Judy Chicago

Agnes Martin

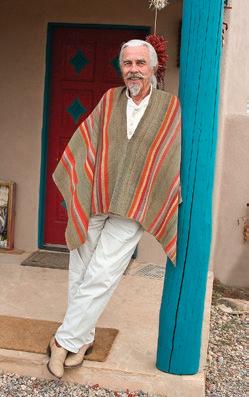

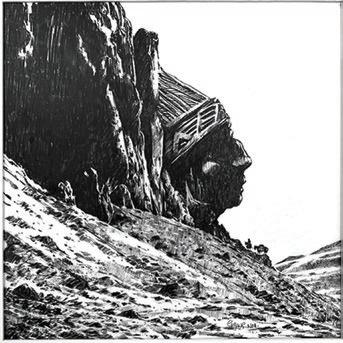

Bart Prince

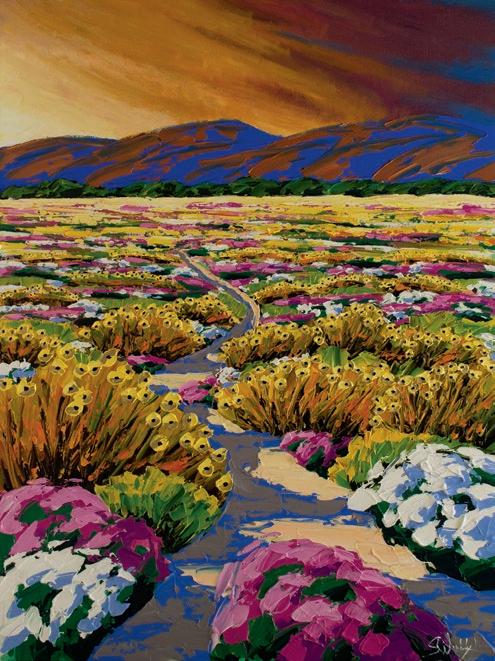

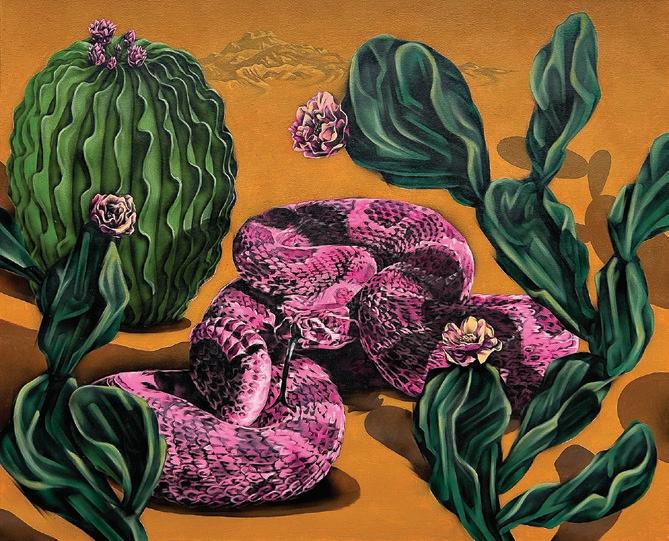

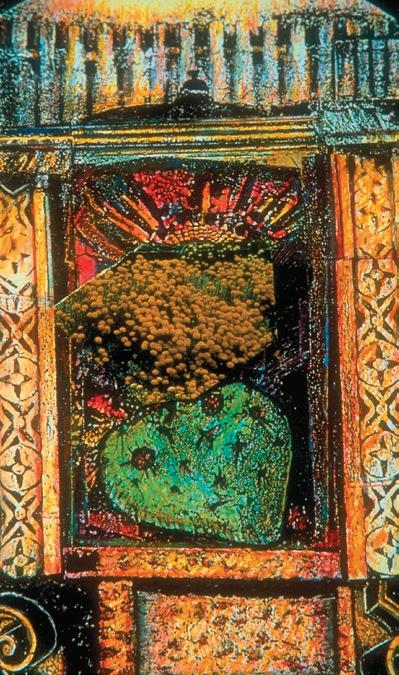

Carlos Carulo

Erin Currier

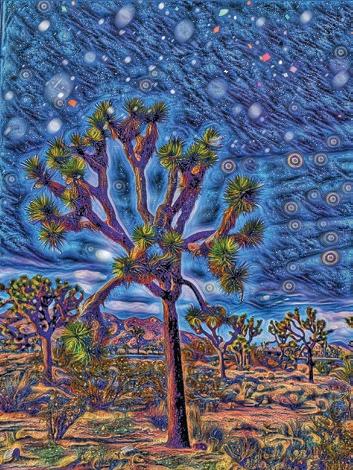

Dennis Hopper

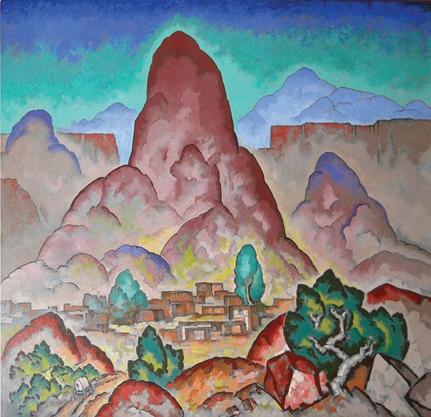

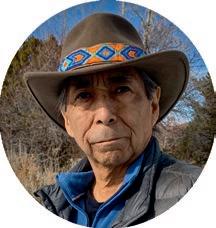

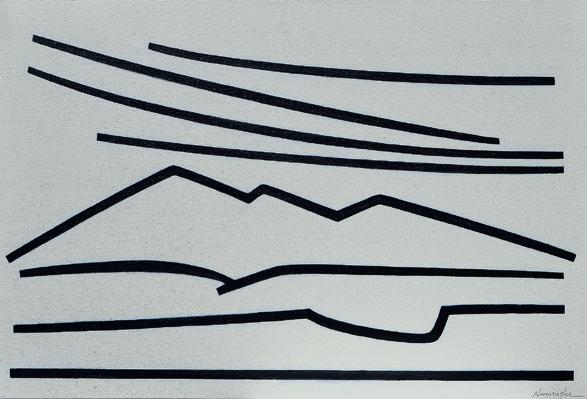

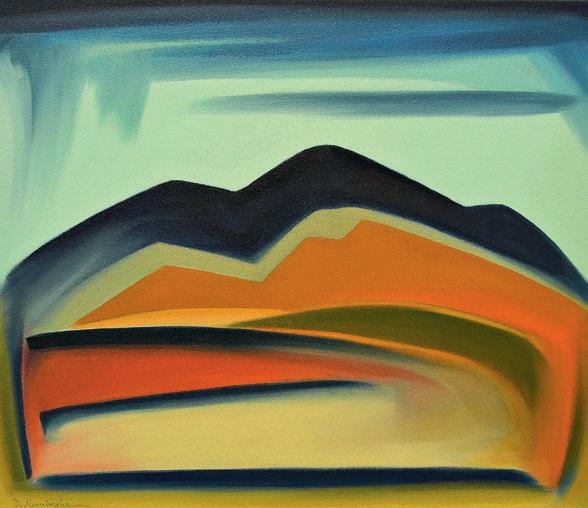

The Naminghas

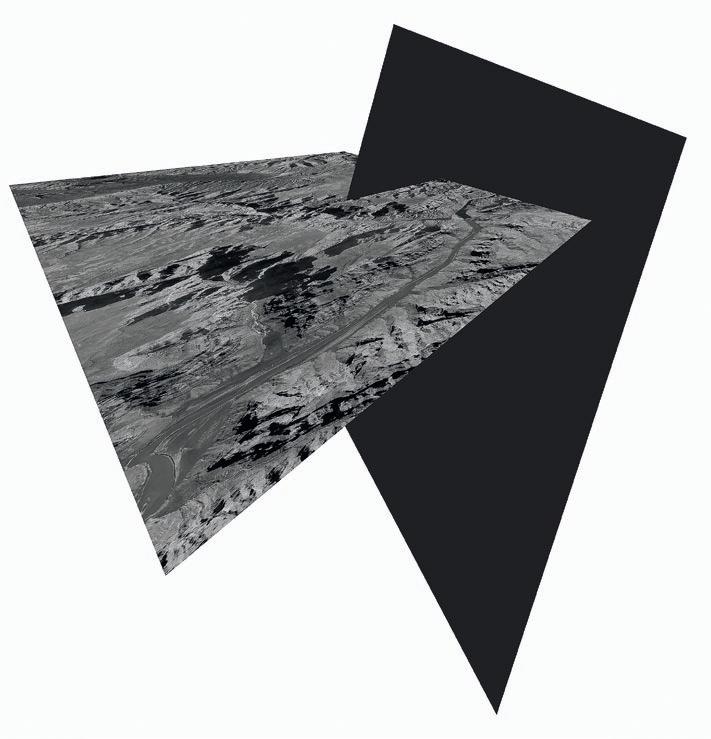

Antoine Predock

Alexander Girard

Larry Bell

Emmi Whitehorse

James Havard

Eli Levin

Terry Allen

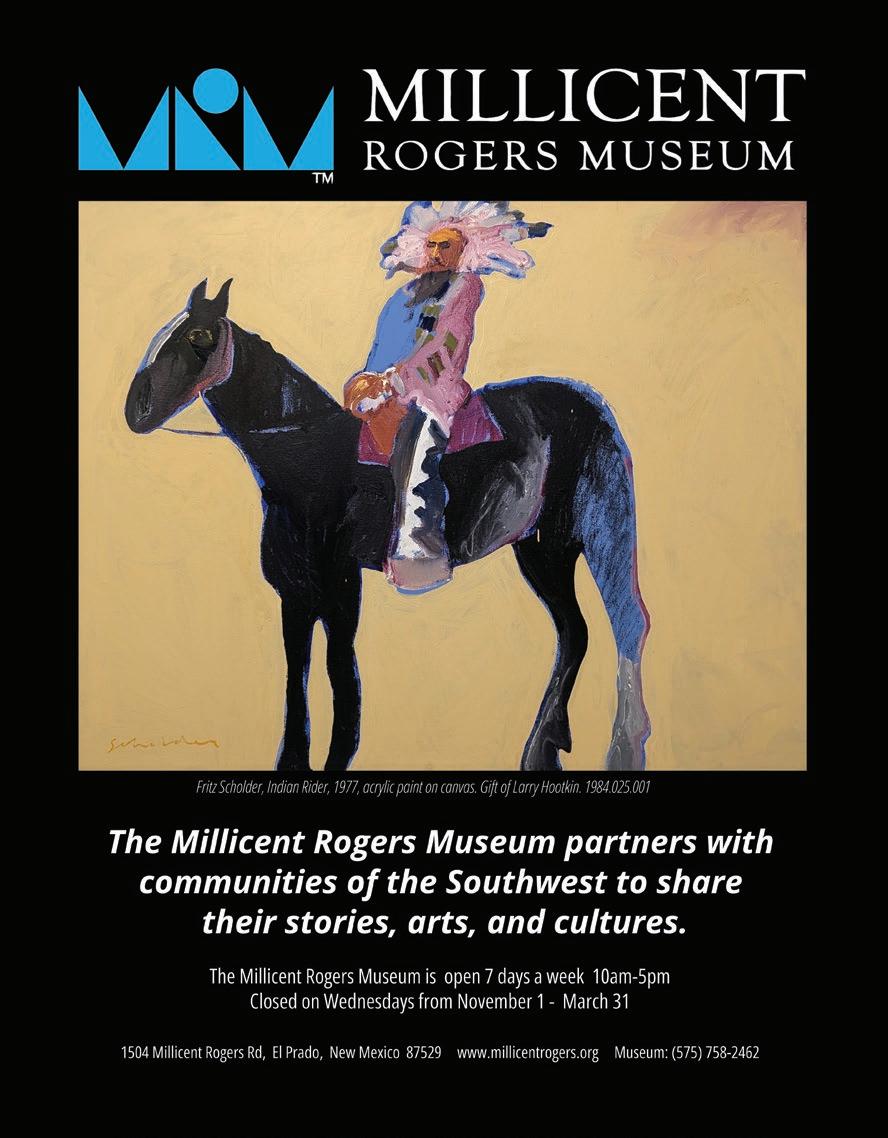

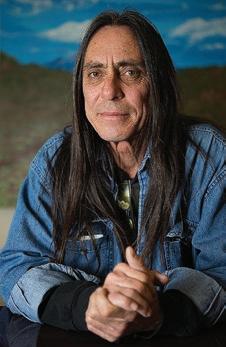

Fritz Scholder

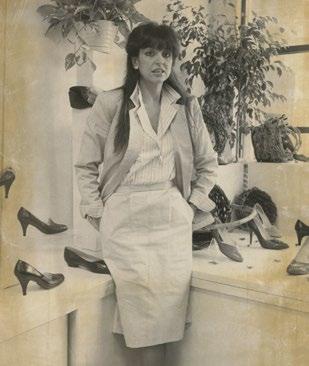

Riva Yares

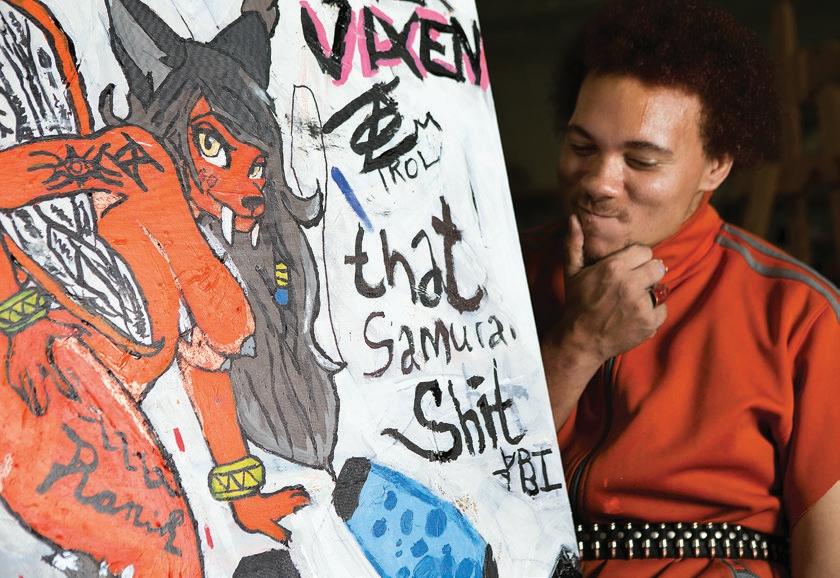

Meow Wolf

Madeleine Gehrig

Peter Sarkisian

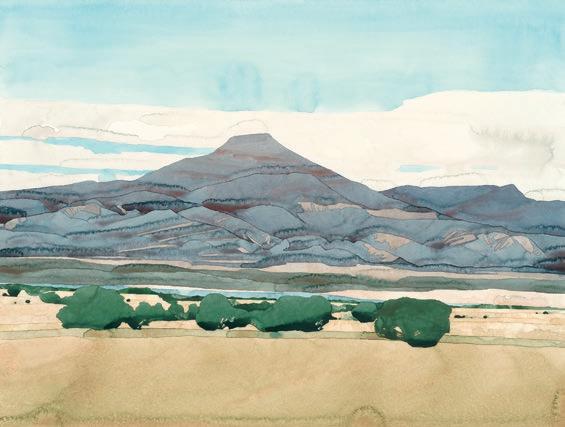

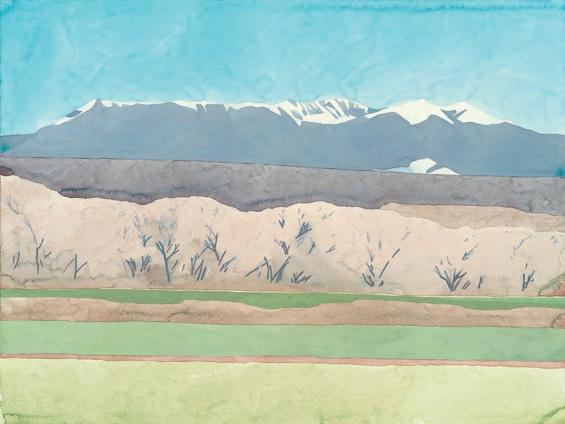

Woody Gwyn

Florence Pierce

Michael Krupnick

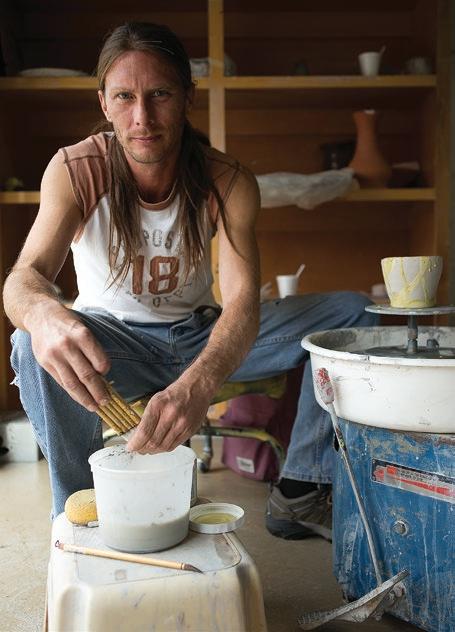

Cody Sanderson

Kristin Diener

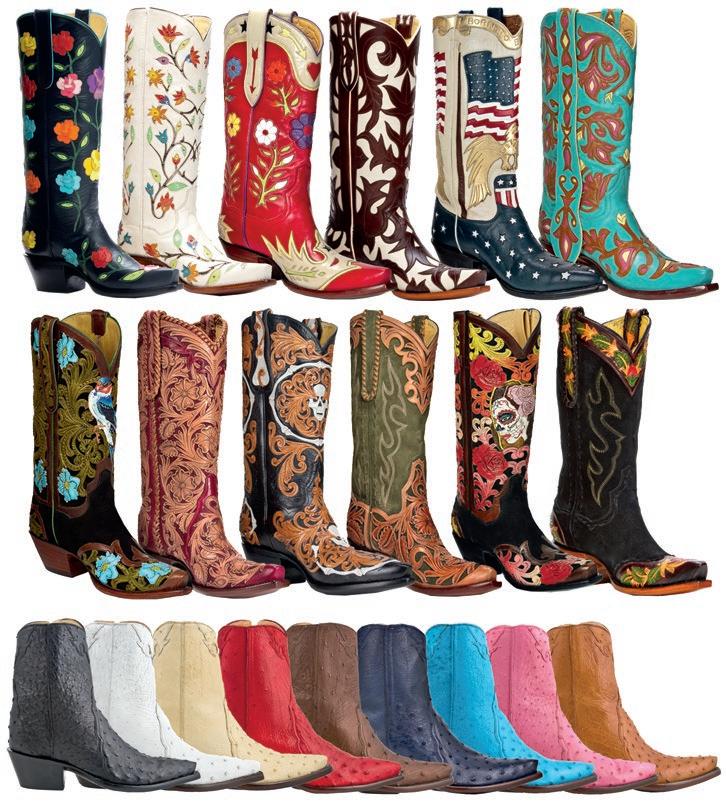

Nestled in the heart of one of the most historically significant buildings in Santa Fe, the Casa Sena, you will find Goler Shoes, a small, bustling boutique that has become a popular Santa Fe fashion hub. Part of its charm is no doubt due to owner Guadalupe Goler, who, after 40 years at the helm, still enthusiastically engages with customers when she’s not busy stocking the store with an everchanging selection of fine imported shoes, boots, clothing, and accessories for men and women. Brands include United Nude, Thierry Rabotin, Onfoot, Caddis, and Planet.

Guadalupe was only 28 years old in 1984 when she decided to bring fashion footwear to Santa Fe, a natural vocation for a woman whose grandfather and father had been in the shoe manufacturing business in Guadalajara, Mexico. Guadalupe quickly found her niche and her people. Her natural social skills and her ability to make people feel welcome both in and out of her shop have also played a large role in her success.

As has her family, who have helped her ride the myriad waves of change over the past 40 years. Whether it’s Guadalupe’s brother, her daughter, her son, or her grandkids, everyone plays an important part in keeping the business healthy and its legacy strong. So too do longtime salespeople and patrons, all of whom are also considered family.

Says Guadalupe’s daughter, Paula, “Goler is more than shoes, clothing, or accessories. Goler is an aesthetic, a vibe, and an experience.” Goler is also accessible to everyone. “Fashion is not exclusive—it’s an important means of expression.”

With Goler celebrating 40 years in business this year, it is Guadalupe’s greatest pride to see the continuation of her legacy to bring fun, fashion, and family connection to Santa Fe shoppers. golershoes.store | 125 E Palace Ave # 125, Santa Fe, NM 87501 | 505-982-0924

“Jack

JENNIFER

Twilight 5' high Edition of 9

Call to schedule studio/showcase visit. Open 6 days a week. Closed on Thursdays.

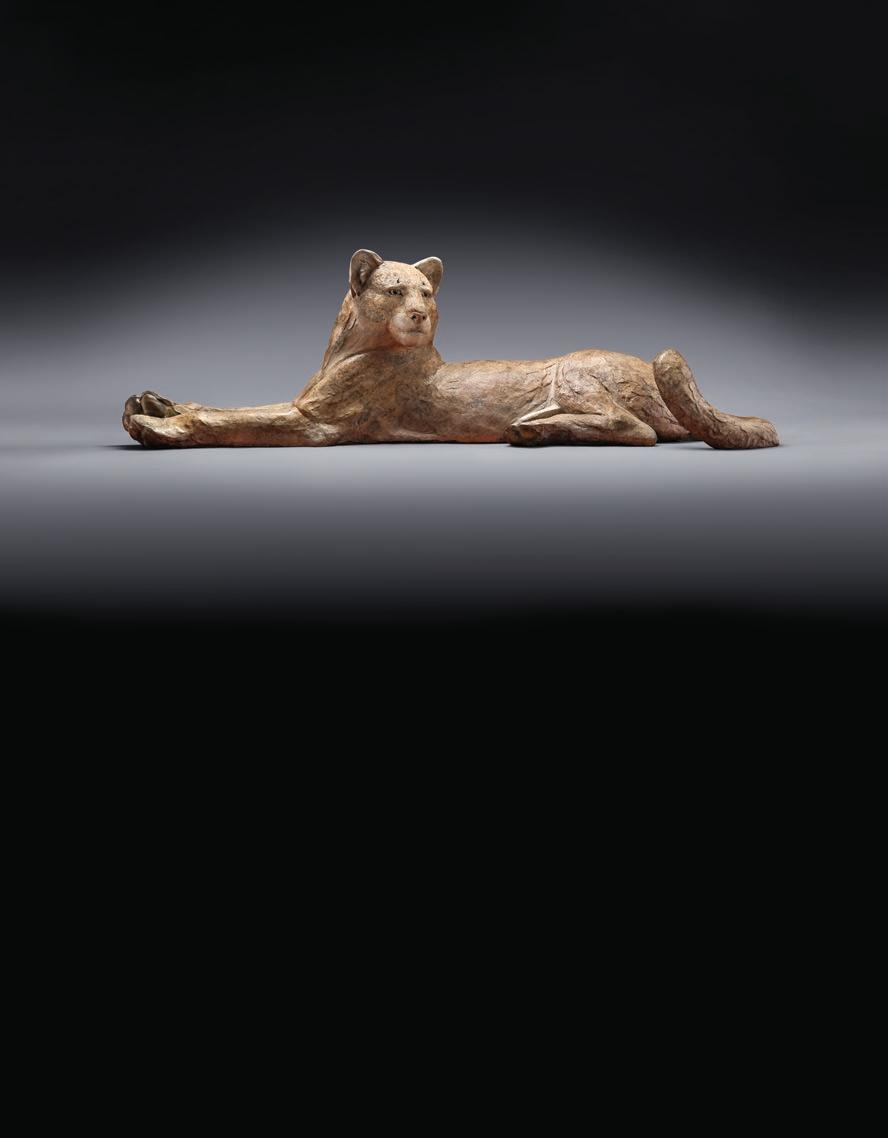

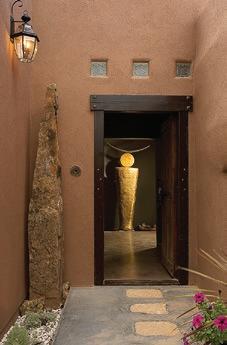

Famed sculptor David Pearson is best known for his exploration of the female form. His elongated, ethereal bronze figures, inspired by the ancient cultures of Egypt, Africa, and Asia, appear as if out of a dream or myth. A goddess, an angel, a muse, a nymph—all transcend ordinary reality, transporting the viewer to a space beyond time and place.

Pearson began sculpting at the age of 16, learning his craft at Shidoni Foundry in Tesuque, where he cast works for established masters, including Allan Houser. Despite being exposed to many sculptural influences, he developed his own style, imagery, and techniques, creating works that have drawn enthusiastic collectors from around the world.

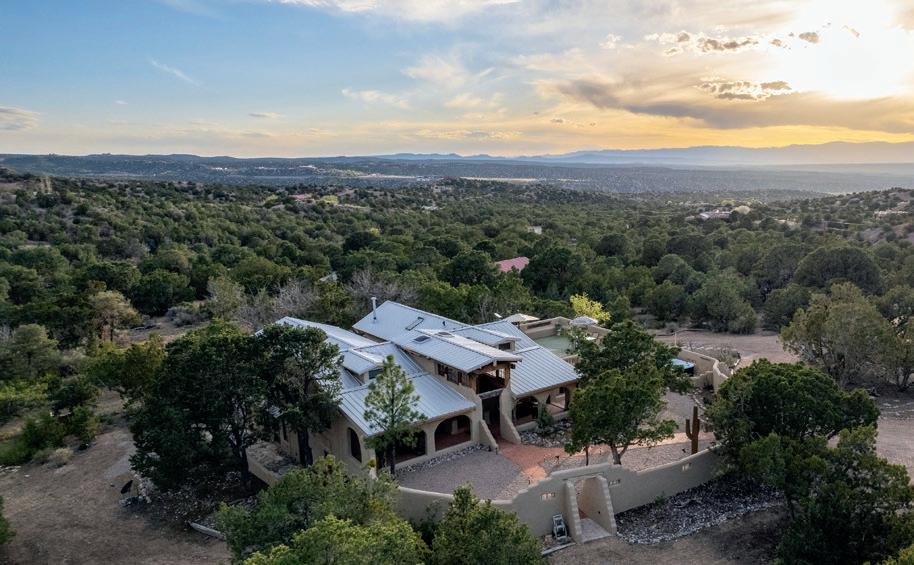

Pearson was for many years represented by Patricia Carlisle Fine Art, his wife’s gallery in Santa Fe, which she established in 1997. In 2021, with Pearson now a nationally recognized, award-winning artist with an extensive customer base, the couple decided to move the gallery to their home, a peaceful rural retreat off the historic Turquoise Trail.

How does an established fine art gallery on iconic Canyon Road in Santa Fe metamorphose into a home studio and survive?

