Moonlight

Peter Halstead

My Beethoven Summer I

It all started with Beethoven.

I played almost all of his sonatas by the time I was nine. My grandfather had built us a playroom with bookshelves for our one book, room for a piano, a couch, and an easy chair. The chair was right next to the piano. My father would sit in that chair while I pounded octaves and chords. I don’t know if he read or just sat there. A Norman Rockwell portrait of family life. He sat there for over a year. But one day I came home to find my Chickering turned into a desk, with a discolored ivory top.

I had to sneak off to our neighbor’s house. They had a piano, and I was crazy to play it. Joe and Ellie loved to have me there.

One day my father burst in. I was sitting as usual at the piano. He grabbed me by the ear and began to drag me off the bench.

“But, George,” Ellie protested, “we came home to music.”

My father became enraged. “You have no right to play their radio!” he shouted. “No,” Joe said, “he was playing the piano.”

My father was baffled. I was forbidden to go to their house ever again. “They’re Jewish. They live in filth.”

“Their house is cleaner than ours, Father.”

The only difference in our houses was that they had books. We did have that one book, a photo book of World War II. My father was still in the Army, emotionally, as many men were in that era.

The world was unstable in the summer of 1964. There were revolutions throughout the Middle East; assassination was in the air. Kennedy had been shot in 1963.

My father had sent me to boarding school after my mother died of a brain tumor. When I came home from school, he sat me down and had a woman describe to me the world tour he had planned for the

summer. I would travel to places that, in retrospect, were hotbeds of revolution. I would travel alone. It was a way of getting rid of me for the summer. Maybe for longer.

Ceylon was on the road to independence. Singapore was torn between the Chinese and the Malaysians. My hotel in Ceylon was invaded by Tamil Tigers, revolutionaries who took the guests prisoners. I had met the ambassador there a few days before. I snuck down to the kitchen and phoned him, then ducked out the back into the jungle, where, an hour later, a jeep with Green Berets drove me in the early dawn to a helicopter which flew me to safety, I don’t remember where, maybe it was the airport.

In Cairo there was food poisoning, which I had gotten in Thailand. I have a photo of the 10 medicines I was taking to recover.

A week later, I was flown by commandos and a helicopter to Kuala Lumpur out of Singapore, which at that time was a hut city built on sticks over a swamp. I had a

Chiang Mai jacket and a djellaba which I had gotten in Thailand and Cairo; I felt sufficiently disguised to sneak out at night and watch the riots. People were dying in the dark streets, hit by bricks, shot.

I remember opening the hotel door the next morning at 5 AM to find a gang of tall guys in camouflage with bayonets on their rifles. “You have to go.” Another jeep ride to a helicopter. I never said no.

In Islamabad, another helicopter rescue. In Johor Bahru a fanatic with a machete tried to cut my hand off in a souk. And an ensuing chase. I played Beethoven in an embassy in Kathmandu, and the roof collapsed shortly afterwards, destroying much of the building.

It wasn’t that I left a slew of messes behind me. The messes were already there.

I never questioned these consistent evacuations from my world tour. I had never traveled before, and assumed this was the way the world was.

My goal for that summer was Pontrhydyfen in Wales, where I met Graham Jenkins, who was the manager of the Port Talbot market. His brother Richie had been adopted by a theater director called Philip Burton and changed his name to Richard Burton. I admired Richie’s recordings of poetry: Donne, Coleridge,

Dylan Thomas. There were the Jenkinses: Ifor, Verdun, and Cis, and the Owenses: Hilda, Sian, and Megan. We went to pubs with Elizabeth Taylor, who dressed as a man. Women weren’t allowed in pubs. There was a lot of beer and pinball.

We drove through the gorgeous Brecon Beacons hills up to London to see Laurence Harvey in Camelot. We had a box in the first tier of the theater, and Richie and Graham and even I sang along. Who doesn’t love Camelot? After a while everyone in the audience began watching us, not Laurence Harvey. We laughed over it later backstage with Harvey, Laurence Olivier, and, inexplicably, Phil Silvers. Phil Silvers had been in a play written by Ira Levin, who was my neighbor Ellie’s brother. The books in her house were by him.

I had canceled my grand tour. My grandfather had given me a credit card before I left home, so I could afford to stay at Graham’s house and hang out with a bunch of teenage Teddy Boys in Margam for the rest of the summer.

My father seemed angry when he met me at the airport. He had brought scissors, and asked for my credit card, which he cut to bits at the bottom of the plane stairs.

I saw the summer of ’64 as an overreaction to my Beethoven. It was Beethoven who was the catalyst for the world tour, who launched me into all that revolution.

My father kept me away from the piano until I went to college, where I would walk across the street to Barnard Hall and play an upright in the basement every morning at 6. Schumann’s piano concerto saved my life. I also got access to a wonderfully responsive concert grand in my dorm, which Manny Ax, who was a student there, also played. I think we were the only two people who ever played it. It disappeared when the dorm was torn down. By that time I was 20. I had survived Beethoven.

W

My Beethoven Summer II

hen Josephine, Countess von Brunsvik, was 20, she fell in love at first sight with her piano teacher, who happened to be Beethoven. He was 29. They were planning their future together just weeks after they met.

Two months later her mother forced her into a miserable marriage to block their elopement.

Their love continued, despite the countess’s two forced marriages, for another 14 years.

Beethoven wrote the Moonlight Sonata in her family castle south of Buda in Hungary two years after they met. The Brunsvik castle was set on 8,000 acres.

It had been built on a swamp and was consequently surrounded by many lakes and streams. There was an island in the middle of one of the lakes where Beethoven spent time with Josephine. The Moonlight Sonata describes waves lapping at night on that island.

When the countess’s husband died suddenly, she and Beethoven planned to elope again but were prevented by her second forced, tragic marriage.

That first spring when they met, the Moonlight spring, was more significant in retrospect than anyone could have imagined. It turned out to be Beethoven’s last chance for happiness. Neither he nor the countess knew it at the time. You can hear their love evolving and then disintegrating in the score: the romantic night of first love on the castle lake, then the drawing room calm before the storm, and finally the frenzied Gothic storm played out on the Hungarian Sea: Josephine lost to

Beethoven through her forced marriage. The patterns of our lives are never visible while we’re living them, as my Beethoven summer came into focus only years later. Only in hindsight do we realize what it all means. Only when we put together the devastation caused by her mother’s desperate meddling do we realize what a prophetic interlude the Moonlight was for the countess, for Beethoven, for their free-spirited obsession, the wayward passion that made the countess an outcast.

Shamed, abandoned, and sick, the countess gave birth to her eighth child in a hut. Beethoven went on to immortality; the countess to tragedy. Their paths never crossed again.

Passion breaking into dark fragments in the Hungarian night. The beginning and end of love in one clairvoyant, tragic, triumphant sonata.

BOOK ONE

The Immortal Beloved

For 200 years historians have traded discoveries over the possible identity of the person whom the composer Ludwig van Beethoven called his “immortal beloved.” Dozens of women and a few men have been suggested. Finally, only 10 years ago, definitive proofs surfaced. They have changed how we see and hear everything Beethoven wrote at that time, especially the Moonlight Sonata of 1801–02.

The following information represents the smallest fraction of what scholars have amassed about Josephine von Brunsvik, especially in the last decade.

