4 minute read

by John Krewson

from BMW 3-Series

by Thomas Swift

by JOHN KREWSON

A Terrible Time

Advertisement

THE AGE OF TRULY BAD CARS IS PAST, BUT THE GREMLIN ABIDES.

T

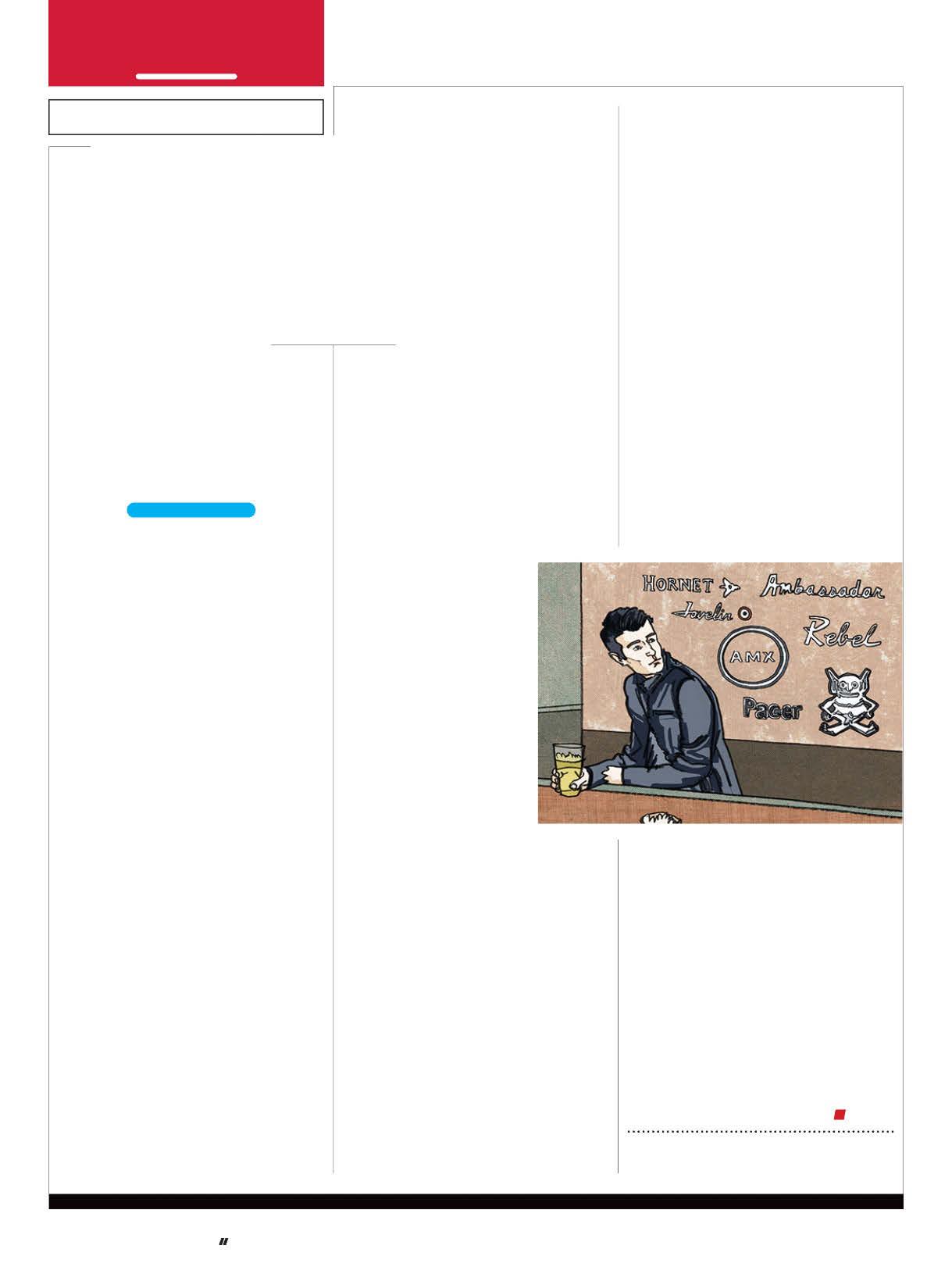

The day I showed up at R&T contributor Colin Comer’s shop bearing the scars of driving his flawless—let’s make that “good as new”—1972 AMC Gremlin across two states, he took one look at me and suggested we hit the nearest bar. Which, it turns out, is where the guys at the Milwaukee American Motors plant went after work. I sat there with a beer, under a wall full of trunk badges tacked up by line workers from years past, and, as you do after a few hundred miles in a Gremlin, thought about my own mortality.