“Extraordinarily well,” Carlisle says. “We offer members of our huge customer base an opportunity to come out to David’s studio and experience the artist’s thinking and working processes and to see the many steps involved in the creation of a finished sculpture. We have a steady stream of clients and visitors, many who have become friends because this isn’t just a gallery visit, it’s a very private and personal experience. No one walks away unmoved by David’s dedication and total commitment to his art.”

carlislefa.com | Patricia Carlisle Fine Art, Inc. | Pearson Studio & Sculpture Garden 5 Sculpture, Santa Fe, NM 87508 | 505-820-0596

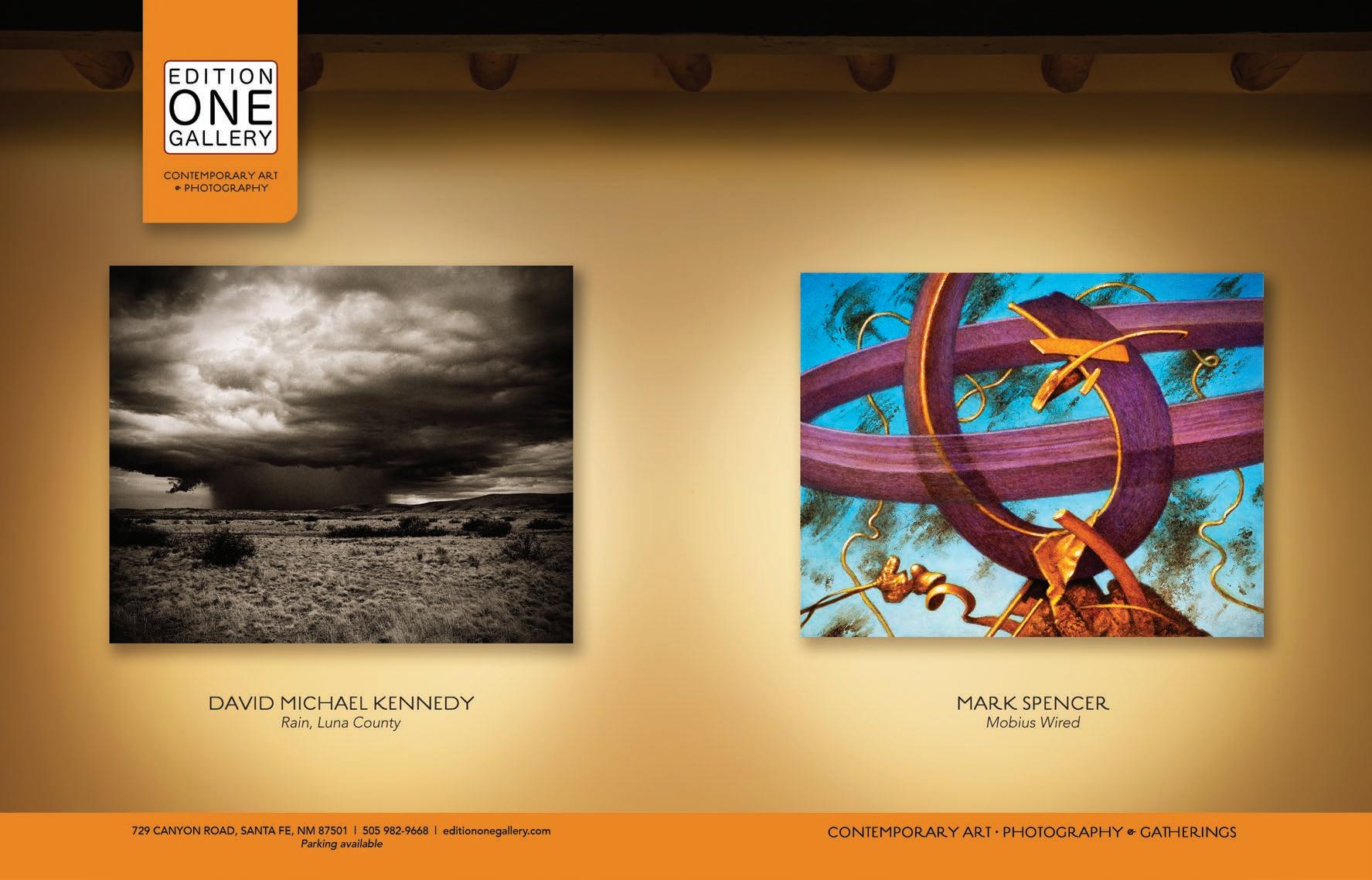

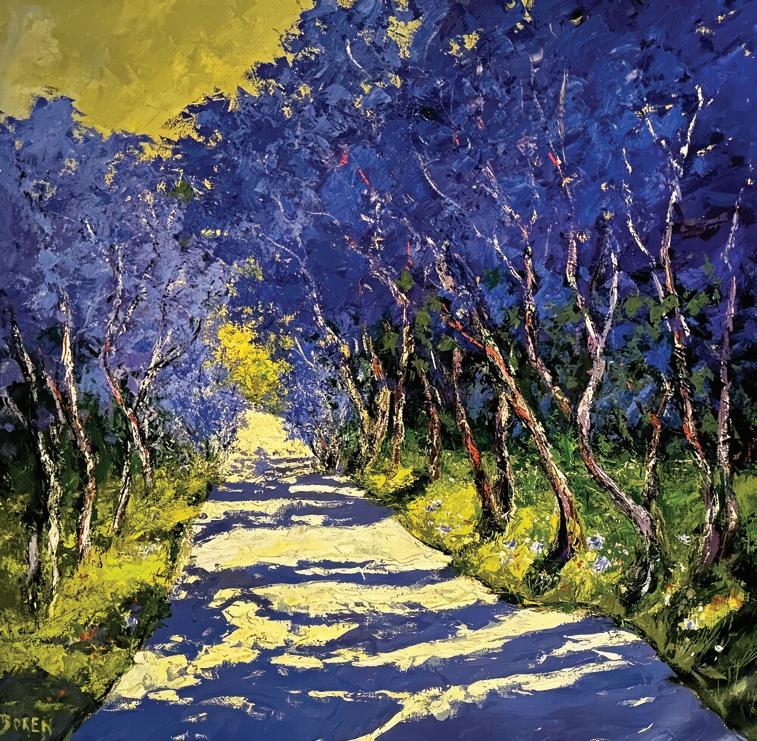

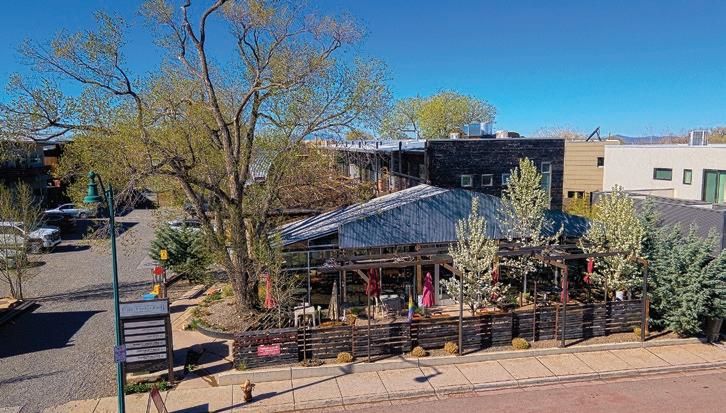

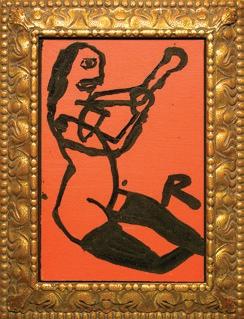

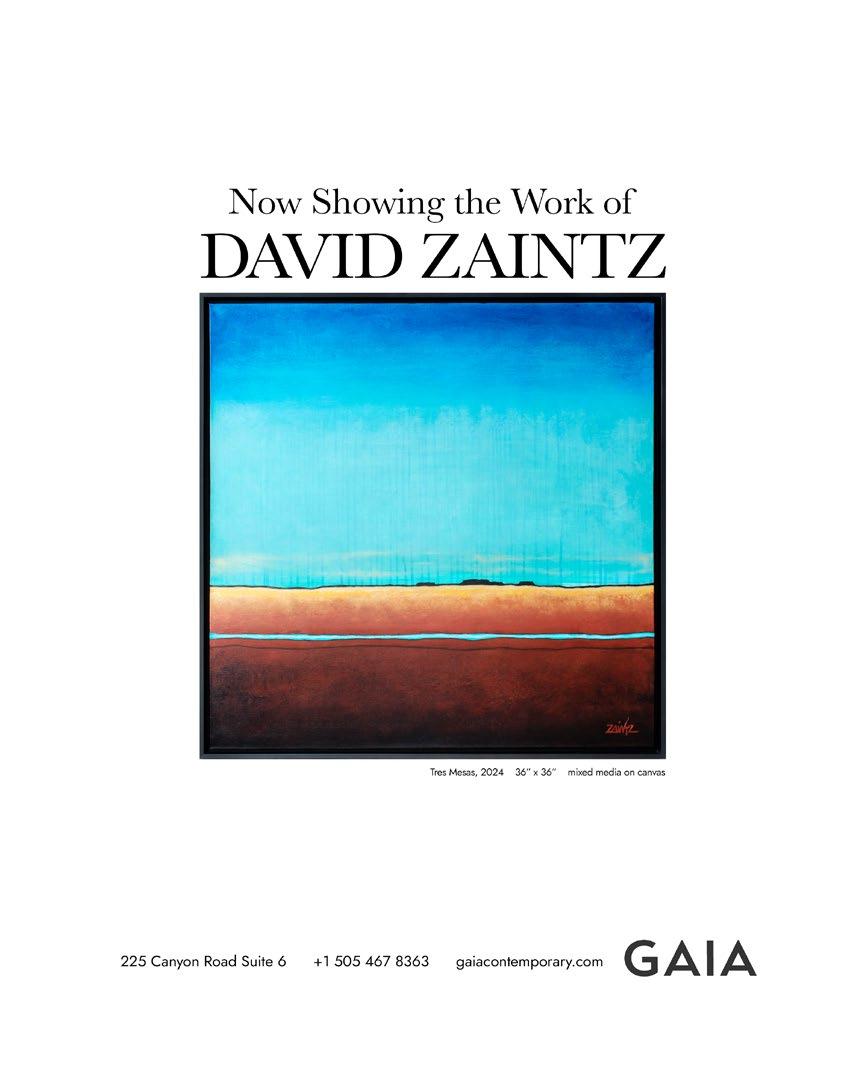

Acosta Strong Fine Art is the first gallery at the beginning of Canyon Road, and that prime location is something that co-owner Carlos Acosta pays special attention to. “We make a point of showing a variety of different artists,” he says, “mixing old and new, historic and contemporary, to give people a taste of what Canyon Road has to offer.”

Unlike most galleries, Acosta Strong puts on shows once a month in order to promote one or more of its 16 artists, six of which have exclusive representation. “I love being the conduit for completing the circle of life of a painting,” Acosta explains, “from its creation by the artist to finding a home with the right collector.”

He is committed to his artists, each of whom has a distinctive voice, or as he puts it, “brings something to the table.” They are always there for shows that promote their artwork, and some collectors even fly in from out of state as well. “Building relationships is something that really matters to us,” says Acosta, “and most of our collectors have met the artists and seen their paintings, which then makes it easier for them to relate to images on a screen.”

Something else that sets this gallery apart is that every artist has their work shown in a distinctive frame, handmade in gold metal leaf by a local frame-maker—another indication that the gallery is clearly invested in supporting its artists for the long-term.

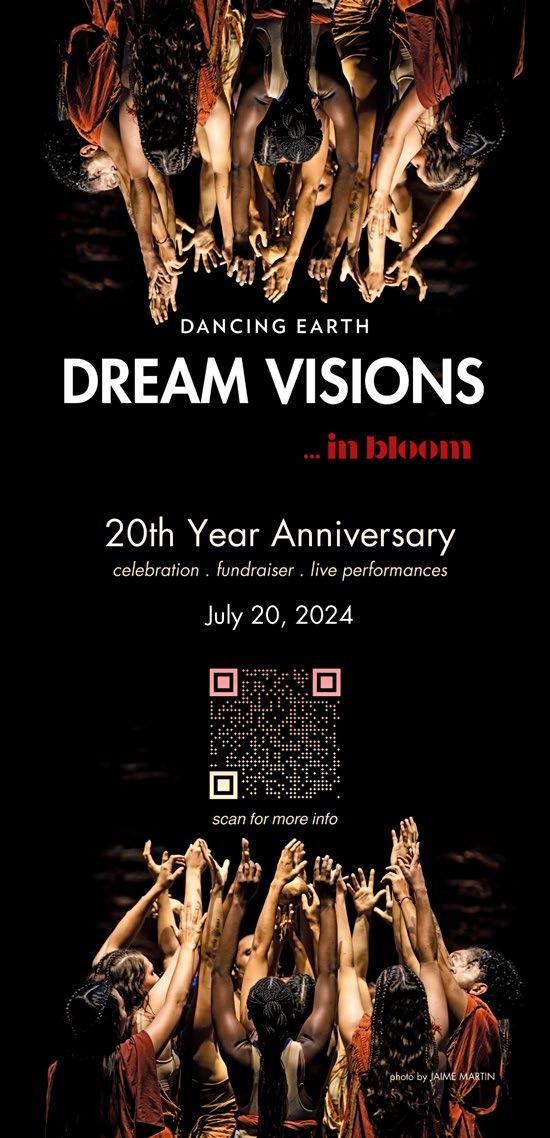

SITE SANTA FE, the city’s dynamic interdisciplinary contemporary arts institution, places artists at the center, collaborating with them to explore extraordinary ideas through innovative installations and programs. From its founding in 1995, notable artists invited to exhibit include Bruce Nauman, Deborah Roberts, Pedro Reyes, Shirin Neshat, Graciela Iturbide, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Raven Chacon, Doris Salcedo, Agnes Martin, Mungo Thomas, and others.

This year, in addition to regular exhibitions, the organization is preparing for 2025’s 12th International, where artists and curators, both local and from around the world, will respond to the unique geography, history, and cultures of New Mexico. Since its first edition in 1995—at the time the only community-wide, U.S.based, international biennial of contemporary art—the

International has collaborated with 331 artists and 21 curators in a forum for the most groundbreaking ideas in contemporary art.

“We’re excited that Cecilia Alemani will curate our 12th International, the first we’ve mounted since 2018,” says Louis Grachos, SITE’s Phillips Executive Director. The director and chief curator at High Line Art in New York City, Alemani also served as artistic director of the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022. “She’s the fourth curator to organize both, and as a champion of the voice of the artist her curatorial approach fits seamlessly with our artist-centric vision. We look forward to the new works, ideas, and dialogues that will emerge from her curatorial vision.”

SITE SANTA FE has free admission and is open to the public Thursday through Monday.

ON VIEW AT SITE SANTA FE:

TERESITA FERNÁNDEZ / ROBERT SMITHSON

07.05 - 10.28.2024

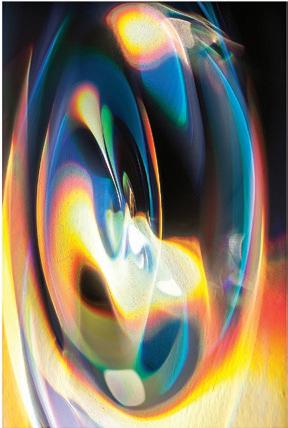

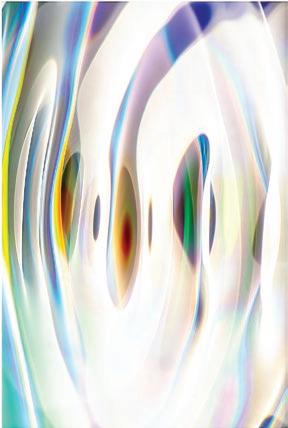

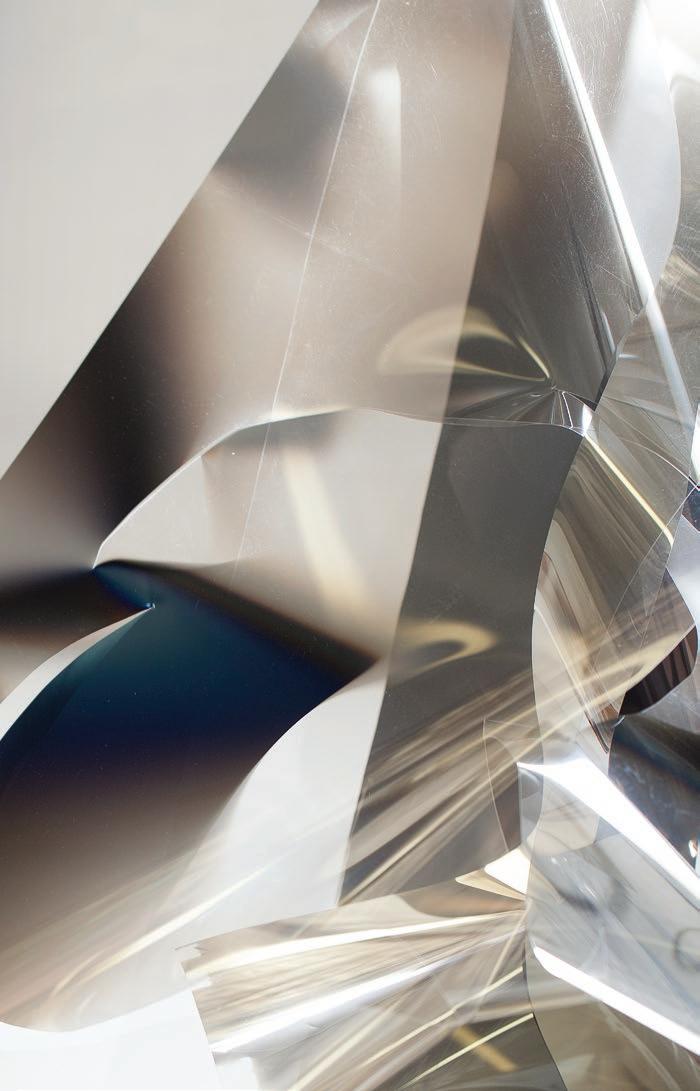

TRISTAN DUKE: GLACIAL OPTICS

09.27 - 01.13.2025

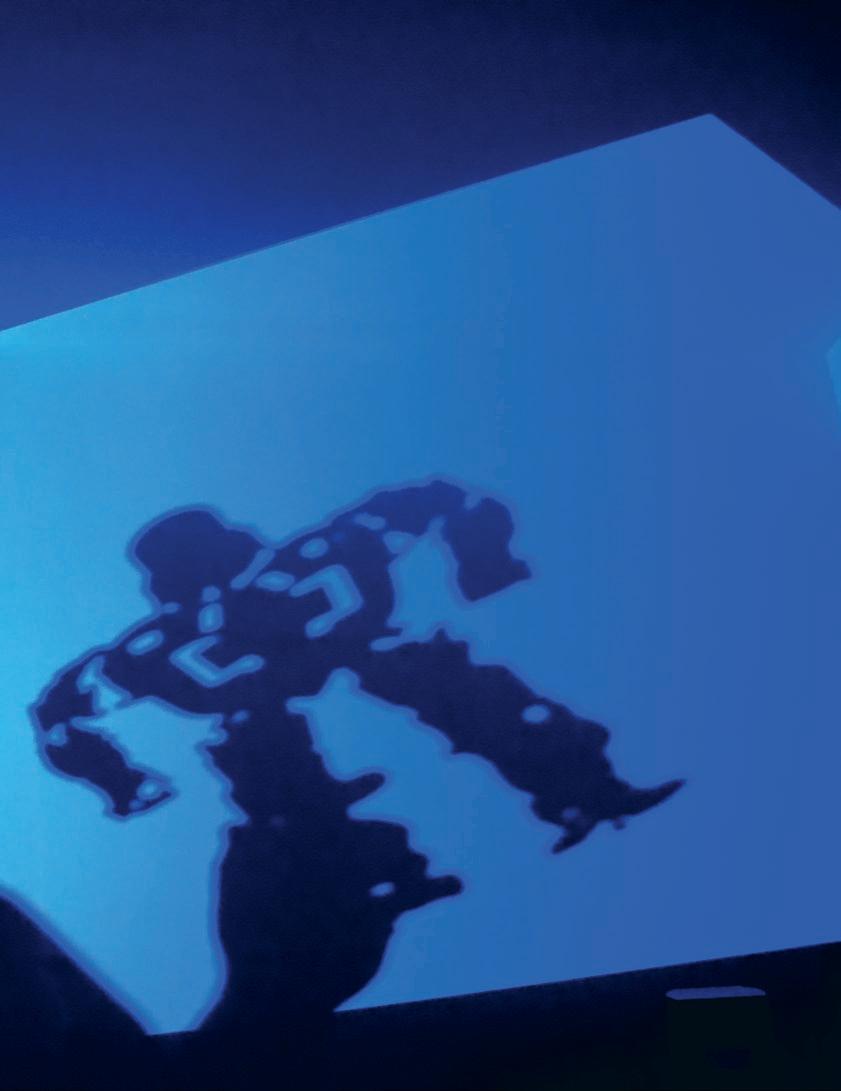

CASSILS: MOVEMENTS

11.15 - 02.23.2025

ERIKA WANENMACHER: WHAT TIME TRAVEL FEELS LIKE, SOMETIMES

11.15 - 02.23.2025

DAKOTA MACE: DAHODIYINII – SACRED PLACES

02.28 - 05.19.2025

HARMONY HAMMOND

02.28 - 05.19.2025

12TH SITE SANTA FE INTERNATIONAL CURATED BY CECILIA ALEMANI SUMMER 2025 - EARLY 2026

1606 Paseo De Peralta | Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 | 505-989-1199 | sitesantafe.org

David DeStefano spends thousands of hours chiseling, hammering, and intricately grinding away at his stone sculptures until they become magnificent faces, torsos, or hands. And yet, in DeStefano’s case, the everevolving relationship between artist and material is much more. There’s respect. A reverence. A mutual understanding about birthing a form that embodies relational qualities such as candor and vitality.

DeStefano says: “There’s an honest world that exists inside the stone. Stones won’t initially reveal their natures, but if

Miracle of Life and Death, 90”x23”x22”, Texas limestone;

Bottom right: Mother and Child, 28”x23”x21”, Indiana limestone;

Bottom left: Work in progress, 85”x12”x12”, Indiana limestone

asked, they won’t lie—their answers are always honest.” For over 30 years, sculpting manifests expressive symbiosis for DeStefano and his pieces. Holding a hammer and chisel, and intently exerting his hands to convey flashed images he sees quietly nestled within blocks of stone or wood, brings him home.

“Life exists in and through stones,” DeStefano says. “Every angle and curve conveys emotion as told through shadow and light. My sculptures are guided by the emotional tone that already exists within them.”