2. The Way Up Is the Way Down

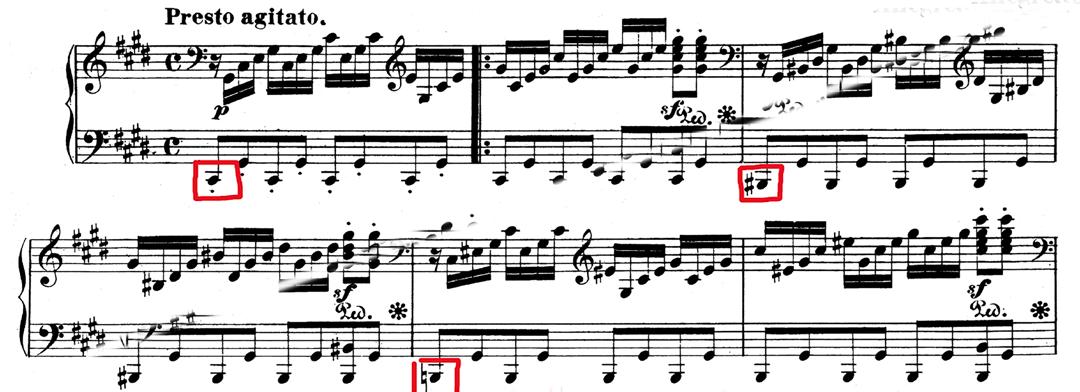

Many Beethoven sonatas are constructed from their first few measures.

Beethoven’s sonatas also end as they begin. The ending is contained in the beginning.

In fact, in the Moonlight Sonata, every part of every movement comes from the first few measures of the beginning.

Our time in the sandbox sometimes sets the stage for our behavior in grade school, in college, in our jobs, in our marriages. Einstein’s general theory of relativity theorizes that time is directionless. You can go any direction in it. Time is a dimension, just like space. Which is why, if we could change dimensions, we might jump to our lives 400 years earlier, or a thousand years later.

Max Planck’s quantum mechanics proposes that there was a pre-existing energy grid underlaying the universe from before the beginning of what we call time. This grid allows matter to bypass time. It allows energy to cross the universe instantly. The speed of light no longer becomes a measure of time or distance, as matter can be transformed into another dimension, beyond the concerns of our own spatial constraints. It is alchemy, not with lead and gold, but with time itself.

Thoreau said that man was the only animal who tried to divide time artificially into parts, into hours and minutes. In his poem “The Dry Salvages,” T.S. Eliot quotes Heraclitus (who wrote around 500 BC, but whose thoughts anticipate quantum theory):

And the way up is the way down, the way forward is the way back.

Eliot also wrote in “East Coker”:

In my beginning is my end….

And in “Little Gidding”:

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from…

Beethoven demonstrates in the Moonlight Sonata how his descending theme can reverse itself and, with the same notes, become its inverse (an ascending theme)—a mirror image, as Rorschach blots or butterfly wings duplicate themselves.

This is what Noam Chomsky called negative syntax. Bernstein applied it to music in his Norton Lectures. Something is said, and then contradicted. If it were a mathematical equation, the result would be zero. But in language, something has been said. Meaning remains behind. When a theme reverses in music, the musician can see the pattern reversed. But it’s harder for the listener to spot; it’s a subliminal trick.

Beethoven’s “contrary motion” couplets move up, and then down. They cancel each other out. But they are insights from Heraclitus in 500 BC: time can go in both directions and at the end still convey triumph, passion, salvation.

3. Three Levels

There are three levels of reality in Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata:

In the first movement, the triplet theme:

with the bucolic ripples of true love and its accompanying melancholy, with all the time in the world, even if ominously in a minor key.

In the second movement, the descending theme in three flavors:

as the mood transitions from idyllic to thoughtful, unaware of the coming storm.

In the third movement, the arpeggio theme:

and in the middle part, the mirror theme:

The counterpoint to love: a composer can’t marry a countess.

4. Masks

All three movements share the same theme, masked by a minor key changing to a major key, and a three-note motif in the first movement:

expanding to a four-note motif in the third movement:

In the first movement, the theme is introduced, perversely, in the left hand by slow octaves: (Usually the theme is in the right hand.)

Moonlight Sonata

5. Misconceptions

We all have picture in our minds of Beethoven as an old, deaf man—certainly not an attractive date. But in his youth he was handsome, well-dressed, and even dashing. He had the advantage of genius; every young woman he taught was in love with him. He was a dangerous commoner, off limits, and thus exciting to overly protected debutantes. He was Elvis, James Dean, Bobby Darin.

Although the establishment couldn’t understand at the time that music could grow beyond Haydn and Mozart, young people were excited by the passion evident in Beethoven’s groundbreaking momentum.

Beethoven taught mainly young, pretty noblewomen and considered himself their equal. Genius was even better than a noble birth. This was a romantic model doomed to collide with the values of the ruling class.

Beethoven said to his friend Prince Lichnowsky: “There will be and there have been thousands of princes. However, there is only one Beethoven.” The educated, articulate, talented women he admired were always aristocrats, and off limits.

Beethoven saw through the outmoded values of society, as did the revolutionaries who stormed the barricades only a short while after his death. But we know that even today many cultures still forbid young people from marrying outside of

their religion, or beneath their parents’ economic expectations.

In Josephine Beethoven found a young woman who shared his rebellious nature, who dared to love him back. Despite her intimations of independence, though, she was trapped by her sense of duty to her mother and allowed herself to be manipulated by family, by society, and by both her husbands, by a seemingly moral and ethical correctness which in the end erased her inheritance and left her penniless and loveless.

Beethoven lost the one woman who loved him back. He never saw her again. Although he would go on to have other affairs, they were no solution to his loneliness. They weren’t true love.

Beethoven in 1802 at 32

von Brunsvik in 1802 at 23

Josephine

6. The Debonair Beethoven

Unlike the common vision we have inherited of Beethoven, he wasn’t a hermit. He was highly sought in society. He taught the beautiful daughters of the aristocracy. He had affairs with most of his female students. He was infatuated with all of them, but he despaired of ever finding real love after he lost his Immortal Beloved, Josephine Brunsvik.

When Josephine married in 1799, Beethoven was in despair. Revolutions, and depressions, are caused by rising expectations dashed. His chances seemed dim by October 1802, when he wrote what is now called the Heiligenstadt Testament, where he revealed the depths of his loneliness, even though he was in the charming alpine village of

Heiligenstadt, where he had passed many happy summers in the woods and in the taverns.

But Beethoven and Josephine were soulmates, and she continued taking lessons from him and performing his music throughout her two marriages. He wrote to her in early 1805:

…[Y]ou—the only beloved—why is there no language expressing what is more than respect—far more than everything—which we can name— oh, who can call you, and not feel no matter how much he talks about you—that all this can hardly reach you—only in music—O, I am not too

proud when I believe that notes are more willing to me than words—you, you, my everything, my happiness— Oh no—not even in my musical notes can I express it, even though nature gifted me with some talents in this respect, it is still too little for you. Silently may my poor heart beat— that is all I can do. For you—always for you—only you—forever you—to my grave only you—My solace—my everything, oh Lord watch over you—Bless your days—send all hardship to me not to you—might He strengthen you, bless you, console you—in this wretched yet blissful existence of mortal men—would you not exist, who chained me to life again, even without this you would be my everything.

