osculum

Exhalent Current

In ow of Seawater

In ow of Seawater

Thank you to everyone who kindly wrote in. TnadT would not be what it is without paddlers taking the time and effort, to share their experiences and knowledge with us. Please keep them coming; helpful guidelines for contributors are at the back of the magazine and on www.iska.ie.

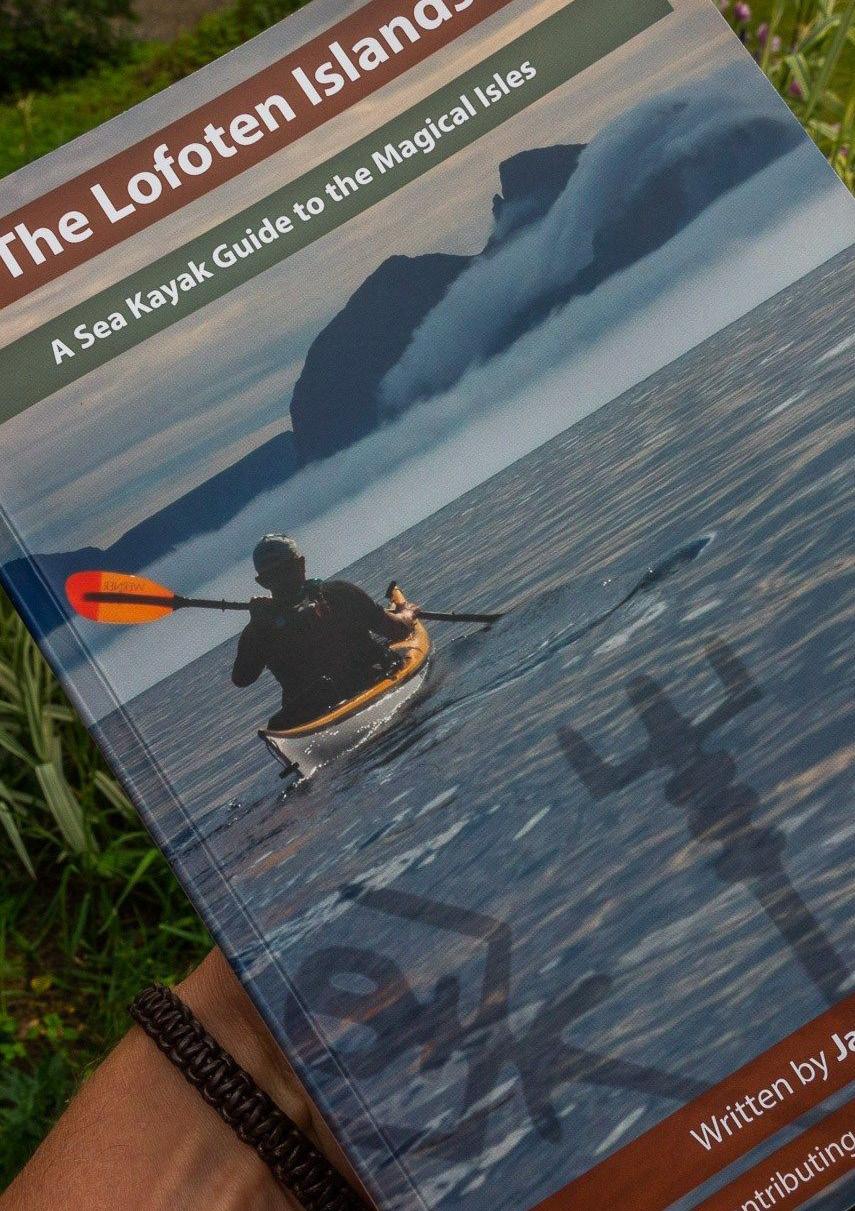

This issue we have lots of good things for you. I used ‘A Sea Kayak Guide to the Lofoten Islands’ by Jann Engstad just this August before and during my trip. If you are travelling there, it is well worth the read.

Following on from the Shrike, Nick Crowhurst provides us with his guidelines for making our own Vember sea kayak in the Kit & Kayak section. TnadT is always on the hunt for articles on any pieces of kit or skills/technique advice that you might like to share with us, so please do send them in.

I am always happy to paddle rocky shores at low tide, especially in caves; the colour and variety of sponges is beautiful and TnadT welcomes Eleanor Honan who provides a description of these amazing ‘animals’ in our environment section this issue.

Dave Conroy recounts a relaxed trip to the Scottish Sea Kayak symposium in Skye in May. Wiska Paddler Marty Corbett provides a stream of consciousness account of his trip to the Lofoten Islands. We welcome Liz Gabbett first time contributor to TnadT who describes a delightful trip to Kerry.

While summer 2018 was mostly warm sunny and calm, incidents still happen. Ray McCullagh and Kevin O’callaghan’s research on sea kayak incidents reminds us all not to be complacent.

Paddle safe and enjoy the sea. Sue Honan

Welcome to the ISKA Symposium 2018 and we hope you enjoy exploring the superb County Cork coastline.

2018 has been a good year, only one meet having to be canceled due to weather.

The very un Irish summer of 2018 has seen many members make progress on their bucket list. I can’t remember the Skelligs seeing so many kayaking visitors in the one calendar year. The Lofoten Islands inside the Norwegian Arctic circle has also proved to be a popular destination this year.

I wish to thank all the meet organisers for their efforts this year, with a special mention to Dave Conroy and his helpers from the ECSKC for a rarity, a meet on the east coast, which was very well attended and the feedback was excellent, probably the best attended meet for many years outside of the Symposium. You doing it again in 2019 Dave?

As per usual our inaugural meet was Streamstown which gets the year off to a good start and thanks to the long standing efforts of Dave Glasgow & Peter Hennessen, the Committee agreed to bestow them honorary life membership. The Streamstown meet also raises funds for the RNLI every year.

We also ran training weekends in the spring and many thanks to Fiona Trahe & Steven Darby for organising them. On the subject of training, the generous subsidies available to members wishing to gain L3, 3*, L4, 4* and Rec 3 or 4 certs will continue in 2019. We encourage members to take advantage of this.

On the Committee front, there will be one change as our Secretary/Treasurer wishes to take a year out and Conor Smith has agreed to fill that position during 2019. I’m sure you’ll join me in wishing John Dempsey a fantastic year of travelling.

I hope you all enjoy the Symposium and I wish to extend a warm welcome to our new members and the contingent of my fellow Scots who will be attending this year.

As always a huge thank you to Sue Honan for her excellent work as editor of TnaD, and to Adam May at Language who makes us all look so good in print. Many Thanks to all of the Committee and those who have helped out during the year.

Now, where will Symposium 2019 take place? We are actively working on this.

Reviewed by Sue Honan

Knowing nothing about the Lofoten Islands before I went there in August, I bought this book online directly from Olly Saunders’ Rock& Sea Productions website. It provides information on 47 sea kayak routes throughout the Lofoten Islands I liked the typeface, colour scheme, maps and photos. It looks and feels an accessible book. He covers getting there, camping, weather sources, shopping and things to do.

Jumping straight in to any page, you realize that you need to read the ‘How to use this guidebook section’. This is because the book is coded into A, D and Y trips and these are further graded 1-5. A paddles are day trips, D paddles are journey trips on the sheltered inner coast of the Lofoten Islands and Y paddles are journey trips along the exposed western or outside of the islands. The number grading system divides the routes according to length, ease of landing, wind speed and water states with 1-2 being an accessible easy day trip 15km or less and 5 being committing, exposed 25km or more trips with difficult landings and technical water. He also gives the map number required for each route. Some translations of map symbols is provided which is useful. The availability of coffee shops and bakeries is also noted, very handy for hungry paddlers. Each route is laid out with start, finish,

landing, HW/LW reference port, tidal info, weather source, and challenges. Then a description of the trip is provided including camp spots. Tidal flows are given where available.

The book certainly excites and entices one to visit. The pictures are beautiful and a nice touch is the inclusion of short accounts of special days or areas by coaches, instructors and local paddlers. Explanations of local spots, traditions, people and wildlife add to the general interest of the book. It has something for all abilities of paddler. Having paddled parts of some of the routes, the guide is accurate and reliable.