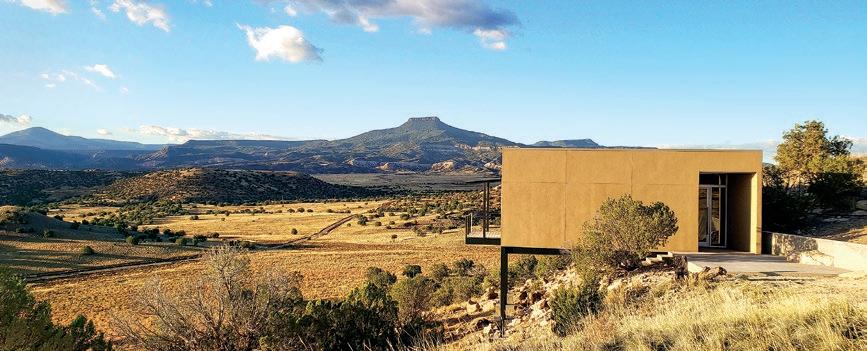

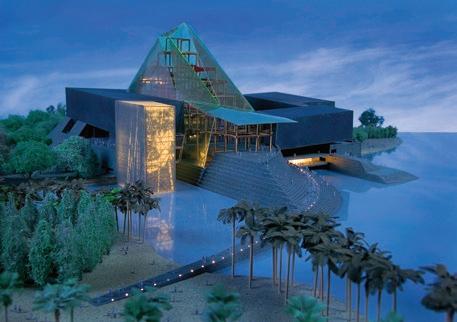

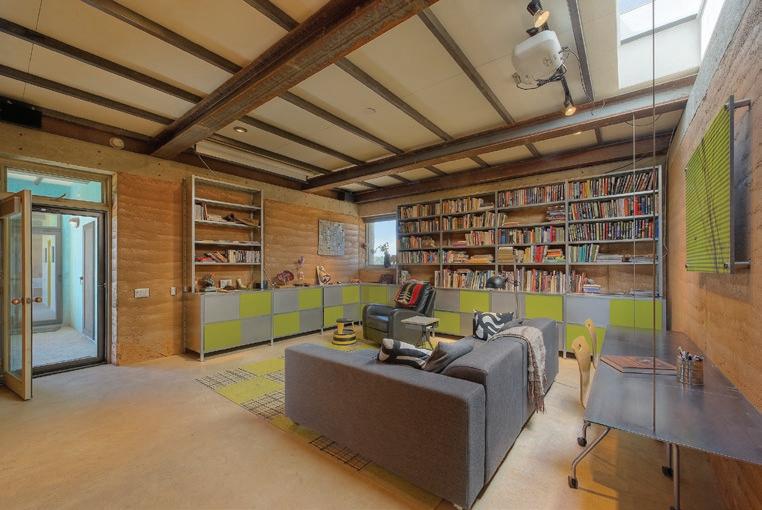

200 Antoine Predock

Architecture and Time

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By Ro B eR t Reck

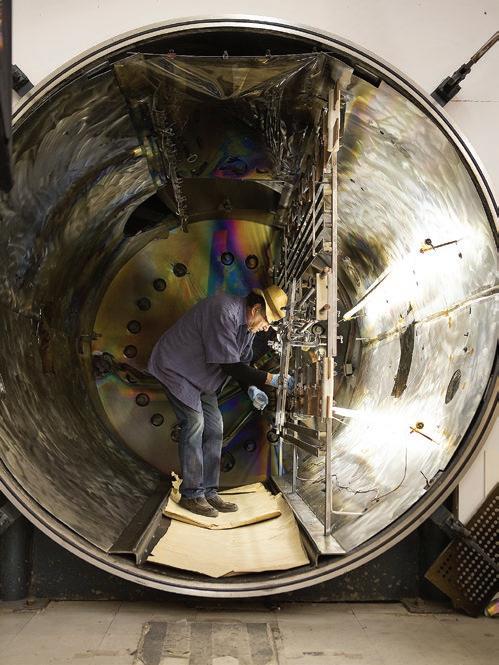

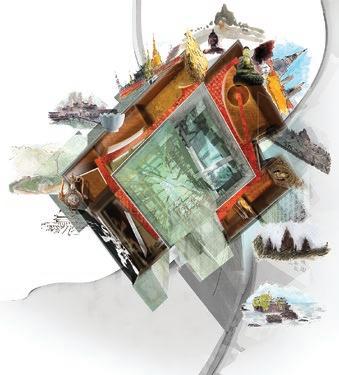

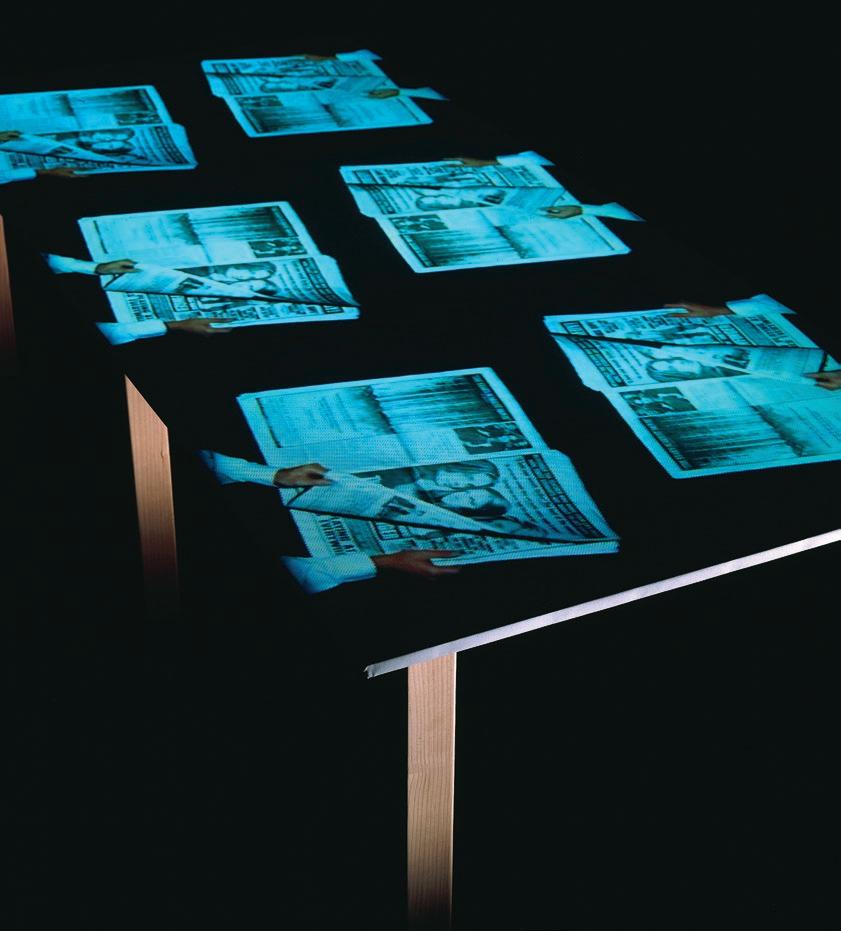

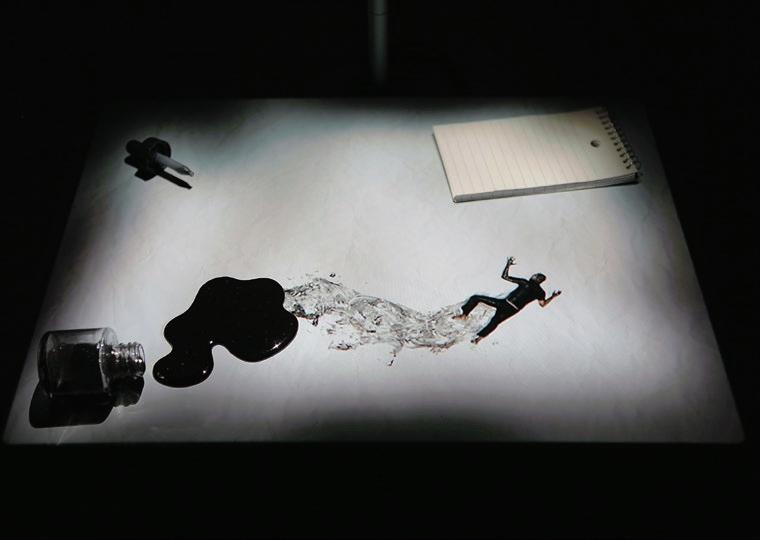

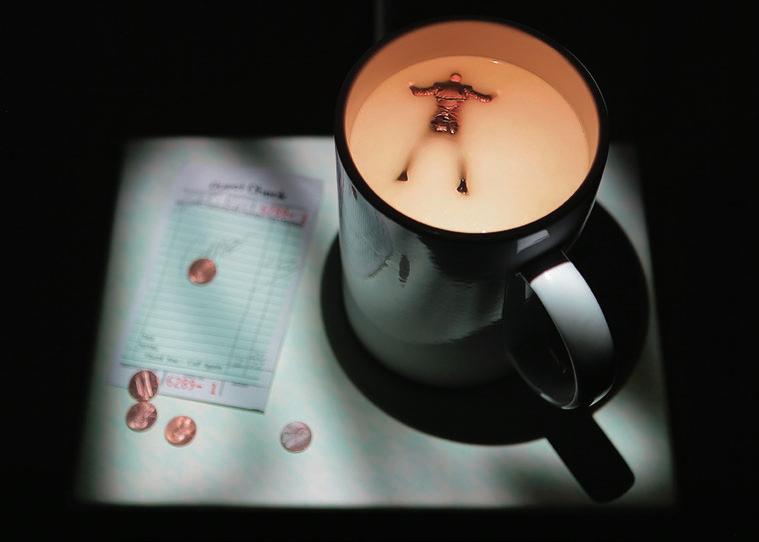

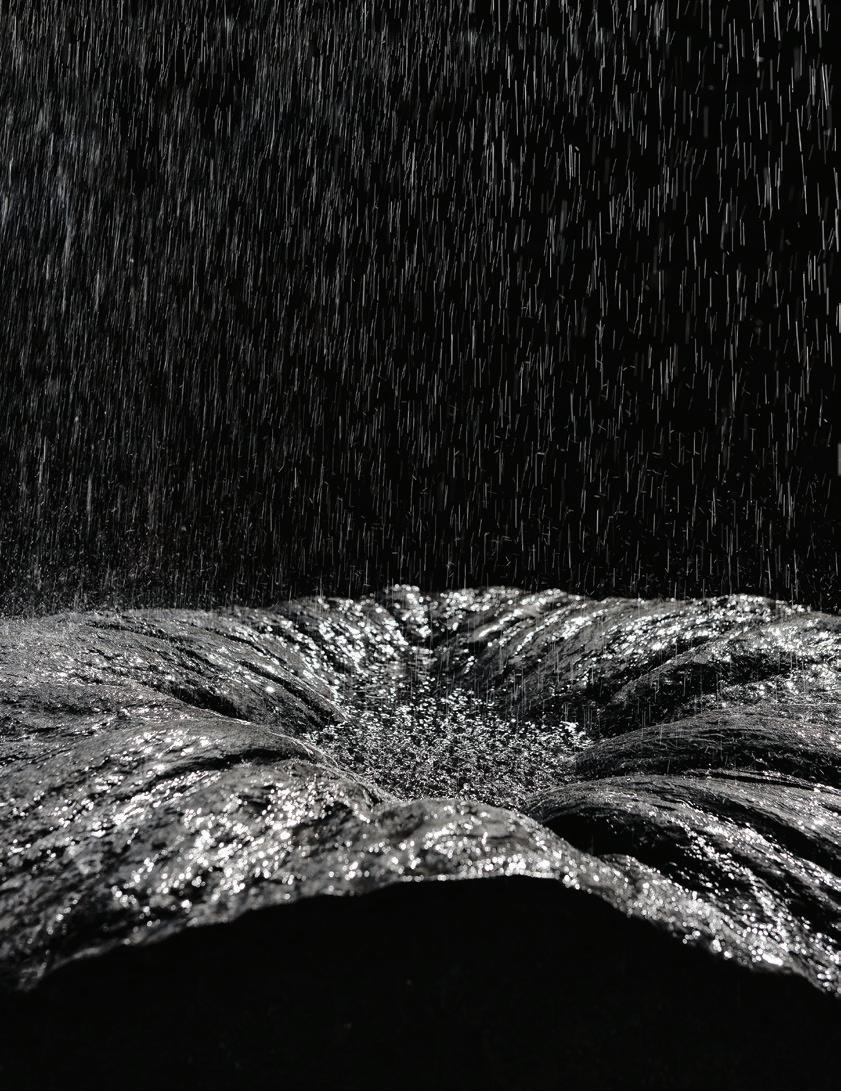

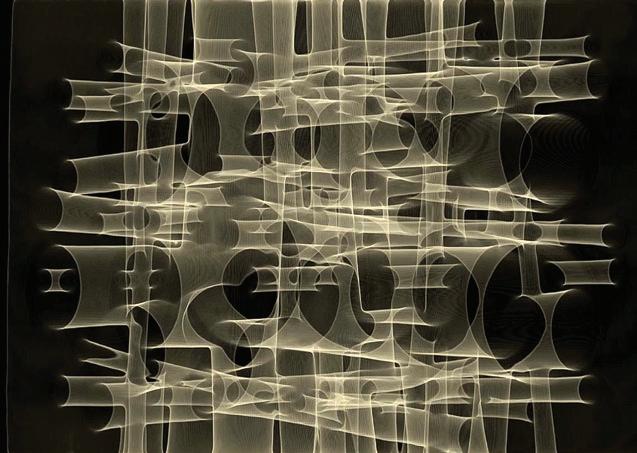

208 The Box Beyond

Peter Sarkisian turns TV sets into digital sculptures

B y D evon Jackson | Po R tR aits By JennifeR e sPeR anza

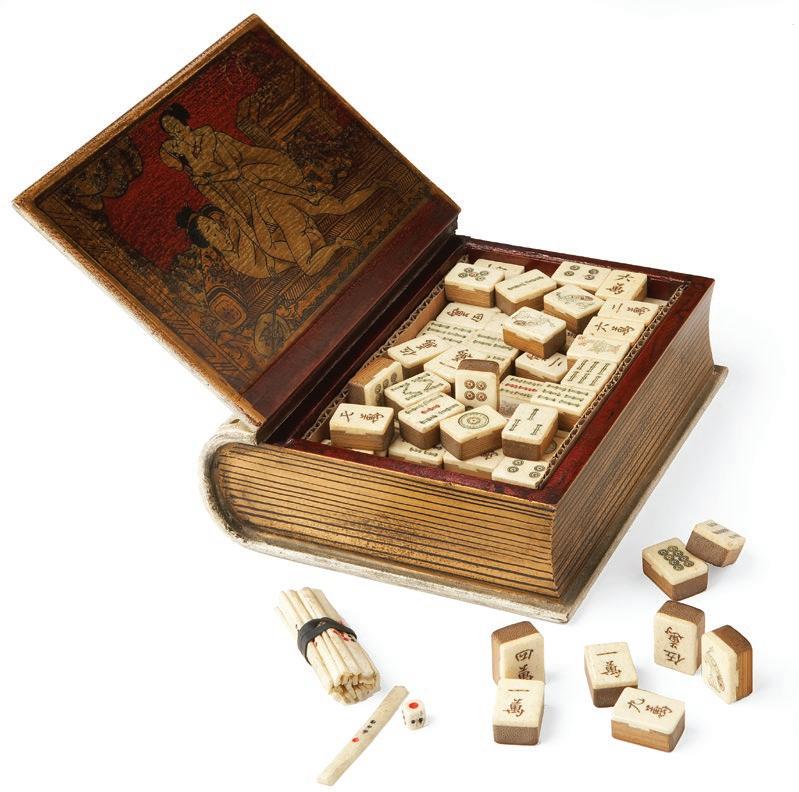

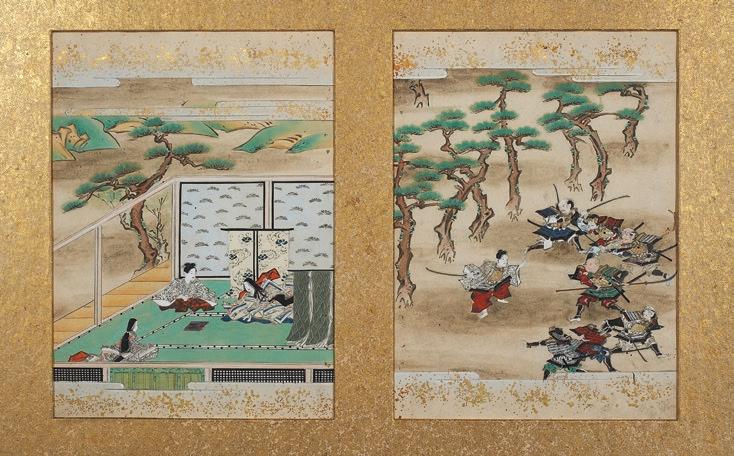

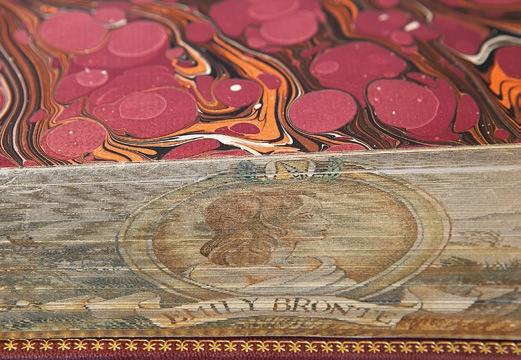

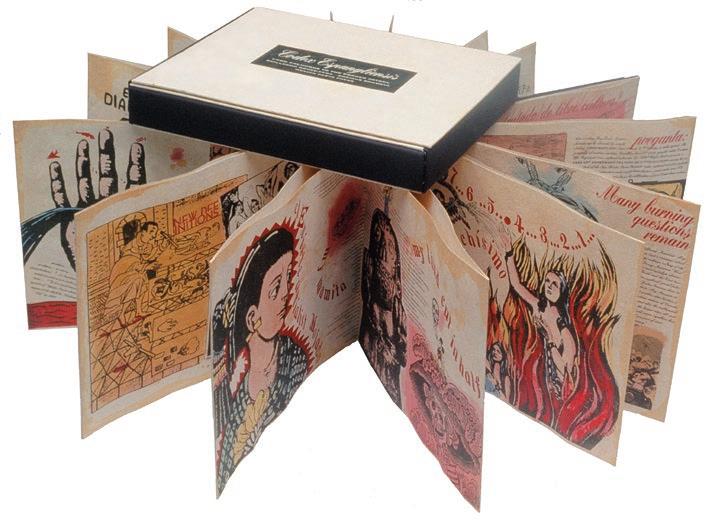

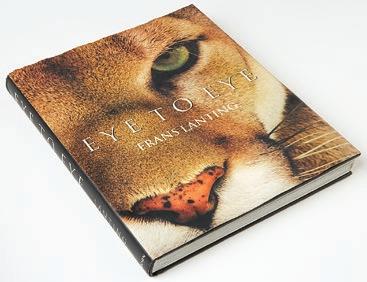

218 The Art of the Book

When art and literature converge, the result is a unique and compelling aesthetic experience

B y lynn stegneR

226 Queen of Interesting

The life, loves, and lasting impact of Riva Yares

B y D evon Jackson | Photos By k ate R ussell

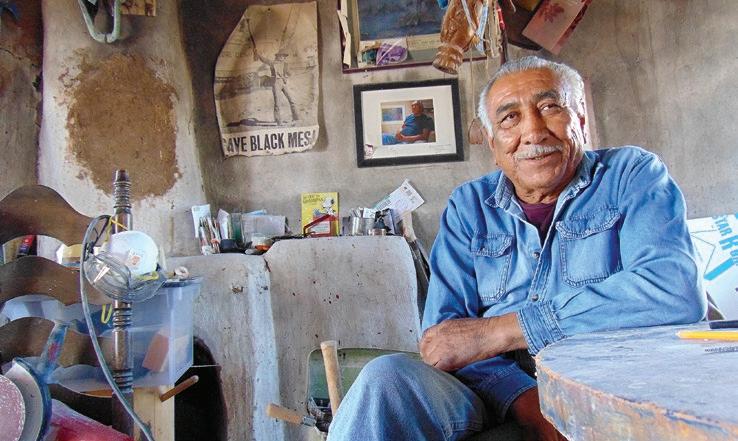

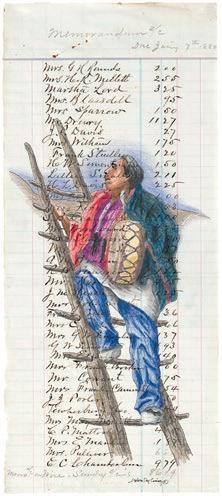

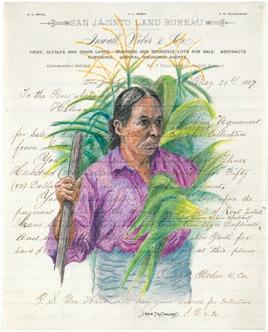

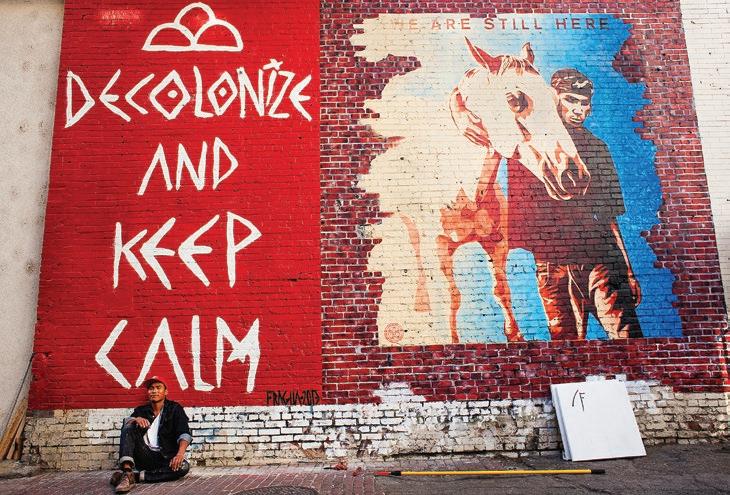

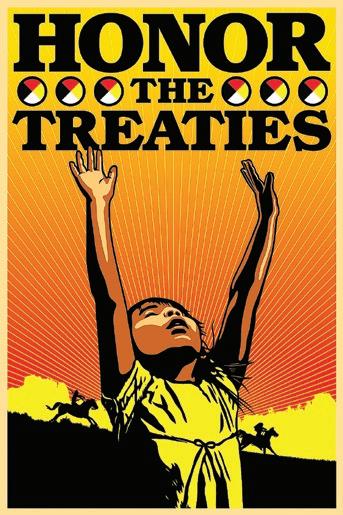

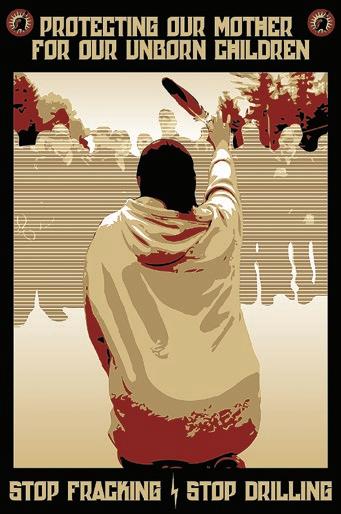

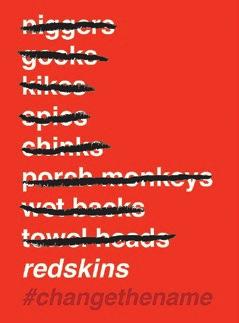

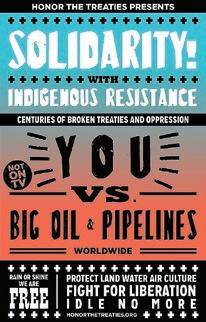

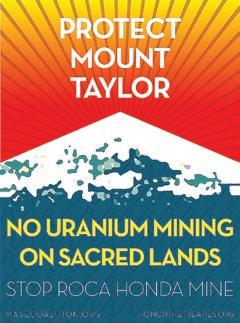

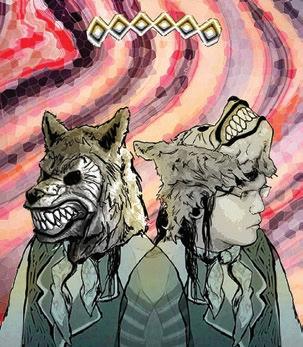

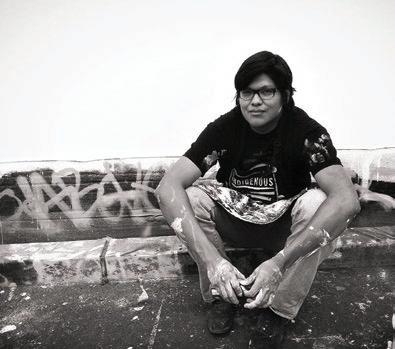

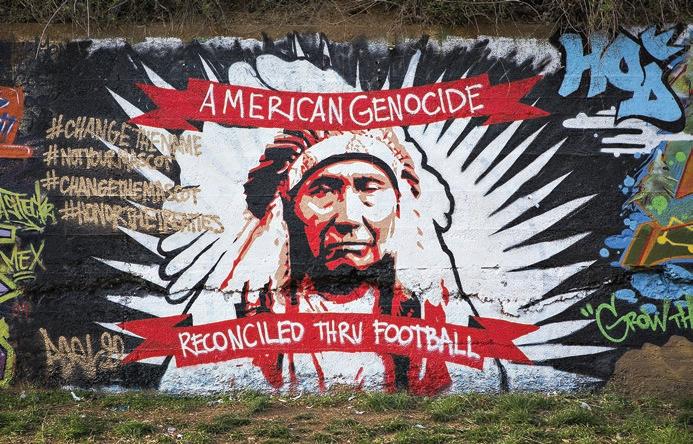

236 Taking it to the Streets

Native American street art sparks a dialogue about cultural and environmental issues

B y nancy zimmeRman

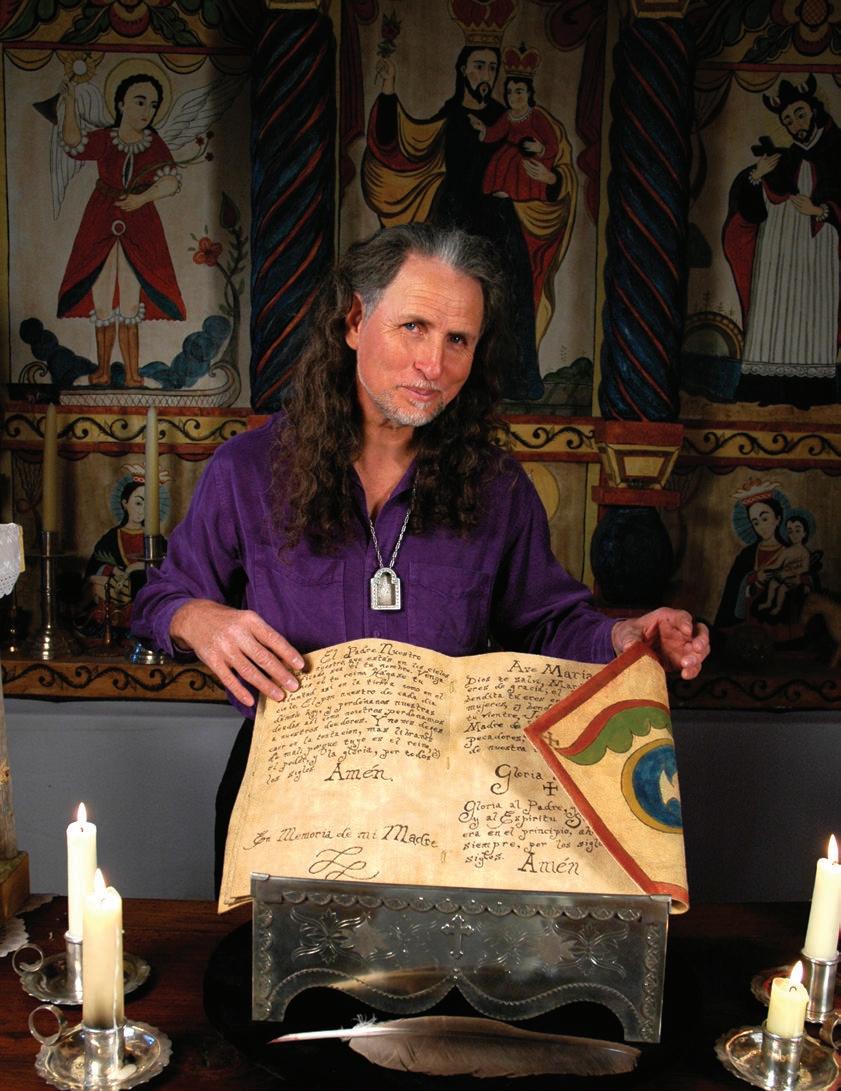

248 Santeros in a Time of Few Saints

Spanish Colonial arts reach a crossroads

B y k eiko o hnuma | Photos By PeteR o gilvie

256 Iron Will

Sculptor Tom Joyce fuses the art and science of metal making

B y chR istina PR octeR | Photos By PeteR o gilvie

268 Points of Connection

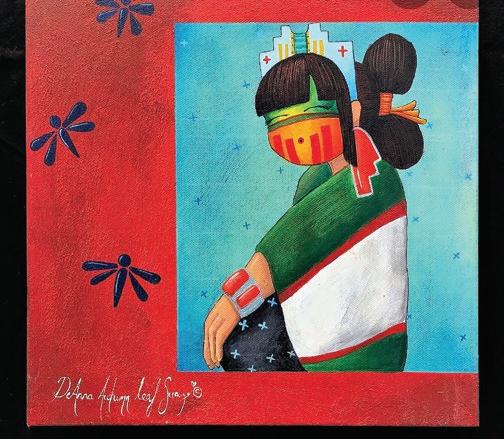

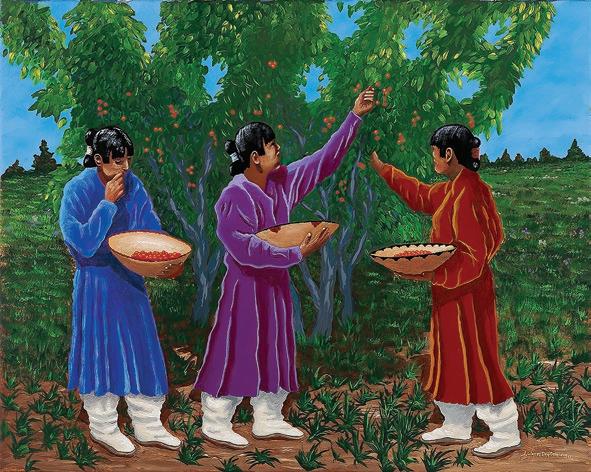

The Namingha family of artists blends ancient ways with a modern worldview

B y nancy zimmeRman | Po R tR aits By k ate R ussell

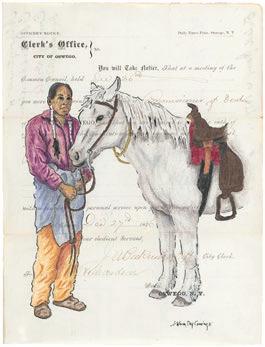

280 Artistic Identity in Native America: What’s in a Label?

Art patrons tend to keep Indian artists in a cultural box that marginalizes their talents

B y PeaR l tiR esias | Photos By B R enDa k elley

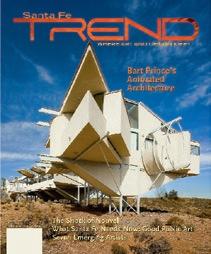

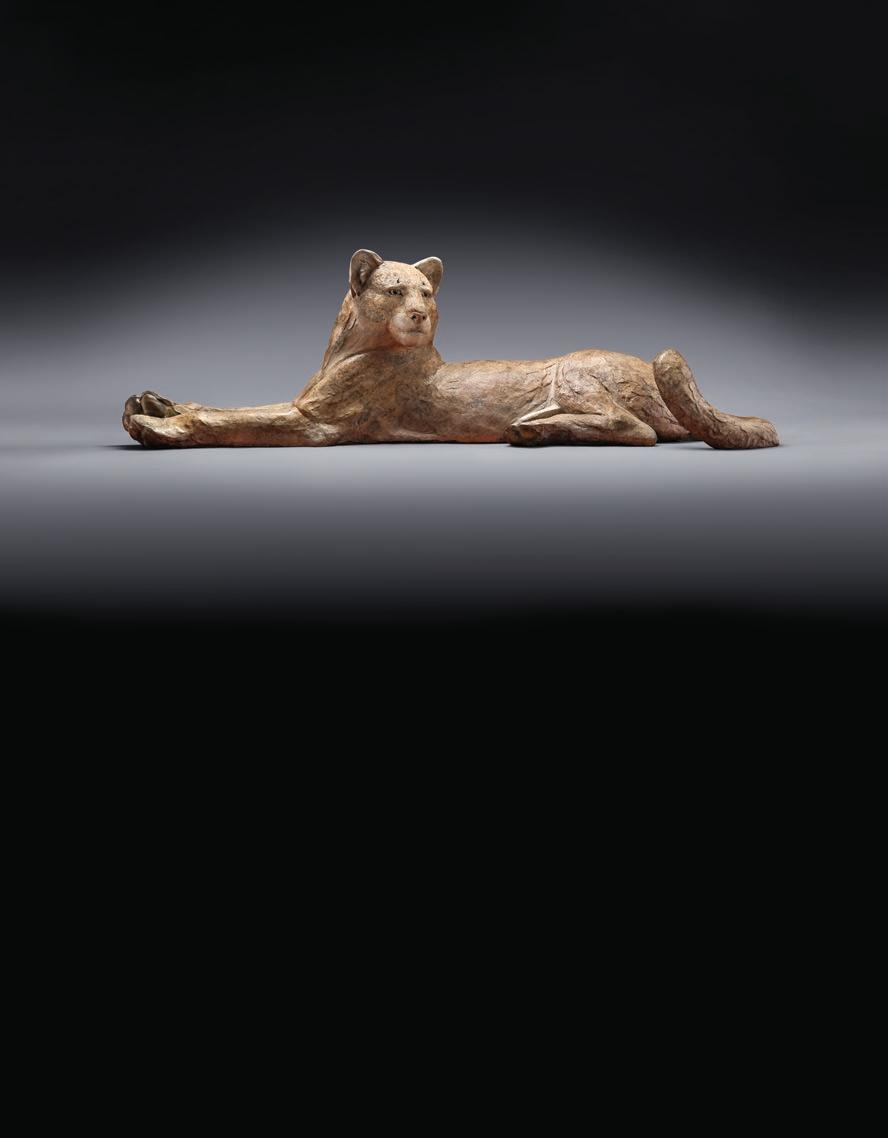

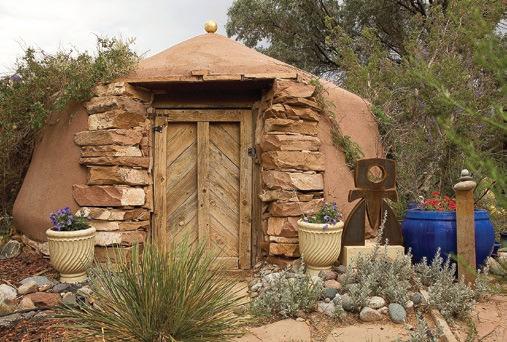

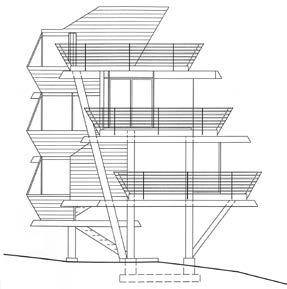

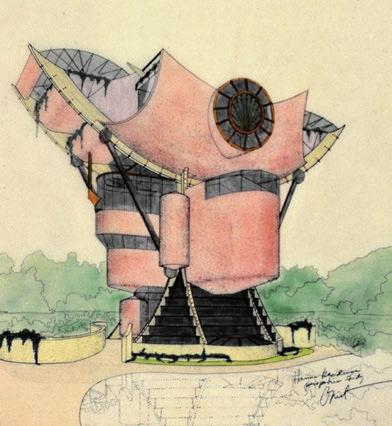

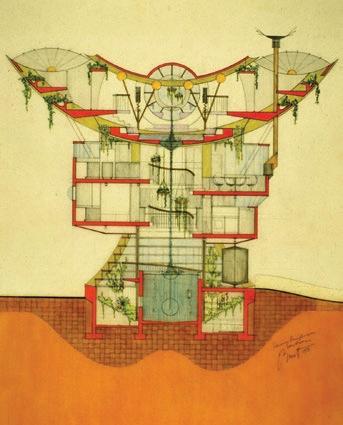

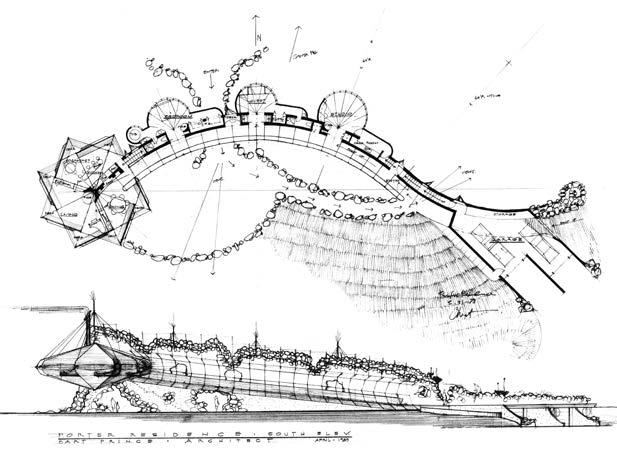

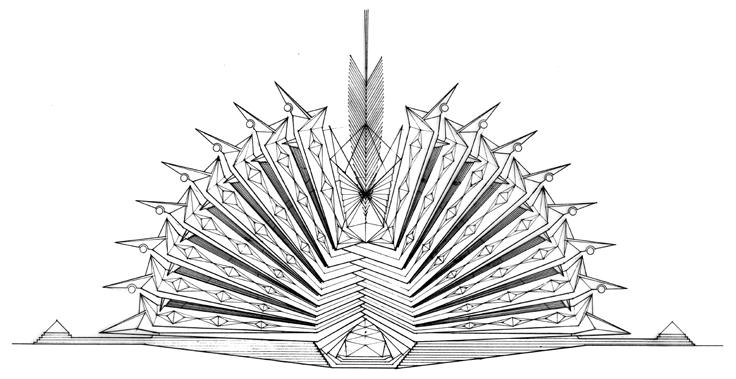

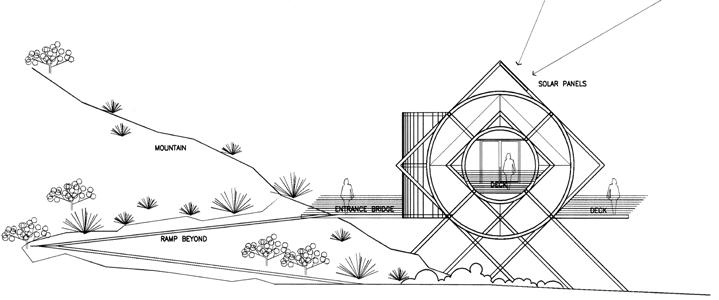

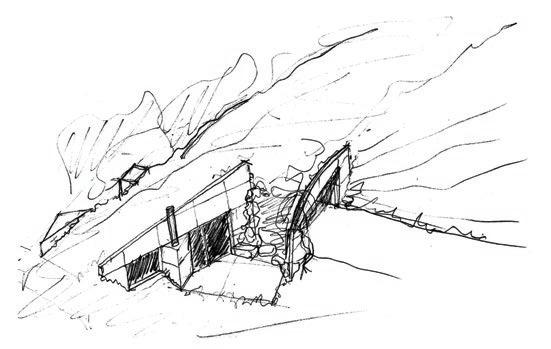

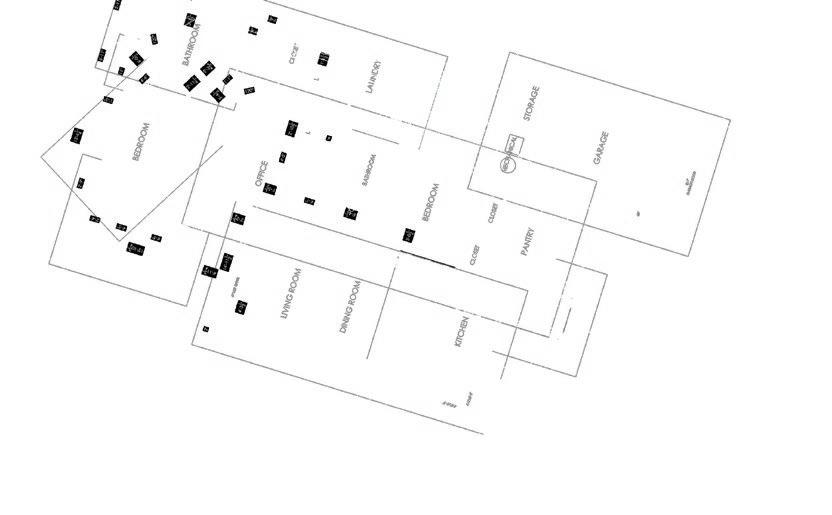

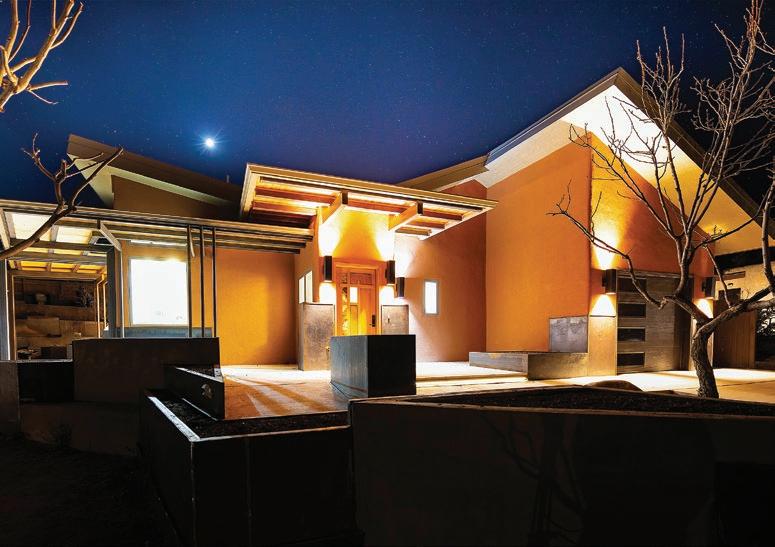

292 Radically Original

The art of Bart Prince’s architecture

B y e llen B eR kovitch | Photos By Ro B eR t Reck

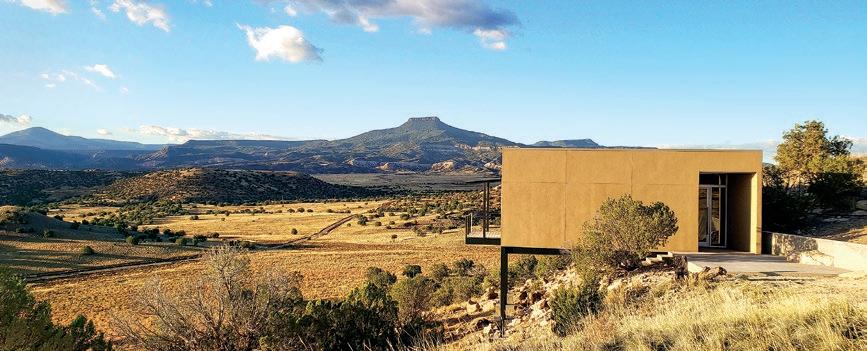

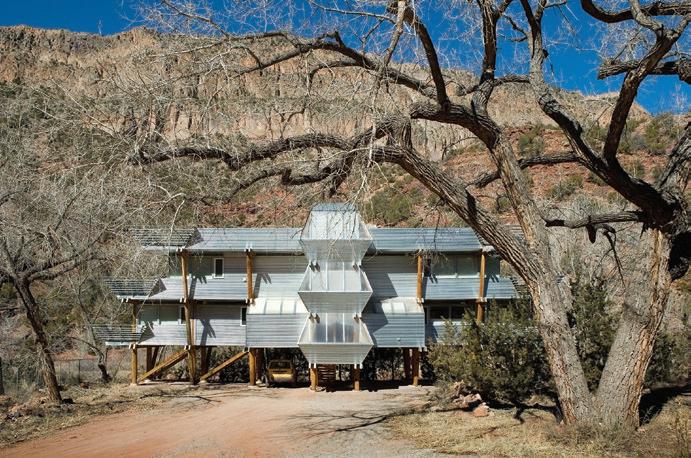

304 Changing the Vernacular

The late architect Jeff Harnar melded contemporary materials with an appreciation of the natural world

