16 minute read

New

opening: trade between CEE and Africa: new financial solutions

CEE products have gained widespread recognition on a global scale, primarily due to their adherence to EU standards. Since 1989, manufacturers from the region have been competing with established Western European producers like Germans and French.

With the disruption of the global value chains stemming from COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, Central and Eastern European (CEE) trades are finding themselves in a new business reality. While trade with East Asia is a well-established import region, new primary export destinations are emerging for exporters in Central and Eastern Europe.

With the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the main export markets outside the EU for the CEE companies, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, were closed or significantly constrained. The events, which disrupted supply chains and in many places, redefined the existing trade relations, may paradoxically be conducive to Polish companies in winning export contracts in Africa. Fractured supply chains can open avenues to previously inaccessible markets, even if there are no historic ties between the countries.

Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK) is the only 100% stateowned bank in Poland, and is the fourth largest development bank in the EU. Due to BGK’s legal status, the Bank’s rating stays in line with the rating of the State Treasury (as of now “A-“ in foreign currency and “A” in domestic currency).

One of BGK’s main tasks is to organise and execute a variety of development programs established by the Polish Government, including the Governmental Program Financial Support for Exporters. Together, with Korporacja Ubezpieczeń Kredytów Eksportowych (KUKE) the Polish Export Credit Agency, we offer a variety of products for support of Polish exporters.

New opportunities in Africa

To capitalise on the opportunity presented by the new landscape, it is vital to undertake thorough preparation, particularly considering that CEE companies lack substantial experience in engaging directly with African countries. Up until now, our business dealings have predominantly relied on intermediaries.

Some African countries have strong, historic ties with Western European countries. For CEE exporters, it may be difficult to enter such a market and compete with companies that have been present over a significant period of time. There is a potential solution for CEE exporters. Sub-Saharan Africa may be attractive, although much more geographically distant, as the diversity of countries can make it easier to find a niche for these companies.

CEE products have gained widespread recognition on a global scale, primarily due to their adherence to EU standards. Since 1989, manufacturers from the region have been competing with established Western European producers like Germans and French.

Conversely, Polish exporters offer economically competitive products thanks to Poland’s national currency, which allows for reduced production costs compared to competitors in the Eurozone. However, due to the transition to a market economy occurring relatively recently, starting in 1989, the Polish brand may not enjoy the same level of recognition in geographically distant markets.

Challenges facing expansion with African market

In the given markets, the CEE exporters encounter numerous obstacles. Polish companies still lack experience in cooperation with African countries, for a number of reasons, including cultural and language barriers. Added to this is the low recognition of CEE countries in Africa. Bringing the CEE countries closer to local contractors as European nations that produce high-quality goods at competitive prices is likely one of the crucial tasks for institutions and entrepreneurs.

This process is hindered by the lack of familiarity of the local customs and markets. Additional risks such as non-payment, and political and economic volatility pose additional problems for contractors. One potential solution is expanding access to trade finance solutions like Letters of Credit, however, these are also obstructed due to local banking costs, or currency restrictions.

To support local businesses in foreign expansion, financial institutions are aiding with export finance solutions.

What are potential solutions to these problems?

BGK offers a solution to many of the existing problems via the purchase of receivables. This is a type of refinancing by BGK of a trade credit granted to a foreign buyer by a Polish exporter. BGK pays the Polish exporter the funds for the exported goods and/or services, while the repayment of subsequent tranches is made by the foreign importer directly to the Polish bank.

The importer gains easy access to attractive financing in the form of a long-term trade commitment, which is a simpler and more advantageous solution compared to a loan from a local bank.

This enables the African importers to improve their financial liquidity and improve access to goods and services from the Polish market, which is competitive regarding both price and quality. BGK does not require a guarantee from a local bank, establishing direct collateral on foreign assets and receiving support from the Polish ECA, KUKE. At the same time, BGK has the capacity to conduct negotiations and conduct transaction procedures based on documents.

