cul BODIES

Can you eat your pets?

What does the ADF graffitied everywhere mean?

Why is your body taking up space here?

Wow the Cul has so many guest articles now!

Can you eat your pets?

What does the ADF graffitied everywhere mean?

Why is your body taking up space here?

Wow the Cul has so many guest articles now!

Independent anthropological magazine

Cul is connected to the Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology department at the University of Amsterdam.

Editors in Chief: Alex Dieker Morrigan Fogarty

Graphic Design: Alžbeta Szabová

Image Editors: Alžbeta Szabová

Carme Ferrando Soriano

Helena Peters

Text Editors: Eduardo Di Paolo

Iris van der Goes

Luca van Opstal

Daria Nita

Social and Travel Coordinator: Amelie Clarke

Cover: Hieronymus Bosch

Cul magazine is always searching for new aspiring writers. The editorial team maintains the right to shorten or deny articles. For more information on writing for the Cul or advertising possibilities, email cul.editorial@gmail.com

Printer: Ziezoprint

Prints: 200

Printed: December 2024

ISSN: 18760309

Cul Magazine

Nieuwe Achtergracht 166 1018 WV Amsterdam cul.editorial@gmail.com

Follow us on Facebook and Instagram and check out our website! @culmagazine http://culmagazine.com

Dear Readers,

The bodies you see littering the front of this edition are not just there for show. We’ve dedicated this edition to bringing you writings focused on the place where our senses lie, the Body. Just as a body never stays the same, we feel that the Cul as a living magazine needs to be adapted, and so we have taken to the art of Body Magazine Modification to bring you a new edition with new types of articles and new content organised refreshingly.

We are grateful for the immense amount of guest articles we received and are exceedingly proud to be an outlet for so many people to submit their fascinating essays. We’ve created new categories to showcase this writing: our guest articles shine in the first half of the magazine while we, the staff of the Cul, take over and write on media, anthropology, and the city of Amsterdam in the second half. We’ve also added a dedicated poetry corner, a soapbox for complaining, and a new ‘Letters to the Editors’ section where you can write to us about the magazine.

We live in tumultuous times, and we feel that it is necessary to mention that we are seeing others who want to deprive you of your bodily autonomy, in the form of healthcare, in the form of incarceration, and in the form of limiting your ability to exist as you please. More and more, we are seeing those that would deny you the right to live. We are committed to maintaining a space in which the expression of those bodies who are denied access to these things have a voice to speak, and we are ready to publish your words.

Best

Wishes, Morrigan Fogarty Alex Dieker

Text Rubén Gómez Image Alžbeta Szabová

There are some things that transport you back to your childhood years. For you they may be an old tv show’s theme song, the sight of your first stuffed toy, or the taste of your family’s signature dish. I relate to all of those, but there are few things that bring me back like peeling a good shrimp. When cooking around the different coasts of Latin America, my mom handed that dirty work to me because it allowed her to prep the rest of the kitchen while I did it. Through a lifetime of experience being my mom’s kitchen assistant, I have ingrained it into my habitus to behead, shuck, pair and devein whole shrimp in record time. Having always admired crustaceans, there is a sad comfort and intimacy in the crack, the smell, the texture, and the ability to get to see such amazing creatures from up close, which used to be a thing that only happened once every month for me.

But suddenly I started to see shrimp a lot more when my dad’s hobby turned a good chunk of my house into multiple aquariums. Now there I was with an aquarium just for me, that I could fill with any fish I wanted. But I didn’t want fish, I wanted shrimp, and many of them. So I got ghost shrimp, crawfish, and cherry shrimp of all different colors. I spent the larger part of the pandemic taking care of them, feeding them religiously, cleaning their tank, checking their water conditions, and constantly improving their tank so they each had their own personal shelters. I fell in love with them, and on the rare occasion that one passed, I would grieve them for days. Sometimes my mom would see me so sad that she would invite me to cook shrimp together just to lift my spirits. The hypocrisy of this was not above me, but there was just something keeping me hooked on shrimp.

I’ve spent the last years trying to reconcile with this hypocrisy, justifying it in almost every way possible. “It’s our GodGiven right”, “They can’t feel emotions”, “Everyone does it”, “A predator would have eaten them otherwise”. Not one of these felt right, none of them hold up when I remember my beloved pets, nor when I eat my favorite meals. Their bodies are to me like the water they live in and the oil in which I cook them, an irreconcilable dualism of bodies to nurture and to be nurtured by. Yet, in all my attempts to justify this hypocrisy, there is one rationale that persists: the deep sense of cultural identity tied to shrimp consumption.

Despite this internal conflict, it feels to me like shrimp are more than just the material bodies they inhabit, they are intrinsically woven into the person I see myself as. Growing up in different coastal cities around Latin America, shrimp have been a symbolically important aspect of how I define myself. Shrimp are in the dishes I cook, but also in the music I listen to, the sayings I use, the stories I tell, and the jokes I hear. One particular joke was sure to be told exactly the same anytime I told anyone that I owned shrimp: “You should cook them in garlic and olive oil”. It’s like it came preprogrammed into the people I interacted with, and through them, into me. Especially now living away from home, I look for ways to be more latino, to be the home I miss, and in those moments the joke resonates with me, telling me who I’m supposed to be.

But deep down, I know I'm not supposed to be anything. There are many aspects of my cultures that I can take from, some of them lovely, some of them violent. And there is a certain violence inherent to peeling those bodies that could have been my pets, to eating them by the dozen in one sitting, to boiling their shells to extract their essence, their souls, to discard them. I’ve been trying to stay away from that violence lately.

While I appreciate the significance that shrimp have in my sense of self, I also recognize that I am not my heritage alone. My identity can be formed by my evolving understanding of what it means to live with compassion to the bodies around me. I try to forge a future that reflects the kind person I want to be, and even when I falter, I keep trying because I know that I can be more than what I’m supposed to be.

Text & Image Emma Remedios Lameiras

Space is political, but it is depoliticised. We have gone beyond the point of harsh segregation (debatable) that decided who to Other and who to listen to. In my metro journey towards my destination, I am reminded of how my body takes up space, which can be interpreted as an act of protest, a bold becoming. We speak loud and it becomes a social statement. Our ‘right to the city’ is a negotiation: what city? Whose city? Why (are you in this city)?

“The force of thundering drum and bass and the howling, raging man’s voice intoning ‘Ready for war’ over and over was a soldier’s power, was itself a desire for war, a hyper vigilance that was a high, a readiness for anything, an armor made out of attitude” — Rebecca Solnit in Recollections of my nonexistence. The excerpt came to mind as I hear the rumblings caused by football fans on the other side of the carriage, how the fans are enabled and encouraged by their brotheren to be loud and messy, to instigate unwanted conversations and take up audable and physical space. Images are conjured up in my mind: peace and tranquillity divided, tectonic plates shake, nations draw harsh lines of geographic annex— women at war within the liminality of public space. Wishing to “be the armour and not the vulnerability behind it”, I am reminded of my feminine body in public transport, and this experience as a pressure cooker of unpredictability, of uncertain peace. I am wedged in between (and reminded of) bodies on this metro.

The liminality of public transport stands in two ways: transport as liminality between origin and destination, and transport as a vessel restricting bodily movement, a space of uncertain bodily autonomy. Space is not inherently gendered, but entitlement to it can be. The historical residues of conquest and its justification linger in public spaciality and entitlement. It is man’s lane, road, and geographic annex— they are public (available) to him, thus are the beings that linger within his geography. And yet all is ‘culture’— it would not have been an annex of territory coming from nature, nor would it have ever been dichotomous; the coin has two sides but it is one coin (an alloy of raw materials, but ultimately man-made).

The situation of being physically restricted on the metro evokes frustrating recallings that I am once again thinking of more: calculating the space in between me and his manspread, trying hard to accomodate for enough space so I would not be breathing in another’s direction while he clearly breathes in mine, trying to keep to myself with one hand on the pole while his whole back leans in, on edge because in the back of my mind a slip of an eyecontract could be misinterpreted as an invitation to talk, laugh, ask where I’m from, be closer than necessary.

I want to take up more space but at the same time there is danger in it. In a visceral sense we all take up some amount of space, some of us just need to calculate more than others. Is it for my own comfortability? Or just in solidarity with the other uncomfortable bodies that I sense on the metro on this forsaken day (Ajax game)?