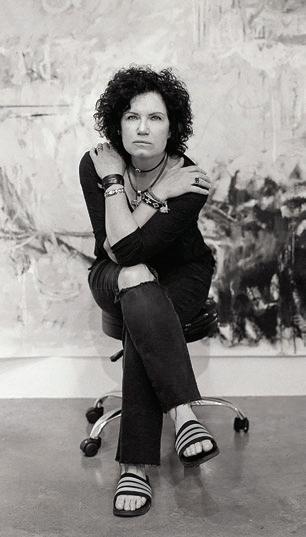

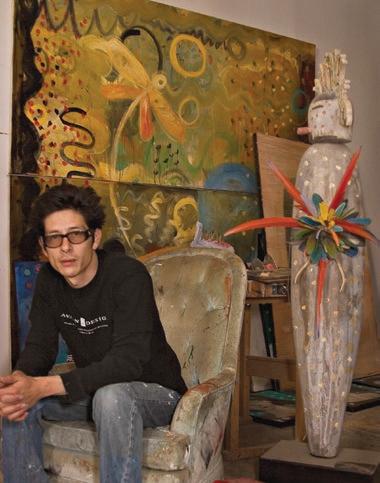

B y nancy zimmeRman | Photos By Ro B eR t Reck

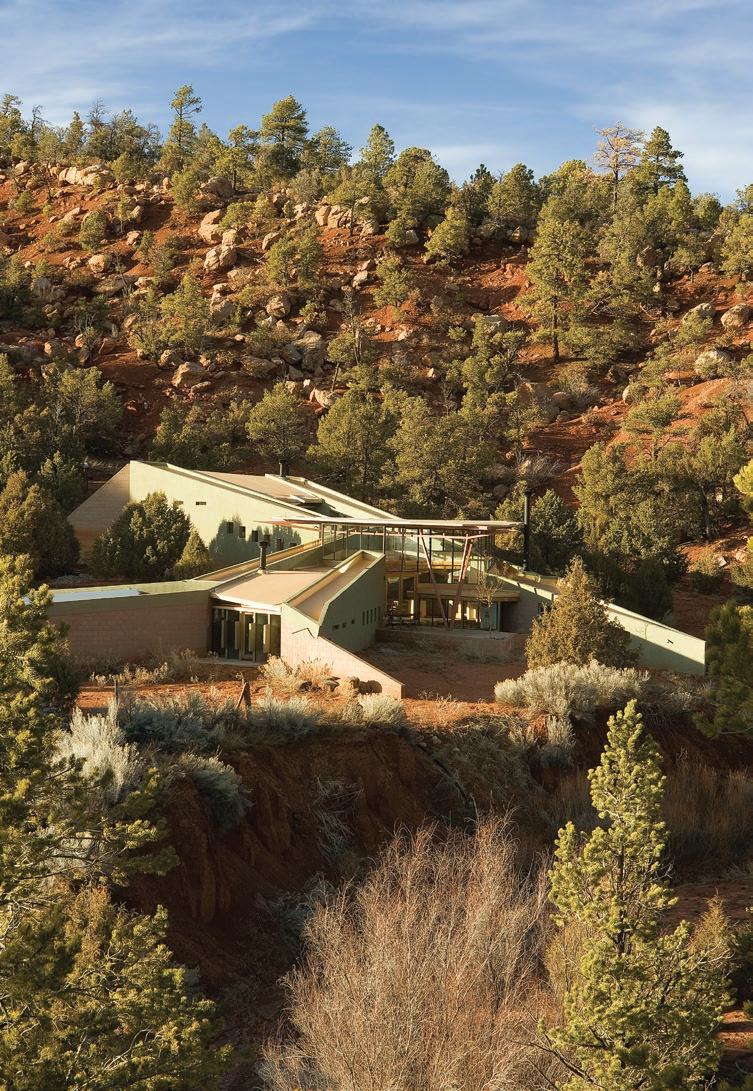

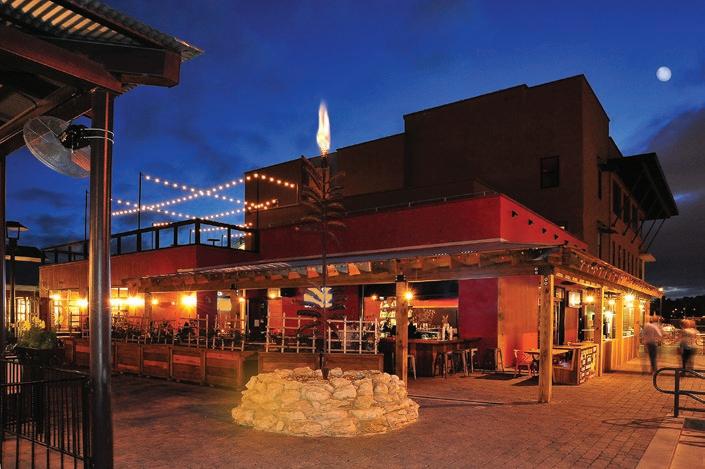

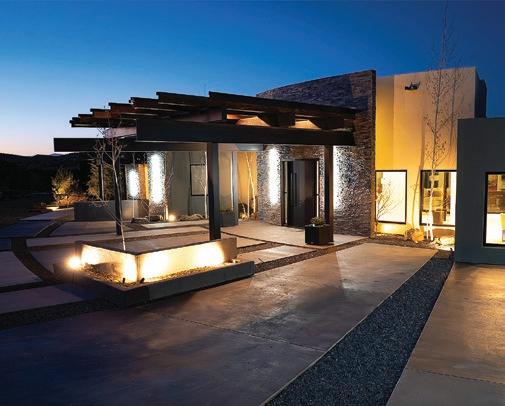

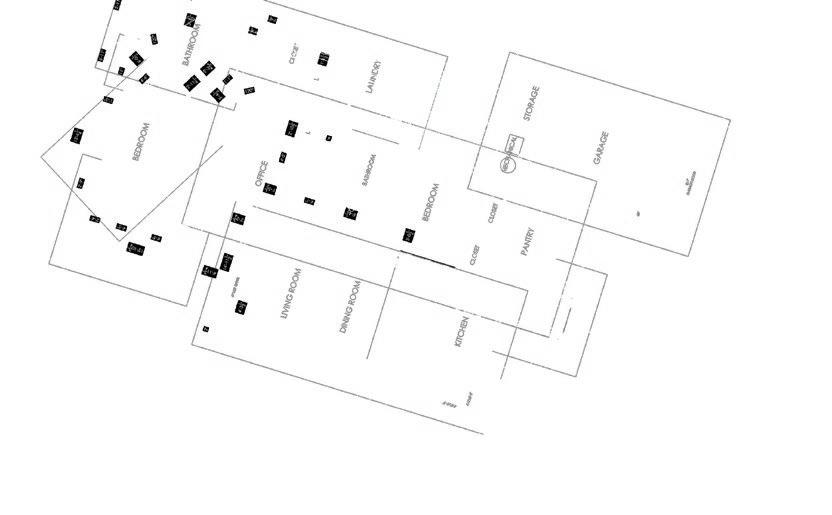

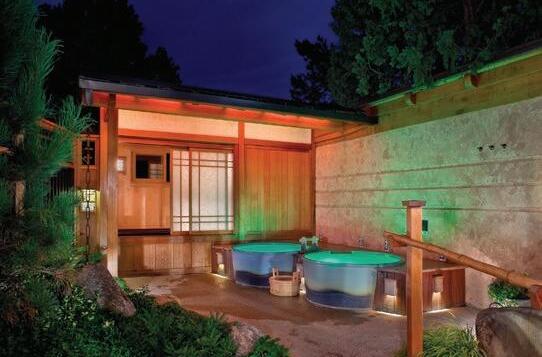

322 Staging Light

Architect Michael Krupnick designs “movie sets” for people’s lives that keep nature close

B y B ill Ro D geR s | Photos By k iR k gittings

330 Down to Earth

Classic New Mexico architecture meets the latest in sustainable technology in architect

Michael F. Bauer’s high-desert, passive-solar villa

B y stePhanie PeaR son | Photos By chas mc gR ath

ART MATTERS

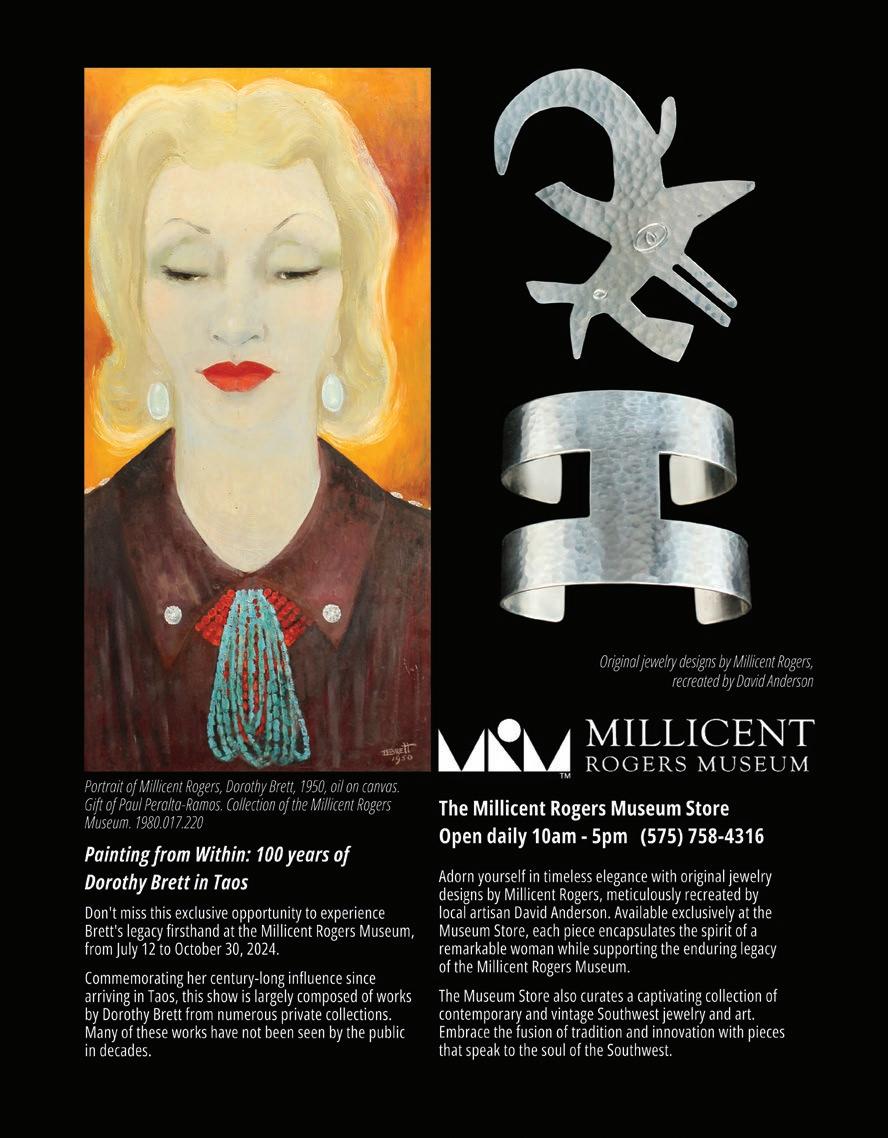

58 Cuffs Around the Edges

Two New Mexico jewelers amp up a traditional shape

B y heiD i e Rnst

68 Terry Allen: Theater of Art Master of multimedia, he invites all of our senses to the party

B y k athRyn m Davis | Photos By k ate R ussell

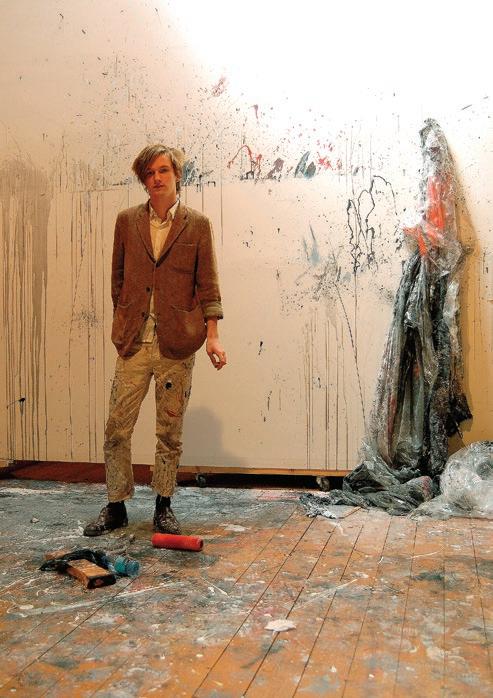

71 Crafting Worlds

A new Santa Fe art installation explores a fantastical family narrative

B y Jamie holt | Photos By k ate R ussell

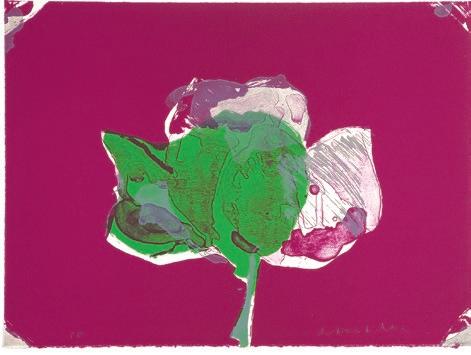

81 Alexander Girard

The Legacy of the Mid-Century Modern Maestro in New Mexico

sto Ry anD Photos By R achel PR inz

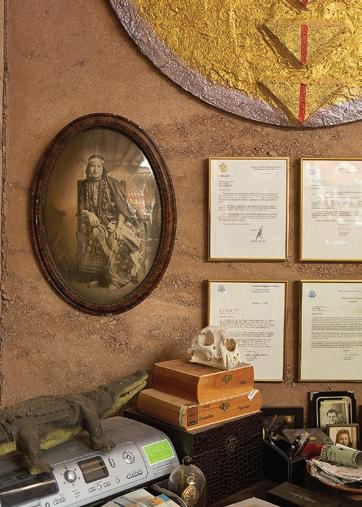

86 Calling on the Past

An artist lives and works in his great-grandfather’s studio

B y gussie fauntleR oy | Photos By k ate R ussell

102 The Artful Adventurer

Madeline Gehrig brings the world home

B y Rena D istasio | Photos By k ate R ussell

TAOS

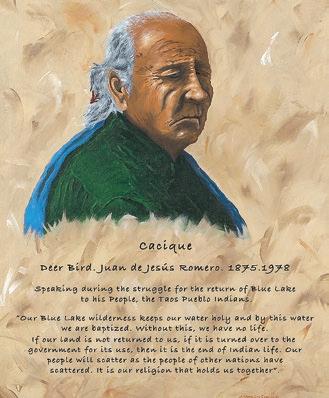

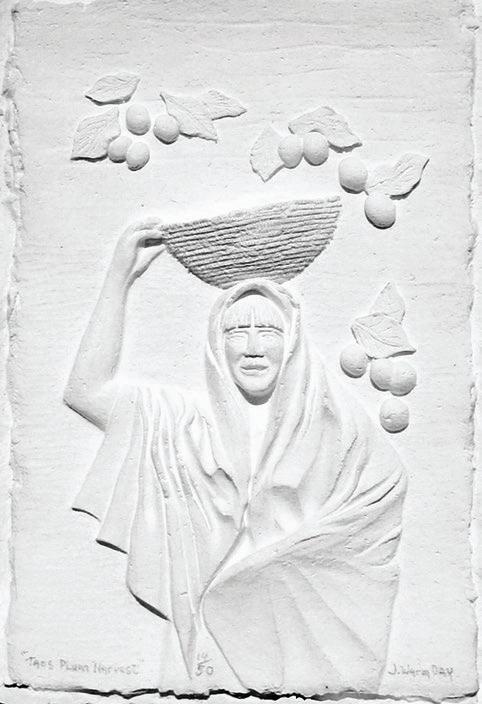

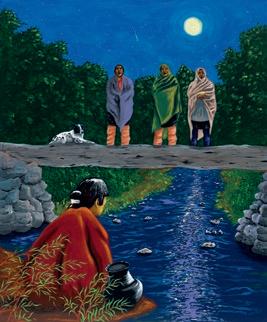

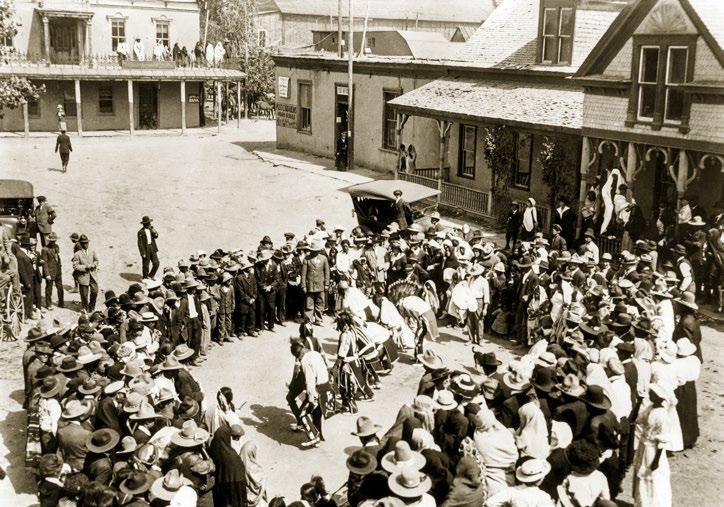

138 Water, Earth, Stone, Flesh

Currents of tradition flow through generations of Taos Pueblo artists

sto Ry anD Po R tR aits By Rick Romancito

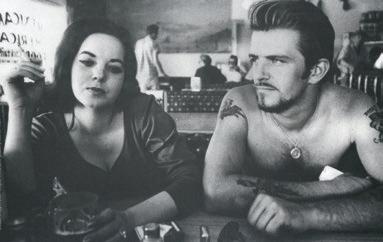

151 He’s a Walking Contradiction, Partly Truth and Partly Fiction Reflections and Reminiscences of Dennis Hopper in Taos

B y lyn B leileR

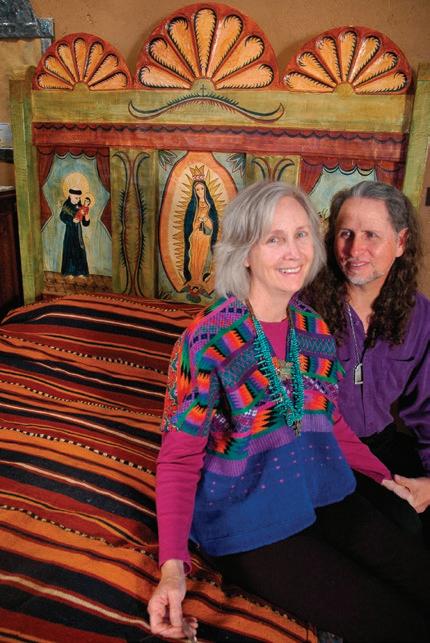

162 The Bearable Lightness of Being Light and reflection in the work of Larry Bell

B y lyn B leileR | Photos By k ate R ussell

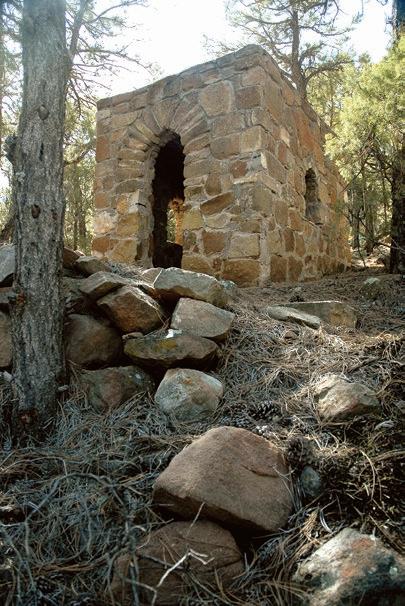

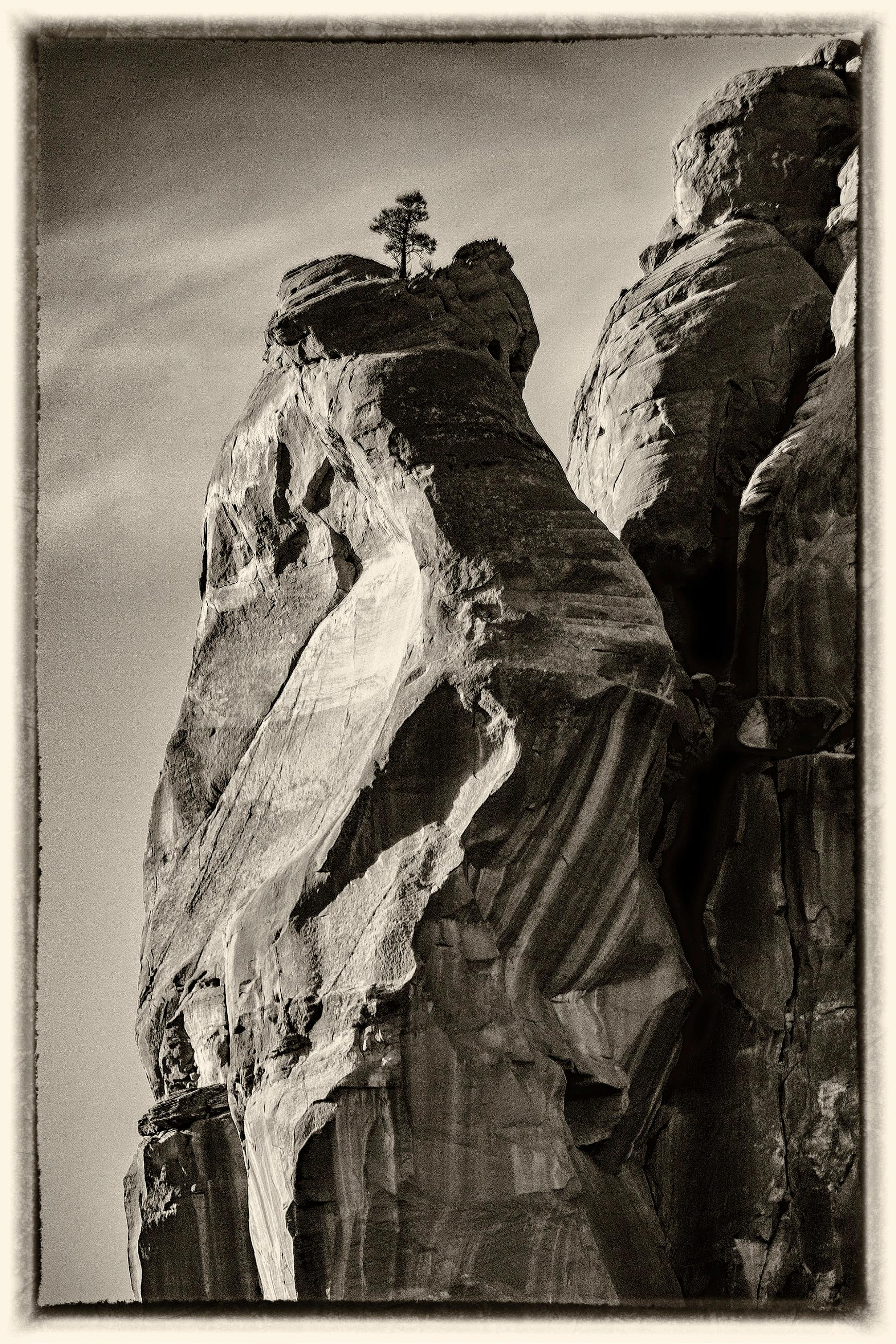

170 Abiquiu’s Luminous Stone

Excerpted from Valley of Shining Stone: The Story of Abiquiu

B y lesley Poling - k emPes

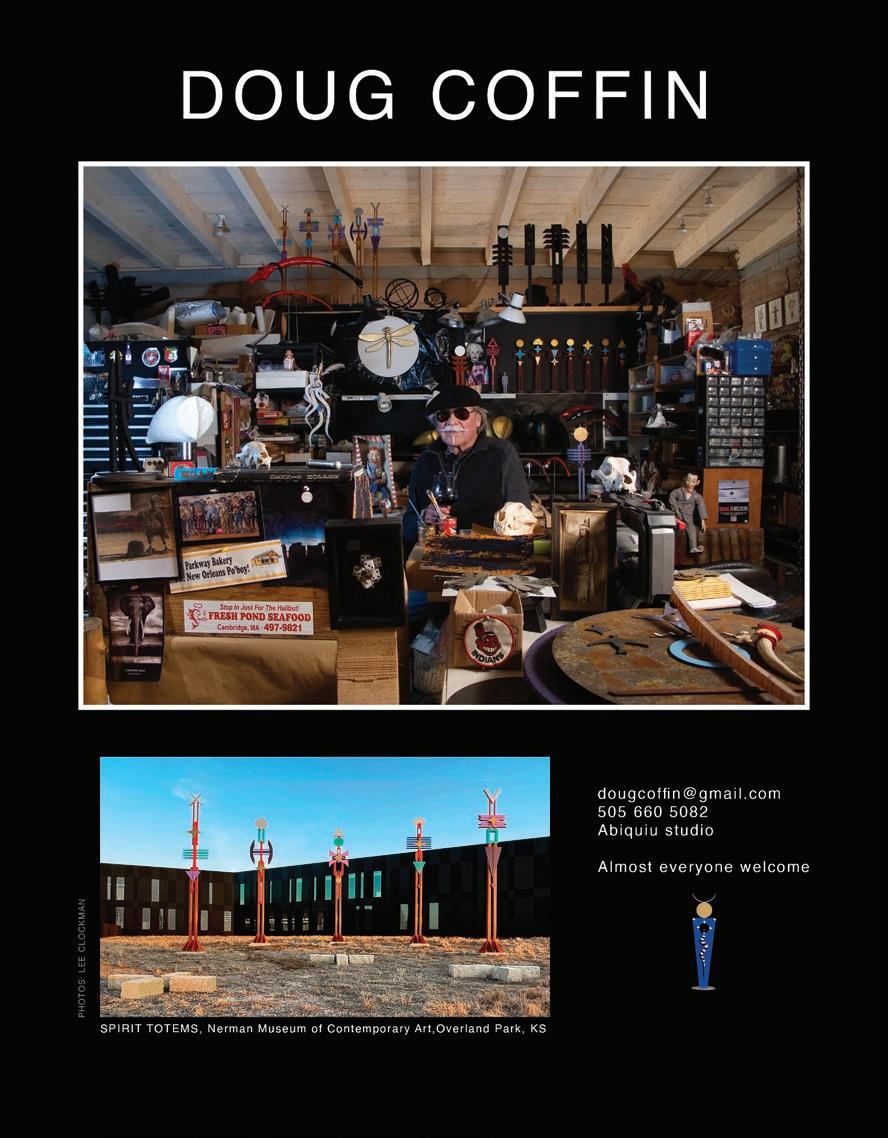

186 House on a Hill

Doug Coffin and Kaaren Ochoa’s Abiquiu inspiration

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By k ate R ussell

DESIGN SOURCE

287 Inspired Partnerships Inform Santa Fe’s Built Environment

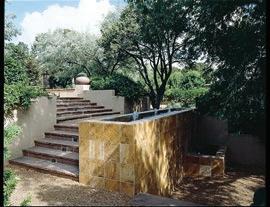

348 Edgy Landscapes

Edith Katz enacts divisions and fusions between gardens and the prairie

B y e llen B eR kovitch | Photos By k ent B oWseR

354 New Mexico’s Largest and Most Diverse City Embodies the Spirit of the Modern American West.

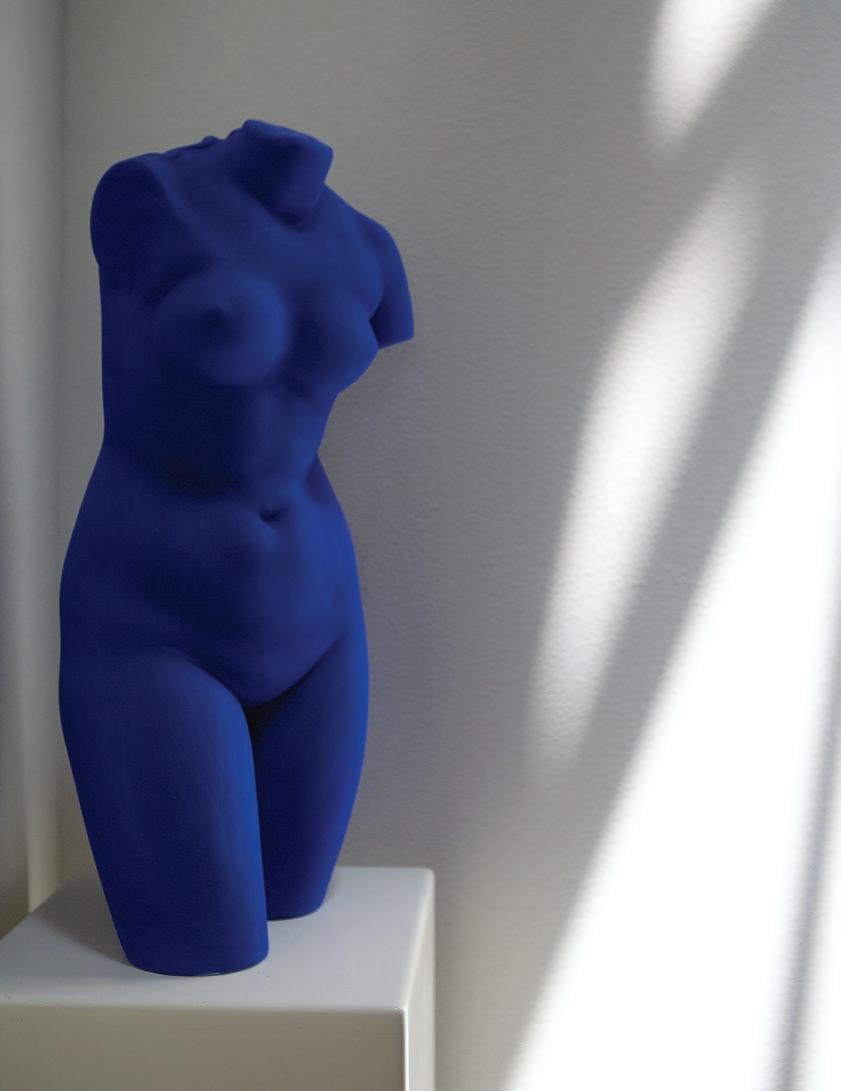

356 Body and Spirit

Drawing from myth, memory, and ancient history, Kristin Diener crafts intricate sculptural adornments that are part jewelry, part talisman

