and UTSC, and numerous other Black student groups, which asks for an evaluation of The Varsity ’s coverage of Black students and communities in the past years. This feedback will help us inform our future editorial and visual decisions in representing Black communities.

We’re also extending this form to you — our readers that we serve — for your feedback. In the form, you’ll also have the option to choose to meet with me and our Managing Editor, Internal, Ajeetha, should you wish for further discussions. The form will be open until March 10, and at the end of this volume, we will share with you a summary of your responses and our established commitments for the volumes to come.

This is still the beginning. And we want to take the next step forward with you.

The Varsity, U of T's student newspaper, would like to invite you to give feedback on our coverage thus far on Black students, community, and identity at U of T in our issues as well as our Black History Month-themed issues.

Your feedback will help us inform our editorial and visual decisions in accurately and appropriately representing the Black community's diversity, events, perspectives, and issues. All questions in the survey are optional, so please read through and answer however many (or little) questions as you'd like! The more detailed feedback, however, the more tailored our coverage can be toward Black-identifying individuals.

U of T’s Black Students’ Association held the event at new lounge for Black students

Damola Omole Associate News Editor

On February 5, U of T’s Black Students’ Association (BSA) hosted a barbershop event at the newly created Black Student Lounge. Approximately 16 individuals attended the event on the third floor of the 21 Sussex Clubhouse.

The event aimed to create a “safe, judge-free space where self-identifying Black men can come together and openly discuss what matters most to [their] community.” Attendees were also able to receive free haircuts from barbers at the event.

Chopping it up

The event started off with a presentation by BSA members: Equity Officer Favour Adegboro, a second-year life sciences student and VicePresident (VP) Internal Mesai James, a third-year neuroscience and immunology student. They asked the attendees: “What does it mean to be pro-Black?”

After a moment of reflection, attendees began discussing the nuances of being passionate about one’s identity, while still celebrating and embracing the beauty in diversity and multiculturalism.

The rest of the questions posed throughout the presentation were in the same vein. The group considered the challenges associated with navigating one’s Black identity in various environments, including at U of T.

Elijah Gyansa — a fourth-year student studying health studies and global health — was one of the more outspoken participants. After the discussion, he shared his reasoning for attending the event with The Varsity

“I feel like I can feel seen and heard. I [can] get a haircut to make me feel more confident but also… have discussions with other Black students about how they’re doing in school and just relate to them,” said Gyansa. “I just wanted to come out to meet other Black students, Black [men], and build community and bonds.”

Black Barbershop

Beyond the presentation and discussion, a key part of the event was of course, the haircuts.

Students who attended had the opportunity to receive a free haircut, similar to other initiatives on campus, such as the university’s Hart House Black Futures Barbershop — which offers specialized monthly services for students with Afro-textured hair.

Barbershops are significant locational fixtures in Black communities, drawing on decades of history and cultural significance.

Since the 19th century, barbershops have served as places for Black people to not only receive hair care services but also be vulnerable and talk about issues of importance in their communities. For Black communities, hair once existed simply as a tool of oppression at the hands of colonizers, but now serves as a symbol of pride and self-expression for many.

The Varsity has previously reported on how Black students’ hair and culture intersect with

U of T professors and students discuss the impacts of housing discrimination

Olga Fedossenko

Assistant News Editor

On February 7, U of T’s Department of History and the School of Cities held “A Symposium on the Histories and Geographies of Housing Discrimination” as part of a series of events celebrating Black History Month.

The symposium, organized for the second consecutive year by Department of History PhD candidate Catherine Grant-Wata, included several presentations focusing on anti-Black housing discrimination in Canada. Grant-Wata has been researching the topic of racial discrimination in housing since receiving her master’s degree where she wrote her thesis on the history of housing discrimination in Toronto from 1961–1977.

The event featured keynote speaker Joe Darden — a professor emeritus from Michigan State University — whose research expertise is in residential segregation, social inequalities, and immigration.

Housing discrimination in the US and Canada

The event began with Grant-Wata’s welcoming speech, where she shared insights about racial discrimination in Canada’s housing sector.

“Canada has what I’d call its own unique brand of maple-sugar-coated anti-Black sentiment and racism,” argued Grant-Wata. She said that even though racism in Canada is “disguised by a sickeningly sweet veneer of politeness,” it is “no less dehumanizing or demoralizing” for Black Canadians. This is apparent with housing discrimination.

Grant-Wata then introduced Darden, who discussed the causes of racial discrimination in housing in the US.

He began his presentation by emphasizing that white supremacy ideology is what causes racial residential segregation in neighbourhoods today, as those who hold that ideology want to keep Blacks, Hispanics, and Asian communities “separate and unequal… to satisfy white supremacy.”

Darden mentioned the US’ Fair Housing Act, saying that “[housing discrimination] continues because there’s a lack of enforcement of the Fair Housing Act of 1968.” The act “prohibits discrimination by direct providers of housing… to persons because of: race or color, religion, sex, national origin, familial status, or disability.”

“Many whites in the US do not want to have [the

act] enforced because they don’t want to have to get [an] integrated neighbourhood,” explained Darden. “White supremacy [is to] maintain and protect white dominance by maintaining neighbourhoods.”

According to 2021 research from the University of California, Berkeley, 81 per cent of metropolitan regions in the US were more segregated in 2019 than they were in 1990.

Following Darden’s speech, U of T Department of Sociology Associate Professor Prentiss Dantzler discussed the housing situation in Canada, which “[seems] very similar to the US context, but [gets] co-opted or diverse in very different ways.”

In an interview with The Varsity, he explained that Canadians “have this complicated country, given that we have a high immigration policy… so [the issue of housing challenges] gets conceptualized or… described as an immigrant thing when it’s not particularly just an immigrant story.”

A 2023 report by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) showed that both immigrant and non-immigrant racialized groups can be in core housing need, meaning their houses can fall below at least one of the adequacy, affordability, or suitability standards. From 2011 to 2016, the percentage of racialized immigrants in core housing needs was 27 per cent, which was only slightly higher than that of racialized nonimmigrants at 24 per cent.

CMHC’s report also found that while an immigrant status is less strongly linked to persistent housing difficulties, being a racialized person increases the possibility of experiencing core housing needs. This pattern is seen in housing discrimination as well, where the renters’ racial identities increase barriers.

A 2022 study by the Canadian Centre for Housing Rights found that newcomers in Canada experienced more discrimination when they revealed their racial background to the landlord. Additionally, the study found that undercover phone audits revealed that newcomer auditors who are men experienced a 267 per cent increase in discrimination when they had racialized accents while speaking to landlords on the phone. Newcomer auditors who are women saw a 62 per cent increase in discrimination when they had a racialized accent.