A few little gripes are that a couple of the maps are too small to read easily. There are typos too. One larger omission is the trip planner that on page 16 Jann says is at the back of the book – it isn’t there.

The book is available from Rock and Sea Productions and other outlets if you search online.

ISBN: 978-1-78280-910-4

The Lofoten Islands A sea Kayak Guide to the Magical Isles

Published by Jann Engstad 2016 Lofoten Aktive AS PB136 / 8309 Kabelvåg www.lofoten-aktiv.no

Liz Gabbett

Limerick paddler Liz Gabbett describes one of many beautiful summer weekend sea kayak trips in Ireland this year.

The weekend of the 7th & 8th of July 2018 saw a group of Clare, Limerick, Kerry and Cork paddlers meet on Doulus Head outside Cahersiveen. The aim was to camp beside White Strand beach, kayak around Doulus on Saturday, exploring every inch of the coastline and on Sunday head for the Skelligs, a jewel in the crown for all seakayakers.

Start Point: White Strand, 51.937851, -10.275084

Stop of points: Church Island, 51.937851, -10.283347; Beginish Island, 51.937814, -10.2922.02

Lunch Break: CuasCrom Beach, 51.964913, -10.213594

End Point: Coomnahinch Pier, 51.989447, -10.213594

Low Tide: 06:36; High tide: 12.42

Weather and sea: ideal, calm, sunny and very little swell.

Start time: 11am-ish

Finish time: 6pm-ish

Distance: we didn’t GPS track it but we probably covered 25-30km

Crew: Emma Glanville, José Carlos Alonso, Sinead Frawley, Fiona Trahe, Stephen Darby, Gildas & Clara Laplaud, Mary Kavanagh, Liz Gabbett.

White Strand is a popular beach for local people in Cahersiveen. It is well serviced with lifeguards and a very clean, modern, well maintained toilet and service block (including plug points to charge phones!). On Friday night we camped on the patch of grass behind the service block and the attendant kindly left a toilet open for us. Six of us had gathered on Friday night and three more arrived early Saturday morning. As it was a long one-way paddle we left our cars in White Strand and Emma parked her van at Coomnahinch Pier to shuttle us back at the end of the day. Sinead contacted the Coast Guard to inform them of our plans and when we expected to be off the water.

Immediately offshore from White Strand is Church Island and Beginish, i.e. a quick 5min hop from the beach. Both islands have remains of ancient settlements and it was worth landing on both to go exploring. Church Island is a tiny rocky outcrop and is easy to land on. OPW have placed an information board as the church remains are significant. Beside Church Island is Beginish. We landed on the beach facing Valentia Island and Mary led us to the remains of the Viking settlement and that had been discovered in recent years and when a storm blew back the sand to reveal buildings left by the Vikings. We all noted that Beginish would be a great island to camp on for future trips in that area. The island looks to be inhabited and farmed with at least two well-maintained houses. The Beginish stop-off was less than 30 mins.

Once we were off Beginish we began our exploration of every cave, blow hole, stack and rock to be hopped. It was a gorgeous day with a little bit of bump on the water outside the caves but there were no issues getting in and out. The cliffs were alive with seabirds, predominantly guillemots

The group dynamic and awareness was excellent throughout the day. We had one minor incident when Fiona lost a hatch cover which she thought was tied on. We now know why Fiona takes ages to get on the water as she is ever-ready for any potential incident. She had all the necessary materials for Emma to cover the hatch with an old nylon spray desk and many metres of rope to secure the makeshift cover.

We had our lunch in the small sandy beach at CuasCrom. There were a few families there enjoying the day and there was a portaloo and bin for any necessary rubbish disposal. After our lunch and a small nap (I do appreciate a good nap) we got back on the water and continued our exploration of the Kerry coast.

Kerry is gorgeous. It is a different beauty compared to Clare, it is far more lush with green fields slopping down the mountain/ hillside into the sea. As you look across the water you see the Dingle peninsula stretch all the way to the Blasket Islands.

When we arrived at Coomnahinch Pier we were tired but satisfied. Sinead rang the coast guard to inform them that we were off the water.

While the pier and slip is sizeable there is very little parking. Once we got our cars we needed to load up quickly and get out of the way of local people and holiday makers getting in and out.

That evening we headed into Cahersiveen for well-earned pizza in the former church at the end of the town. There we reviewed our plan for the next day. The original intention was to camp on Saturday night near St. Finian’s Bay Pier (known locally as The Glen) and get up early on Sunday to be on the water for 7am, but Mary Kavanagh very kindly offered her house as our base. This meant we didn’t have to worry about breaking down tents in morning; we could conserve or sleep and still aim to get on the water at 7am. Some of us slept inside while more camped in tents or vans outside.

Start time: 7:20am

Finish time: 6:30pm(ish)

Start & End Point: St. Finian’s Bay Pier, 51.847517, -10.355858

Destination: Skellig Micheal

Comfort break on the way back: Puffin Island, 51.842269, -10.403547

Weather Conditions: Excellent. Slight swell 1-2m.

Crew: Emma, Mary, Sinead, Clara, Gildas, Brian, José, Liz

Distance: we didn’t GPS track it, but the journey is typically 35km

The Sunday start was early, a 05:45 alarm call for everyone and by 07:20 eight paddlers were on the water heading west. The sky was overcast but the Skelligs were visible in the distance. Our aim was to get to Skellig Michael before the first tourist boat at 9:30am so we pushed on. Sergeant Major McMahon cracked the whip calling our ETA at regular intervals and we were allowed a short 4min break just after Lemon Rock. If ever there was an illusion of distance this morning certainly proved it. Lemon is half way to Skellig but it doesn’t appear like that when you are on the water. Having said all that, it is a fantastic journey out there with the sea birds keeping us company all the way. Puffins, Guillemots, Gannets, Fulmars and Shearwaters were swooping, diving and gliding all along the way. We made it to Skellig Michael at 9:30 on the button but so too did the tourist boats, and they have priority at the pier. We waited patiently and to be honest there was not much waiting. Emma was first out and with some minimal assistance she hauled her boat up the steps. After that we all landed, the first few up the steps and after that we used a shelf in the rock beside the pier. Landing wasn’t too difficult, the trick

was to do what Emma said and hop out on the top of the swell.

Once we got all boats up on to the flat rock (plastic is king for hauling boats over rocks studded in barnacles) beside the pier we gathered our breath, changed clothes and took in the majesty of our surroundings. We also provided amazement to the tourists who were also landing. They kindly paid for the entertainment by taking photographs of us hardy kayakers.

For anyone thinking of doing this trip if you want to climb the steps up to the monastery, be on the island early between 9am and 1pm at the very latest. Otherwise, the OPW guides will not let you past the pier. They have to do their job and they must give a health and safety talk to everyone who lands on the island. Also, there are no toilets or bins on the island and beware off any bird poop that will hit you, so plan accordingly.

We spent around 2.5 hours on the island taking paparazzi shots of the puffins and a visiting Luke Skywalker. It is well worth listening to the guides give their talk and explain the history of the island.

We got off the island around midday and circumnavigated to check out the lighthouse

and caves. You have to wonder about the monks who decided to set up out there with the weather, remoteness and inhospitable nature of the place. They were amazing but definitely nuts!

We took our time coming back to explore Skellig Beag and just hang out. Between Skellig Beag and Lemon Rock a Minke whale popped up to say hello and check us out. For 30 minutes Miss Minke circled us and passed underneath multiple times. She corralled us and held us captive until she had enough of us. This was an exhilarating and an incredible addition to the day.

The water was calmer coming home and the sun was high in the sky. A few of us called into Puffin Island on the way back as we needed a land break before the final 3km to St. Finian’s pier. We were tired but happy paddlers.

This was an amazing trip with really good, considerate people. Again, like Saturday, the group dynamic and awareness was brilliant. The whole weekend was definitely a major highlight in my kayaking experience.

East coast paddler Dave Conroy was at the Scottish Sea Kayak Symposium in May.