I shall end with a poem (still on this metro):

In the essence of taking up space, something differs.

It is historical conditioning and entitlement all together.

As bodies that take up space, we coercively forget how we interact with the bodies that breathe a different amount, that hurt a different amount; bodies that are constantly resisting.

Our bodies are ours, though we are not singular— that we tend to forget.

We are taught to be small, to be bold but withdrawn. We are told to fold into ourselves, but to never keep our beauty to ourselves. Our space is sacred, safe, and considerate.

Confine yourself to smallness, hush and fold. Undo yourself, unto yourself.

Or please, don’t.

Text Tonko Boer

Image Alžbeta Szabová

Of we het nu willen of niet, ik kom maar gelijk met de deur in huis vallen; je gaat dood. Jouw lichaam zal op een dag niet meer werken zoals het doet terwijl je dit nu leest. Je hart zal niet meer kloppen, je bloed zal niet meer stromen en je ogen zullen voor altijd gesloten blijven. Er zal zelfs een dag komen dat je lichaam helemaal niet meer bestaat. Meestal is dat na twintig jaar zo, wanneer zelfs je botten volledig verdwenen zijn. Het kan natuurlijk ook zijn dat je lichaam wordt gecremeerd, dan verandert het gelijk in korreltjes as. Ik snap dat dit luguber kan overkomen, alleen is het wel de realiteit die we onder ogen moeten zien. De vraag is dan ook hoe jouw naasten zich jou zullen herinneren, zonder de aanwezigheid van je lichaam.

Eerder dit jaar overleed mijn moeder aan de gevolgen van borstkanker. Als een schok kwam het niet per se, want ze was al twee jaar bezig met de strijd tegen deze invasieve ziekte. Wat mij wel overviel is het vraagstuk dat ik hierboven introduceerde. Hoe kan ik ervoor zorgen dat, ondanks de afwezigheid van de fysieke versie van mijn moeder, ik straks toch aan haar kan blijven denken, en zo haar aanwezigheid kan voelen. Ik kwam er al snel achter dat dit mijn copingstrategie zou worden om om te kunnen gaan met de afwezigheid van mijn moeders lichaam.

In de week na haar overlijden kwam het idee bij me op dat ze bezig zou zijn met een reis. Dit idee ontstond hoogstwaarschijnlijk door een mix van Boeddhistische en Hindoeïstische verhalen die ik had gelezen over reïncarnatie. Toch probeerde ik het eigen te maken door er zelf een twist aan te geven. Voordat mijn moeder begraven zou worden, werd haar lichaam eerst nog een week lang opgebaard, zodat haar geliefden afscheid konden nemen van haar fysieke omhulsel. Ik merkte al snel dat dat voor mij erg goed werkte, want het gaf mij de kans om de transitie te maken van het zien van mijn moeder als iets anders dan een menselijk lichaam. Het gaf me de tijd om na te denken over het gemis, maar ook over hoe ik dat gemis zou kunnen verwerken door haar aanwezigheid te verplaatsen naar iets dat ik nog wel met mijn ogen kan waarnemen. Ik kwam erachter hoeveel waarde ik eigenlijk hecht aan het zien van mijn geliefden en hoeveel emotionele betekenis hun aanwezigheid in fysieke vorm voor mij heeft. In iemands ogen kijken, ze een knuffel geven of er eentje krijgen, dat zijn momentjes waarbij je zielsveel liefde voor iemand kan voelen. Maar toen dat niet meer kon, moest ik zelf een manier vinden.

Eerst wil ik een idee geven van hoe universeel het is dat mensen op zoek zijn naar een nieuwe vorm van aanwezigheid van iemands ziel. In Bali gelooft men bijvoorbeeld dat de geesten van voorouders samenkomen onder een banyanboom. Binnen het Japanse Shintoïstische geloof leeft het idee dat iemand na het overlijden een ‘kami’ wordt, en voortleeft als een deel van een rivier, als boom of als steen. Ditzelfde idee leeft ook voort in de Lakota cultuur, wat een inheems-Amerikaanse volk is dat gelooft in een vorm van herboren worden als een onderdeel van de natuur, bijvoorbeeld in een dierlijke vorm zoals een bizon. Deze voorbeelden komen niet veel voor in mijn cultuur. En toch kan ik hier veel inspiratie uit halen. Ik bleef achter met de ziel van mijn moeder, haar nalatenschap. Met zo’n ziel kan je ervoor kiezen om het te laten bij wat het is, als in; het lichaam is dood, dus dat is het… Of je koestert het juist door naar symbolen te gaan zoeken die je aan de overleden persoon laten denken; andere fysieke elementen die nog wel aanwezig zijn in je leven, zoals een boom, een steen of wellicht een dier. Zelf kan ik mijn moeder zien in het licht, in een vlinder en in het water. Alle drie zal ik ze toelichten.

In het licht, omdat op het moment dat mijn moeder haar laatste adem uitblies, mijn broertje op de fiets onderweg naar huis was, rond klokslag half acht naar boven keek, en een prachtige lichtverschijning door de bladeren zag. Hij vertelde dat toen hij thuiskwam aan mijn vader, die het een paar dagen later ook met mij deelde.

In een vlinder, omdat mijn moeder in de weken voor haar overlijden vaak in het ziekenhuis was. Een ziekenhuiskamer is meestal niet zo gezellig en het enige wat ze kon doen was uit het raam kijken. En wat zag ze daar? Een vlinder. Niet één keer, maar meerdere malen per dag. Het was alsof het ons iets probeerde te zeggen. Hier bleef het overigens niet bij, want tijdens haar laatste wandeling in het bos kwam er een vlinder op de arm van mijn vader zitten. En regelmatig als ik haar rustplaats bezoek, vliegt er een vlinder langs.

In het water, omdat ik de symboliek van water zo mooi vind. Het stroomt, het vloeit en het omzeilt alle obstakels die het in de weg zit. Dat kon mijn moeder ook zo goed en dat is iets wat ik graag van haar wil meenemen.

Door deze drie elementen kan ik mijn herinneringen aan mijn moeder blijven koesteren en herleven. En soms combineren ze zich; een vlinder die aan de oever van een rivier tijdens zonsondergang langs vliegt. Zo’n moment voelt dan bijna onwerkelijk.

Tenslotte wil ik als boodschap meegeven dat we ons moeten realiseren dat we ons lichaam te leen hebben. Dit omhulsel, ook wel ons ‘aardse kostuum’, zal op een dag los komen te staan van onze ziel. Hoe gewoon wij het ook vinden dat deze twee onlosmakelijk aan elkaar verbonden zijn, toch is het echt zo dat de dood om de hoek kan liggen. En dat geldt voor iedereen, alleen is het zo dat het voor de een iets duidelijker is dan de voor de ander. Iemand die in de terminale fase zit omdat deze persoon kanker heeft, weet dat hij of zij binnenkort zal sterven. Maar als jong mens ben je daar minder mee bezig. Ik wil dan ook niet zeggen dat je continu moet denken aan sterven, je bent als student vaak in de bloei van je leven. Wel is het belangrijk om de realiteit onder ogen te zien, namelijk dat we moeten realiseren dat onze lichamen kwetsbaar zijn en dat ze aandacht en verzorging verdienen. Tot op de dag van je dood is de ziel namelijk te gast in een lichaam. Zorg er dus goed voor. En weet dat als je ooit zelf afscheid moet nemen van het aardse omhulsel van een geliefde, symboliek je een helpende hand zou kunnen reiken in het voelen van de aanwezigheid van deze persoon. Zelfs als je een atheïst bent, want uiteindelijk gaat het erom dat je het verdriet van gemis kan vervangen door de blijdschap van het koesteren. Iets waar de Shintoïsten, Balinezen, en de Lakota uiteindelijk ook naar op zoek zijn. Geloven in iets dat misschien niet echt is kan zo magisch zijn, vooral als het gaat om iets dat zo abstract is als het nooit meer kunnen zien van het lichaam van een van je meest geliefde.

In het water, omdat ik de symboliek van water zo mooi vind. Het stroomt, het vloeit en het omzeilt alle obstakels die het in de weg zit. Dat kon mijn moeder ook zo goed en dat is iets wat ik graag van haar wil meenemen.