Another measure to facilitate Polish exports to emerging markets involves the provision of buyer’s credit, particularly in sovereign structures. Under this scheme, the borrowing entity is the government of the target country.

Polish companies are actively pursuing infrastructure, medical, and IT/ICT contracts, which are typically commissioned directly by the Ministries or government agencies of those specific countries.

These challenges will not be solved immediately, as discussions with African countries are multifaceted. Ultimately, the goal is for Polish exporters and African companies to expand, regardless of location or industry.

3.11

Stuck between two humps: Mongolia’s balancing act in a shifting global order

Mongolia, with its rich agricultural heritage, has a unique opportunity to transition into sustainable, organic farming practices, tapping into a near $500 billion market. But for this, a significant shift in domestic farming practices and overcoming regulatory hurdles will be needed.

Mongolia, a nation steeped in history and folklore, finds itself at a crossroads.

As a landlocked country sandwiched between Russia and China, it faces unique challenges yet possesses a strategic geographic advantage.

The legend of the Mongol Empire still resonates with many–as I was reminded when visiting Ulaanbaatar’s dominating 40m equestrian statue of Genghis Khan–but today’s Mongolia is carving a different path on the global stage, trying to manoeuvre complex geopolitics and economic dynamics while preserving its sovereignty and identity.

As an observer at the World Export Development Forum (WEDF) 2023, where Trade Finance Global (TFG) was a media partner, I had the opportunity to discuss these challenges and prospects with local and international delegates.

Mongolia trade overview

According to John Miller, Trade Data Monitor, Mongolia’s primary exports include coal, copper ores, and crude petroleum, accounting for over 40% of its total exports.

China is the principal recipient of these exports, making up 92% of the total export value. On the other hand, Mongolia’s top import partners are Russia and China, accounting for 33% and 62% of total imports, respectively.

Mongolia’s economic trajectory as a landlocked developing country (LLDC) presents certain opportunities and challenges.

According to the United Nations, LLDCs like Mongolia face particular issues due to their lack of direct territorial access to the sea and isolation from world markets, which translates to high transit costs and decreased competitiveness.

The landlocked paradigm

However, the paradigm is shifting. Rabab Fatima, Under-SecretaryGeneral and High Representative for Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS), noted in her opening statement at the WEDF 2023: “Digitalisation reduces many of the entry barriers to international trade facing MSMEs and startups in LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS. It significantly reduces the transit-transport costs that serve as a major hurdle for LLDCs.”

Despite the formidable economic challenges, there’s an underlying resilience and adaptability that propels Mongolia forward.

This determination was highlighted by the country’s President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa in his speech.

One Billion Trees

While acknowledging the difficulties faced by LLDCs, he emphasised the ongoing efforts to counter these challenges, including the “One Billion Trees” campaign.

The initiative aims to combat desertification and mitigate the impact of climate change in Mongolia, a testament to the nation’s commitment to a greener future.

Khurelsukh said: “I firmly believe that these national movements will not only expedite the development of the environment, food, and agriculture sectors but also support regional trade and investment. Consequently, they will yield positive outcomes in the pursuit of sustainable development goals, including employment growth, poverty reduction, and the creation of a healthy and safe living environment for our citizens.” In addition to the environmental commitment, Mongolia’s economic endowment plays a crucial role in its strategy for growth. Nestled between economic powerhouses China and Russia, Mongolia lies at the intersection of significant global infrastructure projects such as Russia’s Trans-Eurasia railway and China’s Silk Road Economic Belt.

Mongolia’s role in OBOR and CMREC

Mongolia sits along the shortest path connecting Europe and Asia, making it a key area for China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative.

However, reliance on China and Russia carries risks of economic over-dependence, as does the potential for geopolitical conflict.

The rise of the China-MongoliaRussia Economic Corridor (CMREC) carries promises of economic progress but also potential pitfalls.

As of 2023, China receives 92% of Mongolia’s exports, highlighting the nation’s economic vulnerability.

In response to these geopolitical pressures, Mongolia has pursued a policy of diversifying its alliances.

