February 2024

Why is There no Sex on Stage?

Emerald Fennell: Fresh Auteur or Flawed Filmmaker?

The Spectre of Sex

Meet Our Team!

February 2024

Why is There no Sex on Stage?

Emerald Fennell: Fresh Auteur or Flawed Filmmaker?

The Spectre of Sex

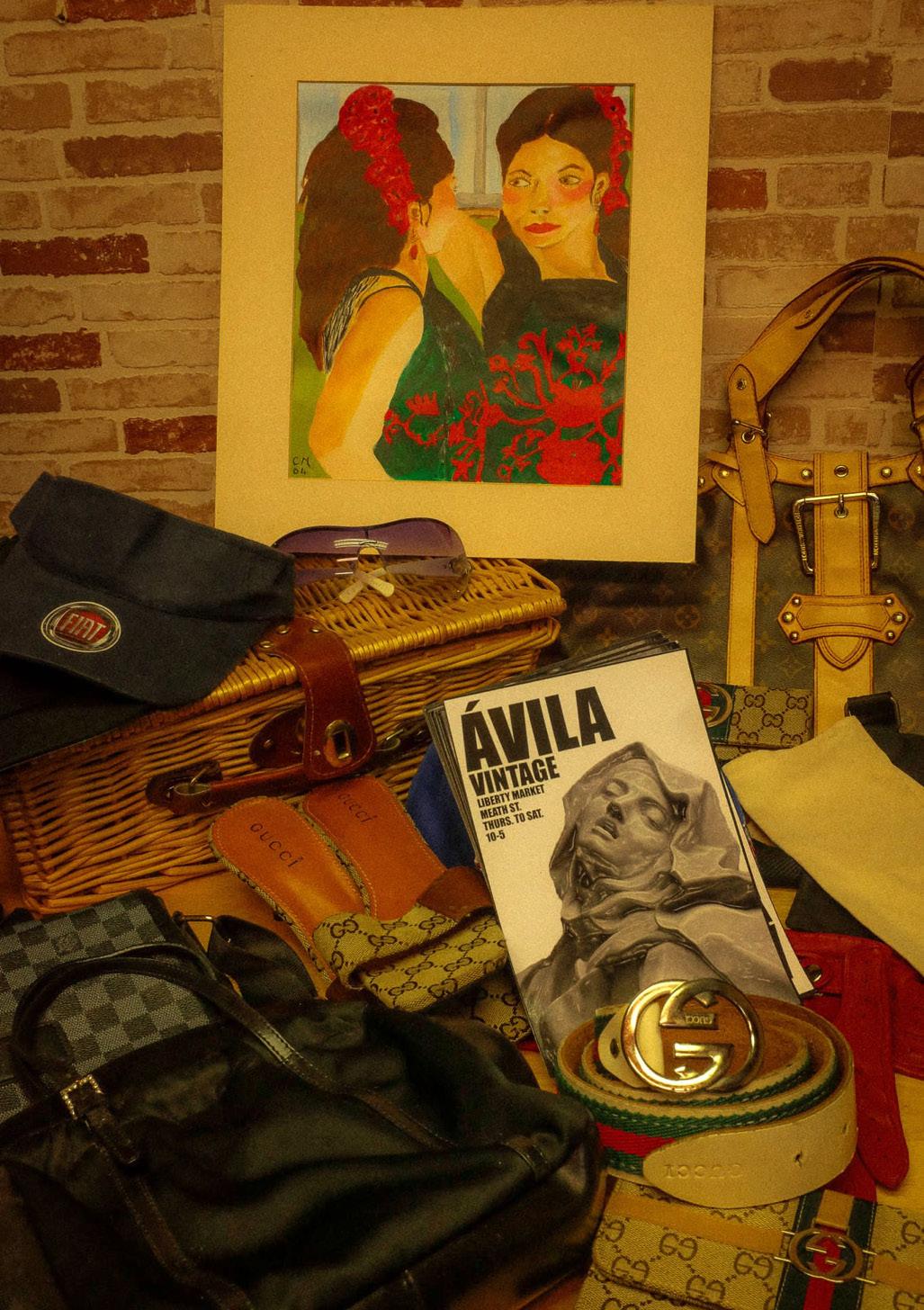

Two Italian girls talk the vintage experience, Italian fashion and the importance of loving your body with small business owner Niamh O’Dwyer

Nestled deep within Liberty Market’s many alcoves, Assisi Vintage (previously known as Ávila Vintage) is an eclectic hodgepodge of designer pieces, one-of-a-kind vintage gems, and flashy, sporty, merchandising bits – the mixing of which proves surprisingly effective. A table display shows a pair of vintage Gucci kitten heels next to a polyester Fiat hat; root through what’s hung up on a rail and you might find 1970s linen nightgowns, a silk kimono, elegant tailored dresses or the tackiest printed t-shirt you’ve ever laid eyes on, all at a price commensurate to their worth.

As interesting as the selection is its proud curator: Niamh O’Dwyer runs Assisi Vintage (with the help of her son Sean). She was happy to show us around and explain the story behind each piece, all while sharing her thoughts on what she thinks the moral responsibilities of a vintage shop owner are, telling us what dressing well entails, and where she got her necklace and cameo brooch.

M&G: How did your business start?

N: I’d have to go through my whole life story to answer your question, but to make it brief: thirty years ago I started collecting vintage clothes because I just found them to be instantly gratifying, they felt like heirlooms, and shortly after I realised that in Italy I could find the most beautiful pieces in the world.

My son has experience in e-commerce so we joined forces after we realised that fashion is really about building a community, (our business) is a tiny experiment merging the curated collection I’ve built up in the past thirty years, a one-on-one customer service experience, and an online presence.

On the collecting process:

N: When I was living in Italy, I started going to outdoor markets which had the best selection. These salespeople at the markets were the real connoisseurs, the hallmark of Italian fashion isn’t just the big names, but also these people, they’re the real experts, what I loved most were these one-on-one relationships I’d build with them.

What fashion does is make you fall in love with what’s intangible, and I think the point is to try and build a bridge between ourselves and that intangibility, which is also why I have a lot of respect for the fake. It’s a skill that requires practice.

M&G: What do you make of the second-hand and vintage scene in Dublin? Especially with regards to prices

N: it’s completely corrupt that vintage and second-hand pieces now cost almost as much as if they were new. If I paid very little for a pair of Versace pants that someone in Italy decided to throw out for whatever reason, then I should try my best to make this beautiful item a part of my community-building process (by reasonably pricing it).

M&G: What do you think about Gen Z’s style?

N: I feel that there’s a pressure to showcase yourself and your fashion on -social media that leads to a sort of forensic image of the self, which is not conducive to dressing properly, and won’t do much for your confidence. If I’m constantly obsessing over my image and comparing myself to influencers then how am I supposed to go to work and do a good job and focus on other things? Our lives are so fast. What I love about young people is that they’re happy being part of a community, there is great group spirit (among Gen Z). I’m here to ‘mother’, I’ll tell you like ‘throw on those trousers and you’ll be absolutely gorgeous, I’ll give you a good price, you don’t have to worry ‘cause you’ll look absolutely gorgeous’. I see people go from sceptical to confident, I think that that close personal experience with the customer matters.

M&G: And what style advice do you have for us?

N: Be shameless! Go into shops, try everything on, the mirror is your guide, and glorify yourself! Like an actor, from the feet up. I also think there has to be an element of love for your body to really achieve good style…. take Gianfranco Ferré for example, his clothes just show you that the body has to be loved, the Italians do that better than everyone else. Anyway, find a changing room, find something that fits you! Carry yourself with unabashed confidence, even when you make mistakes, especially when you’re twenty you could get away with wearing a bin bag. There is no dress like youth! That’s an Irish saying, I’m pretty sure.

In the face of an increasingly profit-driven vintage scene, as well as a digital landscape that commodifies individuality and stifles spontaneity when it comes to self-image, Niamh’s views on style and her earnestness were, admittedly, so refreshing. The process she favours is an organic one, centred around self-love, community, and fun. Coming from an expert as herself, one factor that struck us as particularly important is using your body as a starting point, a guide: finding clothes that fit and make you feel comfortable. Choosing pieces you naturally gravitate towards will make you not only look and feel great but will get your mind off the way others perceive you, that ‘forensic’ image of the self Niamh tellingly brought up when asked about her thoughts on Gen Z’s style. As Niamh says glorify yourself! If still in doubt, stop by Assisi vintage and her mentor- (or mother) ship will be extended, finding yourself embraced in a community that will remind you just how gorgeous you deserve to feel.

PHOTOS by Giulia Vettore WORDS by Margot Guilhot Delsoldabto

From something that could be worn to add some spice to a night with your partner, or as a stand-out fashion statement for your Workman’s trip, when you think of clothing that makes you feel sexy, lingerie is most likely the very first to come to mind. It is safe to say that lingerie is a department that is well established in the 2020s and is more popular than ever! The form that lingerie takes now finds its inspirations from a LONG history, this article is only a brief dip in the lacey, sensual, and Lana Del Rey-coded pool.

Lingerie and underwear itself has occupied space within the public consciousness for a millennia at this point. While it is fun to gush about the way lingerie was designed in the past, it’s interesting to understand what it was providing for women at the same time The origins of women’s underwear can be traced back as far as the Classical period. Roman women were fond of underwear that provided comfort over anything else. Leather bikinis were by far the most popular, as leather was quite versatile. During times of menstruation it was useful for soaking up period blood. Classical women were partial to a bit of athleisure from time to time (Lululemon eat your heart out!), and leather would be tied around the breasts to provide support, making their underwear so much more than just a stylish fashion statement!