Dantzler finished his presentation at the symposium by informing the audience about his latest project, the U of T Housing Justice Lab: a

the challenging representation barriers that Black members of the U of T community face. Nathan DeGuire — a third-year student studying architectural studies in the technology specialist stream — shared his thoughts on the significance of the Black barbershop as a whole.

He wrote in an email to The Varsity that the barbershop is a rare place in the mainstream that’s built by Black people, for Black people.

“There’s no judgment; you’re surrounded by people who want to build you up and leave you looking the best you can be,” he explained. “It’s the type of place where you don’t feel the need to explain your existence in, but instead, a place where you’re actively wanted.”

The Varsity also later sat down with James. He spoke about his desire for Black men on campus to become more comfortable bonding and forming tighter-knit relationships, believing that events like this help make that vision a reality.

In celebration of Black History Month, James emphasized education and personal initiative in a message to U of T community members.

“Support Black-owned communities or organizations, whether that be a small bracelet-making organization or even just a cafe down the street who’s owned by Black individuals,” he said. “Educate yourself… learn about Black Canadian history.”

research initiative on improving housing justice in North America.

The lab’s work focuses on the “Racial Equity and Anti-Displacement Initiative;” the “Ensuring Quality Urban Affordable Living Initiative;” and the “Fostering Reparative Equity for Empowered Living Initiative.” These initiatives aim to help reduce the effects of eviction on racialized communities in the GTA and support the development of housing across North America.

Dantzler’s team has conducted research into the eviction rates among racialized communities in Toronto, which showed that neighbourhoods with a higher concentration of Black households had the highest odds of experiencing eviction compared to other racialized neighbourhoods. During his presentation, Dantzler said that he’s been in communication with racialized communities in Toronto to find out more about the displacement rates.

Other student and professor attendees spoke on a variety of topics related to racialized housing discrimination, such as forced evictions in Rio de Janeiro ahead of the 2016 Olympics, slum clearance in India, and anti-Black rental housing discrimination in Toronto.

Some of the attendees spoke to The Varsity about their impressions of the event and the speeches.

Titobi Oriola — a first-year student from Nigeria studying international relations — came to the event to give a speech about “stories near and dear” to him, involving communities in Lagos facing forced evictions.

During his interview with The Varsity, he spoke about his move from a “third-world country” to Canada, and how that changed his perspective on housing discrimination.

“Moving to Toronto, experiencing and seeing

housing discrimination in a different form, in a place that I thought was so much better, it sort of brought my attention to the fact that that is a very real issue… in the present day and age,” said Oriola. “Housing discrimination is something anyone can face.”

A U of T alumnus, Anyika Mark, had similar sentiments. She came to share the story of her community in the ‘Little Jamaica’ neighbourhood in Toronto, and the Black communities’ gentrification: a practice where wealthier residents move to a poor area of the city, renovate homes and businesses, causing property values to rise, which displaces the original, usually poorer, residents.

“Little Jamaica… has been such a huge part of my childhood and my adolescent experience,” said Mark. “...To know that it can be so easily dismissed as not relevant or not important by our city, by our province, especially our province — the fact that they’re willing to watch that fade away — is not okay with me.”

Others attended the event out of interest in the topic.

James Glaser — a fourth-year student studying sociology — said he came because of a class he took a year before that sparked his interest in housing and its effects on his generation.

“I think housing is something that’s going to affect our generation the most because we’re the ones who are going to bear the consequences of all these barriers that are coming up,” he said.

Glaser added, “We’re going to be the ones who aren’t able to afford it, and because the system that we’ve lived in for so long is based on owning a home as your ticket to financial security and financial freedom… we either need to find a way to fix the system and go back to the way it was, or fix the system in a way where… we don’t see housing as a ticket to financial freedom, but more as a human right.”

Council members, Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow discuss Johnston’s role in the community

Rafael Garcia Rosas Varsity Contributor

On January 31, Professor Linda Johnston was formally appointed as the 12th Principal of the UTSC campus at the Sam Ibrahim Building. This followed the departure of the previous UTSC President, Wisdom Tettey, who stepped down in April.

Johnston, a renowned nursing researcher, was also recognized as U of T’s new vice-president.

The Vice-President and Principal are responsible for administrative decisions including the budget, appointments, promotions, and managing the UTSC campus.

Johnston has served as the acting vice-president and principal since January 1, 2024. On June 27, 2024, the Governing Council officially approved her appointment.

Before taking on this role, Johnston spent over nine years as the dean of the Lawrence Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at UTSG. Prior to joining U of T, she led Queen’s University Belfast School of Nursing in the UK and held nursing practitioner roles in hospitals in the US, Australia, and the Middle East.

The ceremony Many university officials, faculty, staff, students, and Toronto politicians attended the event.

The event began with Indigenous Knowledge Keeper Naulaq LeDrew sharing a short prayer,

followed by U of T’s Vice-President & Provost Trevor Young delivering a land acknowledgement.

U of T President Meric Gertler made remarks on Johnston’s ability to “[excel] in all aspects of her career,” and praised her “openness and authentic leadership style.”

Johnston was officially granted her role through U of T’s traditional “robing ceremony,” during which she received her new principal gown.

Scarborough—Rouge Park MP Gary Anandasangaree and Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow delivered speeches on how Johnston will play a critical role in advancing UTSC’s community partnerships and its impacts on the region.

Chow shared that “the city counts itself lucky that a researcher and leader known around the world for improving nursing education and patient care” stepped into the role “at a critical time.”

U of T’s Governing Council Chair Anna Kennedy, Vice-Principal Academic & Dean Karin Ruhlandt, and Chief Administrative Officer Andrew Arifuzzaman also spoke at the event.

Kennedy noted that “Professor Johnston is ideally suited to assume this important leadership role.”

“She is a distinguished scholar whose leadership is inspired by and built upon a career rich in experience from her work in teaching, research, and university administration, and she has a deep understanding of the challenges

and opportunities that exist in higher education today,” she added.

The Scarborough Campus Students’ Union President, Hunain Sindhu, was also present at the ceremony and participated in the robing tradition.

Hussain Syed is a fourth-year student studying human biology and psychology and a student representative for U of T’s Health and Wellness Centre, appointed by Johnston. Syed spoke at the event about how Johnston’s background as a healthcare professional would have “given her a deep appreciation for how fostering [a] culture of care is key to helping students reach their fullest potential.”

Concluding remarks

The ceremony concluded with Johnston delivering her installation address.

In her speech, she described the position as the highlight of her career, emphasizing that

her main goal was to create a “culture of care” during her five-year term.

In an interview with The Varsity after the ceremony, Johnston explained her vision for a campus community where people “feel valued, that they can speak up, and they’re heard, and that they feel like they’re included in decisions.”

Johnston also highlighted her commitment to advancing UTSC’s role in “optimizing the social, environmental and economic well-being of Scarborough and the eastern GTA.”