Deputy Prime Minister of Mongolia, His Excellency Amarsaikhan Sainbuyan, has spoken about the nation’s aspiration for “enhanced economic independence”.

This strategy is embodied in the Third Neighbor Policy, seeking stronger relations with global democracies, including the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, India, and members of the EU.

Yet, the execution of these policies remains a complex task, which calls for effective domestic strategies and international cooperation. With international support, the opportunities for economic diversification are vast, with an emphasis on sustainable growth. Mongolia’s potential lies in various sectors, such as green and organic farming, digital services, and small and mediumsized enterprises (SMEs).

Farming and agriculturelandlocked to land-linked?

Rabab Fatima further highlighted the potential for organic farming in her speech, emphasising that “North America and Europe account for most of the sales of organic products, with 90% market share...However, LDCs, LLDCs, and SIDS are yet to tap the potentials of vibrant organic farming sector.”

Mongolia, with its rich agricultural heritage, has a unique opportunity to transition into sustainable, organic farming practices, tapping into a near $500 billion market. But for this, a significant shift in domestic farming practices and overcoming regulatory hurdles will be needed.

In the context of the global digital boom, Mongolia also needs to tap into the global digital services market, which reached $3.82 trillion in 2022. Again, the transition is a significant task that requires structural changes, investments in digital infrastructure, and human capital.

As Mongolia charts its path towards a sustainable, diversified economy, the phrase “landlocked” might give way to “land-linked.”

Navigating the complexities of this transformation demands wise domestic strategies, effective international collaborations, and a keen understanding of global trends.

Trade is about people, not goods and services

As President Ukhnaa said, “Trade is not about goods and services, it’s about people.” The key to Mongolia’s success lies not in its geography but in the strength, resilience, and vision of its people.

Mongolia sits in a unique and challenging position.

Its status as a landlocked developing country demands innovative approaches to trade, economic development, and regional cooperation. While the nation’s story is deeply intertwined with the fabled Mongol Empire, its future is inextricably linked to the complex geopolitical dynamics of Russia and China, and its ambitious Third Neighbor Policy.

Amid this context, the World Export Development Forum in Ulaanbaatar has showcased Mongolia’s quest for a sustainable, balanced, and inclusive economic future.

The reality of Mongolia’s situation is summed up aptly by policy analysts, stating that the country’s Third Neighbor Policy may suffice for now, but it is no guarantee of longevity.

Even as it leans into the challenges of being a landlocked nation, the reality is that Mongolia’s sovereignty and future are still tied to the “Bear” to its north and the “Dragon” to its south.

A nation of warriors and nomads, Mongolia stands at a crossroads of history and the future, at the intersection of great powers and greater ambitions.

Its path forward is uncharted and arduous, yet its journey will undoubtedly be watched by the world with keen interest.

Guarding the gate: Compliance amid fraud and money-laundering

4.1

Cloaked in trade: Unmasking the underworld of tradebased money laundering

Document-based TBML often depends on trade misinvoicing, commonly referred to as customs fraud. This method entails purposefully altering the value of a trade transaction by falsifying details such as price, quality, or country of origin.

In an increasingly interconnected global economy, the fight against financial crimes has become more complex and critical than ever.

One form of illicit activity that poses considerable challenges to regulators, law enforcement agencies, and financial institutions is trade-based money laundering (TBML). In its simplest form, TBML is a covert technique that allows criminals to conceal illicit proceeds by exploiting the very systems of legitimate trade, making it a potent tool in illicit financial operations.

In this episode of Trade Finance Talks, Brian Canup, assistant editor at TFG, was joined by Channing Mavrellis, Director of the Illicit Trade Program at Global Financial Integrity, to delve into the world of TBML. Together, they explored the latest developments and insights surrounding tradebased money laundering (TBML) practices.

Transnational crime and illicit financial flows: Connecting the dots

The UN Convention on Transnational Organised Crime deliberately refrains from providing a precise definition of transnational crime. This flexibility allows the convention to accommodate the emergence of new types of crimes on a global, regional, and local scale.