The chemise was the next major upgrade in our lingerie journey. It was sheer, worn under clothes, and paired with a petticoat. Most similar in appearance to the modern ‘slip dress’, which nowadays one may choose to wear alone or over a chic pair of jeans (my own preferred method). The chemise, as we know it now, was at its most popular in the 18th century and leading into the Regency period, you may recognise it from your most recent re-watching of Bridgerton. The chemise was often slightly visible from under the clothes that were worn over it. This visibility meant that women started wanting to add more individual designs onto their underwear. The women that could afford it would choose to adorn their chemises with delicate embroidered designs. The Met holds chemises that are embroidered with silk and even metallic threads. In the same way you might get a sexy tattoo on your ribs where no one can see it, but you still know it’s there, the designs women chose were put there for their own enjoyment. Could the decoration of chemises act as one of the first examples of women using their underwear as an outlet for self expression? I think so! In the words of Ms Taylor Swift, ‘underwear would be bejewelled from here on out’, the urge to add pretty bows and flowers to our clothes was always there for us!

The 18th and 19th centuries treated us, not only to lovely diseases like syphilis, but also provided every Urban Outfitters girl’s favourite accessory and next step in the history of lingerie. Of course I’m talking about the corset! Corsets became a fashion staple during the Victorian era and have not left the wardrobes of style icons since. At the conception of the corset as we know them, they were used to achieve the highly desired hour-glass figure. The goal was small waists and large hips ladies! Continuing on the trend started with chemises, Victorian corsets would be lavishly decorated, but even more obviously this time. Corsets themselves would also be paired with pieces such as long loose skirts or split drawers, which conveniently allowed for easy access for the toilet during the day. Pairing a corset with traditionally ‘masculine’ pieces, such as trousers, was scandalous so more feminine silhouettes became the norm.

BUT of course, this conception of feminine underwear would begin to change leading into the 20th century. A bold new accessory was bursting onto the scene, one that has also has fashionistas talking lately. I’m talking about bloomers! An accessory that has been plastered all over Instagram and Pinetrest recently (I know you have at least one pair saved to our fashion board…) and hopefully one that we can see more of in the warmer months of 2024. Bloomers themselves were born out of a return to more comfortable styles, which directly contrasts past attitudes. The conception of feminine underwear seemed to be morphing back into the comfortable styles of the Classical period, but this time made with light fabrics that provided even more comfort for women. Similarly, corsets would also begin to adhere to new attitudes. They changed to emphasise the natural shape of a woman in the 1920s. Changing times seemed to catch up with corsets soon enough, however, they would almost be completely done away with by the time of the world wars, with more women in the workforce, more comfortable underwear had become the hottest trend! Stockings and garter belts came into circulation as preludes to tights. These pieces are now staples for modern-day lingerie enjoyers.

A piece of lingerie that has yet to be mentioned is the bra! A piece of lingerie that made its breakthrough in the 20th century. A cute Ann Summers set just wouldn’t be complete without it. The bra is probably the piece of underwear that allows for the most expression and variety. Whatever style you are looking for, in any size, it is at your fingertips! Bras started off simple, but as the century progressed they would begin to perfectly reflect the changing attitudes women had towards their own sexuality. Think the exaggerated cone bra debuted by Madonna in the 80s. It was bold and unapologetic, and also based on pieces from the 50s that were meant to exaggerate a woman’s decolletage. Most definitely not the stereotypical image we might have of the 50s housewife! New types of materials, such as latex and satin, were welcomed and allowed for sexier silhouettes.

With the later popularisation of the push-up bra and thong leading up to the 2000s, lingerie as we know it today became fully established and became an outlet for all women to outwardly express their own sexuality through their clothing, not to mention, look and feel extra hot doing it as well! 2000’s fashion icons interpreted lingerie in a whole new way as well. Think Paris Hilton rocking a combination of low-rise jeans and a hot pink thong with the straps hiked allllll the way up. Truly iconic if I do say so myself. While this type of statement has fallen out of favour recently, pieces like the shiny and new Skims nipple bra show that trends focusing on underwear aren’t going anywhere any time soon. Perhaps now is the perfect time to lie out our 2000’s Paris Hilton LA socialite fantasy!

With about 1000 years of history, lingerie is something that feels very familiar in the 2020s. It is a genre of clothing that has long provided comfort, an outlet for expression, and the important ability to feel sexy in any situation. With designers like Vivienne Westwood and Savage X Fenty keeping it in the mainstream, it is obvious that lingerie and the way it can make you feel are here to stay. Wearing whatever kind of underwear makes you feel your very best and sexy are the most accessible they’ve ever been these days! Go out and indulge in all those 5 Euro Penneys thongs as you please!

