6 minute read

Read, Learn and Earn!

By Drs. Saja Alramadhan, Neel Bhattacharyya, Nadim M. Islam

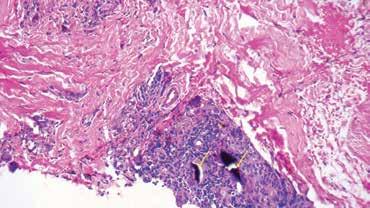

A 74-year-old Caucasian female was referred to Dr. Barton Blumberg, an Oral & Maxillofacial Surgeon in Lady Lake, Fla., for evaluation of a pigmented lesion. Clinical examination revealed a dark-black, non-ulcerated macule with diffuse borders on the left ventral tongue surface (Fig 1). The lesion measured 1.5 cm in the largest dimension, and the patient reported no symptoms. The patient's medical history was non-contributory. Dr. Blumberg performed an incisional biopsy that was submitted to the Oral Pathology Biopsy Service at the University of Florida College of Dentistry in Gainesville for a diagnosis. Microscopically, a noticeable pigmentation was noted along the orientation of elastic and collagen fibers and around blood vessels. Also, large particulate aggregates of black material were seen with associated giant cells. (Fig 2).

Question:

Based on the above history, clinical presentation and microscopic findings, what is the most likely diagnosis?

A. Melanotic macule

B. Malignant melanoma

C. Smoker's melanosis

D. Melanoacanthoma

E. Amalgam tattoo

A. Melanotic Macule

Incorrect, but great guess! Oral melanotic macules appear as a flat, brown mucosal discoloration. The lower lip vermillion is the most common location, followed by the buccal mucosa, gingiva and palate. Though the lesion is observed over a broad age group, it is most frequently diagnosed during the fifth decade with a 2:1 female predilection. Unlike the present case, the lesion typically appears as a focal, well-demarcated macule less than six mm in diameter. Once it develops, the macule remains consistent in size, a feature that helps distinguish it from melanoma. All oral pigmented lesions, especially if observed on the hard palate or gingiva, should be monitored for changes in size, shape and color, all of which would warrant a biopsy.

B. Malignant Melanoma

Incorrect, but good differential to consider! Malignant melanoma represents the third most common skin malignancy; however, it is rare in the oral cavity. The estimated incidence of oral malignant melanoma (OMM) is four cases per 10 million per year. OMM affects middle-aged patients with a female predilection. The average age of patients with OMM is somewhat younger than that of those with Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma (CMM) (~56 years vs. 65 years). OMM exhibits a more even racial distribution compared to CMM, which predominantly affects white patients. The hard palate and maxillary gingiva are most frequently involved. Clinically, OMM often presents as a brown to black macule or nodular lesion with ill-defined, irregular borders. Ulceration, bleeding and tooth mobility are not uncommon, these features are not seen in the present case. However, all unexplained oral pigmented lesions should be biopsied to rule out melanoma.

C. Smoker’s Melanosis

Incorrect. Oral mucosal pigmentation secondary to smoking tobacco is known as "smoker's melanosis." The condition is estimated to affect about 18% to 22% of smokers. The frequency and intensity of oral mucosal pigmentation strongly correlate with the number of cigarettes smoked daily. Several studies have reported a female predilection that may suggest an association between tobacco smoking and sex hormones; however, the exact etiopathogenesis is unclear. Clinically, smokers' melanosis appears as brown macules, but unlike the present case, it is usually multifocal or diffuse. In cigarette smokers, the anterior facial gingiva is commonly affected. In contrast, the buccal mucosa and commissure are affected more in pipe smokers, and in reverse-smokers, the palatal mucosa is the leading site of involvement. However, in the present case, the ventral tongue is not a usual location for smokers' melanosis, in addition to a negative smoking history.

D. Melanoacanthoma

Incorrect. Specific clinical characteristics make this diagnosis untenable, mainly the presence of this lesion in a Caucasian male and the lingual location of the lesion. Melanoacanthoma (melanoacanthosis) is a benign, focal melanosis characterized by a proliferation of both melanocytes and keratinocytes that result in pigmented macular or plaque-like lesions of the skin or oral mucosa. It is considered to be a reactive lesion precipitated by a traumatic event. Importantly, these lesions occur almost exclusively in African American females with a mean age at diagnosis of 35 years. The buccal mucosa is commonly involved. However, these lesions may rarely be seen in any oral sites. Melanoacanthoma usually presents as a single or occasionally multiple smooth, flat or slightly raised, dark brown to black macules. Notably, the lesion often demonstrates an alarmingly rapid increase in size. It may reach several centimeters in length within a few weeks, which may induce patients and clinicians to seek further attention to rule out melanoma. Melanoacanthoma is entirely asymptomatic and discovered during a routine examination. Cutaneous lesions are reported almost exclusively in Caucasian patients, and oral mucosal lesions almost exclusively in African American patients.