Iknew of three others, Andy Wilson, Ollie Dyas & Jane Egan, that were also making the trip to the Scottish Sea Kayak Symposium (SSKS) in May. It would have been a year since my shoulder surgery/ bicep tendinosis and having seriously curtailed my paddling activity before and after, a return to one of the first and most beautiful places I started sea paddling in was called for. A chance for some me-time, peace’n’quiet, a bit of headspace and to test out my bionic shoulder, somewhere that nobody knew me!

Had considered flying to Inverness, car & kayak rentals - a bit messy, but in the end I drove, giving me the comfort of my own vehicle, own kayaks (brought my creeker too) and also brought my bicycle – very important to have gear that fits, especially when you’re 6’11”, getting older & creakier all the time.

Away up the road to Fort William for a few ‘messages’ - sun cream, midge repellant, bread, ‘shteak’, veg, fruit and booze, the diet of champions. The amount of campervans, kayaks & mountain bikes in Morrissons car park was staggering, I spent quite some time

drooling, before doing any shopping!

Scenery en route was stunning, I saw a lovely little river that I quite fancied running and was very tempted, but I could hear my mother’s voice rattling around in me head, “don’t do anything stupid” she was saying. Glorious mountains, forests, lochs, rivers, seemed paradise! With so much to do, and so little time it was onwards to Skye, stopping for a quick trip around Eilean Donan.

The Gaelic College, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, on the Sleat Peninsula was venue for the SSKS. If I had gone to school here, I would’ve spent all my time staring out the windows, the views were breathtaking. I opted for full board, hostel accommodation and given it was the start of our amazingly hot summer, I was very glad of it too. A comfy bed, power shower and privacy to let it all hang out, after a long days activities.

There was access to the water, directly behind the college, down a cliff face and on to a rocky shoreline. Getting 50 odd boats down a steep path, through the branches and round corners was some operation, but sure

t’was great craic too. I followed proper health and safety regulations, by not offering to help carry boats - guidelines say you should always lift heavy objects with someone of equal height and there were no other 7ft tall paddlers present...

At breakfast, I was delighted to bump into the Magnificent Mike McClure. We had a great chat; he had worked in the area previously and was filling me in on the ‘must dos’. I had no idea what sessions I would take, only that I didn’t want to overdo it...

Easing myself into symposium mode, I started with Navigation Class, expertly presented by Nicky Mansell, who’d come all the way from Jersey. The theory, was soon followed by practice, navigating our way to an ice cream kiosk, which we could see from the put in point. We then paddled about disturbing the other serious classes, who were doing various exercises, techniques and skills etcetera before lazily paddling back to the college. It was a perfect first day!

Sunday morning and I still hadn’t decided what I wanted to do for the day. There were

loads of classes on. I thought I should use this opportunity to get in on a Gordon Brown session, but he was doing balancing and tricks – lots of getting wet, which I just didn’t fancy. After all the coaches gave their briefs, Donald MacPherson of Explore Highland offered a solution for the few who hadn’t made up their minds, a short trip, 5kms across to the Knoydart peninsula ‘and beyond’ – I obviously didn’t hear that bit, as it was another 11km further along to Inverie. I was feeling a little sore but a few Haribo placebos seemed to do the trick. Anyway, civilization at last although the coffee shop, museum, gift shop were closed on Sundays, leaving the pub, which turned out to be a bit unwelcoming. Therefore, we dined al fresco, with our packed lunches, by the Knoydart totem pole and relaxed awhile before making the return journey, 32 km in total. It was beautiful, Caribbean blue waters and amazing scenery and great craic with our small group of 4.

Later that evening, Mike McClure gave a presentation on his epic cycle from County

Down to La Seu d’Urgell. It was extremely entertaining and gave a hilarious view into what might not have been so funny at the time, the trials, and tribulations he endured en route to the Pyrenees; well done Mike, a very enjoyable show. We brought our laughter over to the pub to finish the evening off there. Monday morning was the last day of the main event, but my tendonitis was playing up, so I went for a cycle instead, 30kms around the Sleat peninsula, with 580m of climbs, quite a mean feat for a leisurely cyclist. It was an amazing day. Took a while for me to get beyond the hill overlooking Tarskavaig with the Cuillin mountain range beyond, not because it was steep, but it was stunningly gorgeous; I bought a print of the same scene before I left Skye later that week, thanks to Grumpy George. Onwards to Tokavaig, where I was chased out of the village by a bull, then on to Ord, a swim to cool down, before lunch. Returning by a distillery for some cake and alcohol, as one does. That evening saw a presentation for Gordon Brown, who has retired (from Skye) and has moved on to pastures new in Canada.

I had signed up for two days extra activities and at last I was ready to rock’n’roll. I decided on a trip from Kyleakin, below the controversial Skye bridge, along the coast to Plockton for a bag o’chips. Guided by Roddy (SeaKayak Bute) & Sea Kayak Alice, many lovely rock formations and some cold water coral, which Gordon B later told me was the remains of calcified marl. I also had a wonderful encounter with a few seals and dozens of diving dolphins, too quick for the camera unfortunately and slightly ruined by the captain of a glass bottom tour boat, roaring up the sound for his passengers to see, t’was good while it lasted.

I wanted to be able to tell you all about how wonderful an event this was and to encourage y’all to come to next year’s one, but this one was billed as the ‘last Skye symposium’. I never asked why, I was half afraid they might say if you want another, to organise it yourself and I might just have taken them up on it!

You probably expected more photos of sea kayaks in stunning locations and there were plenty, but to be honest, that’s something you really have to do for yourself, so how about it?

SSKS: 150 delegates for the main event, with 44 staying on for extended activities. 22 coaches; 11 helpers and 4 staff. An impressive total of 187.

Coaches came from England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Jersey and America. Delegates came from Scotland, England, Wales, Jersey, Ireland, France, Holland, USA & Belgium.

At the same time next year, is the Jersey Sea Kayak Symposium 2019, run by Kevin & Nicky Mansell.

Friday 24th May for the full week. Booking will start towards the end of September and there will be around 90 places. Pre register for details kevin@seapaddler.co.uk

Held in a local hotel, the weekend includes workshops, followed by paddles around the island, with possibilities of paddling to other channel islands if the weather is kind. Most people come for the week. There are some kayaks available to hire for those who want to fly. Thanks Nicky for the info

Marty Corbett travelled to the magical Lofoten Isles in August with Emma Glanville, Chris Ted, and Conor Smith.

Crazy mental & busy-as-hell spring & summer. No time to look forward to planned Lofoten -LOFOTEN! kayak trip.

Lofoten kayak trip, three words I never thought I’d use personally.

First mooted by Emma several years ago

Not possible, various constraints.

Got a fabulous trip to Scottish little isles with Emma & Fiona meanwhile

Good practice for me as I hadn’t done many multi-day trips.

Performance anxiety, will I be cranky - a long time in close quarters- it’s an interesting dynamic. Will I be the slowest to her ready? I really missed you in Lofoten, Fiona.

All gear & clothes on floor the night before a 6:00am start.

Never was I so glad to finally get on a plane & head into the unknown. Away from everything

Oslo airport, Scandinavian design, rushing through, weirdest calzone pizza ever. Flying into Bodo. Looking down on jagged mountains, steep grey striated upper slopes, ice & water. Everyone going through Bodo airport has boots, rucksacks. You’re north now.

Cool 38 seater propeller plane from Bodo to Svolvær, into the really weird names, proper remote expedition feel.

Excitement building now. Step from the plane to see dark vertical mountain island, right there! Oh, wow!

Ruar’s hostel, grumpy old chancer, everyone else tiptoeing around him. Young German guy showing Ruar his whittling progress - “I learned my whittling from a master”? -Too funny.

Reine, drizzle, hard to face into the first paddle trip after such inactivity. Great to be on water, eventually! Actually paddling in a fjord.

In Reine, in Norway. Lofoten even. Barely suppressed excitement! Feels so good to stretch those paddling muscles. Needed to get onto the water. Getting lazy after travelling & lying on bunks reading.

When I was a kid we made rafts in an abandoned quarry. In all my paddling, only this place brought me back, & back continuously to that; steep rocky sides, shore consisting of jagged boulders fallen down from above.