B y Rena D istasio | Photos By k ate R ussell

360 The Art of Survival

A unique Albuquerque initiative addresses homelessness through pencils, paint, and purpose

B y heiD i utz | Photos By k ate R ussell

MASTER ARTISANS

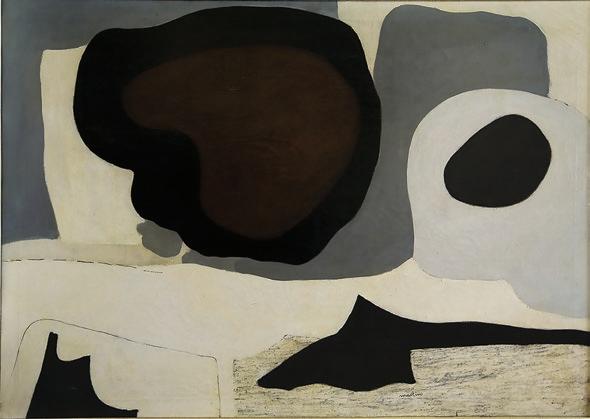

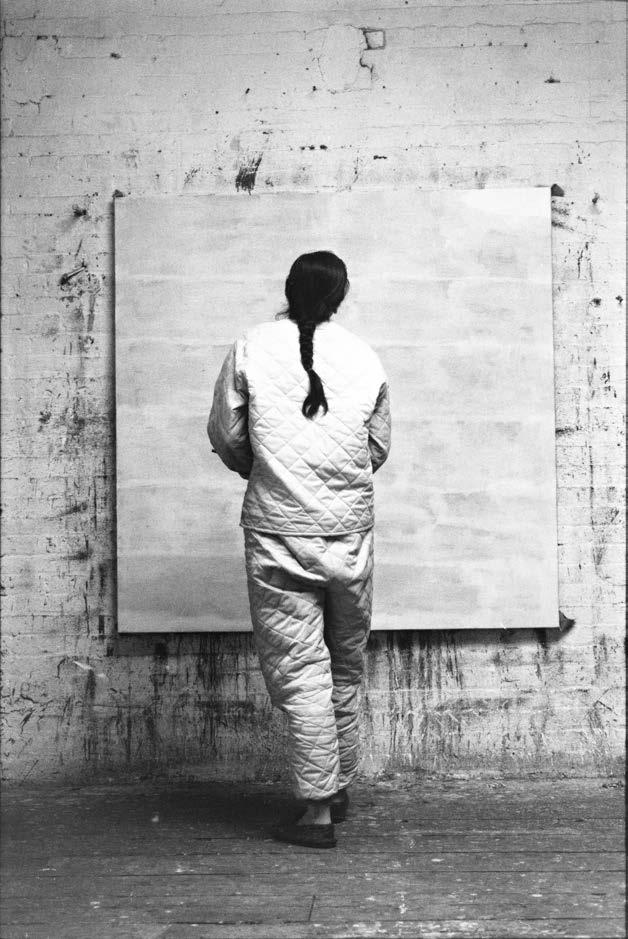

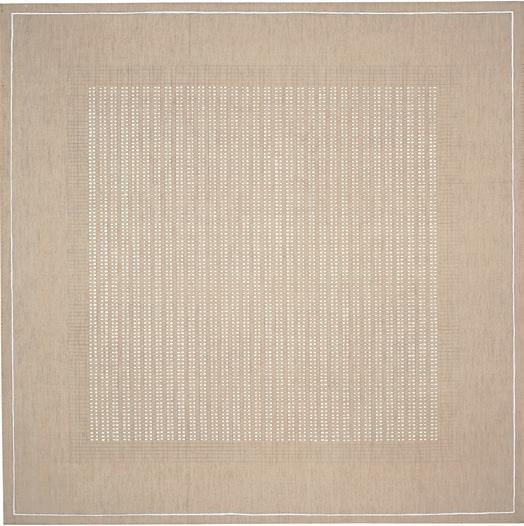

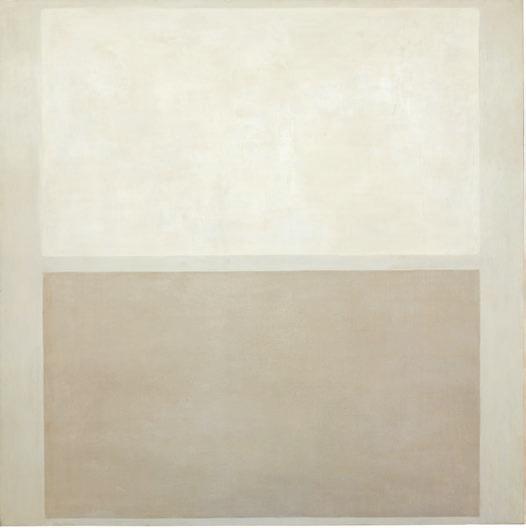

368 Igniting Debate

Agnes Martin: Before the Grid unveiled Abstract Expressionist icon’s early work

B y Jan e Rnst a D lmann

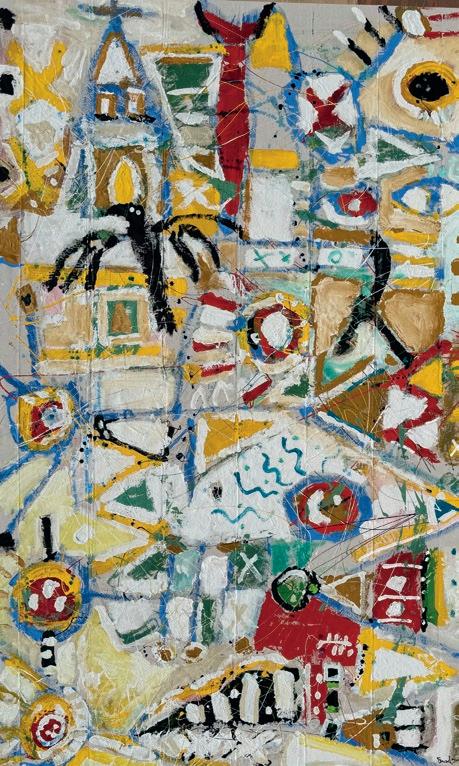

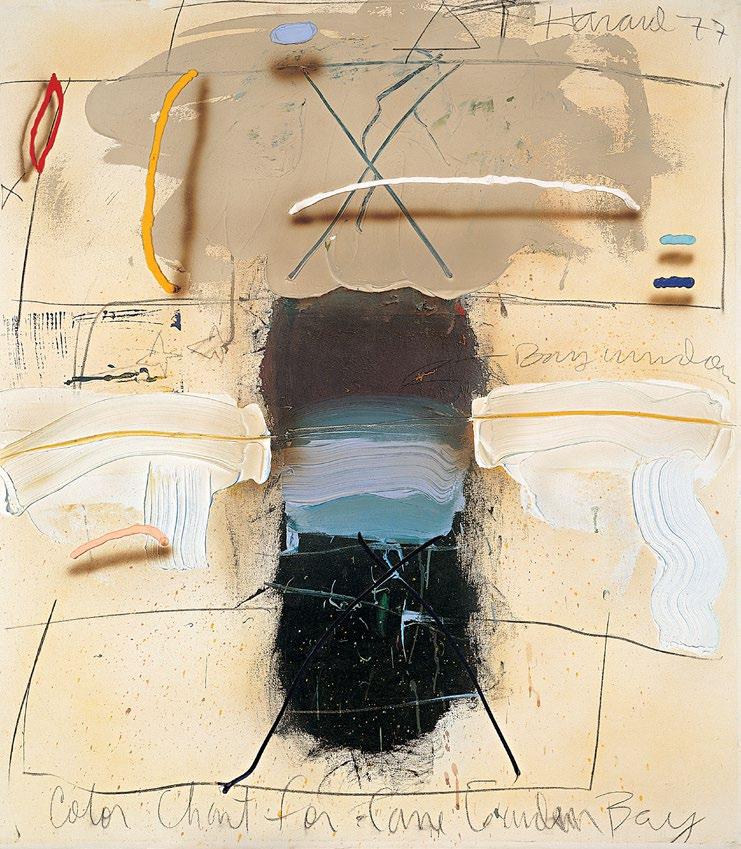

372 Paint, Refined and Raw

The mastery of James Havard

B y l auR a a DD ison

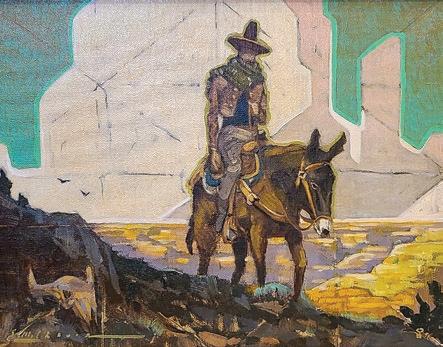

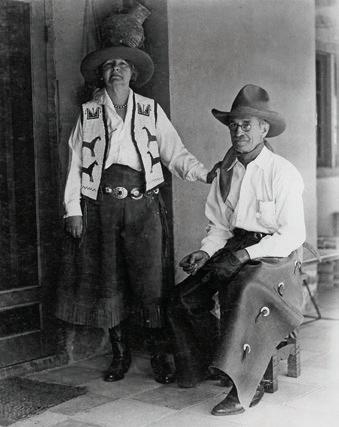

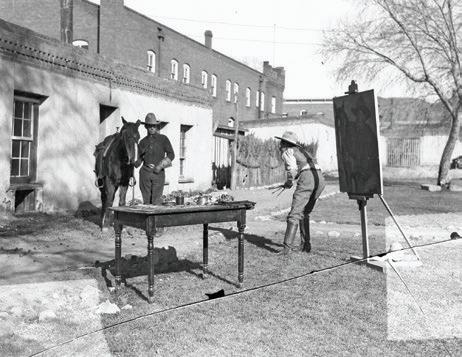

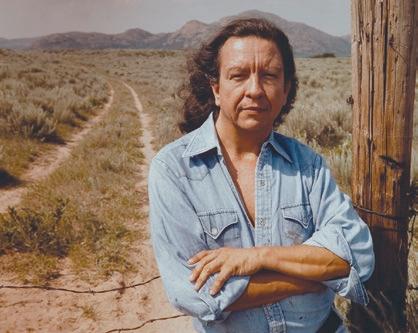

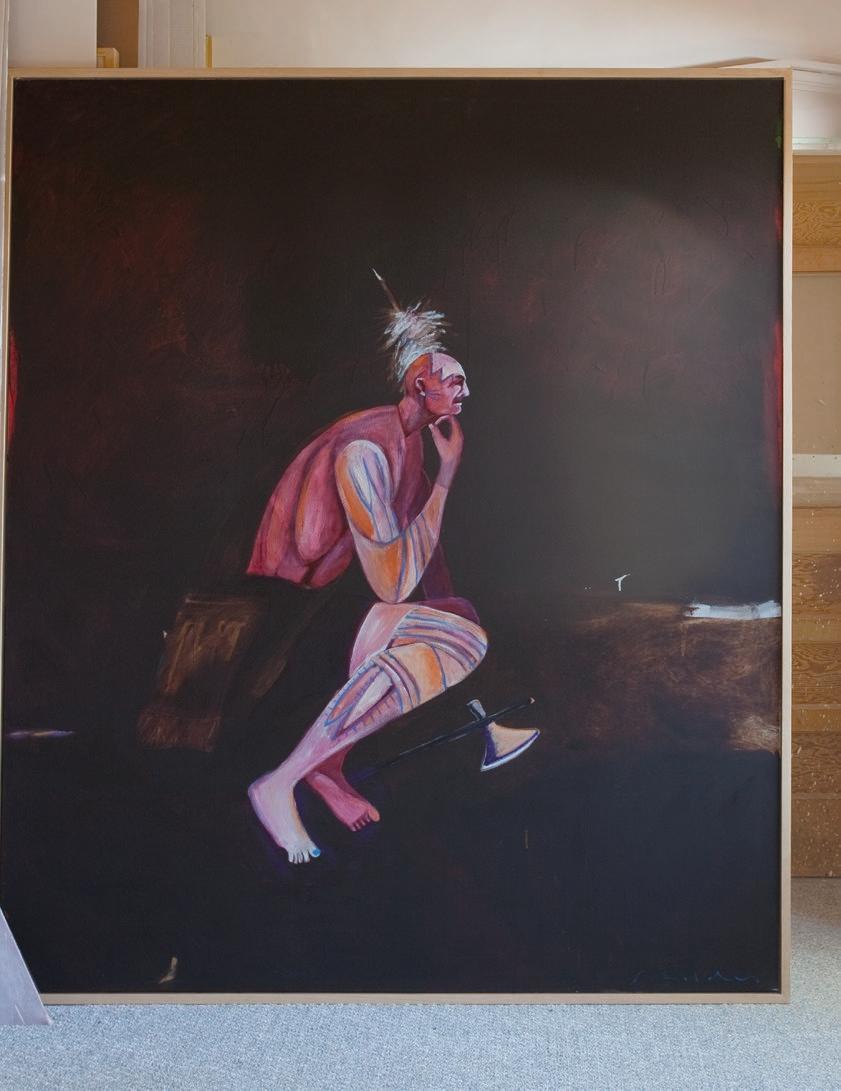

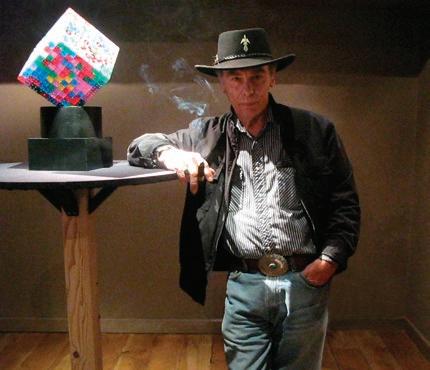

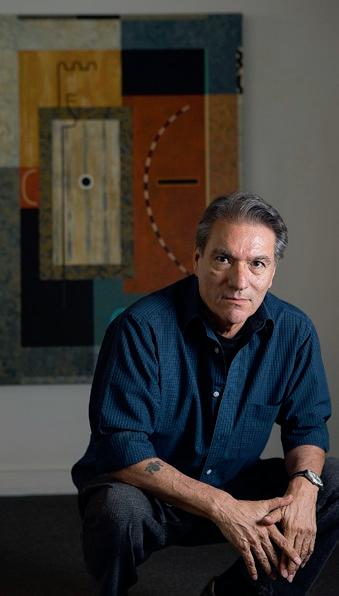

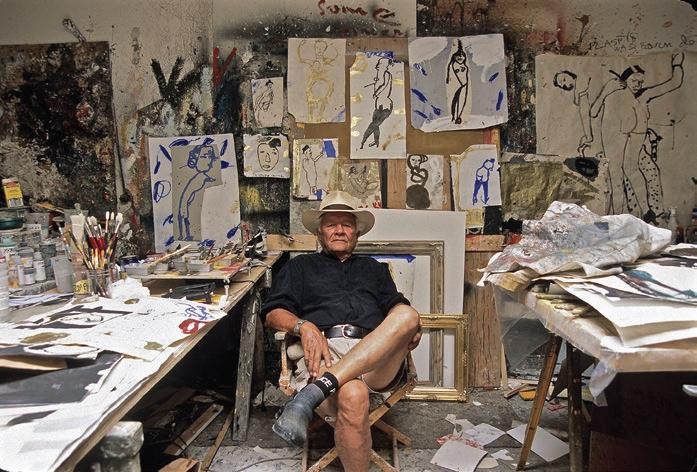

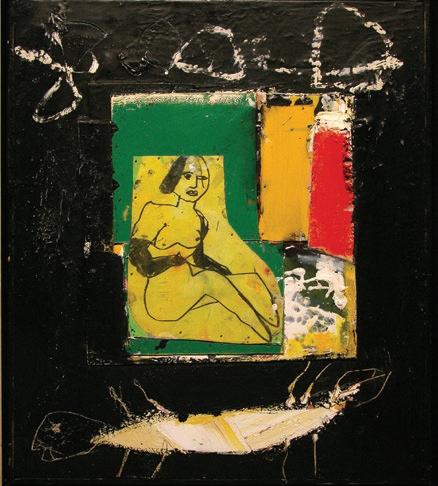

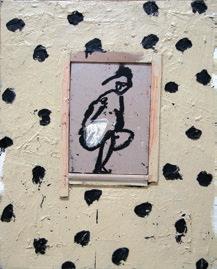

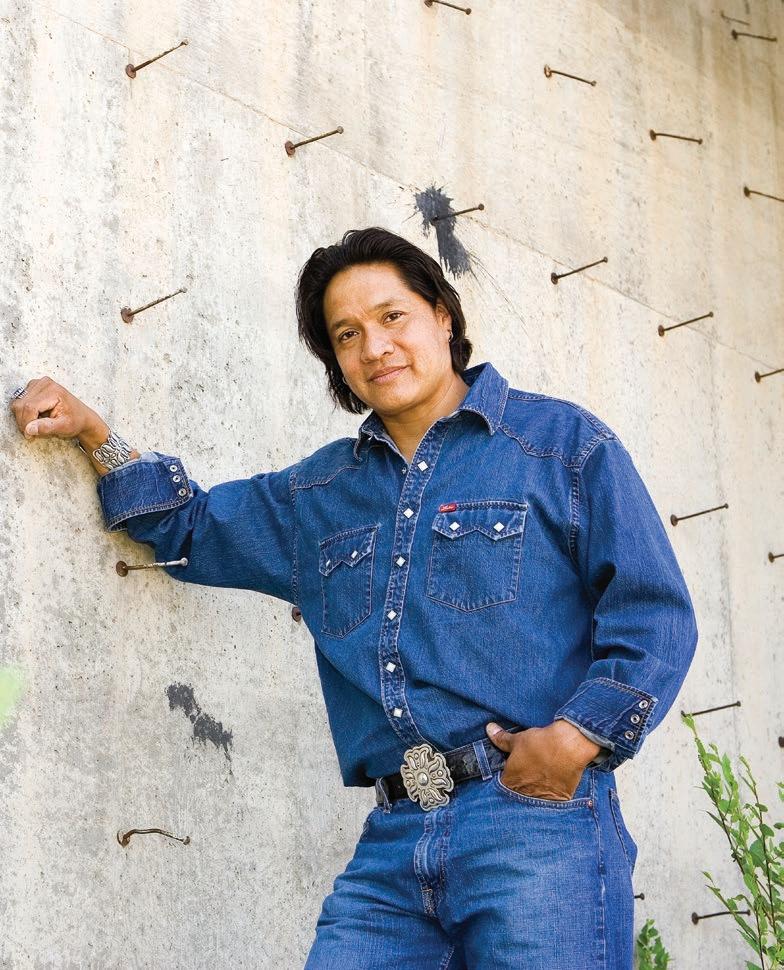

112 Fritz Scholder in Galisteo

People remember the celebrity and the parties. But Santa Fe’s most controversial Native artist had another side

B y k eiko o hnuma | Photos By PeteR o gilvie

134 At Home with His Destiny

Santero Ramón López’s art and home are works in progress

B y teR esa z amo R a | Photos By JennifeR e sPeR anza

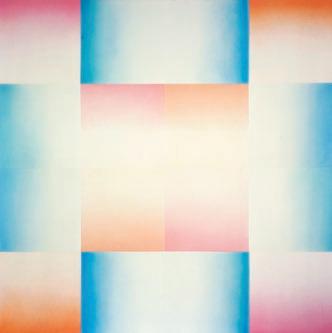

378 Minimalist Master

The Zen-like artistry of Florence Pierce

B y sunamita lim | Po R tR ait By D ouglas k ent hall

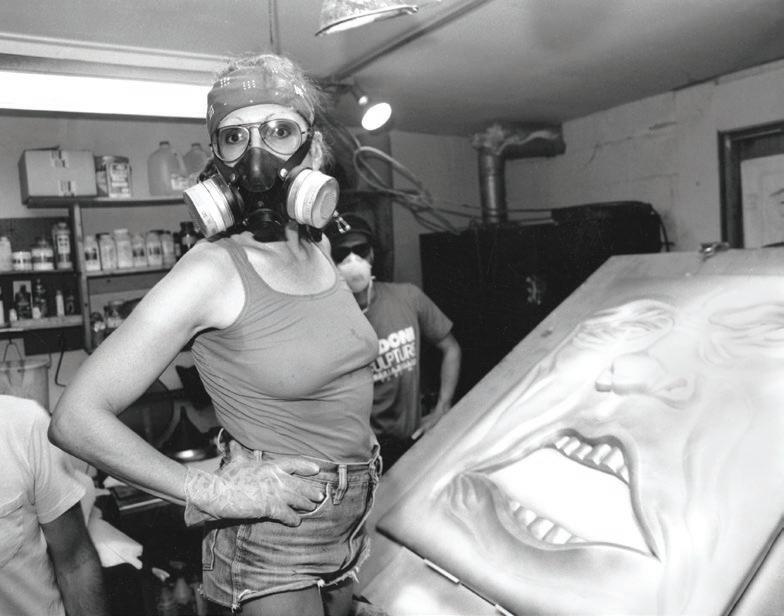

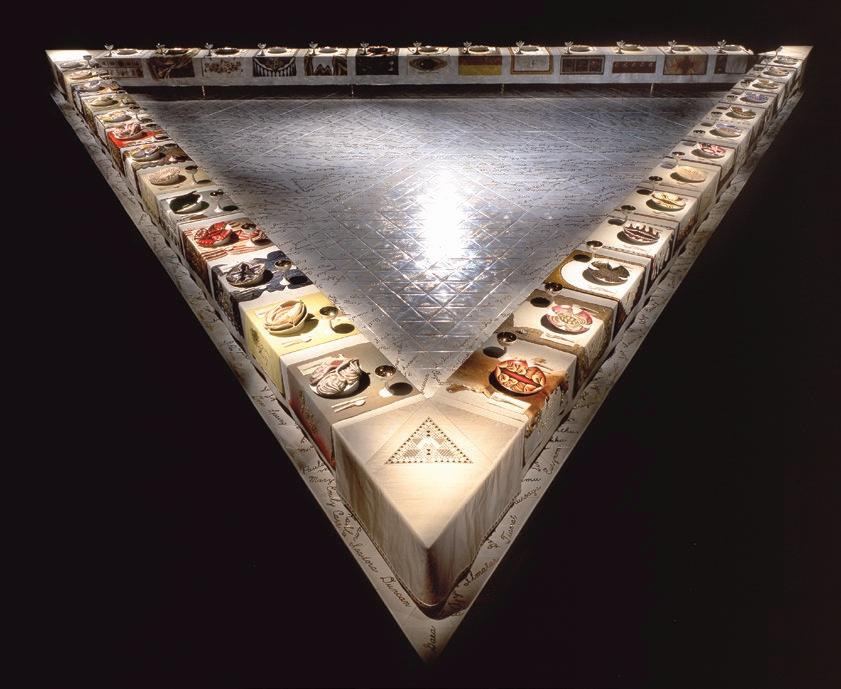

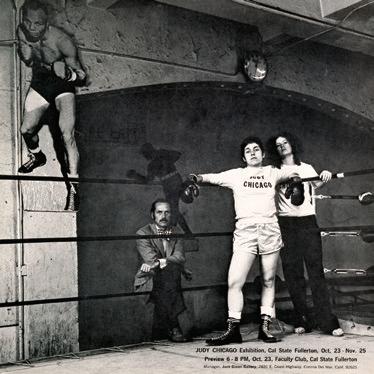

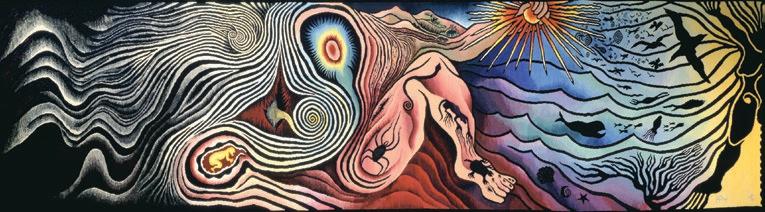

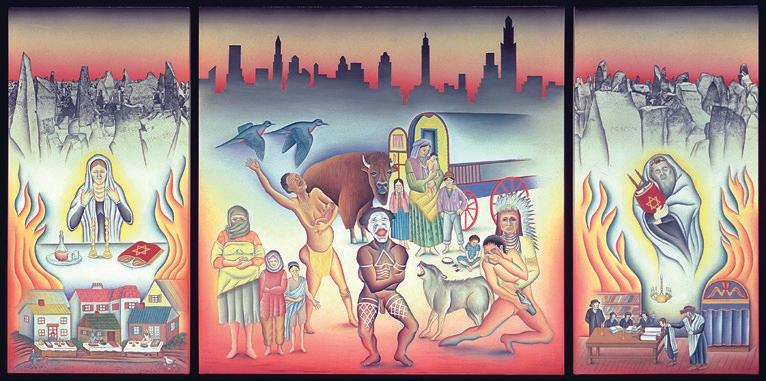

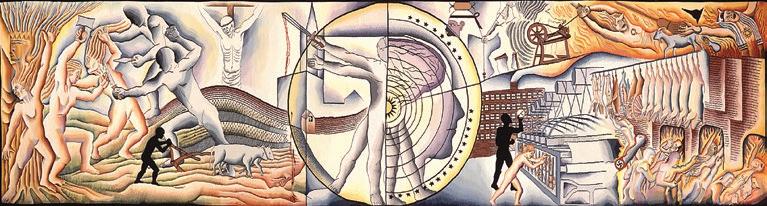

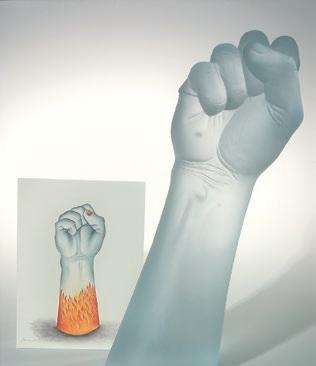

380 Chicago Rules

Judy Chicago devotes her life to shattering assumptions and stereotypes

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By D onalD Woo D man

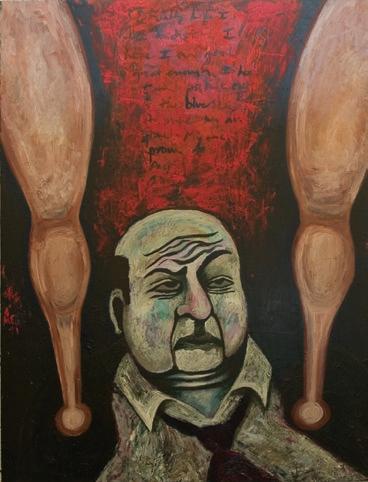

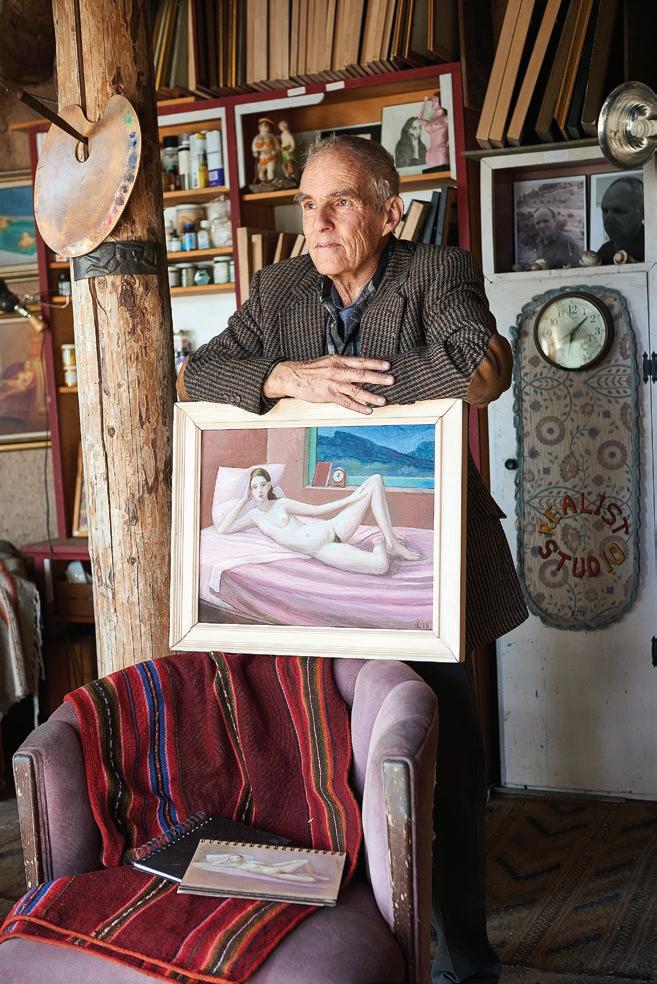

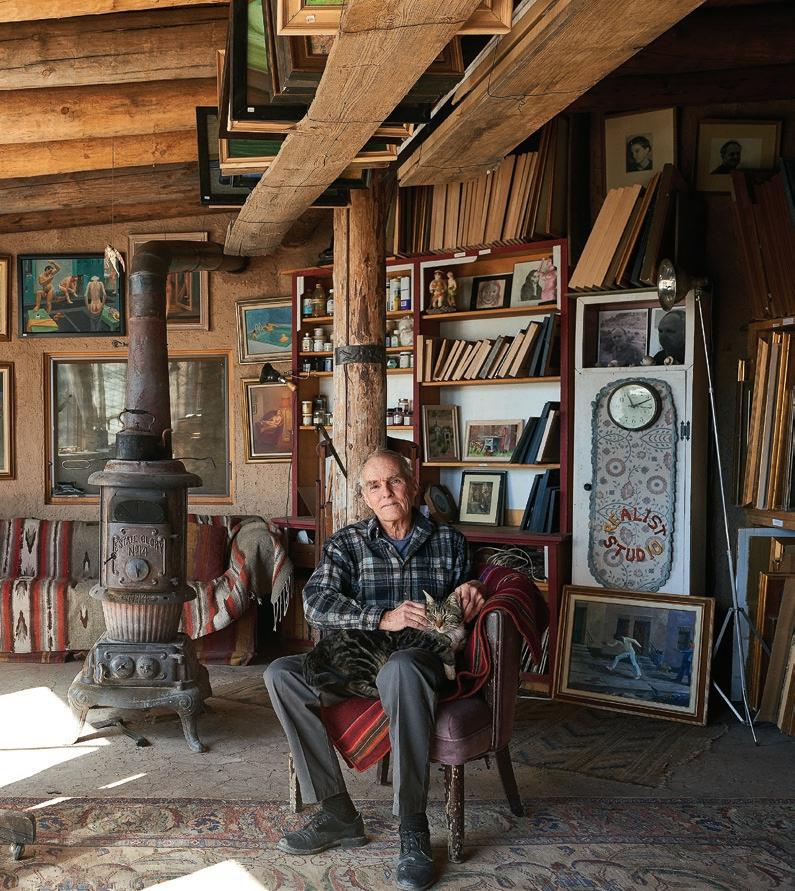

386 The Purist

Eli Levin eschews technology and trends in works that speak directly to the viewer