WORDS by Ella Breen

Met Museum Chemise

L’Essai du Corset by A.F.Dennel

WORDS by Ella Breen

Met Museum Chemise

L’Essai du Corset by A.F.Dennel

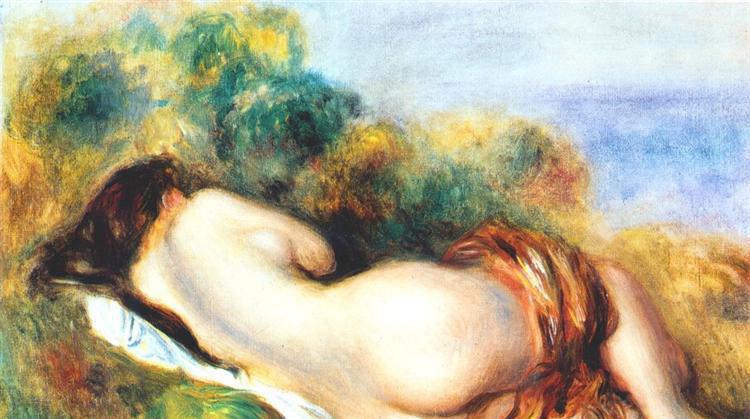

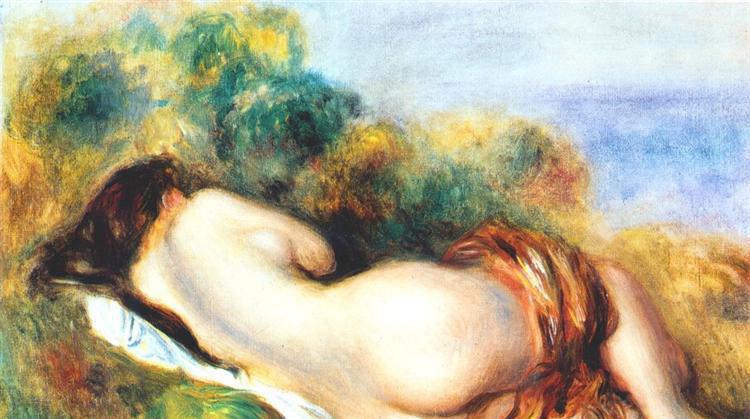

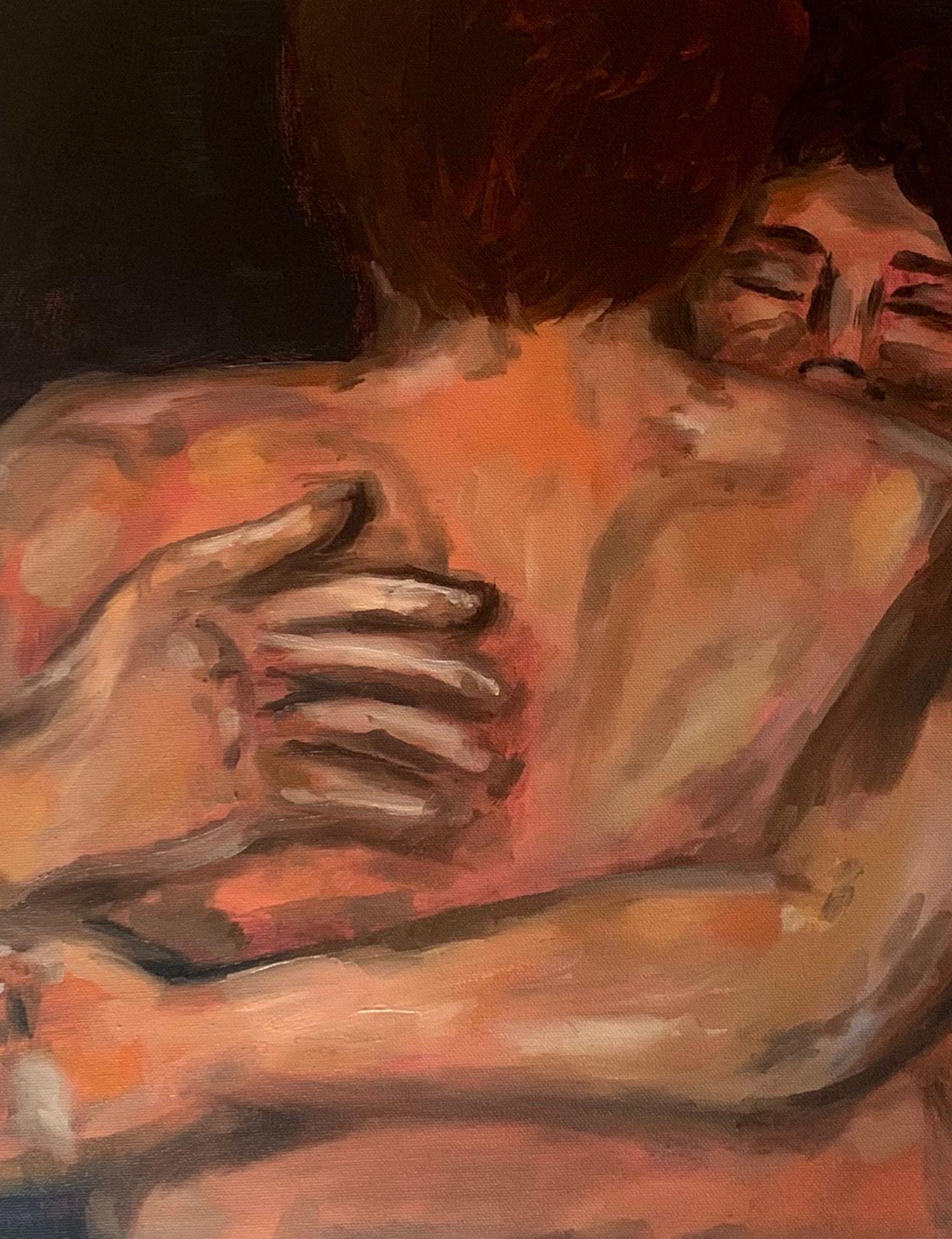

When asking most students to recount their college open day experiences, the typical narrative includes some form of campus tour, poking heads into active lecture halls, and the simultaneous intimidation and awe ignited at the sight of each swarm of college students. Diverting only slightly from the archetypal open day, my most memorable visit slotted ‘accidentally attending a nude life drawing class’ into the schedule. I have a vague memory from some years ago of a friend telling me that after about half an hour at a nudist beach you become desensitised to the nakedness of the bodies surrounding you. At sixteen, staring at the body in front of me, I wasn’t so sure that this would be the case.

Still flirting with the idea of a fine art degree, a school I had set my prospects on was hosting a range of free classes during their open day in hopes of enticing us into sending our portfolios their way. The one that caught my attention had been their life drawing session. The practice of life drawing was no new concept to me. A survivor of Junior Cert Art and a prospective victim of its Leaving Cert successor, life drawing was something I had grown used to and really loved. The layout of the studio was not unlike those I had been in before, if only furnished with more professional materials. We were greeted by a circle of soft wooden easels displaying vast, blank sheets, each supplied with a selection of jagged-edged charcoals. Our model, an older man, had been sitting quietly in the corner until we took our positions. As he stepped into the centre of the circle, I remember a vague horror washing over me as he began to undress. My friends and I shot each other rapid, panicked looks: if there was a memo, we had missed it. However, fuelled by a characteristic teen anxiousness at the thought of disrupting the class, and being more shocked by than opposed to the practice, we remained and began to sketch.

No longer a deer in the headlights, the familiar practice soon took over. An art teacher had once told me his goal was never to teach us how to draw, but how to see; once you knew how to see, the drawing followed on its own. I found this to be particularly true in the midst of the class. As the hour went on, the socialised awkwardness surrounding this naked form fell away. I no longer saw a naked body that shocked me, but a corporeal form to study and an unfeigned emotion to capture. I attempted to represent with accuracy the silhouette of each muscle, marking where the light hit and the shade fell. I traced the wrinkles of his draped skin and the veins that patterned his hands and arms. The sunspots and moles, the peaks and valleys of each rib thinly veiled by ageing skin. There was a quiet pride, a nonchalant confidence about his contrapposto stance calling to be captured with each marking.

The dynamic of a nude life drawing class was not anything I had considered before. There are poignantly few settings in life in which

one stands undressed in front of a room of complete strangers. For a moment in time, social norms and conventions slip away in the name of artistic investigation. The power relations are delicate and sacred: the model, vulnerable in their exposure amongst this room of anonymous others, must trust these total strangers to act with respect and decorum. Conversely, it is only by the presence of the model that this room of artists are permitted to further their craft. They examine with unmatched intensity, tending to each detail with such care, temporarily adorning their subject with the attention reserved typically for the loved and the famed. When the session is over, and the mist lifted, what documentation exists of this brief moment in history is a collection of works capturing one subject from all angles, unique in their execution but united in subject. Diverse in approach, but all reaching towards the same honest expression.

Dr Beth A. Eck classifies four frames under which we view the nude image in society: As information, as pornography, as the commodified image, and as art. We all, if largely unconsciously, enforce such separated categories upon this same basic form within our minds and as such attach a distinct meaning to each. Outside of the imagery we assess and analyse, the concept of being unclothed ourselves often sparks feelings of fear and shame. The artistic frame forges a unique space for the nude in society, one of praise and appreciation for the human form. As Kenneth Clarke notes in Thenude:Astudyinideal form , “To be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word ‘nude’, on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone”. He distinguishes how the nude projects “not a huddled and defenceless body” but a “balanced, prosperous and confident body”.

“The nude offers us a space in which to consider and appreciate the body we inhabit as a thing in itself, beyond the traditional narratives that dominate its discourse in society.”

This distinct space in society carved out for the nude of art is undeniable. These nudes are the only case of such nakedness uncensored in social media posting. Where other than a gallery exhibition would nudity be discussed so openly between parent and child, without a trace of shame or awkwardness and instead filled with inquisitive curiosity? Being such an expressive form, the nude in art allows for

the communication of themes of all kinds, not singularly the erotic connotations attached to the naked body by the mass media. Much like the process of life drawing, where dominant societal narratives are left aside, the viewing of the artistic nude invites us to do the same. The nude offers us a space in which to consider and appreciate the body we inhabit as a thing in itself, beyond the traditional narratives that dominate its discourse in society. The artistic nude shows us that the body, an imperative of life so often concealed with a criminal’s skill, exists outside the dichotomy of the sexual or the shameful. The body we so often deny is, in truth, the worthiest subject an artist’s meticulous, detailed study. It is a conveyor of emotion and deeper complexity. It is something to be carried with the pride of the nude and not the remorse of the naked.

I cannot pretend this deep appreciation had hit me as soon as I left the life drawing class. In a brief conversation before our exit, the model noted how the job had been so beneficial to the confidence he had in his body image. I understood him fully. Until I began drawing myself, though clothed unlike this model, the longest I had spent analysing my body had been staring in the mirror, narrated by the critical voice of my inner monologue. These thoughts were informed by what I thought a body should be, every body that had existed before my own as my reference. When drawing from life, there is only once reference: that that exists before you. The image is formed not through comparison to an outside ideal or an attempt to work within a set tradition, but through candid depiction. The beauty is found in honouring the subject exactly as they are, with capturing such a reality a marker of the highest of skill. Accurate self-representation was what made each sketch a drawing of me and not merely an unskilled nod to a stock idea of the human form. When the bend of my nose became a detail for honest representation, my proportions becoming what made the piece interesting and real, I could feel the small but distinct shift in my self-perception. The narrator of my image could be momentarily switched from my unhelpful, unrelenting thoughts to the careful, curious markings of my pencil.

Each time I bring up this story, it is met with the same wide-eyed shock as met me at sixteen and living in that moment. I, each time I recite the tale, am equally overcome with the giddy awkwardness of recalling my encounter with the nude form as if I were back in that studio, charcoal in hand. Such reactions are a testament to our enduring conceptions surrounding the naked body. If we were to take anything away from the practice of life drawing or embrace the artist’s values of the nude over solely the naked, we could reframe our relationships to our own fundamental forms. If we were to appreciate each detail with an artist’s eye and acknowledge each quirk as a marker of our own wholeness, such a lens could recentre the place of the body in our lives to one of pride, of confidence, and of unashamed self-love.

Ripley Sheridan was staying late in the archives again, cleaning film slides.

It was tedious, but better than prying rusted staples out of yellowed paper. The thick, grey plastic of film slides was harder to tear on accident. Keep the gloves on, don’t press on the film too hard with the Q-tip, and just make sure you aren’t archiving eight duplicates. Oh, and always take a chance to hold them up to the light. The colours were always brighter than life.

Ripley’s own admiration for the archive’s collections aside, slides were too small to fit the bill of exhibit material. That honour was reserved for the photos and sketches displayed in the lobby. It was the first exhibit Ripley had worked on when they started working at the Reyna Archeion Art and Design Archives, RAADA for short, although she preferred Reyna. They didn’t teach you that archives manifested as people in the postgrad, but hell, it was a welcome surprise.

The first time Ripley had seen Reyna, they were running late. They were weaving through the families lingering in the lobby who filled up the empty space between the glass exhibit cases and stark walls. Reyna’s eyes had pinned Ripley in the crowd like a taxidermist would a butterfly, demanding that Ripley stare back. (But maybe that demand was just their own interest in the archive.)

The second thing Ripley noticed was that Reyna was short – sure, RAADA only had a handful of small collections at the archive. Then Ripley noticed that Reyna wore black every day, that she took two sugars in her tea, and got every 80s pop culture reference (blame the fashion designer who had donated half her room to RAADA).

And she was beautiful.

It was strange to start seeing Reyna, but she wasn’t just something to look at. When Ripley wasn’t holding back a zealous researcher from getting fingerprints all over the photographs, the two of them talked as Ripley worked.

Following a lull in conversation, Ripley scrambled for something to talk about. They opened a file of old letters. Anxiety stabbed their chest at the thought of working alone. They blurted out: ‘Any hobbies?’ They may as well have asked if she went out on the town much. But the manifestation of the archive tilted her head.

‘Oh, collecting knick-knacks at garage sales, mostly.’

‘What kind?’ they asked. They had no idea Reyna could leave at all - they filed that away as a topic of conversation for later.

‘Oh, you know, anything really. I’m fond of old family photos though.’