First camp, first cooking,pouring rain. Gusting. Hike? Why not? Tough wet terrain. First sleep, should be miserable in this weather but seething with joy.

Rain? Sometimes you’d swear there was someone outside with a power hose. Wind shaking tent. First real test. Will I end up outside in the dark in blizzard conditions? Cool to storm test all the gear bought over the years.

Conor & Emma swam in a Corrie one morning. Really? Ye swam this morning? Not me.

Wet, everything so wet. Having to undress in a tiny tent porch because of torrential rain. Poncho. Complete with strings under arse. Dry suit. I can barely take off my dry suit at the best of times. Bone snapping, back straining, eye popping agony. Try it sometime. I fucking dare you.

Baby grow dry thank fuck, cold as hell.

Heading north, burger place on side of road. I don’t give a shit how much it costs. Emma shopping for tat.

White tailed eagles. Mink. Stoat behind a stove in an abandoned shack. Picking & eating bilberries throughout. The scenery.

Seriously. Every ten minute someone saying – would you look at that! The aromas of the vegetation, the sea. The pure air.

Paddling along good big bouncy coast conditions, each lost in his/her own space, no need to look at each other. Rock hopping a big choppy paddle to Nusfjord. Gorgeous village, weird Norwegian cheese & lovely bread & tea. Lads had famous cinnamon pastry. I hate cinnamon.

Weather terrible, climbed a tough 7 hour mountain. Arduous climb, I involuntarily whooped when I reached the coll. Wind gusting like crazy as I climbed the ridge above. Dived for the ground once. Someone had taken a dump behind a rock on the actual trail! Can you believe this shit?

Came across a tepee paddling one day, complete with furs. Misty morning paddle, lack of visibility adding to the surrealism. Dipper dipping, sound of the stream pouring, gushing tumbling & rain pelting onto the water’s surface. Recorded 30 seconds worth. Must dig it out. Pink noise, supposed to be relaxing or something.

Huts, sometimes, in campsites. Glorified garden sheds with bunks. Showers! Copious amounts of hot water! Privacy & alone time for up to 5 whole minutes! Always with the searching for places to dry and/or wash gear.

Cooking fresh (huge) mackerel in tinfoil over wood fire in a cool communal cabin. Delicious beyond belief.

F6/7 promised. Ideally we should head today, early as possible as it’s promised worse. Hmmm...We’ll get dressed & have a look. Pick a line & paddle straight out as we need

to make it out far enough to be upwind & upswell from the entrance. Huge swell, tight group for once, everyone keeping an eye on each other. Change course? Not yet, if we gauge it wrong we’ll be in an unknown rocky area with limited options. Swell lifting us good & high, wind howling, jaw hurting from smiling. Oh yes. Adjust to east, hurtling past the entrance islets, keeping an eye out for boats as this is the most touristy fjord.

No boats out that day. Only us. A couple of hours blasting along in front of the shrieking wind, cold torrential rain on the back of the drysuit. Is that water making its way in or is it wind-chill? Hmm.

Singing louder than the wind. The lads will forever twitch when they hear New World in the Morning. Roger Whitaker fyi. Strange, the songs that appears on one’s mental karaoke.

Walking along deserted roads. Talking shit, the most underrated activity known

Dry spot under trees while rain spills outside, a tiny refuge of calm.

Aurora fucking borealis, really, the fabled aurora borealis. Lying on our backs on the rocks, freezing, giggling, ripping the piss & looking at the Northern lights. The actual northern lights. To think people aren’t out doing this shit! What’s wrong with them?

Goodbye to Conor in the middle of the night. He swam. In a Corrie lake. In a fjord. In the Arctic circle! And then there were three.

Northwards, ever northwards, in search of whales. Café on road, tea & coffees & waffles. – Only €14! – worth €14 for that dump alone dude –

Rain stopped & sun came out & we went for a paddle around this low island. Still, incredibly clear water, colours, vibrant shades of nature. Absolute silence & bright sunlight. Then the sound of porpoises exhaling somewhere. Nature’s unsolicited heavy breathing.

Andøya. Really remote. Who the hell lives here? Soldiers in the supermarket.

Someone with a jeep & trailer gathering seagull shit from the window ledge nests. Cold miserable night. Feeling lost. Phoning. Sound of loved ones voices. Feeling better. Hike to top of cliff edge. Sit & look & chill & chat with other tourists. Bounce down the hill after. Through a copse of beautiful silver birch, my new favourite tree. All is cool again. Heading back south. Roadside tea. Stretching out on a picnic bench in the warmth of the sunshine, dozing. Always with the tea. I’ll put up with anything as long as we have abundant stores of Irish tea and a way of making it. Milk too of course.

West towards Skogsøya island. Looks like we could get a good 6 hour paddle around that island. A six hour would be nice. Needed. Camped where the wood meets the water. Campfire. First campfire! Has it been that wet? Obviously has.

West, then northwards along the western shore, bounced along by sea & wind. Loosen the bones. Sunshine feels good. No matter how remote, the Norwegians have electricity poles strung along. Everywhere.

Turn into the open bay & there’s the wind that was pushing us along. Except now it’s funnelling down a valley & punching us straight in the pusses. A real struggle to paddle south into the bay.

Pee break for Ted & me. Next thing we’re sat on the rocks chatting & sharing GORP, totally forgetting about poor Emma in her boat & more importantly her poor bladder. She gently reminded us.

Women paddler’s bladders, a wonder of the natural world. Discuss.

– D’you want some GORP Emma? –

Lunch on Sept 1st at a tiny pier. Where else would you be?

Around & into a stiff stiff breeze on southward leg. Tough slog. Love these conditions. Bottom corner & now it’s fun. We’re five hours out, glad of the lunch for energy & what might be an hour’s paddle into a relentless 5. Meh! what about it. Wind patterned waves on the water, the visual equivalent of pink noise. Wind hitting you on the face, feeling it, whipping around your head, ears, neck, eyes, lifting up your head & drawing deep lungfuls of it in through dilated nostrils. Insatiable hunger for the touch of the wind, invisible but what a physical presence. The light, the sky, the wind. Trudging along. Trudging, such negative connotations but so, so pleasurable.

And then, it drops off. Gentle paddle to shore. Hang gear on strung line. Perfectly exhausted.

Saw moose, plural, that trip (mooses? Mice? Meese?).

Ended up staying in a really cool place one night. Old pier barn bought to be protected & preserved by Luna.

Great hike to top of local mountain.

Burger joint treat. Ex junkie from Oslo. Middle of nowhere. Swedish family sharing our accomodation. Cards, guitar, conversation.

Back into Lofoten. Water cascading vertically left & right, – there must have been savage rain here! –

Coming towards the end, hard to believe. Planning the last few days. Me hoping to fit too much in. Cranky.

Back to campsite & tents up. Ted leaving, last

minute decision, grabbing what we’d need, stuffing anything unnecessary into the van.

And then there were two.

Paddle south along the coast, not expecting much really. Town in the distance, why not?

Turns out to be incredibly picturesque, glorious sunshine, main street is on water, mountain backdrop, store fronts on stilts.

Fabulous relaxed lunch, hanging & chatting.

Around the island, under the curved bridge & northwards for home. White tailed eagle rising powerfully just in front of us, effortlessly, pointedly ignoring two nuisance kayakers staring silently slack jawed. All we need now are a couple of orcas.

Racing to catch the light of the setting sun on a tiny rocky island with the dark mountains in the background. Paddling on in silence. Savouring our last paddle.

Mirror water in bay, sitting in boats recording the scene in our minds. Thinking to myself, will it fade? Will it become just a distant memory?

Walking into town, two hours. Grand stretch of the legs prior to long journey home. Pressie shopping. Last lunch on a bench in Svolvær. Warm watery sunshine. Stroll back alongside the road. Another two hours. Why would anyone drive/get a taxi when they could walk? Especially on a last day in Lofoten.

Treasna na dTonnta welcomes Eleanor Honan. Eleanor completed her PADI Divemaster this summer and had plenty of opportunity to observe sponges that are visible to sea kayakers as we explore caves, snorkel or roll our kayaks for a look around.