However, an official definition does exist for organised criminal groups, which involve three or more individuals collaborating to commit at least one crime to attain a direct or indirect tangible benefit. The range of typical operations conducted by transnational criminal organisations encompasses human trafficking, arms trafficking, drug trafficking, mineral trafficking, wildlife trafficking, counterfeiting and trading of counterfeit goods, fraud, extortion, money laundering, and cybercrime.

Furthermore, transnational crime does not necessarily require the involvement of a group but can be characterised by its transnational nature.

The connection to illicit financial flows is highly significant. Illicit funds refer to unlawfully earned, transferred, or utilised funds across different countries. Illegally earned funds can originate from activities like drug trafficking, while illegally transferred funds may result from customs fraud or trade-based money laundering (TBML).

Illegally utilised funds can be associated with terrorism financing. The main hurdle for criminal groups lies in the process of laundering criminal proceeds to make them appear legitimate, and this is where TBML becomes particularly relevant in the context of transnational crime.

Criminal groups perceive the utilisation of the international trade system as an immensely advantageous method for money laundering, capitalising on the opportunities that arise from global trade.

As Mavrellis said, “Having a method of laundering the funds that involve international trade can be very beneficial.”

Unveiling the methods of TBML

Mavrellis explained that (TBML) involves various methods, which can be categorised into document-based and nondocument-based techniques.

Document-based TBML often depends on trade misinvoicing, commonly referred to as customs fraud. This method entails purposefully altering the value of a trade transaction by falsifying details such as price, quality, or country of origin. By overvaluing or undervaluing goods during import or export processes, criminal organisations can facilitate the movement of funds into or out of a country while presenting falsified documentation to justify the additional funds being transferred.

On the other hand, nondocument-based TBML is quite challenging to detect. One prevalent example is the Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE), which originated in Colombia but is not exclusive to that country or narcotics trafficking. The BMPE mechanism relies on repatriating the proceeds of crime from one country to another without detection.

For instance, if criminal organisations generate cash from selling narcotics in the United States, they need to transfer the funds back to Colombia and convert them to Colombian pesos. In the BMPE, the cartel may purchase legitimate trade goods in the U.S. with the cash proceeds and export them to Colombia. The goods are then sold, thereby transforming the criminal proceeds into accessible funds in the commodity itself, bypassing formal financial systems.

Source: Global Financial Integrity, Financial Crime in Latin America and the Caribbean: Understanding Country Challenges and Designing Effective Technical Responses

Alternatively, the cartel may engage a peso broker who purchases the narcotics proceeds and facilitates their integration into the formal financial system through different means, such as individual deposits or cash-intensive businesses in exchange for a certain percentage.

Mavrellis said, “What we’ve seen before is a 10 to 15% commission for laundering $500,000. The broker says, I’m going to charge you a 10 to 15% commission for doing this. You’re accepting the risk of taking this cash.”

Recently, Chinese money laundering organisations have entered the TBML scene, seeking access to US dollars due to strict currency controls in China. These organisations offer to purchase unlawful proceeds at lower commissions compared to traditional peso brokers.

Mavrellis emphasised, “With the involvement of Chinese money laundering organisations, it gets a little bit more complicated.”

This creates a three-party transaction, where Chinese nationals acquire US dollars and simultaneously transfer an agreed-upon amount of Chinese currency (Renminbi) to the Chinese money laundering organisation’s bank account. The funds can then be used by the cartel to purchase goods in China for export to Colombia, completing the money laundering process.

On another note, traditional methods of money laundering face heightened scrutiny, leading criminals to resort to alternative tactics of TBML, to hide the illicit proceeds of their crimes. This shift raises the stakes, as TBML not only facilitates unlawful offences like narcotics trafficking, human trafficking, and terrorist financing but also serves as a means to disguise logistical support for terrorist activities, such as the transportation of weapons.

“I think this is in large part to the fact that so much of our AML CFT framework that’s out there globally is really focused on financial institutions and this backdoor of trade”, Mavrellis explained.