B y a nya seB astian | Photos By Dominique voRillon

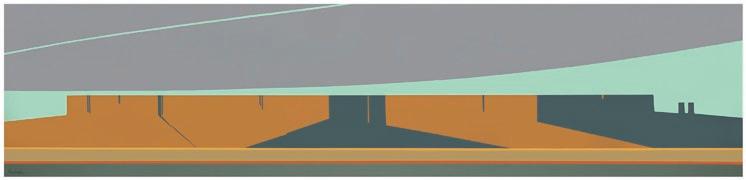

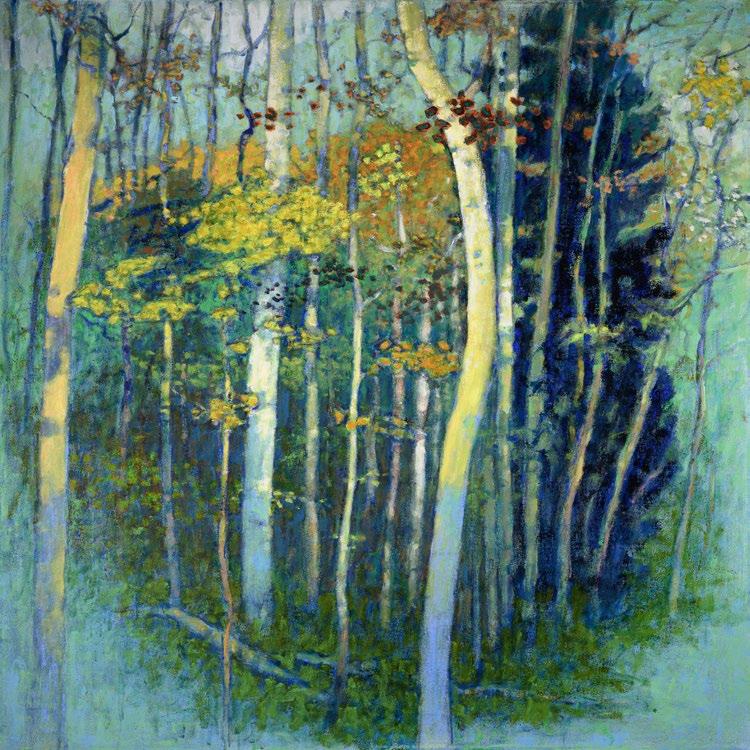

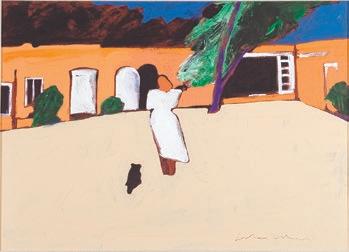

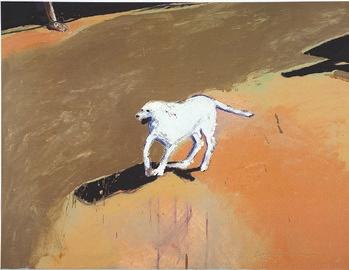

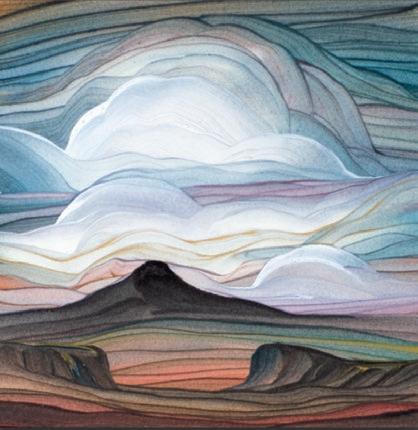

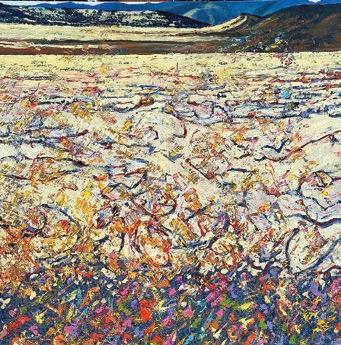

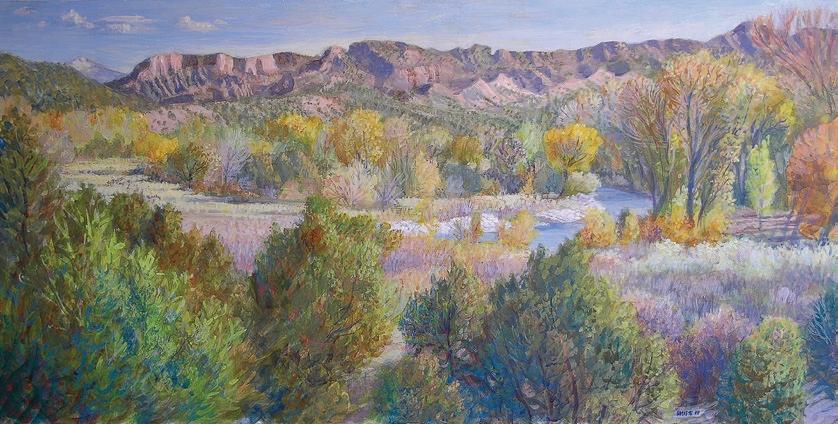

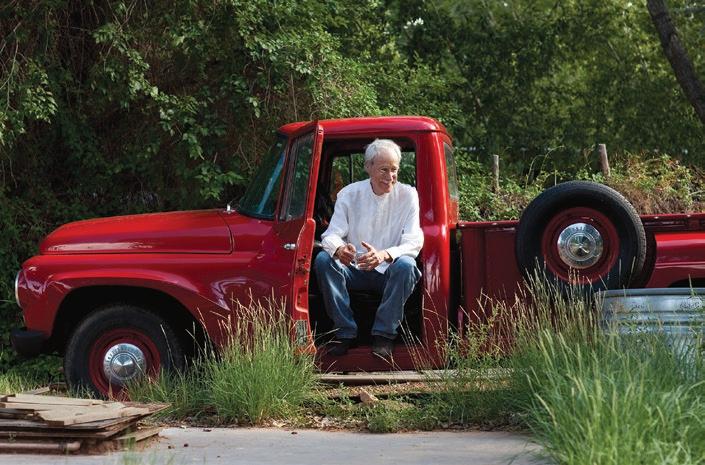

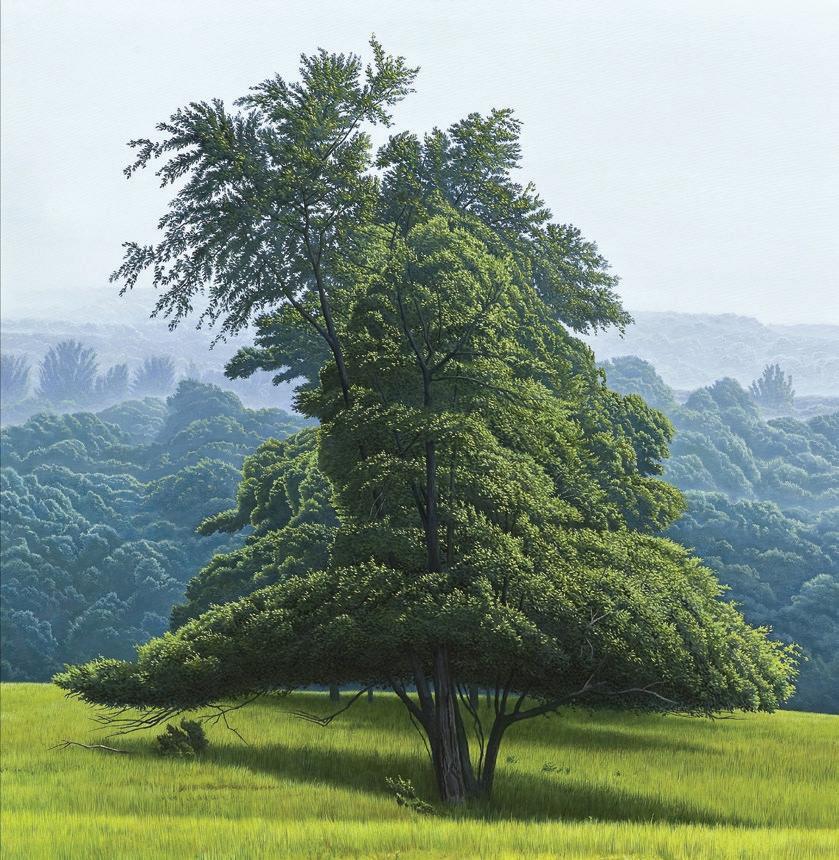

392 Precisely, Woody Gwyn

The master of plein-air realism finds truth in what is

B y e liza Wells smith | Photos By k ate R ussell

398 A Slow Unfolding of Landscape Emmi Whitehorse and her symbolic connection to the natural world

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By k ate R ussell

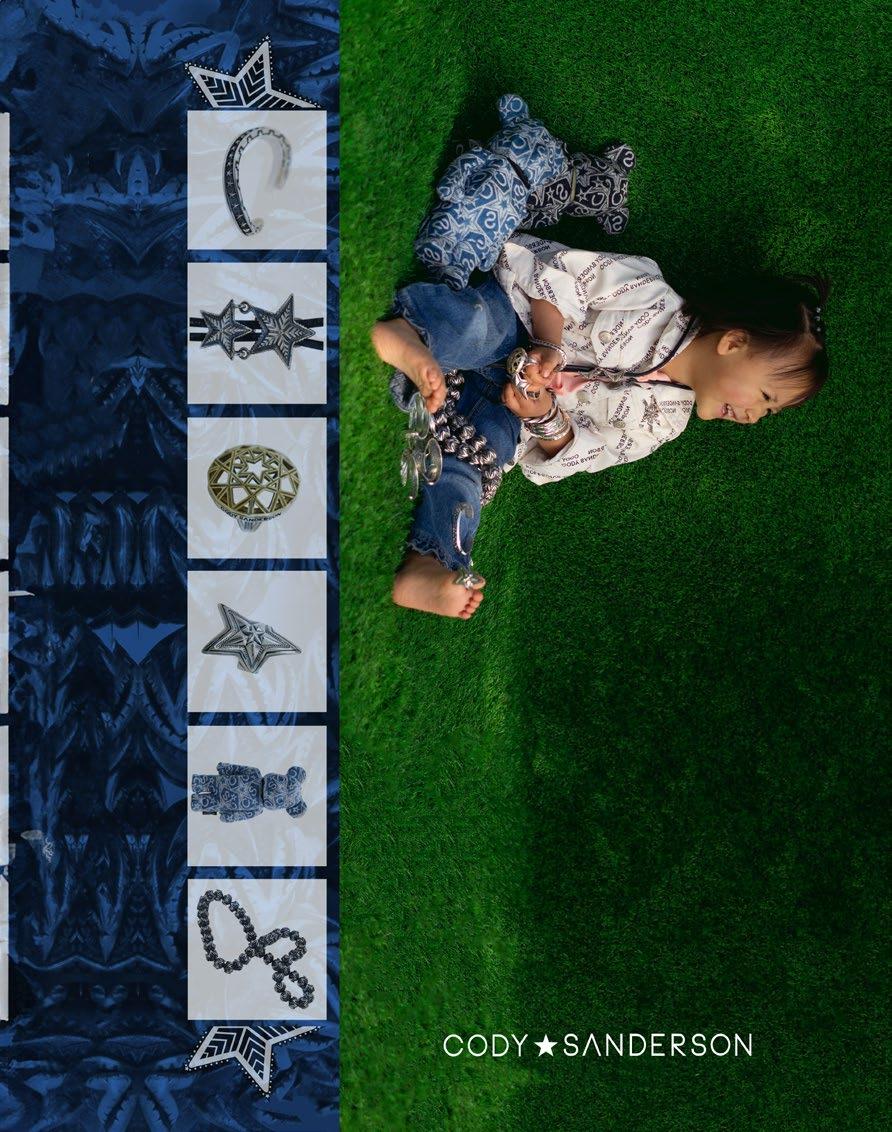

402 Stars and Spikes Forever

Cody Sanderson’s new jewelry anthem

B y gussie fauntleR oy | Photos By saR a stathas

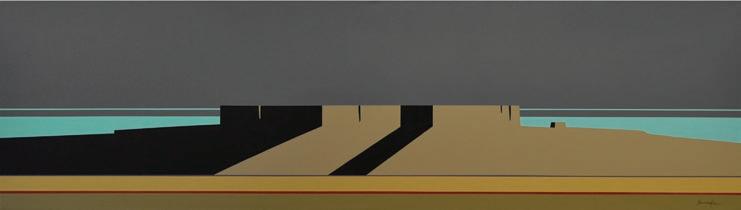

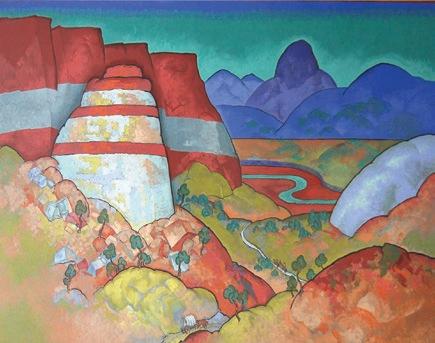

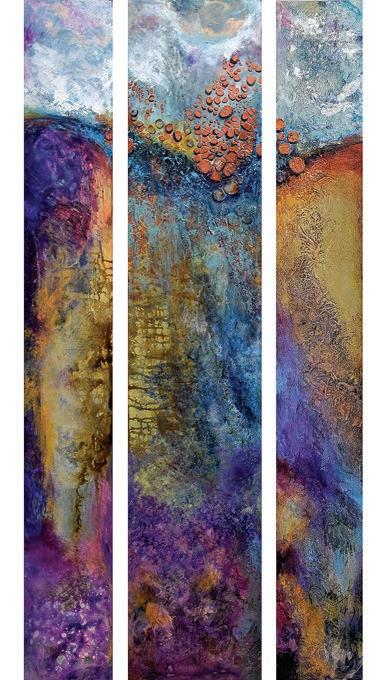

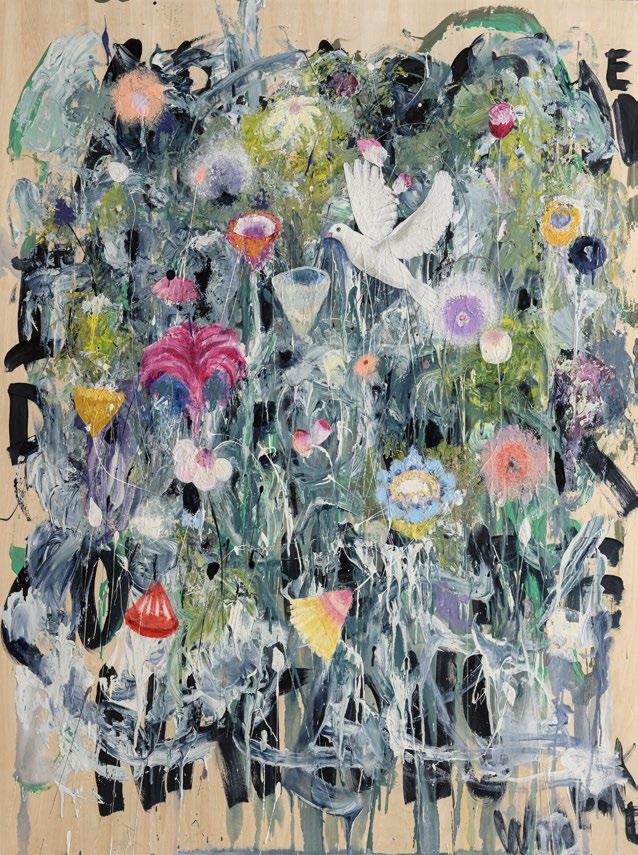

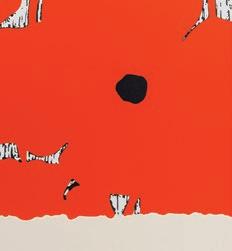

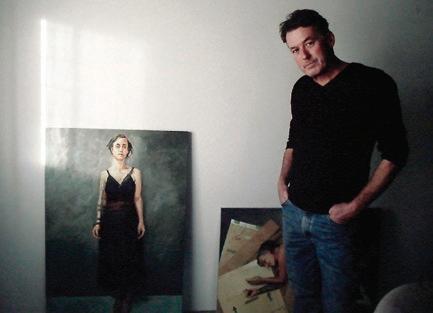

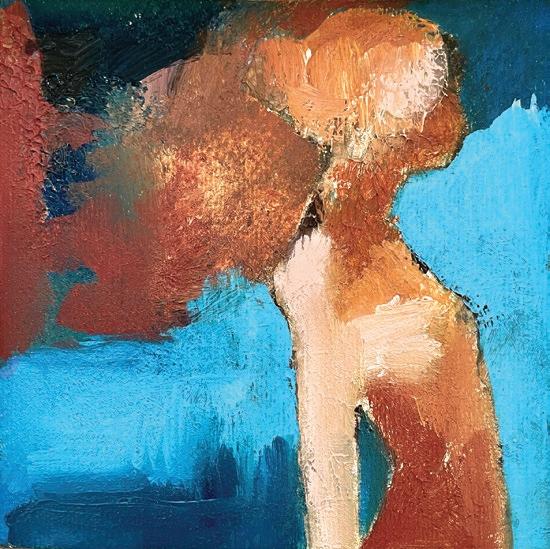

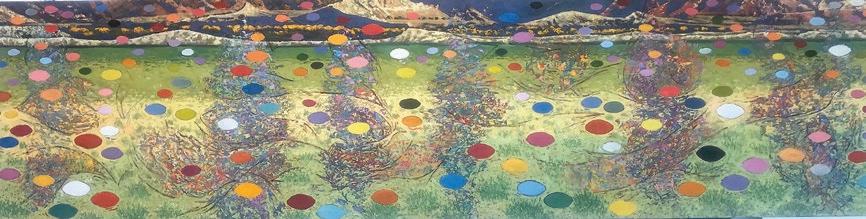

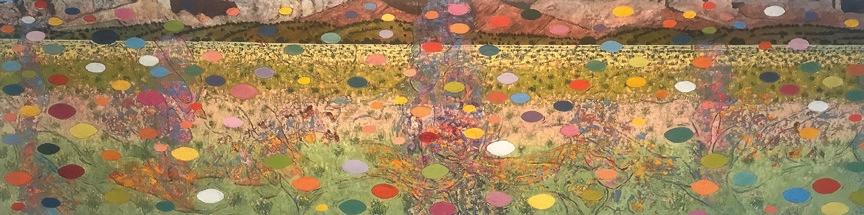

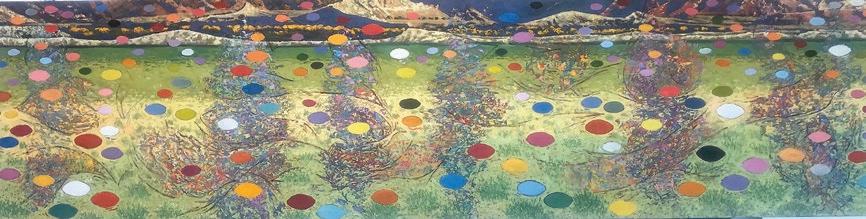

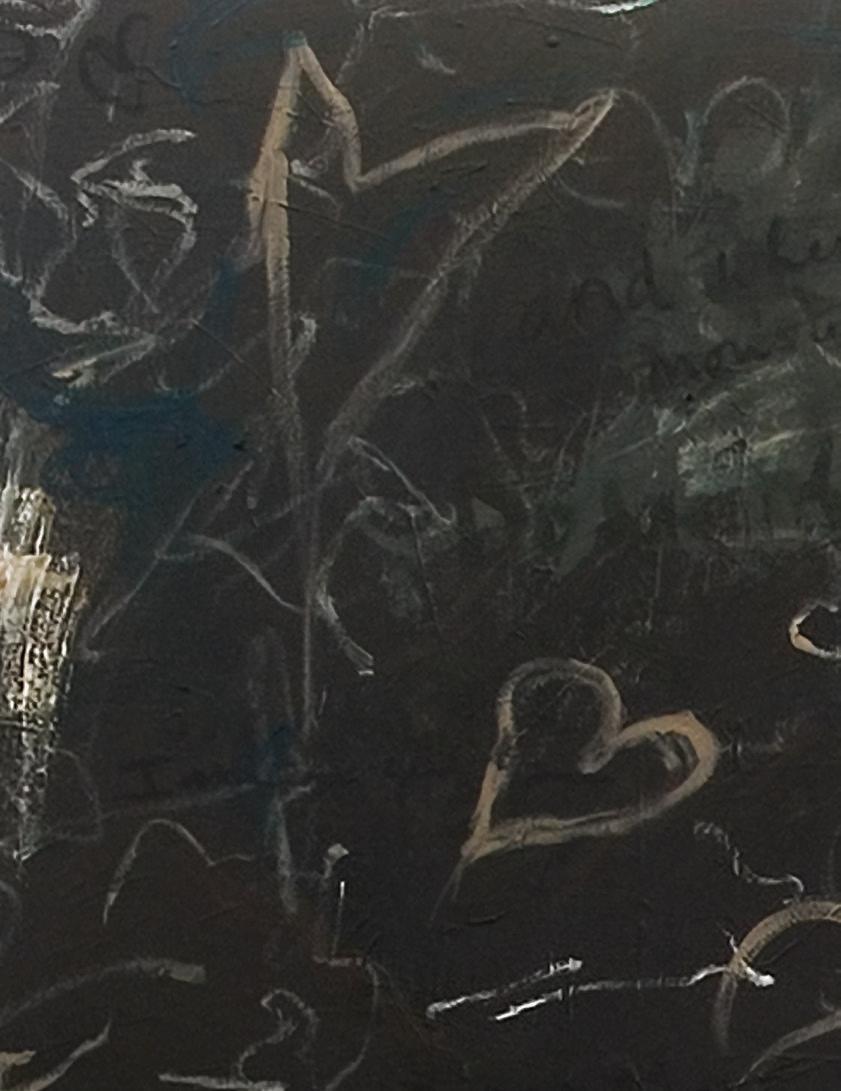

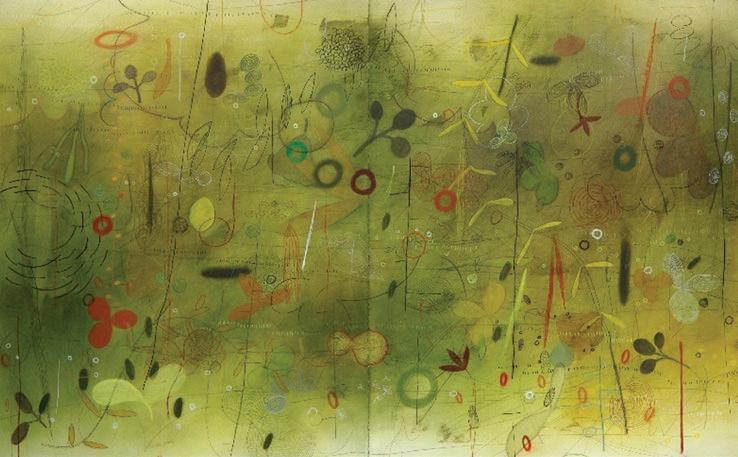

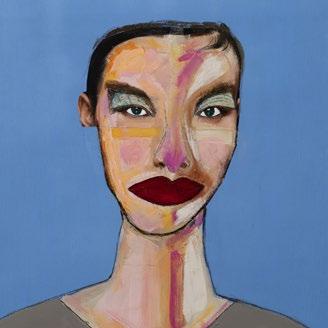

406 Abstract Emotionalism

The idiosyncratic visual language of Carlos Carulo

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By k ate R ussell

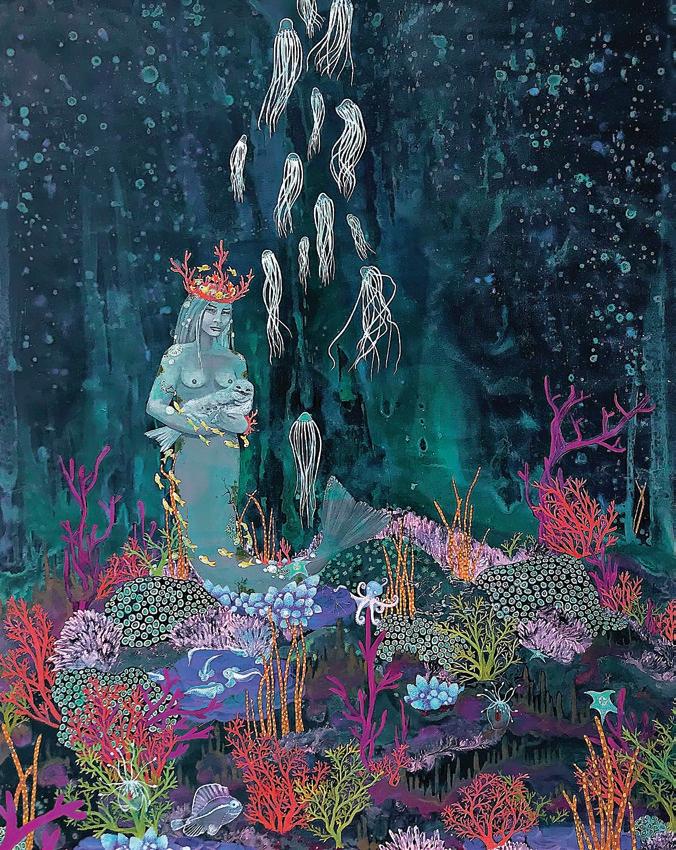

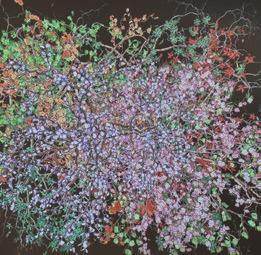

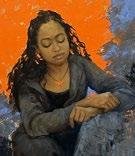

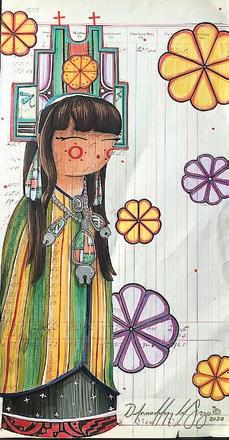

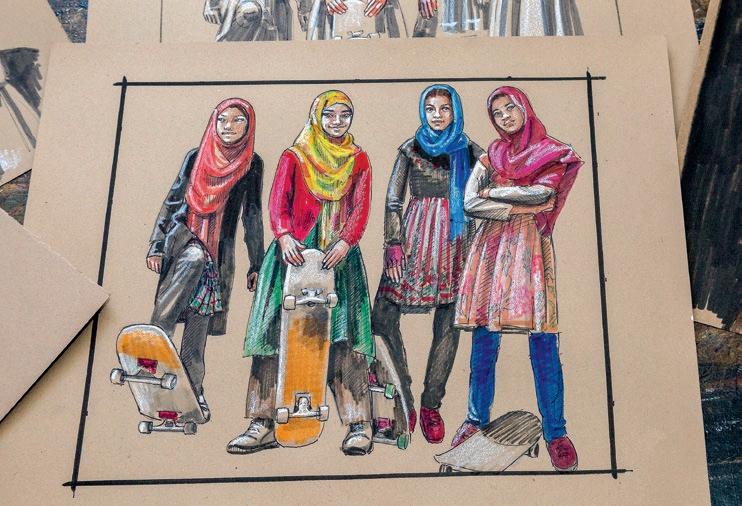

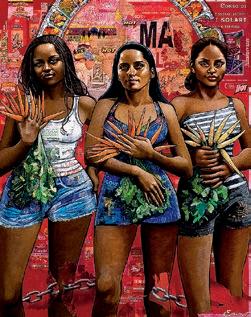

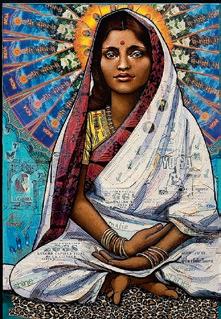

408 Art that Heals

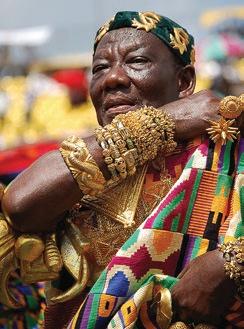

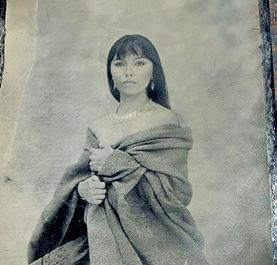

Erin Currier’s portraits convey the dignity, power, and heroism of the marginalized and unsung

B y nancy zimmeRman | Po R tR ait By Daniel q uat

412 Four-Dimensional Sculpture

James Marshall strives to embody nature and beyond

B y Wesley P ulkka | Photos By k ate R ussell

414 Material Metamorphosis

Tasha Ostrander’s meditative process turns artist into magician

B y Rick l um | Photos By k ate R ussell

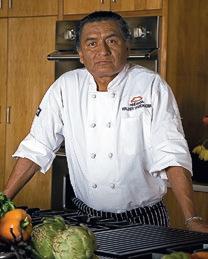

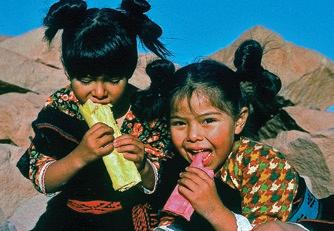

419 New Mexico’s Culinary Inspiration

420 Nourishing Culture

Native American chefs create a healthier future by reclaiming the past

B y nancy zimmeRman | Photos By l ois e llen fR ank

428 Back to the Future of Farming

Rancho Manzana forms a new bond in the relationship between grower and customer

sto Ry anD Photos By ga BR iella maR ks

437 Call it Ethos

Erin Wade wants to change the way we think about healthy eating and sustainable practices

B y Rena D istasio | Photos By seR gio salva D o R

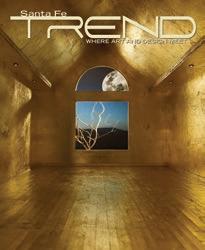

About the cover: Bedroom passage from a home in Colorado designed by Antoine Predock (1990), photo courtesy Robert Reck. Painting on far wall, Sasha vom Dorp, Unknown Frequency Sunlight (2011), archival pigment print mounted on aluminum. Painting on right-hand wall: Carlos Carulo, Nebula and Twelve Fragments (2023–2024), mixed media on canvas board.