Any paddle through the rocky intertidal zone at low tide will reveal that the seemingly grey stone of the Irish coastline is anything but barren. Encrusted onto the rock surface are non-distinct organisms of rich ochre, greens, yellows, oranges, spanning across the outcrops like bubbly, low relief mats; or sticking out in flesh-like protrusions, in some cases up to 15 cm high. Assigning these creatures to a specific group it would be easy to lump them in with the algae, to whom they bear more than a passing resemblance, but to do so would be to miss out on one of the most fascinating, bio diverse and overlooked elements of the Irish (and global) marine fauna.

These are the sea sponges, those belonging to the family Porifera, one of the oldest and potentially first multi-cellular animals to exist on Earth.

Sponges are an ancient group, predating not just us, but modern animals and plants in general. The origins of the sea sponge date back to at least 580 million years ago in the late Precambrian, appearing in the fossil record well before any of the fauna that we recognize as ubiquitous today. Tentative chemical fossil evidence puts the sponges into existence at around 750 million years ago, making them not one of, but the first animals to exist on earth.

Sponges are not true metazoans (animals) in that they lack any cellular organization into tissues. They have no nervous, circulatory or digestive systems, making them incredibly simple for an ‘animal’. They represent an evolutionary blind alley of sorts, branching off first from the group whose descendants would become most modern animals and us. Thus the sponges are considered a ‘sister group’ to all modern animals.

However, despite their huge evolutionary disparity from modern organisms, sponges have shown remarkable staying powerconsistently represented in the fossil record from their origin in the Precambrian to today’s modern faunal assemblages. The resilience of the species can be explained by their varied reproductive methods, their adaption to many environments, and the diverse morphology seen throughout the group.

Sponges live in all ocean basins, inhabiting the seas around poles, the tropics, and temperate ocean waters like those found along Ireland’s coastline. Only a small minority of living sponges tolerate fresh water conditions, with most preferring clear, quiet salt-water environments. They are found from the intertidal zone down to depths of more than 8 km.

Sponges are today grouped into three main families; the calcareous sponges (Calcarea) with calcium carbonate spicules, most at home in shallow water and pale in colour, glass sponges with siliceous spicules found in deeper waters (Hexactinellida) and the most common demosponges (Demospongiae), which bear siliceous spicules and are reinforced with Spongin, a collagenous protein. These Demospongiae represent the majority of sponges found in Irish waters. Also, the natural sponges you may find in your bathroom or kitchen are from this family, although these usually come from the Bahamas or Mediterranean sea.

The family name of the sponges is Porifera meaning ‘pore bearing’. Their soft bodies are composed of a layer of non-living, spongy material sandwiched between two layers of living cells. The sponge’s soft body is supported by tiny calcareous or siliceous spicules. The more or less cup shaped soft body of a sponge is lined with hundreds of tiny pores known as Ostia into which sea water flows, aided by the beating of tiny whip like flagellum cells which lead water through the sponge’s internal system of canals, in which nutrients are siphoned out of the water. Waste water is then expelled out through the osculum (Fig 1) Their feeding method is simple; due to the lack of a circulatory or digestive system, sponges rely on a constant flow of water through their bodies to provide nutrients and oxygen, and to eliminate waste materials , but also effective. Experiments have shown that harmless fluorescent dye injected into the water column at the base of large barrel sponges is exhaled from the osculum of the sponge seconds later.

The sponge’s size varies greatly, from purse sponges on the mm scale to behemoths, like the minivan sized specimen of Rosselidae discovered 2 km deep off Hawaii in 2016.

Sponges reproduce using both sexual and asexual methods. Asexual reproduction happens most commonly by fragmentation, in which pieces break off the sponge and develop into new individuals, or by budding, wherein a section grows and detaches from parent.

Sponges are hermaphroditic, meaning one individual can produce both gametes (eggs and sperm). Sexual production occurs in different ways for different species. Some produce gametes year round while others are temperature dependent.

Ejection of spermatozoa may be a timed and coordinated event. Sperm are sent out the exhalent current openings, sometimes in masses so dense that the sponges appear to be smoking. These sperm are subsequently captured by female sponges of the same species. Inside the female, the sperm are transported to eggs by special cells called archaeocytes. Fertilization occurs and the zygotes develop into ciliated larvae. Some sponges release their larvae, where others retain them for some time. Once the larvae are in the water column they settle and develop into juvenile sponges.

Ireland hosts an incredibly diverse range of sponges; the island has 290 confirmed species, and recent estimates put the true figure at around 500. Rich biodiversity occurs around Rathlin Island, with 128 species recorded there by a team from the Ulster museum in 2006.

Sponges look for environments where they can guarantee a constant flow of nutrient bearing water, a stable substrate to grow on and little deposition of sediment to avoid blocking their ostia or pores. Favoured locations are under rock overhangs or tucked in under the supports of piers or jetties, meaning that kayakers and SUPers are usually in prime position when it comes to taking in the Irish Porifera without scuba equipment.

Common sponges seen by kayakers include the Purse sponge Granita compressa, (Fig.2) a pale beige sock like creature that can grow up to 2 cm long. It is found all along the Irish coasts from the lower shore and

sub tidal regions. If you look closely at a specimen, you’ll notice an obvious osculum at one end (the ‘toe’ of the sock’) and a holdfast anchoring the base of the sponge to rock or seaweed. Purse sponges are commonly found clumped together in groups of several individuals.

aphotomarine.com

The bright yellow colour of the Boring sponge Cliona celata makes it a stand out specimen along the rocky coast. Despite its colour, it is commonly known as the Red Boring sponge, and evidence of its existence is found in discarded shells of mollusc like oyster and clams covered in tiny, mm scale holes littering the intertidal zone (Fig 3). The sponge secretes an acid onto the substrate, either rock or shell, and creates a network of tiny tunnels which it lines with its own cells.

The Green Breadcrumb sponge Halichondria panicea (Fig. 5) can be found from the intertidal zone to depths of nearly half a kilometre, slightly out of range of the standard roll of a kayak. Its shape is determined entirely by its habitat: in sheltered coves or pools the sponge forms large globular encrustrations up to 20 cm thick, but most frequently along our coast it’s seen in its thin sheet like form of mats several meters in area, clinging onto rocky substrates in wave battered habitats. The sponge itself isn’t actually green- it gets its colour from the presence of symbiotic algae in shallower waters. It may also be a pinkpurple colour. It has a characteristic smell once exposed. Past the photic zone and into deeper waters the sponge is creamy grey.

Fig. 5. Breadcrumb Sponge Source: Habitats.Org and http://epongescharentemaritime.e-monsite.com

The charmingly named Flesh sponge Oscarella lobularisis found growing on rocks and even large algae along the lower shore, in lobed fleshy projections around 1 cm long and wide. Upon closer inspection these projections have a clear exhalent osculum on their upper surface. These are not to be confused with the soft coral commonly known as Dead Men’s Fingers (Alcyonium digitatum)

Fig. 6. Flesh Sponge Credit: http:// epongescharentemaritime.e-monsite.com/

A distinct species to lookout for especially along the Atlantic coast is the golf ball sponge (Fig 7). These spherical yellow to orange sponges are covered in spiky projection and are, aptly, approximately golfball sized. They’re often found growing amongst kelp or beneath rocky ledges and can grow up to 10 cm in diameter. Don’t touch the sponge without gloves as the spicules may still be present and can pierce the skin and remain embedded causing great discomfort.

7. Golf Ball Spong credit: http://darwinianleft. blogspot.com

To conclude, one sponge species can have many different morphologies, and both sheet like and projection stages of growth. If you do come across a sponge that you can’t identify, try snapping a photo and record it’s location and send it in to The National Biodiversity Centre http://www.biodiversityireland.ie/ contact-us/

Michael O’Farrell circumnavigated Ireland in 2017. Here he discusses some aspects of the trip and things that may be of interest to other sea kayakers.

On the first day of May 2017, I set off from Bulloch Harbour to paddle around Ireland for the sake of it and to raise funds for two charities - Pieta House (suicide awareness) and the RNLI.