Text Amber Rozenrichter

While some may regard gender fluidity as a modern phenomenon, a deeper exploration reveals that fluid understandings of gender are woven into many rich and ancient traditions, including those of the African continent, before the shadows of colonial powers fell upon them.

In pre-colonial West Africa gender fluidity was not only accepted but celebrated. Here, gender-nonconforming individuals were honored for their distinctive expression and perceived as holding a sacred connection to the divine realm. This bond was understood to bring blessings not only to the gender-nonconforming person themselves, but to the community as a whole. This cultural reverence for gender diversity highlights a tradition in which spiritual and social well-being were deeply intertwined, enriching the lives of all who shared in it.

The gender theory of Oyèrónk Oyěwùmí, a renowned scholar in sociology and gender studies, offers essential insights into understanding perspectives on gender within pre-colonial West African societies, particularly as they contrast with Western frameworks. Oyěwùmí argues that, in Western thought, biological determinism forms the basis for constructing categories of gender, race, and class. This allows biology to serve as a legitimizing tool for claims rooted in social, economic, and political ideologies. This approach echoes colonial narratives that justified dominance and privilege through assertions of biological superiority. Oyěwùmí argues that Eurocentric culture combines social constructionism with biological determinism, creating a worldview deeply rooted in what is perceived visually. Through imperialism and colonialism, these ideologies were imposed on African societies. However, in various communities within pre-colonial West Africa, gender was not organized within a rigid binary framework. Instead, a more fluid understanding prevailed, influenced significantly by their spiritual and religious traditions.

Our focus will now turn to Yorubaland, a cultural region situated in present-day Benin, Togo, and Nigeria. Oyěwùmí states in The invention of women: making an African sense of Western gender discourses: “In Yoruba culture social relations derive their legitimacy from social facts, not from biology”. In this culture the focus is more on ‘age’. In Yoruba culture, they do not privilege

the physical world over the metaphysical.” Yoruba people engage with the world through a variety of senses beyond the visual, a phenomenon Oyěwùmí describes as the world-sense of pre-colonial Africa. This perspective is metaphysical, encouraging a sensoryengagement with the world rather than a strictly sight-based approach. In this context, gender was understood as a fluid spectrum, allowing individuals the freedom to explore and express themselves across a range of identities.These identities are not solely based in a single sense, like sight, but are shaped by a blend of many senses that reveal the individual.

This distinction can be partly understood through Yoruba metaphysics, where the concept of good and evil operates differently from the binary framework found in European christian thought. In Yoruba culture, various aspects of the divine are honored through offerings and rituals dedicated to specific deities. Scholars debate whether Yoruba religion is polytheistic or monotheistic: while it recognizes an almighty force, Olodumare, it also venerates numerous deities: the Orishas. The Orishas manifest a spectrum of forces that encompass masculine, feminine, and intermediary qualities, believed to be present within human beings as well. Individuals who embody what might be considered both masculine and feminine traits, hold a significant role as healers and mediators with the spirit world. Since they have access to more parts of the self. Within this tradition, these individuals are not categorized as non-binary, as the concept of a rigid gender binary is absent. Instead, communities used unique names to honor these individuals, describing them as powerful figures who harmonized both masculine and feminine forces and brought this into their spiritual and healing practices.

Gender fluidity and expression were, rightly, celebrated as vibrant and enriching aspects of human identity. European colonizers often associated the acceptance of same-sex relationships, diverse gender expressions, and varied sexual behaviors with African spiritual beliefs, labeling the Yoruba religion as heretical. Western anthropologists interpreted these cultural practices as indicative of what they deemed outrageous sexual behavior. They perceived the openness surrounding gender and sexuality as a direct threat to their own social constructs and belief systems that underpinned Western society.

In Angola, where similar religious and spiritual practices existed, one Portuguese soldier remarked in 1681: There is among the Angolan pagan much sodomy, sharing one with the other their dirtiness and filth, dressing as women. And they call them by the name of the land, quimbandas … And some of these are fine fetishers … And all of the pagans respect them and they are not offended by them and these sodomites happen to live together in bands, meeting most often to provide burial services.” The freedom of expression found within indigenous African cultures posed a challenge to European laws and christian values. Especially, since the gender-nonconforming people seemed to hold a significant spiritual position, such as providing burial services,within their communities. When Europeans colonized West Africa, they not only enslaved its people but also systematically tried to erase the existing indigenous philosophies, cultures and traditions. The colonizers made it their mission to both dominate and dehumanize the people of West Africa. This process of cultural erasure was a fundamental aspect of colonialism and slavery. For the christian church, it was imperative that colonizers dismantle the indigenous cultures of West Africa and impose christianity, thereby neutralizing any potential threats to the christian society. Fortunately, they were not entirely successful in colonizing the minds and hearts of the people. Many of their stories are lost, but luckily some survived through time. In honor of the gender-nonconforming individuals who endured this oppression, I would like to introduce two remarkable figures: Vitoria and Francisco.

Vitoria & Francisco

The Inquisition in Lisbon recorded the arrest of Vitoria in 1556, an enslaved person from Benin. Upon her arrival in Brazil with Portuguese colonizers, she rejected her slave clothing and instead wore a white waist jacket and a large skirt that she found in the stables of her enslavers. This act of reclamation served as a rejection of the bondage imposed upon her. Later brought to Lisbon by her enslaver, Vitoria started working at the riverbank as a prostitute. She was a gender nonconformist who identified as a woman and chose to wear clothing that was traditionally made for women, while also wearing a jacket traditionally reserved for men. Vitoria was known for her ambiguous presentation which confused those around her. Despite her self-identification as a woman, the Portuguese Inquisition found this unacceptable. According to their accounts, she was said to lure men in at the riverbank “like a woman enticing them to sin”. This disturbing statement reveals the depth of why Vitoria was seen as a threat and the rationale the colonizers used to justify their stance. It underscores the clash between her identity and the restrictive norms of a colonial system intent on controlling and categorizing human existence. Additionally, the connection that is made between women and sin shows us part of the religious dimension of the matter. Through this lens, we can observe the tensions between individuality and an imposed order aimed at suppressing diverse expressions of selfhood.

According to historian Sweet, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Vitoria’s case underscores how the interpretation of her gestures lay at the heart of her arrest. Observers noted her winking at men and carrying water from the river on her head – actions that were considered female gestures. Yet, others claimed to have seen her doffing her hat, agesture associated with masculinity. This fluidity of gender expression posed a significant threat to the Portuguese Inquisition. Ultimately, Vitoria was arrested on charges of sodomy and sentenced to life imprisonment. Records of her arrest reveal that the inquisitors focused primarily on her sexual behavior, yet other aspects of her identity may have intensified her perceived threat to colonial authority. A man named Jorge Fernandes testified that Vitoria had healed him and other men from an unspecified ailment, establishing her reputation as a profound healer. Her healing practices further marked her as a danger in the eyes of the colonizers, likely contributing to their urgency to detain her. The resilience of individuals like Vitoria, who boldly expressed her authentic self amidst the atrocities of colonialism, allows us to grasp the historical context of gender-nonconforming identities worldwide. It is crucial to recognize that trans, non-binary and gender-nonconforming individuals have existed throughout history; their presence is not a recent phenomenon. In truth, the erasure and hatred directed toward these individuals are deeply intertwined with the legacy of white supremacy and colonialism.

In 1591, a similar case emerged involving an enslaved African person named Francisco, who was denounced for sodomy by a Portuguese man named Mathias Moreira. Francisco resisted their enslaver ’s authority and continued wearing feminine clothing and expressing themselves in a nonconforming manner. When Moreira was called to explain Francisco’s gender expression and behaviour to the Portuguese Inquisition, he uttered a deeply troubling statement, steeped in lies and ignorance: “In Angola and the Congo … the negro sodomites who serve as passive women in the nefarious sin use these loincloths, and in the language of Angola and Congo, they call them jinbandaa, which means passive sodomite”. The colonizers labeled these individuals as abnormal, employing a European interpretation of these African terms to justify their views. Linguist Malcolm Guthrie notes that both uimbandas and jinbandaa were translated from a European perspective, resulting in misleading interpretations that carried negative sexual connotations. These translations arose from the homophobic and transphobic biases of the colonizers. Guthrie explains that the root of these African terms, “-mbanda,” are derived from words meaning healer, medicine man, or spirit medium. In other words, the colonizers translated what the African people call healers and spirit mediums to derogatory homophobic slurs. While the true translations reveal the deep connection between gender-nonconforming individuals and their roles within the social and religious spheres in pre-colonial West Africa. These individuals were condemned by thecolonizers for what they were praised for within their own communities: fluid gender expression and the ability to heal others through spiritual forces.