Ostensibly, TBML presents numerous challenges for law enforcement and policymakers as it capitalises on the loopholes in anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing frameworks, which primarily focus on financial institutions rather than trade.

Trade-based money laundering: Dominant industries & countries revealed

Criminals exploit various trade transactions to conceal and launder illicit funds. “Any commodity that you can think of, they’ve done,” Mavrellis revealed.

This versatility creates market threats for legitimate businesses, as illicit activities can disrupt fair competition. Hair extensions, used cars, and even cattle are just a few examples of seemingly unrelated trade items that have been exploited in TBML schemes.

Legitimate businesses often struggle to keep up with the pricing strategies and quick liquidation methods employed by those engaged in TBML.

“It can be very difficult for legitimate businesses to compete with some of these illicit activities.” Mavrellis highlighted.

When discussing the vulnerability of countries to TBML, Mavrellis expressed an inclusive viewpoint, adding “Which countries are most vulnerable? Again, it’s all of them.”

The effective screening of each global trade transaction is a daunting task for customs departments due to the sheer volume involved. Authorities are confronted with the delicate responsibility of striking a balance between facilitating trade and combating illicit activities, ensuring both business continuity and national security are safeguarded.

China has emerged as a particular area of concern due to its extensive involvement in transnational crime and illicit financial flows. The massive volume of goods entering and leaving the country provides ample opportunities for the camouflage of illicit activities. Mavrellis said, “When you think about just the volume of goods coming in and out of the country, it’s very easy to disguise any kind of illicit activity.”

Black Market Peso Exchange

To demonstrate the intricacy and extent of trade-based money laundering (TBML) operations, Mavrellis shared a compelling case study from the 2021 Financial Crime in Latin America and the Caribbean report. The study centred on a Black Money Peso Exchange (BMPE), showcasing the sophistication of such illegitimate schemes.