E. Amalgam Tattoo

Correct. It is the most common iatrogenic cause of oral pigmentation and results from dental amalgam implantation. Amalgam particles can be inadvertently introduced into the mucosa via abrasions or lacerations, following dental extractions, or by the force of a high-speed air turbine. Flossing the proximal contact of a newly placed restoration can even incorporate amalgam into the gingiva. Amalgam tattoo clinically appears as a blue, gray or black macule with well to poorly-defined borders. The gingiva, alveolar and buccal mucosae are commonly involved; however, other intraoral sites may be affected. Lateral spreading of the pigmentation occurs for several months after implantation, a feature that may arouse suspicion for melanoma. Large amalgam parti- cles may be detected radiographically as radiopaque fragments. However, the particles are often too small to be detected in this manner. Therefore, all oral-pigmented lesions that cannot be reasonably explained after clinical correlation must be biopsied to rule out melanoma.

Diagnostic Discussion is contributed by University of Florida College of Dentistry professors, Drs. Saja Alramadhan, Indraneel Bhattacharyya and Nadim Islam who provide insight and feedback on common, important, new and challenging oral diseases.

The dental professors operate a large, multi-state biopsy service. The column’s case studies originate from the more than 14,000 specimens the service receives every year from all over the United States.

Clinicians are invited to submit cases from their own practices. Cases may be used in the “Diagnostic Discussion,” with credit given to the submitter.

Drs. Alramadhan, Bhattacharyya and Islam and can be reached at oralpath@dental.ufl.edu.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None reported for Drs. Alramadhan, Bhattacharyya and Islam.

The Florida Dental Association is an ADA CERP Recognized Provider. ADA CERP is a service of the American Dental Association to assist dental professionals in identifying quality providers of continuing dental education. ADA CERP does not approve or endorse individual courses or instructors, nor does it imply acceptance of credit hours by boards of dentistry. Concerns or complaints about a CE provider may be directed to the provider or to ADA CERP at ada.org/goto/cerp.

References:

1. Neville, BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, and Chi AC. (2016) Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th edition, WB Sanders, Elsevier.

2. Meleti M, Vescovi P, Mooi WJ, van der Waal I. Pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa and perioral tissues: a flow-chart for the diagnosis and some recommendations for the management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105(5):606-616. doi:10.1016/j. tripleo.2007.07.047

3. Ashok S, Damera S, Ganesh S, Karri R. Oral malignant melanoma. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2020;24(Suppl 1):S82-S85. doi:10.4103/jomfp. JOMFP_5_19

4. Bhullar RP, Bhullar A, Vanaki SS, Puranik RS, Sudhakara M, Kamat MS. Primary melanoma of oral mucosa: A case report and review of literature. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2012;9(3):353-356.

5. Chae YS, Lee JY, Lee JW, Park JY, Kim SM, Lee JH. Survival of oral mucosal melanoma according to treatment, tumour resection margin, and metastases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58(9):1097-1102. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.05.028

6. Altieri L, Wong MK, Peng DH, Cockburn M. Mucosal melanomas in the racially diverse population of California. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017 Feb;76(2):250-257. DOI: 10.1016/j. jaad.2016.08.007.

7. Monteiro LS, Costa JA, da Câmara MI, et al. Aesthetic Depigmentation of Gingival Smoker's Melanosis Using Carbon Dioxide Lasers. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:510589. doi:10.1155/2015/510589

8. Hedin, C.A., Pindborg, J.J., Daftary, D.K. and Mehta, F.S. (1992), Melanin depigmentation of the palatal mucosa in reverse smokers: a preliminary study. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 21: 440-444. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb00971.xAbed SS, Fitzpatrick SG, Bhattacharyya I, Islam MN, Cohen DM. Oral Melanoacanthoma: Case Series of 33 Cases and Review of the Literature [published online ahead of print, 2022 Dec 7]. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;10.1007/s12105-022-01506-w. doi:10.1007/s12105-022-01506-w

9. K. Lundin, G. Schmidt, C. Bonde, "Amalgam Tattoo Mimicking Mucosal Melanoma: A Diagnostic Dilemma Revisited", Case Reports in Dentistry, vol. 2013, Article ID 787294, 3 pages, 2013. https://doi. org/10.1155/2013/787294

10. Burchner and L. S. Hansen, "Amalgam pigmentation (amalgam tattoo) of the oral mucosa. A clinicopathologic study of 268 cases," Oral Surgery Oral Medicine and Oral Pathology, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 139–147, 1980.