When I left Bulloch Harbour I headed north to take the counter-clockwise route I was accompanied as far as Howth by an escort party from the East Coast Sea Kayaking Club (ECSKC). They were making sure I left Dublin Bay! From there on I was (mostly) paddling solo…

What drove this circumnavigation was a combination of hearing of others do it, a wish to see the coastline of Ireland ‘from the outside’ and that it was on my ‘bucket list’:

I was not the first to take on this challenge. More than 80 people have paddled around Ireland since first circumnavigated in 1978 (mostly clockwise and in teams); and

There are many islands and places I have yet to see around Irelands coast, so this was a chance to draw an imaginary line around them.

Having a cause is a big motivational factor. Fund-raising for this circumnavigation started in March, when I appealed for donations at the end of a canoe race in Kilcullen - that kicked off the fundraising with €200. My employer, AIB, was very supportive of my adventure with unpaid leave and hosted a cake sale. With family help we hosted a Tea Party at home in Newbridge where we roped in friends, neighbours, and any kayakers living nearby to have a cuppa and hear the plans. I had impromptu donations from random strangers I met along the way.

The planning started in 2016 and the key requirements were in place before the end of the year - I had agreed time off from work and, more importantly, got the OK from the Boss to spend time away from home!

I hooked up with a Physiotherapist (DublinPhysio) to check out the body (the engine) and I followed the flexibility / conditioning training he recommended.

I started training by doing some long canal runs with some marathon river races and, in January 2017, I paddled the 26km Great Island Kayak Race (GIKR) to confirm that the engine was running ok.

A month before starting off I did some sea training in Dublin Bay (a week of back to back 20 km evening paddles) to check that the engine could keep going.

Previous week-long sea trips with friends meant that I had a good expedition routine, knew the essential items to bring and had the confidence to tackle the journey.

I also got support Colm in iCanoe and Des Keaney with some invaluable items of kit. The sea is tough environment and quality equipment was important.

Horn Head

The food planning started off with much detail – but my diet ended up being very simple and ad hoc as the circumnavigation progressed. It centred around porridge, pitta bread lunch and rice/pasta for dinner.

• Porridge/dried fruit/honey and fry ingredients for cooked breakfast. This meal was the best organised throughout, despite suffering a night time robbery at Blackwater campsite –by a fox!

• My two daily lunches consisted of pitta bread, ham & cheese with tea. My evening dinner consisted of pasta or rice with whatever meat was available.

• Fruit cake (i.e. Christmas cake) was a personal favourite for lunches, dinners and snacks. I was re-supplied with freshly baked cakes during the adventure (from home and Eileen &Marie Kelly).

• Protein Bars, pitta bread and Oranges were used to top up energy level on long open-sea crossings. There is something satisfying about munching into an orange with the juice dripping onto the deck. For variety I would dip pieces of orange into the sea to add to my salt intake.

• I carried plain water in my platypus but found that adding a slice of lemon made a big difference.

I brought the usual safety gear (flares, smoke, VHF radio) as well as a PLB (Personal Locator Beacon). This is a small device that would alert rescue services giving my location if activated. The radio and PLB were attached to my lifejacket.

I started off with long john wetsuit and cag, but this was too hot for many days on the East coast though adequate for the West coast during mid Sumer. For a few days on the East coast I had to take off my cag in response to a heat rash.

Before departure the kayak received a spiritual blessing - I was covering all options!

I contacted the coast guard before and after each day’s trip and made text or phone contract with home every night. I found that the South East of Inishtrahull has a good phone signal!

The nicest part of my trip was the North coast and especially a visit to Inishtrahull Island off Malin Head with its complex tides. It was a first time for me to paddle out to this uninhabited island where I overnighted. Thanks to Adrian Harkin’s navigational advice, Inishtrahull was a big item knocked off my bucket list.

The weather was beautiful at the NE corner (Fair Head) and on the paddle to Rathlin island. The sea was calm despite this having fast tides (those tides pushed the kayak’s speed to over 19kph).

Slieve League, Co Donegal, was beautiful as the cliffs were lit by with the setting sun when I paddled by.

Twice I encountered dolphins, pair of common Dolphins in Antrim and a less common Risso’s Dolphin in North Mayo. I came across loads of seals but no basking sharks or whales were sighted. When I discussed that with the IWDG they put it down to and the fact that kayakers haven’t got a high enough viewing platform to spot others. I thought also that there were lower than average sea temperatures during May & June

I did see a sun-fish and interrupted a seal off the Wicklow coast as he was dining on an octopus (the meal was so big that the seal had to surface to eat it).

On the more interesting side, my rounding of Loop Hear, Sybill Point and the conditions after I rounded the Mizen were memorable for different reasons. Suffice to say that I took no photos.

Not really.

Before setting off I worried that boredom would be a problem.

My racing background meant that I was used to going a long distance from A to B on my own, usually after being left behind by others. As I was going to a new destination on each paddling day I had a sense of anticipation each time. Plus there was an bit to be done navigating, checking winds, charts and tides to make sure I was not paddling into trouble.

I found the warm flat calm days harder (less motivating) whereas in choppy weather I was occupied with work of paddling and staying upright!

On two occasions I had a problem feeling sleepy (like falling asleep at the wheel of a car but with the risk of rolling over) so I got off the water at the nearest beach for a 40

minute nap. I wondered what would have happened if anyone spotted this lone paddler curled up beside his craft on a deserted beach!

Fellow East Coast sea paddlers came along to keep me company for two bits of the journey. Chris Hamilton paddled with me for a while in Donegal and an ECSKC party met me around Ballycotton.

During the trip I bumped into other circumnavigators going the other way. I met Caoimhe Connors on two occasions, initially at Clogher Head on the first day of her trip and again on the Dingle peninsula - both were during stormy conditions. I also met Julian Haines in Co Clare, by appointment at accommodation provided by Ruth Bracken! A bit of forward communications was necessary as we missed each other while passing in the same bay!

Every person I met along the way on land and at sea was very supportive.

Mentally I felt great during the trip and was pleasantly surprised at the distances I managed to cover. I had planned on covering up to 40Km per day and after the first week I was clocking more than 50Km on successive days.

Physically I picked up minor ailments (niggles) and, while these niggles were always a source of worry, they never developed into problems. Often the niggles would go away to be replaced by others the following day. That helped with boredom as it gave me something to be thinking about.

I was off the water for 12 days because of bad weather and most of that downtime was encountered around Kerry. Those days were frustrating – I was wishing to be on the move.

There were a few ‘white knuckle days’ as is to be expected on such a trip. The worst was experienced after an 8 hour paddle past Sheep’s Head when I rounded the Mizen. There I ran into an ebbing flow and choppy water with low energy levels as the light was fading. There was nothing I could do but concentrate, keep ploughing ahead into the gloom and make enough progress to get out of it.

My daily travels were tracked on Endomondo, a phone app which pushed a report to Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ seascrapes .

Colleagues and club mates from ECSKC and KCC tracked my circumnavigation and regularly sent texts and comments on Facebook/twitter.

My wife comprised the backup team and met me at weekends. I also got (and used) many offers of accommodation along the way. In fact I only spent one third of my time ‘under canvas’, the rest being in B&B or put up by friends along the way.

The total elapsed time was 71 days made up of:

• 43 days moving on the water

• 12 days stormbound and 16 days on a family holiday in Portugal (I had hoped to finish before that but only got as far as Carnsore Point before I took time out to comply with this ‘hard’ deadline).

Of the 55 days at sea or stormbound:

• 18 nights were spent in tents;

• 25 days in B&Bs or Hotels/Hostel some organised remotely (thanks Senan). I had a high proportion of my steak dinners in these places!

• 12 days put up by friends/colleagues along the way, some of whom ferried me back and forth as well (thanks Adrian, Chris and Jon).

Every person I met en-route was encouraging and many made on the spot donations to my two charities Pieta House and the RNLI.

Since last Summer I have ‘wintered well’, lost all my residual long distance fitness and put back on the 5 kilos that went ‘missing at sea’.

I went back on the water alternating between ECSKC and the river at Kilcullen Canoe Club.

Looking back at my activity levels since the circumnavigation, I note that I spent less time on the water than usual and that I have been absent from many club meets. I guess the circumnavigation effort did have an impact after all.