She mentioned that the Scarborough Academy of Medicine and Integrated Health, scheduled to open in 2026, will play a crucial role in providing health services, research, and further educational opportunities for the region.

“I will do my best to justify [UTSC’s] trust by continuing to focus on our core values of intentional inclusion, students as partners, reciprocity and accountable stewardship,” she concluded.

Looking at U of T’s efforts to address anti-Black racism, increase

Eshnika Singh Varsity Contributor

Over the past few years, U of T has made strides in advancing Black representation in academia and combating anti-Black racism through a number of initiatives from the Black Research Network to the Scarborough Charter on AntiBlack racism and Black inclusion in Canadian Higher Education.

The Varsity took a closer look at some of the initiatives the university offers to support its Black community members.

Anti-Black racism and Black inclusion in academia

In 2020, former UTSC Principal and U of T VicePresident Wisdom Tettey chaired a meeting with representatives from universities across Canada to address anti-Black racism on their campuses and discuss measures to enhance inclusion. As a result, nearly 50 post-secondary institutions signed the Scarborough Charter on Anti-Black Racism and Black Inclusion in Canadian Higher Education.

The report recounts the history of racism against Black individuals and outlines the Charter’s four main principles: Black flourishing, inclusive excellence, mutuality, and accountability.

The Charter includes a variety of action steps, such as reassessing existing campus security and safety infrastructure, conducting surveys to better understand the needs of Black students and faculty, providing financial aid to support research opportunities in Black Canadian studies programs, adopting improved educational policies, and paving the way for more Black students to access higher education.

However, The Varsity wasn’t able to confirm UTSC’s progress on resolving the charter’s recommendations.

The Black Research Network

The Charter led to the establishment of the Black Research Network (BRN) in October 2021. This was done alongside the efforts of U of T’s

Anti-Black Racism Task Force — which was in action during the 2020–2021 academic year and reviewed the university’s practices to address anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion at U of T.

The BRN is one of U of T’s Institutional Strategic Initiatives, which aims to “launch, grow, and sustain large-scale interdisciplinary strategic research networks.” The network is led by Enid Montague, an associate professor in the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering, who oversees a core team and steering committee, consisting of seven U of T community members.

The network aims to increase visibility for the research accomplishments of Black U of T scholars, sustain a network of Black scholars, and facilitate research engagements across the university and internationally.

On its website, community members can navigate the “Researcher Map” to search for Black scholars across U of T, with expertise in distinct fields.

The BRN’s mission aligns with the recommendations of the Anti-Black Racism Task Force and the Charter. It’s also Canada’s first research initiative aimed at prioritizing Black academic research access.

It provides funding, mentorship, and academic platforms for Black researchers, ensuring their voices and work are prominent across disciplines.

Since its inception, BRN members have been awarded Canada Research Chair positions by the Government of Canada, initiated the Empowering Black Academics, Researchers and Knowledge creators program to elevate Black voices in research on childhood disabilities, and created the Black Graduate Scholar Award in Geography & Planning to award Black students research in the field.

The BRN is set to host the BRN Research Symposium on April 14, where researchers from various fields across the three campuses will present their multidisciplinary research in STEM, social sciences, and the humanities.

Reducing barriers to graduate school

In 2017, U of T launched the Black Student Application Program (BSAP) to increase diversity within the Faculty of Medicine.

The program aims to address the underrepresentation of Black students in medical education and the healthcare field by providing a dedicated application stream for Black applicants.

In 2016, only one Black student was enrolled in the U of T Temerty Faculty of Medicine’s MD program. Since the launch of BSAP, the Faculty of Medicine has seen an increase in Black students, with 14 students admitted in 2018 and 15 in 2019.

In response to the program’s success, U of T later expanded the BSAP to include students aspiring to enter the Faculty of

Law or the Master of Social Work program. Announced as part of the university’s broader efforts to promote equity and inclusion, BSAP allows applicants to self-identify as Black and have their applications reviewed by a panel that includes Black faculty members and community representatives.

In 2021, a group of masters of business administration (MBA) students at the U of T Rotman School of Management recognized a lack of representation in their classes and urged the university to reduce the barriers to higher education. In response, U of T established the Black Leadership Scholarship — first known as the Morning and Evening MBA Black Students Advancement Scholarship. This scholarship aims to help cover the high financial costs associated with pursuing an MBA at U of T.

In her interview, Melani Vevecka — a thirdyear student studying political science and evolutionary anthropology — discussed her previous leadership experience that would assist her as president. Vevecka worked as an executive assistant for the Prevention, Empowerment, Advocacy, Response, for Survivors (PEARS) Project and as an evolutionary stream representative for the Anthropology Students’ Association.

The main focus of her campaign is on improving communication — both enhancing the flow of information from the UTSU to the student body as well as providing clubs, organizations, and individual students with more access to the union.

She plans to have bi-weekly office hours with students and learn more about the issues that they want the union to address. Vevecka also wants the student body to become more aware of the student programs offered by the union. “I think one thing that I want to improve is having more visibility [and] recognition for people to take advantage of

on include creating a comprehensive system for students to get involved in clubs, establishing a TTC subsidy program for commuter students, and introducing a retroactive Credit/No Credit (CR/ NCR) option.

Her aim with the last program is to allow students to explore various options with their degree before committing to a specific program of study. “I do think that people grow up. They find new passions, and they [discover] new interests — what you did in first-year doesn’t necessarily serve you in your fourth- [year].”

Paul Gweon is a third-year student studying political science and philosophy. He is currently the president of the Woodsworth College Students’ Association (WCSA) and the chair of the UTSU Senate’s Governance Committee. In his interview, he explained that the latter experience familiarized him with the union’s policies.

Gweon’s campaign focuses on holding the UTSU and its executives accountable.

“Campaign promises sometimes are not met when [executives are] elected,” he explained. “My job as president [would be to] make sure everybody’s promises are kept [and] help them accomplish these promises.”

In addition, he emphasized the importance of balancing long-term goals with short-term gains.

Noting the failed 2017–2018 UTSU referendum to increase student fees to fund a U-Pass and the continued lack of a U-Pass at UTSG, Gweon explained that a short-term approach, such as partially reimbursing TTC passes like the WCSA, would benefit students more immediately.

problem we have… We have to approach [it] in another way.”

When asked about what aspects of the UTSU he’d like to improve, Gweon emphasized a need for more transparency, pointing out that students had mixed reactions to the current union’s Annual General Meeting and were confused about where expenses were allocated.

Additionally, he feels the UTSU needs more engaging events. “Student engagement can be step number one for better governance,” he said.

Leli Gardapkhadze is finishing her third-year of studying criminology and sociolegal studies and history, and European affairs — in addition to completing a certificate in international affairs.