Josephine always loved Beethoven despite never being able to marry him. Between

her first and second marriage, a count was briefly infatuated with her, and she reassured Beethoven in 1806:

“Believe me, my dear good Beethoven, that I am much more, much more suffering than you…much more! —If you value my life, then do act with greater protection— And above all—do not have any doubts about me… This suspicion that you so often, so insultingly expressed towards me,

that is what hurts me beyond all expression—It is far from me. I hate these low, very low advantages of my sex! —They are far below me —And I certainly do not need them! Coquetry and childish vanity are far from me—as my soul is far superior… Only faith in your inner value made me love you… Always bear in mind that you gave your goodwill, your friendship to a creature—that certainly is quite worthy of you....”

These are the small jealousies that lovers have toward each other, kept apart by family and society.

7. Origins

The Moonlight Sonata is the story of great love and great tragedy. Beethoven’s greatest love died unloved, without Beethoven, in poverty. It’s as if the story were written by a poet.

Josephine’s mother, Anna Brunsvik, was a social climber. Although she was a fixture at Maria Theresa’s court, Anna felt she would be enhanced by an aristocratic son-in-law.

The Hungarian Brunsviks weren’t as wealthy as their distant cousins the Austrian Braunschweigs. So when it came to husbands, all the Brunsviks could conjure up was the bottom of the barrel. Conmen, the kind out of Molière and Rossini and Donizetti, totally insecure about their young wives, and with good reason. Their loves always ended in divorce and ruin.

The lovely and talented daughters of Anna Brunsvik could have done better.

Two of them had a good chance of marrying Beethoven. Although it was Josephine, the young, pretty one, who adored Beethoven, and he, her.

The one reason we remember the Brunsviks today is that Beethoven loved Josephine, his Immortal Beloved. Not because of whom Josephine married. The true love that Anna denied her daughter was ironically the very immortality that Anna sought.

The Moonlight nickname came from a critic 23 years after Beethoven composed the sonata. Beethoven never heard the name. He had been dead five years at that point. He called it simply “sort of a fantasy”—quasi una fantasia. Another critic said it was like moonlight on Lake Lucerne, which Beethoven had never visited.

It took historians 200 years to figure out the true story.

Beethoven wasn’t a lone genius raging against the moon in poverty. He was a successful, prosperous genius who was infatuated with every young woman he taught; often they reciprocated.

8. Josephine

Only recently have we discovered Therese’s diary. Therese, Josephine’s sister, had written: Why did not my sister Josephine… take him as her husband? Josephine’s soul-mate! They were born for each other. She would have been happier with him than with Stackelberg. Maternal affection made her forgo her own happiness. What wouldn’t she have made out of this hero!

Josephine lived in a fairytale castle half an hour south of Budapest, whose wild, English-style gardens are some of the most beautiful in Hungary.

Beethoven must have seen the castle at Martonsvásár as an enchanted oasis initially bound up with an optimistic future for himself and Josephine, although the

honeymoon aspect later wore thin under Anna’s incessant hindrances.

Later in 1805, when Napoleon entered Vienna, the Viennese aristocracy, and Beethoven with it, decamped for Hungary. Hungary was a refuge from

war, a paradise where art distracted the elegant refugees from their plight. It was a vast park of grasslands, forests, and meadows, an escape from the pressures of performing and socializing for exhausted artists, an idyll in a countryside lush with deer, bear, bison, chamois, reindeer. Farther west was Transylvania, home of wolves and vampires.

So Josephine and her utopia offered Beethoven a calm center for his composing. He wrote three major sonatas in her castle. Despite Hungary’s dubious repute, its sudden morphing into a sanctuary changed the Austro-Hungarian rapport into mutual admiration.

Beethoven had called Josephine his “only beloved,” and said “there is no language” to express his feelings, “only music.” He called her his everything, his happiness, and exclaimed that his heart would beat forever for her, to his grave.

In July 1799, only two months after falling in love with Beethoven, Josephine married a man she didn’t love. She was 20. The few days she spent with Beethoven cemented a love that lasted for 17 years.

She couldn’t marry a pianist and a commoner because her mother was a social climber, desperate for her daughters to marry titles. Anna threw Josephine into a marriage for money, which the groom didn’t have; he, in turn, had married

Josephine for her dowry, which the bride never got during her first marriage.

Straight out of Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend.

Josephine was in love only with Beethoven during both her marriages. They exchanged some 27 letters, many of which were discovered only recently. He called her his angel, his happiness, his solace, his everything. “Forever thine, forever mine, forever ours.”

He finished the Appassionata Sonata in her castle, and dedicated it to her brother. He dedicated his next sonata, No. 24, to her sister.

had three illegitimate children, lived under an assumed name, and was 30 years older than Josephine. He kept her locked up until he died of pneumonia, four years after they married. All 11 of his children came to his burial in the Schubertpark in Vienna.

Josephine’s first husband, Count Joseph Deym, pretended to have wealth so he could get his hands on her dowry. When Anna discovered the truth, she tried to have the marriage annulled. Deym was the proprietor of a failing wax museum,

At that point, Josephine wanted to marry Beethoven, but because he was a commoner, she would have forfeited her three children with Deym. As it turned out, she lost them anyway when her second

husband, a baron, kidnapped them and raised them in social isolation in Tartu. The baron believed disobedient children should be tied to their beds.

Baron Christoph von Stackelberg bullied Josephine into marriage. She didn’t love him. There were lawsuits, brutality, drinking, family disapproval, a lover, financial ruin.

Stackelberg had spent his entire inheritance and was always without funds. He used Josephine’s entire inheritance to buy a castle they couldn’t afford. Eventually the owner demanded it back and sued Christoph. Josephine’s last bit of independence disappeared with her dowry. She was thrown into poverty by her mother’s greed.

Anna mistook titles for nobility and pomposity for competence. In time, Anna saw through Stackelberg and came to despise him.

Josephine continued performing Beethoven’s music publicly throughout her life, to great acclaim.

Beethoven, of the beet garden, the beet hoven, descendant of dirt farmers, saved everything he earned. The Brunsviks later lost all their money and had to give up the castle. It went through various owners and eventually became a center for agricultural research. It went back to beets.

Because of Beethoven, it is now solvent.

Beethoven’s music has been played in the gardens there for the last 60 years. The improvident Brunsviks are remembered only because their daughter once loved a provident commoner.

When he died, Beethoven left his estate to his nephew Karl, who, because of it, had no need to work. Beethoven’s estate was only half as large as Haydn’s, and a third as large as Salieri’s, but it was in the top 5% of everyone living in Vienna at the time. Despite periods of insolvency earlier in his career, he was Josephine’s only genuinely wealthy suitor. He and his beloved could have been well-off, protected against the world by their love. Josephine could have afforded the care she needed.

All Beethoven’s loves are buried in the Schubertpark in Vienna, along with Beethoven himself. He dedicated his great works to them. Josephine is the only one there to whom he dedicated nothing. Because society suspected she was his greatest love, the woman he called his angel, any sign of it would have destroyed her reputation. Prince Lichnowsky warned Beethoven against putting her name on any of the scores littering his piano.

9. Minona

Josephine’s seventh child, Minona, may have been Beethoven’s. Minona is Anonim spelled backwards: the girl with no name. No origin. Minona was born nine months after Josephine and Beethoven rendezvoused in Prague on July 3, 1812, after Stackelberg had abandoned her. (After Minona was born, the count abandoned Josephine again, knowing Minona couldn’t be his.) Josephine took another lover, Andrian, had a child by him, and died in poverty in 1821. She was 42. Minona is buried in the Schubertpark. All that remains of her crypt is its nameless lid on the ground. Minona, even in death, remains an anonym.

10. Ripples

When Beethoven was teaching Josephine, starting around 1799, they visited the Hungarian Sea, also called Lake Balatón, the largest lake in central Europe, just south of her castle.