I collected a total of €9,000 in donations, and reiterate my thanks to supporters, donors and everyone I met along the way.

Many Irish paddlers have built Nick Crowhurst’s Shrike. Following on from that success, Nick has designed the Vember. Read on and enjoy the build of The Vember, 2017 design from CNC kayaks.

We all have an idea of our perfect sea kayak. We would wish to specify the performance characteristics, the length, the beam, the shape and size of the cockpit, the deck height, the maximum acceptable weight and several other details. If you value the performance characteristics of “British-style” sea kayaks, then our latest offering of free plans from www.cnckayaks. com gives you the opportunity to create your bespoke kayak. Introducing the Vember family of sea kayaks with round bilge hulls to give smooth and progressive stability from upright to edged; kayaks that will be capable and reassuring in rough seas and strong winds. The Vember family has proven to satisfy those requirements. A crucial aspect of the design implementation is that the length and beam of the kayaks can be varied independently to suit your style of paddling, your skill level, and your choice of day paddling or expedition use. Details of how to achieve this are contained in the 59 page Build Manual which comes with the free plans download.

The hull is shaped to give smooth, progressive and reassuring stability throughout the heeling range, based on rounding out the chined cross-sections of our West Greenland inspired Shrike design. Vember is not a kayak for speed records or a specialist surfing, and neither is she “all things to all paddlers”. She is a general purpose sea kayak that is now my “go-to” craft for day paddling. For camping, the lengthened Vember Expedition has greater carrying capacity.

An important aspect of this project is the combination of a wood-strip hull with the simple plywood deck used in our Shrike range of sea kayaks. This avoids the complexity of a set of forms to shape the combined hull and deck, and enables builders to vary the length and beam of the hull, the size and shape of the cockpit, the height of the foredeck and gunwales, the positions of the bulkheads, and the layout of hatches, all without altering the structure of the deck. The result is a simplified construction, adaptable to your requirements, which minimises the experience and skill required of the first-time builder.

Vember only requires a flat workbench on which to assemble the hull forms. The spacing of the hull forms can be varied to suit your purpose, but our Build Manual describes the construction of Vember at 300mm spacing and the Vember Expedition, at 330mm spacing, while retaining the standard beam. (The beam can be varied by changing the scale of the printed paper plans of the forms. Details in the Build Manual)

Dimensions of Vember are:

Length: 4.86 m (15.94 feet)

Beam: 0.546 m (21.5 inches)

Weight, with hatches, seat, deck lines, and wire operated skeg: 15.9 kg (35 pounds) And for the Vember Expedition:

Length: 5.346 m (17.53 feet)

Beam: 0.546 m (21.5 inches)

Weight, with hatches, seat, deck lines, and wire operated skeg: 17.2 kg (38 pounds)

A local experienced paddler is planning to build a fast Expedition version by maintaining the length of 5.346 m (17.53 feet), but reducing the beam by 10% to 0.491 m (19.3 inches).

Planking the hull is a rewarding and exciting process. I was initially concerned that this stage would be difficult, but I found that it required care and patience rather than skill, and the hull gradually appears like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis. The Build Manual documents this stage in sufficient detail for the first-time stripbuilder.

Once the hull is completed and turned over, one can choose the type and size of cockpit and hatches, and the height of the foredeck. Full details of these options are given in the Build Manual. Vember materials cost £550 (U.K pounds). We used cove-andbead profile strips for this hull, but for the Vember Expedition hull we just used square edged strips. This proved straightforward, as with such thin strips minimal planing is required to fit the strips closely together.

Here’s a performance review of the Expedition version from Damian, who has a shed full of kayaks:

“

If I had to pick just one boat, this would be it. Even empty and in a cross-wind, she behaves herself and I’ve yet to really need the skeg. She’s light enough to throw on the roof-rack for an afternoon’s playing, but has the capacity to take a fairly hefty load for trips. The shallow rounded keel allows you to layback fully and this means I’ve been able to hand roll her - a trick I can normally only do in my specialist rolling boat.

She attracts a lot of attention. Every time I’ve taken her out, without fail, I’ve been approached by people who have been seduced by the curves and want to know what she is. Having spent a couple of months shuffling round in wood shavings, it’s great when people appreciate the boat.

She seems to be very quick. In the absence of any proper trials, my anecdotal evidence is that whenever I put on the power, I’m able to leave buddies’ chined Greenland boats behind, far more so than in my other boats.

Everyone who has test paddled Vember has enthused about the looks, the weight, and the handling, so we decided to release the design on-line and free of charge, in the same way that our Shrike range was released in 2014. You are free to modify the plans and to make money by producing and selling kits and completed kayaks.

The free download of full-size plans contains a variety of format options, ranging from paper printing on your home A4/letter size printer, through commercial continuous roll printing, to the CAD files to drive a CNC cutter to produce the temporary forms directly from plywood. Any of these options will produce all the forms to produce your

complete kayak. Also included are the files to drive a 3D printer to produce our concealed deck fittings, and our 59 page Build Manual. In the first week after the project was launched over three hundred copies of the plans were downloaded.

You can download the free plans from www.cnckayaks.com and then perhaps you might experience the special joy that comes from paddling a kayak that you have created with your hands – and from your dreams.

Ray McCullagh & Kevin O’Callaghan

In early 2018 an online survey of sea kayak incidents was undertaken between the February 8th and March 8th. The study was part of an undergraduate dissertation for a BA (Hons) in Outdoor Education at GMIT’s Mayo Campus. The survey questionnaire was modified from other surveys previously undertaken by Bailey (2010), Aadland et al (2017) and Brown (2014). The survey questionnaire used a combination of closed multiple choice and open ended questions. The primary aim of the survey was to identify the contributing factors involved in sea kayaking incidents.

An overview of the results and findings is presented here with a more detailed paper to be published later in the year.

Gordan Brown, in a survey on how top-level sea kayak coaches deal with incidents, when asked, “What constitutes an incident?” He replied,” Anything where an intervention had taken place that had enabled the group to continue the session, stopped a group member getting injured or a piece of equipment from getting damaged.’’ This suggests that an incident may impact upon the group / equipment / individuals, but where interventions have taken place to avoid or mitigate and event these should still be regarded as incidents.

The National Incident Database (NID) of New Zealand is managed by the Mountain Safety Council (MSC) and is a voluntary database which collects incident reports in outdoor adventure sports. It defines an incident as “ an undesired event that could or does result in a harm or loss. The harm or loss may involve harm to people, damage to property and/or loss to process”. (National Incident Database, 2017). Near misses and psychological issues associated with incidents are also recorded.

Priest and Gass (2005,) use the word “accident” but define it as “unexpected occurrences that result in an injury or loss’’ The potential losses can be physical, social, emotional or financial.

So, it would appear that ‘sea incidents’ may be broadly defined as ‘unexpected events that need to be managed’. Management of the event may include actions:

• to prevent / deal with an injury (physical or emotional)

• to manage equipment loss or damage

• to manage / adjust trip plan to address group issues

Failure to deal with any of the above would result in increasing risk exposure to participants. The resultant situations are familiar to most sea kayakers and could involve capsizes, cuts, blisters, lost paddles, overestimating a group’s ability, and mismatching your expectations with that of the group. Failure to address any of these minor incidents appropriately can lead to an accident or an incident of greater severity. Sean Morley sums this up brilliantly when recalling an incident, “..It began with a basic error of judgement, so obvious and significant that in hindsight it seems ridiculous.’’

Previous studies examined for this survey indicated that the main factors contributing to incidents were, human, environmental or equipment related factors. Of these, the human factor was identified as the most significant and was primarily because of poor decision making and/ or poor situational awareness.

While this study had a short survey window, the data received was in-depth with some replies being in excess of 1000 words (for 1 question out of 25). That was more data than could be handled in the window allowed for processing the survey and indicated this is an area meriting more examination in the future. In addition, it has provided data for more specific studies.

• We filtered the data down to 44 respondents.

• 70% of those who took the survey had been paddling for 5 or more years, with nearly half of this group having 10+ years of experience.

• Most of the incidents happened in the West coast.