Gardapkhadze said her work as a project manager at the Youth M-Powerment Global Network — a non-profit organization dedicated to empowering youth through scholarships, fellowships, and internships — has helped prepare her for this position.

Gardapkhadze’s platform has three goals: student empowerment, advocacy, and expanding opportunities. She wants students to “have a say in the policies” at U of T. If elected, Gardapkhadze will advocate for mandatory academic advisory checkins for students and an improved course enrolment system.

Additionally, she wants to “push for creating new opportunities like grants and scholarships that could aid students in terms of finances” and “intro duce a TTC fare specifically for U of T students.”

Throughout this academic year, UTSU’s current VP PUA Avreet Jagdev, has been advocating for a similar initiative — the TTC free pass program that would cover students’ TTC tickets for a 15-to-20week duration.

Finally, Gardapkhadze plans to create more scholarship opportunities for students by leveraging her connections with representatives of the municipal, provincial, and federal governments that

Damola Dina is in her third-year, studying political science, critical studies in equity and solidarity, as well as women and gender studies. Dina is currently the president of the Black Students’ Association and a former executive member of U of T Students for Choice.

In her interview Dina emphasized that, “You can’t thrive as a student [if] your basic needs aren’t met.” Noting that U of T is a commuter school, Dina outlined her plans as VP PUA to lower meal plan costs, work toward a free transit system for students, and follow through on establishing new student residences.

Further, Dina plans to amend the current CR/ NCR system. Since “the university understands that there is a need for a pass-fail system,” she

hopes to continue these efforts as VP PUA, while also improving the union’s transparency. She plans to revisit policies — including anti-

“It’s your union, your voice, and your power,” said Sonak Saha — a first-year student who plans to study philosophy and political science — as his campaign slogan. Saha told The Varsity that he decided to run for VP PUA when he attended the UTSU’s annual general meeting in October as a member of U of T Student Strike for Palestine (SS4P).

During the AGM, a member of SS4P asked if the UTSU would support the international university strike for Palestine in November 2024. Saha said the UTSU allegedly never responded to SS4P about the strike, and he felt that student concerns were being dismissed.

“I want students to actually feel like UTSU is not just some random organization that they follow on Instagram… but something that they can interact with, and they know and feel they have a say in,” Saha explained.

decentralize the UTSU’s decision-making and introduce more referendums on contentious issues, as well as hold mandatory town halls before decisions are made.

Saha has experience as a Warrant Officer for his Air Cadets squadron, where he was in charge of 60 cadets, and as a House Representative on the Woodsworth Residence Council, where he represents his house and helps with events.

Saffiya Ramhendar-Armogan — a third-year political science and criminology student — hopes to improve “the youth experience for students and build more of a community.”

At U of T, she has been a mentor for stu dents at Woodsworth College and is currently part of the Vice Provost, Students Advisory Group.

Ramhendar-Armogan’s campaign focuses on advocacy and transparency. She wants to create more opportunities for student feed back such as “a feedback website” or town halls where students can speak to the union about issues affecting them.

She also wants to improve academic policies, such as implementing clearer guidelines around artificial intelligence use; reducing wait times for accessibility services and mental health services; and improving transit access through a university pass.

program wouldn’t likely happen in the 2024–2025 academic year.

“I feel like it’s really important for students to have a say in the administration of the university, and sometimes it feels like we’re not necessarily being considered,” she told The Varsity “I want to run for this role [because] I feel like students need to have their voice heard.”

After serving as an executive member of the UTSU for three consecutive years, Elizabeth Shechtman is “eager to continue building on [her] successes” as she runs for re-election.

A fourth-year economics and bioethics student, Shechtman was the union’s 2024–2025 VP Finance and Operations, 2023–2024 President, and 2022–2023 VP Student Life.

Among her achievements over the past three years, Shechtman mentioned the launch of MyUTSU — a platform for student groups to manage activities, book spaces, and secure funding. She also mentioned how she increased awareness about Empower Me — a program that offers students in-person mental health services.

Shechtman’s campaign focuses include building a café at the Student Commons, where “student employment is very much happening.”

She also hopes to fill all 50 seats on the UTSU’s Student Senate — the union’s governance organ

five days a week for students, instead of only on Fridays, so students can “just come in [and] pick up things as they go, without having to sign up for anything.”

Shechtman added that throughout her time as the VP Finance and Operations, the union has kept their levy increases minimal. However, she stated that the union — and herself, if re-elected — hope to raise the orientation levy “to host bigger events.”

Yağmur Yenilmez is a third-year student studying economics and computer science while pursuing a certificate in business fundamentals.

In her interview, she mentioned she “was always really into finance,” and served as UC Lit’s Finance Commissioner during the 2023–2024 academic year. Additionally, she is the youth representative for the United Nations and the vice-president of the Turkish Student Association.

Yenilmez’s campaign focuses on transparency, as she wants to ensure that students know how the union uses their student levy. She plans to use her skills in computer science to build an artificial intelligence website that would ensure easy access to the UTSU’s financial information. The UTSU currently has a website where they upload budget documents, but it has not been updated since August 2024. She also mentioned that the platform would reduce the UTSU’s operational

Winston Zhao — a second-year management specialist focusing on marketing and economics — said his experience as a community resource specialist at the UTSU Community Hub help desk motivated him to run.

“I know which services are used more and which are more important to the students,” he explained in his interview. “[As VP], I want to be on the back side of things and have more of a general understanding of the finances.”

Zhao emphasized that his campaign’s overall theme is transparency and has “three pillars”: communication, allocation of budget, and accountability.

Whether it’s transparency in informing students about what the executives are working on or what promised project they were unable to accomplish, Zhao reiterated that

“something I want to push is accountability in what the executives do.”

Zhao recalled when the UTSU announced its changes to students’ mental health coverage, and how he wants to be more transparent in internal communication: “I didn’t find out about it until the day the students found out about it… I couldn’t provide the support that I was

Hala Marouf is a third-year student studying philosophy and English. She is currently the executive assistant to the UTSU’s VP E. Motivated by the ability to “allocate resources where they’re most needed,” her platform is focused on advocating for individual students while strengthening grassroots, student-led equity organizations.

Marouf identifies food insecurity, safety, genderbased violence, and accessibility as key campus issues.

Hunar Miglani, a second-year student studying political science, economics, and statistics, told The Varsity that her combined experiences as a student with disabilities and an international student have motivated her to run for the position.

“I see people talking about why [they weren’t] able to partake in a certain event [or] attend a certain networking [event]… People are voicing these concerns, but nobody is hearing them or even willing to give them an opportunity to express their grievances.”

She plans to support student initiatives like Regenesis Market and Food Coalition and expand the food bank. She would also like to develop the rideshare program for safer and cheaper student transportation; enhance UTSU’s partnership with Downtown Legal Services; and provide additional support after students exhaust institutional resources like the Anti-Racism and Cultural Diversity Office or Accessibility Services.