Like the Esterházy’s Esterháza, and like Mervyn Peake’s fictional castle Gormenghast, Martonvásár was built on a vast swamp. As with Mahler, Grieg, and Brahms, summer provided Beethoven the time and the atmosphere for visiting the countryside and composing. One of his favorite places was Josephine’s castle, surrounded by 8,000 acres of ponds and streams, developed from enormous wetlands.

The Brunsviks drained the swamps and planted thousands of trees, eliminating malaria and rendering the land livable. Josephine asked every visitor to plant a linden tree. Beethoven planted one which is still there.

Even after Josephine married, Beethoven continued to visit her there. In the flush of forbidden love, he began the Moonlight Sonata there in 1801, finishing it in 1802.

He completed the Appassionata Sonata there as well. It is dedicated to Josephine’s brother. Historians have speculated that Beethoven’s last two piano sonatas were requiems for her. But the last three Beethoven sonatas are requiems, really. Opus 109, No. 30, is the most lyrical melody Beethoven ever wrote, very unlike most of his other sonatas.

The Moonlight Sonata itself is a memento of the love that could have changed Beethoven’s life. And Josephine’s. There would be other lovers in their lives afterwards. But the innocence was over.

As Therese wrote, “We were young, cheery, beautiful, childish, naïve.”

There were no more true loves afterwards, no more Immortal Beloveds.

Josephine’s castle outside Martonsvásár in Hungary

11.

The Last Three Letters to Josephine

Josephine wrote that at last Beethoven had someone worthy of him: her.

Beethoven wrote his Heiligenstadt Testament on October 6, 1802, when he was forbidden to see Josephine by her mother. Their love persisted through two marriages and a time fraught with preparations for war against Napoleon.

When Beethoven wrote the Moonlight Sonata in 1801, Prince Lichnowsky warned him that her name couldn’t be seen as a dedicatee. It was Too Much Information. She was already married. So Beethoven dedicated the Moonlight to her cousin Julie, Countess Guicciardi, with whom he had had a brief fling.

Beethoven’s letters to Josephine were discovered after his death; her letters to him surfaced only a few decades ago. Beethoven’s last three letters to Josephine come two weeks after Napoleon forced Austria to invade Russia on June 24, 1812. Note how they come within hours of one another.

The First Letter

Monday, July 6, 1812, morning

“My angel, my all, my very self —Only a few words today and at that with pencil (with yours) —Not till tomorrow will my lodgings be definitely determined upon— what a useless waste of time—Why this deep sorrow when necessity speaks—can our love endure except through sacrifices, through not demanding everything from one another; can you change the fact that you are not wholly mine, I not wholly thine—Oh God, look out into the beauties of nature and comfort your heart with that which must be—Love demands everything, and that very justly—thus it is for me with you, and for you with me. But you forget so easily that I must live for me and for you; if we were wholly united you would feel the pain of it as little as I. My journey was a fearful one; I did not reach

here until 4 o’ clock yesterday morning. Lacking horses the post-coach chose another route, but what an awful one; at the stage before the last I was warned not to travel at night; I was made fearful of a forest, but that only made me the more eager—and I was wrong. The coach broke down on the wretched road, a bottomless mud road. Without such postilions as I had with me I should have remained stuck in the road. traveling the usual road here, had the same fate with eight horses that I had with four. Yet I got some pleasure out of it, as I always do when I successfully overcome difficulties. Now a quick change to things internal from things external. We shall surely see each other soon; moreover, today I cannot share with you the thoughts I have had during these last few days touching my own life—If our hearts were always close together, I would have none of these. My heart is full of so many things to say to you—ah—there are

moments when I feel that speech amounts to nothing at all—Cheer up —remain my true, my only treasure, my all as I am yours. The gods must send us the rest, what for us must and shall be—Your faithful Ludwig.”

The Second Letter

Monday, July 6, 1812, evening

“You are suffering, my dearest creature— only now have I learned that letters must be posted very early in the morning on Mondays to Thursdays —the only days on which the mail-coach goes from here to K. You are suffering—Ah, wherever I am, there you are also—I will arrange it with you and me that I can live with you. What a life!!! thus!!! without you—pursued by the goodness of mankind hither and thither— which I as little want to deserve as I deserve it—Humility of man towards man—it pains me—and when I consider myself in relation to the universe, what am I and what is He—whom we call the greatest— and yet—herein lies the divine in man—I weep when I reflect that you will probably not receive the first report from me until Saturday—Much as you love me—I love you

more—But do not ever conceal yourself from me—good night—As I am taking the baths I must go to bed—Oh God—so near! so far! Is not our love truly a heavenly structure, and also as firm as the vault of heaven?”

The Third Letter

Tuesday, July 7, 1812, morning

“Though still in bed, my thoughts go out to you, my Immortal Beloved, now and then joyfully, then sadly, waiting to learn whether or not fate will hear us—I can live only wholly with you or not at all—Yes, I am resolved to wander so long away from you until I can fly to your arms and say that I am really at home with you, and can send my soul enwrapped in you into the land of spirits—Yes, unhappily it must be so—You will be the more contained since you know my fidelity to you. No one else can ever possess my heart—never— never—Oh God, why must one be parted from one whom one so loves. And yet my life in V is now a wretched life—Your love

makes me at once the happiest and the unhappiest of men—At my age I need a steady, quiet life—can that be so with us?

My angel, I have just been told that the mail coach goes every day—therefore I must close at once so that you may receive the letter at once—Be calm, only by a calm consideration of our existence can we achieve our purpose to live together—

Be calm—love me—today—yesterday—what tearful longings for you—you—you—my life—my all—farewell. Oh continue to love me—never misjudge the most faithful heart of your beloved. Ever thine, ever mine, ever ours. L.”

12. Aftermath

Beethoven by 1817 had no energy left for anything but his symphonies. He would be dead in a decade. His obsession with grooming his nephew Karl to carry on his fame created an heir with no interest in anything other than spending his inheritance.

Beethoven never supported his daughter, Minona. He lost interest in Josephine, ill, destitute, broken. His women would always be young, wealthy advocates for his fame. Not poor or available. When the world got too close, he hid behind music.

By the time Stackelberg had come into his wealth, Josephine was horrified by him. He had successfully destroyed her reputation, portraying her to Vienna as an incompetent mother and a slut. That pervasive gossip may have swayed even Beethoven.

Stackelberg had taken seven of her children away in two installments. He kept Josephine’s children away from his other children. (This was considered enlightened at the time.)

Josephine didn’t have the stamina to keep her eighth child, Emilie, and gave her up to Emilie’s insubstantial father, Andrian; Emilie died soon afterwards. Andrian abandoned Josephine even before that.

Josephine’s one reason for not marrying Beethoven had been that she would have lost her children. In the end she lost all her children, her health, her security. Her mother disowned her. Her children withdrew from her. Her sister Therese despaired of her. Her brother erased her name from family records. Beethoven’s secretary Schindler ripped out all the pages referring to her from Beethoven’s conversation books.

Therese and her own daughter later became the champions of children’s education in Hungary.

After Vivaldi died, he was forgotten for 200 years. After Shakespeare died, it was 200 years until he was revived by

the Germans. After Beethoven died, it was 130 years until Therese’s diary and Josephine’s love letters to him surfaced (in 1957), resolving the question of the young countess Beethoven had loved with all his soul for 17 years.