Text & Image Miguel Luis Calayan

“I feel like I’m getting butchered,”

Ana said as we caught up over coffee.

Last January, she found a familiar lump on her breast. The doctors confirmed her fears that her cancer, which had gone into remission a few years ago, had returned. This time, the only way to make it out alive was by sacrificing one of her breasts.

Participating in this project, in her eyes, was a means of reclaiming agency. Baring her skin, peering into the lens, basking in the soft light, she proclaimed herself the subject rather than a mere object. Without reservation, she showed off her breasts. These, to her, are symbols of love and nurturing. To lose one of them, she says, feels like losing part of her femininity. She opted to replace the malignant member with silicone in a couple of months.

Growing up, Elai felt more boyish than other girls. This was not a matter of simply being rougher and not dainty – he felt there was a stark difference between how he sees himself and how his body presents itself to the world. He then sought to consolidate the two ideas: at age sixteen, he started wearing a binder around his chest. At twenty, he had a mastectomy.

“How you’re perceived is how you feel,”

he said.

Regarding how they feel about their breasts, Elai and Ana sit on opposite ends. Ana grieved the removal as it marked the loss of identity, but Elai celebrated the excision as it meant gaining his masculinity.

Finally, we have Em, whose breasts are neither a signifier nor an obstacle to their identity. They are simply breasts.

Without disregarding the importance of gender, they also maintain that it does not need to be at the forefront of how we perceive others. Em would rather invite us to look into other aspects of ourselves. Em has a collection of seemingly symmetrical tattoos but upon closer inspection, are not. This ink on their body acts as armour – not from any danger, but from expectations.

“By augmenting my body, I get to give this clue that there’s something different.”

They are not meant to ward anyone off. Rather, they mean to say, look deeper.

Ana, Elai, and Emma have each – in their own way –chosen to maintain agency over their anatomies. Through the removal of breasts, the reconstruction of one, and the carving of symbols on one’s skin, they declare that while we may not have control over the bodies we’re born with, we do have control over the identities we embody. These are maps full of bumps and curves, but we still get to draw the lines.

This is a shortened version of Miguel’s photo essay ‘Lines, Bumps, and Curves’. You can find the full version…here (where?).

Text Juliana Könning

Human bodies are constantly involved in the cosmopolitics of everyday life. The senses are the gateways to the outside world, but not every person can perceive and regulate sensory stimuli in a way they would like to. For those who have difficulties with this, sound often presents itself in the form of noise or disturbance. I probed into my own aural experiences— specifically in exposure to noise—as a person diagnosed with ADHD. During this process, I had many moments of doubt and was confronted with my positionality. Writing this text has revealed to be, in itself, a process that has made me profoundly rethink how I listen, how sound is organized and how I need to defragment my soundscape.

When thinking about sensory awareness in my day-to-day life, the aural seems to be a conflictual field of interest. Being presently aware of my surroundings is something I struggle with. Listening is a ‘nomadic sense’ because sound is a fleeting phenomenon. If I am not tuning my senses to a sound that briefly presents itself, the sound will be lost to me. Sound can be on the one hand overwhelming and, on the other hand, often easily fading out of my conscious experience. I am eager to tackle my experiential difficulties to enable a more holistic experience through different senses, rather than unconsciously blocking some connections I can have to my surroundings.

As a person with ADHD, much of the time, most of my thinking is reserved for either reflecting on past situations or preparing for future ones. When I actively try to engage with the here and now, I often have the experience of suddenly being submerged in sound; as if it reenters my focus just by being present in the moment. So I have come to link the two together; when I am consciously experiencing sound, I am grounded in the present.

I have a lot to learn when it comes to the practice of listening. It often reveals itself in a form that ‘disturbs’ or ‘overwhelms’ rather than ‘enriches’. Sounds such as loud wind, trams passing by, someone snoring irregularly or loudly stirring their tea, anchor me in the here and now and trigger me to run from the scene. I gather that my body—being a space of conflict when it comes to sound—is an excellent tool for exploring how sound and 'being in the present' are connected.

To illustrate, I share my experience when I visited a performative reading in 2021 in puntWG, by artist Anastasija Pandilovska. The performance referred to the changed landscape of the city center of Skopje, the hometown of the performer. A government-initiated project, named Skopje 2014 became a topic of controversy among the city's population. Pandilovska commented: “Despite the resistance, metal partitions take over the square, the river’s left bank, and spread into different areas of the centre. Drilling sounds mark the start of the building process”. Façade_Override_Façade made use of two sound-making mediums. While playing sounds that Pandilovska recorded of

the construction work around her apartment, she spoke to us about her experience of being submerged in that sound. The loud sounds of the recorded construction work made most of her words inaudible to me. I kept trying to move my head in ways that would make her voice override the sounds of the construction work. My focus was on the sound of her voice. I did not pay attention to the construction sounds and I was oblivious to what these sounds could mean to me. But I was quick to attach a label: sound became noise.

My body and brain are constituted by a culture that effectively breaks down reality into classifications that disable a more unified and holistic way of listening. Western health frameworks indicate that my listening experiences are impaired by an overt focus on ‘background noises’, and a lack of capacity to focus on a task. Maybe my ADHD body feels impaired because my Western context taught me that holistic hearing is an inability to focus. During Façade_Override_Façade I was frustrated with my inability to hear what I thought I was supposed to hear. I was failing to block out ‘noise’. If I would not have been so focused on what words were communicated, I might have had a very different experience, an event-specific moment of being presently immersed in sound, rather than a mere sense of missing out on content. Still being impervious and green in the practice of wholesome listening, it is apt to rethink my current listening, as I have tried to do. Rethinking this experience, I wonder whether my body is actually very well-equipped to engage with sound holistically and immersively.

Being more attentive to sound is something we can learn. Since my experience with Pandilovska’s performance, I have attempted to be more attuned to sound. As part of this search, I have been listening to several videos of Indian singing bowls on YouTube. Since my acquaintance with the singing bowls, I now hear wavelike vibrations in the wood on metal steps when I walk the stairs up to my flat in Amsterdam. The moment when I am on the staircase has become a moment when I am pleasantly grounded in the present. It seems that I am learning new ways to listen. But I have doubts. Is it apt for my body to learn from ways of listening outside of the West? Am I ostensibly pulling ancient Indian practices into my Western knowledge frame?

My Western context constructs a fragmented way of listening and my body is conditioned to listen accordingly. However, my ADHD body does not easily adapt to this way of listening, and my listening experiences have suffered accordingly. I want to engage with more holistic forms of listening as a way to deepen my experience of my surroundings. These can be found outside the West (e.g. Indian singing bowls), but my body is still Western. Which leaves me with the question: In my attempt to remedy my sensory experience, and resist Western fragmentation, am I allowed to search for more holistic experiences outside the West?

Text Daria Nita Image Helena Peters

Mezrab is self-titled “The House of Stories”. It is open almost every night, hosting a variety of storytelling events such as myth nights, open mics, professional storytelling, in addition to live music events and more. I got in touch with Phillip Melchers, a storyteller, host, and theatre writer/performer. Our 45-minute interview resulted in 7,148 words of wisdom on performance art, vulnerability, magic, community and transcendence. With great effort and sorrow, I cut it down to 1,500 words: here are some highlights from our conversation.

I had planned for this interview to be about body language and how the body can be used as an instrument for storytelling. But before I started with specific questions, I wanted to hear about Phillip’s initial thoughts on the topic of the body. He took the conversation in a totally different direction (that I believe ended up being a much better starting point).

Phillip has a lot of experience in being on stage as he performed in public speaking when he was a kid, and then went off into theatre, then a bit of poetry, then storytelling at Mezrab, and now has co-written a play (see the bottom of the page for more info!). It is something that he always felt comfortable doing. However, one thing that he thinks we need to start recognising, in terms of performing, is just how embedded the fear of societal rejection is within us. He doesn’t think it's something that we can entirely get over. It can be suppressed in order to do what we need to do. But, as he puts it, “there is always that self-correcting mechanism in the back of the head that's still running this diatribe of saying, ‘Are you saying it right? Are you connecting to the audience?’”. I asked him what the word “diatribe” meant. He confirmed the definition I found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary: “a bitter or abusive speech”.