Her campaign revolves around making UTSU’s social events more accessible and visible.

Miglani hopes to spread more awareness of resources for students with disabilities, such as the mental health coverage students pay in

Inclusion experiences to being the VP Funds of the UTSG chapter of Enactus, a global entrepreneurship group, and an Assistant Program Director and admissions officer for LaunchX — a summer program for high school students interested in entrepreneurship.

As a neurodivergent, queer, and racialized person, fourth-year bachelor of information student Sammy Onikoyi has “an intimate perspective on how equity, or the lack thereof, disappoints so many.”

“I have a connection to communities that occupy [several different identities] and [I] want to be a voice for them,” said Onikoyi in an interview The Varsity.

Throughout her time at U of T, Onikoyi has recognized institutional shortcomings in supporting students with disabilities and mental health struggles. As a student with ADHD, she hopes to collaborate with Accessibility Services to advocate for disorder-specific accommodations and move away from the “cookie-cutter” approach the office currently takes.

wishes to advocate for accessibility — such as extensions on assignments — and institutional supports — like solidarity statements.

Lastly, she emphasized outreach as a priority, noting students’ lack of awareness of available services within the UTSU. “I want to make that clear — you are entitled to this… you deserve this,

Onikoyi also criticized U of T’s needs-based grant, arguing that bursaries should be an ongoing initiative rather than awarded per semester.

As a Nigerian student, she recognizes the importance of fostering strong community

student groups to address their specific concerns.

Thanks to her work as a vice-president of the Nigerian Students Association and her efforts fundraising for the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the New Democratic Party, Onikoyi said she has experience making decisions that directly “influence on something that would impact a real person’s life, whether it be school, or whether it be the funding.”

Aliyah Kashkari is a third-year student studying work and organizations, drama, and political science. Feeling underrepresented as an Arab student at U of T, Kashkari decided to run for the UTSU’s VP SL to “make sure that every student [… feels] represented” and “their ideals are valued.”

This year, Kashkari has served on the UTSU’s Student Senate, which gave her “insight within the student government and decision making.” She is also a director of social events for her sorority, Delta Delta Delta.

Kashkari said that the number one goal of her campaign is to increase student visibility by “reactivating the VP SL Instagram and expanding clubs fairs to its fullest potential to help students discover and connect with the clubs.”

they need to thrive.”

Finally, Kashkari wants to foster a “stronger sense of community within the campus” through “encouraging more collaboration between clubs

Juan Diego Areiza is a fourth-year student studying global health, critical equity studies, and immunology.

Areiza has worked as a community resource specialist at the UTSU for the past two years and currently serves as president of the Organization of Latin American Students. In his interview, he said that these roles have equipped him with front-facing skills and an equity lens.

His campaign focuses on two central goals: improving student representation and increasing the UTSU’s recognition among students.

Nehir Arpat is a second-year student studying psychology and cognitive science in the computational cognitive stream. After reflecting on her experiences as a first-year international student — feeling isolated and unsure how to become a part of the student community — she is motivated to run for VP SL to build a sense of community and home among students.

In her interview, Arpat said she wishes to help students beyond their academics and with their personal growth. She noted that most UTSG students are not a part of or regularly attending clubs, despite it being a major part of student life. Thus, she intends to help promote clubs on campus. In addition, she wishes to bargain for student discounts at stores near campus to help ease the cost of living.

Arpat also plans to engage students by being more active on the union’s Instagram account, such as through doing Q&As, as well as holding more events for first- and second-year students after Orientation Week, as she feels that “not a lot of people know how important the union is and how much power of change [it] holds.”

For the first, Areiza plans to organize one large-scale student life initiative per semester aside from orientation, including a “culture fest” where people from minority groups on campus can showcase their heritage. Areiza explained that the UTSU must collaborate “with student groups to highlight their culture [and] identities

Having served as UTSU’s VP PF for the past academic year, Erica Nguyen is running for reelection because she believes “there’s a lot of work that needs to be continued.”

“I’ve learned a lot more about the other faculties besides my own, and it’s been really interesting to hear about the different issues and problems that we come across,” said Nguyen, a fourth-year student studying design and visual communications. “I feel like we really need to tackle them moving forward.”

Sneha Bansal, a second-year student studying ethics, society and law, and human geography, was inspired to run in the election after seeing the union’s current VP SL, Tala Mehdi, in action during Orientation Week, where Bansal also contributed as an orientation coordinator for Woodsworth College.

Bansal is also an administrative director on the Woodsworth Residence Council and VP of Sponsorship on U of T’s Trek for Teens: a non-profit organization that raises funds and awareness for youth experiencing homelessness in Canada.

Nguyen’s campaign this year focuses on advocacy and communication. If reelected, she plans to streamline “communication between students and administration” as she believes professional faculty-student voices are “unheard on campus,” and “not the number one focus.”

She hopes to hold regular meetings with professional faculty members to connect with

financial aid survey she created during her current term. She said she’s been collecting data on the “hidden costs that [specific] professional faculty students have,” such as art supplies for architecture students and lab materials for nursing and medical students.

Nguyen hopes to use her survey findings to “push for further financial aid.”

Bansal’s platform focuses on raising awareness about UTSU’s resources for clubs and attracting a wider range of clubs. She also seeks to cater the events hosted by the UTSU to UTSG’s diverse student community.

Vivian Nguyen, a third-year architecture student at the Daniels faculty, is passionate about advocating for students in professional faculties because she feels they are often overlooked.

Reflecting on her own experiences, she remembers struggling to find clear information about how Daniels differed from the Faculty of Arts & Science when she started at U of T. She wants to improve access to resources and ensure students understand what benefits the UTSU fees provide.

As a former Orientation Week leader, Nguyen has firsthand experience helping first-years transition into life at university. Her campaign focuses on two key goals: addressing professional faculty-specific concerns and fostering cross-faculty connections. She hopes to improve course enrolment, ensuring that required courses are prioritized for students in their respective programs. “I find that certain required courses aren’t being put as a priority or aren’t being blocked off for at least the first few days for students in the program to register into them.”

enrolment into certain courses depending on their program and year of study.

Nguyen also wants to “provide more opportunities for students to connect with other peers outside of their faculties.”

“I feel like it’s important for students to interact with different ideas and people beyond their program or faculty,” she added.

Vice-President,

U

February 25, 2025

thevarsity.ca/category/business biz@thevarsity.ca

Rubin Beshi Business & Labour Editor

CUPE 3902, among other unions representing workers at U of T, is pursuing damages in court against the Ontario government to secure retroactive pay increases following the repeal of Bill 124.