As you open this retrospective issue celebrating the best of Trend magazine over the past 25 years, you may ask, “Why look back instead of charging forward?” At this fraught moment in history, it’s the ideal time to take stock, review where we’ve been, and chart a new course for the future. Our world has experienced massive changes—social, political, technological, and climatologic—over this past quarter-century, and Trend has chronicled these changes via the works of the many artists, architects, designers, musicians, chefs, and assorted dreamers who have graced our pages. By creating this retrospective—448 pages of our fondest memories and finest talent—we offer not merely a trip down memory lane but also an overview of the shifting aesthetic, emerging voices, and evolving techniques that keep Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico in the forefront of artistic accomplishment. Our mission from the beginning has been to champion the myriad visuals and voices of the artmakers who call New Mexico home. Those we chose to revisit in this issue represent a cross section of 25 years of coverage—for every Agnes Martin, Judy Chicago, and Dennis Hopper we have been equally committed to those who, like Emmi Whitehorse, Woody Gwyn, and Eli Levin, make their art largely away from the glare of the limelight. We’ve also brought you stories of the gallerists who support them, like the incomparable Riva Yares; of the initiatives that nurture them, like Albuquerque’s Art Street; and of the exhibitions that redefine the art-viewing experience, like Meow Wolf.

Equally passionate about architecture, we have long been committed to showcasing the ways in which visionaries like Antoine Predock, Bart Prince, Jeff Harner, Michael Bauer, and Michael Krupnick, whose stories are reprinted here, have evolved the relationship between the natural and built environments. Trend is also a magazine of design, and our issues regularly feature the industry’s most renowned craftspeople, from interior designers to landscape architects, who bring their expertise to crafting outdoor environments as beautiful as they are functional. Our culinary coverage has likewise focused on those chefs, restaurateurs, and purveyors who consistently reconsider and redefine our relationship with dining, the land, and the bounty we harvest from it.

Then there is Trend itself. We’ve lost count of how many times the death knell of print media has been sounded since we first went to press. Yet, here we are, a testament to publisher Cynthia Canyon’s unswerving belief in the power of the physical page, made beautiful by art director Janine Lehmann, who has been evolving this magazine’s distinctive look from the beginning. We must also mention the many dedicated photographers and writers who have focused their lenses and sharpened their pens to help make Trend one of the region’s most respected magazines of the arts. There are too many to mention here, but you’ll recognize their names in these pages. Some write and shoot for us to this day; some have left for other opportunities; while others, like Heidi Utz and Eliza Wells Smith, were taken from us way too soon. May they rest in peace. We will always hold them in our hearts as cherished members of Team Trend.

As we also hold our readers and advertisers. We will forever be grateful for your support, for your feedback, for finding within our pages not only information but also inspiration. Whatever the next 25 years holds for us, we hope you join us on our journey.

During the process of working with my team to put together a retrospective of Trend’s 25 years of publishing, I started to think about the word legacy, which Webster ’s defines as “something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor or from the past.” Then while I was trying to translate these thoughts to this letter, the sudden death of a young Trend team member—Duncan Evans Walker—left me reeling and reconsidering the impact our work has on others. This young man gave his heart and soul to his clients, and although he lived only a short 21 years, he leaves a legacy of how to live with determination, confidence, and grace. He was just one of the many people I have met in my 25-plus-year journey as Trend publisher who helped me establish and grow one of the top art magazines in the region. What has emerged from my team’s in-depth review of the past 25 years of coverage was a renewed appreciation of the timeless, far-reaching legacy of New Mexico’s artistic output.

Here in New Mexico we are blessed with a unique artistic legacy that extends back to prehistoric times. The sophisticated symbols and designs first created by Native artists have stood the test of time, remaining as contemporary and evocative today as they were hundreds of years ago. These deceptively simple images continue to inform the work of current-day artists, both Native and non-Native, adding a timeless quality to work that might otherwise be considered new and trendy.

Similarly, the Hispanic artistic legacy, shaped by the richly symbolic devotional art forms brought from Spain by the initial settlers, has embedded itself in the local aesthetic, as has a distinctive architecture that still finds relevance in modern building styles. Later waves of settlers have added, and continue to add, to the everevolving state of New Mexico arts. The result is a unique syncretism wherein the distinctions among past, present, and future become blurred, while new creations build on the commingled legacies of past artistic contributions.

To me, the word legacy also means something more. I think of the many intertwined stories of the people, past and present, famous or anonymous, who have contributed to our collective spirit and aesthetic. It has been my goal since the beginning to present Trend readers with a magazine that chronicles and builds on the legacies of these innovators and unsung heroes, honoring the artistic spirit that makes our little corner of the world a key player in the art and design world writ large.

To the extent that Trend has created its own legacy, I tip my hat to the talent not only of the people we cover but also the writers and photographers who bring these many stories to life. I owe a debt of gratitude as well to the steadfast crew that produces each issue—most notably art director Janine Lehmann, editors and writers Rena Distasio and Nancy Zimmerman, and production editor Jeanne Lambert.

Trend magazine could never have existed without all of the aforementioned builders of the New Mexican artistic legacy. It has been my honor and privilege to explore their vision and artistry in our pages, and I am grateful to be able to play a part in our region’s ever-evolving legacy of artistic excellence.

Cynthia Canyon Founder and Publisher

PUBLISHER

Cynthia Marie Canyon

EDITORS

Rena Distasio

Nancy Zimmerman

ART DIRECTOR

Janine Lehmann

PRODUCTION MANAGER & ASSOCIATE DESIGNER

Jeanne Lambert

PHOTO PRODUCTION

Boncratious

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Laura Addison, Jan Ernst Adlmann, Ellen Berkovitch, Ashley M. Biggers, Lyn Bleiler, Kathryn M Davis, Rena Distasio, Heidi Ernst, Gussie Fauntleroy, Jamie Holt, Sunamita Lim, Ric Lum, Devon Jackson, Gabriella Marks, Keiko Ohnuma, Stephanie Pearson, Rachel Prinz, Christina Procter, Wesley Pulkka, Bill Rodgers, Rick Romancito, Anya Sebastian, Eliza Wells Smith, Lynn Stegner, Pearl Tiresias, Heidi Utz, Teresa Zamora, Nancy Zimmerman

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Boncratious, Kent Bowser, Jennifer Esperanza, Lois Ellen Frank, Kirk Gittings, Douglas Kent Hall, Brenda Kelley, Gabriella Marks, Chas McGrath, Peter Ogilvie, Rachel Prinz, Daniel Quat, Robert Reck, Rick Romancito, Kate Russell, Sergio Salvador, Sarah Stathas, Cyndy Tanner, Dominique Vorillon, Donald Woodman

REGIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Sondra Lee Allison, 505-470-6442

ACCOUNT REPRESENTATIVES

Anya Sebastian, 505-470-6442

Duncan Walker, 505-470-6442

TAOS AD SALES

Bill Curry, 505-470-6442

NORTH AMERICAN DISTRIBUTION

Disticor Magazine Distribution Services, disticor.com

NEW MEXICO DISTRIBUTION

Ezra Leyba, 505-690-7791

ACCOUNTING AND SUBSCRIPTIONS

Patricia Moore

SOCIAL MEDIA MARKETING

Janna Lopez

PRINTING

Publication Printers

Denver, Colorado

Manufactured in the United States

Copyright 2024 by Santa Fe Trend LLC

All rights reserved. No part of Trend may be reproduced in any form without prior written consent from the publisher. For reprint information, please call 505-470-6442 or email santafetrend@gmail.com. Trend art+design+culture ISSN 2161-4229 is published online throughout the year and in print annually (20,000 copies), distributed throughout New Mexico and the US. To subscribe, visit trendmagazineglobal.com/ subscribe-renew. To receive a copy of the current issue in the US, mail a check for $35.00 to P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504-1951or go online to subscribe to the next issue at trendmagazineglobal.com/subscribe. Find us on Facebook at Trend art+design+culture magazine and Instagram@santafetrend

We’re seeking new and diverse voices! If you are a writer or photographer interested in contributing, please visit trendmagazineglobal.com/contribute and send your story pitches to santafetrend@gmail.com.

Trend, P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504-1951 505-470-6442, trendmagazineglobal.com

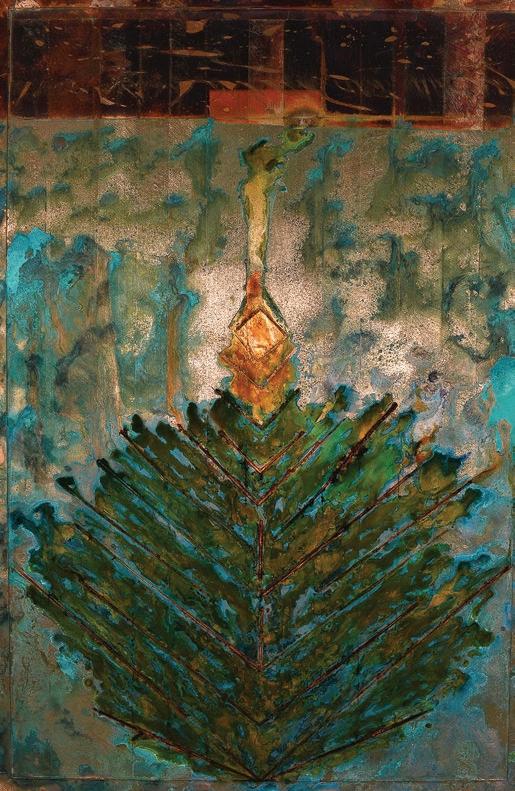

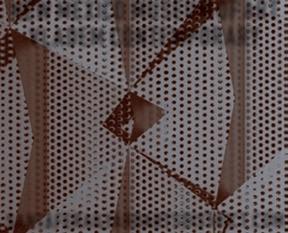

It was during his medical school studies in the late 1990s at Tulane University in New Orleans that metal artist Tim Church began to explore the possibilities of applying his knowledge of chemistry and machining to fine art as a way to generate emotion.

Inspired by the city’s rich cultural heritage, he decided to try to recreate one of the copper fountains he had seen during his walks through the city. “I thought they looked fun to make,” he says. “And they were.” Then he decided he wanted something for indoors.

“I kept experimenting, pushing the boundaries of the metal using various concentrations and combinations of organic acids and bases during different seasons to change colors.”

The result, a process he has since trademarked and calls “vibrant toning on copper,” combined the reactions of acids, bases, temperature, humidity, and oxygen on sheets of copper to create unique, multicolored wall art. Church’s first exhibition, in 2012 in Baton Rouge, sold out on opening night.

Now a chief medical officer in Dallas, he has been exclusively represented by Santa Fe’s Wiford Gallery since 2017. Church’s intimate partnership with the forces of Mother Nature draws color out of the copper rather than merely applying it, resulting in singular contemporary art pieces reminiscent of the patterns of nature. Each one is a statement about the power of organic transformation guided by the hand of the artist.

“Nature makes the acids and bases react, and their interactions affect what you see and feel,” he says. “No piece will ever be like another because of these factors—it’s impossible to perfectly recreate another one. The chemistry and experimenting with it are what’s interesting to me. I love that I get to work with nature to create fine art.”

Toms’ Evening Stroll, finished clay (available for preorder in bronze), 13 1/2” x 16” x 1”

TRANSCENDING THE MEDIUM

Low-relief bronze sculptor Jeremiah Daniel Welsh’s mastery of an ancient medium all but lost in the modern age is undeniable. Raised in a community where representational art was frowned on, his story is one of achieving recognition for his aptitude in the face of strong resistance. The gift of those challenging circumstances was a steep trajectory in developing his talent and art. Now his work demonstrates that he is one of the best low-relief bronze sculptors in the world.

Welsh’s ability to create intricately detailed, representational and contemporary portraits and nature scenes began when he encountered a ceramic artist from Korea who set such high standards for his personal work that he would destroy pieces that did not rise to those exacting expectations. This early exposure to Asian artistry was later reinforced while Welsh lived and sculpted professionally in Japan. Both experiences profoundly impacted his desire to continue pursuing artistic excellence.

Welsh further developed his skill set during the 15 years he spent as a contract relief sculptor for an international bronze foundry, where he produced upwards of 175 diverse pieces annually. This intensive practice honed his attention to detail and helped him develop an intimate understanding of the foundry process, which he insists on participating in for every piece.

Based in Colorado Springs, Welsh is the most acclaimed low-relief bronze sculptor working in the medium. Consistently awarded top honors by the National Sculpture Society at their annual juried exhibitions, he was also commissioned in 2022 to create the 50th anniversary medal for the Brookgreen Gardens in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina.

Whether working on a commissioned piece or his own designs, he is driven to continually explore the illustrative possibilities of the medium. “What you show the viewer on the surface is important,” he says, “but convincing them that what they cannot see is actually there, that’s where the finesse comes in.”

In addition to representing original living artists, Wiford Gallery also provides a service for collectors interested in acquiring or selling historical works of art. “Not everyone

wants to go through the process of getting involved or continuing with art auctions,” Wiford explains. “So we work on their behalf to find what they are looking for and match sellers with suitable buyers.”

Wiford’s passion for art has clearly not diminished one iota since he started the gallery back in 2002. “Putting beautiful art into the world satisfies an essential part of my soul,” he says. “It is our honor to serve our exceptional artists, our collectors whose support of the arts energizes and expands that process, and our team members who connect all the parts that make the existence of Wiford Gallery possible.”

Visions of Farewell, faux finished resin (available by order in bronze), 23” x 11 3/4” x 5/8” (unframed)

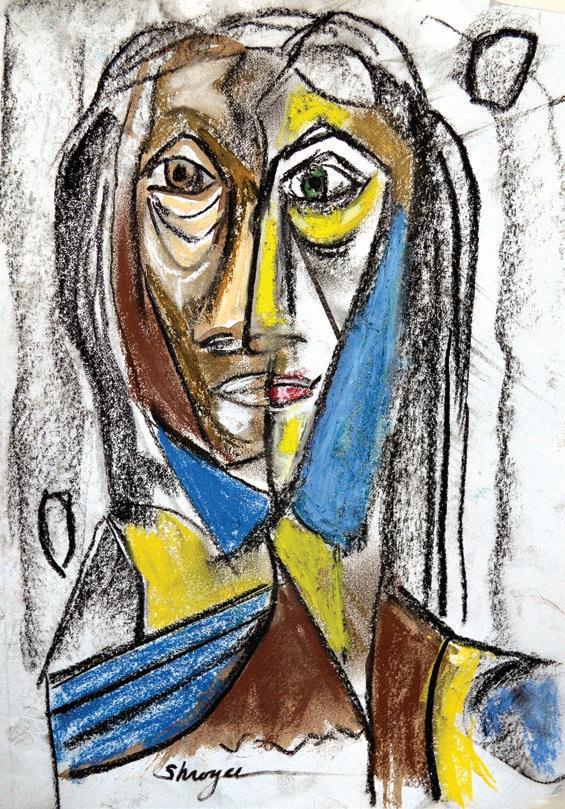

Charlotte Shroyer grew up in a rural area of Ohio, where neither her family nor the local school system placed much value on art. It was picking up a paintbrush for the first time as part of a project required for her elementary education certification at Ohio State University that planted the seed for her future passion. She began taking art classes at various universities while earning a bachelor’s degree in French. She later became a college professor after receiving a PhD in language and learning disorders. It was only after a serendipitous move to Taos many years later where she worked as writer and editor for a small art publication that the “art seed” finally took hold.

“I am inspired by the world, its people, archaeology, and cultures,” Shroyer says. “My favorite authors, like Lawrence Durrell, Orhan Pamuk, Thomas Pynchon, all explore duality of personality—what the individual shows to the world and what remains hidden—and that is what fascinates me.”

Shroyer also remains impacted by her work with children and adults who have limited language skills, and she has developed visual systems that convey information more symbolically. She cites the early Cubism of Picasso and later works by Ecuadorian artist Oswaldo Guayasamin as influences.

In addition to her paintings, which have earned numerous national and international awards, Shroyer also makes Navajo-style woven pillows and rugs, as well as wall hangings, table runners, and ethnic baskets. She also enjoys doing custom work for interior design projects.

Like many people, I love a good accessory. I’m not really one to follow the crowd when it comes to clothes, but even though I tend toward the classics (black, denim, and more black), I still like one part of my outfit to make some sort of modern statement—usually an accessory. In my book, you can’t beat jewelry. Compare me (please!) with that perennial style icon Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’ s, wearing an understated monochrome ensemble paired with a killer necklace or large costume earrings.

So when I recently made my way through the jewelry section of the shop at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, New Mexico, I was mesmerized by the work of Pat Pruitt and Aaron Brokeshoulder. I started mentally flipping through my closet to remember what I have that would work with the dozen pieces each of them has on display. They have such different styles, but each in his own way takes themes or techniques from traditional jewelry design, both Native American and other, and modernizes them.

The gift shop’s manager, Ira Wilson—guitarist and lead vocalist for Albuquerque’s award-winning rock band Red Earth for more than a decade—likens Pruitt and Brokeshoulder to groundbreaking classic-rock guitarists such as Eddie Van Halen. “Those guitarists started with a Fender or a Les Paul, and see how innovative they were,” says Wilson. “With Aaron and Pat, the basics are the same, but they’re finding a way to express themselves that’s uniquely them.”

Of the two, Pruitt has the rock-star personality, and not just because of his hot-rod hobby. He started learning the silversmithing trade 20 years ago under traditional jewelers on the Laguna reservation in Paguate, New Mexico, an hour west of Albuquerque, but for the past 15 years he has made body-piercing jewelry of all shapes and sizes. He works in stainless steel, so when he began his own jewelry line (because he couldn’t find a whole lot of what he calls “cool guy stuff” out there), he stayed with that material.

Pruitt is one of the few fine jewelers to work in stainless steel exclusively. And he does it well: He was presented with the national Couture Jewelry Award in 2007 in the alternative metals category. His stuff is undoubtedly cool. I love a great cuff bracelet, so I was really attracted to the large ones on display at the Cultural Center, one with a timing belt along the top, another with stingray skin. Pruitt’s materials give the cuff shape a whole new modern edge.

“I am always looking for work that pushes the envelope. I loved Pat’s work immediately because his quality of workmanship was superb, because it is based on the traditional but goes to the extreme,” says Victoria Price, owner

of Victoria Price Art & Design in Santa Fe and daughter of film legend and noted art collector Vincent Price. Her gallery showcases contemporary home decor, art, and jewelry and has featured Pruitt’s work for five years.

“He’s part of a new generation of artists whose work will not just be associated with being Native American or from the Southwest,” she continues, “but will be seen as having national and even international appeal—even as their heritage makes their work more compelling to many.”

Pruitt also makes thinner cuffs inlaid with copper, silver, and/or 24kt gold, and here’s where you’ll notice some of the Native influence in his work. He says I hit the nail on the head when I tell him I see rivers and mountains represented in the thin undulating lines. Often, though, he bucks conventional

Ira Wilson likens Pruitt and Brokeshoulder to groundbreaking classic-rock guitarists

design in favor of what he calls “badassedness.” Says Pruitt, “I take a different approach to my work because with stainless steel there is no tradition.”

Aaron Brokeshoulder, on the other hand, creates designs very much rooted in tradition. I’m drawn instantly to a polished sterlingsilver cuff that has rectangular coral inlays along the length, a center medallion of a raised coral, and Native symbols stamped into the inner and outer surfaces of the bracelet.

The symbolic storytelling is integral to Brokeshoulder’s work—and fits the jeweler, whose personality seems more like a roadie, or a lyricist, if his friend Pruitt is lead guitar. One bracelet tells of dancers asking a turtle for the blessing of rain. Another depicts two spiders meeting for mating. “I heard stories from my great-grandpa before he passed away, and I incorporate that stuff into my jewelry,” says Brokeshoulder, who works in his garage studio in Albuquerque. He learned smithing from his father at his Santo Domingo Pueblo home. Working his way up until he began designing on his own, Brokeshoulder has now won many artmarket awards—and a national following.

“Aaron’s jewelry is a combination of a continuing approach to tradition that doesn’t necessarily stay in the box,” says IPCC shop manager Wilson. “He likes to hang on the edge.” And that’s exactly where the next cuff I see goes. Also in a traditional shape, this one has a dark, pebbled surface: oxidized silver. It’s a relatively new technique for him, one that resembles sand-casting. Brokeshoulder retains the stamped symbols on the inside of this piece, but the outside has three raised lines— rivers—and four raised dots, which stand for the four directions (north, south, east, and west, traditional Native symbolism).

Both Brokeshoulder and Pruitt are hanging on so many edges in their work—in technique, design, and material. I can’t wait to see their next breakthroughs, but for now I just like dreaming about which one would look best out of the glass cabinet and around my wrist. R

From the Spring/Summer 2010 issue

It was the discovery of an old, abandoned blacksmith’s forge in a school cupboard in 7th grade that led to Christopher Thomson’s career as a master blacksmith and artist. “I was drawn to it immediately,” he recalls, “and that feeling has only grown stronger and more intense over the years.” He now has a 6,000-square-foot studio at the base of Rowe Mesa, and his award-winning, hand-forged pieces, both practical and decorative, have been featured in galleries from New York to Los Angeles.

Among his most popular pieces are his series of brightly colored iron sculptures, forged and hammered into undulating spirals and waves and available in sizes ranging from three to nine feet high. Their colors were the inspiration of Thomson’s wife and business partner, Susan Livermore, also an artist. “Painting steel in vibrant colors had never occurred to me,” he admits, “but they really bring the sculptures to life.” Powder-coated, they can be displayed outside or inside, and some can even be hung on the wall. Whatever their setting, these ironworks embody new growth, upward movement, and an invigorated sense of momentum for our collective spirit.

Thomson’s works are also designed to be touched. “I don’t make pieces for people to just stand and contemplate from a distance,” he says. “I want them to experience the same kind of hand/eye connection that goes into the formation of everything I make. Creating things that people touch every day, from sculptures to fireside tools, communicates some of the magic I feel when making them.” Owen Contemporary now represents Christopher Thomson’s sculpture.

Turquoise Chinlone, Single Blooms and Single Musings, powder-coated forged steel sculpture

Master of multimedia, he invites all our senses to the party

On his website, Terry Allen calls himself an artist/ songwriter, but the truth is much more complex than that. As he puts it in his soft West Texas drawl, we are beings of at least five senses: “You don’t wake up one morning and say, ‘I’m just gonna hear today.’”

Allen’s art engages not only all of our senses, but our intelligence too. He is a writer, musician, draftsman, sculptor, and videographer, and at his foundation he is a profoundly conceptual artist. He doesn’t make visual art that is set to his music, for example, so much as he serves as a multi-talented (and many-tentacled) stage director.

A performance of his most recent work, SongStories (From the Bottom to the Top to the Bottom of the World, etc.), was conducted this summer in an eight-story tower at the Oliver Ranch, 100 acres of sculpture in the heart of Sonoma County in Northern California. The piece serves as a model that typifies work by Allen—if indeed there is anything typical about him. The location for SongStories, Ann Hamilton’s The Tower, is a site-specific acoustic environment based on the discovery in Europe of an ancient cattle well with one set of stairs for the bovines to go down and drink, and another for them to ascend into their pastureland. Hamilton’s concrete structure is open at the top, while

a pool of water reflects the sky at the bottom. Audience and performers occupy some 125 seats up and down the double-helix staircases.

Allen composed the music, while the dramatic piece was written with his wife, actress Jo Harvey Allen (probably best known for playing the sex therapist in the 1991 hit Fried Green Tomatoes). She recounted stories from the protagonist’s life while Allen and his ensemble of musicians played at various levels of the tower. (The sound was managed—expertly—by one of Lady Gaga’s technicians.) The performance was followed by a concert on a regular stage outside the tower Allen recalls that it was odd to make the

transformation from hearing the music vertically to the more horizontal range diffused from onstage.

Usually, “it’s a living hell when we collaborate,” Allen says of working with his wife. “But this was so smooth; really it was an editing process,” where each wrote separately and then came together to join the parts. The smoothness may be the result of the couple having known one another since they were 11; they grew up together in Lubbock, Texas, and celebrated their 49th wedding anniversary this year— though neither looks old enough.

Probably the tie that binds them most, aside from their two sons Bukka and Bale, is that they “know the same stories.” Each was born with that spellbinding storyteller gene; their love for the craft and unique take on how to narrate a vision is what keeps them vibrant as collaborators, spouses, and artists with their own careers in what Allen calls “a funny balancing act.” (He claims that having a wife who is an actress is a bonus—she works for him cheap.)

Music and performance are natural mediums for Allen. His mother was a musician; his father, a retired baseball player for the St. Louis Browns, took over an empty Foursquare Baptist church where he held dances with live bands as well as popular wrestling and boxing matches. This was in the late 1940s and ’50s, the era of segregation. On Friday nights black musicians played, so Allen grew up with the likes of T-Bone Walker, countered by Saturday nights’ all-white stars, including Hank Williams.

He hated high school, where he got into trouble for drawing and writing songs— “the two things I wound up doing” as an adult. A teacher told him about Chouinard Art Institute (now the California Institute of the Arts, or Cal Arts) in Los Angeles, and within a half an hour of marrying Jo Harvey, the two had crossed the Texas state line, headed west. In L.A. they hosted Rawhide and Roses on one of

the country’s first independent FM radio stations, KPPC out of Pasadena.

“Jo Harvey told lies about everything she could think of,” Allen says of the show, which ran on Sunday mornings, followed by a blues show. Everyone stuck around during an hour break for the news before Firesign Theater, with a motley crew from the morning shows, offered its unique brand of live radio hijinks for the rest of the afternoon. It was a wild and woolly time of “anything goes” in the ’60s, and the Allens became known as part of a rich consortium of creativity. Nothing could hold them back after that kind of notoriety, and Allen’s art in all its forms reflects his original, independent thinking.

Ever since he landed upon an anthology of writing and drawings by the French playwright, poet, actor, and theater director Antonin Artaud at City Lights Books in San Francisco decades ago, and basically begged it from Lawrence Ferlinghetti— “Just take the damned thing,” Ferlinghetti growled at the young Allen—Artaud has been Allen’s great obsession. In his essay “Theater of Memory” (Dugout, 2005), David Byrne of the Talking Heads notes that “Allen spews out one of these epic works every decade or so . . . .”

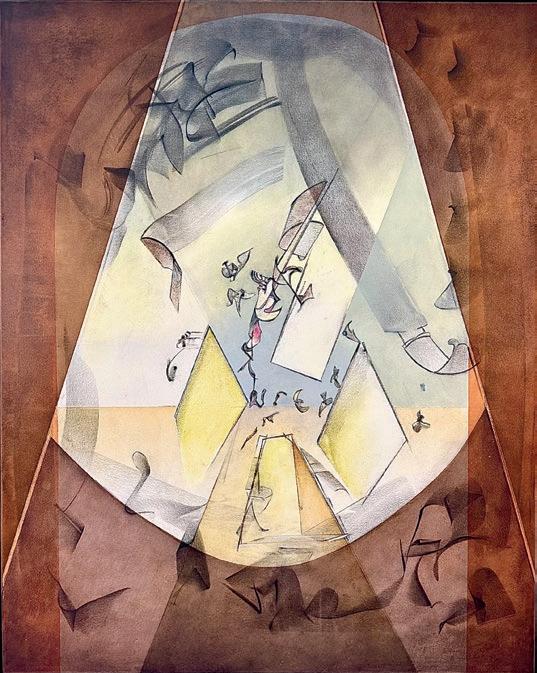

For the last several years, his epic piece has taken shape as the installation work The Ghost Ship Rodez , about Artaud’s 1937 sea journey from Dublin to a mental instititution in Rodez, France. An opium addict, Artaud was in withdrawal and hallucinating, and was straitjacketed and chained to his cot below decks for the 17-day journey. Ghost Ship is a phenomenal work of art, consisting of videoed performances by Jo Harvey, plus installation, drawing, painting, music, and theater—particularly theater as Allen realizes it through Artaud’s writing. Most important, Ghost Ship has everything that makes for a great story: appallingly sinister humor, tragic lost beauty, an unrelenting search for redemption, the viciousness of corporeality, and more than a trace of tenderness. R

From the Fall 2011/Winter 2012 issue

BY

A new Santa Fe art installation explores a fantastical family narrative

You enter a large building formerly known as the Silva Lanes bowling alley, buy your ticket at the counter, and proceed into what’s apparently someone’s front yard. It’s dark as night, stars shine above, and light radiates from the porch and windows of an old twostory Victorian. It’s not your neighbor’s place, not your childhood home stirring up memories, but the keystone of The House of Eternal Return, a permanent, interactive installation by the collective art group Meow Wolf, set to launch this fall. Situated within the Meow Wolf Art Complex on Rufina Court in the geographical heart of Santa Fe, the installation unfolds over 20,000 square feet and two stories. Its overarching narrative is of a house divided, not in the traditional sense, but through

space and time, as if it’s been drawn into a black hole only to emerge reassembled in wildly fantastic ways on the other side.

Visitors are presented with the story of the imaginary Sig family—a mom and dad, brother and sister twins, an uncle, and grandfather. Each possesses a unique character, but also abilities beyond natural that when exercised precipitate a fracture in space and time. This event occurs within their home, causing the family’s memories, secrets, and fantasies to expand and contract in unusual ways. An uncle’s dream of success, for instance, takes the form of a travel agency, and a family remembrance of a trip becomes a cave of luminous lights and interactive sounds. A place of touch-

sensitive stalagmites and stalactites (the father’s retro-game nostalgia) turns into a light-filled arcade and pinball experience that immerses you in the game.

Visitors can discover the family’s story through audio, video, and tangible objects, like a cell phone. The group even outsourced the creation of an app that allows spectators to snap photographs at various points and pull up further information. Yet the house takes up only about a tenth of the installation. One can explore it and then by various egresses, such as through the refrigerator or backdoor, discover the remaining spaces. Some of these were conceived by Meow Wolf members, while others are the result of applications from artists across the nation.