After Josephine, Beethoven slept with Julie Guicciardi and Marie Erdödy, dedicating major sonatas to them (the Moonlight, written for Josephine, was

dedicated to Julie). To him, dedications meant income, not memories. There was a deep friendship with both Antonie Brentano and her husband, Franz, Amalie Sebald, Dorothea Ertmann, Therese Malfatti. During many of these affairs, Josephine was living in a hut in Vienna, abandoned.

Just how immortal was his beloved, really?

For 13 years Beethoven and Josephine had a chance to be innocent. To be happy. But the moment passed. Radiant Hungarian dawn had faded into the permanently overcast Austrian sky.

Moonlight Sonata

BOOK TWO

1. Wedding Ring

This is a more affirmative view of the storm in the Moonlight Sonata.

No plane of this tortured, jeweled land

That isn’t spinning, waving, facets

Loose-limbed in a band of liquid wind, An aquarium as much ocean as it is

Roots and sand, a bezeled field of fronds

And blades tethered vaguely to some Jetty, tendril, cleat: carbon Sails billowed in the constant gale.

Around the edges of the offing, a blaze

Of bright baguettes rings the sea foam rail Beneath the downspout prongs of light, The glaze of dawn, a roiling surge of waves

Set inside a pavé of horizon, The storm’s melee surrounded by A crystal throne of haloes in the sky, The side-stone diamonds of the sun.

BOOK THREE

. Ghosts in the Moonlight

The title Moonlight was applied to this sonata five years after Beethoven died. Beethoven never heard the name It was supposed by a critic to represent moonlight on Lake Lucerne (where Rachmaninoff later built his beloved villa Senar). Beethoven had never visited the lake.

It is much more likely, given where Beethoven was at that time (1801 and 1802), to be a kind of Sehnsucht, a nostalgic yearning for moments he shared with Josephine. Maybe he was summoning up waves lapping on the lake at her castle. (In the moonlight, for extra credit.)

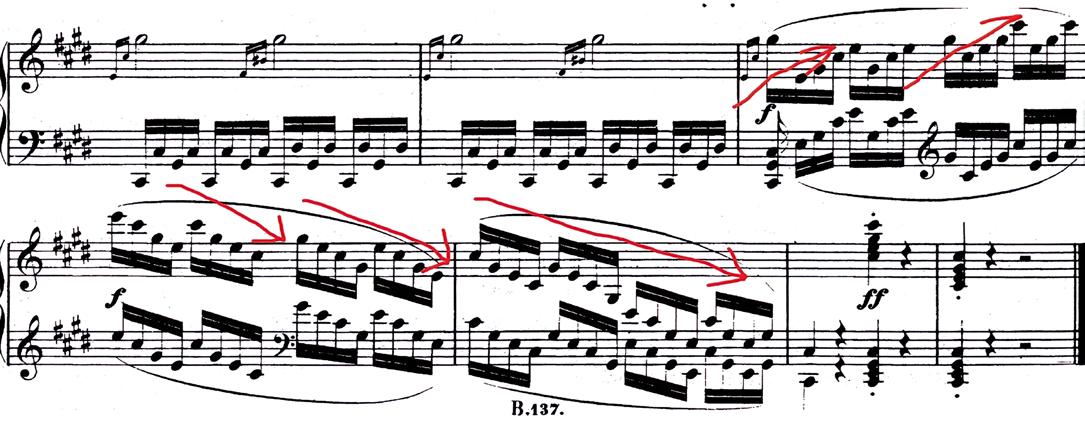

Beethoven might have wanted to present waves the way Chopin would later do in the Ocean Etude, Op. 25, No. 12, or Liszt, in his Legend of St. Francis de Paul

Walking on the Water. But Beethoven’s sense of structure demanded that his storm be formed from the triplets in the first movement. So in the third movement of the Moonlight Sonata the restrained and

controlled arpeggios (which suggest a storm on the Hungarian Sea) simply expand the original idea of the triplets.

Lake Balatón would be more likely than Josephine’s ponds to have waves, because it is the largest lake in Europe, an inland ocean, ringed with taverns, a wonderful spot for lovers (at least at night, when the mosquitos die down). The Carpathian Mountains drain into an enormous swamp called the Carpathian Basin, ridden with disease and bugs, which was why it was so affordable for the Brunsvik family to settle there.

Why was Beethoven’s passion in the Moonlight Sonata so controlled, so Classical, so Bachlike?

The sonata is a very solidly built cathedral, where there are few surprises.

Despite his iconoclasm, under his Romantic surface he was basically Bach. Beethoven knew the end of a piece when he wrote the first three measures of its beginning.

Vladimir Nabokov’s novel The Defense has a similarly premeditated ending. The only way the antihero Luzhin thinks he can outwit the author’s control over his life is to throw himself unexpectedly out a window and kill himself. But, as he nears the pavement at the last second, he notices the neat squares of the concrete, and realizes it is a chessboard; he has been checkmated by the author.

Beethoven suspected that the moonlit interludes would all end in tears.

As Martyn Rady mentions in The Habsburgs, Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut Melancholia I stressed that melancholy was a kind of genius necessary for alchemy, for turning baser matter into gold. The melancholy of the first movement is necessary to transmute the ordinary, even pedestrian matter of the second movement into the existential fury of the third movement.

The second movement is the transition. In it the first movement theme becomes Cubist, fragmented, leading to the emotional outburst of the third movement.

The sonata follows this hermetic formula, morphing arid, seemingly unproductive themes through the alchemy of Beethoven’s enkindled metamorphosis into the molten ore of the third movement.

Beethoven must have suspected that his crushes on young noblewomen would end badly. His anger came from knowing that his romantic model was flawed. But he couldn’t change it. He was in love not just with love, but with nobility. All his genius couldn’t raise his stature, however, in the eyes of the women he loved.

2

.

First Movement

The triplets themselves may represent the three parts of his love for Josephine: “Forever you, forever me, forever us,” as he wrote to her. But he knew they were fated to be checkmated by her mother’s disapproval. The triplets would end, drowned in Lake Balatón.

The triplets begin as onomatopoetic ripples on the lake at Josephine’s castle. By the third movement the three-part ripples have become four-part arpeggios.

The ripples initially occur over five slowly descending octaves in the left hand: This is the only melody of the sonata.

Beethoven uses it in disguised versions in each movement.

3. Second Movement

The second movement is in flats, while its surrounding movements are in sharps.

The flats convey a sense of restfulness, of peace: the interlude between the storms. D-flat is a classic key used by the Romantics (Liszt, Chopin, Fauré) to induce lethargy, somnolence, a meditative state. (This is discussed at length in Brinkerhoff’s The Himalaya Sessions: Excesses and Excuses, Vol. I, see Bibliography, page 92).

C-sharp and D-flat use the same notes, but the illusion of how they are “denoted” by the “accidentals” in their key signatures creates opposite effects: a C-sharp note is very Dracula, vampiric, cloudy, troubled,

while the same note written as a D-flat is dreamy, a nocturne, a boat song, a fairy tale.

So the island of the second movement is surrounded by a lapping lake on one side and a rising sea on the other, although it is made of the same materials.

The five descending notes of the first movement also provide the theme of the second movement:

This theme is echoed at the same time by the left hand as well as the right. It continues as the inner melody in the second section of the second movement:

The trio of the second movement breaks up this same theme into Cubist fragments:

The stage is set for the dissolution of love into anguish.

4. Third Movement

After the last note of the preceding movement, the wind rises and the sea stands up with no warning.