‘I mean, you are an archive, but everything here is given by choice so - er -’

‘Ah well I’ve never found it odd to pick it up. I suppose it’s just that every once in a while Luck guides me to a very old one, one where they’re supposed to be staring ahead stock still to avoid blurring, but they’ve moved anyway. I have to wonder… you know, everything in here was made with such creative intent. The accidents are just as beautiful. They’re a fragment of life that I had the good fortune to come across. It would be a disservice for them to just go into the bin.’

‘I suppose.’

‘And surely your one wouldn’t imagine his family would donate everything and you would be reading his letters down the line?’ she said, tapping a nail on the letter at top of the pile from the

file. It was a letter from an artist to a friend, describing his ideas for a new piece based on his past, all the mistakes he had made and the lives he had ruined. He ended it with ‘thank you for the well wishes I send you and the husband the same, and let me know if you need help moving house’. It jarred, and yet it existed anyway, and Ripley noted it in their archive spreadsheet.

‘I… yeah, I suppose.’

‘Oh!’ Reyna’s exclamation caused Ripley’s head to snap up. ‘Your tie has been reversed all day! I should have caught that before the staff meeting.’

‘Oh, oh thank you,’ they managed as Reyna leaned in close. She paused. She gave them a peck on the cheek.

‘You are the first one who talks, and doesn’t just look.’

There was always something new to uncover. One of their acquisitions was some ancient book, donated after the owner’s death. Ripley had planted their hands on their hips one morning and determined to haul it out for a look. They could see why it had been neglected - its box was as wide as their chest, and the Head Librarian had to carry the other end to set it on the table. The tome inside was practically ancient, but hadn’t fallen to bits. Impressive. Impressive, too, was the rot along the sides of the pages.

Reyna handed Ripley a pair of gloves. ‘To keep the rot from staining you – otherwise the archives would be with you everywhere.’

But the archives were already everywhere. Ripley had stopped using plastic bags because all they could feel was the grime of decaying plastic page protectors holding aged sketches. They held their photographs carefully, making sure their skin’s natural oils didn’t stain its surface forever. It would be unfortunate if Reyna’s face got hidden under their fingerprint.

As the sun set on another day, Ripley soaked in the hush of the archives and the shush of paper sliding across itself and piling up. A flash, snap, and whirr rang out behind them.

Reyna’s camera was one of those disposable ones that weighed nothing, but got you a heavy stack of photos when you had them developed.

Ripley clicked their tongue. ‘I didn’t agree to be part of your archives.’ She smiled at them with perfectly straight teeth.

‘At least,’ they said, pretending that her smile hadn’t sent a thrill through their chest. ‘Let me see how I look before you pin it on the break room’s fridge, or have someone write a blog post about, I don’t know, a day in the life of a Head Archivist.’

‘Maybe I just want to keep you for myself.’

Their heart fluttered. Coming from her lips, they couldn’t complain. ‘I should be so lucky.’

Years passed and photos piled up. The sun’s rays captured while burning through the lobby windows. The paperboard of damaged acid-free boxes feathering out from itself. Ripley sitting and Reyna, close enough to the camera’s lens that she took up half the frame, tall for the first time in her life. She had been dashing to sit before the timer went off, blurred forever. Others from that day had them sitting side-by-side, pristinely, but this one was beautiful.

Reyna kept the photos in a handmade archival quality box, the order for it placed by Ripley themselves. Reyna showed them where she kept it, in one of the metal filing cabinets in their very own office that always stuck when they tried to open it on their own. Ripley knew that nothing lived forever, hell, death was what made the archives. At least Reyna held the fragments of life close.

In the village, I stand with open arms. You are safe in your skin, Eyes reflecting a myriad of moments From your time in the country. Our minds were warm And soft with youthful notions, As one ripens in the heat Of a nurtured garden. Hands settle in earth, Your absence residing In silt and clay.

I make it known to you, Among the moss and lichen Your carmine cheeks flaring, Spitting ash onto bark.

We thought we were the first ones who fucked up their lives. We thought we were the first ones to discover the consequences of our actions.

We thought we were the first ones to have these thoughts.

The first ones to make mistakes. The only ones to exist.

We thought discussing Dostoyevsky was worth something, and drunk nonsensical deep talks.

We thought being stuck in this limbo was enough for us and talking about it, about us, was useless, as it was only a label, a social construct for an experience that had saved our lives.

Turned out we were both just too scared to say it out loud. Turned out we were the first ones who made each other feel understood.

ART by Kate Moloney

ART by Kate Moloney

“I never did drugs, I did love”- Jeanette Winterson

It’s 7:25 on a Wednesday morning. Autumn air glides through the window, which is wedged open by a copy of The Journals of Sylvia Plath (unabridged). It’s your run-of-the-mill student accommodation bedroom; a small double bed shoved against a grey wall, a sink in one corner and a mirror in the other, bins, a coat rack, and not a whole lot of floor space in between. The walls are peeling, the room is drab. Someone has hung a garland of pastel tissue-paper flowers across the ceiling.

Two people lie together in the bed. A soft caress on their skin, the breeze loosens their hearts a little. Ada nudges Krystina awake with a tentative kiss and she groans sleepily in reply. They don’t have class until late in the afternoon.

Ada and Krystina are “just friends”, the way that plenty of people say it and don’t mean it. They are “just friends”, in the way that they are too scared to call it anything else. They like to be close, but they aren’t quite ready to acknowledge the reality of what that closeness might mean. Or at least, Krystina isn’t.

It had started out innocently enough; they’d met in the laundry

room of all places. The whirring of the machines and the bright white light overhead made them feel like they were outside of time and space. Nobody else was there, and they’d wound up talking for ages. As they waited for their clothes to turn from dirty and dry, to soaking wet, to clean and dry, the loads that they carried inside of them also began to dance dizzily into a strange new place.

By Deia Leykind ILLUSTRATION by Kate MoloneyThe conversation was suitably polite and awkward at the beginning; where are you from, what course are you studying, how are you liking Dublin? Krystina offered laughter to Ada’s customary sarcastic pokes, and soon everything was funny. It wasn’t that fake, I’ve-just-met-you-and-don’t-quite-know-to-actaround-you-yet laughter that is often coaxed out of someone’s throat to fill awkward silences. It was a real, genuine laughter, that comes only when you are ready to really look at a person and listen to what they are saying - and still choose to laugh anyway. Ada would wonder about this a lot; how had it come to be that she felt so comfortable around Krystina so quickly, when she found it hard to feel at ease around other people that she’d known for years. And her mind would always circle back to the same answer; she felt that Krystina was listening to her, and this was a surprisingly foreign feeling. It was nice. As she returned to her room, she was followed by a strong sense that something extraordinary had just happened to her, but she couldn’t place it. After all, had anything really happened?

But then they began to text. Once, twice, three, four, five times a day, and then incessantly. It wasn’t at all like those sorts of things you see in the movies, when two people meet by chance, and are quickly surprised to find out how well they understand each other, like no one else ever has before. And then they fell in love. Ada and Krystina didn’t understand each other a lot of the time. Ada never felt like she quite knew what Krystina was thinking. But she felt close, very close. Or at least, that’s how she wanted to feel. And she fell in love, despite it all.

It was the kind of thing where, when she looked into Krystina’s eyes, she would stare right back, every time. Ada thought of Krystina’s smile as she got ready for bed, the way it lit her face into an expression of twinkling bashfulness. A little kid who knew they’d done something wrong, but also knew that they’d get away with it anyway. Seeing it, even just in her head, made Ada smile too. When they had work to do, they’d hold hands under the desk, and at night they’d lace themselves carefully together, reconfiguring their sharp edges of spindly bones and knobbly knees, so that they might melt together into one unified shape of softness and sweetness. Two paper dolls folding back onto themselves so that they become one.

And Krystina’s smell… Ada had failed to notice it the first time she met her, and then, suddenly, it was everywhere! She began to compulsively spray Krystina’s perfume all over herself, too; without it, she felt all alone. Both of their skin dripped the scent of falling summer petals, now, on cold autumn mornings.

Ada fell for Krystina, the way she fell away from herself. There were times when Ada thought she was Krystina. Longing can do powerful things.

Could Ada see what was happening, there on that crisp yet sweet Autumn morning? Did she know that she was falling? But the falling was such a blur and it would be in vain to pretend that she had any semblance of control over it. She found herself in the air and thought, well, I suppose I’m in the air now. It sounds foolish, but for a moment she really forgot that the ground existed. She looked up at the birds and thought, maybe I can live here. She was a child who had just learnt to ride a bike for the first time, without daddy’s hand pressing into her shoulder. She had just tasted her first chocolate, not the bitterness of dark chocolate, but the silky sweetness of milk. Don’t we all try to shovel in as much as we can before we learn the consequences, the very poison we’ve just put into our stomach? For a split second it felt so fucking good, didn’t it?

December 19th is Ada’s birthday. Krystina says she wants to bake her a cake. I’ll pipe pink and red roses on it, our favourites. By December 19th it will be over. Ada will learn that the day you start falling you make a promise, you take a pledge; that another day you will hit the ground, hard. Cold tarmac coming to meet a bruised cheek, it’s the fall of Icarus. It’s being too enraptured by the sun to remember that the stormy sea lies just below. Legs flailing hopelessly, your world is turned upside down, while the ploughman continues steadily to pull his horse and cart beside you. Icarus spattered away in the Springtime, but Ada will be greeted only with an endless stretch of winter. She and her mother will blow out her twenty candles alone and the falling snow in the garden will confirm that everything is blank. Krystina had made stars burst in the blackest parts of her brain. Ada will find it really hard to get back up without those stars.