Hornet. Ambassador. Spirit. AMX, a rare ray of sunshine in the AMC murk. Pacer, by God. A smattering of Jeeps, the Rebel, the Javelin. And below them all, Gremlin. What a thing.

If you’re unaware: Gremlins are considered bad cars. I’ll just let that statement sit there.

When the transporter dropped it off, it sat in our parking lot looking bright yellow and deceptively good. It radiated the kind of hazy glow shared by all old stuff, the insidious halflight of nostalgia that filters the negative from memory. You remember how Steve Miller sounded coming over the radio, the smell of beach towels drying across hot vinyl.

Yet the car’s reputation endures. Parking it behind R&T’s building, I passed a woman from a neighboring office as she walked out to her little Corolla. She actually flinched as she recognized the car.

“I used to own a Gremlin!” she called out.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Not your fault,” she said, and looked at her Nineties Toyota like it was Paul Newman. Which, relatively, it was.

Colin got stuck with the Gremlin when a deal for a Shelby Cobra went sour. The AMC was a consolation prize for not being allowed to purchase one of Carroll Shelby’s finest. All of which stretches the definitions of “consolation” and “prize.” I’d volunteered to deliver the car to his shop in Wisconsin, in retrospect stretching the definition of “adventure,” and possibly “drive.”

But then, the Gremlin stretched the definition of “car.” Cheapness was its reason for being. To build it, AMC chopped up the Hornet, pared it down to a price, and hyped that price in advertising: “If you can afford a car, you can afford two Gremlins.” Thus distancing the Gremlin from the definition of “car.”

Colin’s Gremlin admittedly worked okay. It stopped as well as you’d expect for a car of its class and age. It wasn’t dangerously slow. It didn’t overheat in a sticky midwestern summer, the wipers wiped, the headlights lit. By the numbers, not bad.

But, as we’re always saying, cars are about more than numbers. As I wallowed the Gremlin down the road, I tried to find something that didn’t scream cut-rate. The steering wheel flexed. The pedals felt like they moved in mud. The gearshift was imprecise yet heavy and gritty, as if a groaning cable was shoving around sandstone cogs. The interior was a drearscape of mushy tan vinyl.

Talk about the banality of evil. To call something cheap and cheerful has become ironic slang, a way to say, “I’m poor and this thing is depressing.” But it doesn’t have to be like that. Carmakers tell us it’s tough to design within a budget, but look at the iconic cars that have been born that way: Golfs and original Minis and CVCC Civics and Fiestas and so on. They make the world happier for the wage slave, and people who can afford much better keep those cars long after they need them, because they are happy machines.

But the Gremlin isn’t happy. It reeks of paycheck-to-paycheck desperation; optimism was engineered out in favor of meeting a budget, and somewhere along the way, someone despaired of making the car any good.

Despair, Thomas Aquinas told us, is really the only sin. Anyone who bought a Gremlin bought a despair incubator. It’s hard enough to be poor in this world, a status that in so many ways tells you that you’re a lesser person for earning less and does so repeatedly, until you’re in danger of believing it. No one who wants a better life for themselves and their children should have to drive something like the Gremlin, a car that quietly undermines your self-worth every time you creak one of its doors open.

That, plus the fact that Colin’s example refused to hold a course, wandering over hell and gone the entire time I drove it, meant I arrived in Milwaukee irritable and angry.

“That car,” I told Colin, “wants to die. And it should. It couldn’t hold a line if you used glue.”

Colin looked it up and down and said, “Well, of course not. Look at those cheap repro biasplies. They’re inner tubes with sidewalls.”

Cheap tires. The falsest of false economies.

Colin later redeemed his car. He put modern radials on it and “did a few things here and there.” It subsequently became a blast to drive, because Colin is a damn wizard. Oddly, and for reasons I can’t quite explain, I now want it. But when I sat at that AMC bar, I thought about all the people who bought bad Gremlins.

Gremlin. Gone now, killed by Golfs and Civics and Fiestas, dead and passed into cheap, cheap legend.

I can’t shake the feeling that the ending should make me sadder than it does.

John Krewson is a senior editor at R&T. He, too, was born in Wisconsin and radiates a hazy glow.