I found it so telling that his starting point was not how his use of his body affects the audience, but rather how being in front of an audience affects his body. As if to subtly correct me and say that the work starts from within. I asked him if storytelling training also focuses on the body or just on the story itself, and he replied that he learned to understand how to body scan and where nerves are affecting him. He thinks “it's the little ripples in the body that end up having a big effect if you don't take them into consideration. There are so

many micro ways that humans read each other's bodies in terms of body language, things that we're not aware of, things that feel very, very subconscious. So, if you don't feel on the micro-level kind of relaxed and really, really open, then it's gonna be harder to connect to your audience because they're gonna react to that tension that you're unwillingly getting off.”

He added: “For as much as there's the bad feelings, the tension in the field, there's also good feelings, the release, the catharsis, things that you can really use to your advantage if you understand how these feelings kind of swell and sway within you while you're performing. I mean, in my visualization of it, it really becomes, if I can really, really get into it, and I don't always do it, but it can really begin to feel like this wave that's swelling and shrinking inside of you. And then, really, you can start to pull on the magic at the moment as memory kind of overlaps over reality, and then you're just really speaking from these very dense personal memories.”

“Everything that's important exists in the nuance between two spaces”.

My next question was a bit more metaphorical. In anthropology, we deal with a lot of anti-capitalist ideas, criticising the fact that in today’s society, everything needs to be for profit, and if it’s not making money, then it’s considered not worth it. There is also a lot of discussion about how performance art or art in general kind of goes against that capitalist ideal because art is an end in itself and not a means to an end. I asked Phillip if he agreed with this, and if he thinks about it when he performs.

His response?

“Absolutely.”

He shared a quote from Michel Duchamp (the guy who painted the toilet bowl):

“I think art is the only form of activity through which man shows himself to be a real individual. Through it alone, he can move beyond the animal stage because art opens up onto regions dominated by neither time nor space.”

It turns out this was actually something Phillip had been looking into a lot recently. After listening to a podcast on witchcraft discussing amongst other topics, what the oppression of witches meant historically, he and his friend started discussing the nature of magic.

“[…] It created this conversation of how maybe it's more about magic belonging to the oppressed or the minority rather than the majority, because in order for magic to work (and I'm using magic in very metaphorical terms) it is intuition-based. It is about embodying yourself, becoming this individual feeling process outside of the machine of society, or capitalism, or the institution or whatever you want to call it. I find that if you are within a system that doesn't really operate for you, then you seek out your own system of feeling that subscribes better to your individual self, that speaks true to yourself. It's only when you're feeling oppressed that you begin to question what is around you. And I think magic or art or performance, all of these things are really based in that experience of developing the individual against the institution.”

“On the small communal scale, when you really start to look at people who build covens, communities, you really start to see that there is this need to express, this need to feel magic. And I think it's because, to me, magic comes from the subconscious parts of ourselves that we don't fully understand. Our emotional processes are so complex that when you really sit back and you start to feel yourself, you can only call it magic.”

Phillip went on to explain that in his opinion, institutions are made for making things fit into strict categories, although nothing in nature actually fits in there. You win at the capitalist game when you think in binaries, but this binary reality is never reflected in nature: not in gender, not in body and mind, not in life and death… “Everything that's important exists in the nuance between two spaces”.

I brought us back to this notion of working for the capitalist machine. Marxist analyses suggest that modern work is meaningless because it makes us tiny cogs in a machine, and we don’t really see the product of what we’re making. And I feel like art is the opposite of that. I asked Phillip if he thinks of it that way and if in his own life, he makes a separation between his 9-5 job and his art, and if that helps him get out of it.

“Yes and no.” And his answer gives much to reflect on. Traditionally, in simple terms, he thinks of his job as a paycheck so that he can continue living his artistic life. And, luckily, he says, he makes just enough money, and has just enough physical health that he can exist in two spaces.

But his main concern recently has been what he calls an “idea of self-embodied radical resistance” in which he can understand his place within the institution. He doesn’t believe work and art should be seen as two separate spaces, because carrying an energy or beginning to embody and represent something also means having the ability to carry that energy into spaces where it may not be so accepted. So, he doesn’t “hide” himself at work, and that to him is radically changing the nature of what it means to be within that institution.

“And that's me embodying, you know, the confidence, the lack of shame, these kinds of emotional barriers that I've overcome in order to, bring it into the real world. I think one thing that's really interesting in magic rituals is this idea of transcending across thresholds. So, in rituals that involve going to the underworld, so to speak, or going into the dark subconscious realm, the idea is that there's always this crossing of a threshold. I think we need to ask ourselves, especially as artists, who am I in relationship to the institution? And, you know, it's also nice to have healthcare. It's also nice to know that if I get really, really sick, the capitalist machine is gonna get me back into working status. So that's what I mean. I do separate myself between my 9 to 5 and my artist life. But ideally, I would like to be more of a torchbearer in terms of what I bring from either sphere. You know?”

A big thank you to Phillip Melchers for the 45-minute interview of which I managed to share only a tidbit. If you want to see more of his work, check out his instagram @phlipmel. If you want to see more amazing performances and experience what it really feels like to be human, see you at Mezrab!

Text Luca van Opstal

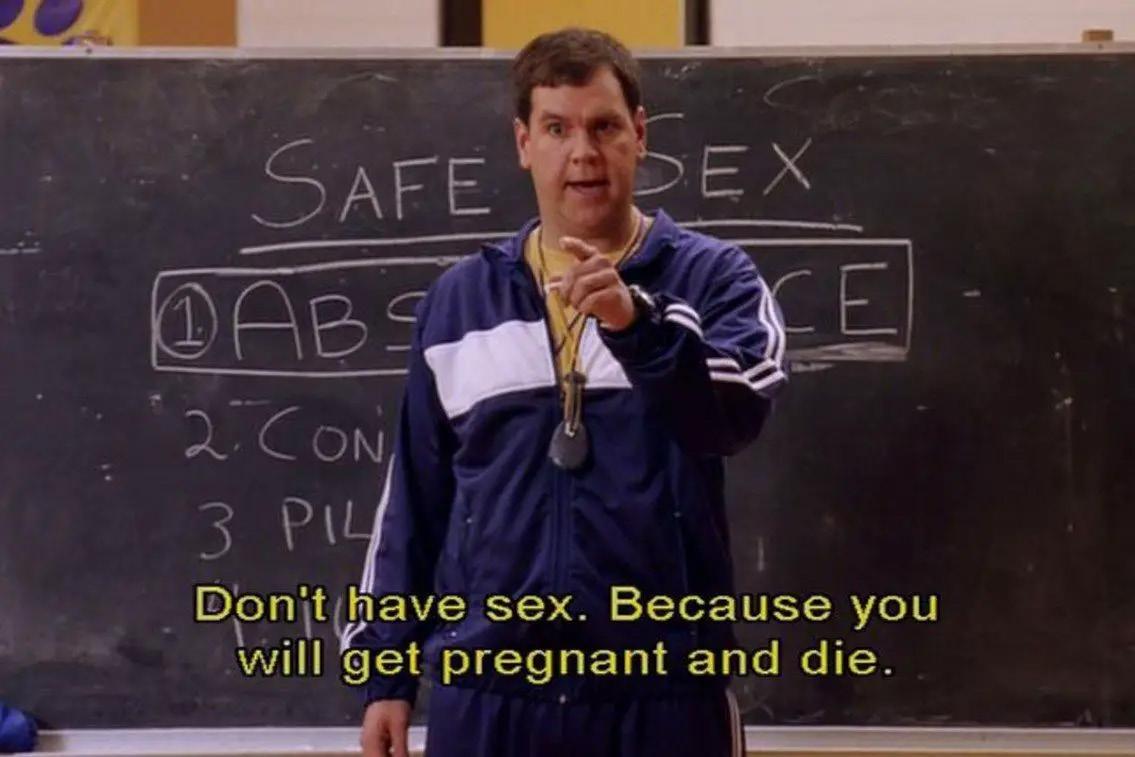

Muffled laughs and hushed whispers as our biology teacher presented us with a somewhat oversized dildo and a couple of condom packets are all that I remember from my sexual education in high school—and when I say all, I mean all. Surely, our curriculum was a bit more extensive than that; yet, when I graduated high school and started feeling the desire to explore my sexuality for the first time, I realised that although I was quite knowledgeable on how to prevent unwanted pregnancies or contracting any STDs (very important too, I will say), I had no clue how sex was supposed to be enjoyed. Feeling too flustered to ask anyone, I resorted to a place I am sure many of us have turned to for our most intimate, uncomfortable questions: internet forums.