But as empty as Ada is going to feel in those days, she will be comforted by the knowledge that something had been there, once. Maybe she will love someone else someday, but she will not love them in the same way, that is to say, without knowing what it is to fall. Loving Krystina will feel like forever ago. She will still love her.

ILLUSTRATION

by Kate Moloney

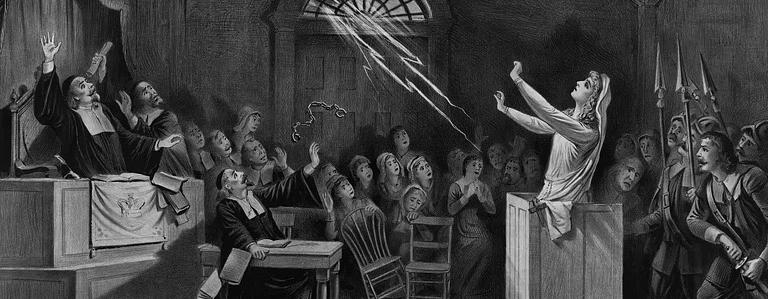

Nudity has, rightfully, lost most of its shock factor. In a post-Saltburn world, there is little a naked body can do on screen to alarm audiences. Yet, this somehow hasn’t extended to the world of theatre. Though there are countless examples of high-profile actors baring it all on the stage; including Sienna Miller, Kit Harrington, Daniel Radcliffe, Ian McKellen and Jude Law, the news that some big shot is going full-frontal continues to be needlessly plastered on tabloid covers. When it comes to theatre, we can barely deal with nakedness in the flesh let alone sex. I’ve never seen a sex scene on the stage and a big part of me has no interest in ever seeing one. Why are we so prudish about sex on stage? Is it possible to have a tasteful sex scene in a play?

The word that jumped into my mind when I started to think about the negative sides of sex scenes in the theatre was “exploitative”. People act as if actors going nude as part of a play is an open invitation to invade their privacy. In 2023, The Daily Mail published nude photos taken by an audience member of actor James Norton in A Little Life on the West End. This provoked public outcry and even encouraged the West End to consider banning phones from the theatre altogether. Similarly, Jesse Williams had illicit photos leaked from his performance in Take Me Out on Broadway, even after audiences had their phones sealed in magnetic pouches. What I find more interesting than the obvious immaturity of certain audience members is the sexualised reaction that the nude images had in the public. Both Norton and Williams’ images were doused with sexual overtones, with people, including the Huffington Post, tweeting gifs and memes of them trying to cool themselves down.

However, Norton was nude for A Little Life, in which his character Jude is repeatedly sexually assaulted, abused, and shamed. There is nothing sexy about Norton’s nudity as Jude. In Norton’s own words to BBC Radio 4; “it’s shaming, you know, I lie on the floor naked being kicked and spat on – and it doesn’t get much more degrading than that.” Jude’s nudity is an integral part of his intense vulnerability and the deeply traumatic events that occur throughout his lifetime. Looking at all the thirst tweets that arose from these images is downright shameful considering the context of the play. This nudity is not a display of Norton, but meant as an uncomfortable interrogation of abused and inconsolable bodies.

Nudity is often used as an expression of vulnerability on the stage. Experiencing nudity as an audience member can be slightly uncomfortable. Not only because you’re alongside hundreds of other audience members turned voyeurs but because it’s a real human body. It moves, and makes noises, it reacts to the climate around it, and it’s primordial. All bodies are beautiful, but equally all bodies are kind of gross. The brutish fact of flesh is a reminder of all the weird skin, bones and meat that add up to who you are. Nudity as a costume represents all the tenderness and all the helplessness of humanity. The symbolism of Norton’s nudity gets lost when it enters the two-dimensional world of the internet. What was once about vulnerability is now solely about the fact that he’s naked. The mediation of the fixed image makes the spectator believe they have some right to sexualisation and commentary. But why?

Part of me blames pornography: any images or films of naked bodies are associated (even subconsciously) with the internet’s most popular product. When I was doing research on sex scenes in the theatre I had to change my wording about four times because all that would come up on google was porn. We can even see the direct impact that porn has had on on-screen sex scenes to move away from overtly sexualised images. The rise in co-ordinated and often informative sex scenes in TV shows such as Bridgerton, Sex Education and Normal People which intend to promote consensual and realistic sex lives can be seen as a response to the unrealistic and often dangerous sex that is popular in pornography. This is undeniably also a result of the MeToo Movement.

Intimacy co-ordinators are the key to making actors feel comfortable on set after decades of abusive workspaces. We have had a cultural shift in our use of sex on the screen. We understand more and more that sex is important to developing meaningful storylines but it can also be an exploitative experience for the actors involved. Balancing an interest in the value of meaningful sex as a part of art and the rights of the actor has changed the way that we film and watch sex.

Still, this relationship with meaningful sex doesn’t translate well onto the stage. Andrew Scott spoke to the Guardian in February about his sex scene in the one-man production of Uncle Vanya that sold out the National Theatre in 2023. He says: “I think there’s something about the fact that it’s just one actor that disables that discomfort – you’re not concerned, worried or embarrassed for them.” Scott disarms the audience and prevents his own embarrassment by focusing on the comedic element. In some ways, he’s trying to distract from the sex itself. Scott argues that its implicity elicits an imaginative reaction from the audience, which privatizes the scene to the comfort of our own heads. Comparatively, Andrew Haigh, director of All of Us Strangers, speaks about Scott and Mescals’ sex scenes as being “intimate” rather than explicit. Speaking to Vanity Fair he explains “I really wanted to feel the subjective nature of having sex and what it feels like—the nervousness and the excitement and the physical sensation of being touched by someone else, and what that does to you.” Though there’s also an audience in the cinema, there’s no need for Scott to laugh off sex on the screen. In fact these scenes’ exposing nature is part of what makes them so moving. Showing that there’s something about filming a scene that feels less concerning and embarrassing than if it were happening right in front of you.

Is the lack of intimacy on stage the root of the issue? How can you capture that tenderness without it being uncomfortable or voyeuristic? With no tasteful camera angles or music scores, sex in the theatre might be reduced to something graphic and awkward. Films and TV shows rarely show sex without trying to recreate the emotion of sex in some other way. Even refreshingly honest shows like Sex Education cleverly capture the awkwardness of being a teenager to emotionally drive their sex scenes. Maybe sex on the stage is only ever funny or provocative without being tender. Andrew Scott might be right to say that the audience needs to be disarmed or charmed by something comedic to successfully include sex in a production. The relationship between the stage and the audience could be too close for us to engage with so much simulated intimacy.

I can’t help but think that because sex is such an integral part of human experience, it should be explored in an art form that is all about human relationships. Currently, theatre incorporates sex by encouraging the audience’s imagination to take part. This is probably better than trying and failing to showcase intimacy through sex. For me, I think we haven’t found a way to use sex as an effective signifier in theatre quite yet. Where nakedness can be used symbolically, I think a sex scene on the stage would only be about people having sex on the stage. I’d be curious now to see a tasteful sex scene in the theatre, and how it can serve a play. I’m just stuck on whether it would be really moving, or a little too weird.

WORDS by Éle Ní Chonbhuí IMAGE from Oh!Calcutta! (1969)I thought to pick the flower of forgetting for myself, but I found it already growing in his heart. Since the body was forgotten by the one who promised to come, my only thought is wondering whether it even exists.

The Ink Dark Moon (1988) by Jane Hirshfield is a collection of poetry from 9th-11th century Japan. The poems were written by two female poets and discuss sex, romance, and other themes.

We may think that our contemporary culture of romance, sexual freedom, and Instagram poetry are new realities of human experience. Unfortunately for all who came before us, our generation didn’t invent emotional manipulation, unrequited love, or toxic relationships. Reassuringly for those of us alive and love-troubled today, these phenomena have been around for millennia! Sweet relief– it’s not just you, it’s the human condition!

We tend to idealise sexual and emotional freedom as modern day achievements. In many ways they are. While the ability of your coursemate to openly profess their feelings to you in the Pav, then awkwardly pretend not to know you in the next tutorial, may feel like an archaic nightmare, people will convince you oh darling it’s a contemporary privilege! I’m here to reassure you that they are incorrect. Disastrous Trinity moves aside, modern-day romance and its problematics aren’t new. For thousands of years, human civilization has been plagued by the woes and troubles of love. The sneaky link is oh so not modern, I just wonder what we did to deserve the cultural degradation from Kokinshu love poetry to cringey dms.

Japan’s Heian period (794 - 1185) was a Golden Age of Japanese literary achievement and appreciation, a time when artistic refinement and poetic capability accounted for your status at court. The central role of the arts in daily life made poetry a critical component of the aristocratic culture of the Heian court. Romantic verse was entangled in the etiquette of courtship, and poetry was intrinsic to sexual encounters. It was also a literary era where women were recognised as the predominant geniuses, blending romantic, sometimes erotic, longing with Buddhist contemplation.

Ink Dark Moon is a relatively new volume that compiles the poetry of two great female figures of Heian poetry, Ono no Komachi and Izumi Shikibu. The introduction reads that “their brief poems serve as small but utterly clear windows into those concerns of heart and mind that persist unchanged from culture to culture and from millennium to millennium.”