• 71% of incidents occurred in areas that were familiar to those involved.

• 58% of incidents reported in the survey were rated at 3 or higher on a 1-5 scale of increasing seriousness, adapted from the New Zealand incident database model.

• Group size was a factor. Most incidents happen in groups of 7-8, followed by group size of 3-4.

• Only 4 incidents occurred with people paddling solo

• 30% of those who replied had no formal training,

• The bulk of incidents (80%) happen in winds of Force 4 or less, while a third of all recorded incidents occurring in Force 3 winds

• Cliff coastlines record the largest number of incidents

• Tides and dumping surf jointly account for the next most significant environmental factor as a contributor to incidents.

• Half of the respondents described an event as a ‘near miss,’ in that an incident was averted, though the events described included: Hypothermia, a missing paddler, an incident requiring coastguard assistance, etc.

• The next most significant description of injury recorded was one of psychological impact

• When asked to review the contributing factors to the incidents, 42% of respondents selected ‘poor ‘judgement’

• Equipment

• All respondents appeared to be very well equipped

• Only 4 incidents cited equipment failure as a factor, these were related to deck or hatch issues.

• In one incident, the absence of a PFD was the contributing factor.

The results compiled relating to incidents appear to be broadly in line with other published data in that human factors were largely the most significant factor. There were some issues of concern within the data:

• Many of the ‘near misses’ that were not classified as incidents by respondents, included requiring assistance from the coastguard, hypothermia, one of the group missing for over an hour, etc. These are incidents. Hypothermia can be fatal. The issue of Situational Awareness (SA) which was highlighted in the literature, would appear to be important here. There was significant divergence as to what constituted a near miss in this sample of paddlers.

• While it is a legal obligation in Ireland for all water craft users to wear a PFD the absence of PFDs is mentioned in 4 of the studied cases and in one case it was the primary contributing factor in the incident.

• In 62% of the incidents reported, the authors could identify a human factor as a primary contributing factor. Human factors included poor judgement and decision-making, lack of initial planning, inadequate skill level and situation awareness.

• Half of the incidents were a capsize due to inadequate skills, or poor decision making which resulted in paddlers being in an area of environmental conditions beyond the experience of the group or paddler.

• When reading over the accounts of incidents it appears that with proper planning and good judgement and decision making, the group could have avoided situation in the first place.

• There are several situations where there was an unsuitable weather forecast, but the group went anyway. It was also noted that a group should have or could have turned back sooner but hadn’t. This suggests that while risk assessments were undertaken there was no continuous or dynamic risk assessment in operation.

• One incident was described from different perspectives. One of the participants indicated that rescues, incident management was done very effectively, and that there was nothing else that could have been done. Another experienced participant was highly critical of the same incident as there was significant equipment damage and potential risk to others.

• Belfast Kayak Club submitted some detailed reviews of incidents that indicted an excellent practice of formally reviewing incidents with a view to changing practice and procedures to avert similar incidents in the future.

• Other research indicates that most incidents occur in more windy conditions than in this Irish study i.e. > Beaufort Force 4

• Most incidents involve solo paddlers in other studies, while in this study most incidents involved groups of paddlers.

• Capsizes account for a higher proportion of incidents than in other studies.

There are a number of recommendations arising from this study.

Personal skill proficiency of paddlers appears to be relatively low. Sea skills certs issued by Canoeing Ireland indicate that 837 of paddlers have been certified as having attained a level 3 sea proficiency (85% of sea skills certs awarded). For level 4 and level 5 sea skills this drops to 13% and 2% respectively. This dramatic drop off in awards at higher levels may mask a number of issues, though it would indicate there are considerably less higher level skills paddlers who took the survey. Colloquially this would appear to mirror the skill level of those on the ground. More worryingly almost a third of respondents indicated that they had no formal qualifications, yet almost half of this cohort indicated that they considered themselves to be advanced paddlers, though some hadn’t even undertaken informal training. This view would be supported by the qualitative data analysed in the survey.

Skill or personal proficiency is an issue that needs addressing. Some appear to equate skill with experience. Many sea paddlers may be experienced but may lack good close quartering skills or may never capsize

and consequently may not be able or have lost the ability to roll. Hence, though very experienced they may not be very skilful.

Around Ireland, there are a number of clubs / associations that operate “peer paddles”. This begs the question what is a peer? Is a peer someone of the similar age / interests / Paddling skills / etc. It is unlikely that the demographics of these peer paddling communities is very different to the certificate data provided by Canoeing Ireland, which is also broadly reflective of data collected in this survey. However, the breakdown in perceived skill levels indicated by participants with no formal qualifications in this survey is almost the inverse to data provided by Canoeing Ireland. Is this an anomaly or do some paddlers have a false perception of their ability?

The high number of capsize incidents outlined in this study suggests that training surrounding rolling, self-recovery and rescue is an urgent issue that needs addressing. It is noteworthy from the literature that

“ ”

training surrounding rolling, self-recovery and rescue is an urgent issue

in some cases where fatalities were not due to impact or catastrophic trauma (e.g. hypothermia, heart attacks or other factors in the deceased personal medical history), the stressor was the casualty being in the water for an extended period, and their inability to roll, or the group’s inability to rescue the casualty quickly.

To conclude, sea kayaking incidents are multifaceted and rarely occur suddenly and come as a surprise, when reviewed. There are usually a series of minor events (flags) that if ignored may begin compounding and impacting upon each other that will result in an incident. The ability to anticipate these minor events and constant dynamic risk assessment is key to avoiding or minimising the impact of incidents.

Most incidents in examined in this study were the result of poor planning or bad judgement and decision making, leading a group into a situation where environmental conditions were beyond the skill or experience competency of the group – poor situational awareness as described within the literature. The fact that many incidents also occur in venues that paddlers are familiar with, may suggest that complacency may also be an issue. Complacency, particularly among experienced paddlers has been identified as an issue in sea kayak incidents elsewhere in the literature.

Aadland, E., Vikenr, O. L., Varley, P., & Moe, V. F. (2017). Situation awareness in sea kayaking: towards a practical checklist. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 17(3), 203-215.

Bailey, I. (2010). An Analysis of Sea Kayaking Incidents in New Zealand 1992-2005. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, 21, 208-18.

Brown, G. (2014). An examination of the incidents occurring in sea kayaking and how coaches deal with them. Stirling.

Morley, S. (2014). When it all goes wrong. In C. Cunningham, Sea Kayaker’s More Deep Trouble (p. 309). Blacklick: Mc Graw-Hill Education.

National Incident Database. (2012). National Incident Database 2012 Report. New Zealand Mountain Safety Council.

National Incident Database. (2017). Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved from National Incident Database: https://www. incidentreport.org.nz/faq.php

Priest, S., & Gass, M. (2005). Effective Leadership in Adventure Programming. Human Kinetics.

Ray Mc Cullagh was born in Dublin but discovered a passion for sea kayaking on the West coast of Ireland. He also enjoys mountaineering, whitewater kayaking and canoeing, but believes the sea and coastline around Ireland offer the best opportunities to have wild and remote experiences that are best enjoyed by sea kayak.

Kevin O’Callaghan, lectures on the BA(Hons) in Outdoor Education, at the Mayo Campus of the Galway Mayo Institute of Technology. He has been adventuring for a long time and was one of the founding members of the Irish Sea Kayaking Association.

Treasna na dTonnta is the e-zine of the Irish Sea Kayaking Association. It is edited by Sue Honan and produced by Adam May’s team at Language.

We are grateful to the following paddlers who kindly wrote for this issue and/or provided photos:

• Brian Barry

• Gene Cahill

• Dave Conroy

• Marty Corbett

• Nick Crowhurst

• David Fenwick

• Liz Gabbett

• Eleanor Honan

• Ray McCullagh

• Brian J McMahon

• Eileen Murphy

• Kevin O’Callagahan

• Erik Sjöstedt

TnadT welcomes articles and photos.

– Send as a Word document

– Please send photos separately, at high resolution if possible. 300 dpi is ideal.

– Please caption all photos giving location, situation, naming people visible in them if you can

– Use headings if you like but there is no need to format the document layout for us

– Have fun writing!

Thank You.