I used an anonymous username as, naturally, the thought of my old classmates ever finding out that it was me asking these questions occasionally kept me up at night…The horror! Dozens of strangers advised me on what to do and what absolutely not to do during sex, told me how it would feel “down there,” and even convinced me that after that first time, my life would never be the same again. Supposedly, both my body and my mind would be forever changed, and I would never be able to go back to the person I was before. Based on that last sentence alone, I don’t have to emphasise that some responses were helpful, and others less so. However, those forums did encourage me to think about something that I hadn’t necessarily considered before: namely, how intrinsically personal and ever-changing people’s sexual experiences really are, a notion that I felt was missing in my formal sex education.

As it turns out, I am not the only one who feels that way. In a national survey that was conducted in the Netherlands between 2017 and 2023 ( “Sex Under the Age of 25”), the average grade young people (aged 12-25) assigned to the information on sex that they received in school was an awkward 5.8, using a scale from one to ten. Participants indicated that they specifically would have liked to learn more about topics like sexual harassment and consent, sexual pleasure, and sex in the media, raising questions about whether the current sex education curriculum in the Netherlands is sufficiently based on the actual needs and wants of young people, especially considering the multitude of social developments that they go through as they first begin to navigate their sexuality. The study results from the same survey are clear: no, the current sex education curriculum is not sufficiently based on our needs,

and the strong focus on prevention tends to overlook the conversation on sexual pleasure and other equally important (social) dimensions of sexuality.

Yet, the ambiguous nature of sexuality in itself naturally poses a challenge to its instructive possibilities within formal education. Sexuality is a topic rooted in taboos; in most cultural and social contexts, it is nearly impossible to separate from society’s major social institutions such as religion, the family, and even the state. When we also take cross-cultural variation in terms of norms, values, restrictions and freedoms regarding sex into account, a universally standardised, allencompassing, and “right” sex education curriculum seems near-impossible to establish (and we should probably forfeit the idea of ‘universality’ entirely, as any decent anthropologist would say).

Considering this multiplexity and multiplicity of sexuality, then, perhaps a useful question would be: where should we start?

I would say that it’s the peculiar combination of repressiveness and permissiveness that has sexual education in a chokehold right now. Sex is everywhere – especially with the recent explosive rise of new media—yet it remains a conversational topic that’s only to be addressed behind closed doors. At the same time of my life when I was trying to pull a condom over that dildo in front of me, I was confronted with every flavour of flashy pornography on the internet (curse those terrifying “Linda is only 5 km away from you...” advertisements that would pop up on any sketchy website back then and almost had me desperately tell my dad that someone had doxed us), some of my classmates furiously engaging in “revenge cheating” (guess that’s a thing), and questionable, suggestive billboards next to the highway (the ones with the seductive silhouettes promising married men a “good time”). Already back then, learning about sex as a simple mechanism of reproduction seemed to me largely at odds with what it was that sexuality entailed.

I first approached that question as something that should be considered on some kind of sexual moral compass (I thought: married men, really?), and then increasingly began to wonder how exactly this whole thing was supposed to be fun one day. Although I did not feel that any information was necessarily restricted from me as I was trying to work through

these thoughts—I am now sure my lovely parents would’ve answered any question, but nothing beats a teenager’s sense of shame—the inherent taboo of the topic was socially and culturally omnipresent. I would say that repressiveness, in that sense, should thus not be mistaken with oppression, but in the case of sex education in the Netherlands rather refers to the extent to which talk of sexuality is acceptable for public conversation. Permissiveness would include fostering a safe and encouraging space for these conversations to happen, without fear and without shame.

And what would those conversations ideally be about?

Well, preferably about slightly more than just the flickering projection of the anatomy of the penis on the smartboard in my old biology classroom and the extensive list of diseases in my textbook that I always forgot all the abbreviations for.

The Dutch sexual health agenda, the model that the current sex education curriculum in the Netherlands is essentially based on, would truly benefit from a solid, fresh upgrade. This

would require a critical review of what our needs as young people actually are; needs that may range from learning more about sexual pleasure (spare us youth the internet forums, please!) to emphasising the fact that sexual experiences are inherently personal and individual.

Educational topics related to prevention will always remain relevant and important, but I believe that additional learning goals centred around sexual self-efficacy and sexual selfhood—think of elaborate teachings on matters like sexual self-esteem, sexual justice, and the social and cultural determinants of sexual experiments—would undoubtedly add a new, crucial dimension to any sex education curriculum. After all, school-owned dildos and biology textbooks can only teach us so much. And for goodness’ sake, don’t let the internet fool you either.

Text Daria Nita

Image Helena Peters

Igrew up in the east of France near the Swiss border. When I was 10, my parents sent me to summer camp at a lake in the mountains nearby. I have vague memories of being stuck in a tiny two-people sailboat with two other girls; as we were one too many, we spent the whole session running left to right according to which side of the boat the main sail would swing, to balance the weight out so that we wouldn't tip over. We did some mountain biking, cave exploring, and archery, and there was a big party at the end of the week to which I proudly wore a "I <3 New York" t-shirt. It was the summer before my last year of primary school. I never went back to that camp and didn’t sail again for another decade. Growing up near the Alps means I was roughly a four-hour drive away from the Mediterranean Sea, or a seven-hour drive away from the Atlantic Ocean, and we only went once or twice. However, for months on end, I would dream of water.

This one wave in particular made recurring appearances –different settings, same wave every time. I would be dreaming of anything, a beach day, looking out the window from my childhood home, a hilly landscape, a river… and this same wave would appear. If you have seen Interstellar, it was that type of wave: a colossal, dozens-of-meters-high wave, that seemed like it would swallow up the whole world. You could see it coming from afar, just a small dot on the horizon at first, and then it would advance, slowly, silently, growing taller and taller. The people around me ran away while I stayed right there, staring straight at it. Finally, when it stood just meters away from me, it would suddenly halt; when it got so close that I could almost touch it if I reached my hand out, it would stop. As if were hitting an invisible wall, it would bounce back, and recede immediately, leaving no trace of its passing. I would wake up then, never scared but always slightly concerned, and scribble another line about it in my diary.

I dreamt of this wave for months on end, night after night. Being young and superstitious, I googled every possible meaning without finding any real answers. The only explanation I came up with is that I must be destined for the sea. In the following years, the wave disappeared from my dreams, while my longing grew and grew, and I fulfilled my seafaring wish as best I could. On vacation in Norway, spending a couple of days on the west coast, I tried signing up for surf classes but a huge storm made it impossible to paddle out. On the ferry back to Denmark, I stood outside, hands on the railing, looking at the ripples the boat created in its wake, wondering when I would get to sail again. That summer, I looked up online marine biology classes. Years later, a couple of weeks after moving to Amsterdam, I took a trip to

Zandvoort with a friend, and after walking around the sand dunes we spent some time sitting on the beach, side by side, looking at the waves in silence.

I am 21 now. I only got to sail again this October, a little over a decade later. Out of pure coincidence, I met someone at a party with a sailing license who, in a drunken state, offered to take me with him sometime. The next morning, sobered up and determined to make it happen, I texted him about it and we ended up going the following Thursday. I had spent the whole week talking my friends’ ears off about it, and by the time Thursday rolled around I was terrified—but still dead set on going.