The poetic style of personal expressiveness and emotional depth was facilitated through the philosophical and technical excellence of Ono no Komachi. Renowned for her unusual beauty, Komachi was writing in the 9th century and her poems are better Instagram

poetry than anything you’ll find on your ‘for you page’ today. Put them in a slideshow with some depressing cinematic classical music, and the girlies on Tiktok at 2am will find them. Izumi Shikibu was writing during the late 10th and early 11th century, and builds on this tradition of simple, eerie, and heart wrenching verse. Both were known for their numerous and dedicated lovers (historic proof enough they never lived in Dublin).

The preface to the Kokinshu (c. 905), a [explain form], explains that:

“Because people experience many different phenomena in this world, they express that which they think and feel in their hearts in terms of all that they see and hear. A nightingale singing among the blossoms, the voice of a pond-dwelling frog — listening to these, what living being would not respond with his own poem?”

I can only hope then that our love troubles are due not to a shift in how humans think and feel about romance, but rather to the changes in what we are seeing and hearing in 2024.

In this piece, I share some of my favourite poetry written by Ono no

Komachi and Izumi Shikibu. I follow each piece with my far less beautiful parodies. I hope this serves to remind us of how much we have in common with women on the other side of the world 1,200 years ago, but also illustrate how far we’ve truly fallen.

Women writers of Heian poetry speak with such emotional truth and modern relevance, that we feel connected to them across thousands of years. And while we can admit our fortune for the levels of romantic freedom and choice we’ve won back, let’s stay vigilant and critical of what continues to lack. Even with dating apps, history finds a way to repeat itself.

In this world love has no color— yet how deeply my body is stained by yours.

In this world love has no colour— yet how brightly the colour of your Lost Mary shines in her hand.

To a man who wrote requesting an answer I think I will not go out again on your drifting boat that floats in any direction without ever setting a course.

I think I will not go for a thirteenth coffee, your bleeper bike where none should be, no more than 45 minutes entertainment for you is me.

Undisturbed, my garden fills with summer growth— how I wish for one who would push the deep grass aside.

Undisturbed, my mind maintains blissful clarity– how I wish for one who would respond in less than 72 hours.

Tonight, with no one to wait for, why do my thoughts deepen along with the twilight?

Tonight, with no one I desire in the Pav,why do I fight my way to the bar for a can of X Lite?

What is the use of cherishing life in spring? Its flowers only shackle us to this world.

What is the use in waiting for miracles? Lidl tulips only cost three euros.

A man who hadn’t visited for a long time finally came, but then didn’t return

If you had only stayed away when I first missed you, I might have forgotten by now!

If you had only refrained from swiping up on my Instagram story, while I was slaying my Erasmus, I might have been happy by now!

If the only one I’ve waited for came now, what should I do? This morning’s garden filled with snow is far too lovely for footsteps to mar.

If the STEM boy in the Ussher asks me for a calculator, will my long denim skirt give me away? Will my skinny scarf convey to him, I only love the ones who play?

Did he appear because I fell asleep thinking of him?

If only I’d known I was dreaming, I’d never have wakened.

Did they appear because my Snap maps were turned on? If only I’d known they loved Pitbull, I would have headed to Coppers sooner.

Night deepens with the sound of a calling deer, and I hear my own one-sided love.

Night deepens with the sound of a DUDJ, and I hear my Revolut nearing zero.

The cicadas sing in the twilight of my mountain village— tonight, no one will visit save the wind.

The keycards sing in Kinsella Hall, no one comforts me save my Class Rep with an extension.

The seaweed gatherer’s weary feet keep coming back to my shore. Doesn’t he know there’s no harvest for him in this uncaring bay?

The moh from second year lingers about. Doesn’t he know the unspoken prenup: he gets the gym, I get the library?

Those gifts you left have become my enemies: without them there might have been a moment’s forgetting.

Those playlists that I made you have become my enemies: if only I had bad music taste, I could delete them and forget.

This pine tree by the rock must have its memories too: after a thousand years, see how its branches lean towards the ground.

These fourth-years remember and learned: see how they’re all single, and content in their defeat.

Our best filmmakers - Scorcese, Tarantino, Spielberg - are heading into their twilight years, so the question arises: who are going to be the big filmmakers of our generation? If you were to ask any film student, they would know the name Emerald Fennell. Her debut feature Promising Young Woman (2020) garnered glowing reviews, as well as an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. She followed this with perhaps the one of the most talked about movies of last year, Saltburn (2023). With this rise in fame, Fennell has been the ire of online misogyny like many a woman in the film industry. Fans have flocked to defend her, even sparking articles from the likes of Euronews: ‘Defending ‘Saltburn’: Is the criticism of director Emerald Fennell sexist?’ However, I disagree with the article’s idea that “while those three male directors [Tarantino, Fincher and Nolan] are praised for their gorgeous cinematography despite depthless plots, Fennell has been punished. It reeks of a double standard.” In general film critics have been kind to Fennell, with both of her films gaining largely positive reviews. On Rotten Tomatoes, Promising Young Woman has a whopping 90% critic’s score and Saltburn has a favourable 71%.

To discuss Fennell, it’s important to gain insight into her background. She has had a privileged upbringing - and not just by being white and middle class, but extravagance to the point where her eighteenth birthday was written about in Tatler. Fennell’s father is renowned jeweller Theo Fennell, whose clients have included Elton John and Madonna. In the case of someone like Fennell who comes from such a privileged background, this has given her greater access than the vast majority of people to the creative industry. This access to the industry is a symptom of our capitalist society. There’s ample evidence of the material benefits of wealth, including access to opportunities like education. However, further than that is the social capital that a wealthy background brings, as is excellently described in the book The Class Ceiling: Why it Pays to be Privileged. There’s a way of speaking with highbrow wit and casual intelligence that allows those with wealth to “fit in.” This is evidenced by a quick look at the film industry and seeing those with upbringings even wealthier than Fennell’s, from director Maggie Gyllenhaal to film producer Megan Ellison to actress Cara Delevingne.

Personal background and experiences inform the perspective a person brings to their art. In an interview with NME, Fennell says, “Saltburn is me trying to come to terms with what an embarrassing person I am.” Furthermore, in an interview with Hunger in response to a question about drawing on her own experiences when writing, she answers:

“People want to know thematically what you’re talking about. But actually, if it comes from inside you, you’re not thinking in that way, really.”

As part of the white British elite, Fennell is complicit in upholding the

systems of oppression in today’s world. However, her films indicate a nescience towards taking any form of accountability. She is certainly aware of the role of privilege in society, admitting that “being rich and living in London gives you a deeply unfair advantage.” Yet in Saltburn she refuses to go any further; there’s an almost unwillingness to completely denounce extravagant wealth. This is not about painting Fennell as some cartoonish aristocratic villain, but indeed if any of us wish to change the way the world works, we must attempt to dissect our own complicity in upholding systems of oppression. It is only then can we begin to gain a full understanding of the societal issues we face.

It’s understandable why Fennell’s movies have captured the attention of audiences, particularly young adults. They feature celebrities like comedian Bo Burnham and heartthrob Jacob Elordi, as well as some of our most established and well-known actors like Carey Mulligan and Richard E. Grant. Her movies are littered with shots that are saturated with colour similar to Sam Levinson’s hit show Euphoria, providing an aesthetic that can be easily screenshotted and posted online to rack up likes. Fennell is also well aware of our present day politics and the topics which capture the attention of the cultural zeitgeist. Her two films hit on subjects which have a mainstay in online discourse, namely feminism and class, in Promising Young Woman and Saltburn respectively. While many adore Fennell, her movies echo the views of wealthy white liberals, willing to impart surface-level insights into the current capitalistic and patriarchal world that we live in, but not to meaningfully challenge or reimagine these systems. She provides endings which appear to be subversive, but once scrutinised, fall apart at the seams.

In Fennell’s debut feature Promising Young Woman, a film marketed as a rape-revenge thriller, Cassie Thomas (Carey Mulligan), a thirtyyear-old medical school dropout, begins conconcting a revenge plan for her best friend Nina following her sexual assault and subsequent suicide. Cassie frequently pretends to be drunk at bars. When men approach her and bring her home to have sex, she drops the act, and the idea of revenge here is a telling-off to the men to make them realise they are taking advantage of her. It’s a very naive idea to depict their advances on a drunk Cassie as an unknowing mistake; a number of these men would be aware of their actions and in real life would likely become violent. Cassie begins to confront the people who were in her mind complicit in Nina’s suicide, from a classmate who denied the rape to the college dean who dismissed Nina’s case to the lawyer who defended the rapist. In the end, they all learn their lesson, but the revenge enacted on them is considerably tame compared to the trauma that Nina would have experienced. Fennell is satisfied with the idea that learning your lesson is enough of a punishment; there’s seemingly no “bad” people in Promising Young Woman besides Nina’s rapist. The punishment here involves Cassie being murdered at his hands in the film, but in a twist it’s revealed that this was her plan. The rapist is subsequently arrested by police in the closing scene. If Fennell’s intention here was to provide catharsis to the audience and

victims of sexual assault that the rapist will ultimately be punished, it completely fails to do so - infamously, the police and law have an extremely poor record of successfully convicting perpetrators of such crimes. On the other hand, if her intention was to point this out, there is still far too much gratuitous violence as we bear witness to a rapist brutally murdering a woman. Either way, it is a very irresponsible and smug ending, which fails to provide catharsis to victims, add nuanced discussion to the issues of the patriarchy, or help change the minds of those who are ignorant to the challenges that women face. This reflects the criticisms of white feminism today, viewing the experience of womanhood from a narrow viewpoint.

In an interview with Roger Ebert, Fennell speaks about society’s view of women today and how we all suffer under the patriarchy. In response to questions about how alcohol excuses bad behaviour, Fennell responds:

“That’s what this film is about. It’s not about traditional predators. It’s just about good people who’ve just, they’ve been given a loophole by the culture and so they just don’t think too deeply about the loophole. They just don’t look at it”.