Bill 124, which capped public sector employee wage increases at one per cent annually starting in June 2019, was deemed unconstitutional by the Ontario Court of Appeal and repealed in February 2024. Since then, the Ontario government has renegotiated union contracts and paid over six billion dollars in retroactive wage increases to affected workers. However, most of these payments have gone to unions with reopener clauses in their contracts — clauses that allow parties to renegotiate specific terms due to a change in circumstance.

None of U of T’s contracts with unions contain reopener clauses — hence why these unions have taken the Ontario government to court.

The Varsity examined the Ontario government’s response and the unions’ efforts to negotiate compensation in the wake of Bill 124’s repeal.

Ontario government’s retroactive pay increases

By fall 2024, the Ontario government had largely distributed settlement packages to unions with reopener clauses in their contracts, such as the Ontario Nurses Association, AMAPCEO, Ontario’s union for government professionals, and Canadian general trade union Unifor.

However, the process of providing retroactive pay for unions without reopener clauses has proven more difficult. In these instances, unions have been encouraged by the government to request renegotiations with their employers, who then need to seek approval from Ontario’s

Treasury Board — which is responsible for reviewing all government spending and approving labour contracts — before any back pay agreement can be reached.

In an interview with Global News over the summer, CUPE Ontario President Fred Hahn stated that many workers have found this renegotiation process confusing and frustrating. Hahn further claimed that some employers have

Bill 124 moderation period.

Jennifer Harmer, a PhD candidate at the Centre of Industrial Relations and Human Resources, believes that the university is “taking a wait and see approach” to whether the Ontario government will ultimately mandate the university to pay retroactive wage increases before taking any further action.

In an email to The Varsity, Harmer explained

“None of U of T’s contracts with unions contain reopener clauses — hence why these unions have taken the Ontario government to court.” ” “

told CUPE members that they simply don’t have the money to renegotiate.

U of T’s labour contracts

A report to the Business Board about the university’s recent collective agreements noted that the absence of reopener clauses means it has “minimal responsibility” for the financial damages caused by Bill 124. As a result, the university has resisted “significant union pressure” to provide retroactive pay to cover losses workers sustained during the three-year

that all public universities in the province are funded and directed through government legislation through the Ministry of Colleges and Universities. Additionally, the Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development supervises labour relations between unions and universities, in particular.

“This could influence the university employers[’] ability to negotiate with unions,” she wrote.

For example, the government may constrain the ability of publicly funded universities to generate revenue and place heavy pressure on

them to cut costs. “Unfortunately, the cost of labour is a frequent target,” Harmer wrote.

The Business Board report noted that the absence of reopener clauses in their union contracts, coupled with high inflation, meant that “the University spent significantly less on labour costs relative to inflation for the 6 years that include the Bill 124 moderation period, as compared to previous years, since at least 2005.”

Since union contracts with the university don’t include reopener clauses, unions have now been forced to seek alternative ways to recover lost wages — in this case, through the courts.

In an email to The Varsity, CUPE 3902 President Eriks Bredovskis wrote that CUPE 3902 — which represents U of T’s sessional lecturers, postdoctoral researchers, and teaching assistants — has been pursuing remedies through the court system alongside its “sibling CUPE Locals and other public sector unions.”

“Our union leaders are leading the charge in the courts, and, to the best of our knowledge, we are waiting for dates for the hearing,” Bredovskis wrote.

When asked how the university is responding to legal action being pursued by unions, a U of T spokesperson wrote to The Varsity that “questions regarding legal action by unions in relation to the Ontario government are for those unions to address.”

Harmer noted that Bill 124 has “really constrained [U of T] management’s ability to negotiate with workers” and finds it “unfortunate that [the bill has] created so much confusion and backtracking in the collective bargaining process.”

When asked whether the university administration has set aside funds in the case a court orders them to provide retroactive pay increases, the university’s spokesperson declined to comment.

February 25, 2025

thevarsity.ca/cateogory/opinion

opinion@thevarsity.ca

We need to talk about Blaccents at U of T Is ‘vocal blackface’ a thing on campus?

Nicole De Jesus Varsity Contributor

A few weeks ago, I was absentmindedly sitting in a tutorial when I heard my white TA attempt to imitate ‘jive talk’. Hearing him say “yo wassup” to imitate a Black American seemingly unprompted, quickly jolted me and my class back to reality.

Jive is a form of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) which developed during the 1930s within the flourishing African American jazz scene. It’s a beautiful collection of jargon and dialects spoken by Black people as a form of cultural expression.

In spite of this, AAVE is often viewed as simply ‘improper’ English and is even a cause of discrimination. Jive as a way of speaking has a vivid history, but it was difficult to connect its origins when my visibly non-Black TA boiled it down to phrases like “yo” and “my brothas.” The room was so silent you could hear a pin drop. I was rendered speechless.

As one of the only Black students in the room, I felt like my race was presented to a room of primarily non-Black students as a racist caricature. I felt offended; this happened in an African American history course of all places. Thankfully, the TA was swiftly replaced after that tutorial, but I noticed non-Black students on campus throughout that week who used AAVE phrases like “It’s not giving” and “I’m not tryna do that,” delivered with the flair of an American inner-city kid — definitely not the quiet Canadian suburbs they are from. I began to wonder what exactly the difference was between the racist jive of my TA and the ‘funny’ AAVE appropriated by my nonBlack peers on campus. Eventually, it occurred to me that these patterns of speech are two

sides of the same coin; at their core, they are both mechanisms to ridicule Black culture, separated only by their varying degrees of subtlety.

“

When non-Black people use blaccents by imitating AAVE in an African American accent, they typically only adapt it when they’re attempting to be funny. I find this to be quite dehumanising, and a parallel to how blackface was used in comedic settings.

”

The past and present of Blackface

In recent years, new material has emerged on the evolving form of blackface in the modern world. “Blackface” emerged in the 19th century as a minstrel performance where white actors painted their faces black to mock

African Americans. While many view blackface as an issue of the past, scholars argue that it is actually still prevalent in society — only in different forms.

American feminist writer Lauren Michele Jackson popularized the term “digital blackface” to describe the “practice of white and non-Black people making anonymous claims to a Black identity through contemporary technological mediums.” When GIFs that non-Black people use online to express their feelings are of Black celebrities, or when they represent themselves online through an emoji of a Black person, they are practicing digital blackface.

This form of blackface can be harmful since it appropriates aspects of the Black identity — such as facial expressions and jargon — and presents it as entertaining instead of a sincere form of expression. Non-Black people turn AAVE expressions into cursory jokes, which then lose their original definitions and are eventually discarded. Popular memes depict dramatic facial expressions from Black people that perpetuate stereotypes of Black people as being hyperactive and foolish. Ultimately, this dehumanizes Black people by depicting the way we speak and express ourselves — and even the way we look — as a form of comedy.