I had no idea what to expect and ended up wearing the (nonmandatory) life jacket because my mom had voiced some (valid) concerns. We were out on the Gaasperplas lake for a little over two hours and this is how it went. We spent the first ten minutes pulling out of the tiny harbour and putting up the sails. I was told to sit down and hold on tight, which is what I did, while the two experienced sailors I was with set up everything. It was much more technical than what I remembered – or maybe it had to do with the fact that this boat was five times the size of the one I had sailed in when I was 10. Maybe. That Thursday was a very sunny and calm day, so we spent the first half of the ride zigzagging up the lake, trying to catch some wind. I learned that a rudder at the back of the boat is used for steering and that the wind does not have to come from behind for the boat to go forward: the miracles of engineering! I learned that if the wind changes direction, so does the head sail, so we need to free the rope keeping it tight on the left and tighten up the one on the right instead, or vice-versa. And so does the main sail, so we need to duck and change sides, something I remembered from my fond memories of summer camp. After an hour of observing, I got to sit at the back and steer for a little bit—and I did it very poorly but it made me very happy.

I quickly learned that sailor number one, the one who I had met at the party and who invited me on this outing, liked going fast, and enjoyed catching the wind in a way that made the boat dramatically tilt one way or the other, closer to the water. Sailor number two, his roommate, was less of a fan of speed and, when in charge of steering, would calmly sail from one side of the lake to the other. Number two steered most of the time, and we got to relax in the sun for another hour. By the end of hour two, on our way back to the harbour, the wind picked up. Catching a good blast, sailor one, back in command, tightened the main sail and the boat began to tilt to the right, more and more and more, until the right side

of the hull (usually perpendicular to the ground) was fully touching the water. I was sitting on the floor, back to holding on for dear life on the railing behind me, the boat narrow enough that if I extended my legs in front of me I could prop my feet up on the other side. Picture this scene. We were heeling at a 15-degree angle (which felt like 40) and I was facing the water, looking straight down at the waves, feeling the adrenaline build up. After two hours of sailing, I realised that tilting does not signify that we are tipping over, and I started to enjoy the speed. So, I was sitting there, holding on for dear life as the boat sailed faster and faster and faster… and then my mind went completely blank. And I felt a sense of freedom I had not felt in years. That child-like freedom of being high up a rock-climbing wall and jumping off, trusting that the person holding the rope would stop my fall. Diving off the 3-meter platform at the public pool knowing that the fear was temporary because the water below would give me immediate release. That one summer I went horse riding and they made us close our eyes and drop our reins, and we were galloping blind and out of control but so, so free. After a couple of seconds that felt like minutes, our captain loosened his grip on the main sail, and the boat slowed down gradually,

and we were back in the harbour. We went back to their place and had well-deserved vanilla pudding.

That Thursday night, back home, when I closed my eyes to sleep, I could feel myself rocking left to right as if my bed had drifted off to sea and was rolling on imaginary waves. At the bottom of this page is a picture of me on a large sightseeing sailing boat, off the coast of Tenerife. Being 3 years old, I got bored waiting for the dolphins to show up and fell asleep face down on a bench. Sometimes I like to think that this is where it all started: a very young me, fast asleep, being rocked by the waves. Maybe it imprinted something deep down in my subconscious. Maybe this is the feeling I have been chasing all these years, and I periodically awaken it when I am scared of doing something but end up doing it anyway. I guess the point of this essay is: hassle strangers until they take you sailing! People will only take your dreams as seriously as you take them. Growing up inland does not mean it is silly to long for bodies of water.

Text Eduardo Di Paolo

Image Carme Ferrando Soriano

Returning to Amsterdam this late summer, I was immediately intrigued by the three letters in red spray paint adorning every corner of my metro stop: ADF. After seeing it there in Zuid Oost for the first time, I began noticing the ubiquitous insignia across the whole city. I knew that I had to uncover this secret: the three letters stand for Amsterdam Defence Force

The group’s social media presence is quite robust—circa 4,000 followers on Instagram and 1,500 likes on Facebook—making it quite easy to enter this enticing rabbit hole, one which lured me on with one ambiguous post with its barely intelligible dog whistle after another. After hours of gathering intel, the most persistent feeling I had to deal with was incompleteness: I felt like my mental categories were altogether insufficient to understand. Further, I had this incessant vision that I was missing something, either between the lines or behind a veil.

Let me give you a gist of their introductory mission statement:

"ADF guards over the culture of Mokum. We give a signal to everything and everyone who comes here to live, work or have fun. Amsterdam will remain Amsterdam [...]" .

Following these precepts, expressed through strenuous repetition, I think the words that describe them most are radically (and rebelliously) conservative. Their declared aim is to preserve Amsterdam as they imagine it, and this message is starkly sustained by a continuous flow of social media posts and merch with their slogans on it. After a few seconds, any observer scrolling through their pages would read "Alle yuppen De Pijp Uit" (‘All young urban professionals out of De Pijp’, a common refrain), "Amsterdam voor Amsterdammers", and "Amsterdam is geen Nederland". Noticeably, these black shirts and hoodies are mainly worn either by men aged roughly between 35 and 60, often cultivating a 'thug' aesthetic— covering their face or censoring it with skull emojis or tv static—or tackily placed right above women's butts. All of their messaging points towards a civically engaged selective xenophobia: while people are not rejected for the mere fact of having another national heritage (Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese flags appear and are even celebrated from time to time), it is clear that the persona of the outsider is certainly non grata. There is one post, which gets routinely reposted and receives above-average interactions, quite explicitly encapsulating this feeling:

“You can come here to live. You can come here to work. You can come here to drink. But you will never become an Amsterdammer XXX.”

The way race is addressed remains quite peculiar; a pseudomanifesto published in 2020, amid their protest against a

restrictive and paternalizing government of mayor Femke Halsema and the left, reads:

“Amsterdam has the most cultures per square meter. Adapt yourself. We are not against people of a skin color other than the Aryan race. We are not against refugees. We are not right or left. We fight for the preservation of Amsterdam culture.”

It seems that their position is markedly anti-state power and anti-politics as a realm and as an omnipresent malleating force. As belligerent agents of the state and their most recognizable representatives, the police have often been targets of scorn from the ADF. To fully understand this position, I am now introducing another crucial aspect of the identity of the group: they are part of the Ajax ultras. Amsterdamse identity seems intertwined with being an ‘Ajacied’, encapsulated by their football-oriented slogan: “One goal, one city, one club, no yups”. A striking aspect appears in their symbology as Ajax fans: identification with Jewish identity. The fans of the team have for decades been identified as joden due to the notorious presence of the people in the capital before World War II, while no real link was ever in place with the team or its fans. The ultras of rival teams instrumentalized this historical and demographic memory to deplorably insult Ajax fans by, for instance, hissing to emulate gas chambers or showing the Roman salute towards the opposition stand. In turn, this caused the Amsterdam football followers to create a strong bond with the Jewish identity and assimilate Jewish and Israeli identity into their fandom. This is displayed time and time again on the ADF pages. As hard as I scoured, though, I could not find any reference to the current Israeli attacks in the Middle East, which I believe suggests that this identification is profoundly idealised and for the most part disconnected from the contemporary status quo.

Further, it seems that their antagonism towards the police has been polarized via frequent clashes of the hooligan wings of Ajax. Martyrisation of subjects of police violence happens often and, most recently, after the declaration of a police strike during the biggest games of the season, and its subsequent postponement, incitement against the police and their headquarters was posted.

I just cannot seem to be satisfied with where I have gotten so far. Even though every single piece of digital paraphernalia added something to this enthralling picture, something still appears off to me about my understanding of the ADF. Something is missing. Ultimately, I think that vacant piece is materiality: e-research can only bring one this far without seeing and feeling the pivotal salience of bodies in the observation of popular movements, especially when corporal congregation is crucial for the people themselves. So keep an eye out around the ArenA or the three graffitied letters.

Text & Image Helena Peters

One of my friends told me about an acquaintance named Embla, who started going to church out of the blue. I am born and raised atheist so I have little to no experience with church in my 22 years of life. That is why I was very intrigued about her reasoning for going to church. When I asked my friend why Embla started going to mass, she explained that Embla just wanted to understand. To understand a world you’re not fully a part of made total sense to me as an Anthropology student and I wanted to know more. My starting point was a disagreement with Christian beliefs and a sceptical view of its ideals. This had been built up by my parents and German grandparents who always disagreed with the Church and all religious beliefs. Christian ideals seemed very unattainable to me, their beliefs extremely distant. What I knew was what I learned in history lessons: religion has been more often than not a fundamental factor in starting wars. This did not set me off on a good start in trying to understand Embla.

On a Sunday morning in late October at 9:30, I decided to join a Mass at the Vondelkerk. I did this before having a conversation with Embla. I entered the building and was greeted by a person with a big smile. I kept on going in and grabbed a pamphlet that was lying on a table that said:

“Welkom”.