This offers a level of insight into Fennell’s understanding of the role of the patriarchy in society. It’s far easier to wave the hand at society as a whole but then just skirt around any form of personal accountability.

“None of these people thinks of themselves as a bad person. It was the same with Promising Young Woman. It’s not interesting for me to make things that make moral judgments about people - all I’m interested in doing is understanding”.

-Fennell on Saltburn in an interview with Polygon

We shouldn’t be too quick to praise films that delve into topics which have been in the mainstream of cultural discourse for decades, and which do so without any form of nuanced discussion. Indeed, both of Fennell’s films generally like to point to societal issues, but fail to actually challenge these issues through interrogating the reasons they

occur or analysing those who compound these issues. Both of her films act as awareness-building exercises: yes the patriarchy is bad, and yes, the concepts of social class are ridiculous. Yet the buck stops at awareness-building, and if a film wishes to actually have any wider social impact we need to be willing to be more critical. In the same Polygon interview, Fennell states,

“It’s really about having sympathy with everyone, always.”

But do those with extravagant wealth - for example, Elon Musk, whose family propped him up with their wealth that was procured via exploiting others in their African emerald mines - deserve our sympathy? While we are all a product of our environment, Fennell doesn’t know how to hold anyone culpable for the production of that environment - including the wealthy, who more often than not have exploited others to gain wealth and in doing so further compounded class issues and our capitalist system. It’s not a leap to say her background has informed these views, with Fennell herself part of this wealthy group.

In Saltburn, the smash hit of last year, Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) attends Oxford University, and due to his lack of knowledge of upperclass mannerisms, fails to fit in. Oliver lies to Felix (Jacob Elordi) and also to the audience, imagining a new backstory for himself with parents who abuse substances and have mental health issues, in order to gain sympathy. Felix invites Oliver to his manor, the eponymous Saltburn, and a summer filled with lust, desire and dizzying wealth ensues. As the summer reaches its end, Felix and his family members begin succumbing to various tragic accidents. However, in a twist, the incidents are all revealed to be planned. Unfortunately, it’s an ending that doesn’t fare much better than Promising Young Woman. The movie ends with a near indictment of the one primary character who is not from the British aristocratic elite, Oliver, who has typical middle-class parents with a detached house in an estate. In a similar fashion to The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), a film which touches on similar ideas but in a far more accomplished manner, Oliver is revealed to have been a crazed premeditated murderer masquerading as a sweet and kind-hearted individual. He has been

picking off the family one by one in order to seize the estate, dazzled by its extravagance. Fennell herself seems to be of the opinion that we all have desires to emulate the wealthy and privileged. She says, in response to Saltburn being an eat-the-rich film,

“I think I consider it more ‘Lick the rich, suck the rich, and then bite the rich, and then swallow them.’”

Her view of eating the rich means replacing the rich in their position. This narrow-minded perspective fails to recognise that many of us imagine worlds where vast excess and fortune, and strutting around in ridiculously sized manors, should be eradicated. Saltburn isn’t a sharp satire for those that want capitalism dismantled and a radical change in the way wealth is distributed. In Fennell’s own words:

“it’s absolutely a satire, but it’s also a satire of those of us who want in.”

Fennell represents the liberalism that spotlights the societal issues of today without contending with the solutions needed to rectify them.

Additionally, it should be stated that the popularity of Saltburn wasn’t due to its poor depictions of class, but rather its attempts to provoke the audience with scenes of a sexual nature. Our current generation is seemingly more open to the idea of sex than the act of sex itself. It’s easier to talk about sex now than it was in the past, but the minute any sex is shown on screen it becomes a driver of online discourse. The infamous scenes (such as Oliver licking Felix’s semen in a bathtub, and later fornicating with his grave) were in actuality tacky and gauche, having very little rhyme or reason past provoking a reaction. These scenes provide another addition to the superficial yet engaging elements which have catapulted Fennell’s movies into popular culture. Film has always had sex, so why have so many of us been fooled into incredulous gasps when it occurs in Saltburn? Maybe her supposedly subversive endings are actually quite simplistic, thus enabling her to reach a wider mainstream audience not accustomed to depictions of sex on screen?

Simply deeming all criticism of Fennell as misogynistic fails to engage with how we can produce better art. There is skill in her directing, but the foundations of her films and the script have been convoluted misfirings. She has created films that have captured the attention of our Tiktok-addled brains, but do little to coax audiences to delve below the glossy exterior. In an age where virtue signalling seems to be all the rage, we are often unwilling to denounce that building awareness around issues without any form of nuance does little to result in any form of action or positive societal change; it’s no wonder that Fennell’s movies have catapulted her to fame. Ultimately, I just wish that her movies were better.

WORDS

by William Reynolds

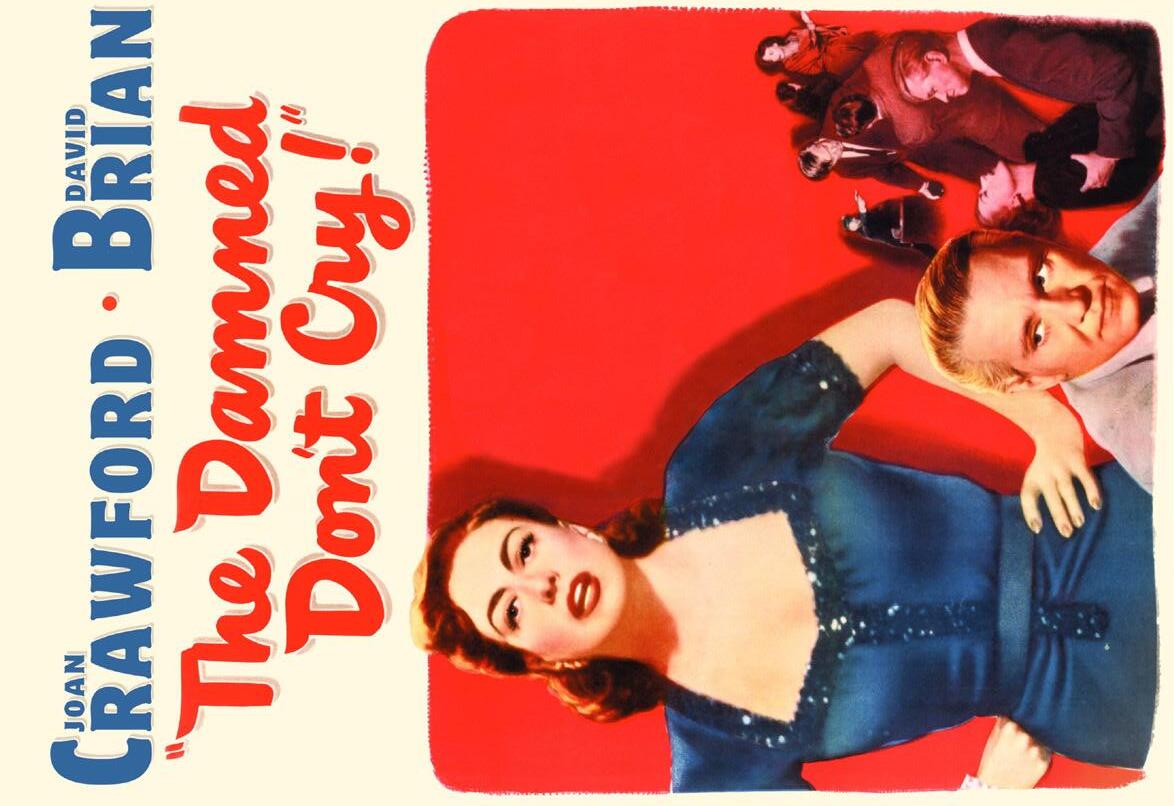

Sass Mouth Dames Film Club Brookes Hotel every Thursday in March

Tickets on Eventbrite from €11

Mother presents Cultúr Club National Museum of Ireland

Tickets on Evenbrite from €22.65

Disrupt Disability Arts Festival Project Arts Centre

Tickets online for variou s events, from Free-€16

19-7

Mother and Child Glass Mask Theatre

April

Dead Poets Society Screening in the lighthouse

National Gallery of Ireland

21 25

goi ng

Everyone and their mother has cooked some version of ‘Marry Me Chicken’. But what if you’re too young and broke for marriage? What if you’re simply dating someone new and want a way to get into bed with them? We at TN2 Food and Drink have your back. This recipe, which I have named Fuck Me Risotto, is a mushroom and leek risotto recipe that is sooo mouth wateringly delicious, it’s guaranteed that the person you’re making it for will want to have sex with you. It’s a buttery and umami rice dish, with a Japanese twist by using a miso broth instead of its usual chicken stock, and loads of salty parmesan and sweet leeks. While this recipe seems difficult and impressive, the technique is actually really easy! It just takes a bit of time to prepare, but that will only allow you to spend more time with your date. This recipe also includes white wine, which is a perfect opportunity to share a drink with your partner while you cook. Other flavours for cocktails that would pair with this dish would be a raspberry and mint gin bramble, a ginger whiskey sour, or perhaps a lemon drop martini. We also recommend having something similarly fruity, cold, and acidic for dessert, such as raspberry sorbet. You can also have some mint tea as a digestif, because if you do indeed make this on a date, you’ll want your stomach to be totally fine if you plan on partaking in bedroom activities. Instead of filling the void in your soul with instant ramen and one night stands, fill your stomach and heart with this beautiful risotto and meaningful sex.