I believe the appropriation of Black expressions and language is epitomized in the appropriation of ‘blaccents,’ which is when non-Black people imitate AAVE while speaking. When non-Black people use blaccents by imitating AAVE in an African American accent, they typically only adopt it when they’re attempting to be funny. I find this to be quite dehumanizing, and a parallel to how blackface was used in comedic settings.

While I can’t necessarily say that people’s accents should correlate to their race, I think there is room for critiquing switching accents

for comedic purposes — especially when it’s a non-Black person adapting the ‘funny’ accent that references African American culture.

Speaking in stereotypes

In my own personal experience, I found that there are students at U of T who shift into a blaccent around me solely for the reason that I am Black. Although I’m from Toronto and speak in a generic Canadian accent, I find that sometimes non-Black students approach me by using AAVE and asking if I listened to the latest rap album release.

Part of me thinks that I shouldn’t be offended. There are many popular albums from Black artists and they probably asked everyone that question — plus that AAVE phrase is hip right now!

Yet, another part of me feels that I’m being categorized and addressed based on preconceived notions about my race — I must listen to certain types of music and have a certain type of accent because I’m Black. Additionally, even if these microaggressions do offend me, I feel I can’t comment on it without seeming overly sensitive and combative. They’ll say it was just a joke and it’ll get awkward. It seems better to avoid alienating myself from my peers by staying silent.

Non-Black students may be able to point out more aggressive examples of racism, but the smaller transgressions are always less obvious. Using Blaccents to sound funny is a prevalent microaggression on campus — to this Black person, it feels like vocal blackface.

Nicole De Jesus is a second-year student at Woodsworth College studying history and political science. She is the head of media of Philosophers for Humanity.

Professor W. Chris Johnson taught WGS1029 — Black Feminist Histories: Movements, Method, and the Archives in the fall of 2024. Over the 12 weeks, we learned the historiography and lives of Black feminists from the nineteenth century to our contemporary moment. We read Saidiya Hartman, Toni Cade Bambara, Dionne Brand, Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, Hazel Carby, and so on.

Studying Black feminism raises crucial questions: when and how do Black feminist movements and practices — which stress the intersection of racism and sexism in shaping racialized people’s experiences — evolve into living, breathing frameworks that not only shape our theoretical perspectives but help us create new ways of being and relating with one another?

We have since wondered what, exactly, about Johnson’s class left such a profound mark on us.

Although this course could have easily dissolved into just another seminar — a cycle of painfully endured readings, weeks of attendance rather than presence, a room full of bodies barely noticing one another — the course offered a space where we not only engaged with ideas but also with each other. Johnson’s classroom was a place where we could forge connections, be vulnerable, and collectively dream of freedom.

Reimagining the classroom

Johnson’s class operated beyond the usual academic disciplinary mechanisms in which students are constantly evaluated, graded, and then left to the wayside. Rather, this class had its own kind of rigour; one where we challenged

The

Jena Wouako

Varsity Contributor

each other through laughter and tears to push each other to envision a new world.

In bell hooks’ vision of education as a practice of freedom discussed in her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress, the classroom is a space for selfactualization and growth. Both educators and students engage in a collaborative process of learning and unlearning, facilitated by practices of mutual care and solidarity. As hooks explained in her book, “when education is the practice of freedom, students are not the only ones who are asked to share, to confess.”

In reflecting on the class, we also turned to Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s concept of “study” from their 2013 book The Undercommons They argue that “study is what you do with other people.” This may sound so simple and trite, but there’s a nuance here. Study — not in the traditional academic sense which focuses on laboriously learning facts, arguments, and methods in order to march toward their own, solo intellectual pursuits — but study as the act of ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’ with other people.

Moten’s and Harney’s ways of thinking and doing prioritize the “incessant and irreversible intellectuality,” of the everyday ways of learning. This version of study occurs all the time: grandparents teaching younger family members recipes, grassroots collectives supporting marginalized communities, community groups creating study circles to understand struggles of the past, and reading groups like the Caribbean Grad Student Reading Group at U of T, which encourages students to come together and think with their ancestors.

Johnson invited us to sit with and listen to the Black thinkers and activists across the diaspora to learn from their legacy, and to continue the

rehearsals and discussions they so passionately began. We use ‘rehearsals’ here with the definition theorized by US abolitionist scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who describes Black feminists’ political theorizing and movements as rehearsals — trials and errors, breakthroughs and setbacks in our efforts to build lives otherwise. We strongly believe that the pedagogies in U of T classrooms must aim to support such efforts.

In this spirit, Johnson’s classroom itself was a rehearsal space.

Recognizing oppression in its many manifestations and intersections is only the beginning, liberation demands that we dream beyond. Beyond survival. Beyond the limits imposed by colonial and heteronormative thinking and systems. Beyond the given and what we have been told is possible. But we must also study, create, and rehearse new ways of being together.

Embodying abolition in the classroom

So how do we breathe life into Black feminist theorizing within the classroom? This class taught us that it is by embracing collectivity, listening, and embracing vulnerability. We saw and acknowledged each other as our whole, complicated selves — and, just as importantly, we made space for our ancestors and their teaching.

Although Black, Indigenous, and racialized people around the world were never meant to survive or thrive under colonial structures, our ancestors laboured, dreamed, mothered, and nurtured a future where our freedom remains possible. It is in the present moment, in the small, personal spaces, that abolition must begin; in the relationships we cultivate and the care we extend to each other.

On our class’ last day together, we baked pistachio lemon crinkle cookies and brought them to share. Johnson bought treats from a bakeshop, and another student brought sambuusi — a traditional Somali fried snack. It was not just a celebration that we made it to the end of a difficult term, but that we did it together in the ways we listened to and cared for one another both within and outside the classroom.

In the quiet offering of a smile, a homemade cookie, or a Polaroid picture, we planted the seeds of prefigurative politics — the practice of embodying the values, relationships, and futures we want to create in the present moment — essential for building alternative worlds.

The stakes of this kind of study are that we demand new and more possible worlds for Black, Indigenous, and racialized people everywhere. Always.

Magdalee Brunache is a second-year PhD student in political science and a collaborative student at the Women and Gender Studies Institute. She is co-chair of the Women’s Caucus of the Graduate Association of Students in Political Science and an executive member of OtherWise e-Magazine for Racialized and Marginalized Women.

Stephanie Sawah is a first-year master’s student at the Women and Gender Studies Institute. She is a member of the Caribbean Grad Student Reading Group and an organizer with the Ripple Community Collective.

‘I want a mixed baby’ epidemic is inherently racist The new idealization of Blackness will not create a colourblind, raceless utopia

The 2013 National Geographic article “The Changing Face of America” went viral for its implications of an impending multiethnic and raceless future. The cover featured photographs and testimonies from a projected multiracial generation. Many celebrated this as a sign of an increasingly diverse, utopian future — one assumed to be inherently free of white supremacy and racial hierarchy.