Beethoven could have written the sea more freely, more wildly, more Romantically, as Chopin did in his Ocean étude 35 years later:

Beethoven was locked into the triplets from the first movement. The storm had to derive from the triplets of the first movement. The obvious solution was four-note arpeggios:

They are only one note longer than the triplets of the first movement.

These are classical waves, which have rules anchored in Bach’s own arpeggios. They are derived from tradition, and from the first movement itself.

And they have a different setting: rather than Romantic lakeside lappings, these are dangerous waves on the vast inland Lake Balatón.

Inside each four-note arpeggio is the three-note triplet of the first movement. If you play the first note of each arpeggio, you hear this triplet motif.

But if you accent only the second note of each arpeggio, you hear the same triplet motif.

Those five notes are the same five notes as the initial bass octaves in the first movement. Note how the bass notes descend from C-sharp as do the octaves in the first movement:

The same thing happens if you stress the third note of the arpeggio. The triplet theme appears.

And the same thing happens if you accent the fourth note of each arpeggio.

So the ripples of the first movement exist four times in each arpeggio grouping.

There are five groups of arpeggios, each group agreeing with the bass note underneath it.

They also match the descending motif in the second movement:

The only difference between movements is that the middle movement is bookended by two sharped movements, which use their sharps to convey a mood of ominous Gothic weather in both cases, one slowly,

5. The Mannheim Rocket

The Mannheim Orchestra, directed by the composer Johann Stamitz in the late 18th century, was an orchestra of individual virtuosos, an “army of generals,” as the historian Charles Burney called it. Haydn and Mozart admired it. It was visited by Liszt to hear its most famous technician, Jakob Scheller.

Scheller’s innovations in violin playing made Paganini possible. Scheller produced harmonics on his violin like those of a flute or pipe organ, called flageolet tones. He used his violin case to produce echoes. He loosened the hair on his bow so it touched all four strings. He played extraordinarily fast runs and leaps with evenness, clarity, and fullness of tone.

Beyond its musicians, the orchestra developed novel and exhilarating effects, such as lengthy crescendos, abrupt dynamic changes, and the Mannheim crescendo, also called the Mannheim rocket and the Mannheim roller, where a rising figure (a scale or arpeggio) sped up and grew louder as it rose higher and higher over an ostinato bass line, which exactly describes the third movement of the Moonlight. The Germans called it the Mannheimer Walze.

It is an imitation of a fireworks rocket, rather than a military rocket. It shoots up and explodes, all in a few seconds, meant to dazzle rather than destroy.

Beethoven used it many times, such as in his first piano sonata:

The third movement of the Moonlight begins with five rockets, after which a frenzied short interlude appears and repeats. It is completely inexplicable, entirely out of character with the rockets which surround it. Why has Beethoven placed it in this hostile territory and given it such prominence? I’ll call it the butterfly theme.

6. The Butterfly Theme

This short, four-measure interlude is a comment in the margins, a kibbitz, an aside, an immediate detour from the driving arpeggios:

The English wizard John Dee, a member of Queen Elizabeth’s court and an intimate of Emperor Rudolf II (ruler of the Habsburgs during Beethoven’s time), claimed to catch angels in mirrors. This explains Beethoven’s Rorschach blot, the butterfly-wing mirror theme. It duplicates its first wing with the verso of the second

wing. It is, beyond that, a dreamcatcher, a mirror of the soul.

Beethoven is so angry he feels he needs to break in and editorialize with this mirror. The theme is formed from the only melody in the sonata: the descending bass line of the first movement:

But here at the beginning of the third movement it is mirrored: it both ascends and descends.

It cancels itself out. It is neither coming in nor going out. It is what Noam Chomsky called negative syntax, which Leonard Bernstein applied to music in his Norton

Lectures. If it were a math equation (1 minus 1), it would result in zero. The ascent has been cancelled out by its opposite, the descent. But in music something remains, something has been said. Beethoven is saying that the romance of the lapping lake in the first movement has been overwhelmed by prejudice. His melody, his love, has been canceled because he is a commoner.

This mirror image replicates the alchemist John Dee’s mirror. The passage may seem out of place, but it is a memento mori in the midst of revelation, Beethoven’s warning to himself to remain humble, despite the white noise of the rockets surrounding him.

Beethoven has after all copied his major statement, the rocket theme of the third movement, from the Mannheim school.

The famous theme of the Moonlight isn’t his. Even the triplets of the first movement might be called a diminution, an abbreviation of the rocket theme Beethoven had already planned before he wrote a note of the sonata.

When Beethoven’s diaries were discovered, we learned that Beethoven had devised many of his later themes when he was a young man; it just took him decades to encase them in the structures they deserved. He knew where he was going, because he’d already been there.

So the butterfly theme is in fact Beethoven’s main theme: not the arpeggios, but the four ascending notes and then their reverse, the four descending notes. These are the initial left-hand octaves in the first movement, and the initial descending notes of the second movement.

These four descending notes recur throughout the sonata, and most emphatically in the rest of the third movement.

In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Julian Jaynes posits that back in the day our left brain was led by messages from the right brain. The right brain was the instigator, which gives the rest of advice. I still hear that tiny voice of reason. According to Sir James George Frazer in The Golden Bough, mythologies throughout history have shared that common motif of messengers’ voices, which pass on the torch of rationality.

In the Moonlight Sonata this dialogue between the left and right brain is the butterfly theme, the constant “he said, she said” argument between Beethoven and himself over where he is going, even as the larger pattern of the sonata moves inexorably towards the resolution of sol-do.

But before that, the butterfly theme, the augmented chords at the beginning of the cadenza, hint at the disruption of the sedate traditions of Czerny and Haydn, at the coming wars, the discord on the horizon.

Moonlight Sonata

7. Ghosts of the Future

There is an unusual moment inside this seven-note butterfly theme. As the theme descends, the sixth note sounds a bit jarring, as if it isn’t well-tempered any longer. It sounds like it’s outside the harmonic set of the home key. This invasive note comes from the future.

Beethoven then stresses this out-of-thebody tone by playing it repeatedly, seven times. Beethoven has used such repetition before. In The Rage Over the Lost Penny variations, he invents endless variations on an annoying theme until it becomes even more annoying.

Beethoven inserts the butterfly theme between his arpeggios to keep himself honest, to remind himself that his model is Bach. The mirror passage sounds a lot like the beginning of Bach’s D Minor organ fugue.

Beethoven is reminding himself that the sonata was born from classical structures. He knows there’s something beyond those shapes, more modern music which breaks out of those simple forms and rises beyond the dependable harmonies of Mozart and Haydn. You might say he’s hearing music that hasn’t been written yet. Schoenberg’s mathematical tone rows.

Beethoven doesn’t see why music always has to be pretty, or rhyming, or in the expected key. But he doesn’t get too far out of line. Just enough to notice the horizon.

To a modern ear these jarring seconds still sound Classical, or at least Romantic. But to Beethoven’s age they must have been shocking, unexpected. This interlude reminds me of Hamlet’s father’s ghost, who reappears in the play Hamlet to remind Hamlet of his mission: to expose his uncle as the killer of his father,

and to take back the kingdom from his uncle, who has named himself king. Hamlet has gotten sidetracked (he’s not the only one), shaming his mother for marrying his uncle, so the ghost reappears to remind him: not forget.

This visitation Is but to whet thy almost blunted purpose.

The ghost of the butterfly theme feels the third movement should remember where it comes from. It comes from Bach, as does the entire sonata.

8.