This collaborative approach has defined the Meow Wolf pack since a core group of members established it in 2007. They’re best known for The Due Return, an immersive installation in the form of a 73 ½-foot, two-story ship that was moored outside the Center for Contemporary Arts long enough to draw 100,000 visitors in 2011.

The House of Eternal Return is Meow Wolf’s most comprehensive project yet, exemplifying the group’s mission to build multifaceted projects that provide a full sensory experience. “It’s an environment that you walk into, that surrounds you,” says Emily Montoya, a core member and the group’s graphic designer. “It’s not ‘don’t touch this, don’t open that.’ It invites you to be a character within it at some level, to share its reality and to make it your own.”

Making it your own is what the story’s about. Although the fictional family members can all interact with the element of time, it was the twin brother Lex—aided by his uncle—who conducted an experiment gone wrong, putting the home at the focal point of a rupture in physics. Yet the real gist of the story is a reward to spectators who search for it, uncovering the secrets of the narrative and how family dynamics are written into time and space.

More than 85 artists and 180 volunteers have contributed to Eternal Return in a space big enough for nine Due Returns

Since January 2015, Meow Wolf has assembled various teams: technology, performance, narrative, graphic design, aesthetic direction, administration, volunteer coordination, and more, each with a project leader, several artists, and a greater number of long- and short-term volunteers. “Many of our new artists have expressed that they’re taking this opportunity to build a piece they’ve been dreaming about making for years but have never had a venue for,” says Caity Kennedy, project coordinator.

Local artist Erika Wanenmacher has been involved with Meow Wolf since its inception. She champions the collective’s niche in the city’s art scene—its vitality, diversity of shows, and general “artistshelping-artists” mentality. Her project is

a dome of meticulously crafted iridescent animal eyes located deep within Eternal Return, and it includes the ever-watching eyes of the family pet and other significant animals.

Others involved in forging this world include volunteer painters, filmmakers, and actors, as well as those working in welding, lighting, and website building. Following a town-hall-style public meeting at the Santa Fe University of Art and Design, Meow Wolf also coordinated youth involvement. Projects headed up by youth include posters, drawings, notebooks, and other items belonging to the twins in the narrative. And two kids were cast to play the twins in various films, photographs, and audio recordings throughout the space.

Zubin, age ten (like the twins), built a Minecraft version of the entire installation, and Liam, 11, wrote and illustrated the notebooks of Lex. For Liam, Meow Wolf changes the face of

what art can be. He recalls the impact of seeing The Due Return “It’s cool that art can be a world,” he says, “a place you can walk into.”

Resources, both financial and technical, helped turn Meow Wolf’s dreams of an art center into reality. In early 2015, CEOs Sean Di Ianni and Vince Kadlubek made a winning pitch to Albuquerque-based Creative Startups, followed by the purchase of the Silva Lanes building and the public support of Santa Fe local George R. R. Martin, author of the popular Game of Thrones book series. Along with a Kickstarter campaign and private donations, the Meow Wolf Art Complex took form. In addition to the installation space, it will include 19 artist studios, a learning center, a gift shop, and a smaller gallery with rotating shows. The group’s hope is that the complex will receive 100,000 visitors a year for Eternal Return alone, a figure Kadlubek says is just slightly less than the annual attendance

of the Santa Fe Children’s Museum and about a third of Albuquerque’s Explora museum, both of which were chosen for their interactive appeal. The number doesn’t include those who visit the gallery or performance center. There will also be students from ArtSmart and other programs held at the Loughridge Learning Center, which at night will double as a venue for creative classes aimed at adults. With its worlds within worlds, Meow Wolf’s expanding community of artists has created an exhibition space unlike any other. The House of Eternal Return begs visitors not just to view but to also explore the world before them and become part of its story. It also invites them to join a created world and its fictional family, but with its creators, designers, even fellow visitors, forming a makeshift family across the boundaries of space and time. R

Fredrick Prescott’s larger-than-life, brightly colored, solid-steel sculptures are truly one of a kind. Engineered to move in the wind or be activated by hand, they combine reality with fantasy in an ever-evolving variety of magical images. There are 30-foot-high giraffes alongside pink flamingos, elephants, seahorses, dinosaurs, dragons, and many other real and imaginary creatures.

Everything is created in a 30,000-square-feet studio in Santa Fe. The process is inevitably complex, starting with a drawing transferred to a computer and then on to a machine that cuts sections in steel. The pieces are then powder coated with a spray gun, sandblasted, and then fired in a massive oven that heats the environmentally friendly powder paint up to 500 degrees, melting it into a glossy finish. A final

clear coat protects the work from the weather if it is to be displayed outdoors.

The enormous works are transported all over the country, strapped down on a huge trailer hooked onto a big truck, to be exhibited in museums, public parks, schools, galleries, and private homes. Prescott is also open to commissions and over the years has completed many, including some for celebrities such as Michael Jordan and Steven Spielberg.

The gallery on Agua Fria Street is currently showing a retrospective, with photographs and early works that demonstrate Prescott’s artistic evolution over the years. One may wonder: After a career that spans more than 50 years, has he ever run out of ideas? “Never,” he says. “The problem is too many ideas and not enough time.”

Rose Masterpol knew when she was just 15 that she would become a painter. Nothing else made sense to her.

The contemporary abstract artist, who studied at the California Institute of the Arts and was a graphic designer for 30 years, paints her “Geometrix” series in a style that draws on the formal language and optimistic spirit of 20th-century Modernism. Working in her Santa Fe studio, she creates vivid, colorsaturated forms that connect, overlap, and intertwine as they evolve in the viewer’s eye, their bold lines and energy transforming into dynamic geometric and architectural forms.

“I want to help the world feel something when they look at my art,” Masterpol says. “It could be a sense of happiness or lightness, or simply a good feeling. Not every piece of art will do this, but that is my sole wish and why I paint.”

Masterpol’s art can been seen online at masterpol.com and at Nuart Gallery in Santa Fe, Artful Sol in Vail, Merritt in Baltimore, Pryor Fine Art in Atlanta, and Cheryl Hazan in New York City.

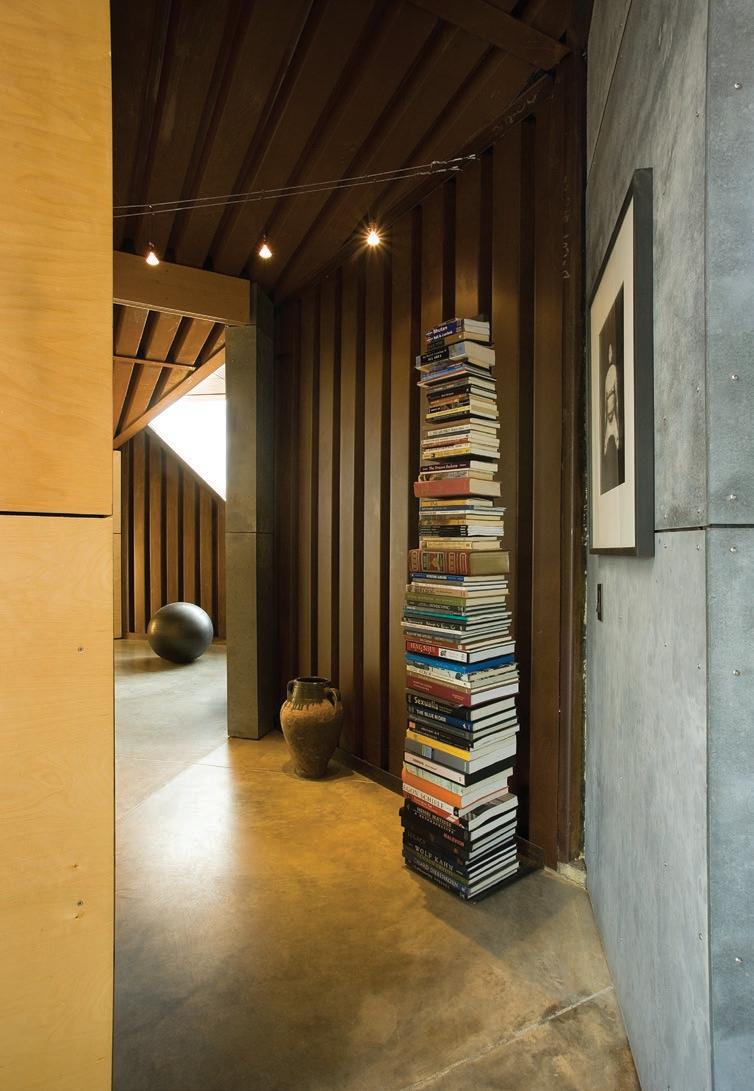

Renowned designer Alexander “Sandro” Hayden Girard was responsible for some of the Mid-Century Modern era’s most innovative designs in furniture, housewares, and interiors. Much of his work he produced from his studio in Santa Fe, where he moved with his wife and children in 1953. In the years that followed, Girard made an indelible mark on America’s and New Mexico’s artistic and architectural landscape, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire and excite design enthusiasts and visitors alike.

Girard was born in New York City in 1907 and raised in Florence, Italy. His Italian father—a master woodworker and an arts and antiquities dealer—was likely a large source of his early inspiration. Girard pursued his formal education at the Royal School of Architecture in Rome and at New York University.

While working in New York in the 1930s, the soft-spoken and serious Girard met and married his wife, Susan Needham March. They were adoring partners, traveling the globe and amassing a folk art collection that would become the largest in the world. Along the way, they also befriended some of the era’s greatest artists and architects, including Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames, and fellow New Mexico transplant Georgia O’Keeffe.

In his early career, Girard had offices in Florence, New York City, and Detroit and Grosse Point, Michigan. He designed radio bodies and a factory for Detrola Radio, facilities for Ford and Lincoln car companies, furniture for Knoll, and several residences as well. In 1947, in a precursor to several later collaborations of the two masters, Girard joined Saarinen’s team for its award-winning design submission to the St. Louis Gateway competition—the St. Louis Gateway Arch.

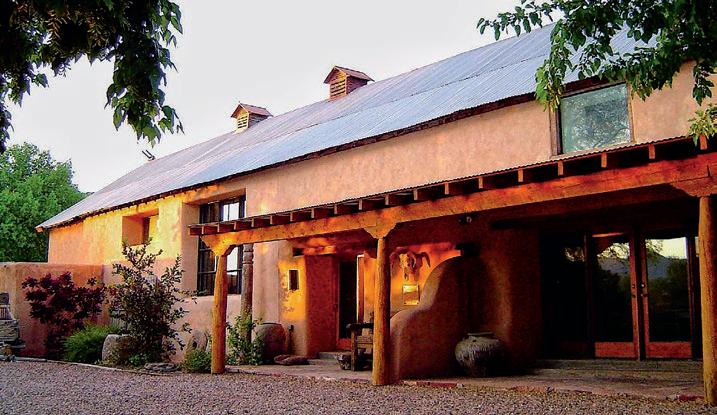

Girard’s life changed in 1952 when his friend of nearly 15 years, Charles Eames, offered him the position of Director of the Fabric Division at Herman Miller. It was at this same time—fueled by a passion for folk culture, a desire to be in a suburban environment, and a need to be accessible to his bi-coastal clientele—that Girard moved his family into a nearly 200-year-old hacienda in Santa Fe.

From his office across the dirt road from their home, Girard designed lines for Herman Miller, including furnishings, textiles, and wall coverings for the interiors of Mid-Century Modernist master architects like George Nelson, Saarinen, and Eames, as well as a diverse array of projects that ranged from the interior architecture of star-quality restaurants in New York to colorful,

worldly interiors to complement the stark Modernism of Saarinen. Girard also designed functional items including a tableware line for Georg Jensen and both the interiors of and products for the Herman Miller Textiles and Objects showroom and Herman Miller showrooms in Grand Rapids and San Francisco.

Although Girard would work for Herman Miller until 1975, he accepted many other commissions from clients throughout the country, including several right here in New Mexico. In 1966, he turned his attention to a complete rebranding of Braniff International Airways, not only creating new and coordinating color schemes for airplane and ground equipment, but also revamping nearly 17,000 company items—everything from the buttons on the captains’ uniforms to matchbooks, signage, and furniture. He even redesigned the typeface for all of Braniff’s printed materials.

Ten years after moving to Santa Fe, restaurateur Bill Hooten approached Girard to renovate the main house of the McComb residence on Canyon Road into a restaurant. In the 100 years since it had been built, the residence had grown from a single room into a sprawling complex of buildings, inspiring the apt naming of the new restaurant—the Compound. Leaving the blended Spanish Pueblo Revival and Territorial architecture of the exterior and the walled courtyards and gardens alone, Girard added only a simple front entrance portal . On the interior, he dismantled the maze of tiny rooms, opening up the space to create an axial arrangement of dining rooms along one side of an open hallway and a bar and exterior patio along the other. He replaced a load-bearing wall with a tree trunk, angled the bancos to create personal dining niches, and sank the bar—a reference to the conversation pit he invented and installed in his own home nearly ten years before.

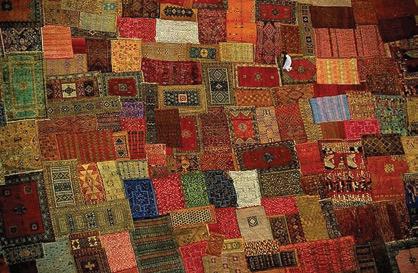

Girard was playful in the way he treated the whitewashed interior. For decoration, a patchwork of Mexican and Navajo weavings “tiled” the flat ceilings of one, while a ten-foot-long painted snake undulated to dramatic effect along another. Three-dimensional murals and inlaid wood doors were added throughout, and he decorated nichos and stands with pieces from his own folk art collection. Girard designed the table settings as well, placing white

china against crisp ecru tablecloths, finishing the bancos in faux leather, and designing a curvilinear white oak chair for additional seating. And again, he designed a unique typeface for the menus and signs. When completed, Architectural Forum deemed the Compound “The Town’s Newest and Best Restaurant.” Today, it is the last of the Girard-designed restaurants in operation, and nearly 50 years after its opening still maintains a reputation for exceptional dining and service.

Another of Girard’s renowned New Mexico projects is his mosaic/mural for the sanctuary of the First Unitarian Church of Albuquerque. The sanctuary was designed in 1964 by Harvey Hoshouer, an MIT graduate, former Girard employee, and collaborator with such legendary architects as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Harry Weese, and I.M. Pei. Hoshouer hired Girard to design an altarpiece for this starkly modern space, a 40' x 8' mosaic comprising 5,000 wood tiles harvested from abandoned barns purchased from ranchers in the Jemez Mountains and spotted by Girard’s son Marshall at horseback riding camp. Father and son hand-disassembled each barn, starting with the roof, stacking each board with cardboard between, and loading as many trailers as it took to get the barn down to Santa Fe. The wood was cut into three-inch squares by a church member and installed into an arrangement of colors, shades, and symbols by Girard’s team. The colors are original to their reclaimed condition, and include tar-scarred roof sheathing and stained and painted details. Completed in 1965, the mural depicts 22 symbols representing the wisdom of the world’s religions.

The First Unitarian mural was not Girard’s first or last. He also designed the 180-foot-long, three-dimensional Reflections of an Era mural for Saarinen’s John Deere headquarters in Moline, Illinois. Girard and five other team members scoured antique shops throughout the United States to collect the mural’s more than 3,000 three-dimnensional pieces of company memorabilia dating as far back as 1860. Its background, though mostly obscured, is also reclaimed wood.

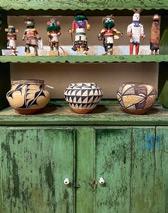

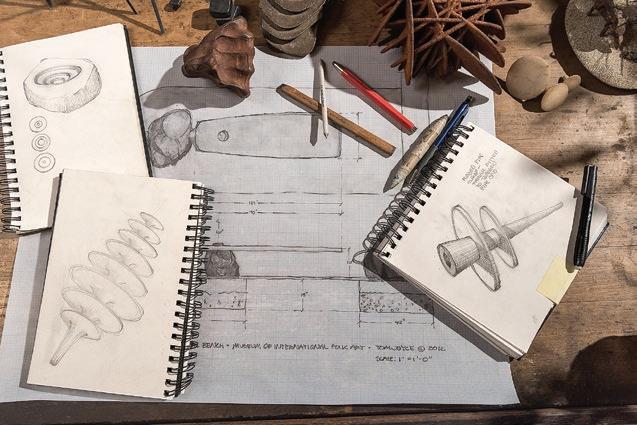

Girard’s design for the Multiple Visions: A Common Bond exhibit at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe showcases nearly 10,000 of his and Susan’s folk art pieces. The exhibit, located in an addition to the museum’s original John Gaw Meem structure designed by Hoshouer, first opened in 1982 and captivates with unique displays that engage not only the art itself, but our response to it, asking us to confront our intellectual and emotional mindsets by illuminating ideas of sameness, difference, and perspective. In placing the collection’s multitude of objects into unexpected arrangements, or locating pieces in places we may not have predicted and not explaining any of it, Girard seems to suggest that color, pattern, and language—and therefore ideas—are perhaps more fluid than we may have believed. As if illustrating this, the entrance to the exhibit cites an old Italian proverb often cited by Girard: “Tutto il mondo e paese” or “The whole world is one hometown.”

After his death in 1993, Susan Girard unsuccessfully attempted to find a writer to prepare a retrospective on her husband’s work. When she passed on several years later, their children searched for someone to commit themselves to their father’s legacy and tell his story. They eventually found Todd Oldham, a renowned designer in his own right, whose family homestead in Abiquiu gave him an understanding of the New Mexican culture in which Girard wished to immerse himself and for which he “left civilization” in order to do so. Oldham had previously produced design compendiums of Charley Harper and Joan Jett; had collaborated with legends Michael Graves, Camille Paglia, Amy Sedaris, and John Waters; and produced design studies on Mid-Century Modern aesthetics, embroidery, collage, and fabric printing and dyes. With help from Girard’s children and grandchildren, in 2011 Oldham and writer Keira Coffee produced an exceptional monograph.

In the 664-page tome, titled Alexander Girard , Coffee states, “In his lifetime Girard created not just a new style but a style of looking at things. He raised questions about how we make things, how we notice them, whether things speak to us or we speak to them. From the beginning of his career, Girard had an interest in the concord among lines, objects, colors. He disregarded trends and went to work showing others his discoveries.”

Throughout his career, Girard created thousands of simple, elegant, and colorful designs for the humanist MidCentury Modern aesthetic. He was more concerned with eliciting a feeling for the space than in intellectualizing the design. One newspaper of the time noted, “If Girard did it, it’s not just another anything.” Perhaps because of this, unlike much of the design of the period, Girard’s work is still venerated: his fonts and typographies have been reinvigorated by House Industries in the form of blocks, games, puzzles, and nativity sets; Elektra introduced a bicycle with Girard details; and MaXimo Design, Urban Outfitters, and Anna Sui have Girard details in their collections.

Although he was an internationally renowned designer, New Mexico was Girard’s spiritual as well as literal home. Through their use of reclaimed barn wood from the Jemez Mountains, the First Unitarian Church mural in Albuquerque, the patio doors of the Compound restaurant in Santa Fe, and the Girard exhibition space at the Museum of International Folk Art all illustrate the connectedness Girard felt to New Mexico’s landscape and history. That reflection of age-old traditions reinterpreted in a modern way remains one of the most timeless and engaging aspects of his work. R

From the Fall 2012 / Winter 2013 issue

An artist lives and works in his great-grandfather’s studio

There’s an empty nicho oddly situated near the floor in Andy Mauldin’s kitchen, in the adobe structure his great-grandfather built in 1919 on the street called Camino del Monte Sol, which runs between Canyon Road and Old Santa Fe Trail in Santa Fe. Mauldin thinks the odd little space may have been where the phone company installed a wire box, way back in the day, for phone service to what was the property’s art studio. While Mauldin doesn’t know for certain that his great-grandfather—the renowned painter, architect, and furniture designer William Penhallow Henderson—actually had a phone, the sight of the nicho prompts an unexpected remembrance: “My great-grandmother stopped them from putting up signs out there [that would name Monte Sol] Telephone Road,” Mauldin says, gesturing in the direction of the narrow street.

The Hendersons moved from Chicago to Santa Fe in 1916 because Alice Corbin Henderson, a poet and co-founder of Poetry magazine, was suffering from tuberculosis and hoped for healing in New Mexico’s clear, dry air. She spent five years at Sunmount Sanitorium—a tent-city tuberculosis treatment center at the end of Monte Sol whose existence meant telephone service would soon snake its way along the eastside lanes. William and their daughter, “Little Alice,” lived in a small rented house on Monte Sol while William built himself a studio up the street. Alice joined them after recovering her health. The studio was William’s until his 1943 death; in the 1950s, Little Alice converted it to a living space. Since 1971, Andy Mauldin, now 59, has called it home.

Above: The fireplace nook in Mauldin’s studio/living room. William Penhallow Henderson’s furniture craftsmen built the wooden window shutters, featuring Henderson’s carved-rose motif, and the hand-adzed cabinet doors.

Right: Mauldin gazes out the studio windows that provided north light for his great-grandfather’s easels in the early 20th century, just as they do now for Mauldin’s artwork.

Far right: In Mauldin’s bedroom sits a cabinet designed by Henderson and built in the early 1900s. The room was once Henderson’s furniture-making shop. An oil painting by David Barbero

It’s a good fit, since the descendant of the Works Progress Administration muralist is a painter too.

Mauldin explains, touring the kitchen, “This was Henderson’s drafting room. There would have been a secretary here by the door to greet you and drafting tables under the windows.” The room, with its low ceiling, blue painted cabinets, and row of south-facing windows filled with geranium pots, is like a postcard for old Santa Fe. And Mauldin, too, seems to have stepped into modern life from a slower past. His speech is thoughtful, his movements unhurried. He has no computer, says he has no interest in TV.

“I listen to the radio a lot,” says Mauldin. “It’s not my intention to live as an anachronistic anomaly; it just kind of works out that way.”

Surrounded by rustic, hand-carved wooden furniture of his great-grandfather’s design—Mauldin’s bedroom was Henderson’s furn iture studio— the artist paints in the large, high-ceilinged room where Henderson’s own easels once stood. Outside the kitchen windows, lush grass and flourishing roses speak to Mauldin’s other pas -

sion: gardening that resembles an English-cottage style.

Mauldin’s artistic leanings literally come with the territory—not only were William and Alice Henderson an influential part of Santa Fe’s early art scene, but also another of Mauldin’s great-grandmothers, Mabel Dodge Luhan, was a social magnet and patron of artists and writers in Taos.

The artistic links don’t stop there: In 1922, Little Alice, at 15, married John Evans, Mabel’s 20-year-old son. Natalie, one of their daughters, was Mauldin’s mother; his father was New Mexico native Bill Mauldin, a two-time Pulitzer Prize–winning syndicated political cartoonist known for drawing Willie and Joe , a pair of battle-weary soldiers whose wryly irreverent perspective gave Americans a glimpse of the realities of World War II.

In the early 1920s, Henderson built a rambling single-story adobe home for himself and Alice on land adjacent to his studio. In 1925, along with John Evans and Edwin Brooks, a builder, he formed the Pueblo-Spanish Building Company, whose office was Henderson’s drafting room (now the kitchen). The company helped popularize Pueblo Revival architecture, which formed the foundation for Santa Fe style. Among its signature projects: the Garcia Street compound owned by sisters Amelia Elizabeth and Martha White, now the School for Advanced Research on the Human Experience; what is now the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian; and a renovation of historic Sena Plaza.

Meanwhile, Camino del Monte Sol was filling up with artists—including Frank Applegate and Andrew Dasburg and writer Mary Austin.

Five young avant-garde painters known as Los Cinco Pintores—Fremont Ellis, Willard Nash, Will Shuster, Jozef Bakos, and Walter Mruk—built a row of small adobe houses across the street from Henderson’s studio. When the Depression hit, the Pueblo-Spanish Building Company closed and the Hendersons sold their house and moved to Tesuque, but William held onto the studio.

Half a dozen years later, William Henderson was hired by the federal Works Progress Administration to paint six New Mexico landscape murals for the federal courthouse (next to the downtown post office), where the remarkably modern paintings can still be seen today. Getting the 8-foot-by-12-foot paintings out of the studio required some ingenuity: The artist cut a five-inch-wide slot, ten feet tall, into an outside wall of his studio, and passed the finished murals through the slot.

“He was a master colorist, really a genius,” Mauldin says of Henderson, adding that his great-grandfather was an important influence in Mauldin’s own artistic evolution. Represented for many years by the Laurel Seth Gallery before it closed in 2006, Mauldin creates watercolor

landscapes with a strong focus on color and with delicately delineated forms. “My grandmother told me my paintings really reminded her of [William’s] color concerns,” he relates. “I’m doing something similar to what he did: taking complex visual information and simplifying it so it looks realistic but it’s abstracted.”

Mauldin grew up outside New York City in the town of New City, New York, and in St. Louis. He spent three years at the Art Institute of Chicago before accepting Little Alice’s suggestion to move to Santa Fe, where as a boy he had often visited relatives. Today Mauldin’s home remains largely unrestored since he moved in. The slot door can still be seen in the studio wall. The hand-built furniture and masterfully hand-adzed cabinet doors—“Nobody does that anymore,” he says—reflect the skill of Hispano artisans who worked for his great-grandfather.

The furniture designer’s signature carvedrose motif adorns thick wooden interior window shutters. Roses also are engraved on a combination daybed and sofa, called a Taos bed, which Henderson made for the comfort of his ailing wife. In the former woodworking room, an open-beam ceiling and clerestory windows were inspired by the architecture of New Mexico’s mission churches, Mauldin believes, adding, “It’s kind of cool to think that all this furniture was made in this room.”

Whatever interior design touches have been added to the house, like the cozy nook produced by facing twin benches in front of the fireplace, Mauldin ascribes to the “really good taste” of his former wife, Barbara.

Time has made some changes as well. The house has settled and shifted over the years, leaving walls slightly tilted and some beams warped. The lived-in feeling has its charm, and the absence of updates suits Mauldin, though he did have an engineer check the curving beams recently (he pronounced the house safe). “This is just a great place to be able to do the kind of work I do, both the painting and gardening,” Henderson’s great-grandson reflects. And in that pair of passions, he’s clearly carrying on the esteemed traditions of the artists’ colony that grounds his house’s neighborhood and history. R

From the Summer 2007 issue

Over the last 25 years, Allan Affeldt, Tina Mion, Dan Lutzick, and their team have restored more than a dozen historic properties in the Southwest, and helped bring new prosperity and fame to their communities. Here are four of their famous projects.

LA POSADA HOTEL, WINSLOW, ARIZONA, was built for Fred Harvey and the Santa Fe Railway in 1929. It was the finest hotel on Route 66, and the favorite project of legendary designer Mary Colter. Everybody stayed here—from Howard Hughes and Dorothy Lamour to John Wayne, Albert Einstein, and the Crown Prince of Japan— just like they do today, from Elon Musk to Tom Ford. Closed for 40 years and nearly torn down, La Posada is one of the most renowned and beloved restorations in the country, with nationally famous dining in the Turquoise Room For reservations: 928.289.4366.

THE LEGAL TENDER, LAMY, NEW MEXICO, started as a general store in 1881 when the Railroad arrived in Lamy. In 1884 the store got a stone saloon with a beautiful walnut bar, and it’s been here ever since —now the oldest bar in New Mexico. The famous and infamous have met and entertained here for more than 100 years, from Robert Oppenheimer to George R.R. Martin. Join us at the Legal Tender in Lamy NM, Where the Road Ends and the West Begins — just 15 miles and a world away from Santa Fe. For reservations: 505.466.1650

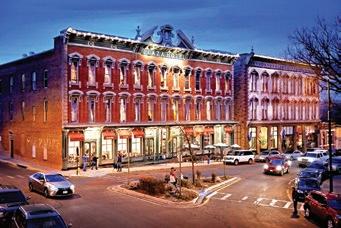

THE PLAZA HOTEL, LAS VEGAS NEW, MEXICO, with its famous Victorian façade, has presided over beautiful Plaza Park in Las Vegas, NM, since 1882. All of our rooms are loving restored, with period antiques and a multi-million-dollar renovation. For 140 years the Plaza has been home away from home for everyone from Doc Holiday to Tommy Lee Jones, and has been featured in films and television series like Longmire, Easy Rider, Red Dawn, and No Country for Old Men. Join us for fabulous farm-to-table dining at Prairie Hill Café.

For reservations: 505.425.3591

THE CASTAÑEDA, LAS VEGAS, NEW MEXICO, was built in 1898 as Fred Harvey’s first trackside hotel in the Southwest, when Las Vegas, NM, was bigger than Albuquerque and richer than Santa Fe. Las Vegas, with almost 1,000 buildings on the National Register of Historic Places, is an architectural treasure trove. In 1899 Teddy Roosevelt held the first reunion of his Rough Riders at the Castañeda, but it closed in 1948 and was mostly abandoned for 70 years. Now the entire hotel has been lavishly restored, with 20 deluxe guest rooms and our wonderful Trackside dining and saloon.

For reservations: 505.425.3591

For award-winning Santa Fe artist Sandra Duran Wilson, art and science are not separate disciplines. As a child peering into her father’s microscope, she wondered about quantum physics, while her mother’s family of artists taught her to harness her imagination and push boundaries. Today, her multimedia painting, sculptures, and photographic prints illustrate her exploration of the possible.

“I always envisioned creativity as a torch that lights the way for others to see and experience art,” she says. “Risk taking, which manifests itself in my experiments combining different mediums, drives my work with depth, texture, layers—making materials into something they were never intended to be.”

Her work, influenced by scientific concepts in physics, chemistry, and biology, is also informed by her study of cognitive science. It is further influenced by a neurological condition called synesthesia, in which the senses cross their wires and produce such sensations as colors that talk, or music that appears as waves of color.

“The music I listen to—the sounds and tempo—influences how and what I paint,” she says.

Wilson’s three-dimensional sculptures fuse acrylic paint on layers of cast acrylic. The light penetrates and the images morph depending on the viewing angle. Her latest venture, digital mixed-media prints, combine her own photographs, paintings, and natural objects like branches and leaves. These on-demand digital works are available in a variety of paper, mat, and framing options.

An accomplished author of six art technique books, Wilson also teaches classes and workshops around the world, calling her travels “adventures to discover creativity, where one is open to surprises.” Her work can be found at her studio in Santa Fe and in corporate, civic, and educational institutions and private collections globally.

Connections, 6" x 24", cast acrylic and resin, 2024

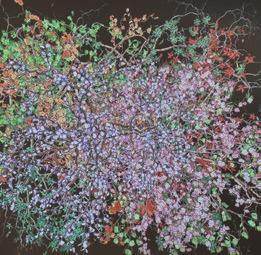

Storm’s most important tools are Wonder and Possibility

As a child, award-winning painter Linda Storm played in the mud, foraged, and danced. She read myths about ancient goddesses who birthed seasons, healed diseases, and tossed magical golden apples. She laughed as she ran through spider webs sparkling with dew. She drew whenever she had supplies. Art was her favorite subject.