Serves 3-4

Adapted from Jamie Oliver’s “Risotto Bianco”.

For the Stock:

700 mls/ 1 pint glass boiled water

2 tbsp miso paste

1 veggie/chicken stock cube

Salt or soy sauce to season

For the Risotto:

1 leek

2 cloves garlic Mushrooms, as desired Olive oil

35g butter, plus an extra tbsp for frying

200g short grain rice, washed (arborio rice is traditional, we used sushi rice)

1 glass white wine

75g parmesan cheese

Make the stock by dissolving miso paste and the veggie stock cube into the hot water. You’ll only need about 1 pint of stock for this recipe, but add an extra cup or so of water to allow for evaporation. Taste the stock as you season to make sure it’s salty and umami enough, as the rice will mostly be seasoned by the stock. Keep it warm while you prepare the other ingredients.

Cut a medium leek in half lengthwise, and then slice into half-moons. Dice up as many mushrooms as you want in the risotto. I like to roughly slice the mushrooms and then chop down onto my pile for medium sized cubes. Remember they will decrease in size while cooking.

Add the mushrooms to a fairly large pot on medium heat with about a tablespoon of olive oil, stirring until the mushrooms have released water. Cooking the mushrooms like this before salting will ensure they’re not soggy. Let the water evaporate, add a pinch of salt, then clear a space in the middle of the pan where you’ll add another tablespoon of olive oil. Add the leeks to the pan, and stir all the veg together, cooking until the leeks are translucent but have not coloured.

Stir in the rice and turn the heat up. Let the rice fry until ever so slightly translucent, and then add the white wine. Once the rice has absorbed the wine, add a big pinch of salt and ONE ladle of your stock that has been waiting for you on the stove, and turn down the heat to simmer.

This is the labour intensive part. Make sure you stir the rice constantly until all the stock has been absorbed. Repeat this process, allowing each ladleful to cook into the rice before adding more stock. Keep stirring lest the rice burn!

Once you’ve added about a pint of stock, taste the rice to see if it’s cooked all the way through. It should be al dente, but definitely not chewy and hard. If it’s not cooked and you’re out of stock, add hot water instead.

Take the rice off the heat, and right before you’re ready to eat, add the butter and grated parmesan. Put a lid on your pan and let it sit for at least two minutes. This is where all the delicious dairy and miso and wine flavours will come together, and it will create this delicious and creamy texture that is absolutely breathtaking.

It’s only natural to have your partner help out with cooking this romantic dish – but with the volatility of risotto, your romantic evening may start sounding like the ‘STEP OUT OF THE KITCHEN’ monologue from The Bear. Fear not, your partner can be useful in the creation of our recommended topping: Miso Braised Leeks, which can be prepared at the same time as the risotto. These decadent caramelised, almost confit leeks compliment the Japanese inspired risotto, and the acidity from the lemon and ginger rounds out the richness of the dish, and balances all of the harmonious flavours.

Ingredients

2 girthy leeks

1 Tbsp of miso paste, preferably yellow or white miso

2-3 cloves of garlic—measure with your heart—minced or grated

1 Tbsp of grated ginger

1 Tbsp of brown sugar

Juice of 1 lemon

125 ml/ ½ cup of hot water.

Salt and pepper to taste

Preparation

Cut the Leeks into 3-4 cm rounds, stopping at the place where the leaves become thick. Place an oiled pan on medium heat, and place the leeks face down. Sear for 4-7 minutes—or until there’s a char—then flip and sear for another 4-7 minutes.

While the leeks sear, throw the rest of the ingredients in a bowl to make the braising liquid, and whisk until the miso has dissolved.

Once the leeks have charred, pour the miso mixture into the pan and cover. Let it reduce for around 10 minutes, or until slightly thick/caramelised. Then baste the braising liquid onto the leeks, and continue cooking with the lid off for two more minutes.

For the plating:

In a bowl, lay a bed of the horny risotto down thick. Then place 3-4 leek slices on top—and dont be shy…add as much sauce as you want. This is a soft dish, so if you need that crunch factor you can top with some puffed rice and furikake.

Use Protection, and Enjoy.

by Maiti ú Catherwood

by Maiti ú Catherwood

WORDS

By Coco Goran and Mac Keller

WHAT IT CAN TEACH YOU

ABOUT YOU AND YOUR PARTNER

‘Don’t f*** on the first date.’

E‘You shouldn’t sleep with someone you just met!’

‘Wait for the third date!’

veryone has their own rules about when the ideal time to start sleeping with someone is after you start dating. But what about sex before dating? Sex can be a valuable tool in learning about your partner and can help to create a healthy relationship. So, in the era of onenight stands and situationships — which can be brutal or brilliant— what do you do when you find yourself going for dinner and a movie with the person you took home the other night?

Before delving into this topic, I think it’s important to mention that everyone has a different relationship with sex and it can mean different things to different people. Regardless, when having sex with anyone, it’s crucial to ensure that their expectations and preferences align with yours.

So, let’s set the scene: You’re out one night at a party, you meet that one person you just click with, and after spending the whole night talking or dancing together, you end up back at their place. You stay the night, and come morning time, you realise you aren’t ready for this to be goodbye forever, and neither are they. When you’re walking home debating how to progress this hookup to a relationship, what should you be taking into consideration?

One of the main benefits of sex before dating is that it helps you to lay everything out on the table — or wherever you prefer it.

As we’ve already hinted to, the most important thing is sexual compatibility — meaning how closely your turn-ons, preferences, fantasies, desired frequency, and definition of sex align. This element is crucial as you should never feel as if you have to compromise your values and desires, especially for the sake of a new relationship. A main component of finding out if you are sexually compatible with someone is to just try it out and see how it feels: How do you like to be touched? What are your turn-ons (and turn-offs)? What makes you feel good? What makes them feel good?

This is where we come to what sex reveals about your partner’s personality, values, and ultimately, their overall compatibility with you. While “giving it a go’’ and figuring it out may work for some people, there’s so much more that goes into having healthy and enjoyable sex — sex you will want to keep having as you develop and grow the relationship.

Sex is also a fantastic way to discover your own sexual identity, needs, and boundaries. Nothing like jumping directly into the deep end, right? When going home with someone, I’m sure the last thing on your mind is to do a quick check-in with yourself and assess if this feels comfortable and meets your needs — and I’m not saying this needs to be that explicit. With practice, however, you can learn to have a brief moment of introspection and learn what feels good, in every sense of the phrase. Being able to understand yourself to that degree, especially before committing to a relationship with someone helps assess not just your compatibility but how ready you are for that relationship yourself.

After acknowledging your own sexual boundaries and needs, another fundamental element of good sex is healthy communication. Being able to have healthy conversations is a sign of incredible maturity, confidence, and even bravery. This doesn’t mean that you need to sit down and have a meeting with an itemized agenda with your one-night-stand - believe me, it isn’t that serious. Good communication during sex just means that you can express what feels good, what doesn’t, what you’re comfortable with, and what is an absolute no-go for you.

Following this, it’s important to pay attention to how these conversations are received by your significant other. Does your partner make you feel validated when you communicate your values and preferences? Do they make you feel heard? And do you do the same for them? A partner that can maintain — especially if it’s not forced — an open line of communication with you, even in the heat of the moment, is one worth keeping. It shows they likely won’t have problems bringing up issues throughout the relationship in a way that is clear, direct, and honest.

I do want to note that sex before dating, much like anything else, does have its drawbacks. Expectations can be misaligned, and this can hurt one or both partners, especially when bigger emotions get involved. In the same way that sex can mean different things to different people, so can dating. While some people have a more casual approach to dating, others see it as more serious and look for something more long-term. This is why communication is key to make sure everyone is on the same page before you get in too deep - and yes, that is what she said.

This list is nowhere near exhaustive for all the ways sex can be educational. There are so many more ways it can help you learn more about your partner and yourself, and develop important skills for a healthy relationship. You can use it to understand someone’s attitudes towards their own body and pleasure; what their boundaries are; and if they’re selfish, giving, empathetic, shy, or outgoing as a person.

So, next time you have sex before dating, don’t be pressured to think of it as a mistake, instead see it as a lesson. You might be surprised by what you find out!

Stay safe and stay sexy!

WORDS by Nina Madeddu ART by Giulia VettoreSometimes I think there’s something horribly wrong with me.

I am a wind-up doll, unfurled. I am a walking contradiction: I love love sex – until I hate hate it. Some days I’m not burdened by it, but, as Valentine’s Day approaches, I find myself grappling with an evergrowing feeling of utter inadequacy and, quite frankly, impotence. I hope this article can reach those who feel like me.

Allow me to start by saying that I do not identify as asexual. Like other students, I think about sex and don’t find myself repulsed by the concept. On the contrary, I quite enjoy it in theory. However, I don’t like it in practice, and before you tell me I need to ‘experience good sex’, let me clarify that I have had good sex - great sex even - yet I always draw the opposite of pleasure from it, no matter how great it is.

I have nothing against people who have sex and who share their experiences with me. I actually enjoy listening to their stories; still, I feel like I live in a completely different universe from them. I don’t have stories to tell about sex, because I avoid it whenever I can.

By extension, I have no time-worthy relationship stories to tell either, because this hesitancy towards the act of having sex has put a serious strain on my love life. I think I could enjoy it if the conditions were right, and the condition is only one: I need to like the person, truly like them, not just aesthetically. I need to know them, be their friend, trust them. Unfortunately, it seems so hard to reach that stage in a relationship somehow, particularly as hook-ups become the norm and the expectation for most non-platonic encounters .

If that’s only natural, I am a machine.