However, the notion that systemic racism could be resolved simply through the growing prevalence of interracial reproduction is naive at best and harmful to Black and mixed-race individuals at worst. It also undermines Black liberation movements that have long fought for the recognition of Black people’s humanity.

I wish to highlight the problematic rise in the fetishization of mixed-race children. I see this trend primarily benefiting culturally insensitive individuals and particularly white people, while harming mixed-race children, who are subjected to objectifying gazes and unrealistic expectations.

Contextualizing the social shift

The fetishization of racialized — particularly Black — sexual partners by non-Black individuals has been prominent since the beginning of European imperialism.

With the end of World War II and the collapse of the European colonial empire, a newfound emphasis on racial integration emerged in Western countries. This shift led some white couples to adopt racialized children, but for potentially insidious reasons.

One reason interracial adoption was popular was because it painted white adopters as humanitarian, colourblind, patriotic, and revolutionary. Many couples thus sought to

use their adopted children as social symbols of cultural progressiveness, setting the stage for what would later become the fetishization of mixed-race babies.

In her 2022 article “Multiracial Bodies, Multiracial Reproduction,” political analyst Sabrina K. Harris identifies social media as a key factor in the modern fetishization of mixedrace children. As Black culture continues to gain mainstream popularity, digital visibility has

often carries ‘white saviourist’ intentions, positioning white parents as benevolent figures rescuing Black children from poverty or other hardships.

In contrast, fetishizing mixed-race children reverses this dynamic: the mixed-race child becomes the saviour, absolving the white parent of their culturally ‘uncool’ whiteness.

only intensified this trend of fetishization. Highprofile figures, such as the Kardashians, have contributed to making mixed-race children a social status symbol. Choosing to capitalize on a child’s racial identity for personal gain not only commodifies their existence but also strips them of their humanity and individualism. Whether deliberate or not, this practice has colonial and racist underpinnings.

Who’s saving who?

Both the interracial adoption trend and the fetishization of mixed-race children are rooted in performativity, though they fulfill different desires for white parents. Interracial adoption

In her article, Harris cites feminist philosopher bell hooks on the commodification of multiracialism: “[Multiracialism] becomes spice, seasoning that can liven up the dull dish that is white culture.”

As whiteness became less socially desirable over time, some white individuals began engaging with nonwhite cultures in pursuit of a perceived sociocultural ‘edge.’

Having mixed-race children can also serve as a protective shield against criticism and self-reflection. This mirrors the common “I can’t be racist, I have Black friends” defence used by non-Black individuals accused of racism. By positioning their Black children as objectified indicators of cultural diversity, rather than human beings, white parents aim to garner a cultural superiority over their ‘uncultured’ peers and can avoid taking accountability for engaging in meaningful anti-racist work — such as education, activism, or structural change.

I do not mean to suggest that interracial families are inherently problematic. The growing societal acceptance of mixed-race children marks a positive social shift toward

racial inclusion and diversity. However, with multiculturalism and multiracial families comes a responsibility to cultivate cultural and racial awareness.

The consequences of racial ignorance within multiracial families seem to rarely burden the white parents; instead, they are placed squarely on the objectified children.

Growing up as a mixed-race person in a racially divisive society is confusing enough, so it’s essential that white parents equip themselves with the cultural competence to prepare their mixed-race children for the reality of their social positioning. Reporter Melea VanOstrand echoes this sentiment, reflecting on the isolation she felt during the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement, where she realized her white family’s ignorance and “colour-blind” view of the world did not align with her lived experience.

Racism will persist in many parts of the world due to centuries of social conditioning embedded in every social institution. This cannot and will not be overcome simply by an increase in multiracial children or interracial families. We can no longer justify ignorance by naivety when racialized people are more at risk of violence with each passing day.

As a mixed-race Canadian, I can only hope that the so-called progressives will realize that eliminating racism and white supremacy from our societies is a complex challenge, one that cannot be solved by simply producing more mixed-race children. It will require significant, meaningful effort and mobilization by everyone — especially those who perpetuate implicit and explicit racial fetishization and objectification.

Jena Wouako is a third-year student at UTM studying criminology, law & society.

Omolola Ayorinde Varsity Contributor

Being Black on Canadian university campuses, such as at UTSC, presents challenges that are often systematically rooted in the structure of higher education.

The first day I stepped onto campus, I felt a mix of excitement and apprehension. At 21, I had already lived and worked in Canada for three years, but stepping into academia as a Black student from Nigeria felt like an entirely different world.

I faced struggles back home as a woman in engineering — discrimination was no stranger to me as I had to work twice as hard to be taken seriously in Nigeria. After arriving in Canada, I feared being Black would add another obstacle where I might be overlooked, underestimated, or even outright dismissed.

My fears were validated in my very first class. Out of the 200 students, only four shared my skin colour. When I dared to raise my hand, my heart pounded, but the professor never called on me. Whether deliberate or not, I felt invisible.

I coasted through the first few weeks, barely speaking. However, that changed during a discussion when I found myself sitting next to a student from Ghana. Our shared cultural experiences created an unspoken understanding. Yet some Black students with a more Westernized mindset seemed to regard me as too traditional, too different. The way I spoke of my perspectives seemed to be foreign to them, making me feel as though I had to prove my worth in ways others did not.

It quickly became clear to me that being Black on campus can be very isolating, especially when university faculties lack diversity and support.

A lack of faculty diversity reveals a systemic anomaly

Lack of Black faculty in higher education

I believe a critical aspect of these challenges stems from the lack of diverse Black instructors at institutions like UTSC. A 2023 article by the University of British Columbia on racism in Canadian universities showed that the absence of Black faculty members in academia creates a disconnect between students and the academic environment. I felt this firsthand when a professor originally from Africa acknowledged my input in class with warmth and genuine interest, allowing me to gain a sliver of confidence.

This absence is not just in numbers — cultural understanding, communication styles, and perceptions of intelligence are all affected. Black faculty with diverse backgrounds can create classroom environments where Black students’ voices are heard and validated, fostering a stronger sense of belonging and academic confidence.

From my own experience, the lack of representation among faculty members leads to cultural gaps that hinder Black students from feeling fully engaged in their academic journey. When Black students have access to Black instructors, alternatively, they are more likely to feel seen, understood, and supported.

The need for Black instructors is not just important for Black students; it benefits the entire academic community by creating a diverse environment for learning. As well as allowing cultural viewpoints and opinions to be part of the academic experience.

Inclusion and cultural understanding

One major barrier to inclusion I noticed is universities’ failure to recognize the value of students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences.

In York University’s book about Canadian campuses, anti-racism advocates and faculty members found that external factors, such as household responsibilities and jobs, can impact their education — similar to my own UTSC experience. As a permanent resident working multiple jobs to pay tuition, I lack the luxury of free time, and these struggles are rarely understood by professors and classmates.