The Demon Note

The one jarring note is a “passing” tone, a note that leads, in passing, from one harmonic note to another. Just after the first octave in the first movement is a passing octave, a B note. This “passing” note leads to the more structural “A” octave.

This jarring note appears throughout the rest of the movement, almost as anchor at the bottom of the descending main theme. In the passage below, it is the note which has a double-sharp sign. The fact

that it is a double sharp is a giveaway that it is outside the mathematical set of the sonata’s harmonics. It is an alien tonality, a brief sforzando from another dimension, an inkling of a dissonant future. It is woven into the main theme, and becomes the exclamation point, the fourth note of the theme, D’Artagnan to the Three Musketeers. It is disguised as one of us.

9. The Main Theme

The butterfly melody now becomes the main theme.

Underneath the descending four-note top melody Beethoven adds its opposite, played at the same time. That is, as the top melody descends, the bottom melody ascends. It is the butterfly theme expanded:

Beethoven plays this butterfly variation many times, first in the middle range, then an octave above, to stress its importance to him:

Its contrary motion suggests Heraclitus’s insight that time goes in both directions. Time leads to the future, but also to the past. Beethoven is thinking simultaneously of his past happiness with Josephine, and that it will end in future tears.

Beethoven is channeling Bach, angels, the past, the future; in one phrase, he is commenting on his roots and on his expectations.

This is why the mirror passage seems inscrutable. It is dense with allegory, as much as any Breughel.

It becomes apparent that even the arpeggios are butterfly wings: they go in two directions: up and down. Future and past:

Beethoven is playing with time. The third movement is a hall of mirrors, butterfly wings multiplied in one another.

Note in passing how the demon note is the fourth note of the butterfly theme, giving the passage its sense of dislocation, discordance, disruption, which we associate with Beethoven. It is this one note, more than any other part of the sonata, which gives it its voice, its identity. It is also a pivot note, a foreshadowing of the later atonality of Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg. A window into the future of music.

Toward the end of the third movement, there is a cadenza, where I imagine the tempo slowing down to become more emotive, so people have time to let the melody’s poignancy sink in:

The Coda

A final arpeggio sweeps up and down the keyboard and ends in a traditional sol-do, followed by two finalizing chords, which emphatically announce the end. It might be instructive to roll the last chord softly to show how, even at its most passionate and uncontrolled moments, the sonata contains the initial Romantic ripples of the triplet theme in the first movement. But Beethoven didn’t write it that way.

11. Performance

You begin the last movement of the Moonlight with the idea of soft arpeggios leading to a loud thunderclap, and hope to maintain that pattern throughout, for consistency.

But eventually the amassed momentum of the sonata grows in sheer weight, until the rhythmic drive of the music makes all formulas disappear into its inexorable drive. Or maybe it’s me, and I’m just a sucker for frenzy. It’s what the film director Truffaut said of Hitchcock: you watch his movie to

analyze the seams, but eventually it’s just too much fun and you forget to watch for the technique.

So in Beethoven the technique ultimately disappears into the inexorable spirit, the élan vital, of its headlong flight to explode, like the fireworks of the initial Mannheim arpeggio. But the entire movement becomes one large firecracker, and if you don’t lose control, if you gradually get faster and louder with the final cadenza, its specters, its Roman candles sweep up into the night sky and then fall to the ground and blow up.

12. Homogenizing Beethoven

I

’ve always felt that playing a piece was worth it only if you could add something to it which hadn’t been said before.

The Moonlight Sonata has been standardized much as Beethoven’s slurs in the Appassionata were regularized by later editors, although Beethoven had made them all different.

Beethoven writes his arpeggios, his Mannheim rockets, so often that he gives you a chance to change them, the way the slurs in the Appassionata give different phrasings to the same theme.

The arpeggios are complicated, in that each note of them repeats the pattern of

the first movement’s triplets. That famous rippling occurs not only at the end of each arpeggio but also at the beginning and in the middle. The piece is an exploration of the way a melody can be varied clandestinely.

Pianists have followed Serkin’s example and kept the arpeggios even, not picking favorites, not voicing individual notes or themes within them. My teacher Russell Sherman believed that even a scale wasn’t simply a scale. It contained elements of its surrounding structure, the way a rainbow reveals colors in the air which are always hidden there.

So my Moonlight doesn’t sound like the records. It’s not as smooth or as homogenous; it’s not a solved equation, a question resolved. I like to think it’s alive with indirections, with contradictions, informed by its own trellis, a creature of its scaffolding.

It moves within its boundaries, a living creature. Its arpeggios aren’t fixed; each rocket has its own fireworks. For 100 years the piece has had its particular performance tradition. You play it the way Serkin played it. That’s the authorized way.

And so I accent my scales to reveal their reflected glory, and change the accents in the arpeggios to illustrate the complex weave of the triplets inside. I also voice the retrograde motion (the butterfly pattern of the four-note theme) in the driving chords interspersed among the arpeggios.

I stand, guilty as charged, wearing one brown shoe and one black shoe, my scales loosened, my arpeggios ungyved, my triplets unbraced. Once a standard has been set, we defy it at our peril. My specialty when I was young was shanghaiing my friends to distant, unfamiliar counties and houses. I haven’t changed much.

However. Chris Serkin has said that his grandfather, Rudolf, never played a piece the same way, even though the Marlboro School and the Curtis Institute under his leadership respected the score religiously. We are wrong to think that Serkin had only one version of anything. Gidon Kremer, at points in his career, would vary the tone and intent of the dialogue without changing a single word.

Not that anyone succeeds in this attempt to find deeper truths underlying the marble of accepted revelations. We fail, and that failure leads us to try again.

Dylan Thomas said he’d like to write the perfect combination of words that would result in never having to write again. Of course we never do, and so we go on writing. We write new poems because the last one didn’t quite do it.

Russell Sherman felt that spontaneous inspirations might not hold up under the scrutiny given to recorded music, which is supposed to be the last word.

Rather, the thoughtful attempt to dig deeper into the celestial mechanics of the galaxy is what produces great science, and the hubris of daring to disturb the universe is what great music and great poetry celebrate. We shouldn’t demonize the effort itself, but celebrate even those failed expeditions into dark territory.

13. Beethoven and Place

History has understandably focused on Beethoven’s time in Vienna and Bonn, the cities around which most of his life revolved.

But, like Grieg, Schubert, Rachmaninoff, Brahms, Mahler, Copland, Barber, and so many others, Beethoven wrote more during the summer, when he and the city were on vacation, when his life was closer to his younger years, and he could take walks in the charming villages, on mountain paths, along alpine lakes and streams, ending at a country tavern with a beer, a schnitzel, and Gemütlichkeit.

As Brahms’s sign on his backpack read, frei aber froh, free but happy. It was that unfettered leisure which left notes free to leap into his mind, which bought time to bookend his periods of contemplation, so that there would be no unpleasant pressure from bills, concert

dates, social events, the business of music.

As anyone who writes symphonies, poems, or novels knows, or as anyone who paints knows, there is a joy which comes from having no responsibilities, from feeling like a teenager, surrounded with what climbers call the freedom of the hills.

The date of the Moonlight Sonata puts Beethoven in Josephine’s family castle in Martonsvásár, Hungary, south of Pest. He wrote the Tempest Sonata in Heiligenstadt, a mountain village of vineyards in Thuringia, Germany, south of Hanover and Braunschweig. There is a rustic wine tavern there where Beethoven had stayed, the Mayer am Pfarrplatz.