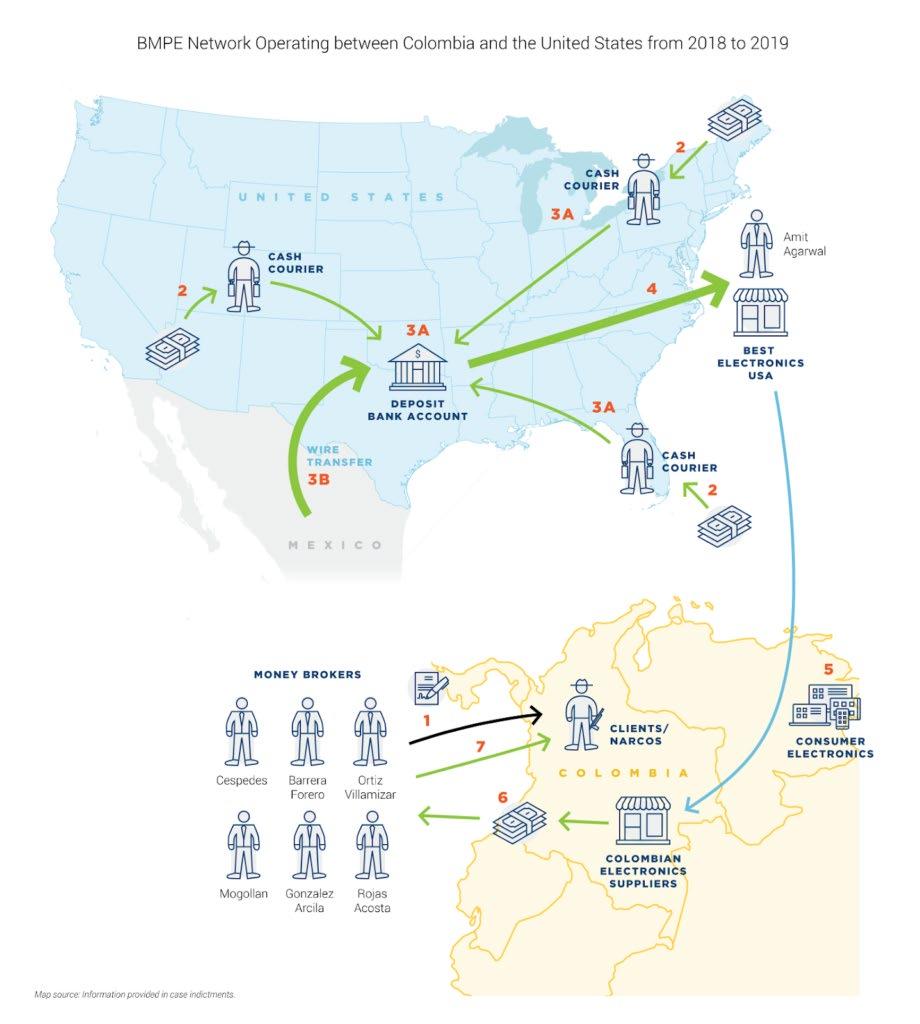

According to Mavrellis, in 2019, a Black Money Peso Exchange (BMPE) network operating between Colombia and the United States was dismantled by the US authorities.

Money brokers, also known as peso brokers, acted as intermediaries between individuals, businesses, and criminal organisations, facilitating the exchange of currencies.

The US Department of Justice alleged that six money brokers based in Colombia were involved in laundering and repatriating narcotics proceeds, specifically cash from the US back to Colombia.

Narco-traffickers would contact these brokers to inform them about the cash in the United States requiring laundering. The brokers would then create contracts detailing the pickup of US currency, delivery of roughly equivalent value in Colombian pesos, and the commission to be received. Once the contract was signed, the brokers arranged for the pickup of cash using a network of couriers located across the country.

The couriers would then deposit the collected funds into the DEA-controlled bank account, which also received wire transfers of illicit proceeds from other countries, including Mexico. Amit Agarwal, an Indian national and owner of Best Electronics USA, played a pivotal role in this network. After receiving the funds in his business account, Agarwal would export electronic goods of similar value to Colombian electronic suppliers, using a code name on the commercial invoice to link the transactions to the corresponding money broker.

Rather than paying Agarwal directly as the exporter, the Colombian electronic suppliers would pay the appropriate amount in Colombian pesos to the peso brokers, who would then deliver the funds to their clients, the narco-traffickers in Colombia.

The money brokers retained a commission for themselves and the couriers.

The case study underscores the importance of conducting thorough customer due diligence and profiling to uncover instances of trade-based money laundering. Unusual behaviour, such as businesses depositing large amounts of cash outside their standard patterns, can raise red flags for financial institutions.

Strengthening the global defence mechanism: How governments can fight against financial crime

2. Continuous and dynamic information exchange between countries. The current practice of exchanging data on a periodic basis limits the realtime identification of tradebased money laundering (TBML) and other fraud threats. The ideal scenario would involve countries sharing trade data to allow customs authorities to track and verify transactions accurately, enhancing overall transparency and security. As Mavrellis pointed out, “It’s all about data. It’s all about sharing data. Everybody needs to know what’s going on. That’s our point of view.”

3. The establishment of robust legislation and registries for beneficial ownership. Beneficial ownership refers to the identification of the ultimate owners of businesses or companies engaged in international trade.

Amid the ever-changing landscape of criminal activities, governments play an imperative role in combating these illicit practices. As policymakers seek strategic measures to address these evolving issues, Mavrellis has put forth several key messages.

1. Trade and customs records to be freely accessible to the public. While some aggregated information is available through sources like the United Nations Comtrade database and S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Panjiva, more detailed and comprehensive data is necessary to adequately verify trade transactions.

4. Implement targeted economic and financial sanctions. Directing attention towards individuals, entities, and countries involved in financial crimes and money laundering can. By denying access to the financial system, it becomes possible to disrupt the operations of these networks and diminish their influence. As Mavrellis stated, “We should focus on targeting individuals, entities, and countries that facilitate financial crimes and money laundering, and consider the application of economic and other targeted financial sanctions against those engaged in such illicit activities.”