When I flipped it open it said:

“In a city set on finding liberty, we believe that true liberty comes in obedience to Jesus Christ. This is life, life to the full.”

As a starting-out anthropologist, my goal was to stay neutral and to understand this culture from within the group. As my lecturer Mattijs van de Port said, “Give yourself over.” I wanted to put my pre-constructed opinions and understandings of religion and Christianity away for the morning and truly watch and participate. And so I did.

It felt odd at first, as I am very distant from this part of the world. The only reason I had been to churches in the past was to see artwork, typically ignoring their inner happenings. Now I wanted to immerse myself in the singing, teachings and collectiveness of the institution. I immediately understood what feeling this church could give to the people. As I was singing songs with the group, individuals became a collective. It gave me a strange comfort, while I also felt like a traitor for my atheism. The intense emotions people felt in this room while praising God took me by surprise, emotions visible in their facial expressions and body movements. Some of the churchgoers looked like they were in pain, scrunching their faces and coddling themselves with their arms. Some of them looked intensely happy, raising their eyebrows while closing their eyes. Some ecstatically raised their hands.

I was listening to music with my roommate later that night and it hit me: She started making movements similar to those I saw in church. Her expressions looked similar and she was raising her hands. She was in the moment, cohesively connected with the music and with me. We were experiencing something as a togetherness – it felt as if all participants were committed to this church and thus made it come together as a working collectiveness. Like the hands of many interlocking with one another. Yet it seemed everyone was individually having a different connection to this effervescence.

From that experience, my atheism was underlined for me. Based on what I saw, I could understand how churchgoers have such a strong connection to religion and their faith. It gives a certain comfort in knowing that you are not alone. It makes you feel like you are a part of something bigger and important. Yet, I still have a strong disbelief in the beyond of religious beliefs. The feeling that is so prevalent in their lives on a Sunday morning mass just shines for me in different ways - like sitting with my roommate and listening to music. After this experience, I decided to sit down with Embla and talk to her about her experiences in church and found out that she too had a similar understanding. The feeling of acceptance that she receives in the church helps her as a reassurance in life and for her Self. Having a relationship with a religion from her past gave her a newfound comfort in her identity and an answer to her search for purpose in life.

Because the community was the main thing that struck me as an “outsider”, I asked Embla if she felt that the experience in church was more of an individual experience or communal feeling, and Embla replied: “It's kinda both – I feel like it works together because you go there and you feel the community and you feel better about it, so you go there to build your own religion but still, it works that way because we are there as a group.”

What Embla is experiencing is a collective effervescence within this church. Not only is the church supposedly open to any religion but also to everyone. It’s easy to be cornered by the question of belonging and to have an endless search for purpose in our world. Additionally, for Embla this connects to a prior link to religion in her past as a young person. This shows that religion truly has an individual string to every single person. The connection you feel as a religious person has the base within this community, as a collective. The personal connection is very flexible within your own personal limits. I would like to underline that this text is in no way a love letter for Christianity; but rather a small observation of a community and religion. I still am an atheist and will remain as one, Nevertheless, I find religion and its inner-workings very interesting. It was a fun experiment on ethnographic research.

“Like the hands of many interlocking with one another”

Text & Image Carme Ferrando Soriano

Ithink I should begin by admitting that I have never written a proper media review before and my criteria for music are often limited to ‘songs I love’ and ‘songs I don’t love as much’.

I am decently capable of identifying musical instruments and although it is quite hard for me to differentiate between music genres, I am familiar with an acceptable amount of them. What I am trying to say is that I am in no shape or form a music expert. The only reason I feel qualified enough to even attempt writing about music is because when I like a song, I like it deeply. I recite the lyrics with great conviction, memorise all the quirks of the instrumental, play it over and over again, and share it with my loved ones. In this article, I am going to tell you about one of my deeply loved songs, why it is so dear to me, and why I believe it could become dear to you, too. Let me introduce you to ‘Bodys’ by Car Seat Headrest, a 7-minute-long powerful indie rock track.

The first time I heard this song was in the kitchen of a hostel that was located in the heart of a big, big city. A conglomeration of luck and common curiosity had brought me and a bunch of people my age to a place that, for the few days we spent there, felt magical. I was seventeen, in a city that was not mine, surrounded by a swarm of voices, in a kitchen that was so small it could barely contain all the people to whom the voices belonged. And yet we all fit, sharing the warmth of the last weeks of summer, feeling it slide down our skin. It seemed to be making us softer, transforming our flesh into clay, so whenever we hugged or touched we were unintentionally shaping each other, leaving dents in each other’s bodies; little dents which, at that time, felt perennial. The murmur of dozens of stories being told simultaneously was suddenly interrupted by the start of a song and the enthusiastic dancing of some of the people there. You’ve guessed it - it was “Bodys”.

I watched them jump as they sang to each other, dancing so freely and yet so attentively, aware of one another’s movements. Their unintentional performance was symbiotic chaos. The song was upbeat and noisy, a noise that materialised in the way their arms were turning into squiggly lines and their upper body followed the guidance of their legs. I smiled as I witnessed their dance and realised I had never allowed my then-insecure and shy body to move like that. When I was invited to dance, I confessed my cluelessness – “How do you dance like that?” , I asked. And as they guided me and held my hands, I followed.

It was not until months later that I rediscovered the song and thought back to that moment, to that instant that I remembered and sweet memory that I carried with me so dearly; to the grandiosity of every feeling, every touch; to how they all got magnified and celebrated between those walls and newly found friends. It is no surprise, then, that now I cannot think of this song as anything other than a love song dedicated to friendship and the awkwardness that comes with sharing the experience of youth with others. I must confess I have a tendency to over-romanticise fond memories, and the short story I’ve just told you is definitely a result of this habit of mine, especially considering that since I was 17 when I experienced it. Regardless, I stand my ground that this song is the best for i-want-to-dance-with-my-friends-forever parties or solitary dance sessions.

I invite you to listen along to ‘Bodys’ as you read this article and accompany me in the journey that this song entails. Let the sound of distorted guitars, gritty sampled drum beats, and mismatched vocals lead the way. Here we go.

The 53 seconds of instrumental that precede the beginning of the lyrics inevitably get your body moving and will urge you to rush from the bathroom or the balcony to wherever the first notes of the song might be playing from.

That’s not what I meant to say at all I mean, I’m sick of meaning I just wanna hold you

This urge for touch and innocent intimacy sets the tone for the message of the rest of the song: in case of uncertainty and insecurity, let’s dance together, let’s hold each other . The rest of the verses also have a conversational feeling to them, with most of the lines being sung in a speech-like manner, which allows the song to be enacted through one’s own gestures and facial expressions:

I would speak to you in song

But you can’t sing

As far as I’m aware

Though everyone can sing

As you are well aware

As the instrumental becomes increasingly layered and noisy and the beat accelerates, the chorus, which I would say is my favourite bit of the song, approaches. With a clumsiness that might be caused by butterflies as well as various substances, the singer stammers:

Those are… you’ve got some nice shoulders

I’d like to put my hands around them

I’d like to put my hands around them!!!!!!

What a genius lyric! One aspect of the song that makes it so special and unique is the way it refers to bodies. I’ve always thought that the majority of songs that are made to dance to talk about bodies in an objectifying and purely sexual manner that often feels exclusionary - it is as if only bodies that fit into an established norm deserve to experience and relate to the fun, freedom, or even sensuality that come from dancing. In my opinion, “Bodys” breaks with that. By complimenting the addressee’s shoulders rather than other body parts that are associated with dominant beauty standards, the singer celebrates bodies and touch in an emancipatory and tender way. Shoulder holding becomes a delicate yet oh-so-powerful declaration of closeness, even if temporary, and shoulders themselves a symbol of the beauty of inhabiting a body. When I sing these lyrics to and with my friends, and they put their arms around my shoulders, I feel the gentle weight of their love upon them.

Friendship is continuously celebrated in this ode to togetherness, which becomes obvious in the third verse. After singing about stolen alcohol and the angels and devils on people’s shoulders who are, in fact, ‘just two normal people’, the singer goes ‘oooh’ and then repeatedly gives a shoutout to the people he’s partying with:

These are the people that I get drunk with