He wrote the Appassionata Sonata in Baden and Mödling, and also partly at Josephine’s Martonsvásár, where the lakes and streams of the Carpathian basin created a playground for the Austrian

aristocracy, who developed country estates on the inexpensive swampland of Hungary. Hungary was where everyone went in the summer.

Beethoven would write between May and October, when the weather in the small villages around Vienna was most congenial to outdoor walks.

He moved 67 times during his 35 years in Vienna, on account of frequent quarrels with landlords and his habit of summering in the small villages around Vienna, where he moved equally frequently.

He spent time regularly in Baden and Mödling and their woodlands. This was the Wienerwald, famous from Johann Strauss II’s 1868 opera Tales of the Vienna Woods, an area of forest glades five times bigger than the combined boroughs of New York City. In those woods lie the

later symphonies of Beethoven, several Schubert sonatas, Mozart’s Magic Flute, Strauss’s celebration of carefree village life.

In the charming villages of Nussdorf and Grinzing you can sit in the cobbled courtyards of Biergartens where Beethoven ate and drank. You can hike into the hills above the villages, through public trails, into vineyards. Today this rural paradise is a bus stop away from Vienna. When travel was by coach, it was a hard day’s slog.

Beethoven visited Hetzendorf, Penzing, Döbling, Heiligenstadt, and Jedlesee, small villages today incorporated into Vienna. Jedlesee, where Beethoven was invited during the summers of 1801–03, was then the residence of the Countess Anna Maria Erdödy, to whom he dedicated four works.

Beethoven spent a dozen summers between 1807 and 1825 in the town of Baden bei Wien (the 14 mineral baths near Vienna), moving around as much as he did in Bonn and Vienna. Baden is surrounded by nature, spread out at the foot of the 2800-foot Calvarienberg (Mt. Calvary). Beethoven enjoyed walking in the nearby Helenental (Helen’s Valley). His loyalty to it parallels the loyalty of Johannes Brahms, decades later, to the town of Bad Ischl, near Salzburg, where Brahms spent 12 creative summers during the 1880s and 1890s.

Most of the buildings Beethoven occupied in Baden are still in existence. Beethoven first stayed, in 1807, at the Johannesbad, now a spa. During the summers of 1808, 1809, and 1813, he stayed at Weilburgstrasse 13, then known as the Sauerhof. It is still a privately owned hotel. In 1822 Beethoven stayed at an inn called Zum

Goldenen Schwan (The Golden Swan), located at what is now Antonsgasse 4. In 1816 he stayed at Breitnerstrasse 26, later known as Castle Breiten, and on another occasion at Kaiser Franz-Ring 9, near what is now a public library. He also had quarters at Magdalenenhof 87 and Rathausgasse 10, where he worked on the Ninth Symphony.

Like Brahms after him, Beethoven sometimes composed several pieces simultaneously, working on them in many locations in Baden, Mödling, and elsewhere.

For instance, during his summers in Baden, he worked on the Piano Sonata in E- flat major, Les Adieux, Op. 81; Wellington’s Victory, Op. 91; the Elegiac Song (Cantata Op. 118); the Mass in D major (the Missa Solemnis, Op. 123); The Consecration of the House overture in C major, op. 124; String Quartet Nos. 13 and 15; the Piano

Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 (the Appassionata); and the Ninth Symphony in D minor, Op. 125.

Mödling is just south of Vienna. Its name is of Slavic origin and refers to slowly running water. In Beethoven’s day Mödling was a small market town with some 300 houses. He was there briefly in 1799, but between 1818–21 he stayed there for a part of each summer. As he wrote to

a friend, “As for me, I am rambling about in the mountains, ravines, and valleys here with a piece of music paper….”

Beethoven worked at Hauptstrasse 79 in Mödling in the summers of 1818 and 1819. Known as the Hafnerhaus, the residence now contains rooms dedicated to Beethoven. Beethoven’s quarters consisted of three rooms on the first floor, on the right. It was here that Beethoven worked on the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth Symphony (as he had in Baden), as well as the Mödling Dances, Piano Sonata No. 29 (“Hammerklavier”), and the Diabelli Variations.

Mödling when it arrived, a year after it had been shipped.

Teplitz (today known as Teplice) is the second largest spa town in the Czech Republic. It was often called the Grand Salon or little Paris due to its clientele and rich cultural life. The thermal springs in Teplitz have been popular since the 8th century. According to local legend a shepherd noticed his injured pig recovering by wallowing in the hot mud.

Teplitz

In 1818 Beethoven was sent an English Broadwood grand piano as a gift from the London manufacturer. It was conveyed from England by ship via Trieste and then overland to Austria. Beethoven was in

In the summer of 1812, Beethoven and the novelist and scientist Johann Wolfgang von Goethe met in the city. They spent several days together, taking walks and discussing art and politics. This was the time when Beethoven rendezvoused with Josephine von Brunswik. It was then that their child, Minona, was conceived.

Epilogue

The entire sonata is based on the five bass octaves in the first four measures of the first movement:

These five notes provide the melody for all three movements. Its end is contained in its beginning, as is often the case with Beethoven. His sense of form is circular, so that the conclusion, the moral, is hidden in its beginning. It’s always there.

This energizes the notes, because there’s a cryptic code hidden in its harmonies.

To a musician harmonies tell stories the way words do. Beethoven ends his wild ocean ride the way his gentle lappings begin.

The mild Romantic evening of the first movement has been lost to the oceanic chaos of society in the third movement, to the rules that interfere with love between a countess and a commoner.

Beethoven’s most egregious innovations against ancient harmony nevertheless remain within the chessboard of Classical forms, within the music of the spheres.

The sonata contains more than it presents at first hearing. It transmutes Beethoven’s rational insight into his plight into an explosive and emotional unraveling.

Bibliography

The Immortal Beloved Compendium: Everything About the Only Woman Beethoven Ever Loved, John E. Klapproth, CreateSpace, North Charleston, SC, 2018

Beethoven’s Only Beloved: Josephine! A Biography of the Only Woman Beethoven Ever Loved, John E. Klapproth, Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, North Charleston, 1st ed. 2011

Beethoven and His Immortal Beloved Josephine Brunsvik: Her Fate and the Influence on Beethoven’s Oeuvre, Marie-Elisabeth Tellenbach and John E. Klapproth, 2014

Michael Lorentz documents the Schubertpark in his blog: http://michaelorenz.blogspot.com/2017/12/the-exhumation-of-josephine-countess.html

Liszt: The Artist as Romantic Hero, Eleanor Perényi, Little, Brown, 1974

Schubert’s Vienna, ed., Raymond Erickson, Yale University Press, 1997

The Habsburgs: To Rule the World, Martyn Rady, Basic Books, 2020

Maria Theresa: The Habsburg Empress in Her Time, Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger, Princeton University Press, 2021

The Habsburg Empire: A New History, Pieter M. Judson, The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2016

The Himalaya Sessions: Excesses and Excuses, Vol. I, Albany Music Group, Troy 0358 , 1999 [SACD, BD, and book], Adrian Brinkerhoff, text only on pianistlost.com and TippetRise.org.

The Spell of the Vienna Woods: Inspiration and Influence from Beethoven to Kafka, Paul Hofmann, Henry Holt & Co., 1995

Moonlight

Peter Halstead

Producer: Monte Nickles

Production Director: Jim Ruberto

Editor: Monte Nickles

Piano Technicians: Mike Toia, Drew Carter

Book Design/Production: Craig White

Photography: Cathy Halstead, Peter Halstead, Kevin Kinzley, James Florio, Erik Petersen, Craig White